Abstract

Documenting a patient’s family history of cancer is useful in assessing their predisposition to some types of hereditary cancers. A group of nurses working with cancer patients were surveyed, by way of a questionnaire, to determine their level of knowledge about oncogenetics, describe various issues related to their capacity to identify, refer and support individuals with a hereditary risk of cancer, and explore their interest in continuing education on this topic. The findings show limited knowledge and a low sense of competence among the participating nurses, as well as a lack of access to university and continuing education programs in this field. Training focused on competency development would enhance their capacity to carry out an initial assessment of individuals who are potentially at risk for cancer and refer them to specialized resources.

Keywords: hereditary cancers, oncogenetics, family history, nursing competencies

There were an estimated 225,800 new cancer cases and 83,300 cancer deaths in Canada in 2020 (Brenner et al., 2020). Despite significant progress in reducing the mortality rate for several types of tumours (breast, prostate and lung) (Brenner et al., 2020), cancer continues to be the country’s leading cause of death (Comité consultatif des statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer/Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee, 2019). Some forms of cancer can be qualified as “hereditary,” i.e., caused by a genetic mutation inherited in an autosomal dominant form. A parent who is a carrier of a predisposition gene mutation has a 50% chance of passing on the mutated gene to their children (Garber & Offit, 2005; Lindor et al., 2008; Mucci et al., 2016). Some 5% to 10% of various types of cancer are associated with hereditary syndromes (Viassolo & Chappuis, 2016). These include colorectal, breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers (Foulkes, 2008; Garber & Offit, 2005). In addition to hereditary cancers, roughly 15% to 20% of cancer cases are categorized as “familial” (Berliner & Fay, 2007; Eberl et al., 2005). They may be the result of genetic mutations that have yet to be identified, interactions between genetic and environmental factors, or exposure to a similar environment or shared lifestyle practices (Berliner & Fay, 2007). Familial cancers do not generally exhibit the classic characteristics of hereditary syndromes (Berliner & Fay, 2007), but they may be associated with an increased risk of cancer, which is at its greatest when a member of the family has a certain kind of cancer, such as breast or colorectal cancer (Mavaddat et al., 2013; Mucci et al., 2016).

Obtaining a family history can help in assessing the risk of developing cancer and, thereby, reducing the overall cancer burden at the initial assessment stage by identifying high-risk individuals and developing personalized prevention strategies (Brennan & Wild, 2015; Chen et al., 2021; Stadler et al., 2014). The data collected on a patient’s personal medical history and family history of cancer can be used to determine the likelihood of their having a familial mutation predisposing them to certain types of cancers (Riley et al., 2012). Taking and analyzing a patient’s family history is an integral part of good clinical practices and should be systematically incorporated into every cancer care scenario (Chen et al., 2021; Eberl et al., 2005), especially when it comes to identifying individuals likely to be at high risk for colorectal, breast, ovarian or prostate cancer (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE], 2013). Despite the important role of family history-taking in cancer prevention, it remains an underutilized technique in the cancer care trajectory, which limits its impact on prevention outcomes (Chen et al., 2021; Houwink et al., 2014; Valdez et al. 2010). Many studies report that family information is not always documented in patient files in cases where it would be called for. Furthermore, even when a family history is taken, it is often incomplete and, therefore, ineffective in assessing cancer risks (Powell et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2013). Individuals at risk of familial cancer are not always referred to oncogenetics, thus hindering an accurate assessment of their risk and preventing them from receiving personalized care and follow-up (Stuckey et al., 2016; Wood et al., 2013).

Many factors contribute to the underutilization of family history-taking by healthcare teams, including the lack of time to collect this information (Houwink et al., 2014), the lack of applicable guidelines (Wood et al., 2013), a limited grasp of the role played by heredity in the development of cancer (Chen et al., 2018), and negative attitudes in the public healthcare system toward genetics and genomics (Khoury et al., 2007). Studies also point to a lack of understanding with regard to the potential of family history information in screening (Chow-White et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2013) and insufficient overall training of healthcare professionals, including nurses (Carroll et al., 2009; Farndon & Bennett, 2008; Sussner et al., 2011; Talwar et al., 2017). Furthermore, although the Human Genome Project opened many doors in terms of preventing, diagnosing and managing of cancer and many other diseases, it also led to a considerable increase in the demand for oncogenetic services (Petersen et al., 2014). Due to a shortage of specialists in the field, non-specialists are often responsible for taking and evaluating family histories, interpreting the results of genetic testing, providing genetics/genomics education to patients and referring them to the appropriate oncogenetic resources (Houwink et al., 2014; Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics Health and Society [SACGHS], 2011). Nurses, as the most numerous group of professionals in the healthcare system, play a crucial role in cancer prevention (Chen et al., 2021; Wood et al., 2013). They have been specifically trained to listen and provide support to patients and have the distinctive knowledge, knowhow and professional experience to deliver differentiated care, advice, support and information to individuals at high risk of cancer and their families (Murphy & Chappuis, 2006).

This paper presents the results of a pilot project for a research program designed to enhance the competencies of front-line healthcare professionals, so they can identify and attend to patients with a hereditary risk of cancer. The results will be incorporated into a broader research project currently underway (C-MOnGene), the goal of which is to improve the range of oncogenetic services available in Quebec (Lapointe et al., 2021). More specifically, this paper aims to document the knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses working at a CISSS1 in Quebec in several different healthcare settings. There are three main objectives: 1) assess nurses’ knowledge with regard to oncology and oncogenetics; 2) describe various issues related to their capacity to identify, refer and support individuals with a hereditary risk of cancer; and 3) explore their interest in continuing education on this topic.

METHODOLOGY

Research design and procedures

An exploratory descriptive research design (Gray, 2017) was selected for this study. A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted among nurses working with cancer patients. A purposive sample was drawn with the support of targeted CISSS managers working in nursing care (NC), oncology/palliative and end-of-life care (PELC) and support for the autonomy of seniors (SAS), who helped identify key individuals within their respective teams. The individuals thus identified were asked to draw up lists of potentially eligible participants for the study for each of the healthcare settings involved. Inclusion criteria were as follows: a) be a nurse working with cancer patients; b) work in a hospital centre (CH), family medicine group (GMF), long-term care facility (CHSLD), local community service centre (CLSC) or palliative care facility (MSP); c) work in one of the five sectors of the CISSS. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the CISSS (2018-490).

Data collection

An initial email was sent to the nurses on these lists by the managers of the concerned programs, inviting them to take part in the study. It contained a SurveyMonkey link to a short questionnaire with 33 questions, most of which were closed-ended (Appendix I). Respondents were first asked to fill out a short sociodemographic profile. The themes addressed in the body of the questionnaire were 1) knowledge of heredity and cancer; 2) past experience in identifying people at high risk of hereditary cancer; 3) sense of competence in meeting the needs of cancer patients or their families with concerns about their family history or risk of hereditary cancer; 4) role of the nurse with regard to oncogenetics in their clinical practice; 5) perception of professional responsibility in identifying and managing cases where there is a hereditary risk of cancer; and 6) interest in continuing education regarding the issues related to family histories of cancer and suggestions for the development of information tools and materials about oncogenetics. Given the dearth of literature concerning the knowledge, competencies and professional practices of nurses in oncogenetics, the questions were specifically developed by the research team on the basis of previous research studies focusing on healthcare professionals (Cléophat et al., 2020; Gonthier et al., 2018). In an effort to ensure a maximum number of respondents, three email reminders were sent by managers over a six-week period. A total of 151 invitations were emailed to the five sectors of the CISSS in question. This corresponds to the population of nurses likely to be in contact with cancer patients. Data collection took place in April and May 2018.

Analysis of the data

Descriptive analyses (means and proportions) were carried out for the sociodemographic characteristics and respondents’ answers to the various questions in the survey and documented in an Excel spreadsheet. These analyses revolved around the themes addressed in the questionnaire, namely the participating nurses’ knowledge and sense of competence with regard to oncogenetics, issues related to identifying individuals with a hereditary risk of cancer, and the development and improvement of respondents’ competencies in oncogenetics. Given the limited size of the sample, no subgroup comparisons were performed.

RESULTS

Participants

The sample consisted of 40 participants (rate of participation = 26%): 36 female nurses and four male nurses ranging in age between 24 and 60 years, with a median age of 38. Most of the respondents worked in a CH or an GMF. More than half had less than five years of experience in their current job. The average time per week spent working with cancer patients was 16 hours. Table 1 presents a detailed description of the participants.

Table 1.

Socioprofessional Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristics | Number (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Women | 36 | 90 |

| Men | 4 | 10 | |

| Age | 20–30 years | 5 | 13 |

| 31–40 years | 16 | 41 | |

| 41–50 years | 13 | 33 | |

| 51+ years | 5 | 13 | |

| Years of experience for current position | 1–5 years | 21 | 53 |

| 6–10 years | 7 | 17 | |

| 11+ years | 12 | 30 | |

| Hours/week worked with cancer patients | 0–10 hours | 20 | 50 |

| 11–20 hours | 2 | 5 | |

| 21–30 hours | 4 | 10 | |

| 31+ hours | 12 | 30 | |

| Don’t know/varies | 2 | 5 | |

| Healthcare facility | Hospital centre (CH) | 15 | 36 |

| Local community service centre (CLSC) | 7 | 17 | |

| Family medicine group (GMF) | 15 | 36 | |

| Long-term care facility (CHSLD) | 1 | 2 | |

| Palliative care facility (MSP) | 4 | 9 | |

Four observations, which fall under three main themes, emerged from the analysis of the data: 1) nurses lack knowledge of and sense of competence in oncogenetics; 2) discussions concerning a family history of cancer are generally held at the patient’s prompting; 3) nurses feel they have an important role to play in oncogenetics; and 4) not enough training in oncogenetics is being done.

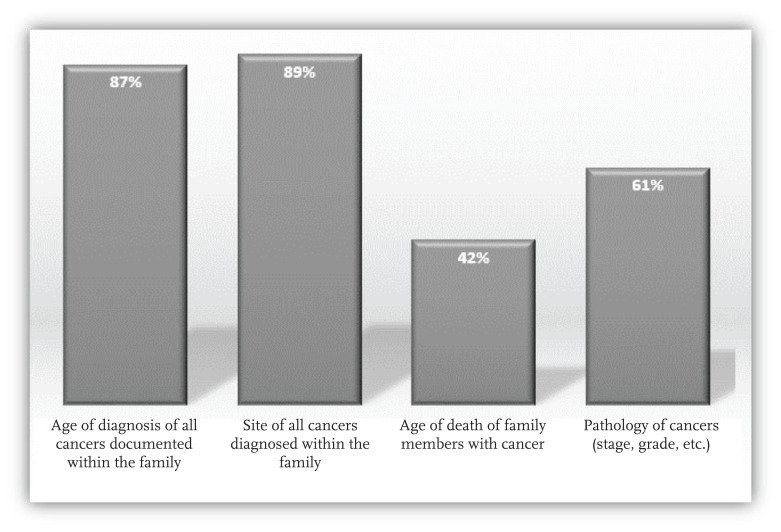

Observation 1: Nurses lack knowledge of and sense of competence in oncogenetics

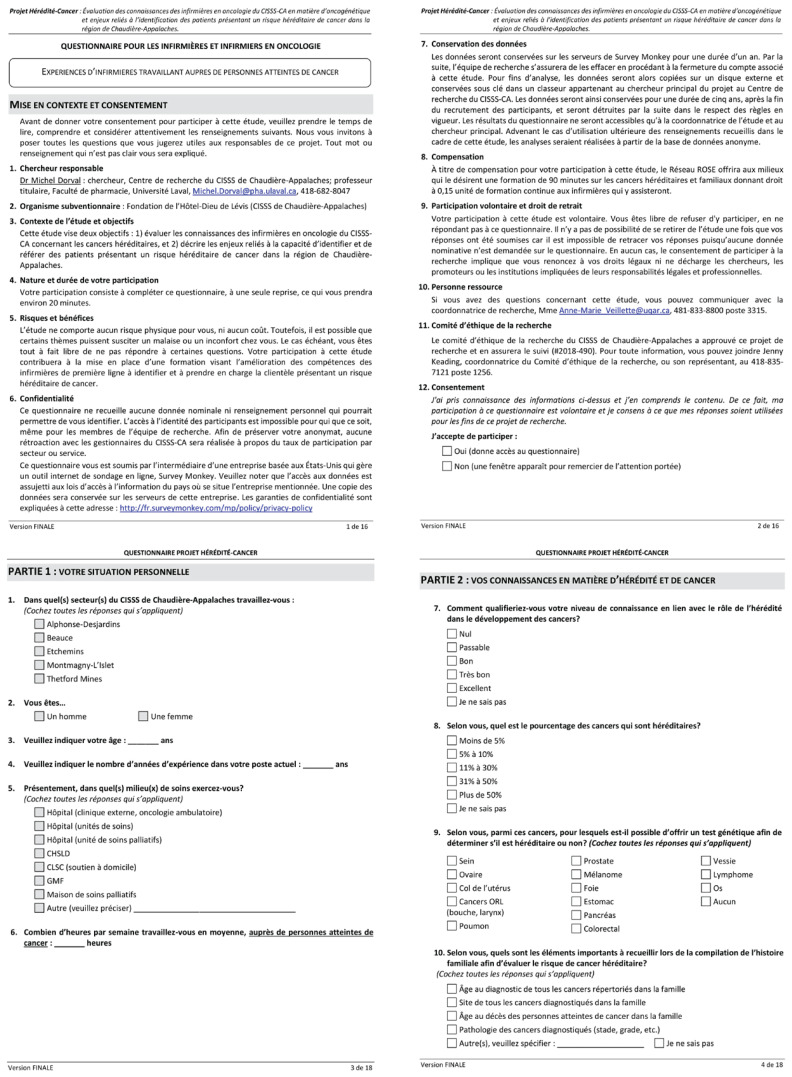

A total of 71% of the nurses who answered the survey said their understanding of the role of heredity in the development of cancer was fair to non-existent. None qualified their level of knowledge as very good or excellent. More than half (56%) overestimated the influence of heredity on cancer susceptibility, responding that more than 10% of all cancers are hereditary. Similarly, 45% erroneously believed that genetic testing could be used to identify a hereditary risk for developing cervical cancer. A greater number of respondents were aware of the existence of genetic testing for predisposition for breast cancer (89%) than those who knew testing was available for ovarian cancer (58%) and colorectal cancer (45%). A lower percentage were familiar with genetic testing for prostate cancer (24%) and pancreatic cancer (3%). A majority of the participating nurses were able to identify the important pieces of data to collect when taking a family history, with the exception of the age of death of family members with cancer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Information to Collect When Taking a Family History

Most of the nurses in the study (82%) deemed it essential to evaluate the family health history on the paternal side when cancer is diagnosed on the maternal side (or vice versa). Similarly, a majority (61%) felt it was relevant to go back three generations when investigating a family history. About half (53%) considered, and rightly so, that patients with a hereditary form of cancer tend to be at a higher risk of developing another type of cancer and that hereditary cancers often occur at a younger age (55%). Moreover, although they believed that a carrier of a genetic mutation will not necessarily develop cancer in their lifetime (74%), many were of the opinion that the mutation can skip a generation (61%).

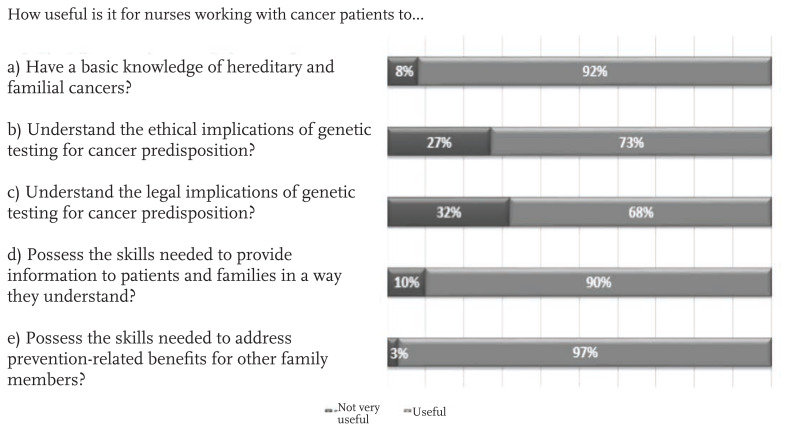

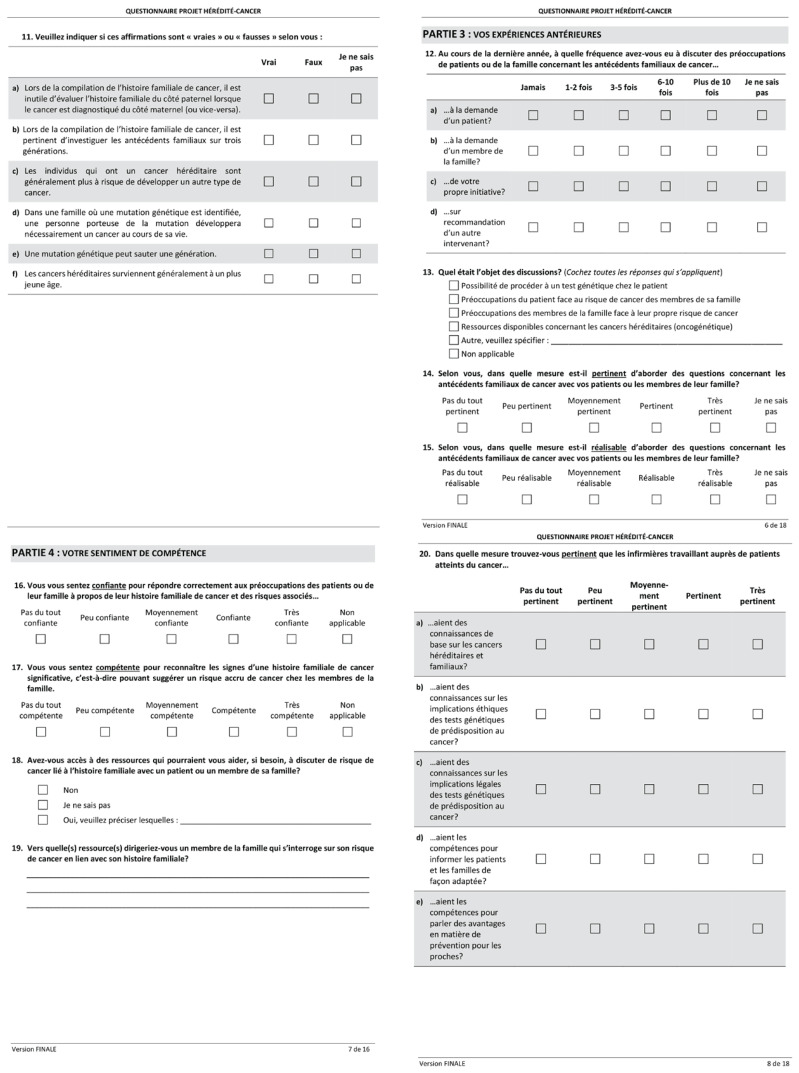

The respondents (84%) did not feel qualified to sufficiently address the concerns of cancer patients and their families with respect to their family history of cancer and the associated risks. Many (79%) specifically mentioned not having the skill sets necessary to recognize significant aspects of a family’s cancer history, i.e., those that would suggest an increased risk of cancer within the patient’s family members. In addition, 40% said they did not have access to resources they could turn to for help, if needed, to discuss the risks of cancer related to the family history with patients or family members. Many tend to refer patients and families to other healthcare professionals who are better equipped to answer these questions (oncology nurse navigator, oncologist/hematologist, geneticist, family physician, pharmacist, etc.). However, the nurses felt it was essential when working with cancer patients to have the necessary knowledge and competencies to discuss the matter with patients and their families (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Knowledge and Competencies of Nurses in Oncology Settings

Observation 2: Discussions concerning a family history of cancer are generally held at the patient’s prompting

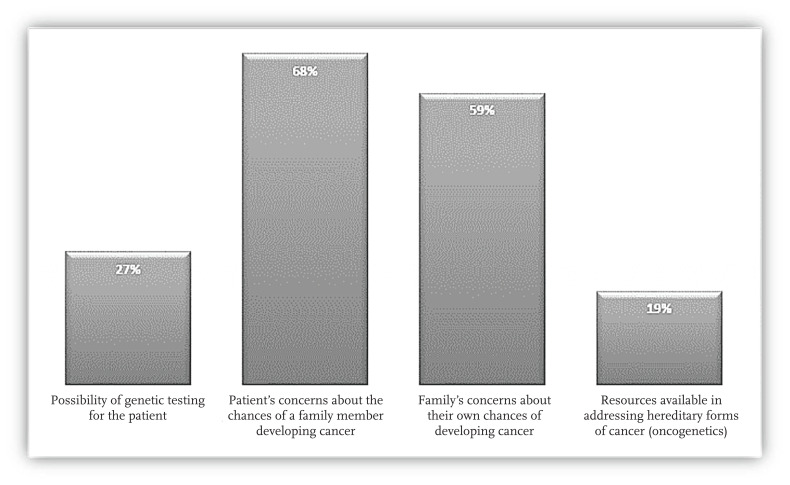

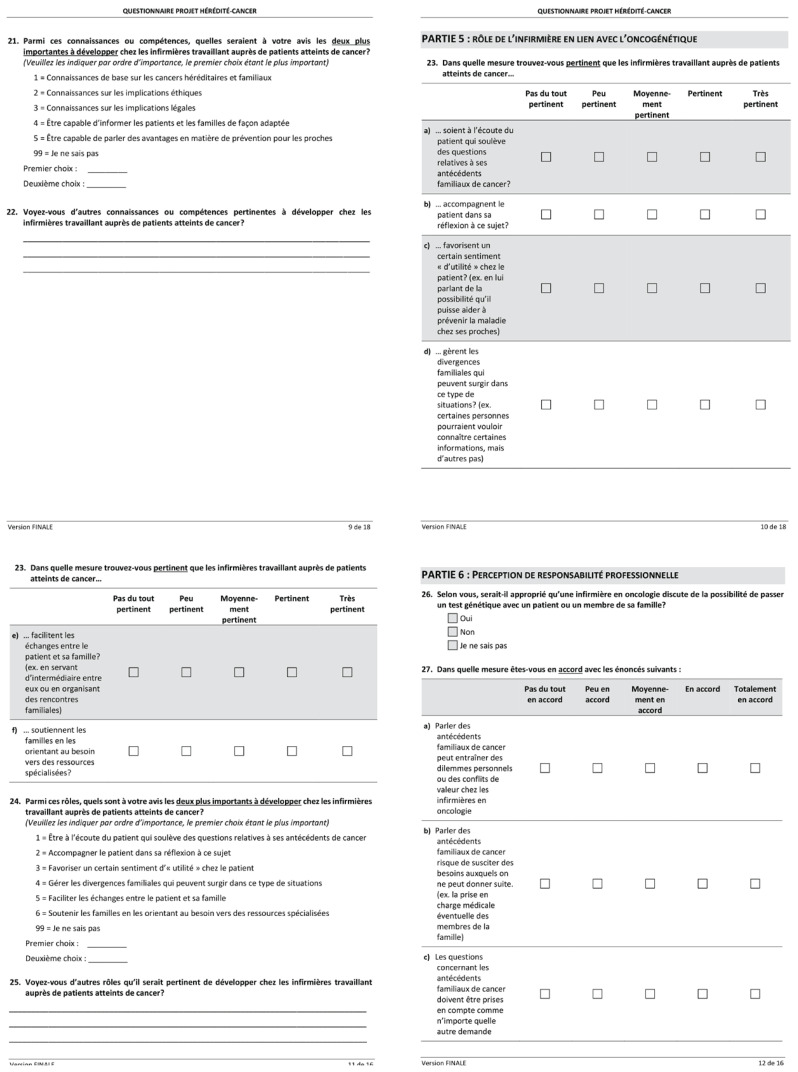

Fewer than half of the survey respondents (42%) said they were the ones to initiate discussions about family history with cancer patients or their families. They generally do so after being asked about it by the patient (68%) or a family member (47%). Less frequently, it is in response to a referral from another professional (18%). The topics that tend to be asked about are listed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Topics of Discussion Related to Family History

Although the nurses were not generally the ones to initiate discussions about a history of cancer in the family, 58% felt it was essential for the topic to be brought up with cancer patients and their families. Some 63% of the respondents felt that addressing these questions with patients or their families could easily be incorporated into their routine follow-up.

Observation 3: Nurses feel they have an important role to play in oncogenetics

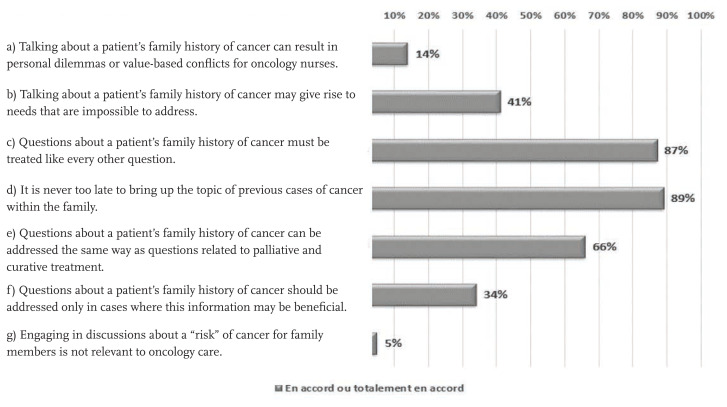

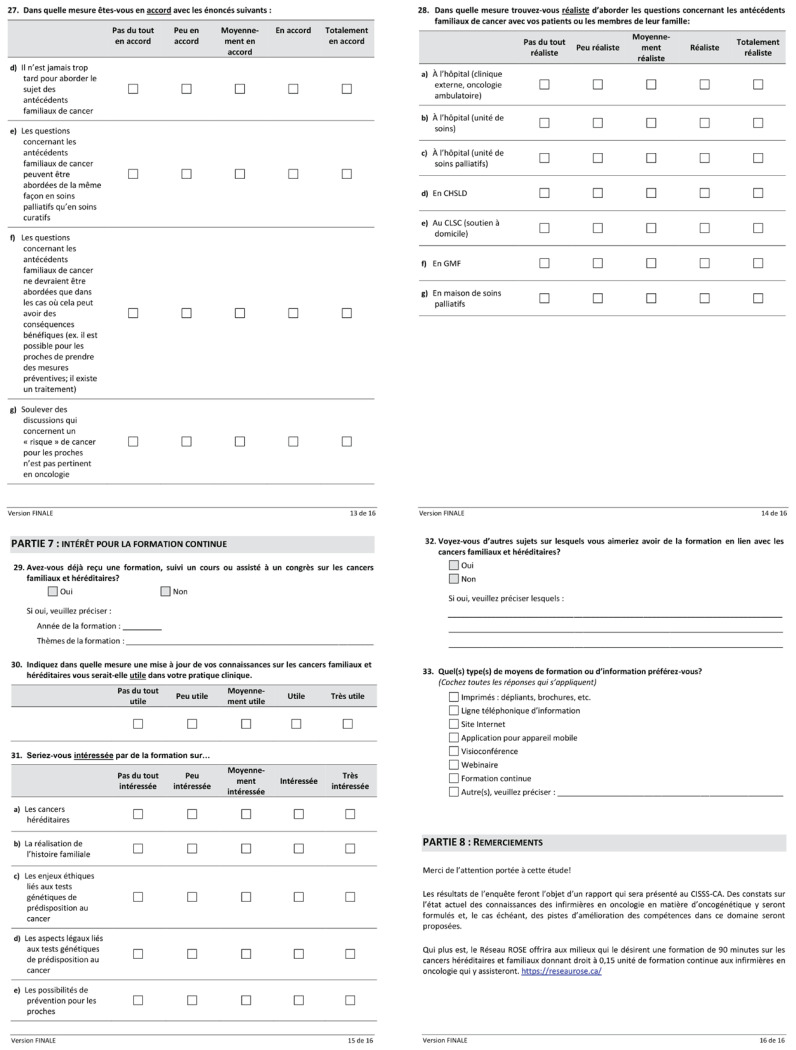

The majority of the nurses surveyed considered that their role in oncogenetics is essential in that they 1) are someone cancer patients can talk to (97%); 2) support patients in their thought process about their cancer and family history (86%); 3) help families by referring them to the appropriate resources (92%); 4) empower patients, specifically by discussing the possibility that their situation might help prevent other family members from developing the disease (81%); 5) help manage family disagreements that may arise, especially those concerning the desire to know or not know more about their family health history (65%); and 6) facilitate discussions between cancer patients and members of their family by serving as a go-between or by organizing family meetings (55%). Moreover, although the respondents indicated that they seldom bring up the possibility of genetic testing, many of them (77%) felt they should assume this role. Regarding their professional duties, although they said the questions concerning previous cases of cancer in the family can be brought up at any point in the care trajectory (89%), some (34%) raised the idea that these matters should not be discussed unless they might actually benefit cancer patients or their families (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Professional Duties of Nurses Related to Oncogenetics

Observation 4: Not enough training in oncogenetics is being done

There are precious few continuing education programs, courses in university curricula and conferences on hereditary and familial cancers available to nurses who work with cancer patients. In all, 95% of the nurses surveyed indicated they had not been informed of the existence of activities of this nature or been given the opportunity to attend. Yet, 77% of them felt it was paramount to have access to this type of content in their academic studies and to be able to stay current on the latest information on familial and hereditary cancers. When asked about their areas of interest for ongoing training, more than 90% identified hereditary forms of cancer and family prevention. This was followed by techniques for conducting family histories and the ethical and legal issues of genetic testing for cancer predisposition, at 76% and 66% respectively. Some 61% of the nurses surveyed indicated that they would be interested in learning more about hereditary and familial cancers, although the results point to a preference for flexible formats that can be easily integrated into their schedule, namely videoconferences (55%), webinars (47%), and websites (45%). More traditional paper-based methods (brochures, booklets, etc.) were a less popular choice (34%).

DISCUSSION

The goals of this study were to assess how familiar the nurses working with cancer patients at a CISSS in Quebec were with oncogenetics, to describe the issues related to their capacity to identify, refer and support individuals with a hereditary risk of cancer and to explore their interest in continuing education in this regard.

The results show that the nurses working in oncology settings did not feel they had the knowledge required to fully grasp the role of heredity in the development of certain types of cancer. This lack of knowledge stands to undermine their confidence and influence their sense of competence in assessing cancer risks based on family history and addressing the concerns of patients and their families. Some authors have suggested that the rapid expansion of knowledge about oncogenetics in recent years (Chen et al., 2018; Talwar et al., 2017), and the lack of training specifically related to this field of practice in nursing programs (Carroll et al., 2009; Farndon & Bennett, 2008; Sussner et al., 2011; Talwar et al., 2017) contribute to this knowledge deficit among nurses in oncology settings. As a result, they may feel ill-equipped to answer questions put to them by individuals who are concerned about a possible hereditary predisposition to cancer and, therefore, reluctant to initiate discussions in this regard. The results of this study indicate that questions involving family history and the associated cancer risks tend to come from cancer patients themselves. Although the nurses surveyed felt that addressing these questions is essential, our data suggest that their involvement in these discussions and in supporting patients and their families in this regard is underutilized. Yet, identifying people who could benefit from oncogenetic services constitutes a nursing competency (Gaff, 2005). A number of authors also posit that nurses are in the best position to identify high-risk families among those who are affected by a hereditary predisposition, but who are categorized as low or moderate risk (Allen, et al., 2016; Calzone et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2018, 2021). Nurses can also raise awareness among cancer patients and their families about the importance of documenting family histories of cancer, identifying the appropriate genetic services and encouraging high-risk individuals to consult these resources. Cooley (2014) considers it essential for nurses to be involved in developing oncogenetic knowledge in order to improve their competencies in this field and strengthen their capacity to identify, assess and refer high-risk patients and families.

Although discussions on genetic testing make it easier to identify and assess individuals at high risk for cancer (Brennan & Wild, 2015; Chen et al., 2021; Stadler et al., 2014), the results of this study show that the participating nurses seldom addressed this issue with cancer patients and their families. They, nevertheless, tended to believe it was their role to initiate discussions about family history and refer patients to the appropriate resources when required. In reality, it would seem the nurses were more likely to immediately refer patients and their families to other healthcare professionals who they deemed better qualified to tackle the issue of a family history of cancer. It is important to point out that documenting a patient’s family history is the first step in assessing cancer risk and determining whether testing for genetic predisposition is warranted. Other authors have argued that the lack of knowledge about hereditary cancers, the downplaying of the potential of family histories and the uncertainty concerning the usefulness and clinical validity of genetic information can deter some healthcare professionals, nurses chief among them, from incorporating these elements into their practice (Chow-White et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2013). In a study by Cléophat et al. (2020), nurses showed a strong interest in adding a genetic counsellor to their team and having access to clear guidelines to make the family history-taking process easier and facilitate discussions concerning the hereditary component of cancer. That being said, these discussions can often be a source of anxiety and family conflict, making it necessary for nurses to make time and support available to patients and their families (Lapointe et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2013). In this sense, although some studies have shown that sharing genetic information can have positive effects, especially from a prevention standpoint (Lafrenière et al., 2013), others reveal that it can lead to increased family tensions, particularly in cases where a tested individual refuses to disclose their genetic results to other family members or when there is a lack of consensus among family members about whether or not this genetic information should be disclosed or followed up on with hereditary cancer predisposition testing (Lafrenière et al., 2013; Lapointe et al., 2013).

Even though a majority of the respondents felt that the questions concerning family histories of cancer can be brought up at any point during the cancer care trajectory, some said they were worried that doing so might create needs among cancer patients and their families that they, as nurses, would not be able to meet, especially needs of a psychological nature. In this regard, several authors note the limited capacity of some professionals to adequately convey the implications of hereditary risks (Cléophat et al., 2020; Hallowell et al., 2005; Sperber et al., 2017; Talwar et al., 2017), their worry about the potential psychological impacts on patients (guilt, concern, fear, sadness, anger) (Allen et al., 2016; Cléophat et al., 2020; Tercyak et al., 2010), and their lack of time to meet patients’ needs in terms of support (Eberl et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2014) as factors that may deter them from evaluating a family history. The nurses who participated in this study felt that these questions should not be addressed unless there was a possibility of a tangible benefit for cancer patients and their families. This is consistent with NICE recommendations (2013) on appropriate treatment and care, which stipulate that discussions about family history should take place only when the benefits outweigh the risks. These discussions are more welcome when preventive and therapeutic options are readily available (Green et al., 2013; Valdez, et al., 2010). The nurses in this study also mentioned that being knowledgeable about existing specialized resources in oncogenetics and having access to these resources were essential to incorporating discussions about family histories of cancer into their clinical practices. This corroborates the findings of the study conducted by Cléophat et al. (2020), which assert that this knowledge is an important lever in initiating discussions about previous cases of cancer within the family. However, the cancer risk assessment should be optimized by an interdisciplinary team, comprised of oncology professionals and genetics experts, including genetic counsellors, medical geneticists, surgeons, oncologists, social workers, oncology nurses and psychologists (Berliner & Fay, 2007; Murphy & Chappuis, 2006; NICE, 2013).

Although oncology nurses consider genetics to be an important part of their practice (Calzone et al., 2010), the results of this study contend that their access to academic and continuing education in this topic is limited. Because genetics is a rapidly changing field, it is essential that healthcare professionals working with cancer patients be able to refresh their knowledge and skills on an ongoing basis (Talwar et al., 2017). Accordingly, several studies show that having access to continuing education with a focus on skills development helps improve assessments and referrals for patients at a high risk of developing cancer (Chen et al., 2018, 2021; Gaff, 2005; Talwar et al., 2017). For example, the study conducted by Chen et al. (2018) on healthcare professionals who were not specialized in genetics, revealed that, within three months of taking a course on family cancer histories, participants were more inclined to evaluate family histories and make recommendations for genetic predisposition testing. Similarly, a study by Gaff (2005) reported that oncology nurses who had attended a workshop on cancer genetics indicated that it was very useful and applicable to their work, specifically because it made them feel more confident in identifying individuals potentially at risk for a hereditary form of cancer. However, to be able to address family concerns and manage issues related to a family history of cancer, nurses should have access to training in cancer genetics as well as the ethical, legal and psychosocial impacts of hereditary cancers (Cléophat et al., 2020). The results of this study suggest that nurses are interested in continuing education on hereditary and familial cancers, especially those with a flexible delivery format that can be easily worked into their schedule. These findings are consistent with those of Chen et al. (2018), which demonstrated that condensed, intensive training programs with a learning approach adapted to participants’ professional realities make them easier to access and enjoy higher attendance.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides preliminary data on the knowledge, attitudes and practices in oncogenetics of nurses working with cancer patients in a CISSS in Quebec. Despite the innovative focus of the research (in that, to date, there have been very few studies documenting the issues related to nurses’ capacity to discuss family histories and to identify, refer and support patients with a hereditary risk of cancer), there are certain limitations that should be considered. First and foremost, the study was undertaken with the goal of exploring a topic for which there are no pre-existing validated measures. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire used in this study are uncertain. Adjustments made based on the comments and recommendations compiled during the pre-test nevertheless provided an acceptable level of face validity. Statistical analyses aimed at comparing certain subgroups had initially been planned, but in the end, these were not feasible given the small sample size. It was, therefore, impossible to compare nurses’ knowledge, experiences, perceptions and interests based on their sociodemographic and professional characteristics. Finally, although the data collected allow for a better representation of the competencies and knowledge of oncology nurses, the generalizability and transferability of the results remain limited, even though consistency with the scientific literature suggests a certain plausibility.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that many nurses working with cancer patients have to deal with patients’ and family members’ concerns about previous cases of cancer in their family. Although a number of the respondents considered these conversations to be essential, they were generally reluctant to initiate them, which can be explained by a lack of knowledge, competency, confidence and support with regard to broaching the topic of family history with patients and their loved ones. Yet, nurses, being at the front line of health promotion and disease prevention and having specialized care and support skills, play a predominant role in the initial assessments of individuals at risk of cancer. Not only is family history-taking necessary in conducting these assessments, but the information provided to cancer patients can also be extremely helpful to other family members and have a direct impact on them. However, these discussions must be supported by solid oncogenetic knowledge and competencies, which are currently lacking among nursing staff. Continued education about hereditary cancers (including the related psychological aspects) and the development of specific tools, guidelines and information materials related to oncogenetics would strengthen nurses’ capacity to assess individuals and families who are at risk. This would also allow nurses to address concerns about family histories more efficiently and refer patients and families to specialized resources. Incorporating these considerations into the C-MOnGene project could help optimize the delivery of oncogenetic services in Quebec, especially in non-specialized healthcare facilities and in remote communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the professionals at the CISSS who contributed to this research—Josée Chouinard, Brigitte Laflamme and Josée Rivard—and the members of the C-MOnGene project team for their support in writing this paper, namely Dr. Jocelyne Chiquette, Julie Lapointe and Arian Omeranovic.

Appendix 1

Footnotes

CISSSs (centres intégré de santé et de services sociaux or integrated health and social services centres) are facilities created as a result of the amalgamation of all public institutions in a given health and social services region, or part of a region, with the health and social services agency, as the case may be (sections 3 et 4 Act to modify the organization and governance of the health and social services network, in particular by abolishing the regional agencies) (Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux [MSSS], 2017).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the research, writing and/or publication of this paper and declare that they are the sole owners of all rights to this original work, entitled “Issues associated with a hereditary risk of cancer: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses in oncology settings.” The authors agree to assign all rights to CANO/ACIO for publication in the Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The authors received the following financial support for the research and/or writing and publication of this paper: Fondation Hôtel Dieu de Lévis, Oncopole and Hermann Nabi, FRQS Junior 2 Research Scholar.

REFERENCES

- Allen CG, McBride CM, Balcazar HG, Kaphingst KA. Community health workers: An untapped resource to promote genomic literacy. Journal of Health Communication. 2016;21(Suppl 2):25–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1196272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner JL, Fay AM Practice Issues Subcommittee of the National Society of Genetic Counselors’ Familial Cancer Risk Counseling Special Interest Group. Risk assessment and genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16(3):241–260. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P, Wild CP. Genomics of cancer and a new era for cancer prevention. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11(11):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner DR, Weir HK, Demers AA, Ellison LF, Louzado C, Shaw A, Turner D, Woods RR, Smith LM for the Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2020. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(9):E199–E205. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzone KA, Cashion A, Feetham S, Jenkins J, Prows CA, Williams JK, Wung S-F. Nurses transforming health care using genetics and genomics. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JC, Rideout AL, Wilson BJ, Allanson JM, Blaine SM, Esplen MJ, Farrell SA, Taylor S. Genetic education for primary care providers: Improving attitudes, knowledge, and confidence. Canadian family physician. 2009;55(12):e92–e99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Zhao S, Stelzig D, Dhar US, Eble NT, Yeh Y-C, Kwok O-M. Development and evaluation of a genomics training program for community health workers in Texas. Genetics in Medicine. 2018;20(9):1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-J, Zhao S, Nimmons MK, Dhar US, Eble NT, Martinez D, Yeah Y-L, Chen L-S. Family health history-based cancer prevention training for community health workers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2021;60(3):e159–e167. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow-White P, Ha D, Laskin J. Knowledge, attitudes, and values among physicians working with clinical genomics: A survey of medical oncologists. Human resources for health, 2017;15(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cléophat JE, Pelletier S, Déry A, Joly Y, Gagnon P, Marin A, Chiquette J, Dorval M. Survey of palliative care provider’s needs, perceived roles, and ethical concerns about addressing cancer family history at the end of life. Palliative and Supportive Care, 2020;19(2):217–222. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comité consultatif des statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer. Statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer. Société canadienne du cancer.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley C. Making use of genes. Nursing Standard, 2014;28(24):24–25. doi: 10.7748/ns2014.02.28.24.24.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl MM, Sunga AY, Farrell CD, Mahoney MC. Patients with a family history of cancer: Identification and management. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(3):211–217. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farndon PA, Bennett C. Genetics education for health professionals: Strategies and outcomes from a national initiative in the United Kingdom. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 2008;17(2):161–169. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(20):2143–2153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaff CL. Identifying clients who might benefit from genetic services and information. Nursing Standard, 2005;20(1):49–53. doi: 10.7748/ns2005.09.20.1.49.c3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber JE, Offit K. Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. Journal of clinical oncology, 2005;23(2):276–292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonthier C, Pelletier S, Gagnon P, Marin A, Chiquette J, Gagnon B, Roy L, Dorval M. Issues related to family history of cancer at the end of life: A palliative care providers’ survey. Family Cancer, 2018;17(2):303–307. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-0021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. Mixed methods research. In: Gray J, Grove S, Sutherland S, editors. The Practice of Nursing Research. Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence. 8th Edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 310–328. [Google Scholar]

- Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, McGuire AL, Biesecker LG. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genetics in Medicine, 2013;15(7):565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell N, Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R, Foster C, Lucassen A, Moynihan C, Watson M. Communication about genetic testing in families of male BRCA1/2 carriers and noncarriers: Patterns, priorities and problems. Clinical Genetics. 2005;67(6):492–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houwink EJ, Muijtjens AM, van Teeffelen SR, Henneman L, Joost Rethans J, van der Jagt LE, Van Luijk AJ, Cornel MC. Effectiveness of oncogenetics training on general practitioners’ consultation skills: A randomized controlled trial. Genetics in Medicine, 2014;16(1):45–52. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Burke W, Bowen S, Zimmern R. Will genomics widen or help heal the schism between medicine and public health? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(4):310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrenière D, Bouchard K, Godard B, Simard J, Dorval M. Family communication following BRCA1/2 genetic testing: A close look at the process. Journal of Genetics Counseling. 2013;22(3):323–335. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9559-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Côté C, Bouchard K, Godard B, Simard J, Dorval M. Life event may contribute to family communication about cancer risk following BRCA1/2 testing. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 2013;22(2):155–290. doi: 10.1007/s10897-012-9531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Dorval M, Chiquette J, Joly Y, Guertin JR, Laberge M, Gekas J, Nabi H. A collaborative model for a flexible, accessible, and efficient oncogenetic services for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Preliminary results and protocol of the C-MOnGene study. Cancers, 2021;13(11):2729. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, Greene MH. Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes (2nd ed.) Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;38:3–93. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KH, Wood ME, Daniels M, Burke C, Ford J, Kauff ND, Kohlmann W, Hughes KS. American Society of Clinical Oncology Expert Statement: Collection and use of a cancer family history for oncology providers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2014;32(8):833–840. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, Easton DF. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: Results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(11):812–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux. Glossaire Définition de termes relatifs au réseau de la santé et des services sociaux. Gouvernement du Québec.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, Czene K, Havelick DJ, Scheike T, Graff RE, Kaprio J. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in nordic countries. JAMA. 2016;315(1):68–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AEet Chappuis PO. Organisation de la consultation et rôle de l’infirmière en oncogénétique: le modèle suisse. Revue francophone Psycho-Oncologie, 2006;5(1):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Familial breast cancer. Classification and care of people at risk of familial breast cancer and management of breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer. United Kingdom; 2013. 2013. Contract No.: NICE clinical guideline 164. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KE, Prows CA, Martin LJ, Maglo KN. Personalized medicine, availability, and group disparity: An inquiry into how physicians perceive and rate the elements and barriers of personalized medicine. Public Health Genomics. 2014;17(4):209–220. doi: 10.1159/000362359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KP, Christianson CA, Hahn SE, Dave G, Evans LR, Blanton SH, Hauser E, Henrich VC. Collection of family health history for assessment of chronic disease risk in primary care. North Carolina Medical Journal, 2013;74(4):279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, Senter LA, Peters JA, Costalas JW, Callif-Daley F, Trepanier AM. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: Updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of Genetics Counseling. 2012;21(2):151–161. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics Health and Society, US Department of Health & Human Services. Genetics education and training. 2011 www.genome.gov/Pages/Careers/HealthProfessionalEducation/SACGHSEducationReport2011.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Sperber NR, Carpenter JS, Cavallari LH, Damschroder LJ, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Denny JC, Ginsburg GS, Orlando LA. Challenges and strategies for implementing genomic services in diverse settings: Experiences from the Implementing GeNomics In pracTicE (IGNITE) network. BMC Medical Genomics. 2017;10(35):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12920-017-0273-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler ZK, Schrader KA, Vijai J, Robson ME, Offit K. Cancer genomics and inherited risk. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(7):687–698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.7271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey A, Febbraro T, Laprise J, Wilbur JS, Lopes Vet Robison K. Adherence patterns to National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Referral of Women with Breast Cancer to Genetics Professionals. American Journal of Cinical Oncology, 2016;39(4):363–367. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussner KM, Jandorf L, Valdimarsdottir HB. Educational needs about cancer family history and genetic counseling for cancer risk among frontline healthcare clinicians in New York City. Genetics in Medicine, 2011;13(9):785–793. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821afc8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar D, Tseng TS, Foster M, Xu L, Chen LS. Genetics/genomics education for nongenetic health professionals: Asystematic literature review. Genetics in Medicine. 2017;19(7):725–732. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Streisand R, Lerman C. Psychological issues among children of hereditary breast cancer gene (BRCA1/2) testing participants. Psychooncology, 2010;10(4):336–346. doi: 10.1002/pon.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez R, Yoon PW, Qureshi N, Green RF, Khoury MJ. Family history in public health practice: A genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:69–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viassolo V, Chappuis PO. Quand faut-il demander une consultation d’oncogénétique? Revue médicale suisse. 2016;12:966–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood ME, Flynn BS, Stockdale A. Primary care physician management, referral, and relations with specialists concerning patients at risk of cancer due to family history. Public Health Genomics, 2013;16(3):75–82. doi: 10.1159/000343790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]