Abstract

We sought to determine whether the intracellular activation of zidovudine (ZDV) varied over time and with previous antiretroviral exposure in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals and to examine whether there is an association between virological responses and intracellular phosphorylation. A total of 23 patients (12 treatment naïve, 11 previously treated with ZDV) who commenced ZDV as part of dual nucleoside therapy were prospectively monitored for 12 months or until withdrawal from the study. No association was observed between virological responses at 2 weeks and 3 months and ZDV phosphorylation. The mean intracellular concentrations of ZDV mono-, di-, and triphosphates did not change significantly over time or with previous ZDV exposure. The rate of formation of total ZDV phosphates was increased in patients with CD4 counts <100 cells/mm3. Previous reports from in vitro cell culture experiments or cross-sectional cohort studies suggesting alterations of ZDV phosphorylation over time are not confirmed by this longitudinal study.

Many factors have been implicated in the failure of antiretroviral therapy. These include the development of drug resistance, insufficient drug potency, poor adherence to treatment, and pharmacokinetic reasons. The pharmacokinetic reasons appear to be important with protease inhibitors since considerable interindividual variability exists and the potential for drug interaction is significant. Reduced activity of the phosphorylating enzymes has been implicated in resistance to the nucleoside analogues (1, 2, 7). Zidovudine (ZDV) is sequentially phosphorylated to its monophosphate (ZDVMP) form (by thymidine kinase), then to its diphosphate (ZDVDP) form, and finally to the active triphosphate (ZDVTP) compound, which competes with the endogenous nucleoside dTTP to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcriptase. There is marked interindividual variability in ZDV phosphorylation (3, 9). It is unclear whether drug phosphorylation is altered over time or with prior exposure to other nucleoside analogues. Several in vitro studies have suggested that changes in ZDV phosphorylation develop over time; these were associated with reduced drug activity and may develop before the emergence of drug-resistant virus (2; M. D. Hill, S. K. Miles, E. Gomperts, J. S. Holcenberg, L. Woods, and V. I. Aramis, Int. Conf. AIDS, abstr. TH.B.36, 1991). Studies with HIV-infected individuals also support the notion that ZDV may down-regulate its own metabolism during long-term therapy (11; Hill et al., Int. Conf. AIDS). For example, a study of HIV-positive patients observed a modest inverse association between length of time on therapy and formation of total ZDV phosphates (11). Data from the ALTIPHAR study suggested that prior ZDV exposure may have also impaired phosphorylation of stavudine (d4T) and lamivudine (3TC), although the numbers of patients were small (J.-P. Sommadossi, X. Zhou, J. Moore, D. R. Havlir, G. Friedland, C. Tierney, L. Smeaton, L. Fox, D. Richman, and R. Pollard, 5th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infect., 1998). In contrast, another cross-sectional study showed no difference in ZDV phosphorylation between patients receiving long-term therapy and those receiving short-term therapy (9).

Given the marked variability in ZDV activation, it is perhaps not surprising that the data are confusing. In order to address whether ZDV phosphorylation changes over time or with antiretroviral exposure, we undertook a longitudinal study in which we measured the intracellular concentrations of ZDV and its metabolites sequentially over a 12-month period in treatment-naïve as well as previously treated patients starting a new antiretroviral regimen. We also examined whether there are associations between plasma viral load changes and ZDV phosphorylation.

The study described here was conducted prior to the widespread introduction of protease inhibitors. Patients were recruited if they were starting or switching to a new antiretroviral regimen comprising two nucleoside analogues (at least one of which was new to the patient) which included ZDV. In 5 patients, the second drug was 3TC, and the remaining 18 patients received didanosine in addition to ZDV. All patients had normal hepatic and renal functions and were not receiving any medication known to interfere with ZDV pharmacokinetics (e.g., probenecid, rifabutin, or d4T). A total of 23 patients (21 males and 2 females; age range, 29 to 58 years; median age, 38 years) were enrolled in the study. Of these, 12 were treatment naïve, while a further 11 had previously received antiretroviral therapy for 2 to 68 months (median, 12 months; for all patients the therapy comprised a ZDV-containing regimen). Five patients were asymptomatic at enrollment, and the remaining 18 patients had AIDS. Patients were not receiving a ZDV-containing regiment at the time of entry into the study. The study was approved by the Liverpool and Manchester Hospital Ethics Research Committees, and written informed consent was obtained.

To evaluate changes in ZDV phosphorylation over 1 year, patients were monitored at the baseline, 2 weeks, and 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Blood samples (24 ml) were drawn at 0, 1, and 2 h following supervised ingestion of ZDV (300 mg). The area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 2 h (AUC0–2) was used since we have found a close correlation between the AUC0–6 and the AUC0–2 in patients who have taken part in previous studies (3, 4, 13) (for total phosphates, r2 = 0.82, n = 40, and P < 0.001; for ZDVTP, r2 = 0.60, n = 40, and P < 0.001). Not all patients were able to provide cells at each visit, and the numbers of patients sampled at each visit are shown in Fig. 1.

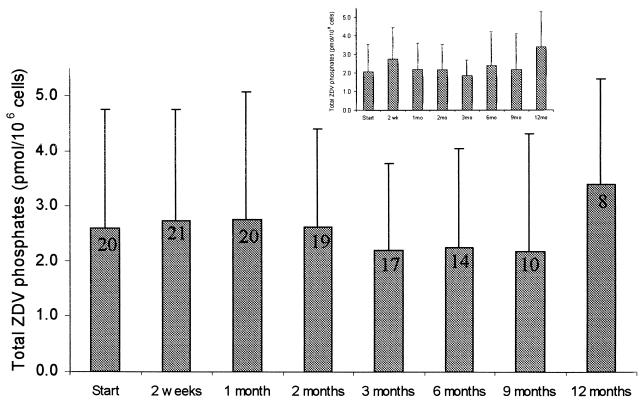

FIG. 1.

Effect of time on total intracellular ZDV phosphate concentrations for all patients in the study. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The inset shows the effect of time on total ZDV phosphate concentrations in patients who completed the trial to 12 months. The data on each bar represent the number of evaluable patients.

Nine of the 23 HIV-positive patients enrolled in the study completed ZDV therapy for 12 months, and phosphorylation data were available for only 8 of these patients. The median baseline HIV RNA load was 5.64 log10 copies/ml (range, 4.23 to 6.61 log10 copies/ml), and the median CD4 count was 60 cells/mm3 (range, <10 to 504 cells/mm3). During the course of follow-up, 14 patients withdrew from the study; this was due to treatment failure (n = 6) or drug toxicity (n = 5) that required discontinuation of ZDV or other reasons (n = 3).

Both plasma and intracellular ZDV concentrations were measured at 0, 1, and 2 h (radioimmunoassay [RIA]; Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density cushion centrifugation as described previously (3). Cells (5 × 106) were extracted overnight with 60% methanol prior to separation by high-performance liquid chromatography. Briefly, samples were eluted on a Partisil 10-SAX anion-exchange column at times corresponding to ZDV, ZDVMP, ZDVDP, and ZDVTP by using collection periods determined from the retention times of authentic phosphorylated anabolites of ZDV (4). Phosphorylated fractions were hydrolyzed and purified, and ZDV levels were quantified by RIA as validated previously (4). The concentrations (nanograms · milliliter−1) determined by RIA were converted to intracellular concentrations (picomoles per 106 cells) by correcting for sample volume and cell number. The assay had a 0.2-ng · ml−1 lower limit of detection, corresponding to 0.01 pmol/106 cells. The HIV type 1 (HIV-1) RNA load was measured (NASBA-QT assay; Organon Teknika) at each visit. Treatment response was defined as a ≥1.5-log drop in viral load at 3 months of treatment.

On the basis of a standard deviation of 50% for ZDVTP in previous studies (3, 4), we determined that recruitment of 21 patients would give a power of 80% to detect a difference of 30% in the ZDVTP concentration between the baseline and other time points (two-sided α = 0.05). At 12 months the power to detect the same difference was reduced to 40% due to the reduced sample size. The AUC0–2 values for all ZDV metabolites were determined by noncompartmental modeling by using the linear trapezoid rule (TOPFIT computer software; Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany). Phosphorylation data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis for changes in intracellular ZDV phosphate levels and CD4 counts with time was performed by Cuzick's test for trend. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess differences in the concentrations of ZDV phosphorylated metabolites between antiretroviral-naïve patients and patients previously treated with ZDV. Data were also analyzed to investigate if there were any differences in intracellular ZDVTP concentrations between patients who achieved a virological response and those who did not respond (Mann-Whitney U test).

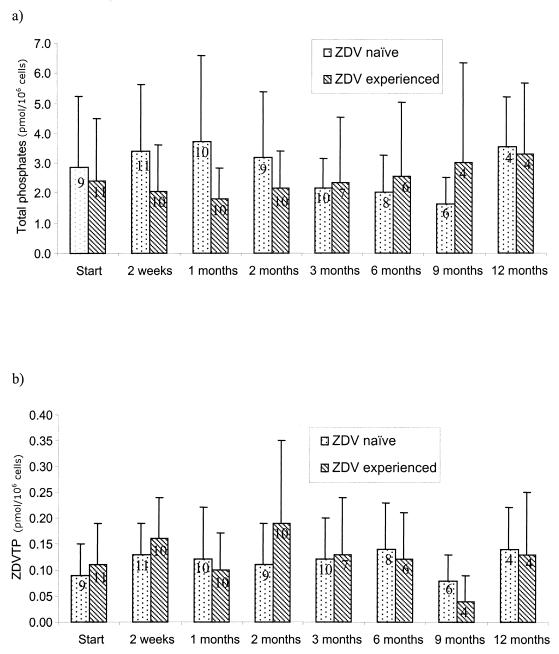

No significant decrease in the AUC0–2 for total intracellular ZDV phosphate was observed over the 12 months (P = 0.863) (Fig. 1 and 2a). There was no significant change in the mean intracellular AUC0–2 values for ZDVMP (P = 0.899), ZDVDP (P = 0.349), and ZDVTP (P = 0.726) (Fig. 2b) during the course of the study. In all patients, the major intracellular metabolite was ZDVMP, with smaller amounts of ZDVDP and ZDVTP detected (Table 1). The intracellular phosphorylation in the eight patients who completed 12 months of follow-up did not differ from that in the other patients, suggesting that patient withdrawal did not select out a population of patients with different phosphorylation profiles (Fig. 1, inset). The intracellular AUC0–2 values for total ZDV phosphates, ZDVMP, ZDVDP, and ZDVTP did not differ between treatment-naïve patients and patients previously treated with ZDV at enrollment or over the course of 12 months of follow-up (Fig. 2; Table 1).

FIG. 2.

AUC0–2 values for total intracellular ZDV phosphates (a) and ZDVTP in ZDV-naïve patients and patients previously treated with ZDV. Data are expressed as the the mean ± standard deviation. The data on each bar represent the number of evaluable patients.

TABLE 1.

Comparison between plasma ZDV concentrations, intracellular phosphate concentrations, and viral loads in ZDV-naïve patients and patients previously treated with ZDV at the start, 3 months, and 12 months of ZDV therapya

| ZDV-naïve patients | ZDV-experienced patients | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–2 (μmol/liter · h) for ZDV in plasma | |||

| 0 mo | 4.70 ± 3.68 (10)b | 3.74 ± 2.66 (11)b | 0.654 |

| 3 mo | 5.59 ± 4.24 (10) | 4.55 ± 2.31 (7) | 0.807 |

| 12 mo | 4.55 ± 2.38 (5) | 4.21 ± 1.52 (4) | 0.730 |

| AUC0–2 (pmol/106 cells · h) for ZDVMP | |||

| 0 mo | 2.52 ± 2.27 (9) | 1.93 ± 2.00 (11) | 0.656 |

| 3 mo | 1.77 ± 0.93 (10) | 1.95 ± 2.12 (7) | 0.601 |

| 12 mo | 3.08 ± 1.65 (4) | 3.01 ± 2.30 (4) | 0.886 |

| AUC0–2 (pmol/106 cells · h) for ZDVDP | |||

| 0 mo | 0.27 ± 0.14 (9) | 0.27 ± 0.17 (11) | 0.897 |

| 3 mo | 0.25 ± 0.13 (10) | 0.24 ± 0.14 (7) | 0.759 |

| 12 mo | 0.31 ± 0.10 (4) | 0.22 ± 0.12 (4) | 0.286 |

| AUC0–2 (pmol/106 cells · h) for ZDVTP | |||

| 0 mo | 0.09 ± 0.06 (9) | 0.11 ± 0.08 (11) | 0.752 |

| 3 mo | 0.12 ± 0.08 (10) | 0.13 ± 0.11 (7) | 0.792 |

| 12 mo | 0.14 ± 0.08 (4) | 0.13 ± 0.12 (4) | 0.543 |

| Viral load change (Δlog10) | |||

| 2 wk | −2.14 ± 0.81 (11) | −0.61 ± 0.83 (9) | 0.002 |

| 3 mo | −2.08 ± 1.05 (10) | −0.60 ± 0.67 (6) | 0.018 |

Differences between ZDV-naïve patients and experienced patients previously treated with ZDV were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (number of patients).

We observed considerable interindividual variability in formation of total ZDV phosphates (Fig. 1 and 2; Table 1). There was also marked within-individual variability; for example, there was a median sixfold difference between the highest and lowest values within each patient over the time course of the study. Only a very weak correlation was observed between the AUC0–2 for plasma ZDV levels and that for total intracellular ZDV phosphate levels. No differences in plasma ZDV levels were observed over time or between treatment-naïve patients or experienced patients previously treated with ZDV.

As expected, the mean reduction in HIV-1 RNA levels following treatment was significantly greater in treatment-naïve patients than in patients previously treated with ZDV (Table 1) (5). At 3 months, treatment-naïve patients showed a 2.08-log drop in viral load, whereas previously treated patients showed a 0.6-log drop. No difference in the AUC0–2 for ZDVTP was observed between virological responders (n = 7; mean AUC0–2 for ZDVTP, 0.11 ± 0.06 pmol/106 cells · h) and nonresponders (n = 9; mean AUC0–2 for ZDVTP 0.14 ± 0.11 pmol/106 cells · h) (P = 0.500).

The AUC0–2 for ZDVMP at the baseline was 1.35 ± 1.26 pmol/106 cells · h for patients with CD4 counts >100/mm3 (n = 9), whereas it was 2.89 ± 2.73 pmol/106 cells · h for patients with CD4 counts ≤100/mm3 (n = 14) (P = 0.051). At 1 month, values were 1.64 ± 1.23 pmol/106 cells · h (n = 14) and 3.63 ± 3.66 pmol/106 cells · h (n = 9), respectively (P = 0.048). Patients experienced a median increase in CD4 counts of 179 cells/mm3 after 12 months of therapy (P = 0.003).

No other study has previously assessed changes in ZDV phosphorylation over time, although several cross-sectional studies have assessed drug phosphorylation in different groups of patients (9, 11; Sommadossi et al., 5th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infect.). Since this study was conducted prior to the widespread use of protease inhibitors, we were able to examine the effect of ZDV phosphorylation in the absence of a protease inhibitor or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

No systematic change in the intracellular activation of ZDV was seen over the 12 months of the study (Fig. 1). No differences over time were observed in the AUC0–2 for total intracellular ZDV phosphates or the three ZDV metabolites, ZDVMP, ZDVDP, and ZDVTP (Table 1). There was also no difference in ZDV phosphorylation between patients previously exposed to ZDV and treatment-naïve patients, with both groups having similar levels of the active triphosphate anabolite (ZDVTP). As reported previously (3, 11, 12), the plasma ZDV concentration bears little relationship to the active intracellular ZDVTP concentrations, suggesting that cellular concentrations of ZDV phosphates approach concentrations sufficient to saturate the phosphorylation enzymes.

These data are consistent with the findings of Peter and Gambertoglio (9), who showed no difference in the formation of ZDVTP within peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients receiving long-term (>18 months) and short-term (<2 months) ZDV treatment (4), but are in contrast to the findings presented in other published work (2, 11, 14; Hill et al., Int. Conf. AIDS). This may be in part because in vitro cell culture with laboratory strains of HIV may not accurately reflect cellular changes in phosphorylating enzyme levels over time. Cross-sectional clinical studies may also select subgroups of patients who respond differently to ZDV or who have differences in host characteristics (e.g., immunological activation) or viral loads. The large inter- and intraindividual variabilities seen also make these studies difficult to interpret.

As expected, treatment-naïve patients experienced greater viral load reductions compared to those for patients previously exposed to ZDV. There was no difference in ZDV phosphorylation between treatment responders and nonresponders. This does not necessarily imply that formation of intracellular ZDVTP bears little relationship to therapeutic efficacy. We did not examine the phosphorylation of the second nucleoside analogue used, nor was any virological resistance testing performed. Furthermore, data from other studies (6, 8) illustrate that the intracellular endogenous dTTP should be assayed in addition to ZDVTP to investigate the competition between ZDVTP and dTTP. Development of new assays will allow measurement of the concentrations of both compounds (10) in future studies. Other conflicting factors may also be important. For example, we have previously demonstrated that patients with low CD4 counts (below 100 cells/mm3) have increased intracellular concentrations of ZDVMP (3).

Our data from a longitudinal study provide the strongest evidence to date that ZDV phosphorylation is not altered significantly over time and is not altered between previously treated with ZDV and ZDV-naïve patients. Further studies should concentrate on defining the relationship between nucleoside analogue triphosphates, their corresponding endogenous nucleoside triphosphates, and virological and immunological responses to treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonelli G, Turriziani O, Verri A, Narcisco P, Ferri F, D'Offizi G, Dianzani F. Long-term exposure to zidovudine affects in vitro and in vivo the efficiency of phosphorylation of thymidine kinase. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:223–228. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avramis I A, Kwock R, Solorzano M M, Gomperts E. Evidence of in-vitro development of drug resistance to azidothymidine in T-lymphocytic leukaemia cell lines (Jurkat E6–1/AZT-100) and in pediatric patients with HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:1287–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry M, Wild M, Veal G, Back D, Breckenridge A, Fox R, Beeching N, Nye F, Carey P, Timmins D. Zidovudine phosphorylation in HIV-infected patients and seronegative volunteers. AIDS. 1994;8:F1–F5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry M, Khoo S H, Veal G, Hoggard P G, Gibbons S E, Wilkins E G L, Williams O, Breckenridge A M, Back D J. The effect of zidovudine dose on the formation of intracellular phosphorylated metabolites. AIDS. 1996;10:1361–1367. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeks S G. Determinants of virological response to antiretroviral therapy: implications for long-term strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 2):S177–S184. doi: 10.1086/313855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao W-Y, Johns D G, Mitsuya H. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of hydroxyurea in combination with 2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:767–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsson B, Britton S, He Q, Karlsson A, Eriksson S. Decreased thymidine kinase levels in peripheral blood cells from HIV-seropositive individuals: implications for zidovudine metabolism. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:805–811. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lori F, Malykh A, Cara A, Sun D, Weinstein J N, Lisziewicz J, Gallo R C. Hydroxyurea as an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 replication. Science. 1994;266:801–805. doi: 10.1126/science.7973634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peter K, Gambertoglio J. Zidovudine phosphorylation after short-term and long-term therapy with zidovudine in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:168–176. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phiboonbanakit D A, Barry M G, Back D J. Quantification of intracellular zidovudine triphosphate by enzymatic assay. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:294P. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stretcher B N, Pesce A J, Murray J A, Hurtubise P E, Vine W H, Frame P T. Concentrations of phosphorylated zidovudine (ZDV) in patient leucocytes do not correlate with ZDV dose or plasma concentrations. Ther Drug Monit. 1991;13:325–331. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stretcher B N, Pesce A J, Frame P T, Greenberg K A, Stein D S. Correlates of zidovudine phosphorylation with markers of HIV disease progression and drug toxicity. AIDS. 1994;8:763–769. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wattanagoon Y, Na Bangchang K, Hoggard P G, Khoo S H, Gibbons S E, Phiboonbanakit D, Karbwang J, Back D J. Pharmacokinetics of zidovudine phosphorylation in human immunodeficiency virus-positive Thai patients and healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1986–1989. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1986-1989.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu S, Liu X, Solorzano M, Kwock R, Avramis V I. Development of zidovudine (AZT) resistance in Jurkat T-cells is associated with decreased expression of the thymidine kinase (TK) gene and hypermethylation of the 5′ end of human TK gene. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;8:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]