Graphical abstract

Keywords: Colorimeter, Colorimetric analysis, Laser cutting, Mortise and tenon, Arduino, Plug-in circuit

Highlights

-

•

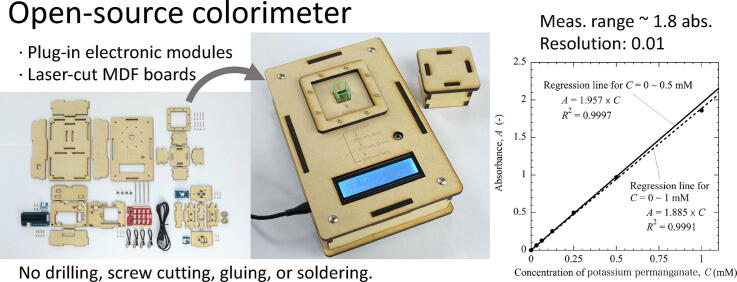

Open-source colorimeter that can be fabricated easily and inexpensively by using items available in online shops.

-

•

No drilling, screw thread cutting, gluing, or soldering of electronic components is required.

-

•

Three different wavelengths of incident light with peaks at 460 nm (blue), 515 nm (green), and 630 nm (red) can be selected.

-

•

Well-designed durable enclosure for improving repeatability and accuracy of measurements.

Abstract

Colorimetric analysis is a fundamental technique for quantifying the concentration of a substance in solution. It is frequently used in primary and secondary education to enhance students’ interest in chemistry, biology, life science, and environmental problems. The structure of the colorimeter is quite simple, i.e., a light source, a sample vessel, and a detector are arranged in a straight line. Therefore, a variety of handmade colorimeters have been reported. However, easy-to-make colorimeters lack portability and reproducibility of measurement, whereas high-precision colorimeters require soldering, which is difficult for beginners. To reduce these difficulties, this study proposes a new open-source colorimeter that can be fabricated easily and cheaply without any soldering. Electronic circuits were made by wiring plug-in electronic modules with connectors. The enclosure was designed to be assembled by simply inserting a laser-cut claws into the corresponding claw holes. The colorimeter was used to measure potassium permanganate solutions of different concentrations and its accuracy was verified. The results showed that the absorbance was measurable up to 1.8 for practical use and 1 for reliable use with the resolution of 0.01.

Specifications table

| Hardware name | Open-source colorimeter |

|---|---|

| Subject area |

|

| Hardware type |

|

| Open Source License | CC BY-NC |

| Cost of Hardware | US $80 |

| Source File Repository |

1. Hardware in context

Colorimetric analysis is a fundamental technique for quantifying the concentration of a substance in solution in physical chemistry and biochemistry. The method is based on Lambert-Beer law, in which the concentration of solutes is measured by using the optical attenuation when monochromatic light passes through a sample solution. When the incident light with an intensity of passes through a sample solution with an optical length of and its intensity is reduced to , the absorbance can be expressed by the following equation:

| (1) |

where is the molar attenuation coefficient and is the molar concentration of the solute. Therefore, the concentration of a given sample can be determined from the absorbance and that is derived from a calibration curve prepared in advance for the solutions with different concentrations.

This analysis has frequently been used in primary and secondary education to increase students’ interest in chemistry, biology, life science, and environmental problems. For example, from the perspective of environmental education, nitrite, one of the causes of air and water pollution, is shown by the quantification of the azo dye coloration produced by the diazo reaction with Saltzman reagent [1]. In biochemical education, the action of digestive enzymes can be demonstrated by the change in color of the iodine solution reacted with starch [2], [3]. Moreover, in educational practices of food chemistry, the presence of sorbic acid, a food preservative, is quantified by the colorimetric determination of the reaction with 2-thiobarbituric acid, whereas the amount of synthetic dye in processed foods is indicated by the change in absorbance of the extract [4], [5].

In a typical colorimeter, a light source, a sample vessel, and a detector are arranged in a straight line. The light from the source passes through the sample in a cuvette and reaches the detector. Because of its simple structure, colorimeters are often made in a classroom by students themselves. The most inexpensive and simple handmade colorimeter consists of a monochromatic LED as a light source and a cadmium sulfide (CdS) photoresistor as a light detector, which are placed in a cardboard or plastic enclosure [6], [7]. Since the CdS decreases the electrical resistance with respect to the luminosity, the change in light intensity can easily be determined by measuring the resistance of the CdS with a voltmeter. These colorimeters are suitable for teaching materials in three aspects: they are inexpensive, easy to make, and have a simple structure that clearly demonstrates its principle. However, clipped electronic circuits and non-durable enclosures of the devices have less portability and poor repeatability of measurements. Furthermore, the production of CdS is decreasing due to European RoHS regulations. Hence, the CdS photoresistor has been replaced by a photodiode with a faster response and better linearity of photocurrent generation as a function of light intensity [8], [9], [10]. To reduce the difficulty of electronic work and enclosure fabrication, colorimeters using the prototyping platform Arduino and a 3D-printed box have also been investigated in previous studies [11], [12]. These handmade colorimeters, which incorporate recent digital fabrication technologies, have a robust structure and better stability of measurements. Most electronic circuits are assembled by connecting electronic components with jumper wires. However, soldering is still partially required. This is a major barrier to build devices for both primary/secondary school students and for electronics beginners.

In this study, we propose an open-source colorimeter that can be fabricated easily and inexpensively without requiring any soldering. A RGB multicolor LED was used as a light source, which allowed colorimetric analysis by selecting one of three different wavelengths of light depending on the sample. A photodiode was adopted as a detector to measure the output voltage depending on the light intensity. The voltage was digitally converted by an Arduino-compatible board and displayed on a liquid crystal display (LCD). The most distinctive feature of this colorimeter is the use of the Grove system [13], which eliminates the difficulties of work to create electronic circuits by simply connecting the electronic elements mounted on the small boards with connectors. The electronic circuit of the colorimeter can be fabricated in a very short time without requiring any soldering at all. The enclosure was designed to be assembled by simply inserting laser-cut claws into the corresponding claw holes in the MDF board. The colorimeter was used to measure potassium permanganate solutions of different concentrations and its accuracy was verified.

2. Hardware description

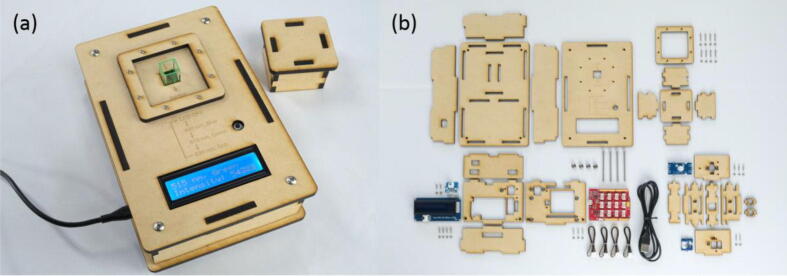

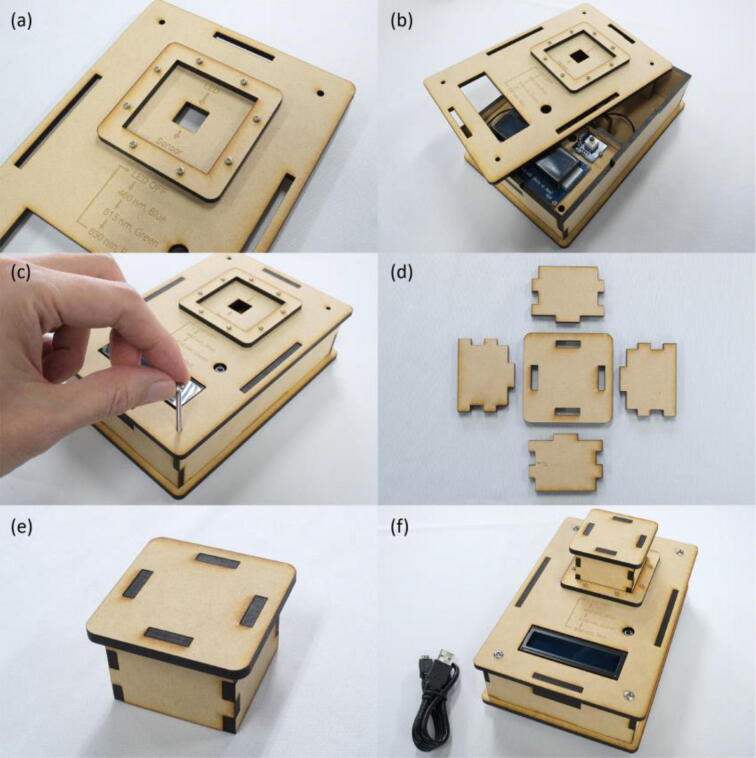

The colorimeter (Fig. 1(a)) was designed to be assembled from commercially available electronic components and MDF boards cut by a laser cutter (Fig. 1(b)). It does not require drilling, screw thread cutting, gluing, or soldering of electronic components.

Fig. 1.

Open-source colorimeter developed in this study. (a) Photo of the colorimeter. (b) All components required for fabrication of the colorimeter.

The electronic circuit of the colorimeter consists of a light source, a photodetector, an Arduino-compatible device, a LCD, and a push button. The Grove system, in which each electronic element is mounted on a small board, allows the construction of the electronic circuit without any soldering, simply by connecting each board with a connector. An RGB multicolor LED was used as the light source, which integrates three different color of LED with peaks at 460 nm (blue), 515 nm (green), and 630 nm (red). A photodiode was used as a photodetector that outputs a voltage from 0 to 5 V depending on the light intensity. The Arduino-compatible device, Seeeduino Lotus, receives the output voltage at the analog input port and performs a 10-bit A/D conversion. The converted values are displayed on the LCD. The push button was used to turn light on and off, and to switch wavelengths. These electronic components were controlled by a house-written software in C language on the Arduino IDE with the help of open source libraries provided by the manufacturer of the Grove system.

The enclosure of the colorimeter was made of laser-cut 4 mm thick MDF boards. The electronic components fastened to the MDF boards with screws and nuts were assembled by inserting the claws into the corresponding claw holes. When a plate is machined by a laser cutter, a claw is thinner than designed, whereas a claw hole is bigger than the drawing due to the cutting allowance. Thus, an assembled claw and claw hole has a gap twice as large as the cutting allowance. In order to eliminate the gap, the cutting allowance was taken into account in the drawing.

In this study, a personal laser cutter, HAJIME (Oh-Laser, Saitama, Japan), controlled by its software, HARUKA (Oh-Laser), was used. It costs approximately US $5000. Even a laser cutter that costs around US $1000 would be sufficient. Another option of cutting MDF boards is to visit a public open workshop called a Fab Lab (Fabrication Laboratory) where digital fabrication tools including a laser cutter are offered. As of April 2020, over 1750 Fab Labs are listed on the website of the Fab Foundation [14].

The colorimeters developed in this study are useful not only for teachers and students in elementary and secondary education, but also for researchers who need simple colorimetric analysis because of the following reasons:

-

•

Easy to fabricate and easy to use.

-

•

Low cost.

-

•

Three different wavelengths of incident light.

-

•

Durable enclosure for improving repeatability and accuracy of measurements.

3. Design files

Design Files Summary

| Design file name | File type | Open source license | Location of the file |

|---|---|---|---|

| ColorimeterKuutamo(A3).pdf | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 | |

| ColorimeterKuutamo(A5).pdf | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 | |

| ColorimeterKuutamo-Offset(A3).pdf | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 | |

| ColorimeterKuutamo-Offset(A5).pdf | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 | |

| Colorimeter_Kuutamo.ino | Arduino .ino | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 |

| Instruction.pdf | CC BY-NC | https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2 |

-

•

ColorimeterKuutamo(A3).pdf: Ready-to-cut file for laser-cutting the colorimeter from an A3-size MDF board.

-

•

ColorimeterKuutamo(A5).pdf: Ready-to-cut file for laser-cutting the colorimeter from an A5-size MDF board.

-

•

ColorimeterKuutamo-Offset(A3).pdf: Ready-to-cut file for laser-cutting the colorimeter from an A3-size MDF board by using the HAJIME laser cutter. By taking the cutting allowance into account, the concave and convex lines were offset by 0.075 mm, respectively.

-

•

ColorimeterKuutamo-Offset(A5).pdf: Ready-to-cut file for laser-cutting the colorimeter from an A5-size MDF board by using the HAJIME laser cutter. By taking the cutting allowance into account, the concave and convex lines were offset by 0.075 mm, respectively.

-

•

Colorimeter_Kuutamo.ino: Program file for Arduino IDE. Open source libraries provided by manufacturer for RGB LED and LCD are required to compile the program.

-

•

Instruction.pdf: The detail build instructions with photos.

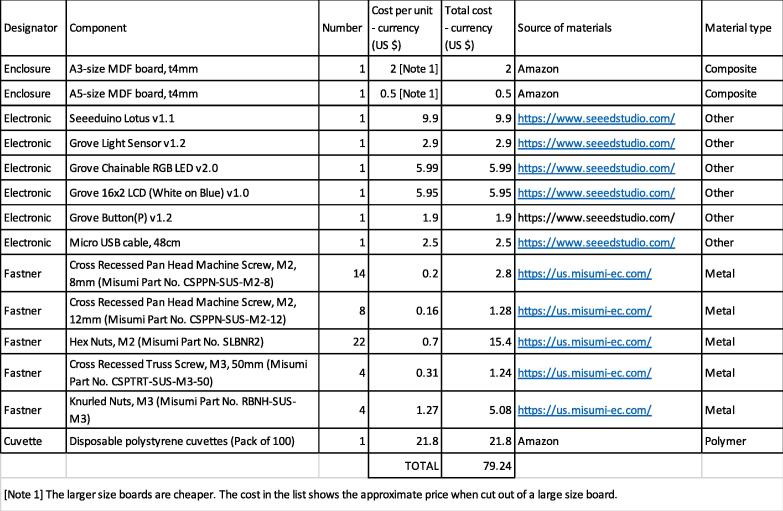

4. Bill of Materials

Bill of Materials

The editable Bill of Materials can be downloaded from the OSF: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/UGVS2

5. Build instructions

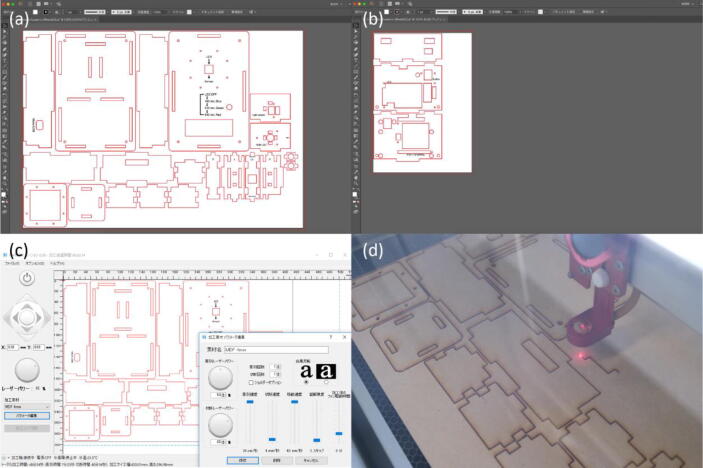

The enclosure and inner structure to which the electronic components of the colorimeter are attached were made of 4-mm thick MDF boards. The design file of the colorimeter was divided into A3- and A5-size drawings (Fig. 2(a)(b)). Each of them was sent to the laser cutter software, HARUKA (Oh-Laser, Saitama, Japan) (Fig. 2(c)). The default cutting parameters for a 4-mm thick MDF board was selected and the boards were cut by using the laser cutter, HAJIME (Oh-Laser) (Fig. 2(d)). The total machine time for processing A3- and A5-size boards were approximately 50 and 12 min, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Instructions of laser-cutting. (a)(b) The design drawings of the enclosure and inner structure of the colorimeter displayed in Adobe Illustrator. (c) The drawings sent to the laser cutter software, HARUKA. (d) MDF board cut by using the laser cutter, HAJIME.

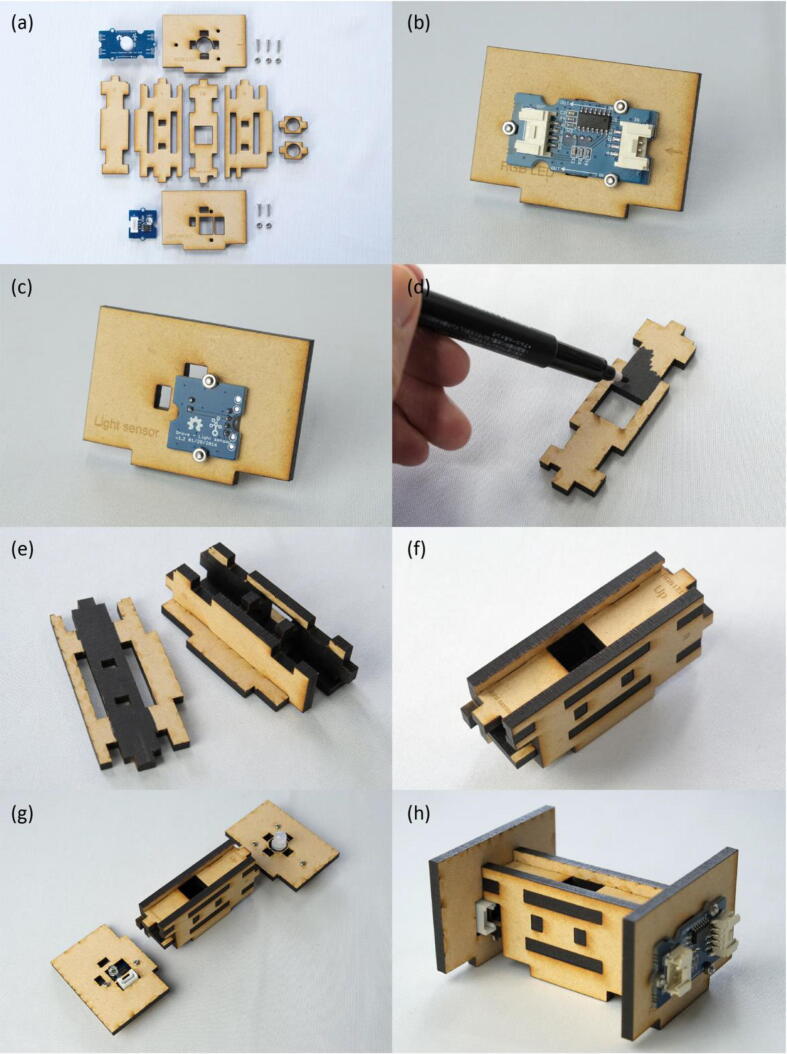

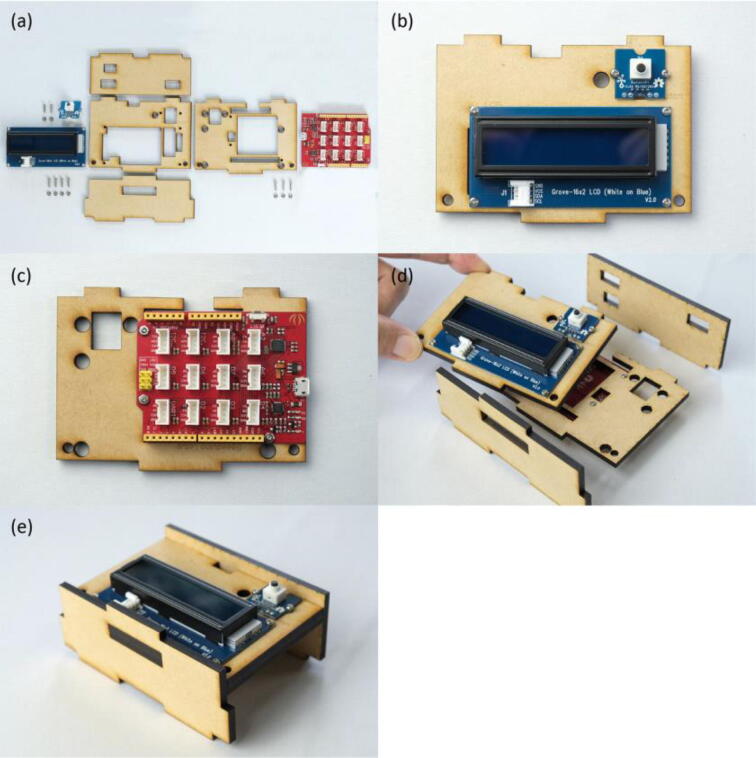

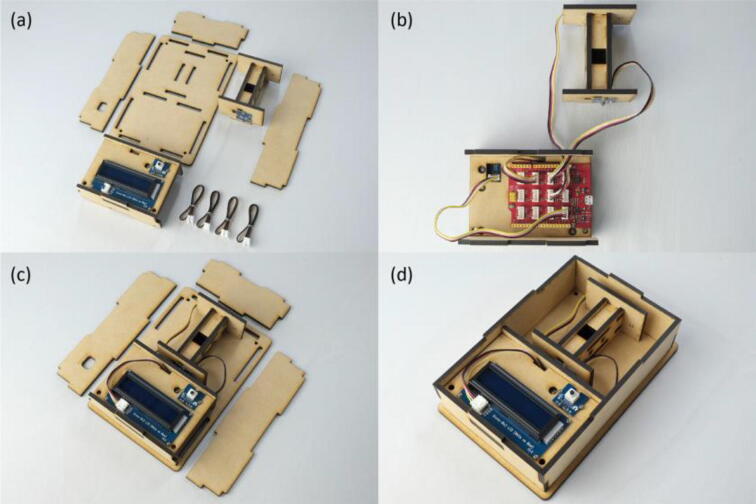

First, the RGB LED and light sensor were fastened onto the MDF boards using M2 screws and nuts (Fig. 3(a)~(c)). By simply fitting claws of the MDF boards into the corresponding claw holes, assembly of the measurement module was finished (Fig. 3(d)~(h)). Next, the Seeeduino Lotus, LCD and push button were screwed onto the MDF boards to form the control module (Fig. 4(a)~(e)). The RGB LED was connected to the D7 socket of Seeeduino Lotus, the light sensor to A0, the LCD to I2C., and the push button to D3, respectively (Fig. 5(a)(b)). Following the wiring, the measurement and control modules, and side plates were inserted into the base plate (Fig. 5(c)(d)). The top plate was then attached and fixed with M3 screws and nuts in the holes at four corners of the enclosure (Fig. 6(a)~(c)). Finally, a shade cover was assembled to prevent disturbance by outside light (Fig. 6(d)~(f)).

Fig. 3.

Build instructions of the measurement module. (a) All components required for making the measurement module. (b) RGB LED fastened onto the MDF board. (c) Light sensor fastened onto the MDF board. (d) To reduce stray light, paint the light path black with an marker. (e) The light path assembled by fitting claws of the MDF boards into the corresponding claw holes. (f) The finished light path. (g) The measurement module consisting of RGB LED, light path, and light sensor. (h) The finished measurement module.

Fig. 4.

Build instructions of the control module. (a) All components required for making the control module. (b) LCD and push button fastened onto the MDF board. (c) Seeeduino Lotus fastened onto the MDF board. (d) The stacked MDF boards inserted into a pair of support boards. (e) The finished control module.

Fig. 5.

Build instructions of the inner structure of the colorimeter. (a) The measurement and control modules, base plate, side plates, and cables. (b) Each electronic components connected to the corresponding sockets of Seeeduino Lotus by cables. (c) The measurement and control modules inserted into the base plate. (d) Side plates inserted into the base plate.

Fig. 6.

Build instructions of the enclosure of the colorimeter. (a) The top plate with the rim for fitting the shade. (b) The top plate on the main body. (c) The enclosure fastened with screws and nuts. (d) MDF boards required for making the shade. (e) The finished shade. (f) The finished colorimeter.

The control program was uploaded to the Arduino compatible board, Seeeduino Lotus, connected to a PC by the following procedure:

-

(1)

Start Arduino IDE, a development environment application for Arduino compatible boards, on your PC.

-

(2)

Download the board manager for Seeeduino Lotus provided by the manufacturer. Install it in the Arduino IDE.

-

(3)

Download open source libraries in ZIP format for RGB LED and LCD provided by manufacturer. Include them in the Arduino IDE.

-

(4)

Connect the Seeeduino Lotus and PC with a micro-USB cable.

-

(5)

Open the control program developed in this study in the Arduino IDE, and select “Seeeduino Lotus” from [Tools] > [Board] menu.

-

(6)

From the [Tools] > [Port] menu, select the appropriate port connected to the board.

-

(7)

Click the Upload button to send the program to Seeeduino Lotus.

The detail instruction with photos is shown in the design file, ‘‘Instruction.pdf”.

6. Operation instructions

-

(1)

Connect a micro-USB cable to the colorimeter to supply power. No PC is required.

-

(2)

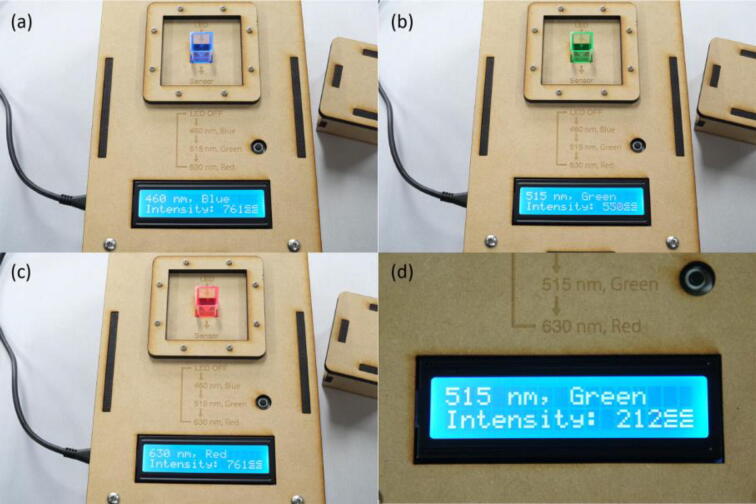

Press the push button to select an appropriate wavelength of light according to the sample solution. Pressing the push button switches the wavelength of light to 460 nm (blue), 515 nm (green), 630 nm (red), and light off (Fig. 7(a)~(c)).

-

(3)

Insert a cuvette containing 2 ml of solvent without solute, usually water, into the measurement port. A common cuvette with a square cross section (inner size: 10 mm × 10 mm, outer size: 12.5 mm × 12.5 mm, optical length: 10 mm) is applicable.

-

(4)

Put the shade cover on the cuvette and read the value displayed on the LCD (Fig. 7(d)). This value corresponds to the intensity of the incident light .

-

(5)

Insert a cuvette containing 2 ml of sample solution to be measured.

-

(6)

Put the shade cover on the cuvette and read the value displayed on the LCD. This value corresponds to the intensity of the transmitted light .

-

(7)

The absorbance is calculated from .

-

(8)

To shut down the system, unplug the micro-USB cable.

Fig. 7.

Operation instructions of the colorimeter. (a)(b)(c) The color of the light changed in the order of blue, green and red by pressing the push button. (d) Output value displayed on the LCD according to the light intensity. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

7. Validation and characterization

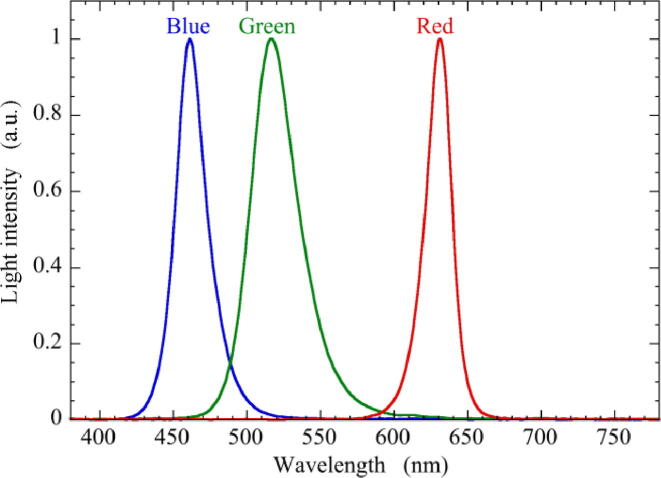

The wavelengths of light emitted from RGB LED were measured by a spectrometer (MK350D, UPRtek Corp., Taiwan). Fig. 8 shows the spectra of blue, green and red light measured in a range of 380–780 nm at a resolution of 1 nm in wavelength. The peak wavelengths of blue, green, and red light were 461, 516, and 631 nm, and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) was 24, 37, and 20 nm, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Spectra of blue, green and red light of RGB multicolor LED measured by a spectrometer. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

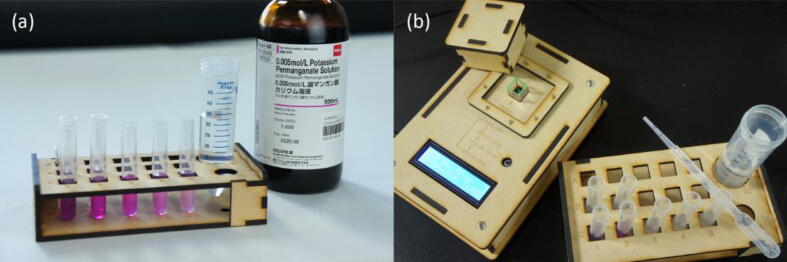

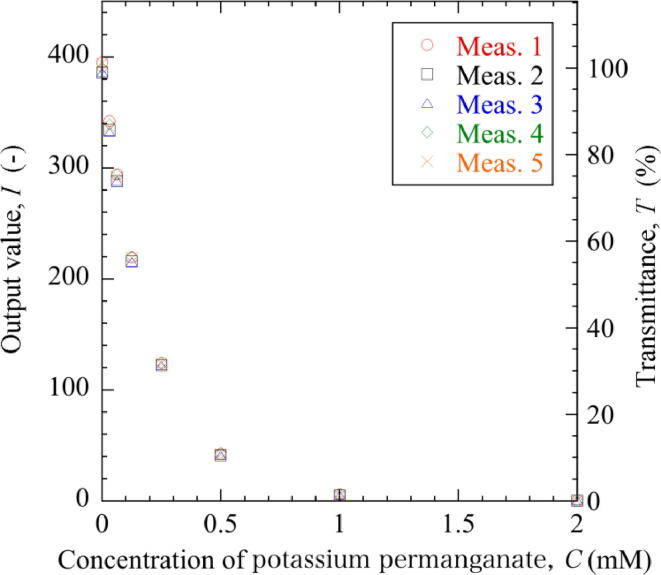

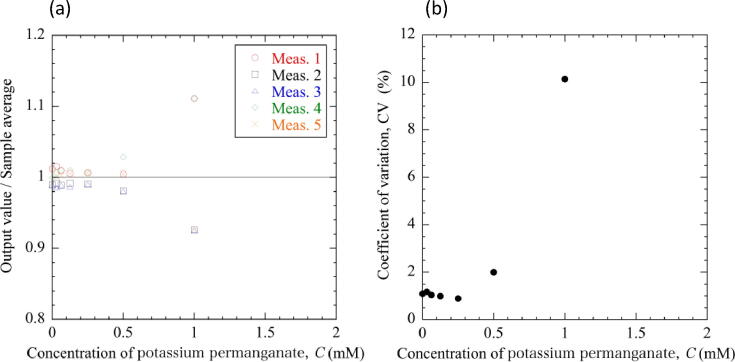

To evaluate the usefulness of the colorimeter, experiments were made using potassium permanganate solution as a model. Potassium permanganate solution was serially diluted with purified water to prepare solutions of 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.0625, and 0.03125 mM (Fig. 9(a)). This solution has a red-purple color. Thus, it absorbs its complementary color, green, making it appear red–purple. Spectroscopically, potassium permanganate is known to have two absorption peaks in green at 525 nm and 545 nm. Therefore, the green LED light at 515 nm was used for the experiments. First, the light intensity transmitted through 2 ml of purified water placed in a cuvette was measured at 515 nm. Then, the diluted potassium permanganate solutions were measured in random order (Fig. 9(b)). The measurements were repeated five times using five independent sets of serially diluted solutions. Fig. 10 shows the relationship between sample concentration, the output value from the colorimeter, and the corresponding transmittance. The output value decreased exponentially with increasing concentration of the sample, and reached 0 at 2 mM. Fig. 11 shows the repeatability of five measurements. The scatter of the output values was within ±3% of the sample average in the range from 0 to 0.5 mM, but increased to approximately ±10% at 1 mM (Fig. 11(a)). The output values were almost equally scattered on both sides of the sample average, and no specificity was observed. The coefficients of variation (CV), that is standard deviation divided by the sample average, was less than 2% at concentrations ranging from 0 to 0.5 mM, but exceeded 10% at 1 mM (Fig. 11(b). The decreased repeatability of the measurement and the increased CV in the higher concentrated solutions would be partly attributed to the quantization effect of the A/D converter. Depending on the light intensity, the photodetector outputted an analogue voltage from 0 to 5 V. This was converted to the digital value from 0 to 1023 by a 10-bit A/D converter on the Arduino-compatible device, Seeeduino Lotus. Therefore, the resolution was 4.88 mV/bit (5/1024 = 0.00488). If the change in the voltage falls below the resolution due to a large absorbance and a small change in light intensity, the difference in absorbance can no longer be detected. The quantization effect of the A/D converter becomes more pronounced with higher absorbance, which would decrease the repeatability of the measurement and increase the CV at 1 mM.

Fig. 9.

Validation of the colorimeter using a model solution. (a) Potassium permanganate solution serially diluted with purified water. (b) The solutions were measured by the colorimeter in random order.

Fig. 10.

Relationship between sample concentration, the output value from the colorimeter, and the corresponding transmittance obtained for five independent series of serially diluted solutions.

Fig. 11.

Repeatability of measurements. (a) Scatter of output values divided by the sample average with respect to the concentration of the sample. (b) Coefficients of variation (CV) of the output values with respect to the concentration of the sample.

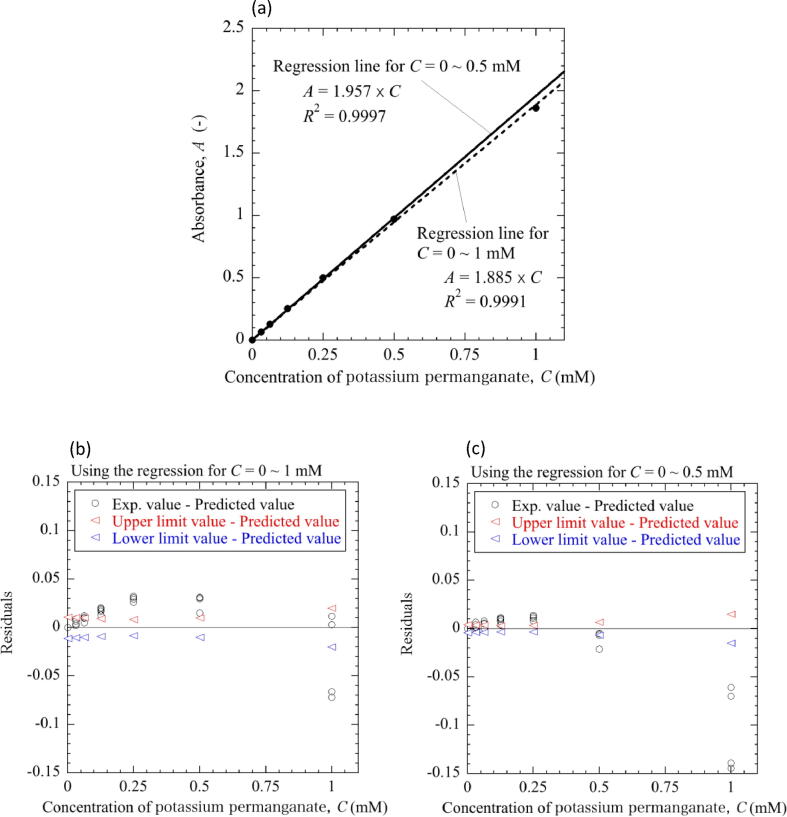

Fig. 12 shows the relationship between the concentration of the sample and the average absorbance obtained from the five measurements. There was a good linear relationship between the concentration and absorbance (Fig. 12(a)). The figure also includes regression lines, or calibration curves, obtained for concentrations in the range of 0 to 0.5 mM (solid line) and 0 to 1 mM (dashed line), respectively. The two regression lines showed high correlation coefficients. However, the absorbance at 1 mM was slightly smaller than that calculated from the solid regression line in the range of 0 to 0.5 mM. In other words, at the concentration higher than 0.5 mM, i.e., at the absorbance greater than 1, the relationship between the concentration and the absorbance deviates from the straight line and becomes a slightly upward convex curve. Furthermore, the differences between the experimental and the predicted absorbance from the regression line, i.e., residuals, were calculated to compare with the 95% confidence intervals. In Fig. 12(b), the residuals obtained by using the regression line for 0–1 mM were comparable to the width of the 95% confidence interval. On the other hand, Fig. 12(c) shows that the experimental absorbance at 1 mM deviated significantly from the confidence interval when the regression line for 0–0.5 mM was used, which indicates that the Lambert-Beer law no longer holds at 1 mM. Although the solutions with absorbance up to 1.8 were measurable by this device as shown in Fig. 12(a), the reliable measurement range is less than 1 in absorbance if the slight deviation from the Lambert-Beer law and the large CV of more than 10% at 1 mM were taken into account.

Fig. 12.

Relationship between the concentration of the sample and the calculated absorbance. (a) Two regression lines obtained for concentrations in the range of 0 to 0.5 mM (solid line) and 0 to 1 mM (dashed line), respectively. The error bars showing the standard deviation of the five measurements were smaller than the size of the black circles. (b) Residuals of the experimental absorbance, the upper and the lower limit values of the 95% confidence intervals obtained by using the regression line for 0–1 mM. (c) Residuals of the experimental absorbance, the upper and the lower limit values of the 95% confidence intervals obtained by using the regression line for 0–0.5 mM.

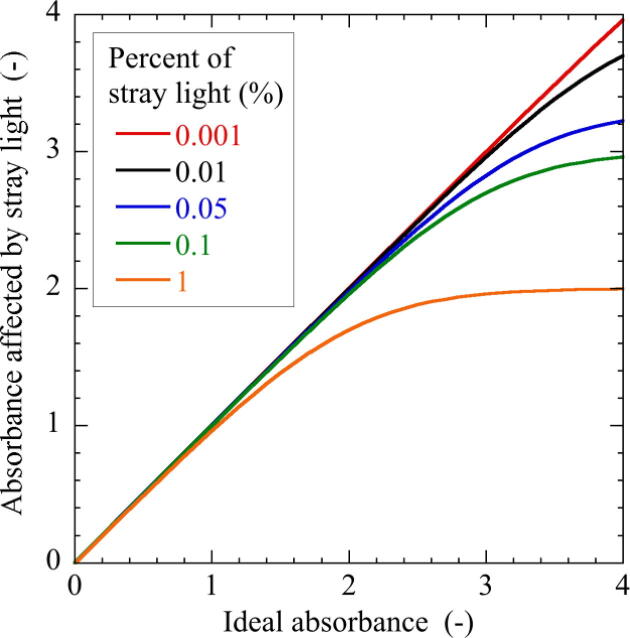

This deviation from the Lambert-Beer law is known to be due to stray light caused by unintended light reflection and scattering on the polystyrene cuvette and light path [15]. Theoretically, colorimetric measurement for a sample with 10% transmittance, i.e., , yields the absorbance of . If the transmitted light contains 0.1% of stray light, the absorbance will result in , which is only 0.00432 (approximately 0.4% of the absorbance ) smaller than that without the stray light. However, if a sample with the lower transmittance of 1% () or the higher absorbance of is measured under the same stray light of 0.1%, the obtained absorbance is , which is 0.041 (approximately 2% of the absorbance ) smaller than the ideal absorbance. Fig. 13 shows the relationship between absorbances in the absence and presence of stray light. The larger the stray light and the larger the absorbance, the greater the error in absorbance. The measurement range of most colorimeters currently available in the market is less than 2 in absorbance. Therefore, the effect of stray light in these products must be kept below 0.1%. Note that even if there is no linear relationship between concentration and absorbance, the device can be used for quantification of concentration as long as a nonlinear calibration curve is prepared prior to measurement.

Fig. 13.

Relationship between absorbances in the absence and presence of stray light.

In order to estimate the effective measurement range of the colorimeter, it is important to consider that the absorbance is calculated by a logarithmic transformation of the output value from a photodiode. If the reading of the output value on a photoelectric detector contains a certain error, the measurement error is constant over the whole range as far as the sample is evaluated with transmittance . However, the error in absorbance cannot be constant because it is logarithmically transformed in the calculation of absorbance. This transformed error has been theoretically analyzed and illustrated by the Twyman-Lothian error curve [16], [17]. The error curve has a downwardly convex, and gives the smallest value at transmittance , i.e., absorbance . In general, the optical working range of colorimetric measurements is considered to be 10–80% in transmittance, i.e., 0.1–1.0 in absorbance because of the large error on either end of this range.

Furthermore, the measurement resolution of the colorimeter developed in this study was investigated by considering the relationship between the resolution of the output value from the photodiode and the calculated absorbance (Table 1). Assuming that the output value of (Fig. 10) for the measurement of solvent changes by the smallest increment of 1, i.e., it becomes 389, the transmittance decreases from 100% to 99.744% by 0.256, while the absorbance increases from 0 to 0.00112 by 0.00112. As the output value changes from 40 to 39 for a 0.5 mM solution, the transmittance decreases from 10.256% to 10% by 0.256, and the absorbance increases from 0.989 to 1 by 0.011. Similarly, when the output value of 6 changes to 5 for a 1 mM solution, the transmittance decreases from 1.538% to 1.282% by 0.256, and the absorbance increases from 1.813 to 1.892 by 0.079. Thus, the measurement resolution in absorbance, which is determined by the combination of the dynamic range of the photodiode and the performance of the A/D conversion, is 0.001 for a sample with absorbance close to 0, but decreases to 0.01 for that with , and further drops to 0.08 for that with .

Table 1.

Measurement resolution of the colorimeter depending on the relationship between the resolution of the output value from the photodiode and the logarithmically transformed absorbance.

| Output value | Transmittance | Absorbance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (-) | ΔI | T = I/I0 × 100 (%) | ΔT | A = −log(I/I0) (−) | ΔA | |

| 390 | (=I0) | 1 | 100.000 | 0.256 | 0 | 0.00112 |

| 389 | 99.744 | 0.00112 | ||||

| 40 | 1 | 10.256 | 0.256 | 0.989 | 0.011 | |

| 39 | 10.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 6 | 1 | 1.538 | 0.256 | 1.813 | 0.079 | |

| 5 | 1.282 | 1.892 | ||||

Finally, the effects of power-on time and ambient temperature on the measurement were examined. The output values from the colorimeter were evaluated at three time points after power-on: immediately after power-on, 0.5, and 2 h. The measurement was repeated five times by using 0.25 mM potassium permanganate solution in five different cuvettes. The ambient temperature was 25 °C. As shown in Table 2, the power-on time had no effects on the values output from the colorimeter. The calculated absorbance was in good agreement independent of the power-on time. The colorimeter and solutions were then left at 4 °C or 40 °C for more than 1 h, and the measurements were made after thermal equilibrium. Compared to the measurements at 25 °C, the output values decreased by 8–9% at 4 °C and increased by 4–5% at 40 °C, which is probably due to temperature characteristics of the electronic components used in the colorimeter. However, regardless of ambient temperature, the obtained absorbance showed no significant differences.

Table 2.

Effects of power-on time and ambient temperature on the output values from the colorimeter and the calculated absorbance (Mean ± standard deviation, n = 5).

| Output value |

Absorbance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I0 (Blank) | I (0.25 mM) | A = −log(I/I0) | ||

| Power-on time (at 25 °C) | 0 h | 405.2 ± 8.0 | 133.8 ± 4.9 | 0.481 ± 0.0081 |

| 0.5 h | 403.2 ± 8.2 | 132.6 ± 5.2 | 0.483 ± 0.0085 | |

| 2.0 h | 404.0 ± 9.2 | 132.6 ± 5.2 | 0.484 ± 0.0073 | |

| Temperature | 4 °C | 371.4 ± 7.2 | 121.2 ± 4.6 | 0.487 ± 0.0081 |

| 40 °C | 421.2 ± 8.3 | 139.2 ± 5.3 | 0.481 ± 0.0078 | |

Overall, the measurement range of the colorimeter developed in this study is practically up to 1.8 and highly reliable up to 1 in absorbance. Taking into account the minimum increment of the output values from the colorimeter, the measurement resolution is 0.01 for absorbances less than 1. Compared to previous reports, in which some studies have only attempted measurements of absorbance up to 0.5 [6], [7], [11], [12], [18], while others have shown the linearity even at absorbance greater than 1 [8], [10], [19], [20], the performance of our colorimeter was superior to or comparable to that of the previous handmade colorimeters.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17K18652.

References

- 1.W. Xiangyang, H. Zhixiang, Z. Zhen, L. Guoxi, D. Xing In 2018 3rd International Conference on Education, E-learning and Management Technology (EEMT 2018); Atlantis Press: 2018.

- 2.M. B. V. Roberts, T. J. King, Biology: A Functional Approach. Students' Manual; Nelson, 1987.

- 3.A. Šorgo, Z. Hajdinjak, D. Briški, The journey of a sandwich: computer-based laboratory experiments about the human digestive system in high school biology teaching, Adv. Physiol. Educ., 32 (2008) 92-99. doi:10.1152/advan.00035.2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hughes B. Assembly and validation of a colorimeter. Technol. Eng. Teacher. 2013;72:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.J. Adds, E. Larkcom, Tools, Techniques and Assessment in Biology: A Course Guide for Students and Teachers; Nelson, 1999.

- 6.J. Gordon, A. James, S. Harman, K. Weiss, A Film Canister Colorimeter, J. Chem. Educ., 79 (2002) 1005. doi:10.1021/ed079p1005.

- 7.J. Gordon, S. Harman, A Graduated Cylinder Colorimeter: An Investigation of Path Length and the Beer-Lambert Law, J. Chem. Educ., 79 (2002) 611. doi:10.1021/ed079p611.

- 8.C. M. Clippard, W. Hughes, B. S. Chohan, D. G. Sykes, Construction and Characterization of a Compact, Portable, Low-Cost Colorimeter for the Chemistry Lab, J. Chem. Educ., 93 (2016) 1241-1248. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00729.

- 9.Y. Suzuki, T. Aruga, H. Kuwahara, M. Kitamura, T. Kuwabara, S. Kawakubo, M. Iwatsuki, A Simple and Portable Colorimeter Using a Red-Green-Blue Light-Emitting Diode and Its Application to the On-Site Determination of Nitrite and Iron in River-water, Analytical Sciences, 20 (2004) 975-977. doi:10.2116/analsci.20.975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Albert D.R., Todt M.A., Davis H.F. A low-cost quantitative absorption spectrophotometer. J. Chem. Educ. 2012;89:1432. [Google Scholar]

- 11.L. A. Porter, B. M. Washer, M. H. Hakim, R. F. Dallinger, User-Friendly 3D Printed Colorimeter Models for Student Exploration of Instrument Design and Performance, J. Chem. Educ., 93 (2016) 1305-1309. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00041.

- 12.C. G. Anzalone, G. A. Glover, M. J. Pearce, Open-Source Colorimeter, Sensors, 13 (2013) doi:10.3390/s130405338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Grove System, http://wiki.seeedstudio.com/Grove_System/, (accessed April 4th, 2020).

- 14.Fab Foundation, https://www.fabfoundation.org/, (accessed April 15th, 2020).

- 15.R. B. Cook, R. Jankow, Effects of stray light in spectroscopy, J. Chem. Educ., 49 (1972) 405. doi:10.1021/ed049p405.

- 16.N. T. Gridgeman, Reliability of Photoelectric Photometry, Anal. Chem., 24 (1952) 445-449. doi:10.1021/ac60063a003.

- 17.R. H. Hamilton, Photoelectric Photometry An Analysis of Errors at High and at Low Absorption, Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Analytical Edition, 16 (1944) 123-126. doi:10.1021/i560126a019.

- 18.J. R. Hamilton, J. S. White, M. B. Nakhleh, Development of a Low-Cost Four-Color LED Photometer, J. Chem. Educ., 73 (1996) 1052. doi:10.1021/ed073p1052.

- 19.J. J. Wang, J. R. Rodríguez Núñez, E. J. Maxwell, W. R. Algar, Build Your Own Photometer: A Guided-Inquiry Experiment To Introduce Analytical Instrumentation, J. Chem. Educ., 93 (2016) 166-171. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00426.

- 20.Asheim J., Kvittingen E.V., Kvittingen L., Verley R., Simple A. Small-scale lego colorimeter with a Light-Emitting Diode (LED) used as detector. J. Chem. Educ. 2014;91:1037–1039. doi: 10.1021/ed400838n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]