Abstract

In this paper, two new general families of distributions supported on the unit interval are introduced. The proposed families include several known models as special cases and define at least twenty (each one) new special models. Since the list of well-being indicators may include several double bounded random variables, the applicability for modeling those is the major practical motivation for introducing the distributions on those families. We propose a parametrization of the new families in terms of the median and develop a shiny application to provide interactive density shape illustrations for some special cases. Various properties of the introduced families are studied. Some special models in the new families are discussed. In particular, the complementary unit Weibull distribution is studied in some detail. The method of maximum likelihood for estimating the model parameters is discussed. An extensive Monte Carlo experiment is conducted to evaluate the performances of these estimators in finite samples. Applications to the literacy rate in Brazilian and Colombian municipalities illustrate the usefulness of the two new families for modeling well-being indicators.

Keywords: Extended Weibull distribution, maximum likelihood estimation, moments, unit distributions, well-being indicators

AMS CLASSIFICATION: 60E05

1. Introduction

When analyzing the standard of living elements, Sen [25] claimed that a ‘good life’ could be measured through indicators that consider the actual outcome of peoples' decisions and also their capabilities (opportunities they have). The gross domestic product is usually used as a proxy for capabilities, and social indicators to measure actual outcomes (see Royuela and García [23]). The list of well-being indicators may include several double bounded random variables, such as infant mortality, literacy and murder rates, telephone, television, and internet availability, and human development index. Those indicators also represent essential aspects of the international development agenda [28]. In this context, it is necessary to consider probability distributions that take those characteristics into account.

Some double bounded distributions that have been widely studied in the literature are the classical Beta and Kumaraswamy (Kw) distributions. Much theoretical work has been concentrated on the use of those models. However, the beta and Kw distributions are not always suitable for modeling well-being indicators (see Section 7). On the other hand, only a few papers have dealt with distributions supported on the unit interval. Gómez-Déniz et al. [6] studied the log-Lindley distribution. Mazucheli et al. [14] discussed the unit Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. Mazucheli et al. [12] defined the unit-Lindley distribution, and Ghitany et al. [5] the unit inverse-Gaussian distribution. Recently, Altun and Cordeiro [2] introduced the unit-improved second-degree Lindley distribution.

In this paper, we introduce a new family of distributions for modeling random variables with support on the unit domain. The so-called unit extended Weibull ( ) family may also be considered to model double bounded variate. We provide a comprehensive account of the mathematical properties of the proposed family of distribution. The new family of distributions provides a rich source of alternative distributions for analyzing bounded data. Additionally, the complementary unit extended Weibull ( ) is also derived. We note five motivations for the proposed families of distributions:

The proposed families define at least forty new special models;

Some distributions commonly used for parametric models on the unit interval are special cases of the proposed families, such as the unit Weibull [15,16] distribution;

The expected value of the proposed models can be obtained in closed form;

The proposed family of distributions is median-parametrized, facilitating the interpretation of its location parameter;

Simulations and real data sets show the good performance of these new models (see Section 7).

The proposed families are obtained from a variable transformation in the extended Weibull ( ) class of distributions, pioneered by [8]. Its cumulative distribution function (cdf) is given by

| (1) |

where and is a non-negative monotonically increasing function which depends on the parameter vector . The corresponding probability density function (pdf) is given by

| (2) |

where is the derivative of with respect to x. We emphasize that several well-known distributions can be obtained from different expressions of and refer the reader to [24] for a detailed survey on the special models, with corresponding and functions. Nadarajah and Kotz [21] and Pham and Lai [22] also give more details on this family.

The applicability for modeling well-being indicators is the major practical motivation for introducing the distributions on those families. Section 7 illustrates their relevance by means of applications on the Brazilian and Colombian citizens' literacy rates. Literacy levels are related to quality education and have been an international concern. At the World Education Forum, in Dakar, Senegal, 2000, 164 governments signed a global commitment to provide quality basic education for all children, youth, and adults. One of the Dakar's six goals was halving illiteracy rate by 2015. By adopting these goals, Brazil and Colombia joined the group of countries committed to this achievement [30]. This variable is also a useful indicator of poverty, often considered to evaluate the overall standard of living in a country. Messias [17] verified that this variable is strongly associated with life expectancy in Brazil. Ahnen [1] emphasize that the literacy rate can be a control variable to Brazilian police violence. Massa [11] have found statistically significant associations between self-rated health and area-level literacy rates in adults from the 27 Brazilian capitals. Finally, Royuela [23] consider it to examine quality life convergence in Colombia.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we define the new families. Section 3 provides some general properties, and Section 4 the parameter estimation by maximum likelihood. Section 5 presents some special distributions obtained from the class. Some general properties and a simulation study of a special model is presented in Section 6. Empirical applications and concluding remarks are presented in Sections 7 and 8, respectively.

2. The unit extended Weibull family

Let X be a non negative random variable which follows a distribution with cdf and pdf in (1) and (2), respectively, and denote . By considering the transformation we derive the class of distributions. Thus, the cdf of the new family is

| (3) |

where , is a shape parameter, and is obtained by taking this transformation in the random variable X. In the supplementary material, we prove that α is a location and scale-invariant measure. The vector is a vector of shape parameters that depend on the chosen function. We develop a shiny application to provide interactive plots and illustrate the density shapes of some special cases upon variations in 1

The pdf corresponding to (3) is

| (4) |

where is the derivative of with respect to x evaluated in . Hereafter, let Y be a random variable having the pdf (4) with parameters α and , say The quantile function (qf) of the family can be expressed in terms of , which is the inverse function of . Therefore, the qf of Y has the form

| (5) |

The quantities , , and the corresponding parameter vectors for some special models are presented in the paper supplementary material. By replacing these quantities in (4), we obtain a new unit distribution on the family.

Next, we provide a different parameterization of the class distributions, in which one of its parameters corresponds to the median. The proposition below refers to the median-based parameterization.

Proposition 2.1

Let Y be a random variable with cdf given by

(6) where . Then Y belongs to the class of distributions, and is a location parameter which corresponds to the median of Y.

Proof.

The results hold by setting in Equation (3) to get (6). Therefore, the qf of Y is given by

(7) and it follows that, by taking u = 0.5 in Equation (7), μ is the median of Y. This completes the proof.

The pdf of Y can be written in the median-based parameterization as

where .

Analogously, let and now consider the transformation

Under the above transformation, we may derive the class of distributions. A similar approach was considered by [7] for obtaining a second kind of unit-Gamma distribution. Note that the family can also be derived by taking the transformation Z = 1−Y. Thus, the cdf of this alternative unit family is

| (8) |

and the corresponding pdf reduces to

| (9) |

where is the derivative of with respect to x evaluated in Hereafter, let Z be a random variable having the pdf (9) with parameters α and , say The qf of Z has the form

| (10) |

The quantities , , and the corresponding parameter vectors for some special models are presented in the paper supplementary material. By replacing these quantities in (9), we obtain a new unit distribution on the family.

The following result shows an alternative parametrization of the class of distributions, in which one of its parameters corresponds to the median of the random variable Z.

Proposition 2.2

Let Z be a random variable with cdf given by

(11) where . Then Z belongs to the class of distributions, and is a location parameter which corresponds to the median of Z.

Proof.

The results hold by setting in Equation (8) to get (11). Therefore, the qf of Z is given by

(12) and it follows that, by taking u = 0.5 in Equation (12), μ is the median of Z. This completes the proof.

The pdf of Z can be written in the median-based parameterization as

where .

3. General mathematical properties

In this section, we derive some useful statistical quantities for both introduced families, including the raw and incomplete moments. All the results of this section can be easily extended to the and median-based parametrization by substituting α for and , respectively.

3.1. Moments

Many of the important characteristics and features of a distribution are obtained through ordinary moments. The sth moment of Y, with from (4), is given by

| (13) |

where is the moment generating function of . Similar computations can be done for the family. Note that, the sth moment of Z can be written as Using the binomial theorem, and the result in (13), it can be reduced to

| (14) |

3.2. Incomplete moments

The sth incomplete moment of Y is defined as . Taking from (4), we have that

Setting , we have and then

| (15) |

Using the relationship between the introduced families, the sth incomplete moment of Z is given by Using the binomial theorem, and after some algebra, we can write

| (16) |

4. Maximum likelihood estimation

The conventional likelihood estimation techniques can be applied to estimate the parameters of the and families. Let be a random sample of size n from the family distributions. Thus, the log-likelihood function for the parameter vector can be written as

| (17) |

The components of the score function are given by

and

Setting and equal to zero and solving these equations simultaneously yields the maximum likelihood estimators (MLE), , of . These equations cannot be solved analytically. Statistical software can be used to solve them numerically using iterative methods such as the Newton-Raphson type algorithms.

However, for fixed , it is possible to obtain a semi-closed MLE of α. From , the estimator of α is given by

By replacing α for in Equation (17) yields the profile log-likelihood for the parameter vector . Maximizing the profile log-likelihood may be simpler since it involves one less parameter. The log-likelihood function for the parameter vector , of the median-based parameterization, is obtained just by making in Equation (17). The component of the score function remains unchanged, and is given by

For the special models, where , it is possible to obtain a closed-form MLE for μ. The results of the family can be derived through similar computations. It is easy to note that the log-likelihood of Z is obtained by taking y = 1−z and log(μ) = log(1−μ) in (17).

5. Some special models

In this section, we provide a few examples of unit distributions that arise as special models of the proposed families and are still not defined in the literature. Therefore, the Gompertz and Lomax models are considered as parent distributions in both introduced families. Those models are introduced under the median-parametrization given in Section 2. The unit Weibull (UW) distribution was pioneered by [15] using a transformation in a Weibull random variable. We also note that it arises by considering the Weibull distribution as a parent model in the family.

5.1. Unit Gompertz distribution

Consider the Gompertz distribution as a model in the family, we obtain the unit Gompertz (UGo) distribution, in which its cdf and pdf takes the form

and

| (18) |

respectively, where is a shape parameter and is the median parameter. For the pdf (18), it is easy to verify that

The shapes behavior of the UGo pdf is given by the following proposition.

Proposition 5.1

Let Y be a random variable following the UGo distribution. Then, its density is unimodal with mode at

The proof of Proposition 5.1 can be found in the paper supplementary material. From Equation (5), the UGo qf is obtained as

The UGo first raw moment reduces to

where is the upper incomplete gamma function.

5.2. Unit Lomax distribution

By considering the Lomax distribution as a model in the family, we derive the unit Lomax (UL) distribution, in which its cdf and pdf takes the form

and

| (19) |

respectively, where is a shape parameter and is the median parameter. For the pdf (19), it can be verified that

Proposition 5.2

Let Y be a random variable following the UL distribution. Then, for its density is bathtub shaped with minimum at

The proof of Proposition 5.2 can be found in the paper supplementary material. From Equation (5), the UL qf is obtained as

and its first raw moment as

5.3. Complementary unit Gompertz distribution

By considering the Gompertz distribution as a model in the family, we obtain the complementary unit Gompertz (CUGo) distribution, in which its cdf and pdf takes the form

and

| (20) |

respectively, where is a shape parameter and is the median parameter.

For the pdf (20), it is easy to verify that

The shapes behavior of the CUGo pdf is given by the following proposition.

Proposition 5.3

Let Z be a random variable following the CUGo distribution. Then its density is unimodal with mode at

The proof of Proposition 5.3 can be found in the paper supplementary material. From Equation (10), the CUGo qf is obtained as

and its first raw moment as

5.4. Complementary unit Lomax distribution

By considering the Lomax distribution as a model in the family, we derive the complementary unit Lomax (CUL) distribution, in which its cdf and pdf takes the form

and

| (21) |

respectively, where is a shape parameter and is the median parameter. For the pdf (21), it is easy to verify that

Proposition 5.4

Let Z be a random variable following the CUL distribution. Then, for its density is bathtub shaped with minimum at

The proof of Proposition 5.4 can be found in the paper supplementary material. From Equation (10), the CUL qf is obtained as

and its first raw moment as

6. The complementary unit Weibull distribution and its properties

The two-parameter Weibull distribution [31] is one of the most popular models for modeling non-negative random processes. It has applications ranging from reliability engineering, survival analysis in biomedical sciences, mortality study, insurance, and social sciences, among others. In this section, we describe of the mathematical properties for the complementary unit Weibull (CUW) distribution under the median-parametrization given in Section 2. The parameter estimation by maximum likelihood method is presented and a simulation study is carried out.

Thus, the median-based CUW cdf and pdf are

and

| (22) |

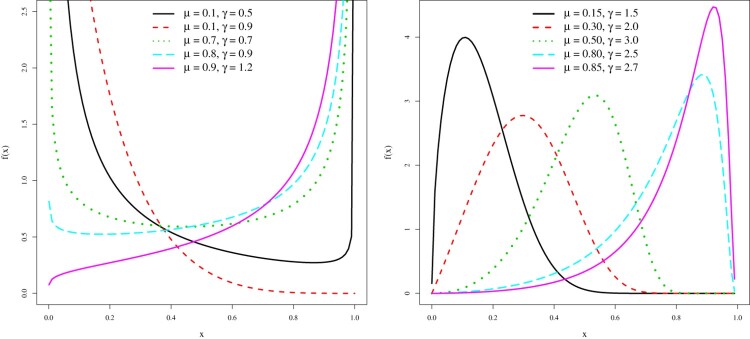

respectively, where . Figure 1 illustrates its pdf shapes for some parameter values. From Equation (5), the qf of CUW distribution is obtained as

| (23) |

Figure 1.

Pdf plots for the CUW pdf.

Based on previous results from Equation (14), the hth moment of the CUW model is given by

| (24) |

The hth cumulant ( ) of the CUW model can be obtained from (24) using well-known relationships. We have that

where . Note that is the variance of the CUW model. The skewness and kurtosis follow from the third and fourth standardized cumulants, respectively.

Table 1 provides a numerical study by computing the first four moments, variance, , and for ten different scenarios. Note that the parameterizations chosen are the same presented in Figure 1. All the quantities computed are in agreement with the behavior in those plots. Also, these illustrations indicate that the CUW distribution is quite flexible not only for density shapes but also regarding the moments, skewness, and kurtosis. It can accommodate positive and negative values for both skewness and kurtosis coefficients. Combining (15) and (16), and using the proposed median-parametrization, the sth incomplete moment of the CUW distribution is

Using the exponential expansion in , and after some algebra, it can be determined as

Table 1. First four moments, variance, skewness and kurtosis coefficients for some scenarios of the CUW distribution.

| μ | γ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.5 | 0.2245 | 0.1250 | 0.0889 | 0.0704 | 0.0746 | 1.3435 | 0.7287 |

| 0.10 | 0.9 | 0.1406 | 0.0374 | 0.0136 | 0.0060 | 0.0177 | 1.4362 | 2.1116 |

| 0.15 | 1.5 | 0.1644 | 0.0370 | 0.0101 | 0.0031 | 0.0100 | 0.6986 | 0.1574 |

| 0.30 | 2.0 | 0.3029 | 0.1089 | 0.0437 | 0.0190 | 0.0172 | 0.1441 | −0.5192 |

| 0.50 | 3.0 | 0.4871 | 0.2538 | 0.1389 | 0.0788 | 0.0166 | −0.4517 | −0.1373 |

| 0.70 | 0.7 | 0.6150 | 0.4992 | 0.4387 | 0.4000 | 0.1211 | −0.4071 | −1.3292 |

| 0.80 | 0.9 | 0.6897 | 0.5713 | 0.5040 | 0.4589 | 0.0956 | −0.7420 | −0.7841 |

| 0.80 | 2.5 | 0.7596 | 0.6026 | 0.4919 | 0.4098 | 0.0257 | −1.1871 | 1.2709 |

| 0.85 | 2.7 | 0.8095 | 0.6757 | 0.5757 | 0.4980 | 0.0204 | −1.4738 | 2.3962 |

| 0.90 | 1.2 | 0.7897 | 0.6859 | 0.6197 | 0.5722 | 0.0622 | −1.3059 | 0.7269 |

6.1. Maximum likelihood estimation

Let be a random sample of size n from the CUW distribution. Let be the parameter vector. The log-likelihood function for can be expressed as

| (25) |

The maximum likelihood estimates can be obtained by maximizing directly the Equation (25). Alternatively, we can obtain the score vector , set their components to zero and solve these equations simultaneously. For the CUW distribution, the components are given by

and

As reported in Section 4, we note that for fixed γ, the semi-closed MLE of μ is given by

| (26) |

By replacing μ by in Equation (25), we obtain the profile log-likelihood function for γ, expressed as

| (27) |

The score vector for (27), , is given by

6.2. Simulation study

We shall now present the results from Monte Carlo simulation studies conducted to evaluate the performance of the MLEs of the parameters that index the CUW distribution. The simulations are carried out in the R programming language, using the optim routine with BFGS quasi-Newton nonlinear optimization algorithm. The inverse transform method is employed to generate a size n sample from a CUW distribution using (23). We simulate 10,000 Monte Carlo replications, the sample sizes being . It is considered ten different combinations for the parameter vector . The scenarios are defined by the illustrations discussed in Figure 1 and Table 1. Thus, the chosen parametrizations cover different density shapes and also various combinations of skewness and kurtosis coefficients.

The mean estimates, percentage relative bias (RB%), and root mean squared errors (RMSE) are computed by maximizing (27) and taking the MLE of μ from (26). One advantage of using the profile log-likelihood is that the maximization of (27) is simpler than for (25), once it involves only one parameter.

The results for each generation scheme are reported in Table 2. As expected, the RMSEs tend to decrease as the sample size increases. We also observe that the overall performance of the MLEs is appropriate. Note that when n = 300, the RB% is less than 1% for both parameter estimates and all the scenarios. In general, the estimates are more accurate when compared with . It also presents smaller RMSEs, mostly when n = 20.

Table 2. Monte Carlo results for the mean estimates, RB%, and RMSEs of the CUW distribution with 10,000 replications.

| Mean | RB% | RMSE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | μ | γ | n | ||||||

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 20 | 0.1094 | 0.5381 | 9.3663 | 7.6129 | 0.0568 | 0.1094 |

| 50 | 0.1032 | 0.5145 | 3.1661 | 2.8967 | 0.0353 | 0.0606 | |||

| 100 | 0.1011 | 0.5067 | 1.0804 | 1.3404 | 0.0247 | 0.0408 | |||

| 300 | 0.1000 | 0.5023 | 0.0246 | 0.4585 | 0.0150 | 0.0229 | |||

| 2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 20 | 0.1014 | 0.9694 | 1.3847 | 7.7074 | 0.0303 | 0.1980 |

| 50 | 0.0999 | 0.9246 | −0.0722 | 2.7344 | 0.0199 | 0.1096 | |||

| 100 | 0.1000 | 0.9140 | −0.0176 | 1.5596 | 0.0143 | 0.0738 | |||

| 300 | 0.0993 | 0.9037 | −0.6941 | 0.4075 | 0.0105 | 0.0418 | |||

| 3 | 0.15 | 1.5 | 20 | 0.1500 | 1.6142 | 0.0273 | 7.6133 | 0.0271 | 0.3288 |

| 50 | 0.1494 | 1.5479 | −0.3772 | 3.1947 | 0.0190 | 0.1848 | |||

| 100 | 0.1489 | 1.5195 | −0.7447 | 1.3028 | 0.0157 | 0.1221 | |||

| 300 | 0.1495 | 1.5075 | −0.3650 | 0.4983 | 0.0100 | 0.0691 | |||

| 4 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 20 | 0.2982 | 2.1500 | −0.6097 | 7.5018 | 0.0390 | 0.4364 |

| 50 | 0.2983 | 2.0574 | −0.5622 | 2.8685 | 0.0264 | 0.2427 | |||

| 100 | 0.2988 | 2.0295 | −0.3891 | 1.4747 | 0.0201 | 0.1632 | |||

| 300 | 0.2983 | 2.0087 | −0.5669 | 0.4353 | 0.0188 | 0.0921 | |||

| 5 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 20 | 0.4981 | 3.2285 | −0.3823 | 7.6171 | 0.0349 | 0.6670 |

| 50 | 0.4979 | 3.0818 | −0.4291 | 2.7282 | 0.0281 | 0.3580 | |||

| 100 | 0.4975 | 3.0376 | −0.5095 | 1.2544 | 0.0242 | 0.2443 | |||

| 300 | 0.4989 | 3.0145 | −0.2177 | 0.4846 | 0.0151 | 0.1379 | |||

| 6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 20 | 0.6847 | 0.7588 | −2.1872 | 8.4058 | 0.1455 | 0.1571 |

| 50 | 0.6884 | 0.7214 | −1.6610 | 3.0541 | 0.1104 | 0.0847 | |||

| 100 | 0.6889 | 0.7114 | −1.5920 | 1.6234 | 0.0917 | 0.0579 | |||

| 300 | 0.6938 | 0.7056 | −0.8787 | 0.7933 | 0.0641 | 0.0321 | |||

| 7 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 20 | 0.7808 | 0.9725 | −2.4046 | 8.0553 | 0.1215 | 0.2028 |

| 50 | 0.7887 | 0.9273 | −1.4069 | 3.0367 | 0.0852 | 0.1085 | |||

| 100 | 0.7922 | 0.9119 | −0.9774 | 1.3259 | 0.0686 | 0.0738 | |||

| 300 | 0.7946 | 0.9043 | −0.6741 | 0.4759 | 0.0566 | 0.0410 | |||

| 8 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 20 | 0.7950 | 2.6931 | −0.6225 | 7.7256 | 0.0475 | 0.5538 |

| 50 | 0.7953 | 2.5720 | −0.5871 | 2.8793 | 0.0407 | 0.3062 | |||

| 100 | 0.7976 | 2.5369 | −0.3048 | 1.4757 | 0.0291 | 0.2035 | |||

| 300 | 0.7987 | 2.5123 | −0.1610 | 0.4934 | 0.0181 | 0.1154 | |||

| 9 | 0.85 | 2.7 | 20 | 0.8456 | 2.9057 | −0.5143 | 7.6168 | 0.0402 | 0.5885 |

| 50 | 0.8459 | 2.7742 | −0.4882 | 2.7496 | 0.0328 | 0.3268 | |||

| 100 | 0.8473 | 2.7411 | −0.3166 | 1.5238 | 0.0255 | 0.2206 | |||

| 300 | 0.8488 | 2.7101 | −0.1457 | 0.3753 | 0.0165 | 0.1239 | |||

| 10 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 20 | 0.8849 | 1.2906 | −1.6780 | 7.5480 | 0.0833 | 0.2609 |

| 50 | 0.8878 | 1.2325 | −1.3589 | 2.7100 | 0.0704 | 0.1464 | |||

| 100 | 0.8930 | 1.2164 | −0.7791 | 1.3626 | 0.0536 | 0.0993 | |||

| 300 | 0.8965 | 1.2053 | −0.3938 | 0.4416 | 0.0394 | 0.0550 | |||

In the paper supplementary material, we provide boxplots that illustrate the convergence of and for the first 100 replications at selected scenarios from Table 2. The outcome indicates that the precision of the MLEs improved for larger sample sizes. In addition, both and exhibited high accuracy and precision when n = 300. We note the presence of outliers that overestimate the true value of γ for the small sample size n = 20. By this fact, we observe that this configuration is attenuated as n increases.

7. Applications

In what follows, we shall apply some and special models for two data sets related to literacy rate, which is defined as the proportion of people aged 15 years old or more who can read or write a simple note. The first data set contains the literacy rates of 5565 cities in Brazil. It was measured during the census in 2010 and is available at http://datasus.saude.gov.br/. The second application models the literacy rates of 1107 cities in Colombia. It was measured during the census in 2005 and is available at www.http://microdatos.dane.gov.co/. The analysis is carried out using the AdequacyModel script [10] in the R programming language.

For modeling those data, we fit the classical beta and Kw distributions and other five special models of both introduced families. They are the UGo, ULo, CUGo, CULo and CUW distributions. They have their densities given by (18), (19), (20), (21) and (22), respectively. We also considered the unit gamma (UG) distribution, introduced by [7] and considered by [27] for hydrological applications. Mazucheli et al. [13] proposed two bias-corrected maximum likelihood estimators (MLEs) for both shape parameters of the UG distribution.

The UG, beta and Kw densities (for 0<y<1) are given by

and

| (28) |

respectively. For the UG and beta models, is the mean of Y, and φ is a precision parameter. Those parametrizations are presented by [4,19], respectively. For the Kw model, is the distribution median, and φ is a precision parameter. The pdf in (28) was previously presented by [18].

The descriptive summary of the literacy rates for Brazilian and Colombian municipalities is given in Table 3. We observe that both countries present the mean and median quite distant from the mode, and variance of 0.01. Brazil exhibit higher values for all central tendency measures considered and Colombia for the amplitude. Both countries present negative skewness for this variable. These descriptive measures indicate that the mass of observations is concentrated on the right. This configuration is adequate once this variable is defined positively: the higher the literacy rate, the better the country's education development. According to UNESCO [29], ‘literate societies enable the free exchange of text based information and provide an array of opportunities for lifelong learning’. In addition, for Sen [26], the basic education can be considered a semi-public good, which benefits not only the literate person but also the society in general. We develop an interactive map dashboard as a tool for data visualization on the literacy rate. Interested readers can refer to the website https://newdists.shinyapps.io/UEWfamilies/#section-literacy-rates.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for literacy rates in both countries.

| Country | Mean | Median | Mode | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 0.8419 | 0.8708 | 0.93 | 0.01 | −0.61 | −0.72 | 0.53 | 0.99 |

| Colombia | 0.8039 | 0.8341 | 0.88 | 0.01 | −1.57 | 3.67 | 0.18 | 0.98 |

The parameter estimates obtained by the maximum likelihood method, and corresponding standard errors (SEs) for all those models are listed in Table 4 for the Brazilian and Colombian data sets. The Cramér-von Misses corrected statistic [3] is also presented to evaluate the goodness-of-fit. The lower is the statistic's value, the better is the adjustment to the data. The SEs of the estimates for all fitted models are quite small. Among all fitted models, the figures in Table 4 indicate that, for both data sets, the CUW model has the lowest value for . Further, the other distributions on the proposed families are shown competitive with the classical models. It illustrates the relevance of the new family for modeling social indicators, such as the literacy rate.

Table 4. MLEs of the parameters from fitted models to literacy rates for Brazilian municipalities in 2010, and Colombian municipalities in 2005.

| Brazil | Colombia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Parameter estimates | Parameter estimates | ||||

| Beta | 0.8420 | 13.3490 | 7.3663 | 0.8020 | 14.0180 | 1.8003 |

| (0.0013) | (0.2520) | (0.0031) | (0.5864) | |||

| Kw | 0.8610 | 8.9550 | 6.8732 | 0.8190 | 8.7040 | 1.1929 |

| (0.0012) | (0.1308) | (0.0029) | (0.2712) | |||

| UG | 0.8420 | 2.1080 | 7.3735 | 0.8020 | 2.7690 | 1.8138 |

| (0.0013) | (0.0372) | (0.0031) | (0.1113) | |||

| UGo | 0.8510 | 3.7220 | 13.9384 | 0.8340 | 1.2030 | 3.6124 |

| (0.0017) | (0.1096) | (0.0046) | (0.1184) | |||

| ULo | 0.8920 | 0.6940 | 6.4610 | 0.8600 | 1.3700 | 1.2318 |

| (0.0015) | (0.0291) | (0.0042) | (0.1444) | |||

| CUGo | 0.8780 | 1.2270 | 10.6856 | 0.8360 | 1.6040 | 1.4484 |

| (0.0015) | (0.0149) | (0.0034) | (0.0397) | |||

| CULo | 0.7600 | 365.6600 | 6.1925 | 0.7080 | 183.819 | 1.4064 |

| (0.0046) | (69.7698) | (0.0109) | (59.528) | |||

| CUW | 0.8720 | 3.2070 | 5.0898 | 0.8300 | 3.5548 | 0.2798 |

| (0.0013) | (0.0329) | (0.0030) | (0.0808) | |||

Note: The corresponding SEs (given in parentheses) and the goodness-of-fit statistic.

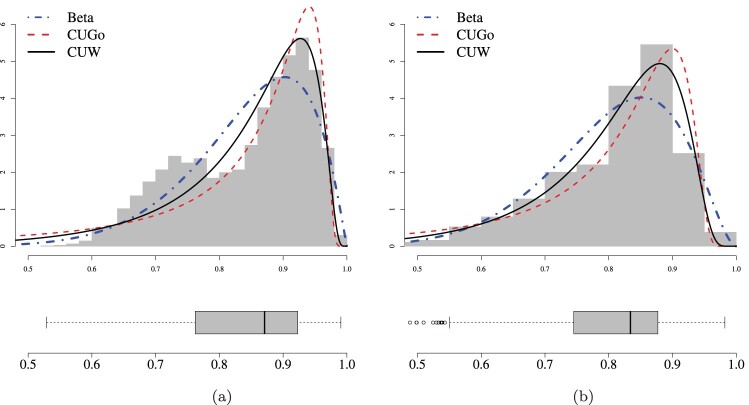

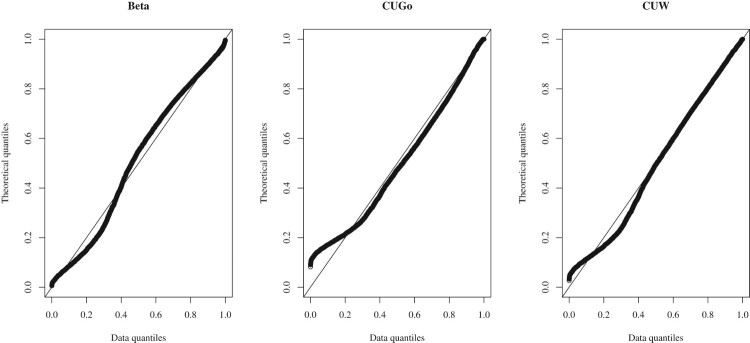

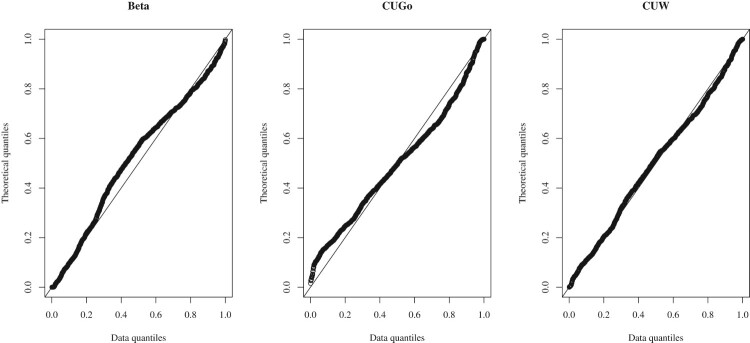

Figure 2 contains the data histogram with fitted density functions for some of the competitive models introduced and the beta distribution. This visual inspection indicates that the CUW distribution fits adequately to the Brazilian and Colombian literacy rates. We also note that this plot is in agreement with the results in Table 3. For both samples, the CUW median MLE is very close with the observed, and the CUGo provides the second closer median estimate. By analyzing the quantile-quantile plot, we also observe the CUW distribution's superiority for modeling these data sets. Therefore, we can conclude that the CUW distribution, a particular case of the family, provides a good fit to the Brazilian and Colombian literacy rates, and other distributions on the introduced families are also quite competitive. Finally, these results illustrate that the new models can be effective alternatives to the classical distributions for modeling bounded data (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Boxplot, histogram and estimated densities of the beta, CUGo and CUW models for the literacy rates. (a) Brazilian data and (b) Colombian data.

Figure 3.

Quantile-quantile plot of the beta, CUGo and CUW models for the literacy rates for Brazilian municipalities in 2010.

Figure 4.

Quantile-quantile plot of the beta, CUGo and CUW models for the literacy rates for Colombian municipalities in 2005.

8. Concluding remarks

We define two new classes of distributions with bounded domain constructed by a simple and intuitive variable transformation in the extended Weibull family of distributions. The main properties of the families of distributions are derived, such as the quantile function, moments, and incomplete moments. Five special models in the family are described with some details. The maximum likelihood procedure is used for estimating the model parameters. In order to assess the performance of the maximum likelihood estimates, a simulation study is performed employing Monte Carlo experiments. An example of real data illustrates the importance and potentiality of the new family. In conclusion, we define a general approach for generating new unit interval distributions, at least forty distributions, some known, and the great majority new ones. All computational codes are available as supplementary material. We hope these families of distributions may attract wider applications in statistics. Future work should explore a regression structure for the median and zero-augmented family, assuming that the variable has a mixed continuous-discrete distribution to model data that are observed on or .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge partial financial support from CAPES.

Note

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Ahnen R.E., The politics of police violence in democratic Brazil, Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 49 (2007), pp. 141–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2007.tb00377.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altun E. and Cordeiro G.M., The unit-improved second-degree Lindley distribution: Inference and regression modeling, Comput. Stat. 35 (2019), pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G. and Balakrishnan N., A general purpose approximate goodness-of-fit test, J. Qual. Technol. 27 (1995), pp. 154–161. doi: 10.1080/00224065.1995.11979578 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari S.L.P. and Cribari-Neto F., Beta regression for modelling rates and proportions, J. Appl. Stat. 31 (2004), pp. 799–815. doi: 10.1080/0266476042000214501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghitany M.E., Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., and Alqallaf F., The unit-inverse gaussian distribution: A new alternative to two-parameter distributions on the unit interval, Comm. Statist. Theory Methods 48 (2019), pp. 3423–3438. doi: 10.1080/03610926.2018.1476717 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gómez-Déniz E., Sordo M.A., and Calderín-Ojeda E., The log-Lindley distribution as an alternative to the beta regression model with applications in insurance, Insurance Math. Econom. 54 (2014), pp. 49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.insmatheco.2013.10.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassia A., On a family of distributions with argument between 0 and 1 obtained by transformation of the gamma distribution and derived compound distributions, Aust. J. Statist. 19 (1977), pp. 108–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1977.tb01277.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurvich M., DiBenedetto A., and Ranade S., A new statistical distribution for characterizing the random strength of brittle materials, J. Mater. Sci. 32 (1997), pp. 2559–2564. doi: 10.1023/A:1018594215963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marinho P.R.D., Bourguignon M., and Dias C.R.B., AdequacyModel: Adequacy of probabilistic models and general purpose optimization, R package version 2.0.0, 2016. Available at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=AdequacyModel.

- 11.Massa K.H.C., Pabayo R., and Chiavegatto Filho A.D.P., Income inequality and self-reported health in a representative sample of 27 017 residents of state capitals of Brazil, J. Public Health 40 (2018), pp. e440–e446. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., and Chakraborty S., On the one parameter unit-Lindley distribution and its associated regression model for proportion data, J. Appl. Stat. 46 (2019), pp. 700–714. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2018.1511774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., and Dey S., Improved maximum likelihood estimators for the parameters of the unit-gamma distribution, Comm. Statist. Theory Methods 47 (2017), pp. 3767–3778. doi: 10.1080/03610926.2017.1361993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., and Dey S., The unit-Birnbaum-Saunders distribution with applications, Chil. J. Stat. 9 (2018), pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., Fernandes L.B., de Oliveira R.P., and Ghitany M.E., The unit-Weibull distribution and associated inference, J. Appl. Probab. Stat. 13 (2019), pp. 1–22. doi: 10.18576/amis/13S101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazucheli J., Menezes A.F.B., Fernandes L.B., de Oliveira R.P., and Ghitany M.E., The unit-Weibull distribution as an alternative to the Kumaraswamy distribution for the modeling of quantiles conditional on covariates, J. Appl. Stat. 47 (2019), pp. 954–974. doi: 10.1080/02664763.2019.1657813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messias E., Income inequality, illiteracy rate, and life expectancy in Brazil, Amer. J. Public Health 93 (2003), pp. 1294–1296. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitnik P.A. and Baek S., The Kumaraswamy distribution: Median-dispersion re-parameterizations for regression modeling and simulation-based estimation, Statist. Papers 54 (2013), pp. 177–192. doi: 10.1007/s00362-011-0417-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mousa A.M., El-Sheikh A.A., and Abdel-Fattah M.A., A gamma regression for bounded continuous variables, Adv. Appl. Stat. 49 (2016), pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadarajah S. and Kotz S., On some recent modifications of Weibull distribution, IEEE Trans. Reliab. 54 (2005), pp. 561–562. doi: 10.1109/TR.2005.858811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham H. and Lai C.D., On recent generalizations of the Weibull distribution, IEEE Trans. Reliab. 56 (2007), pp. 454–458. doi: 10.1109/TR.2007.903352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royuela V. and García G.A., Economic and social convergence in Colombia, Reg. Stud. 49 (2015), pp. 219–239. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.762086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos-Neto M., Bourguignon M., Zea L.M., Nascimento A.D., and Cordeiro G.M., The Marshall-Olkin extended Weibull family of distributions, J. Stat. Distrib. Appl. 1 (2014), pp. 9. doi: 10.1186/2195-5832-1-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sen A., The standard of living: Lecture I, concepts and critiques, The Standard of Living, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987, pp. 1–19.

- 26.Sen A., Develoment as Freedom, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tadikamalla P.R., On a family of distributions obtained by the transformation of the gamma distribution, J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 13 (1981), pp. 209–214. doi: 10.1080/00949658108810497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.G. Assembly , Work of the statistical commission pertaining to the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/71/313), UN General Assembly, New York, NY, USA 2017.

- 29.UNESCO , Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006: Education for All. Literacy for life, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- 30.UNESCO , Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2015, UNESCO, Paris, 2015.

- 31.Weibull W., A statistical distribution of wide applicability, J. Appl. Mech. 18 (1951), pp. 293–297. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.