Abstract

The report describes the establishment and characterization of a mouse xenograft transplantation model for the study of papillomavirus infection of bovine skin. Calf scrotal skin was inoculated with bovine papillomavirus type 2 before grafting it to the dorsum of severe combined immunodeficient mice. The grafted skin contained epidermis, dermis, and a thin layer of fat. After 5 months the induced warts not only showed histological features of papillomavirus infections but also tested positive for viral DNA and papillomavirus capsid antigen. The formation of infectious virions was demonstrated by inoculation of new transplants with crude extract from the induced warts as well as in a cell culture focus assay. Topical application of bromovinyl-2′-deoxyuridine led to a reduction in viral DNA content in the developing wart. This small-animal xenograft model should be useful for characterizing antiviral compounds and providing an understanding of the regulation of papillomavirus infections.

Papillomaviruses (PVs) are a family of small DNA viruses that cause intraepithelial lesions in most mammals. Interest in the study of human PVs (HPVs) was stimulated by the observation that particular types of HPV are associated with malignant disease, in particular, carcinoma of the cervix (13).

The development of specific chemotherapy for HPV infections has been impeded by the lack of a model of viral pathogenesis. This is because the virus is highly species specific and its replication cycle is regulated by the differentiation pathway of keratinocytes. Currently available, cell-based models of viral replication are therefore complex, and conventional cell culture systems are not available for the identification of compounds with activity against papillomaviruses. However, transgenic cell lines which contain targets for potential inhibitors of papillomavirus-encoded gene products can now be constructed for screening purposes (for a review see reference 24).

The therapeutic evaluation of antiviral compounds requires an animal model of the viral replication cycle so that the pharmacologies and efficacies of such substances can be examined. The classical animal models of PV infections involve cattle, cottontail or domestic rabbits and dogs and their respective PVs. They have been used to determine some key events in PV infections (2, 6, 19, 26) and to evaluate the efficacy of potential therapeutics like ribavirin (23). However, these models have their limitations due to costs, housing space, and, in the case of cottontail rabbits, restrictions imposed by animal conservation regulations.

Thus, there is a need for a validated, small-animal model in which the complete viral life cycle can be monitored. Ideally, infectious virus that can be readily titrated should be produced, the development of the lesion should be simple to monitor, the viral inoculum should be readily available, the host tissue should be obtainable in sufficient quantities, and the transplantation model itself should be reproducible. None of the previously reported models fulfill all of these criteria, especially in the case of human virus-graft models.

The fact that it is possible to titrate the infectivity of bovine PV (BPV) in vitro with mouse cells (12) suggests that this virus might be an ideal basis for a xenograft model. In addition, the virus is available in large quantities from the warts of infected cattle, and there is an almost limitless supply of the host tissue, bovine skin.

This report describes a study on the optimization of a transplantation model based on the severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse that fulfills all the criteria listed above. Preliminary studies revealed that scrotal skin from freshly slaughtered calves was the ideal donor tissue because of its flexibility and small amounts of associated fatty tissue. Following in vitro infection with BPV and transplantation of the infected tissue to the back of the immune-deficient mouse, the development of warts induced in the skin could be easily monitored. A productive infection in the graft was demonstrated by passage of the virus from graft to graft and infection and transformation of susceptible mouse cells in vitro. A preliminary study was also carried out on the effects of an antiviral compound, bromovinyl-2′-deoxyuridine (BVDU), on the development of established warts. This animal model is advantageous with regard to the availability of skin as well as of BPV and also provides an ideal system for testing the efficacies of antiviral compounds following oral administration, parenteral administration, or topical application.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Six-week-old male NOD-scid/scid mice were obtained from M&B A/S (Ry, Denmark) and housed under sterile conditions. Water and feed were provided ad libitum.

Virus purification and identification.

Papillomas were removed from an infected Galloway calf and stored at −80°C until required. Pieces of papillomas were homogenized in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; gentamicin, 50 μg/ml) with an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (Janke & Kunkel, Staufen, Germany). The homogenate was submitted to a low-speed centrifugation, and the supernatant was pelleted at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C and resuspended in PBS. The viral titer was estimated by electron microscopy to be 5.5 × 1011 viral particles per ml. The viral type present in the papilloma was determined by digestion of the viral DNA with the restriction enzymes BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, HpaI, PvuI, ScaI, and SalI (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and Southern blotting with a probe derived from complete BPV type 2 (BPV-2) DNA.

Preparation and inoculation of skin transplants and transplantation.

Fresh scrotal skin was obtained from 8- to 12-week-old calves directly after slaughtering. The skin was washed with tap water and PBS. After disinfection with 70% ethanol and renewed washing with PBS, the skin was shaved and the fat was removed surgically. Full-thickness skin was cut into squares measuring approximately 15 by 15 mm and stored in PBS until grafting. Prior to transplantation some grafts were infected with BPV by injecting 5 × 107 virus particles at three distinct places on the transplant. Six-week-old male NOD-scid/scid mice were anesthetized with 2.5% tribromoethanol (avertin; 10 g of tribromoethyl alcohol [Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany] in 10 ml of tertiary amyl alcohol [Merck, Darmstadt, Germany]) by intraperitoneal injection. By aseptic techniques, the mouse skin was excised and the fascia and the muscle were superficially wounded. The bovine skin was then placed on the site and held in place with a suture (5/0 Miralene; Braun, Melsungen, Germany).

Histology and in situ hybridization.

Papilloma samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h at room temperature, embedded in paraffin wax, and cut into 5-μm sections. After removal of the paraffin with xylene and rehydration by brief submersion in a series of aqueous alcohol solutions of decreasing alcohol content, the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain and examined by light microscopy.

Immune histological investigations were carried out by first blocking sections overnight at 4°C with 5% powdered milk in PBS. After being washed in PBS, the sections were incubated for 30 min with anti-BPV-1 mouse polyclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.) diluted 1:100 in PBS. Following further washes in PBS, the samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (whole molecule; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:100 in 5% powdered milk in PBS. Antibody binding was detected with the Vectastain ABC kit (Novocastra, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, United Kingdom), and the slides were examined by light microscopy.

In situ hybridization of DNA was performed with 5-μm sections with biotinylated BPV-2 L1-region DNA probes (511 bp), generated by PCR with the primer pair 5′-AATCAGTTTGACTTGCCTGATAGGACTG-3′ and 5′-CTTGCAAAGAAGAACATACTGTTTCCA-3′ and the In Situ Hybridisation and Detection kit (Gibco Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Southern blotting and hybridization.

Total cellular DNA from transplants was isolated by proteinase K digestion followed by phenol-chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitation. One microgram of undigested DNA and DNA digested with BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, HpaI, PvuI, and SacI was separated in 0.8% agarose gels and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), and specific DNA fragments were detected with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled BPV-2 DNA. The probe was generated by using the DIG-High Prime kit (Roche Diagnostics). Hybridization and chemiluminescence detection were carried out as described previously (The DIG System User's Guide for Filter Hybridisation; Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The blots were evaluated as required with a LumiImager (Roche Diagnostics) and associated software.

Cell focus assay.

C127 cells (catalog no. CRL 1616; American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in growth medium consisting of Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal calf serum at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% (vol/vol) CO2 and 95% humidified air. On the day before infection, 2 × 105 cells were seeded into 25-cm2 flasks (30). Forty microliters of either the virus suspension isolated from the transplants or the virus isolated from the original bovine wart was added to the cells, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were washed twice with PBS, fed growth medium, and replated after 16 h postinfection into 175-cm2 flasks in growth medium with 5% fetal calf serum. The medium was changed every 3 to 4 days, and the cells were stained with Giemsa stain after 2 weeks.

Test substance.

BVDU (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as a 2.5% solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) immediately before application.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was carried out by using the information on the VassarStats website for statistical computation (http://faculty.vassar.edu/∼lowry/VassarStats.html).

RESULTS

Isolation and typing of BPV.

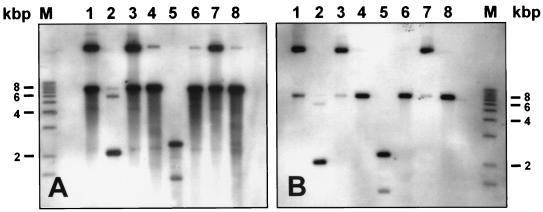

BPV was isolated from fragments of papilloma obtained from a Galloway calf, and the presence of viral particles was verified by electron microscopy. Viral DNA was extracted from viral particles, and the BPV type was identified by restriction analysis with the following enzymes: BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, HpaI, PvuI, SacI, and SalI. Hybridization of the restricted DNA with a complete BPV-2 probe clearly indicated that the BPV type isolated from the wart is BPV-2 (Fig. 1A). The smear seen below the DNA bands is most likely due to DNA degradation because the bovine wart used was already in a regressing state. The BPV type was also confirmed by sequencing the L1 region and the long control region with specific primers (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Southern blot analysis of digested BPV DNA isolated from the original wart (A) and the infected transplant (B). Lanes M, 1-kb marker; lanes 1, undigested viral DNA; lanes 2 to 8, viral DNA digested with the following restriction enzymes: BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, HpaI, PvuI, SalI, and ScaI, respectively.

Transplantation.

The donor tissue, calf scrotal skin, was treated as described in the Materials and Methods section, infected with 5 × 107 viral particles in vitro, transplanted to the shaved dorsums of 6-week-old male SCID mice, and held in place with a suture. Additional SCID mice were grafted with uninfected skin. In general, the grafts were transplanted onto the mice within 4 h of slaughter of the calves.

In the first few weeks following engraftment, the infected calf scrotal skin underwent necrosis and became darkened and encrusted. In comparison to uninfected tissue, evidence of infection from infected tissue was apparent through tissue proliferation at the margins of the transplants, which was observable 4 to 6 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 2A and B). In the following months the induced tumor increased steadily in size. In contrast, the uninfected graft became smaller and was eventually overgrown by mouse tissue (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

Tumor development of infected transplants after 6 weeks (A) and 20 weeks (B) and noninfected transplant 2 weeks (C) and 10 weeks (D) after transplantation.

At 5 months after transplantation the mice were killed and the tumor was harvested for histological analysis and virus extraction. One-half of the papilloma was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use, and the rest was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Histology of infected xenografts.

Thin sections of the fixed tissue were stained with H & E stain as described above and examined for histological features of PV infection. A PV infection is characterized by typical features such as papillomatosis, koilocytosis, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and parakeratosis (17). These signs of papillomavirus infection were restricted to certain parts of the transplant, especially their margins. The frequencies of koilocytes, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis in the nine transplants (induced warts) were nine, nine, seven, seven, and six transplants, respectively. In contrast to the initial transplant (Fig. 3A), the dermis of the infected skin thickened during the transplantation period. One graft was remarkable for its extreme hyperkeratosis, which could be observed even without the use of a microscope. This graft contained well-developed koilocytes with an increased ratio of nuclei to cytoplasm, as well as the characteristic vacuole around the nuclei (Fig. 3B). A large number of nucleated keratinocytes were present in the stratum corneum of the thickened epidermis. Papillomatosis with papillary projections of the epidermis forming a microscopically undulating layer was observed in six of nine transplants.

FIG. 3.

Calf scrotal skin (A) and the induced tumor 20 weeks after infection (B) stained with H&E stain. The star indicates the cornified cell layer, and the closed arrow indicates the basal cell layer. Note the thickened epidermis and the koilocytes in panel B. Magnification, ×32.

The nuclei of the tumors were positive for BPV by in situ hybridization only in those parts of the transplant showing all signs of a PV infection (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Demonstration of BPV-2 in a 20-week-old graft. (A) In situ hybridization with a 511-bp L1-region probe. Magnification, ×128. (B) Immunohistochemistry after treatment with an antibody raised against BPV-1 capsid proteins. One positive nucleus is marked by an arrow. Magnification, ×128.

Viral DNA was extracted from the frozen tumors, and the BPV type was determined by restriction analysis. No difference in the restriction pattern could be detected between the isolated viral DNA and the DNA from the original virus injected 5 months earlier (Fig. 1B). Immunohistochemistry was also performed with antibody raised against L1 and L2 capsid proteins. In contrast to BPV-2 DNA, which could be detected by in situ hybridization throughout the whole epidermis and dermis, the dark-brown positive signals for the capsid antigens were seen only in the nuclei of koilocytes in the stratum granulosum and in the stratum corneum (Fig. 4B).

Demonstration of presence and infectivity of graft-associated virus particles.

Three grafts that were positive for BPV capsid antigens in the immunohistochemistry analysis were processed by the method used to prepare the original inoculum by low- and high-speed centrifugation.

To demonstrate the presence and infectivity of the viral particles produced in the graft, the highly effective focus assay was used as described previously (30). Forty microliters of the virus preparation was added to the medium of C127 cells and the mixture was incubated at 37°C. C127 cells were also infected with the original inoculum as a positive control. Two weeks after infection the cell sheets were stained with Giemsa and examined for focus formation. Both inocula induced foci at similar rates, and as can be seen in Fig. 5, foci that were typical for BPV-2 infection formed (12).

FIG. 5.

Production of foci by C127 cells infected with a crude cell extract from an infected graft (A) and by C127 cells infected with virus isolated from a bovine wart (B). (C) Noninfected C127 cells. The cells were fixed in 100% methanol and stained with Giemsa stain.

The isolated graft-associated virus was also used as an inoculum to infect calf skin transplants. Calf scrotal skin injected with 45 μl of the graft tissue suspension was transplanted onto the dorsums of five male NOD-SCID mice. Three months after infection the mice were killed and the grafts were removed.

Examination of thin sections of these grafts (Fig. 6A) again revealed characteristics typical for BPV infection with a thickened epithelium containing several koilocytes, while the macroscopic appearance was similar to those of the warts that developed in the first xenograft passage (Fig. 6B). Southern blot hybridization clearly showed the presence of BPV-2 DNA in the grafts (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Tumor development in grafts infected with an extract of the primary xenograft tissue resuspended in PBS. (A) H&E-stained section of the tumor, in which the closed arrow indicates the basal cell layer and the star indicates the cornified layer. Magnification, ×32. (B) Macroscopic appearance of the tumor 12 weeks after infection.

Treatment with BVDU.

In order to address the utility of this model in an antiviral screening program, a group of four grafts was treated with BVDU by spreading 20 μl of a 2.5% solution in DMSO onto the developing wart every day for a period of 4 weeks prior to killing of the mice. A similar group was treated with DMSO alone. The grafts were harvested 1 day after the end of treatment and processed for Southern blotting and hybridization. As can be seen from Fig. 7A, the application of BVDU to established warts resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the amount of PV DNA in the tissue by approximately 70% compared to the amount of PV DNA in the tissue of the controls. The weights of the warts at the time of death were similar for both groups (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Treatment of established warts daily for 4 weeks with BVDU (2.5%, topically) or with solvent (DMSO). (A) BPV-2 DNA content of warts at the end of the treatment period. The difference between the means is significant (P = 0.01 by the Student t test). (B) Weight of warts at the end of the treatment period. The difference between the means is not significant (P = 0.17 by the Student t test).

DISCUSSION

This report describes the development of a new mouse xenograft model that can be used for in vivo studies of PV infections.

Natural infection with BPV is very common, and in healthy cattle, papillomas regress after several months (4). The BPV-infected cow is one of the classical animal models of PV infection and has been of use in revealing some features of the PV's life cycle, particularly its latency and carcinogenesis (6–8, 16, 28).

However, for reasons of costs and housing, a small-animal model is more convenient for pharmacological studies. For BPV, two athymic mouse models that use either BPV-4 (14, 15) or BPV-1 (11) as the infectious agent have been described previously. Both models use the renal capsule as the transplantation site and bovine fetal skin as the graft.

The dorsal skin of the mouse was chosen as the transplantation site in the model described here because tumor development can be readily observed and antiviral compounds can be evaluated by topical treatment as well as by other routes of administration.

Besides the transplantation site, the graft itself is of great importance for a successful outcome of the transplantation. In the case of human tissue one of the major problems associated with xenograft models is the availability and variability in the quality of the transplanted skin. The model reported here has the advantage that the target skin is available in almost unlimited quantities and can be obtained fresh from the abattoir. This greatly improves the reproducibility of the model, which is a prerequisite for pharmacological studies with small animals. A further advantage is the availability of often kilogram amounts of bovine warts as a source of infectious virus.

The BPV type isolated from the bovine wart used as a source of virus was identified by Southern blotting, restriction analysis, and sequencing as BPV-2, a subgroup B PV (5). BPVs of subgroup B have a genome size of ca. 8,000 bp and infect both the epidermis and the dermis; viral replication and virion antigens, however, are found only in the squamous epithelium (18).

The bovine skin pieces were infected by injecting a viral preparation immediately prior to transplantation. An infection of the graft after transplantation is more difficult because the calf scrotal skin becomes encrusted and hard (personal observation). All infected transplants grew steadily during the observation period, whereas noninfected transplants disappeared after 2 to 3 months. Earlier studies also showed that noninfected transplants did not survive as long as infected transplants (20, 21). PVs are able to uncouple cellular proliferation and differentiation of the normally growth-arrested, differentiated keratinocytes, so that the proliferation is enhanced while the differentiation is reduced (29). Therefore, increased levels of proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts in the infected transplants are probably the primary reason for the survival of the graft.

After 5 months the developed tumor showed typical signs of a PV infection in sections stained with H&E stain. Not all transplants revealed all five characteristic features of a PV infection (papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, and koilocytosis) (17); however, all infected warts exhibited at least three characteristics associated with productive PV infections and therefore qualified as papillomas as defined elsewhere (3). In addition, all transplants showed an enormously increased dermal part that is typical for fibropapillomas induced by subgroup B BPV types (9). It is interesting that a variability in histopathology has also been reported by Bonnez et al. (3) for warts obtained from SCID mice after implantation of condyloma fragments under the renal capsule and subsequent passage of the virus produced by those fragments, HPV-16.

Southern blot analysis of the viral DNA isolated from the transplant revealed DNA of the same size and with the same restriction pattern as the DNA in the original inoculum. In situ hybridization with a 500-bp L1-region fragment of BPV-2 DNA resulted in a strong nuclear staining that was restricted to areas with typical PV-induced histopathology. These areas may represent the progeny from a single cell or a small number of infected basal epithelial cells. Capsid proteins could be shown with an antibody raised against the L1 and L2 regions of BPV-1 which also cross-reacts with BPV-2 (5). The capsid proteins were located in the upper spinous layers as well as in the granular layers, as described for naturally occurring warts (10).

A virus suspension was prepared from the harvested transplants and used as an inoculum for a focus-forming assay with C127 mouse cells as well for a second series of bovine scrotal skin transplants. C127 cells incubated with the transplant suspension showed foci that were typical of those for a BPV-2 infection after 2 weeks. This demonstrates the presence of infectious viral particles in the transplants.

In the secondary transplantation experiment, the infected primary transplant was used as the inoculum and the mice were killed 3 months after transplantation. Tumors were clearly induced, and staining with H&E stain revealed several morphological characteristics of PV infection, although they were less obvious than those in the first infection. Southern blot analysis also demonstrated the presence of BPV-2 DNA in the warts. These results demonstrate that infectious viral particles had been formed in the primary graft and were present in the passaged material.

The observations of the effect of BVDU are reminiscent of the effect of (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonoylmethoxypropyl)cytosine (HPMPC), which is an inhibitor of herpesvirus polymerase, on HPV-induced proliferation of epithelial cells (27). Although its mechanism of action against HPV has not yet been clarified, HPMPC appears to inhibit the proliferation of HPV-harboring cells to a greater extent than it inhibits noninfected cells (1). BVDU is also an effective inhibitor of herpesvirus polymerase activity (25), although it is not clear why it should have an effect on the amount of BPV-2 DNA in the warts since the PVs do not encode a polymerase. It is possible, however, that we are observing a general effect on virus-induced host processes that support BPV-2 replication. BVDU has been reported to inhibit the proliferation of different mammalian cell lines at concentrations between 30 and 60 μg/ml (25), which is considerably less than the concentrations that were applied to the wart every day for a period of 4 weeks.

Despite 4 weeks of treatment with potentially cytostatic concentrations of BVDU, there were no significant differences in the sizes of the treated and untreated warts. This was probably due to the experimental design, which attempted to reflect the situation in a practitioner's office, in which all warts would be well established before treatment is started. It remains to be seen whether a specific antiviral compound will be effective at reducing the sizes of warts during a short treatment period like the one used in this study.

In summary, a simple mouse xenograft model of PV infection has been devised which uses bovine skin infected with BPV-2. DNA replication, protein expression, and the production of infectious virus particles indicate that the life cycle of the virus was complete in this model. The production of infectious virus was confirmed by focus assays and the successful passage of infectivity between transplants. Although this model cannot be used directly to study the influence of the immune system on the development of the wart, it can serve as a small-animal model to reveal not only details of the viral life cycle but also to model human papillomavirus infection. This is because several features are common to the two virus groups: plurality of the virus types, tissue specificity of lesions, and malignant progression of some papillomas (5). Furthermore, the viral replication and transcription functions in the human and animal PVs are structurally and functionally conserved, suggesting that inhibitors of these functions are likely to be active in both animal and human systems (22).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ilona Hulsmann, Elfi Carrozzo, Holger Dethlefsen, and Uwe Reimann for excellent assistance; and we are also indebted to Schlachthof Laame, Wuppertal, Germany, for providing calf scrotal skin. We also thank Christine Rühl-Fehlert for preparing the micrographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrei G, Snoeck R, Piette J, Delvenne P, de Clercq E. Antiproliferative effects of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates on human papillomavirus (HPV)-harboring cell lines compared with HPV-negative cell lines. Papillomavirus Rep. 1998;10:523–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J A, Sundberg J P, Ghim S J, Newsome J, Jenson A B, Schlegel R. A formalin-inactivated vaccine protects against mucosal papillomavirus infection: a canine model. Pathobiology. 1994;62:194–198. doi: 10.1159/000163910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonnez W, Rin C D, Borkhuis C, de Mesy Jensen K L, Reichman R C, Rose R C. Isolation and propagation of human papillomavirus type 16 in human xenografts implanted in the severe combined immunodeficiency mouse. J Virol. 1998;72:5256–5261. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5256-5261.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campo M S. Papillomas and cancer in cattle. Cancer Surv. 1987;6:39–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo M S. Papillomavirus infection in cattle: viral and chemical cofactors in naturally occurring and experimentally induced tumours. Ciba Found Symp. 1986;120:117–135. doi: 10.1002/9780470513309.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campo M S, O'Neil B W, Barron R J, Jarrett W F. Experimental reproduction of the papilloma-carcinoma complex of the alimentary canal in cattle. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1597–1601. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.8.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campo M S, O'Neil B W, Grindlay G J, Curtis F, Knowles G, Chandrachud L. A peptide encoding a B-cell epitope from the N-terminus of the capsid protein L2 of bovine papillomavirus-4 prevents disease. Virology. 1997;234:261–266. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandrachud L M, Grindly G J, McGravie G M, O'Neil B W, Wagner E R, Jarrett W F, Campo M S. Vaccination of cattle with the N-terminus of L2 is necessary and sufficient for preventing infection by bovine papillomavirus type 4. Virology. 1995;211:204–208. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen E Y, Howley P M, Levison A D, Seeburg P H. The primary structure and genetic organization of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 genome. Nature. 1982;299:529–534. doi: 10.1038/299529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow L T, Broker T R. In vitro experimental systems for HPV: epithelial raft cultures for investigations of viral reproduction and pathogenesis and for genetic analyses of viral protein and regulatory sequences. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(97)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen N D, Kreider J W. Antibody-mediated neutralization in vivo of infectious papillomavirus. J Virol. 1990;64:3151–3156. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3151-3156.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dovretzky I, Shober R, Chattopadhyay S K, Lowy D R. A quantitative in vitro focus assay for bovine papilloma virus. Virology. 1980;103:369–375. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dürst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, zur Hausen H. A new papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3812–3815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaukroger J, Bradly A, O'Neil B, Smith K, Campo S M, Jarrett W. Induction of virus-producing tumours in athymic nude mice by bovine papillomavirus type 4. Vet Rec. 1989;125:391–392. doi: 10.1136/vr.125.15.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaukroger J, Chandrachud L, Jarrett W F, McGravie G E, Yeudall W A, McCaffery R E, Smith K T, Campo M S. Malignant transformation of a papilloma induced by bovine papillomavirus type 4 in the nude mouse renal capsule. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1165–1168. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-5-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaukroger J M, Chandrachud L M, O'Neil B W, Grindlay G J, Knowles G, Campo M S. Vaccination of cattle with bovine papillomavirus type 4 L2 elicits the production of virus neutralizing antibodies. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1577–1583. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross G E, Jablonska S, Hügel H. Skin: diagnosis. In: Gross G E, Barrasso R, editors. Human papilloma virus infection. Wiesbaden, Germany: Ullstein Mosby; 1997. pp. 65–123. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howley P M. Papillomaviridae: the viruses and their replication. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarrett W F H, O'Neil B W, Gaukroger J M, Smith K T, Laird H M, Campo M S. Studies on vaccination against papillomaviruses: the immunity after infection and vaccination with bovine papillomaviruses of different types. Vet Rec. 1990;126:473–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreider J W, Howett M K, Lill N L, Bartlett G L, Zaino R J, Sedlacek T V, Mortel R. In vivo transformation of human skin with human papillomavirus type 11 from condylomata acuminata. J Virol. 1986;59:369–376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.369-376.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreider J W, Ziano R, Welsh P A, Patrick S D. Host factors regulating survival and growth of HPV-transformed human cells. UCLA Symp Mol Cell Biol New Ser. 1990;124:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobe D C, Kreider J W, Phelps W C. Therapeutic evaluation of compounds in the SCID-RA papillomavirus model. Antivir Res. 1998;40:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostrow R S, Forslund K M, McGlennen R C, Shaw D P, Schlievert P M, Ussery M A, Huggins J W, Faras A J. Ribavirin mitigates wart growth in rabbits at early stages of infection with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. Antivir Res. 1992;17:99–113. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(92)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phelps W C, Barnes J A, Lobe D C. Molecular targets for human papillomaviruses: prospects for antiviral therapy. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1998;9:359–377. doi: 10.1177/095632029800900501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reefschläger J, Wutzler P, Thiel K-D, Töpke H, Bärwolff D, Langen P. (E)-5-(2-bromovinyl)-2′-desoxyuridine—a new nucleoside analogue with selective inhibitory activity against herpes virus. Pharmazie. 1987;42:407–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selvakumar R, Schmitt A, Iftner T, Ahmed R, Wettstein F O. Regression of papillomas induced by cottontail rabbit papillomavirus is associated with infiltration of CD8+ cells and persistence of viral DNA after regression. J Virol. 1997;71:5540–5548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5540-5548.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snoeck R, Andrei G, de Clercq E. Specific therapies for human papilloma virus infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1998;11:733–737. doi: 10.1097/00001432-199812000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stocco dos Santos R C, Lindsey C J, Ferraz O P, Pinto J R, Mirandola R S, Benesi F J, Birge E H, Pereira C A, Beçak W. Bovine papillomavirus transmission and chromosomal aberrations: an experimental model. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2127–2135. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syrjänen S M, Syrjänen K J. New concepts on the role of human papillomavirus in cell cycle regulation. Ann Med. 1999;31:175–187. doi: 10.3109/07853899909115976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vousden K H. Papillomaviruses and assays for transforming genes. In: Collins M, editor. Practical molecular virology: viral vectors for gene expression. Vol. 8. Clifton, N.J: Humana Press; 1991. pp. 159–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]