Abstract

Objective

Assessing access to sexual and reproductive health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, experiences with intimate partner violence (IPV), and exploring sociodemographic disparities

Study Design

From September 2020 to January 2021, we recruited 436 individuals assigned female at birth (18−49 years.) in Georgia, USA for an online survey. The final convenience sample was n = 423; a response rate could not be calculated. Survey themes included: sociodemographic and financial information, access to contraceptive services/care, IPV, and pregnancy. Respondents who reported a loss of health insurance, difficulty accessing contraception, barriers to medical care, or IPV were characterized as having a negative sexual and reproductive health experience during the pandemic. We explored associations between sociodemographic variables and negative sexual and reproductive health experiences.

Results

Since March 2020, 66/436 (16%) of respondents lost their health insurance, and 45% (89/436) reported income loss. Of our sample, 144/436 people (33%) attempted to access contraception. The pandemic made contraceptive access more difficult for 38/144 (26%) of respondents; however, 106/144 (74%) said it had no effect or positive effect on access. Twenty-one respondents reported IPV (5%). COVID-19 amplified negative views of unplanned pregnancy. Seventy-six people (18%) reported at least 1 negative sexual and reproductive health experience during the pandemic; people in an urban setting and those identifying as homo/bisexual were more likely to report negative experiences (24%, 28% respectively).

Conclusion

Urban and sexual minority populations had negative sexual and reproductive health experiences during COVID-19 more than their counterparts. The pandemic has shifted perspectives on family planning, likely due to the diverse impacts of COVID-19, including loss of health insurance and income.

Implication

Females across Georgia reported varying impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on their sexual and reproductive health care. These findings could be utilized to propose recommendations for care and intimate partner violence support mechanisms, tailored to urban and sexual minority populations.

Keywords: Access, Barriers, Contraception, COVID-19, Disparities, Intimate partner violence

1. Introduction

In early 2020 a novel coronavirus, causing an infectious respiratory disease (COVID-19), spread globally. As of December 2021, over 260 million cases of COVID-19 have been diagnosed worldwide, and 5.2 million lives have been lost to the disease [1]. The US declared a public health emergency in early 2020, leading to widespread lockdowns and restrictions on movement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mandated clinic closures, supply chain disruptions and cancellation of medical procedures created barriers to critical sexual and reproductive health care [[2], [3]–4]. In Spring 2020, patient visits for contraceptive care fell by 63%, and abortion clinic visits dropped in volume by 32% [5,6]. Abortion services in the US were specifically targeted during the pandemic [7]; 15 states made efforts to restrict and prevent abortions by classifying them as “elective procedures” [8].

Humanitarian crises reduce access to sexual and reproductive health care, resulting in increased rates of unintended pregnancies, pregnancy complications, unsafe abortions, intimate partner violence, and maternal and infant mortality and compounding socioeconomic disparities [[9], [10]–11]. Prior to the pandemic, people in the state of Georgia already faced deficits in sexual and reproductive health care; half of Georgia's counties do not have an obstetrician/gynecologist, and the state's maternal mortality rate is the second highest in the nation [12,13]. Pandemic-related worries contributed to shifts in family planning preferences, particularly among women who endure systemic health and social inequalities; racial, ethnic and sexual minority populations surveyed during the pandemic were more likely to want to postpone childbearing than white / straight women [2,14].

The pandemic exacerbated gender-based power dynamics. With couples and families obligated to stay at home, in many cases with reduced or no work, existential insecurities have led to increased intimate partner violence and other harmful practices [2,15]. Intimate partner violence disproportionately impacts females of reproductive age and compromises their health and autonomy [2]. Previous research links intimate partner violence to unplanned pregnancies [16], with the implication that lockdowns and spikes in intimate partner violence during the pandemic could increase the need for abortion access [17].

In the midst of the multifaceted challenges arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, people must be able to address their sexual and reproductive health and family planning needs [4]. This cross-sectional survey aims to assess access to sexual and reproductive health services/care in a sample of individuals assigned female at birth living in Georgia (USA), their experiences with intimate partner violence, and underlying sociodemographic disparities. Given the long-term impact of undesired sexual and reproductive health outcomes, this study could inform care for reproductive-age people as they recover from the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample

We conducted a cross-sectional, online survey. Inclusion criteria were: age 18 to 49, assigned female at birth, and living in Georgia since January 2020. Two million women ages 18 to 49 live in Georgia [18]; we selected a sample size of 400 to yield standard errors of ±5%. The University Institutional Review Board approved this study on May 19, 2020.

2.2. Procedures

We collected data from September 2020 to January 2021. We recruited individuals through 2 sources: a state-wide network for research volunteers (study invitations sent via email) and social media (respondents targeted through paid advertisements on Facebook, see Figure 1 for sample advertisement). We used quota sampling to attain similar distributions of demographic characteristics as reported in state estimates; the study team monitored the demographic data and adapted the screener, recruitment strategy, and advertising accordingly.

Fig. 1.

Sample advertisement on Facebook to recruit individuals for the survey, Georgia USA (2020).

Those interested were directed to the online survey, administered through HIPAA-compliant software REDCap. Once consented and screened, respondents completed the survey. Using multiple choice questions, we captured sociodemographic and income data, sexual activity/behavior, access to sexual and reproductive health services/care, implications associated with barriers to sexual and reproductive health services/care, and partner abuse. COVID-19-related lockdowns first began in Georgia in March 2020. Therefore, the survey refers to the start of the pandemic as March 2020. When possible, we employed validated tools and questions from peer-reviewed publications [[19], [20], [21], [22]–23]. Table 1 provides an overview of the surveyed topics and constructs/publications used to assess these topics. The final survey is in Appendix B. At survey conclusion, respondents received a $5 e-gift card. We followed best practice guidelines for reporting [24].

Table 1.

Sexual and reproductive health survey topics and measures, online survey in Georgia USA (2020).

| Survey topics | Question type / description | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Basic demographics | Multiple choice questions on age, sex, gender, living situation, education, race, ethnicity | None |

| B. | Income | Multiple choice questions on income classification (high, medium, low based on persons per household), unemployment, stimulus checks | [19,20] |

| C. | General health | Multiple choice questions on health history and health insurance | None |

| D. | Sexual activity/behavior | Multiple choice questions on frequency, partners, desire, contraceptive method at last sex | [21] |

| E. | Condom access | Multiple choice questions on condom purchasing and associated stress | None |

| F. | Contraception / birth control access | Multiple choice questions on contraceptive access, associated stress, and level of difficulty | None |

| G. | Access to medical care | Multiple choice questions on appointment type, barriers, telehealth utilization, and associated stress | None |

| H. | Reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence | Multiple choice questions about frequency, recency, and type of reproductive coercion or intimate partner violence | [22, 23] |

| I. | Pregnancy | Multiple choice questions on family planning and pregnancy options. One open-ended question about the inability to access abortion | [19] |

2.3. Analysis

First, we calculated frequencies and percentages for categorical variables by survey section. Next, we created a variable to assess which respondents reported a negative sexual and reproductive health experience during the pandemic. Respondents who answered affirmatively to any one of the following questions were classified as having a negative sexual and reproductive health experience during COVID-19 [Table 1 survey topic section]: loss of health insurance [C.], difficulty accessing birth control [E and F.], inability to access contraceptive care [G.] or experiencing reproductive coercion or intimate partner violence [H.]. We explored associations between having a negative sexual and reproductive health experience and multiple sociodemographic characteristics using a chi-squared test. Finally, we assessed the open-ended responses regarding an inability to access abortion [I.].

3. Results

3.1. Respondent characteristics

Of the 436 respondents who started the online survey, 13 screened out or did not complete the survey, yielding a final sample of 423 (97% completion rate) [25]. A response rate could not be calculated. Average completion time was 14 minutes (median 12 minutes, range 4–59 minutes). Table 2 provides the demographic, financial and health-related characteristics of the 423 respondents. Our sample was generally younger, more educated, and lower income than the state population; the proportion of respondents identifying as heterosexual was significantly lower (81%) than population estimates for Georgia (95%) (see Appendix C).

Table 2.

Demographic, financial and health-related characteristics of 423 respondents, online survey in Georgia USA (2020).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 18-25 | 81 (19.1) |

| 26-30 | 79 (18.7) |

| 31-35 | 110 (26.0) |

| 36-40 | 63 (14.9) |

| 41-45 | 63 (14.9) |

| 46-49 | 27 (6.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 249 (58.9) |

| Black | 125 (29.6) |

| Asian | 29 (6.9) |

| Other or multiple races | 17 (4.0) |

| Decline to answer | 3 (0.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 385 (91.0) |

| Hispanic | 32 (7.6) |

| Decline to answer | 6 (1.4) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 420 (99.3) |

| Non-Binary | 3 (0.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 343 (81.1) |

| Bisexual | 52 (12.3) |

| Homosexual | 15 (3.5) |

| Other | 12 (2.8) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (0.2) |

| Education level | |

| High school/GED | 58 (13.7) |

| Associates degree/some college | 125 (29.6) |

| Bachelor's degree | 122 (28.8) |

| Graduate degree | 117 (27.7) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (0.2) |

| Relationship status | |

| Partnered or married | 268 (63.4) |

| Single, separated, divorced | 154 (36.4) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (0.2) |

| Residential setting | |

| Urban | 142 (33.6) |

| Suburban | 197 (46.6) |

| Rural | 84 (19.9) |

| Children living in home | |

| No | 212 (50.1) |

| Yes | 211 (49.9) |

| Income level | |

| High | 139 (32.9) |

| Middle | 118 (27.9) |

| Low | 117 (27.7) |

| Don't know / decline to answer | 49 (11.5) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Has decreased | 189 (44.7) |

| Has remained the same | 175 (41.4) |

| Has increased | 53 (12.5) |

| Decline to answer | 6 (1.4) |

| Health insurance | |

| Currently have health insurance | 353 (83.5) |

| Lost health insurance due to COVID-19 | 20 (4.7) |

| Lost health insurance, other reason | 46 (10.9) |

| Decline to answer | 4 (0.9) |

3.2. Sexual activity/behavior during COVID-19

Respondents reported some changes to their sexual activity since the start of the pandemic (Table 3 ). Sexual desire declined for 143 of 420 (34%), while 74 (18%) reported increased sexual desire since the start of the pandemic. Three-hundred-thirty respondents reported the same number of sexual partners (78%). Of the 328 respondents who had penile-vaginal sex in the past 12 months, contraception such as pills, condoms, withdrawal, or no method, accounted for 76% of methods used.

Table 3.

Sexual activity/behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of 423 individuals assigned female at birth, ages 18-49, online survey in Georgia USA (2020).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sexual desire (n=420) | |

| Increased desire | 74 (17.6) |

| Unchanged desire | 194 (46.2) |

| Decreased desire | 143 (34.0) |

| Unsure | 9 (2.1) |

| No. of sexual partners (n=421) | |

| More partners | 11 (2.6) |

| Same number | 330 (78.4) |

| Fewer partners | 71 (16.9) |

| Unsure | 9 (2.1) |

| Sexual satisfaction (n=421) | |

| Increased satisfaction | 49 (11.6) |

| Unchanged satisfaction | 235 (55.8) |

| Decreased satisfaction | 114 (27.1) |

| Unsure | 23 (5.5) |

| Vaginal sex in past 12 months (n=423) | |

| Yes | 328 (77.5) |

| No | 94 (22.2) |

| Unsure | 1 (0.2) |

| Contraceptive method used at last sex*+ (n=382) | |

| Tubal, hysterectomy, vasectomy | 31 (8.1) |

| Intrauterine device | 50 13.0) |

| Implant | 11 (2.9) |

| Injectable | 7 (1.8) |

| Pills | 67 (17.5) |

| Patch | 3 (0.8) |

| Ring | 10 (2.6) |

| Condom | 78 (20.4) |

| Withdrawal | 53 (13.9) |

| Emergency birth control | 4 (1.0) |

| Female condom | 1 (0.3) |

| Spermicide | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 66 (17.3) |

Only asked of respondents who had vaginal sex in past 12 months to explore COVID-19-related barriers to contraceptive care (n=328).

Denominator is n=382, since multiple methods could be reported.

3.3. Access to contraceptive services/care during COVID-19

Of 423 study participants, 143 (34%) attempted to access condoms and/or prescription contraception such as pills, patches, or rings during the pandemic (see Table 4 ). Thirty-eight percent of 144 respondents (27%) reported that COVID-19 made accessing their preferred contraception “slightly or much more difficult;” however, 105 (73%) stated that the pandemic had no effect or, in some cases, a positive effect on their contraceptive access.

Table 4.

Access to contraceptive services/care during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of 423 individuals assigned female at birth, ages 18 to 49, online survey in Georgia USA (2020).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Access to condoms (N=423) | |

| Attempted to access during the pandemic | 72 (17.0) |

| Unable to access | 3 (0.7) |

| Perceived as stressful | 2 (0.5) |

| Access to pills/patches/rings (N=423) | |

| Attempted to access during the pandemic | 97 (22.9) |

| Unable to access | 6 (1.4) |

| Perceived as stressful | 6 (1.4) |

| Difficulty accessing condoms/pills/patches/rings during the pandemic *(n=143) | |

| Much more difficult | 9 (6.3) |

| Slightly more difficult | 29 (20.3) |

| No effect | 102 (71.3) |

| Slightly less difficult | 1 (0.7) |

| Much easier | 2 (1.4) |

| Healthcare appointment (n=297) | |

| Had a telemedicine visit during the pandemic | 72 (24.2) |

| Likely to use again | 60 (83.3) |

| Had a contraceptive care appointment (virtuallyor in-person) | 48 (16.2) |

| Unable to receive contraceptive care | 5 (10.4) |

Respondents who had accessed or tried to access prescription birth control or condoms since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (n=143).

Of our sample, 297 of 423 (70%) had at least one scheduled appointment with a provider since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Although COVID-19 prevented some respondents from scheduling or attending other health care appointments, 43 of 48 appointments for contraceptive care were generally attended in-person or virtually (90%). Missed, cancelled and/or delayed contraceptive appointments impacted the health of 5 respondents in our sample: 2 were unable to stop their current method, which resulted in ongoing pain for 1 respondent, and 3 were unable to start the method they preferred. One of these respondents was unable to get an appointment for an intrauterine device, became pregnant, and then had an abortion.

3.4. Reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence during COVID-19

Since the start of the pandemic, 120 of 423 respondents reported increases in arguments and/or physical conflict with other adults in the home (28%), including partners (data not shown). One-hundred-six respondents (25%) had been threatened and/or physically or verbally abused by a boyfriend or partner at some time in their lives; 21 respondents stated that this individual is their current partner. Twenty-one respondents had experienced intimate partner violence since March 2020; twelve respondents stated that the abusive situation had worsened since the start of the pandemic. Eighteen respondents described having experienced reproductive coercion from their sexual partners since March 2020; 5 respondents reported that the coercion from their partner had worsened during the pandemic.

3.5. COVID-19’s impact on sexual and reproductive health across sociodemographic groups

Seventy-six respondents (18%) reported at least 1 negative sexual and reproductive health experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reported experiences included: loss of health insurance due to COVID-19 (5%), difficulty accessing birth control (27%), unable to receive contraceptive care (10%), experiencing intimate partner violence (5%) or reproductive coercion (4%). Negative experiences varied across sociodemographic groups (see Table 5 ). Respondents living in urban settings and respondents identifying with a sexual minority population were more significantly likely to report negative sexual and reproductive health experiences during the pandemic (24%, 28% respectively).

Table 5.

Associations between sociodemographic variables and having a negative SRH experience during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of 423 individuals assigned female at birth, ages 18-49, online survey in Georgia USA (2020).

| Negative | No negative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SRH experience | SRH experience | p-value | |

| n=76 | n=347 | ||

| Age group | |||

| 18-30 | 32 (20.0) | 128 (80.0) | .09 |

| 31-40 | 35 (20.2) | 138 (79.8) | |

| 41-49 | 9 (10.0) | 81 (90.0) | |

| Race | |||

| White or Caucasian | 43 (17.3) | 206 (82.7) | .33 |

| Black/African American | 24 (19.2) | 101 (80.8) | |

| Asian | 3 (10.3) | 26 (89.7) | |

| Mixed | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Arab | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 54 (15.7) | 289 (84.3) | .01 |

| Bisexual, homosexual, other | 19 (28.4) | 48 (71.6) | |

| Education level | |||

| High school/GED | 9 (15.5) | 49 (84.5) | .08 |

| Bachelor's/Associate's/some college | 54 (21.9) | 193 (78.1) | |

| Graduate degree | 12 (11.1) | 104 (88.9) | |

| Decline to answer | 0 (0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Setting | |||

| Rural | 9 (10.7) | 75 (89.3) | .04 |

| Suburban | 33 (16.8) | 164 (83.2) | |

| Urban | 34 (23.9) | 108 (76.1) | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Partnered, married | 54 (20.1) | 214 (79.9) | .38 |

| Single, dating | 22 (14.7) | 128 (85.3) | |

| Divorced, separated | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Children | |||

| Yes | 43 (20.4) | 168 (79.6) | .20 |

| No | 33 (15.6) | 179 (84.4) | |

| Income level | |||

| High | 21 (15.1) | 118 (84.9) | .09 |

| Middle | 27 (22.9) | 91 (77.1) | |

| Low | 24 (20.5) | 93 (79.5) | |

| Don't know / decline to answer | 4 (8.2) | 45 (91.8) | |

| Monthly household income | |||

| Has decreased | 41 (21.7) | 148 (78.3) | .09 |

| Has remained the same | 22 (12.6) | 153 (87.4) | |

| Has increased | 11 (20.8) | 42 (79.2) | |

| Decline to answer | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) |

Bolded p-values are significant at the 0.05 level.

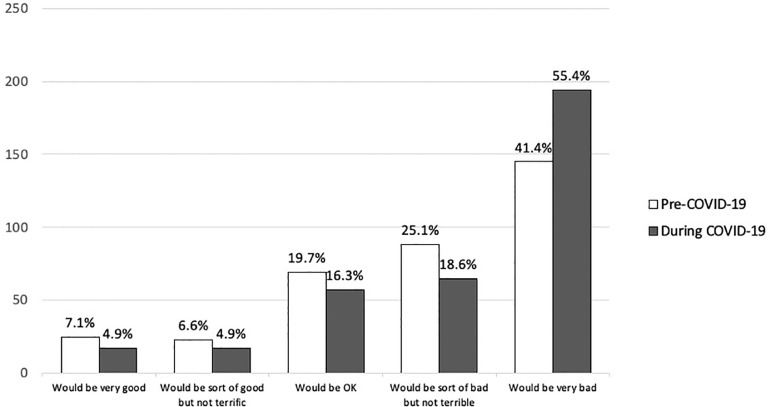

3.6. Hypothetical pregnancy

Respondents were asked how they would feel about a pregnancy prior to COVID-19 and at present, i.e., during the pandemic. We excluded 48 respondents currently pregnant or trying to become pregnant; 25 did not answer the question, leaving 350 respondents. Negative perceptions of pregnancy (“would be sort of bad” and “would be very bad”) shifted from 233 of 350 (67%) cumulatively prior to COVID-19 to 259 of 350 (74%) during COVID-19 (see Fig. 2 ). When asked what they would choose if they had a positive pregnancy test today, 165 of 342 (48%) stated that they would continue the pregnancy, 92 of 342 (27%) said they were unsure, and 80 of 342 (23%) said they would seek an abortion. Of the reasons for choosing an abortion, 50/80 responded interruption of future opportunities (63%), 49 did not want a/another baby (61%), 47 said financial reasons (59%), 45 said emotional reasons (56%), and 45 poor timing (56%). Survey respondents were asked to express their feelings if they were unable to access an abortion; responses were overwhelmingly negative. Feelings included: “awful/horrible/bad,” “angry,” “sad/depressed,” and “suicidal.”

Fig 2.

Shifts in perception of a hypothetical pregnancy prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and at present (Fall 2020), online survey of 350 individuals assigned female at birth in Georgia USA (2020).

4. Discussion

The first 10 months of COVID-19 pandemic impacted sexual behaviors, health care and wellbeing of individuals assigned female at birth. Not all respondents encountered difficulties accessing contraceptives, but some expressed heightened concern about the implications of an unplanned pregnancy during COVID-19 compared to prior to COVID-19. Nearly 1 in 5 respondents in our sample of Georgians reported that COVID-19 negatively impacted their sexual and reproductive wellbeing, using indicators such as encountering barriers to accessing health care services and contraception, and exposure to intimate partner violence. These negative experiences were significantly associated with where 1 lived and sexual orientation.

In contrast to prior COVID-19 studies, this sample population of adults in Georgia experienced fewer barriers when accessing contraception. National data from the Kaiser Family Foundation reported a 63% drop in visits for contraceptive care in Spring 2020 [5]. A Guttmacher report from April 2020 found that 33% of reproductive-age women had to delay or cancel visiting a health care provider for sexual and reproductive health care or had had trouble getting their birth control [2]. However, 73% of respondents in our study stated that the pandemic had no effect or, in some cases, a positive effect on their birth control access, and 90% of respondents were able to attend their appointments for contraceptive care in-person or via telemedicine. The reason for this difference may be due to the timing of the 2 studies: the Kaiser and Guttmacher studies were performed at a time when many states had a moratorium on all non-essential patient visits [8]. We conducted this study later in the pandemic (starting September 2020) when these moratoriums were lifted, and obstetricians/gynecologists had adapted their practices, e.g., utilizing more telemedicine [26].

Eighteen percent of respondents reported at least one negative sexual and reproductive health experience due to COVID-19. Respondents living in urban settings in Georgia were significantly more likely to report negative experiences than those in rural areas of the state. Several factors may have contributed to this difference. First, cities such as Atlanta, Savannah, and Columbus had the highest numbers of COVID-19 cases in the state [1]. As such, people living in these population-dense settings may have encountered greater hurdles to accessing care, e.g., due to fears of exposing themselves or family members to COVID-19 [2]. Second, smaller living quarters in cities combined with stay-at-home orders increase vulnerability to violence and abuse [27]. Furthermore, the ability to flee an abusive situation is even more constrained by restrictions on mobility, limited housing options and high rates of unemployment [27]. Finally, government-issued COVID-19 precautions varied substantially for urban and non-urban settings in Georgia [28]. Thus, those living in urban settings may have been more broadly impacted by COVID-19, which in turn impacted their sexual and reproductive health.

Sexual minority populations in our sample were more likely to report negative sexual and reproductive health experiences (health care access, loss of insurance) during the pandemic than heterosexual individuals. Early pandemic data demonstrated that queer women (gay, lesbian, bisexual or other) were more likely than straight women to report delays or cancellations in their sexual and reproductive health care since COVID-19, and they were more worried about being able to afford or obtain contraceptives [2]. Sexual minority populations also experience increased economic vulnerabilities in terms of employment type, household and tax benefits, putting them at greater risk of losing their health insurance [29]. These inequalities are compounded by an increased risk of severe COVID-19 disease among sexual minority populations, due to higher prevalence’s of pre-existing conditions. Public health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are working to identify and address these disparities, which have been magnified through the COVID-19 pandemic [30].

Financial concerns and job instability can impact fertility preferences. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic as well as the 2008 financial crisis, more than 40% of women stated that they planned to reduce or delay childbearing due to the economic situation [2,31]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of our sample perceived an unplanned pregnancy negatively (“would be sort of bad” or “would be very bad”). During the pandemic, 45% of our sample experienced a decrease in household income, comparable with similar study samples [32]. Sixteen percent of individuals lost their health insurance. These factors may have driven the +34% increase in the number of respondents who described an unplanned pregnancy during COVID-19 as “very bad.” People consider many factors in their fertility preferences and family planning, including their ability to appropriately care for their present and future children, their employment and their family's economic stability [19,31]. As such, bolstering economic and social support may be particularly critical to protect reproductive choice, especially as people recover from the pandemic [4,33].

Findings from this study add to the body of literature on barriers to contraceptive care during COVID-19 and associated sociodemographic disparities. Limitations inherent to this study were, first, the use of internet-based recruitment, which may not be accessible to all Georgians. Second, non-probability sampling limits the generalizability of our findings. Third, our sample differed demographically from state statistics. Respondents were younger, more educated, and poorer than state estimates; this is likely due to 1 platform's strong base of university and college students and alumni in Georgia. Our survey was diverse, with 18% identifying with a sexual minority population. The proportion of lesbian and bisexual respondents was 3 times higher than general population estimates for Georgia [34], although these may underestimate sexual minority membership in younger, female populations such as ours [2,35].

COVID-19’s impact has been experienced differently by females across Georgia. These research findings could be utilized to propose recommendations for sexual and reproductive health care and intimate partner violence support mechanisms tailored to urban and sexual minority populations. Future research should aim to evaluate the long-term implications of these negative experiences on sexual and reproductive health, mental health, and economic stability.

Acknowledgments

The team would like to acknowledge Mugisha Niyibizi at the Georgia Clinical and Translational Science Alliance for her support in recruiting respondents.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research was funded by the Executive Research Committee, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Emory University School of Medicine.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2022.04.010.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. 2021.

- 2.Lindberg LD, VandeVusse A, Mueller J, Kirstein M. 2020. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the 2020 guttmacher survey of reproductive health experiences. New York. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaaf M, Boydell V, Van Belle S, Brinkerhoff DW, George A. Accountability for SRHR in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Reproduct Health Matters. 2020;28 doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1779634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd-Gher J, Shah PK. Abortion in the context of COVID-19: a human rights imperative. Sex Reproduct Health Matters. 2020;28 doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1758394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weigel G, Salganicoff A, Ranji U. Potential Impacts of Delaying “Non-Essential” Reproductive Health Care – Issue Brief – 9492 | KFF.

- 6.Andersen M, Bryan S, Slusky D. IZA Institute of Labor Economics; 2020. COVID-19 Surgical abortion restriction did not reduce visits to abortion clinics. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aly J, Haeger KO, Christy AY, Johnson AM. Contraception access during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contracept Reproduct Med. 2020;5:17. doi: 10.1186/s40834-020-00114-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheckman R. Boston University; Boston: 2021. Abortion access and Covid-19. public health post. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall KS, Samari G, Garbers S, et al. Centring sexual and reproductive health and justice in the global COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395:1175–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kissinger P, Schmidt N, Sanders C, Liddon N. The effect of the hurricane Katrina disaster on sexual behavior and access to reproductive care for young women in New Orleans. Sexual trans dis. 2007;34:883–886. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074c5f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellizzi S, Nivoli A, Lorettu L, Farina G, Ramses M, Ronzoni AR. Violence against women in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstetr. 2020;150:258–259. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zertuche AD, Spelke B, Julian Z, Pinto M, Rochat R. Georgia Maternal and Infant Health Research Group (GMIHRG): mobilizing allied health students and community partners to put data into action. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1323–1332. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-1996-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zertuche AD. Georgia Obstetrical and Gynecological Society; Atlanta, GA: 2015. Georgia's obstetric crisis: origins, consequences, and potential solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin TK, Law R, Beaman J, Foster DG. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic security and pregnancy intentions among people at risk of pregnancy. Contraception. 2021;103:380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar N. COVID 19 era: a beginning of upsurge in unwanted pregnancies, unmet need for contraception and other women related issues. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2020;25:323–325. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2020.1777398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe T, van der Meulen Rodgers Y. Abortion during the covid-19 pandemic: racial disparities and barriers to care in the USA. Sex Res Social Policy. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00569-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quick Facts: Georgia. United States Census Bureau.

- 19.Clark EA, Cordes S, Lathrop E, Haddad LB. Abortion restrictions in the state of Georgia: Anticipated impact on people seeking abortion. Contraception. 2021;103:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs. Washington DC: US Department of Human and Health Services; 2019.

- 21.Li W, Li G, Xin C, Wang Y, Yang S. Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in China. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.04.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraft JM, Snead MC, Brown JL, et al. Reproductive coercion among African American female adolescents: associations with contraception and sexually transmitted diseases. J Womens Health. 2021;30:429–437. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grasso DJ, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Goldstein BL, Ford JD. Profiling COVID-related experiences in the United States with the Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory: Linkages to psychosocial functioning. Brain Behav. 2021;n/a:e02197. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers S, Nimon K, Anthony-McMann P. A primer for conducting survey research using MTurk: Tips for the field. Int J Adult Vocational Educ Technol. 2016;7 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weigel G, Frederiksen B, Ranji U, Salganicoff A. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. How OBGYNs adapted provision of sexual and reproductive health care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Policy Brief: COVID-19 in an Urban World. New York: United Nations; 2020.

- 28.Bluestein G, Redmon J. Kemp's ban of mask mandates puts Georgia on collision course with its cities. Atlanta J-Constitut. Atlanta. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzales G, Loret de Mola E. Potential COVID-19 Vulnerabilities in Employment and Healthcare Access by Sexual Orientation | Springer Publishing.

- 30.Heslin K, Hall J. Sexual orientation disparities in risk factors for adverse COVID-19–related outcomes, by race/ethnicity — behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021:149–154. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a1. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindberg LD, Finer L. 2009. A real-time look at the impact of the recession on women's family planning and pregnancy decisions. New York. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond-Smith N, Logan R, Marshall C, et al. COVID-19′s impact on contraception experiences: Exacerbation of structural inequities in women's health. Contraception. 2021;104:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira-Filho ES, de Melo NR, Sorpreso ICE, et al. Contraception and reproductive planning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:615–622. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1782738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Williams Institute UCLA School of Law . 2019. LGBT demographic data interactive. Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones JM. Gallup, Inc.; 2021. LGBT Identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.