Abstract

Bombyx mori is a key insect in the sericulture industry and one of the very important economic animals that are responsible for not only the livelihood of many farmers internationally but also expended biomedical use. The National Institute of Agricultural Sciences of the Rural Development Administration of Korea (NIAS, RDA, Korea) has been collecting silkworm resources with various phenotypic traits from the 1960s and established breeding lines for using them as genetic resources. And these breeding line strains have been used to develop suitable F1 hybrid strains for specific use. In this study, we report the whole-genome sequences of 37 breeding line B. mori strains established over the past 60 years, along with the description of their phenotypic characteristics with photos of developmental stages. In addition, we report the example phenotypic characteristics of the F1-hybrid strain using these breeding line strains. We hope this data will be used as valuable resources to the related research community for studying B. mori and similar other insects.

Subject terms: Animal breeding, Comparative genomics, Genetic engineering

| Measurement(s) | Larval period • Cocoon yield • Single cocoon weight • Egg color • Cocoon shape • Number of cocoons per liter • Voltinism • Moltinism • Cocoon color• Larva pattern |

| Technology Type(s) | Clock Device • scale • Eye • amount |

| Factor Type(s) | Artificial feed • Target Season |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Bombyx mori |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | house |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | South Korea |

Background

The domestic silkworm, Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae), has been domesticated more than 5,000 years ago1. It is a key insect in the sericulture industry and one of the very important economic animals that are responsible for the livelihood of many farmers internationally. The sericulture industry, which raises silkworms and obtains silk, is a very labor-intensive primary industry and global production continues to decrease due to a decline of production in China, which accounted for the majority of the world’s raw silk production with India (https://inserco.org/en/statistics). However, it is still one of the most important economic animals and is being used as a new source of income in some developing countries. In addition to the simple use of B. mori as silk sources in the textile industry, the use of silkworms and silkworm by-products is further expanded in the fields of drugs, tissue engineering, medical textiles, drug delivery systems, cosmeceuticals, food additives, and manufacturing of valuable biomaterials. Therefore, the importance of B. mori as an important animal resource is increasing2,3.

As long as the long domestication period of 5000 years, silkworms have been bred to have phenotypes suitable for specific use through strong selection. Domesticated silkworm can produce a large amount of silk and some of them are known to produce 10 times more silk than Bombyx mandarina, which is known as a wild type species of B. mori4,5. However, as the environment of sericulture is changing and the usability of B. mori is expanded beyond simple silk production, strains with various phenotypes have the potential to be utilized for various purposes as important biological resources. Because of this importance, even though silk production in general farms is decreasing in South Korea, national research institutes have continuously made efforts to secure useful genetic resources by constructing breeding lines for various strains of B. mori. The National Institute of Agricultural Sciences of the Rural Development Administration of Korea (NIAS, RDA, Korea) has been collecting silkworm resources with various expression traits from the 1960s and established a breeding line for using them as genetic resources for F1 hybrid. Strains with various phenotypes can be usefully utilized to enhance specific phenotypes depending on the purpose of use through additional selective breeding and crossbreeding. And they are valuable biological resources to prepare for unexpected environmental changes such as feeding. In addition, the whole-genome sequences of these strains linked to their phenotypes can be used as a major research resource to expand our knowledge of molecular background about B. mori.

In this study, we report the whole-genome sequences of 37 breeding line B. mori strains established over the past 60 years, along with a description of phenotypic characteristics and photos. These whole-genome sequences linked to the phenotypic characteristics of the established breeding line could be valuable resources for the understanding of B. mori genome and provide more insight into the molecular background of various phenotypes.

Methods

Construction and maintenance of breeding lines

For the 37 breeding line strains reported in this study, individuals with phenotypic singularities were first produced through two-way or three-way hybridization using locally collected B. mori strains after the Korean war. All 37 strains were fixed as a breeding line for F1 Hybrid production through selective self-crossing for a minimum of 10 generations so that the strain could maintain the specific phenotype continuously. The established breeding line strain produces 1 generation per year by hatching and raising eggs from the spring and preserving the eggs secured through self-breeding. Egg incubation is carried out under 16 h of light conditions at 15–26°C and 75–80% humidity. After hatching, 1–3 instars are raised at 25–26°C and humidity of 75–80%, and 4–5 instars are raised at 23-24 degrees and humidity of 65–75%. In all instar stages, mulberry leaves are fed 3 times a day to maintain the breeding line.

Library construction and data generation

For whole-genome sequencing of 37 breeding line strains, representative male individuals for each strain were randomly selected during the pupa stage. The epidermis tissue was isolated from the pupa and DNA was extracted using the QIAGEN DNesay Blood & Tissue Kit. The extracted DNA was subjected to gel electrophoresis to confirm DNA fragmentation, and trinean, picogreen, bioanalyzer were used to check the quality of the DNA. For five tri-molt mutant strains(KRSM, SH, HS, S7 and SD), the sequencing library was constructed using the MGIEasy DNA Library Prep Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol and target size of constructed library was 500 bp. 150 bp paired-end data for 5 strains were generated using MGISEQ-2000 sequecing platform. Libraries for remaing 32 strains were constructed using Illumina Truseq Nano DNA LT Kit and target size of constructed library was 700 bp. 150 bp paired-end data for 32 strains were generated using Illumina Nextseq 500.

Genomics variants and phylogenetic relationship using p50T reference strain

Adapter sequence and low-quality bases were removed by using Trimmomatic6 with adapter sequence, and filtered reads were mapped to the reference p50T genome7 from NCBI Refseq using bwa-mem28 with default parameter. Removal of PCR duplicated reads and variant calling was performed using samtools9, and only biallelic Single Nucleotide Variant(SNV) loci without missing in 38 samples including p50T strain were extracted using VCFtools10. InDel and structural variants for each strain were identified using SvABA11. All identified variant information can be found in (samtools: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U3VVh_Q5ER-I6OtcpuqAunHZFtnbaQjG/view?usp = sharing) and (SvABA: https://github.com/asleofn/B_Mori/). Identified SNVs were annotated using SnpEff using custom DB infromation using Refseq annotation. The cladogram was constructed through the Neighbor-joining algorithm using Tassel 512.

Data Records

The entire data set described in this study is deposited under NCBI Bioproject accession PRJNA75138713 and NCBI SRA accession SRP33103413 and accession number for each sample can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Summary information of generated whole-genome sequence for 37 breeding line B. mori strain.

| Strain | Intrument | Read Type | Read Count | Length (bp) | Total Bases (bp) | SRA accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jam123 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 62,362,042 | 151 | 18,833,336,684 | SRR15338622 |

| Jam124 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 65,995,441 | 151 | 19,930,623,182 | SRR15338620 |

| Jam125 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 55,525,443 | 151 | 16,768,683,786 | SRR15338621 |

| Jam126 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 61,498,288 | 151 | 18,572,482,976 | SRR15338615 |

| Jam140 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 58,794,853 | 151 | 17,756,045,606 | SRR15338616 |

| Jam143 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 59,536,298 | 151 | 17,979,961,996 | SRR15338617 |

| Jam144 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 60,463,356 | 151 | 18,259,933,512 | SRR15338618 |

| Jam145 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 68,058,204 | 151 | 20,553,577,608 | SRR15338619 |

| Jam149 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 62,816,706 | 151 | 18,970,645,212 | SRR15508057 |

| Jam150 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 58,012,320 | 151 | 17,519,720,640 | SRR15508056 |

| Jam151 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 66,515,659 | 151 | 20,087,729,018 | SRR15508055 |

| Jam152 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 64,421,250 | 151 | 19,455,217,500 | SRR15508054 |

| Jam153 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 64,803,442 | 151 | 19,570,639,484 | SRR15514279 |

| Jam155 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 64,822,995 | 150 | 19,446,898,500 | SRR15514277 |

| Jam156 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 58,934,629 | 150 | 17,680,388,700 | SRR15514276 |

| Jam157 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 59,638,317 | 150 | 17,891,495,100 | SRR15514275 |

| Jam158 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 59,925,450 | 150 | 17,977,635,000 | SRR15514274 |

| Jam159 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 60,621,724 | 150 | 18,186,517,200 | SRR15514273 |

| Jam160 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 73,894,375 | 150 | 22,168,312,500 | SRR15520445 |

| Jam161 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 54,746,420 | 150 | 16,423,926,000 | SRR15520444 |

| Jam162 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 64,887,891 | 150 | 19,466,367,300 | SRR15520443 |

| Jam307 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 59,948,320 | 150 | 17,984,496,000 | SRR15520442 |

| Jam311 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 55,223,930 | 150 | 16,567,179,000 | SRR15520441 |

| Jam312 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 67,940,967 | 150 | 20,382,290,100 | SRR15520440 |

| Jam313 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 63,104,719 | 150 | 18,931,415,700 | SRR15520439 |

| Jam314 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 59,084,654 | 150 | 17,725,396,200 | SRR15521833 |

| Jam315 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 62,226,371 | 150 | 18,667,911,300 | SRR15521832 |

| Jam317 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 55,780,800 | 150 | 16,734,240,000 | SRR15521830 |

| Jam318 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 51,913,987 | 150 | 15,574,196,100 | SRR15521829 |

| Jam319 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 65,747,515 | 150 | 19,724,254,500 | SRR15521828 |

| Jam320 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 57,962,038 | 150 | 17,388,611,400 | SRR15521827 |

| Jam321 | Nextseq 500 | Paired | 57,346,061 | 150 | 17,203,818,300 | SRR15521826 |

| KRSM | MGIseq-2000 | Paired | 199,692,448 | 150 | 59,907,734,400 | SRR15525308 |

| SH | MGIseq-2000 | Paired | 57,272,074 | 150 | 17,181,622,200 | SRR15458431 |

| HS | MGIseq-2000 | Paired | 52,774,714 | 150 | 15,832,414,200 | SRR15458432 |

| S7 | MGIseq-2000 | Paired | 59,371,675 | 150 | 17,811,502,500 | SRR15458433 |

| SD | MGIseq-2000 | Paired | 49,763,805 | 150 | 14,929,141,500 | SRR15458430 |

Table 2.

Phenotypes, silk production statistics and sequence accession information for 37 B. mori breeding lines.

| Strain | Larval period (days.hrs) | * Pupation Percentage (%) |

** Cocoon yield (Kg) |

*** No. of cocoons per liter (EA) |

**** Single cocoon weight(g) |

***** Cocoon shell percentage (%) |

Voltinism | Moltinism | ****** Egg color |

****** Cocoon color |

Cocoon shape | SRA Accession | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th instar | Total instar | ||||||||||||

| Jam123 | 7.2 | 24.22 | 86.3 | 14.9 | 88 | 1.77 | 22.4 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Peanut | SRR15338622 |

| Jam124 | 7.06 | 25.04 | 94.7 | 16.3 | 66 | 1.78 | 22.8 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Oval | SRR15338620 |

| Jam125 | 7.07 | 26.05 | 74.7 | 10.1 | 92 | 1.47 | 20.1 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Rectangle | SRR15338621 |

| Jam126 | 7.06 | 25.04 | 93.3 | 14.8 | 76 | 1.85 | 22.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Oval | SRR15338615 |

| Jam140 | 7.04 | 25.02 | 92.8 | 15.8 | 65 | 1.82 | 24.6 | 2 | 4 | Bb | W | Oval | SRR15338616 |

| Jam143 | 7.08 | 26.06 | 80.4 | 11.1 | 103 | 1.51 | 23.6 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Peanut | SRR15338617 |

| Jam144 | 7.05 | 25.03 | 90.5 | 14.7 | 62 | 1.85 | 22.9 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Oval | SRR15338618 |

| Jam145 | 8.04 | 26.06 | 95.5 | 16.1 | 94 | 1.69 | 23.5 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Rectangle | SRR15338619 |

| Jam149 | 7.16 | 25.22 | 79.9 | 13 | 93 | 1.7 | 22.4 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Rectangle | SRR15508057 |

| Jam150 | 7 | 25.22 | 96 | 14.9 | 79 | 1.65 | 24.8 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Oval | SRR15508056 |

| Jam151 | 7.23 | 26.21 | 84.3 | 14.9 | 81 | 1.86 | 22.5 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Oval | SRR15508055 |

| Jam152 | 8 | 25.22 | 91 | 16.1 | 58 | 1.93 | 21.2 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Rectangle | SRR15508054 |

| Jam153 | 7.23 | 26.21 | 90.6 | 16.8 | 94 | 1.83 | 22.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Peanut | SRR15514279 |

| Jam155 | 6.2 | 25.02 | 94.2 | 17.7 | 62 | 2.13 | 19.2 | 2 | 4 | Bb | W | Oval | SRR15514277 |

| Jam156 | 7.16 | 25.14 | 94.6 | 15.6 | 64 | 1.95 | 22.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Rectangle | SRR15514276 |

| Jam157 | 7.04 | 26.02 | 97.9 | 15.8 | 96 | 1.67 | 21.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Rectangle | SRR15514275 |

| Jam158 | 8 | 25.22 | 93 | 16.2 | 61 | 1.62 | 28.6 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Rectangle | SRR15514274 |

| Jam159 | 7.04 | 26.02 | 94.1 | 15.4 | 78 | 1.75 | 21.7 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Peanut | SRR15514273 |

| Jam160 | 7.06 | 25.04 | 92.3 | 16.9 | 73 | 1.96 | 22 | 2 | 4 | Bb | W | Oval | SRR15520445 |

| Jam161 | 7.22 | 26.04 | 86.4 | 14.2 | 85 | 1.87 | 23 | 2 | 4 | Br | W | Rectangle | SRR15520444 |

| Jam162 | 8 | 25.22 | 96.8 | 18.1 | 61 | 1.98 | 23.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W | Oval | SRR15520443 |

| Jam307 | 6.21 | 24.02 | 82.3 | Almost no cocoon (partial sericin cocoon) | 2 | 4 | Br | — | SRR15520442 | ||||

| Jam311 | 6 | 23.22 | 96.9 | 14.5 | 88 | 1.58 | 16.8 | 2 | 4 | Br | Y | Peanut | SRR15520441 |

| Jam312 | 7.05 | 24.21 | 93 | 13.3 | 82 | 1.65 | 19.1 | 2 | 4 | Bb | Y | Oval | SRR15520440 |

| Jam313 | 5.21 | 22.02 | 89 | 11.2 | 117 | 1.35 | 11.5 | 2 | 4 | Bb | Y | Rectangle | SRR15520439 |

| Jam314 | 5.17 | 20.22 | 92.9 | 10 | 93 | 1.24 | 11.7 | 2 | 4 | Br | Y | Oval | SRR15521833 |

| Jam315 | 7.16 | 25.14 | 91.8 | 13.4 | 104 | 1.63 | 20.6 | 2 | 4 | Br | LG | Rectangle | SRR15521832 |

| Jam317 | 7.16 | 26.14 | 87.4 | 11.6 | 84 | 1.55 | 23.2 | 2 | 4 | B | W, Y | Oval | SRR15521830 |

| Jam318 | 8 | 25.22 | 91.8 | 15.7 | 65 | 1.69 | 23.1 | 2 | 4 | B | W, Y | Oval | SRR15521829 |

| Jam319 | 6.16 | 24.14 | 98.1 | 16.1 | 88 | 1.75 | 19.3 | 2 | 4 | B | W, Y | Peanut | SRR15521828 |

| Jam320 | 6.07 | 24.05 | 92 | 14.5 | 72 | 1.78 | 20.8 | 2 | 4 | B | W, Y | Rectangle | SRR15521827 |

| Jam321 | 5.23 | 23.04 | 98.5 | 14.2 | 96 | 1.53 | 15.1 | 2 | 4 | Br | LG | Rectangle | SRR15521826 |

| KRSM | 6.08 | 25.06 | 89.1 | 8.1 | 144 | 0.93 | 10.3 | 2 | 3 | B | LYG | Oval | SRR15525308 |

| SH | 7 | 24.22 | 94.9 | 14.6 | 96 | 1.62 | 18.7 | 2 | 3 | Br | LO | Oval | SRR15458431 |

| HS | 7 | 23.22 | 97.7 | 8.9 | 164 | 1.03 | 12.1 | 2 | 3 | G | W | Peanut | SRR15458432 |

| S7 | 6.04 | 22.02 | 97.4 | 8.8 | 142 | 1.06 | 11.6 | 2 | 3 | B | W | Rectangle | SRR15458433 |

| SD | 4.16 | 22.17 | 94.9 | 7.8 | 152 | 0.83 | 10.3 | 2 | 3 | G | LO | Rectangle | SRR15458430 |

#Cocoons were produced from 10 thousand of 5 instar larvae.

*Pupation Percentage (%): Probability of pupation from larva.

**Cocoon yield(kg): Weight of 10,000 cocoons containing silkworm pupa.

***No. of cocoons per liter (EA): Number of cocoons in one liter container. (for estimating the size of the cocoon)

****Single cocoon weight (g): Weight of one cocoon.

*****Cocoon shell percentage (%): Ratio of only cocoons to the weight of cocoons containing pupae.

******Color: B, black; W, white; Bb, bright brown; Br, brown; G, gray; Y, yellow; LY, light yellow; LYG, light yellow green; LO, light orange; LG, light green.

Technical Validation

Phenotypes and genome sequences of 37 breeding line strains of B. mori

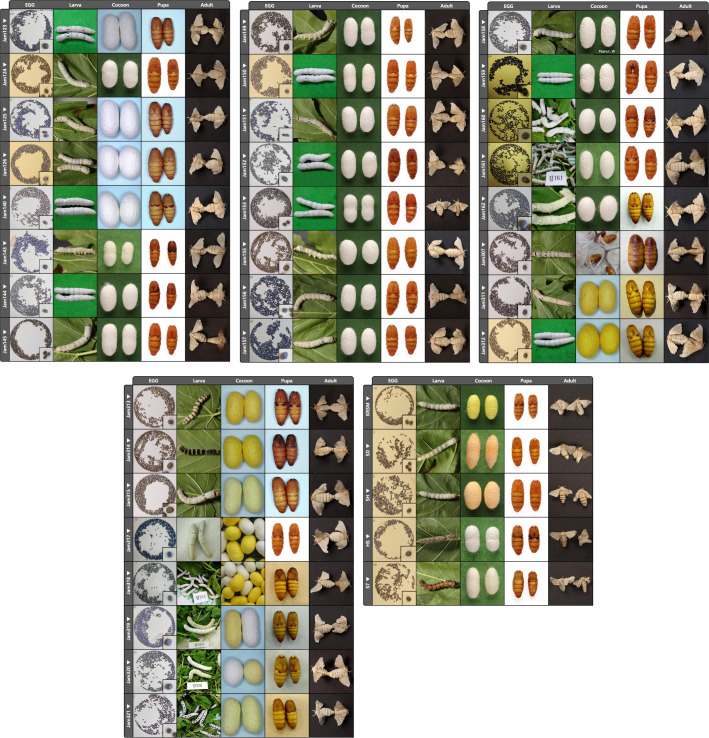

Like other countries where B. mori is managed as an important economic animal, the NIAS, RDA, Korea has collected various B. mori strains existing in South Korea since the 1960s and established breeding lines of B. mori strains as genomic resources. In the early 1970s and 1980s, breeding was carried out cantered on hardy and high silk-producing strains to increase silk production. However, from the 1990s, after Korea’s rapid industrialization, to cope with labor shortages and environmental changes, the focus was on the strains that can use artificial feed, require less labor, and are easily differentiated by gender using larval markings and cocoon colors. The 37 strains reported in this study have important values as seed strains used in the development of customized hybrid strains to respond to changes in the sericulture environment and requests from local farmers. Fig. 1 shows each picture of an egg, larva, cocoon, pupa, and adult from 37 B. mori strains. Table 1 shows the summary information of generated whole-genome sequencing data for each strain and Table 2 shows the summary of phenotypic characteristics of 37 breeding line strains with breeding performance. Minimum depth coverage of generated data was over 30X coverage based on the genome size of B. mori(about 450 Mb).

Fig. 1.

Pictures of egg, larva, cocoon, pupa, and adult of 37 breeding line strains of B. mori.

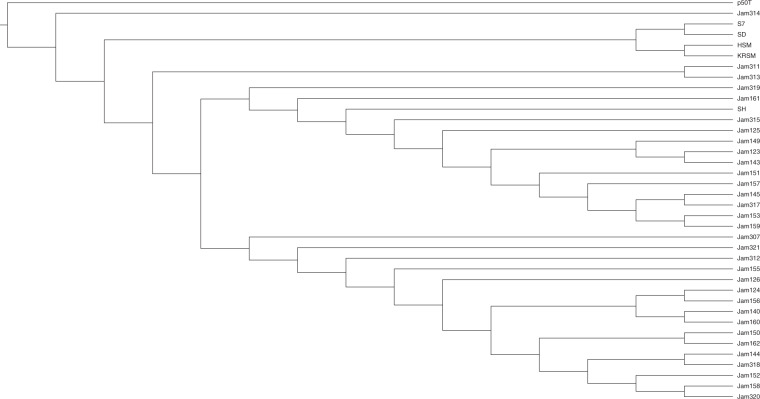

Genomic variants for each strain were identified using samtools and SvABA. A total 23,478,741 SNVs were identified from samtools and 1,506,850 SNVs(variant quality under Q30 and multiallelic loci) were filtered. Among 21,971,891 SNVs after filtering, 1,327,196 SNVs located in CDS regions. 1,002,715(75.551%) SNVs were synonymous variants and 324,481(24.449%) SNVs were non-synomymous variants. In InDel and structural variant calling using SvABA performed on individual strains, an average of 622,531 InDels and 41,348 structural variants were identified. All variant calling information is available in the link of method section. To figure out the evolutionary relationship of 37 breeding line strains including P50T, phylogenetic analysis was performed using whole-genome variants from generated sequencing data. Fig. 2 shows the phylogenetic relationship between 37 B. mori strains reported in this study with the p50T reference strain. Of the five strains showing tri-molt characteristics, four strains except SH showed a close evolutionary relationship, and some strains had closer evolutionary relationships despite the external differences. Through this, it can be expected that the external characteristics identified by the eye are regulated by the small portion of the total genomics variant and more research will be needed to expand our knowledge for the detailed association between the genomic variants and characteristics. Previously, there were several studies on the phenotype, genetic contents, and regional population of Bombyx mori14,15. However, this is the first populatoin-level whole genome data that is released from South Korea, and this is the first data set containing the details of breeding performance and phenotypic characteristics each individual strain. With existing dataset of previous study, more expanded data for understanding the gentic background of silkworm phenotype can be built. And the data reported in this study can be utilized as useful resources for marker development and is expected to help develop silkworm strains with desired traits in a short time through genomic breeding or genetic engineering.

Fig. 2.

Cladogram of 37 B. mori breeding line strains with reference p50T strain using Tassel with Neighbor-Joining method.

F1 hybrid strains obtained from 37 breed line strains

The NIAS, RDA, Korea has produced F1 hybrids with the required phenotypes using the 37 seed strains reported in this study, and generated F1 hybrid strains were annually provided to local farmers. This hybrid strain is selected from several hybrid combinations and they have various characteristics to respond to changes in the breeding environment or purpose of use. Table 3 shows the breeding performance and characteristics of representative F1 hybrid strains constructed using 37 breeding line strains. These strains have several important characteristics and the first of which is whether artificial feed can be used. The silkworm is a monophagous insect whose main diet is mulberry leaves. Mulberry leaves, which are feed for silkworms, require a lot of labor in the process of producing, storing, and providing them. Since sericulture is carried out according to the production time of mulberry leaves, there is a problem that the breeding period is limited throughout the year. If an artificial feed can be fed, the produced mulberry leaves can be utilized more longer and it reduces the labor required to prepare mulberry leaves. And also increased production through year-round feeding can be expected. In addition, they are very important due to the recent rapid climate change. These strains which can be fed artificial feed can flexibly cope with the change in the productivity of mulberry leaves. The second is a sex-limited inheritance strain that can classify gender using larval pattern or cocoon color. In the case of sex classification of silkworms, classification is possible through the tail part of the 5 instar period or the shape of pupa, but if classification is performed using larva’s pattern or color, a lot of labor for gender classification can be effectively reduced. The third is a hybrid strain that produces color silk. Among the 37 breeding line strains, the strain producing cocoons with yellow and light green colors has a lower cocoon size compared to the general strain for silk production. Therefore, hybrid strain is a strain that effectively improved the existing low color silk production. In addition to the direct use of color silk itself, these strains can be used as functional strains for carotenoids or flavonoids required for color silk generation. The fourth is a strain that does not produce a cocoon. The breeding line strain Jam307 in this study produces very few cocoons. Only about 1.2% of individuals produce fibroin-free, sericin-only nets. By dissecting the silk gland of this strain, it can be seen that the posterior silk gland, which is important for fibroin-based filamentation, is degenerated. In the Jam307 x Jam126 hybrid strain, which produces relatively large larva and pupa compared to Jam307, most individuals form sericin nets and normal silk with fibroin was not generated. Through this, it can be expected that the characteristic of Jam307, which produces silk composed only of sericin due to the degeneration of the posterior silk gland, is a dominant trait. This hybrid strain that does not make a cocoon is mainly utilized to use the silkworm itself, such as cordyceps production and silkworm powder for a food additive. Lastly, the most recently developed strain is a hybrid strain of KRSM and Jam124. The phenotypic results were not included in Table 3 because the breeding performance evaluation was not completed yet, but the KRSM x Jam124 hybrid strain has the following characteristics. The KRSM x Jam124 hybrid strain produces light green silk like tri-molt characteristics like B. mori KRSM, but the silk production is similar to the general silk production strain. Fig. 3 shows the cocoons of KRSM, Jam124, and KRSM x Jam124 hybrid strains. The cocoon size of the hybrid strain is almost similar to the silk production strain Jam124. In addition to the increased cocoon size, the total larval period was surprisingly shortened. Unlike KRSM and Jam124, which have larval periods of 25.06 and 25.04 days.hrs, respectively, the total larval period of this hybrid strain was 20.04 days.hrs. It is about 20% shorter than the original strains. Since a 20% reduction in production time can increase silk production as well as reduce the production cost, the hybrid strain is being developed as a useful resource that can contribute to productivity improvement. In addition, the whole genome sequences reported in this study can help to provide more insight into the genetic background of B. mori phenotype and develop modified strain for specific use using genetic engineering.

Table 3.

Summary of phenotypic characteristics and breeding performance of F1 hybrid strains.

| Hybrid Strain | Larval Period (days.hrs) | * Pupation Percentage (%) |

** Cocoon yield (Kg) |

*** No. of cocoons per liter (EA) |

**** Single cocoon weight(g) |

***** Cocoon shell percentage (%) |

Moltinism | Cocoon color | Cocoon shape | Target Season | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jam123 x Jam124 | 24.02 | 95.4 | 24.2 | 61 | 2.56 | 24.9 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | ※Artificial Feed |

| Jam125 x Jam126 | 22.19 | 94.3 | 22.3 | 62 | 2.41 | 24.4 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Fall |

※Artificial Feed Sex determinant using larva pattern (♂:X, ♀:O) |

| Jam125 x Jam140 | 23.18 | 95.8 | 23.6 | 53 | 2.48 | 25.2 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | ※Artificial Feed |

| Jam143 x Jam144 | 23.13 | 95.9 | 20.8 | 54 | 2.25 | 24 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | Sex determinant using larva pattern (♂:X, ♀:O) |

| Jam307 x Jam126 | 23.06 | 82.8 | Sericin cocoon | — | 4 | — | — | Fall | Sericin cocoon | ||

| Jam151 x Jam152 | 24.15 | 95.7 | 25 | 48 | 2.71 | 24 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring | Sex determinant using larva pattern (♂:X, ♀:O) |

| Jam311 x Jam312 | 22.23 | 95.3 | 18.9 | 67 | 1.99 | 19.7 | 4 | Y | Rectangle | Spring | Yellow Silk Production |

| Jam315 x Jam316 | 23.01 | 96.7 | 21.9 | 56 | 2.31 | 23.1 | 4 | LG | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | Light Green Silk Production |

| Jam153 x Jam154 | 25.04 | 94.1 | 21.4 | 56 | 2.32 | 24.7 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring | Sex determinant using larva pattern (♂:X, ♀:O) |

| Jam155 x Jam156 | 24.15 | 96.4 | 25.4 | 44 | 2.72 | 23.2 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring | Big Larva Size, High Silk Production |

| Jam157 x Jam158 | 23.18 | 95.9 | 22.6 | 57 | 2.4 | 23.6 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring | ※Artificial Feed |

| Jam317 x Jam318 | 24.06 | 93.2 | 21.3 | 54 | 2.29 | 24 | 4 | W, Y | Rectangle | Spring | Sex determinant using cocoon color (♂:W, ♀:Y) |

| Jam161 x Jam162 | 22.04 | 92 | 18.2 | 51 | 2.08 | 23.5 | 4 | W | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | Sex determinant using larva pattern (♂:X, ♀:O) |

| Jam319 x Jam320 | 24.03 | 94.9 | 20.6 | 60 | 2.22 | 21.8 | 4 | W,Y | Rectangle | Spring, Fall | Sex determinant using larva pattern and cocoon color (♂:X, W, ♀:O, Y) |

#Cocoons were produced from 10 thousand of 5 instar larvae.

*Pupation Percentage (%): Probability of pupation from larva.

**Cocoon yield(kg): Weight of 10,000 cocoons containing silkworm pupa.

***No. of cocoons per liter (EA): Number of cocoons in one liter container. (for estimating the size of the cocoon).

****Single cocoon weight (g): Weight of one cocoon.

*****Cocoon shell percentage (%): Ratio of only cocoons to the weight of cocoons containing pupae.

******W, white; Y, yellow; LG, light green.

※Artificial Feed: Pupation possible only using artificial feed in all stage.

Fig. 3.

Cocoon of F1 hybrid offspring between male KRSM and female Jam124. All F1 hybrid offspring were tri-molt mutants with a short larval period and the cocoon size was similar to normal B. mori with LYG color.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ013338) Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author contributions

Seong-Wan Kim and Min Jee Kim: Sample production, collection, and sequencing, data organization. Seong-Ryul Kim, Jeong Sun Park, Kee-Young Kim, and Ki Hwan Kim: Sample production and collection. Woori Kwak and Iksoo Kim: funding, sequencing, study design, data organization

Code availability

All generated sequencing raw reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession PRJNA751387. The following commands were used to identify the phylogenetic relationship between breeding line strains.

<Adapter Trimming: Trimmomatic v0.39>

java -jar trimmomatic-0.39.jar PE -threads 12 ILLUMINACLIP:<Adapter Fasta>:2:30:10:2:keepBothReads LEADING:3 TRAILING:20 MINLEN:125<Read Mapping: bwa-mem2 v2.1>

bwa-mem2 mem -t 16 <reference_index> <sample_left_pair> <sample_right_pair> | samtools sort –o <sample_name>.bam –

<Remove Duplicate: samtools v1.10>

samtools rmdup <aligned_bam_file> <Remove_duplicated_bam_file>

<Variant Calling: bcftools v1.10.2>

bcftools mpileup -Ou –f <reference_file> -s <bam_list_file> | bcftools call -mv -Ov -o calls.vcf

<Variant Filtering: Vcftools v0.1.16>

vcftools --vcf calls.vcf --remove-indels --recode --max-missing 1.0--min-alleles 2 --max-alleles 2 --minQ 30

<InDel and SV calling: SvABA v1.1.3>

svaba run –t <bam_file> -p 12 -L 6 -I –a <sample_name> -G GCF_014905235.1_Bmori_2016v1.0_genomic.fna

<SNV annotation: SnpEff v5.0>

Java -jar snpEff.jar Mori <SNV.vcf>

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Seong-Wan Kim, Min Jee Kim.

Contributor Information

Woori Kwak, Email: woori@hoonygen.com.

Iksoo Kim, Email: ikkim81@chonnam.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Barber, E. J. W. Prehistoric textiles: the development of cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with special reference to the Aegean: Princeton University Press 1991.

- 2.Holland C, et al. The biomedical use of silk: past, present, future. Advanced healthcare materials. 2019;8(1):1800465. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201800465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaiswal, K.K., Banerjee, I. & Mayookha, V. Recent trends in the development and diversification of sericulture natural products for innovative and sustainable applications. Bioresource Technology Reports, p. 100614 2020.

- 4.Kômoto N. Behavior of the larvae of wild mulberry silkworm Bombyx mandarina, domesticated silkworm B. mori and their hybrid. Journal of Insect Biotechnology and Sericology. 2017;86:1_017–1_020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ômura S. Research on the behavior and ecological characteristics of the wild silkworm, Bombyx mandarina. Bull. Seric. Exp. Sta. Jpn. 1950;13:79–130. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamoto M, et al. High-quality genome assembly of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2019;107:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasimuddin, M. et al. Efficient architecture-aware acceleration of BWA-MEM for multicore systems. in 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS). IEEE 2019.

- 9.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danecek P, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wala JA, et al. SvABA: genome-wide detection of structural variants and indels by local assembly. Genome research. 2018;28(4):581–591. doi: 10.1101/gr.221028.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaubitz JC, et al. TASSEL-GBS: a high capacity genotyping by sequencing analysis pipeline. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e90346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S-W, 2022. Whole-genome sequences of 37 breeding line Bombyx mori strains and their phenotypes established since 1960s. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP331034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Xiang H, et al. The evolutionary road from wild moth to domestic silkworm. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2018;2(8):1268–1279. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong, X. et al. Reference genomes of 545 silkworms enable high-throughput exploring genotype-phenotype relationships. bioRxiv, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Kim S-W, 2022. Whole-genome sequences of 37 breeding line Bombyx mori strains and their phenotypes established since 1960s. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP331034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

All generated sequencing raw reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession PRJNA751387. The following commands were used to identify the phylogenetic relationship between breeding line strains.

<Adapter Trimming: Trimmomatic v0.39>

java -jar trimmomatic-0.39.jar PE -threads 12 ILLUMINACLIP:<Adapter Fasta>:2:30:10:2:keepBothReads LEADING:3 TRAILING:20 MINLEN:125<Read Mapping: bwa-mem2 v2.1>

bwa-mem2 mem -t 16 <reference_index> <sample_left_pair> <sample_right_pair> | samtools sort –o <sample_name>.bam –

<Remove Duplicate: samtools v1.10>

samtools rmdup <aligned_bam_file> <Remove_duplicated_bam_file>

<Variant Calling: bcftools v1.10.2>

bcftools mpileup -Ou –f <reference_file> -s <bam_list_file> | bcftools call -mv -Ov -o calls.vcf

<Variant Filtering: Vcftools v0.1.16>

vcftools --vcf calls.vcf --remove-indels --recode --max-missing 1.0--min-alleles 2 --max-alleles 2 --minQ 30

<InDel and SV calling: SvABA v1.1.3>

svaba run –t <bam_file> -p 12 -L 6 -I –a <sample_name> -G GCF_014905235.1_Bmori_2016v1.0_genomic.fna

<SNV annotation: SnpEff v5.0>

Java -jar snpEff.jar Mori <SNV.vcf>