Abstract

Objective

This article aims to review the epidemiology, etio-pathogenesis and updates in clinical diagnostics and management of unicameral bone cysts (UBC).

Methods

A computerized literature search using Cochrane database of systematic reviews, EMBASE and PubMed was performed. MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms used in searches included the following sub-headings: “unicameral bone cyst”, “epidemiology”, “etiology”, “pathogenesis”, “diagnosis”, “management” and “surgery”. Studies were analyzed based on clinical relevance for the practicing orthopedic surgeon.

Results

UBC accounts for 3% of all bone tumors and is asymptomatic in most cases. Nearly 85% of cases occur in children and adolescents, with more than 90% involving the proximal humerus and proximal femur. Despite multiple theories proposed, the exact etiology is still unclear. Diagnosis is straightforward, with radiographs and MRI aiding in it. While non-surgical treatment is recommended in most cases, in those warranting surgery, combined minimal-invasive techniques involving decompression of cyst and stabilization have gained importance in recent times.

Conclusion

There is variation in the diagnosis and treatment of UBCs among surgeons. Due to the vast heterogeneity of reported studies, no one method is the ideal standard of care. As most UBCs tend to resolve by skeletal maturity, clinicians need to balance the likelihood of successful treatment with morbidity associated with procedures and the risks of developing a pathological fracture.

Study Design

Review Article.

Keywords: Unicameral bone cyst, Current concepts, Diagnosis, Management, MRI, Steroids, Cyst decompression, DBM

Introduction

Unicameral bone cysts (UBC) or simple bone cysts are benign bone lesions that usually occur in skeletally immature individuals [1]. Though these lesions tend to expand and weaken the involved bone, they are not neoplasms in the true sense [2]. Recognized by Virchow first in 1876 [3], UBC accounts for nearly 3% of all bone tumors [4]. They tend to expand over time and weaken the involved bone. Though these cysts tend to be unilocular, in some cases, multi-locular lesions are also present [5]. Though the clinical presentation and diagnosis characteristics have been well described, the etio-pathogenesis is still not clear. Presentation of UBC to practicing orthopedic surgeons is not uncommon. However, there is still a wide variance in practice and controversy with remains to the best management modality. We planned this narrative review to address these issues and throw light on the best evidence-based diagnosis and management modalities of UBC.

Methodology

The following sub-headings were used as MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms in searches in Cochrane database of systematic reviews, EMBASE and PubMed: “unicameral bone cyst,” “epidemiology,” “etiology,” “pathogenesis,” “diagnosis,” “management” and “surgery.” A total of 346 articles in total were reviewed. We selected papers based on clinical importance to offer light on the understanding and management of UBC. Studies based on clinical relevance to the practicing orthopedic surgeon were included. Recent articles were given more importance. In this article, we aim to offer a comprehensive review of knowledge of UBCs after a literature search of articles on the etio-pathogenesis, clinical presentation, radiological assessment, and commonly used treatment strategies.

Etio-pathogenesis of UBC

The etiology of UBC has not been elucidated. Multiple theories have been proposed (Table 1), but none have been strongly proven [6–14]. These lesions were thought to be a pathologic response to trauma to bone [6, 8, 9] or due to intraosseous synovial cysts [7], resulting in venous obstruction followed by subsequent accumulation of interstitial fluid. Cohen proposed the ‘vascular theory’ where he stated the principal etiological factor to be blockage of drainage of interstitial fluid in an area of rapid remodeling of bone [10, 11]. The pressure of the fluid in the cyst was studied by Chigira et al. [12] and was found to be about 2–3 mmHg more than contralateral normal bone, further adding strength to venous obstruction being a principal etiological factor in formation of UBC. The cystic fluid was analyzed and found to contain increased levels of lysosomal enzymes compared to serum, paving the way for the enzymatic theory. Komiya et al. isolated bone resorptive factors including prostaglandins, nitrate, interleukin 1β, and proteolytic enzymes from the cyst fluid [13]. There have also been references to genetic translocation in UBC [9, 14, 15]. Vayego et al. [15] revealed a highly complex clonal rearrangement involving multiple chromosomes (4, 6, 8, 16, 21, and both 12) in an 11-year-old boy who underwent surgical treatment of UBC. Another case demonstrated an abnormal clone translocation characterized by t(16;20) (p11.2;q13.1) in a UBC in a 9-year-old child [14]. Despite these multiple theories reported, there is still no concrete evidence on the exact etio-pathogenesis of UBC.

Table 1.

Theories proposed describing the etiology of UBCs

| S. no. | Name of clinician/researcher | Proposed theory and rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virchow [3] | Occurrence due to abnormalities in local circulation |

| 2 | Jaffe and Lichtenstein [6] | Secondary response to traumatic insult leading to alteration in local circulation |

| 3 | Mirra et al. [7] | Intraosseous synovial cysts: synovial tissue displaced into the thin, cortical metaphyseal region of bones at the synovial-capsular bone reflection |

| 4 | Pommers [8, 9] | Hemorrhagic theory: intramedullary hemorrhage secondary to trauma, clot liquefaction, enzymatic degradation of the surrounding bone and finally resulting in cystic cavitation |

| 5 | Cohen [10, 11] | Cyst resulting following a response to venous occlusion in intramedullary space |

| 6 | Chigira [12] | Venous obstruction is the cause of UBC; Demonstrated increased pressure in cyst compared to contralateral normal bone |

| 7 | Komiya and Inoue [13] | Bone resorptive factors existent in cyst from onset |

| 8 | Genetic theories [9, 14] | Translocation and clonal structural rearrangement involving chromosomes described in two cases |

The gross pathology of UBC shows a single fluid-filled cavity or multi-locular lesions in some cases. The cyst fluid appears serous and clear yellow unless complicated with a pathological fracture where there is associated bleeding or hematoma [16]. The bone surrounding the cyst is non-reactive, and the cyst wall lacks epithelial lining and forms from the fibro-vascular stroma.

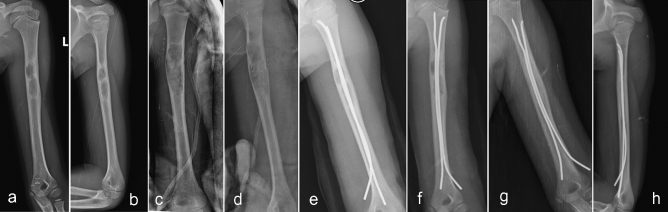

Histological analysis shows a fibrous tissue membrane, deep to which lie osteoclast giant cells, spicules of immature bone, and mesenchymal cells [2]. A fracture usually thickens the cyst wall with fibroblasts, woven bone, and hemosiderin (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemistry shows the calcified cementum-like material in the wall to be consistent with immature bone [17]. Biochemical analysis of fluid aspirated from cysts contains increased levels of prostaglandins and related enzymes [13].

Fig. 1 .

Radiograph demonstrating a centrally located lytic lesion in the calcaneum a with corresponding MRI sequence showing high signal intensity, b with homogenous intensity throughout the cyst suggestive of a UBC. Pathologic fracture of a UBC in the humerus shaft in a 9-year-old girl, c, d with the ‘fallen leaf/fragment’ sign on the radiograph. Histology showed fragments of multinucleated giant cells with focally loose fibroblasts (e) seen in UBC

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation of UBC

UBCs almost exclusively occur in children and adolescents, who account for nearly 85% of cases [2, 5, 18]. The average age at diagnosis is about 9 years [2], with the reported peak between ages 3 and 14 [1, 2, 5]. There is a male preponderance with regards to occurrence compared to females (2:1) [1, 2, 19]. More than 90% of UBCs commonly involve the proximal humerus and proximal femur [2, 4]. They typically involve the proximal portion of the medullary canal of long bones. However, studies and case reports [20–25] have shown these cysts to occur in other skeleton areas, not limited to the pelvis, spinous process, or pelvis. UBC in small bones like lunate [21] and even mandible [24] have also been reported. UBCs are not uncommon in adults. A study retrospectively analyzing 36 UBCs in the calcaneum reported most of the presentation to middle-aged patients (mean age = 37.9 years) [25].

The most crucial factor which determines the clinical presentation of UBC is whether a pathological fracture is present or not [2, 26, 27]. In patients who have an incidental discovery of the cyst, there is no pain or manifesting symptom. In cases of associated pathological fracture, patients present with pain, swelling, erythema, and associated deformity [1, 2, 26]. Nearly 80% percent of patients who have UBCs are asymptomatic [5]. Lesions are usually picked up on radiographs when they present with a history of falls or any sports-related injury. Occasionally, patients with lesions may complain of pain after strenuous exercise or workouts.

Radiological Diagnosis

Historically, plain radiographs have been used to diagnose and monitor UBCs [1–5]. However, with improvements in technology, advanced imaging has become more popular. On radiographs, UBCs appear as lytic expansile lesions within the medullary cavity of long bone (Fig. 1). They are metaphyseal in location, and the cyst arises centrally in the medullary cavity [5]. There is a narrow zone of transition and a clear matrix. If associated with fracture, the pathognomonic ‘fallen fragment sign/fallen leaf sign’ representing the detached cyst wall fragment floating in the cyst is seen [28, 29]. Classifications and prognostic scores have been designed based on radiographs. The cyst is classified as ‘active’ if it is within 10 mm from the physis and ‘latent’ if it is beyond it as they tend to progress into diaphysis [6]. The ‘cyst index’—which is calculated by dividing the cyst area by the diameter of diaphysis squared—which was proposed in 1989 [30] to prognosticate fracture risk in UBC can be done on plain radiographs. However, this index has a low intra- and inter-observer reliability and cannot reliably predict those patients who would fracture [31] and is now seldom used.

Advanced imaging, especially MRI, has been beneficial to analyze UBCs in finer detail, especially in unusual regions like the pelvis and spine [2]. UBCs demonstrate low signal intensity on T1 sequences and high signal intensity in T2 and STIR (short tau inversion recovery) sequences [2, 5, 32]. Compared to plain radiographs, MRI (T1 sequence) is superior for fracture risk prediction [33]. The utility of CT scans in UBCs has also been described. The ‘rising bubble sign’, which corresponds to a gas bubble ascending to the most non-dependent portion of the fractured bone, implying that the lesion is hollow, has been described [34]. However, concern regarding radiation exposure in children is one of the major drawbacks of CT [2]. Hence, it is only reserved to image suspected lesions not easily viewed on radiographs and, more specifically, to assess the integrity of weight-bearing regions affected by these cysts [2, 5]. Cystography aids in diagnosis and management [35]. There is no proven benefit with bone scintigraphy and PET scans either in the diagnosis or the management [5] of UBC.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for UBC includes fibrous dysplasia, aneurysmal bone cyst, enchondroma, eosinophilic granuloma, and intraosseous ganglia [36]. Knowledge of radiologic features coupled with careful assessment of radiographs should assist in making an accurate diagnosis [2]. Discussion of doubtful cases in an MDT with experienced specialists has shown to aid in precise diagnosis and facilitating appropriate treatment [37]. Each differential has specific characteristic distinguishing features and adequate knowledge of them is essential to avoid misdiagnosis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Common primary differential diagnoses for UBC and distinguishing features on location and imaging

| Differential diagnoses for UBC | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|

| Fibrous dysplasia | Typical ground glass appearance caused by cystic degeneration seen in radiographs of fibrous dysplasia |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | On radiographs, these lesions show eccentric expansion and on MRI there is characteristic double-density fluid levels and septations seen |

| Enchondroma | Well-defined intramedullary lesions associated with cortical thinning; more common in small bones |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | More destructive lytic lesions on radiographs frequently involving the axial skeleton |

| Intraosseous ganglia | Small radiolucent images commonly involving epiphysis and sub-chondral region |

Management Strategies

Management strategies for UBC are ever evolving, and the ideal treatment modality is yet to be defined. Decompression of the cyst, injection techniques, and combined surgical techniques have been described for UBC management [1, 2, 5]. Each method has been associated with favorable results, and in the general setting, there is wide variation in practice preferences among surgeons. Interesting results from a recent survey in 2020 add insight to this [38]. Four hundred and forty four surgeons from North America and Europe (90% of whom were actively involved in routine UBC treatment) responded to an online questionnaire on the modalities used to diagnose and manage UBC. There was variation in the preferred diagnostic modality and an even greater variation in surgical techniques. For painless UBC where fracture risk is deemed high, around 53% recommend surgery, whereas 71% would offer treatment to painful UBC. Even with displaced fractured cases involving UBCs, there was variation among surgeons, with surgeons opting between surgical management and conservative treatment for displaced fractures. Although no superior technique has emerged, clinicians need to make decisions appropriate for each patient to optimize care [2].

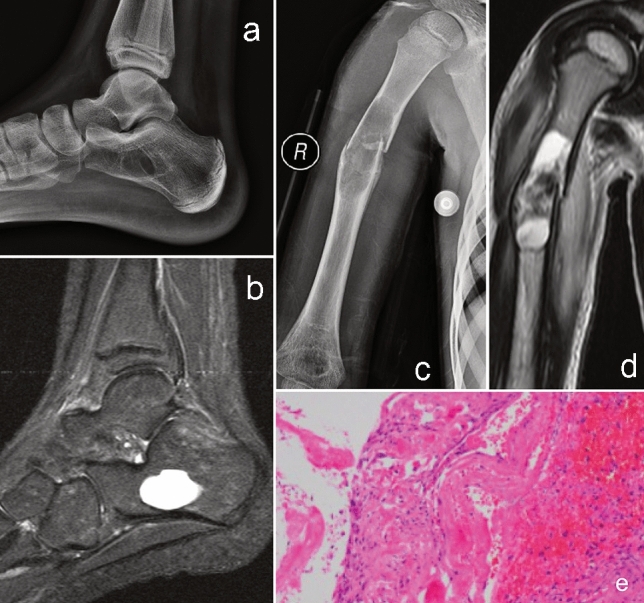

The primary aim in UBC management is to achieve complete healing of bone with normal axes to help sustain normal functional activity [2, 5, 39, 40]. Prevention of recurrence and preventing re-fracture if already fractured are also important aims guiding management. If a UBC is discovered incidentally in an asymptomatic patient, non-surgical management is advised [2]. Close follow-up with clinical examination and radiographs at three monthly intervals is advised [39]. A substantial increase of the lesion affecting the strength of the affected bone would warrant intervention. If the presentation is with a pathological fracture in the upper extremity, then an initial period of non-surgical treatment with immobilization is recommended [1–5] (Fig. 2). However, if a painless UBC occurs in the peri-trochanteric region, then strong consideration for surgical stabilization must be taken due to the risk of fracture on weight-bearing.

Fig. 2.

Pathological fracture through UBC in the humerus (a, b) was managed conservatively. Follow-up radiographs at 6 weeks (c, d) showing callus formation. Radiographs taken at 6 months of follow-up show complete union and adequate remodeling (e, f)

There are sparse literatures on the exact definition of a healed bone that constitutes successful treatment of UBC [2]. When there is a pathological fracture in UBC, there is spontaneous healing due to decompression of the cyst [1, 2] and this is seen in about 10% of patients. The use of a clinical, radiographic tool to assess healing in UBC has been described [41]. Cyst opacification, thickening of cortices, and pain status of individuals are parameters used in this tool. The authors define > 95% opacification with cortical thickening and no pain as a complete healing. Partial healing is defined as > 80–95% opacification with or without cortical thickening and incomplete healing is characterized by < 80% opacification with no thickening of cortex [2, 41].

Medical Therapy in UBC

Though the use of alendronate and botulinum toxin has been researched for managing UBCs [42, 43], as of today, there is no recommended medical therapy for managing UBC.

Percutaneous Interventions in UBC

Several agents and techniques [35, 44–57] have been used for the management of UBCs, and the reported results are variable and heterogeneous [Table 3]. Steroid injection (methylprednisolone) was first described by Scaglietti [46], and ‘favorable’ outcomes were reported in 90% of patients. The steroid dose was calculated based on the patient’s body weight, and one study reported between 60 and 250 mg of methylprednisolone used to treat patients in their series [45]. Similar results were echoed in an RCT [35] favoring steroids over autologous bone marrow. However, radiographic studies of cysts treated with steroids have shown clinically stable but unhealed cysts on long-term follow-up [2]. Recurrence rates between 15 and 88% have been reported in UBCs treated with an average of three injections [2, 56]. However, steroids have the advantage of being inexpensive and readily available compared to other described injections [35, 44, 45, 52]. The osteogenic potential of autologous bone marrow (BM) and the osteo-inductive/osteo-conductive properties of demineralized bone matrix (DBM) have driven therapies using them to stimulate bone healing [35, 44–53]. Results have been mixed with only BM, with some studies showing higher success rates in healing [45], whereas some studies showing no advantage with their use [44, 49]. Combining DBM with BM is beneficial with better healing rates [47, 48, 51]. A study comparing three minimally invasive interventions found percutaneous curettage, whereby cyst walls are disrupted, to be superior compared to steroids and BM [49].

Table 3.

Outcomes of percutaneous therapies to manage unicameral bone cysts

| S. no. | Authors | Sample size | Type of injection | Mean follow-up (years) | Outcomes | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wright et al. [35] | 77 | Steroid; BM | 2.2 | Steroid provided superior healing rate to BM (p = 0.01) | I—RCT |

| 2 | Chang et al. [44] | 79 | Steroid; BM | 3.7 | No difference between groups (p = 0.05) | III |

| 3 | Cho et al. [45] | 58 | Steroid; BM | 4.7 | Both interventions successful, but steroid group had more recurrences and needed more interventions | III |

| 4 | Di Bella et al. [47] | 184 | Steroid; DBM + BM | 4;1.6 | DBM + BM combination has higher healing rate compared to steroids | III |

| 5 | Rougraff & Kling [48] | 23 | DBM and BM | 4.1 | Combination of DBM + BM is an effective treatment; 21.7% recurrence rate | IV |

| 6 | Canavese et al. [49] | 46 | Steroid; BM; PC | 2 | PC had highest healing followed by steroid and BM | IV |

| 7 | Gundle et al. [50] | 51 | DBM + BM | 2.8 | At least two injections avoided open surgery in 78% of patients | IV |

| 8 | D’Amato et al. [51] | 53 | DBM + BM; Steroid | 2 | DBM + BM offers better healing compared to steroids | III |

| 9 | Pavone et al. [52] | 23 | Steroid | 11 | Excellent minimally invasive alternative with good response in 82.6% of patients | IV |

| 10 | Thawrani et al. [53] | 13 | α-BSM | 10.5 | α-BSM is safe alternative; Cyst resolution rate of 85.7% at final follow-up | IV |

BM autologous bone marrow, DBM demineralized bone matrix, PC percutaneous curettage, α-BSM apatitic calcium phosphate bone substitute material

The use of DBM and BM needs to be assessed with caution as the outcome variables are not standardized [2]. These agents are radiolucent, rendering interpretation of follow-up radiographs difficult. Moreover, the cost analyses of these agents have not been analyzed compared to steroids, and this could also be a significant factor in determining usage among patients. Additional long-term studies, high-level evidence is needed to prove the superiority of these biological agents over steroids in UBC treatment.

Surgical Management Techniques

Indications for surgery in UBC are limited to symptomatic patients with obvious pathological fracture, cyst enlargement during observation, or those with cysts in regions at risk for fracture like proximal femur [2, 5, 40, 57]. Risk factors for pathological fracture include cysts with > 85% transverse diameter and < 0.55 mm thickness of cyst wall [2, 5, 64]. Curettage and bone-grafting were preferred treatment in the past, but nowadays numerous techniques decompressing the cyst combining with stabilization have evolved (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 .

Pathological fracture of the humerus (a, b) with deformity due to UBC in a 10-year-old boy, which was managed with IM flexible nailing (c, d) and resulted in union at 6 months with the healing of cyst (e, f)

The healing rates after curettage and bone grafting remained as low as 25% to 36% [2, 5, 60] and increased to 66% when calcium sulfate was used [59]. Decompression of the cyst to break the cyst wall and allow marrow to enter the cavity has been the vital principle behind recent techniques [2, 5, 61–63]. Intramedullary (IM) nails, Kirschner wires, needled and cannulated screws aid in decompression. Injection of high-speed saline coupled with alternated aspiration is a described decompression technique. The use of flexible IM nails alone increased healing rates up to 70% [5, 57, 61] and < 10% recurrence rate. Combining DBM or calcium sulfate grafting with IM nails rose healing rates up to 77% and 92%, respectively [2, 63].

Combining mechanical techniques with biologic agents has gained momentum in UBC management in recent times (Table 4). Dormans et al. [63] demonstrated a 91.7% healing rate combining intramedullary decompression with flexible IM nail, curettage and calcium sulfate grafting. Favorable results were reported using this technique by different authors [50, 59]. An adjuvant of 95% ethanol to lyse the cyst membrane coupled with this technique and a 6.5 mm cannulated cancellous screw for continuous decompression was reported to have partial or complete healing in up to 92% of cases [59]. Hydroxyapatite screws (HA) have also been used for decompression, and they have the advantage of non-removal compared to flexible IM nails, which warrant a second surgery to remove them [58]. One crucial factor in all these combined techniques is decompression which violates the cyst wall and facilitates native cells into the cyst, promoting healing [2].

Table 4.

Outcomes of Surgical Management (Combined techniques) of Unicameral bone cysts

| S. no. | Authors | Sample size | Technique | Healing rate (%) | Recurrence rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shirai et al. [58] | 43 | PC + Decompression with HA pin | 88.2 | 11.6 |

| 2 | Mik et al. [41] | 55 | PC + Decompression with flexible IM nail | 80 | 0 |

| 3 | Hou et al. [59] | 12 | OC + Grafting with calcium sulfate | 66 | 25 |

| 4 | 12 | PC + IM Decompression, calcium sulfate grafting + screw insertion | 91.6 | NA | |

| 5 | Sung et al. [60] | 34 | OC + bone grafting with allograft chips | 36 | NA |

| 6 | Masquijo et al. [61] | 48 | Decompression with IM nail | 54.2 | 8.3 |

| 7 | Tena-Sanabria et al. [62] | 12 | OC + Cryotherapy + bone grafting | 75 | 0 |

| 8 | Dormans et al. [63] | 24 | PC + Decompression with flexible IM Nail + calcium sulfate grafting | 91.7 | 0 |

PC percutaneous curettage, OC open curettage, IM intra-medullary, NA not available, HA hydroxyapatite

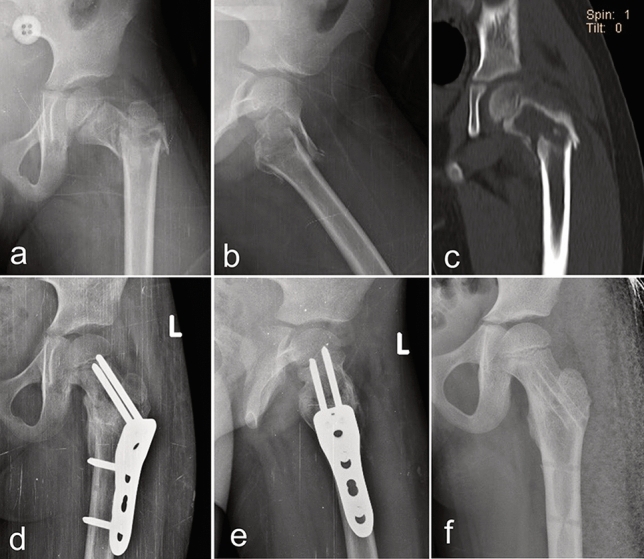

Complications of UBC

Pathologic fractures with UBCs are common [5, 30, 41, 64], and especially those involving proximal femur can lead to complications including malunion, avascular necrosis, and growth arrest [1, 2, 64–66] (Fig. 4). Limb length discrepancy due to premature epiphyseal closure can also occur in cases of growth arrest due to UBC [30, 64, 65], and about 10% growth arrest has been reported in UBC’s of the humerus [66] (Fig. 5). Management of pathological proximal femur fractures secondary to UBC has been classified [65] based on location and size of cyst and integrity of lateral buttress. In cases where there is loss of lateral buttress, pediatric side plate with hip screw is recommended. The use of biological or synthetic agents in cysts has shown exaggerated inflammatory response in few cases [2, 5].

Fig. 4 .

Proximal femoral fracture (a–c) due to UBC with loss of lateral wall integrity in a 6-year-old boy managed with curettage, allograft packing, and internal stabilization (d, e). Screws in the femoral head were not passed through the physis to avoid growth arrest problems. Complete union and resolution of the cyst were followed by implant removal (f)

Fig. 5 .

UBC in the humeral shaft with pain (a, b) on presentation in a 6-year-old girl was managed with curettage and allograft packing (c, d). At 1-year follow-up, there was evidence of recurrence with cortical thinning on radiographs and increased pain (e, f). Cyst decompression with flexible IM nail (g) was combined with steroid injection to achieve healing and resolution of the cyst (h)

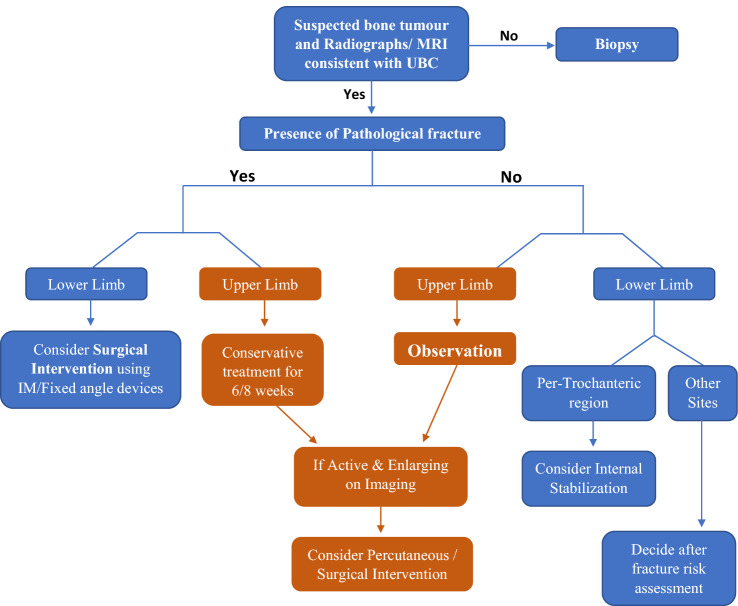

To summarize the management of UBC, it begins with an accurate diagnosis on imaging (Fig. 6). In any doubtful case, a percutaneous biopsy must be performed for histological diagnosis. The anatomical location of the cyst and the presence of an associated fracture are essential factors that guide treatment planning. While upper limb fractures can be managed conservatively with splinting, lower limbs are best treated with internal fixation devices. In those cases that present without a fracture or incidentally, a clinical decision must be taken after assessment. Lesions around the proximal femur may benefit from internal stabilization, whereas UBC in other sites can be decided based on fracture risk assessment. Upper limb lesions with a fracture are best managed conservatively followed by regular observation with serial radiographs. Enlarging or active lesions can be considered for percutaneous intervention or surgical stabilization following cyst decompression.

Fig. 6.

Illustrative algorithm depicting the diagnosis and management of suspected UBC lesions. Note: The decision on internal stabilization varies depends mainly on the anatomical location of the lesion

Prognosis of UBC

The natural history of UBC is that by the time skeletal maturity is attained, most of them resolve [30, 32]. Age of patient < 10 years and location of lesion < 2 cm from physis are associated with decreased healing and increased recurrence rates [2, 27, 67]. UBCs being benign, have no risk of metastasis. The risk of recurrence is more likely to be associated with the treatment modality than the location site [2].

Conclusion and Future Directions

UBCs account for 3% of bone tumors, and their natural history indicates resolution with skeletal maturity. However, the etio-pathogenesis is still unclear. Plain radiographs and MRI are sufficient for diagnosis in most cases and also aid in predicting fracture risk. Observation is appropriate in most asymptomatic patients. In cases warranting intervention, the wide heterogeneity of treatment methods has resulted in lack of a single ideal method as the standard of care. Newly described minimally invasive and combined techniques are promising with reasonable healing rates and low recurrence rates. Prospective studies and clinical trials comparing these techniques and analyzing best outcomes are the way forward to determine the best treatment practice for UBC.

Abbreviations

- UBC

Unicameral bone cyst

- BM

Autologous bone marrow

- DBM

Demineralized bone matrix

- IM

Intramedullary

Author Contributions

RBR conception of the study, analysis of articles, review of articles, writing of manuscript. VK reviewed the manuscript, suggested corrections in manuscript. AG conception of the study, reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethical Standard Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilkins RM. Unicameral bone cysts. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000;8(4):217–224. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pretell-Mazzini J, Murphy RF, Kushare I, Dormans JP. Unicameral bone cysts: General characteristics and management controversies. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2014;22(5):295–303. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-05-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Virchow R. Uber die bilding von knochencysten. S-B Akad Wiss; 1876. On the formation of bony cysts; pp. 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campanacci M, Capanna R, Picci P. Unicameral and aneurysmal bone cysts. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1986;204:25–36. doi: 10.1097/00003086-198603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noordin S, Allana S, Umer M, Jamil M, Hilal K, Uddin N. Unicameral bone cysts: Current concepts. Annals of medicine and surgery. 2018;2012(34):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L. Solitary unicameral bone cyst: With emphasis on the roentgen picture, the pathologic appearance and the pathogenesis. Archives of Surgery. 1942;44(6):1004–1025. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1942.01210240043003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirra JM, Bernard GW, Bullough PG, Johnston W, Mink G. Cementum-like bone production in solitary bone cysts (so-called "cementoma" of long bones). Report of three cases. Electron microscopic observations supporting a synovial origin to the simple bone cyst. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1978;135:295–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panneerselvam E, Panneerselvam K, Chanrashekar SS. Solitary bone cysts-A rare occurrence with bilaterally symmetrical presentation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology JOMFP. 2014;18(3):481. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.151366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miu A. Etiological aspects of solitary bone cysts: comments regarding the presence of the disease in two brothers. Is the genetic theory sustainable or is it pure coincidence? Case report. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2015;8(4):509–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen J. Simple bone cysts. Studies of cyst fluid in six cases with a theory of pathogenesis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1960;42A:609–616. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196042040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen J. Etiology of simple bone cyst. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 1970;52(7):1493–1497. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197052070-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chigira M, Maehara S, Arita S, Udagawa E. The aetiology and treatment of simple bone cysts. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British. 1983;65(5):633–637. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B5.6643570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komiya S, Inoue A. Development of a solitary bone cyst–a report of a case suggesting its pathogenesis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2000;120(7–8):455–457. doi: 10.1007/s004029900082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richkind KE, Mortimer E, Mowery-Rushton P, Fraire A. Translocation (16;20)(p11.2;q13) sole cytogenetic abnormality in a unicameral bone cyst. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2002;137(2):153–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vayego SA, De Conti OJ, Varella-Garcia M. Complex cytogenetic rearrangement in a case of unicameral bone cyst. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 1996;86(1):46–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian, S., Kemp, A.K., & Viswanathan, V.K. (2021). Bone Cyst. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539849/. Updated 7 Apr 2021.

- 17.Tariq MU, Din NU, Ahmad Z, Kayani N, Ahmed R. Cementum-like matrix in solitary bone cysts: A unique and characteristic but yet underrecognized feature of promising diagnostic utility. Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 2014;18(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biermann JS. Common benign lesions of bone in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2002;22(2):268–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boseker EH, Bickel WH, Dahlin DC. A clinicopathologic study of simple unicameral bone cysts. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 1968;127(3):550–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulici A, Balanescu R, Topor L, Barbu M. The modern treatment of the simple bone cysts. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2012;5(4):469–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gündeş H, Sahin M, Alici T. Unicameral bone cyst of the lunate in an adult: Case report. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2010;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakamoto A, Okamoto T, Matsuda S. Unicameral bone cyst in the pelvis: Report of a case treated by placement of screws made from a composite of unsintered hydroxyapatite particles and poly-l-lactide. Rare Tumors. 2019;11:2036361319895075. doi: 10.1177/2036361319895075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsirikos AI, Bowen JR. Unicameral bone cyst in the spinous process of a thoracic vertebra. Journal of Spinal Disorders & Techniques. 2002;15(5):440–443. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200210000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imanimoghaddam M, JavadianLangaroody A, Nemati S, AtaeiAzimi S. Simple bone cyst of the mandible: Report of two cases. Iranian Journal of Radiology. 2011;8(1):43–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polat O, Sağlik Y, Adigüzel HE, Arikan M, Yildiz HY. Our clinical experience on calcaneal bone cysts: 36 cysts in 33 patients. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2009;129(11):1489–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0779-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans, J., Shamrock, A.G., & Blake, J. (2021). Unicameral Bone Cyst. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470587. Updated 10 Jul 2020.

- 27.Urakawa H, Tsukushi S, Hosono K, Sugiura H, Yamada K, Yamada Y, Kozawa E, Arai E, Futamura N, Ishiguro N, Nishida Y. Clinical factors affecting pathological fracture and healing of unicameral bone cysts. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds J. The "fallen fragment sign" in the diagnosis of unicameral bone cysts. Radiology. 1969 doi: 10.1148/92.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Struhl S, Edelson C, Pritzker H, Seimon LP, Dorfman HD. Solitary (unicameral) bone cyst. The fallen fragment sign revisited. Skeletal Radiology. 1989;18(4):261–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00361203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaelin AJ, MacEwen GD. Unicameral bone cysts. Natural history and the risk of fracture. International Orthopaedics. 1989;13(4):275–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00268511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasconcellos DA, Yandow SM, Grace AM, Moritz BM, Marley LD, Fillman RR. Cyst index: A nonpredictor of simple bone cyst fracture. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2007;27(3):307–310. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31803409e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mascard E, Gomez-Brouchet A, Lambot K. Bone cysts: Unicameral and aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research: OTSR. 2015;101(1 Suppl):S119–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pireau N, De Gheldere A, Mainard-Simard L, Lascombes P, Docquier PL. Fracture risk in unicameral bone cyst. Is magnetic resonance imaging a better predictor than plain radiography? Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2011;77(2):230–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordanov MI. The "rising bubble" sign: A new aid in the diagnosis of unicameral bone cysts. Skeletal Radiology. 2009;38(6):597–600. doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0685-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JG, Yandow S, Donaldson S, Marley L, Simple Bone Cyst Trial Group A randomized clinical trial comparing intralesional bone marrow and steroid injections for simple bone cysts. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2008;90(4):722–730. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umer M, Hasan O, Khan D, Uddin N, Noordin S. Systematic approach to musculoskeletal benign tumors. International Journal of Surgery Oncology. 2017;2(11):e46. doi: 10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartley LJ, Evans S, Davies MA, Kelly S, Gregory JJ. A Daily diagnostic multidisciplinary meeting to reduce time to definitive diagnosis in the context of primary bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2021;14:115–123. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S266014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farr S, Balacó I, Martínez-Alvarez S, Hahne J, Bae DS. Current trends and variations in the treatment of unicameral bone cysts of the humerus: a survey of EPOS and POSNA members. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2020;40(1):e68–e76. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Q, He H, Zeng H, Yuan Y, Wang Z, Tong X, Luo W. Active unicameral bone cysts: Control firstly, cure secondly. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2019;14(1):275. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1326-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadhim M, Thacker M, Kadhim A, Holmes L., Jr Treatment of unicameral bone cyst: Systematic review and meta analysis. Journal of Children's Orthopaedics. 2014;8(2):171–191. doi: 10.1007/s11832-014-0566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mik G, Arkader A, Manteghi A, Dormans JP. Results of a minimally invasive technique for treatment of unicameral bone cysts. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2009;467(11):2949–2954. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu J, Chang SS, Suratwala S, Chung WS, Abdelmessieh P, Lee HJ, Yang J, Lee FY. Zoledronate induces apoptosis in cells from fibro-cellular membrane of unicameral bone cyst (UBC) Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2005;23(5):1004–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Namazi H. Practice pearl: A novel use of botulinum toxin for unicameral bone cyst ablation. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2008;15(2):657–658. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang CH, Stanton RP, Glutting J. Unicameral bone cysts treated by injection of bone marrow or methylprednisolone. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British. 2002;84(3):407–412. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b3.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho HS, Oh JH, Kim HS, Kang HG, Lee SH. Unicameral bone cysts: a comparison of injection of steroid and grafting with autologous bone marrow. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British. 2007;89(2):222–226. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.18116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campanacci M, De Sessa L, Trentani C. Scaglietti's method for conservative treatment of simple bone cysts with local injections of methylprednisolone acetate. Italian Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 1977;3(1):27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Bella C, Dozza B, Frisoni T, Cevolani L, Donati D. Injection of demineralized bone matrix with bone marrow concentrate improves healing in unicameral bone cyst. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2010;468(11):3047–3055. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rougraff BT, Kling TJ. Treatment of active unicameral bone cysts with percutaneous injection of demineralized bone matrix and autogenous bone marrow. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2002;84(6):921–929. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canavese F, Wright JG, Cole WG, Hopyan S. Unicameral bone cysts: Comparison of percutaneous curettage, steroid, and autologous bone marrow injections. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2011;31(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181ff7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gundle KR, Bhatt EM, Punt SE, Bompadre V, Conrad EU. Injection of unicameral bone cysts with bone marrow aspirate and demineralized bone matrix avoids open curettage and bone grafting in a retrospective cohort. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2017;11:486–492. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Amato RD, Memeo A, Fusini F, Panuccio E, Peretti G. Treatment of simple bone cyst with bone marrow concentrate and equine-derived demineralized bone matrix injection versus methylprednisolone acetate injections: A retrospective comparative study. Acta Orthopaedica et Traumatologica Turcica. 2020;54(1):49–58. doi: 10.5152/j.aott.2020.01.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavone V, Caff G, Di Silvestri C, Avondo S, Sessa G. Steroid injections in the treatment of humeral unicameral bone cysts: Long-term follow-up and review of the literature. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology: Orthopedie Traumatologie. 2014;24(4):497–503. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thawrani D, Thai CC, Welch RD, Copley L, Johnston CE. Successful treatment of unicameral bone cyst by single percutaneous injection of alpha-BSM. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2009;29(5):511–517. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181aad704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu CL, D'Astous J, Finnegan M. Simple bone cysts. The effects of methylprednisolone on synovial cells in culture. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1991;262:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Traub F, Eberhardt O, Fernandez FF, Wirth T. Solitary bone cyst: A comparison of treatment options with special reference to their long-term outcome. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2016;17:162. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1012-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oppenheim WL, Galleno H. Operative treatment versus steroid injection in the management of unicameral bone cysts. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 1984;4(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Donaldson S, Chundamala J, Yandow S, Wright JG. Treatment for unicameral bone cysts in long bones: An evidence based review. Orthopedic Reviews. 2010;2(1):e13. doi: 10.4081/or.2010.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shirai T, Tsuchiya H, Terauchi R, Tsuchida S, Mizoshiri N, Ikoma K, Fujiwara H, Miwa S, Kimura H, Takeuchi A, Hayashi K, Yamamoto N, Kubo T. Treatment of a simple bone cyst using a cannulated hydroxyapatite pin. Medicine. 2015;94(25):e1027. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hou HY, Wu K, Wang CT, Chang SM, Lin WH, Yang RS. Treatment of unicameral bone cyst: a comparative study of selected techniques. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2010;92(4):855–862. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sung AD, Anderson ME, Zurakowski D, Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC. Unicameral bone cyst: A retrospective study of three surgical treatments. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466(10):2519–2526. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0407-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masquijo JJ, Baroni E, Miscione H. Continuous decompression with intramedullary nailing for the treatment of unicameral bone cysts. Journal of Children's Orthopaedics. 2008;2(4):279–283. doi: 10.1007/s11832-008-0114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tena-González ME, Mejía-Aranguré JM. Adjuvant cryosurgery in the treatment of unicameral bone cysts. Revista Medica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. 2014;52(Suppl 2):S78–S81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dormans JP, Sankar WN, Moroz L, Erol B. Percutaneous intramedullary decompression, curettage, and grafting with medical-grade calcium sulfate pellets for unicameral bone cysts in children: A new minimally invasive technique. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2005;25(6):804–811. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000184647.03981.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahn JI, Park JS. Pathological fractures secondary to unicameral bone cysts. International Orthopaedics. 1994;18(1):20–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00180173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dormans JP, Pill SG. Fractures through bone cysts: Unicameral bone cysts, aneurysmal bone cysts, fibrous cortical defects, and nonossifying fibromas. Instructional Course Lectures. 2002;51:457–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stanton RP, Abdel-Mota'al MM. Growth arrest resulting from unicameral bone cyst. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 1998;18(2):198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haidar SG, Culliford DJ, Gent ED, Clarke NM. Distance from the growth plate and its relation to the outcome of unicameral bone cyst treatment. Journal of Children's Orthopaedics. 2011;5(2):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s11832-010-0323-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]