Abstract

A method for the rapid screening of drugs targeting the bioenergetic metabolism of Leishmania spp. was developed. The system is based on the monitoring of changes in the intracellular ATP levels of Leishmania donovani promastigotes that occur in vivo, as assessed by the luminescence produced by parasites transfected with a cytoplasmic form of Phothinus pyralis luciferase and incubated with free-membrane permeable d-luciferin analogue d-luciferin–[1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester]. A significant correlation was obtained between the rapid inhibition of luminescence with parasite proliferation and the dissipation of changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) produced by buparvaquone or plumbagin, two leishmanicidal inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation. To further validate this test, a screen of 14 standard leishmanicidal drugs, using a 50 μM cutoff, was carried out. Despite its semiquantitative properties and restriction to the promastigote stage, this test compares favorably with other bioenergetic parameters with respect to time and cell number requirements for the screening of drugs that affect mitochondrial activity.

Parasitic protozoa from the genus Leishmania are the causative agents for the variety of clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis, a disease with an annual incidence of 2 million people worldwide according to the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/emc/diseases/leish/leisdisl.html). Treatment currently relies exclusively on chemotherapy. The development of both new drugs and fast low-cost tests for their screening are required due to the growing incidence of drug resistance against both first-line and alternative drugs (12), together with their frequent severe side effects.

When compared with drug screens available for most microorganisms, Leishmania proliferation assays are frequently time-consuming procedures; hence, definitions of other vital parameters to speed up this process are needed.

ATP levels define the energetic state of Leishmania spp. Oxidative phosphorylation is essential to fulfill the minimal energetic requirements of the parasite (1, 22). Hence, drugs affecting mitochondrial ATP production, such as licochalcones or naphthoquinones, are potentially good leishmanicidal candidates (6, 7, 25). A decrease of the intracellular ATP is induced by these drugs since glycolysis is unable to fully counterbalance this decrease.

Nevertheless, ATP measurement by the standard luciferin-luciferase luminescence assay (9) is a time- and material-consuming method, which is also difficult to automate. Techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance, also enable an examination of ATP variation in vivo, but a high number of cells and sophisticated equipment is required.

As an alternative approach, we have optimized a fast and easy luminescent method involving a technique to bypass the poor permeability of d-luciferin at neutral pH (5, 24) by the use of d-luciferin–[1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester] (DMNPE-luciferin), a caged membrane-permeable luciferin ester, and promastigotes transfected with a firefly luciferase gene mutated in its C-terminal tripeptide sequence, disabling its intracellular transport into the glycosomes (21) and retaining the enzyme inside the cytoplasm.

In order to validate the system, the inhibition of luminescence by a set of drugs affecting mitochondrial physiology was compared with their effects on mitochondrial membrane potential and promastigote proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the expression vector pX63NEO-3Luc.

Phothinus pyralis luciferase gene (luc) with a mutation in the last three amino acids was a kind gift from T. Aesbicher and I. Vorberg (Max Planck Institut für Biologie, Tübingen, Germany) (21). The luciferase gene was inserted at the BamHI restriction site of the polylinker of the Leishmania expression vector pX63NEO (17). Insert orientation was checked by electrophoretic analysis of the resulting fragments after digestion with BglII and Asp718. The plasmid was purified using QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and its purity was assessed by agarose electrophoresis.

Parasites.

Leishmania donovani promastigotes (MHOM/SD/00/1S-2D), kindly provided by S. Turco, Kentucky University, were transfected with pX63NEO-3Luc containing the luciferase mutated gene, either in the right (3-Luc strain) or the reversed (Neo strain) orientation by electroporation, according to the method of Lebowitz (16). Parasites were selected by growth in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 24 mM NaHCO3, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM d-glutamine, 100 U of uniciline per ml, 48 mg of gentamicin per ml, and 30 μg of geneticin (G-418; Gibco) per ml (RPMI-HIFCS) at pH 7.2, a medium which was also used for parasite maintenance.

Promastigotes were harvested at late exponential phase and washed twice in Hanks buffer supplemented with 10 mM d-glucose (pH 7.2) at 4°C (Hanks-Glc).

Drugs.

A total of 14 drugs, summarized in Table 1, were tested. Buparvaquone, plumbagin, and lawsone, all naphthoquinone derivatives were used as positive controls (6, 7, 19), while the other compounds were tested blind. Drug concentrations are stated in the corresponding tables and figures. Controls used the same amount of the corresponding solvent.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the drug effect on some viability parameters of 3-Luc L. donovani promastigotes

| Drug | ED50 (μM) (95% CI)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminescence | Proliferation | ΔΨm | |

| Buparvaquone | 0.04 (0.07–0.02) | 0.03 (0.04–0.02) | 0.05 (0.07–0.04) |

| Plumbagin | 1.15 (1.15–0.8) | 2.99 (7.1–1.26) | 1.79 (2.2–1.4) |

| 1–4 Naphthoquinone | 1.12 (1.4–0.9) | 0.82 (0.92–0.73) | 0.23 (0.4–0.1) |

| Pyronaridine | 2.3 (4.35–1.2) | 0.7 (1.12–0.43) | 2.9 (3.6–2.3) |

| Juglone | 0.43 (0.51–0.36) | 0.59 (1.56–0.22) | 0.39 (1.5–0.07) |

| Menadione | 8.38 (11.1–6.3) | 6.74 (11.41–3.9) | 4.82 (6.1–3.8) |

| Lawsone | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| Lapachol | >50 | >50 | |

| Mepacrineb | >50 | 0.84 (0.99–0.7) | |

| Mepacrinec | 17.5 (25.3–12.1) | ||

| Diminazene aceturate | >50 | >50 | |

| Nifurtimox | >50 | >50 | |

| Atovaquone | >50 | >50 | |

| Meglumine antimoniate | >50 | >50 | |

| Pentamidine | >50 | 0.72 (0.8–0.65) | |

ED50 values were estimated by the Litchfield and Wilcoxon procedure. The 95% confidence interval (CI) values are included in parentheses. Assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods.

The luminescence assay was done according to the standard protocol.

The promastigotes were preincubated 4 h prior to the luminescence assay.

Estimation of luciferase expression levels in transfected Leishmania promastigotes.

The Luciferase Assay System Kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was used according to the directions of the supplier. Luminescence was measured in an LKB Bio-Orbit 1250 luminometer at 1 and at 3 min after mixing. The optimal range of parasites was 105 promastigotes per assay. Luminescence from lysates was compared with a standard purified P. pyralis luciferase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Barcelona, Spain) mixed with the same amount of cell lysate from the Neo strain.

Setup of standard bioluminescence assay.

Stock solutions (5 mM) of both d-luciferin and its caged analogue DMNPE-luciferin (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) were made in dimethyl sulfoxide. The substrate was added to a promastigote suspension (2 × 107 cells/ml) in Hanks-Glc at a final concentration of 25 μM (final volume, 200 μl). After mixing, luminescence was monitored in an LKB Bio-Orbit 1250 luminometer, averaging the luminescence values every 10 s. Drugs were added when luminescence reached a plateau; this point was considered time zero, and its luminescence level was taken as 100%. In a set of initial experiments, metabolic inhibition of parasites by 2 mM KCN and/or 10 mM 2-d-deoxyglucose (2-dGlc) was carried out following of promastigotes for 4 h in Hanks solution plus 2 mM d-Glc.

Oxygen consumption rates.

Oxygen consumption rates were measured in a Clarke oxygen electrode (Hansatech, KingsLynn, United Kingdom) at 25°C as described earlier (9) using 0.8 ml of a parasite suspension (108 cells/ml).

Evaluation of ΔΨm.

The change in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) in intact promastigotes was estimated by measuring rhodamine-123 (Molecular Probes) accumulation (9). Parasites (2 × 106 promastigotes/ml) were resuspended in Hanks-Glc and incubated with the different drugs for 30 min at 25°C. After that, parasites were loaded with rhodamine-123 (0.3 μg/ml, 5 min, 37°C), washed by centrifugation, and resuspended in Hanks-Glc at a final density of 106 cells/ml. Drug accumulation was tested immediately in a Coulter XL EPICS cytofluorometer (excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 525 nm, respectively). Depolarized parasites, incubated with 7.5 μM carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) or 2 mM KCN were considered as negative controls.

Cell proliferation measurements.

Parasites were resuspended in growth medium (RPMI-HIFCS) devoid of phenol red at a final density of 2 × 106 promastigotes/ml, divided into aliquots, placed in a 96-well culture microplate (100 μl/well), and incubated with drugs for 48 h at 25°C. After that, an equal volume of (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (MTT) solution (1 mg/ml) in Hanks-Glc was added to each well, and the wells were incubated for 2 h at 25°C. Precipitated formazan was solubilized by the addition of 100 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate solution and read in a 450 Bio-Rad microplate reader equipped with a 600-nm filter. For those drugs affecting MTT reduction, proliferation was measured by cell counting in a Neubauer chamber. Only full motile promastigotes were considered viable (9).

Measurement of ATP.

ATP was extracted by the addition of 100 μl of 0.9 M HCl to promastigotes previously incubated with 25 μM DMNPE-luciferin for 30 min. The supernatant was neutralized by the addition of 40 μl of 0.8 M Na2AsO4H and 9 μl of 0.4 M NaOH. Then, 50 μl of this solution was added to 200 μl of a firefly lantern extract reagent (Sigma) and 750 μl of H2O. Luminescence was read at 1 and 3 min after the components were mixed and then compared with a standard ATP curve (9).

Statistical analysis.

Data represent the mean of triplicate samples ± the standard deviation. The 50% effective dose (ED50) values were calculated by the Litchfield and Wilcoxon procedure and the 95% confidence interval is included in parentheses. Comparison among different methods was carried out by the Pearson χ2 test, and a significance level of 0.01 (α = 0.01) was taken.

RESULTS

Optimization of the bioluminescence assay.

The levels of luciferase in transfected promastigotes were estimated by enzymatic activity as (2.52 ± 0.27) × 103 copies/promastigote. This value is 10 times higher than that obtained for the native glycosomal form of the enzyme (data not shown).

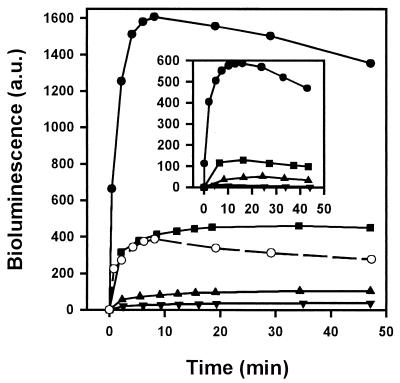

Both free d-luciferin and its neutral ester (DMNPE-luciferin) were compared as luminescence substrates (Fig. 1). Upon addition of the substrate, the luminescence increased rapidly and dependent on substrate concentration between 2.5 and 25 μM. At 25 μM the luminescence obtained with DMNPE-luciferin was approximately four times higher than that with d-luciferin (Fig. 1). The maximum level was reached ca. 10 min after DMNPE-luciferin addition, followed by slow decay for at least 1 h.

FIG. 1.

Optimization of luminescence assay on luciferase-transfected L. donovani promastigotes. A comparison of d-luciferin and DMNPE-luciferin as substrates for bioluminescence is shown. Results for DMNPE-luciferin at 2.5 (▾), 5 (▴), 12.5 (■), and 25 (●) μM and d-luciferin at 25 μM (○) are indicated. The inset shows the variation of luminescence with respect to the parasite number. Results are shown for cell numbers of 0.25 × 106 (▾), 0.50 × 106 (▴), 1.0 × 106 (■), and 4.0 × 106 (●). The same units were used for both the main and the inset graphic axes. The assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. a.u., arbitrary units.

When assayed at 25 μM DMNPE-luciferin, luminescence was directly proportional to the cell number (Fig. 1, inset). Luciferase activity depleted total ATP content by only 3.8% ± 1.5% from its initial value of 15 nmol/mg of protein (1 mg of protein = 3.6 × 108 promastigotes).

Treatment of parasites with 10 mM 2-dGlc (a competitive inhibitor of glycolysis) or with 2 mM KCN (as inhibitor of the respiratory chain) led to luminescence decreases of 22 and 85%, respectively, and to a decrease of 97% when these inhibitors were added together.

Effects of naphthoquinones on promastigote bioluminescence and other viability parameters.

To remove false negatives caused by a direct inhibition of luciferase, drugs were tested in vitro at their highest concentration on purified luciferase. None of the drugs produced a significant in vitro inhibition (>5%).

Buparvaquone and plumbagin inhibited parasite luminescence in vivo at nanomolar and micromolar concentrations (Table 1) but not the natural hydroxynaphthoquinone lawsone, reported previously as inactive (1, 19).

A good correlation was obtained for the ED50 of buparvaquone (an inhibitor of respiratory chain) and plumbagin (uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation) for parasite proliferation, ΔΨm, and luminescence (Table 1). Lawsone was inactive in the three systems (ED50 >50 μM) (Table 1).

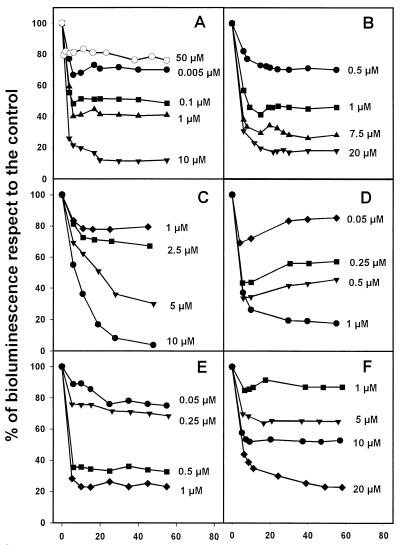

Validation of the luminescence test with other drugs.

A set of 14 drugs was assayed blind in the luminescence assay using an initial cutoff of 50 μM. In these tests only six compounds inhibited luminescence (Fig. 2). Plumbagin, 1-4 naphthoquinone, pyronaridine, and menadione were active as inhibitors of luminescence at a micromolar concentration, whereas buparvaquone and juglone were active at a nanomolar concentration range. As above, a good correlation between luminescence decrease with the other two parameters was obtained (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Dose-dependent decrease of luminescence in 3-Luc L. donovani promastigotes (in the presence of DMNPE-luciferin). (A) Buparvaquone (solid symbols) and lawsone (empty circle). (B) Plumbagin. (C) Pyronaridine. (D) Juglone. (E) 1-4 Naphthoquinone. (F) Menadione.

When the same set of drugs was tested for inhibition of promastigote proliferation, another two drugs (mepacrine and pentamidine), inactive at 50 μM by the standard luminescence test, were highly inhibitory (Table 1). Nevertheless, either when the pentamidine concentration was increased to 100 μM or when the parasites were preincubated with 50 μM mepacrine for 4 h prior to DMNPE-luciferin addition, the luminescence levels were decreased to 25.5% ± 7.8% and 28.2% ± 4.3%, respectively, compared to the control parasites. This result suggested a slow accumulation of mepacrine, confirmed by the decrease in the oxygen consumption rates of parasites permeabilized with digitonin, making mitochondria accessible to the drug. The control rate for intact parasites (8.45 nmol O2 × min−1 × [108 cells]−1) was not modified at 10 μM mepacrine, whereas in permeabilized parasites a decrease of 26.5% was observed at this concentration.

DISCUSSION

Microorganisms transfected with P. pyralis luciferase have been extensively used to improve proliferation assays in slow-dividing organisms, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (13, 20, 33). However, the potential of using the internal expression of luciferase as a probe to monitor in vivo changes in metabolism affecting intracellular ATP levels have not been fully explored in higher eukaryotes (15) or parasitic protozoa.

This is due to the substrate limitation caused by the poor membrane permeability of d-luciferin at neutral pH and sequestration of luciferase into peroxisomes. We have improved the system and applied it to screen leishmanicidal drugs in a fast- and cost-effective manner by using a free-membrane permeable neutral caged luciferin ester, hydrolyzed once inside the cytoplasm (5, 24), and parasites transfected with a mutated version of the P. pyralis luciferase gene that retained the enzyme in the cytoplasm (21), with a much better yield in luminescence than the native glycosomal form of the enzyme.

Luminescence output is proportional to both the luciferase substrate concentration and the cell number. According to our measurements of total ATP levels, the slow decay observed after the maximum is not produced by ATP depletion by the luminescence reaction but is more likely caused by luciferase inhibition by the end products of d-luciferin (8).

The standard protocol is biased toward the identification of drugs affecting mitochondrial ATP production rather than inhibitors of glycolysis. This is in agreement with our results on luminescence inhibition by KCN and 2-dGlc, with the correlation between the ED50 for luminescence and ΔΨm, and with previous reports in the literature (1, 22), where minimal energetic requirements can only be fulfilled by oxidative phosphorylation and not by glycolysis. Putative inhibitors of the last pathway would be identified indirectly through the depletion of pyruvate, provided that d-glucose was the sole source of carbon and that all the other metabolic intermediates from glycolysis or the Krebs cycle or the internal carbohydrate reservoirs have undergone a strong depletion.

Inhibition of luminescence correlated well (α = 0.01) with the leishmanicidal activity of naphthoquinones and hydroxynaphthoquinones (6, 7, 14, 19). Atovaquone and meglumine antimoniate were not detected since they mainly affect the amastigote stage (7, 17). In general, the inhibition of proliferation was always higher than the inhibition of luminescence at the same drug concentration. A likely explanation for this is that the loss of parasite viability will require a significant but not total depletion of ATP levels, as seen in similar experiments with rat hepatocytes (15).

The luminescence assay failed to detect two known leishmanicidal drugs, pentamidine and mepacrine. Mepacrine was described as an inhibitor of topoisomerase II and protein synthesis (11) rather than as a fast effector on the energetic metabolism of the parasite. Even so, luminescence is affected after longer incubation with mepacrine, possibly by an indirect pathway. Pentamidine was reported as an inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis and kDNA replication (2); however, it also inhibits oxidative phosphorylation on Leishmania promastigotes in digitonin-permeabilized parasites at 200 μM (23), a concentration four times higher than our 50 μM cutoff. In fact, 100 μM pentamidine inhibited luminescence in agreement with this earlier study.

The assay can also uncover effects on bioenergetic metabolism as a putative secondary target for drugs. Pyronaridine, reported to be a DNA polymerase II inhibitor in Plasmodium falciparum (4), produced a considerable inhibition of luminescence, and a possible inhibition on luciferase was excluded by in vitro assays on parasite lysates. This is also confirmed by the good correlation obtained in our assay with bioenergetic parameters directly related to ATP production in mitochondria, such as the membrane potential ΔΨm.

An intrinsic limitation of the method is its restriction to the promastigote, the only stage where the expression of genes inserted into the pX63NEO vector reached good levels (17). Since new expression vectors for amastigotes are being improved (3), this strategy should be explored further. However, assays in infected macrophages will be limited by the access of d-luciferin into the parasitophorus vacuole. The system has advantages over other methods since it requires a lower number of cells than that required for measuring oxygen consumption rate and since it is less time-consuming than measurement of the ΔΨm. This assay is also simple and easy to automate. Although initially designed for fast-acting drugs affecting ATP production, its utility can be extended to the slow-accumulating drugs, as previously discussed, and for other compounds that cause the reduction of ATP levels, such as membrane-active molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (99/0025-02), the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid Programa General de Grupos Estratégicos, and grants 08-2/0029.2, and EU IC 18-CT97-0213 to L.R. and from Sir Halley Stewart Trust to S.L.C.

The statistical processing of data by Benito Muñoz (Facultad de Biología, Universidad Complutense de Madrid) is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez-Fortes E, Ruiz-Pérez L M, Bouillaud F, Rial E, Rivas L. Expression and regulation of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 from brown adipose tissue in Leishmania major promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;93:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basselin M, Badet-Denisot M A, Robert-Gero M. Modification of kinetoplast DNA minicircle composition in pentamidine-resistant Leishmania. Acta Trop. 1998;70:43–61. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(98)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charest H, Zhang W W, Matlashewski G. The developmental expression of Leishmania donovani A2 amastigote-specific genes in posttranscriptionally mediated and involves elements located in the 3′-untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17081–17090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chavalitshewinkoon P, Wilairat P, Gamage S, Denny W, Figgitt D, Ralph R. Structure-activity relationships and modes of action of 9-anilinoacridines against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:403–406. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig F F, Simmonds A C, Watmore D, McCapra F. Membrane-permeable luciferin esters for assay of firefly luciferase in live intact cells. Biochem J. 1991;276:637–641. doi: 10.1042/bj2760637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft S L, Evans A T, Neal R A. The activity of plumbagin and other electron carriers against Leishmania donovani and Leishmania mexicana amazonensis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1985;79:651–653. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1985.11811974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croft S L, Hogg J, Gutteridge W E, Hudson A T, Randall A W. The activity of hidroxynaphthoquinones against Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30:827–832. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLuca M. Firefly luciferase. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1976;44:37–68. doi: 10.1002/9780470122891.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díaz-Achirica P, Guinea A, Ubach J, Andreu D, Rivas L. The plasma membrane from Leishmania donovani promastigotes is the main target for CA(1–8)M(1–18), a synthetic cecropin A-melittin hybrid. Biochem J. 1998;330:453–460. doi: 10.1042/bj3300453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ephros M, Bitnun A, Shaked P, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. Stage-specific activity of pentavalent antimony against Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:278–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamage S A, Figgitt D P, Wojcik S J, Ralph R K, Ransijn A, Mauel J, Yardley V, Snowdon D, Croft S L, Denny W A. Structure-activity relationships for the antileishmanial and antitrypanosomal activities of 1′-substituted 9-anilinoacridines. J Med Chem. 1997;40:2634–2642. doi: 10.1021/jm970232h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herwaldt B L. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickey M J, Arain T M, Shawar R M, Humble D J, Langhorne M H, Morgenroth J N, Stover C K. Luciferase in vivo expression technology: use of recombinant mycobacterial reporter strains to evaluate antimycobacterial activity in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:400–407. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson A T, Randall A W, Fry M, Ginger C D, Hill B, Latter V S, McHardy N, Williams R B. Novel anti-malarial hydroxynaphthoquinones with potent broad spectrum anti-protozoal activity. Parasitology. 1985;90:45–55. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000049003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koop A, Cobbold H. Continuous bioluminescent monitoring of cytoplasmic ATP in single isolated rat hepatocytes during metabolic poisoning. Biochem J. 1993;295:165–170. doi: 10.1042/bj2950165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebowitz J H. Transfection experiments with Leishmania. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;45:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61846-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lebowitz J H, Coburn C M, McMahon-Pratt D, Beverley S M. Development of a stable Leishmania expression vector and application to the study of parasite surface antigen genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9736–9740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson L E, Hoffner S E, Ånséhn S. Rapid susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by bioluminescence assay of mycobacterial ATP. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1208–1212. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinto A V, Pinto C N, Pinto M do C, Rita R S, Pezzella C A, de Castro S L. Trypanocidal activity of synthetic heterocyclic derivates of active quinones from Tabebuia sp. Arzneimittelforschung. 1997;47:74–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shawar R M, Humble D J, Van Dalfsen J M, Stover C K, Hickey M J, Steele S, Mitscher L A, Baker W. Rapid screening of natural products for antimycobacterial activity by using luciferase-expressing strains of Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium intracellulare. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:570–574. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommer J M, Cheng Q L, Keller G A, Wang C C. In vivo import of firefly luciferase into the glycosomes of Trypanosoma brucei and mutational analysis of the C-terminal targeting signal. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:749–759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Hellemond J J, Van der Meer P, Tielens A G M. Leishmania infantum promastigotes have a poor capacity for anaerobic functioning and depend mainly on respiration for their energy generation. Parasitology. 1997;114:351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vercesi A E, Docampo R. Ca2+ transport by digitonin-permeabilized Leishmania donovani. Effects of Ca2+, pentamidine and WR-6026 on mitochondrial membrane potential in situ. Biochem J. 1992;284:463–467. doi: 10.1042/bj2840463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Thomason D B. An easily synthesized, photolyzable luciferase substrate for in vivo luciferase activity measurement. BioTechniques. 1993;15:848–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhai L, Blom J, Chen M, Christensen S B, Kharazmi A. The antileishmanial agent licochalcone A interferes with the function of parasite mitochondria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2742–2748. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]