Abstract

Background & Aims

Single-cell transcriptomics offer unprecedented resolution of tissue function at the cellular level, yet studies analyzing healthy adult human small intestine and colon are sparse. Here, we present single-cell transcriptomics covering the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and ascending, transverse, and descending colon from 3 human beings.

Methods

A total of 12,590 single epithelial cells from 3 independently processed organ donors were evaluated for organ-specific lineage biomarkers, differentially regulated genes, receptors, and drug targets. Analyses focused on intrinsic cell properties and their capacity for response to extrinsic signals along the gut axis across different human beings.

Results

Cells were assigned to 25 epithelial lineage clusters. Multiple accepted intestinal stem cell markers do not specifically mark all human intestinal stem cells. Lysozyme expression is not unique to human Paneth cells, and Paneth cells lack expression of expected niche factors. Bestrophin 4 (BEST4)+ cells express Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and show maturational differences between the small intestine and colon. Tuft cells possess a broad ability to interact with the innate and adaptive immune systems through previously unreported receptors. Some classes of mucins, hormones, cell junctions, and nutrient absorption genes show unappreciated regional expression differences across lineages. The differential expression of receptors and drug targets across lineages show biological variation and the potential for variegated responses.

Conclusions

Our study identifies novel lineage marker genes, covers regional differences, shows important differences between mouse and human gut epithelium, and reveals insight into how the epithelium responds to the environment and drugs. This comprehensive cell atlas of the healthy adult human intestinal epithelium resolves likely functional differences across anatomic regions along the gastrointestinal tract and advances our understanding of human intestinal physiology.

Keywords: scRNAseq, Cell Atlas, Intestinal Stem Cell, Paneth Cell, BEST4

Abbreviations used in this paper: AC, ascending colon; ACC, absorptive colonocyte; AE, absorptive enterocyte; BEST4+, Bestrophin 4; DC, descending colon; DEG, differentially expressed genes; dPBS, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline; EEC, enteroendocrine cell; FAE, follicle-associated epithelium; GC, goblet cell; GI, gastrointestinal; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; icGC, intercrypt goblet cell; IL, interleukin; ISC, intestinal stem cell; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; M-cell, microfold cell; mRNA, messenger RNA; PAGA, partition-based graph abstraction; PC, Paneth cell; scRNAseq, single-cell RNA sequencing; SI, small intestine; TA, transit amplifying; TC, transverse colon

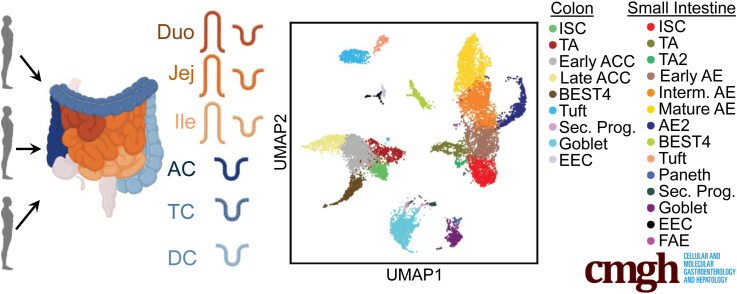

Graphical abstract

Summary.

We present a single-cell transcriptomic atlas of epithelial cells from the duodenum to descending colon using 3 intact healthy adult organs. Thorough analyses provide differentially expressed/functional genes, regional differences, murine model comparisons, and gene sets highlighting potential receptor-ligand and drug-target interactions

Colloquially called the gut, the small intestine (SI) and colon are distinct organs with overlapping and unique roles in maintaining health. The gut lumen is lined by epithelial stem and differentiated cells that renew weekly.1 Cellular roles include absorption, ion balance, hormone production, mucus production, and signaling through the luminal–epithelial–immune axis. Although physiological functions vary along the gut, how lineages differ across the SI–colon axis is poorly understood.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) approaches have provided unprecedented transcriptomic resolution of cells and have shown unappreciated cellular heterogeneity. Human intestinal scRNAseq studies often analyze individual regions, with studies on adult colonic,2, 3, 4, 5 ileal,6, 7, 8 and duodenal9 epithelium available. One study compared adult human ileum and regionally unspecified colon,6 and a recent report compiled a regional mosaic using multiple donor samples yet had few donors for some regions and provided a limited epithelial analysis.10 Several human gut regions have sparse scRNAseq analysis available, with no scRNAseq studies analyzing differences among regions within the human SI or colon.

Here, we comprehensively survey adult human gut epithelium using transplant-grade organs. scRNAseq libraries were prepared from epithelial cells from duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and ascending (AC), transverse (TC), and descending (DC) colon from 3 donors. This experimental design provides a robust library that avoids intradonor batch effects and allows comparisons between all 6 regions across the same 3 individual patients. Using this data set, we probe understudied human lineages including Paneth cells (PCs), Bestrophin 4 (BEST4)+ cells, and follicle-associated epithelium (FAE). We define comprehensive transcriptional signatures for lineages along the entire gut and generate regional atlases of functional gene families. We further probe how lineages might be affected by extrinsic signaling through mapping receptor families and analyzing primary gene targets of approved drugs.

Results

Sample Processing

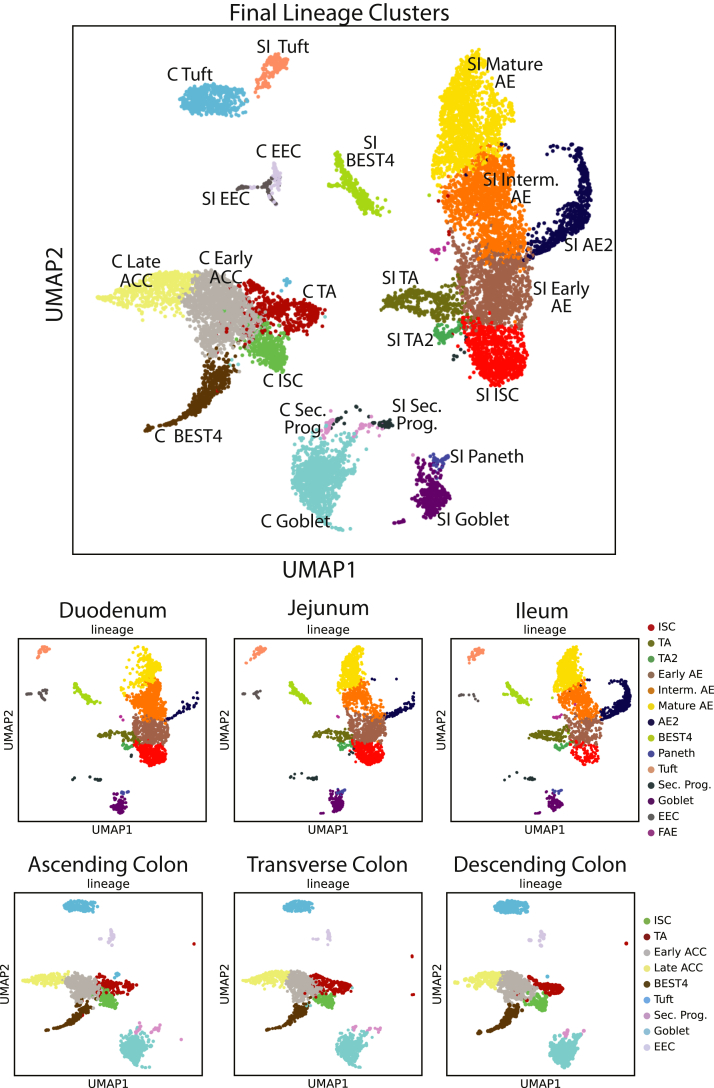

We define SI and colon as organs, and duodenum, jejunum, ileum, AC, TC, and DC as regions. Intestinal tracts were obtained from 3 disease-free organ donors (Figures 1A and 2), with a pathologist verifying healthy mucosa. Epithelium from each region was dissociated to single cells using cold protease to preserve RNA integrity and cells were flow-sorted to exclude dead cells and doublets before sequencing. Cells from each region were stained with cell hashtag antibody-oligo conjugates11,12 to multiplex regions for library preparation and sequencing, then cells from all regions per donor were sorted concurrently to avoid intradonor batch effects and reduce cost. Readouts were filtered for minimum and maximum total counts and maximum mitochondrial gene reads to exclude transcriptomes of low-read count cells, multiplets, and likely dead cells, respectively. Hashtag deconvolution allowed for more stringent filtering against clusters and contaminating messenger RNA (mRNA) than available in other studies, with cells positive for multiple hashtags removed to filter out likely multiplets or cells contaminated with RNA from other cells. After filtering, transcriptional readouts for 12,590 total cells were obtained (Figure 2), with consistent read depth (11,378 reads per cell) and gene counts (2851 genes per cell) seen across regions.

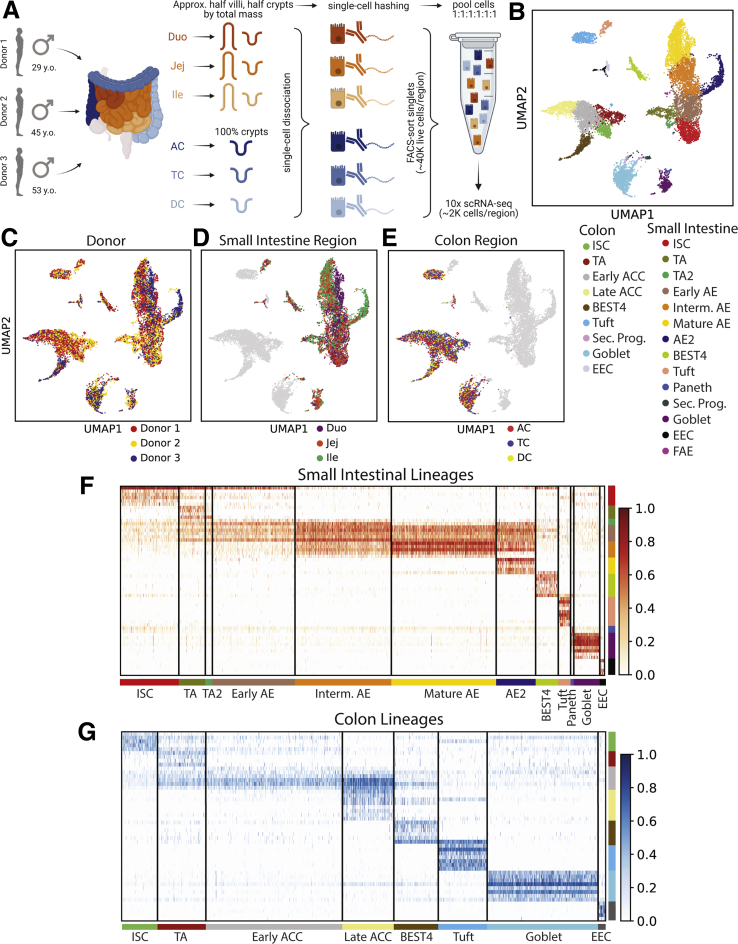

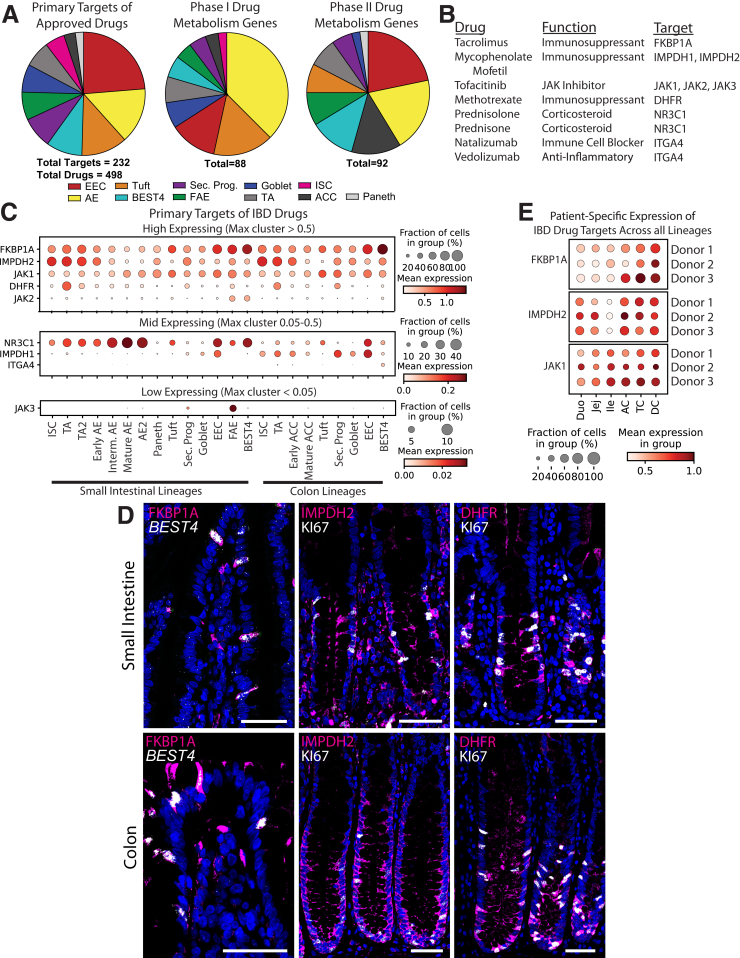

Figure 1.

Sample processing. (A) Schematic for isolating single epithelial cells from 6 intestinal regions for 3 donors and then using hashtag antibodies to sequence cells from all regions side-by-side. (B) UMAP of all analyzed cells in 25 lineage clusters. See Figure 19 for clearly marked clusters. (C–E) UMAP of all cells colored by (C) donor or (D and E) region. (F and G) Heatmaps showing unique markers for major lineages in (F) SI and (G) colon. See Supplementary Table 1 for total DEGs for each lineage. Schematics in panel A were created with BioRender.com. Duo, Duodenum; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; Ile, Ileum; Interm, intermediate; Jej,Jejunum; Sec. Prog., Secretory Progenitor; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

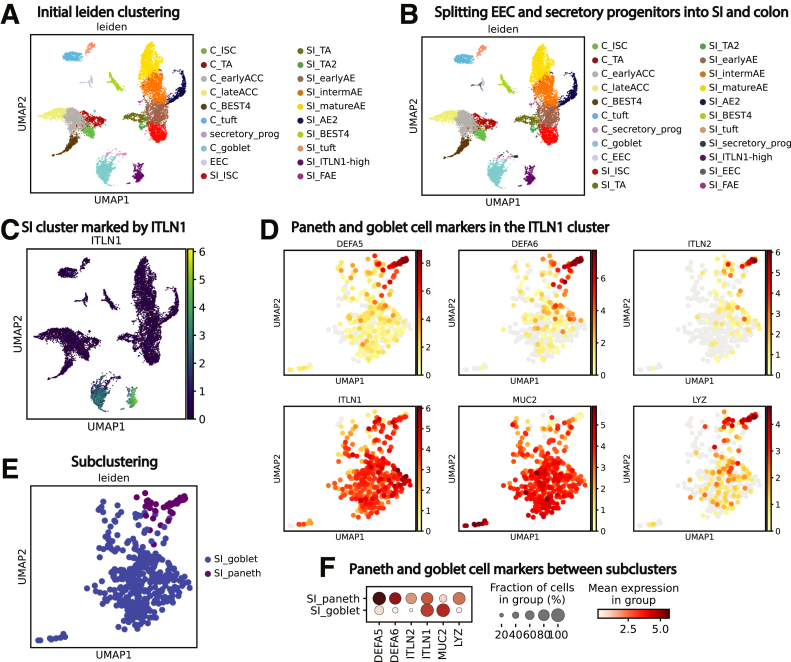

Figure 2.

Patient characteristics and cell counts. (A) Donor information. (B) Cells collected per donor region. (C) Small intestinal lineages collected per donor. (D) Colonic lineages collected per donor. (E) Small intestinal lineages per donor region. (F) Colonic lineages per donor region. Abs., Absorptive; Asc., Ascending; BMI, body mass index; Desc., Descending; Trans., Transverse.

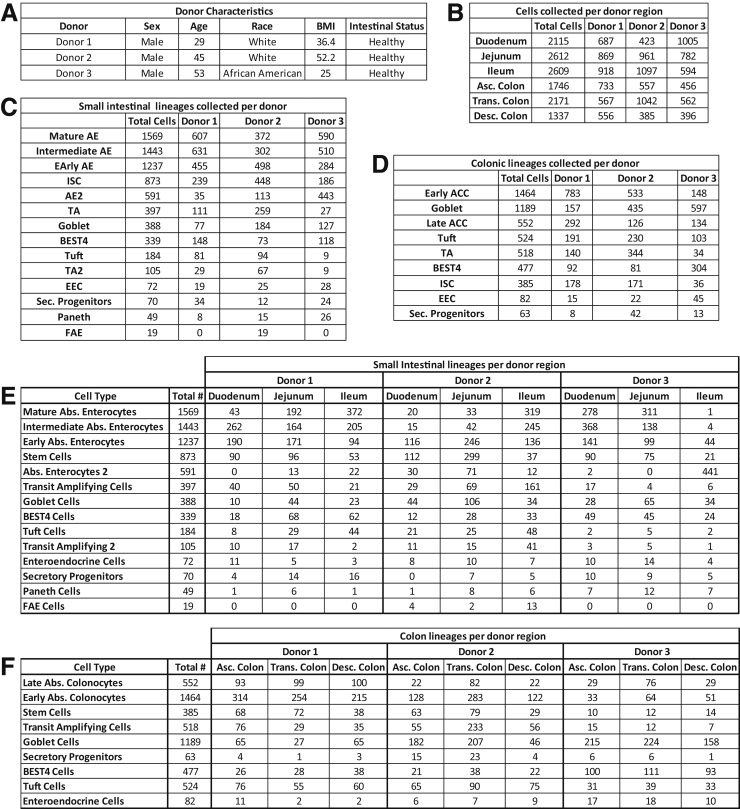

Donor data sets were individually processed and then combined. Principal components were integrated with Harmony13 before dimensional reduction and Leiden clustering.14 Most lineages formed SI- and colon-specific clusters, suggesting functional differences between organs. One cluster expressed PC and goblet cell (GC) markers, so subclustering resolved these lineages (Figure 3). Our final data set identifies all lineages by organ (Figure 1B). The integrated data set shows overlapping cell distributions from each donor and region within all major lineages, showing that postsequencing hashtag deconvolution preserves transcriptomic features across batches (Figure 1C–E). Cell counts for each region show that all 3 donors contributed approximately one third (33%) of the total cells analyzed for each region and no individual donor provided the majority of cells for any specific region, with each donor providing 20%–48% of the total cells for every region (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Determining final lineage clusters. (A) Initial Leiden clustering for all cells. (B) Splitting EEC and secretory progenitors by organ. (C and D) An ITLN1-high cluster, all from SI, contains cells expressing PC markers (DEFA5, DEFA6, ITLN2, LYZ) along with cells expressing the GC marker MUC2. (C) cluster defined by ITLN1; (D) UMAP expression of PC and GC markers within the ITLN1-high cluster. (E) Subclustering to define Paneth and Goblet cells. (F) Dotplot showing expression of classic PC and GC genes across the new PC and GC clusters. UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

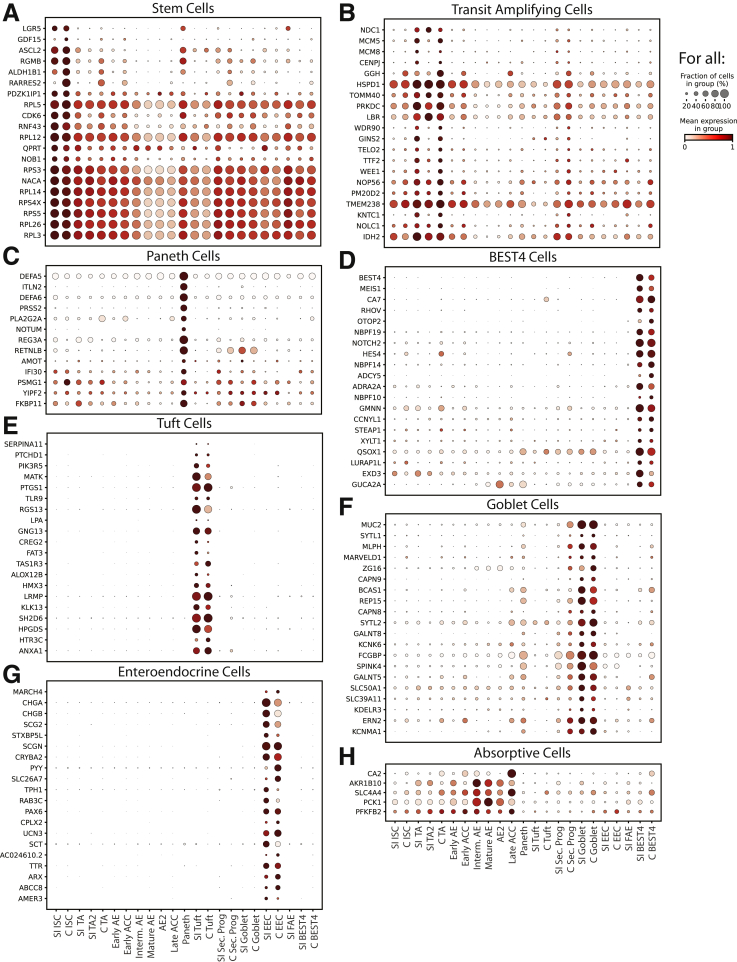

To define transcriptional signatures for each lineage, we calculated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in both organs for each lineage (Supplementary Table 1). We also identified DEGs consistently enriched across all 6 regions and in all 3 donors, defining DEGs that are lineage-specific regardless of position in the SI or colon (Supplementary Table 2). This statistical evaluation provides previously unavailable transcriptional signatures for all lineages across the human SI and colon epithelium (Figure 1F and G).

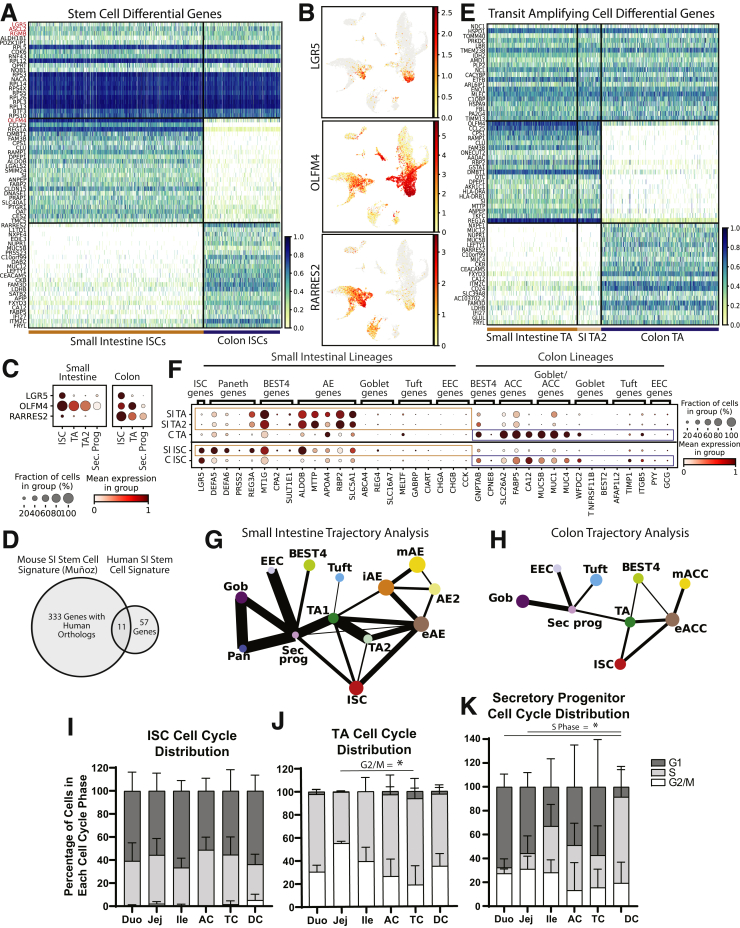

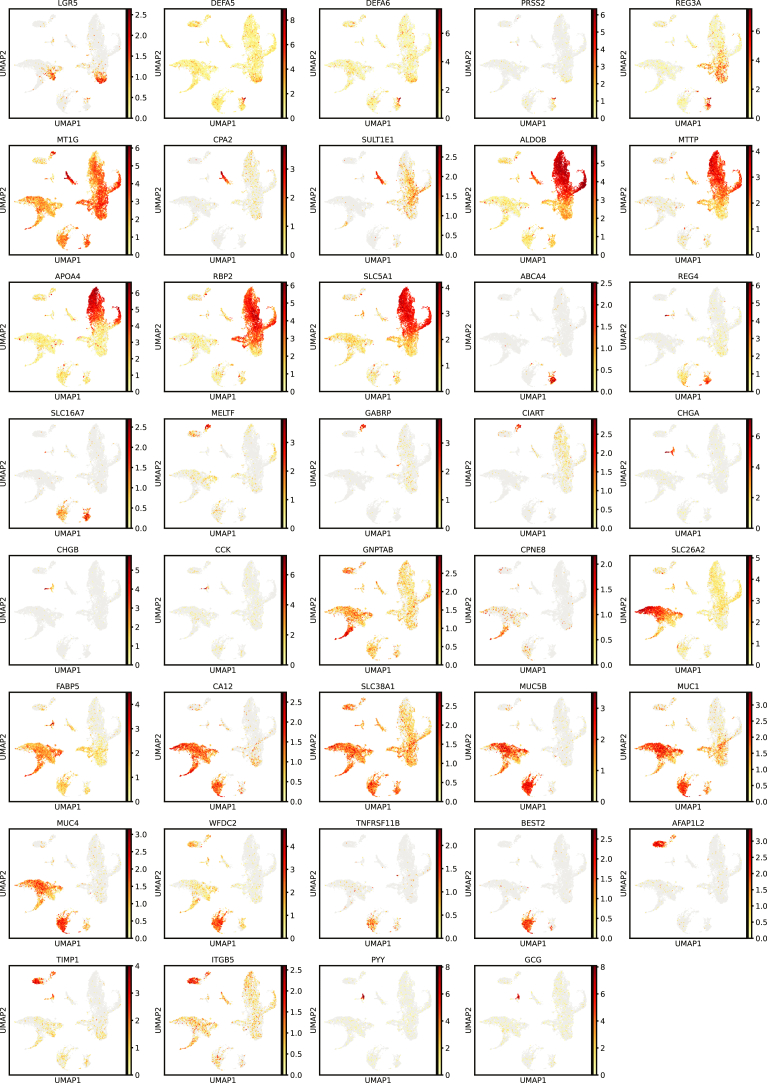

Proliferative Cells

We found that human intestinal stem cells (ISCs) significantly expressed classic markers LGR5, ASCL2, SLC12A2, and RGMB (Figure 4A and B).15, 16, 17 SMOC218 was not a DEG in SI ISCs because PCs unexpectedly were found to express it at higher levels (see Paneth Cell section). Although in situ hybridization was used in a previous report that concluded that OLFM4 marks human colonic ISCs,19 our results showed colonic OLFM4 levels were higher in transit-amplifying (TA) cells (Figure 4C), consistent with mouse studies.16 RARRES2, a retinoid-response gene with no reported association to the gut epithelium, was enriched in colon ISCs, with low SI ISC expression (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Proliferative crypt populations. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in ISCs vs other lineages (top; red: classic markers), SI vs colon ISCs (middle), and colon vs SI ISCs (bottom). (B) UMAP of LGR5, OLFM4, and RARRES2 expression. (C) Dotplot showing expression of LGR5, OLFM4, and RARRES2 across proliferative lineages of the SI (left) and colon (right). (D) Venn diagram showing overlap between our human ISC signature and a previously described murine signature. (E) Heatmap of DEGs in TA cells vs other lineages (top), SI vs colon TA cells (middle), and colon vs SI TA cells (bottom). (F) Dotplot showing DEGs defined in SI- or colon-specific mature lineages expressing within organ-delineated ISCs and TA cells. (G and H) PAGA showing connectivity between major lineages in (G) SI and (H) colon to infer the maturation trajectory. Line thickness represents connectivity strength. (I–K) Regional cell-cycle phase distribution in (I) ISCs, (J) TA cells, and (K) secretory progenitors. C, Colon; Duo, Duodenum; eACC, Early Absorptive Colonocytes; eAE, Early Absorptive Enterocytes; Gob, Goblet; iAE, Intermediate Absorptive Enterocytes; Ile, Ileum; Jej, Jejunum; mACC, Mature Absorptive Colonocytes; mAE, Mature Absorptive Enterocytes; Pan, Paneth; Sec. prog., Secretory Progenitor.

SI ISCs had 68 DEGs compared with other SI clusters, whereas colon ISCs displayed 109 DEGs compared with other colon clusters (Supplementary Table 1, Figure 5). We identified 46 ISC DEGs enriched across both organs, defining an ISC transcriptional signature spanning SI and colon (Supplementary Table 2). This signature includes classic ISC markers and 30 ribosomal genes, consistent with transcriptional regulation by ribosomes shown in other stem cell populations.20, 21, 22 To identify ISC DEGs conserved between human beings and mice, we compared our 68-gene SI ISC signature with a mouse ISC signature defined by bulk RNA sequencing of flow-sorted Leucine Rich Repeat Containing G Protein-Coupled Receptor 5 (Lgr5+) cells.18 Surprisingly, only 11 genes overlapped between the signatures (Figure 4D), although it is unclear whether this reflects species differences or the higher stringency of scRNAseq and computational analysis compared with bulk sequencing of cells sorted using a fluorescent reporter. Conserved genes included classic markers: LGR5, OLFM4, ASCL2, RGMB, SLC12A2, and MYC; genes with known ISC function: RNF43, ZBTB38, VDR, and CDK6; and 1 gene absent in ISC literature: TRIM24. These SI, colon, and full-gut ISC signatures underline key similarities and differences in proximal–distal human ISCs.

Figure 5.

DEG dotplots for each lineage. Dotplots showing expression of top 20 DEGs for each lineage, as sorted by expression fold-change above the cluster with the next highest expression. DEGs included are genes significantly enriched in the lineage in both the SI and colon (if applicable).

Leiden clustering separated SI TA cells undergoing S/G2 cell-cycle phases (TA) and M-phase (TA2) (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). We found that DEGs shared across SI TA, SI TA2, and colon TA cells (Figure 4E) were involved in the cell cycle, mitochondrial biogenesis, and ribosomal RNA processing, consistent with the increased mitochondrial load and translation seen because stem cells differentiate in various systems.20,23, 24, 25 Several organ-specific markers of differentiated lineages (Figure 6) were enriched unexpectedly in their respective SI or colon ISC and TA populations (Figure 4F), hinting that ISCs are transcriptionally primed for organ-specificity instead of existing in a pan-intestinal state. This is consistent with adult rodent SI ISCs producing daughter cells specific to their originating organ when engrafted into alternative sites.26,27 Studies defining region/organ-specific chromatin or transcriptomic differences in human ISCs were not found; thus, these genes may aid in studying early differentiation and chromatin dynamics.

Figure 6.

Organ-specific lineage DEGs. Relating to Figure 4F, UMAPs showing expression of DEGs from mature lineages found to be more highly enriched in SI or colon ISCs and TA cells. UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

Trajectory analyses computationally investigate lineage transitions and have been used previously to describe mouse physiology.28, 29, 30, 31 We used partition-based graph abstraction (PAGA), which analyzes transcriptomic similarity between individual cells in different clusters, to define total connection strength (connectivity) between progenitor and differentiated populations and to infer temporal lineage trajectories.32 As expected, absorptive enterocytes (AEs) and absorptive colonocyte (ACCs) are strongly and almost exclusively connected to ISCs and TA cells,8,33 while PCs, GCs, and enteroendocrine cells (EECs) connect strongly to the secretory progenitor population (Figure 4G and H). Consistent with murine findings, tuft cells connect weakly but exclusively to secretory progenitors in colon but not in SI.34,35 Conversely, SI BEST4+ cells connect weakly but exclusively to secretory progenitors while colonic BEST4+ cells connect strongly to TA cells. Because the strength of a connection depends directly on the number of cells analyzed, future studies that enrich for secretory progenitors and immature but lineage-committed, crypt-base populations are needed to further strengthen these findings.

Predicted regional cell-cycle phase distributions36 were analyzed in proliferative lineages (Figure 4I–K). ISCs showed high G1- and S-phase across regions,6 while highly proliferative TA cells largely existed in the S and G2/M. TC showed lower proportions of TA cells in G2/M than jejunum, reflecting regional differences seen in rodents.34 Secretory progenitors showed increasing S phase proximally to distally and higher G1 proportion than TA cells.

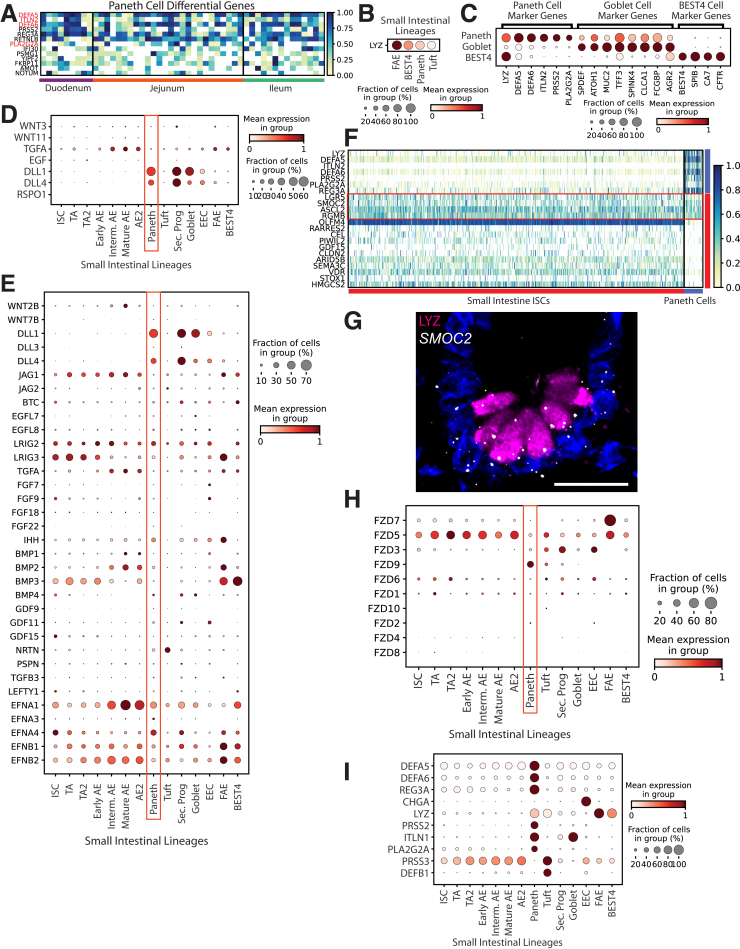

Paneth Cells

Murine PCs play important niche-supporting and antimicrobial roles,37 yet little scRNAseq analysis covers human PCs. Our data include 49 human PCs, 10 times more than analyzed in recent literature.9 PCs were defined using DEFA5, DEFA6, ITLN2, and PLA2G2A (Figure 7A). Because PCs cluster alongside GCs and share LYZ expression with BEST4+ cells, classic markers were plotted to confirm PC identity (Figure 7C). Surprisingly, the murine marker LYZ was not unique to human PCs, with expression also seen in BEST4+ cells and high expression in FAE (Figure 7B). This is consistent with LYZ expression found in fetal human organoids not expected to form PCs.38 Other human intestinal scRNAseq reports also have indicated that LYZ mRNA is not unique to PCs, with 1 report showing that LYZ is not a top PC DEG8 and another showing LYZ as a DEG for M cells,10 consistent with our findings (Figure 7B, Supplementary Table 1). This indicates that although human PCs indeed express LYZ, the presence of this gene product alone is insufficient to determine PC identity or presence. Importantly, our data indicate the cells designated as PCs in a recent scRNAseq publication6 are actually BEST4+ cells because they are marked by high LYZ, SPIB, BEST4, and CA7. Similarly, the colonic Paneth-like cells reported in the study likely also are BEST4+ cells. The rarity of PCs in scRNAseq data (<1% here and elsewhere9), and the presence of LYZ mRNA in other lineages in addition to PCs, highlights the precise lineage attribution needed when defining human PCs.

Figure 7.

Paneth cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in PCs vs other lineages (red: classic markers). (B) Dotplot showing lysozyme mRNA expression across FAE, BEST4, Paneth, and tuft cell lineages. (C) Dotplot showing expression of PC, goblet, and BEST4+ cell classic markers across the PC, goblet, and BEST4+ cell clusters. (D) Dotplot showing growth factors shown to be expressed in murine PCs in previous literature across human SI lineages. (E) Dotplot showing all members of major intestinal growth factor families that show detectable expression in PCs across SI lineages. (F) Heatmap showing PC (top) and ISC markers (bottom) across all SI ISCs (left) and PCs (right). (G) Immunofluorescence staining for LYZ protein (magenta), in situ hybridization showing SMOC2 mRNA (white), and nuclei (blue) in a human ileum crypt base. Maximum projection of eight 0.5-μm optical slices. Scale bar: 20 μm. (H) Dotplot showing expression of all Frizzled family receptors across SI lineages. (I) Dotplot showing the 10 highest-expressed antimicrobial peptides across SI lineages.

Murine PCs express ISC niche factors including Wnt3, Wnt11, Tgfa, Egf, Dll1, Rspo1, and Dll4,29,37,39,40 but 1 report showed human PCs express no WNT3/11.9 Our data confirm this and showed no measurable EGF or RSPO1 and minimal TGFA (Figure 7D). DLL1 and DLL4 are both expressed higher in secretory progenitors (Figure 7D). We found no intestinal growth factors enriched in PCs (Figure 7E), suggesting human PCs are not major niche-supporting cells. This agrees with nonepithelial sources of WNTs and growth factors in the human niche38,41 and echoes mouse biology, where PCs support ISCs37 yet are unnecessary for niche maintenance.37,42, 43, 44

Unexpectedly, SMOC2, a murine ISC marker,18 was expressed highest in PCs, with other markers shown as restricted to ISCs in mouse (LGR5, ASCL2, RGMB) expressed higher in human PCs than expected from the mouse data45 (Figure 7F). Expression of SMOC2 mRNA in human PCs was visualized using in situ hybridization, with obvious overlap seen between SMOC2 and LYZ protein (Figure 7F). ISC-PC doublets could provide a possible explanation for these ISC genes presenting in PCs, yet the lack of many other ISC markers in PCs, notably the nearly complete absence of OLFM4, opposes this hypothesis. LGR5, SMOC2, and ASCL2 function in WNT reception,15,46, 47, 48 suggesting human PCs receive WNT signals instead of providing WNT signals.37 PC unique FZD9 expression further supports a WNT-receptive PC role (Figure 7H).

Despite striking differences between mouse and human PCs, both supply antimicrobial gene products. Six of the 10 highest expressed SI antimicrobial peptides are PC-enriched (Figure 7I). Because antimicrobial genes comprise half of human PC DEGs (Supplementary Table 1), PCs largely appear to function to protect the ISC niche.49

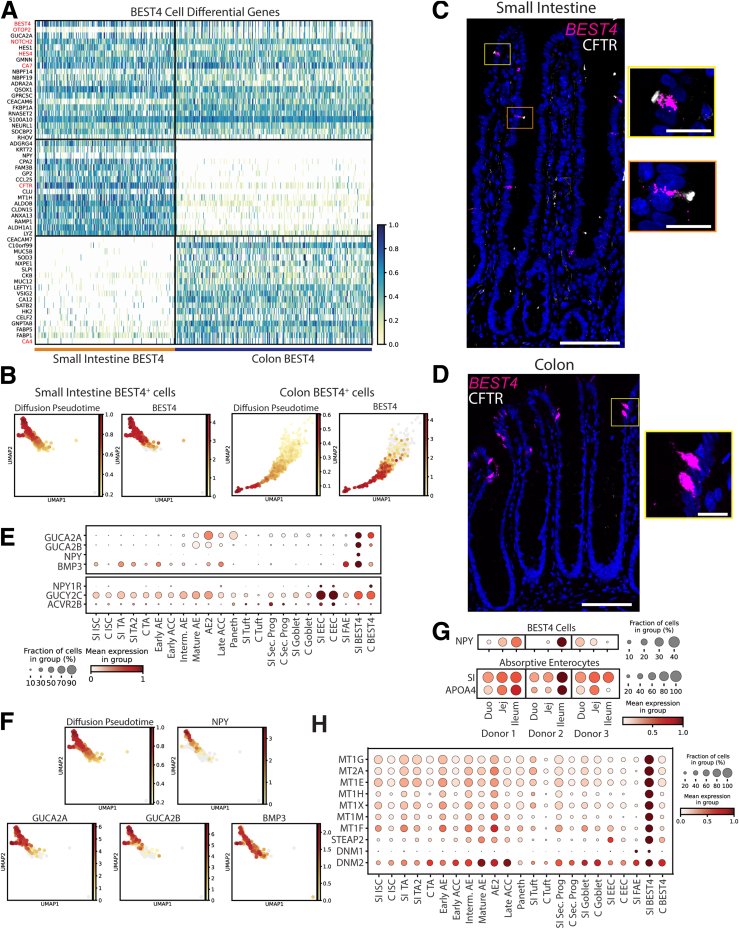

BEST4+ Cells

Recent human scRNAseq studies have described a novel intestinal lineage, absent in mice, expressing BEST4, SPIB, and CA7,5 with SI-specific CFTR9,10 and colon-specific OTOP2. Because these cells often are described by their expression of BEST4, here we label these SI and colon clusters BEST4+ cells. Our DEGs encompassed all of the previously defined markers for BEST4+ cells (Figure 8A). By comparing with diffusion pseudotime, which infers trajectory,50 our data suggested that BEST4 is only expressed to high levels as the cells mature (Figure 8B), and this was confirmed with in situ hybridization, with BEST4-high cells never seen in the proliferative crypts of SI (Figure 8C) or colon (Figure 8D). In line with previous literature,9,10 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein was shown to mark the apical tips of SI BEST4+ cells (Figure 8C) but not colonic BEST+ cells (Figure 8D). With the function of BEST4+ cells largely unknown, DEGs were used to predict their physiological roles. DEGs included GUCA2A and GUCA2B5, which act as prohormones regulating satiety.51 Consistent with a previous report, we found these genes expressed in SI and colon BEST4+ cells,9 yet our database furthers this finding by showing that both genes are expressed higher in SI BEST4+ cells than in colonic BEST4+ cells (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

BEST4+cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in BEST4+ cells vs other lineages (top; red: classic markers), SI vs colon BEST4+ cells (middle), colon vs SI BEST4+ cells (bottom). (B) UMAPs showing all SI (left) and colon (right) BEST4+ cells colored according to predicted diffusion pseudotime or expression of BEST4 mRNA. (C and D) In situ hybridization showing BEST4 mRNA (magenta), immunofluorescence staining CFTR protein (white), and nuclei (blue) in human (C) jejunum and (D) colon. Scale bars: 100 μm; 20 μm (zoomed panels). (E) Dotplot showing secreted genes (top) and their receptors (bottom) across lineages. (F) UMAPs of BEST4+ cells showing predicted diffusion pseudotime and expression of secreted peptides. (G) Expression of NPY, SI, and APOA1 across regions for each donor. (H) Dotplot showing genes involved in metal binding and endocytosis across lineages. UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. CFTR, Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator; GUCA2, Guanylate Cyclase Activator 2A; NPY, Neuropeptide Y.

We identified 2 previously unreported secreted peptides, NPY and BMP3, specifically in SI BEST4+ cells (Figure 8E). NPY expression is unexpected in intestinal epithelium,52 and gut BMP3 is largely studied for its antitumor roles.53 Similar to BEST4, we found that NPY, GUCA2A, and GUCA2B expression increased with BEST4+ cell maturation, while BMP3 was expressed independently of maturation (Figure 8F). Interestingly, EECs express receptors for all 4 genes, suggesting EEC–BEST4+ cell crosstalk (Figure 8E).

Because NPY is proposed to affect gastrointestinal (GI) motility and energy homeostasis,54,55 we probed if NPY correlated with genes induced after meals. We found strong positive correlations across SI regions for each donor between SI BEST4+ cell NPY expression and AE expression of SI (R = 0.82) and APOA4 (R = 0.86), which are induced by dietary sugar56 and fat57 (Figure 8G). We found further positive correlations with AE genes involved in dietary metabolism (Supplementary Table 5), and negligible correlation with housekeeping genes ACTB (R = -0.22) or GAPDH (R = -0.08), suggesting postprandial induction of SI BEST4+ NPY expression. Further SI BEST4+ cell DEGs included ADRA2A and CHRM3, receptors involved in intestinal motility58 (Supplementary Table 1), reinforcing that SI BEST4+ cells regulate intestinal motility after meals.

BEST4+ cells likely absorb dietary heavy metals. Metallothioneins, which bind heavy metals and prevent toxicity,59, 60, 61 were described in colonic BEST4+ cells,5 yet we found 7 metallothioneins specifically enriched in SI BEST4+ cells (Figure 8H) alongside STEAP2, a metalloreductase for copper and iron,62 suggesting SI BEST4+ cells maintain SI metal ion homeostasis.61, 62, 63 Our data indicate BEST4+ cells perform diverse roles within the intestinal epithelium, laying the groundwork for functional studies.

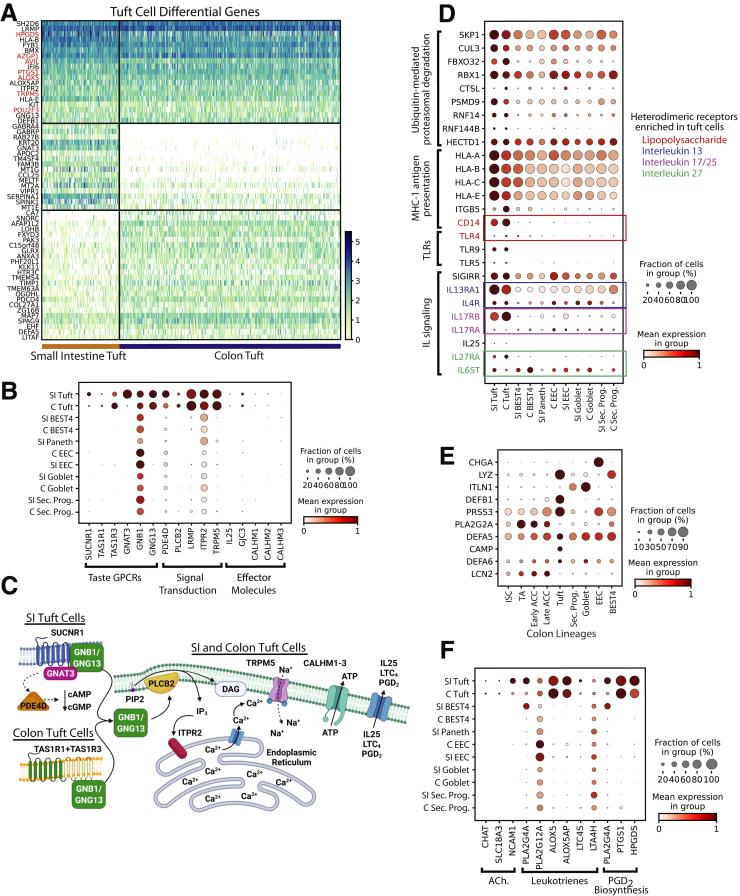

Tuft Cells

Tuft cells are chemosensory cells that regulate type 2 immune reactions64, 65, 66 in the intestinal epithelium through interleukin (IL)25 signaling in response to pathogenic metabolites.67, 68, 69 SI and colon tuft cells share many classic markers9,70 (Figure 9A, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). DCLK1, a key murine marker,69 was not observed as a DEG. SUCNR1, a G-protein–coupled receptor mediating SI IL25 release,71 was negligible in the colon, suggesting SI and colon tuft cells differentially detect succinate-producing pathogens (Figure 9B and C). Colonic tuft cells likely detect umami-chemosensory cues (eg, microbe-derived free amino acids) with heterodimeric umami taste receptor subunits TAS1R1 and TAS1R3 (Figure 9B and C).72 Downstream taste signal transduction genes are enriched in SI and colon tuft cells,64,65 with SI-specific GNAT3 likely activating PDE4D to decrease intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cAMP/cGMP)73 (Figure 9B). This suggests human SI tuft cells have multiple responses to succinate-producing microbes (eg, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis), whereas colonic tuft cells respond to other microbial taxa.

Figure 9.

Tuft cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in tuft cells vs other lineages (top; red: classic markers), SI vs colon tuft cells (middle), and colon vs SI tuft cells (bottom). (B) Dotplot showing tuft cell enrichment of genes specific to taste signal transduction. (C) Organ-specific signal transduction in SI vs colon tuft cells. (D) Dotplot showing tuft cell–enriched genes enabling interactions with innate and adaptive immune system. (E) Dotplot showing 10 highest-expressed antimicrobial peptides across colon lineages. (F) Dotplot showing tuft cell–specific genes for producing acetylcholine, eicosanoids, and prostaglandins. Schematics in panel C were created with BioRender.com. C, Colon; GPCR, G-protein Coupled Receptor; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Beyond triggering type 2 immunity, tuft cell DEGs allow broad interaction with the adaptive and innate immune systems. Tuft cell DEGs implicate ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation, with enriched Skp, Cullin, F-box containing complex (SCF) complex components (SKP1, CUL3, FBXO32, RBX1) initiating exogenous antigen processing for presentation74,75 to the major histocompatibility complex 1 antigen presentation complex (Figure 9D). This suggests tuft cells interact with the adaptive immune system after luminal stimuli. Human tuft cells also uniquely express unappreciated Toll-like receptors (TLR9, TLR5, and TLR4), which bind bacterial/viral DNA, flagellin, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), respectively (Figure 9D).76, 77, 78, 79 Expression of the LPS co-receptor CD14 across tuft cells77 (Figure 9D) supports this novel role in bacterial-related immune responses.

Tuft cells show possible autoregulatory mechanisms for these pathogen-response pathways. Tuft cells express heterodimeric IL25-specific receptor components (Figure 9D), which may create a positive feedback loop to amplify IL25 signaling.80 SIGIRR may also negatively autoregulate the Toll-like receptor 4–LPS response.81, 82, 83 These implicate tuft cells as dynamic sentinels linking luminal contents to the immune system.

Tuft cells produce antimicrobial peptides in the SI to complement those produced by PCs (Figure 7G). In the colon, which lacks PCs, tuft cells express 6 of the top 10 colonic antimicrobial peptides (Figure 9E). Human and murine tuft cells also produce neuromodulatory and immunomodulatory compounds. We found genes necessary for acetylcholine synthesis, communication with neurons,84 and enzymes involved in eicosanoid and prostaglandin D2 production, which broadly regulate inflammation85 (Figure 9F). These analyses suggest tuft cells regulate luminal microbes, communicate with the nervous system, and affect systemic immune responses.

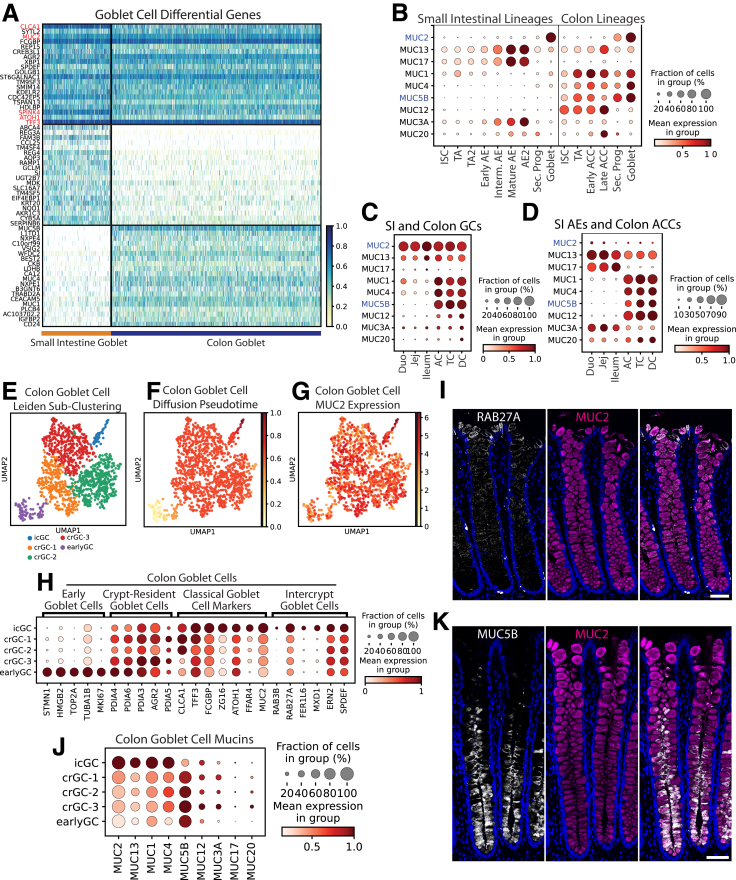

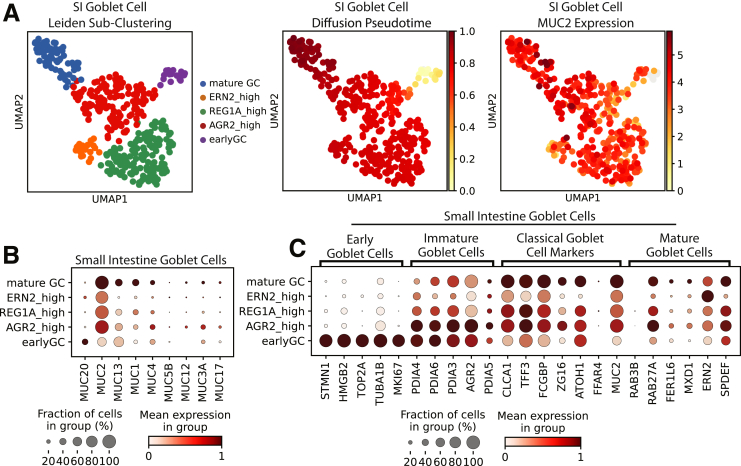

Goblet Cells

GCs produce membrane-bound and secreted mucin glycoproteins that lubricate the gut, act in signaling, support commensal bacteria, and form the protective mucus barrier.67,86, 87, 88 DEGs include classic markers CLCA1, MUC2, and TFF3, with colonic GCs expressing higher WFDC2, consistent with previous findings5 (Figure 10A). Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs confirmed GCs principally act in mucus production and secretion, with top-enriched pathways including glycosylation, Golgi/Endoplasmic Reticulum vesicle transport, and unfolded protein response (Supplementary Table 6).89, 90, 91, 92 We found secreted MUC2 and transmembrane MUC13 expressed across organs and colon-enriched MUC1, MUC4, and MUC5B (Figure 10B and C). Although GCs are considered the major intestinal mucus producers, we also mapped glycocalyx-forming transmembrane mucins, which protect against pathogenic bacteria,93,94 in AEs and ACCs (Figure 10D).

Figure 10.

Goblet cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in GCs vs other lineages (top; red: classic markers), SI vs colon GCs (middle), and colon vs SI GCs (bottom). (B) Dotplot showing expression of the 9 highest-expressed mucins across GCs and proliferative and absorptive lineages of the SI and colon (blue: gel-forming mucins). (C) Dotplot showing the 9 highest-expressed mucins across GCs by region. (D) Dotplot showing expression of the 9 highest-expressed mucins in all absorptive enterocytes and colonocytes by intestinal region. (E) Leiden subclustering of colon GCs. (F) Diffusion pseudotime of colon GCs. (G) UMAP of MUC2 expression in colon GCs. (H) Dotplot showing markers of murine GC subpopulations in the human colon GC subclusters defined in panel E. (I) Immunofluorescence staining for protein expression of RAB27A (white), MUC2 (magenta), and nuclei (blue) in human colon (2-μm optical slice). (J) Dotplot showing expression of mucins in colonic icGCs, crypt-resident goblet cells (crGCs), and early goblet cells. (K) Immunofluorescence staining for protein expression of MUC5B (white), MUC2 (magenta), and nuclei (blue) in human colon (2-μm optical slice). Scale bars: 50 μm. UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; Duo, Duodenum; Jej, Jejunum.

GCs commonly are considered homogenous, however, GCs in the mouse colon recently were separated into functionally distinct groups, with intercrypt GCs (icGCs) producing more permeable mucus than crypt-resident GCs.95 Human colonic secretory progenitors and GCs subclustered into similar groups corresponding with differentiation status and marked by genes defined in mouse GC heterogeneity95 (Figure 10E–H). Distinct icGCs on the colon surface were visualized using immunofluorescence, with RAB27A localized to the surface GC cells (Figure 10I). Some mucus secretion genes (MUC2, ZG16) were expressed highest in icGCs, consistent with icGCs constitutively secreting mucus,96 and this was supported by higher mucin 2 (MUC2) seen in surface GCs via immunofluorescence (Figure 10I and K). Notably, crypt-resident GCs and icGCs expressed different mucin genes (Figure 10C), as verified with immunofluorescence showing crypt base–specific mucin 5b (MUC5B) protein expression (Figure 10K) and consistent with distinct mucus production in human beings shown via lectin staining.95 Similar SI subclusters were observed with less obvious mucin differences (Figure 11). The physiological significance of this human GC heterogeneity necessitates further functional studies.

Figure 11.

SI goblet cell subclustering. (A) Left: Leiden subclustering of SI goblet cells, with subclusters named according to genes with high expression. Middle: UMAP of SI goblet cells marked by diffusion pseudotime. Right: UMAP of SI goblet cells marked by MUC2 expression. (B) Dotplot showing expression of mucins in SI GC subpopulations. (C) Dotplot showing expression of mouse-implicated markers of GC subpopulations in human SI GC subclusters. UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

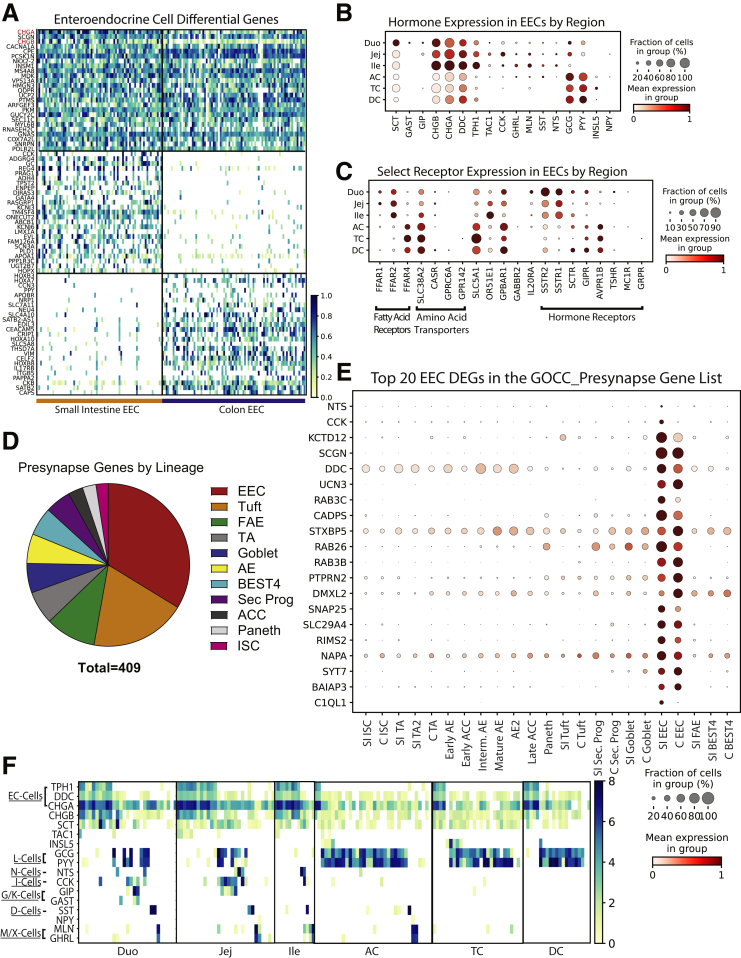

Enteroendocrine Cells

EECs secrete hormones to communicate throughout the body. EEC hormone profiles have been characterized at the single-cell level in mice, using EEC reporters to enrich for this rare lineage.97,98 However, transcriptomic differences exist between mouse and human EECs.97,99 Human organoids with an EEC reporter yielded sufficient EECs for scRNAseq analysis, although potential differences from primary EECs are unclear.97 Although several human scRNAseq studies include EECs,4, 5, 6,9,10 our 154 EECs represent a large and informative scRNAseq data set of primary human EECs.

Regional expression of hormones and other signaling machinery in EECs was surveyed (Figure 12A–C). An early study that immunostained regional biopsy specimens found SI-segregated Cholecystokinin (CCK), gastrin (GAST), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), neurotensin (NTS), motilin (MLN), and secretin (SCT).100 Our data confirm this bias but additionally detected low levels of CCK, NTS, MLN, and SCT in colonic EECs, suggesting higher sensitivity of scRNAseq. Colonic NTS and CCK expression also was absent in a study analyzing region-unspecified colon,6 emphasizing the importance of analyzing all colon regions. Fatty acid receptors FFAR1 and FFAR2 were enriched in SI EECs, with FFAR4 specific to colon (Figure 12C). EECs also express several hormone receptors, indicating crosstalk among EECs. Novel gut–brain crosstalk recently was described, with murine EECs forming synapses with the vagus nerve.101, 102, 103 Thirty-one DEGs from SI and colon EECs are in the GOCC_Presynapse list (Figure 12D) and 33.7% of genes in the GOCC_Presynapse list expressed highest in EECs (Figure 12E), suggesting a human equivalent of these mouse EECs, termed neuropods.102 These patterns describe EEC crosstalk within the gut and between the gut and brain, further illuminating newly appreciated functional roles of EECs.

Figure 12.

Enteroendocrine cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in EECs vs other lineages (top, red: classic markers), SI vs colon EECs (middle), and colon vs SI EECs (bottom). (B) Dotplot of EEC regional hormone gene expression. (C) Dotplot of EEC expression of select receptors by region. (D) Dotplot showing expression of DEGs of SI or colon EECs that are present in the GOCC_Presynapse gene list. (E) Pie chart of all genes within the GOCC_Presynapse gene list shown by lineage in which they have the highest expression (SI and colon lineages are combined when applicable). (F) Heatmap showing hormone expression in each individual EEC. Duo, Duodenum; G/K, G-cells/K-cells; Ile, Ileum; Jej, Jejunum; M/X, M-cells/X-cellsD.

EECs are classified into subtypes by hormone expression.104,105 A regional breakdown of individual EECs was constructed to visualize EEC subtypes (Figure 12F). Enterochromaffin cells appear in each region, and ileal L cells were undetected. Multiple EECs express 8–10 hormones, expanding on studies identifying polyhormonal EECs.106,107 GAST and GIP largely segregated from duodenal L cells yet overlapped in jejunum. We noted rare NPY expression in MLN+ and GHRL+ EECs in jejunum and AC. Future studies combining our EECs with additional regional data sets hopefully will improve our understanding of EEC subclusters.

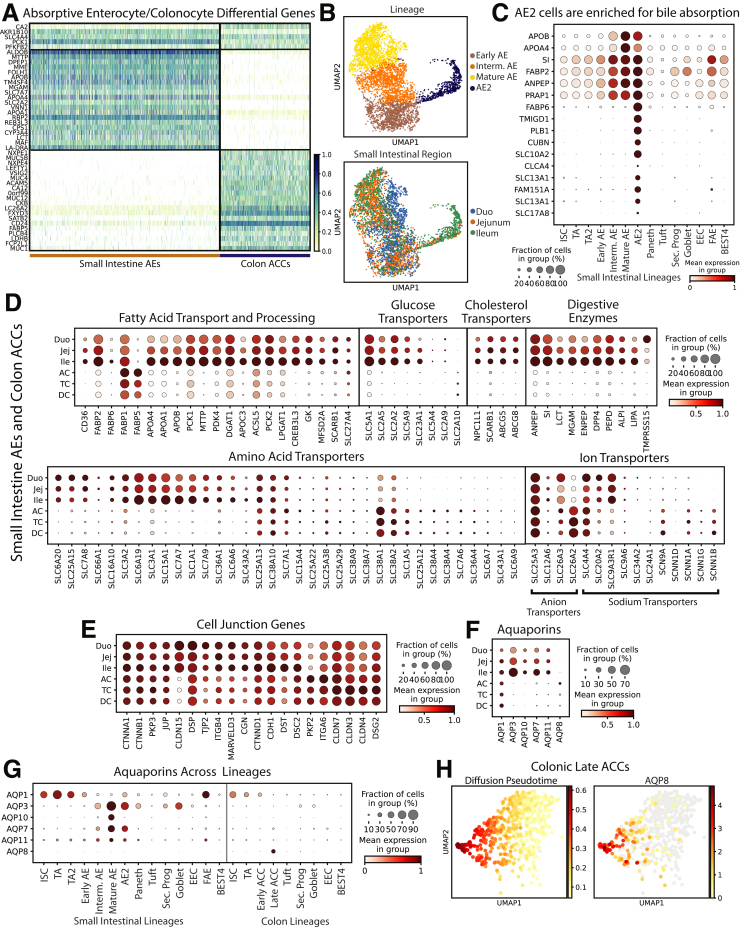

Absorptive Enterocytes and Colonocytes

AEs and ACCs perform nearly all intestinal absorption.108 Three AE Leiden clusters and 2 ACC clusters were consistent with increasing maturity, reflecting other reports,4,9,33 and 1 cluster largely from donor 3 ileum (AE2) separated from other AEs (Figures 1C and 13B). A DEG signature was defined by comparing DEGs from all AEs and all ACCs. Surprisingly, only 5 DEGs were shared across SI and colonic absorptive populations (Figure 13A), indicating stark organ differences. AE2s expressed mature AE markers (Figure 13B) alongside bile acid absorption genes109 (Figure 13C). It is unclear why ileal AEs of donor 3 clustered separately. Possible explanatory donor-specific demographics include donor 3 having the lowest body mass index, being the only African American, and the only donor with type II diabetes. Meal timings across donors also might induce unique expression patterns, as described for certain genes.56,57

Figure 13.

Absorptive cells. (A) Heatmap of DEGs in absorptive cells vs other lineages (top), AEs vs ACCs (middle), and ACCs vs SI AEs (bottom). (B) UMAPs showing the AE2 Leiden cluster (top) and cells by region (bottom). (C) Dotplot of classic mature AE markers and top 10 DEGs for AE2 cluster. (D) Dotplots showing regional expression of genes involved in digestion and absorption in all AEs and ACCs. (E) Dotplots showing the 20 highest-expressed cell junction genes in AEs and ACCs by region. (F) Dotplots showing regional aquaporin expression in AEs and ACCs. (G) Dotplot showing aquaporin expression across lineages. (H) UMAPs of late ACCs showing predicted diffusion pseudotime (left) and AQP8 expression (right). UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; Duo, Duodenum; Ile, Ileum; Jej, Jejunum.

Macronutrient and micronutrient handling was mapped across all AEs and ACCs (Figure 13D). Most fatty acid, glucose, and cholesterol transporters were SI-enriched, with regional data showing increasing expression from duodenum through ileum for most genes (Figure 13D). Digestive enzymes showed ileal enrichment, except for the duodenum-specific serine protease TMPRSS15/enteropeptidase.110 Ion transporters showed the most regional differences, with SLC25A3 and SLC4A4 spanning all regions, colon-enriched SLC26A2, and SI-enriched SLC9A3R1. Finally, SCNN1 sodium transporter subunits were colon-enriched, possibly regulating colonic water uptake. This regional map expands upon previous organ-level analyses, emphasizing the importance of the ileum in digestion.

Intestinal barrier function, largely conferred by cell-junction proteins, is essential for well-regulated absorption and antimicrobial defense.111 Regional mapping of the 20 highest-expressed cell junction genes (Figure 13E) showed equal expression of many cell-junction genes across AEs and ACCs, while others showed regional enrichment. Claudins (CLDN) are primary determinants of tight junction barrier function and epithelial integrity.108,111 CLDN1 and CLDN15 were SI-enriched, and CLDN3, CLDN4, and CLDN7 were highest in TC. Notably, no cell junction genes were expressed highest in DC. Ulcerative colitis often originates in the distal large intestine, raising the possibility that higher junction protein expression in AC and TC might protect against certain inflammatory conditions.112, 113, 114

Aquaporin proteins (AQPs) are the major intestinal transcellular water transporters.115 We confirm a previous report showing increased AQP3, AQP7, and AQP11 in ileum vs colon and colon-enriched AQP8 (Figure 13F); however, we found AQP1 widely expressed.6 Aquaglyceroporin (AQP3, AQP7, AQP10) expression is highest in mature AEs (Figure 13G) and increases from duodenum to ileum alongside lipid metabolism genes (Figure 13D and F). This suggests AQP-mediated glycerol transfer functions in AE triglyceride processing. We note unappreciated AQP1 specificity in ISCs and TA cells and uniquely restricted AQP8 expression in the most mature late ACCs in the AC (Figure 13H). These distinct differences suggest specific physiological roles that should be functionally investigated.

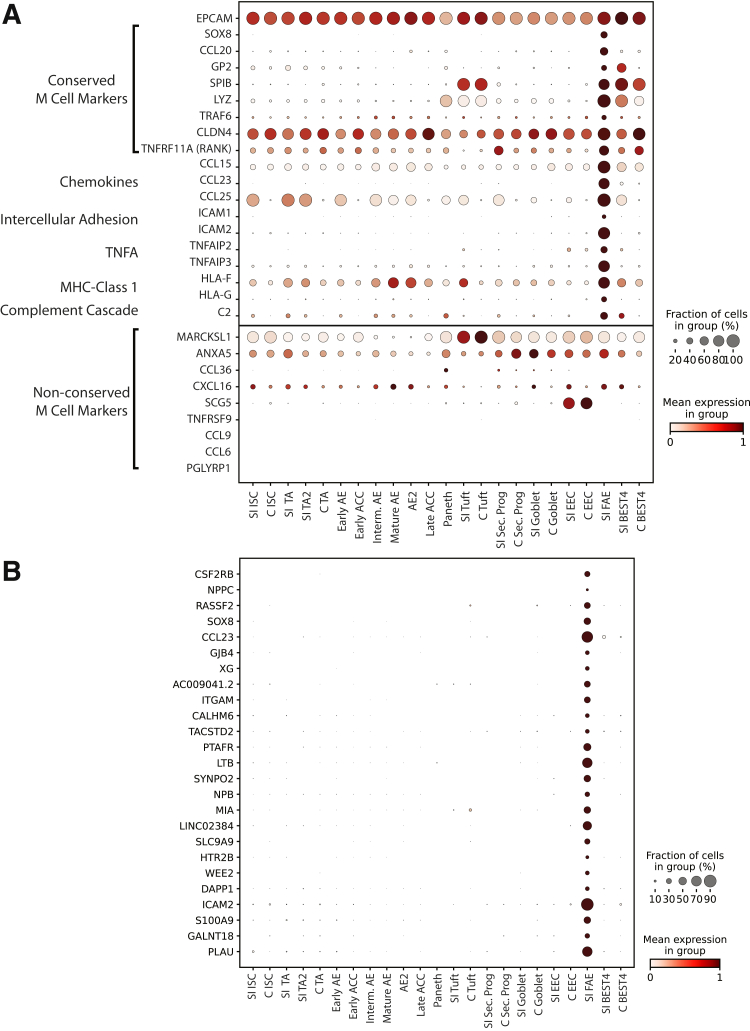

Follicle-Associated Epithelium

Rare FAE cells reside in small puncta throughout the intestines.116 FAE includes microfold (M) cells, which transport luminal antigens to resident immune cells.117 M cells have been explored almost exclusively in mice118, 119, 120 or using directed differentiation in vitro,121 with only 1 scRNAseq study isolating healthy human M cells.10 Our data set included a 19-cell cluster from a single donor (donor 2) enriched for microfold cell (M-cell) markers122, 123, 124 and immune crosstalk genes while still expressing Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EPCAM) (Figure 14A). We defined 145 DEGs (Supplementary Table 1), finding many FAE-unique genes (Figure 14). Pathway enrichment analysis implicated these DEGs in immune cell interactions, verifying expected M-cell function (Supplementary Table 7). Several murine M-cell–specific markers,117,123,125 were either widely expressed or absent (Figure 14), suggesting species functional differences. Because these data arise from a small set of cells from a single donor, future studies are necessary to fully define these cells, possibly through enriching for FAE using recently described methods.116

Figure 14.

Follicle-associated epithelium. (A) Top: Dotplot showing expression of EPCAM and conserved M-cell markers and other genes known to interact with the immune system across lineages. Bottom: Genes implicated in mouse M cells that are not specific to human FAE. (B) Dotplot showing expression of the top 20 FAE DEGs across lineages. EPCAM, Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule; C, Colon; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TNFA, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha.

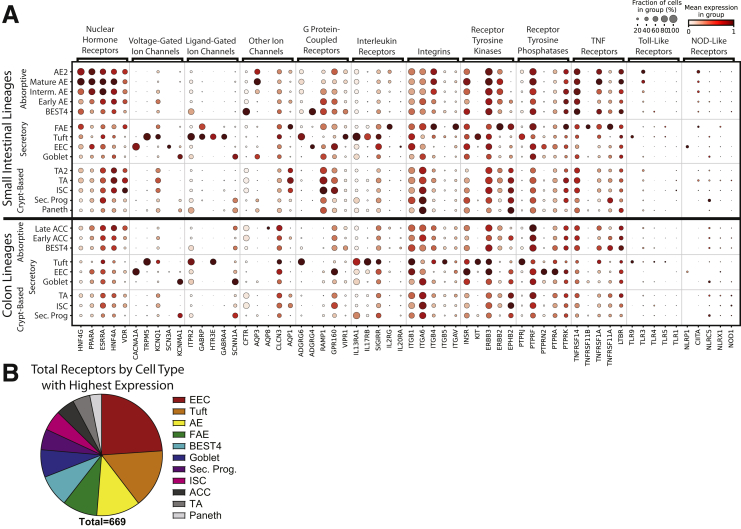

Receptors/Drugs

We finished by designing 2 approaches showing how to find associations between lineages, receptors, and drug targets. Major receptor families were surveyed across lineages and classified as high-, intermediate-, or low-expressing (Supplementary File 1, Supplementary Table 8). The 5 highest-expressing genes per family were grouped across lineages (Figure 15A). Several patterns appeared from these 60 receptors: 20 receptors were highest-expressed in tuft cells, 11 in EECs, 10 in AE/ACC, and 9 in FAE; 12 villi-enriched vs 3 crypt-enriched; 4 SI-enriched vs 0 colon-enriched; and many uniquely marked individual lineages (12 in tuft cells, 3 in EECs, and so forth), showing potential ways to target regions and lineages.

Figure 15.

Extrinsic receptors and drug targets. (A) Dotplot showing expression of the 5 highest-expressing members of each major receptor family by lineage. Top: Small intestinal lineages. Bottom: Colonic lineages. (B) Pie chart showing receptor genes expressed in the intestinal epithelium by lineage with the highest expression. NOD, Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain Sec. Prog., Secretory Progenitor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

To test the novelty of these observations, we reviewed literature regarding the 12 receptors found to be unique to tuft cells. We found direct literature connections to human or mouse intestinal tuft cells for only 5 of 12 receptors (TRPM5, ITPR2, HTR3E, IL13RA1, IL17RB), with no connection found for 7 receptors (GABRA4, ADGRG6/GPR126, SIGIRR, ITGB5, KIT, PTPRJ, TLR9). These 7 unappreciated lineage-specific receptors arose from analyzing just 60 receptors in 1 lineage, and our full data set included 669 total receptors (Figure 15B, Supplementary File 1). This receptor atlas across lineages, organs, regions, and donors provides a powerful foundation to explore how extrinsic signals from local microenvironments, dietary and microbial influences, and pharmaceuticals may affect intestinal epithelial lineages.

We next explored how pharmacologic agents might directly affect the intestinal epithelium. Few drugs deliberately target the intestinal epithelium126, 127, 128, 129 and common GI side effects often are unexplained at the cell-lineage level.130 We found 498 Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs had 232 primary gene targets expressed in our gut epithelial data set (Figure 16A, Supplementary Table 9). Beyond primary targets in the gut epithelium, lineages express many enzymes that can functionalize drugs through metabolism.127, 128, 129 We show gene expression for phase I and phase II drug metabolism enzymes by lineage with the highest expression in the intestinal epithelium (Figure 16A) and quantified gene expression by lineage and region (Supplementary Table 10). We found CES2, which metabolizes the cancer drug irinotecan into biologically active SN-38,131 to be the highest-expressed phase I metabolism gene in the SI, with AE enrichment. Interestingly, UGT1A1, the phase II enzyme that inactivates SN-38,132 has low gut epithelial expression (Supplementary Table 10). This suggests that irinotecan may experience prolonged activation in the gut, advancing the idea that orally administered irinotecan might be effective against intestinal cancers.133, 134, 135 Our easily searchable data set quantifies the expression of genes important for intestinal metabolism of endobiotics, environmental toxicants, and pharmaceuticals.

Figure 16.

Drug targets. (A) Pie charts of primary targets of all approved drugs (left) and all phase I (center) and phase II (right) drug metabolism genes expressed in the intestinal epithelium shown by lineage with highest expression. (B) Primary targets of drugs used to treat IBD found to have expression in the intestinal epithelium. (C) Dotplots showing expression of primary targets of drugs used to treat IBD by lineage split into high-, middle-, and low-expressing tables for better visualization. Note scaling changes between tables. (D) Left: In situ hybridization showing BEST4 RNA (white) and immunofluorescence staining for FKBP1A protein (magenta) and nuclei (blue) in human jejunum (top) and colon (bottom). Center: Immunofluorescence staining for IMPDH2 protein (magenta), KI67 (white), and nuclei (blue) in human jejunum (top) and colon (bottom). Right: Immunofluorescence staining for DHFR protein (magenta), KI67 (white), and nuclei (blue) in human jejunum (top) and colon (bottom). Optical slice was 2 μm for all. Scale bars: 50 μm. (E) Dotplot showing expression of the top 3 highest-expressed targets of IBD drugs in the intestinal epithelium across regions and split by donor. FKBP1A, FKBP Prolyl Isomerase 1A; IMPDH2, Inosine Monophosphate Dehydrogenase 2; JAK, Janus Kinase; Sec. Prog., Secretory Progenitor.

As an example of a disease-focused approach, we evaluated primary gene targets of drugs prescribed for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Most IBD drugs are anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory, so primary targets often are not expressed in the intestinal epithelium, yet our database shows 9 primary gene targets of 8 IBD drugs have epithelial expression (Figure 16B). We mapped epithelial expression of their primary target genes to locate potential off-target effects (Figure 16C). We found high FKBP1A, a tacrolimus (Prograf, Astellas Pharma Inc., Tokyo, Japan) target, in the little-understood BEST4+ cells. Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, Genentech, South San fransisco, CA) targets IMPDH2 and IMPDH1 were expressed in proliferative crypt populations and EECs, respectively. The methotrexate target DHFR was highest in TA and progenitor cells, while the tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Pfizer, New York, NY) target JAK1 had broader expression. Because functional protein expression is not always found in the same cells as mRNA translation, especially given the quick cellular turnover of the intestine,136 we stained for protein expression of the top 3 highest expressed gene targets that appear enriched in specific cell types: FKBP1A, IMPDH2, and DHFR. We found all 3 proteins enriched in the lineages implicated by our transcriptional data (Figure 16D), highlighting the usefulness of our data set for predicting drug targets. These drugs can be orally administered and primary targets in the epithelium could explain common GI side effects.137, 138, 139 This small subset of drug targets highlights a spectrum of potential unintended epithelial effects on ISC/TA renewal, EEC hormonal regulation of appetite and gut motility, and unknown effects from other lineages.

Personalized precision medicine is an emerging field motivating new technologies.140 We used our drug-target atlas to assess regional variability of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and tofacitinib target genes, FKBP1A, IMPDH2, and JAK1, across individual donors to inform potential patient-dependent effects (Figure 16E). Higher colonic expression of all 3 targets suggests that patients may experience colon-specific off-target effects. Comparing donors potentially hints at susceptibility to drug side effects, with donors 2 and 3 generally expressing target genes higher than donor 1. Although 3 donors are insufficient for statistically significant conclusions, we provide a framework to generate observations to inform larger studies. We hope our lineage-, regional-, and donor-specific data on primary drug targets will aid gastroenterology and pharmacology to better understand potential intestinal drug effects.

Discussion

In this study, we provide a comprehensive cell-level transcriptomic view of the SI and colon epithelium with regional resolution across multiple human beings. Our analyses independently confirm and advance prior studies, define important differences between mouse and human beings, and highlight how lineages vary along the proximal–distal axis. We include easy-to-search tables for DEGs, receptors, and drug targets that can be investigated by most investigators and trainees. Overall, our database provides a foundation for understanding individual contributions of diverse epithelial cells across the length of the human intestine and colon to maintain physiologic function.

Our experimental design had many unique strengths. We used healthy transplant organ tissue from 3 adult male donors varying in age, race, and body mass index to characterize intestinal epithelial cells from duodenum through DC. DNA-oligo hashtag antibodies allowed a single library per donor for all 6 regions to be sequenced together, saving cost and avoiding intradonor batch effects while preserving biological variability. The hashtag antibodies also allowed for increased stringency when filtering for mutliplets and contamination. Analyzing cells across 6 regions allowed for comprehensive transcriptional signatures of genes significantly enriched in each lineage across the entire gut from 3 donors. We mapped cell cycle, mucins, hormones, transporters, digestive genes, and barrier function genes along the regions of the SI and colon. We showed drastic differences in PC growth factor expression from mouse literature and highlight the insufficiency of LYZ for uniquely marking human PCs. We used PAGA to infer a differentiation trajectory for each lineage and suggest organ-specific maturation for tuft and BEST4+ cells. We propose novel tuft cell interactions with pathogens and the immune system. Finally, our survey of receptors and primary drug targets across lineages highlights the utility and ease of our database to find previously undescribed gene expression. The regional differences found throughout our study highlight the importance of regional selection when studying the gut, yet many colonic scRNAseq studies do not specify the sample region or mention if pooled samples are from consistent regions. We hope our database serves as a resource to understand how drugs affect the intestinal epithelium and as guidance for future precision medicine approaches.

Methods

Donor Selection

Human donor intestines were received from 3 male organ donors, aged 29, 45, and 53 years (details in Figure 2), from HonorBridge (Formerly Carolina Donor Services, Durham, NC) with the following acceptance criteria: age ≤65 years, brain-dead only, human immunodeficiency virus negative, hepatitis negative, syphilis negative, tuberculosis negative, coronavirus disease-2019 negative, and no bowel surgery, severe abdominal injury, cancer, or chemotherapy. Pancreas donors were excluded to avoid duodenum loss. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board determined this study does not constitute human subjects research.

Tissue Processing

Intestines were transported on ice in University of Wisconsin Cold Storage Solution (Bridge to Life, Northbrook, IL). Tissue dissection began within 8 hours of cross-clamping. Fat/connective tissue were trimmed and intestinal regions were separated: duodenum (most-proximal 20 cm), jejunum/ileum splitting remaining SI, and colon split into thirds for AC/TC/DC (Figure 17). Two 3 × 3 cm mucosectomies were isolated from the center of each region for dissociation.

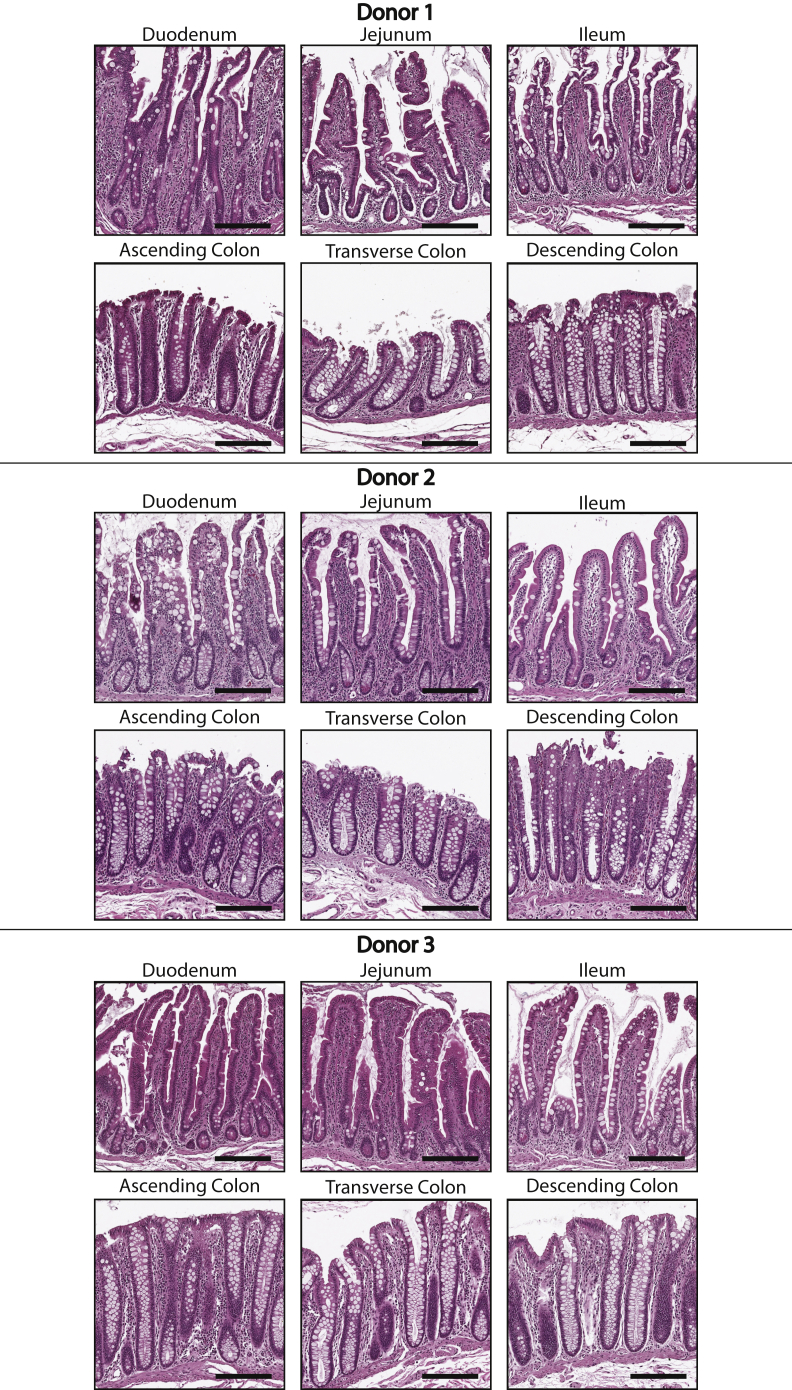

Figure 17.

Tissue histology. H&E-stained tissues from each region for all 3 donors. Scale bars: 200 μm.

Mucosectomies were incubated in 10 mmol/L N-acetylcholine in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (dPBS) at room temperature for 30 minutes to remove mucus, then washed in ice-cold chelating buffer141 + 100 μmol/L Y-27632. Tissues were incubated in chelating buffer with 2 mmol/L EDTA and 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol, then shaken to remove crypts. High-yield shakes were pooled by region, with SI shakes pooled to approximate 1:1 villus to crypt tissue by cell mass. Crypts and villi were dissociated to single cells using 4 mg/mL Protease VIII in dPBS + Y-27632 on ice for approximately 45 minutes with trituration via a P1000 micropipette every 10 minutes. Cells were checked under a light microscope and then filtered.

Sample Preparation

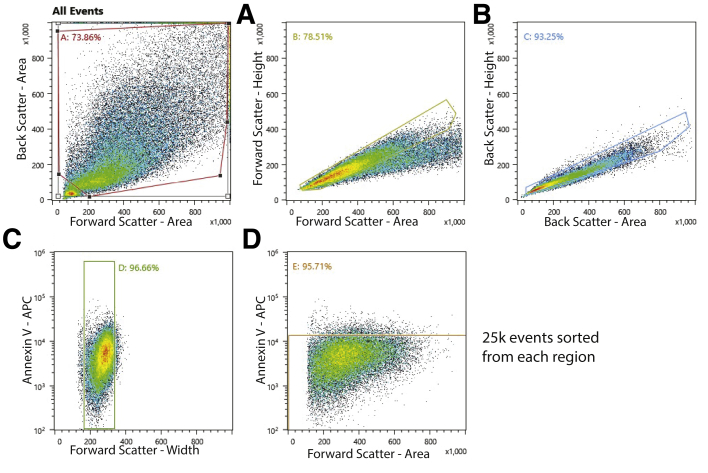

Single cells were washed with dPBS + Y-27632, resuspended in Advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 + 1% bovine serum albumin + Y-27632, and then stained with AnnexinV-Allophycocyanin (APC) (1:100) and 1 TotalSeq Anti-Human Hashtag Antibody (1:100, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) per region to track all 6 regions with a single library preparation.11 Cells were washed and resuspended in Advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium + 1% bovine serum albumin + Y-27632 for sorting on a Sony Cell Sorter SH800Z (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) to enrich for live single epithelial cells (Figure 18). There were 25,000 cells that passed Annexin V live/dead parameters and were fluorescence-activated cell sorter isolated for each region, then different cell hashing antibodies were added to cells from each of the 6 regions before pooling for library preparation. An additional live/dead analysis was performed after pooling and approximately 10,000 cells from the pooled population were loaded onto the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ GEM, Library and Gel Bead Kit v3.1 (PN-100012, 10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA) for complementary DNA library preparation Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Figure 18.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) strategy. FACS strategy for gating out cell fragments, likely doublets, and dead cells. APC, Allophycocyanin.

Immunofluorescence and In Situ Hybridization

Tissue samples adjacent to the sections dissociated for single-cell dissociation were dissected from each region and then fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight at 4°C. The following day, tissues were washed 3 times in water and then stored in 70% ethanol until embedding in paraffin wax. Embedded tissues were sectioned onto glass slides.

For immunofluorescence, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated using Histo-clear (Great Lakes IPM, Vestaburg, MI) and an ethanol gradient. Sections were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 20 minutes, then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections then were incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. The following day, the sections were washed in PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, slides were treated with bisbenzamide (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) and coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Table 1.

Reagents Used

| Company | Catalog number | |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent | ||

| N-acetylcholine | Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO) | A9165 |

| dPBS | Gibco (Jenks, OK) | 14190-144 |

| Na2HPO4 | Millipore-Sigma | S7907 |

| KH2PO4 | Millipore Sigma | P5655 |

| NaCl | Millipore Sigma | S5886 |

| KCl | Millipore Sigma | P5405 |

| Sucrose | Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH) | 220-1 |

| D-sorbitol | Fisher Scientific | 439-500 |

| Y27632 | Selleck Chemical (Houston TX) | S6390 |

| EDTA | Corning (Corning, NY) | 46-034-Cl |

| Dithiothreitol | Fisher Scientific | 172-5 |

| Protease VIII | Millipore Sigma | P5380 |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | Gibco | 12634-010 |

| Bovine serum albumin | Fisher Scientific | BP1600-1 |

| TotalSeq anti-human hashtag antibodies | BioLegend (San Diego, CA) | B0251-B0256 |

| 10% neutral buffered formalin | Fisher Scientific | 22-050-105 |

| Histo-clear | National Diagnostics (Atlanta, GA) | HS2001 |

| Triton X-100 | MP Biomedicals (Irvine, CA) | 02194854-CF |

| Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent | Invitrogen (Waltham, MA) | P36930 |

| Xylenes | Millipore-Sigma | 534056 |

| RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 | Advanced Cell Diagnotics (Newark, CA) | 323100 |

| Antibodies | ||

| AnnexinV-APC | BioLegend | 640920 |

| Lysozyme | Diagnostic Biosystems (Pleasanton, CA) | RP028 |

| CFTR | Cystic Fibrosis Foundation | A570 |

| Mucin 2 (Ccp58) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) | sc-7314 |

| RAB27A | Proteintech (Rosemont, IL) | 17817-1-AP |

| MUC5B | Millipore Sigma | HPA008246 |

| FKBP1A | Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA) | PA1-026A |

| IMPDH2 | Proteintech | 12948-1-AP |

| DHFR | Proteintech | 15194-1-AP |

| Ki-67 monoclonal antibody (SolA15), APC | Invitrogen | 17-5698-82 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-21206 |

| Cy3 AffiniPure F(ab')2 fragment donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA) | 711-166-152 |

| Alexa Fluor 647 AffiniPure donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) | Jackson Immunoresearch | 715-605-150 |

| Bisbenzamide | Millipore Sigma | 14530 |

| RNAscope probes | ||

| Hs-SMOC2 | Advanced Cell Diagnotics | 533921 |

| Hs-BEST4 | Advanced Cell Diagnotics | 481501 |

| TSA cyanine 3 reagent pack | Akoya Biosciences (Marlborough, MA) | SAT704A001EA |

| TSA cyanine 5 reagent pack | Akoya Biosciences | SAT715A001EA |

DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium.

For in situ hybridization, sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated using xylenes and an ethanol gradient. In situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope (ACD Bio, Newark, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol (Table 1 lists the probes used). After the in situ hybridization, sections were co-stained for protein expression with immunofluorescence, following the protocol listed earlier, starting at the blocking step.

All sections were imaged on LSM 700 and LSM710 confocal microscopes (Zeiss, Jena, Germany), and figure preparation for images was completed using FIJI (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA).

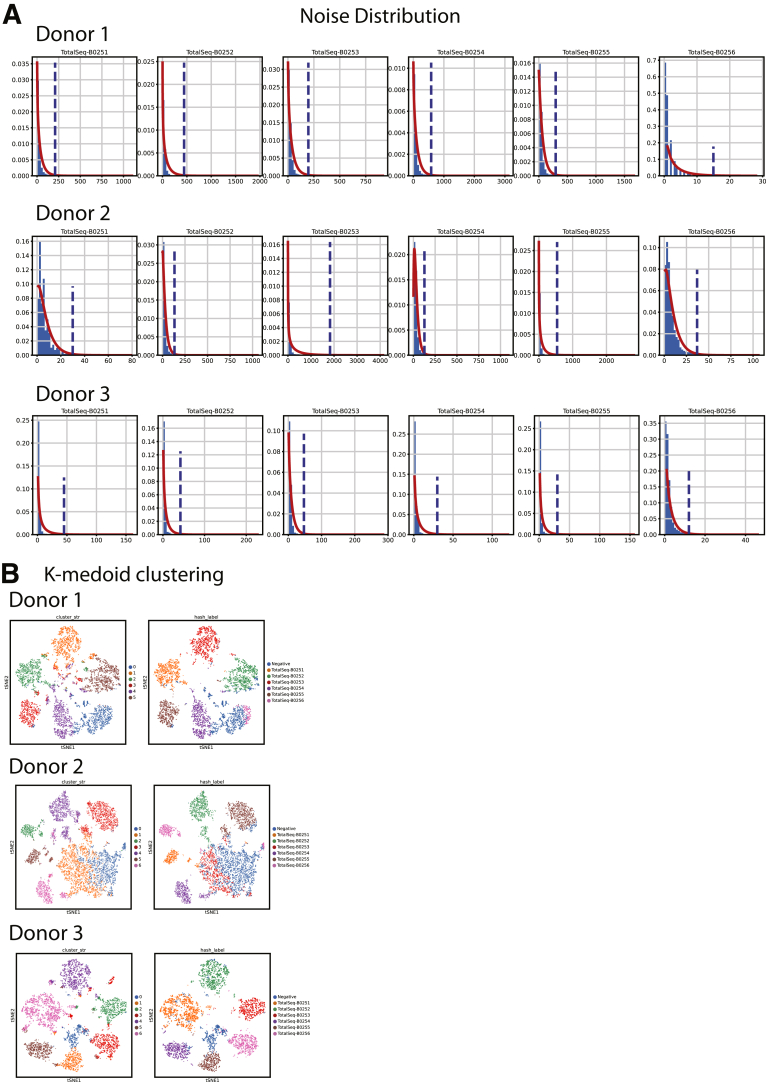

Data Preparation and Hashtag Calling

Harmony (Harmonypy, v0.0.5) was used to integrate the top 40 principal components from each data set for clustering and visualization.13 Leiden clustering was initialized with a k-nearest neighbor (kNN) graph (k = 10 neighbors) and a Leiden resolution of 0.9214 to resolve most expected physiological lineages (Figure 19). Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projections (UMAPs) were initialized with PAGA embedding of Leiden clusters,14,32 then nonepithelial EPCAM-negative lineages were eliminated. Regional hashtag deconvolution followed published methods: raw hashtag read counts were normalized using centered log ratio transformation followed by k-medoid clustering (k = 6 medoids for donor 1, k = 7 medoids for donors 2 and 3).11 Hashtag noise distributions were determined by removing the highest-expressing cluster, then fitting a negative binomial distribution to the remaining cells. Cells were considered positive for a hashtag with counts above the distribution’s 99th percentile (P < .01) threshold. Cells positive for multiple hashtags were excluded as likely doublets (Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Final clusters shown by organ.Top: Final lineage clusters used for the rest of the analyses in our study. Bottom: Lineage clusters split by region. C, Colon; Interm., intermediate; Sec. Prog., Secretory Progentior; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

Figure 20.

Hashtag deconvolution. (A) Per donor hashtag noise distributions. Blue dotted lines indicate the 99th percentile values for noise. Values above this line were called positive for a specific hashtag. (B) Left: K-medoid clustering for each donor based only on hashtag reads. Cells positive (P < .01) for multiple hashtags were removed as likely multiplets. Cells were called as negative if they did not surpass the noise threshold for all hashtags. Right: K-medoid clustering with final hashtag labeling for nonmultiplet cells.

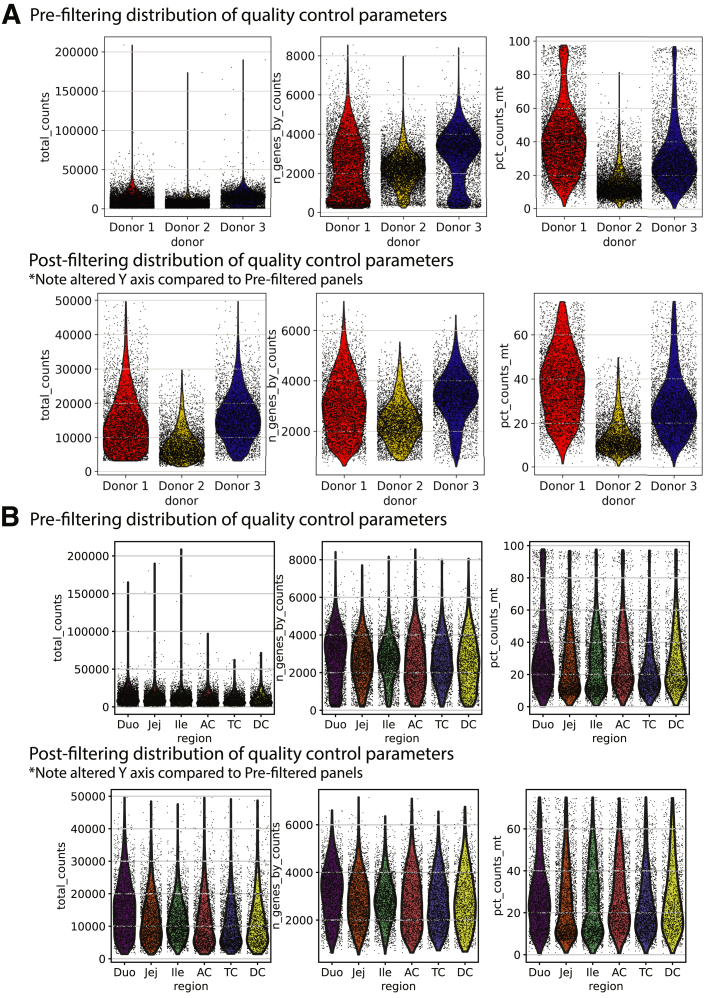

Data Processing, Filtering, Doublet Removal, and Feature Selection

After sequencing, single-cell fastq files were aligned to reference transcriptome GRCh38 with the 10× Cell Ranger pipeline (V4.0.0, 10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA), and downstream analysis was performed with scanpy (v1.7.2)142. Annotations for cell-cycle phase predictions were added following previously published methods.36 Quality filtering thresholds for each donor are shown in Table 2 and Figure 21. After filtering, read counts were log-transformed and normalized to the median read depth of donor 2, which had the fewest read counts. Variability resulting from gene expression count, mitochondrial percentage, and cell-cycle gene expression were regressed out by simple linear regression. Highly variable genes were identified with the Seurat method143 (min_dispersion, 0.2; min_mean, 0.0125; max_mean, 6), identifying 2777 genes that subsequently were used for principal component analysis. Genes were scaled to have a mean of zero and unit variance.

Table 2.

Table 2: Filtering Parameters

| Donor 1 | Donor 2 | Donor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum genes | >500 | >800 | >500 |

| Mitochondrial reads, % | <75 | <50 | <75 |

| Minimum counts | >3000 | >1000 | >3000 |

| Maximum counts | <50,000 | <30,000 | <50,000 |

Figure 21.

Filtering for cell quality. Total counts, N genes, and mitochondrial gene percentages shown for each donor before and after filtering; prefiltering (top) and postfiltering (bottom) by (A) donor and (B) region. Note differences in the Y axes between prefiltering and postfiltering rows. Duo, Duodenum; Ile, Ileum; Jej, Jejunum.

Identifying Transcriptionally Distinct Subclusters

Subclustering was performed to isolate Paneth cells from SI goblet cells, which cluster together in the overall data set. For Paneth cells, the SI_ITLN1-high cluster was subset from the main data set and 40 principal components were recalculated and reharmonized. Leiden clusters were recalculated on the new principal components based on the same 2777 highly variable genes as the initial data set with Leiden resolution of 0.15 and k = 15 neighbors.

Further subclustering on SI and colon goblet cells was performed to show goblet cell heterogeneity in the SI and colon separately. For colon goblet cells, Leiden clustering settings were as follows: k = 5 nearest neighbors, Leiden resolution of 0.3, and 4000 highly variable genes were calculated based on 22 recomputed principal components from the colon goblet cells subset. For SI goblet cells, Leiden clustering settings were as follows: k = 10 nearest neighbors, Leiden resolution of 0.4, and 2000 highly variable genes were calculated based on 19 recomputed principal components on the SI goblet cell subset.

Online Databases

Human homologs for mouse genes were defined using Ensembl version release 104 (European [European Bioinformatics Institute, Cambridgeshire, UK] Bioinformatics Institute, Cambridgeshire, UK).144 Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using Reactome,91 with focus given to pathways with a false-discovery rate of less than 0.05, as calculated by over-representation analysis, and full reports are included as Supplementary Tables 3, 4, 6, and 7. Common drugs prescribed for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease were curated using online literature. Comprehensive receptor family lists and primary target genes for all approved drugs were downloaded from Guide to Pharmacology.145 Phase I and phase II drug metabolism genes were defined via Reactome.91

Trajectory Analysis

To infer differentiation trajectories, subclustered cell populations were separated into SI and colon as previously described. For each data set, PAGA (v1.2) then was performed on a k-nearest neighbor graph of 20 neighbors constructed from 40 principle components. The resultant transition connectivity matrix was filtered to remove spurious connections (SI, >0.08; colon, >0.09).

Differential Expression Analysis

To determine genes that consistently mark a lineage, as determined by previously described Leiden clustering, in all 3 donors, the data set first was separated into SI- and colon-specific data. For each organ, the depth-normalized expression of each gene was used to fit to a negative binomial general linear model with the diffxpy package (v0.7.4). A Wald test was used to iterate through all cell lineages, testing a null model in which only donor-specific batch effects were included: against an alternative model where a cell’s inclusion in the current test lineage was included as a binary independent variable, correcting for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Each test then was repeated independently on each donor including at least 10 cells of the lineage, excluding donor as a covariate. A gene was determined to be a marker gene for a particular lineage if it met the following thresholds: (1) maximum expression in the lineage of interest, (2) q value less than 0.05 in the combined data set and all 3 donors individually, (3) minimum log2 fold-change (compared with the next highest expressing lineage) greater than 0.25, and (4) mean in-lineage normalized expression greater than 0.2.

Acknowledgments

The authors first thank the organ donors without whom our study would have been impossible. The authors thank HonorBridge (formerly Carolina Donor Services) for assistance in coordinating organ donations. The authors thank Gabrielle Cannon at the Advanced Analytics core at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and Ashley Ezzell at the Histology Research Core at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. The authors thank Michael Czerwinski for help with dissociation and computation, Nathan Kohn and Willow Liu for assistance with dissociation, and Laurianne Van Landeghem for reviewing the manuscript. We further thank the UNC Cystic Fibrosis Center for the CFTR antibody. This publication is part of the Human Cell Atlas - www.humancellatlas.org/publications

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Joseph Burclaff, Ph.D. (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Visualization: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

R. Jarrett Bliton, B.S. (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Software: Lead; Visualization: Lead; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Lead)

Keith A Breau, B.S. (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Software: Lead;Visualization: Lead; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Meryem T Ok, B.S. (Data curation: Supporting; Formal analysis: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting; Writing – original draft: Supporting)

Ismael Gomez-Martinez, B.S. (Formal analysis: Supporting; Visualization: Supporting)

Jolene S Ranek, B.S. (Software: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Aadra P Bhatt, Ph.D. (Writing – review & editing: Supporting; Intellectual contributions: Supporting)

Jeremy E Purvis, Ph.D. (Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

John T Woosley, MD (Data analysis: Supporting)

Scott T Magness, Ph.D. (Conceptualization: Lead; Funding acquisition: Lead; Supervision: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number: GSE185224. Python Scripts allowing for main steps of our analysis to be performed will be available on GitHub.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DK115806, R01DK109559, P30-DK034987, P30-DK065988, and the Katherine E. Bullard Charitable Trust for Gastrointestinal Stem Cell and Regenerative Research (S.T.M.), F32DK124929 (J.B.), T32-GM133364 (K.A.B), and F31-HL156433 and 5T32-GM067553 (J.S.R.). Also supported by a Career Development Award from the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation, and the University Cancer Research Fund (A.P.B.).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smillie C.S., Biton M., Ordovas-Montanes J., Sullivan K.M., Burgin G., Graham D.B., Herbst R.H., Rogel N., Slyper M., Waldman J., Sud M., Andrews E., Velonias G., Haber A.L., Jagadeesh K., Vickovic S., Yao J., Stevens C., Dionne D., Nguyen L.T., Villani A.C., Hofree M., Creasey E.A., Huang H., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Garber J.J., Khalili H., Desch A.N., Daly M.J., Ananthakrishnan A.N., Shalek A.K., Xavier R.J., Regev A. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell. 2019;178:714–730.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang B., Chen Z., Geng L., Wang J., Liang H., Cao Y., Chen H., Huang W., Su M., Wang H., Xu Y., Liu Y., Lu B., Xian H., Li H., Li H., Ren L., Xie J., Ye L., Wang H., Zhao J., Chen P., Zhang L., Zhao S., Zhang T., Xu B., Che D., Si W., Gu X., Zeng L., Wang Y., Li D., Zhan Y., Delfouneso D., Lew A.M., Cui J., Tang W.H., Zhang Y., Gong S., Bai F., Yang M., Zhang Y. Mucosal profiling of pediatric-onset colitis and IBD reveals common pathogenics and therapeutic pathways. Cell. 2019;179:1160–1176.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanke M., Kennedy M.M., Connelly S., et al. Single-cell analysis of colonic epithelium reveals unexpected shifts in cellular composition and molecular phenotype in treatment-naïve adult Crohn’s disease. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2022.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh K., Antanaviciute A., Fawkner-Corbett D., Jagielowicz M., Aulicino A., Lagerholm C., Davis S., Kinchen J., Chen H.H., Alham N.K., Ashley N., Johnson E., Hublitz P., Bao L., Lukomska J., Andev R.S., Bjorklund E., Kessler B.M., Fischer R., Goldin R., Koohy H., Simmons A. Colonic epithelial cell diversity in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2019;567:49–55. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0992-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., Song W., Wang J., Wang T., Xiong X., Qi Z., Fu W., Yang X., Chen Y.G. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals differential nutrient absorption functions in human intestine. J Exp Med. 2020;217 doi: 10.1084/jem.20191130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii M., Matano M., Toshimitsu K., Takano A., Mikami Y., Nishikori S., Sugimoto S., Sato T. Human intestinal organoids maintain self-renewal capacity and cellular diversity in niche-inspired culture condition. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:787–793.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Triana S., Stanifer M.L., Metz-Zumaran C., Shahraz M., Mukenhirn M., Kee C., Serger C., Koschny R., Ordonez-Rueda D., Paulsen M., Benes V., Boulant S., Alexandrov T. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals immune response of intestinal cell types to viral infection. Mol Syst Biol. 2021;17 doi: 10.15252/msb.20209833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busslinger G.A., Weusten B.L.A., Bogte A., Begthel H., Brosens L.A.A., Clevers H. Human gastrointestinal epithelia of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum resolved at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108819. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elmentaite R., Kumasaka N., Roberts K., Fleming A., Dann E., King H.W., Kleshchevnikov V., Dabrowska M., Pritchard S., Bolt L., Vieira S.F., Mamanova L., Huang N., Perrone F., Goh Kai'En I., Lisgo S.N., Katan M., Leonard S., Oliver T.R.W., Hook C.E., Nayak K., Campos L.S., Dominguez Conde C., Stephenson E., Engelbert J., Botting R.A., Polanski K., van Dongen S., Patel M., Morgan M.D., Marioni J.C., Bayraktar O.A., Meyer K.B., He X., Barker R.A., Uhlig H.H., Mahbubani K.T., Saeb-Parsy K., Zilbauer M., Clatworthy M.R., Haniffa M., James K.R., Teichmann S.A. Cells of the human intestinal tract mapped across space and time. Nature. 2021;597:250–255. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoeckius M., Zheng S., Houck-Loomis B., Hao S., Yeung B.Z., Mauck W.M., 3rd, Smibert P., Satija R. Cell Hashing with barcoded antibodies enables multiplexing and doublet detection for single cell genomics. Genome Biol. 2018;19:224. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1603-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmentaite R., Ross A.D.B., Roberts K., James K.R., Ortmann D., Gomes T., Nayak K., Tuck L., Pritchard S., Bayraktar O.A., Heuschkel R., Vallier L., Teichmann S.A., Zilbauer M. Single-cell sequencing of developing human gut reveals transcriptional links to childhood Crohn's disease. Dev Cell. 2020;55:771–783 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korsunsky I., Millard N., Fan J., Slowikowski K., Zhang F., Wei K., Baglaenko Y., Brenner M., Loh P.R., Raychaudhuri S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat Methods. 2019;16:1289–1296. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traag V.A., Waltman L., van Eck N.J. From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5233. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker N., van Es J.H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P.J., Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Flier L.G., van Gijn M.E., Hatzis P., Kujala P., Haegebarth A., Stange D.E., Begthel H., van den Born M., Guryev V., Oving I., van Es J.H., Barker N., Peters P.J., van de Wetering M., Clevers H. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell. 2009;136:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whissell G., Montagni E., Martinelli P., Hernando-Momblona X., Sevillano M., Jung P., Cortina C., Calon A., Abuli A., Castells A., Castellvi-Bel S., Nacht A.S., Sancho E., Stephan-Otto Attolini C., Vicent G.P., Real F.X., Batlle E. The transcription factor GATA6 enables self-renewal of colon adenoma stem cells by repressing BMP gene expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:695–707. doi: 10.1038/ncb2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz J., Stange D.E., Schepers A.G., van de Wetering M., Koo B.K., Itzkovitz S., Volckmann R., Kung K.S., Koster J., Radulescu S., Myant K., Versteeg R., Sansom O.J., van Es J.H., Barker N., van Oudenaarden A., Mohammed S., Heck A.J., Clevers H. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ cell markers. EMBO J. 2012;31:3079–3091. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Flier L.G., Haegebarth A., Stange D.E., van de Wetering M., Clevers H. OLFM4 is a robust marker for stem cells in human intestine and marks a subset of colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:15–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabut M., Bourdelais F., Durand S. Ribosome and translational control in stem cells. Cells. 2020;9:497. doi: 10.3390/cells9020497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolnough J.L., Atwood B.L., Liu Z., Zhao R., Giles K.E. The regulation of rRNA gene transcription during directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q., Shalaby N.A., Buszczak M. Changes in rRNA transcription influence proliferation and cell fate within a stem cell lineage. Science. 2014;343:298–301. doi: 10.1126/science.1246384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kristensen A.R., Gsponer J., Foster L.J. Protein synthesis rate is the predominant regulator of protein expression during differentiation. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:689. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu W., Liu Y., Yin H. Mitochondrial dynamics: biogenesis, fission, fusion, and mitophagy in the regulation of stem cell behaviors. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:9757201. doi: 10.1155/2019/9757201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu R., Markowetz F., Unwin R.D., Leek J.T., Airoldi E.M., MacArthur B.D., Lachmann A., Rozov R., Ma'ayan A., Boyer L.A., Troyanskaya O.G., Whetton A.D., Lemischka I.R. Systems-level dynamic analyses of fate change in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2009;462:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature08575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avansino J.R., Chen D.C., Hoagland V.D., Woolman J.D., Stelzner M. Orthotopic transplantation of intestinal mucosal organoids in rodents. Surgery. 2006;140:423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]