Highlights

-

•

In silico analysis using a total of 337 lentil protein sequences provides an extensive list of the potential allergens.

-

•

PR-10b and DRR49 showed ≥75% sequence similarity and >94% identity with the 3D epitope, thus considered strong evidence with allergenicity potential.

-

•

The proposed strategies might be beneficial to determine low allergen-containing lentil cultivars.

Keywords: In silico, Legume, Mass spectrometry, Seed proteome

Abstract

Among legumes, the lentil (Lens culinaris) is a major dietary component in many Mediterranean and Asian countries due to its high nutritional value, especially protein. However, allergic reactions triggered by lentil consumption have also been documented in many countries. Complete allergens profiling is critical for better management of lentil food allergies. Earlier studies suggested Len c 1, a 47 kDa vicilin, Len c 2, a seed-specific-biotinylated 66-kDa protein, and Len c 3, low molecular weight lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) were major allergenic proteins in lentils. Recently, mass-spectrometry-based proteomic platforms successfully identified proteins from lentil samples homologous to known plant allergens. Furthermore, in silico analysis using 337 protein sequences revealed lentil allergens that have not previously been identified as potential allergens in lentil. Herein, we discuss the feasibility of omics platforms utilized for lentil allergens profiling and quantification. In addition, we propose some future strategies that might be beneficial for profiling and development of precise assays for lentil allergens and could facilitate identification of the low allergen-containing lentil cultivars.

1. Introduction

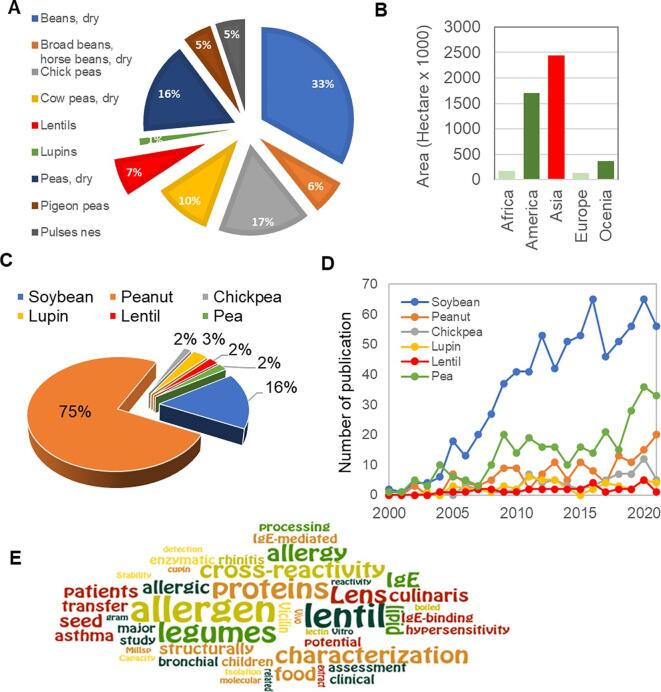

Lentil (Lens culinaris) is a legume and a rich source of protein (22–26% dry weight; Longobardi et al., 2017). Lentil is also a good source of vitamins, dietary fiber, and minerals (Ibanez et al., 2003, Longobardi et al., 2017); fat content and trans-fatty acids contents are lower than other legumes, such as chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata), lupins (Lupinus albus), faba bean (Vicia faba), and pigeon bean (Cajanus cajan) (Ene-Obong and Carnovale, 1992, Fao, 2019, Urbano et al., 2007). In 2019, around 5.7 million tons of lentils were produced around the world, wherein China, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Canada, and USA (Fig. 1A and B) were the major lentil producers (Fao, 2019, Rawal and Navarro, 2019).

Fig. 1.

Current status of lentils growth, production, and allergen research. A, Global production of lentils in comparison with other legumes in 2019. B, major lentil harvested areas in the world. C-D, a comparison of lentil and other legume research over the last 21 years (Supplementary Table 1). An individual search for each crop was performed on the NCBI website using the terms: “<crop name > allergen AND allergy” for allergy-related research articles (C), and “<crop name > proteomics” for proteomics-related articles (D). E, a word cloud (https://www.wordle.net/) of around 55 paper titles from PubMed and DOAJ databases for “lentil allergen” and associated medical subject headings (MeSH) terms (search strategy are given in Supplementary Table 2).

Although lentil is a common component of the diet in many countries, allergic reactions due to lentil consumption have been reported by many research groups (Leonardi et al., 2014, Sackesen et al., 2020, San Ireneo et al., 2008). Strong IgE-mediated hypersensitivity and immune cross-reactivities have been reported in many populations, especially in Mediterranean and Asian countries (Crespo, Pascual, Burks, Helm, & Esteban, 1995). LTPs are well-known plant allergen proteins, have also been identified in lentils (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Asero, 2011; E. Finkina et al., 2007, Shaheen et al., 2019). However, it is important to note that allergic reactions vary with race, age, and other factors (Dalal et al., 2002, Mahdavinia et al., 2021, Sasaki et al., 2020, Wollmann et al., 2015).

To date, numerous efforts have been made to identify and quantify lentil allergens. A search on the NCBI website using the keywords “legumes”, “allergen/allergy”, and “proteomics” revealed a total of 3663 research articles published in the last two decades, wherein lentil allergens (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1C) and proteome-based research (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1D) are steadily in the bottom compared to other legume species. However, a word cloud of all research papers published on lentils showed that allergen protein identification, characterization, and allergic symptoms from lentil samples were key interests (Fig. 1E). These results showed there is a lack in lentil research, particularly identification and profiling of allergens, which might be related to the incomplete protein sequences. It is important to note that precise protein sequencing, profiling, and quantification of plant allergens is challenging for non-model species using mass-spectrometry due to the availability of a publicly accessible protein sequence database (Carpentier et al., 2008). Standard methods, such as immunoblot assay for identification and quantifications of lentil allergens have been reported (Kumar et al., 2010, López-Torrejón et al., 2003, Pascual et al., 1999, Shaheen et al., 2019). Enzyme linked-immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has also been widely used for allergens research. However, this method depends on recognition of food allergens by monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies (Vidova & Spacil, 2017). These conventional methods have been successfully applied for the detection of particular allergen and quantification in various biological samples (Koeberl Clarke, & Lopata, 2014). However, there are some limitations with these antibody-based methodologies (Koeberl Clarke, & Lopata, 2014), which might be overcome with peptide-based microarray assay (Sackesen et al., 2020, Vereda et al., 2010).

Proteomic-based platforms combined with liquid chromatography and coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) have gained importance because of their accuracy, multiplexity, identification, and quantification of allergens from biological samples including lentil (López-Pedrouso et al., 2020, Scippa et al., 2010). Thus, successful application of mass spectrometry-based proteomics platforms could expand the identification and quantification of lentil allergens and pave the way to future studies. Furthermore, multiple bioinformatics-based tools have been developed that could successfully predict allergens and/or allergen-like proteins from available protein sequences (Garino et al., 2016, Gupta et al., 2013, Hall and Liceaga, 2021, Maurer-Stroh et al., 2019).

In this review, we discuss the status of lentil allergens and allergen-like proteins as well as the methods utilized for identification and quantification. Additionally, we performed in silico analysis using 337 lentil protein sequences, which provided a list of potential allergens. We also considered potential research strategies that would help to elucidate and validate detailed information for the lentil allergome as well as help to develop strategies for lentil allergy management through modifications in food systems.

2. Known lentil allergens or allergen-like proteins

According to the plant allergen database (https://www.allergome.org; https://www.allergenonline.org), a total of ten lentil allergen proteins, namely Len c, Len c 1, Len c 1.0101, Len c 1.0102, Len c 1.0103, Len c 2, Len c 2.0101, Len c 3, Len c 3.0101, and Len c Agglutinin were identified and verified (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Sánchez-Monge et al., 2000). A recent update (February 2021) of the online allergen database (https://www.allergenonline.org/) also reports three allergen protein groups from lentil along with 951 sequences. However, it is important to note that different databases may be highly redundant, and/or missing many of the recently identified allergens. The majority of known allergens in lentil seeds belong to the cupin, tryp alpha amyl, and lectin legB family (Punta et al., 2012). However, recent studies identified a number of allergens or allergen-like proteins from lentil samples (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of Lentil allergen and allergen-like proteins identified and quantified by various studies.

| Name of the allergen/ allergens like proteins | Identification Method | Quant Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin 2, Allergen Len c 1.0101 partial, Allergen Len C 1.0102 partial, Beta-lathyrin 2 partial, Chain D lentil lectin, Convicilin partial, Convicilin Precursor, CVC partial, Endochitinase, Lectin, Legumin, Legumin A, Legumin A precursor, Legumin A2, Legumin B, Legumin K, Legumin type B alpha chain precursor, LTP 2, LTP 6, Pollen specific pectin methylest, Provicilin, Seed albumin 2 partial, Storage protein, Vicilin, Vicilin 14 kDa component, Vicilin 47 K, Vicilin partial, Vicilin precursor, Vicilin type C partial, | LC-MS/MS | Label-Free | (Shaheen et al., 2019) |

| Len c 3 | Immunoblot, MALDI-TOF | – | (Akkerdaas et al., 2012) |

| Len c 1, Len c 2 | Immunoblot | – | (Sánchez-Monge et al., 2000) |

| Len c 1.0101, Len c 1.0102, Len c 1.0103, Len c 1.02 | Immunoblot, ELISA | – | (López-Torrejón et al., 2003) |

| Len c 1 | Peptide microarray immunoassay | – | (Vereda et al., 2010) |

| Len c 1 | Peptide microarray immunoassay | (Sackesen et al., 2020) | |

| Len c 1 | IgE Immunoblotting | – | (Armentia et al., 2006) |

| LTP1, LTP2, LTP3, LTP4, LTP5, LTP6, LTP7, LTP8 | Biochemical assay | – | (E. Finkina et al., 2007) |

| LTP-1, LTP-3 | ELISA | – | (Bogdanov et al., 2015) |

| Len c 1, Len c 2, Len c 3, Len c Agglutinin Proviciline, Viciline, 14 kDa component, F-box protein, ATP-dependent Clp protease, Pyruvate phosphate dikinase regulatory protein 1, Glutathione S-transferase |

1D, 2-DE Immunoblot, LC-MS/MS |

– | (Bouakkadia et al., 2015) |

| Len c 3 |

Immunoglobulin Binding Assay | – | (E. I. Finkina et al., 2020) |

| Convicilin, Len c 1.0101, Len c 1.0102, Lectin | LC-MS/MS | (Bautista-Expósito et al., 2018) | |

| Len c 1.0101, Len c 1.0102 | MALDI-TOF, LC-ESI-LIT-MS/MS | – | (Scippa et al., 2010) |

Based on the available information, lentil allergens can be grouped into four major protein families, namely convicilin, vicilin, LTP, and lectin. As expected, phylogenetic analysis with the same protein group homologs from different members of the Fabaceae family reveals close evolutionary relationships (Supplementary Fig. 1). This result is in agreement with earlier studies that showed plant allergen homologs shared highly conserved sequences (Arora et al., 2020, Verma et al., 2013).

Among the lentil allergens, Len c 1 (Len c 1.01), the earliest discovery as a major allergen, is a 50 kDa γ-vicilin chain from the cupin superfamily (López-Torrejón et al., 2003). Vicilin, also known as 7S globulins, are among the major storage proteins of legumes (Finkina et al., 2017). A total of three genetic isoforms namely Len c 1.0101, Len c 1.0102, and Len c 1.0103 have been identified. Len c 1.02 is a 12- to16-kd protein of beta-subunit of lentil vicilin protein that may be produced by the posttranslational modification of the precursor Len c 1.01 (López-Torrejón et al., 2003). On the other hand, Len c 2 protein is an IgE-binding component of a 66 kDa seed-specific biotinylated protein. It is isolated from boiled lentils (Bouakkadia et al., 2015, Sánchez-Monge et al., 2000). Len c 3, a lipid transfer protein (LTPs) is a small molecular weight protein (around 9 kDa) that belongs to the superfamily “prolamin”. A subfamily of six lentil LTP isomers designated as Lc- LTP1-6 has been identified and verified as immunologically potential allergens using immunoblot analysis and mass spectrometry-based platforms (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Asero, 2011, Bogdanov et al., 2015; E. I. Finkina et al., 2020, Shaheen et al., 2019). LTPs are considered as one of the main plant allergens that are highly cross-reactive. They can easily bind to different types of lipid molecules such as fatty acids, phospholipids, sterols, galactolipids, and lignins (Shenkarev et al., 2017). However, LTP showed a lower binding affinity to IgE proteins isolated from sera of patients with lentil allergy by heating and digestion processes (E. I. Finkina et al., 2020). Besides Len c, agglutinin (lectin) has been reported in several studies (Bouakkadia et al., 2015).

In our recent proteomic-based discovery study, we have identified a total of 44 allergens and allergen-like proteins from lentil, including Len c 1, Len c 2, Len c 3, vicilin, convicilin, legumin, lectins along with their isomers (Shaheen et al., 2019). Label-free quantitative analysis of these allergen proteins revealed that Len c 1, Len c 2, and vicilin are the most abundant allergens, whereas convicilin and Len c 3 are less abundant (Shaheen et al., 2019).

3. Methodologies for identification and quantification of lentil allergen and allergen-like proteins

Identification and characterization of allergens and allergen-like proteins from food samples is one of the key interests in the food industry. Therefore, a wide range of methodologies has been developed to characterize the allergen proteins from food samples. These methodologies are mainly established methods including DNA-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunology-based approach, and mass spectrometry-based platforms (Table 1). Herein, we briefly discuss the methods that have been utilized to identify and characterize the legumes and/or lentil allergen proteins.

3.1. PCR-based methodologies

DNA-based methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcriptomic, microarray assay, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been used for the identification and quantification of allergenic epitopes (Besler, 2001, Monaci and Visconti, 2010, Schmitt et al., 2010). Identification of allergens using a gene-based platform is an indirect method but fast and reliable (Wang et al., 2011). SNPs are also used for identifying the mutations in genes (Shaheen et al., 2019, Soo et al., 2012). The microarray-based genetic approach has not only been used to detect the legume epitope proteins, but also determine and monitor the disease profile of allergens and to establish multi-allergen tests (Flinterman et al., 2008, Harwanegg et al., 2003, Shreffler et al., 2005). Additionally, electrophoresis after the PCR assay is proposed by several authors to evaluate the amplicons (Sena-Torralba, Pallás-Tamarit, Morais, & Maquieira, 2020).

3.2. Conventional Immunology-based approach

The immunological-based approach is the basic technique for searching novel and known allergen proteins from biological samples (González-Buitrago et al., 2007). This platform is often combined with different technologies with one common thread using antibodies that recognize allergen proteins or part of these proteins (epitopes). The combination of immunochemical identification and gel electrophoresis provides a wide range of information about the level of interrogated protein, molecular weight of the protein, and its dispensation between the cellular fragments (Litovchick, 2020). Most of the known lentil allergen proteins such as Len c 1 (López-Torrejón et al., 2003), Len c 2 (Sanchez-Monge et al., 2004), and LTPs (Akkerdaas et al., 2012) have been successfully identified by the immunoblot-based approach. Currently, numerous commercial allergen strips are available as a low-cost test, which provides rapid results, ideal for quick diagnosis of many known allergen proteins (Hamid, Elfedawy, Mohamed, & Mosaad, 2009).

Similarly, ELISA is one of the most popular immunological methods where proteins are directly detected from the allergenic source (Immer & Lacorn, 2015). A recent study successfully utilized the ELISA-based method to demonstrate the allergenicity and allergen compositions of 53 Chinese peanut cultivars (Wu et al., 2016). However, the efficacy of multiple ELISA kits to detect allergen proteins from a wide range of lupines and legumes showed variable sensitivity among the samples, which relates to the cross-reactivity of the sample species (Koeberl, Clarke, & Lopata, 2014). A number of factors can determine the performance of the ELISA methods to detect food allergens (Abbott, 2010), wherein the major challenge of this method is the selection of an ideal buffer for the extraction of proteins from the food samples (Parker, 2015). Nevertheless, the application of polyclonal and/or monoclonal antibodies for detection, identification, and quantification of precise allergen proteins is still divisive (Ascoli & Aggeler, 2018).

3.3. Peptide microarray-based immunoassay

Peptide-based microarrays are similar to protein microarrays, but they have been constructed using thousands of pre-synthesized peptides on a microarray surface (Li et al., 2021). Compared to proteins, synthesized peptides are more stable, easy to produce and modify, and more importantly, less expensive. Recently, peptide-based microarrays have been successfully applied for detection and mapping of the IgE epitopes of several food allergens (Flinterman et al., 2008, Han et al., 2016, Kühne et al., 2015, Martínez-Botas and de la Hoz, 2016) including lentils (Sackesen et al., 2020, Vereda et al., 2010). Using lentil allergic patients’ serum samples, for the first time, Vereda and coworkers identified several IgE-binding sequential epitopes of Len c 1 which are in the C-terminal region (Vereda et al., 2010). Similarly, a recent work by Sackesen and coworkers also used microarray-based immunoassays to detect antibodies such as IgE and IgG4 binding to Len c 1 epitopes in the patients’ sera. The study also revealed that IgE and IgG4 binding to epitopes were significantly higher in the reactive patient than the tolerant one. However, IgE epitopes binding to Len c 1 were not detectable for all lentil allergic patients as it was not the only allergen in lentils (Sackesen et al., 2020). The peptide-based microarray technique required a low amount of human serum sample and showed higher sensitivity compared to the conventional methods. Therefore, it could be adopted as a cost-effective screening method for the identification of other lentil allergen epitopes (Kühne et al., 2015, Li et al., 2021).

3.4. Mass spectrometric-based proteomic methodologies

Recently, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based proteomic platforms have been successfully utilized and are considered a reliable method to identify and quantify plant allergen proteins (Ahsan et al., 2016, Gavage et al., 2020, López-Pedrouso et al., 2020, Nakamura and Teshima, 2013, Righetti and Boschetti, 2016, Stevenson et al., 2010, Thelen, 2009). In this section, we discuss LC-MS/MS-based proteomics platforms that have been used to identify and quantify lentil allergen proteins.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) is a well-established and widely used mass spectrometry-based method in food chemistry. MALDI-TOF has been shown to be suitable for the identification of known food contamination and allergen proteins composition during industrial production (Calvano, Bianco, Losito, & Cataldi, 2021). Earlier studies showed successful identification of known lentil allergen proteins such as Len c1 and Len c3 using immunoblot followed by MALDI-TOF analysis (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Scippa et al., 2010). However, recent advancement of LC-MS/MS-based methods mainly known as shotgun proteomics or discovery proteomics can be essential for this purpose. This platform provides highly accurate identification and quantitation of many known and unknown plant allergens and allergen-like proteins with their posttranslational modified forms (Rahman et al., 2021, Rost et al., 2020, Spiric et al., 2017). Only a handful of gel-based and/or shotgun proteomic analyses have been performed to catalogue the total proteome and allergen proteins from lentil seed samples. Thus far, only a couple hundred lentil seed proteins have been profiled using the gel-based proteomic approach (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Bouakkadia et al., 2015, Scippa et al., 2010, Shaheen et al., 2019). Most of the earlier proteomic studies successfully identified major lentil allergen proteins such as Len c1, Len c2, Len c3, proviciline, viciline, convicilin, and lectin (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Bouakkadia et al., 2015, Scippa et al., 2010). However, for the first time, in a recent study, we have identified and sequenced the isoforms of LTPs, legumins, and many other allergen-like proteins such as beta-lathyrin 2, albumin 2, endochitinase, pollen-specific pectin methylest from lentil seed using nano-LC systems coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (Shaheen et al., 2019). Taken together, these earlier studies suggest that optimization of protein extraction and sample preparation methodologies coupled with an advanced LC-MS/MS pipeline could significantly improve the sequencing depth of lentil seed proteome, thus providing identification and confirmation of many novel allergen proteins.

Targeted proteomics can be performed using technical methodologies including selected reaction monitoring (SRM), multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM), with the latter being one of the new concepts and application of mass spectrometry-based proteomics invented in the last decade (Gillet et al., 2012, Picotti and Aebersold, 2012, Picotti et al., 2009, Picotti et al., 2010). Among targeted proteomic platforms, absolute quantification (AQUA)-MRM is considered one of the most reliable for accurate protein quantitation from any biological sample (Ahsan et al., 2018, Picotti et al., 2009). The great advantage of using the targeted proteomic platform is the specific identification, and quantification of a target set of peptides and/or proteins in an MS analysis with high sensitivity, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy. Therefore, the application of targeted proteomic pipelines has rapidly increased in the last five years particularly in the field of food industry (Ahsan et al., 2016, Gavage et al., 2020). Targeted proteomic-based assays has been successfully utilized for identification and quantification of many well-known legume allergen proteins (Gavage et al., 2020, Stevenson et al., 2010). Recently, we have established the ideal peptide list of three lentil allergen proteins namely Len C1.0101, Len c 1.0102, and LTP2/4/5/6 for MRM-based assay (Shaheen et al., 2019). One of the main criteria of developing a successful MRM-based assay depends on the reproducibility of the targeted peptides in the actual biological sample (Ahsan et al., 2016). Due to the lack of a large-scale discovery proteomics dataset, the lentil seed proteome data is still fragmentary. Therefore, a great deal of discovery proteomic analysis remains to be done to develop an efficient and precise MRM-based quantitation assay for lentil allergome.

4. In silico analysis for potential lentil allergens

In silico or computational methods are widely used to determine or predict physiochemical properties such as structures and domains of a protein. The probability of a protein being allergenic can also be calculated in silico by using different algorithms and comparing the structures that are known to have allergenic properties (Garino et al., 2016, Maurer-Stroh et al., 2019). Although, in silico methodologies are incapable of distinguishing between the sensitization and elicitation phases of allergies, the FAO/WHO and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidelines state that a query protein is potentially allergenic if it has a sequence identity of>35% identical over a frame of 80 amino acids or matched exactly with 6 to 8 amino acids with an allergen (Maurer-Stroh et al., 2019).

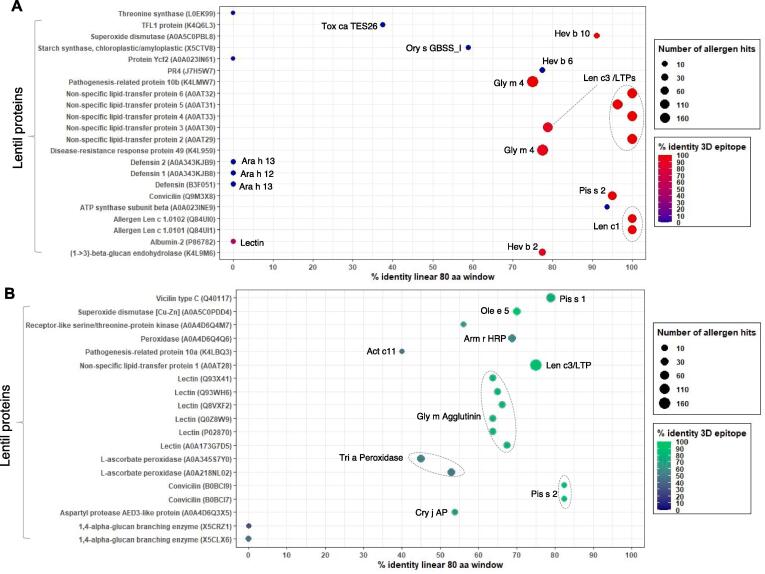

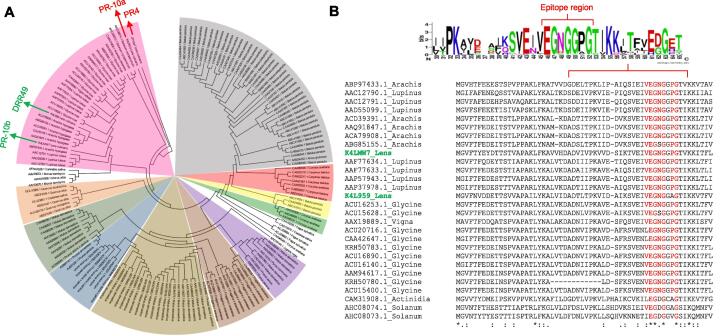

Although, in silico analysis has been successfully employed to determine the potential allergenicity of many plant proteins (Garino et al., 2016, Kulkarni et al., 2013), to the best of our knowledge, no large-scale in silico analysis has been conducted using the lentil protein database. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate a genome/proteome-based search for potential allergen-like proteins. While the complete lentil genome sequence is not publicly available, we extracted a total of 337 lentil protein sequences from the UniProt database (Taxonomic ID: 3864). These protein sequences were further subjected to AllerCatPro, an online-based pipeline to determine the allergenicity potential (Maurer-Stroh et al., 2019). Out of 337 lentil proteins analyzed, a total of 22 and 19 proteins were categorized as strong and weak allergens, respectively (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). As expected, well-characterized lentil allergens such as LTPs and Len c1 were identified with strong evidence (Fig. 2A). Two pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, namely PR4 and PR-10b, and a disease-resistance response protein 49 (DRR49) were also identified as potential new allergens with strong evidence (Fig. 2A), while PR-10a was identified with weak evidence (Fig. 2B). Among the PR proteins, PR-10b and DRR49 showed ≥ 75% sequence similarity, >94% identity with 3D epitope, and matched with 250 known allergens (Supplementary Table 2). A phylogenetic analysis of lentil PR proteins with 250 allergen hits further revealed close evolutionary relationships of PR10b and DRR49 with soybean (Glycine max), lupin (Lupinus luteus), mung bean (Vigna radiata), and peanut (Arachis hypogaea) PR proteins (Fig. 3A). Among the 250 allergens, soybean Gly m4 was the top hit against these PR-10b and DRR49 proteins (Supplementary Table 3).

Fig. 2.

In silico identification of potential lentil allergens. A total of 337 lentil protein sequences obtained from UniProt database were subjected to AllerCatPro (https://allercatpro.bii.a-star.edu.sg/). A-B, scatterplots showed 22 proteins were identified with strong evidence (A) and 19 lentil proteins were identified with weak evidence (B) as potential allergens, respectively. Detailed information can be found in supplementary table 3.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship and amino acid sequence alignment of lentil PR proteins with other allergens. A, phylogenetic tree of a total of 254 proteins including 4 lentil PR proteins and 250 homologs (allergen hits) matched with PR10b (K4LMW7) and DRR49 (K4L959). The length of the branches represents the number of substitutions per site. Gaps were eliminated using the complete deletion option. The analysis was performed using MEGA X (S. Kumar, Stecher, Li, Knyaz, & Tamura, 2018). The amino acid sequence alignment lentil, soybean, lupin, mung bean, and peanut PR proteins (pink portion in Fig. 3A). B, showed that epitope regions are highly conserved among the species. Weblogo highlights the known epitope binding residues (Ref: AllerCatPro, K4LMW7_Lens culinaris).

Amino acid sequence analysis of PR10b and DRR49 with other soybean, lupin, mung bean, and peanut PR proteins showed the epitope binding residues and region are highly conserved (Fig. 3B). It is also interesting to find out that the epitopes containing tryptic peptides of lentil PR10b and DRR49 are slightly different, suggesting a successful MRM-based targeted proteomic assay could be developed for these two potential lentil allergens (Ahsan et al., 2016).

Plant PR proteins are a known class I allergen showing strong IgE cross-reactivity (Arora et al., 2020). It is important to note that, PR proteins have never been claimed or identified as potential allergens for lentils. Nevertheless, the allergenic activity of potential allergens identified by in silico analyses need to be verified using further experimental strategies. Taken together, these results suggest that in silico analysis of the complete lentil proteome would be a potential strategy to discover many putative allergens which could help to assess the complete list of lentil allergens. Thus, food safety regulations could be evaluated more efficiently for lentils.

5. Future omics-based strategies for identification and quantification of lentil allergens

Minimal changes of allergen protein levels in food can trigger allergic reaction, a potential life-threatening condition for allergic patients (Ballmer-Weber et al., 2015). Early allergen detection and quantification methodologies improve our understanding of well-known lentil allergens. However, these conventional methodologies are unable to predict, detect, and quantify the isoform-specific allergens, multiple types of post-translational modifications in allergens, and/or less characterized allergens (Koeberl, Clarke, & Lopata, 2014). More importantly, conventional methodologies are incapable of being performed as a multiplexed system (Ahsan et al., 2016). Thus, there is great demand for developing multiplexed methodologies to identify and quantify the allergen proteins in the fresh food industry. Herein, we propose some future strategies that could be beneficial for the profiling and quantification of lentil allergome.

-

1.

In silico analysis using the complete lentil genome-derived amino acid sequences would be significantly beneficial for predicting the overall lentil allergome.

-

2.

Developing a mass-spectrometry based allergen detection and quantification assay is a key step in profiling the complete allergome (allergen and allergen likes proteins) of lentil seed. It is important to note that, earlier lentil proteomic studies (Akkerdaas et al., 2012, Bouakkadia et al., 2015, Scippa et al., 2010, Shaheen et al., 2019) using gel-based proteomics platforms identified a total of 200 proteins. Surely this number is a small portion of the lentil seed proteome. However, complementary proteomic platforms such as a combination of gel-based and gel-free proteomic platforms coupled with various protein extraction methodologies offers extensive sequencing depth of seed proteome and allergome (Bose et al., 2019, Natarajan et al., 2005, Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2014). We have demonstrated that gel-free shotgun proteomics analysis of lentil seed samples significantly increased the sequencing depth of the lentil seed proteome (unpublished). While it has already been demonstrated that the choice of protein extraction buffer enriches different protein functional classes from seed samples, systematic optimization of protein extraction is needed for in-depth profiling of the lentil seed proteome.

-

3.

A comprehensive proteome dataset combined with a thorough search against all annotated genome is necessary to identify the complete translational product (proteome) in non-model plant species(Al-Mohanna, Bokros, Ahsan, Popescu, & Popescu, 2020). Thus, a proteogenomics approach would provide a precise annotation of the lentil allergen proteins.

-

4.

Systemic proteomic screening of thousands of lentil cultivars may identify lentil cultivars with low allergenicity.

-

5.

Most of the plant allergen proteins are seed storage and defense-related proteins, therefore, the effect of geographical variation and cultural practices on lentil allergome should also be investigated.

-

6.

Processing steps could significantly influence the allergenicity of many legume seed proteins including lentils (Beyer et al., 2001, Cabanillas et al., 2018, Cuadrado et al., 2009, Mondoulet et al., 2005). Therefore, analyses of complete lentil allergome profiles in response to cooking methods (boiling, frying etc.) would be a beneficial strategy to minimize the allergic reaction to the sensitive population.

6. Conclusion

The in silico analysis revealed that the complete profiling of lentil allergome is still in the juvenile stage due to the lack of a publicly available genome sequence. Precise detection, quantification, and meaningful labeling of lentil allergen proteins could significantly mitigate the allergenic reaction of these sensitive populations and thereby, could offer better consumer safety. Thus, various omics platforms such as in silico analysis, peptide-based microarray, and mass spectrometry-based proteomics could significantly contribute to the identification and quantification of potential lentil allergens.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, N.A; data analysis and bioinformatics, N.A, F.Z.N, A.W, O.H; writing, review, and editing; N.A, O.H, N.S, S.G, A.I.C, F.Z.N, S.B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

N.A., and S.B.F. gratefully acknowledge the initial funding support from the OU VPRP Office for the establishment of the Proteomics Core Facility. N.S and O.H profoundly grateful to the HEQEP project of University Grants Commission (UGC), Bangladesh (CP-3270) and Advanced Research in Education (GARE), Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information & Statistics (BANBEIS), Ministry of Education, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh for supporting the establishment of laboratory facilities for the analysis of food allergens in INFS.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochms.2022.100109.

Contributor Information

Nazma Shaheen, Email: nazmashaheen@du.ac.bd.

Nagib Ahsan, Email: nahsan@ou.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abbott M. Validation procedures for quantitative food allergen ELISA methods: Community guidance and best practices. Journal of AOAC International. 2010:442–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan N., Rao R.S.P., Gruppuso P.A., Ramratnam B., Salomon A.R. Targeted proteomics: Current status and future perspectives for quantification of food allergens. Journal of Proteomics. 2016;143:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan N., Wilson R.S., Thelen J.J. Absolute quantitation of plant proteins. Current Protocols in Plant Biology. 2018;3(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/cppb.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkerdaas J., Finkina E., Balandin S., Magadán S.S., Knulst A., Fernandez-Rivas M.…Ovchinnikova T. Lentil (Lens culinaris) lipid transfer protein Len c 3: A novel legume allergen. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2012;157(1):51–57. doi: 10.1159/000324946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohanna T., Bokros N.T., Ahsan N., Popescu G.V., Popescu S.C. Plant proteomics. Springer; 2020. Methods for Optimization of Protein Extraction and Proteogenomic Mapping in Sweet Potato; pp. 309–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armentia A., Lombardero M., Blanco C., Fernández S., Fernández A., Sánchez-Monge R. Allergic hypersensitivity to the lentil pest Bruchus lentis. Allergy. 2006;61(9):1112–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R., Kumar A., Singh I.K., Singh A. Pathogenesis related proteins: A defensin for plants but an allergen for humans. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;157:659–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli C.A., Aggeler B. Overlooked benefits of using polyclonal antibodies. BioTechniques. 2018;65(3):127–136. doi: 10.2144/btn-2018-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asero R. 7 lipid transfer protein cross-reactivity assessed in vivo and in vitro in the office: pros and cons. Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology. 2011;21(2):129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballmer-Weber B.K., Fernandez-Rivas M., Beyer K., Defernez M., Sperrin M., Mackie A.R.…Belohlavkova S. How much is too much? Threshold dose distributions for 5 food allergens. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015;135(4):964–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Expósito S., Peñas E., Dueñas M., Silván J.M., Frias J., Martínez-Villaluenga C. Individual contributions of Savinase and Lactobacillus plantarum to lentil functionalization during alkaline pH-controlled fermentation. Food Chemistry. 2018;257:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besler M. Determination of allergens in foods. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2001;20(11):662–672. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K., Morrowa E., Li X.-M., Bardina L., Bannon G.A., Burks A.W., Sampson H.A. Effects of cooking methods on peanut allergenicity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2001;107(6):1077–1081. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, I., Finkina, E., Balandin, S., Melnikova, D., Stukacheva, E., & Ovchinnikova, T. (2015). Structural and functional characterization of recombinant isoforms of the lentil lipid transfer protein. Acta Naturae (aнглoязычнaя вepcия), 7(3 (26)). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bose U., Broadbent J.A., Byrne K., Hasan S., Howitt C.A., Colgrave M.L. Optimisation of protein extraction for in-depth profiling of the cereal grain proteome. Journal of Proteomics. 2019;197:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouakkadia H., Boutebba A., Haddad I., Vinh J., Guilloux L., Sutra J.-P.…Poncet P. Paper presented at the Annales de biologie clinique. 2015. Immunoproteomics of non water-soluble allergens from 4 legumes flours: Peanut, soybean, sesame and lentil. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas B., Jappe U., Novak N. Allergy to peanut, soybean, and other legumes: Recent advances in allergen characterization, stability to processing and IgE cross-reactivity. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2018;62(1):1700446. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvano, C. D., Bianco, M., Losito, I., & Cataldi, T. R. (2021). Proteomic Analysisof Food Allergens by MALDI TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometry. In: Protein Downstream Processing (pp. 357-376): Springer. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carpentier S.C., Panis B., Vertommen A., Swennen R., Sergeant K., Renaut J.…Devreese B. Proteome analysis of non-model plants: A challenging but powerful approach. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2008;27(4):354–377. doi: 10.1002/mas.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo J., Pascual C., Burks A., Helm R., Esteban M.M. Frequency of food allergy in a pediatric population from Spain. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 1995;6(1):39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1995.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado C., Cabanillas B., Pedrosa M.M., Varela A., Guillamón E., Muzquiz M.…Burbano C. Influence of thermal processing on IgE reactivity to lentil and chickpea proteins. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2009;53(11):1462–1468. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal H., Binson I., Reifen R., Ballin A., Somekh E. Sesame as a major cause of severe IgE-mediated food allergic reactions among infants and children in Israel. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109(1):S217. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2002.1s3412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ene-Obong H., Carnovale E. A comparison of the proximate, mineral and amino acid composition of some known and lesser known legumes in Nigeria. Food Chemistry. 1992;43(3):169–175. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. (2019). Faostat, Fao Statistical Database. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org.

- Finkina E., Balandin S., Serebryakova M., Potapenko N., Tagaev A., Ovchinnikova T. Purification and primary structure of novel lipid transfer proteins from germinated lentil (Lens culinaris) seeds. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2007;72(4):430–438. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkina E.I., Melnikova D.N., Bogdanov I.V., Matveevskaya N.S., Ignatova A.A., Toropygin I.Y., Ovchinnikova T.V. Impact of Different Lipid Ligands on the Stability and IgE-Binding Capacity of the Lentil Allergen Len c 3. Biomolecules. 2020;10(12):1668. doi: 10.3390/biom10121668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinterman, A. E., Knol, E. F., Lencer, D. A., Bardina, L., den Hartog Jager, C. F., Lin, J., . . . van Hoffen, E. (2008). Peanut epitopes for IgE and IgG4 in peanut-sensitized children in relation to severity of peanut allergy. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 121(3), 737-743. e710. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garino C., Coïsson J.D., Arlorio M. In silico allergenicity prediction of several lipid transfer proteins. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2016;60:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavage M., Van Vlierberghe K., Van Poucke C., De Loose M., Gevaert K., Dieu M.…Gillard N. Comparative study of concatemer efficiency as an isotope-labelled internal standard for allergen quantification. Food Chemistry. 2020;332 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet L.C., Navarro P., Tate S., Röst H., Selevsek N., Reiter L.…Aebersold R. Targeted data extraction of the MS/MS spectra generated by data-independent acquisition: A new concept for consistent and accurate proteome analysis. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2012;11(6) doi: 10.1074/mcp.O111.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Buitrago J.M., Ferreira L., Isidoro-García M., Sanz C., Lorente F., Dávila I. Proteomic approaches for identifying new allergens and diagnosing allergic diseases. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2007:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S., Kapoor, P., Chaudhary, K., Gautam, A., Kumar, R., Consortium, O. S. D. D., & Raghava, G. P. (2013). In silico approach for predicting toxicity of peptides and proteins. PLoS One, 8(9), e73957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hall F.G., Liceaga A.M. Isolation and proteomic characterization of tropomyosin extracted from edible insect protein. Food Chemistry: Molecular Sciences. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.fochms.2021.100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid O.A., Elfedawy S., Mohamed S.K., Mosaad H. Immunoblotting technique: A new accurate in vitro test for detection of allergen-specific IgE in allergic rhinitis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology. 2009;266(10):1569–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Lin J., Bardina L., Grishina G.A., Lee C., Seo W.H., Sampson H.A. What characteristics confer proteins the ability to induce allergic responses? IgE epitope mapping and comparison of the structure of soybean 2S albumins and ara h 2. Molecules. 2016;21(5):622. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwanegg C., Laffer S., Hiller R., Mueller M., Kraft D., Spitzauer S., Valenta R. Microarrayed recombinant allergens for diagnosis of allergy. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2003;33(1):7–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- I Finkina, E., N Melnikova, D., V Bogdanov, I., & V Ovchinnikova, T. (2017). Plant pathogenesis-related proteins PR-10 and PR-14 as components of innate immunity system and ubiquitous allergens. Current medicinal chemistry, 24(17), 1772-1787. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ibanez M., Martinez M., Sanchez J., Fernández-Caldas E. Legume cross-reactivity. Allergologia et Immunopathologia. 2003;31(3):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immer U., Lacorn M. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for detecting allergens in food. Elsevier; 2015. pp. 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Koeberl M., Clarke D., Lopata A.L. Next generation of food allergen quantification using mass spectrometric systems. Journal of Proteome Research. 2014;13(8):3499–3509. doi: 10.1021/pr500247r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne Y., Reese G., Ballmer-Weber B.K., Niggemann B., Hanschmann K.-M., Vieths S., Holzhauser T. A novel multipeptide microarray for the specific and sensitive mapping of linear IgE-binding epitopes of food allergens. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 2015;166(3):213–224. doi: 10.1159/000381344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A., Ananthanarayan L., Raman K. Identification of putative and potential cross-reactive chickpea (Cicer arietinum) allergens through an in silico approach. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2013;47:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Kumari D., Srivastava P., Khare V., Fakhr H., Arora N.…Singh B. Identification of IgE-mediated food allergy and allergens in older children and adults with asthma and allergic rhinitis. The Indian Journal of Chest Diseases & Allied Sciences. 2010;52(4):217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2018;35(6):1547. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi S., Pecoraro R., Filippelli M., Miraglia del Giudice M., Marseglia G., Salpietro C.…La Rosa M. Paper presented at the Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014. Allergic reactions to foods by inhalation in children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Song G., Bai Y., Song N., Zhao J., Liu J., Hu C. Applications of Protein Microarrays in Biomarker Discovery for Autoimmune Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.645632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovchick, L. (2020). Immunoblotting. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols, pdb--top098392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, F., Innamorato, V., Di Gioia, A., Ventrella, A., Lippolis, V., Logrieco, A. F., . . . Agostiano, A. (2017). Geographical origin discrimination of lentils (Lens culinaris Medik.) using 1H NMR fingerprinting and multivariate statistical analyses. Food Chemistry, 237, 743-748. [DOI] [PubMed]

- López-Pedrouso M., Lorenzo J.M., Gagaoua M., Franco D. Current trends in proteomic advances for food allergen analysis. Biology. 2020;9(9):247. doi: 10.3390/biology9090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Torrejón G., Salcedo G., Martín-Esteban M., Díaz-Perales A., Pascual C.Y., Sánchez-Monge R. Len c 1, a major allergen and vicilin from lentil seeds: Protein isolation and cDNA cloning. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2003;112(6):1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavinia, M., Tobin, M. C., Fierstein, J. L., Andy-Nweye, A. B., Bilaver, L. A., Fox, S., . . . Chura, A. (2021). African American Children Are More Likely to Be Allergic to Shellfish and Finfish: Findings from FORWARD, a Multisite Cohort Study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Botas J., de la Hoz B. Peptide Microarrays. Springer; 2016. IgE and IgG4 epitope mapping of food allergens with a peptide microarray immunoassay; pp. 235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S., Krutz N.L., Kern P.S., Gunalan V., Nguyen M.N., Limviphuvadh V.…Gerberick G.F. AllerCatPro—prediction of protein allergenicity potential from the protein sequence. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(17):3020–3027. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaci L., Visconti A. Immunochemical and DNA-based methods in food allergen analysis and quality assurance perspectives. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2010;21(6):272–283. [Google Scholar]

- Mondoulet L., Paty E., Drumare M., Ah-Leung S., Scheinmann P., Willemot R.…Bernard H. Influence of thermal processing on the allergenicity of peanut proteins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005;53(11):4547–4553. doi: 10.1021/jf050091p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R., Teshima R. Proteomics-based allergen analysis in plants. Journal of Proteomics. 2013;93:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan S., Xu C., Caperna T.J., Garrett W.M. Comparison of protein solubilization methods suitable for proteomic analysis of soybean seed proteins. Analytical Biochemistry. 2005;342(2):214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C.H. Multi-allergen quantitation and the impact of thermal treatment in industry-processed baked goods by ELISA and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2015:10669–10680. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual C.Y., Fernandez-Crespo J., Sanchez-Pastor S., Padial M.A., Diaz-Pena J.M., Martin-Muñoz F., Martin-Esteban M. Allergy to lentils in Mediterranean pediatric patients. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999;103(1):154–158. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70539-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picotti P., Aebersold R. Selected reaction monitoring–based proteomics: Workflows, potential, pitfalls and future directions. Nature Methods. 2012;9(6):555–566. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picotti P., Bodenmiller B., Mueller L.N., Domon B., Aebersold R. Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell. 2009;138(4):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picotti P., Rinner O., Stallmach R., Dautel F., Farrah T., Domon B.…Aebersold R. High-throughput generation of selected reaction-monitoring assays for proteins and proteomes. Nature Methods. 2010;7(1):43–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M., Coggill P.C., Eberhardt R.Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C.…Clements J. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(D1):D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Guo Q., Baten A., Mauleon R., Khatun A., Liu L., Barkla B.J. Shotgun proteomics of Brassica rapa seed proteins identifies vicilin as a major seed storage protein in the mature seed. PloS one. 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawal V., Navarro D. Rome, Italy; FAO: 2019. The global economy of pulses; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Righetti P.G., Boschetti E. Global proteome analysis in plants by means of peptide libraries and applications. Journal of Proteomics. 2016;143:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Rodríguez, M. C., Maldonado-Alconada, A. M., Valledor, L., & Jorrin-Novo, J. V. (2014). Back to Osborne. Sequential protein extraction and LC-MS analysis for the characterization of the Holm oak seed proteome. Plant proteomics, 379-389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rost J., Muralidharan S., Lee N.A. A label-free shotgun proteomics analysis of macadamia nut. Food Research International. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackesen C., Erman B., Gimenez G., Grishina G., Yilmaz O., Yavuz S.T.…Cavkaytar O. IgE and IgG4 binding to lentil epitopes in children with red and green lentil allergy. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2020;31(2):158–166. doi: 10.1111/pai.13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Ireneo M.M., Ibáñez M.D., Sánchez J.-J., Carnés J., Fernández-Caldas E. Clinical features of legume allergy in children from a Mediterranean area. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2008;101(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Monge R., Pascual C.Y., Díaz-Perales A., Fernández-Crespo J., Martín-Esteban M., Salcedo G. Isolation and characterization of relevant allergens from boiled lentils. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000;106(5):955–961. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Monge R., Lopez-Torrejón G., Pascual C., Varela J., Martin-Esteban M., Salcedo G. Vicilin and convicilin are potential major allergens from pea. Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 2004;34(11):1747–1753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M., Morikawa E., Yoshida K., Fukutomi Y., Adachi Y., Odajima H., Akasawa A. The prevalence of oral symptoms caused by Rosaceae fruits and soybean consumption in children; a Japanese population-based survey. Allergology International. 2020;69(4):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D.A., Nesbit J.B., Hurlburt B.K., Cheng H., Maleki S.J. Processing can alter the properties of peanut extract preparations. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(2):1138–1143. doi: 10.1021/jf902694j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scippa G.S., Rocco M., Ialicicco M., Trupiano D., Viscosi V., Di Michele M.…Scaloni A. The proteome of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) seeds: Discriminating between landraces. Electrophoresis. 2010;31(3):497–506. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Torralba A., Pallás-Tamarit Y., Morais S., Maquieira Á. Recent advances and challenges in food-borne allergen detection. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2020;116050 [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen N., Halima O., Akhter K.T., Nuzhat N., Rao R.S.P., Wilson R.S., Ahsan N. Proteomic characterization of low molecular weight allergens and putative allergen proteins in lentil (Lens culinaris) cultivars of Bangladesh. Food Chemistry. 2019;297 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenkarev Z.O., Melnikova D.N., Finkina E.I., Sukhanov S.V., Boldyrev I.A., Gizatullina A.K.…Ovchinnikova T.V. Ligand binding properties of the lentil lipid transfer protein: Molecular insight into the possible mechanism of lipid uptake. Biochemistry. 2017;56(12):1785–1796. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreffler W.G., Lencer D.A., Bardina L., Sampson H.A. IgE and IgG4 epitope mapping by microarray immunoassay reveals the diversity of immune response to the peanut allergen, Ara h 2. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2005;116(4):893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo, L. Y., Walczyk, N. E., & Smith, P. M. (2012). Using genome-enabled technologies to address allergens in seeds of crop plants: legumes as a case study. In: Seed Development: OMICS Technologies toward Improvement of Seed Quality and Crop Yield (pp. 503-525): Springer.

- Spiric J., Schulenborg T., Schwaben L., Engin A.M., Karas M., Reuter A. Model for quality control of allergen products with mass spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research. 2017;16(10):3852–3862. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson S.E., Houston N.L., Thelen J.J. Evolution of seed allergen quantification–from antibodies to mass spectrometry. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2010;58(3):S36–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen J.J. Proteomics tools and resources for investigating protein allergens in oilseeds. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2009;54(3):S41–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, G., Porres, J. M., Frías, J., & Vidal-Valverde, C. (2007). Nutritional value. In: Lentil (pp. 47-93): Springer.

- Vereda, A., Andreae, D. A., Lin, J., Shreffler, W. G., Ibañez, M. D., Cuesta-Herranz, J., . . . Sampson, H. A. (2010). Identification of IgE sequential epitopes of lentil (Len c 1) by means of peptide microarray immunoassay. Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 126(3), 596-601. e591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Verma A.K., Kumar S., Das M., Dwivedi P.D. A comprehensive review of legume allergy. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2013;45(1):30–46. doi: 10.1007/s12016-012-8310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidova V., Spacil Z. A review on mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics: Targeted and data independent acquisition. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2017;964:7–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Han J., Wu Y., Yuan F., Chen Y., Ge Y. Simultaneous detection of eight food allergens using optical thin-film biosensor chips. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011;59(13):6889–6894. doi: 10.1021/jf200933b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollmann E., Hamsten C., Sibanda E., Ochome M., Focke-Tejkl M., Asarnoj A.…Lupinek C. Natural clinical tolerance to peanut in African patients is caused by poor allergenic activity of peanut IgE. Allergy. 2015;70(6):638–652. doi: 10.1111/all.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Zhou N., Xiong F., Li X., Yang A., Tong P.…Chen H. Allergen composition analysis and allergenicity assessment of Chinese peanut cultivars. Food Chemistry. 2016;196:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.