Abstract

β-Sulfonyl carboxamides have been proposed to serve as transition-state analogues of the β-ketoacyl synthase reaction involved in fatty acid elongation. We tested the efficacy of N-octanesulfonylacetamide (OSA) as an inhibitor of fatty acid and mycolic acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Using the BACTEC radiometric growth system, we observed that OSA inhibits the growth of several species of slow-growing mycobacteria, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37Rv and clinical isolates), the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Mycobacterium bovis BCG, Mycobacterium kansasii, and others. Nearly all species and strains tested, including isoniazid and multidrug resistant isolates of M. tuberculosis, were susceptible to OSA, with MICs ranging from 6.25 to 12.5 μg/ml. Only three clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis (CSU93, OT2724, and 401296), MAC, and Mycobacterium paratuberculosis required an OSA MIC higher than 25.0 μg/ml. Rapid-growing mycobacterial species, such as Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and others, were not susceptible at concentrations of up to 100 μg/ml. A 2-dimensional thin-layer chromatography system showed that OSA treatment resulted in a significant decrease in all species of mycolic acids present in BCG. In contrast, mycolic acids in M. smegmatis were relatively unaffected following exposure to OSA. Other lipids, including polar and nonpolar extractable classes, were unchanged following exposure to OSA in both BCG and M. smegmatis. Transmission electron microscopy of OSA-treated BCG cells revealed a disruption in cell wall synthesis and incomplete septum formation. Our results indicate that OSA inhibits the growth of several species of mycobacteria, including both isoniazid-resistant and multidrug resistant strains of M. tuberculosis. This inhibition may be the result of OSA-mediated effects on mycolic acid synthesis in slow-growing mycobacteria or inhibition via an undescribed mechanism. Our results indicate that OSA may serve as a promising lead compound for future antituberculous drug development.

Tuberculosis continues to be the leading cause of death worldwide due to an infectious agent (8). Approximately 8 million new active cases arise each year, with about 3 million deaths (8). Of equivalent concern has been the emergence of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. As a result, newly infected individuals no longer have the assurance that prophylaxis with isoniazid (INH) will eliminate infection or that active disease will be treatable with our current arsenal of drugs. In addition, therapies for the treatment of atypical mycobacterial infections in immunocompromised patients are limited (24). Thus, the development of new drugs is essential in combating both drug resistant M. tuberculosis and opportunistic infections with atypical mycobacteria, such as the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC).

Potential new targets for antimycobacterial drug development may exist among the synthetic enzymes needed to make the unique lipids produced by mycobacteria, such as mycolic acids. These high-molecular-weight, α-alkyl, β-hydroxy fatty acids comprise the single largest component of the mycobacterial cell envelope (3, 4, 9, 10, 29, 30, 37). They are found in free lipids as trehalose mono- and dimycolate and esterified to the arabinogalactan matrix of the mycobacterial cell wall (5, 10). They are vital for the growth and survival of mycobacteria, as evidenced by the bactericidal properties of mycolic acid inhibitory drugs, such as isoniazid and ethionamide (1, 2, 32, 33, 43, 44, 47, 48, 51, 53–58).

Synthesis of mycolic acids and other mycobacterial lipids requires a variety of fatty acid synthase and elongation enzymes (7, 10, 23). Although the synthesis of fatty acids is essentially the same at the primary chemical level, fatty acid synthases (FAS) are organized into two types. In Type I FAS (FAS I), most often found in eukaryotes, the individual enzymatic reactions are contained in one multienzyme complex. In Type II FAS (FAS II), commonly found in prokaryotes, the enzyme functions are carried out by seven individual proteins. Mycobacteria are known to possess both FAS I and II (6, 7, 23). Thus, inhibition of these enzymes, especially those involved in chain elongation of unique mycobacterial fatty acids, may provide novel targets for drug design.

In the past, characterization of FAS has been aided through the use of two natural product inhibitors of FAS components, cerulenin and thiolactomycin (15, 16, 36, 39–42, 46). Cerulenin is a potent inhibitor of both FAS I and FAS II systems while thiolactomycin inhibits only synthases of the FAS II variety. Activity of both of these inhibitors on the mycolic acids of mycobacteria has recently been described (25, 42, 50). Although cerulenin and thiolactomycin are structurally different, both compounds inhibit the two-carbon homologation catalyzed by the β-ketoacyl synthase, the condensing enzyme required for fatty acid biosynthesis. Specifically, cerulenin irreversibly inhibits the β-ketoacyl synthase (20, 39, 40), while thiolactomycin inhibits both the β-ketoacyl–acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthase and acetyl coenzyme A:ACP transacylase (15). β-Sulfonyl carboxamides were designed to mimic the transition state of the reaction catalyzed by the β-ketoacyl synthase. In the following study we evaluated the in vitro activity of one of these compounds, N-octanesulfonylacetamide (OSA), on a variety of mycobacteria and specifically evaluated its effects on lipid and mycolic acid synthesis in Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium smegmatis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

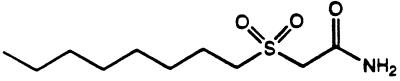

Synthesis of OSA.

The synthesis of alkyl sulfoxides and sulfones has been described previously (22). Briefly, OSA was synthesized in three steps from commercially available materials. Octyl bromide and methyl thioglycolate were reacted together to yield methyl 3-thioundecanoate. This sulfide was then oxidized to the sulfoxide by using 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid. OSA was obtained from the ammonylysis of the methyl ester. Overall yield was 70% following crystallization of the final product (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Structure of OSA.

Mycobacteria.

M. tuberculosis strains H37Rv and CSU93 (52), M. bovis (ATCC 35734), M. bovis BCG (Pasteur strain, ATCC 35734), Mycobacterium kansasii (ATCC 12478), Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (ATCC 19698), and M. smegmatis (mc2 6 1-2c) (53) were utilized as reference strains. Clinical and other isolates were speciated using standard methods (38) and included MAC, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonei, Mycobacterium abscessus, and both INH- and multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis.

Susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility testing and determination of MICs for M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. kansasii, and M. bovis BCG were done using the BACTEC radiometric growth system (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) and a standardized method (42, 49). Initial stock solutions (1 mg/ml) and subsequent dilutions of OSA, cerulenin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and thiolactomycin (generously provided by T. Yoshida) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma). A modification of this procedure adopted by The National Jewish Center for Immunology and Respiratory Medicine was used to determine MICs for MAC (17). Susceptibility testing of M. paratuberculosis was accomplished by varying the standard BACTEC protocol to include the addition of mycobactin J (Allied Monitor, Fayette, Mo.) to commercially prepared 12B media (Becton Dickinson). Initial mycobactin J solutions (2 mg/ml) were brought up in 95% ethanol and diluted in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 40 μg/ml. Mycobactin J was then added to each BACTEC vial (final concentration = 1.0 μg/ml) along with OSA. All primary drugs were purchased from Becton Dickinson. Susceptibilities and MIC determinations of specific inhibitors for M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. chelonei, and M. abscessus were established by broth dilution using Middlebrook 7H9-ADC incubated at 37°C for 4 days.

Treatment of cultures with OSA and lipid pulse labeling.

BCG and MAC cells were grown in M7H9-ADC-Tween (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) to early log phase. From this, a 1.0 McFarland suspension was prepared and diluted to yield a final concentration of 3 × 107 cells/ml in a total volume of 50 ml in M7H9-ADC-Tween. Cultures were aerated and incubated at 37°C for 24 h (approximately 1 generation time). Each inhibitor was added at its MIC (final concentrations: thiolactomycin, 25.0 μg/ml [BCG] and 75.0 μg/ml [M. smegmatis]; OSA, 6.25 μg/ml [BCG], 25.0 μg/ml [MAC], and 100 μg/ml [M. smegmatis]), and cultures were incubated under the same conditions for approximately 1 generation time (BCG and MAC, approximately 24 h; M. smegmatis, approximately 5 h). Subsequently, 1 μCi of [1,2-14C]acetic acid (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.)/ml was added and the cultures were incubated as before for an additional 24 h. In order to demonstrate a concentration-dependent effect of OSA on mycolic acid synthesis in BCG, lipid pulse labeling was also performed at OSA concentrations of 12.5 and 25.0 μg/ml. A slight variation of this protocol was used for labeling in M. smegmatis cells. Since this species of mycobacteria was not susceptible to OSA, the highest concentration tested (100 μg/ml) in this study was used for labeling purposes. Additionally, a 0.5 McFarland suspension was done with an initial incubation time of 10 h prior to the addition of compound and subsequent incubations of 5 h each (based on a doubling time of 3 to 5 h) following the addition of drug and label, respectively. All assays were performed in duplicate.

Preparation of extractable mycobacterial lipids.

Extractions were performed as previously described (13, 34, 42). Briefly, 100 to 150 mg (wet weight) of cells was suspended in methanolic saline (methanol–0.3% aqueous NaCl [100:10, vol/vol] [2 ml]) and extracted three times with petroleum ether, yielding nonpolar extractable lipids. The remaining cells and residual aqueous phase were boiled for 5 min, cooled for 5 min at 37°C, and extracted with monophasic chloroform–methanol–0.3% NaCl (90:100:30, vol/vol; used once) and chloroform–methanol–0.3% NaCl (50:100:40, vol/vol; used twice). All extracts were subsequently dried under N2 at room temperature. The defatted cells containing saponifiable lipids were saved.

Mycolic acid extraction and preparation of MAMES and FAMES.

Extractions of mycobacterial mycolic acids were performed as previously described (13, 35, 42). Briefly, 50-ml cultures of M. smegmatis, BCG, or MAC cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min. Equal volumes of cells (100 to 150 mg [wet weight]) were extracted to remove polar and nonpolar extractable lipids (13, 42). The resulting defatted cells containing bound mycolic acids and other saponifiable lipids were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis in methanol (1 ml), 30% KOH (1 ml), and toluene (0.1 ml) at 75°C overnight and subsequently cooled to room temperature (13, 42). The mixture was then acidified to pH 1 with 3.6% HCl and extracted three times with diethyl ether. Combined extracts were dried under N2. Mycolic acid methyl esters (MAMES) and other long-chain fatty acids (fatty acid methyl esters [FAMES]) were prepared by mixing dichloromethane (1 ml), a catalyst solution (1 ml) (14), and iodomethane (25 ml) for 30 min; centrifuging; and discarding the upper phase. The lower phase was dried under N2.

[1,2-14C]acetate incorporation into mycobacterial lipids.

Incorporation of [1,2-14C]acetate into polar and nonpolar extractable and saponifiable lipid fractions was determined by scintillation counting and expressed in counts per minute (cpm) (Beckman LS6500 multi-purpose scintillation counter).

Analysis of MAMES and FAMES.

Mycobacterial saponifiable extracts containing MAMES and FAMES were dissolved in chloroform and equal counts (in counts per minute) of each sample were loaded onto thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (20- by 20-cm silica gel G, 250-μm-diamter analytical plates; Analtech, Newark, Del.). Samples were subsequently subjected to a 2-dimensional solvent system (petroleum ether [bp 60 to 80°C]–acetone [95:5, vol/vol]) in the first dimension [three times] and toluene-acetone [97:3, vol/vol] in the second dimension [one time]).

Data analysis.

Mycolic acids of each species of mycobacteria were identified according to methods described by Dobson et al. (13, 42). Visualization and comparison of thin-layer chromatograms were done using a Fuji Systems (Fujix BAS 1000) phosphorimager. Spots were quantified using NIH Image (version 1.57; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.) software programs. Due to the nonequivalency of the counts per minute as determined by scintillation counting and phosphor counts as determined by phosphorimaging, relative intensities of chromatographed compounds were calculated for each TLC plate on the basis of total number of phosphor counts per plate. Phosphor counts for MAMES and FAMES were normalized for each TLC plate pair (control and inhibitor treated). The difference in normalized phosphor counts between each control and inhibitor treated pair represents the percent change.

Electron microscopy.

All chemicals and reagents for electron microscopy were obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences, Ft. Washington, Pa. Cultures (50 ml) of BCG were grown to early log phase (optical density at 600 nm, ∼0.2), at which time OSA (100 μg/ml) or diluent (dimethyl sulfoxide) was added to treated and control cultures, followed by additional aeration and incubation at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were harvested by low-speed centrifugation and washed in 0.1 M cacodylate (CACO) buffer (pH 7.3). Washed cells were then fixed in 0.1 M CACO buffer (pH 7.3) containing 2.0% glutaraldehyde–osmium tetroxide (1:1, vol/vol) for 45 min at 4°C (11, 28, 45). Secondary fixation was done at 4°C overnight in 4.0% formaldehyde–1.0% glutaraldehyde. Samples were post-fixed at room temperature for 1 h in 0.1 M CACO buffer containing 1% tannic acid and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series of 50, 70, 95 (twice), and 100% (three times). Subsequently, samples were infiltrated at room temperature with a series of Spurrs resins (Spurrs-ethanol [1:1, vol/vol; 2 h], Spurrs-ethanol [2:1, vol/vol; 2 h], and pure Spurrs [overnight]), and blocks were polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. Sections were cut on a Sorvall MT2B microtome, and 80-nm-thick sections were picked up on 200-mesh copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Prepared samples were then analyzed on a Hitachi HU12A electron microscope.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibilities.

Tables 1 and 2 show the susceptibility of various mycobacterial species and strains to OSA using the BACTEC radiometric growth system. Nearly all strains of M. tuberculosis and other slow-growing mycobacterial species, such as M. bovis, M. bovis BCG, and M. kansasii, were susceptible to OSA, with MICs ranging from 6.25 to 12.5 μg/ml. Only three clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis (CSU 93, 42-1C9383, and 10129-3), the MAC, and M. paratuberculosis required a higher OSA MIC of 25 μg/ml. None of the rapid-growing mycobacterial species tested, M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, M. chelonei, and M. abscessus, were susceptible to OSA at concentrations up to 100 μg/ml. Resistance to known antimycobacterial agents did not give cross-resistance to OSA. Three clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis, resistant to either INH alone or INH plus rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, and pyrazinamide (19), were found to be susceptible to OSA, with MICs of 12.5 and 6.25 μg/ml, respectively. Similar results were obtained for cerulenin as previously reported (42). BCG and M. smegmatis were susceptible to thiolactomycin at a MIC of 25 and 75 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of different species of mycobacteria to OSA

| Organism | MIC (μg/ml) of OSA |

|---|---|

| M. bovis | 6.25 |

| M. bovis BCG | 6.25 |

| M. kansasii | 12.5 |

| M. avium complex | 25.0 |

| M. paratuberculosis | 25.0 |

| M. smegmatis | >100 |

| M. fortuitum | >100 |

| M. chelonei | >100 |

| M. abscessus | >100 |

TABLE 2.

Activities of OSA and first-line antimycobacterial drugs against various strains of M. tuberculosisa

| M. tuberculosis strain | INH

|

RIF (2.0 μg/ml) | EMB (2.0 μg/ml) | STR (2.0 μg/ml) | PZA (100 μg/ml) | OSA

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 μg/ml | 0.4 μg/ml | 6.25 μg/ml | 12.5 μg/ml | 25.0 μg/ml | |||||

| H37Rv | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 5D5178 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 1D4924 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 1H1337 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 42401315 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 6T2709 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| 1T2768 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| TBL54 EP066 | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | S | S |

| 7D5245 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| OT2769 | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S |

| 42-1C9383 | R | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | S |

| 10129-3 | R | R | S | S | S | S | R | S | S |

| CSU93 | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S |

| OT2724 | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S |

| 401296 | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | R | S |

S, susceptible; R, resistant; RIF, rifampin; EMB, ethambutol; STR, streptomycin; PZA, pyrazinamide.

Overall effects of OSA on mycobacterial lipids.

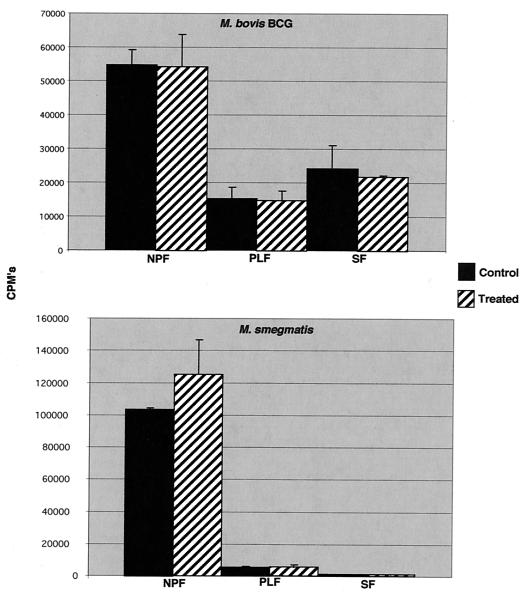

Labeling assays were conducted at the calculated MIC (6.25 μg/ml) of OSA for BCG and at the highest concentration of compound tested for M. smegmatis. This particular concentration of OSA is not equivalent to the lethal concentration of compound in mycobacteria, as evidenced by continued 14CO2 production in the radiometric susceptibility test system, which indicated continued metabolism, albeit at a reduced level relative to those of controls. OSA had no significant effect on [14C]acetate incorporation into nonpolar extractable or polar extractable lipids at a concentration of 6.25 μg/ml, the calculated MIC for M. bovis BCG, or 100 μg/ml for M. smegmatis (Fig. 2). A moderate decrease in the incorporation of label was observed in saponifiable lipids in OSA-treated BCG. However, this change was not statistically significant. Label incorporation into the same lipid fraction in M. smegmatis was unaltered by exposure to OSA (Fig. 2). In order to demonstrate a concentration-dependent effect of OSA on lipid metabolism, studies were run at 12.5 μg/ml (two times the MIC) and 25.0 μg/ml (four times the MIC). At these higher concentrations, there was a dose-dependent decrease of label incorporation in the saponifiable lipid fraction with a concomitant increase of label in the nonpolar extractable fraction (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effects of OSA on the synthesis of various lipid fractions in M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Incorporation of [1,2-14C]acetate into extractable polar, nonpolar, and saponifiable lipids in the presence and absence of OSA. Abbreviations: NPF, nonpolar extractable lipids; PLF, polar extractable lipids; SF, saponifiable lipids, including mycolic acids. Concentrations of OSA used: for M. smegmatis, 100 μg/ml; for M. bovis BCG, 12.5 μg/ml. Differences were not statistically significant.

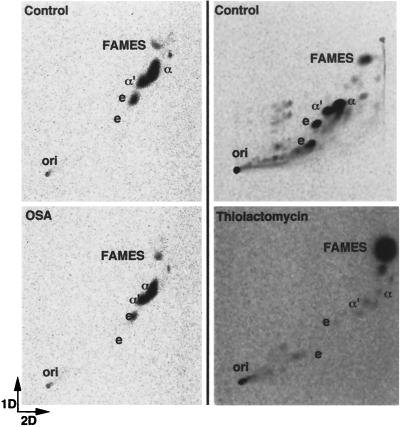

Effect of OSA on mycolic acid synthesis as compared with thiolactomycin.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of mycobacterial saponifiable lipids containing MAMES was performed using [14C]acetate pulse-labeling with 2-dimensional TLC and phosphorimaging. Differences in the effects of OSA and thiolactomycin were found between BCG and M. smegmatis. OSA treatment in BCG resulted in inhibition of all mycolic acids commonly found in this mycobacterial species (Fig. 3; Table 3). This decrease or percent change in both α- and keto-mycolates reached greater than 90% with an OSA concentration of four times the MIC. Similar results were demonstrated for MAC (data not shown). However, in M. smegmatis, individual mycolate classes were only slightly inhibited following exposure to OSA (Fig. 4; Table 3). Other lipids present in the saponifiable fraction included FAMES. No appreciable change was observed in this lipid class following OSA treatment in either of the two mycobacterial species characterized in this study (Fig. 3 and 4; Table 3).

FIG. 3.

Two-dimensional TLC showing the comparative effects of OSA and thiolactomycin on the mycolic acids of M. bovis BCG. First dimension, petroleum ether (bp 60 to 80°C)–acetone (95:5, vol/vol; three times); second dimension, toluene-acetone (97:3, vol/vol; one time). Abbreviations: ori, origin; α, α-mycolate; k, keto-mycolate. Equivalent counts per minute of the saponifiable lipid fraction were spotted at each origin.

TABLE 3.

Effects of OSA and thiolactomycin on the mycolic acids of M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis

| Organism | Mycolic acid species | Inhibition (% change)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OSA | TLM | ||

| M. bovis BCG | α | −56 | −69 |

| keto | −52 | −79 | |

| FAMES | —a | +147 | |

| M. smegmatis | α | −19 | −95 |

| α′ | −18 | −57 | |

| epoxy | −8 | −87 | |

| FAMES | — | +134 | |

—, no appreciable change was observed.

FIG. 4.

Two-dimensional TLC showing the comparative effects of OSA and thiolactomycin on the mycolic acids of M. smegmatis. First dimension, petroleum ether (bp 60 to 80°C)-acetone (95:5, vol/vol; three times); second dimension, toluene-acetone (97:3, vol/vol; one time). Abbreviations: ori, origin; α, α-mycolate; α′, α′-mycolate; e, epoxymycolate. Equivalent counts per minute of the saponifiable lipid fraction were spotted at each origin.

Thiolactomycin caused a decrease in all mycolate species in BCG (Fig. 3; Table 3) and M. smegmatis. However, while thiolactomycin uniformly inhibited all mycolate species in BCG, in M. smegmatis, a differential effect was observed between individual mycolic acid classes. Both α-mycolates and epoxymycolates were nearly completely diminished (95 and 87%, respectively), whereas α′-mycolates were less affected (57%) (Fig. 4; Table 3). In contrast to OSA, FAMES accumulated in both BCG and M. smegmatis following treatment with thiolactomycin.

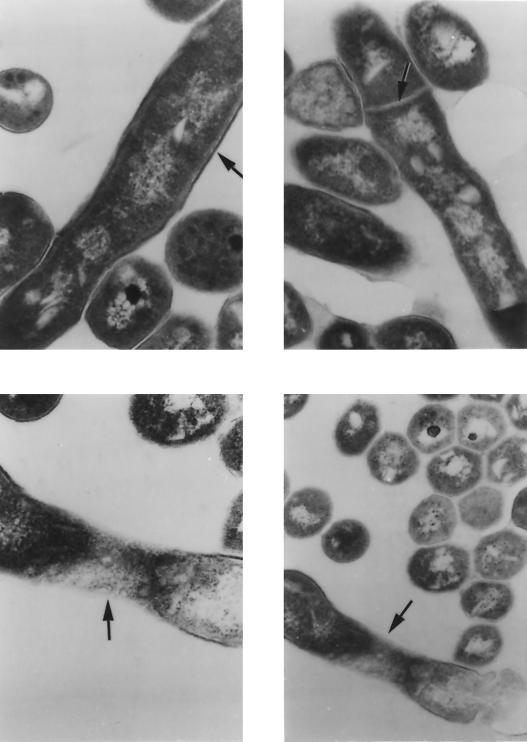

Transmission electron microscopy of OSA-treated BCG.

Inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis is known to disrupt the mycobacterial cell wall. Figure 5 shows transmission electron micrographs of OSA-treated BCG cells during cell division. Control organisms exhibited an intact cell wall and clearly defined septum, whereas in the presence of OSA, cell wall synthesis was disrupted with incomplete septum formation. In addition, outer-wall-associated lipids appeared to be dispersed from the electron transparent zone of the mycolic acids.

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron microscopy of OSA-treated M. bovis BCG (6.25 μg/ml). (Top) Intact cell wall ultrastructure (left) (magnification, ×117,000) and completed septum (right) (magnification, ×108,000). (Bottom) Disrupted cell wall ultrastructure (left) (magnification, ×130,000) and incomplete septum formation (right) (magnification, ×78,000).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that OSA, a compound designed to inhibit fatty acid synthesis by mimicking the transition state of the β-ketoacyl synthase, is inhibitory for a broad range of slow-growing mycobacterial species, including multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis. OSA treatment reduced mycolic acid accumulation in BCG and MAC cells, presumably by its effect on FAS systems in these mycobacteria. Cross-resistance was not observed for isolates resistant to isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, and pyrazinamide. A comparison of isoniazid, a known inhibitor of mycolic acid synthesis, and OSA revealed pertinent information. Isoniazid has been shown to inhibit both InhA, an enoyl-ACP reductase involved in fatty acid elongation, and KasA, a β-ketoacyl–ACP synthase (2, 12, 28, 31, 32). INH resistance has been associated with mutations in both of these genes, as well as the KatG gene, which encodes the mycobacterial catalase-peroxidase (54, 55, 57, 58). In this study, the mechanism of INH resistance for the M. tuberculosis isolates used was not determined. Of relevance is the finding that OSA inhibited the growth of INH-resistant M. tuberculosis (>0.04 μg/ml) as well as MAC, typically resistant to INH (>2.5 μg/ml) (19). This observation suggests that the inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis by OSA may be due to interaction with an enzymatic target different from that of INH, indicating a novel and possibly unexploited mechanism of action of OSA in M. tuberculosis.

Although OSA was designed to inhibit β-ketoacyl synthases, it has not been tested as an inhibitor of isolated FAS. In an earlier, related study conducted in our laboratory, structurally related sulfones and sulfoxides were found to inhibit FAS I isolated from M. smegmatis (41). Several of these compounds were both FAS I inhibitors and active against M. tuberculosis H37Rv in the radiometric growth assay. However, the correlation was not exact and issues of cell wall permeability and solubility prevented direct comparison of the data. OSA was selected for further study based on its solubility and its performance in whole-cell assays.

The differential susceptibility to OSA observed between slow- and rapid-growing mycobacterial species argues for the presence of unique targets in BCG and MAC. M. smegmatis may contain the same OSA target as BCG and MAC but possesses alternate cell wall compounds that permit survival in spite of OSA inhibition. Another potential possibility is the requirement for alteration, i.e., activation, of OSA prior to its interaction with the target protein(s) which may occur in slow-growing mycobacteria but not in rapid-growing species. However, the most probable interpretation is that differences in the mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway may exist between mycobacterial species. This possibility is further strengthened when the work of other investigators is considered in conjunction with our own. For example, InhA, a long chain, enoyl-ACP-dependent reductase involved in fatty acid elongation, is present in both M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (31). Several studies have revealed compelling evidence that InhA is the target for KatG-activated INH in M. smegmatis (12, 44). However, additional investigations suggest that this particular enzyme is not the principal target for KatG-activated INH in M. tuberculosis (31, 32). This discrepancy may reflect inherent differences in mycolate biosynthesis between the two organisms (31, 32, 42). Additionally, previous studies in our laboratory examining the effect of cerulenin on mycolate synthesis in M. smegmatis and BCG revealed clear differences in mycolic acid profiles between these two mycobacterial species following inhibitor exposure. Not only did the changes in mycolate synthesis differ between BCG and M. smegmatis, they were in direct opposition. For instance, completed mycolates decreased in BCG following exposure to cerulenin, whereas in M. smegmatis, all mycolate species increased, again suggesting that inherent differences in the mycolate biosynthetic pathway between the two species are responsible for these disparate responses (42).

This possibility is further strengthened by the differential effect of thiolactomycin on individual mycolic acid classes in M. smegmatis. In both the present study and that of other investigators (50), exposure to thiolactomycin resulted in substantially decreased amounts of α-mycolates and epoxymycolates, with a minor decrease in α′-mycolates (49). The authors of the previous study suggested that potential targets for thiolactomycin in this mycobacterial species include an elongation enzyme leading from either the C24:1Δ5 intermediate or from the shorter-chain α′-mycolates to the longer α-mycolates and oxygenated mycolates (50). In view of the current experimental evidence, the latter seems to be the more likely possibility. It should be noted that α′-mycolates, commonly found in rapid-growing mycobacteria, are not present in BCG and other slow-growing mycobacteria characterized in this study (18). Thus, while thiolactomycin treatment of BCG and M. smegmatis resulted in inhibition of both α-mycolates and oxygenated mycolates, the presence of α′-mycolic acids in the latter case may partially explain the differences observed in MICs between the two mycobacterial species (for BCG, 25.0 μg/ml; for M. smegmatis, 75 μg/ml) and indicate that disparities in mycolate biosynthesis may exist between BCG and M. smegmatis. One could speculate that such differences may extend to other slow- versus rapid-growing mycobacterial species.

Differences in mycolic acid profiles following OSA treatment in BCG and M. smegmatis were also noted. In the present study, all mycolic acids were significantly and uniformly inhibited in OSA-treated BCG (α- and keto-mycolates). This inhibition increased with an increasing concentration of OSA. In contrast, the effect of OSA on the mycolates of M. smegmatis (α′, α, and epoxy) was negligible and not inhibitory to growth. Previous studies have suggested the existence of multiple ACP-dependent FAS II systems in mycobacteria, responsible for not only fatty acid biosynthesis but also mycolic acid biosynthesis (2, 32, 42, 44). Such systems could be envisioned to interact with separate and distinct β-ketoacyl–ACP synthases as well as other enzymes involved in biosynthetic reactions of this type, including β-ketoacyl–ACP reductases, β-hydroxyacyl–ACP dehydratases, and β-enoyl–ACP reductases. A biological precedent for the existence of such enzymes has been described for Esherichia coli, in which multiple β-ketoacyl–ACP synthases have been found (21, 26, 27). Although thiolactomycin was originally thought to inhibit all three β-ketoacyl–ACP synthases in E. coli, recent evidence suggests that the principal target of thiolactomycin in this particular organism may be only β-ketoacyl–ACP I (25). Since OSA was designed to inhibit the β-ketoacyl synthase by mimicking the transition state of the reaction catalyzed by this enzyme, this compound could in theory inhibit both the multifunctional FAS I and monofunctional FAS II mycobacterial systems, as in the case of cerulenin. However, in this study, additional assays were performed which were designed to indirectly determine FAS I activity in the presence of each inhibitor by measuring phospholipid production. Only cerulenin, known to inhibit both FAS I and FAS II systems, interfered with phospholipid synthesis in either BCG or M. smegmatis (42). Neither thiolactomycin, active only against FAS II systems, nor OSA inhibited phospholipid synthesis in either of the two mycobacterial species tested (data not shown), suggesting that the principal target of OSA may lie in an ACP-dependent FAS II system. In addition, previous work in our laboratory and others has demonstrated that cerulenin and thiolactomycin strongly inhibited [14C]acetate incorporation into other extractable mycobacterial lipids, a finding consistent with the known mechanism of action of both inhibitors. In contrast, OSA inhibited only mycolic acids, with no appreciable change in label incorporation in any of the other mycobacterial lipid classes tested. This distinction suggests the presence of a unique and highly specific target for this compound in slow-growing mycobacteria. Such a target may involve an as-yet-unidentified enzyme or enzyme system present in slow-growing mycobacteria which is not present or inactive in rapid-growing species.

Additional information was obtained by careful analysis of FAMES in OSA-treated BCG and M. smegmatis. Other investigators have determined that these lipids most likely represent saturated alkyl intermediate(s) in mycolic acid synthesis (31). While 2-dimensional TLC of OSA-treated BCG revealed that mycolic acid synthesis was inhibited, no apparent effect was seen in the FAMES present in this fraction when the compound was used at the MIC (6.25 μg/ml). A similar observation was noted in OSA-treated M. smegmatis. However, at four times the MIC, OSA treatment of BCG resulted in an increase in label incorporation into extractable nonpolar lipids. This may suggest that a noncovalently bound, extractable intermediate in mycolate synthesis accumulates following OSA treatment, an effect intensified with higher concentrations (four times the MIC) of compound. In contrast, FAMES increased in thiolactomycin-treated BCG, while mycolic acids decreased, a finding consistent with that of earlier studies using cerulenin (42). Thus, in BCG, while completed mycolates decreased with OSA, thiolactomycin, and cerulenin (42), the changes in FAMES were clearly not the same, suggesting that inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis in BCG may occur prior to synthesis of the saturated alkyl intermediate with OSA, but between this intermediate and completed mycolates with cerulenin and thiolactomycin. Alternatively, OSA-mediated inhibition of mycolate synthesis in BCG and MAC may involve an as-yet-unidentified enzyme or enzyme system. In summary, the effects of OSA, cerulenin, and thiolactomycin are mycobacterial species specific and compound specific and inherent differences in the mycolic acid biosynthetic pathway may exist between rapid- and slow-growing mycobacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Janet Folmer for performance of electron microscopy and William Bishai for providing equipment and laboratory space for some portions of this study.

This study was financially supported in part by NIH grant AI43846, the Raynam Research Fund, and the Becton Dickinson Centennial Fellowship in Clinical Microbiology (N.M.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altamirano M, Marostenmaki J, Wong A, Fitzgerald M, Black W, Smith J. Mutations in the catalase-peroxidase gene from isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1162–1165. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannerjee A, Dubnau E, Quemard A, Balasubramanian V, Um K S, Wilson T, Collins D, DeLisle G, Jacobs W R., Jr inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry C, III, Mdluli K. Drug sensitivity and environmental adaptation of mycobacterial cell wall components. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:275–281. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besra G, Chatterjee D. Lipids and carbohydrates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besra G, Khoo K, McNeil M, Dell A, Morris H, Brennan P. A new interpretation of the structure of the mycolyl-arabinogalactan complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through the characterization of oligoglycosyl alditol fragments by fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry and 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;24:84–90. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch K. Fatty acid synthases from Mycobacterium phlei. Methods Enzymol. 1975;35:84–90. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)35141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch K. Control mechanisms for fatty acid synthesis in Mycobacterium smegmatis. In: Meister A, editor. Advances in enzymology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1977. pp. 1–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom B, Murray C. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science. 1992;257:1055–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan P, Draper P. Ultrastructure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Bloom B, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan P, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham A, Spreadbury C. Mycobacterial stationary phase induced by low oxygen tension: cell wall thickening and localization of the 16-kilodalton α-crystallin homolog. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:801–808. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.801-808.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dessen A, Quemard A, Blanchard J S, Jacobs W R, Jr, Sachettini J C. Crystal structure and function of the isoniazid target of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1995;267:1638–1641. doi: 10.1126/science.7886450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson G, Minnikin D, Minnikin S, Parlett J, Goodfellow M. Systematic analysis of complex mycobacterial lipids. In: Goodfellow M, Minnikin D, editors. Chemical methods in bacterial systematics. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyllenhaal O, Ehrsson H. Determination of sulphonamides by electron-capture gas chromatography. Preparation and properties of perfluoroacyl and pentaflurobenzyl derivatives. Chromatography. 1975;107:327–333. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(75)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Yamamoto O, Sasaki H, Kawaguchi H, Okazaki H. Mechanism of action of the antibiotic thiolactomycin: inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Res Commun. 1983;115:1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(83)80050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi T, Yamamoto O, Sasaki H, Okazaki H. Inhibition of fatty acid synthesis by the antibiotic thiolactomycin. J Antibiot. 1984;37:1456–1461. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heifets H, Lindholm-Levy P, Libonati J, et al. Radiometric broth macrodilution method for determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC's) with Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. Denver, Colo: National Jewish Center for Immunology and Respiratory Medicine; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinrikson H P, Pfyffer G E. Mycobacterial mycolic acids. Med Microbiol Lett. 1994;3:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inderlied C, Salfinger M. Antimicrobial agents and susceptibility tests: mycobacteria. In: Murray P, editor. Manual of clinical microbiology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 1385–1404. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inokoshi J, Tomoda H, Hashimoto H, Watanabe A, Takeshima H, Omura S. Cerulenin-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevesiae with an altered fatty acid synthase gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:90–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00280191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackowski S, Cronan J E, Jr, Rock C O. Lipid metabolism in prokaryotes. In: Vance D E, Vance J, editors. Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins, and membranes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Publishers B. V.; 1991. pp. 43–85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones P B, Parrish N M, Houston T A, Stapon A S, Bansal N P, Dick J D, Townsend C A. A new class of anti-tuberculosis agents. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3304–3314. doi: 10.1021/jm000149l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolattukudy P, Fernandes N, Azad A, Fitzmaurice A, Sirakova T. Biochemistry and molecular genetics of cell wall lipid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:263–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3361705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korvick J, Benson C. Advances in the treatment and prophylaxis of Mycobacterium avium complex in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus. In: Korvick J, Benson C, editors. Mycobacterium avium complex infection: progress in research and treatment. 87. Lung biology in Health and Disease. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Incorporated; 1996. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kremer L, Douglas J D, Baulard A R, Morehouse C, Guy M R, Alland D, Dover L G, Lakey H, Jacobs W R, Brennan P J, Minnikin D E, Besra G S. Thiolactomycin and related-analogues as novel anti-mycobacterial agents targeting KasA and KasB condensing enzymes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16857–16864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe P N, Rhodes S. Purification and characterization of [acyl-carrier-protein]acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli. Biochem J. 1988;250:789–796. doi: 10.1042/bj2500789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnuson K S, Jackowski S, Rock C O, Cronan J E., Jr Regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:522–542. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.522-542.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonough K, Kress V, Bloom B. Pathogenesis of tuberculosis: interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2763–2773. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2763-2773.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeil M, Brennan P. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell envelope of mycobacteria in relation to bacterial physiology, pathogenesis and drug resistance; some thoughts and possibilities arising from recent structural information. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil M, Daffe M, Brennan P. Location of the mycolyl ester substituents in the cell walls of mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6934–6943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mdluli K, Sherman D R, Hickey M J, Kreiswirth B N, Morris S, Stover C K, Barry C E., III Biochemical and genetic data suggest that InhA is not the primary target for activated isoniazid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1085–1090. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mdluli K, Slayden R, Zhu Y, Ramaswamy S, Pan X, Mead D, Crane D, Musser J, Barry C., III Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis β-ketoacyl ACP synthase by isoniazid. Science. 1998;280:1607–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Middlebrook G. Isoniazid-resistance and catalase activity of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954;69:471–472. doi: 10.1164/art.1954.69.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minnikin D, O'Donnell A, Goodfellow M, Alderson G, Athalye M, Schaal A, et al. An integrated procedure for the extraction of bacterial isoprenoid quinones and polar lipids. J Microbiol Methods. 1984;2:233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minnikin D, Minnikin S, O'Donnell A, Goodfellow M. Extraction of mycobacterial mycolic acids and other long-chain compounds by an alkaline methanolysis procedure. J Microbiol Methods. 1984;2:243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morisaki N, Funabashi H, Shimazawa R, Furukawa J, Kawaguchi A, Okuda S, Iwasaki S. Effect of side-chain structure on inhibition of yeast fatty-acid synthase by cerulenin analogues. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb19876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikaido H, Kim S, Rosenberg E. Physical organization of lipids in the cell wall of Mycobacterium chelonae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1025–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nolte F, Metchock B. Mycobacterium. In: Murray P, Baron E, Pfaller M, Tenover F, Yolken R, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Omura S. The antibiotic cerulenin, a novel tool for biochemistry as an inhibitor of fatty acid synthesis. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:681–697. doi: 10.1128/br.40.3.681-697.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omura S. Cerulenin. Methods Enzymol. 1981;72:520–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parrish N. Ph.D. thesis. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parrish N, Kuhajda F, Heine H, Bishai W, Dick J. Antimycobacterial activity of cerulenin and its effects on lipid synthesis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:219–226. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quemard A, Lacave C, Laneelle G. Isoniazid inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis by cell extracts of sensitive and resistant strains of Mycobacterium aurum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1035–1039. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.6.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quemard A, Sacchettini J C, Dessen A, Vilcheze C, Bittman R, Jacobs W R, Jr, Blanchard J S. Enzymatic characterization of the target for isoniazid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8235–8241. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rastogi N, Frehel C, David H. Triple-layered structure of the mycobacterial cell wall: evidence of a polysaccharide-rich outer layer in 18 mycobacterial species. Curr Microbiol. 1986;13:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaki H, Oishi H, Hayashi T, Matsura I, Ando K, Sawada M. Thiolactomycin, a new antibiotic: structure elucidation. J Antibiot. 1982;35:396–400. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoeb H, Bowman B, Ottolenghi A, Merola A. Evidence for the generation of active oxygen by isoniazid treatment of extracts of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:404–407. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoeb H, Bowman B, Ottolenghi A, Merola A. Peroxidase-mediated oxidation of isoniazid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:399–403. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siddiqi S. Radiometric (BACTEC) tests for slowly growing mycobacteria. In: Isenberg H, editor. Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 5.14.1–5.14.25. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slayden R, A, Lee R E, Armour J W, Cooper A M, Orme I M, Brennan P J, Besra G S. Antimycobacterial activity of thiolactomycin: an inhibitor of fatty acid and mycolic acid synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2813–2819. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takayama K, Schnoes H K, Armstrong E L, Boyle R W. Site of inhibitory action of isoniazid in the synthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Lipid Res. 1975;16:308–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valway S, Sanchez M, Shinnick T, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, Jones J, Westmoreland H, Onorato I. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:633–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Youtt J. A review of the action of isoniazid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969;99:729–749. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1969.99.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Garbe T, Young D. Transformation with katG restores isoniazid-sensitivity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates resistant to a range of drug concentrations. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:521–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Heym B, Allen B, Young D, Cole S. The catalase-peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature. 1992;358:591–593. doi: 10.1038/358591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Lathigra R, Garbe T, Catty D, Young D. Genetic analysis of superoxide dismutase, the 23 kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Young D. Molecular mechanisms of isoniazid: a drug at the frontline of tuberculosis control. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90117-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, Young D. Strain variation of the katG region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:301–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]