Abstract

Stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation is arguably one of the fastest developing areas in preventive medicine. The increasing use of direct oral anticoagulants and nonpharmacologic methods such as left atrial appendage closure for stroke prevention in these patients has increased clinicians’ options for optimal care. Platelet antiaggregants are also commonly used in other ischemic cardiovascular and or cerebrovascular conditions. Long term use of oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation is associated with elevated risks of major bleeds including especially brain hemorrhages, which are known to have extremely poor outcomes. Neuroimaging and other biomarkers have been validated to stratify brain hemorrhage risk among older adults. A thorough understanding of these biomarkers is essential for selection of appropriate anticoagulant or left atrial appendage closure for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. This article will address advances in the stratification of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke risk among patients with atrial fibrillation and other conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of death and functional impairment worldwide. About 795,000 people have a new or recurrent ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke each year in the United States (Mozaffarian et al., 2016). Despite considerable advances in acute reperfusion therapies for selected acute ischemic stroke patients, data show that effective prevention strategies remain the best approach for reducing the burden of stroke related death/disability (Kernan et al., 2014; Meschia et al., 2014).

Cardiac embolism is responsible for approximately one-third of all ischemic strokes (Topcuoglu et al., 2018). Atrial fibrillation (AF)—the prototype cause of cardiac embolism—accounts for a fivefold increase of ischemic stroke risk (Benjamin et al., 2017). The mechanism of ischemic stroke in nonvalvular AF (NVAF) mainly results from embolization from left atrial appendage (LAA) thrombi (Blackshear and Odell, 1996). Based on pooled data from four large contemporary randomized clinical trials (RCTs), embolic stroke is eight times higher than systemic embolism (Bekwelem et al., 2015). Ischemic strokes attributed to AF are typically more severe, have higher recurrence rate and poorer long-term outcome than non-AF-related ischemic strokes (Kimura et al., 2005; Marini et al., 2005). Therefore, both primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies are of the outmost importance to decrease morbidity/mortality in AF patients.

Life-long oral anticoagulant (OAC) use has been the gold standard for stroke prevention in AF patients. However, vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin and the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) increase the intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) risk by two- to fivefold even among patient populations at low baseline intracerebral hemorrhage risk (Gurol, 2018). OAC-related ICHs have an estimated mortality rate of ~50%, making OAC-ICH one of the most lethal and disabling condition among common medical emergencies (Fang et al., 2007). Real-world data show that OACs are globally underutilized, mostly due to the fear of ICH (Kakkar et al., 2013; Piazza et al., 2016). Conversely some clinicians underestimate the risk of ICH, focusing only on thromboembolic prevention (Baczek et al., 2012; Gamra et al., 2014). Effective nonpharmacologic stroke prevention measures circumventing the need for lifelong oral anticoagulation exist such as left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved WATCHMAN (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) device for NVAF. Therefore, an accurate stratification of ICH risk is essential for appropriate patient selection. The recent publication of a RCT showing similar ischemic event rates between NVAF patients randomized to LAAC or DOACs support the use of LAAC in appropriate high hemorrhage risk populations (Osmancik et al., 2020). Overall, the optimal approach for stroke prevention is based on identification of all conditions associated with higher ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke risk and thorough consideration for both drug-based and nonpharmacologic options.

Moreover, recent years have seen major progress in our understanding of the risks of embolic/hemorrhagic stroke using biomarkers and neuroimaging in particular (Gokcal et al., 2018). In this chapter, we discuss relevant factors associated with embolic as well as hemorrhagic stroke risk in patients with NVAF and review all available options for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke prevention. We also briefly discuss issues pertaining to risk markers and conditions requiring platelet antiaggregant use.

STRATIFICATION OF EMBOLIC STROKE RISK IN AF

AF is associated with advanced age, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease, which are established risk factors for other stroke subtypes as well. Stroke risk in AF increases in the presence of additional risk factors. Currently, the most commonly used risk-stratification schemes for AF-related embolism are based on the presence of clinical variables. The CHA2DS2-VASc [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (doubled), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or TIA or thromboembolism (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74 years, sex (female) category] scoring system is the most commonly used risk stratification score. Current guidelines recommend the use of CHA2DS2-VASc to differentiate high-risk from “truly low-risk” AF patients; the latter having annual embolic stroke rates of less than 1% (Camm et al., 2012; January et al., 2014a). The current US guidelines recommend long-term OAC use or LAAC with a WATCHMAN in patients with CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or more for men, or 3 or more for women (January et al., 2019). Current guidelines do not recommend OAC in younger AF patients without coexisting cardiovascular risk factors, if the projected risk is lower than 1% per year. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is easy to use, but its accuracy in predicting embolic events has been relatively low in validation efforts outside of its initial development/validation datasets (Singer et al., 2013). Furthermore, it is known to overestimate the risk until a score of 3–4 is reached (Singer et al., 2013).

The ATRIA (anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation) score is a computerized scoring system, developed using long-term follow-up data from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (Singer et al., 2013). The clinical variables used are similar to the CHA2DS2-VASc, but the ATRIA score includes a measure of renal function by estimation of the glomerular filtration rate, an important biologic variable missing in other risk stratification scores. The calculation of the ATRIA score has important differences from the CHA2DS2-VASc, emphasizing older age and past history of ischemic stroke. Advantages of the ATRIA score are better prediction of ischemic stroke risk and enhanced ability for predicting severe strokes.

Since these risk-stratification schemes have shown a modest predictive value for identifying high-risk patients and also a tendency to overestimate embolic risk, recent years have seen considerable amount of work aiming to improve thromboembolic risk prediction focusing on plasma biomarkers—particularly high-sensitivity troponin (hs-T) and N-terminal fragment B-type natriuretic peptide (nt-BNP) (Hijazi et al., 2013, 2014a,b). As a result, a recently developed biomarker-based stroke risk score [ABC (age, biomarkers [hs-T and nt-BNP], and clinical history of stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA))] has been validated in a variety of clinical trial cohorts (Hijazi et al., 2016; Oldgren et al., 2016). However, recent real-world data reported no improvement in stroke prediction after adding biomarkers to the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Rivera-Caravaca et al., 2019). Thus, it is important to balance the pros and cons of different ischemic risk stratification schemes with a focus on improving risk prediction using clinical, laboratory, and neuroimaging data.

Although some clinical factors and biomarkers are associated with an increased risk of embolic stroke, they do not offer any information about the pathophysiologic factors predisposing to blood stasis in the left atrium and particularly the LAA, which is currently recognized as the major source (>95%) of cardiac thrombus formation in these patients. A number of studies are currently investigating the relationship of echocardiographic parameters representing LA function and morphology (LA dilatation, spontaneous echocardiographic contrast, LAA emptying velocity, or LAA morphology) with thromboembolic risk (Providencia et al., 2013; Lupercio et al., 2016; Vinereanu et al., 2017; Leung et al., 2018).

Beyond the clinical variables, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides information pertaining to symptomatic/silent lesions that might be relevant to the prediction of future ischemic and/or hemorrhagic strokes. Population-based studies have been using brain MRI for years to further understand mechanisms and progression of brain injury in older adults. Several studies showed an association of AF with MRI-defined brain infarctions, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) or cerebral microbleeds (CMB) known to be related to future stroke risk, cognitive impairment, and death (Vermeer et al., 2007).

MRI-defined brain infarctions have been reported in 28%–90% of patients with AF without prior strokes. Moreover, AF was an independent risk factor for MRI-defined brain infarctions in different populations (Haeusler et al., 2014). However, the exact pathophysiology of MRI-defined brain infarctions in AF is uncertain. Besides AF-related embolism and hypoperfusion proposed mechanisms include concomitant cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD). In a longitudinal study including patients who had brain MRI for routine health checkups, the incidence of symptomatic ischemic strokes was significantly higher among patients with AF with MRI-defined brain infarctions at baseline compared to those without (5.6% per year vs 2.7% per year, hazard ratio 1.787, 95% CI 1.08–2.93, P = 0.022) (Cha et al., 2014). However, current guidelines do not recommend OAC/LAAC based on the presence of silent brain infarctions in patients with low clinical risk stratification scores, as the utility of these imaging-defined lesions has not been validated in well-designed RCTs in this population.

STRATIFICATION OF HEMORRHAGIC STROKE RISK IN AF

Patients with AF also have an increased bleeding risk with the long-term use of warfarin or DOACs. The risk ranges between 2.1% and 3.6% per year for major bleeds, and 15%–25% per year for all bleeding types (major, clinically relevant, and minor). Similar to thromboembolic risk, bleeding risk depends on the presence of various risk factors. A number of bleeding stratification risk scores have been developed to assist predicting bleeding risk in patients treated with OACs. The HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function [1 point each], stroke, bleeding history, or labile international normalized ratio (INR), elderly [65 years], drugs/alcohol concomitantly [1 point each]) score is one of these bleeding risk stratification schemes (Lane and Lip, 2012). However, since OAC-related hemorrhages are heterogeneous in terms of site, severity, and outcomes, “hemorrhagic risk scores” including HAS-BLED are much less helpful in identifying high-risk patients for a specific type of bleeding. In a recent prospective large multicenter study, the ability of the HAS-BLED score to predict ICH was less than chance (C-index 0.41, 95% CI 0.29–0.5) (Wilson et al., 2018). Therefore, all patients with AF should be evaluated individually for every potential risk factor that might increase the bleeding risk before and after starting OAC. LAAC is considered in NVAF patients at higher than usual bleeding risk. Because bleeding risk is also a dynamic process, its risk can change over time. Thus, all relevant factors that might predispose to hemorrhagic events need to be reviewed in every follow-up visit and nonpharmacologic methods considered, if necessary.

Of all OAC-related hemorrhages, ICH is by far the most feared complication. OAC-ICH is a devastating condition with a high in-hospital mortality (52% for OAC-ICH vs 25.8% for other ICHs) (Rosand et al., 2004). Approximately 70% of OAC-ICHs result from ruptured arteries/arterioles weakened by cSVDs (Steiner et al., 2006). Therefore, ICH survivors or patients with neuroimaging markers of cSVDs that increase ICH risk constitute the most challenging NVAF population in terms of stroke prevention. Optimal risk-stratification requires identifying these high ICH risk markers in patients who are candidates for long-term OAC treatment.

The most common forms of cSVDs among the elderly are hypertensive cSVD (HTN-cSVD) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). HTN-cSVD refers to the type of cSVD associated with arterial hypertension as well as other well-known vascular risk factors that predominantly affect small perforating end arteries supplying the deep gray nuclei and adjacent white matter (Charidimou et al., 2016). Pathologically, this type of cSVD is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis, lipohyalinosis, microatheroma or microaneurysm formation in the affected arteries. Vessel wall thickening and restriction of the lumen result in tissue hypoperfusion and ischemia that contributes to WMH, lacunar infarcts, and microinfarcts, while fibrinoid necrosis can cause rupture of microaneurysms, leading to hemorrhagic changes such as deep ICH and CMBs (Wardlaw et al., 2013). CAA is the second most common form of cSVD in older adults, a pathology that shows an increased prevalence rate in parallel with advanced age (Gurol et al., 2016). Pathologically, CAA is associated with β-amyloid deposition within small-to-medium sized arteries and arterioles predominantly located in the cortex and leptomeningeal space leading to smooth muscle degeneration, vessel wall thickening, focal wall fragmentation, microaneurysm formation, and perivascular leakage of blood products in the affected vessels (Wardlaw et al., 2013).

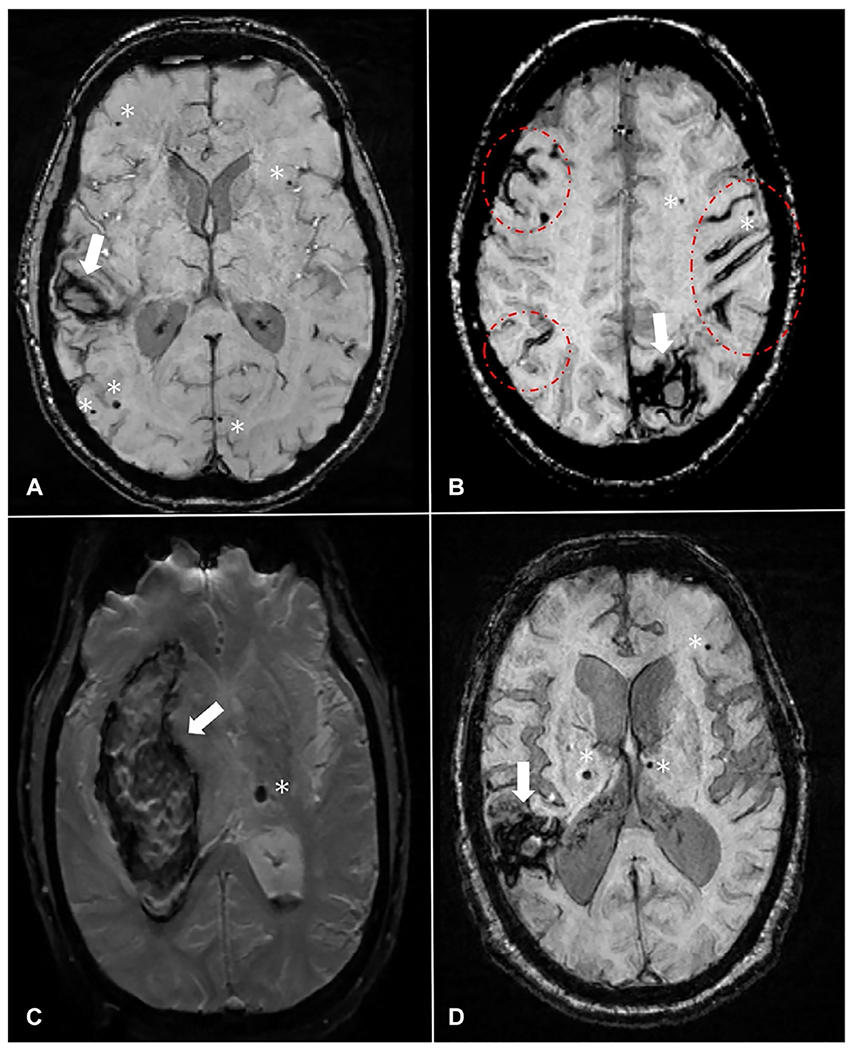

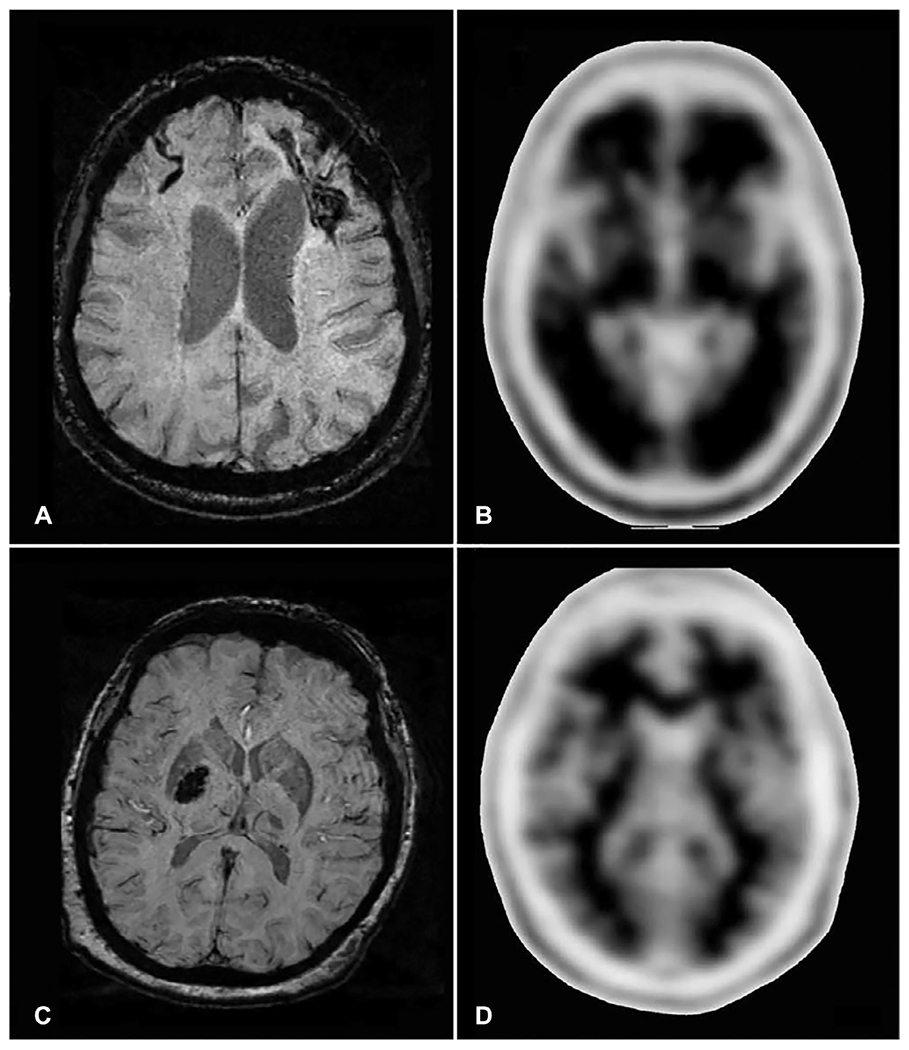

Although both types of cSVDs present similar neuroimaging markers, their distribution and ICH risks differ. CAA may be radiologically diagnosed, using the Boston criteria, in the presence of lobar ICH and strictly lobar CMBs in patients 55 years or older, as long as alternative diagnoses are ruled out (Knudsen et al., 2001) (Fig. 30.1A). Cortical superficial siderosis (cSS), characterized by linear hemosiderin deposits over the cortex or within sulci, has also been validated as a hemorrhagic neuroimaging marker of CAA increasing the diagnostic specificity of the Boston criteria (Linn et al., 2010) (Fig. 30.1B). Conversely, the presence of topographically deep ICH and deeply located CMBs supports HTN-cSVD (Pantoni, 2010) (Fig. 30.1C). However, about 20%–57.5% of ICHs in different populations have concomitant hemorrhagic lesions in both lobar and deep regions, known as mixed location ICH/CMB (Pasi et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2019) (Fig. 30.1D). In addition to the hemorrhagic markers visible on MRI, positron emission tomography (PET) with amyloid tracers can also help differentiate CAA from HTN-cSVD. Florbetapir, an 18F-based PET tracer, is shown to bind vascular amyloid. Florbetapir PET is validated to help diagnose probable CAA among cognitively healthy patients with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 89%. (Fig. 30.2) (Gurol et al., 2016). Amyloid PET can help to confirm or rule out CAA in patients with mixed location (lobar and deep) ICH and/or CMBs or other situations, where CAA is suspected but not diagnosed based on MRI findings alone. Although the FDA approved the use of this tracer for detection of amyloid, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) did not approve reimbursement and only few insurance systems are paying for this test. Until CMS approval, the cost is the limiting factor for more widespread use of Florbetapir PET. The risk of future ICH according to imaging markers and SVD types is presented in Table 30.1.

Fig. 30.1.

Hemorrhagic imaging markers in different types of cerebral small vessel diseases. (A) Patient with CAA with a lobar ICH (arrow, right temporal) and strictly lobar CMBs (stars). (B) Patient with CAA with a lobar ICH (arrow, left occipital), strictly lobar CMBs (stars), and multifocal cSS (circle/ellipses). (C) Patient with HTN-cSVD with a deep ICH (arrow, right basal ganglia) and a CMB located in deep brain region (star, left thalamus). (D) Patient with mixed ICH/CMB with a lobar ICH (arrow, right parietotemporal), lobar CMB (star, left frontal) as well as deeply located CMBs (stars, right and left thalamus). All MRI images are SWI-MRI sequences. The arrow represents ICH, the star represents CMB, and the oval shape represents cSS. CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CMB, cerebral microbleeds; cSS, cortical superficial siderosis; HTN-cSVD, hypertensive cerebral small vessel disease; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SWI-MRI, susceptibility-weighted imaging-magnetic resonance imaging sequence.

Fig. 30.2.

Florbetapir PET for diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. (A–B) represent a patient who had a left frontal intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and right frontal cortical superficial siderosis on susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI, Panel A), fulfilling neuroradiological criteria for cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Florbetapir PET (Panel B) in this CAA patient shows loss of contrast between the cortex and subcortical white matter (positive scan), indicating intense Florbetapir uptake in the cortex because of high vascular amyloid load. The patient in (C–D) had a hypertensive deep right basal ganglia hemorrhage visible on SWI MRI (Panel C). In this patient’s Florbetapir PET (Panel D), the contrast between cortex and subcortical structures is preserved (negative scan), confirming low amyloid load in the cortex. Modified from Gurol ME, Becker JA, Fotiadis P, et al. (2016). Florbetapir-PET to diagnose cerebral amyloid angiopathy: A prospective study. Neurology 87: 2043–2049 with permission. Copyright ©2016, Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Table 30.1.

Neuroimaging markers of SVDs and risk of incident ICH in different scenarios

| Imaging marker | Type of SVD | Risk of ICH |

|---|---|---|

| General population over 55 years of age | 0.08% per year | |

| ICH and CMBs strictly in cortical/lobar regions | Probable CAA | Average = ~ 10% per year |

| ICH and CMBs strictly in cortical/lobar regions+ cSS | Probable CAA | Up to 26.9% per year for multifocal cSS |

| >1 CMBs strictly in cortical/lobar regions without ICH | Probable CAA | 5% per year |

| > 1 CMBs strictly in cortical/lobar regions + cortical superficial siderosis without ICH | Probable CAA | 19% at 5-year follow-up |

| ICH/CMBs in deep brain regions | HTN-cSVD | Average = ~2% per year |

| ICH/CMBs in lobar and deep brain regions concomitantly | Mixed ICH/CMB | 5.1% per year |

CMB, cerebral microbleed; cSS, cortical superficial siderosis; HTN-cSVD, hypertensive cerebral small vessel disease; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

Unfortunately, no RCT has clarified the risk of ICH recurrence with OAC therapy among ICH survivors. The location of ICH is often considered in decision making given the fact that lobar ICH related to CAA demonstrate a much higher recurrence rate than deep ICH due to HTN-cSVD. Current guidelines recommend avoiding warfarin treatment following lobar ICH, whereas resuming OAC therapy might be considered after nonlobar ICH particularly among patients at high risk for thromboembolic stroke and/or low risk of ICH recurrence (Hemphill et al., 2015). In the real world, clinicians tend to avoid OACs or prescribe DOACs instead of resuming warfarin if patients experience a warfarin-related ICH since these newer therapies have lower ICH rates among patients at low baseline risk. However, the safety of these agents in this particular patient population is not known due to the fact that RCTs did not include patients with ICH history. Thus, LAAC with the FDA-approved WATCHMAN device may be a strong alternative among ICH survivors and among patients with high ICH risk based on markers.

Patients with CAA with strictly lobar CMBs in the absence of ICH also show a high rate of first-time ICH upon follow-up (5 per 100 person-years). Warfarin use has been reported to be a predictor of first ICH independently of other conventional risk factors in CAA patients with strictly lobar CMBs without ICH (van Etten et al., 2014). CMBs have been reported in ~25% of patients who had an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (Wilson et al., 2016). The future risk of ICH has been reported to be sixfold higher in patients with ischemic stroke or TIA with CMBs as compared to those without CMBs. The risk increased up to 14-fold when the number of CMBs was 5 or more (Wilson et al., 2016). The presence of CMBs was also more common among patients with warfarin-related ICH as compared to anticoagulated patients without ICH (Lee et al., 2009). A recent multicenter prospective observational cohort study showed an independent association between CMBs and symptomatic ICH risk in patients with AF anticoagulated with warfarin or DOAC after recent ischemic stroke or TIA. The rate of ICH increased as the CMB burden increased (Wilson et al., 2018). Furthermore, the type of OAC used did not significantly affect the hazard of symptomatic ICH associated with CMB presence (hazard ratio interaction term 0.88; 95% CI 0.04–17.13, P = 0.92).

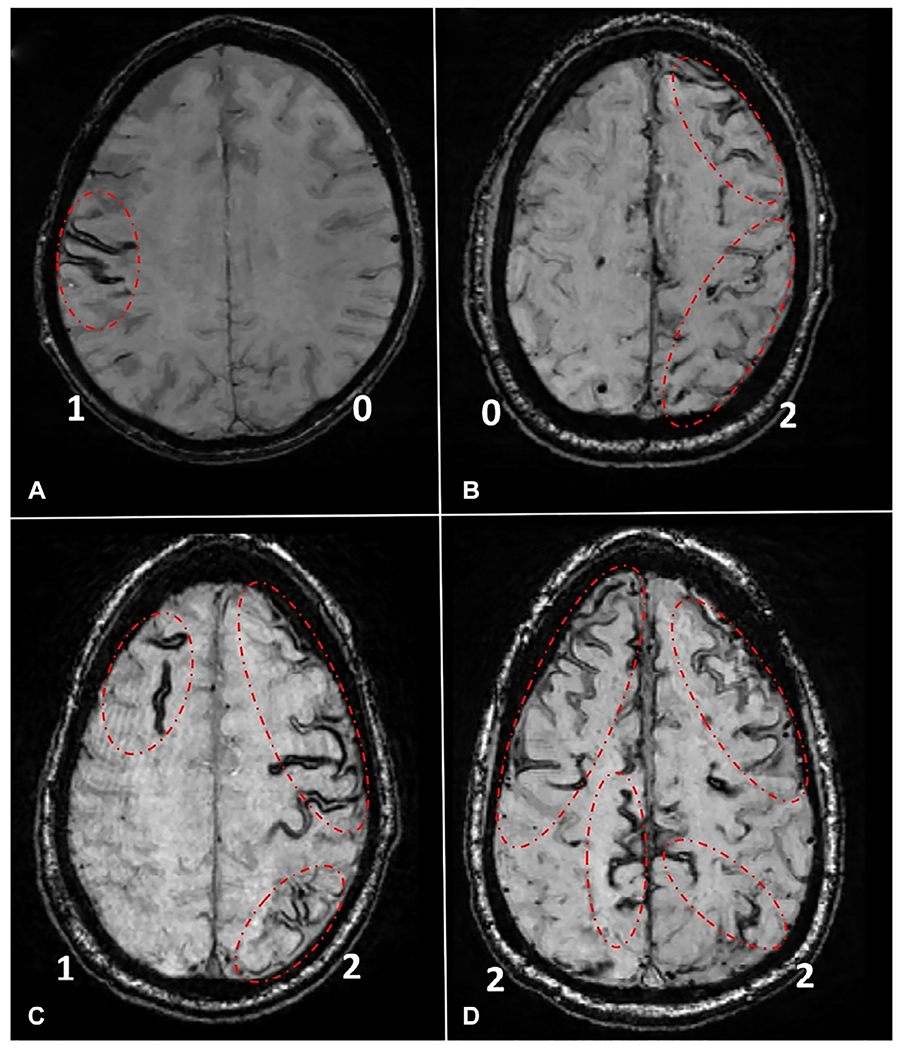

Approximately, 60% of CAA patients have cSS that has been consistently reported as an important marker for high ICH risk regardless of history of previous ICH (Roongpiboonsopit et al., 2016; Charidimou et al., 2017b). Furthermore, annual incidence rates of ICH increase up to 26.9% even without any anticoagulation if the CAA patient has multifocal/disseminated cSS (Charidimou et al., 2017a). The cSS multifocality score is a validated tool that can help further stratify the risk of recurrent ICH in patients who survived a CAA-related lobar ICH (Fig. 30.3). Due to high ICH risks, nonanticoagulant strategies such as LAAC should be considered in NVAF patients with cSS (Gurol, 2018).

Fig. 30.3.

Representative examples of the cortical superficial siderosis (cSS) multifocality score. To assess multifocality of cSS, each hemisphere is scored separately for cSS, as following: 0: none; 1: 1–3 immediately adjacent sulci with cSS; and 2: >3 immediately adjacent sulci (disseminated) or >1 nonadjacent sulci with cSS. The total score is derived by adding the right and left hemisphere scores (range 0–4). Examples are presented on the figure, and the score for each hemisphere (0,1,2) is provided in bottom corners of each patient scan. (A) Patient with a total cSS score of 1 (1 for right and 0 for left hemisphere). (B) Patient with a total cSS score of 2 (0 for right and 2 for left hemisphere). (C) Patient with a total cSS score of 3 (1 for right and 2 for left hemisphere). (D) Patient with a total cSS score of 4 (2 for right and 2 for left hemisphere). All MRI images are SWI-MRI sequences. SWI-MRI, susceptibility-weighted imaging-magnetic resonance imaging.

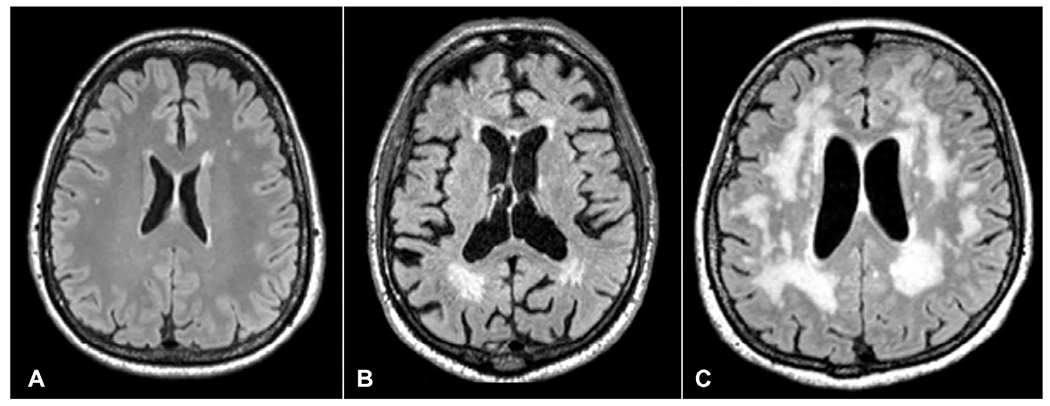

White matter hyperintensities on FLAIR MRI are another imaging marker of that might be observed in patients with stroke as well as in the general population (Fig. 30.4). In a longitudinal study of community-based stroke-free population, MRI-defined WMH burden was found to be an independent risk factor for spontaneous ICH, even in the absence of anticoagulant therapy (Folsom et al., 2012). Other studies have shown that the presence and severity of leukoaraiosis was an independent risk factor for warfarin-related and spontaneous ICH, respectively, in patients with ischemic stroke or CAA (Smith et al., 2002, 2004). A recent multicenter observational study prospectively followed 937 patients with cardioembolic strokes who were older than 65 years of age and who were started on OACs (warfarin or DOAC) to identify imaging predictors of future ICH. Patients with moderate/severe WMH and those who had CMBs at baseline MRI had higher risk of ICH during follow-up. The rate of ICH was the highest in patients with both CMBs and moderate/severe WMH (Marti-Fabregas et al., 2019). About two-thirds of the study cohort were started on warfarin, whereas one-third were on DOACs. The type of OAC did not influence the ICH risk. Overall, CMBs, cSS, and moderate-to-severe white matter disease are imaging markers easily identifiable on brain MRI scans that can sensitively predict future ICH risk, thus assisting clinicians select LAAC vs lifelong OAC use in NVAF patients.

Fig. 30.4.

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI sequence. (A) Mild FLAIR white matter hyperintensities (WMH), (B) moderate WMH, and (C) severe WMH.

PREVENTION OF ISCHEMIC STROKE IN PATIENTS WITH AF AT LOW HEMORRHAGIC RISK

This section summarizes data supporting the use of warfarin or DOACs in NVAF. All RCTs systematically excluded patients with a past history of ICH as well as patients with a high hemorrhage risk. The RCT data summarized below should be viewed with these important caveats in mind. Warfarin has been used to prevent stroke and systemic embolism in patients with AF since the 1950s. A meta-analysis of RCTs from the 1990s showed that adjusted-dose warfarin reduced stroke or systemic embolism by 64% and all-cause mortality by 26% when compared to placebo (Hart et al., 2007). Despite its efficacy, warfarin has several limitations such as narrow therapeutic window, need for frequent blood draws to keep the international normalized ratio within the therapeutic range, several interactions with food and other drugs, and most importantly, an increased risk of hemorrhagic events, particularly ICH. Furthermore, as previously discussed, warfarin-related ICHs have a much higher risk of in-hospital mortality and poorer outcomes when compared to ICHs unrelated to OAC use (Rosand et al., 2004). These factors prompted the search for other easier to use and safer alternatives. The DOACs have been approved by the FDA for stroke prevention in NVAF since 2010. A meta-analysis of four landmark RCTs [RE-LY (dabigatran vs warfarin), ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban vs warfarin), ARISTOTLE (apixaban vs warfarin), and ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 (edoxaban vs warfarin)] in NVAF showed a reduction in hemorrhagic stroke risk by 50% with DOACs compared to warfarin (Ruff et al., 2014). As a result, DOACs have been increasingly used for NVAF-related stroke prevention in the United States and worldwide. However, warfarin remains as the only option for patients with mechanical heart valves with a target INR of 2.0–3.0 or 2.5–3.5, based on type and location of the heart valve prosthesis. Likewise, warfarin is the only OAC indicated for patients with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Current guidelines recommend DOACs and warfarin as first-line agents for stroke prevention in patients with NVAF who can tolerate long-term OAC use. Selecting the most appropriate DOAC should also be individualized based on specific features of every medication, as well as patients’ characteristics (Gokcal et al., 2018; Topcuoglu et al., 2018). The rates of DOACs discontinuation were high, similar to warfarin in all RCTs, and mostly due to hemorrhagic complications (Topcuoglu et al., 2018).

PREVENTION OF ISCHEMIC AND HEMORRHAGIC STROKES/EVENTS IN PATIENTS WITH AF AT HIGH HEMORRHAGIC RISK

Long-term use of OACs as first-line treatment for embolic prevention is an evidence-based approach in AF patients without high hemorrhage risk at baseline. This recommendation does not apply to patients with high bleeding risk, especially high ICH risk, as these were not included in the previously discussed RCTs, and moreover, because OACs known tendency to cause hemorrhages. Current guidelines recommend individualized shared decision making in choosing appropriate therapy after discussion of absolute and relative risks of stroke and bleeding as well as all alternative management options (January et al., 2014b). An FDA approved alternative that obviates the need for lifelong OAC use in NVAF patients with increased bleeding risk is closure of the LAA. At present, the only FDA approved device used for percutaneous LAAC is the WATCHMAN device (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts). The implantation of WATCHMAN device is typically performed by cardiac electrophysiologists and interventional cardiologists using transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiography. Local or general anesthesia is chosen based on the patient’s characteristics and implanter preference. After the procedure, warfarin with a target INR of 2–3 and aspirin 81 mg/day are used until follow-up transesophageal echocardiography, usually performed 45 days after implantation. When a good LAA seal (no connection or any jet larger than 5 mm in diameter between LAA and left atrium) is shown on echocardiography, warfarin therapy is switched to a combination of clopidogrel 75 mg/day and aspirin 81–325 mg/day for 4.5 months. After 6 months, patients are kept on aspirin only (Gurol, 2018). Although not used in RCTs, alternative regimens include use of a DOAC during the first 6–12 weeks or dual platelet antiaggregant for 3–6 months, switching to aspirin monotherapy afterwards based on single-arm studies and observational data (Reddy et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2019). The FDA recently updated indications for LAAC with WATCHMAN in a way DOACs can be used for the first 6 weeks after the implant instead of warfarin, so the DOAC use after the procedure is now an FDA-labeled approach (FDA, 2020). The PROTECT AF (Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System for Embolic Protection in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) study compared the LAAC procedure with warfarin in patients with AF who had a mean CHADS2 of 2.2 for the endpoints of stroke/embolism/death prevention (Holmes et al., 2009). A history of stroke or TIA was present in 19% of patients. In the warfarin arm, the mean time in therapeutic range was 66%, a value higher than the warfarin arms in DOAC studies except for the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48. During early phases of the trial, rate of procedural complication was relatively high. Despite that, the primary efficacy event rate was 3.0 per 100 patient-years (95% CI 1.9–4.5) in the intervention group vs 4.9 per 100 patient-years (95% CI 2.8–7.1) in the control group (RR: 0.62, 95% CI 0.35–1.25), confirming the noninferiority of LAAC to warfarin stroke prevention, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular/unexplained death. Study results showed similar ischemic stroke rates between the groups, but the ICH risk was significantly decreased with the use of the WATCHMAN device compared to warfarin (0.1 events per 100 patient-years [95% CI 0.0–0.5] vs 1.6 events per 100 patient-years [95% CI 0.6–3.1]). Cardiovascular and unexplained death rates were also significantly lower for the WATCHMAN arm (0.7 events per 100 patient-years [95% CI 0.2–1.5] vs 2.7 events per 100 patient-years [95% CI 1.2–4.4]). Furthermore, upon long-term follow-up (mean duration of 3.8 years), the primary event rate was 2.3 events per 100 patient-years, compared with 3.8 events per 100 patient-years with warfarin. These results fulfill criteria for both noninferiority and superiority, for preventing the combined outcome of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular death, as well as superiority for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (Reddy et al., 2014). In the PREVAIL trial (Watchman LAA Closure Device in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Vs Long Term Warfarin Therapy), there was an improvement in procedural safety, as only 2.2% of subjects experienced an event (Holmes et al., 2014). Based on these results, in March 2015, the FDA approved the use of WATCHMAN device for patients with NVAF at relatively high embolic risk who can use warfarin but who also have a reasonable rationale to avoid long-term anticoagulation.

A recent meta-analysis from two RCTs which included 1114 patients, mean follow-up of 5 years, showed that WATCHMAN significantly reduced hemorrhagic stroke (0.17 per 100 patient-years vs 0.87 per 100 patient-years, hazard ratio 0.20 [95% CI 0.07–0.56], P=0.002) while showing similar a trend for higher ischemic stroke or systemic embolism rates (1.6 per 100 patient-years vs 0.95 per 100 patient-years, hazard ratio 1.71 [95% CI 0.94–3.11], P=0.08) when compared to warfarin (Reddy et al., 2017a). All-cause stroke or systemic embolism was similar between WATCHMAN and warfarin (hazard ratio 0.96; P=0.87). Registry-based data from consecutive procedures in the United States (n=3822) and Europe (n=1021) showed satisfactory successful deployment rates (95.6% and 98.5%) and decreased procedural complication rates when compared with clinical trials: pericardial effusion/tamponade (1% and 0.3%), device embolization (0.24% and 0.2%), procedural stroke (0.08% and 0.1%), and death within 7 days (0.08% and 0.3%) (Boersma et al., 2016; Reddy et al., 2017b).

The new generation WATCHMAN device (WATCHMAN FLX) approved by the FDA in July 2020 represents a significant improvement over its predecessor as it has more available sizes improving fit and decreasing peridevice leaks, metal and contact point exposure is much lower enhancing the speed and completeness of the seal, and it can be readily recaptured, repositioned, and redeployed. The 7 days major complication rate of WATCHMAN FLX was 0.5%, based on the prospective “Investigational Device Evaluation of the WATCHMAN FLX™ LAA Closure Technology (PINNACLE FLX)” study that resulted into its FDA approval (https://clinicaltrials.gov, 2020). The Amulet IDE study for another endovascular LAAC device, AMPLATZER AMULET (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL, USA), has been completed and results are expected within the next 1–2 years. Other endovascular and epicardial LAAC devices being investigated include the Wavecrest device (Coherex Medical, Biosense Webster, Johnson & Johnson, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). All of these devices received “Conformité Européenne” mark approval and are available in Europe. The results of the phase 3 RCTs will further increase our understanding of the merits of LAAC using different devices as the use of implantable devices with different structure/shapes can further improve success rates in patients who have different LAA shapes/sizes.

The Left Atrial Appendage Closure vs. Novel Anticoagulation Agents in Atrial Fibrillation (PRAGUE-17) study compared LAAC (AMPLATZER AMULET or WATCHMAN) to long-term DOAC use head-to-head comparison for the first time (Osmancik et al., 2020). The study showed similar results for the occurrence of the primary composite outcome measures (stroke, TIA, systemic embolism, cardiovascular death, major or nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding, or procedure-/device-related complications) as well as ischemic event rates. After a median 20 months follow-up, the annual rates of the primary outcome were 10.99% with LAAC and 13.42% with DOAC (HR: 0.84; 95% CI 0.53–1.31; P=0.44; P=0.004 for noninferiority) (Osmancik et al., 2020). Two large-scale RCTs comparing the WATCHMAN FLX to DOACs (CHAMPION AF) and AMPLATZER AMULET to DOACs (CATALYST) are in the process of starting, both aiming to demonstrate noninferiority for ischemic event prevention and superiority of LAAC for major and clinically relevant hemorrhages in NVAF patients.

LAAC is an important method for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke prevention in NVAF patients who survived any ICH or major/relevant bleed or who have hemorrhage-prone brain conditions such as SVDs that put them at high ICH risk. There are other indications such as cognitive/gait problems, inability to use an OAC regularly, and any bleeding/fall risk that can jeopardize the patient’s well-being. Incorporating LAAC into shared decision-making discussions with appropriately selected NVAF patients helps improve the quality of patient care, allowing patients to make informed decisions for their preventive treatment.

RISK STRATIFICATION METHODS AND ANTIPLATELET USE

Platelet antiaggregants constitute the mainstay of arterial ischemic cardiovascular/cerebrovascular event prevention outside of AF, mechanical heart valve replacement, antiphospholipid syndrome, and few other indications that require anticoagulation or other advanced measures. Antiplatelet monotherapy has been used for many decades in hundreds of millions of patients. The indications are diverse ranging from coronary artery disease, ischemic cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease to other cardiac and vascular conditions. For these important indications, there is typically no alternative to antiplatelets except closure of a patent foramen ovale for secondary prevention after a cryptogenic stroke in patients between 18 and 60 years of age (Topcuoglu et al., 2018). Platelet antiaggregants are associated with a lower hemorrhagic risk when compared to anticoagulants. Long-term use of anticoagulant/antiplatelet combinations as well as dual antiplatelet therapies (DAPT) increase the hemorrhagic risk so limiting the duration of combined antithrombotic use to minimum required timeframes is always the ideal approach. In patients with cSVD-related recent lacunar strokes, the use of DAPT did not reduce recurrent ischemic stroke rate compared to antiplatelet monotherapy with aspirin 325 mg daily (SPS3 Investigators, 2012). Overall, escalating antithrombotic treatment should be avoided if possible in patients with hemorrhage-prone cSVDs, but antiplatelet monotherapy is used when there is a valid indication (Das et al., 2019). The ICH risk with antiplatelets has been reviewed in detail recently (Thon and Gurol, 2016). The risk/benefit ratio of platelet antiaggregant use in patients at high ICH risk has been better studied than anticoagulants in this context, but there is still no extensive RCT-based evidence. The effects of antiplatelet therapy after stroke due to ICH (RESTART) were a randomized open-label trial that excluded all but a very mild increase in the risk of recurrent ICH with antiplatelet therapy for patients on antithrombotic therapy for the prevention of occlusive vascular disease when they developed ICH (Salman et al., 2019). After suffering an ICH, 268 patients with valid indications for antiplatelet were assigned to start and 269 to avoid antiplatelet therapy. Over a median of 2 years follow-up, recurrent ICH rates were 4% in the antiplatelet arm vs 9% in the no-antiplatelet arm (adjusted hazard ratio 0.51 [95% CI 0.25–1.03]; P=0.060). Overall major hemorrhagic event rates were also numerically lower in the antiplatelet arm (7% vs 9%, P=0.27). When antiplatelet monotherapy is indicated based on current guidelines, such treatment is typically used unless there is a demonstrated excessive bleeding risk in the particular patient. Shared decision-making discussions between treating specialists, the patient and family are always important to determine benefits/risks and understand the patient’s preferences. Informing the patients and their families of concurrent risks is the physician’s duty, and an open discussion also increases patient satisfaction and therefore long-term compliance.

CONCLUSIONS

Accurate stratification of ICH risk as discussed throughout this article is of paramount importance to advise NVAF patients appropriately for LAAC or lifelong OAC use. Brain MRI imaging provides unprecedented opportunities to detect hemorrhage-prone diseases based on lesions such as microbleeds, superficial siderosis, and white matter disease. These markers can help understand hemorrhage risks even before a potentially fatal/disabling ICH happens. An operational understanding of the ischemic and hemorrhagic risk stratification tools can improve outcomes through selection of optimal preventive measures.

STUDY SUPPORT

This work was made possible by the following NIH grants: Gurol (NS083711, R01NS114526).

References

- Baczek VL, Chen WT, Kluger J et al. (2012). Predictors of warfarin use in atrial fibrillation in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract 13: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekwelem W, Connolly SJ, Halperin JL et al. (2015). Extracranial systemic embolic events in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Circulation 132: 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE et al. (2017). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135: e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshear JL, Odell JA (1996). Appendage obliteration to reduce stroke in cardiac surgical patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 61: 755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersma LV, Schmidt B, Betts TR et al. (2016). Implant success and safety of left atrial appendage closure with the WATCHMAN device: peri-procedural outcomes from the EWOLUTION registry. Eur Heart J 37: 2465–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R et al. (2012). 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation—developed with the special contribution of the European heart rhythm association. Europace 14: 1385–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha MJ, Park HE, Lee MH et al. (2014). Prevalence of and risk factors for silent ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation as determined by brain magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Cardiol 113: 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Haley K et al. (2016). White matter hyperintensity patterns in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology 86: 505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Roongpiboonsopit D et al. (2017a). Cortical superficial siderosis multifocality in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a prospective study. Neurology 89: 2128–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Xiong L et al. (2017b). Cortical superficial siderosis and first-ever cerebral hemorrhage in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 88:1607–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Heist EK, Galvin J et al. (2019). A comparison of postprocedural anticoagulation in high-risk patients undergoing WATCHMAN device implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 42: 1304–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AS, Regenhardt RW, Feske SK et al. (2019). Treatment approaches to lacunar stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28: 2055–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y et al. (2007). Death and disability from warfarin-associated intracranial and extracranial hemorrhages. Am J Med 120: 700–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (2020). Available: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/recently-approved-devices/watchman-left-atrial-appendage-closure-device-delivery-system-and-watchman-flx-left-atrial-appendage. Accessed 08.27 2020.

- Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Mosley TH Jr et al. (2012). Risk of intraparenchymal hemorrhage with magnetic resonance imaging-defined leukoaraiosis and brain infarcts. Ann Neurol 71: 552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamra H, Murin J, Chiang CE et al. (2014). Use of antithrombotics in atrial fibrillation in Africa, Europe, Asia and South America: insights from the International RealiseAF survey. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 107: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokcal E, Pasi M, Fisher M et al. (2018). Atrial fibrillation for the neurologist: preventing both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 18: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurol ME (2018). Nonpharmacological management of atrial fibrillation in patients at high intracranial hemorrhage risk. Stroke 49: 247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurol ME, Becker JA, Fotiadis P et al. (2016). Florbetapir-PET to diagnose cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a prospective study. Neurology 87: 2043–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusler KG, Wilson D, Fiebach JB et al. (2014). Brain MRI to personalise atrial fibrillation therapy: current evidence and perspectives. Heart 100: 1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI (2007). Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 146: 857–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill JC 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS et al. (2015). Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 46: 2032–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi Z, Oldgren J, Siegbahn A et al. (2013). Biomarkers in atrial fibrillation: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 34: 1475–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi Z, Siegbahn A, Andersson U et al. (2014a). High-sensitivity troponin I for risk assessment in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial. Circulation 129: 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi Z, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A et al. (2014b). High-sensitivity troponin T and risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation during treatment with apixaban or warfarin. J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi Z, Lindback J, Alexander JH et al. (2016). The ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history) stroke risk score: a biomarker-based risk score for predicting stroke in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 37: 1582–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes Jr, Kar S, Price MJ et al. (2014). Prospective randomized evaluation of the watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DR, Reddy VY, Turi ZG et al. (2009). Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 374: 534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://clinicaltrials.gov Available https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02702271 Accessed 08.27. 2020.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS et al. (2014a). 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 130: e199–e267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS et al. (2014b). 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 130: 2071–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H et al. (2019). 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 74: 104–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar AK, Mueller I, Bassand JP et al. (2013). Risk profiles and antithrombotic treatment of patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: perspectives from the international, observational, prospective GARFIELD registry. PLoS One 8: e63479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR et al. (2014). Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45: 2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T et al. (2005). Atrial fibrillation as a predictive factor for severe stroke and early death in 15,831 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76: 679–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D et al. (2001). Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: validation of the Boston criteria. Neurology 56: 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DA, Lip GY (2012). Use of the CHA(2)DS(2)-VASc and HAS-BLED scores to aid decision making for thromboprophylaxis in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 126: 860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Ryu WS, Roh JK (2009). Cerebral microbleeds are a risk factor for warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 72: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung M, van Rosendael PJ, Abou R et al. (2018). Left atrial function to identify patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of stroke: new insights from a large registry. Eur Heart J 39: 1416–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn J, Halpin A, Demaerel P et al. (2010). Prevalence of superficial siderosis in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 74: 1346–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupercio F, Carlos Ruiz J, Briceno DF et al. (2016). Left atrial appendage morphology assessment for risk stratification of embolic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm 13: 1402–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini C, De Santis F, Sacco S et al. (2005). Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke 36: 1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti-Fabregas J, Medrano-Martorell S, Merino E et al. (2019). MRI predicts intracranial hemorrhage in patients who receive long-term oral anticoagulation. Neurology 92: e2432–e2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B et al. (2014). Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45: 3754–3832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al. (2016). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133: e38–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldgren J, Hijazi Z, Lindback J et al. (2016). Performance and validation of a novel biomarker-based stroke risk score for atrial fibrillation. Circulation 134: 1697–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P et al. (2020). Left atrial appendage closure versus direct oral anticoagulants in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 75: 3122–3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L (2010). Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol 9: 689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasi M, Charidimou A, Boulouis G et al. (2018). Mixed-location cerebral hemorrhage/microbleeds: underlying microangiopathy and recurrence risk. Neurology 90: e119–e126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza G, Karipineni N, Goldberg HS et al. (2016). Underutilization of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 2444–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Providencia R, Trigo J, Paiva L et al. (2013). The role of echocardiography in thromboembolic risk assessment of patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26: 801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VY, Mobius-Winkler S, Miller MA et al. (2013). Left atrial appendage closure with the watchman device in patients with a contraindication for oral anticoagulation: the ASAP study (ASA Plavix feasibility study with watchman left atrial appendage closure technology). J Am Coll Cardiol 61: 2551–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J et al. (2014). Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 312: 1988–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S et al. (2017a). 5-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: from the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 70: 2964–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VY, Gibson DN, Kar S et al. (2017b). Post-approval U.S. experience with left atrial appendage closure for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Caravaca JM, Marin F, Vilchez JA et al. (2019). Refining stroke and bleeding prediction in atrial fibrillation by adding consecutive biomarkers to clinical risk scores. Stroke 50: 1372–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roongpiboonsopit D, Charidimou A, William CM et al. (2016). Cortical superficial siderosis predicts early recurrent lobar hemorrhage. Neurology 87: 1863–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA et al. (2004). The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 164: 880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E et al. (2014). Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 383: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman RA- S, Dennis M, Sandercock P, et al. (2019). Effects of antiplatelet therapy after stroke due to intracerebral haemorrhage (RESTART): a randomised, open-label trial. The Lancet 393: 2613–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer DE, Chang Y, Borowsky LH et al. (2013). A new risk scheme to predict ischemic stroke and other thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: the ATRIA study stroke risk score. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Rosand J, Knudsen KA et al. (2002). Leukoaraiosis is associated with warfarin-related hemorrhage following ischemic stroke. Neurology 59: 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA et al. (2004). White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 63: 1606–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPS3 Investigators (2012). Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 367: 817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner T, Rosand J, Diringer M (2006). Intracerebral hemorrhage associated with oral anticoagulant therapy: current practices and unresolved questions. Stroke 37: 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon JM, Gurol ME (2016). Intracranial hemorrhage risk in the era of antithrombotic therapies for ischemic stroke. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 18: 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topcuoglu MA, Liu L, Kim DE et al. (2018). Updates on prevention of cardioembolic strokes. J Stroke 20: 180–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HH, Pasi M, Tsai LK et al. (2019). Microangiopathy underlying mixed-location intracerebral hemorrhages/microbleeds: a PiB-PET study. Neurology 92: e774–e781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Etten ES, Auriel E, Haley KE et al. (2014). Incidence of symptomatic hemorrhage in patients with lobar microbleeds. Stroke 45: 2280–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT Jr, Koudstaal PJ (2007). Silent brain infarcts: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 6: 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinereanu D, Lopes RD, Mulder H et al. (2017). Echocardiographic risk factors for stroke and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation anticoagulated with apixaban or warfarin. Stroke 48: 3266–3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ et al. (2013). Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 12: 822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Charidimou A, Ambler G et al. (2016). Recurrent stroke risk and cerebral microbleed burden in ischemic stroke and TIA: a meta-analysis. Neurology 87: 1501–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Ambler G, Shakeshaft C et al. (2018). Cerebral microbleeds and intracranial haemorrhage risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation after acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (CROMIS-2): a multicentre observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 17: 539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]