Abstract

Therapeutic advances for glioblastoma have been minimal over the past 2 decades. In light of the multitude of recent phase III trials that have failed to meet their primary endpoints following promising preclinical and early-phase programs, a Society for Neuro-Oncology Think Tank was held in November 2020 to prioritize areas for improvement in the conduct of glioblastoma clinical trials. Here, we review the literature, identify challenges related to clinical trial eligibility criteria and trial design in glioblastoma, and provide recommendations from the Think Tank. In addition, we provide a data-driven context with which to frame this discussion by analyzing key study design features of adult glioblastoma clinical trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov as “recruiting” or “not yet recruiting” as of February 2021.

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant primary brain tumor in adults and remains incurable (1, 2). Despite considerable progress in understanding the biology of glioblastoma (3–9), there have been no regulatory drug approvals since bevacizumab in the United States in 2009 (10), and a multitude of recent phase III clinical trials did not meet their prespecified primary endpoints (11–16). This disconnect between the urgent unmet need, growing scientific understanding of the disease, and lack of translation into effective novel therapies can be attributed to many causes, some of which are related to the difficult biology and clinical challenges inherent to glioblastoma. However, glioblastoma clinical trial design has also attracted significant recent scrutiny and may represent an important barrier to progress (17–25). Key problems include a paucity of control arms in phase II trials (18, 25), overly stringent clinical eligibility criteria and insufficient patient and provider participation (19, 20), inadequate assessment of brain penetration (26, 27) and pharmacodynamics (28, 29) of new drugs, inefficient clinical trial infrastructure (30), and limited development and implementation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers (31–37). Concerted efforts have started to address some of these, including a push toward adaptive platform trials (38–40) and joint publications from neuro-oncology professional societies and clinical trial consortia (19, 20).

A Think Tank was held by the Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) in 2020 to better define these barriers and to outline a road map for improving translation of discoveries into effective glioblastoma therapies. Participants included scientists, representatives from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and pharmaceutical industry, patient advocacy groups, and clinical trialists from both within and outside the field of neuro-oncology. The concluding session, Thinking Outside the Box, served as a summary session to cover the key issues and is the focus of this review. Issues covered in the other sessions are reviewed in separate articles: one on combination immunotherapy is published jointly with this article, and one on combination therapies in general is already published (41). Here, we first summarize key features of currently recruiting and soon-to-be recruiting glioblastoma clinical trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, including the type of experimental therapy, key study design parameters, primary endpoints, and eligibility criteria, providing a current snapshot of the glioblastoma clinical trials landscape. We then review the relevant literature and summarize the SNO 2020 Think Tank with regard to (1) optimizing eligibility criteria to increase enrollment and generalizability of trial results, and (2) optimizing study designs to provide an accurate assessment of efficacy before conducting a phase III study.

Review of Currently Enrolling Glioblastoma Clinical Trials

This section includes an analysis of key study design elements for glioblastoma clinical trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov as “recruiting” or “not yet recruiting.” These data provide a real-world context to frame key discussion points that emerged from the Think Tank. Similar analyses have been performed by Vanderbeek and colleagues (25) and Cihoric and colleagues (42), although these studies only included trials initiated through 2016 and 2015, respectively. ClinicalTrials.gov was queried on February 10, 2021, for interventional trials with therapeutic intent enrolling patients >18 years old with glioblastoma.

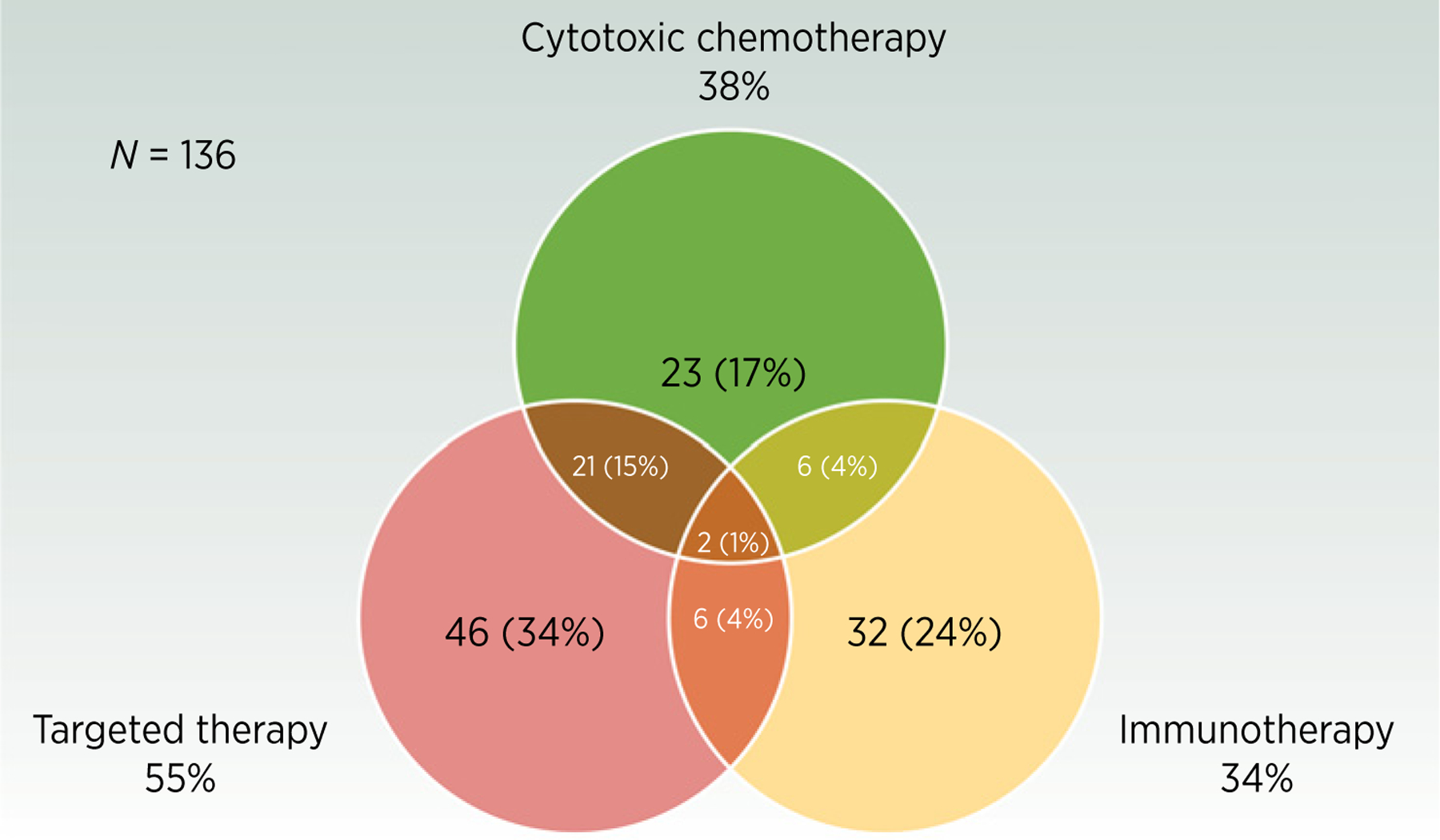

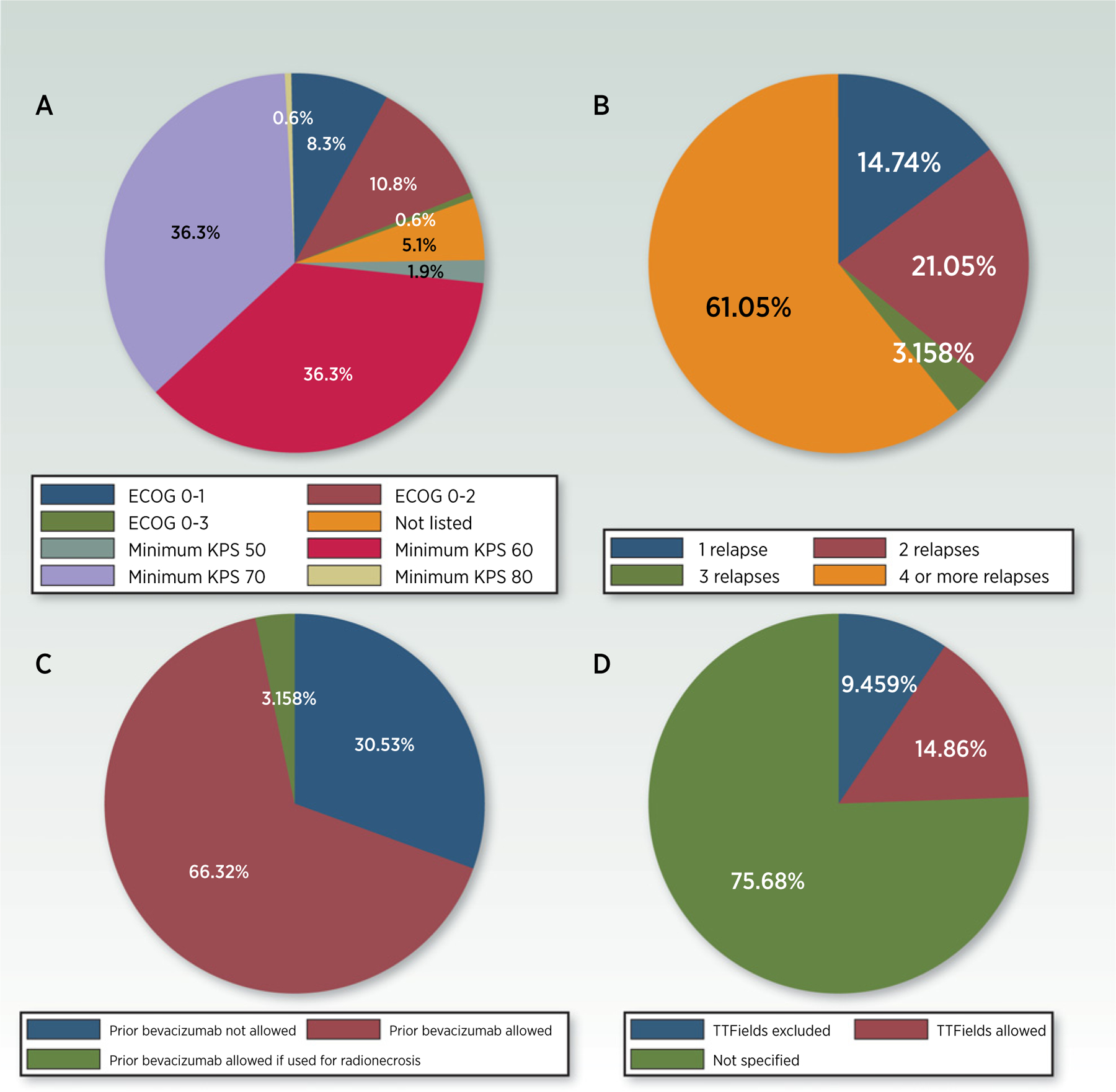

One hundred fifty-seven clinical trials were identified. Key characteristics are listed in Table 1. The majority (92%) were phase I, I/II, or II, and over half had primary outcome measures related to toxicity, safety, and/or dose finding. Of the 76 phase I/II or phase II trials, 66 (87%) did not have a control arm and 63 (83%) were nonrandomized. Among phase I/II and II trials with an efficacy endpoint listed as the primary outcome measure (n = 60), the primary outcome measures were overall survival (OS) in 24 trials (40%), progression-free survival (PFS) in 16 (27%), objective response rate (ORR) in 13 (22%), and disease control rate (DCR) in two (3%). The types of therapy being evaluated in systemic therapy trials (n = 136) are displayed in Fig. 1 and key inclusion/exclusion criteria in Fig. 2. In trials for recurrent glioblastoma (n = 84), 31 (37%) specified that both standard-dose radiotherapy to 60 Gy and temozolomide were required as prior therapy to be eligible, 31 (37%) specified that any dose of prior radiotherapy with or without temozolomide was acceptable, and 22 (26%) did not specify this one way or the other.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of current adult glioblastoma clinical trials.

| Characteristic | All trials (N = 157) |

|---|---|

| Median time on ClinicalTrials.gov, mo (range, IQR) | 25.8 (0–121.4, 9.4–43.1) |

| Status, n (%) | |

| Currently recruiting | 141 (90) |

| Not yet recruiting | 16 (10) |

| Phase, n (%) | |

| 0/I | 3 (2) |

| 0/II | 2 (1) |

| I | 68 (43) |

| I/II | 25 (16) |

| II | 51 (33) |

| II/III | 2 (1) |

| III | 4 (3) |

| Not listed | 2 (1) |

| Tumor type, n (%) | |

| Glioma-specific | 142 (90) |

| Solid tumor trial with glioblastoma arm(s) | 15 (10) |

| Type of therapy, n (%) | |

| Systemic | 136 (87) |

| Radiotherapy | 57 (36) |

| Systemic + radiotherapy | 50 (32) |

| Neoadjuvant/window-of-opportunity cohort | 36 (23) |

| Intracerebral delivery | 14 (9) |

| Tumor-treating fields | 13 (8) |

| Sponsor, n (%) | |

| Investigator/foundation/NCI | 120 (76) |

| Industry | 37 (24) |

| Study centers, n (%) | |

| Single center | 95 (61) |

| Multicenter | 62 (39) |

| Median number of centers (range, IQR) | 5 (2–331, 3–12) |

| Disease setting, n (%) | |

| Newly diagnosed glioblastoma | 64 (41) |

| Specific for MGMT unmethylated glioblastoma | 32 (20) |

| Recurrent glioblastoma | 84 (53) |

| Both newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma | 9 (6) |

| Allows IDH-mutant glioblastoma, n (%) | |

| Yes | 28 (18) |

| No | 17 (11) |

| Not specified | 111 (71) |

| Allowed for phase I, excluded for phase II | 1 (0.6) |

| Allows molecular glioblastoma, defined by c-IMPACT NOW, n (%) | |

| Yes | 45 (29) |

| No | 90 (57) |

| Not specified | 19 (12) |

| Not applicable | 3(2) |

| Requires standard of care with 60-Gy radiation and temozolomide (as part of regimen for newly diagnosed trial, or as prior therapy for recurrent trial), n (%) | |

| Yes | 84 (54%) |

| No | 45 (29%) |

| Not specified | 25 (16%) |

| Yes for new treatment, no for recurrence | 2 (1%) |

| Excludes multifocal disease, n (%) | 34 (22%) |

| Includes control arm, n (%) | 18 (11) |

| Internal control arm | 14 (9) |

| External control arm | 4 (2) |

| Randomized trial, n (%) | 28 (18) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NCI, National Cancer Institute; MGMT, O(6)-methylguanine–DNA methyltransferase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; c-IMPACT NOW, Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS Tumor Taxonomy—Not Officially WHO.

Figure 1.

Type of systemic therapy administered in glioblastoma clinical trials that include a systemic therapy component (n = 136).

Figure 2.

Key eligibility criteria in current glioblastoma clinical trials. A, Required minimum performance status (all trials; N = 157). B, Number of prior relapses permitted (recurrent glioblastoma trials; n = 93). C, Allowance for prior bevacizumab (recurrent glioblastoma trials; n = 93). D, Allowance of TTFields (newly diagnosed glioblastoma trials; n = 73).

Discussion of Select Challenges in Glioblastoma Clinical Trial Conduct

Overly restrictive eligibility criteria

Although restrictive eligibility to clinical trials is only one barrier to participation, unnecessarily restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria limit the number of patients who can enroll and potentially benefit from investigational therapy, a critical factor in glioblastoma given that only 21% of patients with primary brain tumors participate in clinical trials (20). Overly selective eligibility criteria also reduce the generalizability of results (43), presenting a potential problem when “positive” phase II results from a single academic center are put to the test in a randomized phase III trial. With wider recognition of these issues, there has been a recent push to broaden eligibility criteria, both across oncology (43) and in neuro-oncology specifically (19). In 2016, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), Friends of Cancer Research, and the FDA formed a collaboration to address overly restrictive cancer clinical trial eligibility criteria, leading to published recommendations for more inclusive eligibility criteria (44) and updated recommendations in 2021 (45).

Certain eligibility criteria are particularly relevant in neuro-oncology. In recurrent glioblastoma trials, details related to patients’ prior therapies are important for determining eligibility. This includes the type of first-line therapy received, number of prior relapses, and previous use of bevacizumab (19). Following maximal safe surgical resection, the widely accepted standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma includes radiotherapy to 60 Gy with concurrent temozolomide followed by six maintenance temozolomide cycles (46). However, variations of this regimen are used in clinical practice and supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and other guidelines (1), including hypofractionated radiation (e.g., 40 Gy delivered in 15 fractions) in elderly patients (47) and omission of temozolomide in patients with MGMT unmethylated tumors (48). As a result, requiring previous receipt of traditional standard of care is seldom necessary from a scientific standpoint and may unnecessarily exclude a large percentage of patients who would otherwise be eligible (19). In addition, the types of therapies received for prior relapses of glioblastoma and their impact on the ability to respond to the experimental treatment should play a greater role in determining eligibility than the number of prior relapses, which itself may have little effect on treatment response (19). A key example is use of bevacizumab, as bevacizumab-refractory disease may harbor unique biology (49) and rarely responds to further salvage therapy (50). Thus, it has been suggested that for phase I trials with primary endpoints related to dose finding and safety, an unlimited number of prior relapses and therapies (including bevacizumab) should be allowed (19). Conversely, phase II/III efficacy studies might allow a limited number of relapses (e.g., up to two) in bevacizumab-naïve patients and need to determine on a trial-by-trial basis whether to exclude or stratify by prior bevacizumab (19).

Another particularly relevant eligibility criterion for glioblastoma clinical trials is the performance score (PS). In patients with glioblastoma, poor PS directly attributable to a fixed neurologic deficit may not accurately represent the patient’s appropriateness for receiving experimental therapy. This unique feature of brain tumor patients requires that each glioblastoma clinical trial carefully considers the cutoff point for PS that will be used to establish eligibility. Others have recommended (19), and we agree, that patients with primary brain tumors with lower PS (as low as Karnofsky performance status of 60) due to fixed neurologic deficits can be accrued to phase I trials without affecting the study’s integrity.

We also found that approximately one-third of recurrent glioblastoma clinical trials required that patients previously completed radiation to 60 Gy with temozolomide, regardless of age and MGMT methylation status. This points to one area for improvement because in most early-phase recurrent glioblastoma trials, there is no scientific rationale to eliminate patients from participation on the basis of having previously received less than 60 Gy of radiation and/or no temozolomide. Moreover, it seems unfair to exclude otherwise eligible patients from participation simply because they received a variation on standard of care that was tailored to their individual circumstances (e.g., 40 Gy in the elderly or omission of temozolomide in MGMT unmethylated patients) and has been widely viewed as acceptable first-line treatment across the field of neuro-oncology. At the same time, we found that other key clinical inclusion/exclusion criteria are less stringent, a sign that investigators may be more carefully considering the issue of generalizability when designing studies. These include allowance for a Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) of 60 in nearly half of all glioblastoma trials and allowance for prior bevacizumab use in about two thirds of recurrent glioblastoma trials. Our analysis also found that 47% of current glioblastoma clinical trials are for newly diagnosed disease. This reflects a recent shift toward more clinical trials being offered in the newly diagnosed setting as opposed to recurrence, as a previous study noted that only one third of all glioblastoma trials between 2005 and 2016 were for newly diagnosed disease (25). Although this may allow enrollment of patients earlier in the disease course when they are generally healthier and better able to tolerate treatment, it also carries important implications for clinical trial design (18), including eligibility criteria. For example, the majority of newly diagnosed glioblastoma trials make no mention of whether tumor-treating fields (TTFields) are allowed or excluded. Although TTFields are approved by the FDA based on a previously demonstrated OS benefit (51), this therapy is not used in a substantial proportion of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (52). The question of whether to allow use of TTFields in upfront glioblastoma clinical trials needs to be addressed individually for each study based on its specific scientific and clinical concerns. However, both patient and clinician decision-making would benefit from greater clarity regarding whether or not TTFields are allowed in a given trial.

Inadequate phase II study designs

Compared with randomized studies, single-arm phase II trials require significantly fewer patients and resources and can be opened and completed fairly rapidly at a single institution. However, it is generally agreed upon that the abundance of single-arm efficacy studies with primary endpoint analysis based on historical controls has generated an inadequate phase II program in glioblastoma (17, 18, 21, 22, 25). Issues with single-arm phase II designs for glioblastoma trials include a lack of reliable historical controls for most protocols (ref. 53; particularly since the WHO revised classification of central nervous system tumors in 2016 and subsequent updates from the Consortium to Inform Molecular and Practical Approaches to CNS Tumor Taxonomy [cIMPACT-NOW] working group; refs. 54, 55), selection bias (23, 56), and patient temporal drift (57, 58). As a result of these limitations, single-arm phase II studies have a high risk of leading to incorrect go/no-go decision-making for phase III (25, 59). In 2018, two studies were published analyzing the phase II–III transition in glioblastoma (22, 25). Mandel and colleagues examined the ability of positive phase II studies in glioblastoma to predict positive phase III studies. The authors identified seven phase III clinical trials in newly diagnosed glioblastoma and four phase III trials in recurrent glioblastoma over the prior 25 years, all of which were preceded by positive phase II studies; only one (9%) phase III study was subsequently positive (22). Of the seven phase III trials in newly diagnosed glioblastoma, 12 prior positive phase II studies were cited as justification for phase III. Of the 12 phase II studies, PFS or OS were the primary endpoints in nine studies (75%), and historical control groups were used for comparison in nine studies (75%). Moreover, the authors found that more than half (12/23) of all phase III trials in glioblastoma proceeded without a prior phase II study being performed or with a negative phase II study. Around the same time, Vanderbeek and colleagues analyzed glioblastoma clinical trials conducted from 2005 to 2016 and found that of the eight completed phase III trials, only one reported positive results (25). Although 58% of the phase III trials were supported by positive phase II data with a similar endpoint, only 25% of these phase II trials were randomized.

Since these publications, six additional negative phase III trials have been reported (11–16). The first of these was a randomized, double-blind phase III trial of rindopepimut with temozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma (13). This trial was preceded by two small single-arm phase II trials (60, 61), as well as a larger phase II trial that was initially randomized was but was converted to a single-arm design after nearly all of the first 16 patients enrolled to the standard-of-care temozolomide arm voluntarily withdrew (62). The patients enrolled on these single-arm studies showed encouraging median PFS/OS compared with contemporary patient cohorts receiving standard of care. The second trial was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of personalized peptide vaccination in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (14), which followed a phase I study demonstrating feasibility and encouraging OS (although median PFS was only 2.3 months; ref. 63). The third trial, presented but not yet published at the time of this review, was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of depatuximab mafodotin (ABT-414) in EGFR–amplified, newly diagnosed glioblastoma (15). This study came on the heels of phase I data in both the newly diagnosed (64) and recurrent settings (65), with single-arm efficacy data demonstrating potentially encouraging PFS rate at 6 months (PFS-6) and a small number of objective responses (64–66). The fourth study was a randomized trial of nivolumab versus bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (11). This trial followed only a phase I study demonstrating the safety of nivolumab in this population (67), without supporting phase II efficacy data. The fifth study was a seamless phase II/III randomized-controlled trial of vocimagene amiretrorepvec (Toca 511) with flucytosine versus standard-of-care physician’s choice chemotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma (12), which followed phase I data demonstrating a subset of patients experiencing multiyear durable responses (68, 69). The sixth and final study was a randomized trial of temozolomide-based chemoradiotherapy with versus without marizomib in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (16). This study, presented but not yet published, was launched based on the results of a phase I trial of marizomib in combination with bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (70), which demonstrated a PFS-6 (39%) that compared favorably with the expected PFS-6 from bevacizumab alone (16%; ref. 71).

Although the reasons for these trials not meeting their endpoints are numerous and complex, these recent negative phase III studies, taken together with those of the prior 2 decades, should generate further caution about proceeding to phase III studies based on only single-arm phase I/II data. Interestingly, this point is underscored even by one of the few phase III trials in glioblastoma that actually met its primary endpoint: CeTeG/NOA-09, a phase III randomized trial of lomustine-temozolomide versus temozolomide alone in newly diagnosed, MGMT-methylated glioblastoma (72). This study, like many of those described above, was launched based on the results of a single-arm phase II trial (73). Although it was technically a positive study, the difference in OS between the two arms barely reached statistical significance. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval for relative risk of death was wide and crossed 1.0, and there was no difference in PFS between the two arms. Due to these limitations, it is unclear whether the study’s findings are clinically meaningful, and it is unlikely to change practice unless the results are reproduced in a larger study.

In our analysis of currently enrolling glioblastoma clinical trials, only 11% included a control arm of any sort, and just 18% were randomized. This is in part related to the fact that nearly half of all glioblastoma clinical trials are phase I and thus expected to be nonrandomized and lack control arms. However, 87% of all the phase I/II or phase II trials also did not have a control arm, and 83% of these were nonrandomized. Although this finding is not new, it is remarkable that, despite widespread recognition of this problem and frequent calls for change, nearly all glioblastoma phase II studies remain single arm. Although this may be less of a concern for phase II trials using objective response as the primary endpoint (assuming the experimental agent does not have antiangiogenic properties that may cause “pseudo-response”; ref. 74), approximately two-thirds of the phase II trials identified in our analysis used time-to-event outcomes, which can have more variance unrelated to the experimental treatment.

Despite the clear benefits to control arms in phase II studies, there are multiple potential barriers to their use. The first is patient and clinician dissatisfaction with randomization to a standard-of-care arm that can be perceived as ineffective or marginally effective. This is especially pertinent in glioblastoma, as agents with meaningful activity in the relapsed setting are generally lacking (75). Second, randomized studies often require larger, multicenter patient cohorts and longer timeframes. Although there are cooperative group mechanisms, there remains, at least in the United States, a need for more robust and interconnected clinical trial infrastructure across brain tumor centers to facilitate collaboration and multicenter studies. Adaptive platform trials, such as GBM AGILE or INSIGhT, have been implemented as potential solutions to some of these problems. GBM AGILE is a global trial for both newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma that involves testing novel therapies in an initial Bayesian adaptively randomized screening stage to detect signals of efficacy based on comparing OS with the experimental agent to that achieved by patients enrolled on a common control arm (38). Highly effective therapies seamlessly transition to a secondary confirmatory stage in the identified population of interest, wherein fixed randomization is used to confirm the findings from the first stage. Such a design allows for numerous therapeutic arms to be added and deleted from the study over time, potentially speeding up the drug development process for glioblastoma. In addition, control therapy is assigned to only 20% of the patients throughout the trial, which may make the study more appealing for patients compared with a fixed 50% chance of being randomized to a control arm on most trials. Beyond adaptive platform trials, another possible path forward is to increase the use of hybrid randomized-controlled/externally controlled trials (76). We also recommend that cooperative groups work together to set national goals and priorities regarding the specific trials to be conducted within in a specific time frame (e.g., 5 years); each cooperative group would lead at least one of these trials and participate in all of them. The NCI National Clinical Trials Network provides a ready mechanism for this type of cross-cooperative group collaboration and clinical trial participation (77).

Conclusions

Many biological factors of glioblastoma have contributed to the relative lack of progress over the past 2 decades. However, successful development of new therapies also requires that clinical trials open and accrue efficiently, are adequately designed and powered to answer relevant scientific questions, and yield generalizable results. In this review, we found that phase II glioblastoma trials continue to be conducted largely in single-center settings and with single-arm designs, placing the field at risk for continued late phase trial failures and beleaguered drug development. To develop effective therapies and avoid wastage of precious patient and financial resources, investigators should carefully consider eligibility criteria to enhance trial enrollment and generalizability. In addition, most phase II studies, in particular those for newly diagnosed glioblastoma or for recurrent glioblastoma with PFS or OS-based endpoints, should be randomized, controlled, and sufficiently powered. However, there remain many unanswered questions that will need to be addressed by the neuro-oncology community to achieve tangible progress in the field (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unanswered questions and areas of future methodological research in glioblastoma clinical trials.

| Category | Key unanswered questions |

|---|---|

| Study design, endpoints, and statistics | Should we give more consideration to patient-reported outcomes making in go/no-go decisions? |

| When can we use external control arms and what are the challenges? | |

| Are there specific scenarios where a singlearm phase II study may be used with confidence to cease or advance a new therapy? | |

| How much improvement in PFS, OS, and ORR compared with standard-of-care therapies should be considered enough to move a therapy from phase II to phase III? | |

| How can combination therapies be efficiently evaluated in the context of an adaptive platform trial? | |

| Infrastructure and accrual | Should pathologic, molecular, and radiologic evaluations be centralized? |

| Beyond relaxing eligibility criteria, how else can we enhance patient participation in clinical trials? | |

| There is a clear need for more multicenter trials; how can we mitigate the complicated bureaucracy and higher costs involved? | |

| With molecular testing becoming mainstream, any cancer can be considered a collection of rare cancers; how can we have a better representation of shrinking subsets of molecular subtypes in clinical trials? |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Society for Neuro-Oncology and their staff for their tremendous contributions to the arrangements and coordination for the Think Tank meeting.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, Alexander BM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Barthel FP, et al. Glioblastoma in adults: a Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol 2020;22:1073–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, Le Rhun E, Tonn JC, Minniti G, et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021;18:170–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 2013;155:462–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M, Scarpace L, et al. Tumor evolution of glioma-intrinsic gene expression subtypes associates with immunological changes in the microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2018;33:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V, Schrimpf D, Sturm D, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 2018;555:469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pine AR, Cirigliano SM, Nicholson JG, Hu Y, Linkous A, Miyaguchi K, et al. Tumor microenvironment is critical for the maintenance of cellular states found in primary glioblastomas. Cancer Discov 2020;10:964–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatesh HS, Morishita W, Geraghty AC, Silverbush D, Gillespie SM, Arzt M, et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 2019;573:539–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cloughesy TF, Mochizuki AY, Orpilla JR, Hugo W, Lee AH, Davidson TB, et al. Neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 immunotherapy promotes a survival benefit with intratumoral and systemic immune responses in recurrent glioblastoma. Nat Med 2019;25:477–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chongsathidkiet P, Jackson C, Koyama S, Loebel F, Cui X, Farber SH, et al. Sequestration of T cells in bone marrow in the setting of glioblastoma and other intracranial tumors. Nat Med 2018;24:1459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reardon DA, Brandes AA, Omuro A, Mulholland P, Lim M, Wick A, et al. Effect of nivolumab vs bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the CheckMate 143 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6: 1003–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cloughesy TF, Petrecca K, Walbert T, Butowski N, Salacz M, Perry J, et al. Effect of vocimagene amiretrorepvec in combination with flucytosine vs standard of care on survival following tumor resection in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1939–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weller M, Butowski N, Tran DD, Recht LD, Lim M, Hirte H, et al. Rindopepimut with temozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma (ACT IV): a randomised, double-blind, international phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narita Y, Arakawa Y, Yamasaki F, Nishikawa R, Aoki T, Kanamori M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of personalized peptide vaccination for recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:348–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassman A, Pugh S, Wang T, Aldape K, Gan H, Preusser M, et al. Actr-21: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplified (AMP) newly diagnosed glioblastoma (nGBM). Neuro-oncol 2019;21:vi17–vi. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth P, Gorlia T, Reijneveld JC, Vos FYFLD, Idbaih A, Frenel J-S, et al. EORTC 1709/CCTG CE.8: a phase III trial of marizomib in combination with temozolomide-based radiochemotherapy versus temozolomide-based radio-chemotherapy alone in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balasubramanian A, Gunjur A, Hafeez U, Menon S, Cher LM, Parakh S, et al. Inefficiencies in phase II to phase III transition impeding successful drug development in glioblastoma. Neurooncol Adv 2021;3:vdaa171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grossman SA, Schreck KC, Ballman K, Alexander B. Point/counterpoint: randomized versus single-arm phase II clinical trials for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:469–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee EQ, Weller M, Sul J, Bagley SJ, Sahebjam S, van den Bent M, et al. Optimizing eligibility criteria and clinical trial conduct to enhance clinical trial participation for primary brain tumor patients. Neuro Oncol 2020;22: 601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee EQ, Chukwueke UN, SL H-J, de Groot JF, Leone JP, Armstrong TS, et al. Barriers to accrual and enrollment in brain tumor trials. Neuro Oncol 2019;21: 1100–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mandel JJ, Youssef M, Ludmir E, Yust-Katz S, Patel AJ, De Groot JF. Highlighting the need for reliable clinical trials in glioblastoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2018;18:1031–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandel JJ, Yust-Katz S, Patel AJ, Cachia D, Liu D, Park M, et al. Inability of positive phase II clinical trials of investigational treatments to subsequently predict positive phase III clinical trials in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;20: 113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skaga E, Skretteberg MA, Johannesen TB, Brandal P, Vik-Mo EO, Helseth E, et al. Real-world validity of randomized controlled phase III trials in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: to whom do the results of the trials apply? Neurooncol Adv 2021;3: vdab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taslimi S, Ye V, Zadeh G. Lessons learned from contemporary glioblastoma randomized clinical trials through systematic review and network meta-analysis: Part 1 Newly diagnosed disease. Neuro-Oncology Advances 2021;3: vdab028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderbeek AM, Rahman R, Fell G, Ventz S, Chen T, Redd R, et al. The clinical trials landscape for glioblastoma: is it adequate to develop new treatments? Neuro Oncol 2018;20:1034–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karmur BS, Philteos J, Abbasian A, Zacharia BE, Lipsman N, Levin V, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption in neuro-oncology: strategies, failures, and challenges to overcome. Front Oncol 2020;10:563840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grossman SA, Romo CG, Rudek MA, Supko J, Fisher J, Nabors LB, et al. Baseline requirements for novel agents being considered for phase II/III brain cancer efficacy trials: conclusions from the Adult Brain Tumor Consortium’s first workshop on CNS drug delivery. Neuro-oncol 2020;22:1422–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen PY. Positron emission tomography imaging of drug concentrations in the brain. Neuro Oncol 2021;23:537–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogelbaum MA, Krivosheya D, Borghei-Razavi H, Sanai N, Weller M, Wick W, et al. Phase 0 and window of opportunity clinical trial design in neuro-oncology: a RANO review. Neuro Oncol 2020;22:1568–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aldape K, Brindle KM, Chesler L, Chopra R, Gajjar A, Gilbert MR, et al. Challenges to curing primary brain tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16: 509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson RM, Phillips HS, Bais C, Brennan CW, Cloughesy TF, Daemen A, et al. Development of a gene expression–based prognostic signature for IDH wild-type glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol 2020;22:1742–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob F, Salinas RD, Zhang DY, Nguyen PTT, Schnoll JG, Wong SZH, et al. A patient-derived glioblastoma organoid model and biobank recapitulates inter-and intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Cell 2020;180:188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynes JP, Nwankwo AK, Sur HP, Sanchez VE, Sarpong KA, Ariyo OI, et al. Biomarkers for immunotherapy for treatment of glioblastoma. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghiaseddin A, Hoang Minh LB, Janiszewska M, Shin D, Wick W, Mitchell DA, et al. Adult precision medicine: learning from the past to enhance the future. Neurooncol Adv 2021;3:vdaa145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dejaegher J, Solie L, Hunin Z, Sciot R, Capper D, Siewert C, et al. DNA methylation based glioblastoma subclassification is related to tumoral T-cell infiltration and patient survival. Neuro Oncol 2021;23:240–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park AK, Kim P, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y, Zhao Z. Subtype-specific signaling pathways and genomic aberrations associated with prognosis of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kickingereder P, Neuberger U, Bonekamp D, Piechotta PL, Götz M, Wick A, et al. Radiomic subtyping improves disease stratification beyond key molecular, clinical, and standard imaging characteristics in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;20:848–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexander BM, Ba S, Berger MS, Berry DA, Cavenee WK, Chang SM, et al. Adaptive global innovative learning environment for glioblastoma: GBM AGILE. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexander BM, Trippa L, Gaffey S, IC A-R, Lee EQ, Rinne ML, et al. Individualized screening trial of innovative glioblastoma therapy (INSIGhT): a Bayesian adaptive platform trial to develop precision medicines for patients with glioblastoma. JCO Precis Oncol 2019;3:PO.18.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wick W, Dettmer S, Berberich A, Kessler T, Karapanagiotou-Schenkel I, Wick A, et al. N2M2 (NOA-20) phase I/II trial of molecularly matched targeted therapies plus radiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed non-MGMT hypermethylated glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan AC, Bagley SJ, Wen PY, Lim M, Platten M, Colman H, et al. Systematic review of combinations of targeted or immunotherapy in advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9:e002459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cihoric N, Tsikkinis A, Minniti G, Lagerwaard FJ, Herrlinger U, Mathier E, et al. Current status and perspectives of interventional clinical trials for glioblastoma - analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov. Radiat Oncol 2017;12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin NU, Prowell T, Tan AR, Kozak M, Rosen O, Amiri-Kordestani L, et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology-friends of cancer research brain metastases working group. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3760–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, Ison G, Lin NU, Gore L, et al. Broadening eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative: american society of clinical oncology and friends of cancer research joint research statement. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3737–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim ES, Uldrick TS, Schenkel C, Bruinooge SS, Harvey RD, Magnuson A, et al. Continuing to broaden eligibility criteria to make clinical trials more representative and inclusive: ASCO–friends of cancer research joint research statement. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:2394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perry JR, Laperriere N, O’Callaghan CJ, Brandes AA, Menten J, Phillips C, et al. Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1027–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Groot JF, Fuller G, Kumar AJ, Piao Y, Eterovic K, Ji Y, et al. Tumor invasion after treatment of glioblastoma with bevacizumab: radiographic and pathologic correlation in humans and mice. Neuro Oncol 2010;12: 233–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quant EC, Norden AD, Drappatz J, Muzikansky A, Doherty L, Lafrankie D, et al. Role of a second chemotherapy in recurrent malignant glioma patients who progress on bevacizumab. Neuro Oncol 2009;11:550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner A, Read W, Steinberg D, Lhermitte B, et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:2306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burri SH, Gondi V, Brown PD, Mehta MP. The evolving role of tumor treating fields in managing glioblastoma: guide for oncologists. Am J Clin Oncol 2018;41: 191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grayling MJ, Dimairo M, Mander AP, Jaki TF. A review of perspectives on the use of randomization in phase II oncology trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111: 1255–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131:803–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brat DJ, Aldape K, Colman H, Holland EC, Louis DN, Jenkins RB, et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 3: recommended diagnostic criteria for “diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV. Acta Neuropathol 2018;136:805–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phase II trials in the EORTC. The protocol review committee, the data center, the research and treatment division, and the new drug development office. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer 1997;33:1361–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grossman SA, Ye X, Piantadosi S, Desideri S, Nabors LB, Rosenfeld M, et al. Survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with radiation and temozolomide in research studies in the United States. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:2443–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang H, Foster NR, Grothey A, Ansell SM, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ. Comparison of error rates in single-arm versus randomized phase II cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1936–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanderbeek AM, Ventz S, Rahman R, Fell G, Cloughesy TF, Wen PY, et al. To randomize, or not to randomize, that is the question: using data from prior clinical trials to guide future designs. Neuro Oncol 2019;21:1239–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sampson JH, Heimberger AB, Archer GE, Aldape KD, Friedman AH, Friedman HS, et al. Immunologic escape after prolonged progression-free survival with epidermal growth factor receptor variant III peptide vaccination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2010;28: 4722–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sampson JH, Aldape KD, Archer GE, Coan A, Desjardins A, Friedman AH, et al. Greater chemotherapy-induced lymphopenia enhances tumor-specific immune responses that eliminate EGFRvIII-expressing tumor cells in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2011;13:324–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schuster J, Lai RK, Recht LD, Reardon DA, Paleologos NA, Groves MD, et al. A phase II, multicenter trial of rindopepimut (CDX-110) in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: the ACT III study. Neuro Oncol 2015; 17:854–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terasaki M, Shibui S, Narita Y, Fujimaki T, Aoki T, Kajiwara K, et al. Phase I trial of a personalized peptide vaccine for patients positive for human leukocyte antigen–A24 with recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reardon DA, Lassman AB, van den Bent M, Kumthekar P, Merrell R, Scott AM, et al. Efficacy and safety results of ABT-414 in combination with radiation and temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:965–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lassman AB, van den Bent MJ, Gan HK, Reardon DA, Kumthekar P, Butowski N, et al. Safety and efficacy of depatuxizumab mafodotin + temozolomide in patients with EGFR-amplified, recurrent glioblastoma: results from an international phase I multicenter trial. Neuro Oncol 2019; 21:106–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gan HK, Reardon DA, Lassman AB, Merrell R, van den Bent M, Butowski N, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor response of depatuxizumab mafodotin as monotherapy or in combination with temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;20:838–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Omuro A, Vlahovic G, Lim M, Sahebjam S, Baehring J, Cloughesy T, et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: results from exploratory phase I cohorts of CheckMate 143. Neuro Oncol 2018; 20:674–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cloughesy TF, Landolfi J, Hogan DJ, Bloomfield S, Carter B, Chen CC, et al. Phase 1 trial of vocimagene amiretrorepvec and 5-fluorocytosine for recurrent high-grade glioma. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:341ra75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cloughesy TF, Landolfi J, Vogelbaum MA, Ostertag D, Elder JB, Bloomfield S, et al. Durable complete responses in some recurrent high-grade glioma patients treated with Toca 511 + Toca FC. Neuro Oncol 2018;20: 1383–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bota DA, Desjardins A, Mason WP, Fine HA, Reich SD, Trikha M. Phase 1, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation, study of marizomib (MRZ) and bevacizumab (BEV) in WHO grade IV malignant glioma (G4 MG). J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2037.27114592 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taal W, Oosterkamp HM, Walenkamp AM, Dubbink HJ, Beerepoot LV, Hanse MC, et al. Single-agent bevacizumab or lomustine versus a combination of bevacizumab plus lomustine in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (BELOB trial): a randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:943–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herrlinger U, Tzaridis T, Mack F, Steinbach JP, Schlegel U, Sabel M, et al. Lomustine-temozolomide combination therapy versus standard temozolomide therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CeTeG/NOA-09): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393:678–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Glas M, Happold C, Rieger J, Wiewrodt D, Bähr O, Steinbach JP, et al. Long-term survival of patients with glioblastoma treated with radiotherapy and lomustine plus temozolomide. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 1257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arevalo OD, Soto C, Rabiei P, Kamali A, Ballester LY, Esquenazi Y, et al. Assessment of glioblastoma response in the era of bevacizumab: longstanding and emergent challenges in the imaging evaluation of pseudoresponse. Front Neurol 2019;10:460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weller M, Le Rhun E. How did lomustine become standard of care in recurrent glioblastoma? Cancer Treat Rev 2020;87:102029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ventz S, Lai A, Cloughesy TF, Wen PY, Trippa L, Alexander BM. Design and evaluation of an external control arm using prior clinical trials and real-world data. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4993–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertagnolli MM, Blanke CD, Curran WJ, Hawkins DS, Mannel RS, O’Dwyer PJ, et al. What happened to the US cancer cooperative groups? A status update ten years after the Institute of Medicine report. Cancer 2020;126:5022–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]