ABSTRACT

Arthrobotrys oligospora (A. oligospora) is a typical nematode-trapping (NT) fungus that can capture nematodes by producing adhesive networks. Peroxisomes are single membrane-bound organelles that perform multiple physiological functions in filamentous fungi. Peroxisome biogenesis proteins are encoded by PEX genes, and the functions of PEX genes in A. oligospora and other NT fungi remain largely unknown. Here, our results demonstrated that two PEX genes (AoPEX1 and AoPEX6) are essential for mycelial growth, conidiation, fatty acid utilization, stress tolerance, and pathogenicity in A. oligospora. AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 knockout resulted in a failure to produce traps, conidia, peroxisomes, and Woronin bodies and damaged cell walls, reduced autophagosome levels, and increased lipid droplet size. Transcriptome data analysis showed that AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 deletion resulted in the upregulation of the proteasome, membranes, ribosomes, DNA replication, and cell cycle functions, and the downregulation of MAPK signaling and nitrogen metabolism. In summary, our results provide novel insights into the functions of PEX genes in the growth, development, and pathogenicity of A. oligospora and contribute to the elucidation of the regulatory mechanism of peroxisomes in trap formation and lifestyle switching in NT fungi.

IMPORTANCE Nematode-trapping (NT) fungi are important resources for the biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes. They are widely distributed in various ecological environments and capture nematodes by producing unique predatory organs (traps). However, the molecular mechanisms of trap formation and lifestyle switching in NT fungi are still unclear. Here, we provided experimental evidence that the AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes could regulate mycelial growth and development, trap formation, and nematode predation of A. oligospora. We further analyzed the global transcription level changes of wild-type and mutant strains using RNA-seq. This study highlights the important role of peroxisome biogenesis genes in vegetative growth, conidiation, trap formation, and pathogenicity, which contribute to probing the mechanism of organelle development and trap formation of NT fungi and lays a foundation for developing high-efficiency nematode biocontrol agents.

KEYWORDS: Arthrobotrys oligospora, peroxisome biogenesis-genes, conidiation, fatty acid utilization, trap formation, transcriptome analysis

INTRODUCTION

Peroxisomes are conserved organelles in almost all eukaryotic cells that are rich in enzymes that participate in various biochemical metabolic processes, such as fatty acid β-oxidation, glyoxylate detoxification, cholesterol synthesis, regulation of reactive oxygen species, assimilation of methanol in yeast, and biosynthesis of plasmalogen in mammals (1–3). In eukaryotes, peroxisomes are involved in various biochemical processes; for example, in yeast, the peroxisome is the only site for fatty acid β-oxidation, which is critical for cellular maintenance of fatty acid homeostasis (4, 5). In plants, peroxisomes are involved in embryonic development, photorespiration, host resistance, nitrogen and sulfur compound metabolism, plant hormone synthesis, and the glyoxylate cycle (6–9). Peroxisomes also play vital roles in filamentous fungi, as various fungal metabolites are partially synthesized within them. Peroxisome-deficient fungi fail to grow in minimal medium containing fatty acids as the sole carbon source and exhibit delayed growth and aberrant organelle morphologies (10–12).

Recent advances have resulted in the identification of over 30 PEX genes, which are essential factors for peroxisome biogenesis in various species from yeast to humans (13); these have been found to be involved in matrix protein import, membrane biogenesis, and organelle proliferation (3). Both PEX1 and PEX6 encode an AAA-type ATPase and are involved in importing peroxisomal matrix proteins by mediating the recycling of peroxisomal membrane targeting signals (PTS) receptors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Kimura et al. first reported that the PEX6 gene is necessary for Colletotrichum lagenarium-mediated infection and reduces fatty acid utilization. In addition, the same authors reported that PST1-mediated matrix protein transport could not be performed normally in the PEX6 mutant strain, indicating the involvement of peroxisomal metabolism in the pathogenicity of plant fungal pathogens (14). In Magnaporthe oryzae, PEX1 is involved in regulating growth and sporulation ability, appressorium morphology, pathogenicity, and other biological processes (15, 16). Moreover, some other PEX genes have been identified to be involved in many functions. For example, loss of the PEX19 gene affects the transport process of matrix and membrane proteins, resulting in a complete loss of pathogenicity (17). Knockout of the PEX14/17 gene was shown to reduce fat utilization ability, reactive oxygen resistance, and pathogenicity (18). Taken together, PEX genes participate in the regulation of various biological processes in filamentous fungi, including pathogenicity, mycelial growth, and fat utilization, sporulation, and reactive oxygen degradation capacities.

Nematode-trapping (NT) fungi are broadly distributed in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. They can trap and digest nematodes using specialized trapping devices (traps), such as adhesive networks and knobs and constricting rings. The development of these traps is a key indicator of their switch from saprophytic to predacious lifestyles (19–21). Arthrobotrys oligospora is a representative species of NT fungi that produces adhesive networks to capture nematodes (21). To date, the whole-genome sequence of A. oligospora has been reported and annotated, and the trap formation pathway has also been proposed through proteomics analysis (21). The ultrastructure of A. oligospora has been observed through transmission electron microscopy, revealing that the structure of trap cells significantly differs from that of vegetative hyphae cells. There are many ultrastructural bodies in the hyphal cells of traps, known as electron-dense (ED) bodies (22). Since these EDs have catalase and d-amino acid oxidase activities, they may belong to peroxisomes based on their biochemical properties (23). In addition, Woronin bodies, organelles derived from peroxisomes, play an important role in various biological processes such as conidia development, infective structure formation, stress resistance, and adaptation to nutrient-deficient environments (24). In summary, peroxisomes are closely related to trap formation. However, the role of peroxisomes in trap formation in NT fungi remains largely unknown.

To investigate the biological functions and regulatory mechanisms of peroxisomes in NT fungi, we characterized A. oligospora PEX1 and PEX6 homologs (AoPEX1 and AoPEX6, respectively) through gene knockout, and related phenotypic experiments were used to infer the roles of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 in mycelial development and nematode predation. Moreover, transcriptome technology was used to analyze global changes in gene transcription levels between the wild-type (WT) strain and mutants, laying a foundation for further clarifying the regulatory mechanism of peroxisomal proteins in NT fungi trap formation.

RESULTS

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of AoPex1 and AoPex6.

Analysis using the Compute pI/Mw tool of the ExPASy database revealed that AoPEX1 encodes a protein with 1,194 amino acid residues, a theoretical molecular mass of 127.88 kDa, and pI of 4.74, while AoPEX6 encodes a protein containing 1,183 amino acids residue, a molecular mass of 126.95 kDa, and pI of 8.45. The functional domains of the two proteins were analyzed using the InterProScan database; both AoPex1 and AoPex6 contain an ATPase AAA core domain (IPR003959) and an AAA-type ATPase domain (IPR003593), as well as an ATPase AAA CS function site (IPR003960). Unexpectedly, AoPex1 has an extra PEX1-N psi beta-barrel domain (IPR015432) and an AAA lid 3 domain (IPR041569), unlike AoPex6. Furthermore, AoPex1 is highly similar to the orthologs of three other NT fungal species, Arthrobotrys flagrans (97.1%), Dactylellina haptotyla (88.5%), and Drechslerella brochopaga (84.9%). In contrast, it shares moderate similarity (41.1–46.1%) with orthologs from other filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus nidulans, M. oryzae, and Neurospora crass. Similarly, the AoPex6 sequence is identical to those of orthologs found in the NT fungi A. flagrans (97.2%), D. haptotyla (94.4%), and D. brochopaga (90.6%) and less so compared with other filamentous fungi (55.4–57.7%) or Saccharomyces cerevisiae (9.4%). Moreover, a phylogenetic tree of orthologous Pex proteins from various fungi was constructed. As expected, Pex1 or Pex6 orthologs from NT fungi clustered into two independent branches (Fig. S1 in the online supplementary material).

AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 regulate mycelial growth and the number of cell nuclei.

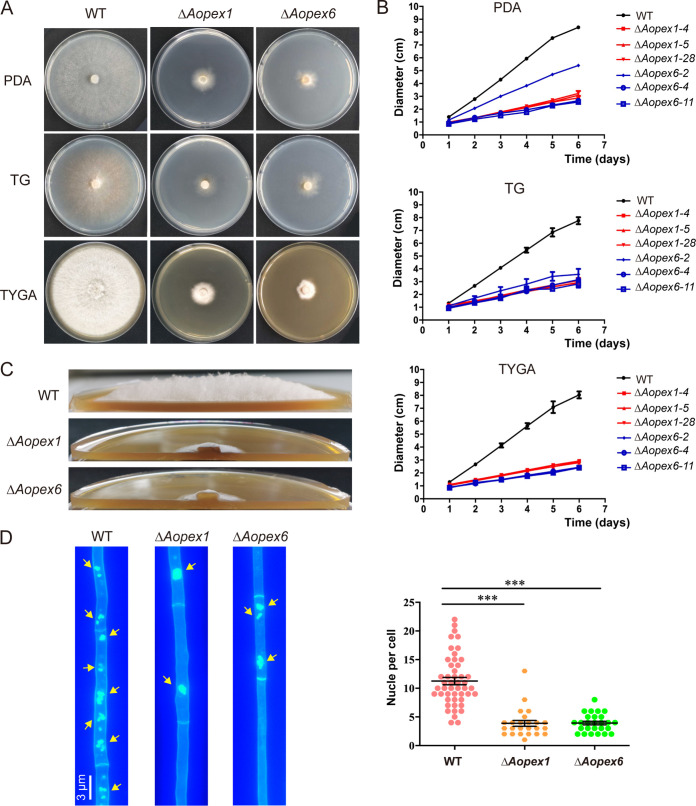

The AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes were disrupted as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. S2 in the online supplementary material), and three mutants of each gene were randomly selected for subsequent analysis. The hyphae of the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains showed obvious growth defects compared with those of the WT strains (Fig. 1A), and their colony diameters were reduced by 65 and 62.5%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, using a side-shot approach for the aerial hyphae, we observed that the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants displayed sparse aerial hyphae, whereas the WT strain showed dense aerial hyphae following culturing on TYGA medium (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the number of nuclei in hyphal cells from the ΔAopex1 mutant (3–4 nuclei per cell) and ΔAopex6 mutant (4–5 nuclei per cell) was less than that in the WT strain (11–13 nuclei per cell) (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Comparison of hyphal growth of wild-type (WT) and mutant strains in A. oligospora. (A) Colonial shapes of fungal strains cultured on PDA, TG, and TYGA plates at 28°C. The strains were photographed after 6 days of incubation. (B) The quantification data for (A). (C) Aerial hyphae of the WT and mutant strains cultured on TYGA medium for 5 d. (D) Hyphae of the WT and each mutant strain were stained with CFW and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) after the fungal strains were grown for 7 days on CMY medium. One hundred hyphal cells were randomly selected for counting cell nuclei. Bar: 3 μm. Measurements represent the average of three independent experiments. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between the mutant and the WT strains (***P < 0.001).

Absence of the AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes eliminated conidiation, trap formation, and pathogenicity.

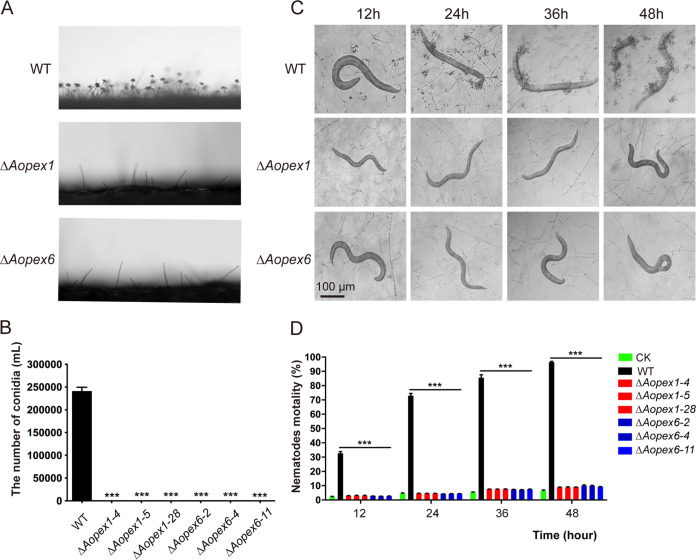

Compared with the WT strain, the number and density of conidiophores in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains were remarkably decreased, and neither mutant could produce conidia on the conidiophore (Fig. 2A–B), indicating that the mutants lost the ability to produce conidia. Transcriptome data analysis revealed the increased downregulation of sporulation-related genes in mutant strains compared with the WT strain (Fig. S3 in the online supplementary material). Trap formation was induced by adding nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans) to the WA plates. Results showed several traps on the plates containing the WT strain, but none were observed on the plates containing ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 after adding nematodes for 12, 24, 36, and 48 h (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the nematode mortality rate was remarkably decreased in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 relative to WT (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results indicate that deleting AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes led to complete elimination of sporulation and trap formation and a remarkable decrease in the ability to trap nematodes in A. oligospora.

FIG 2.

Comparison of sporulation, trap formation, and nematocidal activity in the wild-type (WT) and mutant strains. (A) Conidiophore differentiation in the WT and mutant lines. (B) Spore yields of the WT and mutant lines. (C) Trap formation in the WT and mutant lines induced by nematodes at different time points. Bar: 100 μm. (D) The percentage of nematode mortality by the WT and mutant lines at different time points. CK is the negative control using WA plate to assess the viability of the C. elegans in the absence of fungal strains. The asterisk (B and D) indicates a significant difference between the mutant and the WT strains (***P < 0.001).

AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 are critical to stress response.

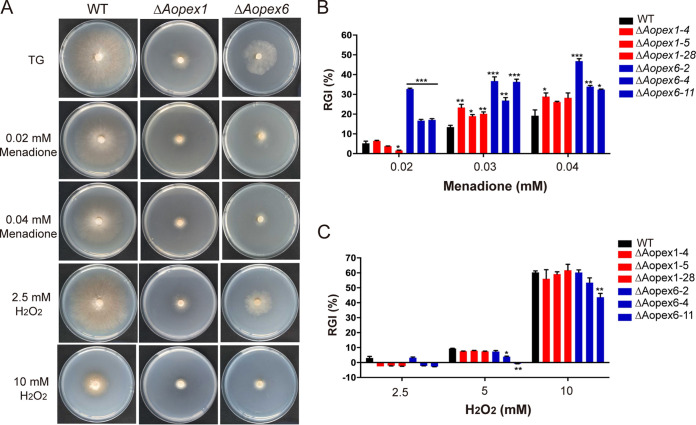

To investigate the role of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 under different chemical stress conditions, the mycelial growth of the WT and mutant strains was analyzed by comparing the relative growth inhibition (RGI) values on TG medium supplemented with various chemical agents. In osmotic sensitivity tests, ΔAopex1 mutants had reduced RGI values under low concentrations of NaCl and sorbitol stress conditions, while the ΔAopex6 mutant displayed greater sensitivity to 0.1 M NaCl, with considerably lower RGI values compared with WT (Fig. S4A in the online supplementary material). However, when growing on a medium containing 0.75 M sorbitol and 0.3 M NaCl, the sensitivity of the mutant strains was reduced (Fig. S4B and C). Next, we tested the oxidative stress response by adding menadione and H2O2 at different concentrations to the medium (Fig. 3A). The results showed that both ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 were more sensitive to menadione, and their RGI values were substantially increased compared with WT (Fig. 3B). However, the growth of the mutant strains was not inhibited by H2O2 treatment (Fig. 3C).

FIG 3.

Comparison of stress tolerance to oxidative agents between wild-type (WT) and mutant strains of A. oligospora. (A) Colony morphologies of the WT and mutant strains incubated on TG medium supplemented with menadione or H2O2. (B) Relative growth inhibition (RGI) values of the WT and mutants after incubation on TG medium supplemented with 0.02–0.04 mM menadione for 6 days. (C) RGI values for the WT and mutant strains after incubation on TG medium supplemented with 2.5–10 mM H2O2 for 6 days. The asterisk (B and C) indicates a significant difference between the mutant and the WT strains (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

To investigate whether AoPEX1 or AoPEX6 plays a role in cell wall biosynthesis in A. oligospora, we examined how the mutants responded to a range of cell wall stress agents (Fig. S5A in the online supplementary material). The colony diameters of the mutants were remarkably smaller than those of the WT strain when cultured on medium supplemented with 0.05 mg/mL Congo red (CR) (Fig. S5B). There was no significant difference in the RGI values between mutant and WT strains after adding SDS (Fig. S5C). Therefore, deleting AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 results in defective cell wall biosynthesis in A. oligospora.

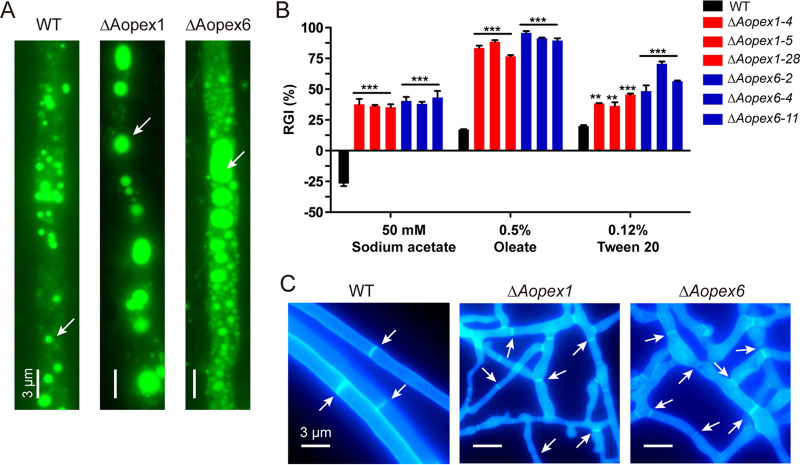

AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 play an important role in fatty acid utilization and hyphal morphology.

Boron dipyrromethene dyes (BODIPY) specifically stain lipid droplets (LDs) composed of neutral lipids (25). Following hyphal staining and imaging, we found that the LD volumes of ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 were significantly enlarged compared with those of WT (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, to clarify the effect of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 on fatty acid utilization, the vegetative growth of the WT and mutant strains on MM medium containing different fatty acids, including sodium acetate, oleate, and Tween 20 as the sole carbon source, was assessed. medium for 6 days, the RGI values of ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants were significantly increased After incubation in fatty acid as the sole carbon, with oleic acid being the most significant. For example, the RGI value of the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants in 0.5% oleate increased by 79 and 81%, respectively, relative to that of the WT strain (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 are required for fatty acid utilization in A. oligospora.

FIG 4.

Comparison of fatty acid utilization and hyphae morphology between wild-type (WT) and mutant strains of A. oligospora. (A) The LDs of WT, ΔAopex1, and ΔAopex6 strains were stained with BODIPY. Bar: 3 μm. (B) RGI values of fungal strains under different fatty acids as the only carbon source. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between the mutant and the WT strains (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (C) The CFW staining of WT and mutant strains. Bar: 3 μm.

Subsequently, hyphae cultured on a CMY plate for 7 days were observed by staining with calcofluor white (CFW) dye. The results showed that ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 hyphae were enlarged and deformed and formed more branches to connect to the network structure compared with the WT strain (Fig. 4C).

AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 regulate autophagy and biogenesis of peroxisomes and Woronin bodies.

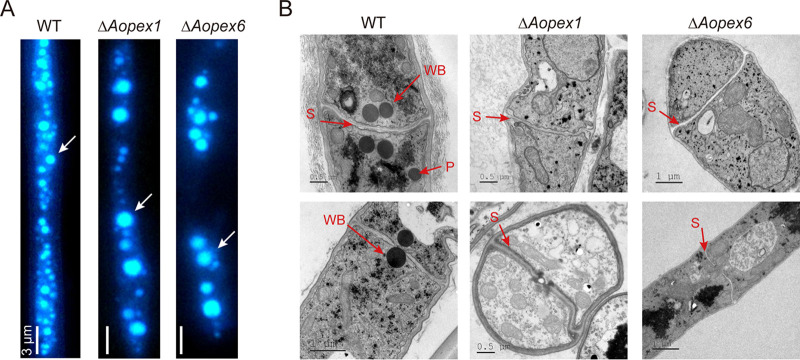

By staining with monodansylcadaverine (MDC) dye, we found that the number of autophagosomes in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants was decreased, but the volume of autophagosomes remarkably increased (Fig. 5A). In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results showed that the WT strain had Woronin bodies near the hyphal septum, and peroxisomes could be observed in the hyphae. However, Woronin bodies and peroxisomes were not observed in the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 strains (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Observation of autophagosomes and ultrastructure of peroxisomes and Woronin bodies in the wild-type (WT) and mutant strains. (A) The autophagosomes of WT strain, ΔAopex1, and ΔAopex6 mutant strains were stained with MDC. Bar: 3 μm. (B) The WT and mutant strains were observed by transmission electron microscopy. WB: Woronin body; P: peroxisome; S: septum.

Transcriptomic profile analysis of the WT and mutant strains.

To further explore the regulatory mechanisms of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 in A. oligospora, we compared the transcriptomic profiles of the WT and mutant strains using RNA-seq technology. The mycelial samples of WT and mutant strains were collected and cultured in PD broth for 3 and 5 days, respectively, after which a cDNA library was constructed and sequenced for each sample. As a result, 41.6–53.7 million reads were obtained for each sample (Table S1 in the online supplemental material). The percentage of Phred-like quality scores at the Q30 level ranged from 92.5 to 94.0%, and the GC content ranged from 47.4 to 48.4% (Table S2). Principal-component analysis showed that the WT and mutant strains were located in different quadrants at various time points, indicating that their transcription profiles significantly differed and higher similarity appeared in the three replicates of the samples (Fig. S6). Meanwhile, 15 genes associated with the nitrogen compound metabolic process, nitrogen metabolism, and MAPK signaling were selected to verify the transcriptomic data by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Table S3). The transcriptome showed downregulation of nitrogen compound metabolic processes, nitrogen metabolism, and MAPK signaling-related gene levels. In addition, RT-qPCR verified that mRNA levels were also downregulated at 3 and 5 days—for WT and mutant strains, respectively—indicating a relatively high consistency between the RNA-seq and RT-qPCR analyses (Fig. S7).

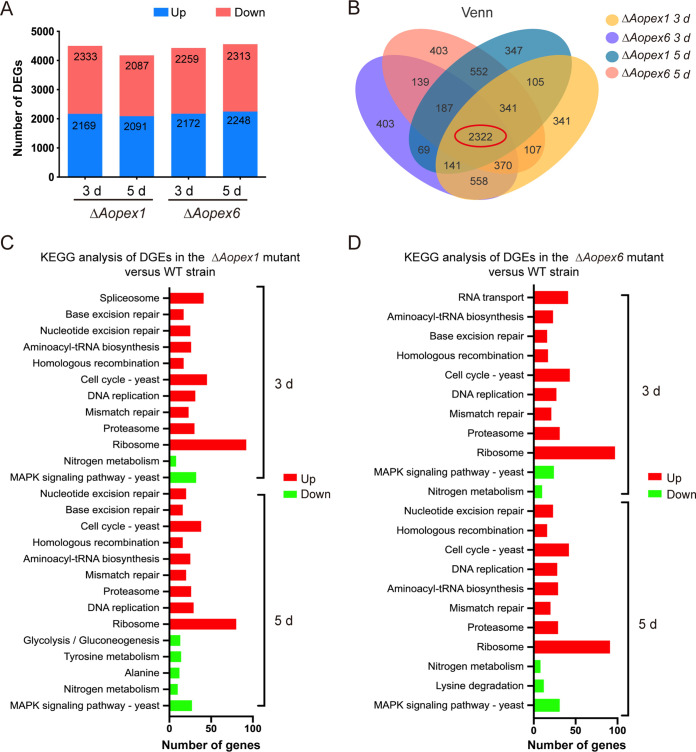

The ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 strains were found to have 4,496 and 4,178 and 4,431 and 4,560 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) at 3 and 5 days, respectively (Fig. 6A). Between the WT and mutant strains, there were 4285 and 4064 and 4421 and 4189 co-expressed genes at 3 and 5 d, respectively (Fig. S8 in the online supplemental material). Afterward, 2,322 contigs shared between the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants were found at all time points through Venn analysis (Fig. 6B). Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed to analyze the functional categories of these DEGs. On the 3rd day, the most enriched GO terms in the ΔAopex1 strain were associated with molecular functions (MF), including aminoacyl-tRNA ligase activity and ligase activity; seven cellular components (CC), such as proteasome storage granule, endopeptidase complex, proteasome complex, and protein folding; and 11 biological processes (BP) such as tRNA aminoacylation for protein translation, protein catabolic process, and DNA replication. The most downregulated processes were transcriptional regulatory activity, nitrogen metabolism, and primary metabolism. On the 5th day, the upregulated GO terms included the cell cycle, cytoplasmic part, and ribosomal subunits, while the downregulated GO term was RNA metabolism (Fig. S9A). In addition, the significantly upregulated and downregulated GO terms were very similar between the ΔAopex6 and ΔAopex1 strains at 3 and 5 days (Fig. S9B).

FIG 6.

Transcription analysis in wild-type (WT), ΔAopex1, and ΔAopex6 mutant strains. (A) DEGs on the 3rd and 5th days. Red, upregulated DEGs; green, downregulated DEGs. (B) Venn analysis of WT, ΔAopex1, and ΔAopex6 mutant strains at two time points. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in WT and ΔAopex1 strains. (D) KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs in WT and ΔAopex6 strains. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Furthermore, pathway enrichment in the WT and ΔAopex1/ΔAopex6 strains was compared and analyzed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis. Compared with the WT, there were 10 and 9 significantly upregulated pathways and 2 and 5 downregulated pathways in the ΔAopex1 mutant at 3 and 5 days, respectively. However, the ΔAopex6 mutant had 10 and 8 significantly upregulated pathways and 2 and 3 significantly downregulated pathways. On the thirrd day, the same significantly upregulated pathways, including cell cycle-yeast, ribosome, and proteasome, were enriched in both ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants. In addition, the KEGG enrichment of DEGs on the third and fifth days was very similar, and the difference was that glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and tyrosine metabolism were additionally enriched in the ΔAopex1 mutant, and lysine degradation was additionally enriched in the ΔAopex6 mutant (Fig. 6C and D).

Based on GO and KEGG analyses, we analyzed the expression of several genes related to catalase expression. The results showed that most genes related to the oxidative stress response were altered in mutants compared with those in the WT at 3 and 5 days, including cat (AOL_s00188g243), cat-2 (AOL_s00006g411 and AOL_s00076g488), nox-1 (AOL_s00193g69), nox-2 (AOL_s00007g557), noxR (AOL_s00054g538), and sod-2 (AOL_s00170g93). The expression levels of nox-2, noxR, and sod-2 were considerably downregulated in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants at 3 and 5 days, whereas that of cat was upregulated (Table 1). In addition, we also analyzed the expression of genes related to cell wall biosynthesis, and the results showed that except for hex (AOL_s00112g89), other genes were significantly altered in the mutants at 3 and 5 days, including glu (AOL_s00083g375), chs-3 (AOL_s00078g76), chs (AOL_s00075g119), trs (AOL_s00097g268), and gls (AOL_s00054g491). Furthermore, chs, chs-3, trs, and gls transcripts were conspicuously downregulated in the mutants, whereas that of glu was considerably upregulated in the mutants (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Transcriptional response to Aopex1 and Aopex6 deletion by the genes involved in oxidation stress response and cell wall biosynthesis in comparative transcriptome analysisa

| Locus | Function annotation | Expressional levels |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM-3 d |

TPM-5 d |

||||||

| WT | ΔAopex1 | ΔAopex6 | WT | ΔAopex1 | ΔAopex6 | ||

| Genes involved in oxidation stress response | |||||||

| AOL_s00173g374 | cat, catalase | 114.08 | 108.57 | 157.15 | 221.52 | 271.79 | 207.81 |

| AOL_s00188g243 | cat, catalase | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.37 | 0.06 |

| AOL_s00006g411 | cat2, catalase | 362.47 | 182.99 | 337.40 | 112.35 | 241.7 | 272.67 |

| AOL_s00076g488 | cat2, catalase | 2.42 | 2.06 | 1.09 | 4.85 | 11.82 | 3.82 |

| AOL_s00193g69 | nox-1, NADPH oxidase | 116.94 | 55.24 | 54.31 | 112.35 | 119.31 | 87.49 |

| AOL_s00007g557 | nox-2, NADPH oxidase | 150.80 | 26.48 | 29.05 | 119.68 | 26.63 | 37.86 |

| AOL_s00054g538 | noxR, NADPH oxidase regulator | 8.83 | 4.17 | 4.52 | 9.19 | 6.85 | 3.00 |

| AOL_s00007g292 | sod, superoxide dismutase | 57.92 | 46.19 | 50.59 | 31.22 | 50.78 | 55.37 |

| AOL_s00054g687 | sodB, superoxide dismutase | 327.69 | 278.85 | 267.48 | 302.02 | 432.79 | 344.10 |

| AOL_s00170g93 | sod-2, superoxide dismutase | 19.72 | 2.21 | 4.63 | 20.50 | 11.63 | 4.52 |

| Genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis | |||||||

| AOL_s00078g76 | chs-3, chitin synthases | 179.05 | 41.50 | 57.1 | 274.17 | 76.86 | 44.69 |

| AOL_s00112g89 | hex, hexokinase | 673.25 | 324.68 | 331.42 | 249.00 | 175.31 | 251.03 |

| AOL_s00075g119 | chi, chitin synthase | 122.65 | 36.49 | 45.59 | 217.50 | 39.69 | 20.01 |

| AOL_s00097g268 | trs, trehalose synthase | 375.64 | 68.82 | 73.41 | 401.90 | 47.43 | 64.96 |

| AOL_s00083g375 | glu, beta-glucosidase | 3.54 | 15.63 | 12.96 | 3.63 | 10.13 | 8.76 |

| AOL_s00054g491 | gls, 1,3-beta-glucan synthase | 363.28 | 75.11 | 127.99 | 657.36 | 140.19 | 113.51 |

TPM, transcripts per kilobase million. WT, wild-type strain; ΔAopex1, Aopex1 deletion mutant; ΔAopex6, Aopex6 deletion mutant; -3 d and -5 d, samples of the WT, ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains in vegetative growth stage. Locus numbers and function were annotated according to the A. oligospora genome assembly (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Cluster analysis of transcriptome.

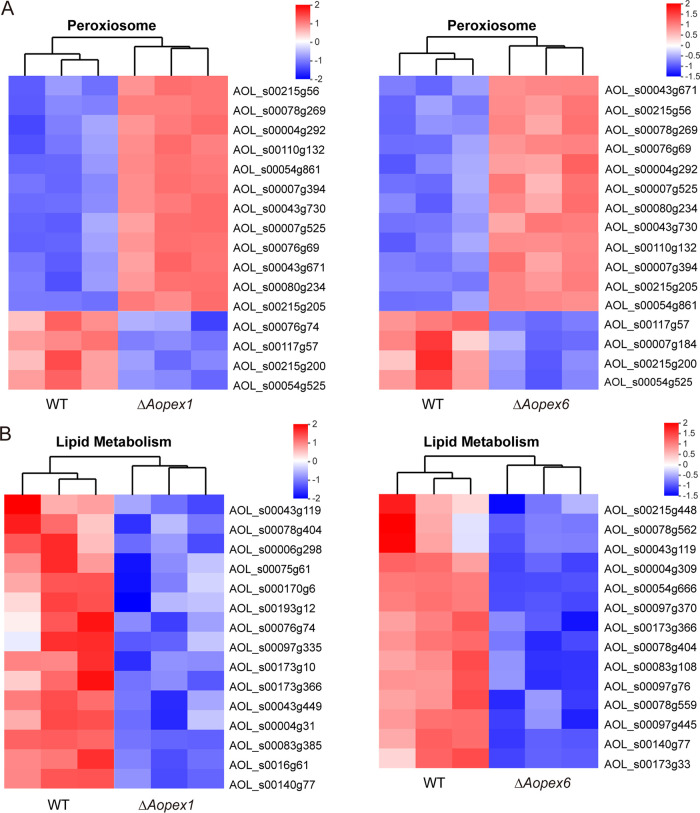

Based on GO and KEGG analyses, we performed a cluster analysis of genes related to peroxisome and lipid metabolism. The results showed that the up- and downregulated genes enriched in the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants were highly similar (Fig. 7A). Among the upregulated genes related to peroxisomes in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants, five genes were involved in peroxisome biosynthesis [Pex4 (AOL_s00078g269), Pex5 (AOL_s00043g671), Pex10 (AOL_s00054g861), Pex14 (AOL_s00004g292), and peroxisomal membrane protein Pmp47 (AOL_s00215g205)], three genes were involved in lipid fatty acid degradation [enoyl-CoA hydratase (AOL_s00215g56 and AOL_s00043g730) and long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (AOL_s00007g525)], and two genes (AOL_s00110g132 and AOL_s00076g69) were related to the oxidative stress response. Three genes associated with peroxisomes were downregulated in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants, including sarcosine oxidase (AOL_s00117g57), long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (AOL_s00215g200), and Pex13 (AOL_s00054g525) (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, the lipid metabolism-related genes were all less expressed in the mutant strains than in the WT strain. The ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants shared four common genes, including AOL_s00043g119, AOL_s00078g404, AOL_s00173g366, and AOL_s00140g77 (Fig. 7B). Moreover, except for one gene (AOL_s00140g79) in ΔAopex6, the other five genes involved in autophagy appeared in ΔAopex1, and the expression levels of these genes in the mutant strains were lower than those in the WT (Fig. S10 in the online supplemental material).

FIG 7.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with peroxisome and lipid metabolism. (A) Heat map showing the DEGs involved in peroxisomes. (B) Heat map showing the DEGs involved in lipid metabolism. Gene expression patterns are in log10-scale. Red boxes, upregulated clusters; blue boxes, downregulated clusters.

DISCUSSION

Peroxisomal biogenesis has been shown to be related to the pathogenicity of plant pathogenic fungi, such as C. lagenarium (14, 16, 26), Fusarium graminearum (14, 16, 26) and M. oryzae (14, 16, 26). There are 12 peroxin genes, including PEX1-3, PEX5, PEX6, PEX10, PEX12-14, PEX16, PEX19, and PEX26, which are all involved in the protein import machinery (27). Among them, Pex1 and Pex6, members of a large family of ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities, are the only proteins with ATP binding/hydrolysis domains involved in introducing peroxisome matrix proteins (28). In the present study, we identified PEX1 and PEX6 orthologs in A. oligospora (AoPEX1 and AoPEX6, respectively), and phenotypic experiments showed that both orthologs played important roles in mycelial growth and development, stress response, and nematode predation and were essential for conidiation, trap formation, fatty acid utilization, and peroxisome and Woronin body biogenesis.

Previous studies have shown that knockout of the PEX genes MoPEX1, MoPEX6, and AaPEX6 inhibited colony growth and spore production in M. oryzae (15, 16, 29) and Alternaria alternata, respectively (30). In the current study, the colony growth of ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains was remarkably smaller than that of the WT, they did not produce aerial hyphae, and their colonies became compact and flat. In addition, CFW staining showed that ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains exhibited hyphae enlargement compared with WT strains, and their hyphae branching became complicated, forming networks. Notably, in A. oligospora, loss of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 leads to complete elimination of sporulation, differing from the marked reduction in conidiation caused by AaPEX6 mutation in A. alternata (30). The eliminated sporulation capacity correlated with transcriptional repression of several sporulation-related genes in the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants (31). In addition, the number of nuclei in each hyphal cell was markedly decreased in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants than that in the WT strain. Taken together, our results revealed that both AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 are essential for A. oligospora mycelial growth and development.

In some plant-pathogenic fungi, loss of peroxisomes impairs pathogen growth because of inefficient utilization of the carbon sources from the host and the fungus itself (32). In M. oryzae, both MoPEX1 and MoPEX6 are involved in pathogenicity. Loss of MoPEX1 or MoPEX6 impaired vegetative growth, conidiation, and appressorium formation, and deletion of MoPEX1 or MoPEX6 resulted in the loss of peroxisomal integrity and failure to infect the plant host (15, 33). In addition, PEX6 mutants lost pathogenicity in several plant-pathogenic fungi, including M. oryzae, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, F. graminearum, and A. alternata due to defects in peroxisome biogenesis (14, 16, 30). Moreover, PEX1 and PEX6 deletion in M. oryzae led to a lack of Woronin bodies (13, 34), which are essential for efficient pathogenesis and survival during nitrogen starvation stress (35). In the present study, both ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants lost peroxisomes and Woronin bodies. Furthermore, AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 knockout prevented trap formation and significantly decreased nematode infection. These findings showed that PEX1 and PEX6 orthologs are required for peroxisome and Woronin body biosynthesis, thus playing an indispensable role in the morphogenesis of infection structures and virulence of pathogenic fungi.

One of the most important functions of peroxisomes is fatty acid β-oxidation. Previous studies have found that deletion of PEX5 and PEX7 genes can also lead to the obstruction of fat utilization in M. oryzae (36). In F. graminearum, the absence of PEX1 led to an increased accumulation of LDs and endogenous reactive oxygen species (37). In the present study, our results showed that the ability of ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains to utilize sodium acetate, Tween 20, and oleic acid was significantly hindered. In addition, BODIPY staining revealed that LD volume in the two mutant strains increased, indicating that AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 knockout may inhibit fatty acid β-oxidation, resulting in larger LDs. Moreover, transcriptome data analysis revealed downregulated lipid metabolism, consistent with the results obtained from the phenotypic experiment. These results indicate that PEX1 and PEX6 affect the utilization of fatty acids in A. oligospora and possibly other fungi.

Peroxisomes contain various enzymes involved in the oxidative stress response, such as catalase, NADPH oxidase, and superoxide dismutase (38). Here, we found that deletion of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 increases RGI values for several chemical stressors, including Congo red, NaCl, sorbitol, and menadione; however, mutant growth was not inhibited by treatment with SDS and H2O2. These phenotypic changes are consistent with the transcription of several genes involved in the oxidative stress response. Furthermore, biosynthesis of the cell wall was considerably downregulated in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants (38). These findings indicate that PEX1 and PEX6 orthologs are essential for stress response in A. oligospora.

Moreover, we observed that AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 are involved in regulating autophagy. Results showed that autophagosome number decreased in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants, whereas autophagosome volume markedly increased. By analyzing AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 transcriptome data, we found that the autophagy-related genes clustered into eight and six DEGs in the ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants, respectively. Interestingly, except for one gene (AOL_s00140g79), the other five genes in ΔAopex6 were shared with ΔAopex1, and their expression levels were downregulated in ΔAoPEX1 and ΔAoPEX6 mutants. Moreover, the deletion of autophagy-related genes has been observed to reduce trap formation in A. oligospora (24, 36). These results suggest that peroxisomes are closely related to autophagosome formation, thus may hinder trap formation in A. oligospora.

Numerous studies have shown that the interaction between fungi and their hosts can be studied using comparative transcriptome analysis (39). In the present study, we identified several DEGs between the WT and ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutant strains using RNA-seq. At the same time, GO and KEGG enrichment of DEGs were very similar between ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants. The upregulated genes were mainly enriched in the ribosome, amino-tRNA biosynthesis, and proteasome, suggesting that protein synthesis is especially active during peroxisome biosynthesis. Furthermore, several DEGs were enriched in the cell cycle, spliceosome, and DNA replication and repair, suggesting that the absence of Aopex1 and Aopex6 may impair cell nucleus development. In fact, our results revealed that the number of cell nuclei was considerably decreased in ΔAopex1 and ΔAopex6 mutants. In addition, many downregulated genes were enriched in MAPK signaling, which is in line with previous reports (40). For example, deletion of G-protein signaling regulators caused a considerable reduction in conidiation and trap formation (41, 42), and disruption of MAPK signaling components, such as Slt2 and Fus3, resulted in trap formation defects in A. oligospora (40, 43, 44). A previous study hypothesized that the remains of organisms that died during mass extinctions are rich in carbon but poor in nitrogen, such that directly capturing nitrogen-rich living organisms would confer predatory fungi a competitive advantage over strictly saprophytic fungi (45). Recently, the nitrate assimilation pathway has been shown to be involved in trap formation by A. oligospora (46). Accordingly, in the present study, several DEGs were enriched in nitrogen metabolism and nitrogen compound metabolic processes. Therefore, our transcriptome analysis provides a good molecular basis for understanding phenotypic differences between WT A. oligospora and mutants.

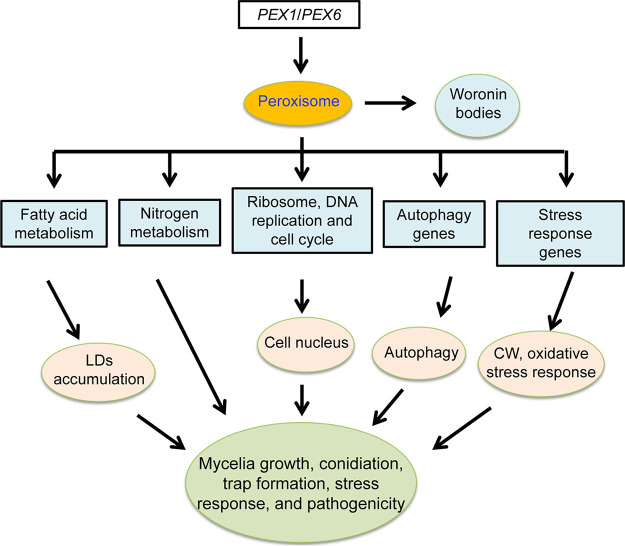

By analyzing the phenotypic traits and RT-qPCR and transcriptional data, we propose a putative regulatory pattern of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 in A. oligospora (Fig. 8). AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 are indispensable for peroxisome and Woronin body biogenesis. The absence of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 hinders nitrogen and fatty acid metabolism, resulting in reduced mycelial growth and enlarged LDs; disrupts ribosomal function, DNA replication, and the cell cycle, causing a reduction in cell nuclei; alters the expression of genes involved in autophagy, oxidative stress, and cell wall biosynthesis, which contributes to the alteration of related cellular processes. Overall, AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 have pleiotropic roles in various cellular processes in A. oligospora, which may have important implications for better understanding the role of PEX genes in the growth, development, and pathogenicity of A. oligospora. Furthermore, this data provides a foundation for unraveling the mechanism of lifestyle switching in NT fungi and exploring their potential application in the biocontrol of pathogenic nematodes.

FIG 8.

Schematic illustration of the regulation of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 in A. oligospora. In A. oligospora, AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 play critical roles in fatty acid metabolism, nutrient metabolism, nucleus formation, autophagy, and oxidative stress processes, thereby regulating hyphal growth, conidiation, and trap formation. CW, cell wall.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The fungus A. oligospora (ATCC24927) and corresponding mutants were stored in the Microbial Library of the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species from Southwest China (Kunming, China). Potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium was prepared for routine culturing of fungal strains at 28°C. Yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) medium was used for culturing S. cerevisiae strain FY834 to construct recombinant plasmid vectors (34). Additionally, TG (10 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L glucose, and 20 g/L agar), TYGA (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L glucose, 5 g/L molasses, and 20 g/L agar), and CMY [20 g/L maizena (corn starch), 5 g/L yeast extract, and 20 g/L agar] media were used to analyze mycelial growth and related phenotypic traits (47). Escherichia coli strain DH5α (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) was used to store the plasmid pCSN44 containing the hygromycin resistance gene (hph), and the plasmid PRS426 was used to construct the knockout vector. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (N2) was maintained on an oatmeal water medium at 26°C.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses of AoPex1 and AoPex6.

Using the orthologs of Pex1 and Pex5 in S. cerevisiae and Aspergillus nidulans as a query, AoPex1 (AOL_s00054g771) and AoPex6 (AOL_s00043g697) were retrieved from A. oligospora. The BLAST algorithm was used to search for Pex1 and Pex6 orthologs in various fungi, and the similarity of the orthologs from different fungi was examined by aligning them using the DNAman software package (version 10.3.307; Lynnon Biosoft, San Ramon, CA, USA) (48) and a neighbor-joining tree was constructed using Mega X software (49).

Knockout of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes.

Taking advantage of the ability of S. cerevisiae FY834 to perform gene self-repair, we used an improved yeast cloning program to construct replacement fragments of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 genes (50, 51). All primers used in this study are listed in Table S4. The upstream and downstream fragments of AoPEX1 and AoPEX6 were PCR amplified from A. oligospora using paired primers, and the hph gene was amplified using the pSCN44 plasmid as a template (52). The three PCR amplicons and pRS426 plasmid backbone (digested with EcoRI and XhoI) were co-transformed into S. cerevisiae FY834 by electroporation and then inoculated on SC-Ura medium to select recombinant cloned strains (Fig. S2A–B) (34, 52). The constructed vectors (pRS426-AoPEX1-hph and pRS426-AoPEX6-hph) were maintained in E. coli DH5α, and the target fragment for gene disruption was amplified using paired primers and transformed into A. oligospora protoplasts as described previously (47, 53). Transformants were selected on PDAS (PDA supplemented with 0.6 mol/L sucrose) medium containing 200 μg/mL hygromycin (54). The putative transformants were confirmed by PCR amplification and Southern blot analyses (Fig. S2C-D). Southern blotting was performed using the North2South Chemiluminescent Hybridization and Detection Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Comparison of mycelial growth, morphology, and conidia yield.

The WT and mutant strains were inoculated on PDA, TYGA, and TG media, and their growth rates and colony morphologies were observed after culturing at 28°C. The experiment was repeated thrice for each strain (43, 50). To observe the septum in mycelia, fresh hyphae were stained with 20 μg/mL CFW (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as described previously (40). The mycelial cell nuclei were visualized by staining with 20 μg/mL DAPI and 20 μg/mL CFW, as previously described (55). The WT and mutant strains cultured on PDA for 7 days were inoculated on PD (200 g/L potatoes, 20 g/L glucose) broth and placed on a shaker at 180 rpm for 3 days. The mycelia were harvested, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and observed by TEM. The WT and mutant strains were cultured in CMY medium for 14 days at 28°C. Mycelia were scraped using inoculation loops, and 5 mL of sterile water was added and shaken to obtain the conidia suspension (50 μL). The conidial numbers in the suspensions were counted using a hemocytometer with conidia per cm2 of plate culture as an estimate of conidial yield (56).

Analysis of stress tolerance.

The mycelial plugs of each strain were inoculated onto TG media supplemented with different concentrations of chemical stressors at 28°C for 6 days. The chemical reagents used to determine the stress tolerance of fungal strains were as follows: sorbitol (0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 M) and NaCl (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 M) as osmotic stressors; sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (0.01, 0.02, and 0.03%) and Congo red (0.05, 0.07, and 0.1 mg/mL) as cell wall stress agents, and menadione (0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 mM) and H2O2 (2.5, 5, and 10 mM), and oxidative stressors. The diameter of each colony was measured, and the relative growth inhibition (RGI) of each colony was calculated as described previously (47). These experiments were performed at least thrice.

Trap formation and pathogenicity assays.

WT and mutant strains were incubated on WA (20 g/L agar) plates at 28°C for 3–4 days, and then approximately 300 nematodes (C. elegans) were added to each WA plate to induce trap formation. The number of traps and captured nematodes were observed and quantified using a light microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at specific time points.

Analysis of LDs and fatty acid utilization.

The WT and mutant strains were cultured on TYGA for 5 days and then stained with 15–20 μL of 10 μg/mL BODIPY staining solution for 30 min. Changes in the size and shape of the lipid droplets were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany). In addition, the WT and mutant strains were treated with MM (2 g/L NaNO3, 0.01 g/L FeSO4·7H2O, 20 g/L glucose, and 20 g/L agar) medium without a carbon source as the basic medium, after adding 50 mM sodium acetate, 0.12% oleic acid, and 0.5% Tween 20 as the only carbon source for culturing for 6 days. The RGI value was calculated by measuring colony diameter as previously described (53, 57).

Detection of autophagy.

To analyze the changes in the autophagic process in WT and mutant strains, we cultured the strains on TYGA plates with sterile coverslips for 5 days. Subsequently, the stains were treated with 30–50 μL of 100 mg/mL MDC staining solution at 37°C in the dark for 30–40 min, and the images were observed and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Leica, Mannheim, Germany).

RT-qPCR analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen fungal tissues using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cDNA was reverse transcribed using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR experiments were performed as described previously (42). Relative transcription levels were determined using the 2- ΔΔCT method with the β-tubulin (AOL_s00076g640) gene as the reference (58). All primers used for the RT-qPCR assays are listed in Table S3 in the online supplemental material. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated thrice.

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis.

The WT and mutant strains were cultured in PDA medium at 28°C for 3 and 5 days, respectively. Three treatment groups with three independent biological replicates were used for each sample. Sequencing of mycelial samples was performed by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the data were analyzed using the Majorbio Cloud Platform (www.majorbio.com). Subsequently, RT-qPCR was used to verify the transcriptome data (59). The genes and their primers used are listed in Table S3 in the online supplemental material. The transcripts per kilobase million method was used to calculate the expression level of each transcript to identify DEGs (60). Functional enrichment analysis identified the DEGs significantly enriched in the GO terms (P ≤ 0.05) through GO and KEGG analyses (61).

Statistical analysis.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to differentiate the observations, measurements, and estimates. Data are presented as means±standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism version 9.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the photographs and statistical analyses from triplicate experiments, and P < 0.05 was used as the threshold for determining significant differences.

Data availability.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published paper and the associated supplemental files. The raw sequence has been deposited to GEO under accession number GSE193953.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Guo Yingqi (Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for her help in obtaining and analyzing the TEM images.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 30960229 and 31960556) and the Applied Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province (202001BB050004).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Jinkui Yang, Email: jinkui960@ynu.edu.cn.

Giuseppe Ianiri, University of Molise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farré JC, Mahalingam SS, Proietto M, Subramani S. 2019. Peroxisome biogenesis, membrane contact sites, and quality control. EMBO Rep 20:e46864. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platta HW, Erdmann R. 2007. Peroxisomal dynamics. Trends Cell Biol 17:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wanders RJ, Waterham HR. 2006. Peroxisomal disorders: the single peroxisomal enzyme deficiencies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763:1707–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carballeira NM. 2008. New advances in fatty acids as antimalarial, antimycobacterial and antifungal agents. Prog Lipid Res 47:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiltunen JK, Mursula AM, Rottensteiner H, Wierenga RK, Kastaniotis AJ, Gurvitz A. 2003. The biochemistry of peroxisomal beta-oxidation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev 27:35–64. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu J, Aguirre M, Peto C, Alonso J, Ecker J, Chory J. 2002. A role for peroxisomes in photomorphogenesis and development of Arabidopsis. Science 297:405–409. doi: 10.1126/science.1073633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J, Baker A, Bartel B, Linka N, Mullen RT, Reumann S, Zolman BK. 2012. Plant peroxisomes: biogenesis and function. Plant Cell 24:2279–2303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparkes IA, Brandizzi F, Slocombe SP, El-Shami M, Hawes C, Baker A. 2003. An Arabidopsis pex10 null mutant is embryo lethal, implicating peroxisomes in an essential role during plant embryogenesis. Plant Physiol 133:1809–1819. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shabab M. 2013. Role of plant peroxisomes in protection against herbivores. Subcell Biochem 69:315–328. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6889-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnet C, Espagne E, Zickler D, Boisnard S, Bourdais A, Berteaux-Lecellier V. 2006. The peroxisomal import proteins PEX2, PEX5 and PEX7 are differently involved in Podospora anserina sexual cycle. Mol Microbiol 62:157–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes MJ, Murray SL, Khew GS, Davis MA. 2008. Genetic analysis of the role of peroxisomes in the utilization of acetate and fatty acids in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 178:1355–1369. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Idnurm A, Giles SS, Perfect JR, Heitman J. 2007. Peroxisome function regulates growth on glucose in the basidiomycete fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 6:60–72. doi: 10.1128/EC.00214-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okumoto K, Tamura S, Honsho M, Fujiki Y. 2020. Peroxisome: metabolic functions and biogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 1299:3–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-60204-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura A, Takano Y, Furusawa I, Okuno T. 2001. Peroxisomal metabolic function is required for appressorium-mediated plant infection by Colletotrichum lagenarium. Plant Cell 13:1945–1957. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos-Pamplona M, Naqvi NI. 2006. Host invasion during rice-blast disease requires carnitine-dependent transport of peroxisomal acetyl-CoA. Mol Microbiol 61:61–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min K, Son H, Lee J, Choi GJ, Kim JC, Lee YW. 2012. Peroxisome function is required for virulence and survival of Fusarium graminearum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25:1617–1627. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0149-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Wang J, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Liu M, Jiang H, Chai R, Mao X, Qiu H, Liu F, Sun G. 2014. MoPex19, which is essential for maintenance of peroxisomal structure and woronin bodies, is required for metabolism and development in the rice blast fungus. PLoS One 9:e85252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Wang J, Chen H, Chai R, Zhang Z, Mao X, Qiu H, Jiang H, Wang Y, Sun G. 2017. Pex14/17, a filamentous fungus-specific peroxin, is required for the import of peroxisomal matrix proteins and full virulence of Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol 18:1238–1252. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji X, Li H, Zhang W, Wang J, Liang L, Zou C, Yu Z, Liu S, Zhang KQ. 2020. The lifestyle transition of Arthrobotrys oligospora is mediated by microRNA-like RNAs. Sci China Life Sci 63:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Xiang M, Liu X. 2017. Nematode-trapping fungi. Microbiol Spectr 5:10. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0022-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Wang L, Ji X, Feng Y, Li X, Zou C, Xu J, Ren Y, Mi Q, Wu J, Liu S, Liu Y, Huang X, Wang H, Niu X, Li J, Liang L, Luo Y, Ji K, Zhou W, Yu Z, Li G, Liu Y, Li L, Qiao M, Feng L, Zhang KQ. 2011. Genomic and proteomic analyses of the fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora provide insights into nematode-trap formation. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002179. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veenhuis M, Van Wijk C, Wyss U, Nordbring-Hertz B, Harder W. 1989. Significance of electron dense microbodies in trap cells of the nematophagous fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 56:251–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00418937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dijksterhuis J, Veenhuis M, Harder W, Nordbring-Hertz B. 1994. Nematophagous fungi: physiological aspects and structure-function relationships. Adv Microb Physiol 36:111–143. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jedd G, Chua NH. 2000. A new self-assembled peroxisomal vesicle required for efficient resealing of the plasma membrane. Nat Cell Biol 2:226–231. doi: 10.1038/35008652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alnoman RB, Parveen S, Hagar M, Ahmed HA, Knight JG. 2020. A new chiral boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY)-based fluorescent probe: molecular docking, DFT, antibacterial and antioxidant approaches. J Biomol Struct Dyn 38:5429–5442. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1701555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang ZY, Soanes DM, Kershaw MJ, Talbot NJ. 2007. Functional analysis of lipid metabolism in Magnaporthe grisea reveals a requirement for peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation during appressorium-mediated plant infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:475–491. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-5-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schieferdecker A, Wendler P. 2019. Structural mapping of missense mutations in the Pex1/Pex6 complex. Int J Mol Sci 20:3756. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins CS, Kalish JE, Morrell JC, McCaffery JM, Gould SJ. 2000. The peroxisome biogenesis factors pex4p, pex22p, pex1p, and pex6p act in the terminal steps of peroxisomal matrix protein import. Mol Cell Biol 20:7516–7526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.20.7516-7526.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Y, Qu Z, Naqvi NI. 2013. The role of snx41-based pexophagy in Magnaporthe development. PLoS One 8:e79128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imazaki A, Tanaka A, Harimoto Y, Yamamoto M, Akimitsu K, Park P, Tsuge T. 2010. Contribution of peroxisomes to secondary metabolism and pathogenicity in the fungal plant pathogen Alternaria alternata. Eukaryot Cell 9:682–694. doi: 10.1128/EC.00369-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H, Tong Y, Zhou R, Wang Y, Wang Z, Ding T, Huang B. 2021. Mr-AbaA regulates conidiation by interacting with the promoter regions of both Mr-veA and Mr-wetA in Metarhizium robertsii. Microbiol Spectr 9:e0082321. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00823-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan J, Quan S, Orth T, Awai C, Chory J, Hu J. 2005. The Arabidopsis PEX12 gene is required for peroxisome biogenesis and is essential for development. Plant Physiol 139:231–239. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.066811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng S, Gu Z, Yang N, Li L, Yue X, Que Y, Sun G, Wang Z, Wang J. 2016. Identification and characterization of the peroxin 1 gene MoPEX1 required for infection-related morphogenesis and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Sci Rep 6:36292. doi: 10.1038/srep36292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park G, Colot HV, Collopy PD, Krystofova S, Crew C, Ringelberg C, Litvinkova L, Altamirano L, Li L, Curilla S, Wang W, Gorrochotegui-Escalante N, Dunlap JC, Borkovich KA. 2011. High-throughput production of gene replacement mutants in Neurospora crassa. Methods Mol Biol 722:179–189. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-040-9_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soundararajan S, Jedd G, Li X, Ramos-Pamplona M, Chua NH, Naqvi NI. 2004. Woronin body function in Magnaporthe grisea is essential for efficient pathogenesis and for survival during nitrogen starvation stress. Plant Cell 16:1564–1574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.020677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Li L, Chai R, Mao X, Jiang H, Qiu H, Du X, Lin F, Sun G. 2013. PTS1 peroxisomal import pathway plays shared and distinct roles to PTS2 pathway in development and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One 8:e55554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Liu C, Wang L, Sun S, Liu A, Liang Y, Yu J, Dong H. 2019. FgPEX1 and FgPEX10 are required for the maintenance of Woronin bodies and full virulence of Fusarium graminearum. Curr Genet 65:1383–1396. doi: 10.1007/s00294-019-00994-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrader M, Fahimi HD. 2006. Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763:1755–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhou Q, Zhang X, Wei J. 2015. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the lichen-forming fungus Endocarpon pusillum elucidates its drought adaptation mechanisms. Sci China Life Sci 58:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4760-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie M, Yang J, Jiang K, Bai N, Zhu M, Zhu Y, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2021. AoBck1 and AoMkk1 are necessary to naintain cell wall integrity, vegetative growth, conidiation, stress resistance, and pathogenicity in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Front Microbiol 12:649582. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.649582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma N, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Yang L, Li D, Yang J, Jiang K, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2021. Functional analysis of seven regulators of G protein signaling (RGSs) in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Virulence 12:1825–1840. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1948667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bai N, Zhang G, Wang W, Feng H, Yang X, Zheng Y, Yang L, Xie M, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2021. Ric8 acts as a regulator of G-protein signalling required for nematode-trapping lifecycle of Arthrobotrys oligospora. Environ Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhen Z, Xing X, Xie M, Yang L, Yang X, Zheng Y, Chen Y, Ma N, Li Q, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2018. MAP kinase Slt2 orthologs play similar roles in conidiation, trap formation, and pathogenicity in two nematode-trapping fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 116:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen SA, Lin HC, Schroeder FC, Hsueh YP. 2021. Prey sensing and response in a nematode-trapping fungus is governed by the MAPK pheromone response pathway. Genetics 217:iyaa008. doi: 10.1093/genetics/iyaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barron GL. 2003. Predatory fungi, wood decay, and the carbon cycle. Biodiversity 4:3–9. doi: 10.1080/14888386.2003.9712621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang L, Liu Z, Liu L, Li J, Gao H, Yang J, Zhang KQ. 2016. The nitrate assimilation pathway is involved in the trap formation of Arthrobotrys oligospora, a nematode-trapping fungus. Fungal Genet Biol 92:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang X, Ma N, Yang L, Zheng Y, Zhen Z, Li Q, Xie M, Li J, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2018. Two Rab GTPases play different roles in conidiation, trap formation, stress resistance, and virulence in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:4601–4613. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8929-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou D, Xie M, Bai N, Yang L, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2020. The autophagy-related gene Aolatg4 regulates hyphal growth, sporulation, autophagosome formation, and pathogenicity in Arthrobotrys oligospora. Front Microbiol 11:592524. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.592524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhen Z, Zhang G, Yang L, Ma N, Li Q, Ma Y, Niu X, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2019. Characterization and functional analysis of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs) in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:819–832. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park HS, Bayram O, Braus GH, Kim SC, Yu JH. 2012. Characterization of the velvet regulators in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol Microbiol 86:937–953. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernhards Y, Poggeler S. 2011. The phocein homologue SmMOB3 is essential for vegetative cell fusion and sexual development in the filamentous ascomycete Sordaria macrospora. Curr Genet 57:133–149. doi: 10.1007/s00294-010-0333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma Y, Yang X, Xie M, Zhang G, Yang L, Bai N, Zhao Y, Li D, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2020. The Arf-GAP AoGlo3 regulates conidiation, endocytosis, and pathogenicity in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Fungal Genet Biol 138:103352. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2020.103352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L, Li X, Bai N, Yang X, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2022. Transcriptomic analysis reveals that Rho GTPases regulate trap development and lifestyle transition of the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0175921. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01759-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie M, Bai N, Yang J, Jiang K, Zhou D, Zhao Y, Li D, Niu X, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2019. Protein kinase Ime2 is required for mycelial growth, conidiation, osmoregulation, and pathogenicity in nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Front Microbiol 10:3065. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu J, Wang ZK, Sun HH, Ying SH, Feng MG. 2017. Characterization of the Hog1 MAPK pathway in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Environ Microbiol 19:1808–1821. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Zhu J, Ying SH, Feng MG. 2014. Three mitogen-activated protein kinases required for cell wall integrity contribute greatly to biocontrol potential of a fungal entomopathogen. PLoS One 9:e87948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou D, Zhu Y, Bai N, Yang L, Xie M, Yang J, Zhu M, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2022. AoATG5 plays pleiotropic roles in vegetative growth, cell nucleus development, conidiation, and virulence in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora. Sci China Life Sci 65:412–425. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang L, Li X, Xie M, Bai N, Yang J, Jiang K, Zhang KQ, Yang J. 2021. Pleiotropic roles of Ras GTPases in the nematode-trapping fungus Arthrobotrys oligospora identified through multi-omics analyses. iScience 24:102820. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li B, Dewey CN. 2011. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download SPECTRUM00275-22_Supp_1_seq2.pdf, PDF file, 1.8 MB (1.9MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published paper and the associated supplemental files. The raw sequence has been deposited to GEO under accession number GSE193953.