Abstract

Importance:

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune mediated inflammatory disease of the esophagus, that affects an estimated approximately 150,000 people in the United States. EoE affects both children and adults and causes dysphagia, food impaction of the esophagus, and esophageal strictures.

Observations:

Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction such as vomiting, dysphagia, or feeding difficulties in a patient with an esophageal biopsy demonstrating at least 15 eosinophils/high powered field in the absence of other conditions associated with esophageal eosinophilia such as gastroesophageal reflux disease or achalasia. Genetic factors and environmental factors such as exposure to antibiotics early in life are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Current therapies include proton pump inhibitors, topical steroid preparations, such as fluticasone and budesonide, dietary therapy with amino acid formula or empiric food elimination, and endoscopic dilation. In a systematic review of observational studies that included 1,051 patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, proton pump inhibitor therapy was associated with a histologic response, defined as < 15 eosinophils on endoscopic biopsy, in 41.7% of patients, while placebo was associated with a 13.3% response rate. In a systematic review of eight randomized trials of 437 patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, topical corticosteroid treatment was associated with histologic remission in 64.9% of patients, compared to 13.3% for placebo. Patients with esophageal narrowing may require dilation. Objective assessment of therapeutic response typically requires endoscopy with biopsy.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Eosinophilic esophagitis affects an estimated approximately 150,000 people in the United States, including children and adults. Treatments consist of proton pump inhibitors, topical steroids, elemental diet, and empiric food elimination, with esophageal dilation reserved for patients with symptomatic esophageal narrowing.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, diagnosis, therapy, epidemiology

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune mediated inflammatory condition of the esophagus. The incidence of EoE is approximately 5–10 cases per 100,000 per year and the prevalence is approximately 0.5–1 case per 10001. This review summarizes current evidence regarding diagnosis and treatment of EoE.

Methods/Literature Search

A literature search was performed in PubMed for the period between January 1, 2010 and May 13, 2021 by a clinical librarian. Key concepts were eosinophilic esophagitis, therapy, diagnosis, epidemiology, randomized clinical trials and umbrella reviews. Controlled vocabulary and keywords associated with each concept were examined and combined with Boolean operators in a logic way. The search syntax can be found in Appendix 1 in the supplement. Of 323 articles retrieved, six systematic reviews/meta-analysis, 8 clinical trials, and 5 observational studies were included in this review.

Diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis

Based on the 2018 AGREE (A Working Group on PPI-REE) international consensus conference, eosinophilic esophagitis is defined by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction such as vomiting, dysphagia, or feeding difficulties in a patient with esophageal biopsies demonstrating at least 15 eosinophils/high powered field in the absence of other conditions associated with esophageal eosinophilia such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, achalasia, vasculitis, hypereosinophilic syndrome, Crohn disease, Ehler’s Danlos syndrome, graft versus host disease, infections and drug hypersensivity (Table 1).2 A trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to exclude a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease is no longer considered appropriate in diagnosing eosinophilic esophagitis2.

Table 1:

Diagnostic criteria for EoE

|

|

|

Epidemiology

In a meta-analysis of 27 population based studies including 10 in children and 5 in adults, the pooled incidence of EoE was 6.6/100,000/year in children 7.7/100,000/year in adults3. The prevalence varies by country and continent. The most recent pooled prevalence data demonstrated 34.4 cases/100,000 (42.2/100,000 for adults and 34/100,000 for children.3The incidence of EoE is increasing, perhaps due to increasing awareness of EoE along with increased rates of biopsy sampling of the esophagus during esophogastroduodenoscopy. However, additional evidence suggests an overall increase in the incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis even after taking into account increased disease awareness, a phenomenon also observed for other atopic diseases5.

Pathophysiology

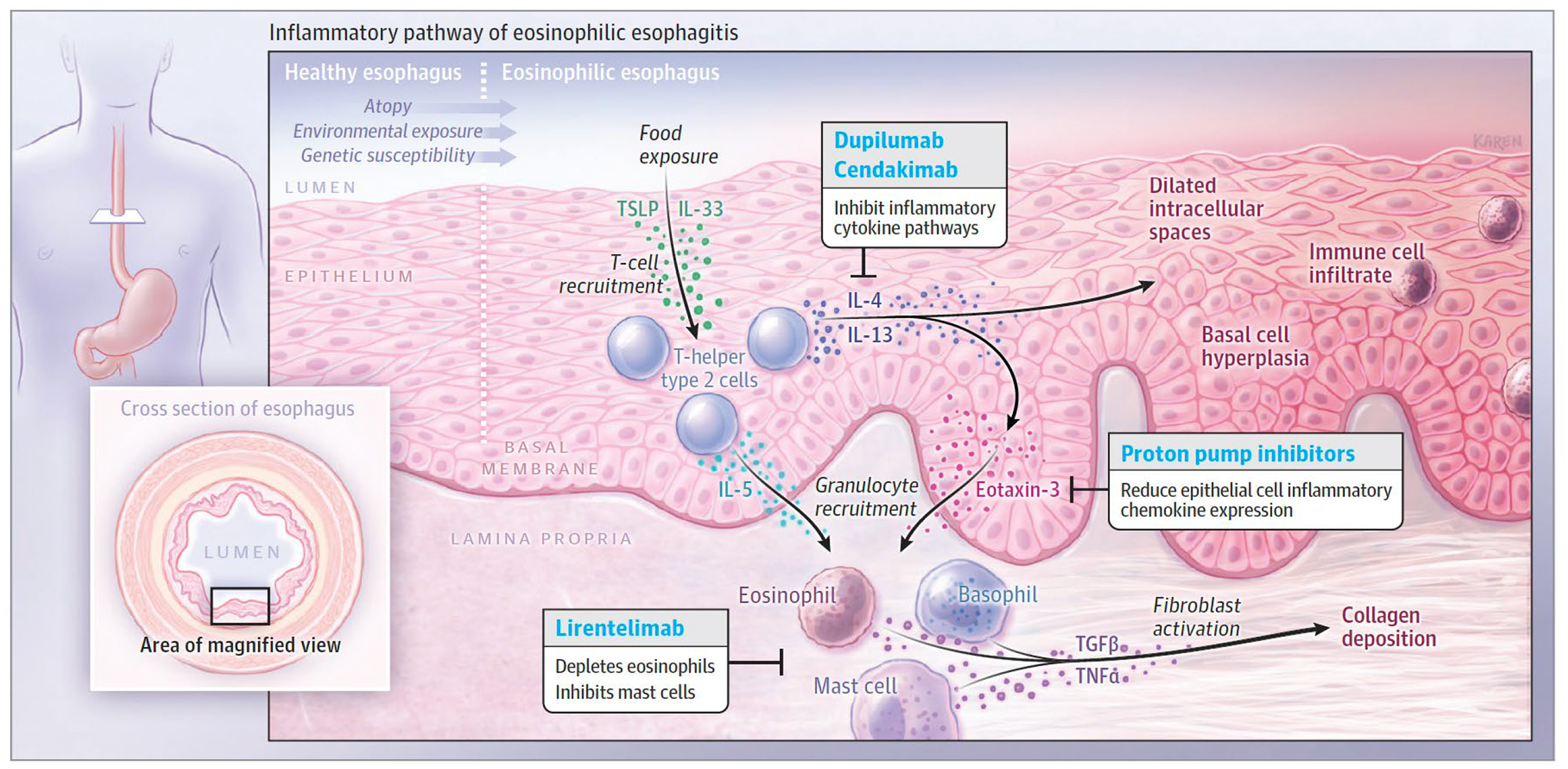

The pathophysiology of EoE is incompletely understood. In susceptible individuals, exposure to foods that are ubiquitous in the diet, such as milk and wheat, is associated with infiltration of the esophageal mucosa with a mixed granulocyte population (eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils)6,7. This inflammation diminishes epithelial barrier integrity, damages the mucosa, and is associated with fibrosis of the esophagus over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Early-life exposures, genetic factors, and an atopic state likely increase disease susceptibility in eosinophilic esophagitis. Exposure to antigens causes the esophageal epithelium to release alarmins, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). These cytokines in turn stimulate T-helper type 2 (Th2) cells’ secretion of IL-13, IL-4, and IL-5. IL-13 and IL-4 stimulate the changes seen in the esophageal epithelium, including basal cell hyperplasia and dilated intracellular spaces. Chemotaxins, eotaxin-3 and IL-5, lead to granulocyte infiltration. The mixed cytokine milieu also contributes to the activation of fibroblasts in the lamina propria, collagen deposition, and tissue stiffness.

Genetics and Environment

EoE is more common among first degree relatives of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, who have a higher risk of developing EoE than the general population.8Genome Wide Array Studies have identified 31 candidate genes including TSLP, CAPN14, and EMSY9–12 that were associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. In addition to these genetic risk factors, unknown environmental factors, especially in early life, are associated with development of EoE. In twin studies, the frequency of EoE in a monozygotic twin of a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis is 41% and 24% in a dizygotic twin of a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis.8 The risk of eosinophilic esophagitis is approximately 2.4% in siblings with the disease, suggesting a perinatal shared environmental risk factor beyond genetics.8 In four of five observational studies that evaluated early life exposures associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, antibiotic exposure during infancy was associated with increased risk for development of EoE13. EoE may also be associated with Caesarian delivery (OR, 2.2; CI 95% 0.8–6.414 and OR, 1.77; CI 95% 1.01–5.0915) and formula feeding (OR 3.5; CI 85% 0.6–19.5)14 Whether the microbiota of the esophagus contribute to disease pathogenesis remains unclear16.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of EoE varies depending on age at presentation. Infants and young children are more likely to present with nonspecific symptoms or signs such as failure to thrive, feeding difficulties and vomiting. Adolescents and adults typically have symptoms associated with esophageal fibrosis, with over 70% of adults presenting with dysphagia and 30% presenting with food impactions17. Approximately 50% of patients who present on an emergency basis with an esophageal food impaction requiring endoscopic removal have eosinophilic esophagitis18,19. In patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, longer periods of untreated inflammation are associated with a higher prevalence of esophageal fibrosis, dysphagia, and food impaction.20 A cohort study of 721 patients from the Netherlands with eosinophilic esophagitis reported that in patients with symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis for >21 years at the time of diagnosis, the proportions of patients with strictures and esophageal food impactions were 52% and 57% respectively. For patients with symptom duration of < 2 years at the time of diagnosis, the proportions were 19% and 24%, respectively. It was estimated that for each year of symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis that were untreated, the risk of stricture increased by 9% (95% CI, 1.05–1.13).21

Patients with EoE typically modify their eating behavior by chewing thoroughly, selecting softer foods, and drinking frequently during meals. These behaviors may contribute to a delay in diagnosis. Adults with EoE are typically diagnosed a mean of seven years after symptom onset.20

Diagnosis and Assessment

Endoscopy

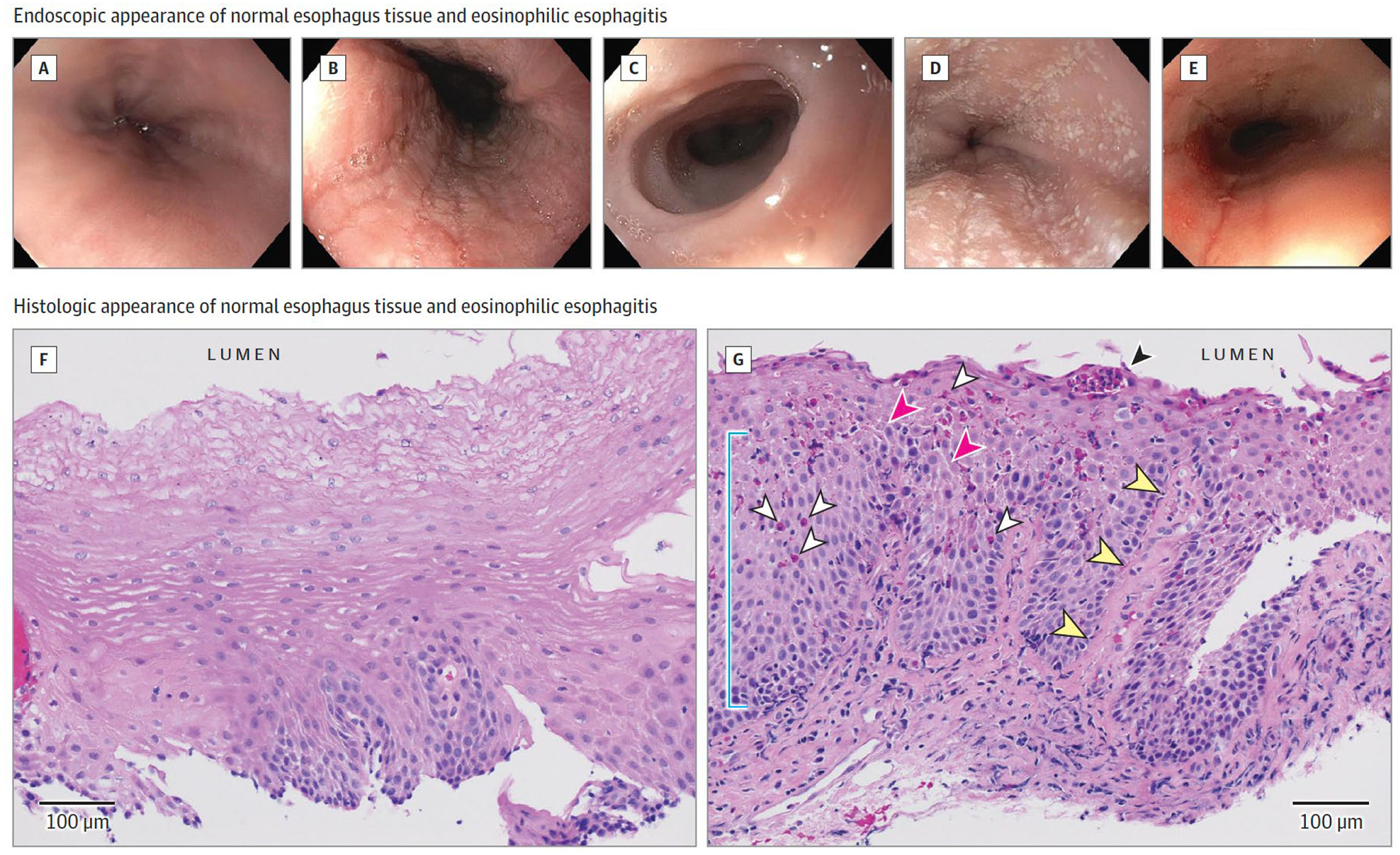

Diagnosis of EoE requires endoscopy with biopsy. Endoscopic findings in patients with EoE consist of furrows (appearing as vertical lines within the mucosa), trachealization (appearing as concentric rings of esophageal narrowing), exudates (white plaques), edema (decreased vasculature of mucosa), and stricture (Figure 2).22 The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) evidence based approach to diagnosis and management of EoE recommends obtaining a minimum of six biopsies (including both proximal and distal esophagus) from any patient who may have EoE. In approximately 10–25% of patients with EoE, the esophagus may have a normal appearance on endoscopy.23

Figure 2.

Endoscopic and Histologic Appearance of the Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE) Esophagus

Endoscopy of EoE: normal esophagus (A); linear furrows (B); mucosal pallor representing edema, decreased vascular pattern, and concentric rings or trachealization (C); small white plaques (D); and esophageal narrowing and rent due to endoscope passage (E). Histology (hematoxylin and eosin) of EoE: F, Normal esophageal squamous epithelium with inconspicuous basal layer, luminal squamous differentiation, and absence of inflammation. G, EoE mucosa demonstrating elongated papilla (yellow arrowheads), basal cell hyperplasia (blue line), infiltrating eosinophils (white arrowheads), eosinophil microabscess (black arrowhead), and epithelial spongiosis (pink arrowheads). Images courtesy of Benjamin Wilkins, MD, PhD, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Pathology

Even in the setting of visual findings on endoscopy, EoE requires histology to confirm the diagnosis. Currently, ≥ 15 eosinophils per high powered field in the maximally affected high powered field is required for diagnosis.2 This threshold value has been shown to be 100% sensitive and 96% specific for diagnosis.24. The goal of therapy is to reduce the eosinophil count below 15 eosinophils per high powered field.

New and Emerging Diagnostic Methods

Symptoms of feeding difficulties and dysphagia are not a reliable indicator of continued EoE disease activity and resolution of symptoms is not a reliable indicator of remission.25 While no clinical trials have demonstrated that serial endoscopy tests in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis improve outcomes, the authors recommend a follow up endoscopy for patients after therapy initiation for eosinophilic esophagitis to document histologic remission. In addition, it is essential to ensure remission is maintained, because active esophageal inflammation is associated with fibrostenosis and stricture.20 Progression to fibrosis was shown in a retrospective study of 200 adults with EoE in which a longer duration of untreated EoE was associated with fibrosis.20 Patients with less than two years of untreated disease had a 17.2% stricture prevalence, those with a 5–8 year delay in treatment had a 38.9% stricture prevalence, and those with a delay in treatment exceeding 20 years had a 70.8% stricture prevalence20. New noninvasive technologies are under study to measure disease activity without the need for sedated endoscopy.

Noninvasive methodologies to determine disease activity

A noninvasive approach to assess disease activity involves use of a capsule containing a mesh sponge with a string attached. The capsule is swallowed while the patient holds the string outside of the mouth. Once the capsule dissolves, the mesh sponge expands and is removed by pulling the string through the mouth. Esophageal scrapings are collected in the mesh matrix and formalin fixed for histologic analysis. A multicenter proof of principle study demonstrated that 102 of 105 patients had adequate tissue isolated from the sponge for analysis with a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 86% for determining disease activity, defined by eosinophil count on biopsy.26

The esophageal string test (EST) uses a capsule with an absorptive string in a capsule that unravels in the esophagus while the patient holds the string outside of the mouth. The string stays in place for one hour and is then pulled out of the mouth. Unlike the capsule containing a mesh sponge with a string attached that collects esophageal tissue, the sting absorbs esophageal secretions. In a study involving 134 patients, analysis of eosinophil granule proteins and cytokines on the string was 80% sensitive and 75% specific for determining EoE disease activity, defined by eosinophil count on biopsy.27

Transnasal endoscopy could be performed without sedation and consists of passing a thin endoscope through the nares into the esophagus where biopsies are obtained. This procedure can be performed in children as young as six years of age, and may be facilitated with the aid of virtual reality goggles to help distract children from the ongoing procedure.28

Approaches to Assess Esophageal Function

Determining which patients will have a narrow caliber esophagus or a fibrostenotic phenotype esophagus is possible with genetic testing or use more invasive techniques. A 96-gene quantitative polymerase chain reaction panel has been developed that can distinguish EoE patients from controls.29,30 In an investigation that included 185 patients in the discovery cohort and 100 patients in the validation cohort, patients evaluated with this panel, were classified as having either fibrostenotic (RR, 7.98; 95% CI 1·84–34·64; p=0·0013) or inflammatory and steroid refractory eosinophilic esophagitis (RR, 2·77; 95% CI 1·11–6·95; p=0·0376) based on gene expression in the tissue (absolute rates not provided.

The Functional Luminal Imaging Probe (FLIP) is an FDA approved measuring that can be used during sedated upper endoscopy. FLIP is a balloon that is inflated in the esophagus that measures pressure and diameter along 16 cm of the esophagus to determine esophageal distensibility and compliance.31–33 FLIP measurements in children and adults demonstrated that patients with a history of food impactions have decreased distensibility compared to those without complications. Specifically, the distensibility plateau of those with food impactions (n=19) was 113mm2 compared to 229mm2 in those (N=30) without these complications.34

Therapy

There are no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved treatments for EoE. Currently available treatments are listed in Table 2. Therapies should be selected based on efficacy, ease of administration, cost, and patient preference. A shared decision making model with patients that reviews benefits and drawbacks of each option is recommended.35

Table 2.

Current Treatment Options for EoE

| Treatment Approach | Dose or methods | Pooled Histologic Response | Adverse Effects | Other considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton pump inhibitors* | Omeprazole or equivalent 20 mg bid | 41.7% in a systematic review of observational data of 1,051 participants, compared to a historical placebo comparison group of 13.3%36 | Acute: Headache < 5%67 Diarrhea < 5%67 Enteric infections (1.4% in 53 152 patient years of follow-up)50 Proposed Chronic:48 Chronic kidney disease 0.1–0.3% per patient/yr Bone fracture 0.1–0.5% per patient/year Dementia .07–1.5% per patient/year |

Low cost Readily available Ease of administration Well tolerated. |

| Topical corticosteroids | Fluticasone 440–880 ug bid Budesonide 1–2 mg bid |

64.9% in 8 randomized controlled trials of 437 patients compared to 13.3% treated with placebo36 | Esophageal candida 12–16% Oral thrush 2–3%51 |

Off label use of asthma medications results in need to repurpose as slurry for budesonide and swallow instead of inhale for fluticasone Cost may be considerable as not always covered by insurance |

| Elemental diet | Consists of diet exclusively made up of amino acid based formula | 93.6% in an 6 observational studies of 431 patients vs. 13.3% in a historical placebo comparison group36. | Cost Palatability is poor After elemental diet, reintroduction of food groups may increase IgE mediated allergies. |

|

| 6 food elimination diet | Eliminated foods consist of eliminating milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, and fish/seafood | 67.9% in a systematic review of 633 patients in 9 observational studies, compared to 13.3% response in a historical placebo comparison group.36 | Dairy and wheat are the most commonly implicated food groups. Requires multiple endoscopies to identify culprit food group[s] Requires well motivated patient |

Dietary Elimination

Because EoE is a non-IgE mediated allergic disease, attempting to eliminate the allergens may result in disease remission in some patients. There are three approaches to dietary therapy: an elemental diet (exclusively drinking a formula without any intact protein, i.e. amino acid based formulas), empiric food elimination, and allergy test directed food elimination. An elemental diet consists of a liquid form of nutrition comprised of amino acids, fats, sugars, vitamins, and nutrients that is readily assimilated and absorbed. A recent systematic review of six single group observational studies with 431 patients reported that an elemental diet was associated with histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils/high powered field) in 93.6% of patients, compared to 13.3% in a historical placebo comparison groups from clinical trials of topical corticosteroid (RR, 0.07; 95% CI,0.05–0.12)36 However, this approach is costly, inconvenient, and associated with undesirable taste. In addition, it can be difficult to ingest sufficient formula to maintain body weight and some patients require a feeding tube due to palatability problems from the formula. After elemental diet nutrition, reintroduction of food groups may be associated with de novo development of IgE mediated food allergies. Therefore, this approach is best used in collaboration with an allergist to assist with food reintroduction to avoid acute allergic reaction.37

Empiric elimination of food groups commonly implicated in eosinophilic esophagitis is another dietary approach. The most common approach is elimination of the six most common food groups associated with eosinophilic esophagitis: milk, wheat, eggs, soy, peanuts/tree nuts and fish/shellfish.38 A recent systematic review of 9 single group observational studies with a total of 633 EoE patients found that dietary elimination was associated with a histologic response in 67.9% or patients (< 15 eosinophils/hpf) compared to 13.3% in a historical placebo comparison group (RR 0.38; 95% CI, 0.32–0.43)36. Dairy, wheat and eggs are the most commonly implicated food groups. In patients who respond, foods can be reintroduced sequentially. A practical approach to food reintroduction is to start with fish/seafood and peanuts/tree nuts followed by endoscopy after six weeks. Patients who attain a response, defined as < 15 eosinophils/high powered field, may add dietary soy and eggs. If another repeat endoscopy after six weeks demonstrates continued response, wheat may be introduced, followed by repeat endoscopy to assess response, dairy introduction, and repeat endoscopy.38,39 The repeated endoscopies, dietary adherence and long-term dietary restrictions can be challenging for patients. Therefore, several less restrictive approaches have been studied. Pooled histologic response from a limited number of single arm observational studies for four (milk, wheat, eggs and legumes) (3 single group studies, n=426), two (milk and wheat) (two single group, n=311) and one food (milk) (two group studies, n=203) elimination diets were 56.9%, 42.1% and 54.1% respectively.36 These approaches involve fewer endoscopies and better convenience for patients. The decision to follow a step-down approach by starting with a six food elimination diet or a step up approach by starting with either a one, two, or four food elimination diet is best handled by shared decision making with the patient.

Another dietary approach is to use allergy testing to detect potential food triggers, using results to prescribe dietary elimination. However, EoE is not an IgE mediated disease and allergy testing (prick testing, serum IgE testing, and patch testing) is not standardized for non-IgE mediated disease. A systematic review of 11 single group studies, with 830 patients reported that allergy directed elimination diet was associated with a response rate of 50.8%, compared to 13.3% in a historical placebo comparison group (RR 0.57; 95% CI,0.33–0.73).36

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Until 2018, an endoscopy with biopsy showing >15 eosinophils per high powered field after an eight-week trial of high dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (i.e. omeprazole 40 mg daily) was considered standard care to exclude esophageal inflammation due to gastroesophageal reflux disease and an entity known as PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE), in which patients had symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and > 15 eosinophils per high-powered field with improvement of both in response to high dose PPI therapy. However, an updated diagnostic algorithm in 2018 eliminated the requirement of a PPI trial as a diagnostic requirement, and instead classified PPIs as a treatment option for patients with EoE.2 This change was based on studies demonstrating that the clinical, endoscopic, histologic and molecular characteristics of PPI-REE and eosinophilic esophagitis were similar40–42 and there was no difference between PPI-REE and EoE. In EoE, PPIs may have anti-inflammatory effects independent of gastric acid suppression: anti-oxidant properties, inhibition of immune cell function, and reduction of epithelial cell inflammatory cytokine expression.41,43,44

A systematic review of 23 observational studies with 1051 patients with eosinophilic esophagitis reported that PPI therapy was associated with a histologic response in 41.7% of patients (defined as <15 eosinophils per high powered field) compared to 13.3% in the historical placebo group (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61–0.72).36 An earlier systematic review and meta-analysis of 33 observational studies (11 prospective observational studies and 2 randomized clinical trials) comprising 619 patients reported symptomatic improvement in 60.8% (95% CI, 48.4%-72.2%;) of patients treated with PPIs but heterogeneity in these analyses was considerable I2 80.2%)45

PPIs are a reasonable first line therapy for EoE given their low cost, tolerability, generally favorable safety profile, and ease of administration. There does not seem to be a difference in efficacy between different PPIs or between administration once daily versus twice daily.46 However, PPIs may be less effective in patients who have failed to respond to topical corticosteroids or dietary therapy as well as in patients with a fibrostenotic phenotype.47

Potential harms of long-term PPI therapy include associations of PPIs with pneumonia, dementia, myocardial infraction, chronic kidney disease, fracture, enteric infections, small bowel bacterial overgrowth, Clostridium difficile-associated infection, and micronutrient deficiency anemia.48. However, evidence is inadequate to establish any causal relationship between PPIs and many of the effect sizes are small (absolute increase risk from 03% to 1.5% per patient/year)49. A 3 year randomized clinical trial that assessed the safety of PPIs among 17,598 participant with stable cardiovascular disease and peripheral artery disease receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin reported no difference in safety events with the exception of enteric infections between the PPI and placebo groups(1.4% vs 1.0%; OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01–1.75).50

Swallowed Topical Steroids to Treat Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Swallowed corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy of EoE, however, no formulations are approved yet by the FDA for eosinophilic esophagitis treatment. A recent double blind clinical trial by Dellon et al. randomized 111 adults with a new diagnosis of EoE randomized to either fluticasone 880 ug swallowed twice daily from a multidose inhaler or oral viscous budesonide 1 mg twice daily for eight weeks.51 Peak eosinophil counts declined from 73 to 15 in the budesonide group and from 77 to 31 in the fluticasone group (P = .31). Histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils/hpf) occurred in 71% of the budesonide and 64% of the fluticasone patients (P = 0.38) and change in symptoms, as measured by the dysphagia symptom questionnaire, was no different between either budesonide or fluticasone participants (−5.8 + 9.6 vs −4.0 + 8.3, P = 0.37). However, this randomized trial was limited by the lack of a placebo comparator.

A recent systematic review of eight double blind placebo controlled clinical trials of topical corticosteroid treatment that included 437 patients for a mean of 8 weeks reported that topical corticosteroids were associated with histologic remission in 64.9% of patients (<15 eosinophils/hpf), compared to 13.3% in patients treated with placebo (RR 0.39, 95% CI, 0.85–1.19).36 Clinical trials have evaluated initial treatment duration of 2 to 12 weeks. In a randomized clinical trial of 88 adults, budesonide orodispersible tablets (1 mg twice daily) attained both clinical and histologic remission in 57.6% of patients at six weeks and 84.7% at 12 weeks.52 This suggests that optimal initial duration of topical steroid therapy is approximately 12 weeks.

Topical corticosteroids are well tolerated and the most common adverse effects with short term treatment with topical corticosteroids is asymptomatic esophageal Candida infection which occurred in 12–15% of patients in the randomized clinical trial described above.51 In a systematic review of seven randomized clinical trials of 367 patients, there was no association of topical steroid use with adrenal insufficiency, compared to placebo.53 However, in a recently published clinical trial of 318 patients randomized to a higher dose of budesonide suspension (2 mg twice daily) or placebo administered for 8 weeks, adrenal suppression was encountered in 1.4% and adrenal insufficiency in 0.9% of the budesonide group compared to no such events in the placebo group54. Current evidence suggests that swallowed steroids for topical treatment of the esophagus are safe, with minimal systemic absorption.37

Efforts to develop esophageal specific corticosteroid preparations are ongoing. The European Medicines Agency has approved budesonide orodispersible tablets.52 A premixed oral budesonide oral suspension has been evaluated in a phase 3 clinical trial of 318 patients randomized to either budesonide oral suspension 2 mg or placebo twice daily. Both the histologic (53.1% vs 1.0%, P < .001) and symptom responses (52.6% vs 39.1%, P = .024) were greater in the budesonide group compared to placebo.54

Dilation

Endoscopic dilation is a therapeutic option for treating esophageal strictures, rings, and narrow caliber esophagus in patients with EoE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 studies (one randomized clinical trial, 18 cohort studies, 2 case series and 6 case reports) including 845 patients found that dilation was associated with clinical improvement in 95% of EoE patients [95% CI, 90%-98%] with a median duration of improvement of 12 months [range 1 week-36 months].55 Despite early concerns about increased perforation rates with dilation, esophageal dilation is generally safe. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 studies (one randomized clinical trial, 25 cohort studies, 1 case control study and 10 case series or case reports) including 2034 dilations in 977 patients with EoE reported that dilation was associated with a perforation rate of 0.033% [95% CI, 0%-0.226%], bleeding rate of 0.028% [95% CI, 0%-0.217%] and hospitalization rate of 0.689% [95% CI 0%-1.42%].56 Chest discomfort was the most frequent adverse event, which occurred in 23.6% [95% CI, 5.89%-41.3%].55 However, dilation did not improve esophageal eosinophilic inflammation and ongoing mucosal damage.57 This is important because histologic remission (<15 eosinophils per hpf) is associated both with a greater likelihood of improved esophageal diameter and a decreased need for subsequent dilation.58

Optimal timing of dilation in EoE patients remains unclear. Ideally, inflammation should be controlled prior to initiating dilation. However, in the setting of medication nonadherence, strictures that do not respond to medical therapy, high grade stenosis, or recurrent food impaction, esophageal dilation may be considered prior to control of inflammation.59 The target goal of therapy should be an esophageal diameter of 15–18 mm.23

Combination Therapy

There are limited data on the effectiveness of multimodal therapy, consisting of topical steroids, PPIs, and dietary elimination..60,61 One observational cohort study of 23 patients, of whom 21 were previously treated with topical corticosteroids or food elimination monotherapy found global symptomatic improvement in 82%.61 However, the use of multiple therapies is associated with increased cost and adherence challenges. If multimodal therapy results in symptomatic and histologic remission, it is challenging to determine which treatment modality was effective. For patients with concomitant symptoms of reflux such as heartburn and acid regurgitation, therapy with a histamine H2-antagonist or a PPI at the lowest dose (omeprazole 20 mg daily) to control symptoms is warranted. For patients who do not respond to any first line therapies, consideration should be given to potential causes of ongoing symptoms including poor adherence, inadequate dosing of medications, inappropriate administration of topical steroids or fibrostenosis.60 Patients who do not respond to standard therapy should also consider enrolling in clinical trials testing new agents. It remains unknown if multimodal therapy is effective for disease refractory to single agent therapy.

Emerging Therapies: Biologics

A variety of monoclonal antibodies that either directly target eosinophils or inflammatory cytokine pathways are now undergoing clinical trials (NCT03633617, NCT04322708, NCT04543409, NCT04682639, NCT04753697). These compounds have the potential to treat EoE and concomitant atopic diseases and offer the convenience of less frequent dosing schedules. However, the AGA/Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology (AGA-JTF) guidelines recommend that these therapies should only be considered in the context of a clinical trial.37

Maintenance Therapy

EoE is a chronic inflammatory disease. Observational studies suggest that untreated EoE is associated with disease progression characterized by strictures and esophageal narrowing as described above.20,62 Furthermore, symptomatic, endoscopic and histologic relapse, defined as > 15 eosinophils per high powered field typically occur after therapy cessation. In the observation phase of the randomized clinical trial of fluticasone versus budesonide described above, 33 of 58 patients (57%) had symptom recurrence before 1 year of therapy cessation with a median time to symptom recurrence of 244 days.63 In an observational single center study of 33 patients who had achieved clinical, endoscopic and histologic remission, 27 (82%) had a relapse of EoE symptoms of dysphagia or chest pain at a median of 22.4 weeks [95% CI, 5.1–39.7] after cessation of swallowed topical steroids.64 The AGA-JTF recommends continuation of topical steroids over discontinuation of therapy, based on a single trial of 28 patients that randomized patients to low dose budesonide (0.25 mg twice daily) or placebo.65 However, since the publication of the AGA-JTF recommendations, a 48 week European randomized clinical trial of maintenance therapy of budesonide orodispersible tablets in 204 patients reported that the primary combined end point of clinical and histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils per high powered field) occurred in 75%, 73.5% and 4.4% of patients given 1 mg twice daily, 0.5 mg twice daily and placebo66. Furthermore, median time to relapse in the placebo group was 87 days. The approach to maintenance therapy should involve shared decision making, but rapid return of symptoms and prior complications such as food bolus impaction, strictures or narrow caliber esophagus characterized by inability to pass an adult endoscope of 9 mm diameter would favor maintenance therapy over no therapy.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, quality of evidence was not formally assessed. Second, some relevant references may have been missed. Third, natural history studies suggesting progression to esophageal narrowing are based on retrospective data. Fourth, other than for topical corticosteroid therapy, no randomized clinical trials evaluating other treatment modalities have been conducted.

Conclusions

Eosinophilic esophagitis affects an estimated approximately 150,000 people in the United States, including children and adults. Treatments consist of proton pump inhibitors, topical steroids, elemental diet, and empiric food elimination, with esophageal dilation reserved for patients with symptomatic esophageal narrowing.

Table 3.

Frequently Asked Questions

| What are the most frequent presenting symptoms in EoE? The most frequent symptoms in adults and adolescents are dysphagia and food impactions. In children vomiting, weight loss, and heartburn are more common. |

| How is the diagnosis of EoE typically made? EoE is diagnosed by endoscopy with biopsy of the esophagus showing >15 eosinophils per hpf. |

| What is the natural history of EoE? Over time, untreated eosinophilic esophagitis can lead to esophageal fibrosis and stricture. |

| What is first line therapy for EoE? There is no accepted first line therapy for EoE and no therapy is 100% effective. Shared decision making examining risks and benefits of an elimination diet, PPIs, topical steroids, dilation or enrollment into clinical trials be offered to patients with EoE. |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NIDDK Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Disease P30DK050306 and by the Consortium for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Research (CEGIR) U54 AI117804 which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, and is funded through collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK, and NCATS. CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED), and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). As a member of the RDCRN, CEGIR is also supported by its Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) (U2CTR002818). ABM is funded by R01 DK124266-01, R21TR00303902.

Financial Statement

Dr. Falk receives research funding from Allakos, Arena, Adare/Ellodi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Lucid and Shire/Takeda and is a consultant for Allakos, Adare/Ellodi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Lucid and Shire/Takeda.

Dr. Muir receives research funding from Allakos.

Appendix

| Search No. | Search Syntax | No. of Records |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Eosinophilic Esophagitis”[Mesh] OR “Eosinophilic Esophagitis” [tw] | 2,935 |

| 2 | Therapeutics [Mesh] OR therapeutic [tw] OR therapeutics [tw] OR “therapy”[MeSH Subheading] OR therapy [tw] OR therapies [tw] OR treatment [tw] OR treatments [tw] | 11,777,253 |

| 3 | “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[tw] OR “diagnose”[tw] OR “diagnosed”[tw] OR “diagnoses”[tw] OR “diagnosing”[tw] OR “diagnosable”[tw] OR “diagnosi”[tw] | 10,314,584 |

| 4 | “epidemiology”[MeSH Terms] OR “epidemiology”[MeSH Subheading] OR”epidemiologies”[tw] OR “epidemiology”[tw] OR “epidemiology s”[tw] | 2,333,510 |

| 5 | “systematic review”[Publication Type] OR “systematic review”[tw] OR “systematic reviews”[tw] | 210,573 |

| 6 | “meta analysis”[Publication Type] OR “meta analysis”[tw] OR metaanalysis [tw] OR meta-analysis [tw] | 200,279 |

| 7 | “practice guideline”[Publication Type] OR “practice guideline”[tw] | 32,683 |

| 8 | “guideline”[Publication Type] OR “guideline”[tw] OR guidelines [tw] | 488,082 |

| 9 | “randomized controlled trial”[Publication Type] OR “randomized controlled trials”[tw] OR “randomised controlled trials”[tw] | 700,854 |

| 10 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 | 17,678,276 |

| 11 | #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 | 1,374,715 |

| 12 | #1 AND #10 AND #11 | 324 |

| 13 | Limit #12 to 2010–2020 | 303 |

References

- 1.Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):319–332.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. In: Gastroenterology. Vol 155. W.B. Saunders; 2018:1022–1033.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarro P, Arias Á, Arias-González L, Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Ruiz-Ponce M, Lucendo AJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the growing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population-based studies. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2019;49(9):1116–1125. doi: 10.1111/apt.15231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(4):589–596.e1. doi: 10.1016/J.CGH.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomsen SF. Epidemiology and natural history of atopic diseases. European Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2015;2(1):24642. doi: 10.3402/ecrj.v2.24642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noti M, Wojno EDT, Kim BS, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nature Medicine. 2013;19(8):1005–1013. doi: 10.1038/nm.3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aceves SS, Chen D, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Bastian JF, Broide DH. Mast cells infiltrate the esophageal smooth muscle in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, express TGF-β1, and increase esophageal smooth muscle contraction. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010;126(6). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander ES, Martin LJ, Collins MH, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;134(5):1084–1092.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(4):289–291. doi: 10.1038/ng.547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleiman PMA, Wang ML, Cianferoni A, et al. GWAS identifies four novel eosinophilic esophagitis loci. Nature Communications. 2014;5. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherrill JD, Rothenberg ME. Genetic and epigenetic underpinnings of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2014;43(2):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottyan LC, Parameswaran S, Weirauch MT, Rothenberg ME, Martin LJ. The genetic etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2020;145(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Environmental factors and eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2018;142(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ET J, MD K, HP K, T R-K, ES D. Early life exposures as risk factors for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2013;57(1):67–71. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0B013E318290D15A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ET J, JT K, LJ M, CD L, ES D, ME R. Early-life environmental exposures interact with genetic susceptibility variants in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2018;141(2):632–637.e5. doi: 10.1016/J.JACI.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muir AB, Benitez AJ, Dods K, Spergel JM, Fillon SA. Microbiome and its impact on gastrointestinal atopy. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2016;71(9):1256–1263. doi: 10.1111/all.12943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Findings Distinguish Eosinophilic Esophagitis From Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7(12):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiremath GS, Hameed F, Pacheco A, Olive′ A, Davis CM, Shulman RJ. Esophageal Food Impaction and Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Retrospective Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2015;60(11):3181–3193. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3723-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang JW, Olson S, Kim JY, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2020;32(12):1–4. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1230–1236.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warners MJ, Van Rhijn BD, Verheij J, Smout AJPM, Bredenoord AJ. Disease activity in eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with impaired esophageal barrier integrity. American Journal of Physiology - Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2017;313(3):G230–G238. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00058.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: Validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62(4):489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108(5):679–692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Distribution and variability of esophageal eosinophilia in patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Modern Pathology. 2015;28(3):383–390. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky M, et al. Symptoms Have Modest Accuracy in Detecting Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):581–590.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Alexander JA, et al. Accuracy and Safety of the Cytosponge for Assessing Histologic Activity in Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Two-Center Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112(10):1538–1544. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackerman SJ, Kagalwalla AF, Hirano I, et al. One-Hour Esophageal String Test: A Nonendoscopic Minimally Invasive Test That Accurately Detects Disease Activity in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2019;114(10):1614–1625. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen N, Lavery WJ, Capocelli KE, et al. Transnasal Endoscopy in Unsedated Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis Using Virtual Reality Video Goggles. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;17(12):2455–2462. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen T, Rothenberg ME. Clinical applications of the eosinophilic esophagitis diagnostic panel. Frontiers in Medicine. 2017;4(JUL). doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoda T, Wen T, Aceves SS, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis endotype classification by molecular, clinical, and histopathological analyses: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018;3(7):477–488. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30096-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menard-Katcher C, Benitez AJ, Pan Z, et al. Influence of Age and Eosinophilic Esophagitis on Esophageal Distensibility in a Pediatric Cohort. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112(9):1466–1473. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan M, Aceves S, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal Compliance Quantifies Epithelial Remodeling in Pediatric Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2019;68(4):559–565. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlson DA, Lin Z, Hirano I, Gonsalves N, Zalewski A, Pandolfino JE. Evaluation of esophageal distensibility in eosinophilic esophagitis: an update and comparison of functional lumen imaging probe analytic methods. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 2016;28(12):1844–1853. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicodème F, Hirano I, Chen J, et al. Esophageal Distensibility as a Measure of Disease Severity in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;11(9):1101–1107.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang JW, Rubenstein JH, Mellinger JL, et al. Motivations, Barriers, and Outcomes of Patient-Reported Shared Decision Making in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. Published online 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06438-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Furuta GT, et al. Technical Review on the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Report From the AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1789–1810.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, et al. AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1776–1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; Food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1451–1459.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doerfler B, Bryce P, Hirano I, Gonsalves N. Practical approach to implementing dietary therapy in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis: The Chicago experience. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2015;28(1):42–58. doi: 10.1111/dote.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molina-Infante J, Bredenoord AJ, Cheng E, et al. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia: An entity challenging current diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2016;65(3):521–531. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen T, Dellon ES, Moawad FJ, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, Rothenberg ME. Transcriptome analysis of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia reveals proton pump inhibitor-reversible allergic inflammation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2015;135(1):187–197.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics do Not Reliably Differentiate PPI-Responsive Esophageal Eosinophilia and Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients Undergoing Upper Endoscopy: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(12):1854–1860. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng E, Zhang X, Huo X, et al. Omeprazole blocks eotaxin-3 expression by oesophageal squamous cells from patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis and GORD. Gut. 2013;62(6):824–832. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng E, Zhang X, Wilson KS, et al. JAK-STAT6 pathway inhibitors block eotaxin-3 secretion by epithelial cells and fibroblasts from esophageal eosinophilia patients: Promising agents to improve inflammation and prevent fibrosis in EOE. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, Molina-Infante J. Efficacy of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs for Inducing Clinical and Histologic Remission in Patients With Symptomatic Esophageal Eosinophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016;14(1):13–22.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molina-Infante J, Bredenoord AJ, Cheng E, et al. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia: An entity challenging current diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2016;65(3):521–531. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Guagnozzi D, et al. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic oesophagitis in 630 patients: results from the EoE connect registry. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2020;52(5):798–807. doi: 10.1111/apt.15957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaezi MF, Yang YX, Howden CW. Complications of Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):35–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706–715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors Based on a Large, Multi-Year, Randomized Trial of Patients Receiving Rivaroxaban or Aspirin. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682–691.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A, et al. Efficacy of Budesonide vs Fluticasone for Initial Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):65–73.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, et al. Efficacy of Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets as Induction Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):74–86.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philpott H, Dougherty MK, Reed CC, et al. Systematic review: adrenal insufficiency secondary to swallowed topical corticosteroids in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2018;47(8):1071–1078. doi: 10.1111/apt.14573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Published online April 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moawad FJ, Molina-Infante J, Lucendo AJ, Cantrell SE, Tmanova L, Douglas KM. Systematic review with meta-analysis: endoscopic dilation is highly effective and safe in children and adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2017;46(2):96–105. doi: 10.1111/apt.14123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dougherty M, Runge TM, Eluri S, Dellon ES. Esophageal dilation with either bougie or balloon technique as a treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2017;86(4):581–591.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: Effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(5):1062–1070. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Runge TM, Eluri S, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Control of inflammation decreases the need for subsequent esophageal dilation in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2017;30(7). doi: 10.1093/dote/dox042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Straumann A, Katzka DA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):346–359. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and Challenges to Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):840–851. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reed CC, Tappata M, Eluri S, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Combination Therapy With Elimination Diet and Corticosteroids Is Effective for Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019;17(13):2800–2802. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SLW, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2014;79(4). doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A, et al. Rapid Recurrence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity After Successful Treatment in the Observation Phase of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2020;18(7):1483–1492.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greuter T, Bussmann C, Safroneeva E, et al. Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis with Swallowed Topical Corticosteroids: Development and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Concept. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112(10):1527–1535. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Long-Term Budesonide Maintenance Treatment Is Partially Effective for Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;9(5):400–409.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Straumann A, Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, et al. Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets Maintain Remission in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1672–1685.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katzka DA & Kahrilas PJ Advances in the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMJ 371, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]