Abstract

Objectives

The Standardized Letter of Evaluation (SLOE) is a vital portion of any medical student’s emergency medicine (EM) residency application. Prior literature suggests gender bias in EM SLOE comparative ranking, but there is limited understanding of the impact of gender on other SLOE components. The study objective was to evaluate the presence of gender differences in the 7 Qualifications for EM (7QEM), Global Assessment (GA), and anticipated Rank List (RL) position. A secondary objective was to evaluate the gender differences in 7QEM scores and their link to GA and anticipated RL position.

Methods

We performed a cross‐sectional study using SLOEs from a subset of United States applicants to three EM residency programs during the 2019–2020 application cycle. We collected self‐reported demographics, 7QEM scores, GA, and anticipated RL position. We utilized linear regression analyses and repeated measures ANOVA to evaluate if the relationship between the 7QEM scores, GA score, and anticipated RL position was different for men and women.

Results

2103 unique applicants were included (38.6% women, 61.4% men), with 4952 SLOEs meeting inclusion criteria. The average QEM (2.51 vs. 2.39; p < 0.001), GA (2.68 vs. 2.48; p < 0.001), and RL (2.68 vs. 2.47; p < 0.001) scores were statistically higher for women than men. When exploring the relationship between the 7QEM and GA, Ability to communicate a caring nature to patients was not found to be a statistically significant predictor for men, but it was for women. When exploring the relationship between 7QEM and RL, Commitment to EM was not a significant predictor for men, but it was for women.

Conclusions

Women scored higher than men on the 7QEM, GA, and anticipated RL position on SLOEs. The 7QEM scores factored differently for men and women.

Keywords: gender, gender bias, letters of recommendation, Standardized Letter of Evaluation (SLOE)

INTRODUCTION

The Standardized Letter of Evaluation (SLOE) is a vital portion of emergency medicine–bound medical students’ residency application packet. Emergency medicine (EM) programs place a high value on SLOEs, 1 with a greater emphasis on SLOEs and grades from external institutions compared with students’ home institutions. 2

Gender bias has been demonstrated to exist in letters of recommendation (LOR) across medical specialties. Linguistic differences have been shown among LORs written for men and women applying into urology, 3 general surgery, 4 transplant surgery, 5 and ophthalmology. 6 Previous literature suggests SLOE narratives reinforce prior research that LOR for women applicants highlight communal characteristics of teamwork, helpfulness, and compassion. 7 , 8 Outside of linguistics, women applicants obtain somewhat better performance on rank list (RL) position within the EM SLOE. 9 While one prior study has evaluated RL, this was limited to a single institution with a small study population and did not examine the Global Assessment (GA) or the 7 Qualifications for EM (7QEM) questions. 9 Moreover, data suggest that the 7QEM may differ from grades alone, emphasizing a potential unique role for these components of the SLOE. 10 As the Step 1 examination transitions to pass/fail, there may be an increased emphasis on SLOE in applicant selection process, prompting a need to better assess for potential bias in this tool.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the presence of gender‐based differences in SLOEs on the 7QEM scores, GA, and anticipated RL position. A secondary objective was to evaluate the gender differences in individual 7QEM item scores and their link to GA and anticipated RL position.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a multi‐institution, cross‐sectional study of SLOEs from applicants to three United States (US) EM residency programs (Rush University, Stanford University, University of Florida College of Medicine‐Jacksonville) during the 2019–2020 application cycle. The study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at all three institutions.

Study population

All applicants from US Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME) Doctor of Medicine (MD) and Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation (COCA) Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) granting schools who applied to at least one of the three institutions’ EM residency programs were included in the study. To manage applications with multiple SLOEs, scores were averaged to create one record. The participating institutions were selected to represent diversity in program types, lengths, and location. Rush University is a 3‐year academic EM program in Illinois, Stanford University is a 4‐year academic EM program in California, and University of Florida College of Medicine‐ Jacksonville is a 3‐year county EM program in Florida.

Study protocol

Applicant exclusion criteria consisted of applicants from non‐LCME MD or non‐COCA DO institutions, applicants without a SLOE, and applicants who did not self‐report their gender. SLOE exclusion criteria consisted of subspecialty SLOEs, SLOEs with incomplete data, SLOEs not written by program leadership (defined as a program director, assistant or associate program director, clerkship director, vice‐chair, or chair), and SLOEs written by a letter writer who wrote <10 SLOEs the previous year.

Measures

Trained abstractors from each institution collected data using a prepiloted standardized data abstraction tool. The abstractors recorded the following data: Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) identification number, applicant self‐identified gender, and the ranking for all 7QEM scores, GA, and anticipated RL position. We recorded the AAMC ID number to avoid duplicate entries from multiple institutions; otherwise, the data were deidentified.

The 7QEM questions were each scored on a point scale. The first five questions were scored from “Below peers” (1), “At level of peers” (2), and “above peers” (3). Question 6 was scored from “More than peers” (1), at “Same as peers: (2), and “Less than peers” (3). Question 7 was scored from “Good” (1), “Excellent” (2), and “Outstanding” (3). GA was indicated on a 4‐point scale, where a 1 placed the candidate in the “Lower 1/3” and a 4 placed them in the “Top 10%.” Anticipated RL position was also indicated on a 5‐point scale with 0 representing “Unlikely to be on our rank list” and a 4 representing the “Top 10%.” As each applicant included in this study had a single averaged score for each of the measures, we treated the data as continuous.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were performed to evaluate the following questions: (1) Are the SLOEs 7QEM, RL, and GA scores different for men and women applicants? (2) Is the relationship between the 7QEM scores and the GA score different for men and women? (3) Is the relationship between the 7QEM scores and the anticipated RL position different for men compared to women?

A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyzed the 7QEM scores, with one independent variable of gender, to determine if scores differed between genders. The GA scores and anticipated RL position scores were submitted to separate t‐tests, with gender as the independent variable. Data were recorded and coded using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, 2018). All statistics were computed using IBM SPSS Version 26 (IBM Corp).

RESULTS

A total of 5668 SLOEs were reviewed, with 4952 meeting inclusion criteria. A total of 716 letters were excluded, consisting of 60 subspecialty SLOE, 118 SLOE with incomplete data, 157 SLOE not written by program leadership, and 425 SLOE written by a letter writer who wrote <10 SLOEs the previous year. Forty‐four letters were excluded due to meeting multiple exclusion criteria. Of the 4952 SLOEs included, 3050 (61.6%) were from men applicants and 1902 (38.4%) from women applicants. After meeting inclusion criteria, men had an average of 2.36 SLOEs and women had an average of 2.34 SLOEs.

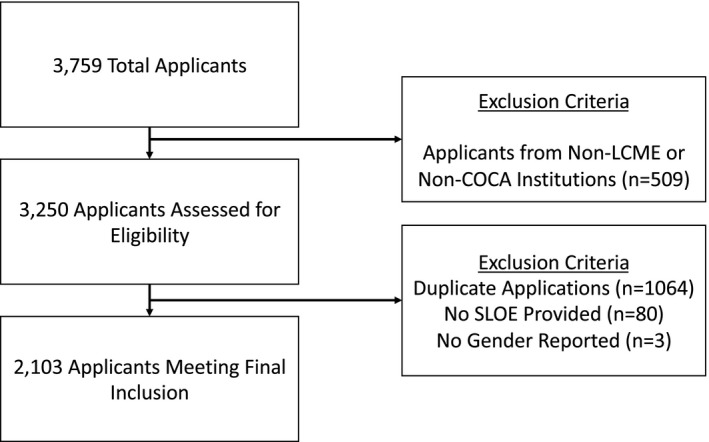

A total of 2103 unique applicants met all inclusion criteria for the study as described in Figure 1. This represented 61.8% (2103/3405) of all EM applicants for the 2019–2020 application cycle. 11 Of the 2103 applicants, 1290 (61.3%) identified as men and 813 (38.7%) identified as women. Our sample gender distribution is similar to the proportion of men (62.7%, 2678/4269) and women (37.3% 1591/4269) applicants (US and non‐US) during the 2019–2020 application cycle. 11 The average 7QEM (2.51 vs. 2.39; p < 0.001), GA (2.68 vs. 2.48; p < 0.001), and RL (2.68 vs. 2.47; p < 0.001) scores were statistically higher for women than men. Table 1 displays the mean scores for each QEM for men and women. Effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (η 2).

FIGURE 1.

Applicant inclusion and exclusion criteria

TABLE 1.

Multiple linear regression analysis of qualifications for EM question as a predictor of global assessment and rank list

| 7 Qualifications for EM (7QEM) | Candidate cohort mean out of 3 Institutions (SD) | Regression model for global assessment (GA) | Regression model for rank list (RL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Standardized beta coefficient (t‐test, 95% CI, p value) | Standardized beta coefficient (t‐test, 95% CI, p value) | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| Commitment to Emergency Medicine | 2.45 (0.42) | 2.52 (0.40) | 0.06 (3.32, 0.04–0.16, p < 0.001) | 0.08 (3.47, 0.06–0.21, p < 0.001) | 0.04 (2.01, 0.0–0.14, p = 0.05) | 0.05 (2.07, 0.0–0.16, p = 0.04) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.01 | ||||||

| Work ethic, willingness to assume responsibility | 2.60 (0.42) | 2.71 (0.37) | 0.11 (5.35, 0.11–0.25, p < 0.001) | 0.07 (2.37, 0.02–0.22, p < 0.02) | 0.10 (4.67, 0.10–0.25, p < 0.001) | 0.11 (3.97, 0.11–0.32, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02 | ||||||

| Ability to develop and justify an appropriate differential and a cohesive treatment plan | 2.24 (0.49) | 2.35 (0.45) | 0.26 (11.4, 0.30‐0.42, p < 0.001) | 0.28 (9.59, 0.33–0.50, p < 0.001) | 0.18 (7.62, 0.20–0.34, p < 0.001) | 0.19 (6.71, 0.21–0.38, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.01 | ||||||

| Ability to work with a team | 2.51 (0.43) | 2.64 (0.39) | 0.10 (4.68, 0.10–0.23, p < 0.001) | 0.08 (2.74, 0.04–0.23, p < 0.01) | 0.16 (6.93, 0.19–0.35, p < 0.001) | 0.11 (3.86, 0.1–0.3, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02 | ||||||

| Ability to communicate a caring nature to patients | 2.46 (0.41) | 2.64 (0.38) | 0.03 (1.67, 0.0–0.12, p = 0.1) | 0.09 (3.35, 0.06–0.24, p = 0.001) | 0.06 (2.97, 0.04–0.18, p < 0.01) | 0.1 (3.97, 0.1–0.28, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.04 | ||||||

| How much guidance do you predict this applicant will need during residency? | 2.20 (0.49) | 2.29 (0.47) | 0.27 (10.39, 0.30–0.44, p < 0.001) | 0.17 (5.10, 0.15–0.33, p < 0.001) | 0.26 (9.57, 0.31–0.47, p < 0.001) | 0.21 (6.49, 0.22–0.41, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.01 | ||||||

| Given the necessary guidance, what is your prediction of success for the applicants? | 2.28 (0.51) | 2.42 (0.46) | 0.19 (7.53, 0.19–0.32, p < 0.001) | 0.27 (7.89, 0.30–0.49, p < 0.001) | 0.21 (8.08, 0.23–0.38, p < 0.001) | 0.26 (7.89, 0.31–0.51, p < 0.001) |

| p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.02 | ||||||

A linear regression analysis evaluates the amount of variance in the dependent variable that can be explained by the other variables in the model. This variability, expressed as the adjusted R 2, was 72.4%, indicating that the 7QEM scores predicted significant variance in the GA score (p < 0.001). When exploring the relationship between the 7QEM and GA, Ability to communicate a caring nature to patients was not a significant predictor for men, but it was for women. Additionally, the score for How much guidance is needed during residency was weighted higher for men (0.27) compared to women (0.17). The analysis includes standardized beta coefficients, which describes the strength of the relationship between a single independent variable and a dependent variable. The t‐tests and accompanying p values evaluate the statistical significance of these relationships. These values are presented in Table 1.

The adjusted R 2 value indicated 71.4% of the variance in the anticipated RL position could be reliably predicted by the 7QEM scores (p < 0.001). When exploring the relationship between the 7QEM and RL, Commitment to EM was not a significant predictor for men, but it was for women (p = 0.05). Additionally, the score for Predictions of success was weighted higher for women (0.27) compared to men (0.19). The standardized beta coefficients, t‐test and p‐values modeling the relationship between 7QEM scores and the anticipated RL position, are presented in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Our study evaluated the correlation between gender and SLOE 7QEM questions, GA, and anticipated RL scores. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically assess for a link between gender and multiple components of scoring for SLOEs. When examining all of the 7QEM questions, GA, and anticipated RL, overall scores for women were higher than men. Given the importance placed on the SLOE by Program Directors, it is vital for us to understand bias that may exist in the SLOEs. 2 Our data could be interpreted as bias towards women applicants, as they are consistently rated higher than their male counterparts. While women make up only 38.7% of our study population, they consistently scored higher than their majority male counterparts. This may be reflective of the phenomena described in a Hewlett Packard internal report. This report found that women only apply for jobs when meeting 100% of the requirements, while men apply when meeting only 60% of the qualifications. 12 Women applicants may meet more of the requirements for EM training over their men counterparts prior to applying to EM. No matter the reason, EM program leadership should be aware that female applicants consistently receive higher scores for 7QEM questions, GA, and anticipated RL.

When evaluating factors contributing to GA, our data suggest that the 7QEM questions factor differently for men and women. The Ability to Communicate a Caring Nature to Patients is less of a predictor for GA for men compared to women. Thus, our data could suggest men were less penalized for not demonstrating a caring nature to patients. On the other hand, this could suggest that communicating in a caring nature to patients is more important for women to display during their EM rotation and contributes to their GA. Alternatively, this could suggest showing a caring nature may help women, but men have no opportunity to benefit in regard to GA from displaying a caring nature during their EM rotation. Previous studies have specifically cited the word ‘caring’ as more frequently associated with women applicants than men applicants in Medical Student Performance Evaluations of medical students applying to residency. 13 , 14 Implicit bias invoked by the word ‘caring’ may explain why evaluators rate this qualification differently for women than men.

When evaluating factors contributing to anticipated RL position, our data suggest that the 7QEM questions factor differently for men and women. Commitment to EM is less of a predictor for anticipated RL position for men compared to women. Our data suggest men are less penalized for not displaying commitment to the specialty. This could also suggest that commitment to EM is more important for women to display during their medical school career and contributes to their anticipated RL position. Alternatively, this could suggest showing a commitment to EM may help women, but men have no opportunity to benefit in regard to RL position from displaying a commitment during their medical training. EM may be considered a more agentic or masculine specialty. Women may have to work harder to prove both commitment and fit to EM; however, when they do, they may be ranked more highly. In our study, this may explain why Commitment to EM is more of a predictor for anticipated RL positions for women, as women may have to demonstrate more commitment than their men counterparts.

Overall, we found that the 7QEM questions contributed to the GA and anticipated RL position differently for men and women. This is consistent with previous literature that women trainees are evaluated differently than men in both quantitative (check boxes) and qualitative (narrative) components of letters of recommendation. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 15 , 16 Our results demonstrate that men do not need to score as high on How much guidance is needed during residency, compared to women, when being assessed on the GA (i.e., men can get away with needing more guidance). Conversely, women do not need to score as high on predictions of success (questions 6 and 7), compared to men, when being assessed on RL (i.e., women are less expected to succeed given the necessary guidance). Future projects could evaluate gender bias over a multiyear period. These projects should seek to better understand the underlying reason for such differences, possibly through linguistic analysis. Finally, studies should evaluate race/ethnicity and medical degree (MD, DO) differences in predictors of GA and anticipated RL position on SLOEs.

LIMITATIONS

It is important to consider several limitations with respect to this study. First, gender is nonbinary and self‐determined. We defined gender given the self‐reported data on the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application form. ERAS only allows for binary gender definition or ‘no‐answer,” limiting the ability for applicants to report their true gender identity. All applicants who reported “no answer” were not included in our analysis, which may have impacted our study sample. We also excluded SLOEs written by authors who had written <10 SLOEs in the prior year and those written for subspecialty rotations, limiting the ability to assess this specific group. We converted the GA and RL to a four‐point and five‐point scale. While this was consistent with prior research, the differences in percentages are not even across groups. 10 Additionally, our study was conducted during the 2019–2020 application year and does not reflect other application years, particularly the impact of COVID‐19 in the subsequent academic years. While this study captured two‐thirds of all US EM applicants, it is limited to those applied to the included programs and may not reflect all EM applicant SLOEs. This study is also subject to the limitations of cross‐sectional research, such that it can only demonstrate an association and is not able to prove causation. Finally, we identified a statistically significant difference in several areas, but it is unclear if this would be of practical significance. As we were unable to evaluate the applicants’ final rank list position among the programs, further studies should assess the impact of this on ultimate rank list position.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there are gender differences in the overall scores of the 7QEM questions and in the predictors of GA and anticipated RL position on SLOEs. Studies show the significance of the SLOE in EM resident selection. 2 Thus, it is imperative to analyze each section of the SLOE for potential bias as a means to create a more equitable evaluation and selection process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank the entire Diversity Inclusion Research and Education Collaboration Team (DIRECT).

Mannix A, Monteiro S, Miller D, et al. Gender differences in emergency medicine standardized letters of evaluation. AEM Educ Train. 2022;6:e10740. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10740

Prior Presentations: All authors report no prior presentations

REFERENCES

- 1. Love JN, Smith J, Weizberg M, et al. Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors’ standardized letter of recommendation: the program director's perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):680‐687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Negaard M, Assimacopoulos E, Harland K, Van Heukelom J. Emergency medicine residency selection criteria: an update and comparison. AEM Educ Train. 2018;2(2):146‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Filippou P, Mahajan S, Deal A, et al. The presence of gender bias in letters of recommendations written for urology residency applicants. Urology. 2019;134:56‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turrentine FE, Dreisbach CN, St Ivany AR, Hanks JB, Schroen AT. Influence of gender on surgical residency applicants’ recommendation letters. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(4):356‐65.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffman A, Grant W, McCormick M, Jezewski E, Matemavi P, Langnas A. Gendered differences in letters of recommendation for transplant surgery fellowship applicants. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):427‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lin F, Oh SK, Gordon LK, Pineles SL, Rosenberg JB, Tsui I. Gender‐based differences in letters of recommendation written for ophthalmology residency applicants. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li S, Fant AL, McCarthy DM, Miller D, Craig J, Kontrick A. Gender differences in language of standardized letter of evaluation narratives for emergency medicine residency applicants. AEM Educ Train. 2017;1(4):334‐339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller DT, McCarthy DM, Fant AL, Li‐Sauerwine S, Ali A, Kontrick AV. The standardized letter of evaluation narrative: differences in language use by gender. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(6):948‐956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andrusaitis J, Clark C, Saadat S, et al. Does applicant gender have an effect on standardized letters of evaluation obtained during medical student emergency medicine rotations? AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(1):18‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller DT, Krzyzaniak S, Mannix A, et al. The standardized letter of evaluation in emergency medicine: Are the qualifications useful? AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(3):e10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ERAS Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data‐reports/interactive‐data/eras‐statistics‐data

- 12. Mohr TS Why women don’t apply for jobs unless they’re 100% qualified. Harvard Business Review [Internet] 2014 [cited 2021 Dec 13].

- 13. Madera JM, Hebl MR, Martin RC. Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: agentic and communal differences. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(6):1591‐1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez‐Smith M, Jordan A, Chekroud A, Moore EZ. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in Medical Student Performance Evaluations. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grimm LJ, Redmond RA, Campbell JC, Rosette AS. Gender and racial bias in radiology residency letters of recommendation. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17(1 Pt A):64‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Powers A, Gerull KM, Rothman R, Klein SA, Wright RW, Dy CJ. Race‐ and gender‐based differences in descriptions of applicants in the letters of recommendation for orthopaedic surgery residency [Internet]. JBJS Open Access. 2020;5(3):e20.00023. 10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]