Abstract

The in vitro and in vivo effectiveness of amikacin, cefepime, and imipenem was studied using a high inoculum of an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. An in vitro susceptibility test at the standard inoculum predicted the in vivo outcome of amikacin or imipenem while it did not do so for cefepime due to the inoculum effect.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production is one of the main mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics among the strains of the family Enterobacteriaceae (14). The therapeutic choices in infections caused by such strains remain limited because of cross-resistance (4). Attempts have been made to compare the activities of β-lactams with β-lactamase inhibitors, showing inconsistent results (5, 20, 24, 27). Conflicting reports have been published concerning the activities of the broad-spectrum and “fourth generation” cephalosporins with an explanation of the inoculum effect (5, 15, 27).

Our aim was to compare the activities of amikacin, cefepime, amikacin plus cefepime, and imipenem in septic mice infected by an SHV-5 ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain using a high initial inoculum.

The SHV-5 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strain originated in a premature intensive-care unit (26). Amikacin and cefepime (Bristol-Myers Squibb), imipenem (Merck, Sharp & Dohme), and cisplatin (Ebewe) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. The MICs and the minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined by the microdilution method with inocula of 105 and 107 CFU/ml, respectively (20, 21). For the killing curve, the initial bacterial concentration was 8 log10 CFU/ml. The concentrations of antibiotics chosen were close to the in vivo mean levels in serum: amikacin, 4 μg/ml; cefepime, 40 μg/ml; amikacin plus cefepime in the same concentrations listed above; and imipenem, 16 μg/ml. Synergy was defined as a ≥2-log10 decrease in the number of CFU per milliliter between the combination and its most active constituent after 24 h (17).

Randomly selected male CD-1 mice (30 to 35 g) were used for the pharmacokinetic study, for the determination of blood bacterial counts, and for survival analysis. Each group contained 15 mice. Cisplatin (18 mg/kg of body weight as determined in a pilot study) had been administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection 3 days before infection in order to cause renal impairment (18). The mice were infected i.p. with 107 CFU/g; the uninfected group received only cisplatin. Three groups of uninfected mice were used for pharmacokinetic analysis, and they were followed up for 48 h (3, 6, 9, 10, 16, 19, 28). Single doses of amikacin (7.5 mg/kg), cefepime (80 mg/kg), and imipenem (40 mg/kg) were administered i.p. Blood samples were taken 15 and 30 min and 1, 2, and 3 h after drug administration. Antibiotic levels in sera were determined by a paper disk method for imipenem and cefepime with Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, respectively, as indicator organisms on antibiotic medium 1 (Becton Dickinson) (1). The amikacin serum levels were detected by the fluorescence polarization immunoassay (Abbott TDx system) (30). The lower limits of detection were 0.05 μg/ml for amikacin, 8 μg/ml for cefepime, and 1 μg/ml for imipenem. The coefficient of variability was ≤5% for each antibiotic assay. The pharmacokinetic values half-life (T1/2), peak concentration (Cmax), first occurrence of Cmax (Tmax), area under the concentration-time curve extrapolated to infinity (AUC), and area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) were calculated by a noncompartmental method (2).

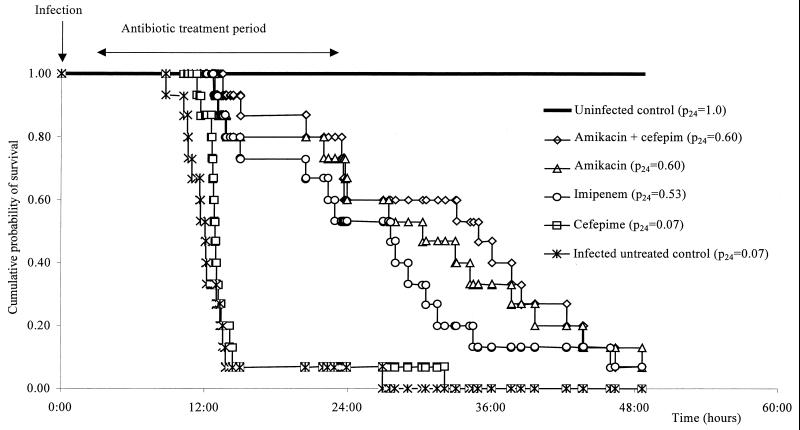

Four infected treated groups and one infected untreated group were used for the determination of blood bacterial counts. The treatment started 3 h after infection and lasted for 24 h. Two doses of amikacin (7.5 mg/kg every 10.5 h), three doses of cefepime (80 mg/kg every 7 h), the same doses of amikacin plus cefepime as in monotherapy, or four doses of imipenem (40 mg/kg every 5.25 h) were given i.p. Blood samples were taken 3 and 9 h after the beginning of antibiotic therapy. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U test were used for statistical analysis, taking a P value of <0.05 as significant. Four infected treated groups and two control groups (uninfected treated and infected untreated) were used for the survival analysis after up to 48 h, with death as the end point. Survival was assessed at 24 and 48 h for calculating lethality, and 24-h survival was assessed by estimating the cumulative probability using the Kaplan-Meier survival curve. The relative risk between groups was estimated by the hazard ratio with the appropriate 95% confidence interval comparing the observed deaths with expected deaths. The log rank test was used for statistical analysis, accepting a P value of <0.05 as significant.

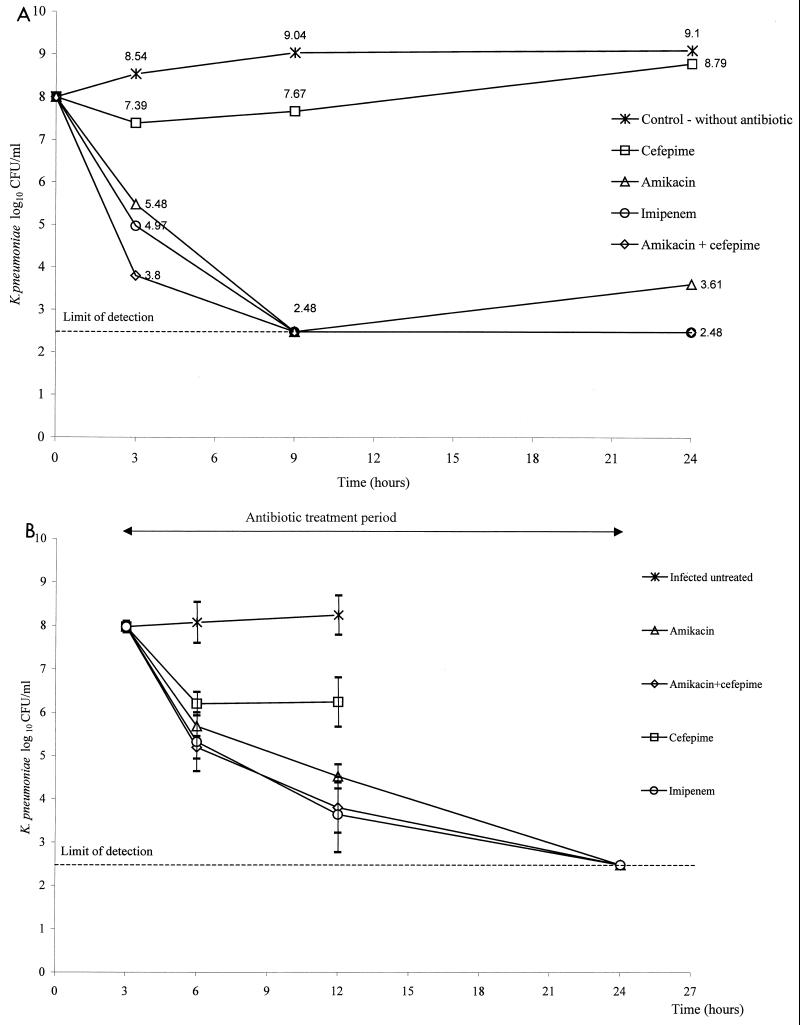

The MIC and MBC of amikacin were 0.5 μg/ml at both 105 and 107 CFU/ml. The MIC and MBC of cefepime were 1 μg/ml at 105 CFU/ml, and the MIC was >256 μg/ml at 107 CFU/ml. The MIC and MBC of imipenem were 0.125 μg/ml at 105 CFU/ml, and the MIC and MBC were 0.5 and 1 μg/ml at 107 CFU/ml, respectively. The killing curve study is shown in Fig. 1A. Synergy was not detected due to the limits of detection of bacterial counts.

FIG. 1.

(A) Killing curves of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae incubated without antibiotic, with cefepime, with amikacin, with imipenem, and with amikacin plus cefepime. (B) Mean bacterial counts observed in untreated mice and in those receiving amikacin, amikacin plus cefepime, cefepime, and imipenem after infection with ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The difference was significant when all groups were compared (P < 0.0001) and between the infected untreated group and all treated groups (P < 0.01 in each pair compared). The cefepime-treated group differed statistically from the other treated groups (P < 0.05 in each pair compared). There was no difference between groups receiving amikacin, amikacin plus cefepime, and imipenem (P > 0.37 in each pair compared).

Data from the pharmacokinetic analysis are given in Table 1, except for amikacin plus cefepime because they do not affect the elimination of each other (2).

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of antibiotics following an i.p. injection in noninfected mice with impaired renal functiona

| Antibiotic (dose) | T1/2 (h) | Cmax (μg/ml) | Tmax (min) | AUC (μg · h/ml) |

T > MIC (h/%)

|

AUC0–24 MIC (h)

|

Cmax/MICbc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 105b | 107c | 105b | 107c | ||||||

| Amikacin (7.5 mg/kg) | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 20.18 ± 4.30 | 15 | 35.34 ± 4.90 | 4.81 ± 0.95/46.00 ± 9.05 | 4.81 ± 0.95/46.00 ± 9.05 | 161.54 ± 22.40 | 161.54 ± 22.40 | 40.36 ± 8.60 |

| Cefepime (80 mg/kg) | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 195.00 ± 45.00 | 15 | 260.97 ± 12.67 | 7.40 ± 0.36/105.72 ± 5.20 | —d | 894.75 ± 43.44 | NCe | NC |

| Imipenem (40 mg/kg) | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 45.00 ± 3.00 | 30 | 47.83 ± 2.63 | 4.31 ± 0.24/82.09 ± 4.65 | 3.37 ± 0.18/64.19 ± 3.51 | 1,749.20 ± 96.18 | 437.30 ± 24.04 | NC |

All figures except Tmax are means ± standard deviations.

MIC at 105 CFU/ml.

MIC at 107 CFU/ml.

C max did not reach MIC.

NC, not calculated.

The blood bacterial count increased persistently in the untreated group; cefepime initially decreased it, but an increase occurred after 6 h, while it decreased persistently in the other treated groups (Fig. 1B).

There were no deaths in the uninfected group. After 24 h, the lethality was 14 of 15 in the infected untreated and cefepime-treated groups, 6 of 15 in the amikacin- and amikacin-plus-cefepime-treated groups, and 7 of 15 in the imipenem-treated group (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Survival curve of mice treated with amikacin, cefepime, cefepime plus amikacin, and imipenem and previously infected with ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. The hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) were as follows: infected, untreated group versus uninfected group, 26.47 (7.21 to 70.42), P< 0.001; cefepime versus infected untreated group, 0.65 (0.29 to 1.37), P > 0.2; amikacin versus infected untreated group, 0.17 (0.03 to 0.26), P < 0.001; amikacin plus cefepime versus infected untreated group, 0.16 (0.03 to 0.24), P < 0.001; imipenem versus infected untreated group, 0.19 (0.04 to 0.33), P < 0.001; amikacin versus cefepime, 0.18 (0.04 to 0.34), P < 0.001; amikacin plus cefepime versus cefepime, 0.16 (0.03 to 0.24), P < 0.001; imipenem versus cefepime, 0.21 (0.05 to 0.37), P < 0.001; amikacin plus cefepime versus amikacin, 0.98 (0.31 to 3.08), P > 0.2; amikacin plus cefepime versus imipenem, 0.71 (0.24 to 2.11), P > 0.2; amikacin versus imipenem, 0.77 (0.26 to 2.30), P > 0.2. p24, probability of survival at 24 h postinfection.

The in vitro susceptibilities of ESBL-producing strains to cefepime have been found to be 52 or 90% (15, 25). Cefepime was recommended for the treatment based on this in vitro susceptibility (12). Others did not recommend it, despite its in vivo effectiveness, arguing on the basis of the inoculum effect, dose dependence, and other factors (15, 27). In our study, we saw an inoculum effect for cefepime, and it was ineffective in vitro and in vivo with a high inoculum.

Carbapenems have been reported to be stable against ESBL enzymes and are considered to be the treatment of choice (14, 24). In our study, imipenem showed a slight inoculum dependence, but the organisms remained susceptible. It persistently decreased the in vitro and in vivo bacterial counts, and it was biologically effective in the survival analysis.

Amikacin has good in vitro activity against ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains (15, 22). In our study, it did not show an inoculum effect, which can be an advantage compared to β-lactams. Synergy between amikacin and cefepime was not detected in vitro, and the combination was not more effective in vivo than amikacin alone.

Overall, the observed biological differences could not be explained by the pharmacokinetics because they were appropriate for all antibiotics, taking into account the susceptibility at the standard inoculum (7, 8, 11, 13, 23, 29). The in vitro susceptibility test and the percentage of T greater than the MIC calculated with the standard inoculum were not predictive for the biological effectiveness of cefepime due to a possible in vivo inoculum effect.

Based on our results, imipenem or amikacin can be the therapy of choice against ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains showing susceptibility at the standard inoculum, while cefepime cannot be recommended even though the organisms show susceptibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mónika Kapás, Györgyné Sümeghy, and Ágoston Ghidán for their valuable technical help and David Stevens for proofreading.

This study was supported by the Hungarian National Scientific Research Fund, grant no. OTKA T021251 and OTKA T032473.

Footnotes

This study was part of the 10th accredited Ph.D. program at Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anhalt J P. Assays for antimicrobial agents in body fluids. In: Lennette E H, Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1985. pp. 1009–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbahaiya R H, Knupp C A, Pfeffer M, Pittman K A. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between cefepime and amikacin in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1382–1386. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botha F J, van der Bijl P, Seifart H I, Parkin D P. Fluctuation of the volume of distribution of amikacin and its effect on once-daily dosage and clearance in a seriously ill patient. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:443–446. doi: 10.1007/BF01712162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brun-Buisson C, Legrand P, Philippon A, Montravers F, Ansquer M, Duval J. Transferable enzymatic resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporins during nosocomial outbreak of multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lancet. 1987;ii:302–306. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron F, Gutmann L, Bure A, Pangon B, Vallois J M, Pechinot A, Carbon C. Ceftriaxone-sulbactam combination in rabbit endocarditis caused by a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-broad-spectrum TEM-3 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2070–2074. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig W A, Redington J, Ebert S C. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in mouse thigh and lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:S29–S40. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_c.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig W A. Interrelationship between pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in determining dosage regimens for broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(95)00053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig W A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–10. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinosotti S, Bamonte F, Leung P, Kramer W G, Ongini E. Aminoglycoside dosing regimen and pharmacokinetic parameters in the guinea pig. Chemotherapy. 1990;36:33–40. doi: 10.1159/000238746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drusano G L, Plaisance K I, Forrest A, Bustamante C, Devlin A, Standiford H C, Wade J C. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of imipenem in febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1420–1422. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.9.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantin B, Ebert S, Leggett J, Vogelman B, Craig W A. Factors affecting duration of in-vivo postantibiotic effect for aminoglycosides against Gram-negative bacilli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;27:829–836. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould I M. Do we need fourth-generation cephalosporins? Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:S1–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyatt J M, McKinnon P S, Zimmer G S, Schentag J J. The importance of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic surrogate markers to outcome. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:143–160. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. More extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1697–1704. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jett B D, Ritchie D J, Reichley R, Bailey T C, Sahm D F. In vitro activities of various β-lactam antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. resistant to oxyimino cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1187–1190. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovarik J M, ter Maaten J C, Rademaker C M, Deenstra M, Hoepelman I M, Hart H C, Matzke G R, Verhoef J. Pharmacokinetics of cefepime in patients with respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1885–1888. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krogstad D J, Moellering R C. Antimicrobial combinations. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Willkins Co.; 1986. pp. 537–595. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahmood I, Wasters D H. A comparative study of uranyl nitrate and cisplatin-induced renal failure in rat. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1994;19:327–336. doi: 10.1007/BF03188859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClure J T, Rosin E. Comparison of amikacin dosing regimens in neutropenic guinea pigs with Escherichia coli infection. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:750–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentec H, Vallois J, Bure A, Saleh-Mghir A, Jehl F, Carbon C. Piperacillin, tazobactam, and gentamicin alone or combined in an endocarditis model of infection by a TEM-3-producing strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae or its susceptible variant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1883–1889. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically. Document M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinn J P. Clinical strategies for serious infection: a North American perspective. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;31:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renneberg J, Walder M. Postantibiotic effects of imipenem, norfloxacin, and amikacin in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.10.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice L B, Carias L L, Shlaes D M. In vivo efficacies of β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations against a TEM-26-producing strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2663–2664. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silva J, Aguilar C, Estrada M A, Echaniz G, Carnalla N, Soto A, Lopez-Antuano F J. Susceptibility to new beta-lactams of enterobacterial extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producers and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Mexico. J Chemother. 1998;10:102–107. doi: 10.1179/joc.1998.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szabó D, Filetóth Z, Szentandrássy J, Némedi M, Tóth E, Jeney C, Kispál G, Rozgonyi F. Molecular epidemiology of a cluster of cases due to Klebsiella pneumoniae producing SHV-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in the premature intensive care unit of a Hungarian hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4167–4169. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4167-4169.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thauvin-Eliopoulos C, Tripodi M F, Moellering R C, Jr, Eliopoulos G M. Efficacies of piperacillin-tazobactam and cefepime in rats with experimental intra-abdominal abscesses due to an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1053–1057. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Dalen R, Vree T B. Pharmacokinetics of antibiotics in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 1990;16:S235–S238. doi: 10.1007/BF01709707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogelman B, Gudmundsson S, Leggett J, Turnidge J, Ebert S, Craig W A. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:831–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaninotto M, Secchiero S, Paleari C D, Burlina A. Performance of a fluorescence polarization immunoassay system evaluated by therapeutic monitoring of four drugs. Ther Drug Monit. 1992;14:301–305. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199208000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]