SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia exceeded tuberculosis (TB) mortality, contributing 1.8 million deaths in 2020.1 TB may remain undiagnosed due to confusion between the clinical features of the 2 diseases and the lack of a specific radiological lesion. Some evidences suggest that previous or current TB infection or disease is associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes as the same virus or immunomodulatory treatments could reactivate latent TB.

We describe a case of a 69 years old woman, non-smoker, Ecuadorian, with a healthy active lifestyle, with hypertension, type II diabetes and autoimmune type I pancreatitis (due to immunoglobulin G4 mediated disease). His baseline treatment consisted of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, metformin and prednisone (5 mg daily). Patient also had an untreated latent TB infection (LTBI).

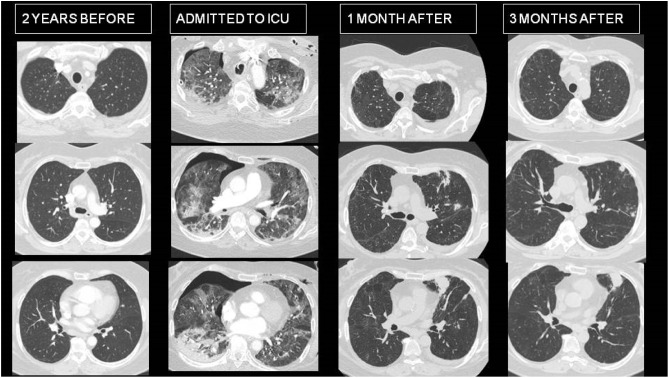

In March 2020, before the widespread use of COVID vaccines, she developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia with requirements of mechanical ventilation for 10 days. She received dexamethasone, tocilizumab and broad spectrum antibiotic coverage. She was discharged 22 days after ICU admission, cured of all complications suffered (urinary tract infection, bilateral pneumothorax, deep vein thrombosis) One month after discharge, she complained of persistent dyspnea mMRC II. Her lung function tests showed decreased DLCO (49%) with normal spirometry values. Also, her CT scan demonstrated nodular sharply defined masses in the upper left lobe (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Evolution of radiological lesions in CT, before, during and after SARSCOVID 2 bilateral pneumonia.

Patient received conservative treatment. Three months later a repeat CT demonstrated reduction of infiltrates with persistence of nodules. Finally, a CT guided biopsy was performed revealing extensive areas of necrosis and multiple epithelioid granulomas and a single positive Ziehl Neelsen bacillary structure. The diagnosis was confirmed with the growth of M. tuberculosis in 2 post-bronchoscopy sputums.

Tuberculosis and COVID-19 are airborne infectious diseases. They mainly affect the respiratory system and manifest a classic triad of symptoms: cough, fever and dyspnea. This initially makes differential diagnosis difficult, especially in countries with a high incidence of tuberculosis, which raises fears of an increase in diagnostic delay and treatment. There are a lot of concerns due to the possible interactions between SARS-COV-2 infection and M. tuberculosis.2 The convergence of the two diseases seems to indicate a pessimistic scenario: can SARS-CoV-2 infection reactivate TB? Is LTBI or active TB a risk factor for infection and progression to severe COVID-19 pneumonia? What impact does the coincidence of both diseases have on mortality?3

Our patient had LTBI, but any previous lesion suggestive of TB on CT. It is quite likely that COVID-19 pneumonia or treatment with immunosuppressive drugs or both, have favored the evolution of LTBI towards active disease. Long term treatment with corticosteroids are a well-established predisposing factor of TB.4 Nevertheless, there is not enough literature to determine if the use of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia can increase the risk of TB.5

This raises the need to assess and treat LTBI in patients with lung injuries secondary to COVID-19 susceptible to treatment with corticosteroids. For all the above, TB should be carefully evaluated in patient with COVID-19 pneumonia and therapeutic strategies should be adjusted accordingly to prevent the rapid development of active TB. However, there is still not enough evidence to understand the possible consequences of LTBI and the interactions between these major respiratory infectious killers.

Financiation

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021.

- 2.Comella-Del-Barrio P., De Souza-Galvão M.L., Prat-Aymerich C., Domínguez J. Impact of COVID-19 on tuberculosis control. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2020.11.016. Epub 2020 Dec 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tadolini M, Codecasa LR, García-García JM, Blanc FX, Borisov S, Alffenaar JW, et al. Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: first cohort of 49 cases. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001398. doi:10.1183/13993003.01398-2020. Print 2020 July. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Lai C.C., Lee M.T., Lee S.H., Lee S.H., Chang S.S., Lee C.C. Risk of incident active tuberculosis and use of corticosteroids. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:936–942. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0031. PMID: 26162360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell C., Andersson M.I., Ansari M.A., Moswela O., Misbah S.A., Klenerman P., et al. Risk of reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and tuberculosis (TB) and complications of hepatitis C virus (HCV) following tocilizumab therapy: a systematic review to inform risk assessment in the COVID-19 era. Front Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.706482. 706482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]