Abstract

Imaging is vital in characterising and delineating the extent of soft tissue tumours and there is abundant literature on this. A simplified approach is required to characterise the lesions on MR and we describe a simplified street-smart approach called SLAM (signal, location, age, multiplicity and matrix).

Keywords: Soft tissue tumour, SLAM, Approach

1. MRI imaging of soft tissues tumours and tumour like lesions-SLAM approach

Soft tissue tumour and tumour like conditions are common abnormalities encountered in day-to-day practice and sometimes could be complex to diagnose. WHO classification of the soft tissue lesions is based on histopathology and arriving at diagnosis only based on imaging is often difficult. However, imaging is vital in characterising the lesion and delineating the extent of the lesion. As a result, the approach to soft tissue lesions is generally multidisciplinary. There is abundant literature available about imaging appearances of various soft tissue lesions; however, there is a need for a simplified approach to characterise the lesion bases on their MRI characteristics. This paper describes a simplified street-smart approach to soft tissue tumours and tumor like conditions using abbreviation SLAM, where S stands for signal intensity and signs, L -location, A -age group, M -multiplicity and matrix (Table 1).

Table 1.

SLAM.

| S: Signal Pattern |

| Signs |

| L: Localisation Clues |

| A: Age clues |

| M: Multiplicity |

| Matrix Mix Mantras |

2. MRI technique is soft tissue lesions

Acquisition of the MRI should ideally begin with placing a skin marker at the lesion site, which is useful in identifying the location of the lesion, particularly when the soft tissue lesion is small in size. Type of coil used depends on the location and size of the lesion. Surface coils are preferred wherever possible due to better signal to noise ratio. A body coil and wider field of view may be useful If the lesion is large. Axial plains are preferred primary plains and provide valuable information about location, the lesion's extent, and its relation with surrounding structures. Based on the lesion's orientation and its location, coronal or sagittal plains can be chosen to demonstrate the full extent of the lesion and its relationship with surrounding structures. T1 and T2 sequences are the primary sequences performed to assess the signal characteristics of the lesion. T1 sequences are useful to identify the presence of fat or haemorrhage within the lesion. Fluid sensitive sequences are routinely performed, and they make the lesion more conspicuous and help identify oedema and inflammatory changes around the lesion. Special sequences such as gradient echo/T2∗ sequences although not used routinely, however may be performed to identify hemosiderin deposits calcification or metallic component within the lesion if needed.

In some cases, contrast administration can help differentiate a cystic lesion from a solid lesion, (particularly cyst from a myxoid lesions), to identify a solid nodule in a cystic lesion also to delineate the margins of the lesion and its extent. However, many soft tissue lesions can be well evaluated without a need for intravenous contrast administration, and routine use of contrast is unnecessary. We prefer selective use of contrast in evaluating soft tissue lesions.

3. Signal intensity

On MRI, lesions are assessed based on their signal intensity characteristics. Signal intensities of soft tissue lesions are compared with skeletal muscles on T1 and T2 and lesions which demonstrate signal intensities higher than the skeletal muscles are considered as hyperintense and those which show relatively low signal to skeletal muscles are considered hypointense.1 Signal intensities of lesion on MRI depend on their internal contents and can characterise the lesions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Signal intensity (SLAM).

|

| Lipomatous lesions |

| Clear cell sarcoma |

|

| Subacute haematoma |

| Haemangioma |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma |

|

| Myxoma |

| Ganglion cyst |

|

| Desmoids |

| PVNS localised |

| Giant cell reparative granuloma |

| Myositis Ossificans |

3.1. T1 and T2 hyperintense lesions

This group represents lesions containing fat, haemorrhagic content and melanin. Some lesions with haemorrhaging contents may also fall in this group.

-

a)

Lipomatous lesions:

Lipomatous lesions are the most common soft tissue lesions, composed of adipose tissue. Because of the internal fat content, they appear hyperintense on T1 and T2 WI and demonstrate suppression of the signal on fat saturated images. WHO has classified lipomatous lesions in to benign, intermediate and malignant. The lipoma is the most commonly encountered benign lesion accounting for approximately half of the soft tissue lesions seen in the clinical practice. Lipomas, when located superficial to the deep fascia, are called superficial lipomas.2 Deep lipomas are seen deep to superficial fascia and can be intramuscular, intermuscular, intraarticular and can involve the tendons. Lipomas are composed of mature adipocyte. Benign lipomas demonstrate homogenous appearance on MRI with no or subtle septations which are less than 2 mm in thickness and no non-lipomatous components or nodules (Fig. 1). It is to be noted that up to 1/3 of benign lipomas may demonstrate non-adipose components within secondary to fat necrosis, calcification or angiomatous components.2, 3, 4 Specific variants of lipomas, such as chondroid lipomas and pleomorphic lipomas, routinely demonstrate non-lipomatous contents.2 Deep lipomas, especially intramuscular lipomas, often demonstrate striated or septate appearance, particularly around the edges due to traversing muscle fibres which should not be mistaken for septations.5

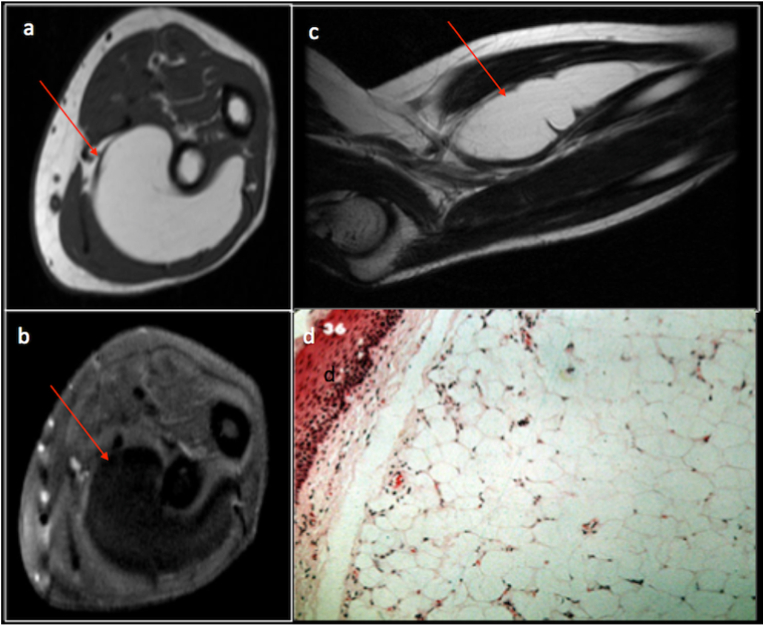

Fig. 1.

Axial T1(a), axial T1 fat saturated(b), sagittal T2(c) MRI sequences and corresponding histopathology specimen(d) demonstrating a benign intramuscular lipoma (red arrow) in the forearm the forearm.

Lipoblastomas are benign lipomatous lesions seen in infants and young children. These lesions contain infantile fat; as a result, they may appear relatively less hyperintense on T1 images.2

Atypical lipomatous tumours (ALT) or well-differentiated liposarcomas (WDLS)are locally aggressive lipomatous tumours. Both these lesions are similar in histology and are differentiated by their location. ALTs occur in the extremities whereas lesions located in retroperitoneum and mediastinum are referred as WDLS. Tumour size of >10 cm, presence of thick irregular enhancing septa, presence of non-fat nodules within the lesion and lesion with fat content less than 75% indicate the possibility of ALT. Some of the variants of lipomas with atypical contents may not be able to differentiated from ALT and biopsy may be necessary.2,3

Malignant lipomatous lesions such as dedifferentiated liposarcoma contain a variable amount of non-fat component and often large in size. Sometimes, they may appear as fatty lesion with adjacent non fatty mass or two adjacent predominantly non lipomatous lesion.6 Imaging findings of malignant lipomatous lesions often overlap with that of ALTs. A biopsy is routinely performed, targeting the non-fatty component to differentiate it from other forms of lipomatous lesions.

Lesions which contain melanin may appear hyperintense on T1 and isointense to hyperintense on T2. A good example for soft tissue tumour which express melanin is clear cell sarcoma. This is a rare malignant lesion which grows slowly. This lesion has a predilection for limbs, particularly the lower limbs.7 (Fig. 2).

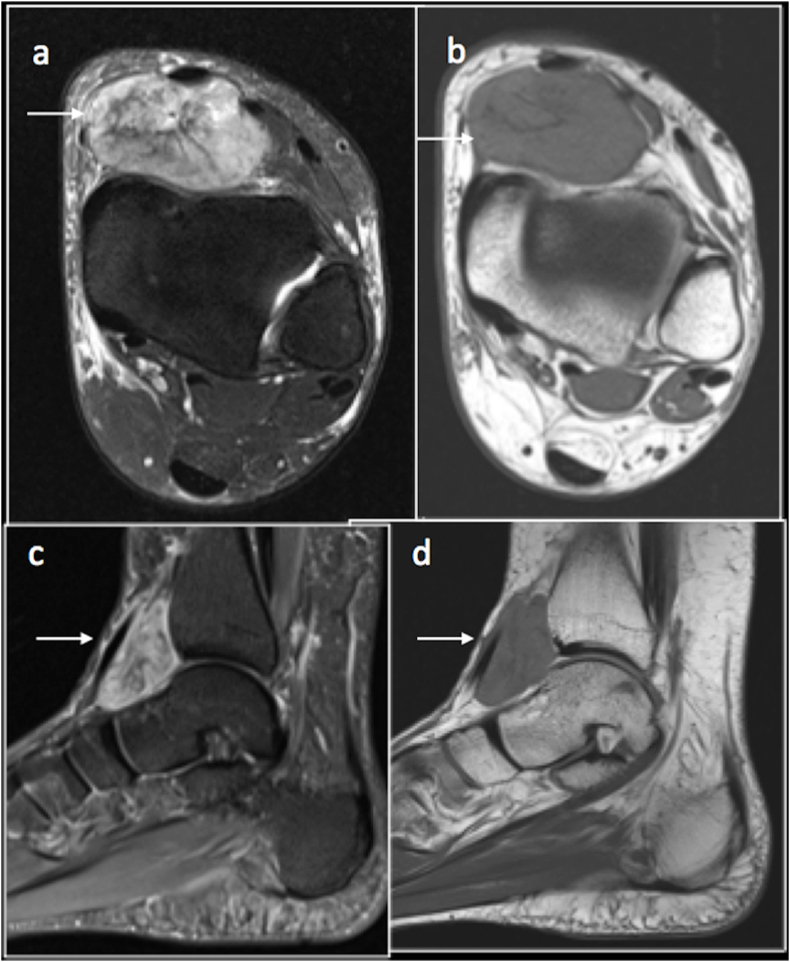

Fig. 2.

Clear cell sarcoma. T2FS(a), T1(b) axial, STIR (c) and T1(d) sag showing tumour anterior to ankle joint.

Other lesions which fall into this category are lesions with haemorrhage. Haemorrhagic lesions demonstrate variable appearance on MRI depending on the stage of haemorrhage and are often heterogeneous. Haematoma and angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma are examples of these lesions.

Lesions such as vascular malformations and elastofibroma dorsi due to their internal fat content can appear heterogeneously hyperintense on T1 and T2 images. Lesions with calcifications such as heterotopic ossification and myositis ossificans may also show similar signal depending on the stages of evolution.

3.2. T1 intermediate and T2 hyperintense lesions

Lesions which fall in this category are subacute haematomas and vascular malformations such as haemangiomas.

Haemangiomas are lobulated lesions with phleboliths and appear intermediate signal intensity on T1 and hyperintense on T2. Phleboliths and flow voids may appear as hypointense foci within the matrix (Fig. 3).

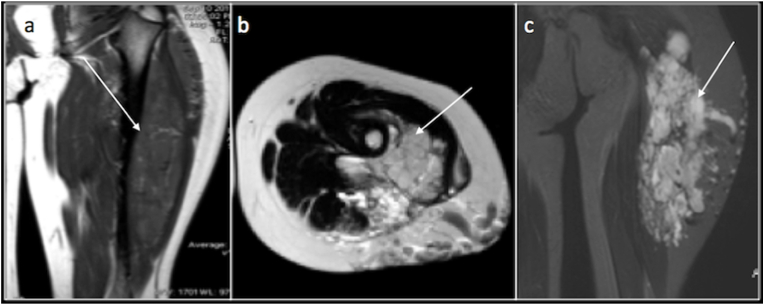

Fig. 3.

Coronal T1(a),Axial T2(b) and Coronal PDFS(c) images showing a T1 iso intense, T2 and PDFS hyperintense Arteriovenous Type of haemangioma of the proximal thigh.

Haematomas may demonstrate varied appearances depending on its stage of evolution. Acute to early subacute haematomas commonly appear intermediate signal intensity on T1 and high on T2.

Certain soft tissue sarcomas also show signal intensities compatible with this group.

Alveolar part soft tissue sarcoma is a rare slow-growing malignant tumour, accounting for 5% of paediatric nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas. This lesion is usually seen in adolescents, and young adults are more common in girls, the most common location is buttock or thigh. On MRI, they mimic haemangiomas and appear intermediate signal intensity on T1 and hyperintense on T2.8

3.3. T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense lesions

Myxoid lesions and ganglion cyst are common lesions which appear hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2.

Myxoid lesions are a group of mesenchymal neoplasms with abundant myxoid stroma. Due to the high-water content of myxoid tissue, these lesions mimic cysts on imaging and appear hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2.9 Myxoid lesions can be benign, locally aggressive or malignant. Although identifying a myxoid lesion on imaging is relatively easy further characterisation in to various subtypes of myxoid lesions is often challenging.

Intramuscular myxomas are the commonest myxoid lesions and are benign. They are slow growing lesions, with predilection for women, thigh being the commonest site. On MRI, these lesions are homogenously hypointense on T1 and extremely hyperintense on T2. They demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement on post contrast imaging10 and can sometimes demonstrate a stellate or septate pattern (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Intramuscular Myxoma: Axial T1(a), T2(b) and Post contrast T1 fat saturated(c) images demonstrating an intramuscular T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense lesion (arrow) with heterogeneous contrast enhancement with a stellate pattern.

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a locally aggressive myxomatous lesion predominantly involving females with predilection to perineum and lower pelvis. This lesion characteristically demonstrates swirled or layering pattern on T2 images due to coursing collaging fibrils in myxoid stroma.11

Myxoid liposarcoma is a malignant lesion comprising a predominantly myxoid matrix with focal areas of fat (<10%). Fatty component is the distinguishing feature of this lesion.

Myxoid chondrosarcoma, due to its chondroid matrix may contain internal calcification and ossifying fibro myxoid tumour can also demonstrate peripheral ossifications which are seen as T1 and T2 hypointense foci in a myxoid lesion. However, CT is more useful in demonstrating these calcifications or ossifications than MRI10

The Findings suggesting possibility of malignant myxoid lesion are ill-defined margins of the lesion, haemorrhagic component within the lesion, fibrosis, tail sign, wherein tumour demonstrates fascial enhancement extending from the margins and intra-tumoural fat12

Common true cystic lesions seen in the soft tissues are ganglion cyst, synovial cysts, bursa, post-surgical collections and lymphatic malformations.

Ganglion or synovial cysts are commonest cystic lesions. These are commonly located around the joints or tendons with fluid signal intensity on MRI without discernible contrast enhancement differentiating them from myxoid lesions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Ganglion Cyst- T1 coronal (a) and PDFS sagittal images (b) demonstrating a T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense proximal tibiofibular joint ganglion.

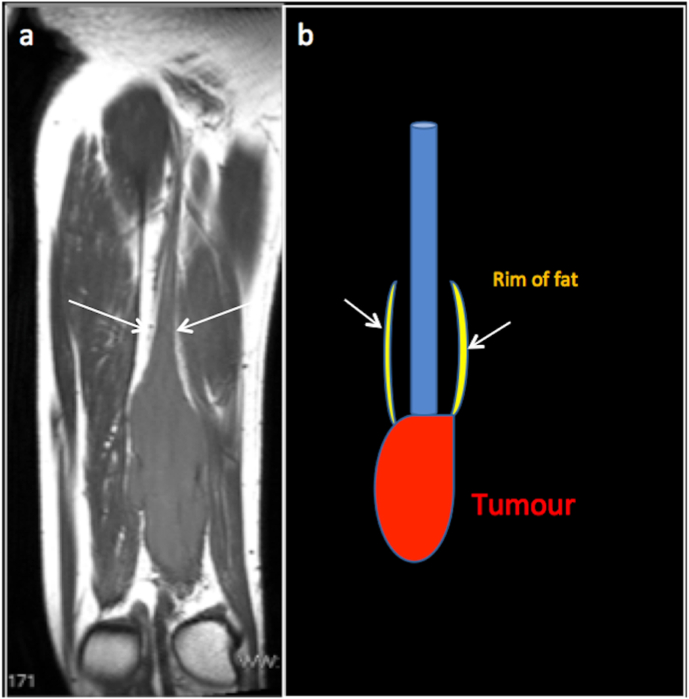

3.4. T1 hypointense and T2 hypointense lesions

Lesions which contain haemosiderin or dense fibrous lesions demonstrate low signal intensity on T1 and T2 weighted images.

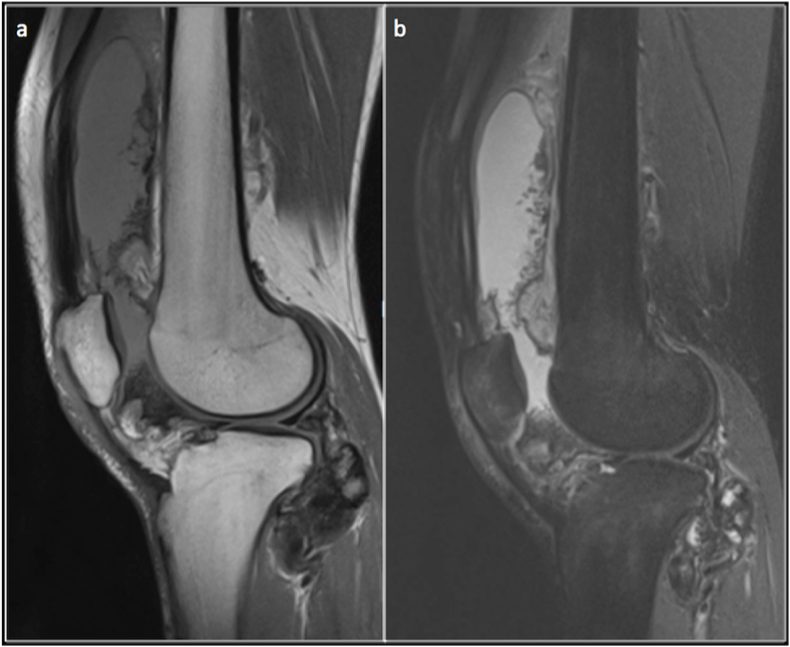

Tenosynovial giant cell tumour (TSGT) is a term which encompasses benign inflammatory and proliferative lesions arising from synovium, bursae and tendon sheath, namely the giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath and the pigmented villonodular synovitis. Based on the location, tenosynovial giant cell tumours can be extra articular or intraarticular. Based on the pattern of growth, they can be classified as localised or diffuse TSGT and Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). Localised form is commonly extra articular and tends to involve tendon sheath, whereas diffuse TSGT and PVNS specifically involve large joints such as knee joint.13).

TSGTs on MRI are heterogeneous, and the majority of these lesions demonstrate characteristic T1 and T2 hypointensity due to the presence of haemosiderin. Diffuse TSGTs are more heterogeneous and tend to demonstrate larger T1 and T2 hypointense areas (Fig. 6). They enhance heterogeneously on post-contrast images, and this heterogeneity is more pronounced in Diffuse TSGTs14

Fig. 6.

Diffuse Tenosynovial Giant cell tumour – Sagittal T1(a) and Proton density fat saturated(b) images demonstrating a hypointense lesion in the Hoffa's fat pad and along the posterior joint capsule of the knee joint.

Densely fibrous lesions appear hypointense on T1 and T2 due to the presence of collagen-rich stroma. Fibromatosis refers to a group of neoplasms characterised by proliferation of fibroblasts. These lesions can be benign or locally aggressive. Fibromatosis can be superficial or deep. Deep fibromatosis can be further classified as extra-abdominal (predominantly affecting the upper extremities), abdominal wall (involving rectus abdominis or internal oblique muscle and fascia around it) and intra-abdominal fibromatosis (involving the mesentery).

Superficial fibromatosis commonly involves palmar aponeurosis/flexor tendons (palmar fibromatosis) or plantar fascia (plantar fibromatosis). They appear as nodular or band-like lesions which are hypointense on T1 and T2 due to abundant collagen. Cellular variants with less collagen may show relatively increased T2 signal. Extra abdominal fibromatosis is usually seen in intermuscular plain or along the deep fascia. Abdominal wall and extra-abdominal fibromatosis are heterogeneous on MRI with low signal intensity areas on T1 and T2. Fibromatosis contains cellular and collagenous matrix. As the lesions mature collagen content increases with reduced cellularity. Lesions with high cellularity appear relatively hyperintense on T2. As the lesions mature with the increasing amount of collagen and reduced cellularity in the matrix, they appear increasingly low signal intensity lesions on T1 and T2.15 (Fig. 7).

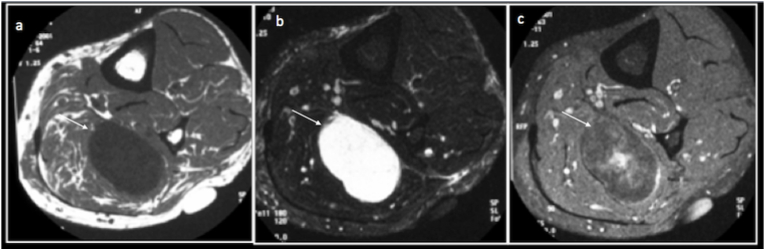

Fig. 7.

Fibromatosis – Axial T1(a) and Axial T2 Fat Saturated images demonstrating a large fibromatosis (arrow) in the intermuscular plane of the posterior compartment of the thigh.

4. Signs

Signs are distinct radiological appearances of an abnormality. There are many well-described signs in soft tissue lesions that are useful for narrowing down the differentials and helping to come to a definitive diagnosis.

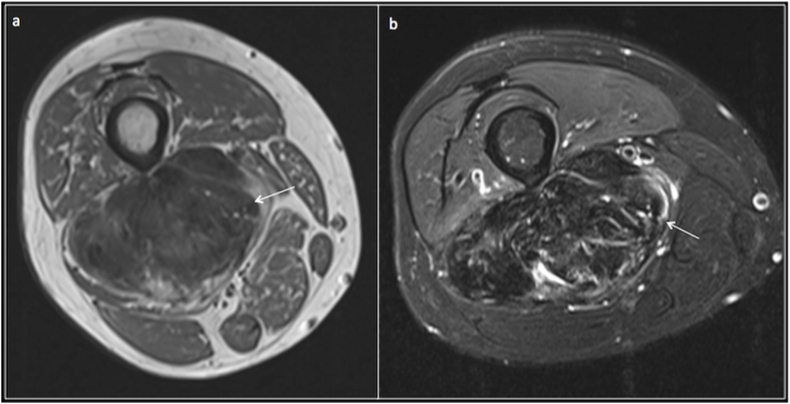

Split fat sign: This sign denotes the presence of fat around a lesion, especially at its proximal and distal ends. This is best appreciated in T1 in the coronal plane. This sign is classically used to describe peripheral nerve sheath tumours; however, it can be seen in any slow-growing lesion arising from the intermuscular plain. Neurovascular bundles are generally surrounded by fat. A lesion, which is slow-growing and arises from the neurovascular bundle, tends to retain this fat around it, particularly near the proximal and distal end. A rapidly growing lesion invades the surrounding fat and unlikely to demonstrate a split fat sign.16 (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

T1 Coronal image (a) and corresponding illustration (b) demonstrating spit fat sign, T1 coronal image demonstrates a neurogenic lesion in the thigh with retained rim of fat (arrow) (the split-fat sign) around the ends of the lesion.

Target sign: This sign is helpful to identify a neurogenic lesion. On T2 central part of the lesion demonstrates hypointense signal due to fibrous tissue and a hyperintense periphery due to the presence of myxoid tissue. This is more commonly seen in neurofibromas.17 (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Target sign -Axial (a) and coronal (b)PD fat saturated showing the hyperintense periphery(short arrow) and central hypointense(long arrow) signal in a neurofibroma.

Fascicular sign: This is another sign which indicates neurogenic tumours. This sign appears on T2 WI or proton density images as multiple small ring-like hypointense foci surrounded by hyperintense areas. These hypointense foci possibly correspond to fascicular bundles seen in neurogenic tumours on pathological examinations.17,18

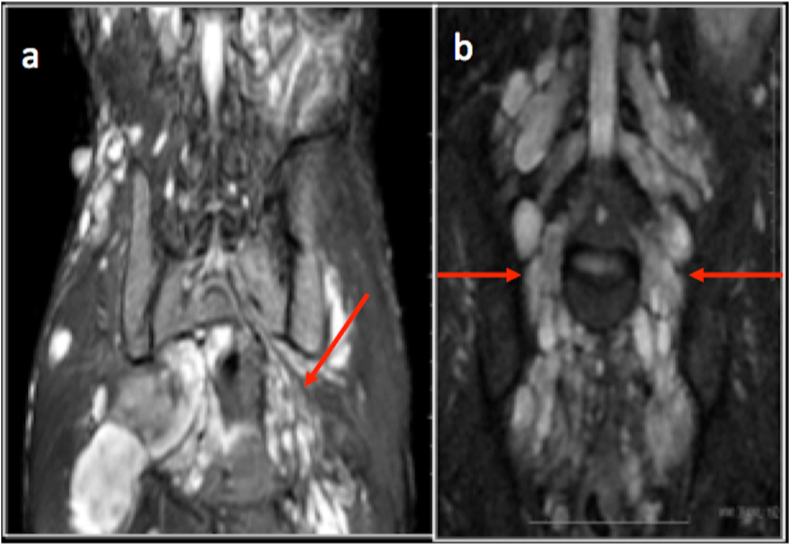

Serpentine bag of worm appearance – This is a characteristic finding in plexiform neurofibromas. Due to the nerve and its branches' involvement, there is nodular appearance with branching pattern resembling a serpentine bag of worms.18(Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Plexiform Neurofibroma- Coronal T2 Fat saturated images (a and b) demonstrating nodularity and involvement of nerve branches, creating the appearance of a “Serpentine Bag of worms”.

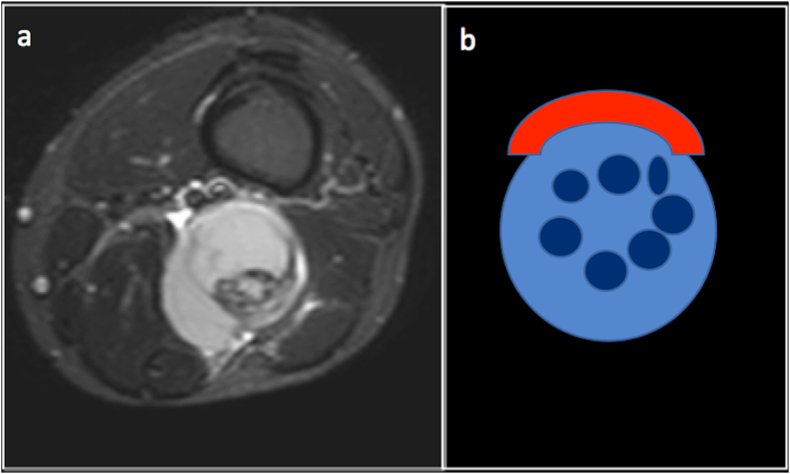

Perineural tumour cuffing sign – Some lesions may grow around the nerve and on post contrast imaging they can demonstrate an enhancing tumour tissue cuffing the nerve (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Perineural tumour cuffing in a Sciatic lymphoma -T1 Post contrast Fat suppressed axial image(a) and corresponding illustration (b) showing tumour cuffing the Sciatic nerve.

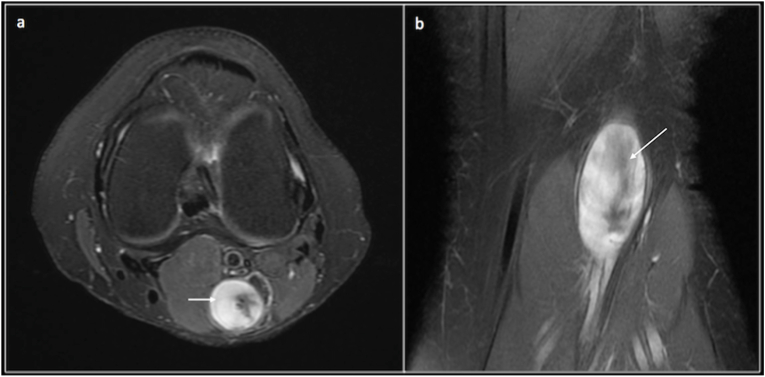

Dot in circle sign – This is described in mycetoma, a fungal infection of the foot. In mycetoma, an abscess appears hyperintense on T2, and a central dot of the low signal represents fungal granule (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Axial T2 images of the foot in a patient with mycetoma (a and b) and corresponding illustration (c) demonstrating dot in circle sign. The dot-in-circle sign is a recently described sign reflecting the unique pathological feature of mycetoma on MRI. Dot Represents the T2 hypointense fungal granule (red arrow). Circle represents the T2 hyperintense abscess or granuloma with peripheral fibrous matrix (green arrow).

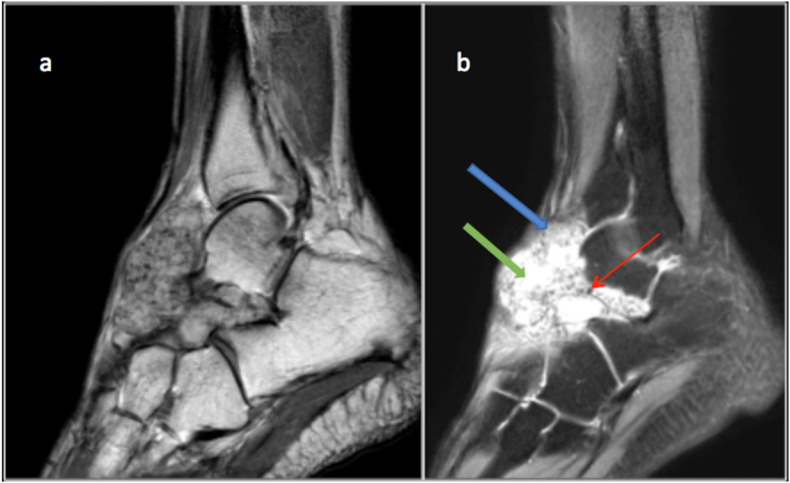

Triple sign of synovial sarcoma – On fluid sensitive sequences Synovial sarcomas appear heterogeneous and demonstrates areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity. Haemorrhage and necrosis within the tumour appear as hyperintense, cellular component demonstrates intermediate signal and calcification or fibrotic changes appear as hypointense foci. Although this appearance is frequently seen in synovial sarcomas, this can also be seen in other soft tissue lesions such as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.19 (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

T2 (a) and STIR (b) sagittal images showing a synovial sarcoma of the mid foot dorsum with Triple sign. Solid cellular elements (blue arrow) demonstrating intermediate signal intensity, haemorrhage or necrosis (green arrow) demonstrating high signal intensity, and calcified or fibrotic collagenized regions (red arrow) showing low signal intensity.

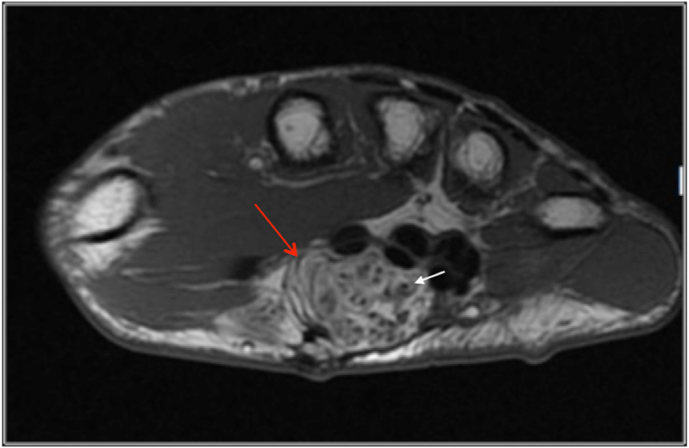

Coaxial cable sign: This sign is described in fibrolipohamartoma of nerve. In the axial T1 images, hypointense nerve fascicles are surrounded by hyperintense fibro adipose tissue resulting in a coaxial cable appearance (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14.

Coaxial Cable sign –Axial T1 image demonstrating a fibrolipohamartoma of the median nerve (red arrow) with hypointense nerve fascicles (white arrow) surrounded by hyperintense fibro adipose tissue resulting in a coaxial cable appearance.

Lipoma arborescence – broccoli sign is due to fronds of hypertrophied synovium resembling broccoli is often seen.

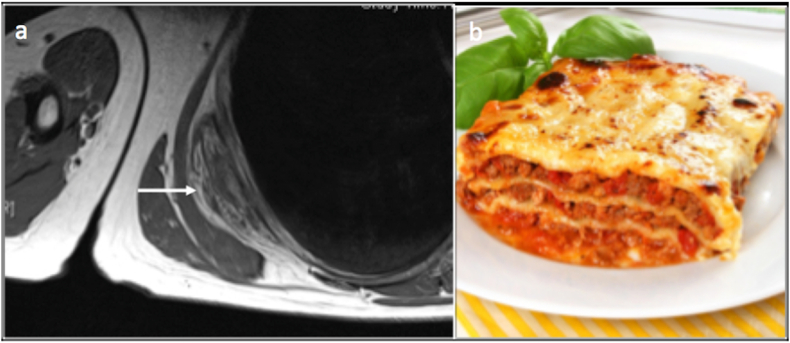

Lasagne sign – This is seen in elastofibroma dorsi. On both T1 and T2 of MRI, Elastofibroma, an unencapsulated inhomogeneous soft tissue mass, demonstrates signal intensities similar to skeletal muscle, interlaced with steaks of fat (resembling Lasagne) with heterogeneous enhancement on post-contrast studies(Fig. 15) Table 3.

Fig. 15.

Elastofibroma Lasagne sign. T1 axial image (a) demonstrating elastofibroma which appears as well defined, unencapsulated inhomogeneous soft tissue mass with signal intensity similar to that of skeletal muscle, interlaced with streaks of fat resembling a Lasagne (b).

Table 3.

Signs (SLAM).

| Triple sign: Synovial sarcoma |

| Lasagne sign: Elastofibroma |

| Broccoli sign: Lipoma arborescence |

| Fascicular sign: Neurogenic tumours |

| Comet Tail sign: Neurogenic tumours |

| Target sign/Bulls eye sign: Neurogenic tumours |

| Dot in circle sign: Mycetoma Foot |

| Coaxial cable sign: Lipo fibromatous Hamartoma Median nerve |

4.1. Localisation clue

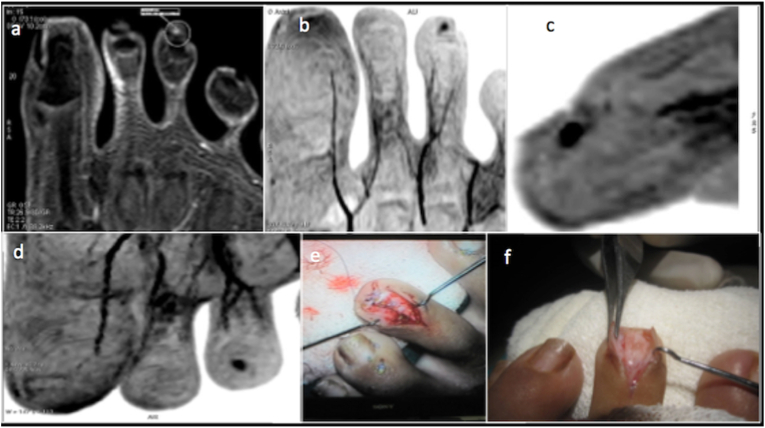

Location of a soft tissue lesion may provide a clue for its diagnosis. Some lesions are distinctive to their site. Glomus tumour is characteristically seen In Subungual location (Fig. 16). Elastofibroma dorsi is typically located along the inferior border of the scapula. A few lesions demonstrate a predilection for a particular region of the body; for instance, ganglia are commonly located around a joint. Morel Lavelle lesions are seen at the junction of superficial and deep fascia. Some lesions follow the course or seen at the expected location of the organ of their origin. Neurogenic tumours follow the nerve of its origin or seen at the expected location of a nerve (Fig. 17). Giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath is seen in relation to the tendons. Vascular lesions such as venous malformations or haemangiomas are often located close to veins. A list of lesions and their site predilections are described in table.4 (see Table 4)

Fig. 16.

Subungual glomus tumour -Post contrast T1 fat saturated image(a) and MIP projections (b,c,d) demonstrating a intensely enhancing lesion in the subungual location of the 3rd toe. Surgical photographs (e,f)confirming the glomus tumour.

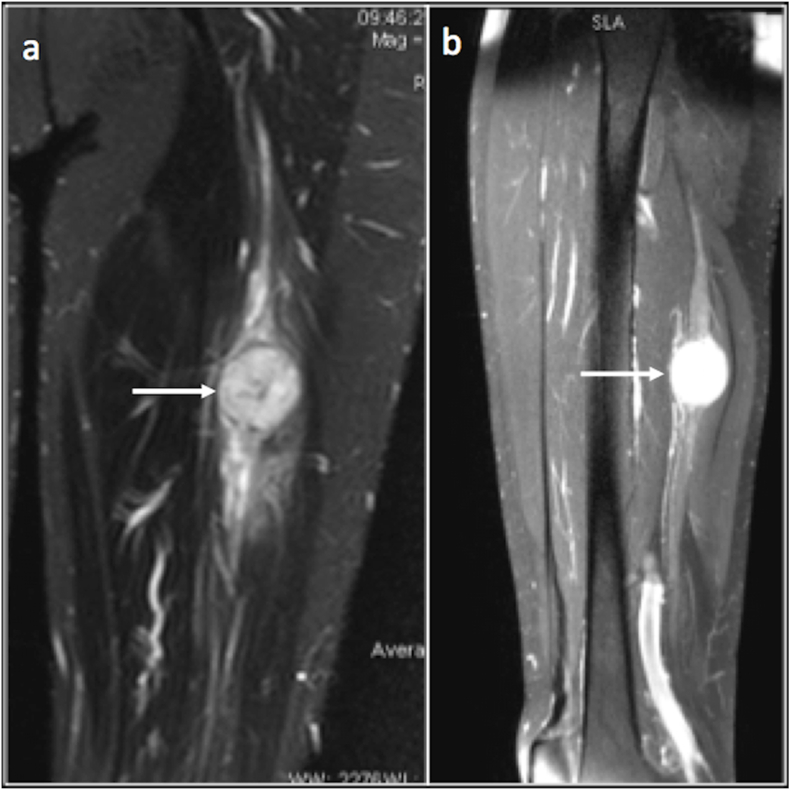

Fig. 17.

Coronal and sagittal proton density fat saturated images demonstrating a neurogenic lesion (arrow) along the course of sciatic nerve.

Table 4.

Localisation clues (SLAM).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.2. Age group

The pattern of the soft tissue lesions encountered differs with the age group. In the paediatric age group, most common soft tissue lesions are vascular lesions such as vascular malformations or haemangiomas, whereas lipomatous lesions are common in adults. Some lesions are characteristically seen in childhood. In lipomatous lesions, lipoblastoma, almost always occur in the paediatric age group, especially in less than three years of age. Site predilection and histological type of sarcomas also differ with age. While adult soft tissue sarcomas are commonly seen in extremities, paediatric sarcomas are frequently encountered in the head and neck region with rhabdomyosarcoma being the most common histological type of sarcomas seen in the paediatric age group.20(Table 5).

Table 5.

Age group clues (SLAM).

| Children: |

| Haemangioma |

| Fibrous hamartoma |

| Granuloma annulare |

| Lipoblastoma |

| Fibrosarcoma |

4.3. Multiplicity

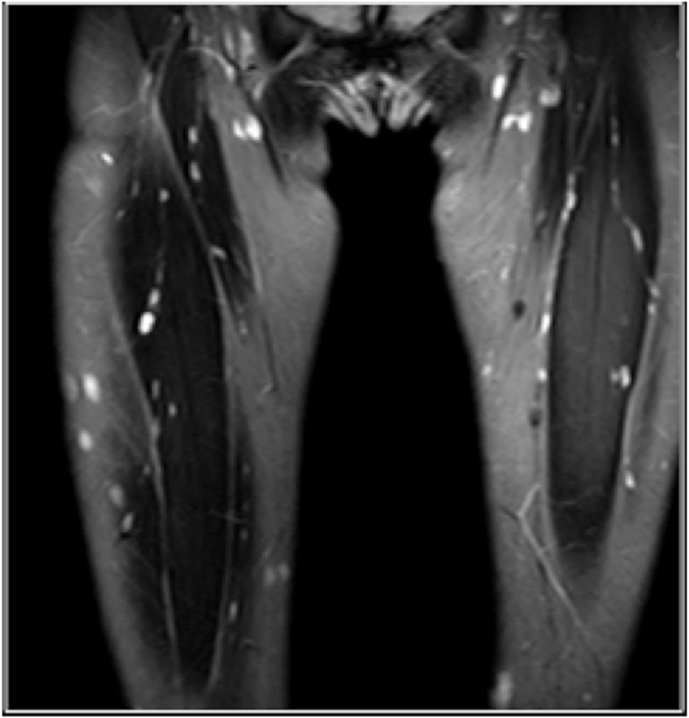

Some of the soft tissue lesions can be multiple. Common soft tissue lesions demonstrating multiplicity are described in Table 6. The multiplicity of the lesions may be used to narrow down the differentials, at the same time effort should also be made to identify the additional lesions in the available images, if a lesion known to demonstrate multiplicity is encountered (Fig. 18).

Table 6.

Multiplicity (SLAM).

| Neurofibromatosis |

| Schwannomatosis |

| Haemangioma |

| Lymphangioma |

| Desmoid tumours |

| Xanthoma |

| Metastases |

| Angiosarcoma |

Fig. 18.

Coronal Proton density fat saturated images demonstrating multiple hyperintense neurofibromas in both thigh.

4.4. Matrix mix –

Matrix is an essential structural component of a lesion. Composition of the matrix is unique to a tumour and often responsible for its imaging appearances. Identifying the tumour matrix based on imaging appearances is an effective way to reach the diagnosis. Matrix compositions of tumours are varied. M10 rule is a simplified way to remember various matrix composition a tumour can have (Table 7) (see Table 8).

Table 7.

Matrix mix/Morphology (SLAM).

| Melanin: Clear cell Sarcoma |

| Methaemoglobin: Haemorrhage in a tumour/Haematoma |

| Mucin: Metastatic adenocarcinoma |

| Mycelia (septal hyphae):Fungal pathology-mycetoma |

| Matrix Mix: Calcium, Phleboliths, haemosiderin, fat, cellularity fluid (HADD) |

| Makhan (Fat):Lipoma, Lipoblastoma |

| Myxoid: Myxoma, Myxoid Liposarcoma |

| Mycobacterial Mineralization- Tuberculosis |

| Menstrual: Endometriosis |

| Metal: or Particle disease |

Table 8.

MRI features of benign and malignant soft tissue lesions.

| Parameters | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Superficial to the deep fascia | Deep to the deep fascia |

| Size | <5 cm | >5 cm |

| Signal Intensity | Homogenous | Heterogeneous |

| Margin | Smooth | Irregular |

| Contrast enhancement | Homogenous | Heterogeneous |

| Diffusion MRI | Relatively higher mean ADC value | Relatively Low mean ADC value. |

5. Conclusion

SLAM approach is a simplified, systematic method to characterise soft tissue tumours and tumour like conditions. Analysing the lesions using a combination of parameters of SLAM is helpful to arrive at a diagnosis.

Compliance with ethical standards

No funding to declare.

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed consent was not required as its a review of new approach to soft tissue tumours rather than a study.

References

- 1.Wu Jim S., Hochman Mary G. Soft-tissue tumors and tumor like lesions: a systematic imaging approach. Radiology. 2009;253(2):297–316. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532081199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta P., Potti T.A., Wuertzer S.D., Lenchik L., Pacholke D.A. Spectrum of fat-containing soft-tissue masses at MR imaging: the common, the uncommon, the characteristic, and the sometimes confusing. Radiographics. 2016;36(3):753–766. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan S., Visgauss J., Kerr D., et al. sarcoma; 2018. The Value of MRI in Distinguishing Subtypes of Lipomatous Extremity Tumors Needs Reassessment in the Era of MDM2 and CDK4 Testing. Article ID 1901896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kransdorf MJ, Bancroft LW, Peterson JJ, Murphey MD, Foster WC, Temple HT. Imaging of fatty tumors: distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma. Radiology;224:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Chhabra A., Soldatos T. Soft-tissue lesions: when can we exclude sarcoma? Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(6):1345–1357. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong S.H., Kim K.A., Woo O.H., et al. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of retroperitoneum: spectrum of imaging findings in 15 patients. Clin Imag. 2010;34(3):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Beuckeleer L.H., De Schepper A.M., Vandevenne J.E., et al. MR imaging of clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of the soft parts): a multicenter correlative MRI-pathology study of 21 cases and literature review. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(4):187–195. doi: 10.1007/s002560050592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarville M.B., Muzzafar S., Kao S.C., et al. Imaging features of alveolar soft-Part Sarcoma: a report from children's oncology group study ARST0332. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203(6):1345–1352. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baheti A.D., Tirumani S.H., Rosenthal M.H., et al. Myxoid soft-tissue neoplasms: comprehensive update of the taxonomy and MRI features. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(2):374–385. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petscavage-Thomas J.M., Walker E.A., Logie C.I., Clarke L.E., Duryea D.M., Murphey M.D. Soft-tissue myxomatous lesions: review of salient imaging features with pathologic comparison. Radiographics. 2014;34(4):964–980. doi: 10.1148/rg.344130110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surabhi V.R., Garg N., Frumovitz M., Bhosale P., Prasad S.R., Meis J.M. Aggressive angiomyxomas: a comprehensive imaging review with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(6):1171–1178. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crombe A., Alberti N., Stoeckle E., Buy X., Coindre J.M., Kind M. Soft tissue masses with myxoid stroma: can conventional magnetic resonance imaging differentiate benign from malignant tumors? Eur J Radiol. 2016;85(10):P1875–P1882. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haijun T., Yun L., Xinli Z., Zengming X. Treatment of tenosynovial giant-cell tumour types. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(8):e398. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30419-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C., Song R.R., Kuang P.D., Wang L.H., Zhang M.M. Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath: magnetic resonance imaging findings in 38 patients. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(6):4459–4462. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker E.A., Petscavage J.M., Brian P.L., Logie C.I., Montini K.M., Murphey M.D. Sarcoma; 2012. Imaging Features of Superficial and Deep Fibromatoses in the Adult Population. Article ID 215810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung J., Kim J.-Y. Fatty rind of intramuscular soft-tissue tumors of the extremity: is it different from the split fat sign? Skeletal Radiol. 2017;46(5):665–673. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chee Daniel W.Y., Peh Wilfred C.G., Shek Tony W.H. Pictorial essay: imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2011;62(3):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphey Mark D., Sean Smith W., Smith Stacy E., Kransdorf Mark J., Thomas Temple H. Imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors. Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation1 RadioGraphics. 1999;19(5):1253–1280. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se101253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphey M.D., Gibson M.S., Jennings B.T., Crespo-Rodriguez A.M., Fanburg-Smith J., Gajewski D.A. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543–1565. doi: 10.1148/rg.265065084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sangkhathat S. Current management of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4(4):94–105. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v4.i4.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]