Abstract

Objectives:

Packaging is an important component of tobacco marketing that influences product perceptions and use intentions. However, little research exists on cigar packaging. We leveraged variability in existing Swisher Sweets cigarillo packaging to extend the evidence base.

Methods:

Between 2017 and 2019, we conducted three online experiments with 774 young adult past-year cigar smokers recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk. After viewing Swisher package images that differed by flavor descriptor and/or color, participants rated them on perceptions and purchase intentions. In Study 1, participants viewed one of four cigarillos (“Wild Rush Encore,” “Wild Rush Limited,” “Twisted Berry,” “Strawberry”). In Study 2, participants viewed two different watermelon rum-flavored cigarillos (“Boozy Watermelon,” “Island Madness”). In Study 3, participants viewed two of three “Wild Rush” cigarillo versions (“Encore” with or without an explicit flavor descriptor or “Limited”).

Results:

In Study 1, more participants perceived “Twisted Berry” and “Wild Rush Limited” as tasting good and less harsh-tasting compared to “Wild Rush Encore.” In Study 2, compared to “Island Madness,” more participants perceived “Boozy Watermelon” as tasting good, less harsh-tasting, and used by younger users but less by masculine users; female participants were more likely to purchase “Boozy Watermelon.” In Study 3, participants perceived “Wild Rush Encore” with the explicit flavor descriptor as tasting better than packages without, and being used by younger users but less by masculine users.

Conclusions:

Variations in cigarillo packaging, even among cigarillos with the same flavor, may have differential consumer appeal, suggesting packaging features should be considered in cigar product regulation.

INTRODUCTION

Cigar use continues to be prevalent among young adults in the United States, with 16.3% and 7.7% of 18–25 year olds reporting cigar use in the past year and month, respectively, in 2019.1 Cigarillos are the most popular cigar type preferred by young adults,2 likely due to the appeal of flavor variety.3–5 Flavors may be communicated to consumers with explicit descriptors (e.g., strawberry) or more non-descript concept descriptors (e.g., “Wild Rush”) that may evade some enforcement and criticism about overt flavored marketing. Indeed, the cigar market maintains its diversity through the constant introduction of new cigar products with memorable descriptors and vivid packaging.6 7 However, under the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) deeming rule, new cigars cannot be introduced to the market after August 8, 2016 without FDA pre-market authorization. Despite this, the cigar market continued to diversify after deeming,8 with cigar manufacturers introducing numerous cigars with new distinct flavor names and packaging to the market after that date, raising the question of whether packaging a product differently makes it a different product in itself.

In September 2015, FDA industry guidance suggested that distinct labeling changes to an existing product is a new tobacco product requiring pre-market authorization. Yet, in 2016, a US federal court rejected that approach, finding that a “modification to an existing tobacco product’s label,” absent other changes, does not make it a new tobacco product.9 However, research suggests the contrary. Package design is an important component of tobacco marketing because the various components that make up a product’s packaging, including color, brand name, and the use of flavor descriptors, can make a difference in how people perceive the product.10 11 In turn, perceptions about the product’s taste, quality, and harmfulness may influence intentions to purchase and use the product.12 13 Perceptions about the types of consumers such products are intended for or used by (e.g., young people, men) may also provide signals about potential differential product appeal among different consumer audiences.

There is limited evidence on the effects of tobacco packaging in the context of cigars. However, recent studies have shown the potential impact of cigarillo packaging features on young adult perceptions. In one qualitative study, when shown images of real-world cigarillo packs from different brands, young adults identified flavor descriptors as the most appealing feature and commented on the role of pack color in eliciting thoughts about flavors.14 Similarly, experimental studies found that flavor descriptors (particularly characterizing, non-tobacco flavors) and pack color influenced perceptions of appeal, taste, smell, and/or harshness.13 15–17

Though the evidence base is growing, the few experimental studies that find effects of cigarillo packaging elements do so in the context of manipulated cigarillo images,13 15–17 pointing to the need for more externally valid findings. Thus, we aimed to move the literature forward by conducting a set of three exploratory studies, all of which utilized existing Swisher Sweets packaging as stimuli in order to examine cigarillo packaging that users were exposed to in the actual marketplace, thereby maximizing ecological validity. Given the important role of characterizing flavors and resulting sensory expectancies in young adult tobacco use,4 18 all three studies had the common objective of exploring the impact of different types of flavor references (explicit vs. concept) and pack color on young adult perceptions and intentions. In Study 1, we explored the effects of packs with similar colors but different explicit and concept flavor descriptors. In Study 2, we examined differences between two packs with the same explicit flavor but different concept flavor descriptors and colors. In Study 3, we assessed the impact of packs with the same concept flavor descriptor and color but varied in the presence of an explicit flavor descriptor. These latter packs also varied as to whether they were described as being an “Encore” versus a “Limited” edition of that style. In addition to examining perceived harm and sensory related outcomes (such as taste and smell) that were consistent with previous experimental studies,13 15–17 we also included exploratory measures about perceived product users (i.e., young, masculine). Finally, given our interest in potential differential product appeal and that many of the existing packs we examined featured shades of pink/red coloring, we included subgroup analyses of results by gender for exploratory purposes.

METHODS

We conducted three brief (4–5 minutes each) online experiments with young adults recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Each study had the same eligibility criteria – participants had to be 18–34 years old, and to have used a cigar (i.e., used any type of cigar or cigarillo or smoked a blunt) in the past 12 months. Eligible participants who provided their informed consent online were allowed to move forward with the survey, and those who completed it were compensated through MTurk. The Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved all procedures for each study. Additional details for each study are described next.

Study 1

Procedures.

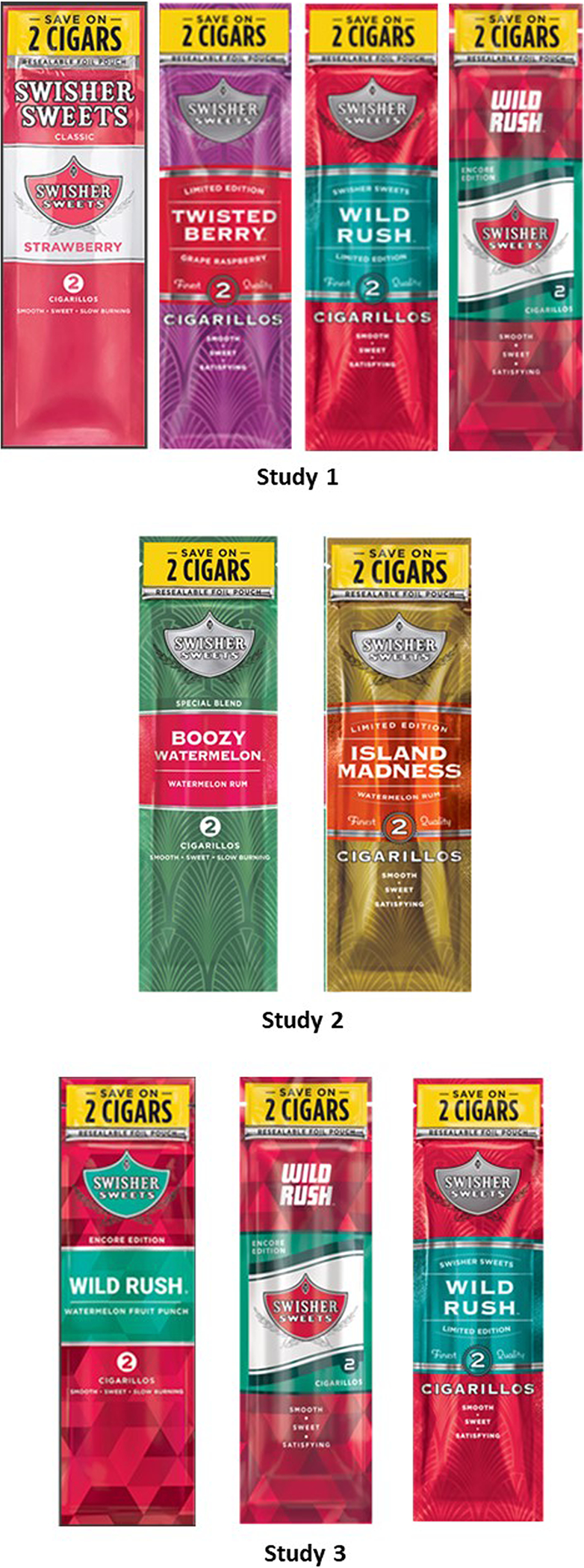

In July 2017, eligible participants (n=333) were randomly assigned to view one of four images of a Swisher Sweets cigarillo package that varied by flavor descriptor. Two of these featured explicit flavor descriptors (“Strawberry”; “Twisted Berry Limited Edition”) and two featured non-descript “concept” flavor descriptors (“Wild Rush Limited Edition”; “Wild Rush Encore Edition”). These packages also varied in design and color, though all were prominently pink/red or purple (Figure 1). The two Wild Rush products had the same flavor, despite packaging differences. Participants viewed the image and rated the product in the image on several perceptions and purchase intentions (the relevant image stayed on the screen throughout the entirety of the survey portion that asked about that product).

Figure 1.

Swisher Sweets cigarillo package stimuli.

Note. Study 1 packages from left to right: “Strawberry,” “Twisted Berry,” “Wild Rush Limited Edition,” “Wild Rush Encore Edition.” Study 2 packages from left to right: “Boozy Watermelon,” “Island Madness.” Study 3 packages from left to right: “Wild Rush Encore Edition – watermelon fruit punch,” “Wild Rush Encore Edition,” “Wild Rush Limited Edition.”

Measures.

Product Perceptions.

We assessed product perceptions by asking whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: “This product looks like it is harsh-tasting”; “This product looks like it is harmful to your health”; “I think this product might taste good”; “I think this product might smell nice”; “This product looks like it is high quality tobacco”; “A typical user of this product is masculine;” “A typical user of this product is young.” All responses were on five-point scales ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” Responses to the first two measures (harsh-tasting and harmfulness) were reverse-coded so that “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses indicated positive perceptions about the product. For purposes of reporting descriptive statistics, we dichotomized all outcome measures such that 1=“Strongly agree” and “Agree” and all other responses were coded as 0.

Purchase Intentions.

We assessed participants’ purchase intentions with the following measure, adapted from the Juster Purchase Probability Scale: “What is the likelihood that you will buy this product in the future?”19 Responses were on a five-point scale: “No chance or almost no chance,” “Very slight possibility,” “Some possibility,” “Probable,” “Certain or practically certain.” For purposes of reporting descriptive statistics, we dichotomized this measure such that 1=“Certain or practically certain” and “Probable,” and all other responses were coded as 0.17

Demographics.

Participants provided the following demographics: age, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, highest level of education completed, current college student status, employment, and income.

Data analyses.

To ensure that random assignment yielded equivalent groups, we first conducted chi-square tests. Experimental conditions did not differ by any of the demographic characteristics (all p>1.0). We then used descriptive statistics to estimate the proportion of respondents in each experimental condition who reported agreement with each of the study outcomes. Subsequently, we conducted two-sample proportion tests to assess differences in perception ratings and two-sample t-tests to assess mean differences in intentions between product pairs, so as to compare all products with each other (i.e., 6 possible pairs). We also conducted additional subgroup analyses by gender. All statistical tests used a critical alpha of .05, and were conducted in Stata 16.

Study 2

Procedures.

In December 2018, we conducted a second brief online experiment in which participants (n=402) viewed, in random order, two images of a Swisher Sweets cigarillo package. The two packages varied by the concept flavor descriptor used (“Island Madness” vs. “Boozy Watermelon”), which was prominently featured on the pack, but both included the same explicit flavor descriptor (“watermelon rum”) in smaller font further below– indicating that these products had the same flavor. These packages also varied in color (tan vs. green) (Figure 1). Participants viewed the image and rated the product in the image on several perceptions.

Measures.

We assessed participants’ perceptions, purchase intentions, and demographics using the same measures described under Study 1.

Data analyses.

Chi-square tests ensured that experimental conditions did not differ by any of the demographic characteristics (all p>0.7), and that random assignment yielded equivalent groups. We used descriptive statistics to estimate the proportion of respondents in each experimental condition who reported agreement with each of the study outcomes. We then conducted one-sample proportion tests to examine differences in perception ratings and paired t-tests to examine mean differences in intentions by product, and conducted additional subgroup analyses by gender. Statistical tests used a critical alpha of .05, and were conducted in Stata 16.

Study 3

Procedures.

In April 2019, we re-contacted all 18–34 year old, past-year cigar users who were deemed eligible from the screener in Study 2; 335 eligible participants completed the study. Participants were randomized to two conditions. Each condition required participants to view (in random order) two images of a Swisher Sweets cigarillo package, one with a concept flavor descriptor (either “Wild Rush Encore Edition” or “Wild Rush Limited Edition,” depending on the condition) and one with an added explicit flavor descriptor (“Wild Rush Encore Edition-watermelon fruit punch” in both conditions) (Figure 1). All three products had the same flavor, despite the variation in packaging. Participants viewed the image and rated the product in the image on several perceptions.

Measures.

Product Perceptions.

We assessed participants’ perceptions using the same measures described under Study 1.

Purchase Intentions.

In this study, we assessed participants’ purchase intentions in two ways: direct measures and comparative measures. Direct purchase intentions were assessed in the same way as Study 1 and 2. Comparative purchase intentions were assessed after participants had viewed both images and responded to the direct purchase intention measures. They were shown both images again, side by side, and were asked: “Which of the two would you be more likely to buy?” Response options were the two products shown.

Data analyses.

Again, chi-square tests indicated experimental conditions did not differ by any demographic characteristics and that randomization was successful (all p>0.7). We used descriptive statistics to estimate the proportion of respondents in each experimental condition who reported agreement with each of the study outcomes. We then conducted one-sample proportion tests to assess differences in perception ratings and comparative intentions, and paired t-tests to assess mean differences in direct intentions within each condition, as well as subgroup analyses by gender. Statistical tests used a critical alpha of .05, and were conducted in Stata 16.

RESULTS

Participants’ mean age in each of the three studies ranged from 26.5 to 27.7 and a little less than half of the samples were female (46% for Study 1 and 2, 48% for Study 3). Hispanic/Latinos comprised 9.6%, 13.0%, and 12.2% of the samples for Study 1, 2, and 3 respectively. Participants were predominantly white (82.3%, 71.8%, 71.3%) and heterosexual (84.1%, 80.3%, 81.1%) across all three samples. The majority of the sample had attained at least some college education in each study (84.1%, 82.5%, 84.5%), and current (full-time or part-time) college students comprised 33.0%, 37.9%, and 37.6% of each sample. A little less than two-thirds of each sample were currently employed full-time (63.7%, 63.3%, 66.3%).

As shown in Table 1, the packages with different flavor descriptors in Study 1 produced significantly different perceptions about the product. More participants rated “Twisted Berry,” “Strawberry,” and “Wild Rush Limited Edition” as tasting good compared to “Wild Rush Encore Edition.” Similarly, more participants rated “Twisted Berry” and “Wild Rush Limited Edition” as being less harsh tasting compared to “Wild Rush Encore Edition.” In addition, “Twisted Berry” was perceived by more participants as being for younger users compared to “Wild Rush Encore Edition” and “Wild Rush Limited Edition,” and fewer agreed “Twisted Berry” was typically used by “masculine” users relative to the other packs.

Table 1.

Perceptions by Product, Study 1

| Overall (n=333) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Rush Encore a (n=86) |

Wild Rush Limited b (n=81) |

Twisted Berry c (n=83) |

Strawberry d (n=83) |

|

| This product looks… | ||||

| Taste good | 51.2% b,c,d | 69.1% a | 66.3% a | 66.3% a |

| Smell nice | 72.1% | 84.0% | 83.1% | 73.5% |

| High quality tobacco | 39.5% d | 40.0% d | 36.1% | 22.9% a,b |

| Not harsh tasting | 38.4% b,c | 58.8% a | 61.5% a | 49.4% |

| Not harmful to health | 8.1% | 10.0% | 9.6% | 10.8% |

| Typical user is… | ||||

| Masculine | 39.5% c | 48.2% c | 18.1% a,b,d | 33.7% c |

| Young | 62.8% c | 59.3% c | 79.5% a,b | 73.5% |

| Male (n=179) | ||||

| Wild Rush Encore a (n=44) |

Wild Rush Limited b (n=49) |

Twisted Berry c (n=43) |

Strawberry d (n=43) |

|

| This product looks… | ||||

| Taste good | 47.7% b | 69.4% a | 65.1% | 60.5% |

| Smell nice | 70.5% b | 87.8% a,d | 83.7% d | 65.1% b,c |

| High quality tobacco | 36.4% | 35.4% | 25.6% | 20.9% |

| Not harsh tasting | 38.6% | 52.1% | 55.8% | 44.2% |

| Not harmful to health | 6.8% | 10.4% | 14.0% | 9.3% |

| Typical user is… | ||||

| Masculine | 36.4% | 46.9% c | 18.6% b,d | 41.9% c |

| Young | 68.2% | 61.2% c | 81.4% b | 67.4% |

| Female (n=154) | ||||

| Wild Rush Encore a (n=42) |

Wild Rush Limited b (n=32) |

Twisted Berry c (n=40) |

Strawberry d (n=40) |

|

| This product looks… | ||||

| Taste good | 54.8% | 68.8% | 67.5% | 72.5% |

| Smell nice | 73.8% | 78.1% | 82.5% | 82.5% |

| High quality tobacco | 42.9% | 46.9% | 47.5% d | 25.0% c |

| Not harsh tasting | 38.1% b,c | 68.8% a | 67.5% a | 55.0% |

| Not harmful to health | 9.5% | 9.4% | 5.0% | 12.5% |

| Typical user is… | ||||

| Masculine | 42.9% c | 50.0% c,d | 17.5% a,b | 25.0% b |

| Young | 57.1% c,d | 56.3% d | 77.5% a | 80.0% a,b |

Note. Percentages report % of n responding “strongly agree” or “agree.”

Significant differences (p<.05) are indicated by superscripts, such that a rating with a superscript is significantly different with the rating for the product that has the corresponding superscript.

Overall, in Study 2, compared to “Island Madness,” participants rated “Boozy Watermelon” more favorably on several perceptions including tasting good, smelling nice, and being less harsh tasting (Table 2). Participants were also more likely to perceive “Boozy Watermelon” as being for younger users compared to “Island Madness,” and less likely to be typically used by masculine users. Female participants further perceived “Boozy Watermelon” to be less harmful to one’s health, compared to “Island Madness.”

Table 2.

Perceptions by Product, Study 2

| Overall (n=402) | Males (n=215) | Females (n=187) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | IM | p | BW | IM | p | BW | IM | p | |

| This product looks… | |||||||||

| Taste good | 70.7% | 60.7% | *** | 68.4% | 61.9% | * | 73.3% | 59.4% | *** |

| Smell nice | 79.9% | 68.9% | *** | 77.2% | 66.5% | *** | 82.9% | 71.7% | *** |

| High quality tobacco | 32.8% | 34.1% | n.s. | 31.6% | 32.1% | n.s. | 34.2% | 36.4% | n.s. |

| Not harsh tasting | 50.0% | 37.8% | *** | 46.5% | 34.0% | *** | 54.0% | 42.2% | ** |

| Not harmful to health | 6.5% | 5.0% | n.s. | 5.1% | 6.0% | n.s. | 8.0% | 3.7% | * |

| Typical user is … | |||||||||

| Masculine | 30.1% | 45.1% | *** | 34.6% | 46.7% | *** | 24.6% | 43.3% | *** |

| Young | 78.6% | 68.7% | *** | 77.2% | 67.4% | *** | 80.2% | 70.1% | *** |

Note. Percentages report % of n responding “strongly agree” or “agree.” BW = Boozy Watermelon; IM = Island Madness.

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001;

n.s. = nonsignificant difference in perceptions.

In Study 3, when presented with different versions of the “Wild Rush” packaging, participants rated the “Encore Edition” with the added explicit “watermelon fruit punch” flavor descriptor more favorably on smell and harshness of taste, compared to the “Encore Edition” with just the “Wild Rush” concept flavor, and more favorably on taste compared to the “Limited Edition” with just the “Wild Rush” concept flavor (Table 3). Participants also perceived the “Encore Edition” with the explicit flavor descriptor as being for younger users compared to the “Encore Edition” with just the concept flavor. Compared to both packages with only the concept flavor descriptor, fewer agreed that the “Encore Edition” with the explicit flavor descriptor was for masculine users. These differences were significant among female but not male participants.

Table 3.

Perceptions by Product by Condition, Study 3

| Condition 1: Encore-explicit flavor vs. Encore-concept flavor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=164) | Males (n=81) | Females (n=83) | |||||||

| Encore-E | Encore-C | p | Encore-E | Encore-C | p | Encore-E | Encore-C | p | |

| This product looks… | |||||||||

| Taste good | 62.8% | 57.3% | n.s. | 65.4% | 60.5% | n.s. | 60.2% | 54.2% | n.s. |

| Smell nice | 81.1% | 73.2% | * | 80.3% | 75.3% | n.s. | 81.9% | 71.1% | * |

| High quality tobacco | 34.2% | 33.5% | n.s. | 38.3% | 42.0% | n.s. | 30.1% | 25.3% | n.s. |

| Not harsh tasting | 49.4% | 33.5% | *** | 45.7% | 32.1% | ** | 53.0% | 34.9% | *** |

| Not harmful to health | 6.7% | 7.9% | n.s. | 4.9% | 3.7% | n.s. | 8.4% | 12.1% | n.s. |

| Typical user is… | |||||||||

| Masculine | 31.7% | 42.7% | ** | 44.4% | 51.9% | n.s. | 19.3% | 33.7% | ** |

| Young | 74.4% | 61.0% | *** | 77.8% | 65.4% | * | 71.1% | 56.6% | ** |

| Condition 2: Encore-explicit flavor vs. Limited-concept flavor | |||||||||

| Overall (n=171) | Males (n=93) | Females (n=78) | |||||||

| Encore-E | Limited-C | p | Encore-E | Limited-C | p | Encore-E | Limited-C | p | |

| This product looks… | |||||||||

| Taste good | 69.0% | 62.6% | * | 68.8% | 65.6% | n.s. | 69.2% | 59.0% | * |

| Smell nice | 73.7% | 72.5% | n.s. | 76.3% | 77.4% | n.s. | 70.5% | 66.7% | n.s. |

| High quality tobacco | 35.7% | 37.4% | n.s. | 33.3% | 38.7% | n.s. | 38.5% | 35.9% | n.s. |

| Not harsh tasting | 46.8% | 43.3% | n.s. | 45.2% | 45.2% | n.s. | 48.7% | 41.0% | n.s. |

| Not harmful to health | 11.7% | 11.1% | n.s. | 7.5% | 8.6% | n.s. | 16.7% | 14.1% | n.s. |

| Typical user is… | |||||||||

| Masculine | 38.0% | 48.0% | ** | 44.1% | 48.4% | n.s. | 30.8% | 47.4% | ** |

| Young | 81.3% | 76.6% | n.s. | 79.6% | 76.3% | n.s. | 83.3% | 76.9% | n.s. |

Note. E = explicit flavor; C = concept flavor; Percentages report % of n responding “strongly agree” or “agree.”

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001;

n.s. = nonsignificant difference in perceptions.

Purchase intentions for all three studies are found in Table 4. In Study 1, there were no significant differences in intentions to purchase the different products. In Study 2, while there were no differences in purchase intentions in the overall sample (mean intentions 2.57 vs. 2.50 for “Boozy Watermelon” and “Island Madness” respectively), female participants were more likely to purchase “Boozy Watermelon” compared to “Island Madness” (mean intentions 2.53 vs. 2.40, p<.05). Lastly, in Study 3, when participants were asked about their intentions to purchase each of the individual products, there were no significant differences across products. However, when participants were asked which of the two products (in their condition) they would be more likely to purchase, participants selected the “Encore Edition” with the explicit flavor descriptor more often than the “Encore Edition” with just the “Wild Rush” concept flavor (73.6% vs. 26.4%, p<.001), and less often than the “Limited Edition” with just the “Wild Rush” concept flavor (41.2% vs. 58.8%, p<.001).

Table 4.

Direct and Comparative Purchase Intentions across Three Studies

| Overall | Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Intentions | % (n) | M (SD) | p | % (n) | M (SD) | p | % (n) | M (SD) | p |

| Study 1 | |||||||||

| Wild Rush Encore | 19.8 (17) | 2.33 (1.18) | n.s. ‡ | 20.5 (9) | 2.34 (1.26) | n.s. ‡ | 19.1 (8) | 2.31 (1.12) | n.s. ‡ |

| Wild Rush Limited | 24.7 (20) | 2.47 (1.26) | 26.5 (13) | 2.55 (1.31) | 21.9 (7) | 2.34 (1.18) | |||

| Twisted Berry | 14.5 (12) | 2.19 (1.15) | 16.3 (7) | 2.28 (1.20) | 12.5 (5) | 2.10 (1.10) | |||

| Strawberry | 21.7 (18) | 2.36 (1.26) | 25.6 (11) | 2.53 (1.26) | 17.5 (7) | 2.18 (1.24) | |||

| Study 2 | |||||||||

| Boozy Watermelon | 28.1 (113) | 2.57 (1.31) | n.s. | 27.4 (59) | 2.60 (1.27) | n.s. | 28.9 (54) | 2.53 (.10) | .03 |

| Island Madness | 24.6 (99) | 2.50 (1.30) | 27.4 (59) | 2.59 (1.29) | 21.4 (40) | 2.40 (.10) | |||

| Study 3 | |||||||||

| Condition 1 | |||||||||

| Wild Rush Encore-E | 31.1 (51) | 2.74 (1.40) | n.s. | 34.6 (28) | 2.85 (1.30) | n.s. | 27.7 (23) | 2.62 (1.50) | n.s. |

| Wild Rush Encore-C | 26.8 (44) | 2.66 (1.37) | 30.9 (25) | 2.77 (1.28) | 22.9 (19) | 2.55 (1.46) | |||

| Condition 2 | |||||||||

| Wild Rush Encore-E | 19.9 (34) | 2.51 (1.20) | n.s. | 21.5 (20) | 2.61 (1.25) | n.s. | 18.0 (14) | 2.38 (1.14) | n.s. |

| Wild Rush Limited-C | 19.9 (34) | 2.46 (1.23) | 23.7 (22) | 2.61 (1.29) | 15.4 (12) | 2.28 (1.15) | |||

| Comparative Intentions | % (n) | p | % (n) | p | % (n) | p | |||

| Study 3 | |||||||||

| Condition 1 | |||||||||

| Wild Rush Encore-E | 73.6 (120) | <.001 | 66.3 (53) | <.001 | 80.7 (67) | <.001 | |||

| Wild Rush Encore-C | 26.4 (43) | 33.8 (27) | 19.3 (16) | ||||||

| Condition 2 | |||||||||

| Wild Rush Encore-E | 41.2 (70) | <.001 | 32.6 (30) | <.001 | 51.3 (40) | n.s. | |||

| Wild Rush Limited-C | 58.8 (100) | 67.4 (62) | 48.7 (38) | ||||||

Note. E = explicit flavor; C = concept flavor; n.s. = nonsignificant differences;

= nonsignificant differences in intentions across all comparisons.

For direct purchase intentions, percentages report % of n responding “certain or practically certain” or “probable.” For comparative purchase intentions, percentages represent those who made the corresponding selection in response to the question: “Which of the two would you be more likely to buy?”

DISCUSSION

This series of complementary studies contributes to the limited literature on the impact of cigarillo packaging and descriptors, finding that features such as flavor descriptors, promotional descriptors (“Limited Edition”), and color can impact cigarillo product perceptions and appeal. These findings have several policy and regulatory implications.

When comparing cigarillo packs with similar packaging colors (as in Studies 1 and 3), we found that packs with explicit flavor descriptors were more frequently perceived as being less harsh, smelling nice, and tasting good, building on previous findings15 that showed fictitious cigarillo packs with a flavor descriptor were rated more favorably on product taste and smell than packs with no flavor descriptor. This is significant given that these sensory-related expectancies were based solely on briefly viewing an image of the pack. Notably, across all studies, packages with explicit flavor descriptors were also perceived by young adult participants as typically being used by young people. Together these findings further support policy efforts to ban and restrict flavored tobacco products generally, and cigarillos specifically, to reduce product appeal and use among young people.

It is worth noting, however, that even packs presented without explicit flavor descriptors still received high favorable ratings for sensory/satisfaction features (tasting good, smelling nice, being less harsh) and were frequently perceived as typically used by young people. Given that these products included a concept descriptor (“Wild Rush”) that did not clearly communicate any flavor or taste attributes, these perceptions are likely influenced in large part by the attractive packaging colors and designs. The importance of these features may be underscored in point-of-sale settings where consumers, including young people, make tobacco selections from large visible displays.20

Furthermore, our findings also suggest that packaging color may have differential appeal with different consumers, also consistent with previous research.15 16 In Study 2 we found that, despite having the same “watermelon rum” flavor descriptor on the packages, participants perceived the tan-colored “Island Madness” style as being typically for male users compared to the green and pink-colored “Boozy Watermelon” style, and “Boozy Watermelon” was more frequently perceived as typically being for young users compared to “Island Madness.” “Boozy Watermelon” was also perceived more favorably in terms of taste, smell and harshness compared to “Island Madness.” Importantly, we also observed that ratings and appeal for “Boozy Watermelon” were more favorable among female study participants compared to male participants, further illustrating the potential for differential appeal to different subgroups. These differences may relate to both packaging color, as well as the explicit and implicit references to a fruit and alcohol in the name “Boozy Watermelon.”

These case study findings have implications for cigarillo packaging features’ impact on product appeal in general, and for US regulation and evaluation of cigar products introduced after February 15, 2007 – i.e., products not grandfathered. (We recognize that the term “grandfathered” has disturbing historical roots that date back to the Reconstruction era; however, we use this term because FDA has assigned a specific meaning to it in this context21). So-called grandfathered products are exempt from the FDA’s marketing authorization process. In order to stay on the market, applications to the FDA for cigar products introduced between the 2007 grandfather date and August 8, 2016 needed to be submitted (by September 9, 2020) in the form of either: 1) Premarket Tobacco Product Applications for any products considered to be “new” (applications which must demonstrate that the product’s introduction would be beneficial for public health); or 2) as “Substantial Equivalence” (SE) applications.22 Because cigars are combustible and pose health risks comparable to cigarettes,23 SE applications present the most likely path for cigar products to stay on the market after September 2020. A successful application must demonstrate that the product under review has the same characteristics as a “grandfathered” predicate product, or if the product has different characteristics, must demonstrate that the new product “does not raise different questions of public health” than the predicate product.22 It is possible that brands such as Swisher Sweets, with a long history of flavored cigarillo marketing, could try to equate some of their recent styles to earlier styles with the same or similar flavor (e.g., claiming that a product like “Wild Rush” is substantially equivalent to some other watermelon style on the market before 2007). However, results of this study suggest that different cigarillo packaging features, including colors and descriptors, can influence product perceptions and appeal (including differential appeal by age and gender), and therefore that such differences can arguably “raise different questions of public health.” Thus, packaging features and descriptors should also be considered with respect to regulation of cigarillo products.

We generally found few differences in purchase intentions across the studies, which may have been influenced by the somewhat subtle differences across conditions. However, we did observe some interesting preliminary findings with respect to packs using the promotional descriptor “Limited Edition.” In Study 3, participants viewed two versions of “Wild Rush” packs with similar pack color and design features but different descriptors, and were asked to choose which they would be more likely to buy. As might be expected, participants were more likely to want to buy the “Wild Rush Encore Edition” which included an explicit watermelon flavor descriptor compared to a similar “Wild Rush Encore Edition” pack with no explicit flavor descriptor. However, they were less likely to want to buy the “Wild Rush Encore Edition” with the explicit watermelon flavor compared to the ‘Wild Rush Limited Edition” style, even though this style had no explicit flavor description. It is possible that the “Limited Edition” descriptor confers the products with an additional sense of desirability and sense that consumers need to buy it now before it is unavailable, and that this can drive appeal as much as, or even more than, an explicit flavor descriptor. Future research should continue to examine the use of this descriptor in cigar packaging.

Strengths and Weaknesses

One of the strengths of these studies is the relatively high level of external validity, which we were able to obtain by examining the natural variations that existed in real Swisher Sweets packaging. However, given that we were examining cigarillos that were in the market, participants’ awareness of these products or preference for the Swisher brand could have resulted in pre-existing perceptions and intentions. Other limitations of these study designs are that we cannot separate effects of product descriptors and color/pack design elements, and we only featured packs from one brand. Pack stimuli used in the current studies also did not feature warning labels, which could influence cigarillo pack appeal and product perceptions and interest as well.15 24 In addition, while we included a proxy measure for perceived product appeal to youth, we did not directly compare appeal among younger versus older participants. However, findings from these exploratory studies can contribute to refined hypothesis generation for future experiments. Finally, included studies were conducted with convenience samples of young adults; however, MTurk has been shown to provide experimental results comparable to national probability samples,25 and our sample sizes and triangulation of three studies further increase confidence in the pattern of results.

In conclusion, cigarillo packaging features including flavored descriptors, promotional descriptors, and packaging colors can impact product perceptions and appeal. Variations in the packaging of products with the same flavor may have differential appeal with different consumers in ways that raise “new or different” questions of public health.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Prior research shows tobacco product packaging features such as color and flavor descriptors influence perceptions about the product, and ultimately use intentions.

However, there is limited research on cigar packaging; the few experimental studies that do exist rely on manipulated images of cigar packs.

Findings across three different studies using real-world cigarillo packaging images showed that packaging impacted perceptions of taste, harshness, and preferred user, even when the flavor was identical.

Findings further showed that packaging could have differential appeal and lead to varying purchase intentions between men and women.

Acknowledgements

Images were retrieved from public online sources and used in this paper in accordance with the guidelines of Fair Use.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) under U54CA229973. MJ was additionally supported by funding from NCI (K01CA242591) and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (P30CA072720-5931).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved all research procedures for this study.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rostron BL, Cheng Y-C, Gardner LD, et al. Prevalence and reasons for use of flavored cigars and ends among us youth and adults: estimates from Wave 4 of the PATH Study, 2016–2017. Am J Health Behav 2020;44(1):76–81. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.44.1.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Miller Lo EJ. Changes in the mass-merchandise cigar market since the Tobacco Control Act. Tobacco Regulatory Science 2017;3(2):8–16. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.2(Suppl1).2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L-L, Baker HM, Meernik C, et al. Impact of non-menthol flavours in tobacco products on perceptions and use among youth, young adults and adults: a systematic review. Tob Control 2017;26(6):709–19. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterling KL, Fryer CS, Nix M, et al. Appeal and impact of characterizing flavors on young adult small cigar use. Tobacco Regulatory Science 2015;1(1):42–53. doi: 10.18001/TRS.1.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riell H Cigars Hot for Now. CStore Decisions 2019. https://cstoredecisions.com/2019/02/11/cigars-hot-for-now/ (accessed December 20 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gammon DG, Rogers T, Coats EM, et al. National and state patterns of concept-flavoured cigar sales, USA, 2012–2016. Tob Control 2019;28(4):394–400. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganz O, Hrywna M, Schroth KRJ, et al. Innovative promotional strategies and diversification of flavoured mass merchandise cigar products: a case study of Swedish match. Tob Control 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056145 [published Online First: Feb 1 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip Morris USA v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2016) 202 F. Supp.3d 31, 36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond D, Parkinson C. The impact of cigarette package design on perceptions of risk. Journal of Public Health 2009;31(3):345–53. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan J, et al. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11(suppl 1):i73–i80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufman AR, Persoskie A, Twesten J, et al. A review of risk perception measurement in tobacco control research. Tob Control 2020;29(Suppl 1):s50–s58. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avishai A, Meernik C, Goldstein AO, et al. Impact and mechanisms of cigarillo flavor descriptors on susceptibility to use among young adult nonusers of tobacco. J Appl Soc Psychol 2020;50(12):699–708. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong G, Cavallo DA, Bold KW, et al. Adolescent and young adult perceptions on cigar packaging: a qualitative study. Tobacco regulatory science 2017;3(3):333–46. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.3.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meernik C, Ranney LM, Lazard AJ, et al. The effect of cigarillo packaging elements on young adult perceptions of product flavor, taste, smell, and appeal. PLoS One 2018;13(3):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans AT, Wilhelm J, Abudayyeh H, et al. Impact of package descriptors on young adults’ perceptions of cigarillos. Tobacco Regulatory Science 2020;6(2):118–35. doi: 10.18001/TRS.6.2.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delnevo CD, Jeong M, Ganz O, et al. The effect of cigarillo packaging characteristics on young adult perceptions and intentions: an experimental study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(8):4330. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowitt SD, Meernik C, Baker HM, et al. Perceptions and experiences with flavored non-menthol tobacco products: a systematic review of qualitative studies. 2017;14(4):338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juster FT. Consumer buying intentions and purchase probability: an experiment in survey design. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1966;61(315):658–96. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1966.10480897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiction 2008;103(2):322–28. doi: doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration. Grandfathered Tobacco Products [updated June/17/2020. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/market-and-distribute-tobacco-product/grandfathered-tobacco-products accessed May 10 2021.

- 22.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. 2009. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf (accessed 20 Dec 2020).

- 23.Chang CM, Corey CG, Rostron BL, et al. Systematic review of cigar smoking and all cause and smoking related mortality. BMC Public Health 2015;15(1):390. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1617-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nonnemaker JM, Pepper JK, Sterling KL, et al. Adults’ visual attention to little cigar and cigarillo package warning labels and effect on recall and risk perceptions. Tobacco Regulatory Science 2018;4(6):47–56. doi: 10.18001/TRS.4.6.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong M, Zhang D, Morgan JC, et al. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann Behav Med 2019;53(5):476–85. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]