Abstract

This study examined associations between structural racism, anti-LGBTQ policies, and suicide risk among young sexual minority men (SMM). Participants were a 2017–2018 internet-based U.S. national sample of 497 Black and 1,536 White SMM (ages 16–25). Structural equation modeling tested associations from indicators of structural racism, anti-LGBTQ policies, and their interaction to suicide risk factors. For Black participants, structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies were significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms, heavy drinking, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, self-harm, and suicide attempt. There were significant interaction effects: positive associations between structural racism and several outcomes were stronger for Black participants in high anti-LGBTQ policy states. Structural racism, anti-LGBTQ policies, and their interaction were not significantly associated with suicide risk for White SMM.

Keywords: Black Sexual Minority Youth, Structural Racism, Anti-LGBTQ policies, Intersectional Stigma, Health Inequities, Suicidality, Suicide Risk, Minority Stress

After a year in which the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed stark inequities in the U.S. (Bowleg, 2020; Millett et al., 2020a; Millett et al., 2020b; Poteat, Millett, Nelson, & Beyrer, 2020), it may be magnifying a disturbing trend in suicide rates over the past decade (Bray et al., 2020): Black U.S. American youth are dying from suicide at faster rates than any other U.S. racial/ethnic youth groups (Congressional Black Caucus, 2019). Critically, this trend appears to be inequitably pronounced among young Black sexual minority boys and men (SMM; Mueller, James, Abrutyn, & Levin, 2015) for whom bullying victimization and suicidality is two to six times higher than their heterosexual counterparts (Mueller, James, Abrutyn, & Levin, 2015; O’Donnell, Meyer, & Schwartz, 2011). Despite these alarming trends, there is a paucity of research examining structural explanations and solutions to the rising tide of suicide among young Black SMM. In particular, although these youth face structurally racist and anti-LGBTQ oppression, there are few studies that examine the effects of this oppression on suicidality among young Black SMM (American Psychological Association & APA Working Group on Health Disparities in Boys and Men, 2018; Wade & Harper, 2015), and none, to our knowledge, that investigate the compounding, intersectional effects of both structural racist and anti-LGBTQ oppression. As a result, there is little evidence and impetus for structural public health interventions designed to enact profound and sustained reductions in suicide among young Black SMM. To address this gap in the literature and identify structural targets for suicide intervention for young Black SMM, the present study examines independent and conjoint associations between indicators of U.S. state-level structural racism, anti-LGBTQ policies, and suicide risk outcomes among a national sample of adolescent and emerging adult Black and White SMM.

Theoretical Foundation

U.S.-based structural oppression is rooted in cultural ideologies (i.e., White supremacy, heterosexism) and interconnected institutions (e.g., law enforcement, local governments) that systematically label and marginalize Black and sexual minority communities (Bowleg, 2013; Carmichael, Ture, & Hamilton, 1992; Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Delgado & Stefancic, 2017; Jagose, 1996; Link & Phelan, 2001). Structural oppression is distinct from individual-level oppression in that it is enacted through systems (e.g., interconnected laws and policies) on an aggregate level, rather than solely through the actions of individuals who possess power and prejudice (Feagin, 2013). Intersectionality frameworks provide a lens through which to conceptualize and critically examine this structural oppression (Bowleg, 2012; Caucus, 2019; Collins, 2002; Crenshaw, 1989). A central posit of intersectionality is that, through factors that operate at the social-structural level, multiple interlocking systems of oppression (e.g., racism, heterosexism, ageism) produce and exacerbate social, economic, and health inequalities at intersecting social positions (e.g., race and gender and sexual identity and age). Examples of structurally racist and LGBTQ oppression include policies and practices that perpetuate disproportionate rates of homelessness among Black LGBTQ youth (e.g., zero protections for LGBTQ youth of color accessing homeless youth services; Choi, Wilson, Shelton, & Gates, 2015; Quintana, Rosenthal, & Krehely, 2010; Waguespack & Ryan, 2019 ) and those that increase the likelihood of Black LGBTQ youth disproportionately being forced into the carceral system (Hunt & Moodie-Mills, 2012; McCandless, 2018; Snyder et al., 2016). Examining policies that perpetuate intersecting systems of oppression allows for nuanced and critical examinations of factors that adversely affect psychological well-being at the individual-level and translate into increased stress at the community- and population-levels (Clark et al., 1999; Hatzenbuehler, 2016; Link & Phelan, 2001). These effects of structural oppression may be particularly important during the critical period of adolescence and young adulthood when youth may be at heightened vulnerability to oppression-related stress and the life-long effects it can cause (Gee, Hing, Mohammed, Tabor, & Williams, 2019; Trent, Dooley, & Dougé, 2019). Accordingly, current best practice recommendations for population research assert that sources of structural oppression are important drivers of health inequities among communities like young Black SMM and affirm the need for intersectionality-informed research that examines how structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies jointly contribute to psychological health inequities like suicidality (Agénor, 2020; Bauer, 2014; del Río-González, Holt, & Bowleg, 2021).

Individual-level Oppression and Suicidality Research

Despite a clear need, the vast majority or research examining suicidality among Black youth and SMM focuses on individual-level stressors and outcomes associated with suicide risk (Opara et al., 2020). For example, a study examining individual suicide risk factors among Black, Latinx, and multiracial SMM adults showed that individual-level racial and heterosexist stigma interact to predict depressive symptoms and heavy drinking (English, Rendina, & Parsons, 2018). Additionally, studies of suicidal ideation have found that interpersonal discrimination is associated with higher odds of suicidal ideation among Black youth across gender and ethnicity (Assari, Moghani Lankarani, & Caldwell, 2017) and that the association between racial discrimination and suicidality is mediated by anxiety symptoms for young Black boys (Walker et al., 2017). Another study with Black sexual minority adolescents found interpersonal racist and antigay discrimination are separately, but not conjointly, positively associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation for these youth (Thoma & Huebner, 2013). Other research has highlighted that Black sexual minority adolescents are more likely to report suicidal attempt, but not ideation, compared with White sexual minority adolescents (Baiden, LaBrenz, Asiedua-Baiden, & Muehlenkamp, 2020). Recent evidence suggests that suicide attempt rates among Black sexual minority young adults may be driven by sexual minority discrimination, with the strongest associations between sexual minority discrimination and suicide attempt between 18–25 years old (Layland, Exten, Mallory, Williams, & Fish, 2020).

This valuable evidence notwithstanding, there are two important gaps in the research: a lack of research examining associations between oppression and interpersonal risk factors of suicidality, and a lack of structural oppression research. For instance, despite evidence for the critical social impacts of oppression (Feagin, 2013; Hatzenbuehler, 2016), there is a dearth of evidence on the impact of oppression on interpersonal risk factors for suicide among young Black SMM (Opara et al., 2020).

Oppression and Interpersonal Risk Factors of Suicide

The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Chu et al., 2017; Joiner et al., 2009) puts forth two interpersonal risk factors, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomenss, as proximal causes of suicide ideation, and may be a useful framework for understanding suicide risk among young Black SMM. At the core of this theory is the assumption that humans have a fundamental need to belong. When this need is unmet (i.e., thwarted belongingness) and when inviduals perceive their life to be a burden on others (i.e., perceived burdensomeness), risk of suicide ideation increases. Individuals are likely to shift from passive suicidal ideation to active ideation and suicide attempt when they experience hopelessness that their social connectedness will change (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Additionally, likelihood of attempt and lethality of attempt are theorized to increase based on one’s capacity for inflicting self-injury.

Few studies have examined thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as risk factors for suicide among SMM. The limited research suggests that sexual minorities experience higher rates of perceived burdensomeness compared to the general population due to stigma associated with their sexual orientation (Hill & Pettit, 2012; Pate & Anestis, 2020). Despite some evidence highlighting the elevated risk of social isolation experienced by SMM, suicide research has not demonstrated differences in rates of thwarted belongingness among SMM compared to the general population. Moreover, while perceived burdensomeness has consistently been shown to be linked to suicidal ideation among sexual minority communities, thwarted belongingness is not associated with suicidal ideation in these studies (Baams, Grossman, & Russell, 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Ploderl et al., 2014; Woodward, Wingate, Gray, & Pantalone, 2014). Despite some evidence highlighting associations between individual-level oppression (i.e., experienced harassment and discrimination, internalized stigma) and elevations in thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Baams et al., 2015; Ploderl et al., 2014), studies involving young Black SMM have yet to examine the impact of structural stigma on interpersonal risk factors for suicide. As a result, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding about interpersonal pathways to suicide among young Black SMM.

Structural Oppression and Youth Suicidality

With regard to structural oppression research, this burgeoning body of empirical studies focuses primarily on associations between negative psychological outcomes and structural oppression based upon single axes of identity among youth (e.g., sexual identity alone; Hardeman, Murphy, Karbeah, & Kozhimannil, 2018; Hatzenbuehler, 2016), rather than the mutually reinforcing effects of structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies. For example, extant studies examining the effects of anti-LGBTQ policies (e.g., restrictions on the inclusion of LGTBQ topics in schools; permission of conversion therapy) among sexual minority youth have demonstrated associations between U.S. state-level oppression among predominantly White sexual minority communities and suicide risk factors, including substance use (Hatzenbuehler, Jun, Corliss, & Bryn Austin, 2015), including heavy drinking (Drabble, Mericle, Gómez, Klinger, Trocki, & Karriker-Jaffe, 2021) and suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts (Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage, 2019; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013; Raifman, Moscoe, Austin, & McConnell, 2017; Barnett et al., 2019). Conversely, recent evidence suggests that LGBTQ-affirmative policies are associated with lower anxiety and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth (Colvin, Egan, & Coulter, 2019). Other studies with SMM adults have reported links between anti-LGBTQ policies and psychological distress (Raifman, Moscoe, Austin, Hatzenbuehler, & Galea, 2018), generalized anxiety disorder (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hasin, 2009), and post-traumatic stress disorder (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). More recently, studies have found that the intersection of anti-LGBTQ and structurally anti-immigrant and racist policy environments are associated with worse psychological and HIV-related outcomes among SMM (English et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2017).

The relatively nascent literature investigating associations between structural racism and health among Black communities has predominantly focused on adults and physiological outcomes (Hardeman et al., 2018). For instance, studies have found links between state- and county-level structural racism (e.g., White-Black inequities in housing, education, and incarceration) and racial inequities in fatal police shootings (Mesic et al., 2018), access to health care (Leitner, Hehman, Ayduk, & Mendoza-Denton, 2016), myocardial infarction (Lukachko, Hatzenbuehler, & Keyes, 2014), adverse birth outcomes (Wallace, Mendola, Liu, & Grantz, 2015), body mass index (Dougherty, Golden, Gross, Colantuoni, & Dean, 2020), and circulatory disease-related deaths (Leitner et al., 2016) among Black U.S. Americans. Despite this valuable evidence, we are unaware of any research examining state-level structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies as independent and synergistic drivers of current trends in suicide risk among young Black SMM. This is a critical gap in the science given emerging evidence indicates that the period from adolescence to young adulthood may be a critical period in which oppression has a heightened immediate and lifelong impact on the psychological health of Black youth (Trent et al., 2019). This is consistent with research showing that suicide inequities among Black and SMM youth develop during adolescence and young adulthood (Fish, Rice, Lanza, & Russell, 2019; Lindsey, Sheftall, Xiao, & Joe, 2019). As such, it is essential that studies of oppression and suicidality are focused on this developmental period among young Black SMM.

Current Study

To contribute to stemming the rise of suicidality among young Black SMM in the U.S. by identifying opportunities for structural intervention, we tested associations from state-level indicators of structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies to individual suicide risk factors (e.g., depressive symptoms, heavy drinking), interpersonal suicide risk factors (e.g., perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness), and suicidality (e.g., suicidal ideation, self-harm, suicide attempt). Given evidence that structural racism has null or positive effects for White communities (Lukachko et al., 2014), but negative health impacts within Black communities (Hardeman et al., 2018), we hypothesized that structural racism would be positively associated with all risk factors only for young Black SMM. In line with studies evincing the harmful psychological and behavioral effects of anti-LGBTQ policies for SMM (Hardeman et al., 2018; Hatzenbuehler, 2016), we hypothesized that there would be positive associations between anti-LGBTQ policies and suicide risk among all participants. We also hypothesized, consistent with the intersectionality framework (Bowleg, 2012; Collins, 2002; Crenshaw, 1989) and empirical research that supports it (e.g., Jackson-Best & Edwards, 2018; Quinn, Bowleg, & Dickson-Gomez, 2019), that structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies would have compounding effects, such that young Black SMM living in states with high levels of both forms of oppression would show exponentially higher levels of suicide risk factors than young Black SMM living in other states. Finally, we conducted an exploratory age moderation analysis to determine whether associations between structural oppression variables and suicide risk outcomes varied across age.

Method

The study’s sample draws from the baseline data of Understanding New Infections through Targeted Epidemiology study (UNITE), a national longitudinal cohort study with SMM to better understand risk factors for HIV infection (Rendina et al., 2021). Recruitment and data collection occurred from 2017–2018. The study team recruited a non-random purposive sample through advertisements on geosocial networking apps (e.g., Adam4Adam), social media sites (e.g., Black Gay Chat), and email blasts. Interested respondents completed a brief online screener that assessed eligibility criteria including: being at least 16 years old; identifying as male (including transgender men); not reporting heterosexual identity; reporting HIV negative or unknown status; reporting using any app to find sex partner(s) and sexual HIV risk in the past 6 months. Additional information on eligibility criteria can be found in the UNITE methods manuscript (Rendina et al., 2021).

Following the screener, participants provided informed consent online and completed an online survey assessing stress, psychosocial variables, and HIV risk. Participants received a $25 gift card for completing the baseline survey. The City University of New York Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Participants

In total, 3,982 Black SMM and 11,616 White SMM were eligible to participate in the UNITE study and provided contact information. Of these, 1,439 (36.1%) Black and 5,656 (48.7%) White SMM completed the enrollment survey. The analytic sample consisted of the 497 Black and 1,536 White SMM participants who identified as non-Hispanic, non-multiracial Black/African American (n=1,439) or White only (n=5,656), had a state racism index score because they did not live in Washington DC or Puerto Rico (nBlack=1,422; nWhite=5,260), were less than or equal to 25 years old (nBlack=500; nWhite=1,548), and did not have missing data for any model covariates (nBlack=497; nWhite=1,536). We excluded cases missing on covariates because estimating them as endogenous in our models would have imposed a distributional assumption of normality (Marcoulides & Schumacker, 1996), which was untenable for categorical (e.g., income) and positively skewed (e.g., age) covariates. Participants excluded for covariate missingness did not significantly differ on any primary study variables from those included.

Measures

Sociodemographics

Participants reported sociodemographic information including: subjective social status (Adler & Stewart, 2007), income, formal employment status, housing instability, age, sexual identity, relationship status, living situation (i.e., living alone, living with parents), whether participants have living parents/stepparents and are in contact with them, insurance coverage, and military experience. We calculated a dichotomous Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA; U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2019) measure of rural-urban classification and commuting using participant addresses.

Structural Racism

The State Racism Index assesses structural racism, a metric created to capture U.S. state-level racism on a scale from 0–100 across these dimensions: residential segregation, incarceration rates, educational attainment, economic indicators, and employment status (Mesic et al., 2018). Composite scores across dimensions ranged from 25.9 to 74.9, with higher values indicating more racism. The state racism index is available for 50 states, excluding Washington DC and Puerto Rico. Additional information on the calculation and validity of this variable is available in its original publication (Mesic et al., 2018).

Anti-LGBTQ Policies

The Human Rights Campaign’s 2018 State Equality Index (SEI) (Warbelow, Oakley, & Kutney, 2018) measured anti-LGBTQ policies. The SEI is based on statewide anti-LGBTQ policies (e.g., HIV/AIDS criminalization; permitting hate crimes, conversion therapy, and discrimination in education; no anti-bullying protections in schools). The SEI groups states into four categories where lower values indicate more anti-LGBTQ policies (1=high priority to receive basic equality - 4=working toward innovative equality). Because over 94% of participants were in states that received the highest or lowest score, we dichotomized the scale. All model estimates in the results are reversed for interpretability.

Depressive Symptoms

Participants completed the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D)-10 (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Response options ranged from 0 (Rarely or none of the time) to 3 (Most or all of the time). Consistent with past research on the CES-D-10’s factor structure (Zhang et al., 2012), models included subscale means across negative (depressed) affect and reverse-scored positive affect subscales. Models included subscale means as indicators of a depressive symptoms latent variable. The scale showed good internal consistency (α=0.85).

Heavy Drinking

The 3-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) assessed heavy drinking (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). Each item has a unique 5-point scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of heavy drinking. Consistent with past research showing meaningful variation in drinking problems across the composite of the three AUDIT-C items (Rubinsky, Dawson, Williams, Kivlahan, & Bradley, 2013) models included a summed continuous outcome. The scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α=0.78).

Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire assessed perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). As measured, both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness associate with feelings of loneliness and suicide among general populations (Van Orden et al, 2012). Response options ranged from 1 (not at all true for me) to 7 (very true for me). Models included the perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness subscores as latent variables with 6 and 9 categorical item indicators, respectively. The subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α=0.94; perceived burdensomeness; α=0.89; thwarted belongingness).

Suicidality

The Self-Harm Questionnaire assessed suicidal ideation, self-harm behaviors, and suicide attempt history (Rendina et al., 2020). Response options for these items were dichotomous, with yes/no responses. Models included a latent variable with two suicidal ideation indicators: single items assessing recent passive suicidal ideation (“In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?”) and past-week active suicidal ideation (“In the past week, have you been having thoughts of killing yourself?”); a single item assessing past-year self-harm ( “In the past 12 months, have you ever hurt yourself on purpose?”); and a single item assessing lifetime suicide attempts (“Have you ever tried to kill yourself?”).

Analysis Plan

We used structural equation modelling (SEM) within Mplus 8.7 to test multiple associations simultaneously while accounting for measurement error (Kaplan, 2001). We estimated confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to assess latent depressive symptoms, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation variables. We assessed the appropriateness of models using accepted model fit indices including chi-square, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Independent but equivalent models for Black and White SMM youth assessed hypothesized pathways in SEM, and we compared the strength of those pathways across models using a multigroup analysis and chi-square difference test between a freely estimated model and model with hypothesized pathways constrained to be equal across groups (i.e., Mplus DIFFTEST command; Asparouhov, Muthén, & Muthén, 2006). Models included main and interaction effects of the continuous structural racism and dichotomous anti-LGBTQ policies variables on depressive symptoms, heavy drinking, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, suicidal ideation, self-harm, and suicide attempt. Models included an interaction term between the centered structural racism variable and the anti-LGBTQ policies variable. In separate exploratory models, we examined age moderation with a centered continuous age variable, including structural racism/anti-LGBTQ x age interactions and a three-way structural racism x anti-LGBTQ policies x age interaction. All models adjusted for theoretically meaningful contextual and individual covariates (i.e., rural-urban classification, subjective SES, income, formal employment status, housing instability, age, sexual identity, relationship status, living situation, whether participants have living parents/stepparents and are in contact with them, insurance coverage, and military experience). Models specified the manifest anxiety latent variable indicators as ordinal and used a variance-adjusted weighted least mean squares estimator. We clustered observations by state using the CLUSTER command to adjust standard errors and chi-square statistics that result from non-independence linked to nesting within geographic area. To aid in interpretting of interactions, we produced graphs and simple slopes using the PLOT and MODEL CONSTRAINT commands at high and low anti-LGBTQ policies for the 2-way interactions and 1SD above and below mean age for 3-way interactions. All data were complete other than income (97%; participants below 18 did not receive this item), heavy drinking (97%), perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (96%), depressive symptoms (90%), and suicidality variables (89%). We used full information maximum likelihood estimation to account for missing data under the assumption they were missing at random (Willett, Sayer, Schumacher, & Marcoulides, 1996), which was tenable given missingness patterns were not associated with our independent variables and there was no reason to expect systematic differences in our dependent variables based on missingness patterns (Bhaskaran & Smeeth, 2014).

Results

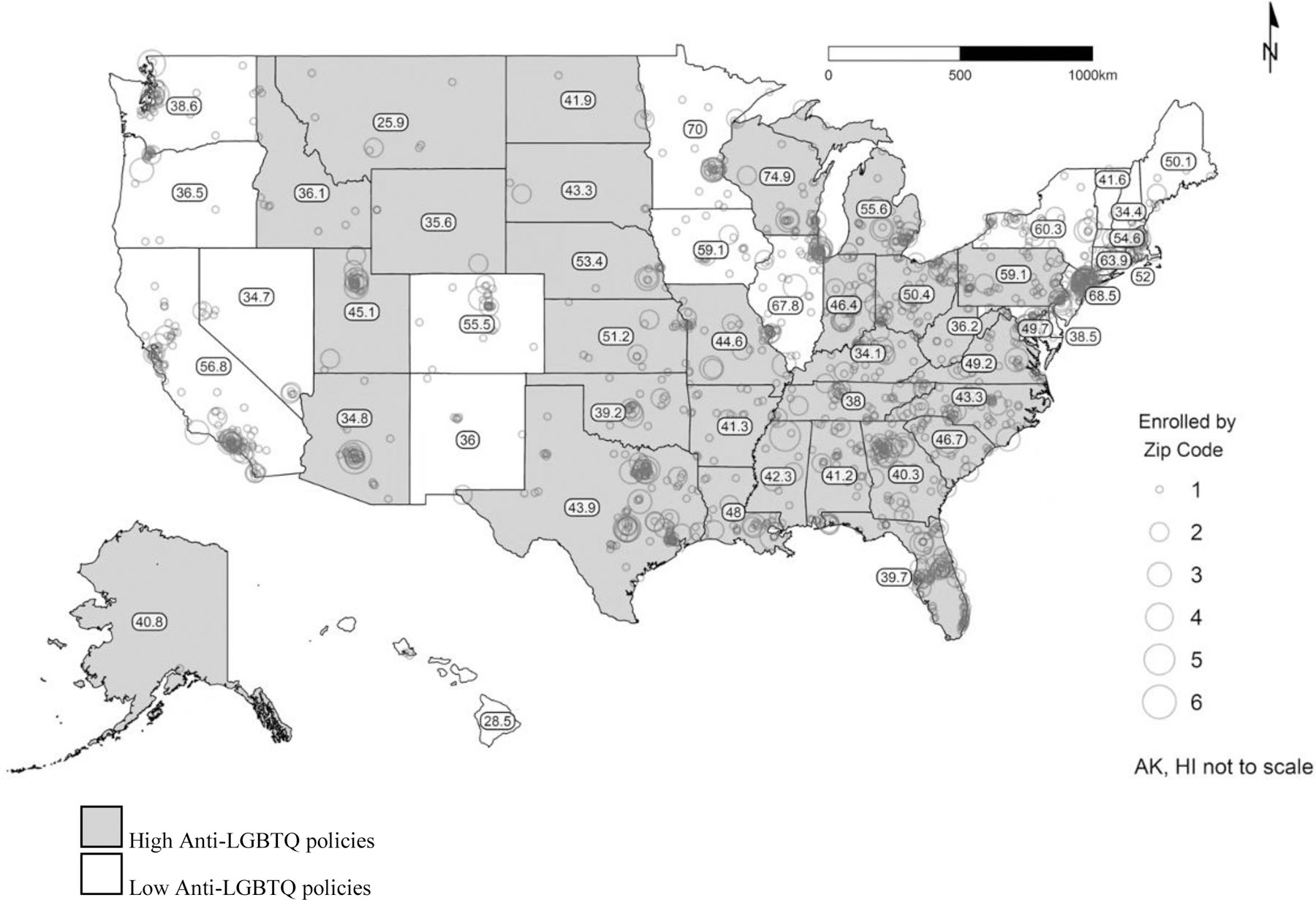

Table 1 includes the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics. Most participants were gay-identified (80%), cisgender (98%), and living with others (81%). Figure 1 depicts the national distribution of the sample and the structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies scores by state. Correlations and descriptives among model variables are in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample

| Total (n=2,033) | Black Men (n=497) | White Men (n=1,536) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Sexual Identity | χ2(2) =37.84, p < .01 | |||||

| Gay | 1,624 | 79.9 | 355 | 71.4 | 1,269 | 82.6 |

| Queer | 71 | 3.5 | 15 | 3.0 | 56 | 3.6 |

| Bisexual | 338 | 16.6 | 127 | 25.6 | 211 | 13.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Gender Identity | χ2(3) =4.79, p < .19 | |||||

| Cisgender man | 2,001 | 98.4 | 495 | 99.6 | 1,506 | 98.0 |

| Transgender man | 32 | 1.6 | 2 | .4 | 30 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Formal Educational Attainment | χ2(3) =30.86, p <.01 | |||||

| High school diploma, GED, or less | 492 | 242 | 143 | 28.8 | 349 | 22.7 |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 1,072 | 52.7 | 283 | 56.9 | 789 | 51.4 |

| 4-year college degree | 394 | 19.4 | 63 | 12.7 | 331 | 21.5 |

| Graduate school | 75 | 3.7 | 8 | 1.6 | 67 | 4.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Formal Employment Status | χ2(2) =10.16, p < .01 | |||||

| Unemployed, student, disability | 421 | 20.7 | 125 | 25.2 | 296 | 19.3 |

| Part-time (<40 hours/week) | 707 | 34.8 | 176 | 35.4 | 531 | 34.6 |

| Full-time (40+ hours/week) | 905 | 44.5 | 196 | 39.4 | 709 | 46.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Income | χ2(3) 10.22, p < .02 | |||||

| < $20,000 | 1,166 | 57.4 | 301 | 60.6 | 865 | 56.3 |

| $20,000-$49,000 | 670 | 33.0 | 163 | 32.8 | 507 | 33.0 |

| $50,000-$74,000 | 97 | 4.8 | 18 | 3.6 | 79 | 5.1 |

| ≥$75,000 | 37 | 1.8 | 2 | .4 | 35 | 2.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Subjective Social Status | χ2(9) =41.31, p < .01 | |||||

| 1–2 | 61 | 3 | 21 | 4.2 | 40 | 2.6 |

| 3–4 | 421 | 20.7 | 109 | 21.9 | 312 | 20.3 |

| 5–6 | 835 | 41 | 218 | 43.9 | 617 | 40.2 |

| 7–8 | 648 | 31.9 | 134 | 26.9 | 514 | 33.4 |

| 9–10 | 68 | 3.3 | 15 | 3.0 | 53 | 3.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Military Status | χ2(5) = 5.67, p <.34 | |||||

| No | 1,958 | 96.3 | 475 | 95.6 | 1,483 | 96.5 |

| Yes | 75 | 3.6 | 22 | 4.4 | 53 | 3.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Housing Instability | χ2(1) = .09, p < .77 | |||||

| No | 1,783 | 87.7 | 434 | 87.3 | 1,349 | 87.8 |

| Yes | 250 | 12.3 | 63 | 12.7 | 187 | 12.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Relationship Status | χ2(1) =.53, p = .47 | |||||

| Single | 1,663 | 81.8 | 412 | 82.9 | 1,251 | 81.4 |

| Partnered | 370 | 18.2 | 85 | 17.1 | 285 | 18.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Living Parents/Stepparents | χ2(1) =7.69, p < .01 | |||||

| No | 151 | 7.4 | 51 | 10.3 | 100 | 6.5 |

| Yes | 1,882 | 92.6 | 446 | 89.7 | 1,436 | 93.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Living Situation | χ2(3) =11.28, p < .01 | |||||

| Alone | 379 | 18.6 | 82 | 16.5 | 297 | 19.3 |

| With others | 1,654 | 81.4 | 415 | 83.5 | 1,239 | 80.7 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | t(2,031) = −6.0, p < .55 | |||||

| (Range: 9, Mdn= 20) | 22.03 | 2.303 | 22.03 | 2.303 | 21.96 | 2.333 |

|

| ||||||

| Rural-urban classification | t(2,031) = 4.15, p < .01 | |||||

| (Range: 3, Mdn=1) | 1.07 | .338 | 1.07 | .338 | 1.00 | .517 |

Note. The total n for income does not equal 100% because participants under 18 were not asked.

Figure 1. National Distribution of Participants in the Analytic Sample.

Note. Numbers within states correspond to the State Racism Index Score. Participants in Puerto Rico and Washington DC not included in the analytic sample.

Table 2.

Descriptives and Correlations Between Primary Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Structural racism | -- | −.46*** | −.05 | .11*** | −.04 | −.01 | .02 | .004 | −.04 |

| 2. Anti-LGBTQ policies | −.49*** | -- | .04 | −.07*** | .01 | .02 | .004 | −.02 | −.002 |

| 3. Depressive Symptoms | .07 | .02 | -- | .03 | .56*** | .63*** | .46*** | .32*** | .24*** |

| 4. Heavy Drinking | .03 | −.03 | .09 | -- | .02 | −.05 | −.02 | .05 | −.002 |

| 5. Perceived Burdensomeness | −.02 | .11*** | .55*** | .05 | -- | .64*** | .50*** | .35*** | .32*** |

| 6. Thwarted Belongingness | .04 | −.01 | .59*** | −.07 | .57*** | -- | .40*** | .22*** | .20*** |

| 7. Suicidal Ideation | −.05 | .08 | .50*** | .06 | .43*** | .33*** | -- | .24*** | .23*** |

| 8. Self-harm | .01 | .07 | .22*** | .14*** | .30*** | .19*** | .29*** | -- | .53*** |

| 9. Suicide Attempt | −.05 | .12* | .27*** | .03 | .29*** | .17*** | .34*** | .48*** | -- |

|

| |||||||||

| Range | 25.9–74.9 | 0–1 | 0–30 | 0–12 | 6–42 | 9–62 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 |

| Mean | 49.58 | .76 | 12.36 | 3.80 | 12.02 | 27.45 | .23 | .36 | .24 |

| SD | 10.41 | .43 | 6.47 | 2.63 | 8.03 | 12.26 | .42 | .48 | .43 |

| Alpha | -- | -- | .87 | .79 | .95 | .90 | -- | -- | -- |

Note:

p≤ .001

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .10

All correlations are with observed scores. The values on the bottom half of the diagonal line are correlations among study variables in the White subsample. Values on the top half of the diagonal line represent correlations among study variables in the Black subsample. The estimates between continuous variables are Pearson correlations, correlations between continuous and dichotomous variables are point biserial correlations, correlations between continuous and ordinal variables are point polyserial correlations, and correlations between ordinal and other ordinal or binary variables are polychoric correlations.

“--” indicates that an alpha is not available for a dichotomous variable.

Regarding latent variable specification, a two-factor, 15-item specification of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (Van Orden et al., 2012) CFA indicated adequate data fit for Black participants, χ2(88)=936.70, p≤0.001; CFI=0.96, TLI=0.95, RMSEA=0.14, SRMR=0.08, though RMSEA was moderately elevated, likely reflecting limitations with sample size (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Another CFA indicated adequate fit for White participants, χ2(88)=1544.42, p≤0.001; CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.11, SRMR=0.04. For Black participants, standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.88 to 0.97 for perceived burdensomeness and 0.62 to 0.89 for thwarted belongingness. For White participants, standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.88 to 0.95 for perceived burdensomeness and 0.64 to 0.89 for thwarted belongingness. Because CFAs indicated the equivalence of the factor structure for all variables across Black and White participants, we found evidence for configural invariance across race for these variables.

For depressive symptoms, although it is not possible to consult fit statistics with an under-identified two-indicator model, standardized factor loadings were 0.62–0.74 across models with Black and White participants. Similarly for suicidal ideation, although it was not possible to consult fit statistics with an under-identified two-indicator model, standardized factor loadings were 0.92–0.96 across models with Black and White participants.

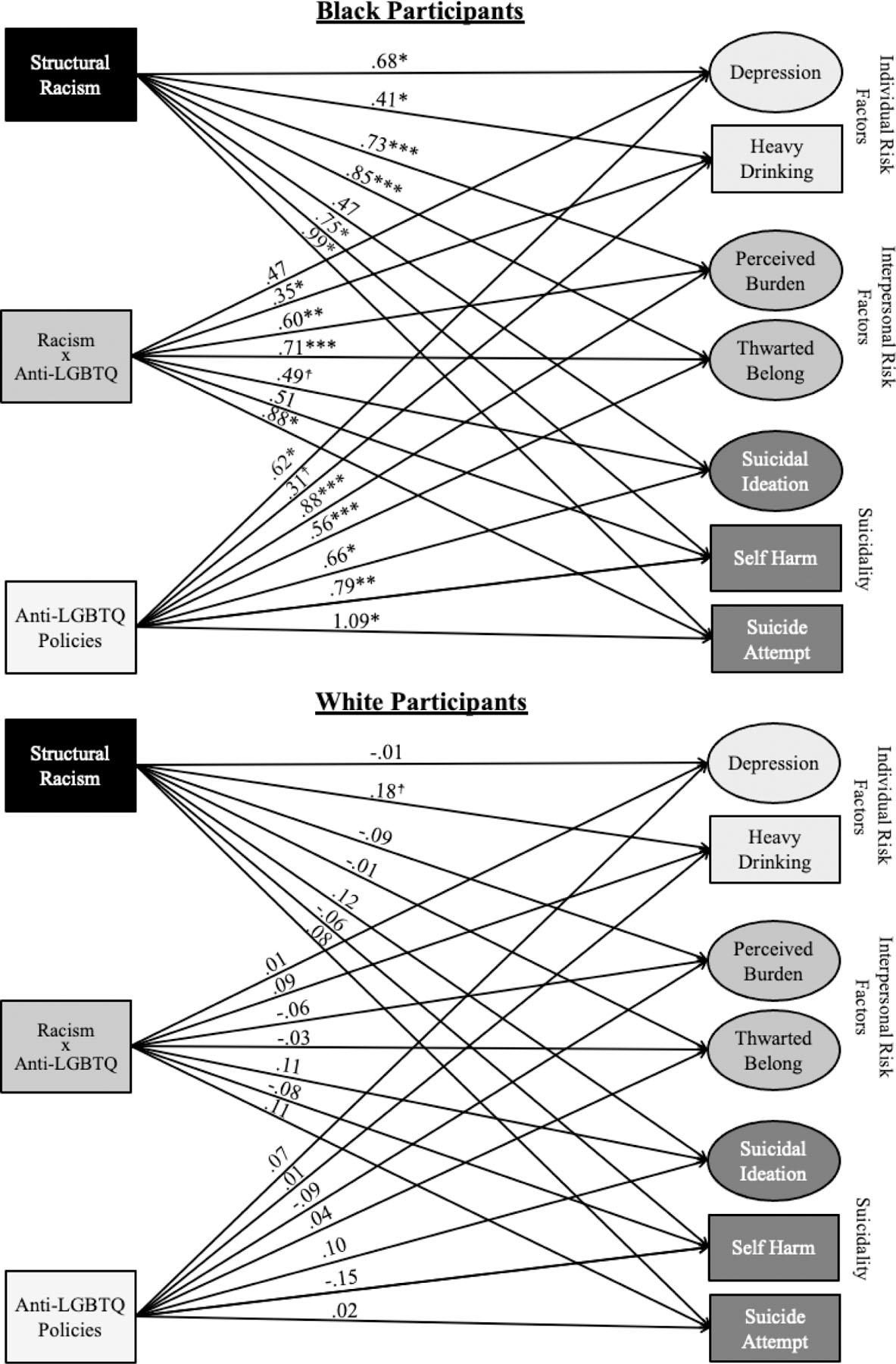

Figure 2 depicts the primary model for Black and White participants. Indices suggested good fit for Black, χ2(516)=765.56, p≤0.001; CFI=0.98, TLI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03, SRMR=0.07, and White participants, χ2(516)=1082.92, p≤0.001; CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, RMSEA=0.03, SRMR=0.04. Among Black participants, structural racism was significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms (β=0.68, S.E.=0.33, p=0.04), heavy drinking (β=0.41, S.E.=0.19, p=0.03), perceived burdensomeness (β=0.73, S.E.=0.22, p=0.001), thwarted belongingness (β=0.85, S.E.=0.11, p<0.001), self-harm (β=0.75, S.E.=0.37, p=0.04), and suicide attempt (β=0.99, S.E.=0.51, p=0.05). Anti-LGBTQ policies were significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms (β=0.62, S.E.=0.31, p=0.05), perceived burdensomeness (β=0.88, S.E.=0.22, p<0.001), thwarted belongingness (β=0.56, S.E.=0.16, p<0.001), suicidal ideation (β= 0.66, S.E.=0.29, p=0.02), self-harm (β=0.79, S.E.=0.30, p=0.009), and suicide attempt (β=1.09, S.E.=0.46, p=0.02). The interaction term was positively associated with heavy drinking (β=0.35, S.E.=0.17, p=0.04), perceived burdensomeness (β=0.60, S.E.=0.20, p=0.002), thwarted belongingness (β=0.71, S.E.=0.13, p<0.001), and suicide attempt (β=0.88, S.E.=0.45, p=0.05).

Figure 2. Structural Equation Models with Structural Racism and Anti-LGBTQ Policies Predicting Suicide Risk for Young Black and White SMM.

Note: *** p≤ .001, ** p ≤ .01, * p ≤ .05, † p ≤ .10

Standardized estimates (STDYX for Structural Racism and interaction term, STDY for Anti-LGBT Policies). This model is adjusted rural-urban classification, subjective SES, income, formal employment status, housing instability, age, sexual identity, relationship status, living situation (living alone/with others), whether participants have living parents/stepparents and are contact with them, insurance coverage, and military experience.

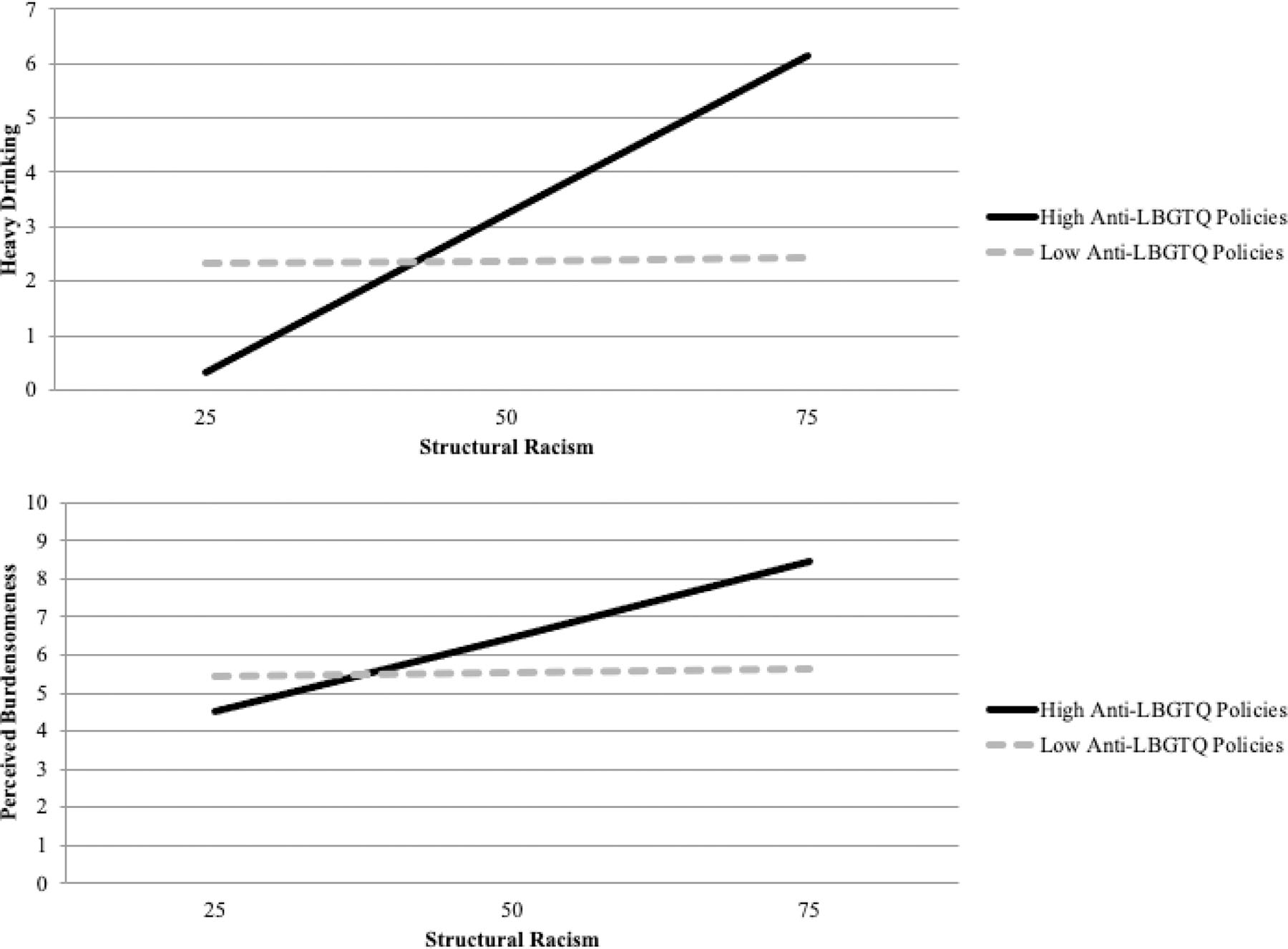

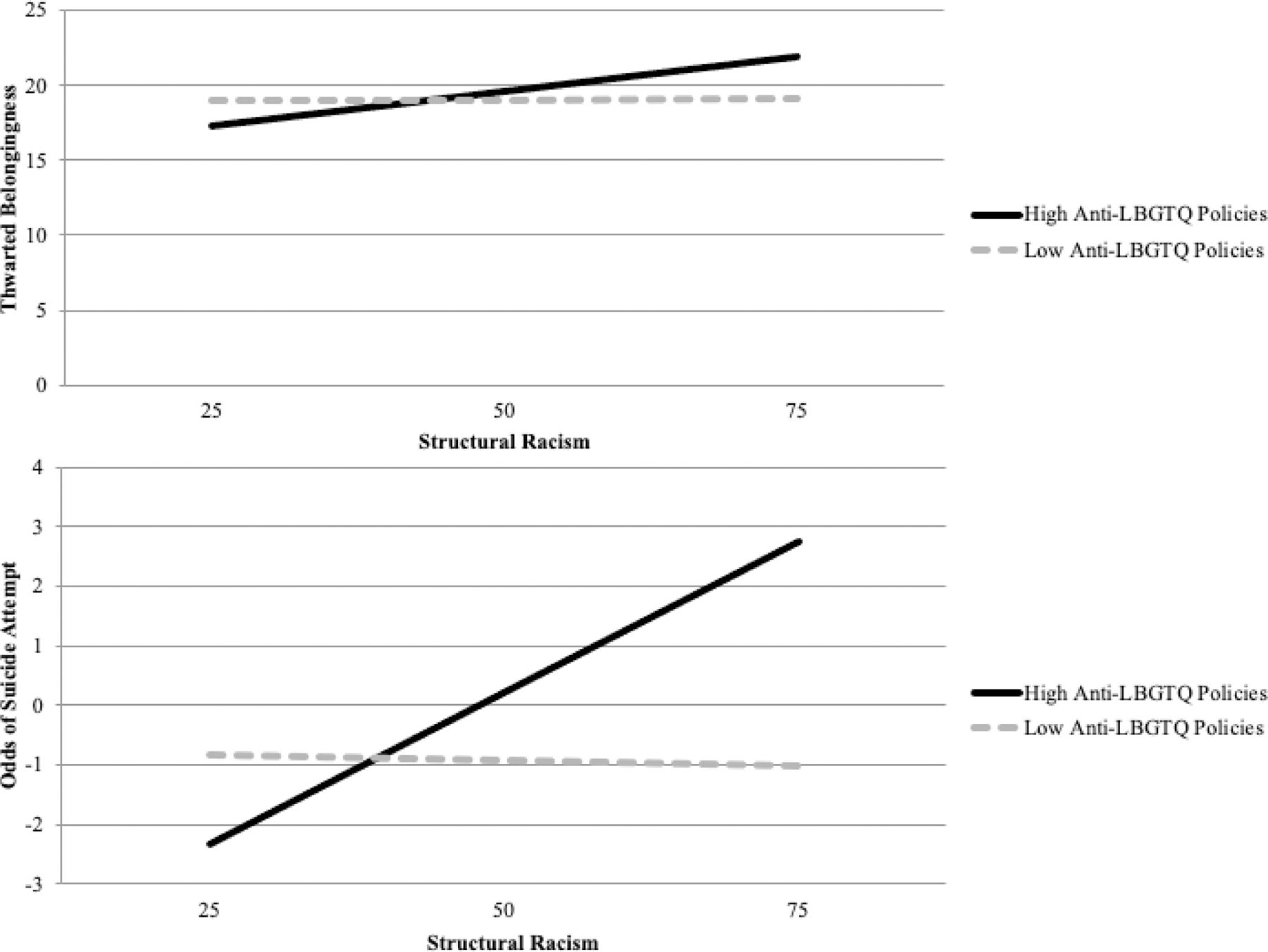

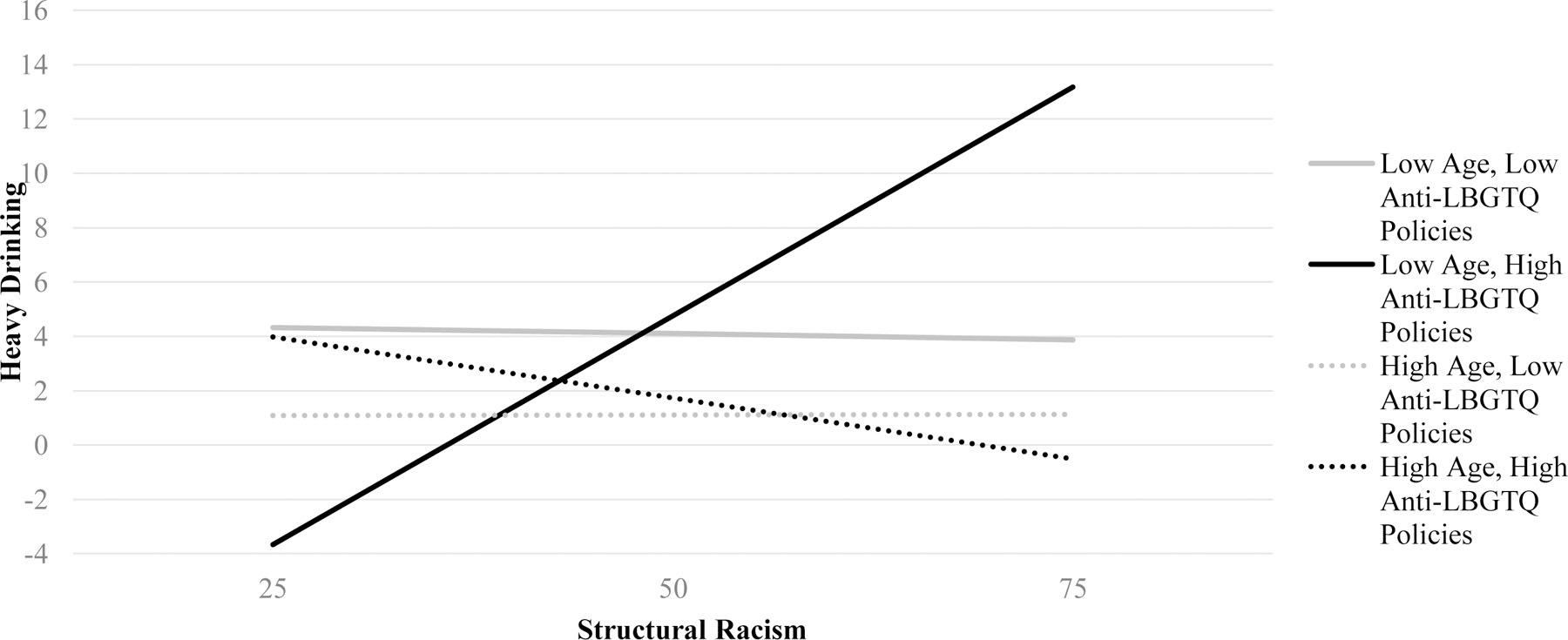

Figure 3 displays interaction effects, showing that the positive associations between structural racism and heavy drinking, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide attempt were stronger for Black SMM living in states with high levels of anti-LGBTQ policies. Simple slopes showed that for high anti-LGBTQ policies, structural racism was positively associated with heavy drinking (b=0.12, S.E.=0.06, p=0.04), perceived burdensomeness (b=0.08, S.E.=0.02, p=0.001), thwarted belongingness (b=0.09, S.E.=0.01, p<0.001), and suicide attempt (b=0.10, S.E.=0.05, p=0.059), though not for low anti-LGBTQ policies for heavy drinking (b=0.002, S.E.=0.01, p=0.88), perceived burdensomeness (b=0.004, S.E.=0.01, p=0.69), thwarted belongingness (b=0.002, S.E.=0.01, p=0.83), and suicide attempt (b=−0.004, S.E.=0.01, p=0.56). Neither of the oppression variables nor their interaction were significantly associated with suicide risk for White SMM. The multigroup chi-square difference test showed that the model with the hypothesized pathways constrained across White and Black participants led to a significant decrement in model fit from the freely estimated model, Δχ2 (21) = 76.86, p < 0.001. Lastly, exploratory age moderation models showed that the structural racism x age (β=−0.74, S.E.=0.28, p=0.008) and structural racism x anti-LGBTQ policies x age (β=−0.66, S.E.=0.26, p=0.01) interaction terms were significantly associated with heavy drinking. This indicates that younger Black SMM had stronger associations between structural racism and heavy drinking and that the positive association between heavy drinking and structural racism was strongest for younger Black SMM living in states with high anti-LGBTQ policies (Figure 4). Simple slopes showed that for younger Black SMM facing high anti-LGBTQ policies, structural racism was positively associated with heavy drinking (b=0.34, S.E.=0.12, p=0.004), but not for younger Black SMM facing low anti-LGBTQ policies (b=−0.01, S.E.=0.03, p=0.79), older Black SMM facing low anti-LGBTQ policies (b=−0.01, S.E.=0.03, p=0.79), or older Black SMM facing high anti-LGBTQ policies (b=−0.09, S.E.=0.07, p=0.20). No other interaction terms were associated with our dependent variables.

Figure 3. Interactions between Structural Racism and Anti-LGBTQ Policies on Suicide Risk Factors among Young Black SMM.

Note: Perceived burdensomeness is recoded to range from 0–36 for this figure

Note: Thwarted belonginess is recoded to range from 0–53 for this figure

Figure 4. Interaction between Structural Racism, Anti-LGBTQ Policies, and Age on Heavy Drinking on Among Young Black SMM.

Note: Low Age = 1 SD below centered mean, High Age = 1 SD above centered mean

Discussion

The present study indicates structural oppression is a matter of life and death for young Black SMM. Extending prior research demonstrating associations between structural oppression and psychological health (Hatzenbuehler, 2016), this study provides evidence that racist and anti-LGBTQ policies are independently and synergistically associated with suicide risk factors among young Black SMM. This included positive independent associations with depressive symptoms, heavy drinking (structural racism only), perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, suicidal ideation (anti-LGBTQ policies only), self harm, and suicide attempt and synergistic associations with heavy drinking, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicide attempt. Previous research investigating the health implications of state-level laws and policies has focused primarily on single axes of oppression (e.g., racist or anti-LGBTQ oppressionn), or have not presented meaningfully disaggregated findings to reveal patterns of suicide inequities for young Black SMM. In contrast, the present study, informed by the intersectionality framework, indicates structural racism and anti-LGBTQ oppression conjointly contribute to suicidality among young Black SMM.

Results highlight the compounded nature of structural oppression and suggest that high rates of suicide risk among young Black SMM communities (Baiden et al., 2020) may be associated with the intersectional effects of structural racist and anti-LGBTQ policies. These findings dovetail with evidence showing independent associations of both racial and LGBTQ discrimination with suicidal ideation among Black sexual minority adolescents (Thoma & Huebner, 2013). Although past studies suggest that SMM of color may be less likely to report suicidal ideation, other evidence suggests significant numbers of young Black and Latinx SMM report suicidality (O’Donnell et al., 2011), and Black bisexual adolescents may be at particularly high risk for suicide attempt (Baiden et al., 2020; Kipke et al., 2020). Results from the current study provide another perspective on structural-level factors underlying these inequities, showing that objective measures of structurally racist and anti-LGBTQ policy contexts were associated with self-harm and suicide attempt among young Black SMM. Additionally, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to show both independent and conjoint associations between structural oppression and interpersonal risk factors for suicide (i.e., thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness), which may be critical predictors of suicide among adolescents (Horton et al., 2016).

In contrast to the young Black SMM in our sample, neither form of oppression nor their interaction were significantly associated with suicide risk among young White SMM. This differs from multiple studies that have found a link between anti-LGBTQ structural oppression and suicidality among mostly White sexual minority samples (Hatchel, Polanin, & Espelage, 2019; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013; Raifman, Moscoe, Austin, & McConnell, 2017; Barnett et al., 2019). Our analyses may not have found an effect for White SMM because whiteness may be protective against several of the policies assessed in our anti-LGBTQ policies composite measure. In fact, many of the policies may be more aptly described as anti-Black-LGBTQ policies because they disproportionately target Black SMM through mechanisms against which White SMM are shielded. For example, Black SMM are more susceptible to both acquiring and transmitting HIV, not merely through their sexual behaviors, but also through social-structural factors, particularly structured opportunities (e.g., inequitable access to pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention; Boone & Bowleg, 2020) that confer increased risks compared to White SMM. Because of this inequity in HIV incidence and prevalence among Black SMM, the HIV criminalization laws that we assessed as a part of our anti-LGBTQ policies measure are more likely to negatively affect Black SMM than White SMM. Additionally, Black SMM are more likely to encounter people who will discriminate against them, harass, or enact violence against them due to the visibility of their racial identity and their sexual minority status—which are inextricably linked. These differences in associations reveal the critical importance of investigating suicidality among sexual minority communities through the lens of intersectionality and recognizing that forms of structural oppression may confer higher risk for suicide based upon multiple axes of social position. Considered together, these results suggest that the repeal of laws that are inequitably enforced on young Black SMM (e.g., HIV criminalization laws, stop and frisk policing; Movement Advancement Project, Center for American Progress, & Youth First, 2017), and the implementation of policies meant to reduce inequities in housing, education, and incarceration for Black SMM, should be advanced as imperative suicide prevention strategies (Layland et al., 2020). In fact, given our findings, it appears that the suicide protective effects of anti-discrimination and anti-hate crime policies, such as those provided by the Equality Act (H.R. 5; U.S. House of Representatives, 2021–2022), may be even stronger for Black SMM compared with White SMM.

Results of the age moderation analysis suggest that the negative effects of structural racism on heavy drinking may be most pronounced for younger adolescent and emerging adult Black SMM, especially those living in states with high levels of anti-LGBTQ policies. Consistent with hypotheses about childhood and adolescence being critical periods at which oppression has a pronounced impact on mental health (Gee et al., 2019; Trent et al., 2019), these findings indicate that adolescence and early emerging adulthood may be a critical period at which structural oppression has an outsized impact on heavy drinking for young Black SMM. Additionally, this result is consistent with recent evidence that suggest suicide risk factors associated with oppression may intensify at the beginning of emerging adulthood among Black SMM (Layland et al., 2020). As such, policy-level prevention intervention during early adolscence and childhood may be most effective in reducing the impacts of structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies on young Black SMM. However, our results are worth additional consideration and examination, especially given we did not find evidence for age moderation for suicide ideation, self-harm, or suicide attempt and research has found that increased risk for suicide among young Black SMM is not accounted for by inequities in substance use (O’Donnell et al., 2011). Thus, additional research among young Black SMM is needed to highlight associations between structural oppression and suicide risk factors across early adolescence into emerging adulthood.

In combination with evidence that sexual minority children (Blashill, Fox, Feinstein, Albright, & Calzo, 2021), and particularly Black sexual minority children (O’Donnell et al., 2011), are at higher risk for self-harm, suicide ideation and attempts than their heterosexual and White counterparts, the current study suggests that young Black SMM may especially benefit from structural prevention interventions, in addition to those individual-, family-, and community-level interventions implemented during early adolescence and childhood. Prior research highlights factors that may potentially protect young SMM from suicide risk, including exposure to positive LGBTQ messages, family acceptance, peer support, and LGBTQ-affirmative school environments (Luong, Rew, & Banner, 2018). However, interventions must transcend merely ameliorative individual-level approaches aimed at helping young Black SMM to more effectively navigate or cope with oppressive systems. Indeed, our results suggest that interventions must also include transformative efforts that cultivate racially and LGBTQ-affirming policy contexts, including the repeal of oppressive laws and policies that confer risk for suicide among young Black SMM (e.g., HIV/AIDS criminalization) and the execution of laws and policies that protect them. These can include the prohibition of conversion therapy, protections against victimization in schools, and the guarantee of quality healthcare across gender and sexual identity. These are particularly important during a year in which dozens of state legislatures are pursuing anti-LGBTQ policies (Ronan, 2021) that, in line with the present results, often disproportionately harm LGBTQ youth of color (Movement Advancement Project & Center for American Progress, 2016, 2017). Finally, while research shows that comprehensive LGBTQ policy environments are protective against proximal and distal risk for suicide among sexual minority communities (Drabble et al., 2021; Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013), achieving health equity for all sexual minority communities requires advancing comprehensive anti-racist policies that reduce racial inequities in housing, wealth, education, and incarceration (Bassett & Galea, 2020).

This is one of few studies that has investigated relationships between structural oppression and suicidality among young Black SMM, and to our knowledge the first to examine how structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies intersect to predict suicide risk among a national sample of young Black SMM. The present study also includes both a within and between group comparison, finding evidence for policy effects among young Black SMM and not finding evidence for policy effects among White SMM. Several limitations are worth noting, however. First, because we drew our analytic sample from a larger study examining HIV risk and seroconversion, the participants are likely higher sexual risk than the general SMM population. That is, participants were connected to sexual networking apps and were engaged in some level of sexual risk behavior (e.g., condomless sex), which may limit generalizability to younger Black SMM who are not sexually active, or those who do not utilize such apps. Second, our measure of anti-LGBTQ policies did not disentangle policies targeting different groups within LGBTQ communities. Accordingly, not all policies (e.g., transgender and gender expansive-exclusion laws) may have specifically targeted participants in this study equally across all intersectional social positions. Similarly, in combining several policies into a single dichotomous measure, our anti-LGBTQ policies variables was relatively crude. As such, future research should consider metrics that include both policy and climate indicators, like the structural racism metric did in this study. In this way, the structural racism and anti-LGBTQ policies indices were related, but not directly comparable because the latter is based on specific policy positions (e.g., allowing conversion therapy), while the former is based on proximal climate indicators of policies (e.g., Black-White education inequities). In addition, while policies and structural oppression are often highly consistent across time (Hardeman et al., 2018), it is worth noting that the period of time covered by the 2018 HRC index used to measure anti-LGBTQ policies differed from the period of time (2010–2015) for the State Racism Index used to measure structural racism with census and government data. Future research on suicidality among sexual minority adolescents and emerging adults can build upon this study by examining multi-year longitudinal models that examine developmental trajectoris of outcomes and adjustments to structurally racist and anti-LGBTQ policies (Raifman et al., 2018; Raifman et al., 2017), particularly for suicidal ideation which we found was associated with anti-LGBTQ policies, but not structural racism. Occurences like the June 2020 U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding Title VII civil rights protections for LGBTQ people, prohibition of conversion therapy, reforms to racist policing practices, and various state-level and local efforts addressing structural racism (Agénor et al., 2021; American Public Health Association, 2021), are all propitious opportunities to further investigate how changes in structural-level factors affect health outcomes across different populations, as well as across time.

Overall, our findings support eliminating racist and anti-LGBTQ policies as essential public health interventions to reduce the rising tide of suicide among young Black SMM. Implemented through the lens of intersectionality — that is, with acknowledgement of potential differential patterns of suicide risk due to multiple, yet intervenable, interlocking systems of oppression — this study adds to a burgeoning line of research that supports advancement of health equity through structural and policy interventions.

Acknowledgment of financial and other support:

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all our participants within the UNITE study for their time and feedback. We would like to thank all the staff, students, and interns who made this study possible, including Trinae Adebayo, Kris Ali, Paula Bertone, Dr. Cynthia Cabral, Ingrid Camacho, Juan Castiblanco, Jorge Cienfuegos Szalay, Ricardo Despradel, Nicola Forbes, Ruben Jimenez, Jonathan Lopez Matos, Brian Salfas, and Ore Shalhav. We are grateful for the time and contributions of Dr. Mark Pandori and the Alameda County Public Health Laboratory. We would also like to thank collaborators, Drs. Carlos Rodriguez-Díaz and Brian Mustanski. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institutes of Health, particularly our Project Scientists, Drs. Gerald Sharp, Sonia Lee, Michal Stirratt, and Gregory Greenwood. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH118091, PI: English) and a grant jointly awarded by the National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute on Mental Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute on Child Health and Human Development, and National Institute on Drug Abuse (UG3-AI133674, PI: Rendina). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Data collection for this study was conducted at Hunter College of the City University of New York (CUNY) and affiliations reflect authors’ institutions at the time of the most recent manuscript submission, which were not directly involved in the human subjects portion of the research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts of interest to report.

Financial disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- Adler N, & Stewart J (2007). The MacArthur scale of subjective social status. Retrieved September 28, 2019 from https://macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php

- Agénor M (2020). Future directions for incorporating intersectionality into quantitative population health research. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 803–806. 10.2105/ajph.2020.305610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agénor M, Perkins C, Stamoulis C, Hall RD, Samnaliev M, Berland S, & Bryn Austin S (2021). Developing a database of structural racism–related state laws for health equity research and practice in the United States. Public Health Reports. 10.1177/0033354920984168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, & APA Working Group on Health Disparities in Boys and Men. (2018). Health disparities racial/ethnic and sexual minority boys and men. Retrieved September 28, 2019 from http://www.apa.org/pi/health-disparities/resources/race-sexuality-men.aspx

- American Public Health Association. (2021). Racism is a public health crisis - Map of declarations. https://apha.org/racism-declarations

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a Short Form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B, & Muthén BO (2006). Robust chi square difference testing with mean and variance adjusted test statistics. Matrix, 1(5), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M, & Caldwell CH (2017). Discrimination increases suicidal ideation in Black adolescents regardless of ethnicity and gender. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4). 10.3390/bs7040075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 688–696. 10.1037/a0038994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiden P, LaBrenz CA, Asiedua-Baiden G, & Muehlenkamp JJ (2020). Examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents: Findings from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 125, 13–20. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett AP, Molock SD, Nieves-Lugo K, &, Zea MC (2019) Anti-LGBT victimization, fear of violence at school, and suicide risk among adolescents. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(1), 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MT, & Galea S (2020). Reparations as a public health priority—A strategy for ending Black–White health disparities. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(22), 2101–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science and Medicine, 110, 10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran K, & Smeeth L (2014). What is the difference between missing completely at random and missing at random? International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(4), 1336–1339. 10.1093/ije/dyu080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Fox K, Feinstein BA, Albright CA, & Calzo JP (2021). Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts among sexual minority children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(2), 73–80. 10.1037/ccp0000624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone CA, & Bowleg L (2020). Structuring sexual pleasure: Equitable access to biomedical HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 110(2), 157–159. 10.2105/ajph.2019.305503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase “women and minorities”: Intersectionality, an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2013). “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 754–767. 10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2020). We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 917–917. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray MJC, Daneshvari NO, Radhakrishnan I, Cubbage J, Eagle M, Southall P, & Nestadt PS (2020). Racial differences in statewide suicide mortality trends in Maryland during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA, & Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project. (1998). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael S, Ture K, & Hamilton CV (1992). Black power: The politics of liberation in America. Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Wilson BD, Shelton J, & Gates GJ (2015). Serving our youth 2015: The needs and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth experiencing homelessness. (UCLA: The Williams Institute, Issue. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1pd9886n [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, C. R., Rogers ML, Podlogar MC, Chiurliza B, Ringer FB, Michaels MS, Patros CHG, & Joiner TE Jr. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2002). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment.

- Colvin S, Egan JE, & Coulter RW (2019) School climate & sexual and gender minority adolescent mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2019 Oct;48(10):1938–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Black Caucus. (2019). Ring the alarm: The crisis of Black youth suicide in America – A report to Congress. https://watsoncoleman.house.gov/uploadedfiles/full_taskforce_report.pdf

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 139. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8/ [Google Scholar]

- del Río-González AM, Holt SL, & Bowleg L (2021). Powering and structuring intersectionality: Beyond main and interactive associations. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(1), 33–37. 10.1007/s10802-020-00720-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R, & Stefancic J (2017). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GB, Golden SH, Gross AL, Colantuoni E, & Dean LT (2020). Measuring Structural Racism and Its Association With BMI. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(4), 530–537. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble LA, Mericle AA, Gómez W, Klinger JL, Trocki KF, & Karriker-Jaffe KJ (2021). Differential effects of state policy environments on substance use by sexual identity: Findings from the 2000–2015 National Alcohol Surveys. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health, 2(1), 53–71. 10.1891/LGBTQ-2020-0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Carter JA, Boone CA, Forbes N, Bowleg L, Malebranche DA, Talan A, & Rendina HJ (2021). Intersecting structural oppression and Black sexual minority men’s health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. No pagination specified. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Rendina HJ, & Parsons JT (2018). The effects of intersecting stigma: A longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 669–679. 10.1037/vio0000218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J (2013). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, Rice CE, Lanza ST, & Russell ST (2019). Is young adulthood a critical period for suicidal behavior among sexual minorities? Results from a US national sample. Prevention Science, 20(3), 353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Hing A, Mohammed S, Tabor DC, & Williams DR (2019). Racism and the life course: Taking time seriously. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S43–S47. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, Polanin JR, & Espelage DL (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: Meta-analyses and a systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 13, 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, Karbeah JM, & Kozhimannil KB (2018). Naming institutionalized racism in the public health literature: A systematic literature review. Public Health Reports, 133(3), 240–249. 10.1177/0033354918760574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2016). Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. The American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. 10.1037/amp0000068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun H-J, Corliss HL, & Bryn Austin S (2015). Structural stigma and sexual orientation disparities in adolescent drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 46, 14–18. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM (2013). Inclusive Anti-bullying Policies and Reduced Risk of Suicide Attempts in Lesbian and Gay Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), S21–S26. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, & Hasin DS (2009). State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2275–2281. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, & Pettit JW (2012). Suicidal ideation and sexual orientation in college students: The roles of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and perceived rejection due to sexual orientation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(5), 567–579. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton SE, Hughes JL, King JD, Kennard BD, Westers NJ, Mayes TL, & Stewart SM (2016). Preliminary examination of the interpersonal psychological theory of suicide in an adolescent clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(6), 1133–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J, & Moodie-Mills A (2012). The unfair criminalization of gay and transgender youth: An overview of the experiences of LGBT youth in the juvenile justice system. Center for American Progress, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Best F, & Edwards N (2018). Stigma and intersectionality: a systematic review of systematic reviews across HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 919. 10.1186/s12889-018-5861-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagose A (1996). Queer Theory: An Introduction. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE (2005). Why people die by suicide: Harvard University press. Cambridge, MA, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D (2001). Structural Equation Modeling. In Smelser NJ & Baltes PB (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 15215–15222). Pergamon. 10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/00776-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Akinyemi IC, Hawkins W, Belzer M, Bhandari S, & Bray B (2020). The Healthy Young Men’s Cohort: Health, stress, and risk profile of Black and Latino young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Journal of Urban Health, 97(5), 653–667. 10.1007/s11524-019-00398-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layland EK, Exten C, Mallory AB, Williams ND, & Fish JN (2020). Suicide attempt rates and associations with discrimination are greatest in early adulthood for sexual minority adults across diverse racial and ethnic groups. LGBT Health, 7(8), 439–447. 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner JB, Hehman E, Ayduk O, & Mendoza-Denton R (2016, 2016/October/01). Blacks’death rate due to circulatory diseases is positively related to Whites’ explicit racial bias: A nationwide investigation using Project Implicit. Psychological Science, 27(10), 1299–1311. 10.1177/0956797616658450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Sheftall AH, Xiao Y, & Joe S (2019). Trends of suicidal behaviors among high school students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics, 144(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM (2014). Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 42–50. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong CT, Rew L, & Banner M (2018). Suicidality in young men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(1), 37–45. 10.1080/01612840.2017.1390020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoulides GA, & Schumacker RE (1996). Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCandless S (2018). LGBT homeless youth and policing. Public Integrity, 20(6), 558–570. 10.1080/10999922.2017.1402738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesic A, Franklin L, Cansever A, Potter F, Sharma A, Knopov A, & Siegel M (2018). The relationship between structural racism and Black-White disparities in fatal police shootings at the state level. Journal of the National Medical Association, 110(2), 106–116. 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, & Bakeman R (2007). Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS, 21(15), 2083–2091. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282e9a64b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Honermann B, Jones A, Lankiewicz E, Sherwood J, Blumenthal S, & Sayas A (2020a). White counties stand apart: The primacy of residential segregation in COVID-19 and HIV diagnoses. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 34(10), 417–424. 10.1089/apc.2020.0155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, Baral S, Mercer L, Beyrer C, Honermann B, Lankiewicz E, Mena L, Crowley JS, Sherwood J, & Sullivan PS (2020b). Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Annals of Epidemiology, 47, 37–44. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SE, Wierenga KL, Prince DM, Gillani B, & Mintz LJ (2021, 2021/March/21). Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Perceived Social Support, Mental Health and Somatic Symptoms in Sexual and Gender Minority Populations. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(4), 577–591. 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movement Advancement Project & Center for American Progress. (2016). Unjust: How the broken criminal justice system fails LGBT people of color. Retrieved from https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/lgbt-criminal-justice-poc.pdf. Retrieved on September 27, 2020.

- Movement Advancement Project & Center for American Progress. (2017). Unjust: LGBTQ youth incarcerated in the juvenile justice system. Retrieved from https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/lgbt-criminal-justice-youth.pdf. Retrieved on September 27, 2020.

- Mueller AS, James W, Abrutyn S, & Levin ML (2015). Suicide ideation and bullying among U.S. adolescents: Examining the intersections of sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 980–985. 10.2105/ajph.2014.302391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell S, Meyer IH, & Schwartz S (2011). Increased risk of suicide attempts among Black and Latino lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1055–1059. 10.2105/ajph.2010.300032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara I, Assan MA, Pierre K, Gunn JF, Metzger I, Hamilton J, & Arugu E (2020). Suicide among Black Children: An integrated model of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and intersectionality theory for researchers and clinicians. Journal of Black Studies, 51(6), 611–631. 10.1177/0021934720935641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Berg RC, Fernández-Dávila P, Mirandola M, Marcus U, Weatherburn P, & Schmidt AJ (2017). Anti-LGBT and anti-immigrant structural stigma: An intersectional analysis of sexual minority men’s HIV risk when migrating to or within Europe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 76(4), 356–366. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate AR, & Anestis MD (2020). Comparison of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, capability for suicide, and suicidal Ideation among heterosexual and sexual minority individuals in Mississippi. Archives of Suicide Research, 24, S293–S309. 10.1080/13811118.2019.1598525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek R, & Kralovec K (2014, Nov). Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(8), 1559–1570. 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LE, & Beyrer C (2020). Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among Black communities in America: The lethal force of syndemics. Annals of Epidemiology, 47, 1–3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Bowleg L, & Dickson-Gomez J (2019). “The fear of being Black plus the fear of being gay”: The effects of intersectional stigma on PrEP use among young Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Social Science and Medicine, 232, 86–93. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana NS, Rosenthal J, & Krehely J (2010). On the streets: The federal response to gay and transgender homeless youth. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Galea S (2018). Association of state laws permitting denial of services to same-sex couples with mental distress in sexual minority adults: A difference-in-difference-in-differences analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(7), 671–677. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raifman J, Moscoe E, Austin SB, & McConnell M (2017). Difference-in-differences analysis of the association between state same-sex marriage policies and adolescent suicide attempts. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(4), 350–356. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, Talan AJ, Tavella NF, Matos JL, Jimenez RH, Jones SS, … & Westmoreland D (2021). Leveraging technology to blend large-scale epidemiologic surveillance with social and behavioral science methods: Successes, challenges, and lessons learned implementing the UNITE longitudinal cohort study of HIV risk factors among sexual minority men in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(4), 681–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronan W (2021). 8 bills across 7 states: Coordinated anti-transgender, anti-LGBTQ legislative push ramps up in state houses across the country. Retrieved from https://www.hrc.org/press-releases/8-bills-across-7-states-coordinated-anti-transgender-anti-lgbtq-legislative-push-ramps-up-in-state-houses-across-the-country.

- Rubinsky AD, Dawson DA, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, & Bradley KA (2013, 2013/August/01). AUDIT-C Scores as a scaled marker of mean daily drinking, alcohol use disorder severity, and probability of alcohol dependence in a U.S. general population sample of drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(8), 1380–1390. 10.1111/acer.12092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SM, Hartinger-Saunders R, Brezina T, Beck E, Wright ER, Forge N, & Bride BE (2016). Homeless youth, strain, and justice system involvement: An application of general strain theory. Children and Youth Services Review, 62, 90–96. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma BC, & Huebner DM (2013). Health consequences of racist and antigay discrimination for multiple minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(4), 404–413. 10.1037/a0031739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent M, Dooley DG, & Dougé J (2019). The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics, 144(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (2019). Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE Jr (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade RM, & Harper GW (2015). Young Black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men: A review and content analysis of health-focused research between 1988 and 2013. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(5), 1388–1405. 10.1177/1557988315606962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waguespack D, & Ryan B (2019. ). State index on youth homelessness. True Colors United and the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Walker R, Francis D, Brody G, Simons R, Cutrona C, & Gibbons F (2017). A longitudinal study of racial discrimination and risk for death ideation in African American youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 47(1), 86–102. 10.1111/sltb.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ME, Mendola P, Liu D, & Grantz KL (2015). Joint effects of structural racism and income inequality on small-for-gestational-age birth. American Journal of Public Health, 105(8), 1681–1688. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warbelow S, Oakley C, & Kutney C (2018). 2018 State Equality Index. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Sayer AG, Schumacher R, & Marcoulides G (1996). Advanced structural equation modeling techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Wingate L, Gray TW, & Pantalone DW (2014). Evaluating thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as predictors of suicidal ideation in sexual minority adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(3), 234–243. 10.1037/sgd0000046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, O’Brien N, Forrest JI, Salters KA, Patterson TL, Montaner JSG, Hogg RS, & Lima VD (2012). Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PloS one, 7(7), e40793–e40793. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]