Abstract

Introduction

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is a skillset that influences and impacts an individual's ability to create, foster, and maintain strong relationships. In healthcare settings optimal patient centered care exists when teamwork, critical thinking, selfless service, integrity, and emotional intelligence are effectively practiced. While various methods exist to teach EI in the preprofessional and professional settings, the assessment of the efficacy of these types of training remains elusive. We propose a novel use of EI assessments to determine the effectiveness of EI programs and suggest that the information obtained can help shape and improve future EI education.

Methods

Volunteer participants involved in the 2020–2021 Feagin Leadership Program (FLP) at Duke University were recruited for this study. FLP is a one year program that aims to train healthcare leadership skills, with a special emphasis on EI. It is comprised of various stages of healthcare learners with a desire to improve their healthcare leadership skills. All participants took both an EI self-assessment (SSEIT) and EI ability assessment (MSCEIT) both before and after a dedicated 5-hour EI educational session. Individuals must have completed both a pre- and post-test for at least one assessment to be included in the study. Apart from standard descriptive statistics, Wilcoxon sign rank tests were utilized to determine the effectiveness of the educational session by comparing pre- and post-tests within each assessment. A Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to compare the results of the SSEIT and MSCEIT.

Results

A total of 32 FLP scholars initially participated in which 18 completed all assessments. Average age was 29 years old and consisted of medical students (n = 16), residents (n = 7), fellows (n = 7), advanced practice provider (n = 1) and a researcher (n = 1). Group analysis of the SSEIT pre and post scores were 131 (±13, range 98-149) and 136(± 13, 106-105), respectively which were statistically significant. Pre and post MSCEIT scores were 102 (±20, range 32-141) and 103 (±12, range 80-121), which were not significant. The EI branches with the highest score on each test was Managing Own Emotions and Understanding Emotions for the SSEIT and MSCEIT respectively while Perceiving Emotions was the lowest for both assessments. Comparison of the SSEIT and MSCEIT demonstrated a moderate correlation that was statistically significant.

Discussion

In our study participants felt their EI improved following the EI educational session, however this did not appear translate into their actual ability. This could be a function of self-report bias or a limitation of the EI assessments. More studies in this space are needed to make this determination. Additionally, the strengths of this specific program were within the strategic use of emotions therefore in the future more attention should be placed on experiential use of emotions, specifically perceiving emotions. As EI education and training becomes more prevalent it is important to not only accurately assess an individual's EI ability but also the effectiveness of the education being presented. We propose that EI assessments can be utilized as a tool to measure the effectiveness of EI education and receive formative programmatic feedback.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, leadership, curriculum, education

Introduction

The term emotional intelligence (EI) was originally described in 1990 by psychologists Peter Salovey and John Mayer as 1) the ability to monitor one's own and other people's emotions, 2) to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and 3) to use emotional information to guide thinking. 1 At that time EI was limited to an academic setting until 5 years later when the publication of Daniel Goleman's book, Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ propelled the concept into the common vernacular. 2 Because of its emphasis on relationships, EI has been promoted as an integral component of leadership, including within healthcare leadership.3–7 EI studies within the healthcare setting demonstrate that people with high levels of EI were shown to promote greater physical and emotional care, have higher job satisfaction, greater interpersonal sensitivity, increased patient safety, and many other favorable attributes to patient care.8–11

Given the importance and advantages of EI, it is important that it is evaluated in a validated and accurate manner. There are several forms of EI assessments. Self-reported assessments ask participants to answer how likely they are to agree with a series of statements about emotional information on a 1–5 Likert scale. Examples of self-reported assessments include the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i™), the Schutte Self Report EI Test (SSEIT), and the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue).12–14 We also note there are 360-degree versions of the self-reported EI assessments such as the EQ 360™. 15 Another type of assessment is the Mayer Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) which is an ability level EI assessment. 16 This assessment is modeled after traditional intelligence tests, but with a focus on emotional instead of analytical information. It is important to emphasize that the MSCEIT is an ability assessment – as in how well the respondent understands and uses their emotions and cognitions.

Traditionally these assessments concentrate on the individual and are used to create a snapshot of their EI level, however more value may be extracted from these assessments than previously thought. Due its ambiguity and similarity to other behavior skills, EI can be a difficult concept to teach, train, and develop. Current EI training and education is highly variable and there is limited evidence to suggest their effectiveness or sustainability. Therefore, it is important to deploy a quality improvement tool to ensure that learners are absorbing and applying their EI education correctly. We propose a novel way to utilize EI assessments as a formative quality improvement tool for educators to help create and shape EI education.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the study were recruited from the 2020–2021 Feagin Leadership Program (https://www.feaginleadership.org) at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The program is a yearlong leadership program whose mission is to provide a transformational learning experience that develops effective ethical leaders who positively influence healthcare and is made up of medical students, residents, fellows, researchers, and advanced practice providers. The program includes five leadership sessions (approximately 5 hours each), individual executive coaching, monthly team meetings, the development of a leadership project, and presentation at the annual Feagin Leadership Forum. All participants were volunteers and could leave the study at any time. The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

EI Education

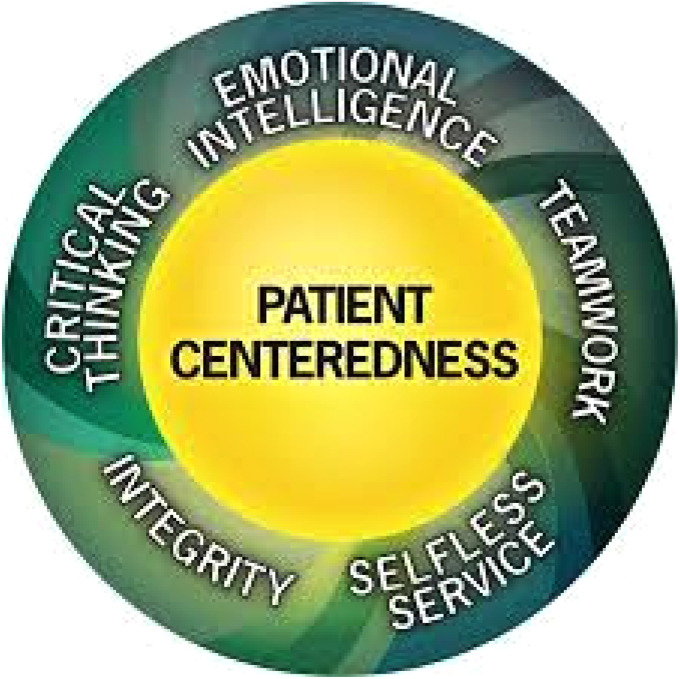

EI is a core value of the healthcare leadership model developed and followed by the Feagin Program (Figure 1). Of the five leadership sessions, the third session is a dedicated didactic lecture on EI. This session is approximately 5 hours long and consists of discussions and activities related to the development of EI skills and mindfulness. The objectives addressed in this session include: 1) understand what EI/Mindfulness is (and is not), 2) understand how and why EI is the ‘start point’ for ethical leadership in healthcare, 3) understand the ‘practice fields’ of EI, 4) be able to apply EI in any context/situation, and 4) understand what ethical leadership in healthcare looks and sounds like. Before the 2020–2021 cohort, the program did not perform formal EI assessments. We wanted to use the information from the assessments to identify strengths and weaknesses in the current EI education format to help shape future EI sessions.

Figure 1.

Duke healthcare leadership model developed by the feagin leadership program.

Assessments

Each participant received two EI assessments, the Schutte Self-Reported Emotional Intelligence Test (SSEIT) and the Mayer Salovey Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) at two different time points. 13 The SSEIT is a 33-question EI self-assessment that measures how much an individual agrees or disagrees with the EI statements on a 1–5 Likert scale. The MSCEIT is a proprietary EI assessment (administered by Multi-Health Systems Inc.) whose questions measure EI ability rather than self-reflection. Therefore, the MSCEIT may be considered the gold standard for EI measurement. 17 The first round of assessments (pre) were distributed and completed in February 2021, before the EI lecture in March. The second round (post) was distributed and collected at the completion of the leadership program in May-June 2021. Both assessments were available in an online format. Only individuals that had completed both pre and post tests within the same assessment were included in the study. Any incomplete tests were excluded. The SSEIT was scored according to the recommended guidelines based on the literature and the MSCEIT was scored using the expert panel method. 18 This MSCEIT scoring method has been shown to be equivalent to the general population scoring method and was recommended by one of the assessment authors (DC). 19

Analysis

The demographic data of the participants was reported, and descriptive statistics were used at the group level for the pre/post tests of both the SSEIT and the MSCEIT. Due to the non-parametric distribution of the data between the individual pre- and post-tests for each EI assessment, a Wilcoxon sign rank test was performed. The analysis of the Wilcoxon sign rank test was performed with a one-tail test, as the intervention was thought to only improve an individual's EI. Statistical significance was defined as a test statistic that is less than the Wilcoxon sign rank critical value with an alpha of 0.05. We also wanted to understand the correlation between the SSEIT and MSCEIT. Given the lower number of participants in the post-test, we limited our correlation analysis to the pre-test that had full participation. Due to the non-parametric distribution of the data, a Spearman's Ranked Correlation Coefficient was used to determine the relationship between the SSEIT and MSCEIT. Since the SSEIT and MSCEIT branches were similar but not identical, the Managing Own and Managing Others branches of the SSEIT were combined, and the Understanding branch of the MSCEIT was omitted. A two-tailed test with an alpha of 0.05 was applied.

Results

There were a total of 32 participants with an average age of 29 years old consisting of medical students (n = 16), residents (n = 7), fellows (n = 7), advanced practice provider (n = 1), and a researcher (n = 1). (Table 1) For the post-assessments, there were a total of 21 and 18 participants who completed the SSEIT and MSCEIT, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant pre and post education demographics for the SSEIT and MSCEIT.

| SSEIT and MSCEIT Pre | SSEIT Post | MSCEIT Post | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 32 | 21 | 18 |

| Male | 16 | 11 | 11 |

| Female | 16 | 10 | 10 |

| Average Age (range) | 29 (24-43) | 29 (24-43) | 29 (24-43) |

| Type of Participants | |||

| Medical Students | 16 | 11 | 7 |

| Residents | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Clinical Fellows | 7 | 5 | 3 |

| Advanced Practice Providers | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Researchers | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The SSEIT analysis showed a mean pre-total score of 131 (±13, range 98-149) and a post total score of 136(± 13, 106-105), which was statistically significant (test statistic: critical value, 49 < 67). (Table 2) There were also significant improvements within the Managing Own (test statistic: critical value, 51 < 67) and Managing Others (test statistic: critical value, 17 < 67) branches. The branch with the highest score after EI education was the Managing Own branch, while the lowest score was the Perceiving branch. Similar analysis in the MSCEIT demonstrated a mean pre-test total score of 102 (±20, range 32-141) and a post-test total score of 103 (±12, range 80-121). (Table 3) Statistical significance between the pre- and post-test was demonstrated within the Understanding (test statistic: critical value, 37 < 47) and Managing (test statistic: critical value, 42 < 47) branches. The highest MSCEIT branch after EI education was the Understanding branch, while the lowest was the Perceiving branch.

Table 2.

SSEIT pre and post EI education scores.

| SSEIT Group Pre | SSEIT Group Post | Highest Possible Score | Statistical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | 131 (±13,98-149) | 136 (±13, 106-105) | 165 | Yes |

| Perceiving Branch | 40 (±6, 23-49) | 40 (±6, 20-48) | 50 | No |

| Using Branch | 24 (±3, 18-30) | 25 (±3, 19-30) | 30 | No |

| Managing Own Branch | 36 (±4, 27-44) | 38 (±4, 27-45) | 45 | Yes |

| Managing Others Branch | 31 (±5,19-39) | 33 (±5, 24-40) | 40 | Yes |

Table 3.

MSCEIT pre and post EI education scores via expert consensus scoring. The MSCEIT has normalized distribution with a mean of 100.

| MSCEIT Group Pre | MSCEIT Group Post | Statistical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | 102 (±20, 32-141) | 103 (±12, 80-121) | No | |

| Perceiving Branch | 98 (±20, 31-146) | 92 (±13, 65-120) | No | |

| Using Branch | 98 (±18, 36-123) | 100 (±14, 69-126) | No | |

| Understanding Branch | 107 (±16, 51-128) | 114 (±9, 94-135) | Yes | |

| Managing Branch | 102 (±18, 36-132) | 109 (±14, 63-125) | Yes | |

There was a moderate correlation in the total score between the SSEIT and MSCEIT assessments that was statistically significant (R = 0.5, p-value < 0.001, Table 4). When comparing branches, there was a statistically significant moderate correlation in the Perceiving (R = 0.6, p-value < 0.001 and Managing (R = 0.4, p-value < 0.03) branches.

Table 4.

Spearman's ranke correlation coefficient between SSEIT and MSCEIT.

| Correlation (R value) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Score | 0.5 (moderate) | 0.001 |

| Perceiving Branch | 0.6 (moderate) | 0.001 |

| Using Branch | 0.2 (weak) | 0.35 |

| Managing | 0.4 (moderate) | 0.03 |

Discussion

With the increasing prevalence of EI education and training, it is important to not only accurately assess an individual's EI ability but also the effectiveness of the education presented. Our study used EI assessments, as a formative quality improvement tool, to receive educational feedback. Through these assessments, we were able to strategically breakdown the general concept of EI into specific branches of Perceiving, Using, Understanding, and Managing emotions. We suggest that understanding the strengths and weaknesses of these branches can help steer EI education.

In our study, we found that most participants were stronger in the strategic branches of Understanding and Managing emotions and weaker in the experiential branches of Perceiving and Using emotions. These results were initially surprising given that the Perceiving and Managing emotions are more well-known than the others. Daniel Goleman's book breaks down EI into different but similar branches: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. 2 Similarly the EQ-i™ reports on self-regard, emotional self-awareness, self-actualization, impulse control, and stress tolerance. 12 These concepts are related to the MSCEIT branches of Perceiving and Managing emotions, which we predicted to have the highest scores due to their ubiquity. However, this was only true for the Managing branch, and surprisingly the Perceiving branch demonstrated the lowest scores. Based on our study, instead of generally teaching about EI, the leadership program should focus on the experiential branches of Perceiving and Using emotions to more efficiently improve the overall EI of the group.

Currently, EI education is extremely variable in methodology, scope, and type of learners’ groups.20–25 Examples range from inexpensive, flexible, asynchronous online modules to the more involved and expensive executive coaching. Additionally, there are differences in the content of EI lectures as some focus adjacent concepts of mindfulness, burnout, or resilience. Applying EI assessments as a guide to create learning objectives and shape EI education can help differentiate EI from other abilities and promote a more standardized concept.

In education, feedback either directly from learners or through an assessment is an important way to improve and modify future educational content. We used of the SSEIT and MSCEIT assessments to receive formative feedback on our own EI education, which consisted of emphasizing EI as a key component of leadership and dedicating a day-long educational session. Analysis of the EI assessments both before and after the EI educational session demonstrated significantly higher total scores for the SSEIT, but not the MSCEIT. This improvement in self-assessed EI following the FLP was also described by Bonazza et al in which graduates of the FLP program over an 8 year period stated improvement in the domains of EI, communication, and team building. 26 The discrepancy between the self-reported SSEIT and ability-based MSCEIT can mean a few things. The first is that our specific education does improve EI and that the MSCEIT does not accurately capture or is not sensitive to this difference. The other may reflect a self-report bias in that participants believed their EI improved, which was not objectively true. The application of these EI assessments in this pre- and post-test method is relatively novel, specifically in regard to the administration of the MSCEIT. Due the length and cost of the MSCEIT a majority of EI studies opt for the self-assessment studies such as the TEIQue or SSEIT which are easy to administer, complete, and score. However, these advantages come with the opportunity cost of assessment validity. Groves et al performed a pre/post-test within a control and treatment group of business students, where the treatment group underwent an 11-week EI training program and were found to have significantly higher overall EI gains. 27 However, instead of distributing the MSCEIT, the authors created their own assessment tool based on the MSCEIT to assess EI. Although the use of these types of assessments to measure the efficacy of EI training is logical, more studies are needed to prove if these assessments can be accurately employed in this manner.

The correlation between the SSEIT and the MSCEIT was performed to characterize the relationship between both assessments. Compared to the SSEIT, the MSCEIT is a more time-consuming and costly assessment which may serve as a deterrent to its use. Therefore, we wanted to know if the SSEIT may be used in place of the MSCEIT. We found a moderate significant correlation in the total score between the SSEIT and MSCEIT. Although both tests are based on the philosophy of EI as an ability, instead of personality traits, their branches were not identical. The SSEIT has a Managing Own and Managing Other's emotions, while the MSCEIT combines these two into one Managing branch. Additionally, there was no comparable branch on the SSEIT to the Understanding branch on the MSCEIT and was subsequently omitted. Our study shows that when looking at the total score, the SSEIT may serve as a substitute for the MSCEIT to measure EI if needed, however should be interpreted with some caution.

Although we present a novel way to measure and shape EI education, our study has many limitations. The first is the small sample size, which underpowers the study; however, we were still able to find statistical significance through comparison of paired pre/post assessments. Common to all similar volunteer studies is the dropout rate. This was especially true for the post-MSCEIT assessment. We suspect that the higher dropout rate was due to the longer duration of test in relation to the SSEIT and the timing of the post-tests given the proximity to the end of the academic term. Another limitation is the assessments themselves. They are generally used as a snapshot of an individual's EI level, as opposed to our study where they were used to measure EI growth. It is possible that this approach is not applicable to the validity of the assessment and more studies are needed to characterize this method. Lastly, we had an abbreviated timeline of approximately 4 months between our pre- and post-tests. Ideally, the administration of the pre-tests would have been at the beginning of the academic school year, as some individuals may have developed EI through their own experiences in the leadership program. If this were true, then our reported results would be more conservative as the pre/post test difference would have been greater. To address this, we are in the process of repeating this study within the same cohort and will administer the pre-test at the beginning of the leadership program.

Fortunately, this study is the beginning, and there are many future directions that we plan to explore. As mentioned above, we plan to repeat the same study with a longer time interval between the pre- and post-tests. Additionally in our current study, EI education was performed as a group didactic lecture along with a few short personal reflection activities. While thought provoking, these interventions may not lead to behavior change. In his review article on the behavioral level of EI, Richard Boyatzis states that “since more training, education, and coaching predominately attempt to help people change the way they act, the behavioral level of EI and measuring it can be useful.” 28 Similarly we agree that EI ultimately is best demonstrated as a behavior and plan to incorporate simulation education in the future to observe behavior change.

Conclusion

EI education and training has gained recent popularity; however, there is considerable variability in educational delivery and effectiveness. The purpose of our study was to improve EI education and share how EI assessments, such as the SSEIT and MSCEIT, can be used in a novel way to receive valuable educational and learner feedback that can transform future EI trainings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support of the Feagin Leadership Program (https://www.feaginleadership.org) and VHA SimLearn (https://www.simlearn.va.gov). Additionally, we would like thank Nitin Patel, MPH for his statistical guidance.

Biography

Jason Chandrapal is the current Interprofessional Advanced Clinical Simulation Fellow at the VA Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. Originally from Houston, Texas he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Neurobiology from the University of Texas followed by a Masters of Science at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. He then obtained his MD degree from Texas Tech University Health Science Center School of Medicine. Following medical school he did a one year research fellowship at the University of Utah in the Division of Urology before starting urology residency at Duke University. Following his time at the VA, he plans to start a radiology residency program at University of Texas Southwestern this year.

Chan Park, MD is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at Duke University, Director of Simulation Education and Co-Director of the Durham, North Carolina Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System's Interprofessional Advanced Fellowship in Clinical Simulation, Senior Faculty Advisor for Duke Feagin Leadership Program and Faculty of Duke University School of Medicine Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Curriculum.

Mary Holtschneider is Co-Director of the Durham, North Carolina Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System's Interprofessional Advanced Fellowship in Clinical Simulation, and Nursing Program Manager for Duke University Area Health Education Center (AHEC).

Joe Doty, a Fellow Human, is the Executive Director of the Dr. John Feagin Leadership Program and Associate Director of the Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) curriculum at the Duke University School of Medicine.

Dean Taylor is a Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, Director of the Duke Sports Medicine Fellowship, Director of the Duke University School of Medicine Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) Curriculum, and Chairman of the Feagin Leadership Program

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1.Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers. 1990;9(3):185-211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Random House Publishing Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres-Landa S, Moreno K, Brasel KJ, Rogers DA. Identification of leadership behaviors that impact general surgery junior Residents’ well-being: a needs assessment in a single academic center. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(1):86-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert S. Role of emotional intelligence in effective nurse leadership. Nurs Stand. 2021;36(12):45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huikko-Tarvainen S. Elements of perceived good physician leadership and their relation to leadership theory. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). 2021. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoller JK. Help wanted: developing clinician leaders. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(3):233-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merriam SB, Rothenberger SD, Corbelli JA. Establishing competencies for leadership development for postgraduate internal medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(5):682-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nightingale S, Spiby H, Sheen K, Slade P. The impact of emotional intelligence in health care professionals on caring behaviour towards patients in clinical and long-term care settings: findings from an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;80:106-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollis RH, Theiss LM, Gullick AA, et al. Emotional intelligence in surgery is associated with resident job satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2017;209:178-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libbrecht N, Lievens F, Carette B, Cote S. Emotional intelligence predicts success in medical school. Emotion. 2014;14(1):64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Codier E, Codier DD. Could emotional intelligence make patients safer? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(7):58-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bar-On R. Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory: Technical Manual. 1997, Available from: https://storefront.mhs.com/collections/eq-i-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, et al. Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Dif. 1998;25(2):167-177. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper A, Petrides KV. A psychometric analysis of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue-SF) using item response theory. J Pers Assess. 2010;92(5):449-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bar-On R. EQ360. 2011; Available from: https://storefront.mhs.com/collections/eq-360.

- 16.Brackett MA, Salovey P. Measuring emotional intelligence with the Mayer-Salovery-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Psicothema. 2006;18(Suppl):34-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brackett MA, Mayer JD. Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(9):1147-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malouff J, Bhullar N. The Assessing Emotions Scale. 2009. p. 119–134.

- 19.Sanchez-Garcia M, Extremera N, Fernandez-Berrocal P. The factor structure and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso emotional intelligence test. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1404-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mounce M, Culhane N. Utilization of an emotional intelligence workshop to enhance student pharmacists’ self-awareness. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13(11):1478-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckley K, Bowman B, Raney E, et al. Enhancing the emotional intelligence of student leaders within an accelerated pharmacy program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(11):8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nes E, et al. Building communication and conflict management awareness in surgical education. J Surg Educ. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson KL, Cobb MIH, Gunasingha RM, et al. Improving medical leadership education through the Feagin leadership program. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:290-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghelbash Z, Zarshenas L, Dehghan Manshadi Z. A trial of an emotional intelligence intervention in an Iranian residential institution for adolescents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26(4):993-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malinauskas R, Malinauskiene V. Training the social-emotional skills of youth school students in physical education classes. Front Psychol. 2021;12:741195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonazza NA, Cabell GH, Cheah JW, Taylor DC, et al. Effect of a novel healthcare leadership program on leadership and emotional intelligence. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34(5):272-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groves KS, Pat McEnrue M, Shen W. Developing and measuring the emotional intelligence of leaders. J Manage Dev. 2008;27(2):225-250. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyatzis RE. The behavioral level of emotional intelligence and its measurement. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1438-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]