Lay Summary

Herein, we evaluated the humoral immunogenicity of a third coronavirus disease 2019 messenger RNA vaccine dose in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. All patients displayed a humoral immune response, and median antibody concentrations were higher after the third dose than after completion of the 2-dose series.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, COVID-19 vaccine

Introduction

Three safe and effective coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines were authorized by the Food and Drug Administration in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) nor immunosuppressed patients were included in the original phase III clinical trials, though they were included in trials of authorized COVID-19 therapies.1,2 Studies have since demonstrated a humoral immune response rate of 95% to 99% following vaccination with a 2-dose messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccine series in patients with IBD.3–5 Results show that those on certain immune-modifying therapies, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) combination therapy or systemic corticosteroid therapy, may exhibit a relatively diminished humoral immune response and a relative decrease in serum antibody concentrations over time.3–5

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends a third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine as part of the primary series for those who are moderately-to-severely immunocompromised, or as a booster dose for those who are otherwise immunocompetent.6 The aim of this study was to evaluate the humoral immunogenicity of a third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose in patients with IBD. We hypothesized that patients would mount a significant humoral immune response, and that those on certain immune-modifying therapies, such as systemic corticosteroids or anti-TNF combination therapy, would have relatively lower serum antibody concentrations.

Methods

This was a multicenter, prospective, nonrandomized study comprised of patients with IBD and healthy controls (HC) in the “Humoral and Cellular Initial and Sustained Immunogenicity in Patients with IBD” (HERCULES) cohort.4 Participants with IBD were enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Madison, Wisconsin) and Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, Florida), while HC were employees of Labcorp. Patient eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of IBD, age 18 to 85 years, stable doses of maintenance therapy (any IBD-directed therapy used for ≥2 months following the induction phase of therapy) or the absence of IBD-directed therapy (for ≥6 months), and completion of a 2-dose mRNA vaccine series. The HC eligibility criteria included the absence of immunosuppressive therapy and documented completion of a 2-dose mRNA vaccine series. A third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose was available to patients with IBD but not HC. No participants had a clinical history of COVID-19 infection, and those with laboratory evidence of a prior infection, as demonstrated by the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) nucleocapsid antibodies, were excluded.

Participants recruited at the Mayo Clinic received their COVID-19 vaccines at a Mayo Clinic facility, and receipt of vaccine was confirmed by an interview and a review of the electronic medical record. At the University of Wisconsin, vaccination status was confirmed by review of the Wisconsin Immunization Registry (WIR). The WIR is a state-wide database maintained by the Department of Health and Family Services of the State of Wisconsin, in which vaccine data for each Wisconsin resident are stored. The WIR captures 97% of vaccines administered in the state, and 98.5% of Wisconsin residents have an active WIR record. The WIR does not capture vaccines administered outside the state, and all Wisconsin vaccine providers are required to enter records of COVID-19 vaccine administration into the registry.7 The WIR has been previously used to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine uptake in patients with IBD.8

The primary outcome was total serum SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike immunoglobin (Ig) G antibody concentrations following a third dose compared to antibody concentrations following the 2-dose series in the IBD cohort. Secondary outcomes included antibody concentrations following a third dose in patients with IBD compared to antibody concentrations 180 days after the 2-dose series in HC. The effects of the vaccine manufacturer and immunosuppressive therapy on antibody concentrations following a third dose in patients with IBD were also evaluated.

Specific antibodies measured in sera were nucleocapsid and spike protein S1 receptor-binding domain–specific IgG antibodies (mcg/ml), as previously described.4 In patients with IBD, we measured antibody concentrations 28 to 35 days (t1) after completion of the 2-dose series and 28 to 65 days (t2) after the third dose. Only patients with IBD who received a third dose had antibody concentrations measured at t2, and not every subject who had antibody concentrations measured at t2 had them measured at t1 due to the timing of enrollment. In HC, we measured antibody concentrations 30 days (t1) and 180 days (t2) after completion of the 2-dose series. An enzyme-linked immunoassay was performed at Labcorp, as previously described.4

The IBD treatment groups were defined as subjects on stable doses of maintenance therapy, as previously described.4 Nonimmunosuppressive therapy was defined as the absence of IBD-directed therapy or receipt of treatment with mesalamine monotherapy or vedolizumab monotherapy. Immunosuppressive therapy was defined as thiopurine monotherapy (ie, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine), anti-TNF monotherapy, anti-TNF combination therapy (ie, plus antimetabolite), ustekinumab monotherapy or combination therapy, tofacitinib, or systemic corticosteroid therapy (ie, any of the aforementioned groups plus systemic corticosteroids). Antibody concentrations between groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. The study received Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Wisconsin, Mayo Clinic, and Labcorp.

Results

There were 139 patients with IBD who completed the 2-dose series and had antibody concentrations measured at t1, and 85 patients received a third dose and had antibody concentrations measured at t2 (Table 1). The median time between receipt of the third dose and completion of the 2-dose series was 149 days (IQR, 132–167 days). There were 46 HC who completed the 2-dose series and had antibody concentrations measured at both time points. In the IBD cohort, 48.2% and 51.8% received the 2-dose Moderna and Pfizer series, respectively, compared to 93.5% and 6.5% in HC, respectively (P < .001). Two patients with IBD switched from the Moderna 2-dose series to the Pfizer vaccine for their third dose. The median age of patients with IBD was significantly lower than that of HC (median, 38 [IQR, 30–49] versus 42 [IQR, 35–58], respectively; P = .033). The median age of patients with IBD who received a third dose was significantly greater than that of those who completed only the 2-dose series (median, 48 [IQR, 38–60] versus 41 [IQR, 34–52], respectively; P = .003). The characteristics of the groups were otherwise similar.

Table 1.

Study participant characteristics.a

| Characteristic | IBD subjects | IBD subjects | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third dose (n = 85)b | Two-dose series (n = 139)c | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 48 (38–60) | 41 (34–52) | .003 |

| Male, n (%) | 38 (44.7) | 71 (51) | .35 |

| Type of IBD | |||

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | 55 (64.7) | 96 (69.1) | .44 |

| Ulcerative colitis, n (%) | 30 (35.3) | 42 (32.2) | |

| IBD unclassified | - | 1 (0.7) | |

| Vaccine data | |||

| Two-dose series | |||

| Moderna, n (%) | 37 (43.5) | 67 (48.2) | .58 |

| Pfizer, n (%) | 48 (56.5) | 72 (51.8) | |

| Third dose | |||

| Moderna, n (%) | 35 (41.2) | - | |

| Pfizer, n (%) | 50 (58.8) | - | |

| Time between completion of 2-dose series and third dose, days, median (IQR) | 149 (132–167) | - | |

| IBD treatment | |||

| Nonsystemic immunosuppression,d n (%) | 24 (28.2) | 31 (22.3) | .34 |

| Aminosalicylate or no IBD therapy, n (%) | 3 (3.5) | 17 (12.2) | |

| Vedolizumab monotherapy, n (%) | 21 (24.7) | 14 (10.1) | |

| Duration of therapy,e months, median (IQR) | 36 (17–54) | 26 (16–47) | .41 |

| Systemic immunosuppression,f n (%) | 61 (71.8) | 108 (77.7) | .34 |

| Thiopurine monotherapy, n (%) | 6 (7.1) | 14 (10.1) | |

| Anti-TNF monotherapy, n (%) | 31 (36.5) | 59 (42.4) | |

| Anti-TNF combination therapy, n (%) | 12 (14.1) | 12 (8.6) | |

| Ustekinumab monotherapy or combination therapy, n (%) | 9 (10.6) | 15 (10.8) | |

| Tofacitinib monotherapy, n (%) | 2 (2.4) | 6 (4.3) | |

| Systemic corticosteroid therapy, n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (5.8) | |

| Duration of therapy, months, median (IQR) | 42 (18–117) | 43 (14–85) | .76 |

| Serum antibody concentrations | |||

| Detectable antibody concentrations, n (%) | 85 (100) | 135 (97.1) | .12 |

| Serum antibody concentrations, mg/mL, median (IQR) | 68 (32–147) | 31 (16–6.1) | <.001 |

| Time between vaccine dose and antibody measurement, days, median (IQR) | 37 (32–47) | 32 (29–34) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Completed the 2-dose series and had serum antibody concentrations measured 28–35 days thereafter.

Completed third dose and had serum antibody concentrations measured 28–65 days thereafter.

Absence of IBD therapy, mesalamine monotherapy, or vedolizumab monotherapy.

Subjects with an absence of IBD therapy were omitted from the calculation of the duration of therapy.

Thiopurine monotherapy (ie, azathioprine, mercaptopurine), anti-TNF monotherapy, anti-TNF combination therapy (ie, plus antimetabolite), ustekinumab monotherapy or combination therapy, tofacitinib, or systemic corticosteroid therapy (ie, any of the aforementioned groups plus systemic corticosteroid).

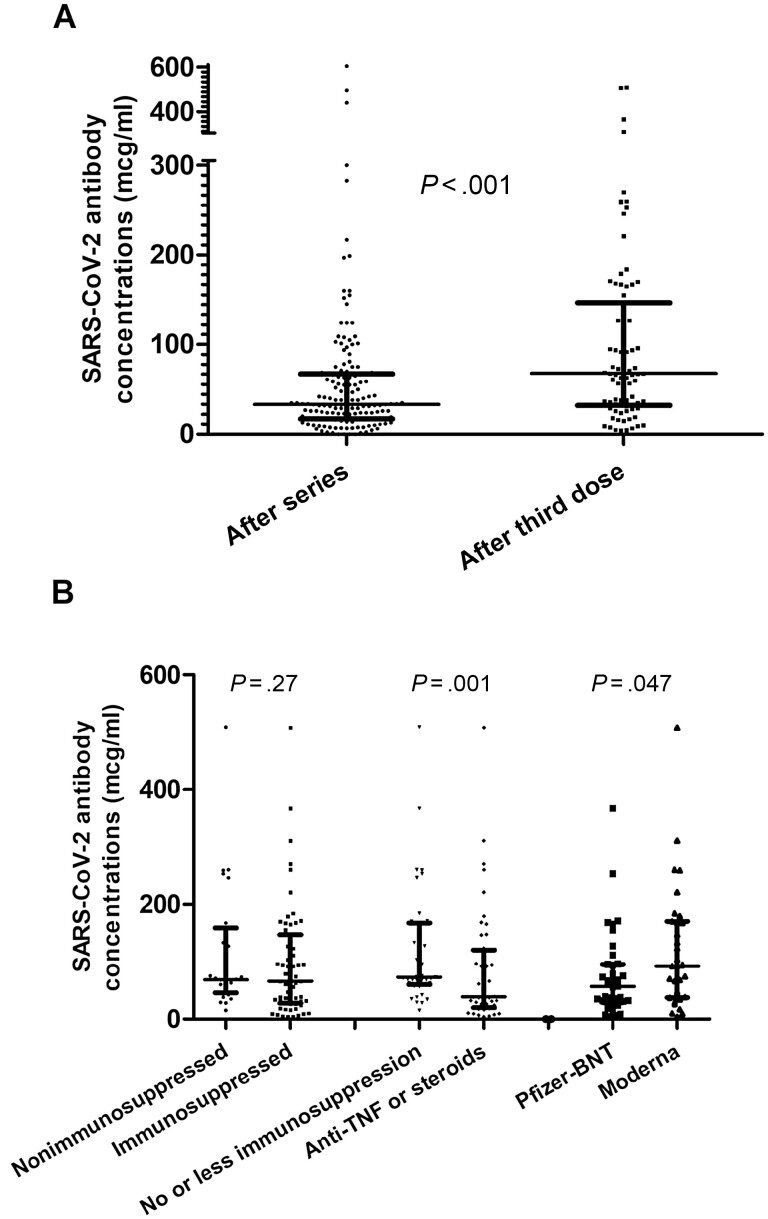

In patients with IBD, antibody concentrations were significantly higher following a third dose in comparison to the 2-dose series (median, 68 [IQR, 32–147] versus 31 [IQR, 16–61], respectively; P < .001; Figure 1A). There were 135 patients with IBD (97.1%) who had detectable antibody concentrations at t1, while all 85 patients (100%) had detectable antibody concentrations at t2 (P = .12). Of the 2 patients with IBD who were seronegative at t1 and received a third dose, each had detectable antibody concentrations (mean, 6.25; SD, 2.1) at t2; 1 patient was on anti-TNF monotherapy, and the other was on tofacitinib.

Figure 1.

A, Serum antibody concentrations in patients with IBD following the 2-dose series versus the third dose (median, 31 [IQR, 16–61] versus 68 [IQR, 32–147], respectively; P < .001). B, Left: serum antibody concentrations following the third dose in patients with IBD on nonimmunosuppressive therapy versus immunosuppressive therapy (median, 69 [IQR, 46–159] versus 66 [IQR, 28–147], respectively; P = .27). Nonimmunosuppressive therapy was defined as the absence of IBD-directed therapy or receipt of treatment with mesalamine monotherapy or vedolizumab monotherapy. Immunosuppressive therapy was defined as thiopurine monotherapy (ie, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine), anti-TNF monotherapy, anti-TNF combination therapy (ie, plus antimetabolite), ustekinumab monotherapy or combination therapy, tofacitinib, or systemic corticosteroid therapy (ie, any of the aforementioned groups plus systemic corticosteroids). Middle: subgroup analysis with serum antibody concentrations following the third dose in patients with IBD on “no or less immunosuppression” versus anti-TNF monotherapy, anti-TNF combination therapy, and systemic corticosteroid therapy (median, 73 [IQR, 60–167] versus 39 [IQR, 20–120], respectively; P < .001). “No or less immunosuppression” was defined as the absence of IBD-directed therapy or receipt of treatment with mesalamine monotherapy, vedolizumab monotherapy, thiopurine monotherapy, or ustekinumab monotherapy or combination therapy. Tofacitinib was excluded from the subgroup analysis due to the small sample size. Right: serum antibody concentrations for patients with IBD that received 3 Moderna doses versus 3 Pfizer doses (median, 94 [IQR, 38–170] versus 62 [IQR, 31–96], respectively; P = .047). Units of serum antibody concentrations are reported as mcg/ml. Abbreviations: BNT, BioNTech; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

At t2, antibody concentrations were similar between patients with IBD on immunosuppressive therapy and nonimmunosuppressive therapy (median, 69 [IQR, 46–159] versus 66 [IQR, 28–147], respectively; P = .27; Figure 1B). A subgroup analysis revealed that those on systemic corticosteroids, anti-TNF monotherapy, and anti-TNF combination therapy had significantly lower antibody concentrations at t2 than patients that were not (median, 39 [IQR, 20–120] versus 73 [IQR, 60–167], respectively; P < .001). Serum antibodies were significantly higher at t2 for patients with IBD who received 3 Moderna doses compared to those who received 3 Pfizer doses (median, 94 [IQR, 38–170] versus 62 [IQR, 31–96], respectively; P = .047).

Although HC had higher antibody concentrations compared to patients with IBD at t1 (median, 120 [IQR, 88–190] versus 31 [IQR, 16–61], respectively; P < .001), HC had lower antibody concentrations than patients with IBD at t2 (median, 17 [IQR, 11–22] versus 68 [IQR, 32–147], respectively; P < .001).

Discussion

All patients with IBD who received a third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose demonstrated a humoral immune response. Median antibody concentrations were higher following a third dose than after the 2-dose series. These findings are similar to those reported in other immunosuppressed patient populations with autoimmune disease, but are distinct from findings in patients with solid organ transplant, since all immunosuppressed patients had an immune response following 3 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine doses, compared to a humoral immune response rate of 49% to 68% in solid organ transplant recipients.9–12 Furthermore, those who completed a 3-dose Moderna series had higher antibody concentrations than those who completed a 3-dose Pfizer series, which is similar to previously reported findings regarding the 2-dose series.4

A subgroup analysis revealed that patients on systemic corticosteroids, anti-TNF monotherapy, and anti-TNF combination therapy had relatively lower antibody concentrations than patients who were not, suggesting that immune-modifying therapy may impact the humoral immune response to COVID-19 vaccines, as seen in the Coronavirus Risk Associations and Longitudinal Evaluation-IBD (CORALE-IBD), HERCULES, and Partnership to Report Effectiveness of Vaccination in Populations Excluded from Initial Trials of COVID (PREVENT-COVID) studies.3–5 Our findings that those on anti-TNF monotherapy had lower antibody concentrations is limited due to the small sample size, as this relationship has not been established in other cohorts. Moreover, this effect may be related to how the subgroup analysis was performed. Those on anti-TNF monotherapy were grouped with those on anti-TNF combination therapy and systemic corticosteroids, which are medication categories that have been associated with an attenuated humoral immune response in other vaccines; thus, these subgroup analyses are hypothesis-generating.13

It is important to note that differences in antibody concentrations may not correspond to differences in clinical outcomes, as the relationship between antibody concentrations and clinical outcomes is not known. Measuring serum antibody concentrations evaluates solely the humoral immune response to vaccination, neglecting cell-mediated immunity and other components of a vaccine-induced immune response. Having an antibody response is likely the most relevant serologic endpoint in evaluating humoral immunity, since it provides objective evidence of a vaccine-induced immune response. Clinical endpoints are also relevant targets of vaccine efficacy. Receipt of a third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose has increased vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization from 69% to 88% in adults with immunocompromising conditions, including a wide spectrum of conditions.6

In August 2021, the ACIP recommended an additional dose to the primary series for those who are moderately-to-severely immunocompromised.14 This recommendation was largely based on evidence that many solid organ transplant recipients did not mount an antibody response to the primary 2-dose series but went on to demonstrate an improved humoral response to a third dose, and these findings were subsequently extrapolated to other similarly immunosuppressed populations.11,15 This additional dose to the primary series, a 3-dose series, is intended for people who likely did not mount an immune response after initial vaccination. In November 2021, the ACIP recommended a booster dose 6 months after completion of the 2-dose mRNA vaccine series for all adults, and a potential fourth dose for those who are moderately-to-severely immunosuppressed and completed a 3-dose series.14 Supporting evidence for booster doses included evidence of waning humoral immunity in the general population following COVID-19 vaccination (which we observed in our HC cohort),16 a high incidence of breakthrough infection among vaccinated health-care workers and the general population,17,18 and a reduction in the incidences of infection and severity of illness following booster receipt.19,20 In our cohort, patients received a third dose a median of 149 days after the second dose. Previous studies demonstrated that a 2-dose primary series is sufficient to render a humoral immune response in patients with IBD.4 As such, this study essentially evaluates the humoral effects of booster doses in patients with IBD.

The ACIP recently revised their guidance for booster doses, preferentially recommending an mRNA booster dose 5 months after the primary series for all adults and 3 months after the third dose for those who are moderately-to-severely immunocompromised.21 Patients with IBD on thiopurines, anti-TNF therapy, or systemic corticosteroids qualify for a fourth dose per ACIP recommendations.21 Similar to prior vaccine recommendations from the ACIP for those who are considered moderately-to-severely immunocompromised, much of the data came from the solid organ transplant population, with concerns of waning or unmeasurable serum antibodies after 3 doses of an mRNA vaccine and improved immunogenicity after a fourth dose.22 In contrast, it appears that patients with IBD sustain humoral immunity over time, with 1 study showing that all 75 participants, all of whom were on a form of immune-modifying therapy, maintained measurable serum antibody concentrations 6 months after a 2-dose primary series.23 It is important to note that patients with IBD have higher rates of humoral immune response to COVID-19 vaccines than solid organ transplant recipients or those treated with B cell–depleting therapies, as described above. Previous studies have described a 95% to 99% humoral immune response rate following vaccination with a 2-dose mRNA vaccine series in patients with IBD.3–5 Herein, we observed a humoral immune response in all patients following receipt of 3 doses. Moreover, a recent report from the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for IBD (SECURE-IBD) registry demonstrated that among patients with IBD on various forms of IBD-directed therapy, only those on systemic corticosteroid therapy appear to be at relatively greater risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes.24 Those who would most likely benefit from a fourth mRNA COVID-19 vaccine dose include solid organ transplant recipients, those on systemic corticosteroids at the time of vaccination, those on concomitant therapies associated with a lower COVID-19 vaccine response (mycophenolate or B cell–depleting therapies), those who have comorbidities associated with adverse COVID-19 outcomes, and potentially those who received their third dose roughly ≥6 months prior.

Our study has several strengths. We evaluated humoral immunogenicity in patients on stable medication regimens (median duration of treatment of 39 months in those who received a third dose), which permitted us to assess the effects of IBD-directed therapy on the immune response to vaccination. We also included an HC reference population that received the 2-dose primary series but did not receive a third dose. Our study is limited in its sample size, small representation of certain treatment regimens, and the absence of a reference HC population that received a third dose. Population differences between the HC and IBD cohorts, in addition to differences between IBD patients who received a third dose and those who only completed the 2-dose series, may have contributed to findings.

In conclusion, all patients with IBD exhibited a humoral immune response following a third COVID-19 mRNA vaccine dose, and this response may be blunted by certain immune-modifying therapies. The role of serum antibody concentrations as a correlate of immunity has not been definitively established. Further studies are needed to investigate the durability of humoral immunity, in addition to other aspects of the adaptive immune response, following COVID-19 vaccination in the IBD population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the subjects who participated in the study, the specialty pharmacists at University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health for their assistance, and the staff at the Office of Clinical Trials at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for their work.

Contributor Information

Trevor L Schell, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Keith L Knutson, Department of Immunology, Mayo Clinic Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Sumona Saha, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Arnold Wald, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Hiep S Phan, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Mazen Almasry, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Kelly Chun, Labcorp, R&D and Specialty Medicine, Burlington, NC, USA.

Ian Grimes, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Megan Lutz, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Mary S Hayney, School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Francis A Farraye, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA.

Freddy Caldera, Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health, Madison, WI, USA.

Author Contributions

T.L.S.: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript. F.C.: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, and guarantor of the article. K.L.K.: analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript. S.S.: critical revision of the manuscript. A.W.: critical revision of the manuscript. H.S.P.: acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript. M.A.: acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript. K.C.: acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript. I.G.: critical revision of the manuscript. M.L.: critical revision of the manuscript. M.S.H.: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript. F.A.F.: analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Takeda Pharmaceuticals and American College of Gastroenterology.

Conflicts of Interest

F.C. has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and has been a consultant for Takeda, Arena Pharmaceuticals, GSK, and Celgene. F.A.F. is a consultant for Arena, BMS, Braintree Labs, GSK, Innovation Pharmaceuticals, Iterative Scopes, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sebela and sits on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for Lilly and Theravance. M.S.H. is a consultant for GSK Vaccines and Seqirus and has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Dynavax, and Sanofi. K.C. is an employee of Labcorp.

References

- 1. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, et al. Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):305–315. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2116846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heil EL, Kottilil S. The goldilocks time for remdesivir — is any indication just right? N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):385–387. doi: 10.1056/nejme2118579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melmed GY, Sobhani K, Li D, et al. Antibody responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1768–1770. doi: 10.7326/M21-2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caldera F, Knutson KL, Saha S, Wald A, Phan HS, Chun K. Humoral immunogenicity of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines among patients with inflammatory bowel disease and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(1):176–179. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kappelman MD, Weaver KN, Boccieri M, et al. Humoral immune response to messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1340–1343.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tenforde MW, Patel MM, Gaglani M, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalization among immunocompetent and immunocompromised adults — United States, August–December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(4):118–124. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7104a2.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith R, Hubers J, Farraye FA, Sampene E, Hayney MS, Caldera F. Accuracy of self-reported vaccination status in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(9):2935–2941. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06631-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schell TL, Richard LJ, Tippins K, Russ RK, Hayney MS, Caldera F. High but inequitable COVID-19 vaccine uptake among patients with inflammatory bowel disease [published online ahead of print December 9, 2021]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Connolly CM, Teles M, Frey S, et al. Booster-dose SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with autoimmune disease: a case series. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):291–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hall VG, Ferreira VH, Ku T, et al. Randomized trial of a third dose of mRNA-1273 vaccine in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1244–1246. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2111462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, Couat C, Izopet J, Del Bello A. Three doses of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):661–662. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2108861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benotmane I, Gautier G, Perrin P, et al. Antibody response after a third dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients with minimal serologic response to 2 doses. JAMA. 2021;326(11):1063–1065. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caldera F, Ley D, Hayney MS, Farraye FA. Optimizing immunization strategies in patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(1):123–133. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mbaeyi S, Oliver SE, Collins JP, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendations for additional primary and booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(44):1545–1552.doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyarsky BJ, Werbel WA, Avery RK, et al. Antibody response to 2-dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine series in solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2021;325(21):2204–2206. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin EG, Lustig Y, Cohen C, et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine over 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):e84.doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, et al. COVID-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1474–1484. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2109072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mizrahi B, Lotan R, Kalkstein N, et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2-breakthrough infections to time-from-vaccine. Nat Commun. 2021;12(6379):1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26672-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M, et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against COVID-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1393–1400. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2114255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet. 2021;398(10316):2093–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02249-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall E. Updates to interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-02-04/08-COVID-Hall-508.pdf

- 22. Kamar N, Abravanel F, Marion O, et al. Assessment of 4 doses of SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA-based vaccine in recipients of a solid organ transplant. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):9–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frey S, Chowdhury R, Connolly CM, Werbel WA, Segev DL. Antibody response six months after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [published online ahead of print January 26, 2022]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ungaro RC, Brenner EJ, Agrawal M, Zhang X, Kappelman MD, Colombel J-F. Impact of medications on COVID-19 outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of more than 6000 patients from an international registry. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):316–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]