Abstract

The enzyme BesC from the β-ethynyl-L-serine biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces cattleya fragments 4-chloro-L-lysine (produced from L-Lysine by BesD) to ammonia, formaldehyde, and 4-chloro-L-allylglycine and can analogously fragment L-Lys itself. BesC belongs to the emerging family of O2-activating non-heme-diiron enzymes with the “heme-oxygenase-like” protein fold (HDOs). Here we show that binding of L-Lys or an analog triggers capture of O2 by the protein’s diiron(II) cofactor to form a blue μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate analogous to those previously characterized in two other HDOs, the olefin-installing fatty acid decarboxylase, UndA, and the guanidino-N-oxygenase domain of SznF. The ~ 5- and ~ 30-fold faster decay of the intermediate in reactions with 4-thia-L-Lys and (4RS)-chloro-DL-lysine than in the reaction with L-Lys itself, and the primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects (D-KIEs) on decay of the intermediate and production of L-allylglycine in the reaction with 4,4,5,5-[2H]-L-Lys, suggest that the peroxide intermediate or a reversibly connected successor complex abstracts a hydrogen atom from C4 to enable olefin formation. Surprisingly, the sluggish substrate L-Lys can dissociate after triggering the intermediate to form, thereby allowing one of the better substrates to bind and react. The structure of apo BesC and the demonstrated linkage between Fe(II) and substrate binding suggest that the triggering event involves an induced ordering of ligand-providing helix 3 (α3) of the conditionally stable HDO core. As previously suggested for SznF, the dynamic α3 also likely initiates the spontaneous degradation of the diiron(III) product cluster after decay of the peroxide intermediate, a trait emerging as characteristic of the nascent HDO family.

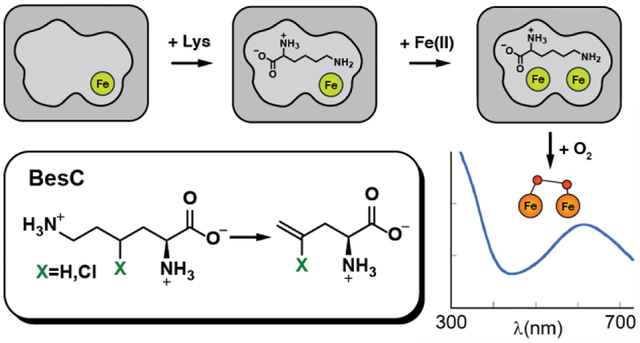

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A recent investigation into the biosynthesis of acetylenic amino acids described the pathway to β-ethynyl-L-serine (Bes) in Streptomyces cattleya (Scheme 1, top).1

Scheme 1.

The Bes biosynthetic pathway involving iron(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent halogenase, BesD, and desaturase/lyase, BesC. The lower path indicates that BesC also analogously fragments L-lysine.

The Bes pathway converts L-lysine into the namesake product in four steps. It is initiated by chlorination of C4 of L-Lys by the iron(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent aliphatic halogenase, BesD. The 4-Cl-L-Lys intermediate is then fragmented by BesC into formaldehyde, ammonia, and 4-Cl-L-allylglycine, with the chloride leaving group poised to permit further desaturation of the olefinic to the acetylenic amino acid in the next step. The BesC fragmentation cleaves C4-H, C5-C6, and C6-N7 bonds of the substrate in a net two-electron oxidation requiring dioxygen. This complex reaction is of interest mechanistically, as pathways initiated by radical formation on either N7 (Scheme 2A) or C4 (Scheme 2B) can be formulated. Notably, the 4-Cl substituent installed by BesD is not strictly required: BesC can also fragment L-Lys itself to L-allylglycine (Scheme 1, bottom).1 BesC is also of interest for its membership in a nascent superfamily of O2-activating nonheme diiron enzymes sharing the “heme-oxygenase-like” fold (HDOs).2–8

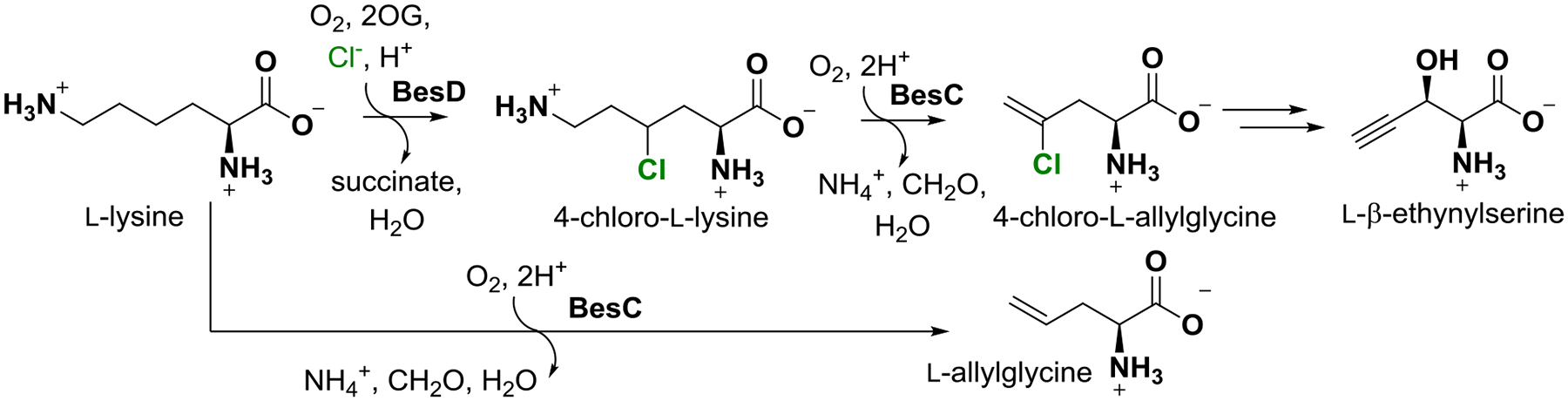

Scheme 2.

Mechanistic possibilities for BesC-mediated O2-dependent fragmentation of (4-Cl)-L-Lys. (A) Pathway initiated by ε-amine oxidation. (B) Pathways mediated by C4 HAT.

Bioinformatics analysis suggests the existence of > 10,000 HDOs,7 but, at the time this study was initiated, only a few had been definitively assigned enzymatic activities. Moreover, the first few HDOs to be characterized all share the intriguing trait of cofactor instability (explained in more detail below), which we have suggested might represent a key feature of a new functional paradigm – in which iron serves more as substrate than as cofactor – rather than an artifact of the manner in which they were studied. Therefore, the motivation for the present study was two-fold: (1) to shed light on the mechanism of the complex, olefin-installing fragmentation reaction catalyzed by BesC, including intermediates formed between its presumptive diiron cluster and dioxygen and the site of the (4-Cl)-L-Lys substrate targeted to initiate the oxidative fragmentation, and (2) to assess whether the enzyme shares with the initially characterized members of the emerging HDO family the protein and cofactor dynamics that thus far appear to distinguish its members from those of the longer-known ferritin-like nonheme diiron oxygenases (FDOs), as elaborated below.

Decades of study of ferritin-like non-heme diiron oxygenases and oxidases (FDOs) established a functional paradigm for these enzymes2,9 involving oxidative addition of O2 to the fully reduced form of the His2–3(Glu/Asp)4-coordinated cofactor to form a μ-(hydro)peroxodiiron(III) complex that either directly oxidizes the substrate by oxygen-atom transfer (OAT)10–12 or undergoes O-O-bond cleavage (reductively or without redox) to a high-valent [Fe2(III/IV) or Fe2(IV/IV)] intermediate that then initiates the relevant oxidation by abstracting hydrogen (hydrogen atom transfer, HAT).13–18 In many FDOs, binding of the substrate or an effector protein is required to “trigger” formation of the O2-reactive configuration of the cofactor by, for example, inducing a carboxylate shift or gating O2 access by protein conformational changes.19–24 With the exception of one of two reactions mediated by each of a pair of arylamine N-oxygenases, AurF and CmlI,12,25 completion of the relevant oxidation leaves a stable diiron(III) “product” form of the cluster that must undergo in situ reduction by a general electron-transfer protein (e.g., ferredoxin) or a specific reductase to reset the cofactor for the next turnover.2

Most FDOs bind iron stably, and multiple members of the family have been isolated with their diiron cofactors intact.11–12,26–28 By contrast, the first few characterized members of the emerging new family of nonheme-diiron oxidases and oxygenases sharing the heme-oxygenase-like protein fold (HDOs) were all initially characterized with, at most, one of the two iron ions of the cofactor bound.1,3,29–30 Indeed, the founding member of the HDO family, the olefin-forming fatty acid decarboxylase, UndA, was initially thought to use a mono-iron cofactor, because it was isolated and structurally characterized with iron bound only in what is now conventionally denoted subsite 1 of the diiron site.29 More recent biochemical and biophysical analysis of UndA showed that the functional iron cofactor is, as in the FDOs, dinuclear.4–5 One of these studies reported rapid accumulation and decay of a μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate upon mixing of the UndA•Fe(II)2•dodecanoic acid complex with O2-saturated buffer and further demonstrated the slow (minutes-hours) disintegration of the product diiron(III) cluster, thus rationalizing the prior observation of the mono-iron form.4 Subsequent analysis of the tri-domain enzyme, SznF, which produces the nitrosourea pharmacophore of the anticancer drug, streptozotocin, mirrored these observations on UndA.3,6–8 The central HDO domain of SznF catalyzes sequential OATs to Nδ of Nω-methyl-L-arginine and then to Nω’ of the hydroxylated intermediate before the enzyme’s C-terminal mono-iron cupin domain oxidatively rearranges the dihydroxy compound to Nω-methyl-Nw-nitroso-L-citrulline.3 A μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex was shown to accumulate upon exposure of the SznF•Fe(II)2 complex to O2 and to react efficiently with either Nω-methyl-L-arginine or the Nδ-hydroxylated intermediate, and the product diiron(III) cluster was again shown to disintegrate on the minutes-to-hours timescale.6 Interestingly, substrate triggering of intermediate formation was not seen for SznF, by contrast to the case of UndA. This dichotomy within the first two mechanistically characterized HDOs mirrors that seen in the FDOs, of which the N-oxygenases AurF and CmlI were shown not to require triggering by either the substrate or an accessory protein.4,6,12,25

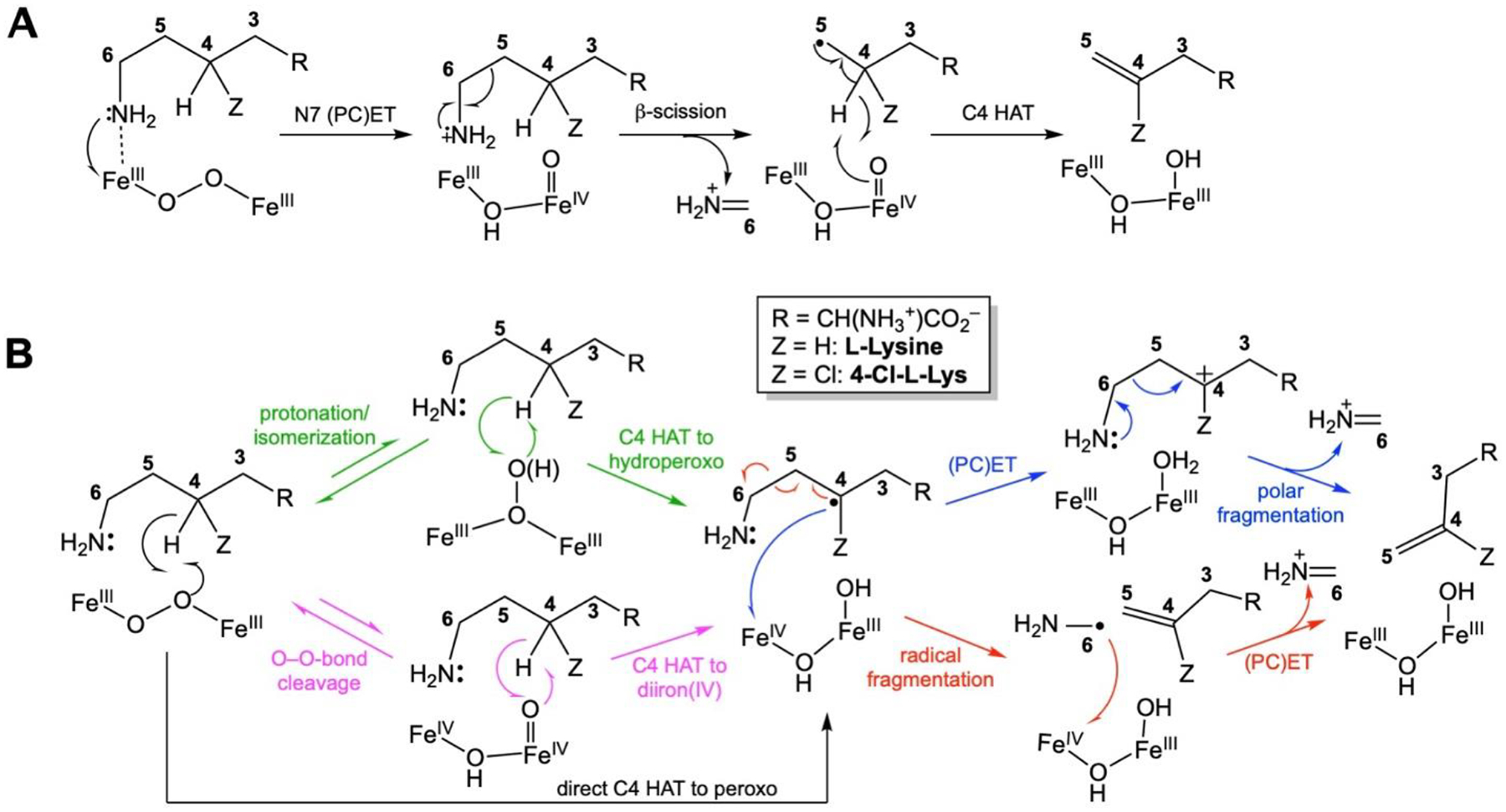

Recent x-ray crystallographic studies of SznF7 shed light on the instability of the diiron cofactor in its HDO domain,3 and structural characteristics shared with UndA4,29 suggested that the insight might be general to other (potentially all) enzymes in the emerging HDO family.2–8 A strategy of (i) preparing naive apo protein by heterologous expression in low-iron medium supplemented with Mn(II) to occupy the metal sites and prevent potentially deleterious cofactor cycling during protein production, (ii) chelation of the bound Mn(II) from the purified protein, (iii) crystallization of the apo protein, and (iv) soaking of crystals with Fe(II) yielded a structure of the SznF•Fe(II)2 complex with both sites almost fully occupied, the first such structure of an HDO.6–7 Comparison of apo and metallated structures revealed that one of the iron sites in the HDO domain (site 2) is not pre-formed7 (Fig. 1), by contrast to observations made on structures of apo FDOs.31–34 An 8-residue segment of the protein was seen to rearrange from a series of turns in the apo state to a canonical α-helix (part of α3) in the diiron(II) complex, in the process relocating a site 2 carboxylate ligand (D315) ~10 Å from the protein surface into the helical core.7 It was posited that dynamics of the modestly stable α3 could initiate the observed disintegration of the product diiron(III) complex. Given that a segment of α3 in UndA could not even be confidently modeled because of poor (or absent) electron density,4 this explanation for cofactor instability could be applicable also to the founding HDO. The structure of diiron(II) SznF also revealed an unexpected, additional carboxylate ligand that gives the iron in site 1 four protein-derived ligands (His2-carboxylate2) in its first coordination sphere.7 This extra carboxylate is not present in UndA (nor conserved in the majority of other hypothetical HDOs identified bioinformatically) but is conserved in the 2-aminoimidazole N-oxygenase RohS from the azomycin biosynthetic pathway,35 leading to the hypothesis that the presence of the ligand might be an identifying trait of heteroatom oxygenases in the HDO family. Moreover, the fact that, in UndA, the substrate carboxylate ligates Fe1 at essentially the same site4 led to the suggestion that such an interaction might contribute to substrate triggering in HDOs lacking the extra site 1 carboxylate.

Figure 1.

Metal loading in HDOs involves a conformational change of a core metal-binding helix. Comparison of (A) apo and (B) Fe(II)-loaded SznF reveals that core metal binding α-helix, α3 (pink), containing three iron ligands, undergoes a significant secondary structure transition upon cofactor assembly. This change causes site 2 metal ligand, D315, to shift >10 Å from its posiiton in the apo state (C) to coordinate Fe2 in the fully assembled structure (D). An x-ray strucure of apo BesC (E) also exhibits extensive disorder in helix α3 (pink). The BesC active site (F) lacks electron density for two metal binding ligands provided by this secondary structure. A sequence alignment (G) shows that BesC conserves key metal binding residues in core HDO secondary structures α1-α3. BesC does not conserve the additional carboxylate ligand (white sticks) in an auxiiliary motif, consistent with its function as a desaturase-lyase rather than N-oxygenase.

In this study, we subjected BesC and its complex oxidative fragmentation reaction to the experimental analysis that clarified the dynamic, dinuclear nature of the cofactors and the mechanisms of UndA and SznF.4,6–7 We present an x-ray crystal structure of the apo protein that confirms that BesC shares with UndA and SznF the flexible, conditionally stable α3. Moreover, we show that binding of L-lysine or an analog is required to drive formation of the cofactor in the first place – most likely by proper configuration of the site 2 ligands provided by α3; this observation rationalizes the requirement for substrate triggering that BesC shares with UndA (but not SznF).4,6 Once formed, the reduced cofactor can efficiently capture O2 in a relatively long-lived μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex spectroscopically similar to those in the other two HDOs.4,6 The markedly faster decay of the complex in the presence of L-Lys analogs modified at C4 (by H → Cl or C → S) and the normal primary C4 deuterium kinetic isotope effect (D-KIE) on its decay in the reaction with L-lysine imply that the complex (1) is an authentic intermediate and (2) either is, or reversibly interconverts with, the species that abstracts hydrogen from C4 to initiate the oxidative fragmentation, conclusions that comport with those reached in another study that appeared while this work was in review (addressed in more detail below).36 Remarkably, once the substrate has promoted diiron(II) cofactor assembly and O2 capture, it can dissociate from the intermediate complex to allow a different (i.e., more reactive) substrate to bind and react. Decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate is, as previously shown for UndA and SznF,4,6 followed by spontaneous disintegration of the product diiron(III) cluster. The observations of a disordered α3 in the apo protein, substrate-driven cofactor assembly, substrate dissociation from the intermediate complex, and spontaneous loss of the oxidized cofactor in BesC all further consolidate the dynamic nature of the HDO architecture noted in the previous studies.4,6–7

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), anhydrous sodium phosphate, and dibasic potassium phosphate were purchased from DOT Scientific. The buffer 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), glycerol, and imidazole were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Kanamycin was purchased from Teknova. Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, L-β-homolysine and D-Lysine were purchased from Chem-Impex International. Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Ni-NTA) resin was purchased from Qiagen. L-Allylglycine was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company. 4,4,5,5-[2H2]-L-Lysine (d4-L-Lys) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. L-norleucine was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Trans-4,5-dehydro-DL-Lysine was purchased from Bachem. 6-Hydroxy-L-norleucine was purchased from Acrotein Chembio Inc. 4RS-Cl-DL-Lysine was purchased from Akos GmbH (Steinen, Germany). EZNA Plasmid DNA Mini Kit was purchased from Omega Bio-Tek. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reagents, Q5 DNA Polymerase Master Mix, restriction enzymes, restriction enzyme buffers, and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs. Escherichia coli (Ec) DH5α and Rosetta(DE3) competent cells were purchased from Novagen. 57Fe0 was purchased from ISOFLEX, USA. All other chemicals were purchased from Millipore Sigma.

Preparation of S. cattleya BesC.

Preparation of the apo protein used to determine the x-ray crystal structure is described in the Supporting Information. For the protein used in all other experiments, a tailored overexpression plasmid and modified culture and purification procedures were used, as described in detail below.

The coding region from an existing plasmid harboring the gene coding for an N-terminally-His6-tagged BesC1 was amplified by PCR using the primers shown in Table S2. The PCR product was incorporated into the pET28a(+) vector (Novagen) between its NdeI and Xhol restriction sites using standard molecular biology protocols. The sequence of the resulting pET28a-BesC construct was verified by Sanger sequencing (Penn State Genomics Core Facility).

The overproduction and purification protocol for BesC was adapted from methods previously described for overexpression of S. achromogenes SznF.6 The pET28a-BesC vector was used to transform Ec Rosetta(DE3) cells. Successful transformants were selected at 37 °C on LB-agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL). A single colony was used to inoculate a 5 mL Luria broth (LB) starter culture containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. The starter culture was grown at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 6 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000g for 5 min and resuspended in 5 mL of M9 medium.37 A 0.5 mL aliquot of this suspension was used to inoculate a 250 mL M9 starter culture supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 50 μM MnCl2 along with a trace metals cocktail38 (Table S3). The starter culture was incubated at 37 °C overnight (16 h) with shaking at 180 rpm. Aliquots of a starter culture were used to inoculate 1 L cultures of M9 medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 50 μM MnCl2 to an initial OD600 of 0.05. The cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking at 180 rpm to an OD600 of ~ 0.6 ‒ 0.8. After cooling on ice for 30 min with an additional supplement of 200 μM MnCl2, BesC overexpression was induced by addition of IPTG to 0.2 mM, and cultures were grown at 18 °C overnight (16–18 h) with shaking at 180 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000g and flash frozen in liquid N2. Typically, 8 L of culture yielded 15 g of frozen cell paste.

The frozen cells were resuspended in buffer A [100 mM sodium HEPES,100mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol (v/v), pH 7.5] supplemented with 80 μg/ml PMSF at a ratio of 5 mL buffer per g of cells. The suspended cells were disrupted via sonication on ice (QSonica 750 W, 20 kHz, 10 s pulse, 30 s off, 60% amplitude, 7 min 30 s total sonication time). The resulting lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 22,000g. This step and all subsequent protein purification steps were performed at 4 °C. The supernatant was applied to Ni(II)-nitrilotriacetate (NTA) agarose resin (1 mL resin per 5 mL lysate) and washed with 6 column volumes (CV) of buffer A. Bound proteins were eluted with buffer B [100 mM sodium HEPES, 100mM NaCl 250 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol (v/v), pH 7.5]. Fractions containing BesC, as determined by SDS-PAGE gel analysis with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, were pooled and concentrated in a 10 KDa molecular weight cutoff filtration device (PALL Corporation). To remove adventitiously bound metal ions, the protein was dialyzed overnight into 100 mM sodium HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.5. To remove EDTA, the protein was dialyzed against 100 mM sodium HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, pH 7.5 for at least 4 h, followed by further separation from small molecules by passage through a pre-packed PD-10 column (GE Healthcare). Protein concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm using a calculated molar extinction coefficient (ε280nm) of 34,400 M−1 cm−1 and a predicted molecular weight of 29.4 kDa.39 For use in rapid kinetics experiments, protein samples were rendered anoxic on a Schlenk line after purification. Three sets of ten gentle evacuation-refill cycles (with argon gas) were performed, and the anoxic protein was flash frozen and stored in liquid N2.

Rapid Kinetics Experiments.

Prior to rapid mixing to initiate reactions, reactant solutions were prepared from anoxic solutions of apo BesC, Fe(II), and substrates in an MBraun anoxic chamber. Stopped-flow absorption experiments were performed at 5 °C in an Applied Photophysics Ltd. (Leatherhead, UK) SX20 stopped-flow spectrophotometer housed in the MBraun chamber and equipped with either a photodiode-array (PDA) or photomultiplier tube (PMT) detector, as previously described.6 The path length was 1 cm, except in reactions with ferrozine, in which case it was 0.2 cm. Samples to monitor the BesC reaction by Mössbauer spectroscopy were prepared by the freeze-quench method according to previously published procedures.40 Mössbauer spectra were recorded on a spectrometer from SEECO (Edina, MN) equipped with a Janis SVT-400 variable-temperature cryostat. The reported isomer shift is given relative to the centroid of the spectrum of α-iron metal at room temperature. External magnetic fields were applied parallel to direction of propagation of the γ radiation. Simulations of the Mössbauer spectra were carried out using the WMOSS spectral analysis software from SEECO (www.wmoss.org, SEE Co., Edina, MN). More detailed procedures for each experiment can be found in the Supporting Information and figure legends.

Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effect (D-KIE) on Decay of the μ-Peroxodiiron(III) Complex with L-Lys and 4,4,5,5-[2H4]-L-Lys.

Reactions were carried out with an Agilent 8453 UV-Visible spectrophotometer with a temperature-controlled cuvette holder inside an MBraun anoxic chamber. For reactions carried out at 5 °C, an initial reactant solution of 0.2 mM BesC, 0.4 mM Fe(II), 12 mM L-Lys or 4,4,5,5-[2H4]-L-Lys (d4-L-Lys), and 124 mM NaCl in 100 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5) and 5% (v/v) glycerol was manually mixed with an equal volume of O2-saturated buffer (~1.8 mM). For reactions carried out at 22 °C, a reactant solution of 0.4 mM BesC, 0.8 mM Fe(II), 24 mM L-Lys or d4-L-Lys, and 148 mM NaCl in 100 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.5) and 5% glycerol (v/v) was manually mixed with three volume equivalents of O2-saturated buffer (~1.2 mM). Spectra were collected at 5-s intervals for 1000–7200 s after mixing.

Analysis of BesC Reactions by Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

Reactions were initiated by mixing anoxic solutions of BesC, Fe(II) and substrates with O2-saturated buffer and terminating the reactions by addition of 1.5 volumes of methanol containing 1% formic acid and, when available, an appropriate isotopic internal standard. Details of reaction conditions are provided in the Supporting Information and the figure legends. Quenched reaction solutions were filtered to remove protein (described in the Supporting Information) and analyzed on an Agilent 1260 HPLC using a SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC (5 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm) with buffer A (90% acetonitrile, 10% water, 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 4) and buffer B (10% acetonitrile, 90% water, 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 4). A linear gradient from 80% to 40% A over 16 min and held at 40% A for 1 min at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Mass spectra were acquired in positive ionization mode on an Agilent 6460 QQQ. Source and acquisition parameters were: gas temperature 300 °C, drying gas 11 L/min, nebulizer 45 psi, capillary voltage 3500 V, fragmentor 60–76 V, and acquisition rate 3 spectra/s.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

An x-ray crystal structure of apo BesC shows that it also has a disordered α3. Early in the initial characterization of the Bes pathway,1 we solved a structure of apo BesC (Table S1). As expected, the x-ray diffraction data revealed the absence of significant electron density arising from the cofactor (Fig. S1). Additionally, although the majority of the HDO architecture could be reliably modeled into the electron density, there was inadequate density to model residues 203–212 within helix 3 (α3), which, in the holo-SznF structure, provides multiple ligands for iron site 2. The absence of density for this segment implies that it is flexible and disordered. A similar phenomenon was observed for the corresponding segments of both SznF and UndA in crystal structures of each protein obtained from samples for which reconstitution with iron had been attempted. 3–4,7,29

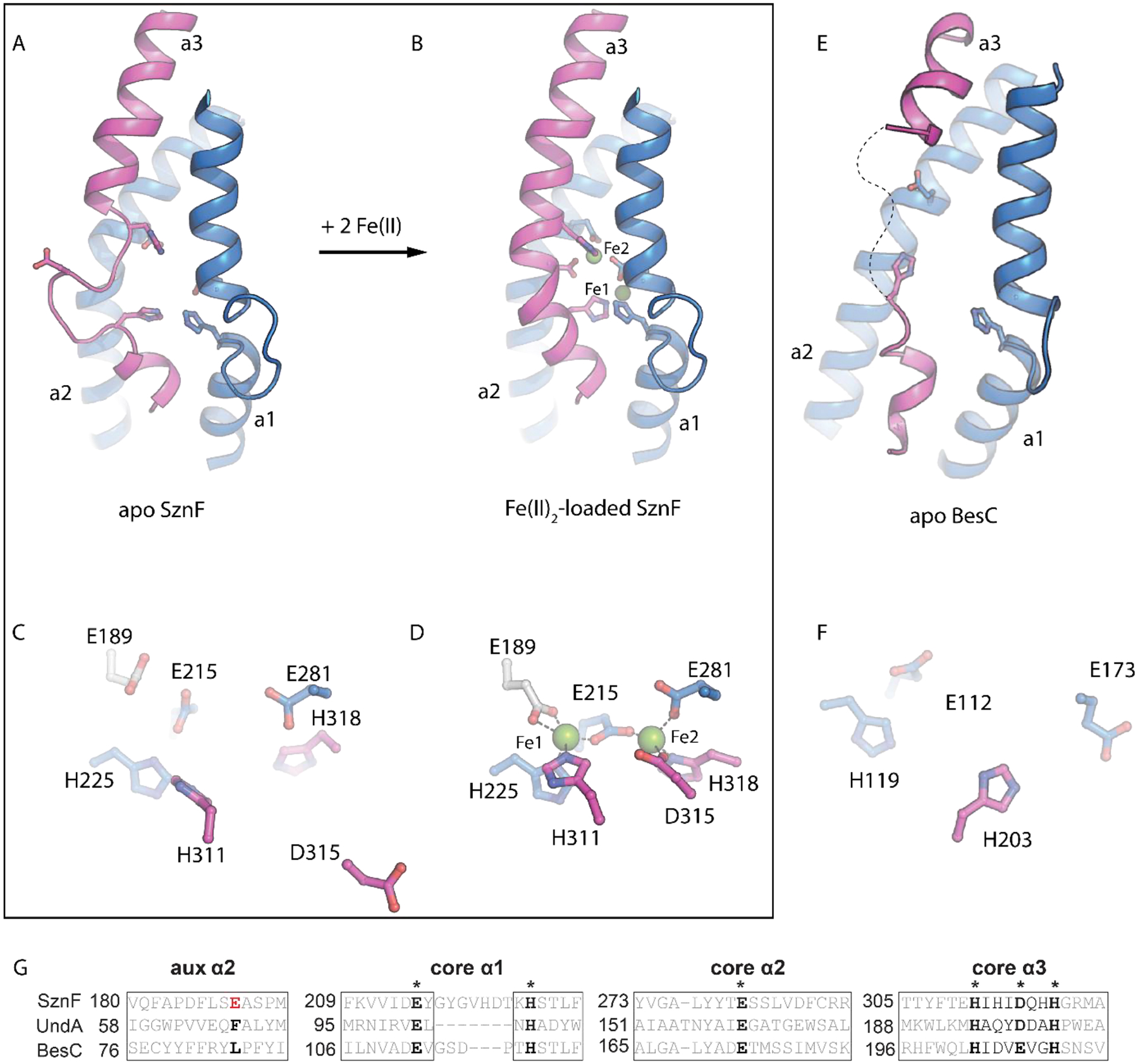

Substrate-triggered formation of a 618-nm-absorbing intermediate in BesC.

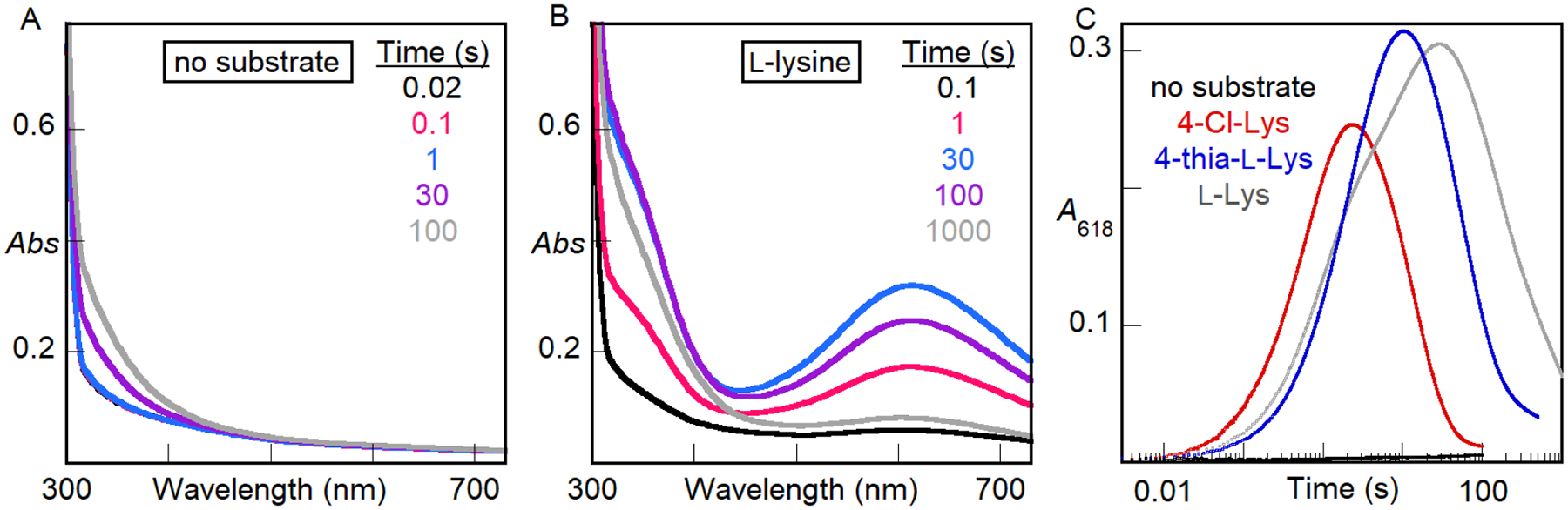

Whereas rapid mixing of an anoxic solution containing BesC (initially apo) and ≥ 2 molar equivalents of Fe(II) with O2-saturated buffer resulted only in slow development of stable ultraviolet absorption (Fig. 2A), inclusion also of L-Lys, 4-Cl-Lys (racemic at both C2 and C4), or S-(2-aminoethyl)-L-cysteine (4-thia-L-Lys) in the protein reactant solution led to rapid development of an intense, transient visible absorption feature centered at ~ 618 nm (Fig. 2B, C). This feature is reminiscent of those associated with μ-peroxodiiron(III) complexes in UndA,4 SznF,6 and multiple FDOs.28,41–43 Of the two previously studied HDOs, substrate triggering of intermediate formation was also seen for UndA4 but not for SznF.6 BesC lacks the extra site 1 carboxylate ligand seen in the x-ray crystal structure of Fe(II)2-SznF and, in accordance with the correlation noted in that study, is also triggered by substrate binding.7

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra acquired after rapid mixing at 5 °C of an anoxic solution of BesC (0.30 mM) and Fe(II) (0.60 mM, 2 molar equiv) in the (A) absence or (B) presence of 1 mM L-Lys with an equal volume of O2-saturated buffer. (C) Kinetic traces showing the accumulation and decay of the absorbing intermediate as a function of time in the presence of 1 mM (initial concentration) of the substrate indicated by the color-coded legend. A control lacking substrate is shown in black.

In the reaction with L-Lys at 5 °C, complete decay of the transient absorption feature requires tens of minutes, but in the reactions with 4-thia-L-Lys and 4-Cl-L-Lys, the decay is ~ 5-fold and ~ 30-fold faster, respectively (Fig. 2C). The sensitivity of the lifetime of the complex to substrate modifications at C4 (H → Cl or C → S), the site of the only C–H bond that is cleaved in the fragmentation reaction (Fig. S2, showing formation of primarily d3-L-allylglycine from d4-L-Lys), implicates the absorbing species as an authentic intermediate, a conclusion supported by the observations of primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects (D-KIE) presented below.

Mössbauer-spectroscopic evidence that the 618-nm-absorbing species is a μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex.

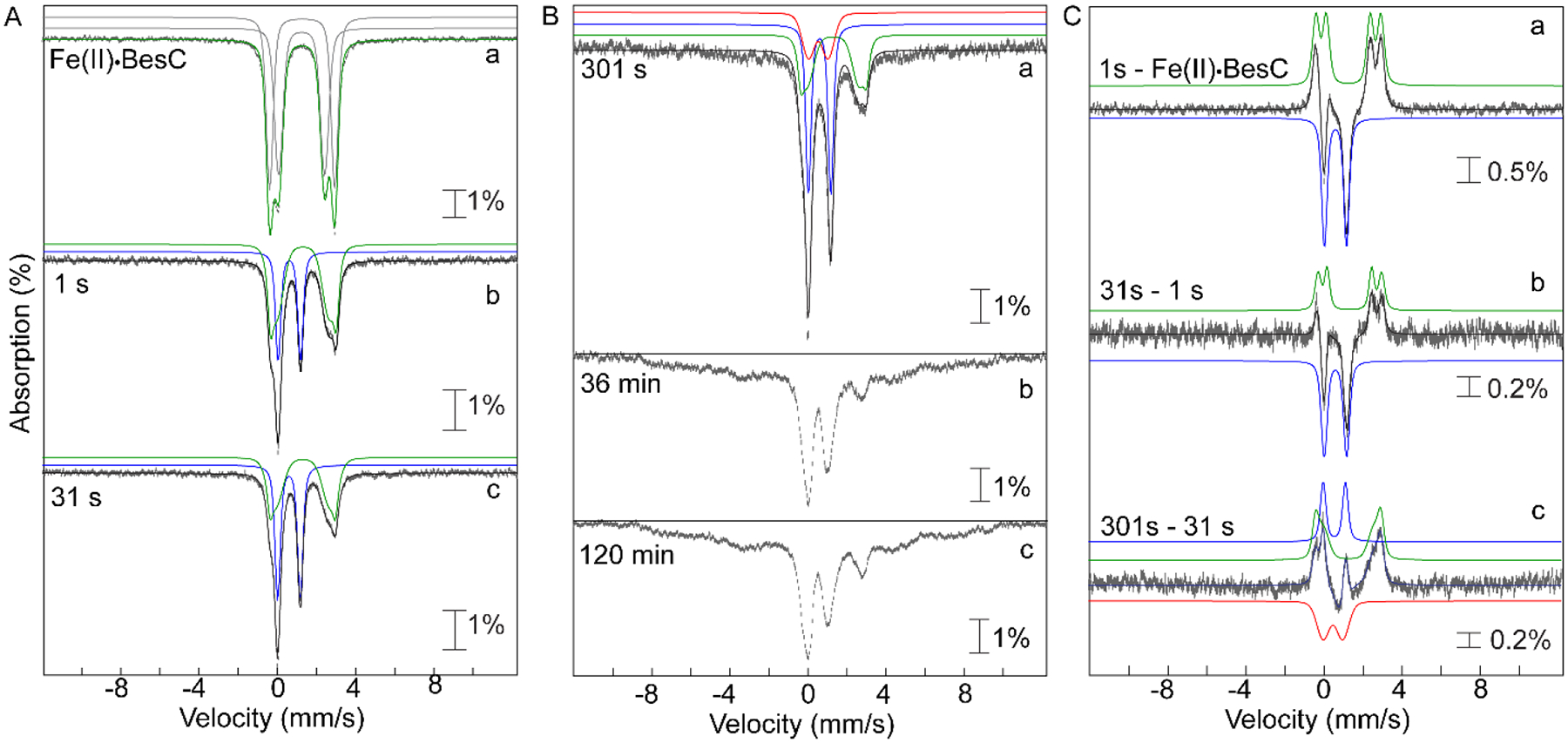

Mössbauer spectra – acquired at 4.2 K with a 53-mT field applied parallel to the γ beam – of samples prepared by freeze-quenching the BesC•Fe(II)•L-Lys/O2 reaction at times within the lifetime of the absorbing species confirm its assignment as a μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex. The spectrum of the frozen BesC•Fe(II)•L-Lys reactant solution (Fig. 3A, spectrum a) exhibits features that can be analyzed as two partially resolved quadrupole doublets with isomer shift (δ) and quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ) parameters characteristic of high-spin Fe(II) ions (δ ~ 1.2 mm/s, ΔEQ ~ 3 mm/s; the actual parameters used to generate the green fit line are given in Table S4). The spectra of samples frozen between 1 s and 120 min after a mix (at 5 °C) of this solution with an equal volume of O2-saturated buffer exhibit diminished contributions from these quadrupole doublet features, reflecting oxidation of the Fe(II). At shorter reaction times (e.g., 1 s, Fig. 3A, spectrum b), a new quadrupole doublet develops (blue lines), reaching its maximum intensity in the sample frozen at 31 s (Fig. 3A, spectrum c), near the time of maximum A618 in the stopped-flow experiments. From the difference of the experimental spectra of the 1-s freeze-quench and reactant samples (Fig. 3C, spectrum a), the parameters of this new doublet were determined to be δ = 0.58 mm/s and ΔEQ = 1.15 mm/s (Fig. S3). These parameters are similar to those reported for the ~ 600-nm-absorbing, antiferromagnetically coupled, high-spin μ-peroxodiiron(III) enzyme intermediates in SznF,6 UndA,4 and FDOs (as well as synthetic models thereof), thus confirming the assignment of the BesC intermediate as such a complex.2,9,44–45 Between reactions times of ~ 30 s and ~ 300 s, the spectrum of the intermediate partially decays, giving rise to a new quadrupole doublet (Fig. 3B, spectrum a). Subtractions of the spectra of the 31-s and 1-s samples (Fig. 3C, spectrum b) and of the 301-s and 31-s samples (Fig. 3C, spectrum c) resolve the features of the new doublet (red lines) and define its parameters as δ = 0.51 mm/s and ΔEQ = 1.00 mm/s (Fig. S4). This spectrum is attributed to the diiron(III) product state generated upon decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate. At much longer reaction times (tens-hundreds of minutes), the diiron(III) complex also begins to decay, as paramagnetic features characteristic of uncoupled high-spin Fe(III) ions – either bound in mononuclear fashion within BesC or free in solution – develop. By a reaction time of 120 min, the paramagnetic features dominate the spectrum, contributing more than 60% of the total absorption area (Fig. S5). These observations establish that BesC behaves as UndA and SznF in undergoing spontaneous disintegration of its diiron(III) product cluster.4,6 As previously noted, this behavior contrasts with that of FDOs, which stably bind their diiron(III) cofactors, and emphasizes the dynamic nature and quasi-stability of the HDO architecture that contributes the two iron sites.

Figure 3.

4.2 K Mössbauer spectra, acquired with a 53 mT magnetic field applied parallel to the direction of propagation of the γ-beam, of freeze-quenched samples from the reaction of Fe(II)·BesC with O2. The experimental spectra are depicted by grey vertical bars of heights reflection the standard deviations of the absorption values during acquisition of the spectra. The black solid lines are the overall simulated spectra, and the colored lines are theoretical spectra illustrating the fractional contributions from the Fe(II)·BesC reactant complex (green), the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate (blue), and the diiron(III) product (red), to the experimental spectra. Values of the parameters and relative areas of these spectra are provided in Table S3. (A) Spectra of samples freeze-quenched at short reaction times, during formation and decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate: (a) anoxic Fe(II)·BesC reactant complex; (b and c) spectra of samples quenched at 1 s and 31 s, respectively. (B) Spectra of samples frozen at longer reaction times: (a) 301 s, (b) 36 min, and (c) 120 min. These spectra demonstrate the disintegration of the diiron(III) “product” cluster and accumulation of uncoupled high-spin Fe(III) species at longer reaction times. (C) Difference spectra: (a) 1 s − Fe(II)·BesC reactant complex; (b) 31 s − 1 s; and (c) 301 s − 31 s. These spectra illustrate the changes associated with conversion of the Fe(II)·BesC reactant to the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate and its subsequent conversion to diiron(III) product.

Kinetic evidence that the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex or its reversibly connected successor abstracts H• from C4 of the substrate.

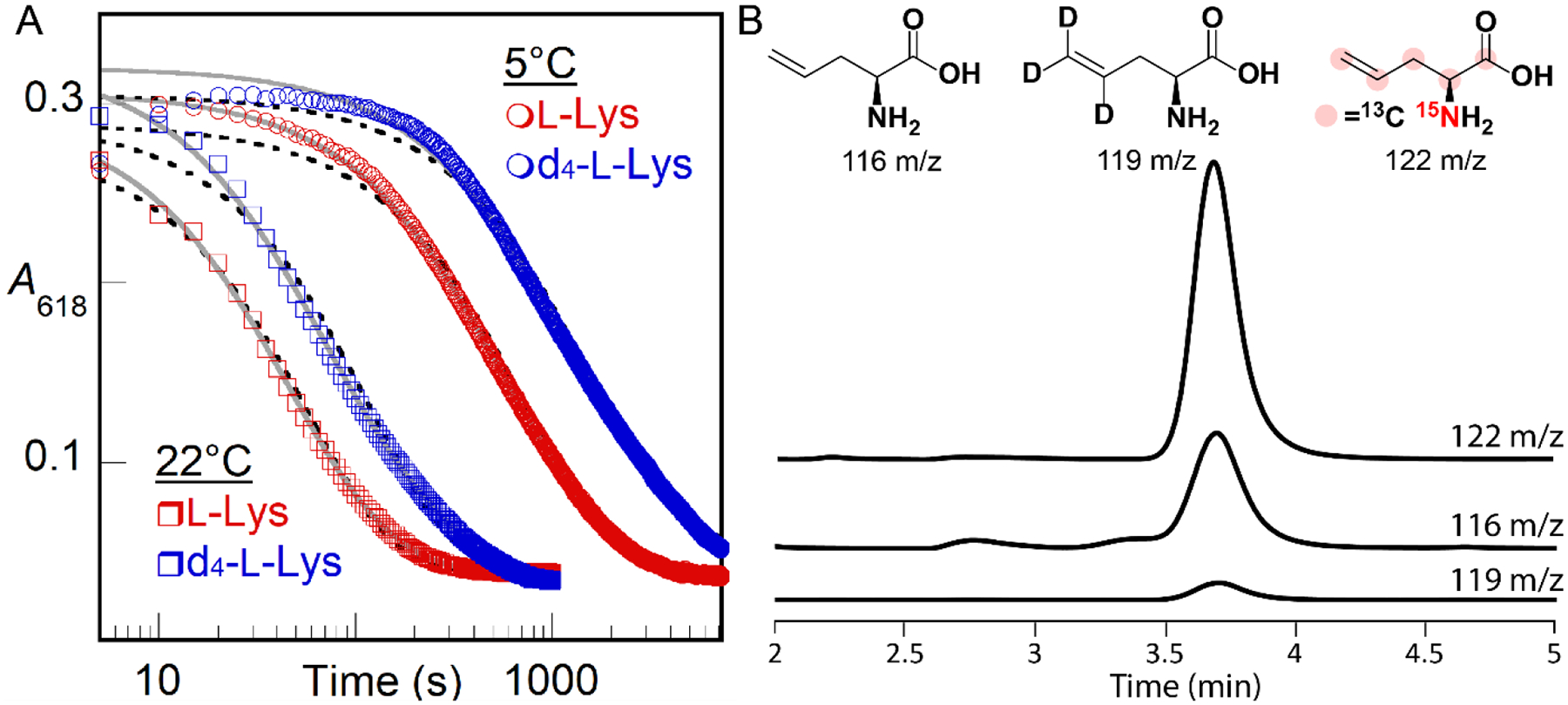

Comparison of the decay kinetics from reactions with L-Lys of natural isotopic abundance and 4,4,5,5-[2H4]-L-Lys (d4-L-Lys) at two temperatures reveals a normal deuterium kinetic isotope (D-KIE) at either temperature (Fig. 4A). Regression “fits” of the averaged kinetic traces from two trials for each isotopolog at each temperature by the equation for a single exponential decay (dashed lines in Fig. 4A) are not ideal but lead to an observed D-KIE (kobs,H/kobs,D) of 2.1 ± 0.1 at either temperature. Fits by the equation for two parallel decay processes (solid lines in Fig. 4A) are better (especially for the data from the reactions at 22 °C) and afford similar amplitudes for the two hypothetical decay processes and D-KIEs of 3.8 (5 °C) and 2.3 (22 °C) on the more isotope-sensitive, slower phase. These values are all too large to be associated with a secondary D-KIE, implying that the intermediate is involved in HAT from C4 of the substrate, most simply as the direct H• acceptor (Scheme 2B, black lower pathway). On the basis of similar evidence (an estimated D-KIE of 2.7), Manley et al. also recently surmised that the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex in BesC abstracts H• from C4 of the substrate.36 In their study, the authentic 4-Cl-L-Lys substrate was seen to afford faster decay and more efficient coupling to the olefinic product but an identical D-KIE on decay of the intermediate. Although it has been proposed in computational studies,46 little experimental evidence for HAT to a peroxodiiron(III) complex has been reported. The lone possible exception of which we are aware is the work by Lippard and co-workers showing direct reaction of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate, Hperoxo, in soluble methane monooxygenase with dialkyl ether substrates,41 which have C–H bonds that are, by virtue of the non-bonded electrons on the central oxygen, somewhat activated relative to the C4-H bonds in L-Lys.

Figure 4.

(A) A618nm-versus-time traces monitoring decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate in BesC after manual mixing of a solution containing BesC, Fe(II), and L-Lys (red traces) or d4-L-Lys (blue traces) with O2-saturated buffer [100 mM sodium HEPES, pH 7.5, 100mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol] at either 5 °C (circles) or 22 °C (squares). Final concentrations after mixing were 0.1 mM BesC, 0.2 mM Fe(II), 6 mM (d4)-L-Lys, and ~ 0.9 mM O2. Fits by the equations for single exponential decay (black dashed lines) and two parallel decay processes (solid gray lines) are shown. (B) LC-MS detection of products in single-turnover reactions of BesC (0.90 mM) after incubation with Fe(II) (1.8 mM) and d4-L-Lys or [13C6,15N2]-L-Lys (10 mM) containing L-allylglycine standard (0.050 mM) in 100 mM sodium HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol. Single ion monitoring (SIM) of the reaction with d4-L-Lys detected a diminished peak for d3-allylglycine at 119 m/z relative to the peak at 122 m/z for [13C5,15N]-L-allylglcine produced in the reaction with [13C6,15N2]-L-Lys. Peaks have been normalized to that from the L-allylglycine internal standard at 116 m/z.

The observed D-KIE, although sufficiently large to be assigned as a primary effect, is considerably less than those determined for HATs from unactivated carbon centers to oxidized iron intermediates in other enzymes.15,47–50 These D-KIEs can be very large (kH/kD > 50) as a consequence of the much greater contribution of quantum-mechanical tunneling to 1H transfer than to 2H transfer. A large intrinsic D-KIE on such a step can be kinetically masked by either (i) slow, reversible, disfavored conversion of the complex to a more reactive intermediate that is the actual H• abstractor (Scheme S1A) or (ii) decay of the absorbing complex through one or more additional, isotope-insensitive (i.e., unproductive) pathway(s) that become(s) dominant when the HAT-initiated, productive pathway is drastically slowed by a large intrinsic D-KIE (Scheme S1B).48,51 To assess whether the latter mechanism of kinetic masking is operant in BesC-catalyzed L-Lys fragmentation, we compared yields of the L-allylglycine product in single-turnover reactions with protium- and deuterium-bearing L-Lys isotopologs. To enable use of commercially available compound as an internal standard for both reactions, we used a commercial heavy-atom-labeled L-Lys ([13C6,15N2]-L-Lys, with 99% isotopic enrichment in both 13C and 15N) as the protium-bearing substrate and the d4-L-Lys for comparison. Given that the magnitudes of primary 13C- and 15N-KIEs are generally less than 1.1, we anticipated that any such effects would not obscure the vastly dominant impact of deuterium substitution on the reaction efficiency, as determined by LC-MS quantification of the [`13C5,15N]- and [4,5,5-2H3]-L-allylglycine products against the natural-isotopic-abundance standard (Fig. 4B). In six trials with each isotopolog at two different BesC concentrations [0.30 and 0.90 mM with 2 equiv Fe(II)], the [13C6,15N2]-L-Lys yielded a mean and range of 12 ± 3 times the quantity of L-allylglycine produced from 4,4,5,5-[2H4]-L-Lys, implying that the presence of deuterium severely uncouples decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex from L-allylglycine production. This uncoupling could arise either from simple derailment of the initiating HAT from C4 (Scheme 2B, black lower pathway), which would result in L-Lys not being transformed, or redirection of the intermediate to a different site, which would lead to formation of a different product. The observed rate constants for decay of the intermediate observed spectrophotometrically (kobs,H, kobs,D) will be the sum of the rate constants for both productive (kH or kD) and uncoupled decay (kunc) (Eq. 1 and 2), whereas the coupling efficiencies with the two

| (1) |

| (2) |

substrates (CEH and CED) will be given by ratios of kH and kD to the sum of rate constants for coupled and uncoupled (to L-allylglycine production) decay pathways (Eq. 3 and 4).

| (3) |

| (4) |

Even without knowledge of the precise values of the coupling efficiencies, a system of five independent equations can be solved for all five unknown parameters (kH, kD, kunc, CEH and CED) using the observed rate constants for intermediate decay (kobs,H = 0.0135 s−1 and kobs,D = 0.0063 s−1 at 5 °C) and measured ratio of coupling efficiencies (Eq. 5) to

| (5) |

yield kH = 0.00075 s−1, kD = 0.000031 s−1, kunc = 0.0060 s−1, CEH = 0.55 (55% coupled to L-allylglycine production) and CED = 0.049 (4.9% coupled). As noted above, decay of the intermediate in the reaction with 4-Cl-Lys is faster than in the reaction with L-Lys (~ 30-fold) and was found by Manley, et al.36 to be more faithfully coupled to the olefin-installing fragmentation. Regardless, the analysis yields a resolved D-KIE (kH/kD) of 24 for production of L-allyglycine, which should be dominated by the primary effect on H/DAT from C4 to the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate or the hypothetical successor with which it reversibly interconverts.

A secondary D-KIE on C5-C6 fragmentation could, theoretically, divert some of the flux in the reaction of the d4-L-Lys to a different product (e.g., 4-hydroxy-L-Lys). This normal secondary effect, which should be ≤ 1.8, would inflate the value – presumed above to originate from a primary D-KIE on C4 HAT – estimated on the basis of L-allylglycine yields. The conservative assumptions of (1) a normal secondary D-KIE as large as 2, causing 2-fold less L-allyglycine to be produced in favor of an alternative product, and (2) a negligible heavy-atom (13C, 15N) primary KIE on L-allylglycine production from the [13C6,15N2]-L-Lys substrate (which, if not negligible, would oppose the effect of the secondary D-KIE) would lead to an estimate of ~ 6 for the impact of (specifically) the primary D-KIE on the ratio of coupling yields, CEH/CED. Using this estimate in place of Eq 5 above would result in a calculated kH/kD of ~ 13. The conclusion that the true primary D-KIE is actually greater than the semi-classical limit of 7–8 makes it more plausible that the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex could indeed be the H•-abstracting complex in the fragmentation of (4-Cl)-L-Lys.

The data are thus consistent with a reaction pathway in which C4 of the substrate donates H• directly to the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex (Scheme 2B, lower black arrow), as recently suggested by Manley, et al.36 From the resultant intermediate state, pathways involving either (1) a (proton-coupled) electron transfer [(PC)ET] from the C4 radical to the Fe2(III/IV) complex followed by a polar fragmentation of the C4 carbocation (blue arrows) or (2) direct radical C5-C6 scission followed by a (PC)ET step from the resultant C6 radical to the Fe2(III/IV) cluster (red arrows) can be envisaged. On the basis of their detection of 4-hydroxylysine in the BesC reaction with L-Lys and claim that solvent is the sole source of the incorporated oxygen in that abortive product, Manley, et al. weighed in favor of a polar pathway via C4 carbocation intermediate. However, they suggested that, rather than directly fragmenting, the carbocation might cyclize to an azacyclobutyl intermediate that would then undergo a polar cycloreversion to generate the final products. Given the anticipated stability of the cyclic species in the reaction with the unchlorinated substrate (L-Lys) and the fact that the polar fragmentation still proceeds without the chlorine substituent (albeit less efficiently), we disfavor this mechanism over a direct fragmentation from either the C4 carbocation or the preceding radical.

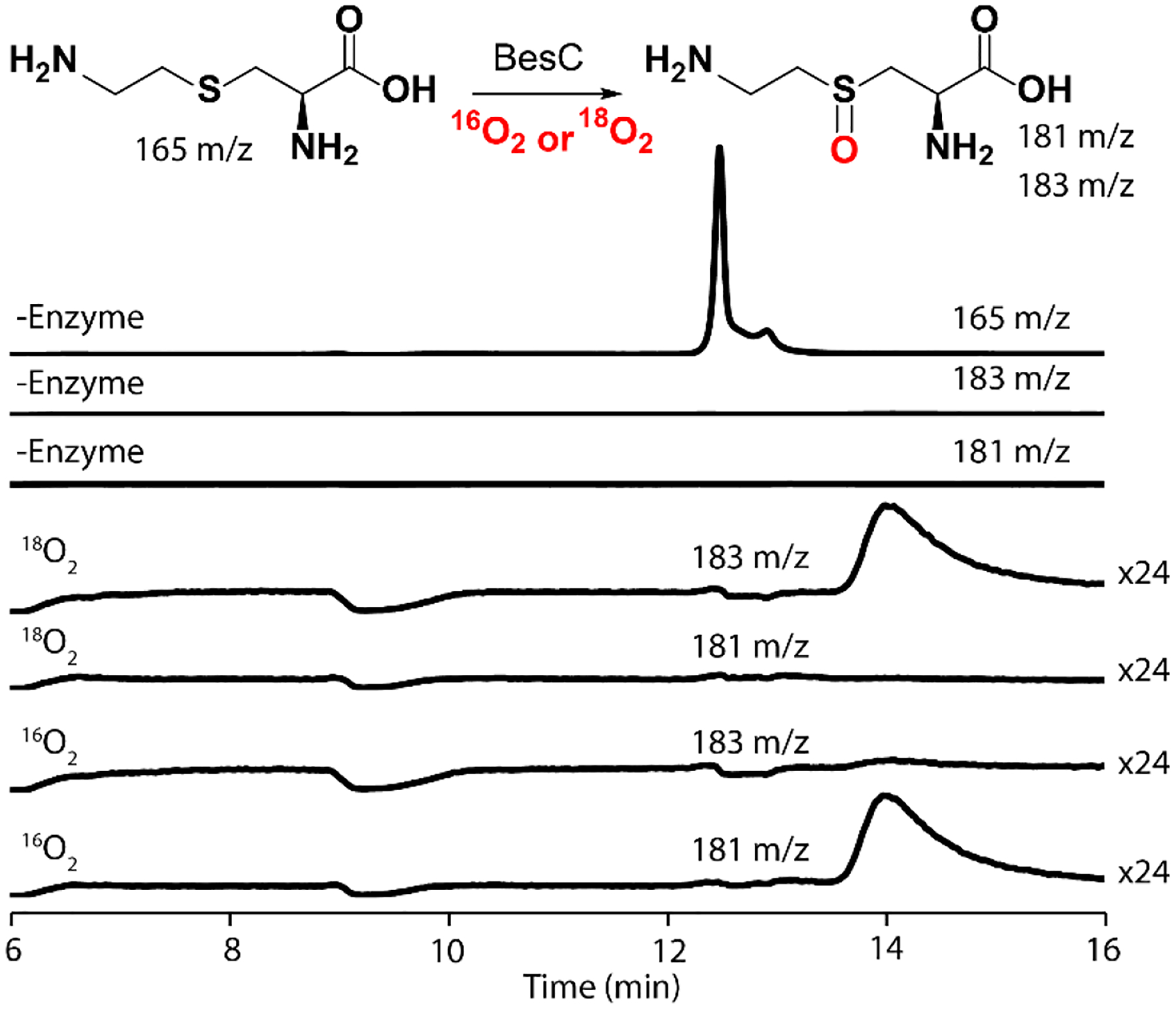

Evidence that 4-thia-L-Lys can undergo OAT to S4.

The conclusion that the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex or its successor cleaves the C4-H bond of the substrate implies that 4-thia-L-Lys should not be fragmented but should rather undergo a different reaction, with the most likely possibility being OAT to the sulfur, as has been shown to occur in other iron enzymes that naturally oxidize sulfur-containing substrates52–54 or are challenged with sulfur-containing substrate analogs.55 We tested by LC-MS for possible fragmentation products from 4-thia-L-Lys (S-methyl-L-cysteine, L-cysteine, L-serine, L-alanine, glycine) but did not detect such products. We readily detected a species with m/z of 181, +16 relative to the M-H+ ion of 4-thia-L-Lys, only in the complete reaction; reactions from which BesC, Fe(II) or O2 was omitted did not produce the associated species (Fig. 5). Use of 18O2 caused the new LCMS peak to shift to m/z = 183, +18 relative to the M-H+ ion of 4-thia-L-Lys, showing that the substrate undergoes oxygenation. Because all feasible carbon hydroxylations in this compound would produce unstable hemiaminal (C2 or C6) or thiohemiacetal (C3 or C5) species that would readily fragment in water, the stable incorporation of an oxygen atom into the detected product necessarily implies that an OAT to a heteroatom has occurred. Although OAT to the ε-amine could, in principle, occur upon derailment of an L-Lys fragmentation pathway initiated by amine radical formation, the presence of sulfur in place of C4 would be expected to promote rather than to impede C5-C6 cleavage by this mechanism, owing to its well-known ability to stabilize an α-carbon-centered radical, in this case on C5. OAT to the sulfur is by far the more likely outcome and is consistent with the observed primary D-KIE on decay of the intermediate.

Figure 5.

LC-MS detection of products in single-turnover reactions of BesC (0.25 mM) after incubation at 22 °C with Fe(II) (0.50 mM) and 4-thia-Lys (0.25 mM) in 100 mM sodium HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol. Single-ion monitoring (SIM) of a control reaction without enzyme shows a large peak for 4-thia-L-Lys at 165 m/z (rear trace) but no peaks at either 183 or 181 m/z. In the presence of natural abundance O2 (16O2), the substrate is mostly consumed, and SIM traces at 181 m/z reveal a new peak with a shift of +16 m/z compared to 4-thia-Lys. Reactions with 18O2 show a mass shift of +18 m/z (at 183 m/z), consistent with the incorporation of an oxygen atom into the product.

Structural determinants of substrate triggering.

We qualitatively explored the determinants of substrate triggering by comparing the capacities of a series of analogs to promote intermediate accumulation at a single fixed concentration (1 mM before mixing) (Fig. S6). BesC is surprisingly promiscuous in this trait: L-lysine analogs modified by stereoinversion of the α-carbon (D-Lys), addition or deletion of a side chain methylene (L-homolysine or L-ornithine), desaturation between existing methylenes (trans-4,5-dehydro-DL-lysine) replacement of the ε-amine by hydroxyl or hydrogen [(6-hydroxy)-L-norleucine (6-OH-L-Nle) or L-norleucine], or mono- or di-methylation of N7 all support accumulation of the peroxide complex to varying extents under these conditions (Fig. S6). By contrast, trimethylation of N7 or replacement of the α-carboxylate or α-amine by hydrogen (1,6-diaminohexane, 6-aminocaproic acid) abolishes intermediate accumulation. The data suggest that, despite cleaving the side chain of (4-chloro)-L-Lys, BesC relies more on the α-carbon substituents as binding determinants, tolerating even a likely cation-to-polar substitution of N7 by O. This observation hints at the possibility that the active site could favor N7 deprotonation, which is expected to be required for either radical or polar fragmentation following HAT from C4 (Scheme. 2B).

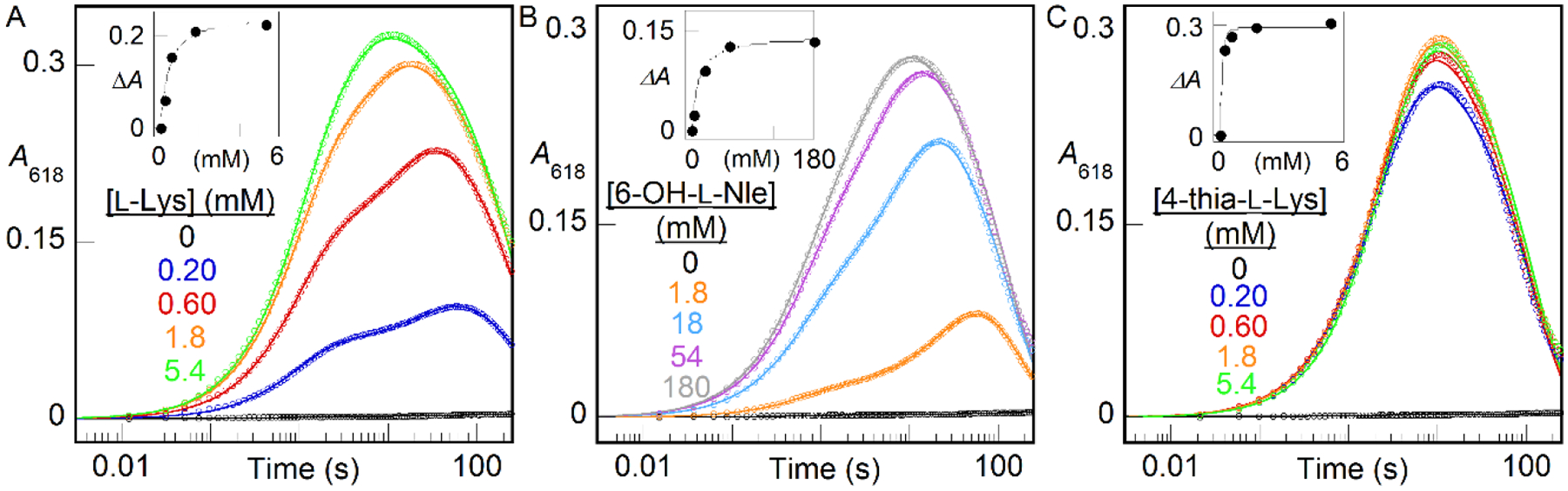

As groundwork for establishing the physical basis of substrate triggering in BesC, we defined the concentration dependencies (Fig. 6) for L-Lys (A), 6-OH-Nle (B), and 4-thia-L-Lys (C) with Fe(II) fixed at 2 molar equivalents relative to BesC. With sub-saturating substrate, the A618 kinetic traces, reflecting formation and decay of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex, exhibit two distinct formation phases. We attribute the faster phase to the capture of O2 by the properly pre-assembled BesC•Fe(II)2•substrate complex and the slower phase to association of a missing component [Fe(II) or substrate] followed by reaction with O2. Fitting the traces to the analytical solution for absorbance in a system of parallel processes with two different, transparent reactants, A and A’, but a common absorbing intermediate, B, and transparent product, C (Scheme S2), which approximates the two-step reaction affording the slower formation phase as a single step to simplify analysis, allows the amplitudes of the fast phase and thus the relative concentrations of BesC•Fe(II)2•substrate complex in the reactant solutions to be extracted. Regression fits of plots of this quantity versus the concentration of the substrate yield approximate dissociation constants (KD) of 0.3 ± 0.1 mM for L-Lys, 10 ± 1 mM for 6-OH-L-Nle, and < 30 μM for 4-thia-L-Lys (Fig. 6 insets). The traces from the 4-thia-L-Lys reaction are not as clearly biphasic, and the effect of the analog saturates at just slightly greater than one molar equivalent, implying that the association is tight and this analog is particularly effective at driving assembly of the O2-reactive complex (Fig. 6C). These results are consistent with a binding selectivity for a Lys analog with a larger, more polarizable substituent at the 4 position, as in 4-Cl-L-Lys.

Figure 6.

A618-versus-time traces demonstrating the effect of substrates on triggering the reaction of Fe(II)•BesC complex with O2 at 5°C. A reactant solution of BesC (0.20 mM), Fe(II) (0.40 mM, 2 molar equiv), and (A) L-Lys, (B) 6-OH-L-Nle, or (C) 4-thia-L-Lys at the concentrations indicated by the color-coded legends was mixed with an equal volume of O2-saturated buffer. The insets plot the amplitude of the fast phase (ΔA) as a function of the substrate concentration. The solid lines are fits of the quadratic (A and C) or hyperbolic (C) equation for binding to these data.

Physical basis of substrate triggering: synergy of substrate and Fe(II) binding.

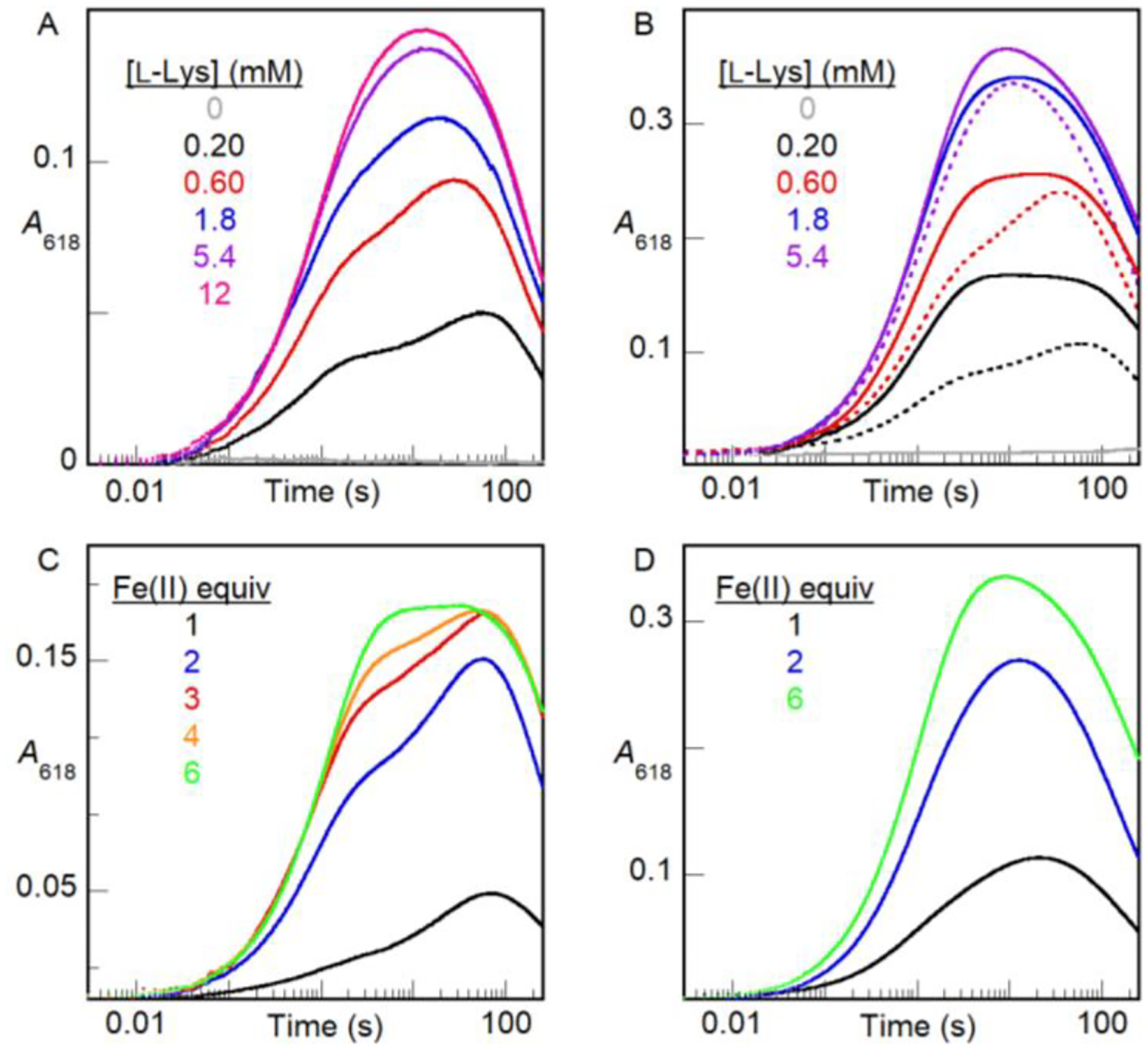

Prior studies and the structure of apo BesC presented above (Fig. 1) imply that the HDO scaffold generally has only one pre-configured Fe(II) site (site 1) along with a second site (site 2) afforded by a conditionally stable (i.e., intrinsically disordered) helix.3–4,7–8,56 The most recent work showed that site 2 in the HDO domain of SznF can be properly configured by a conformational change driven by Fe(II) binding.7,56 We therefore considered that substrate triggering in BesC could reflect synergy in substrate and Fe(II) binding arising from a substrate-driven configuration of the dynamic α3 that provides the ligands for site 2. As a first assessment, we titrated the triggering effect of L-Lys with 1.0 (Fig. 7A), 2.0 (Fig. 6A) or 6.0 (Fig. 7B) molar equivalents of Fe(II) in the BesC solution. All three plots show the same qualitative behavior, including a hyperbolically increasing fast formation phase with increasing [L-Lys]. With 1.0 equiv Fe(II), the transient feature saturates at less than 50% of its maximum possible amplitude with excess Fe(II) (Fig 7B), consistent with the fact that this quantity of Fe(II) is only half that needed to fill both sites of the cofactor. Linkage between Fe(II) and L-Lys binding is evident by comparing traces from reactions with 2 and 6 equiv of Fe(II) at sub-saturating concentrations of L-Lys (e.g., 0.20 mM and 0.60 mM): the greater Fe(II) concentration yields considerably greater amplitude in the fast phase (Fig. 7B, solid traces) than the lesser [Fe(II)] (dotted traces), a difference that is largely overcome at the highest [L-Lys]. Conversely, the effect of increasing [Fe(II)] on the fast-phase amplitude is much more pronounced with 0.20 mM L-Lys (Fig. 7C) than with 5.4 mM L-Lys (Fig. 7D). These effects of varied [L-Lys] at fixed [Fe(II)] and varied [Fe(II)] at fixed L-Lys reflect, generally, synergistic metal and substrate binding.

Figure 7.

A618-versus-time traces from stopped-flow absorption experiments in which an anoxic solution of BesC (0.20 mM), Fe(II) and L-Lys was mixed at 5 °C with an equal volume of O2-saturated buffer. In titrations of L-Lys, BesC was incubated with (A) 0.20 mM (1 molar equiv) or (B) 1.2 mM (6 molar equiv) of Fe(II). The dotted traces in panel B are from matching experiments (from Figure 6A) with 0.40 mM (2 molar equiv) Fe(II) and are overlaid to illustrate the impact of varying [Fe(II)]. In titrations of Fe(II) (0.20–1.2 mM), BesC was incubated with (C) 0.20 mM (1 molar equiv) or (D) 5.4 mM (27 molar equiv) of L-Lys.

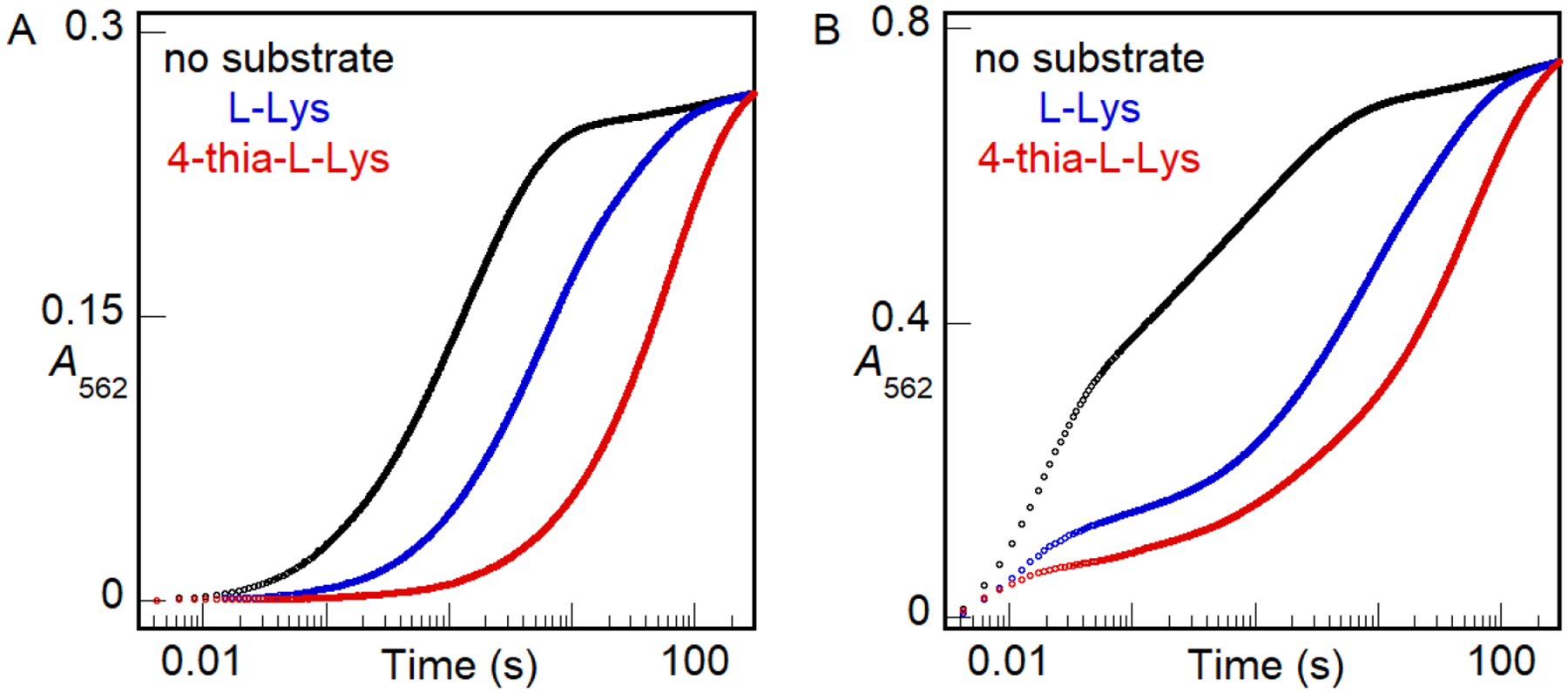

We obtained more direct evidence of this linkage by use of a kinetic assay based on the Fe(II) indicator, ferrozine, which forms the purple Fe(II)•ferrozine3 complex with λmax = 562 nm, and ε562 = 27,900 M−1cm−1. Fe(II)aq is complexed rapidly (~ 50 s−1 under the conditions of the assay), whereas Fe(II) bound by BesC must dissociate before it can be detected.57–58 Mixing an anoxic solution containing BesC and 0.8–1.0 equiv Fe(II) with an anoxic solution containing excess ferrozine leads to development of absorbance at 562 nm (A562) with a half-life (t1/2) of 0.5–1 s (longer at higher [BesC], owing to rebinding by the protein in competition with ferrozine capture58). No discernible fast phase of development is seen, implying that BesC can bind one Fe(II) ion tightly in the absence of a substrate (Fig. 8A, black trace, and Fig. S7). With 2.0 equiv Fe(II), phases with approximate t1/2 values of ~ 0.02 s, arising from Fe(II)aq, and ~ 1 s, arising from Fe(II) bound by BesC, have approximately equal amplitudes, suggesting that BesC binds only one equiv Fe(II) under these conditions (Fig. 8B, black trace). Indeed, inclusion of three times as much Fe(II) (6 equiv) increases the amplitude only of the fast phase arising from chelation of Fe(II)aq (Fig. S7); the amplitude of the slow phase from release/chelation of Fe(II) bound in BesC remains essentially constant, establishing that binding of a second Fe(II) ion is, at best, much weaker than binding of the first Fe(II) ion. Inclusion of 12 mM L-Lys (Fig. 8A, blue) or 4-thia-L-Lys (red) in the BesC solution with 0.8 equiv Fe(II) slows dissociation of the complex, extending the half-life of A562 development to ~ 6 s or ~ 40 s, respectively. This slowing of ferrozine chelation reflects some combination of a diminished rate of dissociation from, and increased rate of binding by, BesC in the presence of bound substrate. Slower dissociation would, obviously, slow colorimetric detection, and faster association could cause the Fe(II) released from BesC to partition more frequently toward rebinding in competition with the irreversible capture in the low-spin Fe(II)•ferrozine3 complex. Again, the greater affinity of the C4 → S analog is evident, in this case by its greater delay of Fe(II) release/detection. More strikingly, the presence of this high concentration of either substrate in the BesC reactant solution containing 2.0 equiv Fe(II) drastically suppresses the fast phase of complexation (Fig. 8B, blue and red), almost completely abolishing it for the case of the tighter-binding 4-thia-L-Lys (red). The amplitude of the slow phase associated with bound Fe(II) increases to account for the loss from the fast phase. These results establish that substrate binding allows BesC to complete assembly of its functional cofactor by binding the second Fe(II) ion. Given the crystallographic observations, the most likely explanation for this phenomenon is that the substrate induces ordering of α3 to properly configure an otherwise incompetent site 2. To the best of our knowledge, this mechanism of substrate triggering has not previously been observed or proposed for an O2-activating dinuclear metalloenzyme. The apparently obligatory binding order of (1) Fe(II) in site 1, (2) L-Lys substrate, (3) Fe(II) in site 2, and finally (4) O2, along with the subsequent spontaneous disintegration of the diiron(III) product cluster, underscore that the function of iron in BesC – and possibly in all HDOs – is more as a substrate than as a stably bound cofactor. We note that this conclusion impacts interpretations of Mössbauer-spectroscopic data in the study by Manley, et al., in which the authors presumed to have formed a dinuclear iron complex of BesC in the absence of substrate.36

Figure 8.

A562-versus-time traces monitoring chelation of Fe(II) by ferrozine, rapidly when free in solution or more slowly after its rate-limiting dissociation from BesC. An anoxic solution of 0.16 mM apo BesC was loaded with either (A) 0.13 mM (0.8 molar equiv) or (B) 0.32 mM (2 molar equiv) Fe(II) in the absence substrate (black) or in the presence of 12 mM L-Lys (blue) or 4-thia-L-Lys (red). This solution was subsequently mixed with an equal volume of an anoxic solution of 4 mM ferrozine. The absorbance of the purple Fe(II)•ferrozine3 complex at 562 nm (A562) was monitored as a function of reaction time. The traces shown here are representative of at least 2 trials for each condition. Results of experiments with greater Fe(II):BesC ratios in the absence of substrate are provided in Fig. S7.

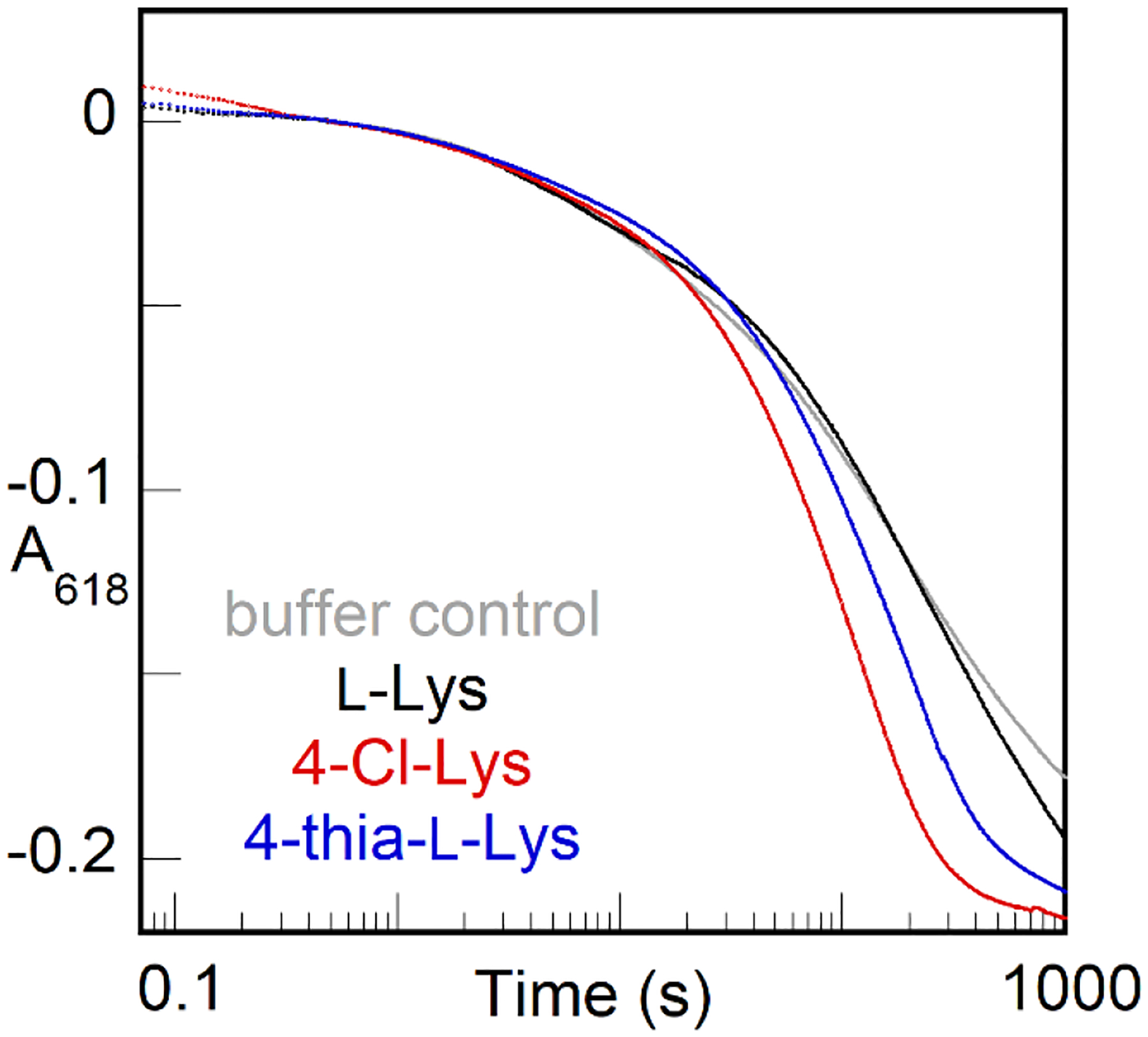

Substrate dissociation from, and binding to, the μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate.

Given the proposed mechanism by which L-Lys triggers intermediate formation (properly configuring an otherwise disordered Fe site 2), its relatively modest affinity, and the sluggishness of its reaction with the intermediate (or its successor), we wondered if the addition of O2 to the cofactor effectively traps the substrate on the enzyme or, alternatively, if it can dissociate after driving configuration of the second iron site and formation of the intermediate. Protection of reactive intermediates is a well-known phenomenon in enzymology, and conformational changes that effectively seal the active site are often seen or invoked. For the case of iron-oxygen adducts, there is ample evidence that protonation occurs in forward conversion to more reactive states or as part of proton-coupled reduction steps (including HAT), and so sequestration from solvent and sources of protons would seem necessary to contain a reactive complex for the tens of minutes seen in the case of the μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex formed in BesC with L-Lys. Conversely, dissociation/binding of substrate from/to such a state would seem incompatible with prolonged stability. Surprisingly, L-Lys does indeed dissociate from the long-lived intermediate to allow for binding and reaction of another substrate. We demonstrated this behavior by sequential-mix stopped-flow experiments (Fig. 9), in which the intermediate was allowed to accumulate maximally following an initial mix of BesC•Fe(II)2•L-Lys complex with O2-containing buffer and this solution was then mixed with an excess of one of the more reactive substrates, 4-thia-L-Lys (blue) or 4-Cl-Lys (red). Both substrates caused concentration-dependent (Fig. S8) acceleration of decay of the intermediate relative to controls in which the pre-formed intermediate was mixed with buffer or additional L-Lys. The fact that neither substrate reacted with the intermediate as rapidly as it does in a single-mix experiment, in which it triggers intermediate formation itself, suggests that L-Lys dissociation is slower than the chemical reactions of the two more reactive substrates with the intermediate. Nevertheless, the fact that substrate can dissociate and re-bind at all in the intermediate state again underscores the dynamic character of the HDO scaffold and its potential to be leveraged in biocatalysis applications.

Figure 9.

A618-versus-time traces from a sequential-mix stopped-flow experiment showing accelerated of decay of the BesC μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediate when mixed with a more reactive substrate after triggering of formation by L-Lys. An anoxic solution containing BesC (0.40 mM), Fe(II) (0.80 mM), and L-Lys (2.7 mM) was mixed with an equal volume of O2 saturated buffer at 5 °C. After aging for 30 s, this solution was mixed with an equal volume of an anoxic solution of buffer (gray), excess L-Lys (10 mM, black), 4-Cl-Lys (6.8 mM, red), or 4-thia-L-Lys (6.8 mM, blue).

CONCLUSIONS

The members of the emerging HDO family studied to date (i) all bind iron only weakly in one of two sites, (ii) form accumulating μ-peroxodiiron(III) intermediates, and (iii) allow or promote disintegration of the diiron(III) cofactor product following intermediate decay. Structural studies have shown that core helix α3, which provides three cofactor ligands to iron 2, is generally dynamic and responsible for the weak binding of Fe(II) at this site, the need for a conformational change prior to Fe(II) binding, and the instability of the oxidized cofactor. BesC shares these emerging, unifying traits. Its promiscuous triggering by a soluble substrate and its variously modified derivatives enabled demonstration that the novel mechanism of triggering involves substrate-promoted configuration of an initially disordered iron site 2 to allow assembly of the active BesC•Fe(II)2•substrate and capture of O2. The resultant μ-peroxodiiron(III) complex is relatively long-lived despite the ability of the triggering substrate to dissociate and reassociate in the intermediate state, and reactivity trends as well as a primary D-KIE on decay of the intermediate of ~ 13–24 in the reaction with L-Lys show that the intermediate, or a successor with which it interconverts, initiates the complex fragmentation by HAT from C4. As the most likely successor to the observed intermediate would be a diiron(IV) complex with cleaved O-O bond, the results presented herein would provide either (1) just the second example (of which we are aware) of experimental evidence for HAT directly to a peroxodiiron(III) intermediate or (2) the first example (of which we are aware) of reversible O-O-bond cleavage in such a complex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE-1610676 to C.K., J.M.B., and A.K.B. and CHE-1710588 to M.C.Y.C) and the National Institutes of Health (GM138580 to J.M.B., GM119707 to A.K.B., GM127079 to C.K.). J.W.S acknowledges support of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institute of Health (F32GM136156). M.E.N. acknowledges the support of a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

S. cattleya BesC F8JJ25 (Uniprot ID)

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supplementary methods; schemes illustrating kinetic masking of C–H-cleaving intermediate and kinetic model for analysis of SF-abs data; figures showing electron density map for helix α3 of apo BesC, detection of d3-allylglycine by LC-MS, reference Mössbauer spectrum of BesC peroxodiiron(III) complex, comparison of raw and theoretical Mössbauer spectra, overlay of all RFQ-Mössbauer spectra showing time dependence of Fe-containing species, substrate diversity and triggering of the BesC intermediate, ferrozine competitive chelation by SF-Abs, and concentration dependence of substrate binding by SF-Abs; tables giving X-ray data collection statistics, cloning primers, trace metals recipe, and Mössbauer parameters.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marchand JA; Neugebauer ME; Ing MC; Lin CI; Pelton JG; Chang MCY, Discovery of a pathway for terminal-alkyne amino acid biosynthesis. Nature 2019, 567 (7748), 420–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajakovich LJ; Zhang B; McBride MJ; Boal AK; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., Comprehensive Natural Products III. Elsevier: Oxford, 2020; p 215–250. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng TL; Rohac R; Mitchell AJ; Boal AK; Balskus EP, An N-nitrosating metalloenzyme constructs the pharmacophore of streptozotocin. Nature 2019, 566 (7742), 94–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang B; Rajakovich LJ; Van Cura D; Blaesi EJ; Mitchell AJ; Tysoe CR; Zhu X; Streit BR; Rui Z; Zhang W; Boal AK; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., Substrate-triggered formation of a peroxo-Fe2(III/III) intermediate during fatty acid decarboxylation by UndA. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (37), 14510–14514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manley OM; Fan R; Guo Y; Makris TM, Oxidative decarboxylase UndA utilizes a dinuclear iron cofactor. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (22), 8684–8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBride M,J; Sil D; Ng TL; Crooke AM; Kenney GE; Tysoe CR; Zhang B; Balskus EP; Boal AK; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., A peroxodiiron(III/III) intermediate mediating both N-hydroxylation steps in biosynthesis of the N-nitrosourea pharmacophore of streptozotocin by SznF. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142, 11818–11828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride MJ; Pope SR; Hu K; Okafor CD; Balskus EP; Bollinger JM Jr.; Boal AK, Structure and assembly of the diiron cofactor in the heme-oxygenase-like domain of the N-nitrosourea-producing enzyme SznF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride MJ; Boal AK, SznF, a metalloenzyme employed in the biosynthesis of streptozotocin. EIBC 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasniewski AJ; Que L Jr., Dioxygen activation by nonheme diiron enzymes: diverse dioxygen adducts, high-valent intermediates, and related model complexes. Chem Rev 2018, 118 (5), 2554–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray LJ; Naik SG; Ortillo DO; García-Serres R; Lee JK; Huynh BH; Lippard SJ, Characterization of the arene-oxidizing intermediate in ToMOH as a diiron(III) species. J Am Chem Soc 2007, 129 (46), 14500–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korboukh VK; Li N; Barr EW; Bollinger JM Jr.; Krebs C, A long-lived, substrate-hydroxylating peroxodiiron(III/III) intermediate in the amine oxygenase, AurF, from Streptomyces thioluteus. J Am Chem Soc 2009, 131 (38), 13608–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jasniewski AJ; Komor AJ; Lipscomb JD; Que L Jr., Unprecedented (μ-1,1-peroxo)diferric structure for the ambiphilic orange peroxo intermediate of the nonheme N-oxygenase CmlI. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139 (30), 10472–10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SK; Fox BG; Froland WA; Lipscomb JD; Münck E, A transient intermediate of the methane monooxygenase catalytic cycle containing an FeIVFeIV cluster. J Am Chem Soc 1993, 115 (14), 6450–6451. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SK; Nesheim JC; Lipscomb JD, Transient intermediates of the methane monooxygenase catalytic cycle. J Biol Chem 1993, 268 (29), 21569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nesheim JC; Lipscomb JD, Large kinetic isotope effects in methane oxidation catalyzed by methane monooxygenase: evidence for C-H bond cleavage in a reaction cycle intermediate. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (31), 10240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brazeau BJ; Lipscomb JD, Kinetics and activation thermodynamics of methane monooxygenase compound Q formation and reaction with substrates. Biochemistry 2000, 39 (44), 13503–13515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollinger JM Jr.; Edmondson DE; Huynh BH; Filley J; Norton; Stubbe J, Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical-dinuclear iron cluster cofactor of ribonucleotide reductase. Science 1991, 253 (5017), 292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bollinger JM Jr.; Tong WH; Ravi N; Huynh BH; Edmonson DE; Stubbe J, Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical-diiron(III) cofactor of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase. 2. Kinetics of the excess Fe2+ reaction by optical, EPR, and Mössbauer spectroscopies. J Am Chem Soc 1994, 116 (18), 8015–8023. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acheson JF; Bailey LJ; Brunold TC; Fox BG, In-crystal reaction cycle of a toluene-bound diiron hydroxylase. Nature 2017, 544 (7649), 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rardin RL; Tolman WB; Lippard SJ, Monodentate carboxylate complexes and the carboxylate shift: Implications for polymetalloprotein structure and function. New J. Chem 1991, 15, 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SJ; McCormick MS; Lippard SJ; Cho U-S, Control of substrate access to the active site in methane monooxygenase. Nature 2013, 494 (7437), 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gherman BF; Baik M-H; Lippard SJ; Friesner RA, Dioxygen activation in methane monooxygenase: A theoretical study. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126 (9), 2978–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey LJ; McCoy JG; Phillips GN Jr.; Fox BG, Structural consequences of effector protein complex formation in a diiron hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105 (49), 19194–19198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jasniewski AJ; Knoot CJ; Lipscomb JD; Que L Jr., A carboxylate shift regulates dioxygen activation by the diiron nonheme β-hydroxylase CmlA upon binding of a substrate-loaded nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Biochemistry 2016, 55 (41), 5818–5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N; Korboukh VK; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., Four-electron oxidation of p-hydroxylaminobenzoate to p-nitrobenzoate by a peroxodiferric complex in AurF from Streptomyces thioluteus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107 (36), 15722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkin CL; Thelander L; Reichard P; Lang G, Iron and free radical in ribonucleotide reductase. Exchange of iron and Mössbauer spectroscopy of the protein B2 subunit of the Escherichia coli enzyme. J. Biol. Chem 1973, 248 (10), 7464–7472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodland MP; Patil DS; Cammack R; Dalton H, ESR studies of protein A of the soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). Protein Struct Mol Enzymol Biochim Biophys Acta 1986, 873 (2), 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox BG; Shanklin J; Ai J; Loehr TM; Sanders-Loehr J, Resonance Raman evidence for an Fe-O-Fe center in stearoyl-ACP desaturase. Primary sequence identity with other diiron-oxo proteins. Biochemistry 1994, 33 (43), 12776–12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rui Z; Li X; Zhu X; Liu J; Domigan B; Barr I; Cate JH; Zhang W, Microbial biosynthesis of medium-chain 1-alkenes by a nonheme iron oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111 (51), 18237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He HY; Henderson AC; Du YL; Ryan KS, Two-enzyme pathway links L-arginine to nitric oxide in N-nitroso biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141 (9), 4026–4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordlund P; Uhlin U; Westergren C; Joelsen T; Sjöberg B-M; Eklund H, New crystal forms of the small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase from Escherichia coli. FEBS Letters 1989, 258 (2), 251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Åberg A; Nordlund P; Eklund H, Unusual clustering of carboxyl side chains in the core of iron-free ribonucleotide reductase. Nature 1993, 361 (6409), 276–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sazinsky MH; Merkx M; Cadieux E; Tang S; Lippard SJ, Preparation and x-ray structures of metal-free, dicobalt and dimanganese forms of soluble methane monooxygenase hydroxylase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). Biochemistry 2004, 43 (51), 16263–16276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moche M; Shanklin J; Ghoshal A; Lindqvist Y, Azide and acetate complexes plus two iron-depleted crystal structures of the di-iron enzyme Δ9 stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase: Implications for oxygen activation and catalytic intermediates J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (27), 25072–25080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedges JB; Ryan KS, In vitro reconstitution of the biosynthetic pathway to the nitroimidazole antibiotic azomycin. Angew Chem Int Ed 2019, 58 (34), 11647–11651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manley OM; Tang H; Xue S; Guo Y; Chang W.-c.; Makris TM, BesC Initiates C–C Cleavage through a Substrate-Triggered and Reactive Diferric-Peroxo Intermediate. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143 (50), 21416–21424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller JH, Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trace metals stock solution. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols 2006, (1). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gasteiger E; Hoogland C; Gattiker A; Duvaud S; W. MR; Appel RD; Bairoch A, Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. Walker JM, Ed. Humana Press: The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravi N; Bollinger JM Jr.; Huynh BH; Stubbe J; Edmondson DE, Mechanism of assembly of the tyrosyl radical-diiron(III) cofactor of E. coli ribonucleotide reductase: 1. Mössbauer characterization of the diferric radical precursor. J Am Chem Soc 1994, 116 (18), 8007–8014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauvais LG; Lippard SJ, Reactions of the peroxo intermediate of soluble methane monooxygenase hydroxylase with ethers. J Am Chem Soc 2005, 127 (20), 7370–7378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldwin J; Krebs C; Saleh L; Stelling M; Huynh BH; Bollinger JM Jr.; Riggs-Gelasco P,J, Structural characterization of the peroxodiiron(III) intermediate generated during oxygen activation by the W48A/D84E variant of ribonucleotide reductase protein R2 from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 2003, 42 (45), 13269–13279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang W; Saleh L; Barr EW; Xie J; Gardner MM; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., Branched activation- and catalysis-specific pathways for electron relay to the manganese/iron cofactor in ribonucleotide reductase from Chlamydia trachomatis. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (33), 8477–8484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vu VV; Emerson JP; Martinho M; Kim YS; Münck E; Park MH; Que L Jr, Human deoxyhypusine hydroxylase, an enzyme involved in regulating cell growth, activates O2 with a nonheme diiron center. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106 (35), 14814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim K; Lippard SJ, Structure and Mössbauer spectrum of a (μ−1,2-Peroxo)bis(μ-carboxylato)diiron(III) model for the peroxo intermediate in the methane monooxygenase hydroxylase reaction cycle. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118 (20), 4914–4915. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chalupsky J; Rokob TA; Kurashige Y; Yanai T; Solomon EI; Rulísek L; Srnec M, Reactivity of the binuclear non-heme iron active site of delta (Δ9) desaturase studied by large-scale multireference ab initio calculations. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136 (45), 15977–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price JC; Barr EW; Glass TE; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr., Evidence for hydrogen abstraction from C1 of taurine by the high-spin Fe(IV) intermediate detected during oxygen activation by taurine:α-ketoglutarate dioxygenase (TauD). J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125 (43), 13008–13009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stapon A; Li R; Townsend CA, Carbapenem biosynthesis: confirmation of stereochemical assignments and the role of CarC in the ring stereoinversion process from L-proline. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125 (28), 8486–8493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffart LM; Barr EW; Guyer RB; Bollinger JM Jr.; Krebs C, Direct spectroscopic detection of a C-H-cleaving high-spin Fe(IV) complex in a prolyl-4-hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103 (40), 14738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunham NP; Mitchell AJ; Del Río Pantoja JM; Krebs C; Bollinger JM Jr.; Boal AK, α-Amine desaturation of D-arginine by the iron(II)- and 2-(oxo)glutarate-dependent L-arginine 3-hydroxylase, VioC. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (46), 6479–6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bollinger JM Jr.; Krebs C, Stalking intermediates in oxygen activation by iron enzymes: motivation and method. J Inorg Biochem 2006, 100 (4), 586–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sörbo B; Ewetz L, The enzymatic oxidation of cysteine to cysteinesulfinate in rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1965, 18 (3), 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCoy JG; Bailey LJ; Bitto E; Bingman CA; Aceti DJ; Fox BG; Phillips GN Jr., Structure and mechanism of mouse cysteine dioxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103 (9), 3084–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dominy JE Jr.; Simmons CR; Hirschberger LL; Hwang J; Coloso RM; Stipanuk MH, Discovery and characterization of a second mammalian thiol dioxygenase, cysteamine dioxygenase J Biol Chem 2007, 282 (35), 25189–25198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J.-b.; Huang Q; Peng W; Wu P; Yu D; Chen B; Wang B; Reetz MT, P450-BM3-catalyzed sulfoxidation versus hydroxylation: a common or two different catalytically active species? J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142 (4), 2068–2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McBride MJ; Pope SR; Hu K; Slater JW; Okafor CD; Balskus EP; Bollinger JM Jr.; Boal AK, Structure and assembly of the diiron cofactor in the heme-oxygenase-like domain of the N-nitrosourea-producing enzyme SznF. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.07.29.227702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stookey LL, Ferrozine-a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal Chem 1970, 42 (7), 779–781. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Umback NJ; Norton JR, Indirect determination of the rate of iron uptake into the apoprotein of the ribonucleotide reductase of E. coli. Biochemistry 2002, 41 (12), 3984–3990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.