Abstract

The development of COVID-19 vaccines was a landmark in the current efforts to contain the global pandemic caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2. Consequently, vaccine rollout and inoculation campaigns continue to progress steadily across the globe. However, “skewed” rollout, or the inequitable or delayed access to the vaccines encountered particularly by low-income countries in Africa, remains a source of great concern. This may negatively affect the continent and could lead to increased transmission, travel restrictions, further economic disruptions, and increased morbidity and mortality. Ultimately, these negative consequences could directly or indirectly hamper global efforts to defeat the pandemic. Access to COVID-19 vaccines is a global priority and provides a source of hope to bring the pandemic under control. High-income nations, national governments, donor agencies, and other relevant stakeholders must support the World Health Organization's COVAX initiative to ensure fair, rapid and equitable distribution of the vaccines to countries, irrespective of income level. This effort will rapidly bring the pandemic under control and impact the recovery of the global economy. Low-income nations in Africa must significantly invest in research, health care, vaccines, and drug development and must remain proactive in preparing against future pandemics. This review examines the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines with a focus on Africa.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccine, vaccination, pandemic, access, low-income countries, COVAX

Within an unprecedented timeline, vaccine manufacturers in resource-advanced nations, including the United Kingdom and United States, successfully developed the highly anticipated vaccines against the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Indeed, it was a laudable milestone in public health intervention aimed at combatting the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1,2 The efficacy of the vaccines conforms with the World Health Organization (WHO) benchmark for target product profile for COVID-19 vaccines.3 Acquisition of emergency use authorization by regulatory authorities fast-tracked rollout and vaccination campaigns worldwide. The COVID-19 vaccination is expected to confer some level of protection in humans against the virus and ultimately reduce the severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.4

Notwithstanding the present global vaccination, many nations continue to record upsurges in cases, notably the United States, India, Brazil, Russia, and the United Kingdom.5 Similarly, mortality continues to rise, especially in the worst-hit countries, such as the United States, with the death toll surpassing half a million. The global cases and mortality figure as of March 21, 2021, reached 117.6 million and 2.6 million, respectively.5 The emergence and rapid spread of newer variants of the virus, such as in the United Kingdom (B.1.1.7) and South Africa (B.1.351), has warranted travel restrictions due to their highly contagious nature.6,7 Notwithstanding these mutated strains, the development of COVID-19 vaccines has renewed optimism for an end to the unprecedented health crisis of recent times.

COVID-19 Vaccines in Use

Since the emergence of COVID-19 and characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence in January 2020,8 scientific research continues to gain momentum globally in attempts to unravel more information about the pathogen and to develop prophylactic vaccines and therapeutic interventions to combat the pandemic. Vaccines were eventually and historically developed through concerted efforts and global collaboration.9 For instance, the multinational U.S.–Germany Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the University of Oxford-AstraZeneca in the United Kingdom received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). China, where the SARS-CoV-2 originated, successfully developed its vaccine with efficacy reaching 50%, as indicated in Table 1. The FDA stipulated a benchmark of at least 50% efficacy for vaccines against COVID-19.10 Russia was the first nation to have declared and approved its vaccine, tagged Sputnik V.9 India, a vaccine powerhouse and producer of 60% of the world vaccines, expectedly authorized two versions of COVID-19 vaccines, Covishield and Covaxin. The former is a licensed local version of the United Kingdom's Oxford-AstraZeneca, while the latter was developed by an indigenous company, Bharat Biotech.11 Early deals for procurement of the vaccines may have been signed up for by high-income nations, and vaccination campaigns kicked off historically across the globe, as highlighted in Figure 1(A) and (B). Due to the global need for the COVID-19 vaccines, high-income countries must not monopolize supply13 to the detriment of low-income countries, which could scuttle global efforts to contain the pandemic. High economies probably had invested significantly in COVID-19 research and clinical trials leading to the vaccines’ development. Furthermore, these nations probably had signed pre-orders for the vaccines from the manufacturers long before the final outcomes of the trials, thus justifying the rollout priority. Nevertheless, wealthy nations have a social obligation to consider the plight of low-income countries vis-à-vis economic status—hence the need to show support to low-income nations by donation of surplus doses or any other assistance on humanitarian grounds. These vaccines provide significant relief to frontline health care workers, essential service providers, the elderly, and those with pre-existing co-morbidities who are the most vulnerable populations. Several other vaccine candidates are currently in different phases of development and tracking.2 Should these vaccines be authorized for use and made available soon, they would speedily contain the pandemic. With the exception of the Janssen vaccine, these vaccines require two doses at several weeks’ intervals. So far, few countries have administered the complete dose regimen to certain percentages of their population, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Six Leading COVID-19 Vaccines Currently in use Across the Globe.

| Vaccine | Manufacturer | Vaccine type | Storage temperature | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | Pfizer (US)- BioNTech (Germany) | Messenger RNA | −70 °C | 95% |

| mRNA1273 | ModernaTX Inc. (US) | Messenger RNA | 2–8 °C | 95% |

| AZD 1222 | University of Oxford-AstraZeneca (UK) | Non-replicating Viral vector | 2–8 °C | 70% |

| Sputnik-V | Gamaleya Research Institute (Russia) | Non-replicating Viral vector | −18 °C | 92% |

| CoronaVac | Sinovac Biotech (China) | Inactivated virus | 2–8 °C | 50% |

| Johnson & Johnson* | Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies (Belgium/US) | Non-replicating Viral vector | 2–8 °C | 66% |

requires single dosing.

Sources: Bloomberg COVID-19 vaccine tracker, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines.html.

Milken Institute COVID-19 vaccine tracker, https://airtable.com/shrSAi6t5WFwqo3GM/tblEzPQS5fnc0FHYR/viwDBH7b6FjmIBX5x?blocks=bipZFzhJ7wHPv7x9z.

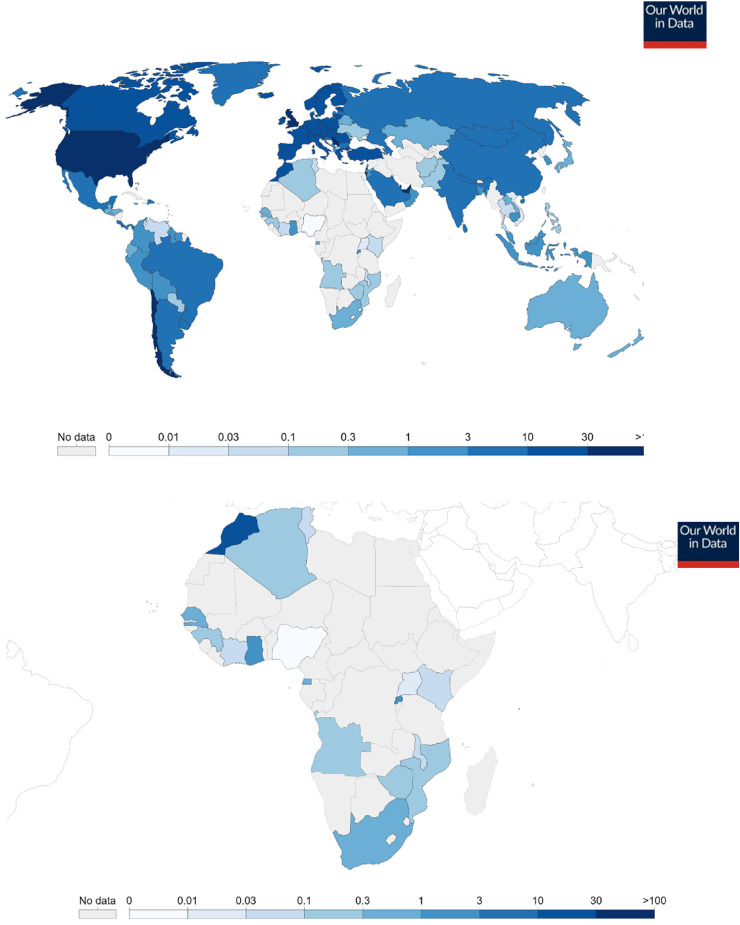

Figure 1.

(A) Global Cumulative COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people as of March 20, 2021.12 Data counted as a single dose and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime (e.g., people receive multiple doses). Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations. (Data from the source is regularly updated.). (B) Africa's Cumulative COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people as of March 20, 2021.12 Data counted as a single dose and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on the specific dose regime (eg, people receive multiple doses). Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

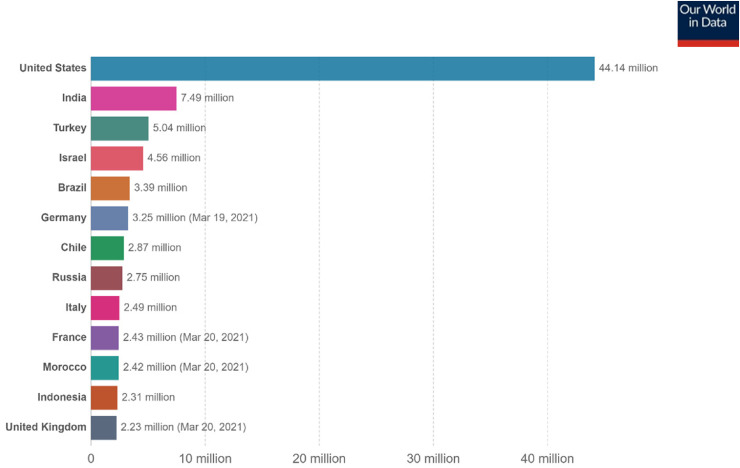

Figure 2.

Number of people fully vaccinated against COVID-19 as of March 21, 2021.12 Total number of people who received all doses prescribed by the vaccination protocol. This data is only available for countries that report breakdown of doses administered at first and repeat vaccination. Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

Delayed Access by Low-Income Nations

As many countries continue to access COVID-19 vaccines and execute inoculation programs, poorer countries continue to wait longer than necessary before accessing the vaccines. This situation is worrisome and could negatively affect millions of people in these countries. The long delay could increase the rate of transmission. Although Africa has recorded fewer cases and deaths compared to other continents, the disruption caused by the pandemic is huge. Undoubtedly, there exist marked distinctions between wealthy nations and developing and least developed nations in their capacities to procure COVID-19 vaccines and inoculate their populations. For low-income countries, procuring the in-demand COVID-19 vaccines requires substantial financial resources. However, the disruption caused by the pandemic and expedited efforts to save lives and livelihoods provide justification to source funds for procurement. These reasons perhaps informed the WHO's decision on its COVAX Facility initiative. This initiative promotes fair and equitable access to safe, effective vaccines after authorization and WHO emergency use listing, to all its over 190 participating economies irrespective of the income level. The supply's initial phase targets vaccination for 20% of the population, which is deemed adequate to minimize target groups in COVAX countries.14 This initiative is a partnership co-led by WHO, Gavi (a vaccine funding agency for low-income nations), and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation (CEPI). Agreements with five vaccine manufacturers have been struck, and distribution of vaccines from the COVAX portfolio was kickstarted in February 2021.14

The current global rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine has flaunted the gap between the world's rich and poor countries. The cost of producing and distributing COVID-19 vaccines to low-income and lower-middle-income countries, with a population of about 3.7 billion, is estimated at US$25 billion. According to Oxfam International, this amount is less than the top 10 giant pharmaceutical companies’ revenue in four months of 2019 alone.15 Inequitable access and policies related to the COVID-19 vaccines could plunge the world into a “catastrophic moral failure.”16 This situation can further increase mortality, extend travel restrictions, cripple economies, and prolong the pandemic, especially in the world's poorest nations.16 Many of these nations rely on an initial allocation from the COVAX Facility to access the vaccines. A forecast by the Duke Global Health Innovation Center in Durham, North Carolina, suggests that many low-income nations might not achieve mass vaccination for their populations until 2023 or 2024.17 This probable scenario could be counterproductive in the fight against the pandemic, which requires urgent intervention, collaboration, assistance, and solidarity on a global level. To address potential procurement challenges, AstraZeneca pledged to make its vaccine available on a “not-for-profit basis” and in perpetuity for the duration of the pandemic for low- and middle-income countries.17

Vaccination in Africa and Across the Globe

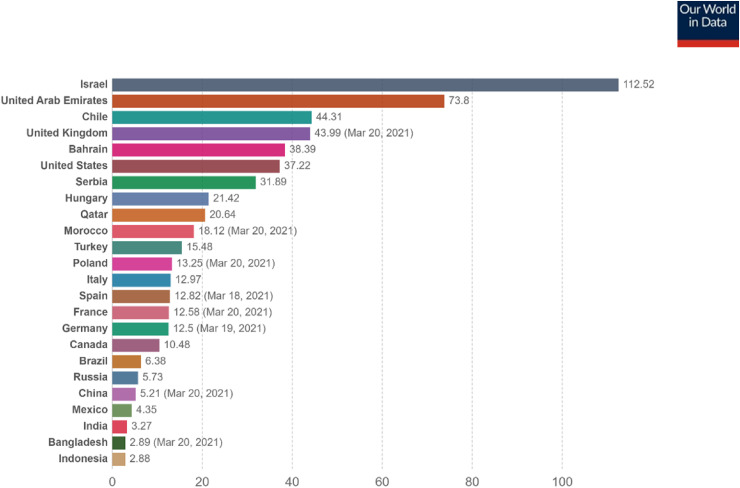

Data obtained from the Bloomberg COVID-19 vaccine tracker indicated that more than 447 million doses of the various COVID-19 vaccines had been administered in 133 countries as of March 21, 2021. This figure is just adequate to cover 2.9% of the world population. The global average rate currently stands at 11 million per day, and this implies it would require several years to cover a substantial world population in order to achieve global immunity. However, the rate increases steadily as more vaccines become available.1 Based on population coverage, Israel leads other nations because it administered a cumulative 9.7 million doses, which is adequate to cover 53.6% of its population as of March 21, 2021.1 Another source indicates that the rate of vaccination per 100 people had even reached 112.52.12 Israel so far has the highest vaccination rate per capita. It has surpassed even the countries that manufactured the available vaccines, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and Russia, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

COVID-19 vaccines doses administered per 100 people of countries’ population as of March 21, 202112 (updated 3/22/2021 09:40 London time). Total number of vaccination doses administered per 100 people. This is counted as a single dose and may not equal the total number of people vaccinated, depending on specific dose regimen (e.g., people receive multiple doses). Source: Our World in Data at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

The current global vaccination campaign has encountered inequitable access to the vaccines. Many low-income countries have yet to access any of the available vaccines. Africa is ranked the second largest and the second most-populous continent. However, a vast majority of the African states have yet to access the vaccines. Guinea in West Africa was the first low-income country that kickstarted vaccination with the Russian Sputnik V vaccine, with a paltry 25 doses.18 This has since increased to 26,000 doses, enough to cover 0.1% population coverage.1 Guinea has recorded 14,236 cases and 81 deaths of COVID-19 as of January 21, 2021.18 In North Africa, Morocco had administered 6.7 million doses with 9.4% population coverage. Egypt and Algeria had given 1315 and 75,000 doses, respectively, each covering about 0.1% of their populations. Rwanda had administered 333,000 doses and had coverage of 1.3%.1

In East Africa, Kenya had administered 20,000 doses, while Uganda had given 18,000 doses. These figures represent less than 0.1% population coverage for both countries. Similarly, in the continent's southern region, Angola and Zimbabwe had covered 0.1% of their populations. The two countries had administered 42,000 and 43,000 doses, respectively. Although South Africa has recorded the highest COVID-19 cases and mortalities in the continent, it has so far only administered 183,000 doses with 0.3% population coverage.1 In West Africa, Ghana, the first recipient of the COVAX Facility vaccine,19 had administered 458,000 doses with 0.8% population coverage. Senegal had given 159,000 doses, enough for 0.5% population coverage. On the other hand, Côte d’Ivoire had administered 24,000 doses, but covered less than 0.1% of the population.1

Nigeria, Africa's most populous nation, recently received an initial batch of 3.94 million doses of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine, which was licensed and produced by Serum Institute of India. This consignment came from the COVAX portfolio, and the country has commenced vaccination of its frontline health care workers and other vulnerable groups.20 So far, it has administered 8000 doses with less than 0.1% population coverage.1 Due to concerns for cold chain during distribution in lower-income countries, it is expedient for the authorities to procure vaccines such as Oxford-AstraZeneca that require standard refrigeration temperature. COVAX Facility delivers vaccines to its participating nations provided they meet certain requirements, including but not limited to cold chain storage capacity and logistics.19 The Janssen COVID-19 vaccine by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Companies, recently approved by the FDA, requires a single dose and standard refrigeration21 and could be the most convenient option for distribution and usage in resource-poor nations.

Most African nations, the vast majority of which are low-income and lower-middle-income nations, have yet to be on the global map of COVID-19 vaccine distribution and vaccination, as shown in Figure 1(B). This may pose a great challenge to the ongoing efforts to tackle the pandemic across the globe. However, the COVAX Facility could be to the rescue as it committed to deliver more than 2 billion doses by the end of 2021, including at least 1.3 billion donor-funded doses to be made available to 92 lower-income, COVAX-participating nations.14,20 The COVAX Facility had targeted to supply 90 million and 600 million doses of the vaccines to the African continent by the first quarter and before the end of 2021, respectively. It is expected that the 600 million dose allocation will be adequate to cover 20% of the continental population.20 The objective of the global COVAX initiative is to ensure rapid, fair, and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all countries regardless of income level.14 This initiative is laudable and offers a lifeline for countries, especially low-income countries, to access the vaccines and inoculate their most vulnerable populations.

Notwithstanding these initiatives, some nations may have entered private deals with the vaccine manufacturers to secure the vaccines in anticipation of a twist to the COVAX arrangement. In reality, it could be a daunting task for the Facility to book and ensure the distribution of millions of doses from different manufacturers to all the COVAX-participating countries. Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria are the only three African nations so far to have received the first round of allocation of the vaccines from the COVAX Facility,20,22 although allocations to other countries are underway. COVAX had existing agreements with Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, among others, to secure these vaccines for fair and equitable distribution to save lives, stabilize health systems, and enhance recovery of the global economy.14

Conclusion

The development of COVID-19 vaccines was a landmark and a source of hope to bring the COVID-19 global pandemic under control. Until every country, whether rich or poor, has access the vaccines, the pandemic will continue to disrupt lives and livelihoods because it does not discriminate on the basis of income or borders. Hence, COVID-19 vaccines are a global priority and remain paramount to the restoration of global normalcy.

As the rollout of safe and effective vaccines continues across the globe, high-income nations, world leaders, national governments, donor organizations, and other relevant stakeholders must sustain efforts to ensure fair and equitable distribution of the vaccines. The WHO's COVAX initiative must be supported to make vaccines available to all nations, especially the poorer economies, which may not have the financial capacity to procure adequate vaccination doses. This will hasten the ability to bring the pandemic under control and to impact the recovery of global economy. Furthermore, low-income countries, especially in Africa, must re-invest in research, health care, vaccines, and drug development and remain proactive in preparing against future pandemics. The logistical challenges that may hinder the effective distribution of the vaccines to the entire world population to achieve a pandemic-free universe must be confronted with all the necessary machinery.

Limitations of The Study

The current COVID-19 vaccination data is based on reports and datasets from the aforementioned tracking databases and is updated regularly to reflect the latest information. Furthermore, some countries may have commenced vaccination, but data records may not have been reflected in the databases as of the review date. It could be that official figures are not available for display or that updates to official sources have been delayed at the time of writing of this manuscript.

Author Biographies

Mohammed Al-Kassim Hassan is a faculty member at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Bayero University Kano, Nigeria. He holds a bachelor's degree in pharmacy and is currently a Ph.D. student at the Faculty of Pharmacy, Ankara University, Turkey. Due to his passion for pharmacy, he has practiced in diverse areas of pharmacy, including community, hospital, industry, and recently academia. He holds membership in several pharmaceutical associations, including the Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria, International Pharmaceutical Federation, and Nigeria Association of Pharmacists in the Academia, where he previously held the position of vice-chairman. Furthermore, he is a mentor to many undergraduate pharmacy students and has published several articles in local and international journals. His research interests include pharmaceutical analytics, drug design, and public health.

Sani Aliyu is on the academic staff at the Department of Microbiology, Umaru Musa Yar ádua University, Katsina, Nigeria. He holds bachelor's and master's degrees in microbiology. His research interests include cancer, microbiology, and genetics. He has authored many scientific articles, including A Rapid and Sensitive Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Detection of Pork DNA Based on Porcine tRNA lys and ATPase 8 Genes; Intrigues of Biofilm: A Perspective in Veterinary Medicine; Evaluation of Biofilm Formation and Chemical Sensitivity of Salmonella typhimurium on Plastic Surface; and Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), an Innovation in Gene Amplification: Bridging the Gap in Molecular Diagnostics: A Review.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Mohammed Al-Kassim Hassan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5423-4633

Sani Aliyu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4989-3770

References

- 1.Randall T, Sam C, Tartar A, Murray P, Cannon C. Bloomberg COVID-19 Vaccine tracker. Bloomberg. Accessed January 22 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/

- 2.World Health Organization. Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. 2021. Accessed March 12 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Target product profiles for COVID-19 vaccines (version 3). WHO. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-target-product-profiles-for-covid-19-vaccines [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Centre. Accessed March 10 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 6.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/scientific-brief-emerging-variants.html [PubMed]

- 7.Reardon S. The most worrying mutations in five emerging coronavirus variants. Scientific American Published online January 29, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-most-worrying-mutations-in-five-emerging-coronavirus-variants/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forni G, Mantovani A, On behalf of the COVID-19 Commission of Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome, et al. COVID-19 vaccines: where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Differ 2021;28(2):626–639. 10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burki TK. The Russian vaccine for COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(11):e85–e86. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30402-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BBC. Sputnik V, Covaxin and Covishield: what we know about India’s COVID-19 vaccines. Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-55748124

- 12.Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, et al. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Accessed January 23, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- 13.Yamey G, Schäferhoff M, Hatchett R, Pate M, Zhao F, McDade KK. Ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines. The Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1405–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. COVAX Announces new agreement, plans for first deliveries. 22 January 2021 News release. Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-01-2021-covax-announces-new-agreement-plans-for-first-deliveries [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Oxfam International 04 May 2020 press release. Vaccinating poorest half of humanity against coronavirus could cost less than four month’s big pharma profits. Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/vaccinating-poorest-half-humanity-against-coronavirus-could-cost-less-four-months

- 16.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at 148th session of the Executive Board. Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-148th-session-of-the-executive-board

- 17.Mullard A. How COVID vaccines are being divvied up around the world. Nature News. 30 November 2020.Accessed January 23 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03370-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guinea begins COVID-19 vaccinations on government ministers with Russia’s Sputnik V. World Stage. Accessed January 21 2021. https://www.worldstagegroup.com/guinea-begins-covid-19-vaccinations-on-govt-ministers-with-russias-sputnik-v/

- 19.World Health Organization. First COVID-19 COVAX vaccine doses administered in Africa. Accessed March 10 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-03-2021-first-covid-19-covax-vaccine-doses-administered-in-africa

- 20.UNICEF. COVID-19 vaccines shipped by COVAX arrive in Nigeria. UNICEF press release 02 March 2021. Accessed March 10 2021. https://www.unicef.org/wca/press-releases/covid-19-vaccines-shipped-covax-arrive-nigeria

- 21.The U.S. FDA has granted the Janssen covid-19 vaccine an emergency use authorization (EUA). Accessed March 10 2021. https://www.janssencovid19vaccine.com/

- 22.UNICEF. COVAX Publishes first round of allocations. UNICEF press statement 02 March 2021. Accessed March 10 2021. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covax-publishes-first-round-allocations