Abstract

Although there is a growing volume of research on violence against women, violence against older women has received little attention to date. Little is known about the experience of elder abuse, discrimination, loneliness, and health among older women, in particular in the era of COVID-19 when our lives have been changed drastically. Using two waves of survey data (N = 1,498), this study compared the estimates of elder abuse and age discrimination before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, examined their associations with physical and mental health, and explored the mediating effects of loneliness on the associations in two independent samples of older women in Hong Kong. Reductions in some forms of abuse and discrimination against older women during the pandemic were observed. Findings from regression analyses show that elder abuse and age discrimination were associated with poorer health, and these associations were mediated by loneliness.

Keywords: elder abuse, discrimination, violence against women, loneliness, health, COVID-19

In the 65th session of the Commission on the Status of Women held in March 2021, the United Nations underlined the importance of addressing gender inequality and discrimination faced by women and reaffirmed that women of all ages should be protected from violence and discrimination (Commission on the Status of Women Sixty-Fifth Session, 2021). To date, violence against women, which affects one in every three women and causes lifelong harm to their health, remains an international health concern (World Health Organization, 2018). Governments, professionals, and other stakeholders worldwide have been making efforts to combat the problem in recent decades. For example, the World Health Organization has endorsed the global plan of action to urge its member states and international partners to take actions to address the issue under different strategic areas (World Health Organization, 2016). Despite the growing effort in the world to end violence against women, there is far less attention on violence against older women.

Violence and Discrimination Against Older Women

Elder abuse, defined as “a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action in any relationship in which there is an expectation of trust, which cause harm or distress to an older person” (World Health Organization, 2021a, p. 11), is a serious public health issue that affects one-sixth of the population aged 60 years and older over the past year (World Health Organization, 2021b). Elder abuse and mistreatment, like other types of violence, have been demonstrated to be gender-based (Amstadter, Cisler, et al., 2011; Amstadter, Zajac, et al., 2011; Laumann et al., 2008). Findings from meta-analyses show that older women are more likely to be abused than men, and such gender inequality is especially obvious among non-Western populations than their Western counterparts (Ho et al., 2017; Yon et al., 2017). Longer life expectancy of women in conjunction with deterioration in cognitive and functional capacities with age (Roberto, 2016), greater vulnerability due to social norms and social roles that support violence by men (Stark & Seff, 2021), higher likelihood to live with the perpetrator (Acierno et al., 2009), as well as greater risks of domestic violence victimization throughout life (Mitszjurka et al., 2016) may contribute to the link between elder abuse and female gender.

Age discrimination, on the other hand, refers to the prejudice and discrimination directed towards others based on their age. Age discrimination may occur equally in both genders; however, older women are often expected to experience more disadvantages than older men. For example, older women workers disproportionally face greater risks of job loss due to automation and technological change (World Health Organization, 2021b). Gender-based age discrimination in various aspects such as employment and caring responsibilities has been believed to be one of the causes for older women's vulnerability. Women who have experienced discrimination are demonstrated to have significantly lower income and a greater risk of poverty, leading them to face greater challenges and inequalities in old age (Birtha & Holm, 2017; World Health Organization, 2021b).

COVID-19 and the Shadow Pandemic

COVID-19, declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020, has brought devastating impacts on individuals all over the world. The disease has spread rapidly, affecting more than 220 countries and regions and causing over 4.3 million deaths as of August 13, 2021 (WHO, 2021d). The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating impacts on older individuals. Despite the similar risk of contracting COVID-19 across age, older persons, especially those with comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, are more prone to severe illness and higher mortality (Gencer, 2020). Risks of mortality greatly increase among older persons aged 50 or above: the infection fatality ratio increases from 0.01% to 0.14% among individuals aged 50 years or above, and jumps to 5.6% in the population older than 65 years (Mallapaty, 2020). It has been estimated that approximately 80% of COVID-19-related deaths are older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Currently, disease prevention strategies, including social distancing, quarantines, lockdowns, and social and movement restrictions, are still widely implemented in many countries to protect vulnerable groups.

In addition to the health impacts directly brought by COVID-19, individuals, in particular women and girls, often suffer from indirect harms related to the pandemic. Emerging data from frontline reports, media coverage, and empirical studies have shown that all types of violence against women have intensified since the outbreak of COVID-19. Termed “the shadow pandemic,” the phenomenon has been growing amidst the health crisis, and it is expected to be one of the greatest human rights violations in the era of COVID-19 (UN Women, 2021).

Elder Abuse and Discrimination in Older Women During the Pandemic: Possible Pathways

Data on the prevalence and correlates of elder abuse and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic are extremely scarce; yet, there has been preliminary evidence for the possible pathways underlying the associations between COVID-19 and violence against older persons (HelpAge, 2021). Social distancing and confinement during the pandemic can be examples of the risk factors leading to violence in domestic settings. On one hand, social distancing restrictions can be of vital importance to stop the spread of COVID-19; on the other hand, they inherently limit one's physical activities and promote social isolation, which may potentially lead to the detriment of health (Holmes et al., 2020). Although all ages can be affected, the impacts of these restrictions on social isolation and loneliness can be greater among older persons (Rina et al., 2020). To avoid infection, older persons are often requested to stay at home. Due to the restrictions on social gatherings, suspensions of in-person social services, and closures of facilities, they may have very limited contact with family, friends, neighbors, and other significant others during the pandemic. Older persons, who are forced to struggle with social isolation and loneliness, are at risk of depression, anxiety, declined cognitive functions, poor immunity, and poor physical health (e.g., Elovainio et al., 2017; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Shankar et al., 2013).

In addition to the negative health consequences, social isolation and loneliness due to the social distancing restrictions may put an individual at greater risk of abuse in domestic settings. Although staying at home may minimize the risks of contracting COVID-19, for victims of elder abuse this restriction can be equal to confinement in the place where physical, psychological, and sexual violence occurs (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020). During the pandemic, not only may victims of elder abuse be trapped with the potential perpetrator(s) at home, but they may also find it harder to reach out to trustable figures in a safe manner. In this case, detection and service provision can be extremely challenging (Elman et al., 2020).

Age discrimination among older persons is another alarming issue during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a recent report by WHO (2021c), the pandemic has exposed ageist prejudice and stereotypes against older persons due to the discriminatory practices in access to different critical resources and services. Similar to elder abuse, age discrimination can inflict pervasive and harmful effects on physical and mental health among older persons (Chang et al., 2020). It is noted that age discrimination can be a worrying issue when ageist thoughts inspired by the COVID-19 restrictions exacerbate as the consequences of necessary social restrictions increase, leading to unjust utilitarian beliefs that the needs of the many should outweigh the needs of the few (Han & Mosqueda, 2020).

Gender inequality in abuse occurring in domestic settings may be amplified in some populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among female victims of domestic violence, social and movement restrictions may imply more time spent with abusive men and fewer opportunities to seek help or support outside the family (Usher et al., 2020). Perpetrators may take advantage of the restrictions to exert control and power, knowing that women are trapped at home and are losing connections with others (WHO, 2020). Hence, it is extremely important to acknowledge the potential downside of social distancing restrictions in magnifying the severity of abuse among older women.

Situation in Hong Kong

As one of the first places affected by COVID-19, Hong Kong has adopted quite different approaches to contain COVID-19 than those in other countries. Hong Kong did not lock down following the outbreak of the disease in January 2020, and residents enjoyed a moderate degree of mobility in the city. The Hong Kong government enacted several disease prevention measures, including compulsory face mask wearing, ban of large-group social gatherings, and physical distancing. Despite the less strict measures, Hong Kong has been regarded as relatively successful in controlling the infection rate (Lam et al., 2020).

At the time of writing, there has been no empirical study on violence against women or older women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. The only published research focused on child maltreatment in the Hong Kong population and provides some preliminary evidence for the increased risk of violence due to economic instability during the pandemic (n = 600, Wong et al., 2021).

The Present Study

To protect women whose lives are greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital to understand the ongoing impacts of the pandemic. Empirical research that provides reliable estimates of violence against women is essential for us to understand how the problem evolves under the influence of the pandemic. Older women, who are often regarded as a marginalized population, deserve particular attention. This study is an attempt to answer three research questions:

How did the pandemic impact abuse and discrimination among older women?

Were elder abuse and age discrimination against older women associated with poorer physical and mental health?

Did loneliness play a mediating role in the associations between elder abuse, discrimination, and health among older women?

To answer the research questions, we compared two waves of population-based Chinese samples of older women collected before and during the pandemic in Hong Kong. We also explored the effects of elder abuse, age discrimination, loneliness, and financial status on physical and mental health among older women, with an emphasis on how loneliness plays a role in the associations between elder abuse, age discrimination, and women's physical and mental health.

Method

Research Design

A quantitative survey was conducted to examine subjective well-being among a randomized population-based sample of community-dwelling older adults in Hong Kong from 2019 to 2021. All individuals who were 55 years of age or above, residing in Hong Kong during the time of survey, and able to understand Cantonese were eligible to participate. Data collection had begun in October 2019 and was halted in January 2020 due to the outbreak of COVID-19 in the city. The telephone survey was then resumed in December 2020, and data collection was completed in January 2021. Thus, the dataset of the survey consisted of two waves of telephone surveys, providing two independent samples from the same population.

This study took a repeated cross-sectional approach and analyzed data of the two independent samples recruited at two different time points: Wave 1 (collected between October 2019 and December 2019) and Wave 2 (collected between December 2020 and January 2021) of the survey study. In Hong Kong, the first diagnosed case of COVID-19 was reported in January 2020, which was in between the two waves of surveys. In this study, we used the Wave 1 and Wave 2 data to represent data before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively.

Participants and Data Collection Procedure

Participants were recruited with a two-level sampling procedure. First, mobile and landline numbers were randomly drawn from the known prefixes assigned to various telecommunication service providers under the numbering plan of the Office of the Communications Authority, Hong Kong SAR Government. To ensure the degree of randomization, a computer-based random digit dialing procedure was conducted to generate telephone numbers for participant recruitment. After that, respondents were invited to participate in the study if they met the inclusion criteria. In the case of landline numbers, when there was more than one eligible individual, one respondent would be selected with the “next birthday” method.

Data collection was conducted by a professional research agency. Eligible participants were contacted by trained research assistants under close supervision of the research team, and they received the study information and had the rights of participants explained to them over the phone. Oral consent was obtained from each participant before the survey began. Participants responded to a structured questionnaire with the guidance of the research assistants. They were fully informed that they could omit any questions during the telephone survey. All study procedures and protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the university.

Over 13,700 telephone numbers were sampled and contacted in the two waves of the survey. A total of 1,483 and 947 eligible older adults were identified in Wave 1 and Wave 2, respectively, and a total of 1,209 older adults completed the survey in Wave 1 (response rate = 81.5%) and another 819 in Wave 2 (response rate = 86.5%). The nonresponses were mainly due to refusal of participation with no reason given or inability to make time for participation. This study used the data of older women only, yielding a sample of 910 complete records in Wave 1 and 588 in Wave 2 (N = 1,498).

Measures

Physical and mental health

Self-perceived health condition was assessed with two single items: (“How would you rate your current physical health?”) and (“How would you rate your current mental health?”). Participants were asked to rate their health conditions with a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“very poor”) to 5 (“very good”).

Elder abuse and age discrimination in the past 12 months

Elder abuse was assessed with three items which captured participants’ experience of (i) physical abuse (“In the past 12 months, has there been anyone who hurt you or intended to hurt you?”); (ii) psychological or verbal abuse (“In the past 12 months, has there been anyone who yelled at you or hurt you verbally to make you distressed?”); and (iii) financial abuse (“In the past 12 months, has there been anyone who used or transferred your money or property without your permission?”). Age discrimination was measured with another three items which asked about participants’ experience of (i) unfair treatment or prejudice; (ii) disrespect or disregard, and (iii) harassment or refusal of service because of their age. Participants rated their frequency of experience of abuse and discrimination using a five-point Likert scale, from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“always”). Scale scores for each variable ranged from 0 to 12, with a higher score indicating more frequent experience of elder abuse or age discrimination in the past year. Participants who reported an experience of abuse or discrimination were also asked to indicate the identity of the abuser, with options including their partner, children, friends, and others. In this study, participants who gave responses other than 0 (“never”) to these six items were regarded as victims of abuse and discrimination.

Loneliness

Loneliness was assessed with the Chinese version of the six-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, a validated scale for overall, social, and emotional loneliness (De Jong Gierveld, 2006; Leung et al., 2008). Sample items included “I experience a general sense of emptiness” and “There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems.” Possible responses were “no” (0), “more or less” (1), and “yes” (2), which were suggested in the original study for telephone surveys. Scale scores ranged from 0 to 12, and higher scores reflected higher levels of loneliness. The Chinese version of the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale has achieved satisfactory reliability in Chinese populations (Leung et al., 2008), and in the current sample (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.55).

Financial health

Participants were asked to rate their financial health with the item, “How would you rate your current financial status?” using a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“very poor”) to 5 (“very good”).

Demographic characteristics

Age, relationship status, and highest educational attainment were recorded as covariates in this study.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized demographic characteristics and the rates of elder abuse and age discrimination of the participants using descriptive statistics. We also compared the rates of abuse and discrimination obtained between Wave 1 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) and Wave 2 (during the COVID-19 pandemic) using chi-square tests and Fisher's exact tests. To ensure the representativeness of the final samples, raw data collected were rim-weighted according to the distributions of age and educational attainment of the Hong Kong older adult population (aged 55 years or above) as obtained from the Population By-census data in 2016 (Census & Statistics Department, 2018).

We performed hierarchical multiple regression analyses to explore the factors predicting self-perceived physical and mental health among older women. In each of the regression analyses, four blocks of independent variables were entered in the following order: (i) demographic variables, which included age, relationship status, and educational attainment; (ii) elder abuse and age discrimination; (iii) loneliness; and (iv) financial health. To evaluate the mediating effect of loneliness on the association between abuse/discrimination and health, we also conducted a series of Sobel tests. In this study, Sobel tests, which were recommended in previous research for testing of mediation (Mackinnon et al., 2002), evaluated the changes in the estimated parameters for elder abuse and age discrimination when loneliness (i.e., the mediating variable) was introduced as a predictor in the models predicting physical and mental health.

All analyses in this study were conducted with IBM SPSS software version 26.0, and two-sided p values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All missing data were handled with the pairwise deletion method to maximize the data available.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Almost half of the older women were 55–59 years of age (Wave 1 = 48.9%, Wave 2 = 47.8%), approximately one fifth were aged 75 years or above (Wave 1 = 21.1%, Wave 2 = 23.0%), and the rest were 60–74 years (Table 1). The majority were married (Wave 1 = 57.8%, Wave 2 = 65.5%), and had completed secondary education or below (Wave 1 = 82.7%, Wave 2 = 80.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Two Waves of Study Samples (N = 1,498).

| Wave 1 (n = 910) | Wave 2 (n = 588) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | (%) | n | % |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 55–59 | 445 | (48.9) | 281 | (47.8) |

| 60–64 | 96 | (10.5) | 45 | (7.7) |

| 65–69 | 85 | (9.3) | 57 | (9.7) |

| 70–74 | 91 | (10.0) | 65 | (11.1) |

| 75 or above | 192 | (21.1) | 135 | (23.0) |

| Missing | 1 | (0.1) | 6 | (1.0) |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 526 | (57.8) | 385 | (65.5) |

| Divorced or widowed | 255 | (28.0) | 135 | (23.0) |

| Single | 123 | (13.5) | 58 | (9.9) |

| Missing | 6 | (0.6) | 10 | (1.7) |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| Primary/Elementary school or below | 280 | (30.8) | 161 | (27.4) |

| Secondary/High school | 472 | (51.9) | 312 | (53.1) |

| Certificate or diploma | 63 | (6.9) | 38 | (6.5) |

| University | 68 | (7.5) | 45 | (7.7) |

| Postgraduate | 26 | (2.9) | 24 | (4.1) |

| Missing | 1 | (0.1) | 8 | (1.4) |

Note. Data were rim-weighted according to the distributions of age and educational attainment of the Hong Kong population aged 55 or above reported in the 2016 By-census of Hong Kong.

Elder Abuse and Age Discrimination

The most commonly reported type of elder abuse was psychological abuse (Wave 1 = 20.2%, Wave 2 = 15.6%). Reported rates of physical abuse and financial abuse were 0.4%–2.0% and 1.1%, respectively. Age discrimination was experienced by 6.6% to 19.4% of older women. About 16.2%–19.4% reported unfair treatment by others because of their age, 15.7%–18.7% reported disrespect or disregard, and 6.6%–10.2% experienced harassment or refusal of service (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of Elder Abuse and Age Discrimination in the Past Year in the Two Waves of Samples.

| Wave 1 (n = 910) | Wave 2 (n = 588) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | (%) | n | % | χ2 | p |

| Elder abuse | ||||||

| Physical | 19 | (2.0) | 2 | (0.4) | N.A.a | 0.005 |

| Psychological | 184 | (20.2) | 92 | (15.6) | 4.97 | 0.026 |

| Financial | 10 | (1.1) | 6 | (1.1) | N.A.a | 1.000 |

| Age discrimination | ||||||

| Unfair treatment | 148 | (16.2) | 114 | (19.4) | 2.42 | 0.121 |

| Disrespect or disregard | 170 | (18.7) | 92 | (15.7) | 2.28 | 0.131 |

| Harassment or refusal of service | 93 | (10.2) | 39 | (6.6) | 5.72 | 0.017 |

Note. Data were rim-weighted according to the distributions of age and educational attainment of the Hong Kong population aged 55 or above reported in the 2016 By-census of Hong Kong.

Since the counts of physical abuse and financial abuse in Wave 2 were relatively low, Fisher's exact tests were used instead of chi-square tests in the two variables.

Significant changes in the rates of some forms of abuse and discrimination across time were observed. Specifically, the proportions of older women who reported physical abuse, psychological abuse, and harassment or refusal of service dropped significantly from Wave 1 to Wave 2 (physical abuse = 2.0% vs. 0.4%, psychological abuse = 20.2% vs. 15.6%, harassment or refusal of service = 10.2% vs. 6.6%, all p < .05). An increasing trend was noted in unfair treatment from Wave 1 (16.2%) to Wave 2 (19.4%), yet the change was not statistically significant.

Factors Associated with Self-Perceived Health

Findings of the regression analyses revealed significant associated factors of physical and mental health perceived by the older women in this study. Elder abuse (β = −.09, p < .01) and age discrimination (β = −.10, p < .01) were significantly related to poorer physical health after adjusting for relationship status and educational attainment. When loneliness, a significant predictor for poorer physical health itself (β = −.21, p < .001), was added in the regression model, the negative association between elder abuse and physical health became non-significant (β elder abuse = −.04, βdiscrimination −.06, p > .05). In the final model (R2 = .138, F = 19.60, p < .001), where financial health added extra explanation power for the variance of physical health (β = .25, p < .001), age discrimination (β = −.08, p < .05), and loneliness (β = −.12, p < .001) remained as significant negative predictors.

Concerning the mental health of older women, age discrimination (β = −.14, p < .001), but not elder abuse (β = −.07, p > .05), was significantly associated with poorer health after the adjustment for demographic variables. Loneliness was significantly related to poorer mental health (β = −.25, p < .001), and its effect remained even after the addition of financial health in the final model. In the final model (R2 = .1013, F = 15.79, p < .001), mental health was negatively predicted by age discrimination (β = −.09, p < .01) and loneliness (β = −.21, p < .001), and positively predicted by financial health (β = .17, p < .001). Elder abuse, once again, was not a significant correlate of mental health in the final model (β = .00, p > .05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Physical Health and Mental Health (N = 910).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β |

| Physical health | ||||||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.08* |

| Relationship status | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.10** | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.08* | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Educational attainment | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09* | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.09* | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Elder mistreatment | ||||||||||||

| Elder abuse | −0.27 | 0.11 | −0.09* | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.03 | |||

| Age discrimination | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.10* | −0.09 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.06 | |||

| Loneliness | −0.42 | 0.07 | −0.21*** | −0.30 | 0.07 | −0.15 | ||||||

| Financial health | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.25*** | |||||||||

| R 2 | .023 | .046 | .083 | .138 | ||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 7.355*** | 8.827*** | 13.327*** | 19.596*** | ||||||||

| Mental health | ||||||||||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Relationship status | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.02 |

| Educational attainment | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.10* | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.09* | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Elder mistreatment | ||||||||||||

| Elder abuse | −0.22 | 0.11 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.00 | |||

| Age discrimination | −0.22 | 0.06 | −0.14*** | −0.15 | 0.06 | −0.10* | −0.14 | 0.06 | −0.09* | |||

| Loneliness | −0.54 | 0.08 | −0.25*** | −0.45 | 0.08 | −0.21*** | ||||||

| Financial health | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.17*** | |||||||||

| R 2 | .006 | .036 | .089 | .113 | ||||||||

| F for change in R2 | 2.723*** | 7.016*** | 14.302*** | 15.789*** | ||||||||

Note. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Loneliness as a Mediator

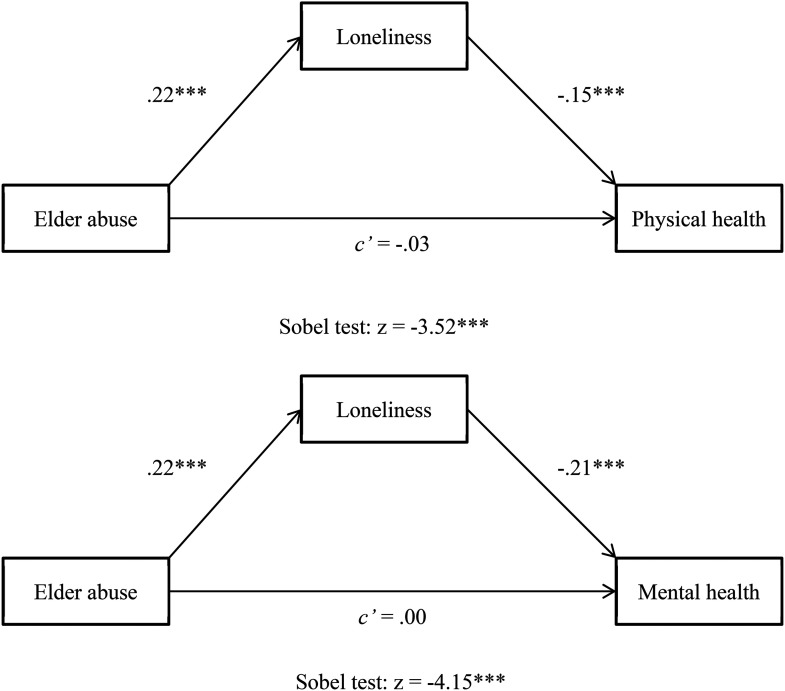

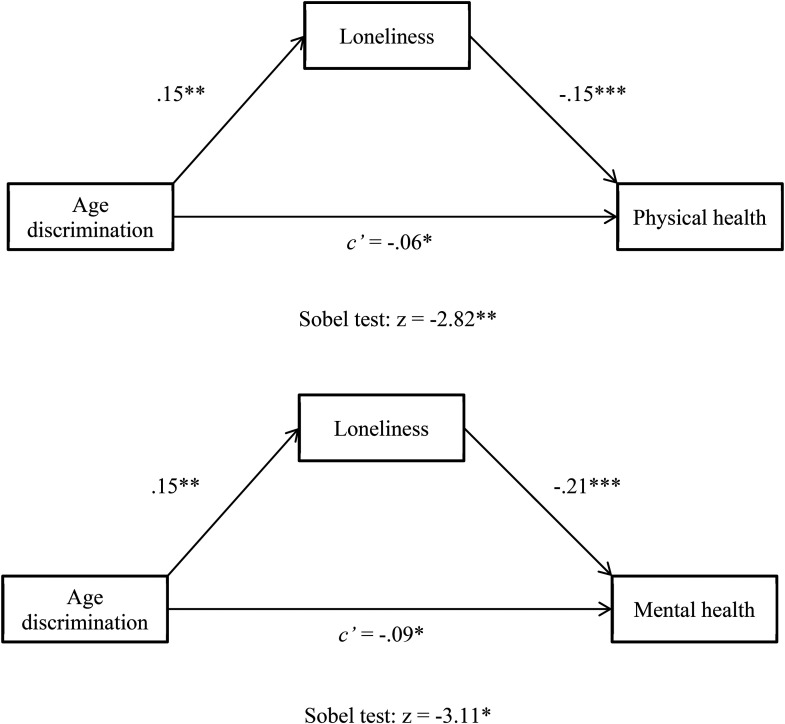

Results of the Sobel tests provided evidence for the mediating effects of loneliness on the relationships between abuse/discrimination and self-perceived health in older women. In this study, loneliness mediated the negative association between elder abuse and physical health (Sobel z = −3.52, p < .001) as well as that between elder abuse and mental health (Sobel z = −4.15, p < .001) (see Figure 1). Similarly, loneliness also mediated the negative association between age discrimination and physical health (Sobel z = −2.82, p < .01), as well as that between age discrimination and mental health (Sobel z = −3.11, p < .001) (see Figure 2). It is noteworthy that the associations between age discrimination and physical/mental health were reduced in magnitude, yet remained statistically significant, after the addition of loneliness in the model.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between elder abuse and self-perceived health as mediated by loneliness. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between age discrimination and self-perceived health as mediated by loneliness. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

Using a large, population-based sample of community-dwelling older women in Hong Kong, this study revealed the prevalence of elder abuse and age discrimination in the era of COVID-19, explored its effects on physical and mental health, and examined the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between elder abuse and discrimination against older women and their health. As one of the first to compare the prevalence of elder abuse and age discrimination before and during the COVID-19 pandemic empirically, our findings show some consistency with previous studies. For instance, consistent with previous research (e.g., Lindert et al., 2013), psychological abuse was the most prevalent form of elder abuse, followed by financial or economic abuse and physical abuse. We observed past-year rates of 0.4%–2% for physical abuse, 16%–20% for psychological abuse, and 1% for financial abuse, which were comparable to those reported in the literature. In a systematic review and meta-analytic study on elder abuse, the pooled prevalence estimate of 52 studies across 28 countries was 3% (2%–4%) for physical abuse, 12% (8%–16%) for psychological abuse, and 7% (5%–9%) for financial abuse (Yon et al., 2017). Apart from elder abuse, age discrimination was also commonly experienced by older women in Hong Kong. Although the overall rates revealed here (7%–19%) were comparatively lower than that estimated by the WHO (>30% among all ages, WHO, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d), current findings indicated that at least one in every five older women suffered some form of elder abuse or age discrimination in the past year, highlighting an alarming severity of this global health problem in the city.

Abuse and Discrimination Against Older Women During the Pandemic

Surprisingly, when comparing the rates of abuse and age discrimination against older women before the COVID-19 pandemic and those during the pandemic, this study demonstrated a drop in the rates of physical abuse, psychological abuse, and harassment or refusal of service because of one's age during the pandemic. Based on previous findings (Elman et al., 2020; Weissberger et al., 2020), it was expected that social isolation and confinement at home during the pandemic would turn home into a potential venue for greater risks of violence against older women. Yet, results in this study provided some evidence for a possible reduction in elder abuse and age discrimination despite the changing societal context. In line with current findings, a preliminary observational study of emergency department admission data demonstrated convergent results that admission due to physical domestic violence declined by 48% during the pandemic (Muldoon et al., 2021); another crime report study in Australia revealed a lower crime figure in March 2020 when compared with the figure forecasted with the crime data from February 2014 to February 2020 (Payne et al., 2020). The mixed findings on the trends in abuse and discrimination might reflect a decrease of reported cases rather than a reality, or the complexity of the issue. During the pandemic, individuals were often advised to stay at home to prevent the spread of the virus. In the case of violence in domestic settings, the presence of family members other than the perpetrator(s) may reduce the likelihood of violent incidents against older women and protect them from abuse. In cases where the abuse victims and perpetrator do not live in the same household, social distancing restrictions, lockdowns, and stay-at-home orders could result in limited direct contacts with potential perpetrator(s), leading to a reduction in violence. Another possible reason for the reduction in elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic may be greater informal social control of violence by family members and neighbors. Informal social control, which refers to the reactions of ordinary individuals to achieve order and protect the weak, has been demonstrated to help reduce crimes and violence, including child maltreatment (Emery et al., 2015) and intimate partner violence against women (Emery et al., 2015).

Yet, it should be noted the decreasing trend of elder abuse and age discrimination against older women might not indicate a true reduction in violence and requires ongoing monitoring. As one of the most hidden types of violence, elder abuse in domestic settings has consistently been underreported (Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc. et al., 2011). Before the pandemic, it was estimated that only one in every 24 cases of elder abuse was reported (Amstadter, Cisler, et al., 2011). The situation might happen for the worse when older women are trapped at home with perpetrator(s) of violence (Piquero et al., 2020). Victims might be unable to articulate the assault as they are isolated and fail to reach out to others to seek help due to the social and movement restrictions (Elman et al., 2020). In this sense, the reduction of elder abuse during the pandemic might only reflect the increased severity of underreporting. Undoubtedly, social and healthcare service providers should interpret the current findings with caution, so as to avoid overlooking any victim of elder mistreatment in the future.

Health Impacts of Abuse and Discrimination Against Older Women

Regarding the association between elder mistreatment and health, current findings provide evidence confirming the negative impacts of elder abuse and age discrimination on both physical and mental health among older women. These findings are consistent with literature that shows that elder abuse is a risk factor for various adverse health outcomes (e.g., Allen, 2019; WHO, 2021b; Yunus et al., 2017). In a population study in New Zealand (Yeung et al., 2015), elder abuse was shown to predict poorer physical health, mental health, and health-related quality of life, with effect sizes ranging from 0.26 to 0.70. Similar associations have been demonstrated between age discrimination and health, and the WHO global report on ageism has highlighted the negative consequences on health among older persons (WHO, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d). For example, ageism is linked to poor physical and mental health in general, poor sexual health, cognitive impairment, depression, risky health behaviors, and even early death. It is noteworthy that, despite the well-documented negative health consequences of elder abuse and ageism, the associations might not necessarily be unidirectional. Instead, some researchers have suggested that abuse and poor health could form a vicious cycle: abuse might hamper physical and mental health; and poor health might lead to various risky health behaviors and greater dependence on others which could further increase the risk of future abuse (Chmielowska & Fuhr, 2017).

Loneliness as a Mediator

One of the key findings of this study was the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between elder mistreatment and health. The associations between elder mistreatment, loneliness, and health have been consistently revealed in the literature (e.g., Schofield et al., 2013; Waldegrave, 2018); and our findings extended current knowledge by showing that loneliness could mediate the negative health impacts of elder abuse and age discrimination. In other words, it might be the feeling of loneliness aroused by the abuse and discrimination incidents that is directly associated with the poor physical and mental health perceived by older women. It has been pointed out in a review that loneliness, as distinct from social isolation, solitude, and living alone, could induce harmful effects on elderly health (Ong et al., 2016). Loneliness is associated with adverse health behaviors (e.g., reduced physical activity and alcohol dependence), sleep impairments (e.g., shorter sleep duration), biological dysregulation, and negative social cognition, which are key mechanisms underlying its impacts on hampered health and increased mortality.

In the era of COVID-19, the complex of elder abuse and loneliness might be further compounded by the social and movement restrictions related to the pandemic (Du & Chen, 2021; Makaroun et al., 2020). Lockdowns, social distancing policies, and stay-at-home orders might lead to social isolation and reduced social support among older women, who have been advised to stay at home because of their greater mortality and morbidity related to COVID-19 (Wong et al., 2020). In Hong Kong, social distancing measures such as restrictions on group gathering and closure of facilities have been implemented since 2020. Older women are prone to a reduction or a loss of social connection. The objective deprivation of social life might then exacerbate the subjective feeling of loneliness, which may have detrimental effects on both physical and mental health among elder abuse victims (Kasar & Karaman, 2021).

The robust effects of loneliness on mediating the negative associations between elder abuse, age discrimination, and health may warrant interventions targeting the reduction of loneliness and social isolation. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, psychological interventions including home visits and cognitive behavioral therapies have been shown as effective in reducing loneliness in older persons (Ong et al., 2016). However, during the pandemic, services might not be delivered in a face-to-face approach, and the mode of support to reduce loneliness may need to change. In recent years, there have been efforts in developing interventions assisted by digital technology for older persons (Masi et al., 2011). Digital technology interventions may involve mobile apps, robots, sensors, and internet-based social networking tools (Pu et al., 2019). Studies have provided preliminary evidence supporting their effectiveness in reducing loneliness; however, a recent meta-analysis has shown that the effectiveness might be weak (Shah et al., 2021). Clearly, there is a need for more age-friendly technology-assisted interventions that are effective for reducing loneliness among older persons in the era of COVID-19.

The Role of Financial Health among Older Women

Good financial health appeared to be a positive correlate of physical and mental health among older women. In line with previous research (Huang et al., 2020), a lower level of financial strain was associated with better self-perceived physical and mental health. The associations between financial health and well-being can be both direct and indirect: On one hand, better financial health may imply better resources to promote health in general; on the other hand, financial status may have some extra indirect effects on seniors’ health as financial instability could be a risk factor for family conflicts and violence (Chang & Levy, 2021). Researchers have suggested that perceived financial strain reported by older persons might reflect the financial instability of the family as a whole, and the overall financial instability could increase the risk of caregiver stress, rendering older persons vulnerable to abuse. The link between financial status and health among older adults may give valuable insights especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, where income instability and financial strain could be alarming issues in the community. Current findings may shed light on the importance of promoting both objective financial stability and subjective financial security so as to foster well-being among older persons.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. A major limitation was that we extracted data from a large survey study and based our analysis of change in elder mistreatment rates on different cross-sectional surveys instead of on the same group of older persons over time. Yet, the two waves of the sample used in this analysis were recruited and surveyed with the same data collection procedures and the same research protocol, and the multilevel sampling methods did maximize the representativeness of the samples. Although this study was not able to compare the changes in elder mistreatment over time at the individual level, findings did provide important insights into the changes before and during the pandemic at an aggregate level. Another limitation related to the dataset was the failure to include more variables in the regression models. As data were extracted from a larger study, we had no control over the variables to be assessed. It could be meaningful to include variables such as social support, health behaviors, and morbidity related to COVID-19 in the model explaining elderly health during the pandemic. The use of single items to measure self-perceived physical, mental, and financial health in this study might be subject to self-reporting biases, which limited the interpretation of the current results. Self-perceptions might not always accurately reflect actual situations in reality. Yet, there is also evidence that supports the reliability and validity of single items assessing health, particularly in large-scale surveys (Bowling, 2004). Finally, the use of telephone surveys to collect data may lead to biases in the sample recruited. As one of the inclusion criteria was the ability to communicate in Cantonese, older women with cognitive impairments might be excluded due to difficulties in communication. Older persons with cognitive impairments (e.g., dementia and Alzheimer's disease) are often believed to be more vulnerable to abuse (Cooper & Livingston, 2020), and exclusion of this group of older women might inevitably lower the rates of elder abuse and age discrimination. Future research may consider the inclusion of older persons with cognitive impairments with the use of proxy reports.

Conclusion

The United Nations Commission on the Status of Women stresses the importance of eliminating all forms of violence, discrimination, and gender inequality against women (Commission on the Status of Women Sixty-Fifth Session, 2021). However, current findings show that across time rates of elder abuse and age discrimination against older women were high, indicating that a large number of women were facing challenges to enjoying their full human rights. Despite the possible reduction in elder mistreatment during the pandemic, the reality and reasons behind this change should be further examined. The significant mediating role of loneliness in the associations between elder mistreatment and hampered health, together with the potential protective function of good financial health, sheds light on the need for the development of effective interventions to end violence against older women in the future. Older women may benefit from continuous support to reduce the risk of negative health outcomes. Professionals, policymakers, and service providers should examine innovative intervention approaches for the reduction of loneliness in the event of future pandemics.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the editors and reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. The authors would also like to thank the Wofoo Foundation for funding this project.

Authors Biographies

Elsie Yan is professor and associate head at the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. She received her PhD in Psychology from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has been conducting research on elder abuse, elder sexuality, and dementia caregiving.

Daniel W.L. Lai is chair professor and dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Hong Kong Baptist University. His research expertise includes health and mental health of the aging population and culturally diverse groups, culture and immigration, and outcome and impact evaluation. Daniel sat on the Board of Directors of the American Society on Aging and the Canadian Association of Gerontology in the past. He is also current Vice-President of the Hong Kong Association of Gerontology.

Vincent W. P. Lee is attached to the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Dr. Lee is a registered social worker in Hong Kong and has recently been working on research projects related to public welfare attitudes, social service evaluations, employment of older adults, and the livelihood of ethnic minorities in Hong Kong. He has also authored a number of articles published in international academic journals.

Xue Bai is an associate professor at the Department of Applied Social Sciences and Director of the Institute of Active Ageing at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Dr Bai's research focuses on three interrelated areas in social gerontology: 1) intergenerational relationships and care arrangements in aging families, 2) active aging and subjective well-being in later life, and 3) social policy and social care in aging societies. Dr. Bai's work has been widely published in renowned international journals. Currently, she is an appointed member of the Social Welfare Advisory Committee and Elderly Commission advising the HKSAR Government on aging and social welfare policy matters.

Haze K. L. Ng is currently a research associate at the Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University. She received an M.Sc. in Research Methods in Psychology from University College London, United Kingdom, and an B.S.Sc in Psychology from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Since 2009, she has been working with different research teams on projects related to partner violence, child abuse and neglect, and elder abuse in Hong Kong and China.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project is funded by the Wofoo Foundation, Hong Kong SAR.

References

- Acierno R., Hernandez-Tejada M., Muzzy W., Steve K. (2009). National elder mistreatment study. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/226456.pdf

- Allen E. (2019). Perceived discrimination and health: Paradigms and prospects. Sociology Compass, 13(8), e12720. 10.1111/soc4.12720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter A. B., Cisler J. M., McCauley J. L., Hernandez M. A., Muzzy W., Acierno R. (2011). Do incident and perpetrator characteristics of elder mistreatment differ by gender of the victim? Results from the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 23(1), 43–57. 10.1080/089465566.2011.534707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter A. B., Zajac K., Strachan M., Hernandez M. A., Kilpatrick D. G., Acierno R. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of elder abuse in South Carolina: The South Carolina elder abuse study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(15), 2947–2972. 10.1177/0886260510390959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtha M., Holm K. (2017). Who cares? Study on the challenges and needs of family carers in Europe. COFACE Families Europe. https://www.coface-eu.org/resources/publications/study-challenges-and-needs-of-family-carers-in-europe/

- Bowling A. (2004). Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 342–345. 10.1136/jech.2004.021204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Isham L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13-14), 2047–2049. 10.1111/jocn.15296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. (2018). 2016 Population by-census thematic report: Older persons. Hong Kong SAR Government, Census and Statistics Department. https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11201052016XXXXB0100.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). COVID-19 risks and vaccine information for older adults. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html

- Chang E. S., Kannoth S., Levy S., Wang S. Y., Lee J. E., Levy B. R. (2020). Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: A systematic review. PLoS One, 15(1), e0220857. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. S., Levy B. R. (2021). High prevalence of elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(11), 1152–1159. 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielowska M., Fuhr D. C. (2017). Intimate partner violence and mental ill health among global populations of Indigenous women: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 689–704. 10.1007/s00127-017-1375-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on the Status of Women Sixty-Fifth Session (2021). Women's full and effective participation and decision-making in public life, as well as the elimination of violence, for achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls. Agreed Conclusions. (E/CN.6/2021/L.3). https:undocs.org/en/E/CN.6/2021/L.3 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C., Livingston G. (2020). Elder abuse and dementia. In Phelan A. (Ed.), Advances in elder abuse research: International perspectives on aging (Vol. 24, pp.137-147). Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-030-25093-5_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J. (2006). A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: Confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging, 28(5), 582–598. 10.1177/0164027506289723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du P., Chen Y. (2021). Prevalence of elder abuse and victim-related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12889-021-11175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman A., Breckman R., Clark S., Gottesman E., Rachmuth L., Reiff M., Callahan J., Russell L. A., Curtis M., Solomon J., Lok D., Sirey J. A., Lachs M. S., Czaja S., Pillemer K., Rosen T. (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on elder mistreatment and response in New York City: Initial lessons. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(7), 690–699. 10.1177/0733464820924853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elovainio M., Hakulinen C., Pulkki-Raback L., Virtanen M., Josefsson K., Jokela M. (2017). Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality in isolated and lonely individuals: An analysis of data from the UK biobank cohort study. Lancet Public Health, 2(6), e260–e266. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)3-0075-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery C. R., Wu S., Eremina T., Yoon Y., Kim S., Yang H. (2015). Does informal social control deter child abuse? A comparative study of Koreans and Russians. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research Policy and Practice, 30(18), 3324–339. 10.1007/s42448-019-00017-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emery C. R., Wu S., Kim O., Pyun C., Chin W. W. (2017). Protective family informal social control of intimate partner violence in Beijing. Psychology of Violence, 7(4), 553–562. 10.1037/vio0000063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gencer N. (2020). Being elderly in COVID-19 process: evaluations on curfew for 65-year-old and over citizens and spiritual social work. Turkish Journal of Social Work Research, 4(1), 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Han S. D., Mosqueda L. (2020). Elder abuse in the COVID-19 era. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 68(7), 1386–1387. 10.1111/igs.16496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HelpAge. (2021). Confronting the shadow pandemic: COVID-19 and violence, abuse and neglect of older people. HelpAge International. https://www.helpage.org/silo/files/vancovid19violence-abuse-and-neglectbriefing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. S., Wong S. Y., Chiu M. M., Ho R. C. (2017). Global prevalence of elder abuse: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 27(2), 43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E. A., O'Connor R. C., Perry V. H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Silver R. C., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A. K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., … ,& Bullmore E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T. B., Baker M., Harris T., Stephenson D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors of mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Ghose B., Tang S. (2020). Effect of financial stress on self-reported health and quality of life among older adults in five developing countries: A cross-sectional analysis of WHO-SAGE study. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 288. 10.1186/s12877-020-01687-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasar K. S., Karaman E. (2021). Life in lockdown: Social isolation, loneliness and quality of life in the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Geriatric Nursing, 42(5), 1222–1229. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam H. Y., Lam T. S., Wong C. H., Lam W. H., Leung C. M. E., Au K. W. A., Lam C. K. Y., Lau T. W. W., Chan Y. W. D., Wong K. H., Chuang S. K. (2020). The epidemiology of COVID-19 cases and the successful containment strategy in Hong Kong: January to May 2020. International Journal of Infectious Disease, 98, 51–58. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann E. O., Leitsch S. A., Waite L. J. (2008). Elder abuse in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. Journal of Gerontology Series B, 63(4), S248–S254. 10.1093/geronb/63.4.S248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung G. T. Y., De Jong Gierveld J., Lam L. C. W. (2008). Validation of the Chinese translation of the 6-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in elderly Chinese. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(6), 1262–1272. 10.1017/S1041610208007552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University , & New York City Department for the Aging . (2011). Under the radar: New York State elder abuse prevalence study: Self-reported prevalence and documented case surveys final report. https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/under%20the%20radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf

- Lindert J., Luna J., Torres-Gonzales F., Barros H., Ioannidi-Kopolou E., Melchiorre M. G., Stankunas M., Macassa G., Soares J. F. J. (2013). Abuse and neglect of older persons in seven cities in seven countries in Europe: A cross-sectional community study. International Journal of Public Health, 58(1), 121–132. 10.1007/s00038-012-0388-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Hoffman J. M., West S. G., Sheets V. A. (2002). Comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makaroun L. K., Bachrach R. L., Rosland A. M. (2020). Elder abuse in the time of COVID-19: Increased risks for older adults and their caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(8), 876. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallapaty S. (2020). The coronavirus is most deadly if you are older and male: New data revealed the risks. Nature, 585(7823), 16–17. 10.1038/d41586-020-02483-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi C. M., Chen H., Hawkley L. C., Cacioppo J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miszkurka M., Steensma C., Phillips S. P. (2016). Correlates of partner and family violence among older Canadians: A life-course approach. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy, and Practice, 36(3), 45–53. 10.24095/hpcdp.36.3.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon K. A., Denize K. M., Talarico R., Fell D. B., Sobiesiak A., Heimerl M., Sampsel K. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and violence: Rising risks and decreasing urgent care-seeking for sexual assault and domestic violence survivors. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 20. 10.1186/s12916-020-01897-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. D., Uchino B. N., Wethington E. (2016). Loneliness and health in older adults: A mini-review and synthesis. Gerontology, 62(4), 443–449. 10.1159/000441651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J., Morgan A., Piquero A. R. (2020). COVID-19 and violent crime: A comparison of recorded offence rates and dynamic forecasts (ARIMA) for March 2020 in Queensland, Australia. Center for Open Science. 10.31219/osf.io/g4kh7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A. R., Riddell J. R., Bishopp S. A., Narvey C., Reid J. A., Piquero N. L. (2020). Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 601–635. 10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu L., Moyle W., Jones C., Todorovic M. (2019). The effectiveness of social robots for older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 37–51. 10.1093/geront/gny046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rina K., Maiti T., Panigrahi M., Patro B., Kar N., Padhy S. K. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on elder abuse. Journal of Geriatric Care and Research, 7(3), 103–107. https://www.academia.edu/43926068/Impact_of_COVID_19_pandemic_and_lockdown_on_elder_abuse [Google Scholar]

- Roberto K. A. (2016). The complexities of elder abuse. American Psychologist, 71(4), 302–311. 10.1037/a0040259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield M. J., Powers J. R., Loxton D. (2013). Mortality and disability outcomes of self-reported elder abuse: A 12-year prospective investigation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(5), 679–685. 10.1111/jgs.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. G. S., Nogueras D., van Woerden H. C., Kiparoglou V. (2021). Evaluation of the effectiveness of digital technology interventions to reduce loneliness in older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e24712. 10.2196/24712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A., Hamer M., McMunn A., Steptoe A. (2013). Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(2), 161–170. 10.1097/PSU.0b013e31827f09cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark L., Seff I. (2021). The role of social norms, violence against women, and measurement in the global commitment to end violence against children. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 27(1), 24–27. 10.1037/pac0000510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. (2021). The shadow pandemic: Violence against women during COVID-19. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violence-against-women-during-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 549–552. 10.1111/inm.12735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldegrave C. (2018). The impacts of discrimination and abuse on the health, well-being and loneliness of older people. Innovation in Aging, 2(Suppl 1), 337. 10.1093/geroni/igy023.1237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberger G. H., Goodman M. C., Mosqueda L., Schoen J., Nguyen A. L., Wilber K. H., Gassoumis Z. D., Nguyen C. P., Han S. D. (2020). Elder abuse characteristics based on calls to the National Center on elder abuse resource line. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(10), 1078–1087. 10.1177/0733464819865685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J. Y. H., Wai A. K. C., Wang M. P., Lee J. J., Li M., Wong C. K. H., Choi A. W. M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment: Income instability and parenting issues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1501. 10.3390/ijerph18041501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. Y. S., Zhang D., Sit R. W. S., Yip B. H. K., Chung R. Y., Wong C. K. M., Chan D. C. C., Sun W., Kwok K. O. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation. British Journal of General Practice, 70(700), e817–e824. 10.3399/bjgp20X713012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2016). Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252276/9789241511537-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Violence against women: Intimate partner and sexual violence against women. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329889/WHO-RHR-19.16-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). COVID-19 and violence against women: What the health sector/system can do. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331699/WHO-SRH-20.04-eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021a). Decade of healthy ageing 2020–2030. World Health Organization. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/final-decade-proposal/decade-proposal-final-apr2020-en.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b75ebc_25&download=true [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021b). Elder abuse. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021c). Global report on ageism. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021d). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- Yeung P., Cooper L., Dale M. (2015). Prevalence and associated factors of elder abuse in a community-dwelling population of Aotearoa New Zealand: A cross-sectional study. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 27(3), 29–43. 10.11157/anzswj-vol27iss3id4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yon Y., Mikton C. R., Gassoumis Z. D., Wilber K. H. (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e147–e156. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus R. M., Hairi N. N., Choo W. Y. (2017). Consequences of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of observational studies. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20(2), 197–213. 10.1177/1524838017692798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]