This cohort study assesses whether multimorbidity is associated with long-term survival in older patients with emergency general surgery conditions.

Key Points

Question

Is complex multimorbidity (the co-occurrence of chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes) associated with long-term survival after admission for emergency general surgery conditions in older patients?

Findings

This cohort study of 1960 community-dwelling patients aged 65 years or older who were admitted with emergency general surgery conditions found that complex multimorbidity, particularly the presence of functional limitations, was associated with an increased risk of death.

Meaning

Findings of this study suggest that complex multimorbidity, particularly functional limitations, is rarely considered in risk stratification paradigms for older patients with emergency general surgical conditions but is an important risk factor for long-term survival.

Abstract

Importance

Although nearly 1 million older patients are admitted for emergency general surgery (EGS) conditions yearly, long-term survival after these acute diseases is not well characterized. Many older patients with EGS conditions have preexisting complex multimorbidity defined as the co-occurrence of at least 2 of 3 key domains: chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes. The hypothesis was that specific multimorbidity domain combinations are associated with differential long-term mortality after patient admission with EGS conditions.

Objective

To examine multimorbidity domain combinations associated with increased long-term mortality after patient admission with EGS conditions.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study included community-dwelling participants aged 65 years and older from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey with linked Medicare data (January 1992 through December 2013) and admissions for diagnoses consistent with EGS conditions. Surveys on health and function from the year before EGS conditions were used to extract the 3 domains: chronic conditions, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes. The number of domains present were summed to calculate a categorical rank: no multimorbidity (0 or 1), multimorbidity 2 (2 of the 3 domains present), and multimorbidity 3 (all 3 domains present). Whether operative treatment was provided during the admission was also identified. Data were cleaned and analyzed between January 16, 2020, and April 29, 2021.

Exposures

Mutually exclusive multimorbidity domain combinations (functional limitations and geriatric syndromes; functional limitations and chronic conditions; chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes; or functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and chronic conditions).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Time to death (up to 3 years from EGS conditions admission) in patients with multimorbidity combinations was analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model and compared with those without multimorbidity; hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs are presented. Models were adjusted for age, sex, and operative treatment.

Results

Of 1960 patients (median [IQR] age, 79 [73-85] years; 1166 [59.5%] women), 383 (19.5%) had no multimorbidity, 829 (42.3%) had 2 multimorbidity domains, and 748 (38.2%) had all 3 domains present. A total of 376 (19.2%) were known to have died in the follow-up period, with a median (IQR) follow-up of 377 (138-621) days. Patients with chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes had a mortality risk similar to those without multimorbidity. However, all domain combinations with functional limitations were associated with significantly increased risk of death: functional limitations and chronic conditions (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.03-3.23); functional limitations and geriatric syndromes (HR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.37-6.18); and functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and chronic conditions (HR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.49-2.89).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this study suggest that a patient’s baseline complex multimorbidity level efficiently identifies risk stratification groups for long-term survival. Functional limitations are rarely considered in risk stratification paradigms for older patients with EGS conditions compared with chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes. However, functional limitations may be the most important risk factor for long-term survival.

Introduction

Of nearly 2 million adults admitted to the hospital for emergency general surgery (EGS) conditions annually in the US, almost half are older adults. This disproportionate population of older patients is often at high risk for complications and mortality because of preexisting medical disease and health vulnerability (ie, the consequences of aging, such as development of functional limitations or other nonmedical conditions, including vision and hearing loss, incontinence, and cognitive loss).1,2 The acute care for EGS conditions, broadly consisting of acute abdominal or surgical soft tissue catastrophes and infections, cost more than $28 billion in 2010, and approximately 30% are treated operatively.3,4 The impact and cost of EGS conditions are expected to increase to $41 billion by 2060 and thus are an important area of population health research.4

For the older adult with EGS conditions, subsequent survival and quality of life are uncertain. Emergency general surgery conditions can catalyze a loss of independence or accelerated health decline with subsequent mortality.5 Chronological age is a known risk factor for mortality in patients with EGS conditions, but it is unknown whether chronological age is a proxy for complex multimorbidity, here defined as the co-occurrence of chronic conditions or diseases, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes (ie, aging syndromes that are not discrete diseases, such as incontinence, hearing and vision difficulties, and frequent falls).6 Complex multimorbidity is known to be associated with poor health outcomes in large populations of older patients7,8,9 but has yet to be described as a risk factor for mortality in older patients with EGS conditions. If preexisting complex multimorbidity is a useful risk stratification measure in patients with EGS conditions, clinicians might be able to use this simple scale to discuss long-term outcomes.

We examined the association between complex multimorbidity and long-term mortality after EGS admission for older patients from 3 perspectives: (1) using a summary measure of complex multimorbidity, (2) differentiating combinations of the 3 multimorbidity domains, and (3) examining whether the level of multimorbidity has varying implications for different EGS disease types. We hypothesized that the domains of functional limitations and geriatric syndromes will help estimate long-term mortality beyond inclusion of chronic conditions and that complex multimorbidity would have differing implications for EGS disease subtypes.

Methods

Data Source and Inclusion Criteria

In this cohort study, we used the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) linked with Medicare claims from January 1992 through December 2013. The MCBS provides survey-collected participant data on health, functional status, and other demographic and household composition data (data on race and ethnicity were not collected because those demographics were not included in the study design or models). Participants are enrolled in the MCBS for up to 4 years and complete an annual in-person health survey, which includes a variety of questions on health, disease, and function. Claims data have been linked to these individuals per year of inclusion and provide a comprehensive look at their health care use and outcomes during their time participating in the MCBS. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey data underwent a major format change in 2014, which was followed by a gap in data release for that year; our analysis therefore ends with 2013 because of the noncontinuity of data. We identified patients who had a hospitalization for an emergency general surgery condition during the time frame using a framework described by Smith et al.5 We limited inclusion to patients aged 65 years or older who were community dwelling at the time of EGS admission and had a health survey before the EGS admission. To ensure that complete claims history was captured, we also limited analysis to participants who were enrolled in a Medicare fee-for-service model. This study was deemed not human participant research by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board; therefore, study review and the requirement for informed consent were waived. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.10,11

Outcome of Interest

The primary outcome of interest in this study was survival after admission for an EGS condition. The linked Medicare data set provides the date of hospitalizations and date of death, if death occurred during study enrollment. We evaluated death up to 3 years after hospital admission, and for those who did not die (or did not have this information available), we applied a censoring date of the last day of their final year of MCBS participation (typically December 31 of the participant’s last year of survey enrollment).

Covariates

Covariates of interest in this study were age at admission, sex (male or female sex as provided in the data set), and whether a surgical procedure was performed because not all patients admitted for EGS conditions underwent subsequent surgical procedures. In addition, we calculated the measure of complex multimorbidity using a previously published framework.6

The complex multimorbidity framework is a validated multicategorical scale ranging from a level of no multimorbidity (multimorbidity 0) to severe multimorbidity (multimorbidity 3). This multimorbidity variable is a summed composite of functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and chronic conditions. Complex multimorbidity level has been associated with a variety of health outcomes, including mortality, decline in health, and increased health care use,6 but has not previously been described for estimation of long-term survival in patients admitted for surgery.

Each domain component of multimorbidity is derived from a participant’s self-reported health survey. The functional limitation component was defined as present for any individual who had 5 or more of the following: difficulty walking, stooping, lifting, reaching, writing, bathing, getting in and out of a chair, dressing, eating, using the toilet, walking, managing money, doing heavy housework, doing light housework, preparing meals, shopping, or using the telephone. A patient was classified as having a geriatric syndrome if they reported vision trouble, hearing trouble, feeling sad or depressed, lost urine, difficulty eating solid foods, memory loss, problems with decision-making, or trouble concentrating. If any of the following diseases was reported, an individual was said to have chronic conditions: high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, heart failure, valve issues, other heart conditions, heart rhythm problems, stroke, diabetes, emphysema, arthritis, or cancer.

For this study, patients with no complex multimorbidity had multimorbidity levels of 0 or 1. We created dummy variables for each domain as well as unique combinations of domains.

Statistical Analysis

Data were cleaned and analyzed between January 16, 2020, and April 29, 2021. In addition to descriptive statistics, we used Cox proportional hazards models for time-to-event analyses with Kaplan-Meier curves to evaluate the association between complex multimorbidity and long-term survival. The first model and Kaplan-Meier curves showed the association between increasing multimorbidity and survival after admission for EGS conditions. We then included the variables for the combinations of multimorbidity components (functional limitations and geriatric syndromes; functional limitations and chronic conditions; chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes; or functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and chronic conditions) to evaluate the association of the specific combinations compared with patients with multimorbidity levels of 0 or 1. We first stratified by EGS disease type and then, within each EGS type, stratified the Kaplan-Meier and adjusted Cox proportional hazards model by multimorbidity level. Emergency general surgery disease categories included biliopancreatic; colon; peptic ulcer and gastrointestinal bleeding; small bowel, appendix, or other disease; and soft tissue infections. Cox proportional hazards models used α = .05, which was the threshold for statistical significance, and 95% CIs with adjustment for surgery, age, and sex. Data management and analysis were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) and R software, version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study Population

We identified 89 434 individuals from the MCBS with at least 1 health survey. We limited the sample to those who had an EGS condition (3781), whose health survey occurred before their hospitalization (2725), who were older than age 64 years (2419), who were community dwelling (2142), and who were enrolled in Medicare in a fee-for-service model, leaving a total of 1960 patients with EGS conditions (eFigure in the Supplement). The median (IQR) patient age was 79 (73-85) years, and 1166 (59.5%) were women and 794 (40.5) were men (Table 1). Of these, 717 (36.6%) underwent surgery for their EGS disease. The most common disease category was colon (715 [36.5%]), followed by biliopancreatic (483 [24.6%]); small bowel, appendix, or other disease (425 [21.7%]); peptic ulcer and gastrointestinal bleeding (315 [16.1%]); and soft tissue infections (22 [1.1%]). Because of sample size limitations, we excluded those with soft tissue infections from the subgroup analysis. A total of 376 patients (19.2%) died in the 3 years after admission for EGS conditions, with a median (IQR) follow-up time of 377 (138-621) days, or 12.6 (4.6-20.7) months.

Table 1. Description of the Study Population of Older Adults With Emergency General Surgery Conditions.

| Patients, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 1960) | Alive or censored (n = 1584) | Died (n = 376) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 79 (73-85) | 79 (73-84) | 82 (77-87) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1166 (59.5) | 979 (61.8) | 187 (49.7) |

| Male | 794 (40.5) | 605 (38.2) | 189 (50.3) |

| Multimorbidity | |||

| 0 or 1 | 383 (19.5) | 336 (21.2) | 47 (12.5) |

| 2 | 829 (42.3) | 697 (44.0) | 132 (35.1) |

| 3 | 748 (38.2) | 551 (34.8) | 197 (52.4) |

| Underwent surgery | |||

| Yes | 717 (36.6) | 616 (38.9) | 101 (26.9) |

| No | 1243 (63.4) | 968 (61.1) | 275 (73.1) |

| Patients with EGS conditions included in subgroup analysis, No. | 1938 | 1568 | 370 |

| EGS categorya | |||

| Biliopancreatic | 483 (24.9) | 429 (27.4) | 54 (14.6) |

| Colon | 715 (36.9) | 572 (36.5) | 143 (38.6) |

| Peptic ulcer and GI bleeding | 315 (16.3) | 234 (14.9) | 81 (21.9) |

| Small bowel, appendix, or other disease | 425 (21.9) | 333 (21.2) | 92 (24.9) |

| Follow-up time, median (IQR) | |||

| Days | 377 (138-621) | 448 (212-664) | 87 (32-300) |

| Months | 12.6 (4.6-20.7) | 14.9 (7.1-22.1) | 2.9 (1.1-10.0) |

Abbreviations: EGS, emergency general surgery; GI, gastrointestinal.

Soft tissue infections (22) were excluded from subgroup analysis because of the small sample size.

A total of 383 patients (19.5%) were categorized as having no multimorbidity (multimorbidity 0 or 1); only 24 (1.2%) had no multimorbidity domains present (multimorbidity 0). A total of 829 patients (42.3%) were classified as having multimorbidity 2, and the most common combination of domains was geriatric syndromes and chronic conditions (741 [89.4%]), followed by functional limitations and chronic conditions (78 [9.4%]) and functional limitations and geriatric syndromes (21 [2.5%]). The remaining 748 (38.2%) patients had all 3 multimorbidity domains and were classified as having multimorbidity 3.

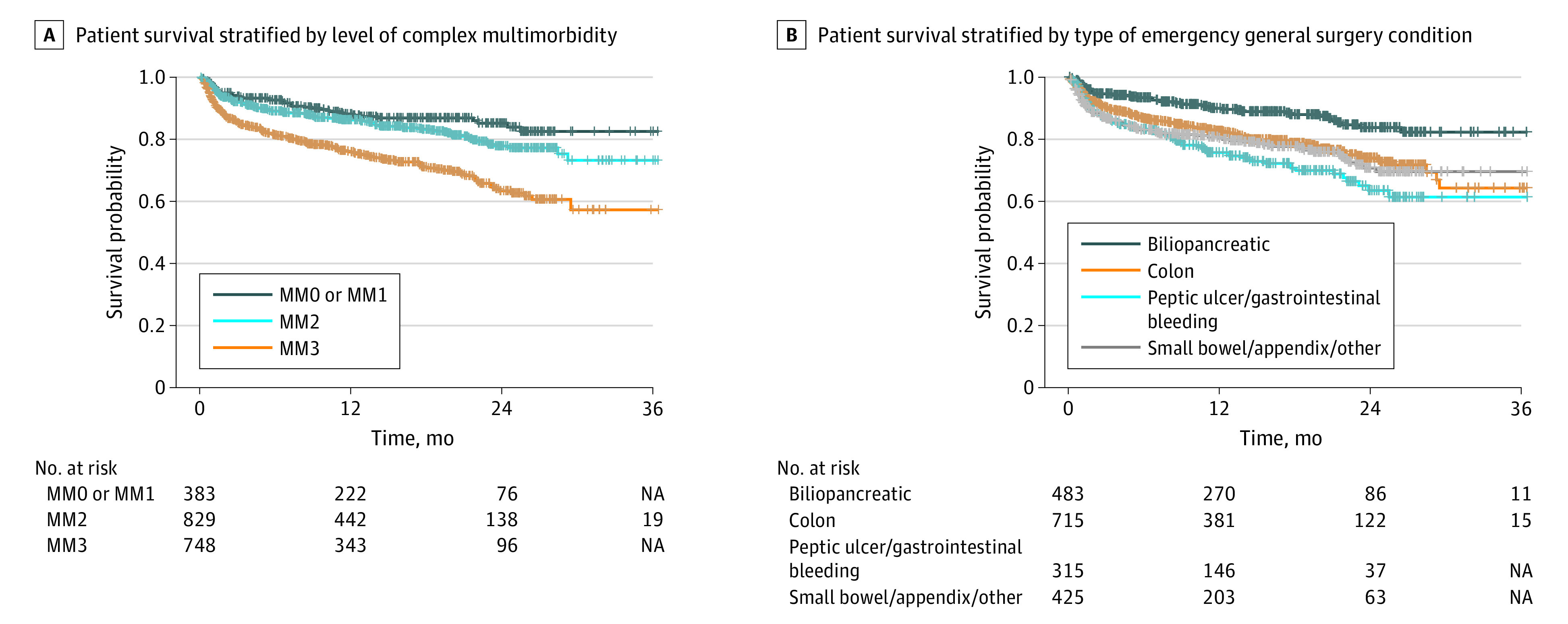

Survival by Level of Multimorbidity

Survival for the entire cohort by multimorbidity level is presented in Figure 1A. Individuals with a greater level of complex multimorbidity had substantially worse survival after admission for EGS conditions. This survival was confirmed via Cox proportional hazards modeling (Table 2), in which a higher hazard ratio (HR) compared with that of multimorbidity 0 or 1 was associated with an increased risk of death in patients having multimorbidity 2 (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.90-1.75) and those having multimorbidity 3 (HR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.48-2.87) (Table 2). In this model, having surgery for an EGS condition was associated with improved long-term survival (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.56-0.90).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Patient Survival of Entire Cohort.

Groups with 11 or fewer patients are censored within the risk table. MM indicates multimorbidity; NA, not applicable.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Models.

| Model | HR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Model 1: MM levels | |

| Undergoing surgery | 0.71 (0.56-0.90) |

| Age | 1.05 (1.03-1.06) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 0.53 (0.43-0.66) |

| Male | 1 [Reference] |

| MM level | |

| 0 or 1 | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 (any 2 domains) | 1.25 (0.90-1.75) |

| 3 | 2.06 (1.48-2.87) |

| Model 2: MM domain combinations | |

| Undergoing surgery | 0.71 (0.56-0.90) |

| Age | 1.05 (1.03-1.06) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 0.53 (0.43-0.65) |

| Male | 1 [Reference] |

| Domain combination | |

| No MM (MM0 or 1) | 1 [Reference] |

| MM2: GS and CC | 1.15 (0.82-1.62) |

| MM2: FL and CC | 1.83 (1.03-3.23) |

| MM2: FL and GS | 2.91 (1.37-6.18) |

| MM3: FL, GS, and CC | 2.08 (1.49-2.89) |

Abbreviations: CC, chronic conditions; FL, functional limitations; GS, geriatric syndromes; HR, hazard ratio; MM, multimorbidity.

Hazard ratios and 95% CIs from a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the association between multimorbidity and mortality, controlling for sex, procedure, and multimorbidity.

Survival by Multimorbidity Domain Combinations

When evaluating specific combinations of domains within multimorbidity 2 (Table 2), we observed that compared with patients with multimorbidity 0 or 1, the addition of geriatric syndromes to chronic conditions did not significantly change the risk of mortality (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.82-1.62). However, all domain combinations with functional limitations were associated with significantly increased risk of death: functional limitations and chronic conditions (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.03-3.23); functional limitations and geriatric syndromes (HR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.37-6.18); and functional limitations, geriatric syndromes, and chronic conditions (HR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.49-2.89) (Table 2). Again, surgery for an EGS condition was associated with improved long-term survival (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.56-0.90).

Survival by Disease Type

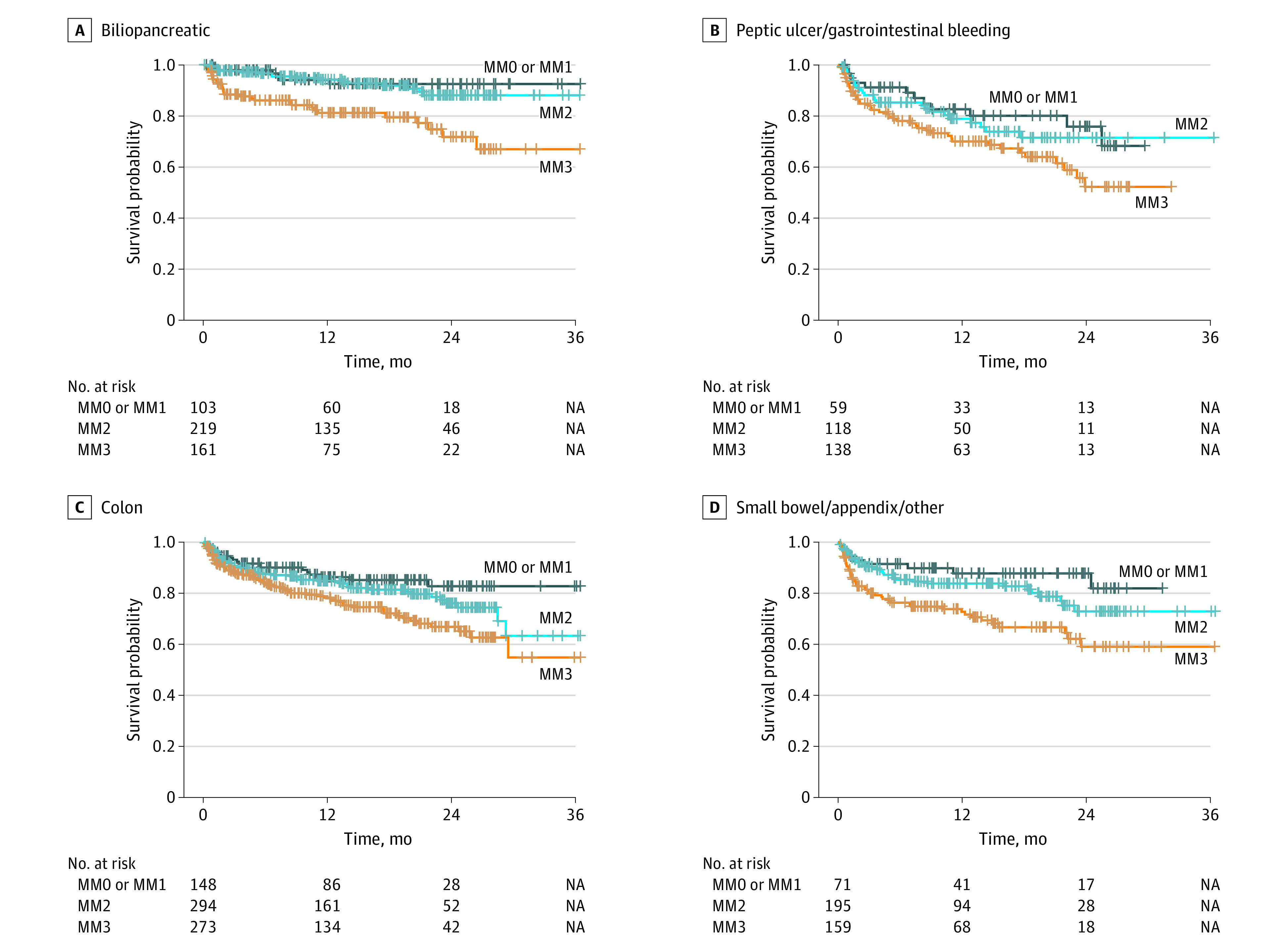

Long-term survival also significantly differed by disease type. Patients with biliopancreatic disease seemed to have better overall survival than patients with other EGS disease types (Figure 1B), based on visual inspection of unadjusted survival curves. By EGS disease subgroups, the level of complex multimorbidity had varying implications for survival depending on the disease (Figure 2). For most disease processes, there was a dose-response association whereby survival worsened with each complex multimorbidity level. For patients with biliopancreatic disease, only the patients with multimorbidity 3 had notably worse outcomes; in this subgroup, patients with multimorbidity 2 had outcomes similar to patients with no multimorbidity.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Patient Survival Stratified by Disease Subgroup.

Groups with 11 or fewer patients are censored within the risk table. MM indicates multimorbidity; NA, not applicable.

Cox proportional hazards modeling by disease subgroups (Table 3) shows the association between multimorbidity level and long-term survival after adjustment for surgical treatment, age, and sex. In every case, the presence of severe multimorbidity (multimorbidity 3) was associated with increased risk for death; HRs for multimorbidity 3, compared with multimorbidity 0 or 1, ranged from 1.83 (95% CI, 1.09-3.08) in colon diseases to 2.91 (95%CI, 1.18-7.19) for biliopancreatic diseases. After adjustment for other factors, multimorbidity 2 was not significantly different. Emergency general surgery disease subgroup sample size limited our ability to examine the implications of multimorbidity domain combinations for survival. Surgical treatment of the disease was associated with a lower risk of death in patients with biliopancreatic disease (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.33-0.97), a higher risk of death for patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastrointestinal bleeding (HR, 2.53; 95% CI, 1.20-5.32), and no change in the risk of death in those with colon disease and small bowel disease, appendix, and other disease.

Table 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Modeling by Disease Subgroups.

| Term | Disease subgroup, HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biliopancreatic (n = 483) | Colon (n = 715) | Peptic ulcer and GI bleeding (n = 315) | Small bowel, appendix, and other (n = 425) | |

| Surgery | 0.56 (0.33-0.97) | 1.14 (0.78-1.67) | 2.53 (1.20-5.32) | 0.64 (0.40-1.02) |

| Age ≥65 | 1.07 (1.03-1.12) | 1.06 (1.03-1.08) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 0.47 (0.27-0.84) | 0.57 (0.41-0.80) | 0.39 (0.25-0.63) | 0.58 (0.38-0.88) |

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| MM level | ||||

| 0 or 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2 | 1.03 (0.40-2.61) | 1.41 (0.85-2.37) | 1.16 (0.58-2.33) | 1.42 (0.68-2.97) |

| 3 | 2.91 (1.18-7.19) | 1.83 (1.09-3.08) | 1.97 (1.01-3.82) | 2.31 (1.11-4.83) |

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

This longitudinal study of patients with EGS conditions shows that a patient’s baseline complex multimorbidity level efficiently identifies risk stratification groups for long-term survival. Several findings from this study are worth noting. In this cohort of community-dwelling patients, approximately one-quarter of patients with the highest possible level of multimorbidity, or multimorbidity 3, died approximately 1 year after admission, and they continued to have higher rates of death compared with patients with lower multimorbidity levels during the 3-year time frame. This pattern held for all EGS disease types. However, patient survival differed between EGS disease types: patients with biliopancreatic disease had generally better survival than other EGS disease types, and patients with peptic ulcer and gastrointestinal bleeding had the lowest overall survival. Among multimorbidity domains, the presence of functional limitations was associated with poor survival. The present study highlights, however, that most of these patients do survive, especially if their level of complex multimorbidity is low.

Although EGS conditions are acute and often unexpected, long-term consequences after admission are not unexpected. Many studies on EGS outcomes use hospital discharge or 30-day survival,12,13,14 but EGS may be a breakpoint that leads to persistent decline manifesting over a longer time period than 30 days. A study by Smith et al5 found that, among community-dwelling patients who survived to hospital discharge after admission for EGS disease, nearly 1 in 4 either died or were no longer able to live independently. Another study of patients who underwent major emergency abdominal surgery supported these findings. Of this group of patients aged 65 years or older, 34% had died in year 1; in the subgroup of patients aged 80 years or older, 50% had died during year 1. Long-term estimation tools are needed to help with goal setting and long-term goals of care planning for this group with a high risk of mortality after admission for EGS conditions.

Consistent with previous work, which has shown that multimorbidity level is associated with poor health, major health decline, high health expenditures, and mortality, the present study found that, for patients who are admitted with emergency surgical disease, a high multimorbidity level is associated with a high risk of long-term poor outcomes.15 Complex multimorbidity differs from other measures of aging-related health vulnerability because it places value on functional limitations as well as geriatric syndromes, which do not fall into traditional disease categories. Level of dependence, functional status, vision or hearing impairment, falls, and urinary incontinence are often not measured as risk factors but are clinically relevant when evaluating a patient’s fitness for surgery. This study suggests that functional limitations are potentially as important or possibly even more important for long-term estimation of survival than the presence of comorbidities alone. In this cohort, functional limitations did not occur in isolation but almost always presented with at least 1 of the other multimorbidity domains. Development of functional limitations may be a proxy for a coup de grâce of the aging process, the culmination of accumulation of health vulnerabilities that subsequently portends a poor prognosis.

Modern studies on older patients with EGS conditions largely evaluate measures of frailty rather than complex multimorbidity.16,17,18 Frailty is defined as aging-related vulnerability to adverse health outcomes and is known to be associated with poor outcomes after EGS.19 Frailty assessment is currently recommended for risk stratification before general surgery in older patients.19 Unfortunately, applied frailty measures validated in large populations or in elective surgical populations are imperfect for use in EGS because patients are often too ill to have prospectively applied frailty measurements. Postoperatively applied frailty measures rely heavily on the presence of multiple chronic conditions or diseases.16,17,20,21 Oft-used measures for risk adjustment include the Charlson Comorbidity Index, the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, and the modified Frailty Index, which are mostly summary measures of chronic disease.16,17,20,21,22 In the present analysis, risk from the presence of functional limitations appeared to have larger consequences for long-term mortality than the presence of chronic conditions, suggesting that use of accumulated comorbidity-based indices may be omitting an important risk category. This complex multimorbidity level in the EGS conditions population may have valuable clinical applicability compared with existing comorbidity-based measures and places value on the patient’s clinical function, which is not currently emphasized in preoperative assessments. Future study is needed on whether specific functional tasks or the accumulation of functional deficits has the most prognostic value.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The longitudinal data showed that patients with complex multimorbidity in 3 domains have higher rates of mortality compared with patients with lower levels of multimorbidity, and this risk persists over time. However, the most important limitation of the study is that it remains unknown whether long-term risk can be attributed to severe complex multimorbidity alone or whether EGS conditions contribute to an accelerated decline in patients with a high risk of mortality. However, we believe that the data support the concept that the preexisting level of multimorbidity can be used for estimation of long-term outcomes and risk stratification in this patient population and in patients who develop EGS conditions.

Another limitation of this study is the use of self-reported surveys. There may be inaccurate reporting of some conditions related to patient understanding of their own diagnoses. However, previous studies have suggested that self-reported survey data perform well for estimation.23 For example, self-reported health data from the MCBS have also been used in validated frailty estimation models, which outperformed a claims-based comorbidity index for long-term mortality in a general geriatric population, suggesting that self-reported survey data are valuable for use in longitudinal analysis of outcomes and modeling.24,25

Another key limitation is that the data span from 1992 to 2013; disease patterns, surgical decision-making, and treatments have changed with the widespread use of laparoscopy, percutaneous treatment of infections, and medical treatment of ulcer disease, to name a few advances. However, the risk of death from EGS conditions procedures, such as major abdominal surgeries, in this patient population has not changed significantly since that time period, and the mortality rates that we observed in this cohort align with mortality rates reported in more recent literature,4,5,17,26 which suggests that our historical cohort remains relevant today.

Another consideration is that it is unknown whether the findings of the present study are unique to patients with EGS conditions. In a general population of older US adults, a higher multimorbidity level is known to be associated with mortality and increased health care use, but the specific implications of functional limitations have not been assessed in those cohorts.7,8 Future studies need to explore functional limitations and long-term outcomes in a variety of populations, with particular emphasis on surgical cohorts to investigate whether surgery and functional limitations are a particularly risky combination.

In addition, population-based surveys, such as the MCBS, have a limited number of participants, and the sample size precluded additional subgroup and domain analysis. Despite these limitations, we believe that our study captured reliable survival data for up to 3 years.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of community-dwelling patients who had inpatient admissions for EGS conditions, 19.2% of patients died over the maximum follow-up period of 3 years. Provision of surgery was associated with improved long-term survival in patients admitted for biliopancreatic disease. The long-term risk of mortality was significantly higher in patients with functional limitations or severe complex multimorbidity. The complex multimorbidity framework provides a simple ranking system that has important implications for patients who develop EGS diseases and can be used for counseling on long-term outcomes. Of note, the presence of functional limitations appears to be an important breaking point that portends a higher risk of mortality. Future work must continue to examine not only survival but also the long-term quality of life for survivors of EGS conditions.

eFigure. Flow Diagram.

References

- 1.Shah AA, Haider AH, Zogg CK, et al. National estimates of predictors of outcomes for emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):482-490. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt J, McCormack C, Tay HS, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity and its association with outcomes in older emergency general surgical patients: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010126. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shafi S, Aboutanos MB, Agarwal S Jr, et al. ; AAST Committee on Severity Assessment and Patient Outcomes . Emergency general surgery: definition and estimated burden of disease. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1092-1097. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827e1bc7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S. The financial burden of emergency general surgery: national estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(3):444-448. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JW, Knight Davis J, Quatman-Yates CC, et al. Loss of community-dwelling status among survivors of high-acuity emergency general surgery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(11):2289-2297. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koroukian SM, Warner DF, Owusu C, Given CW. Multimorbidity redefined: prospective health outcomes and the cumulative effect of co-occurring conditions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E55. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, et al. Multimorbidity: constellations of conditions across subgroups of midlife and older individuals, and related Medicare expenditures. J Comorb. 2017;7(1):33-43. doi: 10.15256/joc.2017.7.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Sun J, et al. The influence of multimorbidity on leading causes of death in older adults with cognitive impairment. J Aging Health. 2019;31(6):1025-1042. doi: 10.1177/0898264317751946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koroukian SM, Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Klika AK, Higuera-Rueda CA, Barsoum WK. Older adults undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty: chronicling changes in their multimorbidity profile in the last two decades. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):976-982. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaferi AA, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):577-578. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, et al. Comparison of 30-day outcomes after emergency general surgery procedures: potential for targeted improvement. Surgery. 2010;148(2):217-238. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng S, Van Walraven C, Lalu M, Moloo H, Musselman R, McIsaac DI. Protocol for the derivation and external validation of a 30-day mortality risk prediction model for older patients having emergency general surgery (PAUSE score—probability of mortality associated with urgent/emergent general surgery in older patients score). BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e034060. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merani S, Payne J, Padwal RS, Hudson D, Widder SL, Khadaroo RG. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and complications in very elderly patients undergoing emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiltz NK, Warner DF, Sun J, et al. Identifying specific combinations of multimorbidity that contribute to health care resource utilization: an analytic approach. Med Care. 2017;55(3):276-284. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy PB, Savage SA, Zarzaur BL. Impact of patient frailty on morbidity and mortality after common emergency general surgery operations. J Surg Res. 2020;247:95-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehlmann CA, Patel D, McCallum J, Perry JJ, Eagles D. Association between mortality and frailty in emergency general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48(1):141-151. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01578-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castillo-Angeles M, Cooper Z, Jarman MP, Sturgeon D, Salim A, Havens JM. Association of frailty with morbidity and mortality in emergency general surgery by procedural risk level. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):68-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko FC. Preoperative frailty evaluation: a promising risk-stratification tool in older adults undergoing general surgery. Clin Ther. 2019;41(3):387-399. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramaniam S, Aalberg JJ, Soriano RP, Divino CM. New 5-factor modified frailty index using American College of Surgeons NSQIP data. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(2):173-181.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farhat JS, Velanovich V, Falvo AJ, et al. Are the frail destined to fail? Frailty index as predictor of surgical morbidity and mortality in the elderly. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1526-1530. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182542fab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Havens JM, Olufajo OA, Cooper ZR, Haider AH, Shah AA, Salim A. Defining rates and risk factors for readmissions following emergency general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(4):330-336. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferraro KF, Farmer MM. Utility of health data from social surveys: is there a gold standard for measuring morbidity? Am Sociol Rev. 1999;64(2):303-315. doi: 10.2307/2657534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DH. Measuring frailty in health care databases for clinical care and research. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2020;24(2):62-74. doi: 10.4235/agmr.20.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Lipsitz LA, Rockwood K, Avorn J. Measuring frailty in Medicare data: development and validation of a claims-based frailty index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(7):980-987. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, Arumugam D, Crystal JS. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: a 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample—2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):202-208. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Diagram.