Abstract

Objective

Assess the suitability of clinical vignettes in benchmarking the performance of online symptom checkers (OSCs).

Design

Observational study using a publicly available free OSC.

Participants

Healthily OSC, which provided consultations in English, was used to record consultation outcomes from two lay and four expert inputters using 139 standardised patient vignettes. Each vignette included three diagnostic solutions and a triage recommendation in one of three categories of triage urgency. A panel of three independent general practitioners interpreted the vignettes to arrive at an alternative set of diagnostic and triage solutions. Both sets of diagnostic and triage solutions were consolidated to arrive at a final consolidated version for benchmarking.

Main outcome measures

Six inputters simulated 834 standardised patient evaluations using Healthily OSC and recorded outputs (triage solution, signposting, and whether the correct diagnostic solution appeared first or within the first three differentials). We estimated Cohen’s kappa to assess how interpretations by different inputters could lead to divergent OSC output even when using the same vignette or when compared with a separate panel of physicians.

Results

There was moderate agreement on triage recommendation (kappa=0.48), and substantial agreement on consultation outcomes between all inputters (kappa=0.73). OSC performance improved significantly from baseline when compared against the final consolidated diagnostic and triage solution (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Clinical vignettes are inherently limited in their utility to benchmark the diagnostic accuracy or triage safety of OSC. Real-world evidence studies involving real patients are recommended to benchmark the performance of OSC against a panel of physicians.

Keywords: public health, health policy, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A standardised set of 139 independently created vignettes covering 18 subcategories of clinical care was used to benchmark the performance of a popular online symptom checker (OSC) using 834 unique patient simulations.

An alternative and a final consolidated set of diagnostic accuracy and triage solutions for each vignette was derived using general practitioner roundtables and single-blinded testing.

We developed an accuracy matrix to monitor OSC outputs following each unique consultation with the online tool.

We used inter-rater reliability testing to investigate the agreement between different inputters and physicians when using the same vignette and/or OSC.

Study limitations include the use of a small sample of vignettes, and only one OSC as opposed to a variety of popular online consultation tools.

Introduction

In the USA, over one-third of adults self-diagnose their conditions using the internet, including queries about urgent (ie, chest pain) and non-urgent (ie, headache) symptoms.1 2 The main issue with self-diagnosing using websites such as Google and Yahoo is that user may get confusing or inaccurate information, and in the case of urgent symptoms, the user may not appreciate the need to seek emergency care.3 In recent years, various online symptom checkers (OSCs) based on algorithms or artificial intelligence (AI) have emerged to fill this gap.4

OSCs are calculators that ask users to input details about their symptoms of sickness, along with personal information such as gender and age. Using algorithms or AI, the symptom checkers propose a range of conditions that fit the symptoms the user experiences. Developers promote these digital tools as a way of saving time for patients, reducing anxiety and giving patients the opportunity to take control of their own health.5–7 The diagnostic function of OSC is aimed at educating users on the range of possible conditions that may fit their symptoms. Further to presenting a condition outcome and giving the users a triage recommendation that prioritises their health needs, the triage function of OSC guides users on whether they should self-care for the condition they are describing or whether they should seek professional healthcare support.3 This added functionality could vastly enhance the usefulness of OSC by alerting people about when they need to seek emergency support or seek non-emergency care for common or self-limiting conditions.8

Babylon has claimed that their OSC performed better than the average doctor on a subsection of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) examination.9 This claim has been supported by an internal evaluation study,10 but the findings were later considered uncertain due to methodological concerns.11 12 Misdiagnosis of patients with life-threatening conditions could worsen their health, especially if they are not told to seek care when they should, and this could result in an increased risk of preventable morbidity and mortality. Despite this, there has been little evidence in previous literature to suggest if OSCs are harmful to patients.13 14 However, OSCs that have high false-negative rates may run similar risks if used by patients with high-risk disease such as cardiac ischaemia, pulmonary embolism or meningitis.6 With this in mind, it is extremely important that there are guidelines on robust evaluation of OSCs regarding patient safety, efficacy, effectiveness and cost.15

Very little research has been done on the performance of symptom checkers for actual patients.16–21 Equally, there is a limited number of studies that attempted to benchmark the performance of different OSCs using clinical vignettes.22–28 A recent study compared the breadth of condition coverage, accuracy of suggested conditions and appropriateness of urgency advice of eight popular OSCs,26 and showed that the best performing OSCs have a high level of urgency advice accuracy which is close to that of general practitioners (GPs) and are close to GP performance in providing the correct condition in their top three condition suggestions in OSC.26 However, it remains uncertain if clinical vignettes are ideal to investigate the accuracy and safety of OSC generally. To address this gap in knowledge, we worked in collaboration with RCGP to develop a methodology to determine if clinical vignettes were a suitable tool that can be used to benchmark the performance of different OSCs.

The primary aim of this study was to assess the suitability of vignettes in benchmarking the performance of OSCs. Our approach included providing the vignettes to an independent panel of single-blinded physicians to arrive at an alternative set of diagnostic and triage solutions. The secondary aim was to benchmark the safety of a popular OSC (Healthily) by measuring the extent that it provided the correct diagnosis and triage solutions to a standardised set of vignettes as defined by a panel of physicians.

Methods

Our approach included the creation of an independent series of vignettes from RCGP. Each vignette was provided with three diagnostic solutions (S1–S3) and a triage (T) recommendation. Because RCGP created the vignettes from ‘the condition in mind’, we sought to arrive at an alternative set of diagnostic and triage solutions by inviting an independent panel of single-blinded GPs to propose their own solutions based on the vignette script alone (as no such resource currently exists). This resulted in the creation of two iterative ‘standardised’ sets of diagnostic and triage solutions that were used to benchmark the performance of Healthily OSC using a range of lay and expert inputters.

Vignette creation

A roundtable of experienced GPs affiliated to the RCGP supported the development of 139 clinical vignettes relevant to common self-limiting conditions, general practice and urgent care (table 1). Most of the clinical vignettes described new presentations by adults (18–65 years) but assumed that none of the patients were pregnant or had any prior or existing long-term conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, terminal illness or other comorbidities. Each vignette was created with a list of three reasonable condition outcomes (diagnostic solutions) and an appropriate triage. The 139 vignettes including their diagnostic and triage solutions whose provenance is the RCGP are referred to as the ‘original’ set.

Table 1.

Triage recommendations for 139 vignettes across 18 subcategories of clinical care

| Triage recommendation |

Self-care | Seek primary care |

Seek urgent care |

Total | |||

| Self-limiting | In 14 days | In 48 hours | In 12 hours | Attend emergency | Call ambulance | ||

| Cardiology | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| Dentist | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Emergent care | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| ENT |

2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| GUM |

2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Haematology | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Immunology | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Infection | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Mental health | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| MSK | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Renal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Neurology | 0 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| Oncology | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Eye | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Respiratory | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| Rheumatoid | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Surgical | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| Women’s health | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 22 | 29 | 28 | 28 | 17 | 15 | 139 |

ENT, Ear, nose & throat; GUM, Genitourinary; MSK, Muskuloskeletal.

Vignette characteristics

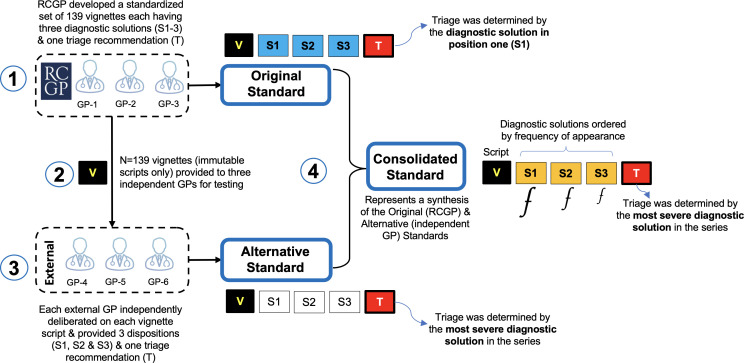

Each vignette (V) script was assigned three diagnostic solutions (S1–S3) describing the most likely ‘diagnosis’ in S1, and the least likely in S3 (figure 1). RCGP also assigned each vignette a single triage recommendation (T) which was based on the most likely diagnostic solution (in cell one, S1). The triage recommendation (T) could fall into any one of three categories: (1) self-care (ie, see pharmacist, self-limiting condition or self-care); (2) seek primary care (ie, see GP/doctor in 12 hours, 48 hours or 2 weeks), or (3) seek urgent care (ie, seek emergency treatment or call ambulance). The characteristics of each vignette can be summarised in a simple five-item cellular configuration illustrating the arrangement of S1, S2 and S3, and the triage recommendation (T) for each vigentte (V) (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Clinical vignette (V) creation process. GP, general practitioner; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

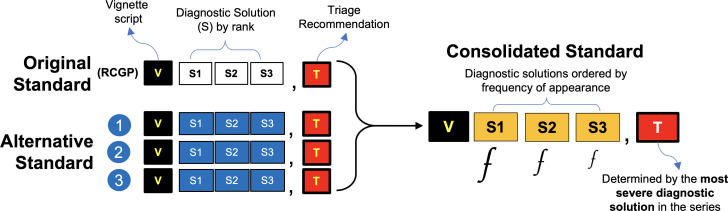

Figure 2.

Creating the consolidated set of diagnostic (S,1-3) and triage (T) solutions for each vignette. RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

External review of vignettes by independent GPs

We provided the vignette scripts to three independent GPs that had no connection with the OSC provider. The vignettes were provided without the diagnostic or triage solutions proposed by the RCGP. We asked the physicians to independently deliberate on each vignette and record up to three diagnostic solutions (S,1-3) and one triage (T) recommendation. We asked that each GP base their triage recommendation on the most severe diagnostic solution for each vignette. This resulted in the genesis of an ‘alternative’ set of diagnostic and triage solutions to the vignettes originally provided by the RCGP (figure 1).

Synthesising the consolidated diagnostic and triage solutions

A final refined set of diagnostic and triage solutions for each vignette that took into account the perspectives of both the RCGP and the independent panel of GPs was synthesised by consolidating the diagnostic and triage solutions of both roundtables. The correct diagnosis (S1, S2 and S3) for each vignette was synthesised by consolidating the solutions proposed in the preceding original and alternative sets. The correct diagnosis solutions were ordered by their frequency of appearance in the series, such that the most frequent solutions appeared in S1, and subsequently in S2 and S3 (figure 2). There were occasions when only S1 and S2 had a frequency of 2 or above. On occasion that a cell had diagnostic solutions with a frequency of just 1 each, it was not possible to order them objectively without introducing bias. In these instances, we reverted to the original (RCGP) set to assign the diagnostic solution for S2 and S3. The triage recommendation for each vigentte in this final iteration was based on the most severe diagnostic solution in the series.

Patient simulation by lay and expert inputters

The 139 vignettes were used by a panel of lay and expert inputters to benchmark the performance of Healthily OSC against all three standardised solutions for each vigentte. Two laypersons and four expert inputters recruited through personal contacts used the vignettes to independently record the consultation outcome and triage recommendation from Healthily OSC. One layperson was a 20-year-old female first-year university student, and the other lay inputter was a 47-year-old woman who completed a Bachelor of Arts degree. Neither layperson nor expert inputter had any previous or significant experience in using OSC. The four expert inputters recruited (two men and two women; age range=21–34 years) were all research assistants in the host research organisation (Department of Primary Care and Public Health). None of the inputters had a medical background; one-half had a social science background and the other two were careered in biomedical science. Interpretation of the vignette script was left to the individual inputters who did not have any additional information. The inputters were instructed to make the following blanket assumptions when answering the questions posed by OSCs: the simulated patient is a non-smoker, not pregnant, not obese, not taking medication, not diabetic, not hypertensive, has no history of heart disease, asthma, cancer, cystic fibrosis or other concerning or significant medical history, with no recent (3 months) sexual activity. Inputters were instructed to not include more than three consecutive symptoms in a single answer to any question posed by OSC.

Recording output

Healthily OSC may give up to three diagnostic solutions (S1, S2 and S3), whereas a single triage recommendation (T) may or may not be provided at the end of the online consultation. Inputters independently simulated the patient described in each vignette and recorded the consultation outcome (the diagnostic solution) using a case record form. Data were collected on up to three keywords used during input, details of any inputted keyword recognised by OSC, the first three consultation outcomes (if any) provided, the triage recommendation (if any), and whether the inputter was signposted to relevant information at the end (including external websites). Triage accuracy was defined as giving the appropriate triage recommendation (the primary outcome) relative to the standardised set of triage solutions being tested. A triage recommendation was deemed safe when it exactly matched the triage category of a standardised set, and ‘safe but overcautious’ when it recommended the more urgent triage category (eg, see doctor instead of self-care). A triage recommendation was deemed unsafe when it suggested a less urgent category (eg, seek ‘primary care’ instead of ‘urgent care’, or self-care instead of recommending ‘urgent care’). Diagnostic accuracy was defined as providing the correct consultation outcome (the secondary outcome) for each vignette. We also sought to investigate the extent that interpretations of the same vignette by different inputters could lead to different outputs using the same OSC by comparing the Cohen’s kappa which is a measure of inter-rater reliability (IRR) between groups of lay and expert inputters.

Consultation outcome data coding

To support with data management and objective analysis of output from OSC, we developed a simple framework to capture various output parameters. We assigned a three-digit numerical score to objectively characterise the level of agreement between the OSC consultation outcome and diagnostic solutions (S1, S2, S3) for each vignette:

(3): full agreement; correct consultation outcome appears in the exact same position as per the curated diagnostic solution in a given set.

(2): partial agreement (good); correct consultation outcome, but is one cell apart from the correct diagnostic solution (eg, S1 placement is found in S2, or S2 placement found in either juxtaposed cell).

(1): partial agreement (poor); correct consultation outcome, but the placement is two cells apart from the correct diagnostic solution (eg, S1 placement is found in S3 or vice versa).

(0): no agreement; incorrect consultation outcome in any cell, and not relating to a correct diagnostic solution in the set.

(9): null; or no output provided.

The resulting three-digit score described an output pattern that could be objectively analysed and weighted to benchmark the performance of OSC against the solutions in each standardised set. Of the 125 possible permutations of the three-digit score, only 59 combinations were considered logical in representing the levels of agreement between the diagnostic solutions from OSC and those in a standardised set (online supplemental table 1). The same terminology was used to describe the level of agreement between the triage solution in each set and the triage recommendation of the OSC (or the lack thereof).

bmjopen-2021-053566supp001.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

The consultation outcomes and triage recommendations from Healthily OSC were compared with the original, the alternative, and the consolidated sets of solutions for each vignette (figures 1 and 2). We estimated Cohen’s kappa coefficient which is a measure of IRR to investigate the extent that different interpretations of the same vignette by different inputters resulted in different consultation outcomes when using the same OSC.29 Kappa values <0.41 were rated as fair, between 0.41 and 0.60 as moderate, between 0.61 and 0.8 as good, and >0.81 as very good.30 Descriptive analysis was used to assess the perceived accuracy and safety of Healthily OSC against all three standardised sets. Data were expressed in frequencies, proportions and 95% CIs. Pearson’s Χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to determine whether there was a difference in signposting (eg, to links where the user can learn more about the same or similar conditions), the provision of a consultation outcome or a triage recommendation by different inputters using the same OSC and vignette. Significance was noted when p value was <0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software, V.16 (StataCorp 2019).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was embedded in this project. Two lay inputters were involved in the collection of output data from Healthily OSC.

Results

IRR testing

Independent panel of physicians

Overall, there was substantial agreement (kappa=0.66; table 2 and online supplemental table 2) in ‘self-care’ triage recommendation between the original triage solutions proposed by the RCGP and the alternative standard proposed by the independent panel of physicians (kappa=0.48; table 2), whereas therewas only fair (kappa=0.24) and moderate (kappa=0.44) agreement for ‘primary care’ and ‘urgent care’ triage recommendations in that same order (table 2).

Table 2.

Cohen’s kappa of agreement between the panel of physicians and RCGP split by triage and diagnostic solution

| RCGP vignettes in each triage category | GP1 | GP2 | GP3 | Cohen’s kappa | |

| Triage solution | |||||

| Self-care | 22 | 19 | 15 | 15 | 0.66 |

| Primary care | 85 | 72 | 86 | 41 | 0.24 |

| Urgent care | 32 | 45 | 38 | 83 | 0.44 |

| Unknown | – | 3 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Total | 139 | 139 | 139 | 139 | 0.66 |

| Diagnostic solution | |||||

| Correct in position one | – | 72 | 81 | 74 | 0.35 |

| Correct in any position | – | 111 | 114 | 110 | 0.29 |

GP, general practitioner; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

There was fair agreement (kappa=0.35) between the diagnostic solutions proposed by the independent panel of GPs and the RCGP when the correct solution appeared in the first cell (S1), and fair agreement (kappa=0.29) when the correct solution appeared in any cell (S1–S3); (table 2 and online supplemental table 3).

Lay and expert inputters

Overall, there was moderate agreement on triage recommendation from Healthily OSC between all inputters (expert and lay) and the original RCGP solutions across all vignettes (kappa=0.48, table 3 and online supplemental table 4). The agreement on triage recommendation between the expert inputters and the original RCGP solution was moderate (kappa=0.44) whereas it was fair (kappa=0.37) between lay inputters. The highest (almost perfect; kappa=0.84) agreement on triage recommendations was between the expert inputters for the self-care category (table 3). The lowest agreement between the expert inputters had a kappa of 0.29 for urgent care.

Table 3.

Cohen’s kappa coefficient of agreement between different inputters split by triage recommendation

| Overall | Self-care | Primary care | Urgent care | |

| All inputters | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.29 |

| Lay inputters | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.40 |

| Expert inputters | 0.44 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.29 |

We compared the consultation outcome from Healthily OSC from two lay inputters against the output recorded by four expert inputters to determine the extent that individuals could arrive at different solutions even when using the same vignette and OSC tool (online supplemental table 4). A significant difference was observed in consultation outcomes in position cells S1 (p<0.001) and S3 (p=0.03) between both type of expert inputters, but not for S2 (p=0.30) or the single triage (T) option (p=0.93). Overall, there was substantial agreement on consultation outcomes between all inputters (expert and lay) and the original RCGP solutions across all vignettes (kappa=0.73; table 3). The agreement across all vignettes on consultation outcomes between expert inputters was substantial (kappa=0.71), whereas it was almost perfect (kappa=0.84) among lay inputters.

Signposting at end of online consultation

There was no significant difference in signposting between expert inputters when using Healthily OSC (p=0.23; online supplemental table 5). However, there was a significant difference between the two lay inputters (p<0.001), and between the expert (n=4) and lay (n=2) inputters when compared as a group (p<0.001). There was significant variation between inputters with respect to whether the OSC provided signposting at the end for the same vignette, regardless of whether or not the simulation resulted in a triage recommendation (p<0.001). The difference disappeared when no triage recommendation was provided (p=0.21).

Benchmarking the performance of Healthily OSC

Diagnostic accuracy

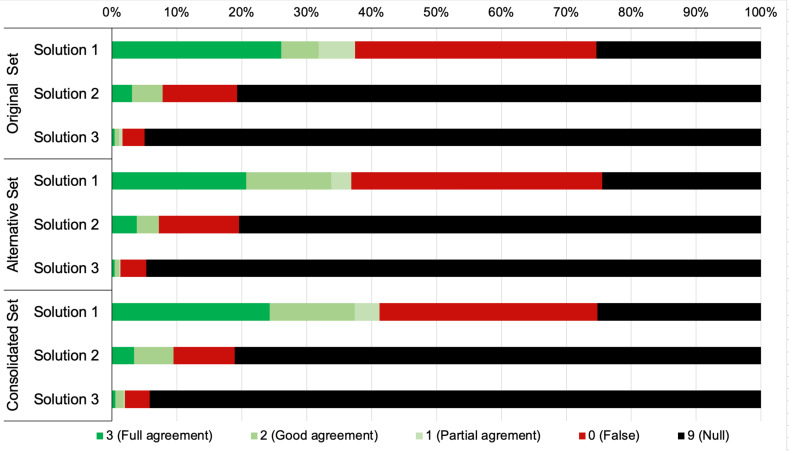

On average, Healthily OSC provided a diagnostic solution 74.6% of the time (figure 3). When compared against the original (RCGP) standard, Healthily OSC provided the correct diagnostic solution at any position 43.3% of the time (figure 4 and table 4). The diagnostic accuracy of OSC improved by 18.6% (increasing from 43.3% to 61.9%) when comparing the level of agreement for S1 between the original and final consolidated standards(p<0.001; table 4).

Figure 3.

Healthily OSC diagnostic accuracy benchmarked against three standards. OSC, online symptom checker.

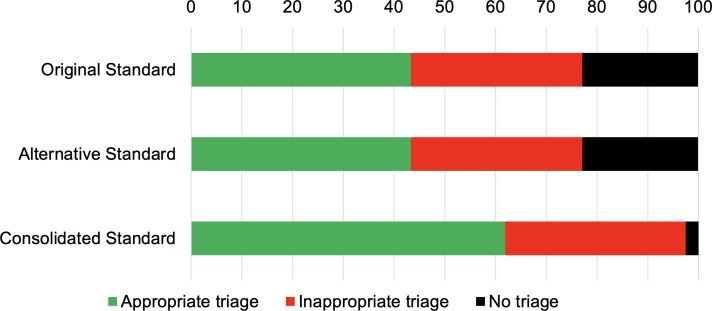

Figure 4.

Healthily OSC triage recommendations benchmarked against three standards. OSC, online symptom checker.

Table 4.

Safety of Healthily OSC triage recommendations against the final consolidated standard

| OSC triage recommendation | Correct triage solution | Total | ||

| Self-care | Primary care | Urgent care | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Self-care | 22 (30.6) | 15 (4.3) | 5 (3.7) | 42 (7.6) |

| Seek primary care | 45 (62.5) | 219 (62.9) | 28 (20.6) | 292 (52.5) |

| Seek urgent care | 1 (1.4) | 104 (29.9) | 103 (75.7) | 208 (37.4) |

| None—see a doctor | – | – | 11 (8.1) | – |

| Missing triage | 4 (5.6) | 10 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (2.5) |

| Total | 72 (100.0) | 348 (100.0) | 136 (100.0) | 556 (100.0) |

OSC, online symptom checker.

Triage recommendation

When benchmarking against the RCGP standard, Healthily OSC provided an appropriate triage recommendation 43.3% (95% CI 39.2% to 47.6%) of the time. However, the correct triage solution increased to 61.9% (95% CI 57.7% to 65.9%) of the time (p<0.001; table 5 and figure 4) when benchmarked against the final consolidated standard.

Table 5.

Diagnostic accuracy and triage output of Healthily OSC benchmarked against three standards

| Solution 1 | Solution 2 | Solution 3 | Triage | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Original (RCGP) set | ||||

| 3 (agree) | 145 (26.1) | 17 (3.1) | 2 (0.4) | 241 (43.3) |

| 2 (partial) | 32 (5.8) | 26 (4.7) | 4 (0.7) | – |

| 1 (partial) | 31 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | – |

| 0 (false) | 207 (37.2) | 64 (11.5) | 19 (3.4) | 188 (33.8) |

| 9 (null) | 141 (25.4) | 449 (80.8) | 528 (95.0) | 127 (22.8) |

| Correct (any) | 208 (37.4) | 43 (7.7) | 9 (1.6) | 241 (43.3) |

| Non-correct | 348 (62.6) | 513 (92.3) | 547 (98.4) | 315 (56.7) |

| Alternative (independent GP) set | ||||

| 3 (agree) | 115 (20.7) | 21 (3.8) | 2 (0.4) | 241 (43.3) |

| 2 (partial) | 73 (13.1) | 19 (3.4) | 4 (0.7) | – |

| 1 (partial) | 17 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| 0 (false) | 215 (38.7) | 69 (12.4) | 22 (4.0) | 188 (33.8) |

| 9 (null) | 136 (24.5) | 447 (80.4) | 527 (94.8) | 127 (22.8) |

| Correct (any) | 205 (36.9) | 40 (7.2) | 7 (1.3) | 241 (43.3) |

| Non-correct | 351 (63.1) | 516 (92.8) | 549 (98.7) | 315 (56.7) |

| Consolidated set | ||||

| 3 (agree) | 135 (24.3) | 19 (3.4) | 3 (0.5) | 344 (61.9) |

| 2 (partial) | 73 (13.1) | 34 (6.1) | 7 (1.3) | – |

| 1 (partial) | 21 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | – |

| 0 (false) | 187 (33.6) | 52 (9.4) | 21 (3.8) | 198 (35.6) |

| 9 (null) | 140 (25.2) | 451 (81.1) | 524 (94.2) | 14 (2.5) |

| Correct (any) | 229 (41.2) | 53 (9.5) | 11 (2.0) | 344 (61.9) |

| Non-correct | 327 (58.8) | 503 (90.5) | 545 (98.0) | 212 (38.1) |

GP, general practitioner; OSC, online symptom checker; RCGP, Royal College of General Practitioners.

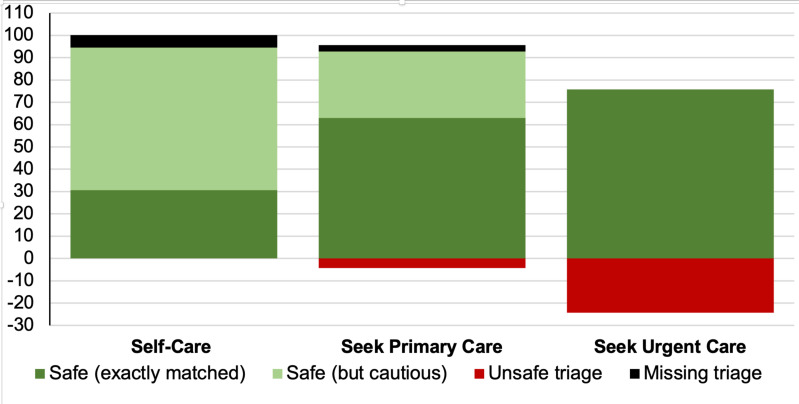

Safety of triage recommendation

When compared against the consolidated solutions, Healthily OSC made triage recommendations that were deemed unsafe 4.3% and 24.3% of the time (28.6% total) for vignettes describing a symptom that required primary care and emergent care, respectively (p<0.001; table 4 and figure 5).

Figure 5.

Safety of OSC triage recommendations benchmarked against the consolidated standard. OSC, online symptom checker.

Discussion

In this study, we used a novel series of clinical vignettes describing patient scenarios and symptoms across 18 subcategories of clinical care to determine if vignettes were a suitable tool that could be used to benchmark the performance of OSCs. Our approach included providing the vignettes to a panel of independent physicians to arrive at an alternative set of diagnostic and triage solutions as originally proposed by RCGP. We consolidated both iterations to arrive at a final refined standardised set of solutions and benchmarked the performance of a popular OSC using 834 unique patient simulations.

We showed significant variability of medical opinion depending on which group of GPs considered the vignette script, whereas consolidating the output of two independent GP roundtables (one from RCGP and another panel of panel of independent GPs) resulted in a more refined third iteration (the consolidated standard) which more accurately included the ‘correct’ diagnostic and triage solutions conferred by the vignette script. This was demonstrated by the significant extent that the performance of OSC improved when benchmarked between the original and final consolidated standards (diagnostic accuracy improved from 37.4% to 41.2% for S1, whereas congruent triage recommendation improved from 43.3% to 61.9%; table 5). The different qualities of the diagnostic and triage solutions between iterative standards suggest that vignettes are not an ideal tool for benchmarking the accuracy of OSC since performance will always be related to the nature and order of the diagnostic and triage solutions which we have shown can differ significantly depending on the approach and levels of input from independent physicians. By extension, it is reasonable to propose that any consolidated standard for any vignette can always be improved by including a wider range of medical opinion until saturation is reached and a final consensus emerges.

Another key factor that may impact the suitability of benchmarking OSC using clinical vignettes is related to the inputter’s inability to answer truthfully all the questions that may be asked during the online consultation process. This inherent methodological limitation necessitates the use of blanket assumptions (eg, the inputter is instructed to always indicate that they are ‘not pregnant’, do not have a any long-term condition, or that they ‘did not have any recent sexual activity’, etc). In contradistinction to a real patient who is experdncing the symptoms and can always answer thruthfully, when inputters use these blacket assumptions they could arrive at a different consultation outcome (including a different diagnostic solution and/or triage recommendation) compared to the intended end user who may have a long-term condition or be a smoker for example. The moderate agreement (kappa=0.48) between different inputters overall, which reduced to only fair agreement (kappa=0.29) for case vignettes with an urgent triage recommendation, suggests that the wording of some vignettes could be revised to reduce the likelihood of divergent interpretations of the same script. It is inevitable that different people will use different words to describe their conditions, necessitating the use of machine learning to render OSC capable of understanding multiple different descriptions of the same problem. Further, the vignette script is necessarily limited in the number of words, and even if the description and context were expanded, it may still not capture all the information necessary to simulate how a real patient may engage with the same OSC. These inherent limitations were illustrated by how different inputters arrived at different diagnostic solutions when using the same vignette script and the same OSC.

Another key outcome measure was the congruence of the triage recommendation made by the online tool or each vignette relative to the correct solutions proposed in the original and subsequent iterations following input from an independent panel of physicians. Whereas RCGP always made a triage recommendation that was based on the first (most likely) ‘correct’ solution (ie, S1) for each vignette, the triage recommendation in the alternative and consolidated standards was always based on the most severe diagnostic solution regardless of whether it appeared first or within the top three placements in the series. Recommending a triage option that was based on the most severe disposition—or ‘worst case scenario’—is appropriate for OSC because this enhances patient safety, even on occasion when the triage option is safe but overcautious. For example, if ‘indigestion’ (S1), ‘costochondritis’ (S2) and ‘heart attack’ (S3) appeared in that same order, the appropriate triage recommendation is to base the triage on 'heart attack' and therefore to ‘seek urgent care’ even if this potential diagnosis did not appear first in the series.

That Healthily recommended ‘unsafe’ triage 28.6% overall, and very unsafe triage only 3.7% of the time suggests that the online consultation tool is generally working at a safe level of probable risk, and more frequently made an appropriate triage recommendation or signposted the user to the more urgent triage category as opposed to the other way around. This was unsurprising as it is reasonable to expect OSCs to be ‘risk averse’ since these decision support tools arrive to a conclusion with limited data and without human interaction.31

Although the diagnostic solutions proposed by an independent panel of physicians agreed with the RCGP solutions on average 72% of time, and on triage 74% of the time, this did not mean that any of the GPs were wrong. When GPs diagnose, they assess probable risk and then investigate. This implies that primary care assessment is not binary; there is often not a correct answer but rather a series of options that could be explored with the patient to help resolve the symptoms and treat the condition using evidence-based decision-making refined over time including the use of further tests. By contrast, the provenance of a clinical vignette usually starts from the condition and builds a story, whereas conversely GPs and OSCs start with the story and then work towards a probable condition. Often, as we saw following the independent deliberations of a panel of physicians, there are many possible conditions in the ‘area’ a vignette might point towards. We found that both the online consultation tool and the physicians were in the right area but not precisely ‘correct’. This demonstrates why any claims that an OSC can ‘diagnose’ need to be challenged, since GPs do not diagnose and therefore OSCs cannot. Diagnosis can only come after testing and verification of the initial hypothesis, and accurate diagnosis usually includes other aspects such as imaging, pathology results involving the use of point-of-care and other near patient testing procedures.

Our audit study had a number of limitations, including that the original RCGP diagnostic and triage solutions for each vignette offered a baseline for assessment but could not be considered as the ‘ideal’ or ‘gold’ standard even after additional input from an external roundtable of independent GPs. Other limitations included a small sample of vignettes and using only one OSC.4 Despite these limitations, the framework and pragmatic methodology used to support the objective development of the consolidated set consisting of 139 vignettes with congruent diagnostic and triage solutions were suitable to benchmark the performance of online consultation tools. We acknowledge also that the final consolidated set can be developed further by inviting input from a larger number of GPs. Further work is indicated to refine the wording of some vignettes since there is a large variation in how different inputters could interpret each item leading to different diagnostic solutions and triage recommendation (the main output parameters) even when using the same OSC tool.

There are a number of person-centred and policy implications for the use of OSC.4 For example, access to healthcare is a major issue and this has become more pronounced since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic.32 Improving access to primary care and/or pre-primary care health advice is expected to reduce pressure on urgent and secondary care services, and this is a main driver for the use of a safe and effective OSC that offer congruent and safe triage recommendations to end-users in the community setting. The widespread adoption and diffusion of OSC with added functionality can help empower individuals, improve health literacy levels through microlearning,33 and may even promote individual self-care capability and the rational use of products and services. This applies especially for OSCs that signpost users to relevant information that could help them determine possible next steps regardless of whether the OSC provided a triage recommendation or not. At this stage in their development, OSCs must be risk averse by avoiding undertriage where patients are directed to a less urgent service. This may have a negative impact on health service resources in that it may result in unnecessary use of urgent or emergency health providers but may equally result in an earlier diagnosis and appropriate treatment of medical conditions which reduces morbidity, mortality and overall costs in the long term. The rational use of OSC may in the future decrease the high demand on primary care providers and this utility is especially welcome since the workload for GPs in the UK has increased by 62% from 1995 to 2008,34 whereas there has been very little or no increase in the number of GPs per 1000 population.35

A recent paper highlighted a wide variation in performance between available symptom checkers and showed that overall performance is significantly below what would be accepted in any other medical field.4 The authors concluded that external validation is urgently required to ensure these public-facing tools are safe. Our study showed that vignettes are not ideally suited to benchmark the performance of OSC as inter-rater agreement is not perfect between different inputters and because larger roundtables of independent physicians could lead to more refined iterations of the diagnostic and triage solutions for each vignette thus leading to different outomes. Further work is recommended to cross-validate the performance of OSCs against real-world test case scenarios using real patient stories and interactions with GPs as opposed to using case vignettes only.

Conclusion

Inherent limitations of clinical vignettes render them largely unsuitable for benchmarking the performance of popular OSCs because the diagnosis and triage solutions assigned to each vignette script are amenable to change pending the deliberations of an independent panel of physicians. Although OSCs are already working at a safe level of probable risk, further work is recommended to cross-validate the performance of OSCs against real-world test case scenarios using real patient stories and interactions with GPs as opposed to using artificial vignettes only which will always be the single most important limitation to any cross-validation study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Reynie Purnama Raya, Ms Noor Jawhar, Ms Christina Pillay and Mr John Norton for PPI input and for testing the symptom checkers, and Drs Aisha Newth, Prakash Chatlani, David Mummery and Benedict Hayhoe for clinical support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @austenelosta, @ebagkeris, @Azeem_Majeed

Contributors: All authors provided substantial contributions to the conception (AE-O, IW, AA, EB, AM), design (AE-O, EB, IW, AA), acquisition (IW, AA, EB) and interpretation (EB, IW, SM, MTAS) of study data and approved the final version of the paper. AE-O took the lead in planning the study with support from coauthors. EB carried out the data analysis with support from AA and MTAS. AE-O is the guarantor.

Funding: Unconditional funding for this work was provided by Healthily (IC Self-Care 2020/1). AEO, IW and AA are in part supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) Northwest London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS or the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Disclaimer: The funder did not have a role in study design or analysis.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Twitter: @austenelosta, @ImeprialSCARU, @Imeprial_PCPH, @Azeem_Majeed

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not sought for this study as it did not involve recruitment of participants or the use of patient-identifiable data.

References

- 1.North F, Ward WJ, Varkey P, et al. Should you search the Internet for information about your acute symptom? Telemedicine and e-Health 2012;18:213–8. 10.1089/tmj.2011.0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Online 2013 [Internet] . Internet and American life project, 2013. Available: https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf

- 3.World Health Organization . Regional office for south-east A. self care for health. 2014. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ceney A, Tolond S, Glowinski A, et al. Accuracy of online symptom checkers and the potential impact on service utilisation. PLoS One 2021;16:e0254088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0254088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupton D, Jutel A. ‘It’s like having a physician in your pocket!’ A critical analysis of self-diagnosis smartphone apps. Soc Sci Med 2015;133:128–35. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kröger J, et al. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European prospective investigation into cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1355–62. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf JA, Moreau JF, Akilov O, et al. Diagnostic inaccuracy of smartphone applications for melanoma detection. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:422–6. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saczynski JS, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. Trends in prehospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction (from the worcester heart attack study). Am J Cardiol 2008;102:1589–94. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copestake J. Babylon claims its chatbot beats GPs at medical exam: BBC, 2018. Available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-44635134

- 10.Razzaki S, Baker A, Perov Y. A comparative study of artificial intelligence and human doctors for the purpose of triage and diagnosis. arXiv preprint arXiv 2018:180610698. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Lancet . Is digital medicine different? The Lancet 2018;392:95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31562-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coiera E. Paper review: the Babylon Chatbot. Available: https://coieracom/2018/06/29/paper-review-the-babylon-chatbot/ [Accessed 09 Aug 2018].

- 13.Chambers D, Cantrell AJ, Johnson M, et al. Digital and online symptom checkers and health assessment/triage services for urgent health problems: systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027743. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011;43:255–64. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser H, Coiera E, Wong D. Safety of patient-facing digital symptom checkers. The Lancet 2018;392:2263–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32819-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powley L, McIlroy G, Simons G, et al. Are online symptoms checkers useful for patients with inflammatory arthritis? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:1–6. 10.1186/s12891-016-1189-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Linden MPM, le Cessie S, Raza K, et al. Long-Term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3537–46. 10.1002/art.27692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar K, Daley E, Carruthers DM, et al. Delay in presentation to primary care physicians is the main reason why patients with rheumatoid arthritis are seen late by rheumatologists. Rheumatology 2007;46:1438–40. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheppard J, Kumar K, Buckley CD, et al. 'I just thought it was normal aches and pains': a qualitative study of decision-making processes in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2008;47:1577–82. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar K, Daley E, Khattak F, et al. The influence of ethnicity on the extent of, and reasons underlying, delay in general practitioner consultation in patients with RA. Rheumatology 2010;49:1005–12. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stack RJ, Shaw K, Mallen C, et al. Delays in help seeking at the onset of the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:493–7. 10.1136/ard.2011.155416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semigran HL, Linder JA, Gidengil C, et al. Evaluation of symptom checkers for self diagnosis and triage: audit study. BMJ 2015;351:h3480. 10.1136/bmj.h3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans SC, Roberts MC, Keeley JW, et al. Vignette methodologies for studying clinicians' decision-making: validity, utility, and application in ICD-11 field studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2015;15:160–70. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veloski J, Tai S, Evans AS, et al. Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:151–7. 10.1177/1062860605274520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Converse L, Barrett K, Rich E, et al. Methods of observing variations in physicians' decisions: the opportunities of clinical Vignettes. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30 Suppl 3:586–94. 10.1007/s11606-015-3365-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert S, Mehl A, Baluch A, et al. How accurate are digital symptom assessment apps for suggesting conditions and urgency advice? a clinical vignettes comparison to GPs. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040269. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Semigran HL, Linder JA, Gidengil C, et al. Evaluation of symptom checkers for self diagnosis and triage: audit study. BMJ 2015;351:h3480. 10.1136/bmj.h3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, et al. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 2004;291:2616–22. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jungmann SM, Klan T, Kuhn S, et al. Accuracy of a Chatbot (ADA) in the diagnosis of mental disorders: comparative case study with lay and expert users. JMIR Form Res 2019;3:e13863. 10.2196/13863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977;33:363–74. 10.2307/2529786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1493–9. 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majeed A, Maile EJ, Bindman AB. The primary care response to COVID-19 in England's National health service. J R Soc Med 2020;113:208–10. 10.1177/0141076820931452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Bakhet M, Roberts D, et al. The efficacy of microlearning in improving self-care capability: a systematic review of the literature. Public Health 2020;186:286–96. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell JL, Fletcher E, Britten N, et al. Telephone triage for management of same-day consultation requests in general practice (the Esteem trial): a cluster-randomised controlled trial and cost-consequence analysis. Lancet 2014;384:1859–68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61058-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson M, O'Neill C, Macleod Clark J, et al. Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce. Lancet 2021;397:1992–2011. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00231-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053566supp001.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.