Abstract

An l-rhamnosyl residue plays an essential structural role in the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Therefore, the four enzymes (RmlA to RmlD) that form dTDP-rhamnose from dTTP and glucose-1-phosphate are important targets for the development of new tuberculosis therapeutics. M. tuberculosis genes encoding RmlA, RmlC, and RmlD have been identified and expressed in Escherichia coli. It is shown here that genes for only one isotype each of RmlA to RmlD are present in the M. tuberculosis genome. The gene for RmlB is Rv3464. Rv3264c was shown to encode ManB, not a second isotype of RmlA. Using recombinant RmlB, -C, and -D enzymes, a microtiter plate assay was developed to screen for inhibitors of the formation of dTDP-rhamnose. The three enzymes were incubated with dTDP-glucose and NADPH to form dTDP-rhamnose and NADP+ with a concomitant decrease in optical density at 340 nm (OD340). Inhibitor candidates were monitored for their ability to lower the rate of OD340 change. To test the robustness and practicality of the assay, a chemical library of 8,000 compounds was screened. Eleven inhibitors active at 10 μM were identified; four of these showed activities against whole M. tuberculosis cells, with MICs from 128 to 16 μg/ml. A rhodanine structural motif was present in three of the enzyme inhibitors, and two of these showed activity against whole M. tuberculosis cells. The enzyme assay was used to screen 60 Peruvian plant extracts known to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis in culture; two extracts were active inhibitors in the enzyme assay at concentrations of less than 2 μg/ml.

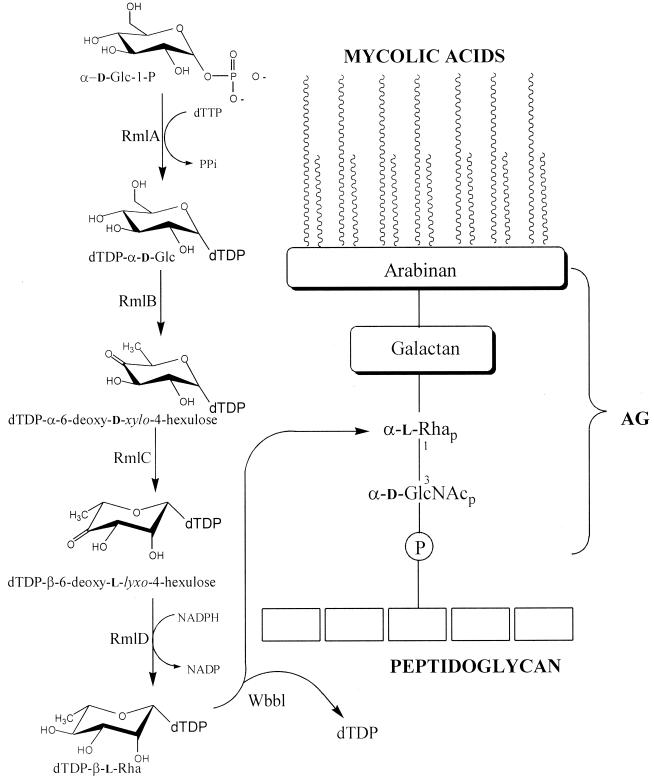

The necessity for new drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis due to increasing resistance to the present chemotherapeutic agents is well documented (6, 12, 21, 33, 41, 44). An attractive target for such new agents is the mycobacterial cell wall (2, 3, 29), since the wall is necessary for viability and several known drugs such as isoniazid (52) and ethambutol (11, 49) inhibit cell wall synthesis. The mycobacterial cell wall core consists of three interconnected macromolecules (Fig. 1). The outermost, the mycolic acids, are 70- to 90-carbon-containing, branched fatty acids which form an outer lipid layer in some ways similar to the classical outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria (5). The mycolic acids are esterified to the middle component, arabinogalactan (AG), a polymer composed primarily of d-galactofuranosyl and d-arabinofuranosyl residues. AG is connected via a linker disaccharide, α-l-rhamnosyl-(1→3)-α-d-N-acetyl-glucosaminosyl-1-phosphate, to the 6 position of a muramic acid residue in the peptidoglycan. The peptidoglycan is the innermost of the three cell wall core macromolecules.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the mycobacterial cell wall, drawn to emphasize the role of the essential rhamnosyl residue. Also shown is the formation of dTDP-Rha by the Rml enzymes and its use by rhamnosyl transferase (WbbL). Not depicted is the fact that the rhamnosyl residue is donated to the 3 position of the GlcNAc residue in the context of a carrier lipid. The newly synthesized AG molecule is ultimately transferred from the carrier lipid to peptidoglycan and mycolylated (31).

This structural arrangement shows why AG is necessary for mycobacterial viability, as it tethers the lipid layer to the peptidoglycan layer. Moreover, a rhamnosyl residue, a sugar not found in humans, plays a crucial structural role in the attachment of AG to peptidoglycan (Fig. 1). (l-Rhamnosyl residues are found in other bacteria as components of O antigens or extracellular polysaccharides but not as an essential cell wall component.) l-Rhamnosyl residues are synthesized in nature by a single pathway requiring four enzymes (RmlA to RmlD) and beginning with TTP and α-d-glucose-1-phosphate (13, 19, 32, 36), as shown in Fig. 1. There is no salvage pathway for the formation of dTDP-l-rhamnose (dTDP-Rha) as with GDP-l-fucose (38, 39), and when l-rhamnose is utilized by bacteria as a carbon source, it is isomerized and broken down into smaller metabolites (26). Thus, the only way for M. tuberculosis to form the cell wall rhamnosyl residue is as shown in Fig. 1. In another study (J. A. Mills, K. Motichka, M. Jucker, H. P. Wu, B. C. Uhlic, R. J. Stern, M. S. Scherman, V. Vissa, W. Yan, M. Kundu, M. Kundu, and M. R. McNeil, unpublished data), it has been shown that the rhamnosyl transferase (encoded by the gene wbbL) that utilizes dTDP-Rha as a substrate to put the rhamnosyl residue into cell wall AG is essential for bacterial growth. Although the rhamnosyl transferase is a good drug target in itself, there are many advantages in targeting the four enzymes required to make its required substrate, dTDP-Rha. These include the facts that the enzymes are soluble (22, 28, 46), that crystal structures of these enzymes from bacteria are forthcoming (1, 15–17), and that for one of these enzymes, RmlB, detailed mechanistic studies have been performed (18, 34, 42, 45).

Although the completion of the entire genome sequence of M. tuberculosis (8) greatly aids in the identification of the enzymes involved in dTDP-l-rhamnose synthesis, unambiguous identification from just the sequence data is problematical. In addition, it is important to determine whether additional genes encoding isoenzymes for any of the key conversions exist, because inhibition of multiple enzymes catalyzing the same reaction might be difficult. Here, we report experiments to determine which of the genes encoding proteins with homology to RmlA to RmlD actually encode dTDP-Rha formation enzymes. Following this, a microtiter plate assay to identify inhibitors of the conversion of dTDP-glucose to dTDP-rhamnose by M. tuberculosis RmlB, -C, and -D was developed. The assay was used to screen both pure compounds and crude plant extracts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of plasmids to express M. tuberculosis genes.

Rv3264c, Rv3464, Rv3784, and Rv3468c were cloned into pET29b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). PCR was conducted using the following primers (coding sequence to the right of the hyphen): Rv3264c, 5′GGAATTCCAT-ATGGCAACTCACCAAGTCGAT3′ (sense) and 5′CCGCTCGAG-TCAAACGTCGGACGAGTAACGGA3′ (antisense); Rv3464, 5′TTACAT-ATGCGGTTGCTAGTCACC3′ (sense) and 5′TTACTCGAG-TCATTGACCGCGTTCTTGAT3′ (antisense); Rv3784, 5′CGTAGGCATTA-ATGGAAATACTTGTCACCGG3′ (sense) and 5′CCGCTCGAG-TTAGAGAACGCTGGAACCGCTA3′ (antisense); and Rv3468c, 5′GCGTAGGCATTA-ATGGTGGGAACACATGCAGCCACC3′ (sense) and 5′ATTCCGCTCGAG-TCAGGGCCTGGCCGGAGCAAACA3′ (antisense). The PCR products were ultimately cloned into pET29b using the NdeI and XhoI sites present in pET29b (the PCR products of Rv3784 and Rv3468c were cleaved with AseI, which makes an overhang that can go into an NdeI site). Rv3464 was also cloned with an N-terminal His tag using 5′TTACAT-ATGCGGTTGCTAGTC3′ (sense) and 5′TTACTCGAG-TCATTGACCGCGTTCTTG3′ (antisense) using the NdeI and XhoI sites to clone into pET16b (Novagen).

Escherichia coli strains.

E. coli DH5α (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, N.Y.) was used for cloning purposes. For expression, potential rmlB-bearing plasmids were electroporated into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen); the potential rmlA- or manB-bearing plasmid (Rv3264c) was electroporated into E. coli sφ874(DE3) (22, 48).

Assay for α-d-glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) and α-d-manose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase (ManB) activities.

To prepare the enzyme extract, E. coli sφ874(DE3) containing open reading frame (ORF) Rv3264c cloned into pET29b (and, separately, an empty pET29b control) was grown to an optical density (OD) of 0.6 to 0.7 with agitation at 37°C. The culture was induced (at 37°C) with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 1 mM for 3 h and harvested by centrifugation. The enzyme assay mixture (total volume, 50 μl) contained ∼25 pmol of TDP-[14C]Glc (11,700 cpm), ∼22 pmol of GDP-[14C]Man (9,700 cpm), 50 nmol of PPi (when present), 500 nmol of MgCl2, and 34 μg of E. coli soluble protein (20,000 × g supernatant after sonication) in 50 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.6. The E. coli cells from which the soluble protein was prepared carried either pET29b (control) or pET29b with a Rv3264c insert. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and then boiled for 5 min followed by the addition of dTDP-Rha (9,070 cpm) as an internal standard. Denatured protein was removed by centrifuging at 14,000 × g for 5 to 10 min. The supernatant was analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a PA-100 (Dionex, Sunnyvale, Calif.) ion-exchange column with a gradient of 75 to 500 mM KH2PO4 over a 30-min period at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Radioactive sugar nucleotides were detected using a Beta-Ram (INUS, Tampa, Fla.) HPLC radio detector upon elution.

Assay for dTDP-glucose dehydratase (RmlB) activity.

The assay for dTDP-glucose dehydratase (RmlB) activity was performed as previously described (53) by monitoring the appearance of a degradation compound(s) produced from the enzyme product, dTDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexulose, in the presence of base. The E. coli cells with various plasmids were grown to an OD of 0.6 to 0.7 with agitation at 37°C. The cultures were cooled to room temperature (around 25°C) for 30 to 60 min, induced with IPTG at 1 mM for 3 to 5 h, and harvested by centrifugation. The cells were then broken by sonication, and 8 μg of soluble protein (20,000 × g supernatant) was added to 100 nmol of dTDP-Glc in a total of 200 μl of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6) containing 1 mM NAD+ (addition of NAD+ was necessary for the M. tuberculosis RmlB to retain enzymatic activity). After a 1-h incubation at 37°C, 1 ml of 0.1 M NaOH was added, the tube was incubated for 20 more minutes at 37°C, and the absorbance was read at 318 nm.

Purification of RmlB.

E. coli BL21(DE3)(pET29b-Rv3464) cells were grown to an OD of 0.7 to 0.8 with agitation at 37°C. The culture was cooled to room temperature (around 25°C) for 30 to 60 min, induced with IPTG at 0.2 mM for 3 to 5 h, and harvested by centrifugation. Cells were broken using a French press in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6) buffer containing 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 μM pepstatin A, 1 μM leupeptin, and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The soluble fraction (20,000 × g supernatant) was dialyzed into 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 50 mM NaCl at 4°C and applied to a DEAE Sephadex Fast Flow column (10-ml bed volume, 2-cm diameter) equilibrated in the same buffer. The column was eluted with 30 ml each of 100, 200, 300, and 500 mM NaCl in the Tris buffer; RmlB was found in the 200 mM fraction (as visualized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or by enzyme assay). The RmlB fraction was then dialyzed into 25 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 100 mM NaCl and concentrated to around 4 ml. This fraction was injected on HPLC using a Poros Pmax HQ/M (4.6 by 100 mm; Applied Biosystems-PerSeptive, Framingham, Mass.) ion-exchange column equilibrated with 25 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 100 mM NaCl. The flow rate was 5.1 ml/min. After a 2-min wash with 25 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 100 mM NaCl, a linear gradient to 400 mM Tris (pH 8) containing 500 mM NaCl over 10 min was run. Following a 4-min wash with the second buffer, the column was further washed with 25 mM Tris containing 1 M NaCl. Fractions (0.5 min/2.5 ml) were collected, and RmlB was located by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or enzyme assay. The fractions containing the RmlB were dialyzed into 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), concentrated to approximately 0.2 mg/ml by ultrafiltration, made 20% with respect to glycerol, and stored at 4°C.

Microtiter plate assay for production of dTDP-Rha from dTDP-glucose.

The assay for production of dTDP-Rha was performed in standard, clear, spherical-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates in a volume of 100 μl. Typically, 2 μl containing 1 nmol (for pure compounds) and 5 μg (for plant extracts) of each inhibitor in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) were added, including a control inhibitor of 300 nmol of dTDP and a control of DMSO only. A cocktail (75 μl) of HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 7.6, with 1 mM MgCl2 and 10% glycerol) containing 0.5 nmol of NAD+, 20 nmol of NADPH (prepared fresh daily), 1 μg of RmlB, 1 μg of RmlC, and 0.4 μg of RmlD was added to each well. (These enzyme amounts were found empirically to be in the range where the decrease of any of the three enzymes resulted in a decrease in overall activity.) The reactions were started by adding 20 nmol of dTDP-Glc in 25 μl of the HEPES buffer to each well, and the plate was incubated at 30°C. At different time points, samples were examined on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader, typically at 0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min at 340 nm, and the data were analyzed by comparing the slopes of the potential inhibitors with the slopes of the controls using the computer program Excel. To assay RmlC, a 1-h preincubation using the above cocktail, modified to contain 2 μg of RmlB and no RmlC or RmlD, was performed to prepared dTDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexulose in situ. Then, 0.25 μg of RmlC and 4 μg of RmlD and NADPH were added, and the reaction was monitored as described above. To assay RmlD, dTDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexulose in situ in the same fashion and then 10 μg of RmlC and 0.4 μg of RmlD were added and the reaction was monitored as described above.

Assays against M. tuberculosis in culture.

Compounds were assayed against M. tuberculosis H37Rv in culture by the Alamar blue assay as described previously (9).

RESULTS

Genes encoding RmlA.

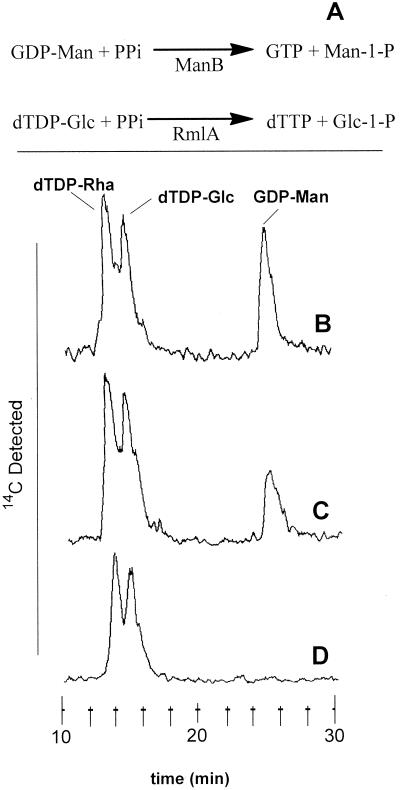

We have reported the cloning and expression of an M. tuberculosis gene encoding RmlA (28). This gene was designated Rv0334 and identified as rmlA in the genome sequence paper (8). However, the genome was found to contain another ORF, Rv3264c, encoding a protein with strong homology to RmlA (8). In addition, this ORF was in an operon with wbbL and rmlD (see discussion of rmlD below), strongly suggesting a second rmlA gene, and Rv3264c was therefore designated rmlA2 (8). However, the protein encoded by this ORF also showed homology to ManB, the analogous enzyme in GDP-mannose synthesis that forms GDP-mannose from α-d-mannose-1-phosphate and GTP (α-d-mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase). To resolve this issue, ORF Rv3264c was cloned into pET29b and expressed in E. coli sφ874(DE3), a strain (48) which was modified to contain DE3 in the chromosome (22) and which does not express an E. coli version of either manB (as shown in Fig. 2) or rmlA (also shown in Fig. 2; also, the rml genes, which are part of the rfb cluster, are known to be deleted [35, 48]). Extracts from the bacterium transformed with pET29b-Rv3264c and pET29b (vector-only control) were assayed for both α-d-glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) and α-d-mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase (ManB) activities in the reverse-direction reaction by monitoring the PPi-dependent loss of dTDP-Glc and/or GDP-Man as shown in Fig. 2. The result was that the enzyme expressed from the Rv3264c gene was active only against GDP-Man (Fig. 2), demonstrating that Rv3264c encodes ManB. These results were consistent with a recent report of the purification of ManB from Mycobacterium smegmatis (37), where the N-terminal sequence of the M. smegmatis protein (37) shows 17 identical amino acids out of 20 compared with the N-terminal region of the protein product of Rv3264c. Also supporting this assignment is the fact Rv3264c is the only potential copy of manB in the genome (8) and, since mannose is a component in many M. tuberculosis glycoconjugates, manB must be present. Therefore, as no other genes with homology to rmlA are found in the M. tuberculosis genome, we conclude that only a single isotype of this enzyme is present in M. tuberculosis.

FIG. 2.

Determination of the enzyme activity of the gene product of Rv3264c. (A) Reactions catalyzed by α-d-glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) and α-d-mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase (ManB) in the reverse direction. To assay for both enzyme activities at the same time, the substrates dTDP-[14C]Glc and GDP-[14C]Man were incubated as follows. (B) Incubation, in the presence of PPi, of an enzyme extract of E. coli sφ874(DE3) containing the control plasmid pET29b (no insert). This experiment showed the lack of either enzyme in E. coli sφ874(DE3) itself. (C) Incubation, in the absence of PPi, of an enzyme extract of E. coli sφ874(DE3) containing pET29b-Rv3264c. This experiment showed the lack of nonspecific phosphodiesterase activity. (D) Incubation, in the presence of PPi, of an enzyme extract of E. coli sφ874(DE3) containing pET29-Rv3264c. The GDP-Man but not the dTDP-Glc was degraded, demonstrating that the enzyme encoded by Rv3264c is ManB.

Genes encoding RmlB.

Four ORFs encoding proteins with homology to RmlB are found in the M. tuberculosis genome (8). The protein product of Rv3464 (designated rmlB in the genome sequence) shows the highest homology to RmlB of other organisms, but three other genes encoding proteins with significant homology to RmlB are Rv3634c (designated rmlB2 in the genome sequence), Rv3784 (designated epiB in the genome sequence), and Rv3468c (designated rmlB3 in the genome sequence).

Rv3634c has an N-terminal sequence identical, except for one amino acid, to that of UDP-galactose epimerase (GalE) purified from M. smegmatis (51). We thus conclude that this ORF encodes GalE rather than RmlB. GalE and RmlB enzymes catalyze similar oxidation at C-4 of a glucosyl residue and in general show strong homology to each other.

Rv3464 was cloned into pET29b and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3), and the enzyme was partially purified. The band of the putative RmlB protein was blotted to nitrocellulose and trypsinized, and the resulting peptides was analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, which confirmed the identity of the expressed polypeptide. The two remaining candidates, Rv3784 and Rv3468c, were also cloned into pET29b and expressed in soluble form in E. coli BL21(DE3). Extracts containing the expressed protein were then assayed for dTDP-glucose dehydratase (RmlB) activity. Activity (OD at 318 nm [OD318] = 0.425) was readily observed for the strain expressing Rv3464, but no activity was seen for the strains expressing Rv3784 (OD318 = 0.046) or Rv3468c (OD318 = 0.068) or a control strain containing only the empty pET29b vector (OD318 = 0.074). These results are consistent with only one isotype of RmlB, the one that shows a very high homology with RmlB from other organisms, although the limitations of drawing conclusions from the lack of enzymatic activity are recognized.

Genes encoding RmlC and for RmlD.

The M. tuberculosis genome sequence (8) shows only a single ORF encoding a protein with homology for RmlC (Rv3465) and also only a single ORF encoding a protein with homology for RmlD (Rv3266c). Both Rv3465 (46) and Rv3266c (22) have previously been expressed, and these genes do express the dTDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexulose epimerase (RmlC) and dTDP-6-deoxy-l-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase (RmlD) enzymes, respectively. Thus, only single polypeptides with sequences corresponding to RmlC and RmlD are present in the M. tuberculosis genome.

Development of a microtiter-based assay for RmlB, -C, and -D.

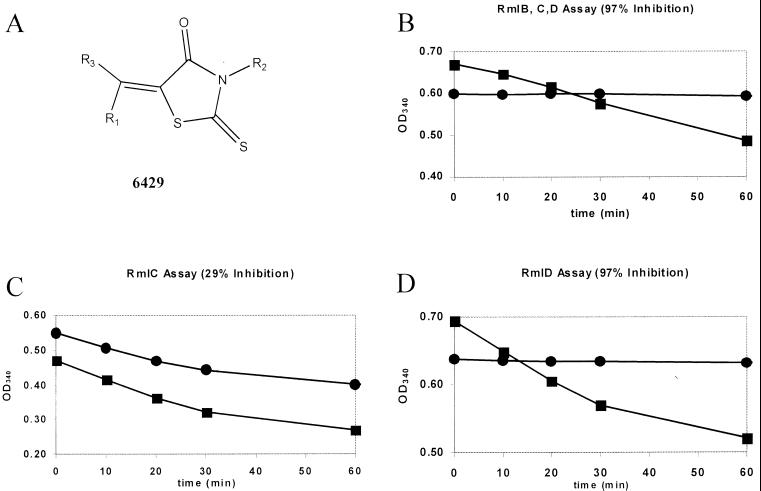

The fact that RmlD converts dTDP-6-deoxy-l-lyxo-4-hexulose to dTDP-Rha with the concomitant oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ makes possible a facile microtiter plate assay. Thus, a mixture of RmlB (this study), RmlC (46), and RmlD (22) was incubated with dTDP-Glc (0.2 mM) and NADPH (0.2 mM) in microtiter plates at 37°C, and the OD340 was monitored. Controls with no dTDP-Glc and with an inhibitor, dTDP, were also performed. The OD340 drops in a linear fashion in the early part of the time course (Fig. 3B [control reaction]). It was found necessary to purify all enzymes to avoid a non-dTDP-Glc-dependent oxidation of NADPH. NAD+ was also included in the reaction mixtures, since it was found that after purification of RmlB it was necessary to keep the enzyme active. It was also found that individual proteins had to be sufficiently pure not to reduce NAD+ to NADH (which absorbs at OD340), presumably via oxidation of glycerol present to help with the storage of the enzymes.

FIG. 3.

(A) Rhodanine motif of 6429. (B) 6429 inhibits the formation of dTDP-Rha from dTDP-Glc, as shown by the lack of oxidization of NADPH catalyzed by the three enzymes during the reaction. The control reaction (▪) proceeded with a slope of −3.21 × 10−3/OD340 unit/min; when 6429 was present (●), the reaction was essentially completely inhibited (slope = −0.29 × 10−5 OD340 units/min). (C) 6429 does not inhibit RmlC. The assay was modified as described in Materials and Methods to determine the activity of RmlC. The control (▪) proceeded with a slope of −2.78 × 10−3; with 6429 (●), the slope was −1.99 × 10−3 (29% inhibition and perhaps due to residual inhibition of RmlD). (D) 6429 inhibits RmlD. The assay was modified as described in Materials and Methods to determine the activity of RmlD. The control (▪) proceeded with a slope of −2.28 × 10−3; with 6429 (●), the slope was −9.43 × 10 −5. Not illustrated is the fact that 6429 somewhat inhibits RmlB (52% [Table 1]). In all cases, 6429 was tested at 10 μM.

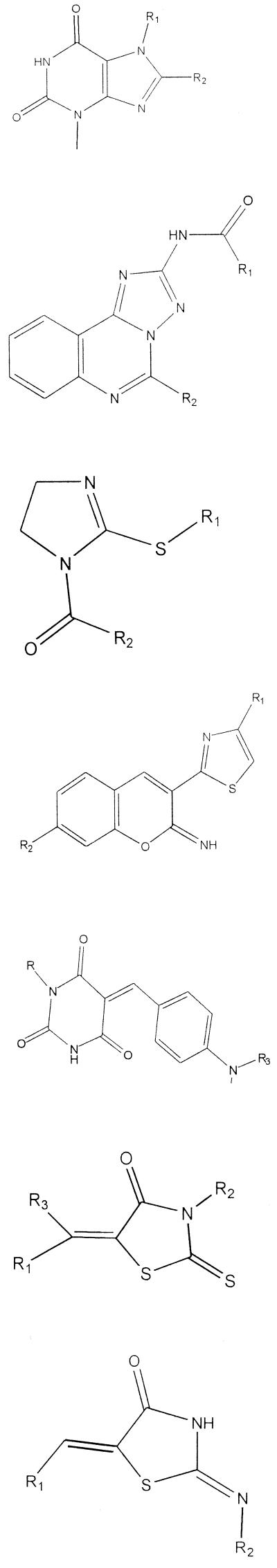

Use of the microtiter plate-based assay to search for inhibitors.

The microtiter plate assay can be used to screen for inhibitors among drug candidates obtained in microtiter plate format. The slope of the oxidation of NADPH of wells with compounds is compared to that of the no-compound control and converted to percent inhibition by the formula (1 − mwith inhibitor/mwithout inhibitor) × 100. Thus, a perfect inhibitor would have a slope of 0 and 100% inhibition; a compound that showed no inhibition would have the same slope as the no-compound control and have an inhibition of 0%. The compound dTDP is run as a positive inhibitor control with typically 80% inhibition at 3 mM.

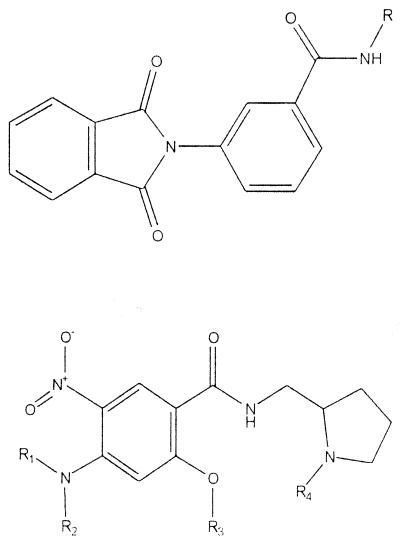

To test the robustness and practicality of the assay, 8,000 compounds supplied in microtiter plate format (Nanosyn, Tucson, Ariz.) were assayed. In terms of solubility and permeability, the Nanosyn compounds were selected based on the Lipinski “rule of 5,” specifically, for molecular weight, log P values, hydrogen bond donors, and hydrogen bond acceptors (27). With respect to these four criteria, 89% of the compounds of the library were in the “drug” category for all four criteria, and 9% of the compounds met three of the four criteria. The compounds were also selected for the presence of “drug-like” functional groups (14) and the lack of reactive groups such as aldehydes. The library was screened at a concentration of 10 μM. Eighteen compounds that reproducibly inhibited the conversion of dTDP-glucose to dTDP-rhamnose 60% or more were identified among them. Two-milligram samples of each of these 18 compounds were then obtained from Nanosyn, and the activities were reassayed using the nonplated compounds. As is often the case when going from microtiter plates back to original compounds, not all compounds were active; in this case 11 of the 18 compounds showed inhibition in the microtiter plate assay using all three enzymes. These 11 compounds were then assayed for their ability to inhibit RmlB using the colorimetric assay (23). They were also assayed for the ability to inhibit RmlC and RmlD individually by using a modification (see Materials and Methods) of the method described by Graninger et al. (19) (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Finally, 10 of the 11 compounds were assayed for their ability to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis in culture (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibitors of Rml enzymes and their activities against M. tuberculosis in culture

| Structure | % Inhibition of:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | RmlB, -C, and -D | RmlB | RmlC | RmlD | Enzyme(s) inhibited | MIC (μg/ml) | |

|

1014 | 61 | −2 | −12 | 18 | Da | >128 |

| 6808 | 77 | 4 | −13 | 40 | Da | >128 | |

| 3763 | 71 | 70 | 28 | 64 | B, D | 128 | |

| 5192 | 76 | 23 | 9 | 58 | D | Not tested | |

| 4809 | 84 | 29 | 50 | 55 | C, D | 128 | |

| 5372 | 81 | 57 | 59 | 74 | B, C, D | 16 | |

| 6429 | 97 | 52 | 29 | 97 | B, D | 64 | |

| 6432 | 78 | 45 | 20 | 39 | B, D | >128 | |

| 2943 | 87 | 22 | 68 | 99 | C, D | >128 | |

|

6984 | 103 | 60 | −5 | 48 | B, D | >128 |

| 6818 | 86 | −23 | −8 | 31 | Da | >128 | |

In the assay for the specific inhibition of RmlD, the procedure necessarily results in much larger amounts of dTDP-6-deoxy-4-lyxo-hexulose (the substrate for RmlD) than in the assay for all three enzymes together. Thus, the enzyme inhibited is tentatively considered RmlD even though the values for inhibition of RmlD are low.

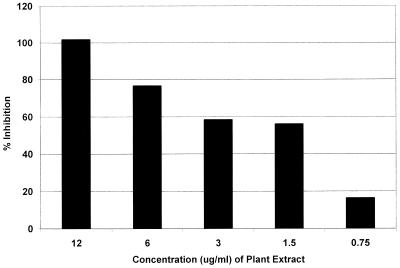

Crude extracts made from Peruvian medicinal plants identified by an indigenous Aguaruna tribe were extracted in 95% ethanol, detannified, and tested in DMSO in a whole-cell assay of M. tuberculosis using the virulent human strain H37Rv (9, 50). Of the 492 extracts tested, 26% inhibited the growth of whole M. tuberculosis cells at 100 μg/ml. The ability of the enzyme assay to analyze such extracts was then tested. Sixty of the extracts active against whole M. tuberculosis cells were screened for their ability to inhibit the conversion of dTDP-Glc to dTDP-Rha. Two were quite active, and the inhibition activity of one, from a liana whose resin was applied by indigenous people to heal wounds due to cuts, is shown at different concentrations in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Dilution assay of the inhibition of the conversion of dTDP-Rha from dTDP-Glc by an extract from a Peruvian liana known to inhibit the growth of M. tuberculosis. After identification of the extract's inhibition activity, it was run at serial dilutions and shown to be active at a concentrations below 1.5 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

Identification of dTDP-Rha-synthesizing genes.

Only one copy each of rmlC and rmlD is present in the M. tuberculosis genome (8), and we have shown previously that the genes do in fact encode the expected enzymes (22, 46). The situation for rmlA is now also seen to be unambiguous, as only two candidate genes are present and we have clearly shown the function of Rv0334 to be encoding RmlA (26) and that of Rv3264c to be encoding ManB (this study). The situation is not as clear-cut for the rmlB gene. Rv3464 clearly encodes RmlB, as active enzyme can be expressed from it. Rv3634c encodes a protein with homology to RmlB, but the fact that its N-terminal sequence is nearly identical to that of UDP-galactose epimerase (GalE) from M. smegmatis (51) indicates that this gene encodes the GalE protein. Two other possible candidates, Rv3784 and Rv3468c, have been identified in the genome sequence (8); our data suggest that these genes do not encode RmlB, because they can be expressed as soluble proteins that do not show dTDP-glucose dehydratase (RmlB) activity. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the soluble proteins were merely inactive RmlB. Therefore, it is most likely that only one isoform of RmlB is present in M. tuberculosis, but this has not yet been established unequivocally.

Genome organization of dTDP-Rha-synthesizing genes.

In most other organisms, such as E. coli, rmlABCD are on a single operon, often in the order B, D, A, C (24, 40, 43, 47). However, from the results above and the genome sequence (8), it is clear that in M. tuberculosis the four genes responsible for dTDP-Rha formation are in three different loci. Thus, rmlA (Rv0334) is separate from all the other genes involved in rhamnose metabolism and appears to be the fourth gene in an operon where the functions of the proteins encoded by the other three genes are not known. The genes rmlB and rmlC (Rv3464 and Rv3465) are the second and third genes in a complex operon with perhaps five genes, where the last two genes are part of an insertion sequence (25) and the first gene encodes a protein with an unknown function. Finally, rmlD (Rv3266c) is the first gene of a three-gene operon. In this case the second gene is wbbL, encoding rhamnosyl transferase, and the third is manB (designated rmlA-2 in the genome sequence [8]), whose function is revealed in this report. There is some logic in the coordination of expression of manB with the rhamnose genes, as manB is needed for all mannosyl glycolipids (4) and polysaccharides (7), which, like rhamnosyl residues, are an important part of the mycobacterium envelope (30). The finding, however, that the rml genes are so scattered throughout the genome is surprising.

Comparison of rhamnosyl formation enzyme genes in M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae.

It is of interest to compare the rhamnosyl-forming enzymes in M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. The sequencing of the M. leprae genome is just being completed. The genome of M. leprae is smaller than that of M. tuberculosis, many potential ORFs are degraded, and half of the DNA is noncoding (20). Since the cell wall AGs of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis are nearly identical (10), it stands to reason that the genes involving rhamnosyl formation enzymes should be amongst the intact genes found in the M. leprae genome. BLAST searches of the nearly completed M. leprae genome confirm that this is indeed true; rmlABCD and wbbL are all five intact in M. leprae, and, interestingly, the grouping of the genes in the various operons is the same in both mycobacteria, although the arrangement and orientation of the operons themselves along the genome are different. This result is consistent with the essential function of rhamnosyl residues in mycobacteria.

Targeting dTDP-Rha formation in M. tuberculosis.

Targeting dTDP-Rha formation in M. tuberculosis has much to recommend it. Four enzymes are involved, and all of them catalyze reactions that are not found in humans (although the formation of UDP-glucose from α-d-glucose-1-phosphate and UTP is quite homologous to the formation of dTDP-Glc catalyzed by RmlA). The enzymes are soluble and can be readily prepared in large amounts. X-ray structural analysis is becoming available for the Salmonella homologs of these enzymes (1, 15–17), with efforts proceeding on the M. tuberculosis versions. Mechanisms of action and kinetic parameters are becoming known (18, 19, 34, 42, 45). The rhamnosyl transferase, WbbL, which uses dTDP-Rha as its substrate to insert the rhamnosyl residue in the cell wall, is essential for growth, as shown by the fact that an M. smegmatis TS mutant of WbbL differing in a single amino acid (GenBank accession numbers AAF04375 and AAF04376) do not grow at the nonpermissive temperature (Mills et al., unpublished). There is no known way in nature to form dTDP-Rha other than by these enzymes. Finally, three of the enzymes (RmlB, -C, and -D) are readily assayed together by monitoring the oxidation of NADPH, and this assay is readily adaptable to microtiter plates (Fig. 3) and can be used to identify inhibitors (Table 1 and Fig. 3 and 4).

Use of the microtiter plate assay.

The microtiter plate assay for RmlB, RmlC, and RmlD described above has the advantage of screening for inhibitors of three key enzymes at the same time. In practice we have found that preparing the three enzymes from E. coli in sufficient purity for the assay is straightforward but does require some care in adequately washing nickel columns when they are used in the purification. Although the experiments reported herein were done using a non-His-tagged version of RmlB, for convenience His-tagged RmlB from M. tuberculosis can readily be cloned (see Materials and Methods) and purified by standard methods after expression in E. coli and used successfully in the assay (data not shown). In identifying active inhibitors we selected compounds that inhibited the formation of dTDP-Rha more than 60%. Compounds showing activity were then retested, and generally the percent inhibition was reproducible to roughly ±20%, allowing a clear separation of active and inactive inhibitors under the conditions of the assay.

The most important finding of the present investigation is the fact that the Rml enzyme assay is sufficiently robust to uncover potential enzyme inhibitors as a starting place for continued analysis. Most compounds selected by the screen were active against more than a single enzyme. Given the structural similarities of the substrates for all three enzymes, this is perhaps not surprising. It was interesting that three of the eleven compounds (5372, 6429, and 6432) had a rhodanine core structure and a fourth (2943) had a core structure very similar to that of rhodanine. There were at least six other compounds in the Nanosyn library that had rhodanine rings but were not active in the enzyme assay, suggesting some very preliminary structure-activity relationships. It was also encouraging that four of the eleven active compounds identified in this preliminary study inhibited the growth of M. tuberculosis in culture (albeit usually at high concentrations [Table 1]). Clearly, more work must be done to show that such compounds actually affect growth of M. tuberculosis via inhibition of the rhamnosyl enzymes. Also, much work remains to identify further classes of active compounds and to determine which molecules have appropriate properties for further development. On a somewhat different track, compounds identified as enzyme inhibitors are candidates for cocrystallization with the enzymes they inhibit to reveal useful binding structures, regardless of their other properties.

The assay described here should be suitable for screening very large numbers of compounds. Although it was performed here in a 96-well format, there is no reason not to use 384-well plates or even plates containing higher number of wells, as only the OD340 needs to be monitored. The most expensive reagent is the dTDP-glucose, and the amounts of it can be decreased if a smaller overall change in OD can be tolerated (as reported here, the utilization of all the dTDP-glucose will result an OD drop of about 0.3 units). Small well sizes will also allow the use of less dTDP-glucose and will require less enzyme as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds provided through the Public Health Service (NIAID, NIH; AI-33706) and through the National Cooperative Drug Discovery Group program (NIAID, NIH; U19 AI 40972 and P01 AI 46393).

We gratefully thank John Belisle and Barbara Covert for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry sequencing of RmlB and Amber Safford, Angela Richards, and Mark Pilgard for skilled technical assistance. We also thank Sandeep Shankar for valuable discussions and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allard S T M, Giraud M-F, Whitfield C, Messner P, Naismith J H. The purification, crystallization and structural elucidation of dTDP-D-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (RmlB), the second enzyme of the dTDP-l- rhamnose synthesis pathway from Salmonella entericaserovar typhimurium. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56(Pt. 2):222–225. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry C E., III New horizons in the treatment of tuberculosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besra G S, Brennan P J. The mycobacterial cell envelope: a target for novel drugs against tuberculosis. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49(Suppl. 1):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan P J, Ballou C E. Biosynthesis of mannophosphoinositides by Mycobacterium phlei. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:2975–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan P J, Nikaido H. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:29–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chase M. New, virulent forms of tuberculosis spur concerns world-wide. The Wall Street Journal. 1999;1999(Dec. 17):B1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee D, Khoo K H. Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan: an extraordinary lipoheteroglycan with profound physiological effects. Glycobiology. 1998;8:113–120. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosisfrom the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins L A, Franzblau S G. Microplate Alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antibiot Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daffe M, McNeil M, Brennan P J. Major structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactans of Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus, and Nocardiaspp. Carbohydr Res. 1993;249:383–398. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84102-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng L, Mikusova K, Robuck K G, Scherman M, Brennan P J, McNeil M. Recognition of multiple effects of ethambutol on the metabolism of the mycobacterial cell envelope. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:694–701. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enarson D A, Murray J F. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. In: Rom W N, Garay S, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Company; 1996. pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel O, Ashwell G. Biological mechanisms involved in the formation of deoxysugars. I. Preparation of thymidine diphosphate glucose labeled specifically in carbon 3. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:4123–4127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghose A K, Viswanadhan V N, Wendoloski J J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J Comb Chem. 1999;1:55–68. doi: 10.1021/cc9800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giraud M-F, Gordon F M, Whitfield C, Messner P, McMahon S A, Naismith J H. Purification, crystallization and preliminary structural studies of dTDP-6-deoxy-d-xylo-4-hexulose 3,5-epimerase (RmlC), the third enzyme of the dTDP-l-rhamnose synthesis pathway, from Salmonella entericaserovar typhimurium. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:706–708. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998015042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giraud M-F, Leonard G A, Field R A, Berlind C, Naismith J H. RmlC, the third enzyme of dTDP-l-rhamnose pathway, is a new class of epimerase. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:398–402. doi: 10.1038/75178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giraud M-F, McMiken H J, Leonard G A, Messner P, Whitfield C, Naismith J H. Overexpression, purification, crystallization and preliminary structural study of dTDP-6-deoxy-l-lyxo-4-hexulose reductase (RmlD), the fourth enzyme of the dTDP-l-rhamnose synthesis pathway, from Salmonella entericaserovar typhimurium. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55(Pt 12):2043–2046. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999012251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaser L, Ward L. Intramolecular hydrogen transfer catalyzed by UDP-d-glucose 4′- epimerase from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;198:613–615. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(70)90141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graninger M, Nidetzky B, Heinrichs D E, Whitfield C, Messner P. Characterization of dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase and dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose reductase, required for dTDP-l-rhamnose biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimuriumLT2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25069–25077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagmann M. Intimate portraits of bacterial nemeses. Science. 2000;288:800–801. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harkin T J, Harris H W. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. In: Rom W N, Garay S, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Company; 1996. pp. 843–850. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoang T T, Ma Y F, Stern R J, McNeil M R, Schweizer H P. Construction and use of low-copy number T7 expression vectors for purification of problem proteins: purification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RmlD and Pseudomonas aeruginosaLasI and RhlI proteins, and functional analysis of purified RhlI. Gene. 1999;237:361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornfeld S, Glaser L. The enzymatic synthesis of thymidine-linked sugars. I. Thymidine diphosphate glucose. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1791–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S J, Romana L K, Reeves P R. Sequence and structural analysis of the rfb (O antigen) gene cluster from a group C1 Salmonella entericastrain. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1843–1855. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee T Y, Lee T J, Belisle J T, Brennan P J, Kim S K. A novel repeat sequence specific to Mycobacterium tuberculosiscomplex and its implications. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1997;78:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin E C C. Dissimilatory pathways for sugars, polyols, and carboxylates. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 244–284. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipinski C A, Lombardo F, Dominy B W, Feeney P J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Delivery Syst. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Mills J A, Belisle J T, Vissa V, Howell M, Bowlin K, Scherman M S, McNeil M. Drug targeting rhamnose biosynthesis in mycobacteria: determination of the pathway for rhamnose biosynthesis in mycobacteria and cloning, sequencing, expressing and determining the genetic organization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene encoding α-d-glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase. Microbiology. 1997;143:937–945. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeil M. Target preclinical drug development for Mycobacterium avium complex: a biochemical approach. In: Korvick J A, Benson C A, editors. Mycobacterium avium-complex infection. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1996. pp. 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil M, Besra G S, Brennan P J. Chemistry of the mycobacterial cell wall. In: Rom W N, Garay S M, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Company; 1996. pp. 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNeil M R. Arabinogalactan in mycobacteria: structure, biosynthesis, and genetics. In: Goldberg J B, editor. Genetics of bacterial polysaccharides. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1999. pp. 207–223. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melo A, Elliott W H, Glaser L. The mechanism of 6-deoxyhexose synthesis. I. Intramolecular hydrogen transfer catalyzed by deoxythymidine diphosphate d-glucose oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:1467–1474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran N. W. H. O. issues another gloomy tuberculosis report. Nat Med. 1996;2:377–377. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naundorf A, Klaffke W. Substrate specificity of native dTDP-d-glucose-4,6-dehydratase: chemo-enzymatic syntheses of artificial and naturally occurring deoxy sugars. Carbohydr Res. 1996;285:141–150. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(96)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuhard J, Thomassen E. Altered deoxyribonucleotide pools in P2 eductants of Escherichia coli K-12 due to deletion of the dcdgene. J Bacteriol. 1976;126:999–1001. doi: 10.1128/jb.126.2.999-1001.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikaido H, Nikaido K, Rapis A M C. Biosynthesis of thymidine diphosphate l-rhamnose in Escherichia coliK-12. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1965;111:548–551. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(65)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ning B, Elbein A D. Purification and properties of mycobacterial GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;362:339–345. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S H, Pastuszak I, Drake R, Elbein A D. Purification to apparent homogeneity and properties of pig kidney l-fucose kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5685–5691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pastuszak I, Ketchum C, Hermanson G, Sjoberg E J, Drake R, Elbein A D. GDP-l-fucose pyrophosphorylase. Purification, cDNA cloning, and properties of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30165–30174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajakumar K, Jost B H, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Yoshikawa M, Adler B. Nucleotide sequence of the rhamnose biosynthetic operon of Shigella flexneri2a and role of lipopolysaccharide in virulence. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2362–2373. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2362-2373.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramaswamy S, Musser J M. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:3–29. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramaswamy S V, Amin A G, Goksel S, Stager C E, Dou S-J, El Sahly H, Moghazeh S L, Kreiswirth B N, Musser J M. Molecular genetic analysis of nucleotide polymorphisms associated with ethambutol resistance in human isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:326–336. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.326-336.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reeves P R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rouhi A M. Tuberculosis: a tough adversary. Chem Eng News. 1999;77:52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell R N, Liu H W. Stereochemical and mechanistic studies of CDP-D-glucose oxidoreductase isolated from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7777–7778. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stern R J, Lee T Y, Lee T J, Yan W, Scherman M S, Vissa V D, Kim S K, Wanner B L, McNeil M R. Conversion of dTDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose to free dTDP-4-keto-rhamnose by the rmlC gene products of Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology. 1999;145:663–671. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-3-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson G, Andrianopoulos K, Hobbs M, Reeves P R. Organization of the Escherichia coliK-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4885-4893.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevenson G, Neal B, Liu D, Hobbs M, Packer N H, Batley M, Redmond J W, Lindquist L, Reeves P R. Structure of the O antigen of Escherichia coli K-12 and the sequence of its rfbgene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4144–4156. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4144-4156.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takayama K, Kilburn J O. Inhibition of synthesis of arabinogalactan by ethambutol in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1493–1499. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Timmermann B N, Wachter G, Valcic S, Hutchinson B, Casler C, Henzel J, Ram S, Currim F, Manak R, Franzblau S, Maiese W, Galanis D, Suarez E, Fortunato R, Saavedra E, Bye R, Mata R, Montenegro G. The Latin American ICBG: the first five years. Pharm Biol. 2000;37(Suppl.):35–54. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weston A, Stern R J, Lee R E, Nassau P M, Monsey D, Martin S L, Scherman M S, Besra G S, Duncan K, McNeil M R. Biosynthetic origin of mycobacterial cell wall galactofuranosyl residues. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winder F G. Mode of action of the antimycobacterial agents and associated aspects of the molecular biology of the mycobacteria. In: Ratledge C, Standford J, editors. The biology of the mycobacteria. Vol. 1. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 354–442. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarkowsky H, Glaser L. The mechanism of 6-deoxyhexose synthesis. III. Purification of deoxythymidine diphosphate-glucose oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:4750–4756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]