Abstract

RWJ-54428 (MC-02,479) is a new cephalosporin with a high level of activity against gram-positive bacteria. In a broth microdilution susceptibility test against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), RWJ-54428 was as active as vancomycin, with an MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited (MIC90) of 2 μg/ml. For coagulase-negative staphylococci, RWJ-54428 was 32 times more active than imipenem, with an MIC90 of 2 μg/ml. RWJ-54428 was active against S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolates with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides (RWJ-54428 MIC range, ≤0.0625 to 1 μg/ml). RWJ-54428 was eight times more potent than methicillin and cefotaxime against methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml). For ampicillin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis (including vancomycin-resistant and high-level aminoglycoside-resistant strains), RWJ-54428 had an MIC90 of 0.125 μg/ml. RWJ-54428 was also active against Enterococcus faecium, including vancomycin-, gentamicin-, and ciprofloxacin-resistant strains. The potency against enterococci correlated with ampicillin susceptibility; RWJ-54428 MICs ranged between ≤0.0625 and 1 μg/ml for ampicillin-susceptible strains and 0.125 and 8 μg/ml for ampicillin-resistant strains. RWJ-54428 was more active than penicillin G and cefotaxime against penicillin-resistant, -intermediate, and -susceptible strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC90s, 0.25, 0.125, and ≤0.0625 μg/ml, respectively). RWJ-54428 was only marginally active against most gram-negative bacteria; however, significant activity was observed against Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis (MIC90s, 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively). This survey of the susceptibilities of more than 1,000 multidrug-resistant gram-positive isolates to RWJ-54428 indicates that this new cephalosporin has the potential to be useful in the treatment of infections due to gram-positive bacteria, including strains resistant to currently available antimicrobials.

Multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria have become an increasing problem for the management of serious infections (13). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci (MRCoNS) represent a challenge in hospitals and are now also established in the community (3). Staphylococci producing a β-lactamase capable of hydrolyzing penicillins were isolated soon after the introduction of these antibiotics (10). To overcome this resistance problem, semisynthetic penicillins resistant to staphylococcal β-lactamases, such as methicillin, were introduced, but it did not take long for the strains with resistance to these agents to surface (1; M. P. Jevons, Letter, Br. Med. J. i:124–125, 1961; G. N. Rolinson, Letter, Br. Med. J. i:125–126, 1961). The genetic determinant of methicillin resistance has been identified as mec DNA, which is a 30- to 50-kb region of foreign DNA found only in methicillin-resistant staphylococci, possibly acquired by transposition from Staphylococcus sciuri (22). This DNA region contains the mecA gene, which encodes penicillin-binding protein 2a, which has a low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics (3). The wide distribution of methicillin resistance has led to a marked increase in the use of vancomycin; however, the existence of MRSA and MRCoNS strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in several regions of the world is now of great concern (14, 20). Such multidrug-resistant strains may become a significant threat to public health, and new agents active against MRSA and MRCoNS are needed.

Penicillin resistance can now be found in 25% of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and viridans group streptococci worldwide (9). In addition to resistance to penicillin, many of these strains are also resistant to macrolides. Resistance to penicillins and cephalosporins in streptococci is mediated by target-site mutations in penicillin-binding proteins. In S. pneumoniae, mosaic genes encoding altered penicillin-binding proteins mediate resistance to penicillin and related antibiotics (6, 21). Nonpneumococcal streptococci have also become increasingly prevalent and are often the cause of fatal bacteremia in immunocompromised patients. As many as 9% of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci in the United States are resistant to penicillin G. More importantly, viridans group streptococci that are not susceptible to penicillin G are often also resistant to ceftriaxone or erythromycin, or to both antibiotics (19).

Enterococci represent a particular clinical challenge because of their high level of intrinsic resistance to antibiotics (12, 17). They are tolerant to most cell wall-active agents and are not readily killed by β-lactam antibiotics and vancomycin. Some enterococci have also acquired genes that confer a high level of resistance to most antibacterial agents (15). In a recent survey of isolates from the United States, vancomycin resistance occurred in 3.5% of Enterococcus faecalis isolates and 53% of Enterococcus faecium isolates. High-level resistance to gentamicin was encountered in 33 and 43% of E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates, respectively (18).

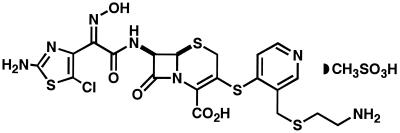

Several years ago, we initiated a program to design new cephalosporins with optimal activity against multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria (F. Malouin, C. Chan, S. Bond, S. Chamberland, and V. J. Lee, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-177, 1997). The details concerning the discovery of the RWJ-54428 (MC-02,479; Fig. 1) and its structure-activity relationship and potency against a limited number of organisms have been described elsewhere (7). This report describes in detail the in vitro activity of this agent against staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci, as well as against Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and other gram-negative bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of RWJ-54428 (MC-02,479).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 671 clinical isolates of staphylococci, 164 clinical isolates of streptococci, and 212 clinical isolates of enterococci obtained from various geographical locations within the United States and abroad were used in the studies described here. These representative clinical isolates were collected at various hospitals between 1993 and 1998. Thirty-one clinical isolates of H. influenzae were included in this study. These isolates were collected during the late 1980s in the United States and Canada and included serotype a, b, c, d, e, and f isolates and nonserotypeable isolates. Seventeen clinical isolates of M. catarrhalis, collected during the 1980s in the United States and Canada, were included in the study. Nine of these isolates were β-lactamase positive. A total of 111 clinical isolates of gram-negative bacteria, including multidrug-resistant strains of the families Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Neisseriaceae and other nonaffiliated gram-negative bacteria, were studied.

To further characterize the activity of RWJ-54428 against MRSA, a survey of genotypically well-characterized isolates was also conducted. These included 64 MRSA strains representing 40 staphylococcal protein A genotypes and 17 different coagulase A genotypes. The most common protein A genotypes found in the United States were represented by more than one isolate. Activity against representative strains of staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides was also determined.

Antibiotics.

RWJ-54428 was supplied as the monomethanesulfonate. A stock solution of 2 mg of active RWJ-54428 per ml was prepared in a 1:1 solution of dimethyl sulfoxide-sterile water. Commercially available antibiotics were obtained from various sources: amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, erythromycin, gentamicin, methicillin, penicillin G, and vancomycin were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. The other antibiotics were purchased or obtained from their respective manufacturers: azithromycin, Pfizer; cefepime, Bristol Myers-Squibb Co.; ceftazidime, Glaxo Pharmaceuticals; ciprofloxacin, Bayer; imipenem-cilastatin (Primaxin), Merck & Co.; levofloxacin, Daiichi Pharmaceuticals; and teicoplanin, Advantis. Amoxicillin (Sigma) was also used in combination with clavulanate (SmithKline Beecham) at a 2:1 ratio. The potency of each antibiotic powder was considered for preparation of stock solutions. All antibiotics except imipenem and erythromycin were prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/ml in sterile water. Imipenem was prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in sterile water. Erythromycin was prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/ml in ethanol. Stock solutions of all antibiotics except clavulanic acid were aliquoted and kept frozen at −80°C; clavulanic acid was prepared daily. Each aliquot was rapidly thawed and used only once. Antibiotics were prepared at a concentration equivalent to twofold the highest desired final concentration. Antibiotics were then diluted directly in 96-well microtiter plates by serial twofold dilution with a multichannel pipette.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility tests were performed by a broth microdilution assay according to NCCLS reference methods (16), with the following specifications: testing of beta-lactams against all methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains, and MRSA strains, and coagulase-negative staphylococci tested was performed in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 2% NaCl. The incubation period was 24 h at 35°C. The supplemental NaCl was excluded when non-beta-lactam drugs were tested. The MICs of the drugs tested for E. faecium and E. faecalis were determined in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth incubated at 35°C for 24 h. The MICs of the drugs for all streptococci were determined in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 2.5% lysed horse blood (Remel). All incubation periods were 24 h at 35°C. The MICs of the drugs tested for H. influenzae were determined in Haemophilus Test Medium (Remel) supplemented with 2% Fildes enrichment (Remel). All incubations were for 24 h at 35°C. For all other gram-negative bacteria, MICs were determined in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth following incubation at 35°C for 20 h. The microtiter plates were read with a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 650 nm as well as by visual observation with a reading mirror.

RESULTS

MSSA (n = 167).

On the basis of the MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited (MIC50s), and the MIC90s, RWJ-54428 was eightfold more active than methicillin and cefotaxime and was as potent as imipenem against MSSA isolates (Table 1). The new cephalosporin was also twofold more active than vancomycin and teicoplanin against the MSSA isolates tested. The results were similar for 18 ciprofloxacin-resistant MSSA isolates, indicating that resistance to quinolones was not associated with decreased susceptibility to RWJ-54428 (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

In vitro activity of RWJ-54428 against staphylococci

| Organism | No. of isolates | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |||

| S. aureus | |||||

| Methicillin susceptible | 165 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| 167 | Methicillina | 0.5–8 | 2 | 4 | |

| 167 | Cefotaxime | 0.5–>128 | 2 | 4 | |

| 167 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–4 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | |

| 167 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–64 | 0.5 | 4 | |

| 167 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | 0.25 | >32 | |

| 167 | Vancomycin | 0.25–4 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 167 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.0625–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| Methicillin resistant | 259 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–4 | 1 | 2 |

| 259 | Methicillina | 16–>512 | 256 | >512 | |

| 259 | Cefotaxime | 2–>512 | 512 | >512 | |

| 259 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–>256 | 16 | 64 | |

| 259 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–>256 | 8 | 64 | |

| 259 | Erythromycin | 0.125–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 259 | Vancomycin | 0.25–8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 259 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.0625–32 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| Methicillin resistant, genotypically characterized subsetb | 64 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125-2 | 1 | 2 |

| 64 | Methicillina | 16–>512 | 256 | >512 | |

| 64 | Oxacillin | 8–>512 | 128 | 512 | |

| 64 | Cefotaxime | 4–>512 | 512 | >512 | |

| 64 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–>256 | 8 | 64 | |

| 64 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–256 | 8 | 128 | |

| 64 | Erythromycin | 0.125–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 64 | Vancomycin | 0.25–4 | 1 | 2 | |

| 64 | Teicoplanin | 0.125–32 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| All MRCoNS | 89 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–4 | 0.5 | 2 |

| 89 | Methicillina | 16–>512 | 512 | >512 | |

| 89 | Cefotaxime | 2–>512 | 256 | >512 | |

| 89 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–128 | 32 | 128 | |

| 89 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–256 | ≤0.5 | 64 | |

| 78 | Erythromycin | 0.125–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 89 | Vancomycin | 0.25–8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 89 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | 4 | 32 | |

| S. epidermidis | |||||

| Methicillin susceptible | 88 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.25 | ≤0.0625 | 0.25 |

| 88 | Methicillina | ≤1–8 | 2 | 8 | |

| 88 | Cefotaxime | ≤1–32 | ≤1 | 4 | |

| 88 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–8 | ≤0.5 | 1 | |

| 88 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–64 | ≤0.5 | 8 | |

| 88 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 88 | Vancomycin | 0.25–8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 88 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–64 | 1 | 4 | |

| Methicillin resistant | 48 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–4 | 0.25 | 1 |

| 48 | Methicillina | 16–>512 | 256 | >512 | |

| 48 | Cefotaxime | 2–>512 | 64 | >512 | |

| 48 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–64 | 8 | 64 | |

| 48 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–64 | 4 | 64 | |

| 48 | Erythromycin | 0.125–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 48 | Vancomycin | 0.25–8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 48 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–32 | 2 | 8 | |

| S. haemolyticus | |||||

| Methicillin susceptible | 20 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 20 | Methicillina | ≤1–8 | ≤1 | 4 | |

| 20 | Cefotaxime | ≤1–4 | ≤1 | 4 | |

| 20 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | |

| 20 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–8 | ≤0.5 | 1 | |

| 20 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | 0.125 | >32 | |

| 20 | Vancomycin | 0.25–2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 20 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–16 | 2 | 8 | |

| Methicillin resistant | 32 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–2 | 2 | 2 |

| 32 | Methicillina | 16–>512 | >512 | >512 | |

| 32 | Cefotaxime | 16–>512 | 512 | >512 | |

| 32 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–128 | 128 | 128 | |

| 32 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–256 | ≤0.5 | 64 | |

| 32 | Erythromycin | 0.125–>32 | >32 | >32 | |

| 32 | Vancomycin | 0.25–8 | 2 | 4 | |

| 32 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | 8 | 64 | |

| S. hominis | |||||

| Methicillin susceptible | 36 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.25 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 |

| 36 | Methicillina | ≤1–8 | ≤1 | ≤1 | |

| 36 | Cefotaxime | ≤1–16 | ≤1 | 4 | |

| 36 | Imipenem | ≤0.5–4 | ≤0.5 | 2 | |

| 36 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| 36 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–8 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 36 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–4 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | |

| Methicillin resistant | 9 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.5 | 0.25 | |

| 9 | Methicillina | 128–>512 | 512 | ||

| 9 | Cefotaxime | 4–>512 | 32 | ||

| 9 | Imipenem | 2–64 | 32 | ||

| 9 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–8 | ≤0.5 | ||

| 9 | Vancomycin | 0.5–2 | 0.5 | ||

| 9 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–8 | ≤0.125 | ||

| S. saprophyticus, methicillin | 12 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| susceptible | 12 | Methicillina | 2–4 | 2 | 4 |

| 12 | Cefotaxime | ≤1–4 | 2 | 4 | |

| 12 | Imipenem | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | |

| 12 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | |

| 12 | Vancomycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| 12 | Teicoplanin | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | 1 | |

MRSA (n = 259).

RWJ-54428 was also found to be very active against a large group of MRSA isolates (Table 1). Among all MRSA strains surveyed, the highest MIC of RWJ-54428 observed was 4 μg/ml (for one strain), and the MIC50 and MIC90 were 1 and 2 μg/ml, respectively. RWJ-54428 was 32-fold more active than imipenem and >256-fold more active than methicillin and cefotaxime against these MRSA isolates. Results were similar for a subset of 160 ciprofloxacin-resistant MRSA isolates, indicating, as expected, that resistance to this agent was not associated with decreased susceptibility to RWJ-54428 (data not shown). The results of a survey of the susceptibilities of genotypically characterized clinical isolates of MRSA is shown in Table 1. RWJ-54428 was highly active against this sample of genetically diverse MRSA strains from North America, Europe, and Japan, with an MIC50 and an MIC90 of 1 and 2 μg/ml, respectively. The potency of RWJ-54428 was similar to those of vancomycin and teicoplanin. All strains were inhibited by 2 μg of RWJ-54428 per ml, whereas the strains were inhibited by 4 and 32 μg of vancomycin and teicoplanin per ml, respectively. All isolates were susceptible to RWJ-54428, despite high levels of resistance to other beta-lactam antibiotics (methicillin, cefotaxime, and imipenem), ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin.

MRCoNS (n = 89).

The susceptibility of MRCoNS to the drugs tested is shown in Table 1. RWJ-54428 was the most active agent against MRCoNS. In addition to resistance to conventional beta-lactam antibiotics, most of these isolates were highly resistant to ciprofloxacin and erythromycin.

Staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics.

A group of five staphylococci, including two S. aureus strains, two Staphylococcus epidermidis strains, and one Staphylococcus haemolyticus strain, with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics was tested (Table 2). For these isolates, the vancomycin MIC was 8 μg/ml and teicoplanin MICs ranged from 4 to 32 μg/ml. These isolates were readily inhibited by RWJ-54428, with MICs ranging from ≤0.0625 to 1 μg/ml.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activity of RWJ-54428 against staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIP-5836b | HIP-5827b | HIP-4645c | HIP-4680c | HIP-5979d | |

| RWJ-54428 | 0.5 | 1 | ≤0.0625 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Methicillin | 64 | >512 | 256 | 256 | >512 |

| Oxacillin | 4 | 256 | 64 | 64 | 256 |

| Cefotaxime | 8 | >512 | 64 | 16 | NDe |

| Imipenem | 2 | 64 | 16 | 16 | 64 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 32 | 128 | ≤0.5 | 64 | ND |

| Erythromycin | >32 | >32 | ND | ND | ND |

| Vancomycina | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Teicoplanin | 4 | 16 | 4 | 32 | 16 |

According to the NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (16), intermediate susceptibility to vancomycin is a vancomycin MIC of 8 to 16 μg/ml.

Vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus.

Vancomycin-intermediate S. epidermidis.

Vancomycin-intermediate S. haemolyticus.

ND, not done.

S. pneumoniae.

RWJ-54428 was highly active against S. pneumoniae, including penicillin-resistant pneumococci (PRSP). For 34 PRSP isolates, the MIC90 of RWJ-54428 was 0.25 μg/ml, with the highest MIC being 0.5 μg/ml. On the basis of the MIC90s, RWJ-54428 was 16-fold more potent than penicillin G and 8-fold more active than ceftriaxone or cefotaxime against these clinical isolates of PRSP. RWJ-54428 outperformed erythromycin. The potency of RWJ-54428 was equivalent to that of vancomycin against penicillin-intermediate pneumococci and PRSP (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

In vitro activity of RWJ-54428 against streptococci

| Organism | No. of isolates | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |||

| S. pneumoniae | |||||

| Penicillin susceptible | 33 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 |

| 33 | Penicillin Ga | ≤0.0625–0.125 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 33 | Ceftriaxone | ≤0.0625–0.5 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 33 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.0625–0.25 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 33 | Levofloxacin | 0.5–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 33 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | ≤0.0625 | >32 | |

| 33 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| 33 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | |

| Penicillin intermediate | 39 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.25 | ≤0.0625 | 0.125 |

| 39 | Penicillin Ga | 0.125–1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 39 | Ceftriaxone | ≤0.0625–8 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 39 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.0625–8 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 39 | Levofloxacin | 0.5–2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 39 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | ≤0.0625 | >32 | |

| 39 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| 39 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | |

| Penicillin resistant | 34 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 34 | Penicillin Ga | 2–4 | 2 | 4 | |

| 34 | Ceftriaxone | 0.5–>32 | 1 | 2 | |

| 34 | Cefotaxime | 0.5–>32 | 1 | 2 | |

| 34 | Levofloxacin | 0.25–>8 | 1 | 1 | |

| 34 | Erythromycin | ≤0.0625–>32 | ≤0.0625 | >32 | |

| 34 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–1 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | |

| 34 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–0.25 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (group A) | 13 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–0.5 | ≤0.0625 | 0.5 |

| 13 | Penicillin G | ≤0.0625–0.125 | ≤0.0625 | 0.125 | |

| 13 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.008–0.03 | ≤0.008 | 0.03 | |

| 13 | Erythromycin | 0.03–0.0625 | 0.03 | 0.0625 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (group B) | 10 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 |

| 10 | Penicillin G | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 10 | Cefotaxime | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| 10 | Erythromycin | 0.03–0.0625 | 0.03 | 0.0625 | |

| Viridans group streptococci | |||||

| Penicillin susceptible | 11 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 |

| 11 | Penicillin Gb | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 12 | Ceftriaxone | ≤0.015–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| 12 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.015–0.5 | 0.06 | 0.125 | |

| 12 | Erythromycin | ≤0.015–0.0626 | ≤0.015 | 0.03 | |

| Penicillin intermediate | 10 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 |

| 10 | Penicillin Gb | 0.25–2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 11 | Ceftriaxone | 0.125–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| 11 | Cefotaxime | 0.125–2 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| 11 | Erythromycin | ≤0.015–>32 | 1 | 32 | |

| Penicillin resistant | 12 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–2 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 12 | Penicillin Gb | 4–32 | 8 | 16 | |

| 8 | Ceftriaxone | 2–16 | 8 | ||

| 8 | Cefotaxime | 2–16 | 8 | ||

| 8 | Erythromycin | 0.25–>32 | 4 | ||

According to the NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (16), Penicillin susceptible is a penicillin MIC of ≤0.06 μg/ml, penicillin intermediate is a penicillin MIC range from 0.125 to 1 μg/ml, and penicillin resistant is a penicillin MIC of ≥2 μg/ml.

According to the NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (16), penicillin susceptible is a penicillin MIC of ≤0.125 μg/ml, penicillin intermediate is a penicillin MIC range from 0.25 to 2 μg/ml, and penicillin resistant is a penicillin MIC of ≥4 μg/ml.

Group A and group B streptococci.

Clinical isolates of group A streptococci (n = 13) were all susceptible to penicillin G, with MICs ranging from ≤0.0625 to 0.125 μg/ml (Table 3). For this same group of isolates, the RWJ-54428 MIC ranged from ≤0.0625 to 0.5 μg/ml. A total of 10 isolates of group B streptococci were found to be equally highly susceptible to penicillin and to RWJ-54428, with both drugs having MICs of ≤0.0625 μg/ml for all isolates. The 10 isolates of group B streptococci were also susceptible to cefotaxime and erythromycin (Table 3).

Viridans group streptococci.

Penicillin-susceptible viridans group streptococci were susceptible to RWJ-54428, with an MIC50 and an MIC90 of ≤0.0625 μg/ml (Table 3). RWJ-54428 was more than eightfold more active than ceftriaxone. The unique potency of RWJ-54428 against this group was best seen with penicillin-intermediate and penicillin-resistant isolates of viridans group streptococci. RWJ-54428 was 8- to 32-fold more active than penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime against penicillin-intermediate and penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci (Table 3).

Enterococci.

RWJ-54428 was found to be very active against 78 isolates of vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis, with an MIC50 and an MIC90 of 0.125 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. On the basis of the MIC90s, RWJ-54428 was 8-fold more active than vancomycin and 32-fold more active than ampicillin against vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis (Table 4). A single vancomycin-intermediate E. faecalis strain (vancomycin MIC, 8 μg/ml) was identified among the clinical isolates that we have studied. This isolate was susceptible to ampicillin and gentamicin, and the RWJ-54428 MIC for the isolate was 0.25 μg/ml. RWJ-54428 was also very potent against 11 isolates of vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis, with an MIC90 of 0.125 μg/ml (Table 4). Data for the E. faecalis strains were also analyzed according to their susceptibilities to ampicillin, regardless of their level of resistance to vancomycin. RWJ-54428 MIC50 and MIC90 were both 0.125 μg/ml for a population of 82 ampicillin-susceptible E. faecalis isolates (Table 4). For eight isolates of ampicillin-resistant E. faecalis, the range of RWJ-54428 MICs was 0.125 to 4 μg/ml. RWJ-54428 was the most active antibiotic studied against E. faecium (Table 4). Most E. faecium isolates (100 of 122 [82%]) were resistant to ampicillin, with MICs ranging from 16 to >128 μg/ml. Seventy-two percent of the ampicillin-resistant isolates were also resistant to vancomycin. For these isolates, the MICs of RWJ-54428 ranged between 1 and 8 μg/ml (MIC90, 8 μg/ml) (Table 4). RWJ-54428 was found to be potent against 22 isolates of ampicillin-susceptible E. faecium, with an MIC50 and an MIC90 of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively (Table 4). Two of these isolates were resistant to vancomycin (MIC, >64 μg/ml), with ampicillin MICs of 0.5 and 2 μg/ml, respectively, and RWJ-54428 MICs of 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. These results indicate that RWJ-54428 is active against these ampicillin-susceptible, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium isolates.

TABLE 4.

In vitro activity of RWJ-54428 against enterococci

| Organism | No. of isolates | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |||

| E. faecalis | |||||

| All isolates | 90 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–4 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 90 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–>64 | 2 | >64 | |

| 90 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | ≤0.125 | 4 | |

| 90 | Ampicillin | ≤0.25–128 | 1 | 8 | |

| 90 | Gentamicin | ≤1–>512 | 32 | >512 | |

| 90 | Erythromycin | ≤0.125–>64 | 16 | >64 | |

| 90 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–>128 | 1 | 64 | |

| Vancomycin susceptible | 78 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–4 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 78 | Vancomycina | ≤0.125–4 | 1 | 2 | |

| 78 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | |

| 78 | Ampicillin | ≤0.25–128 | 1 | 8 | |

| 78 | Gentamicin | ≤1–>512 | 16 | >512 | |

| 78 | Erythromycin | ≤0.125–>64 | 8 | >64 | |

| 78 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–>128 | 1 | 64 | |

| Vancomycin resistant | 11 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–2 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| 11 | Vancomycina | 64–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 11 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | 64 | >64 | |

| 11 | Ampicillin | 0.5–64 | 1 | 2 | |

| 11 | Gentamicin | 16–>512 | >512 | >512 | |

| 11 | Erythromycin | 2–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 11 | Ciprofloxacin | 1–128 | 64 | 128 | |

| Ampicillin susceptible | 82 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–1 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| 82 | Ampicillinb | ≤0.25–8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 82 | Vancomycin | 0.5–>64 | 2 | >64 | |

| 82 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | ≤0.125 | 1 | |

| 82 | Gentamicin | ≤1–>512 | 32 | >512 | |

| 82 | Erythromycin | ≤0.25–>64 | 8 | 32 | |

| 82 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.5–64 | 1 | 64 | |

| Ampicillin resistant | 8 | RWJ-54428 | 0.125–4 | 0.5 | |

| 8 | Ampicillinb | 16–128 | 32 | ||

| 8 | Vancomycin | ≤0.125–>64 | 0.5 | ||

| 8 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–64 | 0.5 | ||

| 8 | Gentamicin | ≤1–>512 | 8 | ||

| 8 | Erythromycin | ≤0.125–>64 | >64 | ||

| 8 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–>128 | 4 | ||

| E. faecium | |||||

| All isolates | 122 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–8 | 4 | 8 |

| 122 | Ampicillinb | ≤0.25–>128 | 128 | >128 | |

| 122 | Vancomycin | 0.25–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 122 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–64 | 32 | >64 | |

| 122 | Gentamicin | ≤1–>512 | >512 | >512 | |

| 122 | Erythromycin | 1–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 122 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–>128 | 16 | >128 | |

| Ampicillin susceptible | 22 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 22 | Ampicillinb | ≤0.25–8 | 2 | 8 | |

| 22 | Vancomycin | 0.5–>64 | 0.5 | 8 | |

| 22 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–64 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | |

| 22 | Gentamicin | ≤1–512 | 16 | 32 | |

| 22 | Erythromycin | 1–>64 | 8 | >64 | |

| 22 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25–128 | 8 | 64 | |

| Ampicillin resistant | 100 | RWJ-54428 | 1–8 | 4 | 8 |

| 100 | Ampicillinb | 16–>128 | 128 | >128 | |

| 100 | Vancomycin | 0.25–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 100 | Teicoplanin | ≤0.125–>64 | 64 | >64 | |

| 100 | Gentamicin | 2–>512 | >512 | >512 | |

| 100 | Erythromycin | 1–>64 | >64 | >64 | |

| 100 | Ciprofloxacin | 0.5–>128 | 16 | >128 | |

According to the NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (16), vancomycin susceptible is a vancomycin MIC of ≤4 μg/ml and vancomycin resistant is a vancomycin MIC of ≥32 μg/ml.

According to the NCCLS interpretive breakpoints (16), ampicillin susceptible is an ampicillin MIC of ≤8 μg/ml and ampicillin resistant is an ampicillin MIC of ≥16 μg/ml.

H. influenzae.

RWJ-54428 was found to be very potent against H. influenzae, with MICs ranging from ≤0.0625 to 2 μg/ml and an MIC50 and an MIC90 of 0.125 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. On the basis of the MIC90s, RWJ-54428 was 4-fold more active than ampicillin and 32-fold more active than erythromycin. The activity of RWJ-54428 was similar to those of cefotaxime and imipenem (Table 5). The MICs of RWJ-54428 and ampicillin were 0.125 and 4 μg/ml, respectively, for the only β-lactamase-producing isolate of H. influenzae tested. For isolates with reduced ampicillin susceptibility (MIC range, 0.5 to 4 μg/ml) due to known alterations in penicillin-binding proteins, RWJ-54428 MICs ranged from 0.25 to 2 μg/ml.

TABLE 5.

In vitro activity of RWJ-54428 against gram-negative bacteriaa

| Organism | No. of isolates | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |||

| H. influenzae | 31 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–2 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| 31 | Ampicillin | ≤0.0625–4 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| 30 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.015–0.5 | ≤0.015 | 0.125 | |

| 31 | Imipenem | ≤0.0625–0.5 | ≤0.0625 | 0.5 | |

| 30 | Erythromycin | 1–8 | 4 | 8 | |

| M. catarrhalis | 17 | RWJ-54428 | ≤0.0625–1 | ≤0.0625 | 0.5 |

| 17 | Ampicillin | ≤0.0625–8 | 0.25 | 2 | |

| 10 | Cefotaxime | ≤0.015–0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.25 | |

| 17 | Imipenem | ≤0.0625–0.25 | ≤0.0625 | ≤0.0625 | |

| 10 | Erythromycin | ≤0.015–0.125 | 0.0625 | 0.125 | |

| E. coli | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 4–>128 | 32 | >128 |

| 10 | Amoxicillin | 2–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| 10 | Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 1–>128 | 16 | >128 | |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–128 | ≤0.5 | 64 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–1 | ≤0.25 | 1 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | ≤0.25–>128 | 64 | >128 | |

| Klebsiella spp. | 11 | RWJ-54428 | 8–>128 | 32 | >128 |

| 11 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–32 | ≤0.5 | 32 | |

| 11 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–1 | ≤0.25 | 0.5 | |

| 11 | Ceftazidime | ≤0.25–>128 | ≤0.25 | >128 | |

| Serratia spp. | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 16–>128 | 64 | 128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | ≤0.25–128 | ≤0.25 | 4 | |

| Providencia spp. | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 4–>128 | >128 | >128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | 2–>256 | 32 | 128 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–128 | 4 | 64 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | ≤0.25–>128 | 8 | >128 | |

| Proteus spp. | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 4–>128 | 16 | 128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–64 | ≤0.5 | 32 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | 0.5–16 | 4 | 8 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | ≤0.25–>128 | 1 | >128 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 64–>128 | 128 | >128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5–64 | 2 | 32 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | 2–128 | 8 | 32 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | 4–>128 | 32 | >128 | |

| S. maltophilia | 10 | RWJ-54428 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | 1–128 | 16 | 32 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | 128–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | 1–>128 | 16 | 128 | |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 10 | RWJ-54428 | 32–>128 | >128 | >128 |

| 10 | Ciprofloxacin | 4–>256 | 64 | 128 | |

| 10 | Imipenem | ≤0.25–16 | 1 | 4 | |

| 10 | Ceftazidime | 8–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

Klebsiella spp. include K. pneumoniae (n = 9) and K. oxytoca (n = 2). Serratia spp. include S. cloacae (n = 1), S. liquefaciens (n = 1), and S. marcescens (n = 8). Providencia spp. include P. rettgeri (n = 1) and P. stuartii (n = 4). Proteus spp. include P. mirabilis (n = 7) and P. vulgaris (n = 3).

M. catarrhalis.

RWJ-54428 was also found to be very active against M. catarrhalis, with an MIC50 and an MIC90 of ≤0.0625 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. RWJ-54428 was fourfold more active than ampicillin. The activity of RWJ-54428 was similar to that of cefotaxime (Table 5).

Other gram-negative bacteria.

In a panel containing multidrug-resistant isolates, RWJ-54428 had limited activity against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Serratia spp., Providencia spp., Proteus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Acinetobacter spp. (Table 5). RWJ-54428 MIC ranges for other species were as follows: Citrobacter spp. (n = 9), 2 to >128 μg/ml; Enterobacter spp. (n = 9), 4 to >128 μg/ml; Burkholderia cepacia (n = 7), 16 to >128 μg/ml; Alcaligenes faecalis (n = 1), 2 μg/ml; Alcaligenes xylosoxidans (n = 2), >128 μg/ml; Flavobacterium meningosepticum (n = 1), 32 μg/ml; and Flavobacterium spp. (n = 1), 32 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

RWJ-54428 is a new parental cephalosporin (7) with potent in vitro activity against multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria. The spectrum of activity includes MRSA, MRCoNS, and staphylococci with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics; penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci; group A streptococci; group B streptococci; penicillin-susceptible and -resistant viridans group streptococci; and vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant enterococci.

The unique and potent activity of RWJ-54428 against multidrug-resistant staphylococci was first reported in 1997 (Malouin et al., 37th ICAAC). In the present study, the susceptibilities of 671 clinical isolates of Staphylococcus spp. were examined. These data further establish that RWJ-54428 has potent antistaphylococcal activity in vitro. RWJ-54428 is consistently active against genotypically characterized clinical isolates of MRSA and large populations of clinical isolates of staphylococci from several geographical locations in the United States, Canada, and Europe (Table 1). Overall, RWJ-54428 is 500-fold more active than methicillin against MRSA and MRCoNS. RWJ-54428 is at least eightfold more potent than vancomycin against glycopeptide-intermediate staphylococci. RWJ-54428 is also more active than ciprofloxacin against MSSA, MRSA, MRCoNS, and glycopeptide-intermediate staphylococci.

RWJ-54428 was highly active against S. pneumoniae, including penicillin- and ceftriaxone-resistant strains (Table 3). RWJ-54428 was 8- to 16-fold more potent than penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or cefotaxime against penicillin-intermediate pneumococci and penicillin-resistant pneumococci. There was no correlation between the MICs of ceftriaxone and those of RWJ-54428 for the 34 penicillin-resistant pneumococca strains studied (data not shown). RWJ-54428 was also more potent than ceftriaxone and cefotaxime against penicillin-susceptible, -intermediate, and -resistant viridans group streptococci. The potency of RWJ-54428 was equivalent to that of penicillin against penicillin-susceptible viridans group streptococci; however, RWJ-54428 was significantly more active than penicillin G and the other beta-lactam antibiotics tested against viridans group streptococci with reduced susceptibilities to those agents.

RWJ-54428 possesses significant in vitro antibacterial activity against a variety of enterococci and is among the most active agents against drug-resistant isolates. RWJ-54428 was 8-fold more active than vancomycin and 32-fold more active than ampicillin against vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis. Vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis remained susceptible to RWJ-54428 (which was 1,000-fold more active than vancomycin against these isolates). The activity of RWJ-54428 paralleled that of ampicillin against ampicillin-susceptible, vancomycin-intermediate, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Against ampicillin-resistant, vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, RWJ-54428 was 16-fold more active than ampicillin, and RWJ-54428 was the most active antibiotic against these multidrug-resistant isolates tested in the present study.

S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis are the most common causes of acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis (2, 4, 8, 11). This survey of the susceptibilities of H. influenzae and M. cattarhalis to RWJ-54428 indicated that these organisms are more susceptible to this new cephalosporin than to ampicillin. β-Lactamase-mediated ampicillin resistance in H. influenzae and M. cattarrhalis was associated with a lower level of susceptibility to RWJ-54428; however, RWJ-54428 remained significantly more active than ampicillin against these isolates.

In addition to in vitro potency, pharmacologic data are important in assessments of the clinical usefulness of a new agent. The level of serum protein binding for RWJ-54428 in preclinical studies with animal species and humans ranges between 48 and 84% (L. Harford K. Huie, D. Clark, D. Griffith, K. Jackson, M. Price, L. Case, K. Mathias, S. Chamberland, M. Mohler, D. Desai-Kriefer, S. Aresta, A. Takacs, and M. N. Dudley, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-18, 1998). Studies with six animals species show that RWJ-54428 has pharmacokinetic properties comparable to those of other cephalosporin antibiotics used in humans (Harford et al., 37th ICAAC).

In summary, this survey of the susceptibilities of multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria to RWJ-54428 indicates that this agent has the potential to be a useful agent against gram-positive bacteria and remains actively pursued as a candidate for clinical development. Phase I clinical trials have been initiated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Fred Tenover, Nosocomial Pathogens Laboratory Branch, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for the staphylococcal isolates with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptide antibiotics and Barry Kreiswirth for the sample of genetically diverse MRSA and MSSA strains with distinct staphylococcal protein A genotypes and coagulase A genotypes. We thank the medicinal chemists that made this program possible: Scott J. Hecker, Tomasz W. Glinka, Aesop Cho, Zhijia J. Zhang, Mary Price, and Ving J. Lee.

The work described herein was conducted as part of a research collaboration with the R. W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber M. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J Clin Pathol. 1961;14:385–393. doi: 10.1136/jcp.14.4.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos J M. Haemophilus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 604–613. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers H F. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci: molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:781–791. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doern G V, Jones R N, Pfaller M A, Kubler K the Sentry Participants Group. Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis from patients with community-acquired respiratory tract infections: antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (United States and Canada, 1997) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:385–389. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frenay H M E, Theelen J P G, Schouls L M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E, Verhoef J, Van Leeuwen W J, Mooi F R. Discrimination of epidemic and nonepidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:846–847. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.846-847.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakenbeck R. Mosaic genes and their role in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:597–601. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecker S J, Glinka T W, Cho A, Zhang Z J, Price M E, Chamberland S, Griffith D, Lee V J. Discovery of RWJ-54428 (MC-02,479), a new cephalosporin active against resistant gram-positive bacteria. J Antibiot. 2000;53:1272–1281. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones R N, Jacobs M R, Washington J A, Pfaller M A. A 1994–95 survey of Haemophilus influenzae susceptibility to ten orally administered agents. A 187 clinical laboratory center sample in the United States. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;27:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(96)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones R N, Wilson W R. Epidemiology, laboratory detection, and therapy of penicillin-resistant streptococcal infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;31:453–459. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirby W M M. Extraction of a high potent penicillin inactivator from penicillin resistant staphylococci. Science. 1944;99:452. doi: 10.1126/science.99.2579.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapp J S, Koumans E H. Neisseria and Branhamella. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 586–603. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam S, Singer C, Tucci V, Morthland V H, Pfaller M A, Isenberg H D. The challenge of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a clinical and epidemiologic study. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23:170–180. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maranan M C, Moreira B, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R S. Antimicrobial resistance in staphylococci. Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:813–849. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moellering R C., Jr The specter of glycopeptide resistance: current trends and future considerations. Am J Med. 1998;104(Suppl. 5A):3S–6S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moellering R C., Jr Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1196–1199. doi: 10.1086/520283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution of antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard. M7–A4, vol. 17, no. 2. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perl T M. The threat of vancomycin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;106(Suppl. 5A):26S–37S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller M A, Jones R N, Doern G V, Kugler K. Bacterial pathogens isolated from patients with bloodstream infection: frequencies of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (United States and Canada, 1997) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1762–1770. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaller M A, Jones R N, Marshall S A, Edmond M B, Wenzel R P. Nosocomial streptococcal blood stream infections in the SCOPE program: species occurrence and antimicrobial resistance. The SCOPE Hospital Study Group. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenover F C, Lancaster M V, Hill B C, Steward C D, Stocker S A, Hancock G A, O'Hara C M, McAllister S K, Clark N C, Hiramatsu K. Characterization of staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin and other glycopeptides. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1020–1027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1020-1027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasz A, Munoz R. Beta-lactam antibiotic resistance in gram-positive bacterial pathogens of the upper respiratory tract: a brief overview of mechanisms. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:103–109. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Piscitelli C, deLencastre H, Tomasz A. Tracking the evolutionary origin of the methicillin resistance gene: cloning and sequencing of a homologue of mecA from a methicillin susceptible strain of Staphylococcus sciuri. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:435–441. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]