Abstract

This study aimed to demonstrate how persons with profound intellectual multiple disabilities (PIMD) and nurses, together with welfare workers, communicate with one another and create care at a day care center for persons with PIMD in Japan. The ethnographic method was used. The research participants were persons with PIMD and their mothers, nurses, and welfare workers. The results indicated that care aims at autonomy based on intentions in response to signs. These findings suggest that this practice emancipated persons with PIMD and their mothers from the Japanese “culture of shame” and enable their autonomy.

Keywords: autonomy, care, day care center, emancipation, nurses, profound intellectual and multiple disabilities, “shame culture”

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Persons with profound intellectual multiple disabilities (PIMD) have severe physical disabilities combined with profound intellectual disability, requiring assistance in all activities of daily living.1 Since verbal communication is difficult for such children, their main means of communication is nonverbal, using facial expressions and body language.2 For this reason, it is difficult to understand the intentions of persons with PIMD,3 even for their parents.4 Studies on parents who had made decisions regarding their children's surgery show that the parents agonized over whether they had made the right decision, or even regretted their decision, because they did not know how their children felt about the surgery.5,6 A study on nursing practice found that while engaging in activities with them, the nurses perceived subtle differences in the limb movements and vital signs of persons with PIMD and interpreted these differences as expressions of their intentions.7 Another study using the ethnonursing research method reported that nurses interpreted the alarms and subtle differences the medical equipment display as the voices of the persons with PIMD, assigning meaning to such voices based on the actual circumstances, and if that was difficult, asked for the parents' opinion as experts on their children.8 However, the nurses did not have ways to confirm their own interpretation of the thoughts and intentions of the persons with PIMD, resulting in uncertainty about the validity of their assistance, which affected their motivation.9,10 Some studies have used physiological indicators to gain a better understanding of the reactions of persons with PIMD,11,12 but none of those studies showed how they communicated with the persons with PIMD or how the thoughts and intentions of the persons with PIMD were understood and utilized in their care. Therefore, through fieldwork at a day care center that served as a home-based care site for children (individuals) with PIMD, this research aimed to reveal how the nurses at the center, together with the welfare workers and mothers, established communication and created care.

Recently In Japan, the cases of children with PIMD who require medical intervention such as tracheotomy, suctioning, and ventilator support after being saved in the neonatal intensive care unit are increasing,13 as are the number of children with PIMD with high medical needs.14 Cerebral disorders in children with PIMD affect their life-sustaining functions, including breathing, circulation, temperature regulation, feeding, digestion, absorption, and elimination, necessitating a wide range of care to remedy their conditions.15 Children with PIMD are less likely to express themselves by facial expressions and body language when their condition deteriorates, making it difficult for nurses to understand their thoughts and needs. In addition, it has been revealed that mothers of persons with PIMD who are cared for at home and are usually in danger of losing their life provide 24-hour care.16 However, day care centers for persons with PIMD are in short supply in Japan; therefore, one of the critical challenges in the care of persons with PIMD, with whom communication is difficult, is that children and their mothers cannot get any support and they become alone.17

There are an estimated 36 650 persons with PIMD in Japan, 69% of whom live at home.13 The United States introduced policies for the normalization of people with disabilities in the 1960s, but Japan did not introduce policies for participation in society by people with disabilities until the 21st century.18 Japan has a long cultural background of “shame culture”19 and thus Japanese parents have typically been more reluctant to let children with disabilities out in public.20 Japanese people place great value on obligations and repaying favors, and “shame” is an emotion that is evoked when one is unable to meet an obligation or return a favor. In Japanese culture, to be “shamed” is to have your name and self-esteem damaged. Japan also used to have a “family reign system,” in which a male succeeded the family genealogy, so the birth of a male child has traditionally been desired.19 The family reign system was abolished in 1947, but the belief that the birth of a child with a disability disgraces the family persisted.20 Against this backdrop of “shame culture” and the resultant tendency toward prejudice and discrimination, an increase was seen in the number of cases in which Japanese families refused to take their children with PIMD home from the hospital or infant care home. As a countermeasure, a policy was implemented to place children with PIMD in a facility for protection and ryoiku (treatment, childcare, and education).18 As a result, participation in society by persons with PIMD in Japan was delayed and has only been considered since the beginning of the 21st century. In 2010, the Japanese government created a system that aimed to support independence based on the principle of normalization, stipulated participation by persons with PIMD in social activities as equal members of society through self-selection and self-determination,21 and proceeded to introduce necessary laws. In 2013, the foundation of quality of life (QOL) was defined as protecting the human rights of persons with PIMD without discrimination, supporting their relationship with their family members, and providing them with an environment for living a good life.22 Thus, support measures to emancipate persons with PIMD who are cared for at home have become a critical issue in the modern Japanese society.

On these grounds, the nurses and welfare workers provide assistance by understanding the thoughts and intentions of persons with PIMD in home care; this is a critical challenge that affects the QOL of the persons with PIMD and their families. Nevertheless, the methods used in studies on communication by persons with PIMD have been limited to either interviews or observation, attaching meaning to the data obtained from the nurses' memories or to the phenomena noticed by the observer. Daily practice may be interpreted at the unconscious level and may not be verbalized.8,9,23

Few studies has shown cases in which the nurses viewed the communication with persons with PIMD as interactive, or how the nurses shaped assistance to emancipate them and their families from “shame culture” based on their understanding of the thoughts and intentions of the persons with PIMD who had high medical needs.

Statements of Significance

What is known or assumed to be true about this topic?

Persons with PIMD have difficulty communicating both verbally and nonverbally and are susceptible to life-threatening situations. Therefore, these individuals have high medical dependency and require concentrated care. However, the uniquely Japanese tradition of “shame culture” constrains the lives and behaviors of persons with PIMD and their families.

Communication with persons with PIMD has been studied in terms of understanding them through their families, but few studies have examined care in which persons with PIMD participated in the formation of care and grew as a result or have characterized such care as emancipation from “shame culture.”

What this article adds:

In this study, care that emancipates persons with PIMD and their families from Japanese “shame culture” is identified using ethnographic research methods. This article should be of interest to a broad readership, particularly researchers and practitioners in the field of palliative care. Nurses and welfare staff at a day care facility provided coordinated care to address the medical needs of persons with PIMD and to promote their self-expression and autonomy. This research provides insight into ways to support persons with PIMD and their families to emancipate them from Japanese “shame culture” and enable their autonomy.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate how persons (children or individuals) with PIMD (or “users” of a day care center), nurses, and welfare workers communicated with one another and created care at a day care center in Japan where normalization was the goal.

METHODS

Research design

The ethnographic method was used, as the study was based on the observation and interview about the care and communication. Ethnographies are the written reports of a culture from the perspective of insiders. The insider's viewpoint is referred to as the emic perspective, as compared with the etic perspective, the views of someone from outside the culture.24 Participant observation is the primary method of ethnographers25 and is defined as being present and interacting with participants in routine activities. Fieldwork, data collection, and analyses were performed using the work of Emerson et al26 as a reference. Data were collected through 2.5 years of fieldwork at a day care center for persons with PIMD in Japan. This study was approved by the ethics committee the affiliated university (No. 20115) and the ethics committee of the day care center (No. 0044).

Recruitment

The field for this research was a day care center for persons with PIMD in Japan that was a municipality-designated model business facility. The study participants were adolescents and young adults with PIMD who had been coming to the day care center 3 times per week for at least 1 year, their family members, and nurses and welfare workers (nursery teachers and child welfare workers) with at least 5 years of experience working at a facility for children (individuals) with PIMD.

A request for participation explaining the study purpose and methods was given both in writing and verbally to all users, their parents, nurses, and welfare workers. The parents accepted on behalf of their children that participation in the research was voluntary, that all data would be anonymous (ie, pseudonyms would be used) to maintain strict privacy, that the results might be published in academic and other publications, and that there would be no detrimental consequences of declining to participate in the research. As for informed consent, the researcher and parents explained the contents using words and methods that were understandable to the users, and the users expressed their intent to participate. Finally, 8 (24%) of 33 users and 12 (92%) of 13 workers participated in this study (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Overview of the Research Participants.

| Clinical/Professional Experience | ||

|---|---|---|

| Name(Pseudonym) | PIMDCare, y | DayCare, y |

| Chida (N) | About 15 | 4 |

| Hara (N) | About 15 | 4 |

| Moritaka (N) | About 10 | 4 |

| Yada (N) | About 10 | 3 |

| Nohara (N) | About 10 | 3 |

| Kaneko (N) | About 10 | 1 |

| Aota (W) | About 15 | 4 |

| Abe (W) | About 25 | 2 |

| Utsumi (W) | About 30 | 4 |

| Oki (W) | About 15 | 4 |

| Yamaguchi (W) | About 15 | 4 |

| Takizawa (W) | About 15 | 4 |

Abbreviations: N, registered nurse; W, welfare worker.

Table 2. Overview of the Persons (Children) With Profound Intellectual Multiple Disabilities Who Participated in This Study.

| Name (Pseudonym) | Age During Participation, y | Sex | Disease | Medical Dependency | Family | Attendance, y | Physical Information, Communication, and Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuko | 18-20 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy, chromosomal abnormalities | Home oxygen therapy, gastric lavage, aspiration | Mother, siblings | 3 | Yuko requires frequent suctioning of sputum because of her deteriorating respiratory condition and receives respiratory physiotherapy between activities. She has trouble swallowing and takes nutritional supplements from a gastric tube. Tongue click or wrist movement of the tongue acts as a cue for “yes” to a question. Emotions are also expressed through facial expressions and eye movements but are difficult for a newcomer to understand. The main caregiver is her mother, and it seems to be difficult to manage her breathing. |

| Satoshi | 30-32 | Male | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Gastric lavage, aspiration | Mother, siblings | 4 | Satoshi attended a nearby workshop and was transferred 4 y ago; his respiratory condition worsened after the age of 18 y, and he underwent a tracheotomy and gastrostomy in his late 20s. He is in need of sputum aspiration. His communication is following what he is interested in with his eyes, smiling at objects used for activities, and showing anticipation of wanting to do them. He is unable to vocalize because of a tracheostomy, but can make choices by blinking. Her mother is her main caregiver. |

| Kana | 18-20 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Tracheotomy, gastric lavage, aspiration | Father, mother, grandparents | 3 | Kana had a tracheotomy and a gastrostomy. Her breathing is stable, but she needs respiratory physiotherapy and suctioning. She is unable to speak by herself, but pleasure and discomfort can be read from her facial expressions when she is involved. She cannot move her limbs by herself and has no muscle tone, giving the impression that she is going about her day quietly. Her mother is her main caregiver. |

| Kaede | 18-20 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Aspiration | Father, mother, siblings | 2 | Kaede had been attending a local assisted living facility but was transferred to our facility 2 y ago. She became seriously ill 10 y ago because of aspiration. Her respiratory condition is occasional pneumonia, and she is unable to produce sufficient sputum on her own, requiring suction. Her body is fully assisted with involuntary movements but without muscle tone. Communication is possible with her eyes wide open to see the source of the sound source, she smiles and vocalizes when a CD is played, and her intentions can be inferred. Her mother is her main caregiver. |

| Umi | 28-30 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Tracheotomy, tube feeding, aspiration | Father, mother, siblings | 4 | Umi had been attending a community day care facility but was transferred to our facility 4 y ago. After suffering from repeated aspiration pneumonia since the middle school, she had a gastric catheter inserted when she was in her late teens. In her 20s, her respiratory condition worsened and she underwent a laryngeal tracheostomy and tracheotomy. Regarding communication, she is rich in emotional expressions, such as laughing when spoken to and crying at unpleasant things, but she does not complain about anything in action because of her inability to speak due to the tracheostomy and her quadriplegia. Her adult sister provides support with her mother. |

| Ayaka | 18-20 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Tracheotomy, tube feeding, aspiration | Father, mother | 2 | Ayaka had been coming to the day care center for 2 y. She had a tracheotomy when she was 8 y old and a tracheal laryngectomy when she was 18 y old. She can communicate through nervousness during calls and questions, looking at picture books with awareness, smiling, and other facial expressions. Since she has difficulty moving her body by herself, she receives expectoration care through respiratory physiotherapy. She eats congee meals orally but is only able to drink water through a stomach tube to supplement her daily intake. Her mother is her main caregiver. |

| Kota | 28-30 | Male | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy | Tracheotomy, gastric lavage, aspiration | Father, mother, siblings | 4 | Kota had been attending a day care facility in the community but was transferred to our facility 4 y ago. He underwent a tracheotomy when he was in elementary school and later underwent a gastrectomy. His respiratory status is stable, but he requires suctioning as needed. He is taking a paste diet with full assistance. He moves his eyes and mouth on call and seems to feel that it is working for him. His responses are limited, but he moves his eyes at the right time. He can express pleasure and discomfort from the slightest change in facial expressions. His mother is his main caregiver. |

| Haruka | 18-20 | Female | Cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus | Gastric lavage, aspiration | Father, mother, siblings | 2 | Haruka had an esophageal hernia in her mid-teens and has undergone and gastric lavage, as well as gynecological surgery. She currently consumes food in paste form but needs to aspirate because she has difficulty producing sputum on her own, partly because of a decline in her ability to swallow. Her communication is rich in emotion through facial expressions, with smiles and vocalizations in response to involvement. Her mother is her main caregiver. |

Data collection

Participant observation

Participant observation was performed once or twice a week to observe how the users were understood and assisted. The observed situations included the nurses' involvement with the users, users and nurses interacting with other nurses, welfare workers, and parents, and staff meetings and other situations that involved exchanging information about the users. Data collection started after a 2-month period, during which time, the users, nurses, and welfare workers became accustomed to the presence of the researcher. A fieldwork researcher is a “participant observer.” The researcher observed the participants' speech, actions, facial expressions, body language, behavior, timing, and the context of their behavior. If necessary, the researcher took notes from an out-of-sight location. Field notes were prepared on the same day, after the day's fieldwork had ended.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted with nurses, welfare workers, and parents. The interview topics included confirming the situations observed by the researcher, confirming the interpretation of the observations, and understanding the observed actions and their intentions.26 In addition, 30- to 50-minute formal interviews were conducted with nurses and welfare workers to capture the overall picture, including their understanding of and thoughts about the lives of the users and the process of assistance. To understand the actual practice, informal interviews were conducted while the memory of the situation was still fresh. In addition to individual interviews, several people were interviewed as a group during a discussion in the staff room or during cleanup time. These interviews were about the interpretation of the observations and were done when needed. The mothers of the users took part in one formal interview for about 30 minutes to talk about the history, current status, and their hopes for their children. They were also interviewed informally 4 to 5 times during events and bus rides to and from the center. The interviews were recorded using an IC recorder, and memos were taken during the interviews with the permission of the participants. Interviews were conducted until saturation was reached. Interviews and data collection were conducted in Japanese.

Data collection from records

Data collected from medical records and support plans, meeting minutes, correspondence notebooks, and other records were added to the field notes as support materials for understanding the data from the observations and interviews.

INTERPRETATION AND ANALYSIS

To gain a better understanding of what the events and experiences meant to the people in the field, an inductive approach was taken for the data analysis, examining the field notes26 in detail. Concepts and analytical insights were also examined for verification. The analysis in this research revealed how the nurses communicated with and provided care to the users, by recording the nurses' modes of communication and methods of understanding in the field notes and by interpreting and continuously accumulating the detailed data. The actual process consisted of the following 4 activities: (1) accumulating extensive descriptions through an examination of the day's fieldwork on a daily basis; this included using the impressions and notes written in the field notes as a reference for understanding and delving deeper into the interpretation by comparing the events with other events in the past; (2) open coding and focused coding to express data and phenomena in a conceptual form; instead of using the existing coding categories, new codes were created from the field notes. For open coding, words that intuitively came to mind were written next to the original field notes, and for focused coding, field notes were reexamined while considering the field notes from other dates; (3) repeating this coding process to identify a theme and building a general framework; and (4) showing these as “typical examples” from the field notes.

The trustworthiness evaluation standards27 were referenced to guarantee the quality of the research. Throughout the process, the research was under the supervision of the research supervisors and peer reviewed by pediatric nursing experts. The research results were reported back to the participants and confirmed and revised until they agreed.

FINDINGS

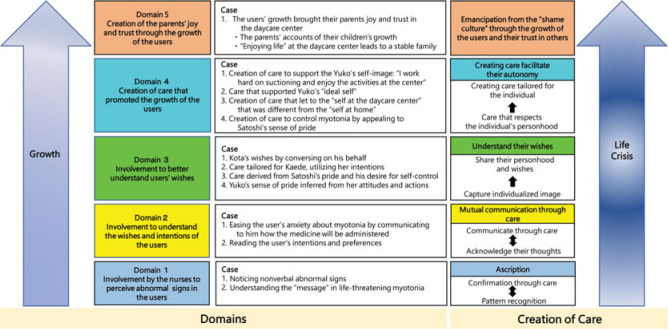

The results of the fieldwork revealed the following 5 domains: (1) involvement by the nurses to perceive abnormal signs in the users; (2) involvement to understand the wishes and intentions of the users; (3) involvement to better understand user's wishes; (4) creation of care that promoted the growth of the users; and (5) creation of the parents' joy and trust through the growth of the users (Figure). The 5 domains are discussed in greater detail in the following section and illustrated with examples (Table 3).

Table 3. Typical Examples: Creation of Care by Nurses, Welfare Workers, Families, and Persons (Children) With Profound Intellectual Multiple Disabilities That Emancipates Them From the Japanese “Shame Culture”.

| Domain 2: Involvement to Understand the Wishes and Intentions of the Users |

| Reading the user's intentions and preferences (Ayaka) |

| Ayaka was unable to speak because she had undergone a tracheotomy. On the morning of a scheduled bathing day, several welfare workers said to Ayaka, “Today is bathing day. You love it, don't you?” Ayaka responded every time by thrusting her fist high. Nurse Moritaka explained to her, “Let's do the suction first, then take a bath.” During suctioning, her turn for bathing was changed, and Ayaka frowned. Nurse Moritaka said, “It's okay. We'll go as soon as this is over,” and noticed Ayaka's face relax. Several minutes later, Ayaka was arching her neck and back, pouting, and clenching her fists tightly. Changing Ayaka to the supine position, Nurse Moritaka said, “You really were ready for the bath, weren't you? Let's go take a bath now.” Ayaka's muscles relaxed immediately. Nurse Moritaka had noticed Ayaka's strong desire for the bath, as demonstrated by her raised fist, but decided that she could wait a little longer because her frowning lessened when the nurse explained the situation to her. Several minutes later, however, seeing Ayaka stiffening and arching her back, Nurse Moritaka corrected her assessment of Ayaka's desire for the bath and verbalized it to her (“You really were ready for the bath, weren't you?”). The fact that Ayaka immediately relaxed demonstrated that the reassessment was correct. |

| A welfare worker explained that one of the reasons Ayaka liked the bath was the esthetic hair treatment she got after the bath. Ayaka was growing her hair out so that she could wear a traditional Japanese updo for a Coming-of-Age Day ceremony. Seeing this, the nurses and welfare workers knew that Ayaka was eagerly awaiting the ceremony and growing her hair out in anticipation. Her mother would write in the correspondence notebook about her daughter's hair. It was often reported in morning meetings that Ayaka had refused to have her braided hair undone. From these episodes, they understood what Ayaka wanted from her care. |

| Domain 3: Involvement to better understand users' wishes |

| Care tailored for Kaede, utilizing her intentions (Kaede) |

| According to Kaede's mother, when Kaede found out that she would not be coming to the day care center because of a doctor's appointment, she became upset and agitated and her mother had a difficult time calming her down. Kaede's mother wrote about that episode in the correspondence notebook, and it was reported at the morning meeting the following day. When the nurses and welfare workers said to Kaede, “So you really wanted to come to the center,” she smiled, moved her head from side to side, and looked happy. The staff was surprised by Kaede's response (“Look how happy she is!”) and realized how much she had been looking forward to coming to the center. They responded to Kaede's feelings by smiling and saying, “We're so glad you could come,” communicating that they were happy for her too. |

| Kaede usually would not do anything she did not want to do but would occasionally bend to the staff's persuasion and make an effort. From what her mother told them, the nurses and welfare workers knew that Kaede wanted to have fun at the day care center. |

| Care derived from Satoshi's pride and his desire for self-control (Satoshi) |

| Satoshi's difficulty breathing, accompanied by unexplained cyanosis, was a problem. One day, a nurse and a nursery teacher paid Satoshi a visit at home. At the staff meeting after the visit, they reported that Satoshi's mother was calling him aniki with respect and that Satoshi seemed to be pleased to hear others say things like “Aniki, that is amazing.” The nurses and welfare workers were surprised by this side of Satoshi, which was quite a contrast to the aggressive side he showed at the day care center. They also realized that being called aniki had a special meaning to Satoshi. He looked proud when someone respectfully called him aniki or senpai (someone who is your senior or a mentor). This showed that Satoshi wanted to act like an aniki or a senpai and wanted others to respect his sense of pride. |

| Yuko's sense of pride inferred from her attitudes and actions (Yuko) |

| Yuko's respiratory condition was worsening, but with daily care, she had started to participate in activities. One day, a nurse realized that Yuko had a sense of pride in her performance at the day care center. A young girl came to the day care center for a 1-day trial stay. She was a student at the high school for special needs education where Yuko had attended. During nebulizer treatment, Yuko would often wave the mist away from the mask, but on that day, she just sat there with straightened arms and a calm, distant look on her face during inhalation. Nurse Moritaka, who set up the nebulizer, noticed the difference in Yuko. The nurse continued to observe Yuko from a short distance, but seeing that Yuko stayed completely still, she said, “This should work today,” and just left the mask on Yuko's mouth, without any additional effort to keep it in place. Later in the day, the nurses talked about Yuko in the nurses' lounge. Nurse Chida: Did you see how Yuko was today? She was totally acting like a role model! Nurse Moritaka: I know! She was acting so calm. She didn't move at all during the nebulizer treatment. She was like, “Look at me. This is how you do it.” (She mimics Yuko.) Nurse Hara: Right. Usually, for suctioning, we have to lead her, saying “Ehhh” but today, she goes “Ehhh” on her own. Nurse Moritaka: Yui (The young student from the high school) was on the mat next to Yuko, and Yui's mother said to everyone, “Yui is here for a trial stay today. I hope she will be okay.” As soon as Yuko heard that, she opened her eyes really wide and suddenly looked very alert. I was surprised. After that, she stayed awake and alert, and she seemed to be showing the new girl what to do, “Look, this is how you do it here at the center.” Nurse Hara: Exactly! Nurse Chida: You know, Yuko's nickname at the school was “Chairman.” Nurse Hara: The other students must have respected her. Nurse Chida: Yeah, it was her air of confidence. As the nurses exchanged information about Yuko's behavior that was different from her usual pattern, they realized that her unusual behavior, such as staying calm and still during suctioning and volunteering cooperative movements while suctioning, was caused by the presence of the young student. The nurses also talked about Yuko's personality at school, and in doing so, became aware of her pride in doing well at the day care center. |

| Domain 4: Creation of Care That Promoted the Growth of the Users |

| Creation of care that led to the “self at the day care center” that was different from the “self at home” (Kaede) |

| Kaede usually would not do anything she did not want to do but would occasionally bend to the staff's persuasion and make an effort. They worked to draw out Kaede's desire to have a good time at the center and encouraged her to be the person she really was, ie, “Kaede, who is capable of doing things she doesn't want to do.” The nurses started to explain to Kaede that suctioning and hydration were necessary steps to make sure that she could “have fun at the day care center.” When Kaede refused the suctioning before lunch and kept her mouth closed, Nurse Moritaka told her, “Let's make sure to do it before you go home.” Later, Nurse Moritaka said to Kaede, “Let's do it, so you can go to the field trip tomorrow.” She knew that Kaede was looking forward to the field trip. When the nurse said, “Please cough,” Kaede coughed hard twice, bringing up white phlegm into her mouth. Then, when the nurse said, “Open your mouth,” Kaede opened her mouth all the way and did not resist the suctioning. Usually, she would clench her teeth and push the tube away, but this time, she went through the suctioning without even shaking her head. Nurse Moritaka said emphatically, “You did great! It feels good when you cough it up like that, doesn't it? You're done now. I'm impressed! You can go on the field trip tomorrow.” Kaede was smiling and looking at Nurse Moritaka with big round eyes. |

| One day, Nurse Nohara learned from the mother's note in the correspondence notebook that Kaede was still being fussy at home. Nurse Nohara thought that Kaede was separating her “self at home” from her “self at the center” because Kaede at the center was willing to work on the suctioning, which she disliked. The nurse wanted to respect Kaede's thoughts. Monday morning, Nurse Nohara took one look at Kaede and said, “Oh, they have turned purple.” Kaede's oxygen saturation percentage was in the low 90s, and she was being suctioned. The number indicated that her respiratory care at home was inadequate. Since it was impossible to provide the same respiratory care at home as at the center, Kaede's care plan was to perform suction every day at the center and return her lungs to a good condition by Friday, so her care at home over the weekend could be light. The nurse helped Kaede enjoy the activities at the center as well as her life at home by providing respiratory care tailored specifically for her, emphasizing respiratory care at the center rather than at home. As a result, Kaede grew into her “self at the day care center,” which was different from her “self at home.” |

| Creation of care to control myotonia by appealing to Satoshi's sense of pride (Satoshi) |

| According to the nurses and welfare workers, they found out by chance that the words aniki and senpai meant something special to Satoshi and started to praise his behavior in ways that elicited that feeling, which gave him a sense of pride and enabled self-control over his tension. One day, Satoshi participated in bowling as part of a day care center activity. While waiting his turn, he became impatient. He raised his arms, pouted, arched his back, and shook his shoulders. Ms Abe (a nursery teacher) saw this and talked to him. Ms Abe: “Do you want to bowl? It's your turn to cheer for them now. Then, it will be your turn to bowl. Satoshi: (Stares at the bowler. His raised arms start to relax and are lowered slightly.) Ms Abe: “Yes. I'm impressed, aniki.” Satoshi: (Looking at Ms Abe, starts to lower his arms.) Nurse Moritaka: “Oh, that is great, aniki. Is it okay if we let Kato go next? It's okay, right? Because you're the senpai.” Satoshi: (Pouts and looks at Kato, raises his arms high and waves.) Nurse Moritaka: “Let's cheer for him.” Welfare worker: “Good for you, senpai!” Welfare worker: “Aniki!” Still pouting, Satoshi looked around. When he saw Nurse Moritaka's face, he relaxed his mouth, lowered his arms, and turned to look at the bowler. In the past, Satoshi would have tensed up and had difficulty breathing when Kato was allowed to go before him. This time, when Nurse Moritaka and the welfare workers all talked to Satoshi, calling him aniki and senpai, he hesitated a little but relaxed his pout and lowered his arms. Ms Aota (a nursery teacher) observed that Satoshi was able to wait his turn without tensing up when people called him aniki and explained the situation to him. (“You will be next. Your wheelchair is ready.”) She said that this established within him an experience of “being able to wait without tensing up.” After 2 wk, he was able to do that even without being called aniki. When he was told about the waiting time, what he would be doing, and other plans, he was able to understand the situation and control his feelings. He had truly become an aniki. As they continued to provide care that respected his pride in being an aniki, the nurses and welfare workers realized that he could control his myotonia by himself, even when they did not use that word. They had created a personalized form of assistance for Satoshi that respected his own power. |

| Domain 5: Creation of the Parents' Joy and Trust Through the Growth of the Users |

| The parents' accounts of their children's growth |

| Yuko's mother wrote in the correspondence notebook that her conversation with Yuko had become livelier. “Lately, Yuko's response has been more frequent and timely. In the past, I sometimes had to guess and wonder what she was feeling, but now she vocalizes and says, ‘ummm,’ so I always wait for her to respond. It is amazing. I couldn't have imagined this happening one year ago. The day care center is amazing.” (Yuko's mother) Yuko's mother wrote about the joy of hearing about her daughter's day at the center and participating in the delightful interaction. |

Figure.

Creation of care by nurses, welfare workers, families, and persons (children) with profound intellectual multiple disabilities that emancipates them from the Japanese “shame culture.”

The 5 domains

Domain 1: Involvement by the nurses to perceive abnormal signs in the users

Although the users were unable to communicate their needs and intentions verbally, the nurses were able to provide care by being aware of their nonverbal voices, subtle movements, and changes in their facial expressions to perceive abnormal signs and understand their causes.

Noticing nonverbal abnormal signs (Haruka)

The nurse provided care by understanding Haruka's physical condition through her subtle movements and facial expressions.

Haruka was able to vocalize (“ahh”) and show pleasure or discomfort through facial expressions, but it was difficult for her to communicate intentions. During the morning health check, Nurse Hara suctioned Haruka's stomach contents with a syringe from her gastrostomy site. As soon as Nurse Hara started to suction, Haruka frowned and looked as if she were about to cry. Looking at the contents of the syringe and Haruka's expression, Nurse Hara said, “Oh, I'm sorry. I know you don't like it.” When the nurse slowly pulled the syringe, Haruka's frown deepened and her body stiffened a little. She clenched her fists tightly and tensed up her shoulders. The syringe pulled more than 20 mL of gastric juice mixed with the nutritional formula given in the morning. Nurse Hara said, “We can suction as much as 60 mL. It looks like your stomach is not moving well.” She palpated Haruka's abdomen. “It's soft.” She then listened with a stethoscope and said to herself, “Your stomach movement is not so good.” Since Haruka's expression showed strong discomfort during the suctioning of stomach contents, Nurse Hara suspected abdominal discomfort. Checking the condition of Haruka's abdomen and her facial expression, Nurse Hara determined that Haruka's intestines were not moving well, although there were no symptoms of ileus. Haruka usually takes water by mouth, but Nurse Hara switched to slowly feeding the water through the gastrostomy tube to prevent dehydration while her stomach contents were stagnant.

Understanding the “message” in life-threatening myotonia (Satoshi)

To help Satoshi recover from breathing difficulty caused by myotonia, the nurses provided care by understanding his “message,” referencing patterns from past experiences.

Satoshi's issue was unusual myotonia as a symptom of cerebral palsy. His myotonia was controlled by a muscle relaxant to maintain a moderate level of muscle tension but was worsened by ill health, psychological stress, desire, or other stimulation. To keep his myotonia from worsening, it was necessary to identify the physiological issue quickly or, in its absence, to respond immediately to his desires or demands.

One day, Satoshi's myotonia worsened and he began showing signs of cyanosis. He was tense, frowning, and arching his back with his hands raised high. His face and lips were rapidly turning dark purple. His oxygen saturation was at 50%, and his respiratory condition was worsening. Nurse Hara shot rapid-fire questions at Nurse Chida:

Nurse Hara: “Medicine?”

Nurse Chida: “I just gave it.”

Nurse Hara: “How about phlegm?”

Nurse Chida: “Not yet.”

Nurse Hara said, “Okay, we're suctioning,” and turned the oxygen up. Then, she said to Satoshi, “We are going to suction,” and started tracheal and nasal suction, pulling out a large amount of white phlegm. His tension eased and air entered his lungs. His oxygen saturation reading went back up to 70%. Satoshi started to relax when Nurse Hara looked into his eyes and said, “Sato-chan, we just pulled the phlegm out. It is okay. You can breathe.”

Today, the issue was not the dyschezia or the medicine. By eliminating each discomfort factor, I decided phlegm was the only issue. When we suctioned it out, his myotonia was gone and air entered his lungs. Not much from the trachea, but we pulled it out through the nasal tube. I think the accumulated phlegm was making him uncomfortable. (Nurse Hara)

Nurse Hara was reaching into her reserve of experiences with Satoshi's myotonia, applying the patterns of causes to the current situation to rule out possible causes. By observing Satoshi's tension ease after suctioning, she determined that this time, Satoshi had wanted to communicate the discomfort caused by the accumulation of phlegm.

Nurse Chida explained that she could guess what Satoshi wanted from the look in his eyes and the level of his muscle tension, and she could understand what his message was based on how his tension eased or worsened as a result of his communication of intention. After attending an event one day, Satoshi had persistent muscle tension and his facial expressions showed constant agony. In this tense situation, Nurse Chida noticed that his eyes were fixed on the poster of an idol group, A, which he had received at the event. When she asked, “Do you want to see this?” and showed him the rolled-up poster, Satoshi's arms tensed up and rose higher, and he continued to stare at the poster. A welfare worker unrolled the poster, but when it accidentally rolled up again, Satoshi tensed up even more and stared at the poster more intently. Nurse Chida asked, “Do you want me to put this up?” and hung the poster with tape. When she asked, “How is this?” his whole body immediately relaxed and his oxygen saturation level recovered to 90%. Nurse Chida slumped on the floor and sighed, “So that was it.” Here again, the nurse applied the patterns of causes drawn from her reserve of experiences with his myotonia to understand the message he wanted to send through myotonia, which could potentially put his life at risk.

Domain 2: Involvement to understand the wishes and intentions of the users

When communicating with and providing care for the users, the nurses understood their anxieties, intentions, and preferences, not only from the users' responses observed at the time but also through comparisons with past responses experienced by the nurses and with information based on the responses observed and interpreted by the families and welfare workers at the day care center (Table 3).

Easing the user's anxiety about myotonia by communicating to him how the medicine will be administered (Satoshi)

Satoshi's myotonia had to be controlled in order for him to enjoy the activities at the day care center. The nurses had inferred that one of the triggers of Satoshi's myotonia was stimulation due to his interest in the activities, which occurred immediately before the oral administration of a muscle relaxant. Satoshi's anxiety over his past experiences of myotonia was further exacerbating his tension. Based on this understanding, the nurses had been thinking about ways to raise the threshold level.

Nurse Hara had inferred that Satoshi had his own thoughts about medication, based on her experience administering the medication during his myotonia immediately before the oral administration of a muscle relaxant. She wanted to know Satoshi's thoughts and use that information to ease his tension.

The muscle relaxant (scheduled medication) is injected after a meal. You inject it 30 minutes after RG (a mucosal protective agent) is administered. You have to give RG first, before the scheduled medication. Satoshi calms down when you give him RG. He knows the drill. He is aware that once he gets his RG, he can also get the muscle relaxant. He knows that getting RG means that he can relax and that he can get the muscle relaxant any time. (Nurse Hara)

Nurse Chida was also aware that Satoshi's anxiety lessened when the medicine was injected.

The other day, Satoshi was so eager to play the game that he was tense and hurting. When the doctor said, “I'll give you the medicine. Then you'll be all right,” he immediately relaxed. (Nurse Chida)

Nurse Chida had observed that Satoshi relaxed when the doctor talked to him and gave him the RG injection, which was not effective for myotonia. She understood that Satoshi was aware of the order in which the drugs were given and that just knowing that he would be ready to receive the muscle relaxant alleviated his anxiety. Therefore, if the nurses sensed that Satoshi was about to tense up, they always made a point to confirm the administration of RG verbally (“Have you given him RG?”) in front of him. They were not alleviating his myotonia per se, but rather providing care to get him ready to receive the muscle relaxant at any time, give him reassurance, raise his threshold for anxiety, and enable him to participate in activities. This care was based on the understanding that Satoshi was aware of the effects of the drugs and the order of their administration and knew the meaning of the RG injection. Ms Aota, the welfare worker, called this type of involvement by the nurses “involvement as the basis of activities.”

Domain 3: Involvement to better understand users' wishes

Nurses and welfare workers formed an image of each user in the process of detecting abnormal signs and understanding the intentions, preferences, and anxieties of the users. The individualized image was confirmed through the experiences of other nurses and welfare workers and the users' families.

Sharing. Kota's wishes by conversing on his behalf

Kota had severe quadriplegia. He showed subtle changes in his facial expressions but did not smile or cry. According to the welfare workers, his face became flushed when he was displeased and he sometimes turned his eyes toward an object of his interest, but these were not sufficient clues for understanding his feelings.

Ms Utsumi, the welfare worker, was preparing a meal when Kota came to the table in his wheelchair. She put a bib on Kota and brought the food to him from the serving cart.

Ms Utsumi: “Okay, Kota. Itadaki manmosu (mammoth)!” (An old Japanese joke involving a play on words on the phrase, ‘Itadaki masu (Let's eat)’.)

Kota: (Slightly stiffens his arms and turns his eyes upward.)

Ms Utsumi: “What is it, Kota? I have never seen you do that before. I'm surprised.”

Ms Abe (the welfare worker): (Approaching) “Yeah, that looks different.”

Ms Utsumi: “Did the ‘mammoth’ scare you?”

Kota: (Slightly tenses his body and widens his eyes to stare at Ms Utsumi with a startled look.)

Ms Abe: “I think Kota is saying, ‘Oh, puh-lease! That is so lame!’”

Others: (Laughter) (Someone says) “He's like, ‘I didn't see that coming.’”

Ms Utsumi: “Are you saying that I am ancient?” (Laughter)

Kota: (Opens his eyes even wider and looks at Ms Utsumi.)

Ms Utsumi: “Nice, Kota!”

Ms Abe: “Yes, nice reaction. He's like, ‘Please, not that!’”

On more than one occasion, the nurses and welfare workers read Kota's feelings based on his reactions and expressed them verbally on his behalf. It looked as if Kota, who was unable to speak, was initiating the conversation and livening up the mealtime. Later, the nurses and welfare workers talked about this exchange. Ms Abe said, “To me, that didn't sound like Kota.” According to Ms Abe, someone with Kota's personality would not be scared of a mammoth but would be more likely to make fun of Ms Utsumi's ancient joke. Ms Abe told Nurse Chida and me about an episode that had given her an idea of Kota's personality.

The other day, our bus got lost and I was flustered. I noticed Kota looking at me with wide eyes with his mouth open. He looked like he was saying, “Hey, is everything okay?” I have heard other people say that Kota listens to our conversations. When he is attending a group activity, he falls asleep if he is not interested, and opens his eyes at the end, as if he is saying, “Is it over?” He has that kind of dry sense of humor. So, I thought he would not be scared of a mammoth; he was poking fun at a stale joke, more like, “That's so lame!” When I said that, he reacted by widening his eyes, so I knew I was right. Otherwise, he would not have reacted. He does not react or widen his eyes unless he is interested. As you observe him, listen to him, and get involved, you start to form an image of Kota and understand his personhood. In caring for him, you always have that image as a reference, so you can provide care that encourages his expression of personhood. (Ms Abe, welfare worker)

Nurse Chida replied to Ms Abe that understanding his reaction might involve referencing his image or personhood rather than assigning a meaning to each reaction. Ms Abe suggested that in a day care center, the same group of people gather every day, with the staff exchanging information and opinions on the personalities of the users and accumulating knowledge about their personhood. Nurse Chida also stated her view that “personhood is something that is created.”

Domain 4: Creation of care that promoted the growth of the users

The nurses recognized the wishes expressed by the users and provided care centered around those wishes so that the users could live according to their preferences. This not only increased their satisfaction but also enhanced their efforts and self-esteem, promoting their self-expression and mutual sharing and interaction. As a result, they seemed to be happy to come to the day care center (Table 3).

Creation of care to support Yuko's self-image: “I work hard on suctioning and enjoy the activities at the center”

Yuko had difficulty breathing. When she started coming to the day care center 3 years ago, her condition had deteriorated so much that her whole day at the center was spent on suctioning, but she gradually became able to participate in activities. Nurses prompted her by saying, “It's your job,” and she responded by challenging the work.

Nurse Chida: “Okay, let's start the suction.”

Yuko: (Sticks her chest out, lifts her chin, and aligns her nostrils with the tip of the suction tube. She even gets the angle right so that the tube and her nasal bridge form a straight line. She maintains that posture throughout the suctioning, with her arms stretched straight along the trunk of her body, and only her nose sticking out.)

Nurse Chida: “See? Isn't she doing great? This means she wants me to do it.”

Yuko: “Ehhh!” (Tenses her shoulders and strains.)

Nurse Chida: “She wants to cough it up. When the tube is in her trachea, she goes ‘ehhh’ to cough up the phlegm.”

Yuko: “Ehhh, ehhh!” (She strains. When the phlegm starts to come out, she hits Nurse Chida's hand several times.)

Nurse Chida: “I know. It hurts. (saturation: 85%, heart rate: 125 bpm). Let's rest for a while.”

Yuko: (Relaxes her shoulders and does not resist the Ambu bag.)

Nurse Chida: “See? This means she is asking me to do it. She is totally in sync with the bagging. I do not remember when, but at some point, she started to synchronize her breath with the bagging. You are recovering fast today. I knew you would. I guess we can stop suctioning. It is Friday, so this is your job. Right, Yuko?”

Yuko: (Makes a smacking sound and flexes her hands.)

Seeing Yuko cooperate with suctioning time after time, Nurse Chida understood that Yuko not only wanted to be suctioned to ease her discomfort but also considered expelling phlegm to be an important job for her to perform. When Yuko started to cooperate, the nurse acknowledged her willingness to cooperate and praised her efforts (“Isn't she doing great? That is it, you're doing so well.”). This encouraged further cooperation from Yuko, in addition to her movements to expel phlegm during suctioning. She signaled the transition back to suctioning from bagging by moving her wrist and even aligned the position of her nose to the angle of the suction tube to facilitate insertion. In other words, she performed her “job” very well. Lately, Yuko had been making sounds like a sigh (“ummm”), communicating her own intentions, and improving her respiratory functions in her own way.

Care that supported Yuko's “ideal self”

By observing how Yuko acted before she tried hard to cooperate with suctioning, the nurse became aware of Yuko's pride in “doing well at the day care center.” Nurse Moritaka accommodated Yuko's wishes to be a role model and to demonstrate her efforts in suctioning by taking measures such as starting the oxygenation earlier.

Everybody has some wishes. Figuring out what they are will give you a sense of direction. I want Yuko to participate in the activities, if only a little, and have a sense of accomplishment for that day. I think that makes her try harder and recover faster. If I tell her that she is going to do an activity next, she works hard to expel phlegm and inhale oxygen. I often feel that she is working hard so she can recover. If she keeps this up, she will be in even better shape, not just getting better today but also maintaining that state. That is why I try to get her in a better shape, so she can participate in the activities.

Nurse Yata saw Yuko participating in one of the activities, a fashion show. Yuko had been in suctioning all day until the show started, but when a welfare worker introduced her, she acted prim, like an actual model, as if to say, “Everyone, look at me!” From the way Yuko enjoyed herself, Nurse Yata realized that “Yuko really looks forward to the activities.”

The nurses supported Yuko through the formation of care that allowed her to improve her respiratory functions in her own way so that she could lead a life she wanted and be her ideal self.

Even if her days were dominated by suctioning, she participated in the activities with poise. The nurses saw this and recognized that Yuko had an ideal image of herself “working hard at the center” and “enjoying the activities” and thus provided care that supported her self-image. Through the care that supported her ideal self, Yuko was able to improve her own physical condition and enjoy being at the day care center.

Domain 5: Creation of the parents' joy and trust through the growth of the users

The users' growth brought their parents joy and trust in the day care center

Nurses and welfare workers used correspondence notebooks and short conversations during pickup time to talk about the users with their parents. This type of care gave the parents joy from seeing their children's growth, and the nurses explained that a happy life at the day care center results in trust in the center and a stable family life (Table 3).

The parents' accounts of their children's growth

The mothers spoke of their joy as parents in seeing their children growing, enjoying having interactions with others, and looking forward to coming to the day care center. Kaede's mother described a recent episode.

She does not want me to come to the day care center. I think she shows a different face at the center from her face at home. She probably has her own world at the center—a different self that she does not want her parents to see. (Kaede's mother)

Kaede's mother looked happy talking about Kaede's different side that she did not show at home and the formation of her “self at the day care center.” Kota's mother described the following:

He does enjoy coming here. He is healthy. It feels like a dream come true. He looks so calm. I am happy just to have him come here. They manage his health here, so there is a rhythm in his life. If the child is happy, the parent is happy, and vice versa. With all the activities provided here, Kota seems to be having fun in his own way. (Kota's mother)

Coming to this day care center was the first time Kota was away from his mother for a long time.

“Enjoying life” at the day care center leads to a stable family

The nurses were also aware that when the users were able to participate in the activities as they wished, their facial expressions and behaviors started to change.

As the users went through the routine of going to the day care center and coming home, their parents learned that their children enjoyed being at the center and that they could entrust their children to the center. As a result, the parents were able to recover from caregiver fatigue during the day and be more fully involved with their children in the evening and on weekends.

When the parents saw their children's happiness and growth, their trust in the nurses and welfare workers was strengthened. This, in turn, gave the parents room to relax and alleviated the users' anxiety, creating a virtuous circle.

DISCUSSION

Care that identifies life crises that users are unable to express as a basis for autonomy

This research demonstrated that the nurses at the day care center noticed abnormal signs in the users, which the users could not communicate verbally, by observing subtle physical changes. They ascertained the meaning of such changes through communication and observation and made caregiving decisions based on their past experiences.

First, the nurses noticed subtle differences in the users' facial expressions or anything different from their normal state, detected abnormal signs, and began to assess the situation. Then, comparing it with the normal values and states, they observed the differences to confirm an abnormal situation and its causes and addressed the situation. It has been reported that it is difficult to judge the physical symptoms of users by applying reference values because of their high individuality.28 Because of underlying conditions, users are also susceptible to respiratory problems during abnormal muscle tension and convulsion, necessitating suction. Acute conditions, such as convulsion, could be life-threatening.29

Since the Japanese system prohibits day care centers from providing treatment, users with high medical dependency must be transferred to an emergency outpatient if their condition worsens. When the users participated in activities at the day care center without wearing a monitor or left the center for activities, the nurses needed to take necessary measures before an abnormal situation occurred. While interacting with the users, the nurses at the day care center perceived subtle differences as abnormal signs, assessed the causes and the situation based on their medical knowledge, and addressed the abnormal situation.

In addition to general medical knowledge, the nurses at the day care center had a stock of experiences, including the users' needs and anxieties, which they recognized as patterns. In a previous study,30,31 it was found that the staff of a group home tended to pursue communication by finding meaning through temporary “ascription” (ie, temporary assessment) while interacting with children with PIMD. The nurses in this study also recognized the user's abnormal signs, verbally communicated the temporary ascription to the user, and observed the user's reaction to confirm the validity of the assessment. However, the difference in this study was that the nurses' ascription was not made on a blank slate but rather by recognizing patterns in past experiences.

Another unique characteristic of the communication and care seen at this day care center was that the ascription took place between the nurses and users and was carried over to the dialogue with the mother, other nurses, and welfare workers to coordinate the assessments in a group setting. Kruithof et al32 demonstrated the importance of transferring detailed knowledge of mothers of children to supporters.

In this research, ascription utilized the daily information about the user and the knowledge about the physical condition that the mother gave. Through these findings, it was revealed that the nurses at the center detected subtle changes in the users.

Creation of care that encourages users' wishes and facilitates their autonomy

The day care center nurses and welfare workers in this study worked to find an individualized image for each user by providing care that encouraged self-expression through facial expressions and body language. On the basis of this image, they provided care that drew out the users' personhood and, in the process, created care that enabled the users to grow. To the best of our knowledge, few researchers have reported the self-growing involvement of individuals with PIMD while receiving care in a life-threatening situation.

The nurses and welfare workers recognized the users' needs and self-esteem in envisioning their personhood. They understood the self-image and needs of the users and provided care that respected their self-esteem. Esteem needs are fulfilled by consistent respect from others and evoke confidence, usefulness, strength, and competency. The nurses and welfare workers in this study praised the users with words (eg, “That's it, you're doing so well!”; “Nice!” “Good for you!”). Because the nurses respected the users' self-esteem, they began to make a voluntary effort to express themselves more and be recognized by others.

In this way, the perceived capacity to control, cope, and take personal decisions on how a person lives their daily life, following their own norms and preferences, is defined as autonomy.33 The nurses at the day care center provided care that nurtured the users' personhood and promoted their wishes. This care assisted the users' autonomy by enabling them to have a purpose at the day care center (eg, “I want to have fun at the center,” “I want to do well in suctioning and activities”) and enjoy their lives actively and fully. Autonomy requires nurturing self-determination in an environment where people can think and decide for themselves.34

However, users are susceptible to health problems and even their desire to do something may cause uncontrollable and life-threatening myotonia. Therefore, the users at the day care center were in a precarious situation in which their myotonia or respiratory conditions could worsen at any time.

Respecting and supporting autonomy is guaranteed by Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. However, persons with chronic illness may significantly and permanently interfere with their emotional growth and development,35 including the sense of autonomy. In a recent study, mobility limitations are negatively associated with the level of autonomy.36

Therefore, when nurses in nursery schools communicate with users, they look for not only the wishes and needs of the users but also for abnormal signs, form a unique image of the users, and respect their independence. They are involved in all aspects of communication and treatment.

This study revealed a structure in which the nurses helped the users facilitate their autonomy by fulfilling their physiological and safety needs to help them stay healthy, deepening their relationship through care, and providing care that respected their self-esteem. This type of care may be defined as the involvement with users that forms the foundation of their autonomy.

Emancipation from the “shame culture” through the growth and trust of the users

In this research, the nurses and welfare workers at the day care center provided care that promoted the users' autonomy. This care enabled the users to enjoy life, created a connection between the mothers and the day care center, and allowed both the users and their mothers to trust others physically and emotionally and lead their own lives. The care at the center facilitated their autonomy and trust in the center, making normalization a reality for the users and their mothers and emancipating them from the “shame culture.”

The first reason is promoting the users' autonomy through this care enabled the users' self-expression when their parents were not present. As a result, the mothers have been able to leave their physically and mentally life-threatening children at the day care center. The users enjoy separate lives from them, find joy in their growth that took place away from the parents, and lead the lives that they had wanted. The principles of normalization include living a regular day, week, and year, having regular developmental experiences, individual dignity and the right to self-determination, sexual relationships, and the right to economic and environmental standards.37 The resulting daily lives of the users and their mothers in this study signified the achievement of normalization, in which the users' rights and dignity were protected in a conducive environment.

The second reason is the nurses in this study were able to attain normalization for the users, who were susceptible to life-threatening situations, through health management with consideration for the families' capacity for caregiving and health management and thorough care that promoted for the users' autonomy. A previous study found that persons with PIMD with high medical needs, such as the users in this research, were expected to stay home under the care of their mothers instead of nurses, with the nurses creating guidance plans for at-home respiratory management.16 The “homes” of patients who required medical care resembled a hospital room with breathing and suctioning equipment and oxygen and that their families were required to provide 24-hour care.38 In Japan, mothers of persons with PIMD must stay vigilant 24 hours a day, without rest or respite, to protect their children from life-threatening situations.17 As a result, mothers providing home care were fatigued to the point of not being able to sense their fatigue or physical condition.39

The care provided by the nurses at the day care center not only accommodated the users' needs and conditions but also was based on the assessment of the families' capacity for caregiving and health management. Moreover, the care at the center followed how the families provided care at home to not disturb the rhythm of the users' lives at home while maintaining their health. This involvement by the nurses reduced the anxiety of the families, especially the mothers, and strengthened their trust in the day care center. As a result, mothers have been able to leave their children with life-threatening physical and mental conditions at the day care center.

In Japan, where the “shame culture” persists, there is a history of children with disabilities being hidden from public view and subjected to prejudice and discrimination.20 Mothers talk about difficulties and regret about the congruence between intentions of persons with PIMD and parental judgment, indicating that they think parents are helpless.40,41 This is the difference between the results of the study and those of Western countries.32 In Japan, persons with PIMD and their mothers are isolated in the Japanese culture of shame.20 The care of persons with PIMD is often left to the mother alone, with fathers and siblings staying away, the community barely involved, and only a few local government services offering help.8,42 Mothers do not express to anyone their true feelings and weaknesses to avoid shame, which deepens their isolation.43 The lack of socialization of care in the culture of shame is shown in Japanese cultural history.20

In contrast, the care provided by the nurses and welfare workers at this day care center promoted the users' autonomy. It allowed their mothers to deepen their trust in the center and be comfortable leaving their children with life-threatening condition in the hands of others, making normalization a reality. In other words, the care provided by the nurses at this center emancipated the users and their mothers from the “shame culture.”

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE

The creation of care that emancipates persons with PIMD and their families from the Japanese “shame culture” is of great significance. Implications for the practice of this care include the following.

First, in communicating with users, it is important to observe their subtle reactions, understand what they mean and what is needed, and communicate the understanding back to them verbally or by providing care. This interaction is important as the foundation of the care.

Second, to create care that promotes autonomy in users at a day care center, managing their health is fundamental for sustaining their personhood at the center and home. Therefore, it is necessary to consider that the level of care provided at the center is not attainable at home and provides care that looks at the totality of the lives of users and their families.

Finally, the participants in this study were users with high medical needs, whose numbers have increased in recent years. This research indicates that their daily life and medical needs are inextricably connected and that care at a day care center needs to strike a balance between those needs.

LIMITATIONS OF THE RESEARCH AND FUTURE RESEARCH ISSUES

This study examined the practice at a day care center in Japan. Because of the characteristics of the center, the ages of the users were limited to 18 years and older. The participating family members were mostly mothers. To study communication and care involving subjects of different ages and their families, and to gain a better understanding of the effects of their culture and experiences, it is necessary to conduct research at day care centers for infants, after-school childcare facilities, and other types of facilities, while including family members other than mothers in the research.

The nurses and welfare workers who participated in this study had 10 or more years of experience in caregiving for individuals with profound disabilities, and the participating day care center was a model business facility. Since communication with persons with PIMD is a challenge regardless of the language or culture, it is also necessary to look into the creation of care by nurses and welfare workers in other countries for implications regarding care and education that promote normalization.

Few studies have examined care with active participation by users. In Japan, community-based comprehensive care corresponding to the users in this study has just started. In the future, more research is needed for persons with PIMD and their family home care where diverse professions are involved at different times.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the researcher conducted fieldwork at a day care center for persons with PIMD in Japan to demonstrate how the nurses and welfare workers communicated with persons with PIMD (“users”) and their mothers to create care. The fieldwork revealed the following 5 domains: (1) involvement by the nurses to perceive abnormal signs in the users; (2) involvement to understand the wishes and intentions of the users; (3) involvement to better understand users' wishes; (4) creation of care that promoted the growth of the users; and (5) creation of the parents' joy and trust through the growth of the users. Through communication with the users, the nurses and welfare workers at the center provided care that encouraged self-expression and shared their understanding of their personhood and wishes. As a result, the users were able to work on their wishes and the formation of their own care actively. This type of care may emancipate the users and their families from the Japanese “shame culture” and enable them to lead ordinary daily lives, creating their own full lives. This research provides recommendations for ways to support users and their families to emancipate them from the Japanese “shame culture” and facilitate their autonomy.

Footnotes

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the persons with profound intellectual multiple disabilities and their families and the nurses and welfare workers at the day care center for their cooperation with this research. I am also immensely grateful to Mayumi Tsutsui, Emeritus Professor, the Japanese Red Cross College of Nursing, for their supervision.

Conflict of interest and sources of funding: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otsuki S, Kuroda S, Aoki S. Mental retardation. In: Gomi S, ed. Clinical Psychiatry. 5th ed. Bun ko do; 2003:334–351. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein KD, Tigerman E. Language and Communication Disorders in Children. Toshindo; 1993/1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T. Communication strategies with individual with profound multiple disabilities: a literature review. J Jpn Soc Child Health Nurs. 2011;20(1):141–147. doi:10.20625/jschn.20.1_141 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilder J, Axelsson C, Granlund M. Parent-child interaction: a comparison of parents' perceptions in three groups. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(21/22):1313–1322. doi:10.1080/09638280412331280343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koizumi R. The process of mothers' decision making for gastrostomy surgery for their children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities. J Jpn Soc Child Health Nurs. 2010;19(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato T, Ogura K, Fumiko H, Hayama K. Decided the tracheostomy for their children with severe mother and intellectual disabilities. J Severe Motor Intellect Disabil. 2014;39(1):93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuyama M, Kudo Y, Tanino M, Sawada N. Ishi sotu ga konnan na jusho sinsin shogaiji (sya) ni taisuru kangosi no kakawari ni tsuite. Nihon Kango Gakkai Ronbun syu. 2007;38:149–151. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirano M. Caring for totally nonresponsive seriously handicapped children who are respiratory-system dependent—focus on importance of catching “the child's voice.” Jpn Acad Nurs Sci. 2005;25(4):13–21. doi:10.5630/jans1981.25.4_13 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichie K. The process by which nurses working at an institution for severely handicapped children understand the responses of severely handicapped children and individuals and achieve mutual understanding. Jpn Soc Nurs Res. 2008;31(1):83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimono J, Endou Y. The study on nurse's motivation to providing care continuously to serious conditions of patients with mental and physical handicap. J North Jpn Acad Nurs Sci. 2009;12(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe R, Ooga A, Koike T, Katou T. No sanso kokan mapping wo mochiita jusyoji no Kyoiku shido koka no hyokaho. J Severe Motor Intellect Disabil. 2005;30(3):265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogawa T, Tajima M, Saitou N, Koitabashi K, Yanagi N. Cyo jusho sinsin shogaiji (sya) ni taisuru aroma massaji no kouka ni kansuru kenkyu. J Severe Motor Intellect Disabil. 2007;32(1):129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsubasa T. Jusho shinshin shogaiji no gainen to jittai. Jpn J Pediatr Med. 2015;47(11):1860–1865. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Iryoteki kea ga hitsuyou na jushoji heno jujitsu ni mukete. 2017' Iryoteki keaji nado no chiiki shien taisei kouchiku ni kakaru tantousha godo kaigi shiryo. Published October 16, 2017. Accessed October 25, 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12200000-Shakaiengokyokushougaihokenfukushibu/0000180993.pdf

- 15.Funahashi M. Jusho shinshin shogaiji no nichijo seikatsu deno kenkou kanri. In: Egusa Y, ed. Jusho Shinshin Shogaiji Ryoiku Manyuaru. 2nd ed. Ishiyaku shuppan; 2005:207–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk S, Glendinning C, Callery P. Parent or nurse? The experience of being the parent of a technology-dependent child. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(5):456–464. doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamabe F, Sato T, Ogura K, Hayama K. Storytelling of mothers of severe motor intellectual disabilities persons—effect of gastrostomy, tracheostomy and/or mechanical ventilation on daily lives. J Severe Motor Intellect Disabil. 2008;33(3):347–354. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okada K. Jusho shinshin shogaiji (sya) gainen no seiritsu zenshi. In: Okada K, ed. Jusho Shinshin Shogaiji (sya) Iryo Fukusi no Tanjo. Ishiyaku shuppan; 2016:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benedict R. The Chrysanthemum and the Word. Kodansya gakujutu bunko; 1972/2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi A. Sappro to tachikawa no kodoku shi ni omou. Akita Ken Isikai Shi. 2012;1398:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabinet Office. Shogaiji sesaku no gaikyo. Heisei 21nendo [Annual Report on Government Measures for Persons With Disabilities. Cabinet Office Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabinet Office. New developments in policies for persons with disabilities. Annual report on government measures for persons with disabilities [summary]. Published 2014. Accessed October 25, 2020. https://www8.cao.go.jp/shougai/english/annualreport/2014/index-pdf.html

- 23.Nonaka T, Touyama R, Hirata T. Managing Flow: The dynamic Theory of Knowledge-Based Firm. Toyo keizai INC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. 6th ed. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton QM. Ethnography and autoethnography. In: Patton QM, ed. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Sage; 2015:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Shin you sya; 1995/1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lincoln SY, Guba GE. Establishing trustworthiness. In: Lincoln SY, Guba GE, eds. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage; 1985:289–331. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakanishi K, Matsushima N. Vaitaru chettku to kansatsu no ryuui-ten. In: Asakura T, ed. Jusho Shinshin Shogaiji no [Total Care of the Persons With Profound Intellectual Multiple Disability]. Herusu syuppan; 2006:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiramoto A. Zenshin kanri no zennan teki na tyuuiten. Jpn J Pediatr Med. 2008;4(10):1589–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forster S, Iacono T. Disability support workers' experience of interaction with a person with profound intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2008;33(2):137–147. doi:10.1080/13668250802094216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson J, Voss H, Melissa J, Bloomer J. Placing the preferences of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities at the center of end-of-life decision making through storytelling. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil. 2019;44(4):267–279. doi:10.1177%2F1540796919879701 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruithof K, Willems D, Etten-Jamaludim VF, Olsman E. Parents' knowledge of their child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: an interpretative synthesis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2020;33(6):1141–1150. doi:10.1111/jar.12740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshinaga N. Designing lessons for teachers to support and develop learners' “autonomy and independence”: by redefining the concepts of autonomy and independence. Annu Rep Stud. 2020;71:51–62. doi:10.15020/00001937 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashiwame R. The best interests of the child. Syukutoku Univ Bull. 2019;53:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000018093.pdf

- 36.Elad D, Barak S, Silberg T, Brezner A. Sense of autonomy and daily and scholastic functioning among children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;80:161–169. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nirje B. How I came to formulate the normalization principle. In: Flynn JR, Lemay AR, eds. A Quarter-Century of Normalization and Social Role Valorization. University of Ottawa Press; 1999:17–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang KW, Barnard A. Technology-dependent children and their families: a review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):36–46. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hase M. A study on recognition of health conditions by mothers caring for patients with severe motor and intellectual disabilities at home. J Severe Motor Intellect Disabil. 2009;34(3):383–388. [Google Scholar]