Abstract

The development of a superhydrophobic and, even, water-repellent metal alloy surface is reported utilizing a simple, fast, and economical way that requires minimum demands on the necessary equipment and/or methods used. The procedure involves an initial irradiation of the metallic specimen using a femtosecond laser, which results in a randomly roughened surface, that is subsequently followed by placing the item in an environment under moderate vacuum (pressure 10–2 mbar) and/or under low-temperature heating (at temperatures below 120 °C). The effects of both temperature and low pressure on the surface properties (water contact angle and contact angle hysteresis) are investigated and surfaces with similar superhydrophobicity are obtained in both cases; however, a significant difference concerning their water-repellent ability is obtained. The surfaces that remained under vacuum were water-repellent, exhibiting very high values of contact angle with a very low contact angle hysteresis, whereas the surfaces, which underwent thermal processing, exhibited superhydrophobicity with high water adhesion, where water droplets did not roll off even after a significant inclination of the surface. The kinetics of the development of superhydrophobic behavior was investigated as well. The findings were understood when the surface roughness characteristics were considered together with the chemical composition of the surface.

Introduction

Superhydrophobic surfaces have attracted significant scientific interest due to their importance in both fundamental research and practical applications;1−5 such applications include self-cleaning surfaces,6−9 antifogging materials,10,11 anti-icing,12,13 antifouling,14 sensing,15,16 microfluidics,17−19 biomedical applications,20,21 fabrics,22−25 etc. The existence of hierarchical surface roughness and the appropriate chemical composition are critical parameters that control the behavior.1,6,26−31 Surfaces can be described as superhydrophobic and water-repellent (with low water adhesion) when the contact angle of a water droplet is as high as 150°, whereas the contact angle hysteresis is less than 10°1,27,32 or as superhydrophobic with high water adhesion, when the water contact angle is similarly as high as 150° and the contact angle hysteresis is high.33−35 The inspiration for developing superhydrophobic surfaces comes from nature; a plant that is extensively studied for its properties is the lotus leaf (Nelumbo mucifera), which is characterized by high contact angle, ultralow water adhesion, and self-cleaning properties.27,36 In addition to the lotus leaf, there are a wide variety of plants and insects that exhibit amazing properties such as Rosa montana, Strelitzia reginae, Oryza sativa leaves, water striders, Nambibian beetles, cicadae, and butterfly wings.37−40 A special category among those are the parahydrophobic plants,41 which exhibit high contact angles, but much less than 150° (e.g., advancing angle of ∼110°), with high water adhesion (contact angle hysteresis of 27°) such as various thermogenic plants. Fabricating superhydrophobic surfaces is relevant for very different materials like polymers, ceramics, and metals; depending on the material, various techniques were utilized to achieve it, such as photolithography, nanoimprinting, laser beam machining, wet chemical etching, chemical coating, and molding.6,42−46

Among the various materials, metals and metal alloys have been widely utilized in many applications because of their mechanical and thermal properties. However, the surface of metals and metal oxides is usually hydrophilic due to its high surface energy; in this case, the introduction of hierarchical roughness or geometrical patterns rather enhances the hydrophilicity and the application of a low-surface-energy material as coating is necessary to alter the behavior.47 Titanium and its alloys are especially important structural metals, which, because of their excellent physicochemical properties like low density, high specific strength, good resistance to corrosion, and nonmagnetic character, are widely used in many applications including aerospace, marine applications, and in biomedicine as implant materials and/or as dental and orthopedic prostheses.48,49 Ti6Al4V is the most frequently used titanium alloy in aircraft structural parts, aero-engines, low-pressure steam turbine materials as well as in the biomedical field due to its excellent mechanical properties such as high modulus of elasticity, fatigue strength, fracture toughness, as well as corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, and bioadhesion.50−52 Altering the surface properties of titanium alloys and developing titanium-based superhydrophobic materials can raise even further its value in the aircraft and shipping industries. It is noted that, in such applications, utilization of an organic coating to alter the surface behavior is, in most cases, not a desirable option because of the mechanical softness of the coatings and the deterioration of its wetting properties with time.

To fabricate superhydrophobic metallic surfaces, different methods have been utilized, such as solution immersion, sol–gel, chemical etching, and electrodeposition.53−59 However, these techniques have the disadvantages of being complicated, expensive, and resulting in poor mechanical properties of the fabricated surface structures. Recently, laser surface modification is considered as one of the simpler and most effective approaches to directly produce superhydrophobic surfaces on a wide variety of metals since it provides precise control of the three-dimensional hierarchical micro/nanostructures.60 It is a noncontact, nonpolluting, cost-effective, and flexible method that offers efficient and high precision texturing. At the same time, it does not require a specific environment as high vacuum or clean room facility during the process, and it can create a multiscale hierarchical roughness in a one-step process.61 Various works have investigated laser structuring of metal substrates, such as Ti6Al4V,62 stainless steel,63,64 copper,65 magnesium alloy,66 aluminum,67 and others, and demonstrated the formation of hierarchical structures or laser-induced periodic surface structures (LIPSS).68

It is well accepted that freshly processed laser metal surfaces are hydrophilic69−74 due to the formation of metal oxides with high surface energy.75−78 One way to alter this is the application of an appropriate coating utilizing a low-surface-energy modifier.79,80 Alternatively, leaving the irradiated material in ambient air can modify the properties of the surface from superhydrophilic to hydrophobic or even superhydrophobic; however, this procedure, although being very eco-friendly and not requiring any further processing, takes a very long time to be completed, which ranges between a few days to a few weeks.69,70,72,73 In a few works, researchers attempted to shorten the time for the alteration of the behavior using either very high vacuum71,75−78,81 or high temperatures.74,82 In most of those works, the authors investigated the effect of the irradiation characteristics on the shape, size, and periodicity of the obtained surface structures and, thus, on the water contact angle; the effect of an environment rich in CO2, O2, N2, H2O, or organic moieties on the hydrophilic to superhydrophobic conversion was investigated as well.69,71,72 The modification of the time scale for obtaining hydrophobic properties was attributed to the effective adsorption of hydrocarbons due to the low partial vapor pressure of water. However, there has not been any detailed investigation of the contact angle change as a function of the value of the pressure (vacuum) or of the residence time under a low-pressure environment.

In this work, superhydrophobic metallic surfaces are fabricated using a very simple procedure. More specifically, Ti6Al4V alloy surfaces were initially irradiated with femtosecond laser pulses. This was followed by placing the surfaces under a low vacuum, which was easily achieved utilizing a rotary pump, and/or by heating at low temperatures. The surface immediately after the irradiation is superhydrophilic with water droplets spontaneously and completely wetting it. However, heating of the irradiated surface at different temperatures results in a modification of its surface properties and in the manifestation of a superhydrophobic behavior with a contact angle of 149 ± 2°, especially for temperatures higher than 120°. A similar effect was observed when an irradiated surface is placed in a vacuum chamber under relatively weak vacuum conditions (pressure 10–2 mbar); after a minimum of 3 h, the surface was converted to a superhydrophobic one with a contact angle of 149 ± 1°. Despite the similar values of water contact angle after processing under vacuum or heating at a low temperature, a different behavior is observed concerning the ability of the surfaces to repel water. The superhydrophobic surfaces obtained following heating show a significantly high contact angle hysteresis, thus showing high water adhesion, whereas the ones exposed to low vacuum exhibited very low contact angle hysteresis, thus showing water-repellent behavior. Moreover, the effect of the time that the surface remains in air before further processing (in vacuum or at a temperature) was investigated. The observed behavior can be understood taking into account the change in the surface chemical composition because of hydrocarbon absorption due to the post-irradiation processing that is amplified by the effect of the surface micro/nano-roughening by the laser irradiation.

Experimental Section

Materials and Experimental Techniques

The metal alloy Ti6Al4V, kindly provided by UAB FEMTIKA, Lithuania, is utilized; samples were flattened and cleaned with acetone prior to laser irradiation. The laser micro/nanostructuring83,84 was performed under atmospheric condition by a high-power femtosecond laser (Pharos, Light Conversion) with a Gaussian pulse shape, a wavelength of 515 nm, a repetition rate of 20 kHz, and a pulse energy of 6 μJ/pulse (power of 120 mW) with a pulse duration 167 fs and p-polarization. The laser beam was focused on the surface of the sample with a 10× Nikon microscope objective lens, NA 0.25, and a working distance of 5.6 mm that resulted in a final spot size of 2.5 μm (FWHM). This resulted in a fluence on the surface of 42.3 J·cm–2. Aerotech XYZ linear nanopositioning stages that provide nanometer resolution, accuracy, repeatability, and in-position stability were utilized; their linear moving velocity was set to 5 mm/s, which leads to an approximation of 10 pulses/spot in one direction, while in the vertical direction, steps with 2.5 μm size were made to have a half overlapping between lines. Following the laser processing, the surfaces were blown with air to remove all possible debris created by the irradiation. The laser-processed samples were either placed in a low vacuum (of the order of 10–2 mbar) for different time intervals or heated under various low temperatures.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

The surface morphology of the Ti6Al4V metal alloy with dimensions of 5 × 5 mm2 was imaged by a JOEL, JSM-6360LV scanning electron microscope (SEM), whereas the surface chemical composition was evaluated by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The microscope used has a high resolution of 3.00 nm at 30 kV, with an accelerating voltage from 0 to 30 kV and high focal depth (×5 up to 300.00). The magnification of the images for the samples was ×200 and ×1.000 for 20 kV accelerating voltage.

Contact Angle Measurements

The wetting properties of the surfaces were investigated via static contact angle measurements of sessile water droplets on the specimens using a video-based static contact angle computing device (OCA 15 Plus, Data Physics Instruments). The hysteresis of the water contact angles of the droplets on the metallic surfaces was evaluated by the tilt plate method. Distilled deionized water droplets of ∼12 μL in volume were used for the measurements at ambient temperature and pressure. An average of at least five measurements at different positions on the laser-patterned area has been performed in all cases.

Results and Discussion

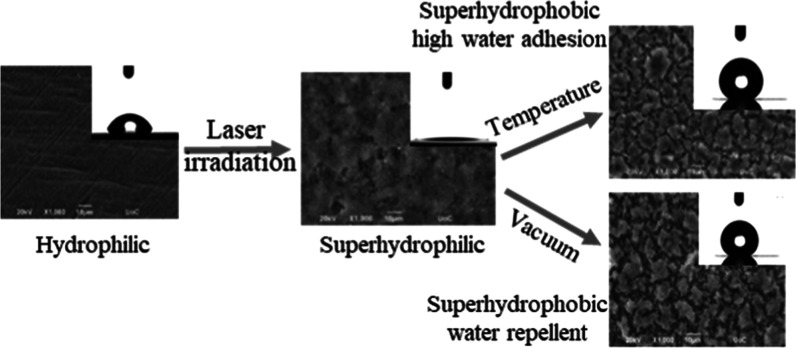

Figure 1 shows photographs of representative water droplets during the contact angle (CA) measurements on a Ti6Al4V surface together with the respective images of the surface morphology prior (Figure 1a,b) and following (Figure 1c,d) laser irradiation. The untreated smooth surface can be characterized as hydrophilic exhibiting a contact angle of about 60 ± 2°; it is noted that this value is the average of at least five measurements at different positions on the surface. Its surface energy was evaluated as σ = 40.7 ± 0.3 mN/m utilizing the OWRK (Owens, Wendt, Rabel και Kaelble) method using four different fluids (water, glycerol, ethylene glycol, and dimethylsulfoxide). The topology of the Ti6Al4V surface was imaged by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as shown in Figure 1b, where the smooth surface of the untreated alloy is demonstrated.

Figure 1.

Photographs of representative water droplets on a flat Ti6Al4V surface (a) and immediately after laser irradiation of the Ti6Al4V surface (c) and the corresponding SEM images of a flat (b) and a micro/nanostructured (d) Ti6Al4V surface.

During direct fs-laser writing, the laser–matter interaction leads to the removal of material (ablation) and, ultimately, to the formation of random micro/nanostructures on the surface. The SEM image of the irradiated surface, shown in Figure 1d, shows that significant roughness has been developed on the surface and emphasizes the difference in its topography from the corresponding one of the nonirradiated surface. When the contact angle measurement is performed immediately after the irradiation, the water drop completely wets the surface, making the determination of the contact angle value very difficult (Figure 1c); this can only be estimated to be smaller than ∼5°. Therefore, the irradiation results in superhydrophilic surfaces. The change in the wetting behavior of the surface can be attributed both to the increased roughness as a result of the femtosecond laser irradiation and to the formation of polar functional groups that are formed during the ablation process. It is noted that according to the Wenzel model that assumes a homogeneous wetting, roughness makes a hydrophilic surface even more hydrophilic; therefore, the micro/nanostructured surface right after irradiation belongs to the Wenzel regime of wettability. The observed increase in hydrophilicity following laser irradiation is in agreement with previous investigations on various metallic materials.69−74

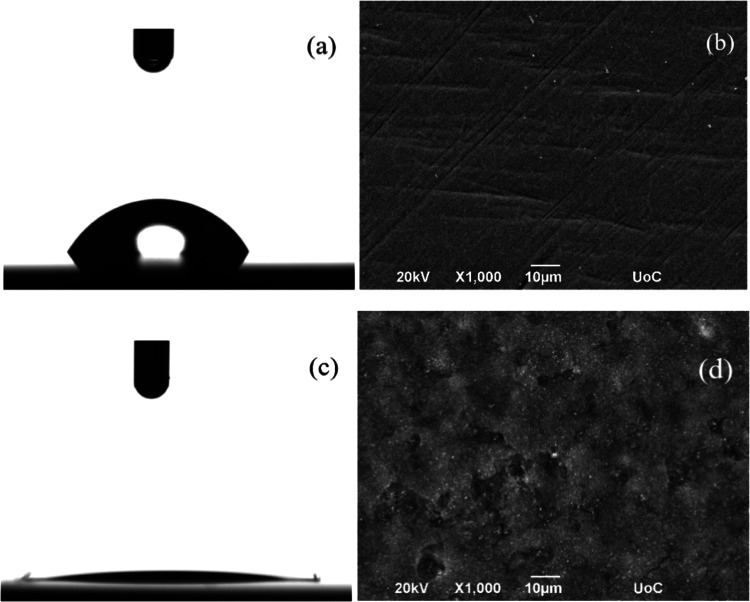

Following the irradiation, the surface was left under ambient conditions for variable time intervals and the wetting properties were evaluated. Figure 2a,b shows a photograph of a representative water droplet during the contact angle measurement and a SEM image for the surface, which was left in air for 32 days after laser irradiation. A significant increase in its hydrophobicity is observed from the state immediately after irradiation; the contact angle has reached a value of 129 ± 2° (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Photographs of representative water droplets on a Ti6Al4V surface 32 days after irradiation and (b) the corresponding SEM image. (c) Water contact angle values as a function of time that a surface remains under ambient conditions following the femtosecond laser irradiation. Error bars are included although they are smaller than or similar to the size of the points. (d) Photographs of representative water droplets on a Ti6Al4V surface 82 days after its irradiation and (e) the corresponding SEM image.

Figure 2c illustrates the dependence of the measured contact angles as a function of time the specimen is left in air following irradiation; the contact angle values increase systematically from its initial superhydrophilic behavior up to a certain value during the first 20 days after the irradiation, whereas for more or less the next 40 days, the surface properties remain unchanged as the value of the water contact angle remains constant and eventually starts to decrease again. Therefore, when an irradiated surface remains at room temperature and pressure in open air, its wetting properties can be altered due to its contamination by organic molecules that exist in the environment. However, this property is not permanent.

The instability of the surface over time can be attributed to the fact that the surface begins to wear out (Figure 2e) leading to a decrease in contact angle (Figure 2d) that reaches the value of 90 ± 1° after 82 days. The morphology of the surface as soon as it is irradiated is somewhat “crowded” (Figure 1d), resulting in a superhydrophilic behavior (Figure 1c). Over time, the morphology changes and appears to “solidify”, acquiring hydrophobic properties (Figure 2b). However, after ∼65 days, the contact angle begins to decrease because the surface loses its homogeneity. The increase in the water contact angle on a freshly irradiated surface that has remained in ambient air has been reported in the past, as well as the long time that it takes until the surface becomes hydrophobic;69,70,72,73 however, to our knowledge, this is the first time that it is reported that this change is not permanent but it deteriorates with time; this is a finding that would prohibit the use of such surfaces in current industrial applications.

Effect of Heating Treatment

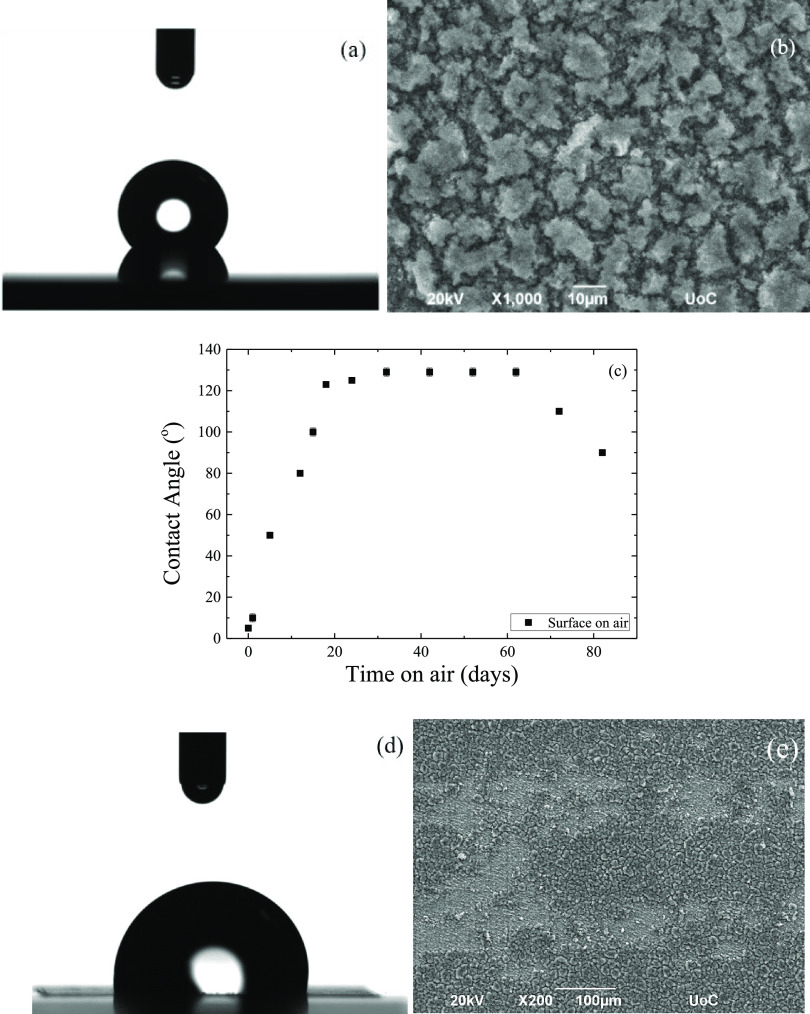

The irradiated metal alloy surfaces were placed in an oven at various temperatures between 25 and 200 °C for different time intervals up to 96 h, and their wetting characteristics were investigated. Figure 3 shows an image of a representative water drop on an alloy surface that has remained in an oven at 120 °C for 24 h after irradiation and its corresponding SEM image.

Figure 3.

(a) Photograph of a representative water droplet on a Ti6Al4V surface that was heated at 120 °C for 24 h after irradiation and (b) the respective SEM image.

The measured water contact angle is 149 ± 2°, i.e., heating the surface at this temperature turns the surface superhydrophobic. At the same time, the morphology of the surface shows certain heterogeneities that resemble the topography of a surface that was left at RT for more than 30 days after irradiation (Figure 2b, with higher-magnification images shown in Figure S1). Note that, when a flat surface is similarly heated, no significant change is observed either in its surface properties (the water contact angle is measured as 65 ± 1°) or in its surface morphology (shown in Figure S2).

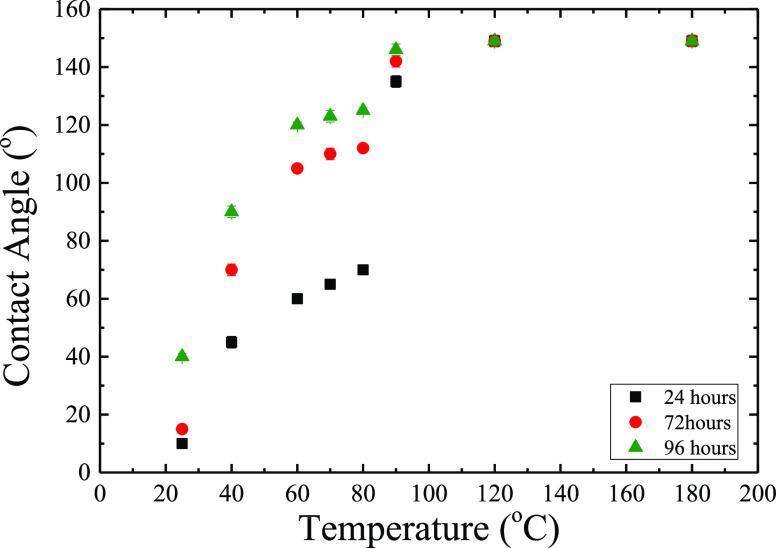

The modification of the wetting behavior of the irradiated surface by heating depends on both temperature and residence time at that temperature. The temperature dependence of the contact angle is shown in Figure 4 for various times the surface remains at each temperature. As temperature increases, the water contact angles increase and, above 100 °C, they reach values of ∼150°. When an irradiated surface is left at each temperature for 24 h, the water contact angle values change from ∼10° (complete wetting) when annealed at 25 °C to ∼70° when annealed at 80 °C (hydrophilic surface). Annealing, however, at even higher temperatures results in a sharp increase in the value of the contact angle, which reaches the value of 135 ± 2° when annealed at 90 °C and ∼150° when annealed at 120 °C or higher. When the irradiated surfaces remain at various temperatures for longer times, the behavior is qualitatively similar to contact angles increasing faster with annealing temperature for temperatures up to 80 °C followed by a smaller jump to values close to 149 ± 2° for higher annealing temperatures (from 112 ± 1 to 142 ± 2° for 72 h and from 125 ± 1 to 146 ± 2° for 96 h).

Figure 4.

Water equilibrium contact angles on a Ti6Al4V surface that was heated at different temperatures for various times. Error bars are included in all points although they are smaller than the size of the points.

If one prefers to analyze the contact angle data as a function of time for each temperature, one would notice that for temperatures higher than 120 °C, the maximum of the contact angle is obtained even when the sample remains at this temperature for 24 h, whereas any additional increase of the residence time for these temperatures does not result in any further effect on the contact angle. At 90 °C temperature, the contact angle is already high enough (135 ± 2°) during the first 24 h, and it shows a weak dependence on residence time since it reaches the value of 146 ± 1° after 96 h. At lower temperatures, however, the contact angle after 24 h treatment is even lower and the time to reach the maximum value is assumed to require much longer than 96 h (since it was not reached in any of the cases). Moreover, in the extreme case of the surface that has remained at room temperature, the maximum value of the contact angle was not achieved even after ∼60 days when the deterioration of the surface had started, as discussed above (Figure 1c). It is noted that, when the surface that has undergone a heating treatment is immersed in water, no effect is observed on the measured contact angles, whereas, when it is immersed in ethanol, the water contact angle values are reduced to 120 ± 1°.

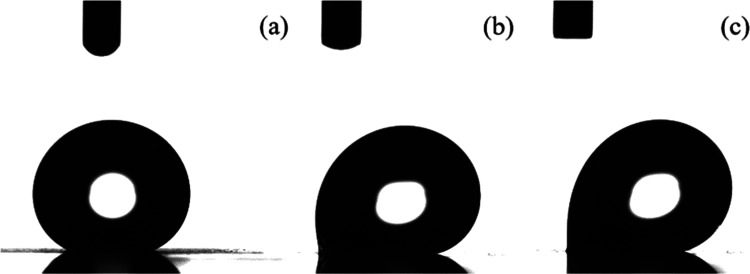

Complete characterization of the wetting properties of a surface requires the measurement of the contact angle hysteresis besides the measurements of the equilibrium contact angle. To measure the contact angle hysteresis, a water droplet is placed on the surface and, then, the OCA system begins to tilt until the drop begins to roll. Figure 5 shows photographs of representative water droplets on a surface that had remained at 120 °C for 24 h (i.e., for a surface that shows a superhydrophobic behavior) as deposited on the surface, where it shows a 149° contact angle (Figure 5a), at a tilt angle of 45°, where the difference between the advancing and the receding angles are shown (Figure 5b) and at a tilt angle of 90°, where, evidently, the droplet still does not roll off the surface (Figure 5c). A video of the behavior of a water droplet during the tilting of the surface that has remained at 120 °C for 24 h is shown in the Supporting Information as Video S1. Therefore, the particular Ti6Al4V surface that was heated at a relatively high temperature has become superhydrophobic with, however, high water adhesion, and it can be characterized as exhibiting the rose petal effect. In contrast, when Al74 or Cu82 surfaces were irradiated with a nanosecond laser and were, subsequently, heated at 100 °C for 24 and 13 h, respectively, superhydrophobic surfaces with low water adhesion (low sliding angles) were obtained.

Figure 5.

Photographs of a representative water droplet on a Ti6Al4V surface that was heated at 120 °C for 24 h after irradiation (a) as deposited onto the surface, (b) when the surface is at a tilt angle of 45°, and (c) when the surface is at a tilt angle of 90°.

Effect of Vacuum Treatment

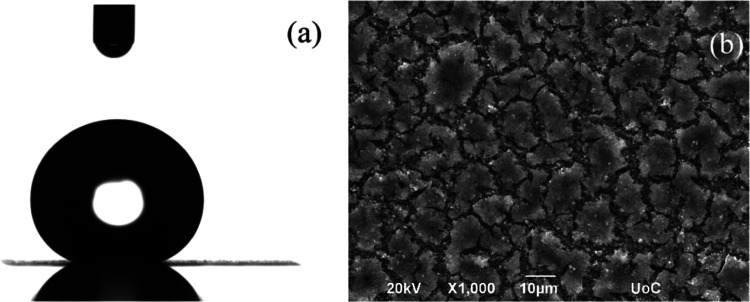

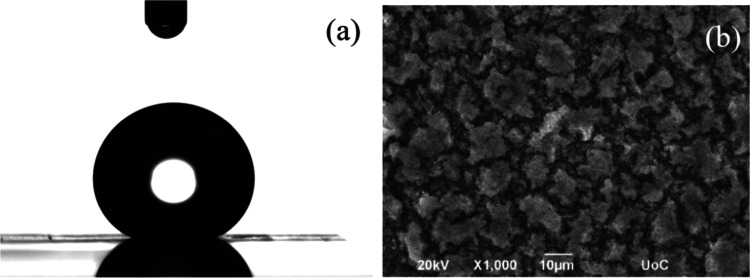

Figure 6 shows an image of a representative water droplet on an irradiated Ti6Al4V surface that was placed in a vacuum oven for 24 h under dynamic conditions following its irradiation together with a SEM image that illustrates its topography. It is clear that residing in vacuum rendered the initially superhydrophilic surface after irradiation to a superhydrophobic one with a contact angle of 149 ± 1° (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

(a) Photograph of a representative water droplet on a Ti6Al4V surface that remained under dynamic vacuum for 24 h after irradiation and (b) its corresponding SEM image.

At the same time, the morphology of the surface (Figure 6b, with higher-magnification images shown in Figure S3) is significantly different from the respective one of the irradiated surface right after irradiation, whereas it resembles the one that has been heated at high temperatures (e.g., Figure 3b). It is noted that, when a smooth nonirradiated surface remains under the same vacuum conditions, no effect on its wetting properties was observed and its contact angle was measured at 67 ± 1°, i.e., it showed a behavior very similar to a surface that did not reside under vacuum; this is illustrated in Figure S4. Therefore, the roughness that was obtained via irradiation is a critical parameter to alter the wetting properties of the metal alloy.

Considering the possibility that some kind of contamination of the treated surface may have occurred due to the lubricating oil of the vacuum pump, the procedure was repeated placing the surface in a chamber where the vacuum is attained by an oil-free pump. The latter surface exhibited a similar morphology to the one shown in Figure 6b; thus, a similar effect on hydrophobicity could be anticipated. However, the surface that remains in the oil-free pump vacuum chamber did not show any increase in the contact angle, i.e., the water droplets continue to completely wet the surface. Therefore, it is the chemical composition of the two surfaces that should be different since the morphology is similar but the contact angle and, therefore, the wetting properties are significantly different; the latter depends both on the composition and the roughness of the surface.

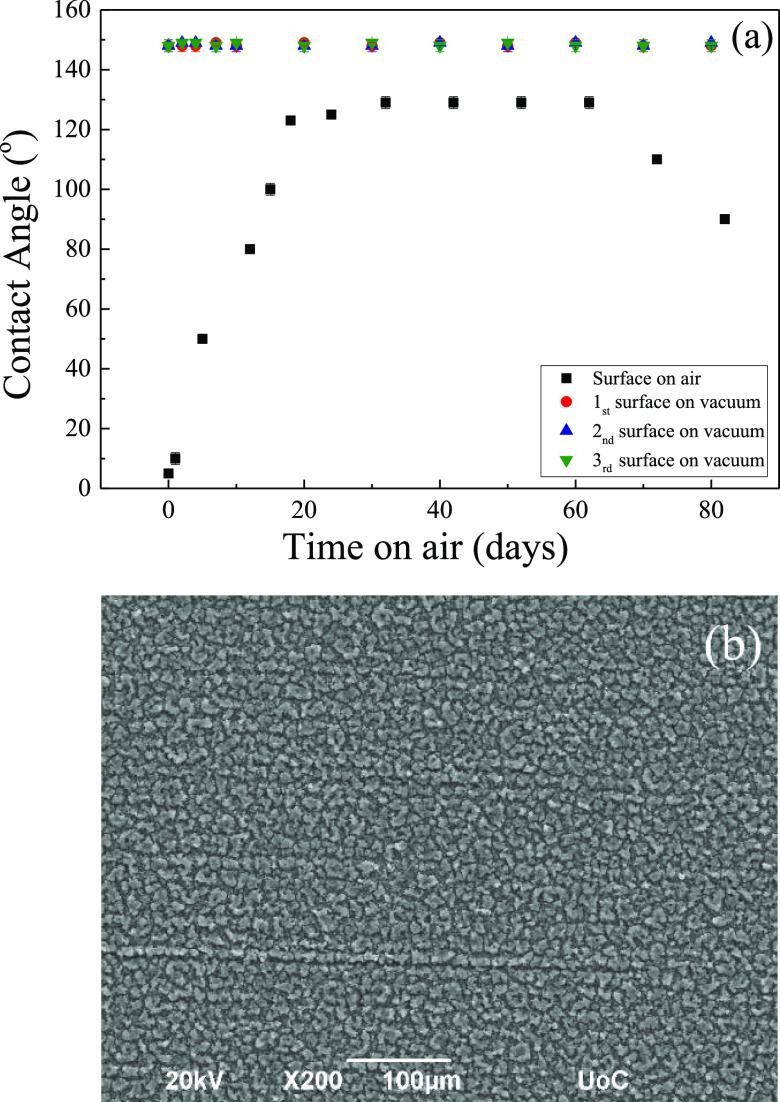

The stability over time of the wetting properties of the superhydrophobic surface after the vacuum treatment is of utmost importance. It is noted that, as discussed above, a deterioration of the behavior was observed following the initial increase in the contact angle for surfaces that had simply remained in air after irradiation. Figure 7a shows the equilibrium water contact angles on three different surfaces that resided under vacuum for 24 h after irradiation as a function of time in air after vacuum. The data illustrate the reproducibility of the measurements and the quality of the developed surfaces, which are very stable over time with contact angles showing constant values of 149 ± 1°. Thus, the obtained surfaces are significantly stable over time, in contrast to surfaces, which remained in air without having undergone any vacuum treatment at all. This is corroborated, as well, by the SEM image of a surface obtained after 82 days in air following its placement under vacuum for 24 h (Figure 7b). Moreover, it is noted that the water contact angles on the surfaces that remained under ambient conditions in air, even before their deterioration, are significantly lower than those on surfaces that remained in vacuum, showing smaller contact angles by ∼20°. In conclusion, when the surface is treated under vacuum, it acquires a large contact angle, which is stable over long times. Moreover, it is noted that when the vacuum-treated surface is immersed in water, no effect is observed on the measured contact angles, whereas, when it is immersed in ethanol, the water contact angle values are reduced to 127 ± 1°.

Figure 7.

(a) Equilibrium contact angle values as a function of the time that the surfaces have remained in air following 24 h under vacuum (red, blue, and green points) or directly (black points) after irradiation. Error bars are included in all cases although they are smaller than or similar to the size of the points. (b) SEM images of an irradiated Ti6Al4V after 82 days in air following its placement under vacuum for 24 h.

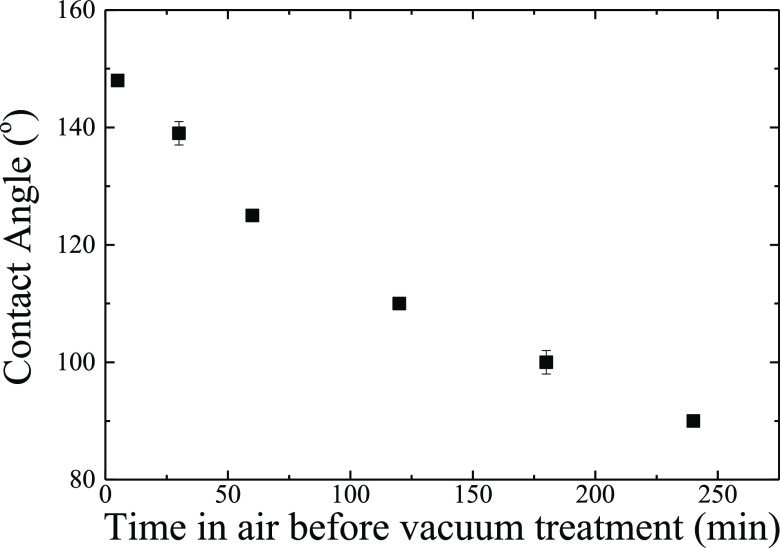

The parameters of the processing steps that a surface undergoes significantly affect the final wettability of the surfaces. Such parameters are related, on one hand, to the time between the surface irradiation and its placement under vacuum and, on the other hand, to the details of the processing of the surface under vacuum. Figure 8 shows the corresponding contact angle data of an irradiated surface as a function of the time that the surface remained in air before it is placed under vacuum for 24 h. It is clear that the longer the surface stays in air before it is placed under vacuum in the vacuum chamber, the smaller the contact angle that the surface reaches after 24 h under dynamic conditions. More specifically, when the surface is placed under vacuum immediately after irradiation, a superhydrophobic surface is developed with a contact angle of 149 ± 1°; however, if the surface remains in air for 4 h and, then, is placed under dynamic vacuum for 24 h, it barely becomes hydrophobic since the contact angle is measured as 90 ± 2°. Thus, to achieve superhydrophobicity, the surface should be placed under vacuum immediately following its irradiation.

Figure 8.

Equilibrium contact angle values as a function of the time that the surface remains in air before it is placed in vacuum under dynamic conditions for 24 h. Error bars are included even when they are smaller than the size of the points.

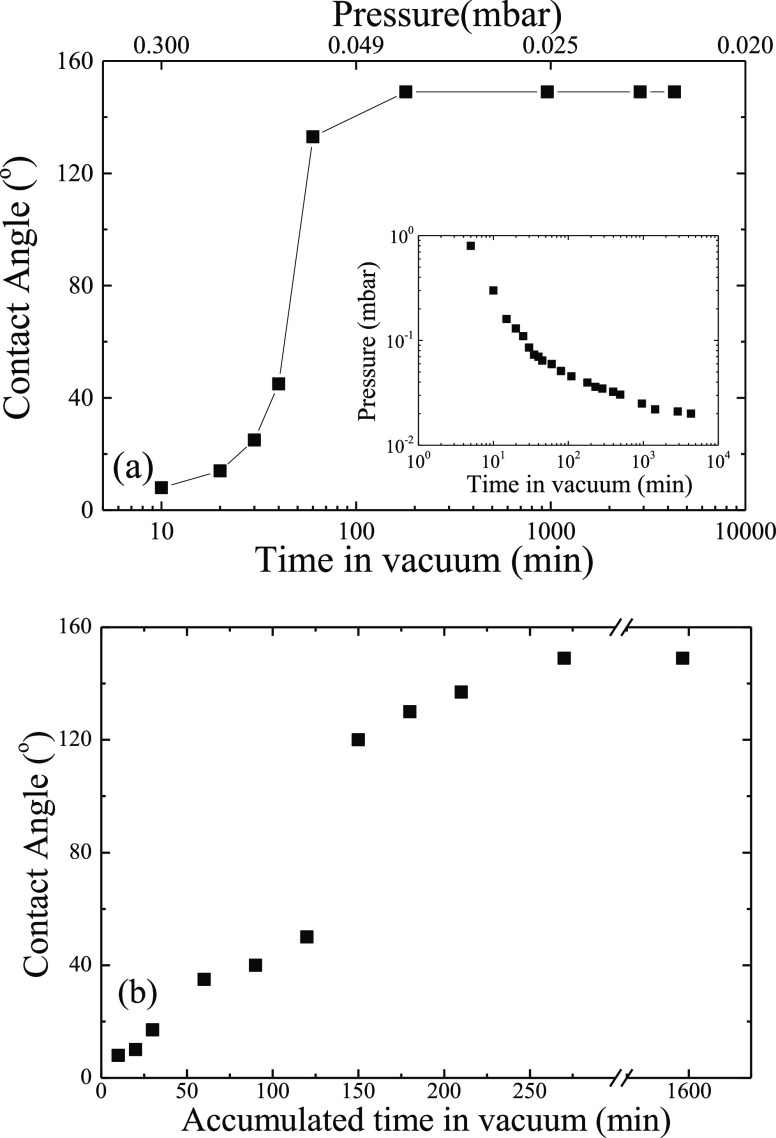

On the other hand, Figure 9a shows the water contact angle values on surfaces, which were introduced in the vacuum chamber immediately after irradiation and have remained continuously under dynamic vacuum for different time periods. The contact angles increase weakly for small time intervals, whereas a jump in the contact angle values is observed after ∼50 min and, finally, a plateau is reached with the maximum obtained contact angles being 149 ± 1°. More specifically, when the surface remains under vacuum for 40 min, the contact angle becomes 45 ± 1°, whereas when it remains for 60 min, i.e., 20 min longer, its value jumps to 133 ± 1°. Finally, it seems that staying in vacuum for 180 min is enough for the surfaces to reach the most superhydrophobic state expressed via contact angles of 149 ± 1°. Residing under vacuum for even much longer times does not result in any further increase in the contact angle.

Figure 9.

(a) Equilibrium contact angle values as a function of the total time that the sample remained in the vacuum chamber continuously (the surfaces were placed in vacuum immediately after irradiation). The inset shows the measured pressure inside the vacuum chamber as a function of pumping times. (b) Equilibrium contact angle values as a function of the total time that the sample remained in the chamber in a noncontinuous way (the surfaces were placed in vacuum immediately after irradiation). The error bars are smaller than the size of the points.

Figure 9b shows the static water contact angle values on surfaces that have been placed under vacuum immediately after irradiation not continuously but with intermediate breaks as a function of the accumulated times. A behavior similar to that of Figure 9a with increasing contact angles is observed as well. More specifically, for a total time from 10 to 120 min (measured in steps of 10–30 min), the contact angles increase weakly with time. However, following this initial increase, a jump appears in the contact angle value since, after 120 min total time, the contact angle is measured at 50 ± 2°, whereas after an additional 30 min (i.e., total time of 150 min), the contact angle has increased up to 120 ± 1°. After that jump, the contact angle keeps increasing, however, with a slower rate, reaching a maximum contact angle of about 149 ± 2° at a total time of ∼270 min. This is the maximum value of contact angle that can be obtained since it does not increase further even if the surface remains under vacuum for much longer times.

The fact that the contact angle increases and the superhydrophobic state is obtained faster when the surfaces reside under vacuum continuously compared to when they are placed in vacuum in discrete time intervals indicates that the critical parameter is not simply the time that the surface remains under vacuum but rather the air pressure, which is reached in the chamber; the longer the vacuum pump operates, the lower the pressure inside the vacuum chamber (inset of Figure 9a). Therefore, the difference in the contact angle values between the two experiments described above (continuous time intervals under vacuum, Figure 9a, and total time with discrete measuring slots, Figure 9b) can be explained by considering the values of the pressure in the chamber as a function of pumping time. When the vacuum pump starts, the pressure inside the vacuum chamber decreases continuously as a function of time as shown in the inset of Figure 9a. Therefore, at the beginning, the pressure has a high value, which decreases with time to the minimum value of ∼0.020 mbar when the pump is running continuously for 24 h. The top x-axis of Figure 9a illustrates the values of the pressure in the chamber for the various times the pump operates. It is clear that high values of the water contact angles correspond to the lower values of the pressure in the chamber. Moreover, the maximum value of contact angle of 149 ± 1° is obtained at a pressure of 0.039 mbar (corresponding to a pumping time of 3 h). In conclusion, by leaving the surface in the chamber for shorter times, the pressure in the vacuum chamber is not sufficiently low to provide a satisfactory effect on the hydrophobicity of the surface.

However, pressure is not the only parameter that influences the wetting properties of the surfaces; successive placing of the irradiated metal alloy even at the same pressure results in an increase in its hydrophobicity. As one can see in Figure 9b, when the surface is left under dynamic vacuum for 10 min, i.e., when the final pressure reached in the vacuum chamber is 0.3 mbar (from the inset of Figure 9a), a contact angle of 8 ± 2° is obtained; following the contact angle measurement and the subsequent placement of the surface back in the chamber for 10 min more (i.e., down to the same pressure as before), the contact angle increases to 10 ± 2°, whereas, after the third iteration, the contact angle increases to 17 ± 1°. After that, the surface was placed under dynamic vacuum for an additional 30 min, i.e., until a pressure of 0.085 mbar was reached (from the inset of Figure 9a). The contact angle was measured at 35 ± 1°, and then, it increased to 40 ± 2 and to 50 ± 1° after the second and third times the same surface remained for an additional 30 min each time, respectively. During the fourth iteration of 30 min, the contact angle displayed a jump from 50 ± 1 to 120 ± 2° and continued to increase up to 130 ± 2 and 137 ± 2° for more 30 min periods in vacuum. Finally, when the same surface was placed in vacuum for an additional 60 min, i.e., when a pressure of 0.059 mbar was reached, the maximum contact angle of 149 ± 2° is achieved. If one places the surface in the vacuum chamber for even more time, this does not have any further effect on its hydrophobicity and the contact angle does not increase anymore. Therefore, the sequence of processing steps, i.e., whether the surface is placed in vacuum continuously or with intermediate breaks, determines the changes in the surface properties of an irradiated surface and the enhancement of its hydrophobicity.

These findings can be easily explained if one considers the relation between pressure and time in the vacuum chamber. As shown in the inset of Figure 9a, when the surface is left under pumping for 10 min in the vacuum chamber, the pressure reaches the value of 0.3 mbar, which means that when the surface is placed under vacuum three times 10 min each (for a total of 30 min), the pressure is 0.3 mbar at the end of each time interval, but when it is left for 30 min continuously, the pressure reaches a value of 0.049 mbar. Therefore, for the difference between leaving the surface continuously for 30 min or leaving it cumulatively for 30 min but for lower time intervals, the vacuum has a different value. The same applies to other times like 30, 60 min, etc. However, a memory effect exists, and, thus, an increase in the contact angle values is observed even when a surface is placed repeatedly at a certain pressure.

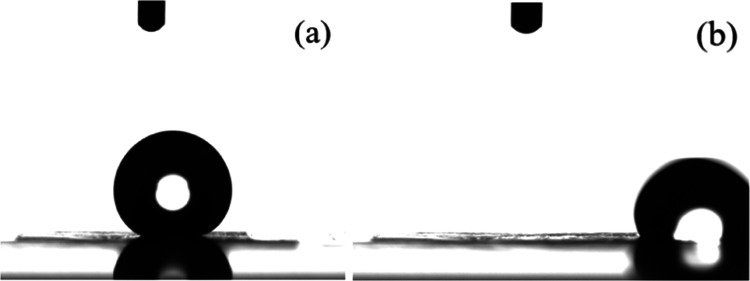

Residence of an irradiated Ti6Al4V surface in vacuum renders it superhydrophobic; it is important, however, as it has already been discussed, to investigate the behavior of the surface with respect to water adhesion, which determines its water repellency. Figure 10 shows representative water droplets on a Ti6Al4V surface that remained under vacuum for 24 h right after irradiation; Figure 10a shows the droplet as soon as it was deposited on the surface exhibiting an equilibrium contact angle of 149 ± 1° and after rotating the stage to monitor the angle at which the drop rolls off (Figure 10b). The surface exhibits a very weak water adhesion since the drop completely rolls off the surface at a sliding angle of ∼1.5°; therefore, this particular surface is superhydrophobic and water-repellent and it can be characterized as exhibiting the Lotus leaf effect. A video that illustrates the rolling off of a water droplet from an irradiated surface that has undergone a vacuum treatment for 24 h is shown in the Supporting Information as Video S2. It is reminded that, in the case of the surfaces that underwent heating after irradiation, where the contact angle was 149 ± 2°, as well, the surface was not water-repellent but exhibited high water adhesion with the droplet being adhered onto the surface even after rotation of the system by 90°. Therefore, both treatments of the surface following laser irradiation result in superhydrophobic behavior, however with different water adhesion characteristics. The effect of vacuum treatment on the superhydrophilic–superhydrophobic conversion was investigated in a few works in the past; however, in the majority of such studies, an ultrahigh vacuum O (1 × 10–4 Pa) was applied to influence the surface properties.75−78,81 In only one previous work, a moderate and easily accessible vacuum was applied to render copper surfaces hydrophobic; in that case, however, it took ∼8 days to achieve a water contact angle of 120°.70 Therefore, it is the first time, at least to our knowledge, that superhydrophobicity and water repellency are attained utilizing an easy, fast, and economic way achievable in every laboratory.

Figure 10.

Photographs of representative water droplets on a Ti6Al4V surface that remained in a vacuum oven under dynamic conditions for 24 h (a) as deposited onto the surface and (b) after a 1.5° rotation of the system.

Chemical Analysis

In general, it is the chemical composition of a flat surface that determines its hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity. The effects of the chemistry of the surface are further modified (usually enhanced) by the surface morphology, especially by the presence of hierarchical roughness.1,69,85,86 As far as metals and metal alloys are concerned, their surfaces are usually covered by films of the respective native oxides, which give them high surface energy and, thus, hydrophilic properties. However, the situation changes, as discussed above, when the surface is exposed to laser irradiation or other aggressive conditions that initiate adsorption, chemisorption, and chemical interactions of gases, vapors, or moisture present in ambient air. It is well known that hydrophilic surfaces with high surface energy are rich in polar functional groups in contrast to hydrophobic ones, which are rich in nonpolar groups. Therefore, assuming the same surface morphology, as the oxygen content on the surface increases, the surface hydrophilicity is expected to increase, while an increase in the carbon content, like, for example, by adsorption or chemisorption of nonpolar hydrocarbons present in air, leads to hydrophobic behavior. In the case of the present systems, it is the femtosecond laser irradiation of the surface that causes its morphological changes and no further modification in its structural characteristics or roughness can be imposed when it resides under ambient air, temperature, or vacuum. It is, thus, anticipated that the alteration of the surface wetting properties is completely due to changes in its chemical composition.

To quantify the changes in the chemical composition of the Ti6Al4V surfaces following the laser irradiation and the subsequent treatment in air, at a particular temperature and/or under vacuum, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopic (EDS) analysis was employed. Table 1 shows the results of the EDS analysis for all of the surfaces investigated. EDS results show that the C:O:Ti atomic ratio of a smooth Ti6Al4V surface is 4.8:4.1:81.9, and it remains almost unaffected when this surface stays under vacuum or heating. However, when the surface is irradiated, a significant increase in the amount of the surface oxygen is observed with the ratio C:O:Ti becoming 6.4:58.1:30.7, which justifies the superhydrophilicity measured by the contact angle measurements. This can be understood based on a passivation layer formed by water molecules (moisture) on the surface after the irradiation and on the presence of a large number of coordinatively unsaturated metal and oxygen atoms that promote the heterolytic dissociative adsorption of water molecules; this gives rise to a hydroxylated layer on the oxide surface, which in turn can adsorb a second water layer via hydrogen bonds.75,81 Fabrication of a superhydrophobic surface requires the reduction of its surface energy, which can be achieved via adsorption of organic molecules and/or the formation of a thin carbonaceous layer. Following the irradiation of the surface, its presence in air or under vacuum or at high temperature causes a significant increase in the amount of carbon in agreement with previous studies;72,75−77,81 this amount increases more and much faster in the two latter cases of vacuum treatment or heating. The increase in the amount of carbon even in ambient air is due to the adsorption or chemisorption of hydrocarbon molecules present in air, which may form carboxylates via, e.g., esterification onto the hydroxylated metal oxide surfaces that becomes significantly more effective under vacuum, due to the very low water vapor content inside the vacuum chamber since the passivation of reactive OH sites by hydrogen-bonded water molecules is avoided. The effect is also enhanced by heating because of the effect of temperature on the kinetics of adsorption but to a less significant degree.

Table 1. EDS Analysis of the Studied Surfaces (Expressed as Atom %)a.

| C | O | Ti | Al | V | hydrophobicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| smooth surface | 4.8 | 4.1 | 81.9 | 8.5 | 0.7 | hydrophilic |

| smooth surface in vacuum | 5.0 | 4.2 | 81.6 | 8.6 | 0.7 | hydrophilic |

| smooth surface at 120 °C for 24 h | 4.7 | 4.1 | 82.2 | 8.3 | 0.7 | hydrophilic |

| just irradiated surface | 6.4 | 58.1 | 30.7 | 4.1 | 0.7 | superhydrophilic |

| irradiated surface and 24 h in vacuum (oil-free pump) | 6.8 | 54.2 | 34.6 | 4.4 | 0.8 | superhydrophilic |

| irradiated surface and 5 days in air | 8.9 | 55.7 | 31.6 | 4.1 | 0.6 | hydrophilic |

| irradiated surface and 24 h heating at 120 °C | 14.9 | 47.6 | 32.2 | 4.7 | 0.6 | superhydrophobic |

| irradiated surface and 24 h in vacuum (oil pump) | 15.4 | 50.7 | 28.9 | 4.2 | 0.7 | superhydrophobic |

C: carbon; O: oxygen; Ti: titanium; Al: aluminum; V: vanadium.

Conclusions

The surface properties of a Ti6Al4V metal alloy were investigated following laser irradiation, and the effects of vacuum pressure, temperature, and environment on the wetting properties of the surface were evaluated. The initial smooth surface of the Ti6Al4V alloy can be characterized as hydrophilic since its contact angle is 60 ± 2°. By irradiating the surface with a femtosecond laser, a random roughness is fabricated, which, together with the surface polar groups introduced during irradiation, renders the surface superhydrophilic belonging to the Wenzel wetting regime. The wetting properties of the surface can be significantly altered by residing in ambient air, heating at various (low) temperatures, and under vacuum in a vacuum chamber; however, the kinetics of the modification is very different in the three cases. An irradiated surface, which remained under ambient conditions, becomes hydrophobic with a maximum contact angle of 129 ± 2°; however, the change takes a long time and it lasts for a finite time interval. When the surface is heated following irradiation, the higher the temperature at which the surface is heated, the greater the contact angle that can be achieved and the faster this value is attained; for temperatures equal to or higher than 120 °C, the surface can become hydrophobic in less than 24 h. On the other hand, there is a significant and not trivial dependence of the contact angle on the pressure of the vacuum chamber in which the surface resides. It is both the pressure and time that the surface remains at the specific vacuum that affect the behavior. The lower the pressure, the higher the hydrophobicity of the surface. When the surface resides for at least 3 h under dynamic vacuum conditions, its contact angle reaches a value of about 149 ± 1°.

It is shown that these mild post-irradiation treatments do not modify the characteristics of the micro/nano-structured morphology of the metallic surfaces that is developed by the laser processing; it is only its chemical composition that is modified by the exposure to the different environments, which results in a modification of the wetting behavior. For the irradiated surfaces staying in air or undergoing temperature or vacuum treatments, the surface composition shows higher carbon contents due to the adsorption of hydrocarbons from the environment rendering the surfaces hydrophobic. This, together with the existing micro/nano-structuring of the surfaces, makes them superhydrophobic. It is not clear, however, whether those surfaces can be considered belonging to the Wenzel or to the Cassie–Baxter regime.

Although both temperature and pressure lead to surfaces with similar hydrophobicity, i.e., in both cases, the maximum measured contact angle was the same, there is a significant difference concerning their water-repellent properties; surfaces that remained under vacuum were superhydrophobic and water-repellent (very low contact angle hysteresis), whereas the ones that had gone through thermal processing were superhydrophobic with high water adhesion (a water drop did not roll off even when the surface was tilted by 90°).

Therefore, temperature and vacuum can provide facile, economic, and eco-friendly ways to fabricate superhydrophobic surfaces with low or high water adhesion to be utilized in different applications that preclude the use of organic coatings for surface modification.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by FEMTOSURF, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement no. 825512. The authors acknowledge the help of Stefanos Papadakis with the SEM and EDS measurements. They also thank UAB FEMTIKA, Lithuania, for providing the Ti6Al4V metal alloy surfaces.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.langmuir.1c03431.

Video illustrating that water droplet cannot roll off a superhydrophobic Ti6Al4V surface that has been developed after laser irradiation and staying at 120 °C for 24 h even after inclination of the surface by 90° (Video S1) (AVI)

Video illustrating that a water droplet rolls off a superhydrophobic Ti6Al4V surface that has been developed after laser irradiation and staying in dynamic vacuum conditions for 24 h after inclination of the surface by 1.5° (Video S2) (AVI)

SEM images at different magnifications and under surface tilting for a metallic surface that was heated at 120 °C for 24 h or that remained under dynamic vacuum for 24 h; wetting behavior and SEM images of a smooth surface after moderate vacuum or temperature treatment (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anastasiadis S. H. Development of Functional Polymer Surfaces with Controlled Wettability. Langmuir 2013, 29, 9277–9290. 10.1021/la400533u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmanin T.; Guittard F. Recent Advances in the Potential Applications of Bioinspired Superhydrophobic Materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 16319–16359. 10.1039/C4TA02071E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. T.; Hunter S. R.; Aytug T. Superhydrophobic Materials and Coatings: A Review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 086501 10.1088/0034-4885/78/8/086501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarratt L. R. J.; Steiner U.; Neto C. A review on the mechanical and thermodynamic robustness of superhydrophobic surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 246, 133–152. 10.1016/j.cis.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinas K.; Dimitrakellis P.; Sarkiris P.; Gogolides E. A Review of Fabrication Methods, Properties and Applications of Superhydrophobic Metals. Processes 2021, 9, 666 10.3390/pr9040666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barberoglou M.; Zorba V.; Stratakis E.; Spanakis E.; Tzanetakis P.; Anastasiadis S. H.; Fotakis C. Bio-Inspired Water Repellent Surfaces Produced by Ultrafast Laser Structuring of Silicon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 5425–5429. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.07.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B.; Jung Y. C.; Koch K. Self-Cleaning Efficiency of Artificial Superhydrophobic Surfaces. Langmuir 2009, 25, 3240–3248. 10.1021/la803860d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Y.; Liu Y.; Xu Q. F.; Barahman M.; Lyons A. M. Catalytic, Self-Cleaning Surface with Stable Superhydrophobic Properties: Printed Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Arrays Embedded with TiO2 Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2632–2640. 10.1021/am5076315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. Y.; Zhao X. J.; Wang W. F.; Gong X. Durable Self-Cleaning Surfaces with Superhydrophobic and Highly Oleophobic Properties. Langmuir 2019, 35, 8404–8412. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Liu K.; Yao X.; Jiang L. Bioinspired Surfaces with Superwettability: New Insight on Theory, Design, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8230–8293. 10.1021/cr400083y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomga J.; Varshney P.; Nanda D.; Satapathy M.; Mohapatra S. S.; Kumar A. Fabrication of durable and regenerable superhydrophobic coatings with excellent self-cleaning and anti-fogging properties for aluminium surfaces. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 702, 161–170. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.01.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L.; Jones A. K.; Sikka V. K.; Wu J.; Gao D. Anti-Icing Superhydrophobic Coatings. Langmuir 2009, 25, 12444–12448. 10.1021/la902882b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreder M. J.; Alvarenga J.; Kim P.; Aizenberg J. Design of anti-icing surfaces: smooth, textured or slippery?. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 15003 10.1038/natrevmats.2015.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nurioglu A. G.; Esteves A. C. C.; With G. de Non-toxic, non-biocide-release antifouling coatings based on molecular structure design for marine applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 6547–6570. 10.1039/C5TB00232J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta D. V.; Dunn A.; Wasley T. J.; Kay R. W.; Stringer J.; Smith P. J.; Connaughton C.; Shephard J. D. Nanosecond Laser Textured Superhydrophobic Metallic Surfaces and Their Chemical Sensing Applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 357, 248–254. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. Y.; Lai S. N.; Yen C. C.; Jiang X. F.; Peroulis D.; Stanciu L. A. Surface functionalization of Ti3C2TX MXene with highly reliable superhydrophobic protection for volatile organic compounds sensing. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 11490–11501. 10.1021/acsnano.0c03896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira N. M.; Neto A. I.; Song W.; Mano J. F. Two-Dimensional Open Microfluidic Devices by Tuning the Wettability on Patterned Superhydrophobic Polymeric Surface. Appl. Phys. Express 2010, 3, 085205 10.1143/APEX.3.085205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Draper M. C.; Crick C. R.; Orlickaite V.; Turek V. A.; Parkin I. P.; Edel J. B. Superhydrophobic Surfaces as an on-Chip Microfluidic Toolkit for Total Droplet Control. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 5405–5410. 10.1021/ac303786s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradisanos I.; Fotakis C.; Anastasiadis S. H.; Stratakis E. Gradient Induced Liquid Motion on Laser Structured Black Si Surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 111603 10.1063/1.4930959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yohe S. T.; Colson Y. L.; Grinstaff M. W. Superhydrophobic Materials for Tunable Drug Release: Using Displacement of Air to Control Delivery Rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2016–2019. 10.1021/ja211148a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A. C.; Mano J. F. Micro/nano-structured superhydrophobic surfaces in the biomedical field: part II: applications overview. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 271–297. 10.2217/nnm.14.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D. W.; Wei H.; Gauthier A. C.; Song J.; Jin Y.; Xiao H. Superhydrophobic modification of cellulose and cotton textiles: Methodologies and applications. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2020, 5, 1–15. 10.1016/j.jobab.2020.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han X.; Gong X. In Situ, One-Pot Method to Prepare Robust Superamphiphobic Cotton Fabrics for High Buoyancy and Good Antifouling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 31298–31309. 10.1021/acsami.1c08844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan F.; Song Z.; Xin F.; Wang H.; Yu D.; Li G.; Liu W. Preparation of hydrophobic transparent paper via using polydimethylsiloxane as transparent agent. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2020, 5, 37–43. 10.1016/j.jobab.2020.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Wu M.; Duan G.; Gong X. One-step fabrication of eco-friendly superhydrophobic fabrics for high-efficiency oil/water separation and oil spill cleanup. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 1296–1309. 10.1039/D1NR07111D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzer J.; Efimenko K. Recent Developments in Superhydrophobic Surfaces and Their Relevance to Marine Fouling: A Review. Biofouling 2006, 22, 339–360. 10.1080/08927010600980223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorba V.; Stratakis E.; Barberoglou M.; Spanakis E.; Tzanetakis P.; Anastasiadis S. H.; Fotakis C. Biomimetic Artificial Surfaces Quantitatively Reproduce the Water Repellency of a Lotus Leaf. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4049–4054. 10.1002/adma.200800651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliffe N. J.; McHale G.; Atherton S.; Newton M. I. An introduction to superhydrophobicity. Adv. Colloid Interface 2010, 161, 124–138. 10.1016/j.cis.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratakis E.; Mateescu A.; Barberoglou M.; Vamvakaki M.; Fotakis C.; Anastasiadis S. H. From Superhydrophobicity and Water Repellency to Superhydrophilicity: Smart Polymer-Functionalized Surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4136–4138. 10.1039/c003294h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frysali M. A.; Papoutsakis L.; Kenanakis G.; Anastasiadis S. H. Functional Surfaces with Photocatalytic Behavior and Reversible Wettability: ZnO Coating on Silicon Spikes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 25401–25407. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frysali M. A.; Anastasiadis S. H. Temperature- and/or pH-Responsive Surfaces with Controllable Wettability: From Parahydrophobicity to Superhydrophilicity. Langmuir 2017, 33, 9106–9114. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B.; Jung Y. C.; Koch K. Micro-, Nano- and Hierarchical Structures for Superhydrophobicity, Self-Cleaning and Low Adhesion. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2009, 367, 1631–1672. 10.1098/rsta.2009.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood M. K.; Zheng H.; Liew T. H.; Leong K. C.; Foo Y. L.; Rajagopalan R.; Khan S. A.; Choi W. K. Mimicking both petal and lotus effects on a single silicon substrate by tuning the wettability of nanostructured surfaces. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4126–4133. 10.1021/la1050783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R. D.; Vedhanarayanan B.; Ajayaghosh A. Creation of “Rose Petal” and “Lotus Leaf” Effects on Alumina by Surface Functionalization and Metal-Ion Coordination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16018–16022. 10.1002/anie.201709463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nine M. J.; Tung T. T.; Alotaibi F.; Tran D. N. H.; Losic D. Facile Adhesion-Tuning of Superhydrophobic Surfaces between “Lotus” and “Petal” Effect and their Influence on Icing and Deicing Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8393–8402. 10.1021/acsami.6b16444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthlott W.; Neinhuis C. Purity of the Sacred Lotus, or Escape from Contamination in Biological Surfaces. Planta 1997, 202, 1–8. 10.1007/s004250050096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.; Li S. H.; Li Y. S.; Li H. J.; Zhang L. J.; Zhai J.; Song Y. L.; Liu B. Q.; Jiang L.; Zhu D. B. Super-hydrophobic surfaces: from natural to artificial. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 1857–1860. 10.1002/adma.200290020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X.; Jiang L. Biophysics: water-repellent legs of water striders. Nature 2004, 432, 36. 10.1038/432036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. S.; Jiang L. Bio-inspired design of multiscale structures for function integration. Nano Today 2011, 6, 155–175. 10.1016/j.nantod.2011.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique R. H.; Gomard G.; Hölscher H. The role of random nanostructures for the omnidirectional anti-reflection properties of the glasswing butterfly. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6909 10.1038/ncomms7909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R.; Nosonovsky M. Surface Micro/nanotopography, Wetting Properties and the Potential for Biomimetic Icephobicity of Skunk Cabbage Symplocarpus Foetidus. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 7797–7803. 10.1039/C4SM01230E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu J. Y.; Kuo C. W.; Chen P. L.; Mou C. Y. Fabrication of tunable superhydrophobic surfaces by nanosphere lithography. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 561–564. 10.1021/cm034696h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix L. M.; Lejeune M.; Ceriotti L.; Kormunda M.; Meziani T.; Colpo P.; Rossi F. Tuneable rough surfaces: A new approach for elaboration of superhydrophobic films. Surf. Sci. 2005, 592, 182–188. 10.1016/j.susc.2005.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Y.; Dai S. X.; John J.; Carter K. R. Superhydrophobic surfaces from hierarchically structured wrinkled polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11066–11073. 10.1021/am403209r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. J.; Cao J.; Jia J. S.; Qi J. L.; Huang Y. X.; Feng J. C. Making superhydrophobic surfaces with microstripe array structure by diffusion bonding and their applications in magnetic control microdroplet release systems. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1700918 10.1002/admi.201700918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H. X.; Huang S.; Liu J. Y.; Chen F. Z.; Yang X. L.; Xu W. J.; Liu X. Wettability gradient surface fabricated by combining electrochemical etching and lithography. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2017, 38, 979–984. 10.1080/01932691.2016.1216441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drzymala J. Hydrophobicity and collectorless flotation of inorganic materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1994, 50, 143–185. 10.1016/0001-8686(94)80029-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjursten L. M.; Rasmusson L.; Oh S.; Smith G. C.; Brammer K. S.; Jin S. Titanium dioxide nanotubes enhance bone bonding in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 2010, 92, 1218–1224. 10.1002/jbm.a.32463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K.; Chen Y.; Du Z. W.; Niu F. L. Surface integrity of titanium part by ultrasonic magnetic abrasive finishing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 80, 997–1005. 10.1007/s00170-015-7028-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutjering G.; Williams J. C.. Titanium; Springer: Germany, 2003; p 177. [Google Scholar]

- Sani A.; Salihu Y. I.; Suleiman A. I.; Eyinavi A. I. Classification, Properties and Applications of titanium and its alloys used in automotive industry- A Review. Am. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K.; Zhang G.; Ma G.; Wu D.; et al. Titanium and Titanium Alloys. J. Manuf. Processes 2020, 56, 616–622. 10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.; Zhou F.; Hao J.; Liu W. Stable biomimetic super-hydrophobic engineering materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15670–15671. 10.1021/ja0547836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmi R.; Basu B. J. Fabrication of superhydrophobic sol–gel composite films using hydrophobically modified colloidal zinc hydroxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 339, 454–460. 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Guo Y.; Zhang P.; Wu Z.; Zhang Z. Superhydrophobic CuO@Cu2S nanoplate vertical arrays on copper surfaces. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 1200–1203. 10.1016/j.matlet.2010.02.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Sarkar D. K.; Grant Chen X. Superhydrophobic aluminum alloy surfaces prepared by chemical etching process and their corrosion resistance properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 1012–1024. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.08.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney P.; Mohapatra S. S.; Kumar A. Superhydrophobic coatings for aluminium surfaces synthesized by chemical etching process. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2016, 7, 248–264. 10.1080/19475411.2016.1272502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Li S.; Wang Y.; Wang H.; Gao K.; Han Z.; Ren L. Superhydrophobic and superoleophobic surface by electrodeposition on magnesium alloy substrate: wettability and corrosion inhibition. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 478, 164–171. 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremaldi J.; Bhushan B. Fabrication of bioinspired, self-cleaning superliquiphilic/phobic stainless steel using different pathways. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 518, 284–297. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. P.; Rashid M. R.; Khew S. Y.; Li F. P.; Hong M. H. Wettability transition of laser textured brass surfaces inside different mediums. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 369–375. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. T.; Wang H.; Satoh G.; Yao Y. L. Applications of Surface Structuring with Lasers. J. Laser Appl. 2011, 1095–1104. 10.2351/1.5062186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Chi Z.; Cao L.; Weng Z.; Wang L.; Li L.; Saeed S.; Lian Z.; Wang Z. Fabrication of biomimetic superhydrophobic and anti-icing Ti6Al4V alloy surfaces by direct laser interference lithography and hydrothermal treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 534, 147576 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Calderon M.; Rodriguez A.; Ponte A. D.; Minana M. C. M.; Aranzadi M. G.; Olaizola S. M. Femtosecond laser fabrication of highly hydrophobic stainless steel surface with hierarchical structures fabricated by combining ordered microstructures and LIPSS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 374, 81–89. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.09.261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo C. V.; Chun D. M. Fast wettability transition from hydrophilic to superhydrophobic laser-textured stainless steel surfaces under low-temperature annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 409, 232–240. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allahyari E.; Nivas J. J. J.; Oscurato S. L.; Salvatore M.; Ausanio G.; Vecchione A.; Fittipaldi R.; Maddalena P.; Bruzzesea R.; Amorusoa S. Laser surface texturing of copper and variation of the wetting response with the laser pulse fluence. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 470, 817–824. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.11.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Song J.; Sun J.; Lu Y.; Yu Z. Rapid fabrication of large-area, corrosion resistant superhydrophobic Mg alloy surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4404–4414. 10.1021/am2010527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Wang C.; Dong X.; Yin K.; Zhang F.; Xie Z.; Chu D.; Duan J. Controllable superhydrophobic aluminum surfaces with tunable adhesion fabricated by femtosecond laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 102, 25–31. 10.1016/j.optlastec.2017.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Žemaitis A.; Mimidis A.; Papadopoulos A.; Gecys P.; Raciukaitis G.; Stratakis E.; Gedvilas M. Controlling the wettability of stainless steel from highly-hydrophilic to super-hydrophobic by femtosecond laser-induced ripples and nanospikes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37956–37961. 10.1039/D0RA05665K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzig A.-M.; Hatzikiriakos S. G.; Englezos P. Patterned Superhydrophobic Surfaces. Langmuir 2009, 25, 4821–4827. 10.1021/la8037582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizi-bandoki P.; Valette S.; Audouard E.; Benayoun S. Time dependency of the hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity of metallic alloys subjected to femtosecond laser irradiations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 273, 399–407. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.02.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.; Zhong M.; Fan P.; Gong D.; Zhang H. Wettability conversion of ultrafast laser structured copper surface. J. Laser Appl. 2015, 27, S29107 10.2351/1.4906477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long J.; Zhong M.; Zhang H.; Fan P. Superhydrophilicity to superhydrophobicity transition of picosecond laser microstructured aluminum in ambient air. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 441, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Mei X.; Tian Y.; Zhang Da.; Li Y.; Liu X. Modification of wettability property of titanium by laser texturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 87, 1663–1670. 10.1007/s00170-016-8601-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Z.; Xu J.; Yu Z.; Yu H.; et al. A simple two-step approach for the fabrication of bio-inspired superhydrophobic and anisotropic wetting surfaces having corrosion resistance. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 793, 326–335. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.04.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagdheesh R.; Diaz M.; Marimuthu S.; Ocana J. Robust fabrication of μ-patterns with tunable and durable wetting properties: hydrophilic to ultrahydrophobic via a vacuum process. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 7125–7136. 10.1039/C7TA01385J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagdheesh R.; Diaz M.; Marimuthu S.; Ocana J. L. Hybrid laser and vacuum process for rapid ultrahydrophobic Ti-6Al-4V surface formation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 471, 759–766. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschwitz P.; Jagdheesh R.; Rostohar D.; Brajer J.; Kopeĉek J.; Jiřícek P.; Houdková J.; Mocek T. Hydrophilic to ultrahydrophobic transition of Al 7075 by affordable ns fiber laser and vacuum processing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144523 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D.; Sauer M.; Kroechert Ching K.; Kalss G.; dos Santos A. C. V. D.; Ramer G.; Foelske A.; Lendl B.; Liedl G.; Otto A. Wettability transition of femtosecond laser patterned nodular cast iron (NCI) substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 559, 149897 10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bongiovanni R.; Malucelli G.; Sangermano M.; Priola A. Properties of UV-curable coatings containing fluorinated acrylic structures. Prog. Org. Coat. 1999, 36, 70–78. 10.1016/S0300-9440(99)00033-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L.; Wang Y.; Ding J.; Wang Q.; Chen Q. Water condensation on superhydrophobic aluminum surfaces with different low-surface-energy coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 4063–4068. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.12.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagdheesh R.; Hauschwitz P.; Mužik J.; Brajer J.; Rostohar D.; Jiřícek P.; Kopeĉek J.; Mocek T. Non-fluorinated superhydrophobic Al7075 aerospace alloy by ps laser Processing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 493, 287–293. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chun D.-M.; Ngo C.-V.; Lee K.-M. Fast fabrication of superhydrophobic metallic surface using nanosecond laser texturing and low-temperature annealing. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 65, 519–522. 10.1016/j.cirp.2016.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manousidaki M.; Papazoglou D. G.; Farsari M.; Tzortzakis S. 3D holographic light shaping for advanced multiphoton polymerization. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 85–88. 10.1364/OL.45.000085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambonneau M.; Li Q.; Fedorov V. Y.; Blothe M.; Schaarschmidt K.; Lorenz M.; Tzortzakis S.; Nolte S. Taming Ultrafast Laser Filaments for Optimized Semiconductor–Metal Welding. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2000433 10.1002/lpor.202000433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso J. T.; Garcia-Girón A.; Romano J. M.; Huerta-Murillo D.; Jagdheesh R.; Walker M.; Dimov S. S.; Ocaña J. L. Influence of ambient conditions on the evolution of wettability properties of an IR-, ns-laser textured aluminium alloy. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 39617–39627. 10.1039/C7RA07421B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Liu X.; Tian Y. Insights into the wettability transition of nanosecond laser ablated surface under ambient air exposure. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 533, 268–277. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.