Abstract

CRISPR-Cas systems acquire heritable defense memory against invading nucleic acids through adaptation. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems have unique and intriguing features of defense and are important in method development for Genetics research. We started to understand the common and unique properties of type III CRISPR-Cas adaptation in recent years. This review summarizes our knowledge regarding CRISPR-Cas adaptation with the emphasis on type III systems and discusses open questions for type III adaptation studies.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas system, type III, adaptation, ssDNA secondary structure, reverse transcriptase

Introduction

Prokaryotic cells evolved multiple strategies to defend against viruses and non-beneficial plasmids, including abortive infection, restriction–modification systems (Sturino and Klaenhammer, 2006; Rocha and Bikard, 2022), and recently discovered CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)-Cas (CRISPR-associated gene) systems (Makarova et al., 2011, 2020b; Hille et al., 2018; Nussenzweig and Marraffini, 2020). The sequence-specific and adaptive defense activity of a CRISPR-Cas system is acquired by adaptation, during which a short fragment (protospacer) of the foreign DNA is captured and integrated into the CRISPR locus at the leader proximal end as a spacer, simultaneously with a duplication of the first repeat (Barrangou et al., 2007; Bhaya et al., 2011; Arslan et al., 2014; Heler et al., 2014). A spacer in a CRISPR array encodes a small CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which guides an interference protein or a protein complex (crRNP) to destroy the previously encountered foreign nucleic acids (Barrangou et al., 2007; Pougach et al., 2010; Sorek et al., 2013). CRISPR-Cas systems are structurally and functionally diverse, and are classified into six types (type I-VI) and multiple subtypes (Haft et al., 2005; Makarova et al., 2006, 2011, 2015; Kunin et al., 2007; Shmakov et al., 2015).

Functional studies of CRISPR-Cas systems, especially those regarding target interference, have inspired researchers to develop many unprecedented, convenient, and powerful tools for genome editing, gene expression control, disease detection and cures, and many other purposes (Pickar-Oliver and Gersbach, 2019). Adaptation abilities of CRISPR-Cas systems and the dynamic CRISPR arrays they generated have been used for bacterial strain typing (Barrangou and Dudley, 2016), bacterial virome detection (Choi and Lee, 2016), and even digital movie encoding and data storage (Shipman et al., 2017). The tremendous contribution of CRISPR-Cas systems to biotechnology makes their fundamental studies invaluable, especially those investigating adaptation, since it is the least understood process of CRISPR-Cas functions. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems have distinct features during target interference (Liu et al., 2018; Molina et al., 2020), and have been repurposed for prokaryotic genome editing, gene regulation, and transcription recording, to which the other CRISPR-Cas systems may not be functional (Zebec et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2018).

While type I, type II, and type V systems target DNAs (Barrangou et al., 2007; Brouns et al., 2008; Mulepati and Bailey, 2013; Anders et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2015; Redding et al., 2015), and type VI systems target single-stranded RNAs (ssRNAs; East-Seletsky et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017b,c; Shmakov et al., 2017), type III systems have been shown to have both DNA and RNA cleavage abilities both in vivo and in vitro (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; Hale et al., 2009; Staals et al., 2014; Tamulaitis et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2015; Elmore et al., 2016; Ichikawa et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017a; Tamulaitis et al., 2017). DNA target interference by type III systems requires the directional transcription of the target, as the DNase activity of the crRNPs is stimulated by base pairing between the guiding crRNAs and the transcript of the target DNAs (Deng et al., 2013; Goldberg et al., 2014; Samai et al., 2015; Elmore et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017a). Additionally, the Palm domain of Cas10 synthesizes cyclic oligoadenylates (cAns) as secondary messengers, which bind to CARF domain of Csx1 and activates the RNase activity of HEPN domain of Csx1 to non-specifically cleave the foreign DNA transcripts, and probably host transcripts as well (Kazlauskiene et al., 2017; Niewoehner et al., 2017; Foster et al., 2019). While PAM recognition is required for authentication of the interference process of type I and type II systems (Deveau et al., 2008; Mojica et al., 2009; Sternberg et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2015), target interference by type III systems tolerates a broad range of protospacer flanking sequences (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Elmore et al., 2016; Pyenson et al., 2017).

We accumulated breakthrough findings regarding adaptation of type III CRISPR-Cas systems in recent years. Here, We summarized our knowledge regarding CRISPR-Cas adaptation with the emphasis on type III systems, and discussed open questions for type III adaptation studies.

Adaptation by Type I and Type II CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR-Cas adaptation procedure includes protospacer selection, processing, and integration (Heler et al., 2014; Nussenzweig and Marraffini, 2020).

Integration by Cas1–Cas2 Complex

A CRISPR array usually associates with cas genes, and each Cas protein participates in one or more major steps of the CRISPR-Cas system-mediated defense (Bhaya et al., 2011; Makarova et al., 2011). Cas1 and Cas2 proteins form a hexamer (four Cas1 monomers centered by two Cas2 monomers) both in vivo and in vitro (Nunez et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2017; Wan et al., 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2019), which is essential for adaptation of all tested CRISPR-Cas systems (Barrangou et al., 2007; Yosef et al., 2012; Nunez et al., 2014; Heler et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015b; Fagerlund et al., 2017). Through the aid of this complex, the 3’-OH groups of the two strands of the prespacer (processed protospacer for integration) successively attack the junctions between the leader and the first repeat, and between the first repeat and the first pre-existing spacer (Nunez et al., 2015b; Rollie et al., 2015). By transesterification reactions, Cas1–Cas2 complex integrates the double-stranded prespacer into the CRISPR array, splitting the plus and the minus strand of the first repeat, and leaving two gaps (Nunez et al., 2015b; Rollie et al., 2015). DNA polymerase(s) and ligase(s) are thought to be required to fill the gap and finish the whole process. Since DNA polymerase I has been shown required for the type I adaptation in Escherichia coli (Ivancic-Bace et al., 2015), it is proposed to be the polymerase that fills the integration gap.

For several type I CRISPR-Cas systems, for example, the type I-E system in E. coli K12, Cas1 and Cas2 are the only two Cas proteins required for adaptation (Datsenko et al., 2012; Yosef et al., 2012; Diez-Villasenor et al., 2013; Nunez et al., 2014), while most type I systems and all studied type II systems require other Cas proteins for protospacer recognition or processing (Barrangou et al., 2007; Heler et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015b; Liu et al., 2017d; Kieper et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018, 2019; Shiimori et al., 2018; Almendros et al., 2019). Besides Cas proteins, the leader sequence and at least one repeat unit (Yosef et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015a; Grainy et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019), and integration host factor (IHF) and some other elements are also required to ensure the integration to happen at the correct position (Nunez et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Fagerlund et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2017; Yoganand et al., 2017; Rollie et al., 2018).

The Recognition, Selection, and Processing of the Proper Protospacers

For well-studied type I and type II CRISPR-Cas systems, the protospacers are selected along foreign DNAs by system-specific protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs; Deveau et al., 2008; Mojica et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). PAM recognition is also required for the authentication of the interference process (Deveau et al., 2008; Mojica et al., 2009; Sternberg et al., 2014; Redding et al., 2015), by which the crRNP complexes of type I and type II systems can protect the CRISPR loci (containing the same sequence as the target) within its own genome from interference. The Cas1–Cas2 complex of the type I-E system in E. coli K12 is sufficient to recognize the ATG PAM upstream of protospacers (Datsenko et al., 2012; Yosef et al., 2012; Diez-Villasenor et al., 2013; Nunez et al., 2014); while some other type I systems require Cas4 to recognize PAM sequences (Kieper et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018; Shiimori et al., 2018). Cas4 is a RecB-like nuclease (Zhang et al., 2012; Lemak et al., 2014), and has been shown to recognize PAM and determine the length and the orientation of the new spacers for some of the type I CRISPR-Cas systems (Kieper et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018, 2019; Shiimori et al., 2018; Almendros et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). The Cas9 protein of the type II system of Streptococcus pyogenes contains a PAM binding motif and performs PAM recognition to select the proper protospacers (Heler et al., 2015).

RecBCD complexes and their homologous protein complexes in prokaryotic cells bind to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) breaks, and repair the broken DNAs by degradation and homologous recombination (Dillingham and Kowalczykowski, 2008). RecBCD complexes have been shown to be required for adaptation of some tested type I systems (Ivancic-Bace et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2015; Radovcic et al., 2018). Since dsDNA breaks frequently happen during DNA replication, extensively replicating invaders and the plasmids with high copy numbers become more sensitive than the cellular genome to adaptation (Ivancic-Bace et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2015). Moreover, RecBCD can be hampered by chi sequences (Dillingham and Kowalczykowski, 2008), and the enrichment of the chi sites around the replication termini of the prokaryotic genomes helps the adaptation machineries to more specifically recognize foreign DNAs (Ivancic-Bace et al., 2015; Levy et al., 2015).

The processing of the protospacers from the long substrates to the short and mature prespacers is a prerequisite of adaptation, but it is the least understood step of the adaptation process. The existence of 3′-single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails of the prespacers substantially facilitate adaptation (Arslan et al., 2014; Nunez et al., 2015a,b; Rollie et al., 2015, 2018; Van Orden et al., 2020). Cas1 is a non-specific exonuclease in vitro when associated with Cas2 in the adaptation complex (Wiedenheft et al., 2009; Babu et al., 2011; He et al., 2018; Radovcic et al., 2018), and it trims 5′ ends of the protospacers, leaving 3’-ssDNA tails for the following integration (Wang et al., 2015; Fagerlund et al., 2017). In Streptococcus thermophilus, Cas2 of the type I-E system possesses a DnaQ-like 3′-5′ exonuclease domain, which has been proposed to process the 3′-overhangs of the prespacers to promote integration (Drabavicius et al., 2018). Some other non-Cas exonucleases, including DnaQ and ExoT, have also been shown to be involved in the 3’-ssDNA tail generation of the prespacers (Ramachandran et al., 2020).

Primed Adaptation

Target nucleic acids can escape from CRISPR-Cas-mediated interference by mutation(s) at pivotal positions within protospacers/targets or PAMs (Semenova et al., 2011; Westra et al., 2013). However, a pre-existing spacer in a CRISPR array, which is partially or totally complementary to a fragment of a molecule, can greatly stimulate adaptation against the same molecule (Datsenko et al., 2012; Swarts et al., 2012). To acquire new spacers from a molecule that the system has never processed before is termed “naïve adaptation,” whereas adaptation triggered by a pre-existing spacer (priming spacer) is termed “primed adaptation.” Primed adaptation is substantially more efficient than naïve adaptation (Fineran et al., 2014), and directs the adaptation machinery to the invader DNA instead of self-genome (Datsenko et al., 2012), thus providing the hosts with a co-evolutionary strategy to minimize the amount of CRISPR-Cas escapers. Primed adaptation has been studied and reported for many type I and two type II CRISPR-Cas systems, and interestingly, the secondarily adapted protospacers during primed adaptation were found to distribute around the cutting sites of crRNPs, with only one exception (type I-E system of E. coli K12; Datsenko et al., 2012; Swarts et al., 2012; Savitskaya et al., 2013; Fineran et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2014; Nussenzweig et al., 2019; Garrett et al., 2020; Wiegand et al., 2020; Hoikkala et al., 2021; Mosterd and Moineau, 2021). The mechanism(s) of primed adaptation are still under research and debate.

Adaptation by Type III CRISPR-Cas Systems

Many type III CRISPR-Cas systems, especially most type III-B systems, are not associated with cas1 or cas2 gene (Makarova et al., 2020a), so type III systems had been thought to be inert in adaptation for a long time. Instead, some type III systems appear to co-occur with type I systems and utilize crRNAs processed by the type I systems to provide additional defense against the invaders (Majumdar et al., 2015; Silas et al., 2017a). Until recent years, direct adaptation by type III systems has been observed and investigated.

Reverse Transcriptase-Mediated Type III CRISPR-Cas Adaptation

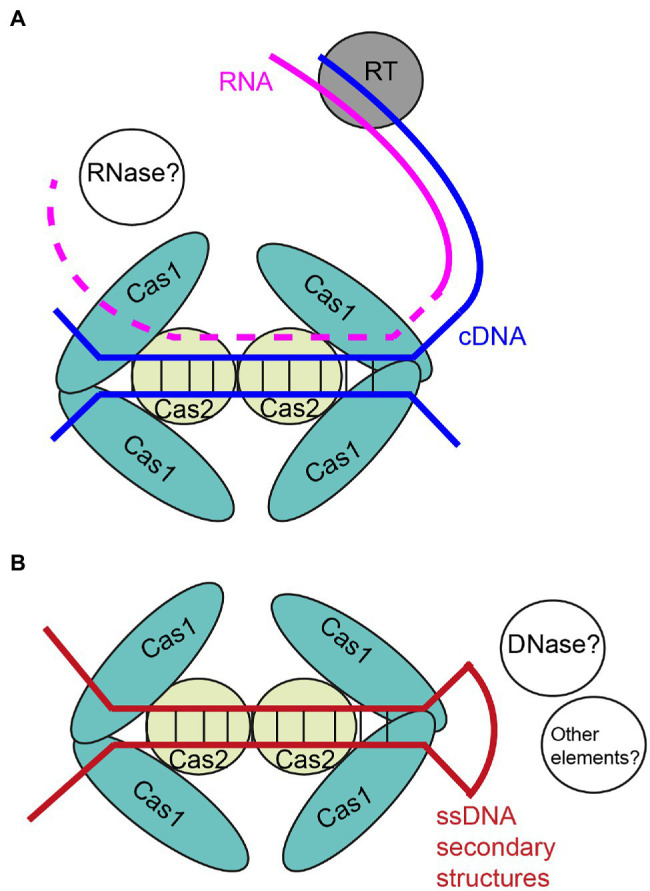

In 2016, Silas et al. (2016) reported adaptation by the type III-B system of Marinomonas mediterranea, revealing a novel reverse transcriptase (RT)-fused-Cas1 protein. While the reported RT-free systems can only adapt DNAs as CRISPR spacers, the type III-B system can use both RNAs and DNAs as substrates, and adaptation against RNAs is dependent on the RT (Figure 1A). This additional adaptation against RNAs makes the system preferentially acquire new spacers from highly transcribed regions versus weakly transcribed regions, which is beneficial for the function of the system, since target interference by type III systems requires transcription of the targets. Soon after this exciting finding, a similar RT-Cas1-Cas2 complex of Fusicatenibacter saccharivorans was used as a novel and efficient tool to record transcription event in E. coli (Schmidt et al., 2018). A similar RT-mediated type III adaptation against highly transcribed regions was reported by Gonzalez-Delgado et al. (2019), and moreover, they observed a dramatic preference against the coding strand of the rRNA genes. They speculated that the rRNA-encoding strand preference was also caused by RT and there was a correlation between gene transcription and new spacer orientation. However, since RT-active type III systems have no strand bias during adaptation against the other genes (Silas et al., 2016; Gonzalez-Delgado et al., 2019), it appears less likely that the bias was caused by transcription and RT activity. The findings by Zhang et al. (2021) and Aviram et al. (2022) indicate that the secondary structures formed by the coding strand of the rRNA genes (e.g., when the template strand is being processed by RNA polymerase) serve as additional and preferred substrates for CRISPR-Cas adaptation (see below).

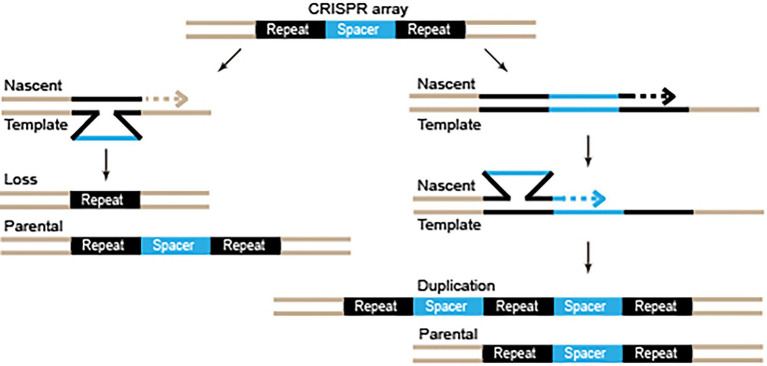

Figure 1.

Diagrams of unique type III adaptation preference with (A) and without (B) reverse transcriptase activity. (A) RT represents reverse transcriptase, which is usually fused with Cas1–Cas2 complex, and may also be independent as well. Complementary DNA (cDNA) is depicted by blue. RNA template is depicted by pink, and the dashed lines represents potential digestion against the RNA template. (B) Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) secondary structure is depicted by red. Hypothetical proteins or other elements are presented by white balls.

Type III CRISPR-Cas Adaptation Against Virulent Phages

The reported RT-encoding type III systems are not representative, because less than 10% of type III systems have RT activity (Silas et al., 2016). In 2020, Artamonova et al. (2020) observed and reported robust adaptation against a virulent phage, phiFa, by a RT-free type III system of Thermus thermophilus. The protospacers detected by high-throughput sequencing had a strand bias in that the template strands of the phage were adapted more extensively than the encoding strands, which was caused by counter-selection, since the crRNAs of the type III system needed to bind to the mRNAs of the phages to be functional. More interestingly, they found that the long terminal repeat (LTR), as the firstly invading part and early transcribed region of the phage, was adapted substantially more efficiently than the other parts of the phage, and the authors reasoned that maybe the LTR region encoded an anti-CRISPR element that blocked the functions of the CRISPR-Cas system. While not inconsistent with the data, it is more likely that the LTR formed secondary structures since it was a repeat-rich region, including palindromic, direct, and inverted repeats, and such structures could be recognized by type III CRISPR-Cas system (see below); or only adaptation against the early transcribed genes could perform timely defense against the phage. Soon after, Zhang et al. (2021) observed type III adaptation, followed by new crRNA-mediated defense, against virulent phage in S. thermophilus as well.

Common and Unique Properties of Type III CRISPR-Cas Adaptation

In 2021, Zhang et al. (2021) for the first time provided a detailed analysis of the properties of type III CRISPR-Cas adaptation in S. thermophilus. The authors compared the patterns of adaptation by the type III-A and a type II-A CRISPR-Cas systems of S. thermophilus against different rolling circle replicating (RCR) plasmids and theta-replicating plasmids, as well as host genome. A prominent and unique feature of the adaptation by the type III system was the apparent recognition of the single-strand origins (ssos) of the RCR plasmids, contrasting with that of the type II system. RCR plasmids produce ssDNA intermediates during their replication, and the long and partially palindromic ssos form stem-loop structures to trigger the synthesis of the minus strand (Khan, 1997; Del Solar et al., 1998; Khan, 2000; Ruiz-Maso et al., 2015). The authors reasoned that the ssDNA hairpins served as additional and preferred dsDNA substrates for adaptation of the type III system (Figure 1B). Similarly, the partially palindromic oriT sequence of pNT1 plasmid, and the stem-loop structures enriched regulatory regions of the genomic and plasmid genes, as well as the cloverleaf structures enriched rRNA and tRNA encoding regions of self-genome, were also enriched in type III adaptation but not in type II adaptation (Zhang et al., 2021). Most of natural plasmids of gram-positive bacteria and many of those of gram-negative bacteria are RCR plasmids (Khan, 1997). Moreover, the crucial structure of oriT and other DNA secondary structures are important for the conjugative transfer and other functions of environmental mobile genetic elements (Bikard et al., 2010). As a consequence, secondary structure recognition by the type III CRISPR-Cas system can be beneficial for the system to specifically and efficiently eliminate the invaders. In 2022, Aviram et al. (2022) systematically studied the adaptation by a RT-free type III system of Staphylococcus epidermidis (expressed in Staphylococcus aureus). They observed similar adaptation preference against rRNA and tRNA encoding regions in host genome by the type III system, but not by the type II system in the same host, further supporting the reality of the unique property of type III adaptation.

There is no known reverse transcriptase encoding sequence in S. thermophilus genome, and Zhang et al. (2021) did not observe direct correlation between type III adaptation and DNA transcription in S. thermophilus. However, the authors did observe slight preference of type III adaptation against highly transcribed regions of plasmids, and constant preference against riboswitch transcriptional attenuators. These riboswitches lie in the 5’ UTR of the regulated mRNAs, and interaction between a signaling molecule and a riboswitch controls formation of a transcriptional terminator hairpin (Henkin, 2008). Besides, a general enrichment of type III spacers was observed roughly at 10–50 bp downstream from start codons of genomic genes. Moreover, for all the regions mentioned here, type III spacers were specifically enriched at the encoding strand, which was displaced as ssDNA when the template strand was occupied by transcription machinery. These findings further indicate that DNA secondary structures formed by ssDNAs can serve as additional and preferred substrates for type III adaptation (Figure 1B). While the type III-A system of S. thermophilus has no direct or obvious correlation between the adaptation and DNA transcription level, in contrast, the frequency of adaptation by type III-A system of S. epidermidis was found to be directly and obviously correlated with DNA transcription level (Aviram et al., 2022), in a similar way with the RT-active type III systems (Silas et al., 2016; Gonzalez-Delgado et al., 2019). It is possible that there is an unknown and intrinsic mechanism of the S. epidermidis type III-A system to target highly transcribed region during adaptation. In contrast, it is also possible that S. aureus cells potentially express unknown reverse transcriptase, after all, many Staphylococcus species are proposed to have putative reverse transcriptase encoding sequences, for examples, see NCBI accession CAC8888864.1 and UniProtKB D2J8E1. For some RT-active type III systems, RT domain is fused with Cas6 which is not related to adaptation, instead of Cas1 or Cas2 (Silas et al., 2016), implicating that RT domains do not have to be in the adaptation complexes to influence adaptation pattern; in contrast, independent cellular RTs may be able to generate additional substrates for type III adaptation as well (Figure 1A).

Like many investigated type I and type II systems, adaptation by the type III-A system of S. epidermidis was facilitated by DNA free ends, which was enhanced by AddAB DNA repairing complex (homologous to RecBCD) and hampered by chi sites (Aviram et al., 2022), indicating that this is a common feature for all or most CRISPR-Cas systems. The lengths of all tested type III spacers fell into a roughly normal distribution, centered by 36 bp (Silas et al., 2016; Gonzalez-Delgado et al., 2019; Artamonova et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Aviram et al., 2022). Direct adaptation by all tested type III systems are PAM-independent (Silas et al., 2016; Gonzalez-Delgado et al., 2019; Artamonova et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Aviram et al., 2022), and requires only Cas1 and Cas2 proteins, but not Cas6 or any interference-related Cas proteins (Silas et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021; Aviram et al., 2022).

Intriguingly, although adaptation was inert after knocking out cas1 or cas2 genes, Zhang et al. (2021) observed the duplication of the repeat and the pre-existing spacer units, revealing an adaptation-independent repeat-spacer replication event. Such replication was observed in both the type III and the type II systems of S. thermophilus, indicating that it is a universal feature of all or many of the CRISPR-Cas systems (Zhang et al., 2021). DNA replication slippage in the repeat-rich region may help the CRISPR-Cas systems to replicate recently acquired spacers to enhance the expression of the crRNAs, as well as to lose the old spacers to keep a compact CRISPR array (Figure 2). While the analyses in the research by Zhang et al. (2021) were unable to detect spacer loss, such loss had been observed in a study regarding a type I CRISPR-Cas system (Rao et al., 2017).

Figure 2.

Diagram of repeat-spacer loss and duplication by DNA replication slippage. Repeats and spacers are depicted by black and blue. Dashed arrows indicate the DNA synthesis direction.

Conclusion and Open Questions

As a conclusion, different labs have independently detected adaptation against plasmids, phages, and host genomes by type III CRISPR-Cas system (Silas et al., 2016, 2017b; Schmidt et al., 2018; Gonzalez-Delgado et al., 2019; Artamonova et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021; Aviram et al., 2022). Interesting common and unique properties of type III adaptation have been identified. However, there are still interesting and important questions unanswered regarding type III adaptation. (1) We do not fully understand the detailed procedure or entire mechanism of RT-mediated type III adaptation. Does RT-mediated adaptation happen during or after the RT reaction? How do those adaptation modules process the DNAs after RT reaction? Is it necessary for the cells to digest the template RNA before CRISPR-Cas adaptation (Figure 1A)? These questions remain to be answered. (2) Whether type III Cas1–Cas2 complex has the intrinsic ability to recognize secondary structures, or other non-Cas elements are involved in this recognition, remains to be studied. (3) The mechanism of adaptation-independent dynamics of CRISPR arrays and the benefits of the process remain to be studied. (4) Whether primed adaptation activity exists in type III systems, and the mechanism of type III primed adaptation, remain to be studied. Target interference of type III systems tolerates a broad range of PAMs (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010; Elmore et al., 2016; Pyenson et al., 2017), and also tolerates apparently more mutations within the targets than type I and type II systems (Maniv et al., 2016; Pyenson et al., 2017). As a result, type III systems minimize the potential escapers of the invading nucleic acids (Maniv et al., 2016; Pyenson et al., 2017). Despite this difficulty of escape, primed adaptation may still be beneficial for type III CRISPR-Cas-mediated defense. As discussed above, naïve adaptation by the type III system preferentially uptakes the protospacers at the encoding strands of the promoter regions of expressed genes (Zhang et al., 2021). Since the target interference ability of the type III system requires a reverse complementary RNA, DNA uptake against the encoding strand will not directly contribute to defense. Moreover, as to the bona fide protospacers derived from the template strands, if the protospacer region was weakly transcribed or a late transcript in phage infection, the type III spacer-mediated defense may be insufficient to efficiently clear phage or plasmid nucleic acids (Goldberg et al., 2014; Rostol and Marraffini, 2019). In these situations, the potential primed adaptation triggered by the “inefficient” spacers may be able to provide a chance to the system to perform efficient secondary uptake to counter against the invaders.

Author Contributions

XZ revised and wrote this review. XA revised this review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the China National Key R&D Program during the 14th Five year Plan Period (2021YFD2200101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870652, 31570661).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dayong Zhou and Kun-lin Ho at The University of Georgia for helpful discussion.

References

- Almendros C., Nobrega F. L., Mckenzie R. E., Brouns S. J. J. (2019). Cas4-Cas1 fusions drive efficient PAM selection and control CRISPR adaptation. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 5223–5230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz217, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders C., Niewoehner O., Duerst A., Jinek M. (2014). Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 513, 569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature13579, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan Z., Hermanns V., Wurm R., Wagner R., Pul U. (2014). Detection and characterization of spacer integration intermediates in type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 7884–7893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku510, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artamonova D., Karneyeva K., Medvedeva S., Klimuk E., Kolesnik M., Yasinskaya A., et al. (2020). Spacer acquisition by type III CRISPR-Cas system during bacteriophage infection of Thermus thermophilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 9787–9803. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa685, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram N., Thornal A. N., Zeevi D., Marraffini L. A. (2022). Different modes of spacer acquisition by the Staphylococcus epidermidis type III-A CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1661–1672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1299, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu M., Beloglazova N., Flick R., Graham C., Skarina T., Nocek B., et al. (2011). A dual function of the CRISPR-Cas system in bacterial antivirus immunity and DNA repair. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 484–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07465.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Dudley E. G. (2016). CRISPR-based typing and next-generation tracking technologies. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 7, 395–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022814-015729, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Fremaux C., Deveau H., Richards M., Boyaval P., Moineau S., et al. (2007). CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D., Davison M., Barrangou R. (2011). CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 273–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132430, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikard D., Loot C., Baharoglu Z., Mazel D. (2010). Folded DNA in action: hairpin formation and biological functions in prokaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 570–588. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00026-10, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns S. J., Jore M. M., Lundgren M., Westra E. R., Slijkhuis R. J., Snijders A. P., et al. (2008). Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science 321, 960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. R., Lee S. Y. (2016). CRISPR technologies for bacterial systems: current achievements and future directions. Biotechnol. Adv. 34, 1180–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.08.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Pougach K., Tikhonov A., Wanner B. L., Severinov K., Semenova E. (2012). Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system. Nat. Commun. 3:945. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1937, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Solar G., Giraldo R., Ruiz-Echevarria M. J., Espinosa M., Diaz-Orejas R. (1998). Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 434–464. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.62.2.434-464.1998, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Garrett R. A., Shah S. A., Peng X., She Q. (2013). A novel interference mechanism by a type IIIB CRISPR-Cmr module in Sulfolobus. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 1088–1099. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12152, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H., Barrangou R., Garneau J. E., Labonte J., Fremaux C., Boyaval P., et al. (2008). Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1390–1400. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-07, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Villasenor C., Guzman N. M., Almendros C., Garcia-Martinez J., Mojica F. J. (2013). CRISPR-spacer integration reporter plasmids reveal distinct genuine acquisition specificities among CRISPR-Cas I-E variants of Escherichia coli. RNA Biol. 10, 792–802. doi: 10.4161/rna.24023, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillingham M. S., Kowalczykowski S. C. (2008). RecBCD enzyme and the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 642–671. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-08, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabavicius G., Sinkunas T., Silanskas A., Gasiunas G., Venclovas C., Siksnys V. (2018). DnaQ exonuclease-like domain of Cas2 promotes spacer integration in a type I-E CRISPR-Cas system. EMBO Rep. 19:e45543. doi: 10.15252/embr.201745543, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East-Seletsky A., O’Connell M. R., Knight S. C., Burstein D., Cate J. H., Tjian R., et al. (2016). Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature 538, 270–273. doi: 10.1038/nature19802, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore J. R., Sheppard N. F., Ramia N., Deighan T., Li H., Terns R. M., et al. (2016). Bipartite recognition of target RNAs activates DNA cleavage by the type III-B CRISPR-Cas system. Genes Dev. 30, 447–459. doi: 10.1101/gad.272153.115, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlund R. D., Wilkinson M. E., Klykov O., Barendregt A., Pearce F. G., Kieper S. N., et al. (2017). Spacer capture and integration by a type I-F Cas1-Cas2-3 CRISPR adaptation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E5122–E5128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618421114, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran P. C., Gerritzen M. J., Suarez-Diez M., Kunne T., Boekhorst J., Van Hijum S. A., et al. (2014). Degenerate target sites mediate rapid primed CRISPR adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E1629–E1638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400071111, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster K., Kalter J., Woodside W., Terns R. M., Terns M. P. (2019). The ribonuclease activity of Csm6 is required for anti-plasmid immunity by type III-A CRISPR-Cas systems. RNA Biol. 16, 449–460. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1493334, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett S., Shiimori M., Watts E. A., Clark L., Graveley B. R., Terns M. P. (2020). Primed CRISPR DNA uptake in Pyrococcus furiosus. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 6120–6135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa381, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G. W., Jiang W., Bikard D., Marraffini L. A. (2014). Conditional tolerance of temperate phages via transcription-dependent CRISPR-Cas targeting. Nature 514, 633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature13637, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Delgado A., Mestre M. R., Martinez-Abarca F., Toro N. (2019). Spacer acquisition from RNA mediated by a natural reverse transcriptase-Cas1 fusion protein associated with a type III-D CRISPR-Cas system in Vibrio vulnificus. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 10202–10211. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz746, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainy J., Garrett S., Graveley B. R., Terns M. P. (2019). CRISPR repeat sequences and relative spacing specify DNA integration by Pyrococcus furiosus Cas1 and Cas2. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 7518–7531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz548, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft D. H., Selengut J., Mongodin E. F., Nelson K. E. (2005). A guild of 45 CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein families and multiple CRISPR/Cas subtypes exist in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010060, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale C. R., Zhao P., Olson S., Duff M. O., Graveley B. R., Wells L., et al. (2009). RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex. Cell 139, 945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.040, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Wang M., Liu M., Huang L., Liu C., Zhang X., et al. (2018). Cas1 and Cas2 from the type II-C CRISPR-Cas system of Riemerella anatipestifer are required for spacer acquisition. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:195. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00195, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heler R., Marraffini L. A., Bikard D. (2014). Adapting to new threats: the generation of memory by CRISPR-Cas immune systems. Mol. Microbiol. 93, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12640, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heler R., Samai P., Modell J. W., Weiner C., Goldberg G. W., Bikard D., et al. (2015). Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Nature 519, 199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature14245, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkin T. M. (2008). Riboswitch RNAs: using RNA to sense cellular metabolism. Genes Dev. 22, 3383–3390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1747308, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille F., Richter H., Wong S. P., Bratovic M., Ressel S., Charpentier E. (2018). The biology of CRISPR-Cas: backward and forward. Cell 172, 1239–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.032, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoikkala V., Ravantti J., Diez-Villasenor C., Tiirola M., Conrad R. A., Mcbride M. J., et al. (2021). Cooperation between different CRISPR-Cas types enables adaptation in an RNA-targeting system. mBio 12, e03338–e03420. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03338-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H. T., Cooper J. C., Lo L., Potter J., Terns R. M., Terns M. P. (2017). Programmable type III-A CRISPR-Cas DNA targeting modules. PLoS One 12:e0176221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176221, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivancic-Bace I., Cass S. D., Wearne S. J., Bolt E. L. (2015). Different genome stability proteins underpin primed and naive adaptation in E. coli CRISPR-Cas immunity. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 10821–10830. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1213, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Samai P., Marraffini L. A. (2016). Degradation of phage transcripts by CRISPR-associated RNases enables type III CRISPR-Cas immunity. Cell 164, 710–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.053, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Zhou K., Ma L., Gressel S., Doudna J. A. (2015). Structural biology. A Cas9-guide RNA complex preorganized for target DNA recognition. Science 348, 1477–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1452, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskiene M., Kostiuk G., Venclovas C., Tamulaitis G., Siksnys V. (2017). A cyclic oligonucleotide signaling pathway in type III CRISPR-Cas systems. Science 357, 605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0100, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. A. (1997). Rolling-circle replication of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 442–455. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.442-455.1997, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. A. (2000). Plasmid rolling-circle replication: recent developments. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 477–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02001.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieper S. N., Almendros C., Behler J., Mckenzie R. E., Nobrega F. L., Haagsma A. C., et al. (2018). Cas4 facilitates PAM-compatible spacer selection during CRISPR adaptation. Cell Rep. 22, 3377–3384. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.103, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. G., Garrett S., Wei Y., Graveley B. R., Terns M. P. (2019). CRISPR DNA elements controlling site-specific spacer integration and proper repeat length by a type II CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 8632–8648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz677, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin V., Sorek R., Hugenholtz P. (2007). Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in CRISPR repeats. Genome Biol. 8:R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Dhingra Y., Sashital D. G. (2019). The Cas4-Cas1-Cas2 complex mediates precise prespacer processing during CRISPR adaptation. eLife 8:e44248. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44248, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Zhou Y., Taylor D. W., Sashital D. G. (2018). Cas4-dependent prespacer processing ensures high-Fidelity programming of CRISPR arrays. Mol. Cell 70, 48.e5–59.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemak S., Nocek B., Beloglazova N., Skarina T., Flick R., Brown G., et al. (2014). The CRISPR-associated Cas4 protein Pcal_0546 from Pyrobaculum calidifontis contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster: crystal structure and nuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 11144–11155. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku797, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A., Goren M. G., Yosef I., Auster O., Manor M., Amitai G., et al. (2015). CRISPR adaptation biases explain preference for acquisition of foreign DNA. Nature 520, 505–510. doi: 10.1038/nature14302, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Pan S., Zhang Y., Ren M., Feng M., Peng N., et al. (2016). Harnessing type I and type III CRISPR-Cas systems for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:e34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1044, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang R., Zhao D., Xiang H. (2014). Adaptation of the Haloarcula hispanica CRISPR-Cas system to a purified virus strictly requires a priming process. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 2483–2492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1154, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T. Y., Iavarone A. T., Doudna J. A. (2017a). RNA and DNA targeting by a reconstituted Thermus thermophilus type III-A CRISPR-Cas system. PLoS One 12:e0170552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li X., Ma J., Li Z., You L., Wang J., et al. (2017b). The molecular architecture for RNA-guided RNA cleavage by Cas13a. Cell 170, 714.e10–726.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li X., Wang J., Wang M., Chen P., Yin M., et al. (2017c). Two distant catalytic sites are responsible for C2c2 RNase activities. Cell 168, 121.e12–134.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Liu Z., Ye Q., Pan S., Wang X., Li Y., et al. (2017d). Coupling transcriptional activation of CRISPR-Cas system and DNA repair genes by Csa3a in Sulfolobus islandicus. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 8978–8992. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Pan S., Li Y., Peng N., She Q. (2018). Type III CRISPR-Cas system: introduction and its application for genetic manipulations. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 26, 1–14. doi: 10.21775/cimb.026.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S., Zhao P., Pfister N. T., Compton M., Olson S., Glover C. V., et al. (2015). Three CRISPR-Cas immune effector complexes coexist in Pyrococcus furiosus. RNA 21, 1147–1158. doi: 10.1261/rna.049130.114, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Grishin N. V., Shabalina S. A., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V. (2006). A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biol. Direct 1:7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Haft D. H., Barrangou R., Brouns S. J., Charpentier E., Horvath P., et al. (2011). Evolution and classification of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2577, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Timinskas A., Wolf Y. I., Gussow A. B., Siksnys V., Venclovas C., et al. (2020a). Evolutionary and functional classification of the CARF domain superfamily, key sensors in prokaryotic antivirus defense. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8828–8847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Alkhnbashi O. S., Costa F., Shah S. A., Saunders S. J., et al. (2015). An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 722–736. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Iranzo J., Shmakov S. A., Alkhnbashi O. S., Brouns S. J. J., et al. (2020b). Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 67–83. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniv I., Jiang W., Bikard D., Marraffini L. A. (2016). Impact of different target sequences on type III CRISPR-Cas immunity. J. Bacteriol. 198, 941–950. doi: 10.1128/JB.00897-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J. (2008). CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science 322, 1843–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.1165771, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini L. A., Sontheimer E. J. (2010). Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature 463, 568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature08703, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica F. J. M., Diez-Villasenor C., Garcia-Martinez J., Almendros C. (2009). Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 155, 733–740. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023960-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina R., Sofos N., Montoya G. (2020). Structural basis of CRISPR-Cas type III prokaryotic defence systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 65, 119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.06.010, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosterd C., Moineau S. (2021). Primed CRISPR-Cas adaptation and impaired phage adsorption in Streptococcus mutans. mSphere 6, e00185–e00221. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00185-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulepati S., Bailey S. (2013). In vitro reconstitution of an Escherichia coli RNA-guided immune system reveals unidirectional, ATP-dependent degradation of DNA target. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 22184–22192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472233, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner O., Garcia-Doval C., Rostol J. T., Berk C., Schwede F., Bigler L., et al. (2017). Type III CRISPR-Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers. Nature 548, 543–548. doi: 10.1038/nature23467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. K., Bai L., Harrington L. B., Hinder T. L., Doudna J. A. (2016). CRISPR immunological memory requires a host factor for specificity. Mol. Cell 62, 824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.027, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. K., Harrington L. B., Kranzusch P. J., Engelman A. N., Doudna J. A. (2015a). Foreign DNA capture during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nature 527, 535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature15760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. K., Kranzusch P. J., Noeske J., Wright A. V., Davies C. W., Doudna J. A. (2014). Cas1-Cas2 complex formation mediates spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 528–534. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2820, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez J. K., Lee A. S., Engelman A., Doudna J. A. (2015b). Integrase-mediated spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Nature 519, 193–198. doi: 10.1038/nature14237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenzweig P. M., Marraffini L. A. (2020). Molecular mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas immunity in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 54, 93–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-022120-112523, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussenzweig P. M., Mcginn J., Marraffini L. A. (2019). Cas9 cleavage of viral genomes primes the acquisition of new immunological memories. Cell Host Microbe 26, 515.e6–526.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.09.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W., Feng M., Feng X., Liang Y. X., She Q. (2015). An archaeal CRISPR type III-B system exhibiting distinctive RNA targeting features and mediating dual RNA and DNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 406–417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1302, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickar-Oliver A., Gersbach C. A. (2019). The next generation of CRISPR-Cas technologies and applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 490–507. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0131-5, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pougach K., Semenova E., Bogdanova E., Datsenko K. A., Djordjevic M., Wanner B. L., et al. (2010). Transcription, processing and function of CRISPR cassettes in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1367–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07265.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyenson N. C., Gayvert K., Varble A., Elemento O., Marraffini L. A. (2017). Broad targeting specificity during bacterial type III CRISPR-Cas immunity constrains viral escape. Cell Host Microbe 22, 343.e3–353.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.016, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radovcic M., Killelea T., Savitskaya E., Wettstein L., Bolt E. L., Ivancic-Bace I. (2018). CRISPR-Cas adaptation in Escherichia coli requires RecBCD helicase but not nuclease activity, is independent of homologous recombination, and is antagonized by 5’ ssDNA exonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 10173–10183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky799, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A., Summerville L., Learn B. A., Debell L., Bailey S. (2020). Processing and integration of functionally oriented prespacers in the Escherichia coli CRISPR system depends on bacterial host exonucleases. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 3403–3414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012196, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C., Chin D., Ensminger A. W. (2017). Priming in a permissive type I-C CRISPR-Cas system reveals distinct dynamics of spacer acquisition and loss. RNA 23, 1525–1538. doi: 10.1261/rna.062083.117, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding S., Sternberg S. H., Marshall M., Gibb B., Bhat P., Guegler C. K., et al. (2015). Surveillance and processing of foreign DNA by the Escherichia coli CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 854–865. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C., Dy R. L., Mckenzie R. E., Watson B. N., Taylor C., Chang J. T., et al. (2014). Priming in the type I-F CRISPR-Cas system triggers strand-independent spacer acquisition, bi-directionally from the primed protospacer. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 8516–8526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku527, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. P. C., Bikard D. (2022). Microbial defenses against mobile genetic elements and viruses: who defends whom from what? PLoS Biol. 20:e3001514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001514, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollie C., Graham S., Rouillon C., White M. F. (2018). Prespacer processing and specific integration in a type I-A CRISPR system. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1007–1020. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1232, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollie C., Schneider S., Brinkmann A. S., Bolt E. L., White M. F. (2015). Intrinsic sequence specificity of the Cas1 integrase directs new spacer acquisition. eLife 4:e08716. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08716, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostol J. T., Marraffini L. A. (2019). Non-specific degradation of transcripts promotes plasmid clearance during type III-A CRISPR-Cas immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 656–662. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0353-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Maso J. A., Macho N. C., Bordanaba-Ruiseco L., Espinosa M., Coll M., Del S. O. L. A. R., et al. (2015). Plasmid rolling-circle replication. Microbiol. Spectr. 3, PLAS-0035-2014. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0035-2014, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samai P., Pyenson N., Jiang W., Goldberg G. W., Hatoum-Aslan A., Marraffini L. A. (2015). Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA cleavage during type III CRISPR-Cas immunity. Cell 161, 1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.027, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitskaya E., Semenova E., Dedkov V., Metlitskaya A., Severinov K. (2013). High-throughput analysis of type I-E CRISPR/Cas spacer acquisition in E. coli. RNA Biol. 10, 716–725. doi: 10.4161/rna.24325, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F., Cherepkova M. Y., Platt R. J. (2018). Transcriptional recording by CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA. Nature 562, 380–385. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0569-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova E., Jore M. M., Datsenko K. A., Semenova A., Westra E. R., Wanner B., et al. (2011). Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 10098–10103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104144108, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. A., Erdmann S., Mojica F. J., Garrett R. A. (2013). Protospacer recognition motifs: mixed identities and functional diversity. RNA Biol. 10, 891–899. doi: 10.4161/rna.23764, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiimori M., Garrett S. C., Graveley B. R., Terns M. P. (2018). Cas4 nucleases define the PAM, length, and orientation of DNA fragments integrated at CRISPR loci. Mol. Cell 70, 814.e6–824.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman S. L., Nivala J., Macklis J. D., Church G. M. (2017). CRISPR-Cas encoding of a digital movie into the genomes of a population of living bacteria. Nature 547, 345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature23017, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Abudayyeh O. O., Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Gootenberg J. S., Semenova E., et al. (2015). Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell 60, 385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmakov S., Smargon A., Scott D., Cox D., Pyzocha N., Yan W., et al. (2017). Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 169–182. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silas S., Lucas-Elio P., Jackson S. A., Aroca-Crevillen A., Hansen L. L., Fineran P. C., et al. (2017a). Type III CRISPR-Cas systems can provide redundancy to counteract viral escape from type I systems. eLife 6:e27601. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silas S., Makarova K. S., Shmakov S., Paez-Espino D., Mohr G., Liu Y., et al. (2017b). On the origin of reverse transcriptase-using CRISPR-Cas systems and their hyperdiverse, enigmatic spacer repertoires. mBio 8, e00897–e00917. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00897-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silas S., Mohr G., Sidote D. J., Markham L. M., Sanchez-Amat A., Bhaya D., et al. (2016). Direct CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA by a natural reverse transcriptase-Cas1 fusion protein. Science 351:aad4234. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4234, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R., Lawrence C. M., Wiedenheft B. (2013). CRISPR-mediated adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072911-172315, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staals R. H., Zhu Y., Taylor D. W., Kornfeld J. E., Sharma K., Barendregt A., et al. (2014). RNA targeting by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas Csm complex of Thermus thermophilus. Mol. Cell 56, 518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. H., Redding S., Jinek M., Greene E. C., Doudna J. A. (2014). DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturino J. M., Klaenhammer T. R. (2006). Engineered bacteriophage-defence systems in bioprocessing. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 395–404. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1393, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarts D. C., Mosterd C., Van Passel M. W., Brouns S. J. (2012). CRISPR interference directs strand specific spacer acquisition. PLoS One 7:e35888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035888, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamulaitis G., Kazlauskiene M., Manakova E., Venclovas C., Nwokeoji A. O., Dickman M. J., et al. (2014). Programmable RNA shredding by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas system of Streptococcus thermophilus. Mol. Cell 56, 506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.027, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamulaitis G., Venclovas C., Siksnys V. (2017). Type III CRISPR-Cas immunity: major differences brushed aside. Trends Microbiol. 25, 49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden M. J., Newsom S., Rajan R. (2020). CRISPR type II-A subgroups exhibit phylogenetically distinct mechanisms for prespacer insertion. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 10956–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013554, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H., Li J., Chang S., Lin S., Tian Y., Tian X., et al. (2019). Probing the behaviour of Cas1-Cas2 upon protospacer binding in CRISPR-Cas systems using molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 9:3188. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39616-1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., LI M., Gong L., Hu S., Xiang H. (2016). DNA motifs determining the accuracy of repeat duplication during CRISPR adaptation in Haloarcula hispanica. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 4266–4277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw260, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li J., Zhao H., Sheng G., Wang M., Yin M., et al. (2015). Structural and mechanistic basis of PAM-dependent spacer acquisition in CRISPR-Cas systems. Cell 163, 840–853. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Chesne M. T., Terns R. M., Terns M. P. (2015a). Sequences spanning the leader-repeat junction mediate CRISPR adaptation to phage in Streptococcus thermophilus. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 1749–1758. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Terns R. M., Terns M. P. (2015b). Cas9 function and host genome sampling in type II-A CRISPR-Cas adaptation. Genes Dev. 29, 356–361. doi: 10.1101/gad.257550.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra E. R., Semenova E., Datsenko K. A., Jackson R. N., Wiedenheft B., Severinov K., et al. (2013). Type I-E CRISPR-cas systems discriminate target from non-target DNA through base pairing-independent PAM recognition. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003742, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B., Zhou K., Jinek M., Coyle S. M., Ma W., Doudna J. A. (2009). Structural basis for DNase activity of a conserved protein implicated in CRISPR-mediated genome defense. Structure 17, 904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.019, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand T., Semenova E., Shiriaeva A., Fedorov I., Datsenko K., Severinov K., et al. (2020). Reproducible antigen recognition by the type I-F CRISPR-Cas system. CRISPR J. 3, 378–387. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2020.0069, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M., Drabavicius G., Silanskas A., Gasiunas G., Siksnys V., Wigley D. B. (2019). Structure of the DNA-bound spacer capture complex of a type II CRISPR-Cas system. Mol. Cell 75, 90.e5–101.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A. V., Liu J. J., Knott G. J., Doxzen K. W., Nogales E., Doudna J. A. (2017). Structures of the CRISPR genome integration complex. Science 357, 1113–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0679, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoganand K. N., Sivathanu R., Nimkar S., Anand B. (2017). Asymmetric positioning of Cas1-2 complex and integration host factor induced DNA bending guide the unidirectional homing of protospacer in CRISPR-Cas type I-E system. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 367–381. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1151, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef I., Goren M. G., Qimron U. (2012). Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 5569–5576. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks216, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebec Z., Manica A., Zhang J., White M. F., Schleper C. (2014). CRISPR-mediated targeted mRNA degradation in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5280–5288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku161, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Garrett S., Graveley B. R., Terns M. P. (2021). Unique properties of spacer acquisition by the type III-A CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 1562–1582. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kasciukovic T., White M. F. (2012). The CRISPR associated protein Cas4 is a 5′ to 3′ DNA exonuclease with an iron-sulfur cluster. PLoS One 7:e47232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047232, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Pan S., Liu T., Li Y., Peng N. (2019). Cas4 nucleases can effect specific integration of CRISPR spacers. J. Bacteriol. 201, e00747–e00818. doi: 10.1128/JB.00747-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]