Abstract

The review lays emphasis on the significance of 1,2,3-triazoles synthesized via CuAAC reaction having potential to act as anti-microbial, anti-cancer, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-tuberculosis, anti-diabetic, and anti-Alzheimer drugs. The importance of click chemistry is due to its ‘quicker’ methodology that has the capability to create complex and efficient drugs with high yield and purity from simple and cheap starting materials. The activity of different triazolyl compounds was compiled considering MIC, IC50, and EC50 values against different species of microbes. In addition to this, the anti-oxidant property of triazolyl compounds have also been reviewed and discussed.

The review lays emphasis on the significance of 1,2,3-triazoles synthesized via CuAAC reaction having potential to act as anti-microbial, anti-cancer, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-tuberculosis, anti-diabetic, and anti-Alzheimer drugs.

Introduction

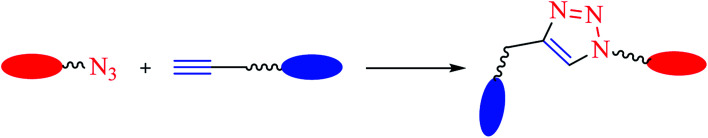

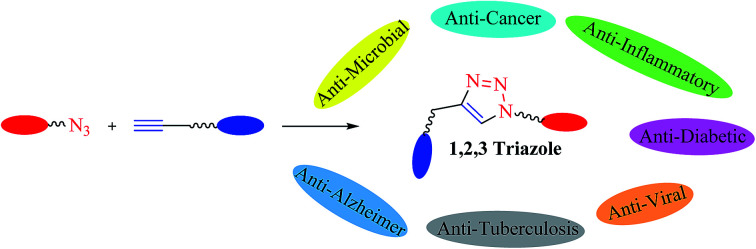

The consistently growing demand in the pursuit of medicinally potent compounds for drug discovery have given birth to simple and efficient synthetic routes for creating libraries of biologically active molecules.1 The synthesis of current drug analogs is one among some of the most relevant approaches in medicinal chemistry and the drug discovery process. Since the past two decades, there has been enormous development in reaction methodologies with focus on three fundamentals principles of synthesis: versatility, efficiency, and selectivity. The extensively explored reactions performed under these principles are termed as ‘Click Reactions’. They are further sub-classified into four brackets: (i) addition reaction to carbon–carbon multiple bonds, (ii) cycloaddition reactions (known under the title ‘Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition’), (iii) nucleophilic ring opening reactions of strained heterocyclic electrophiles, and (iv) none aldol carbonyl chemistry [MTC]. This Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between azides and alkynes yielding 1,2,3-triazoles (Fig. 1) is one of the most powerful among the click series of reactions.2–7 The structural framework of 1,2,3-triazole enables it to mimic different functional groups, justifying its wide use as a bioisostere for the synthesis of new active molecules possessing a broad range of biological activities that include antimicrobial, anticancer, and antiviral, along with antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-Alzheimer, and antioxidant properties.8,9 All these methodologies have permitted the successful design of novel drug analogs via combinatorial synthesis.

Fig. 1. Common reaction scheme leading to the formation of 1,2,3-triazole linked compounds.

The use of click chemistry to manufacture drugs with cohesive 1,2,3-triazole units via metal catalyzed alkyne–azide cycloaddition reaction have been developed to be an efficient tool. Click chemistry, as defined by Sharpless, involves high yielding reactions with wider scope, easily removable by-products, complete control of stereospecificity, and simplicity of procedure. The evolution of click chemistry is fine-tuned with pharmaceutical and materials research for generating libraries of molecules for drug discovery that makes it indispensable and evolutionary synthetic tool. The performance of this reaction on the cellular scale easily modifies biomolecules and cell surfaces for imaging purposes and functioning for physiological investigations.1 The prerequisite of drug modification is to overcome drug resistance, explore highly selective and less toxic drugs, to improve the pharmacokinetic profile, resulting in the need for an optimized process.10 The ability to obtain stable 1,2,3-triazolyl isosteres has resulted in their wide application in the drug discovery and drug design of bioactive molecules analogs. This necessity for novel chemotherapeutics has reinvigorated various research groups to synthesize triazole analogs.11,12 A compiled report on the pharmacological applications of 1,2,3-triazole linked molecules created via copper catalysed alkyne–azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction has not been published to the best of our knowledge. This review contains the compiled data of research articles published in the last 10 years (2010 onwards) with active pharmacological entities.

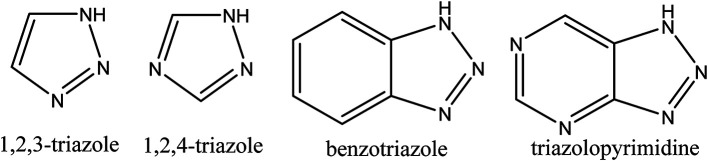

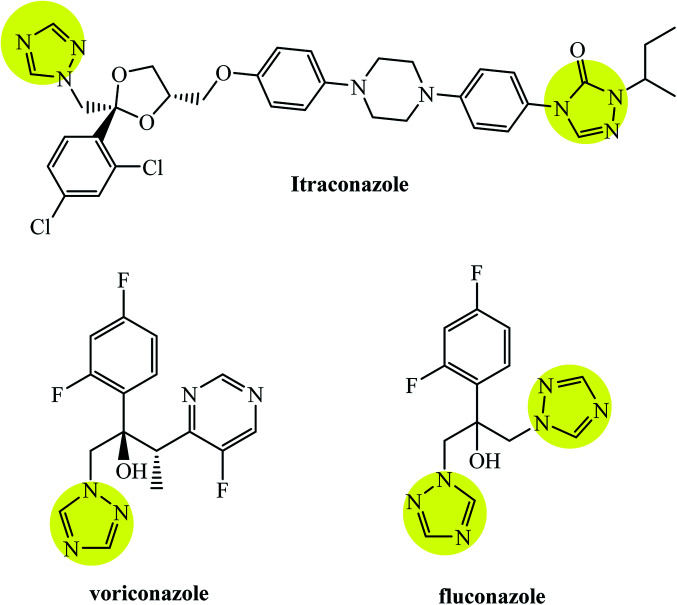

Triazoles including 1,2,3-triazole, 1,2,4-triazole, benzotriazole, triazolopyrimidine (Fig. 2), and their derivatives have attracted continuous interest in medicinal chemistry, and many drugs marketed currently are based on triazoles, for example pramiconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole as shown in Fig. 3.13 Thus, the role of heterocyclic compounds has become increasingly important in designing a new class of structural entities of medicinal importance due to the favorable properties of 1,2,3-triazole ring such as moderate dipole character, hydrogen bonding capability, and rigidity and stability under in vivo conditions, which are responsible for their enhanced biological activities.14–17

Fig. 2. The structure of pharmaceutically active triazole moieties.

Fig. 3. The structures of itraconazole, voriconazole and fluconazole containing triazole moieties.

Anti-microbial activity

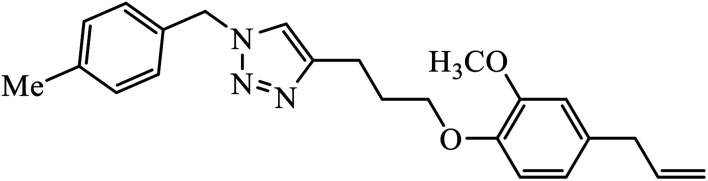

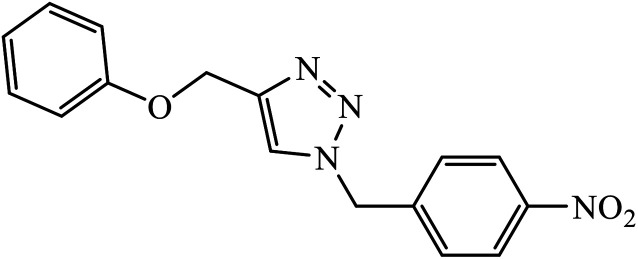

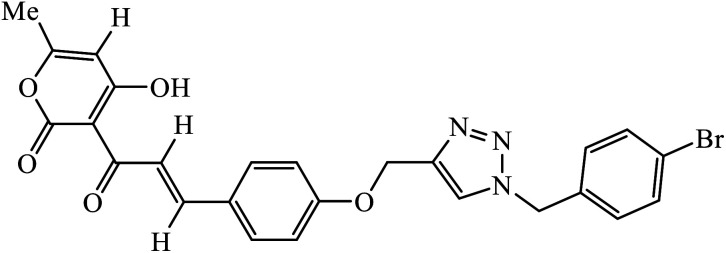

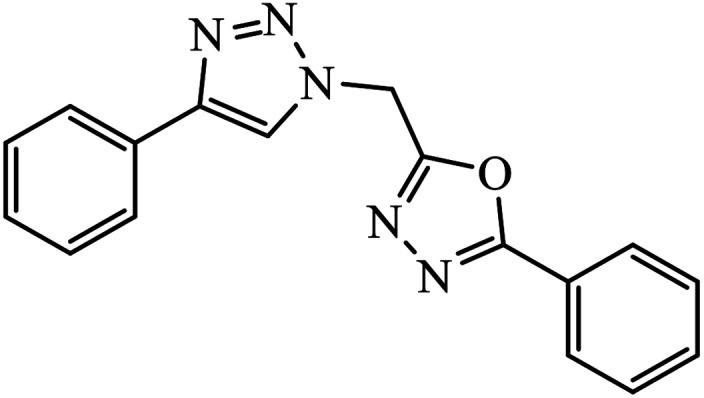

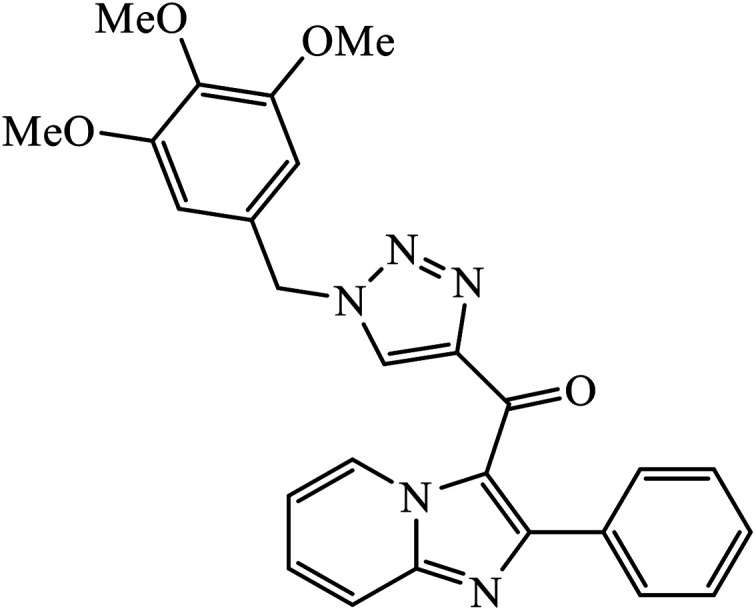

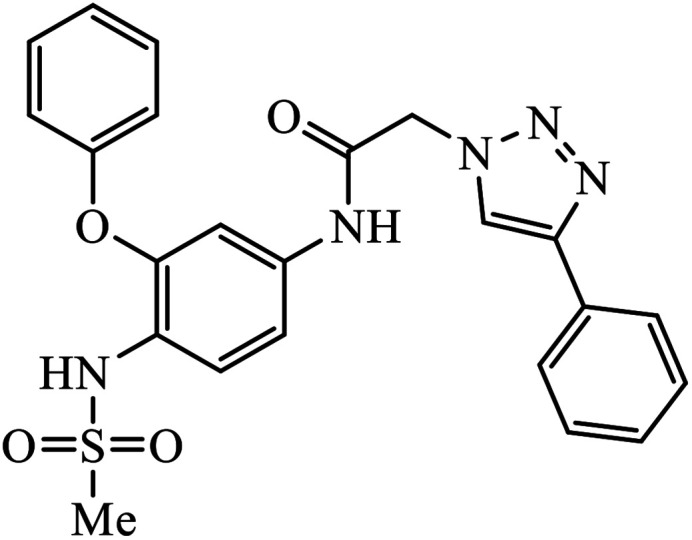

The 1,2,3-triazoles combine a framework consisting of N,N-backbone nuclei with various carbocyclic framework to act as potential anti-microbial agents, as compiled in Table 1. The activity of these dehydroacetic acid chalcone-1,2,3-triazoles (1) against bacterial strains (B. subtilis and E. coli) and fungal strains (Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans) prove their anti-microbial nature. The presence of a substituted methoxy group on the phenyl ring increases its potency with high activity towards these bacterial and fungal strains. It was observed that the compounds with terminal bromo and methoxy groups on the benzene ring exhibit better activity against most of the microorganisms, whereas in the case of presence of nitro group, better antifungal activity was observed in comparison to the methyl group. In addition, the molecular docking studies suggest that the activity of these compounds is a result of attachment of oxygen atom of the carbonyl group of compound 2 to form a hydrogen bond with Asn46 residue of the active site, whereas the phenoxy ring is hooked via in π–anion interaction with Glu50. Also, the triazole ring exhibits π–cation interaction with Arg136 with stacking of amide groups of Gly77 and Ile78 against the phenoxy ring.18–20

List of 1,2,3-triazolyl linked pharmacophores possessing anti-microbial activity observed using MIC and IC50 values.

| Comp. no. | Parent compound | Biological target | Anti-microbial activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

MIC (μM) | 15 | |

| H37Rv strain | 4.11 μM | |||

| 2 |

|

MIC (μM) | 18 | |

| E. coli | 0.0030 | |||

| B. subtilis | 0.0030 | |||

| A. niger | 0.0060 | |||

| C. albicans | 0.0120 | |||

| 3 |

|

MIC (μmol mL−1) | 21 | |

| E. coli | 0.0032 | |||

| S. epidermidis | 0.0032 | |||

| 4 |

|

MIC (μM) | 22 | |

| H37Rv | 5.1 | |||

| 5 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 24 | |

| S. aureus, MRSA strain, and S. epidermidis | 3.25 | |||

| 6 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 25 | |

| (Gram −ve bacteria) | ||||

| E. coli | 31.25 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 250 | |||

| (Gram +ve bacteria) | ||||

| S. aureus | 31.25 | |||

| S. pyogenus | 250 | |||

| (Antifungal) | ||||

| C. albicans | 250 | |||

| 7 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 26 | |

| MRSA strain | 4 | |||

| 8 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 27 | |

| M. catarrhalis | 0.5 | |||

| 9 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 29 | |

| (Gram positive) | ||||

| MRSA strain | 12.5 | |||

| B. subtilis | 12.9 | |||

| B. cereus | 12.0 | |||

| (Gram negative) | ||||

| E. coli | 15.5 | |||

| K. pneumonia | 25.3 | |||

| P. vulgaris | 28.4 | |||

| 10 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 30 | |

| (Gram positive) | ||||

| B. cereus | 32 | |||

| S. aureus | 27 | |||

| (Gram negative) | ||||

| E. coli | 27 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 22 | |||

| 11 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 31 | |

| H37Rv strain | 0.78 | |||

| 12 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 33 | |

| B. subtilis | 10 | |||

| E. coli | 10 | |||

| 13 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 34 | |

| H37Rv | 0.78 | |||

| 14 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 35 | |

| S. aureus | 0.5 | |||

| 15 |

|

MIC (mg mL−1) | 36 | |

| Antibacterial | ||||

| S. aureus | 0.625 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 0.625 | |||

| E. faecalis | 0.625 | |||

| Antifungal | ||||

| C. albicans | 1.25 | |||

| A. brasiliensis | 1.25 | |||

| 16 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 37 | |

| S. aureus | 64 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 16 | |||

| S. dysenteriae | 16 | |||

| 17 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 38 | |

| P. falciparum | 9.6 | |||

| 18 |

|

E. coli | 14 ± 0.6 | 39 |

| B. subtilis | 08 ± 0.7 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 10 ± 0.3 | |||

| 19 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 40 | |

| L. donovani | 1.14 | |||

| P. falciparum (D6 strain) | 4.11 | |||

| P. falciparum (W2 strain) | 4.49 | |||

| 20 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 41 | |

| (a) (Antifungal) | ||||

| F. oxysporum | >64 (128) | |||

| F. gramillarium | >64 (128) | |||

| (b) (Antibacterial) | ||||

| E. coli | >64 (>64) | |||

| P. putida | >64 (>64) | |||

| S. aureus | >64 (>128) | |||

| 21 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 42 | |

| H37Rv | 0.2 | |||

| 22 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 45 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 12.5 | |||

| 23 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 46 | |

| Antibacterial | ||||

| B. subtilis | 25 | |||

| E. coli | 25 | |||

| Antifungal | ||||

| F. recini | 25 | |||

| 24 |

|

MIC (μg mL−1) | 47 | |

| E. faecalis | 12.5 | |||

| 25 |

|

Zone of inhibition (mm) | 48 | |

| Gram-positive | ||||

| S. aureus | 15 ± 0.1 | |||

| B. subtilis | 15 ± 0.4 | |||

| S. epidermidis | 16 ± 0.3 | |||

| Gram-negative | ||||

| P. aeruginosa | 14 ± 0.3 | |||

| E. coli | 13 ± 0.3 | |||

| K. pneumonia | 14 ± 0.4 | |||

| 26 |

|

Zone of inhibition (mm) | 49 | |

| E. coli | 15 | |||

| K. pneumonia | 22 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 25 | |||

| P. vulgaris | 20 | |||

| S. typhi | 22 | |||

| P. putida | 10 | |||

| Urinary tract infection organism | 18 | |||

| 27 |

|

Zone of inhibition (diameter in mm) at 0.5 mg per 100 μL | 50 | |

| P. aeruginosa | 17 ± 0.2 | |||

| S. aureus | 12 ± 0.2 | |||

| K. pneumoniae | 12 ± 0.2 | |||

| E. coli | 15 ± 0.3 | |||

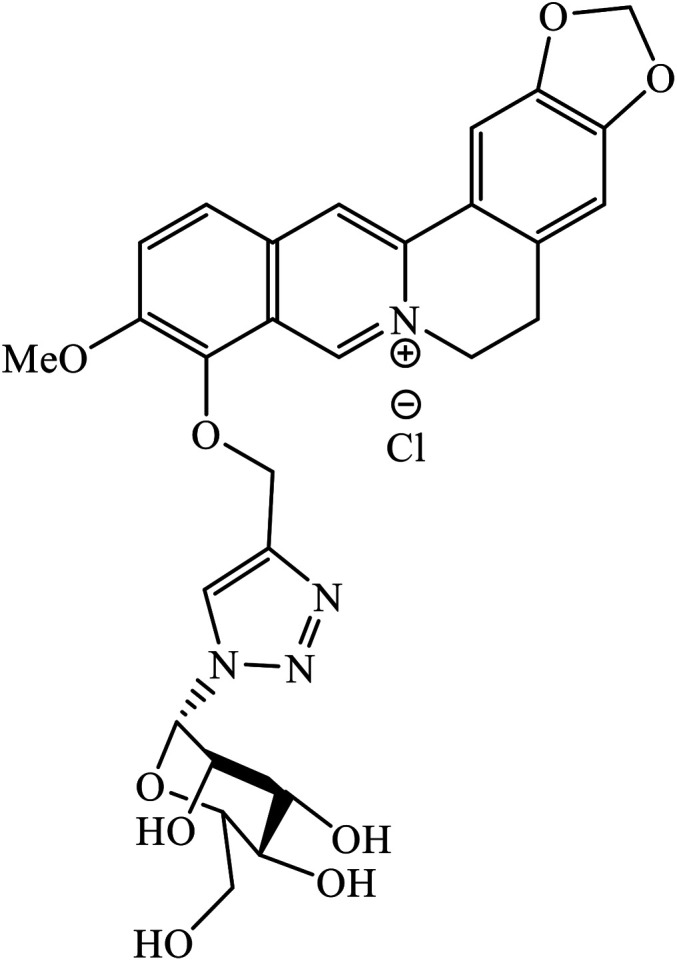

The merging of two pharmacophore units results into the formation of chalcone-1,2,3-triazole conjugates, which also serve as antimicrobial agents. Among the sequence of series of such triazoles screened, only compound 3 displayed high activity against E. coli and S. epidermidis due to presence of 4-nitro group. Molecular docking studies of compound 3 revealed that the carbonyl group participated in hydrogen bonding with His95, Ala96, and Ser121 residues. 1,4-Substituted triazole attached to the phenyl ring is engaged in pi–alkyl interactions with π-electrons, while the same phenyl ring also demonstrated π–alkyl interactions with Val120.21 Srivastava et al. created a series of β-d-ribofuranosyl coumarinyl-1,2,3-triazoles using Cu(i) catalysed cycloaddition reaction having potent anti-mycobacterial activity against mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. The pharmacophore entity 4 possesses excellent inhibitor capacity against mycobacterium tuberculosis in comparison to the standard drug. The target site of 1,2,3-triazole is mycobacterial InhA and DNA gyras enzymes, and the binding of (4) molecule with these enzymes is essentially through hydrogen bonding.22,23

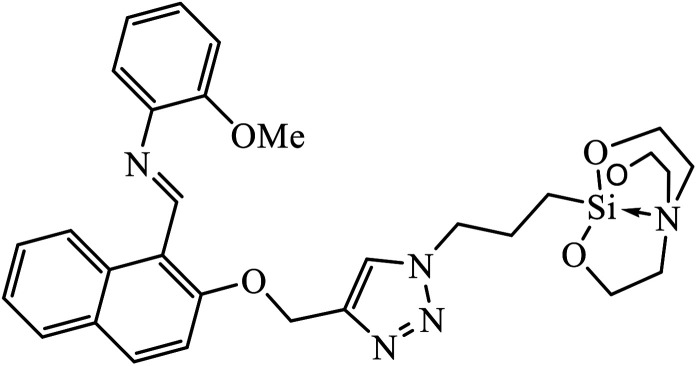

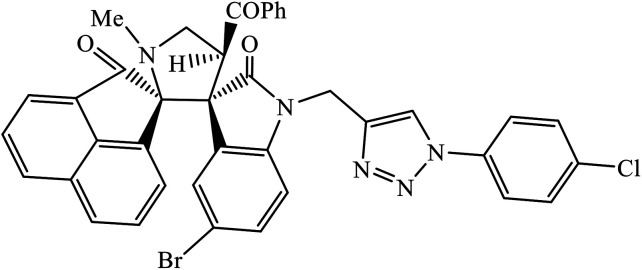

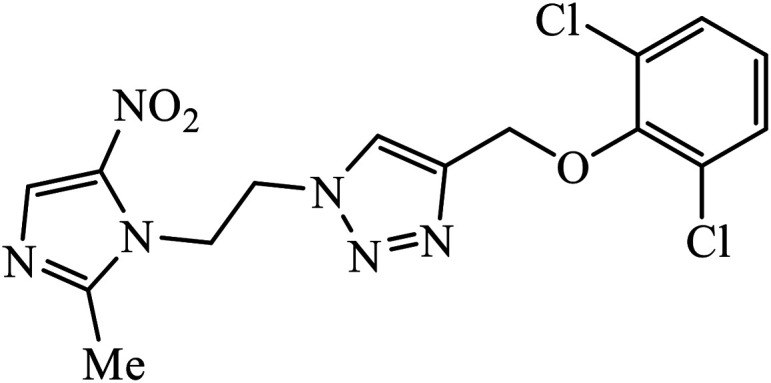

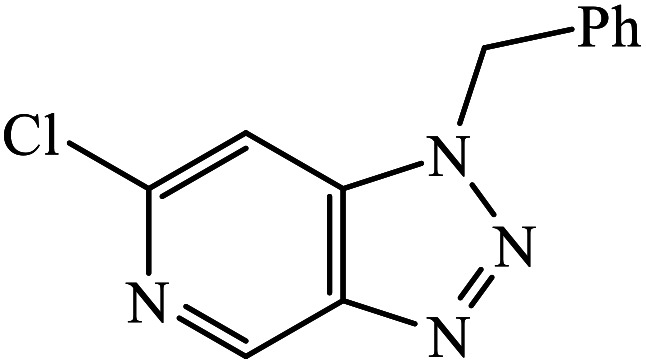

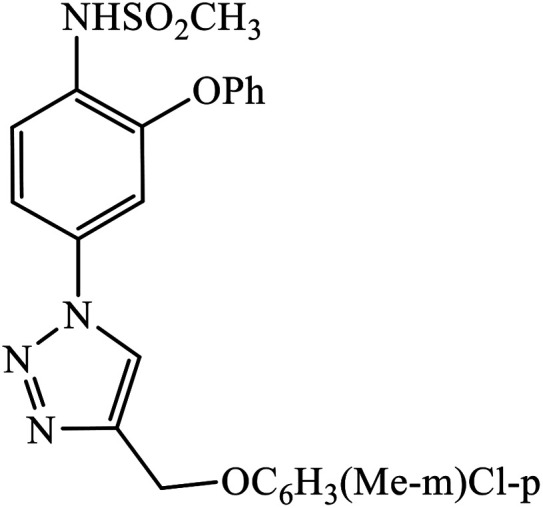

Another class of compounds, containing Schiff base linked to 1,2,3-triazole with terminal silatrane group, were synthesized by single step ‘click silylation’ reaction. Among the series of molecules screened by Singh et al., it was discovered that only molecule 5 showed excellent inhibitor activity against S. aureus, MRSA, and S. epidermidis due to the presence of electron donating methoxy group.24 In another series, novel dispiropyrrolidine and dispiropyrrolizidine-fused triazole conjugates were prepared via a facile one-pot four-component cycloaddition reaction. Upon evaluation of the antibacterial and antifungal activities, it was noticed that the molecule containing bromo group (6) on the indolinone and triazole cycle leads to an increase in the activity. In the same fashion, another molecule containing methoxy group on the triazole ring and a bromo substituent on the indolinone ring results in increase in its antibacterial activity. The compounds having methyl substitution at the 1,2,3-triazole unit show excellent antifungal activity.25 Thus, a series of metronidazole-triazole hybrids were formulated having anti-methicillin resistant S. aureus activity. It was found out that the compounds with halogen substituent at the benzene nucleus show excellent activity as compared to other substituents, such as t-Bu, Me, CHO, and NO2, which display less inhibition activity towards MRSA strains. Compound 7 with 2,4-dichloro substituents at the phenyl ring displays excellent activity towards MRSA strains in comparison to the reference oxacillin drug.26

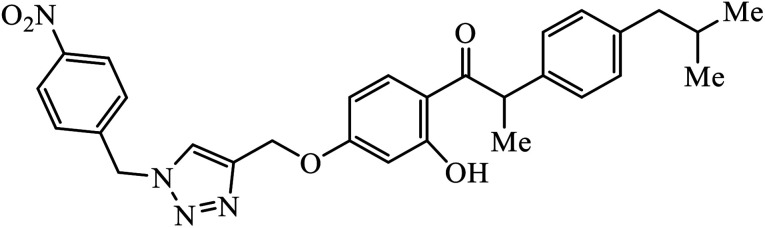

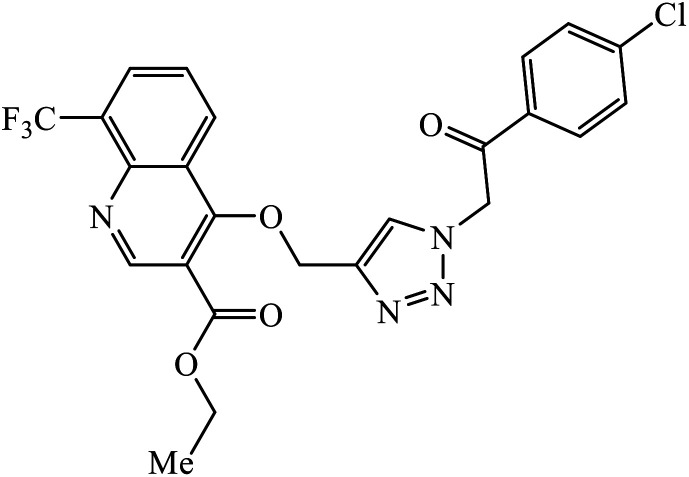

The benzo-fused nitrogen and sulfur heterocycles containing 1,2,3-triazole conjugates were synthesized as efficient antibacterial agents. The inhibition activity of N/S containing compounds was tested against selected Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Compound 8 bearing p-chlorophenyl or p-fluorophenyl group having linkage with 4th position of the triazole displayed outstanding inhibition activity against M. catarrhalis.27,28 Click chemistry was used to create a novel series of 1,2,3-triazole compounds from ibuprofen. The activity of these compounds was tested against bacterial strains and the results indicated anti-bacterial activity for the compounds with benzyl or phenyl ring with 1,2,3-triazole moiety containing electron withdrawing group at para or meta position of the rings. Compound 9 with 4-nitrobenzyl group hooked to 1,2,3-triazole moiety resulted in excellent activity. The interactions of compound 9 in the COX-2 active site can possibly cause the higher activity.29

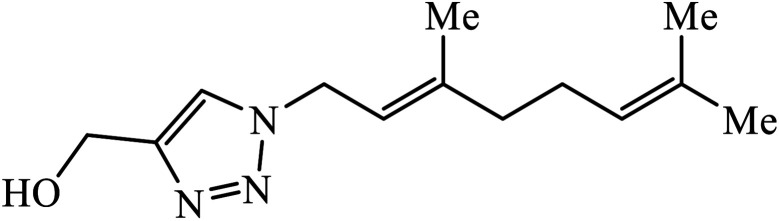

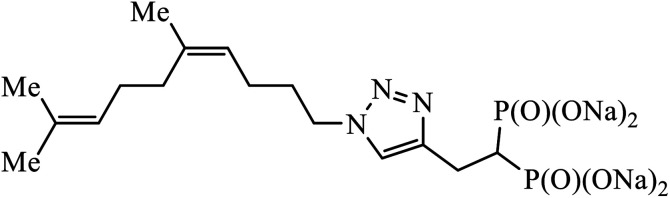

The use of geraniol as a precursor for synthesizing a new category of 1,2,3-triazole was made through cycloaddition reaction via click chemistry and their activity was evaluated against four bacterial strains. Compound 10 having electron withdrawing groups such as –OH and –Cl increased the activity against all the bacterial strains. Compound 10 is bound via van der Waals, hydrophobic, π-stacking, and hydrogen bond interactions. It is deduced that the triazole derivative (10) is also surrounded by van der Waals linked residues. The hydroxyl substituent at C4-position of the triazole moiety is bound by a van der Waals pocket, which strengthened the binding affinity, thus leading to increased antimicrobial activity of the compound.30

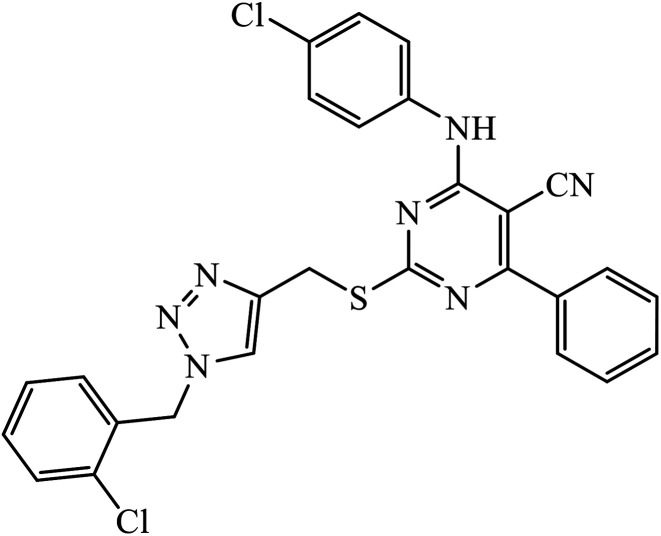

Rajua et al. synthesized a novel series of pyrimidine based 1,2,3-triazoles via Cu(i) catalysed cycloaddition reaction, which act as anti-tubercular agents. All the synthesized compounds were tested against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strain and the results indicate that the presence of electronegative atom on 1,2,3-triazolyl compound 11 led to the prominent activity of that compound. The molecular docking studies further verify this potent activity as a result of presence of moderately extensive hydrogen bonds of Ser228 and Cys387, π–alkyl with His132 and Tyr314, strong hydrophobic bonds of Pro316, Ala244, Lys134, Lys367, and Val365 along with Tyr314 van der Waals interaction with the triazole ring.31,32

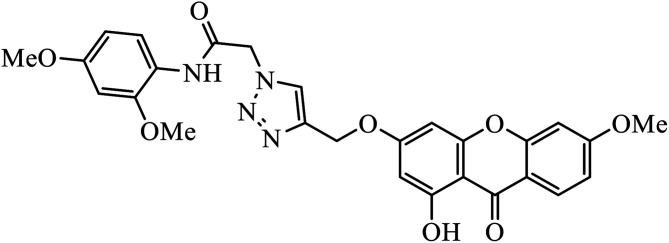

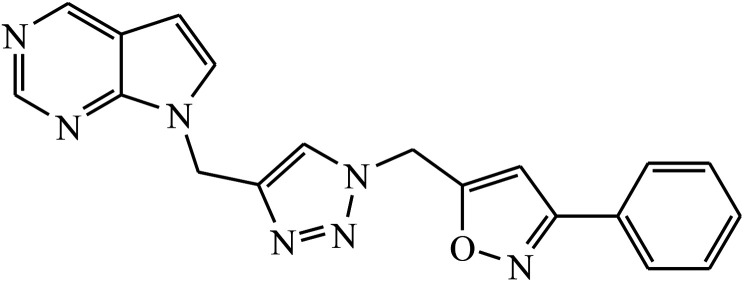

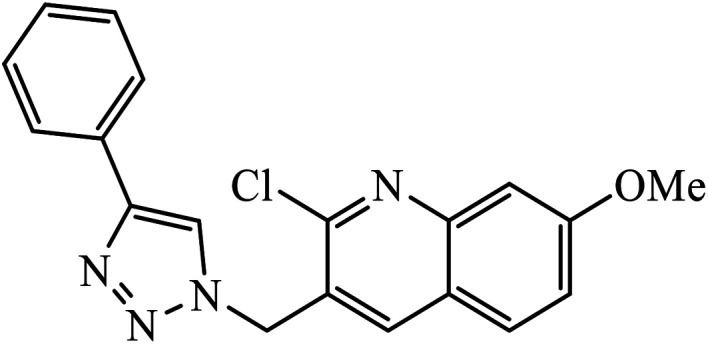

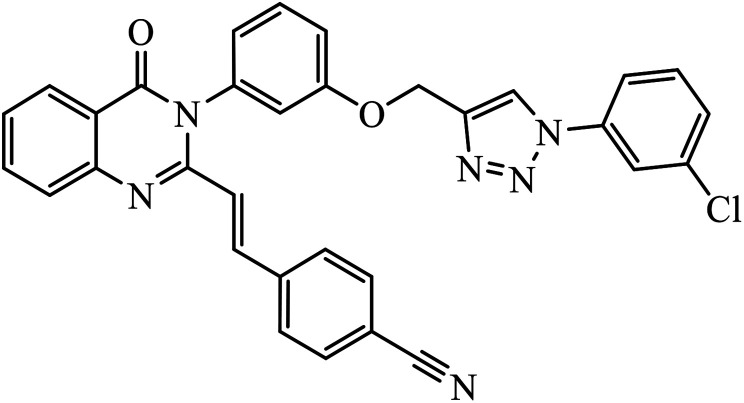

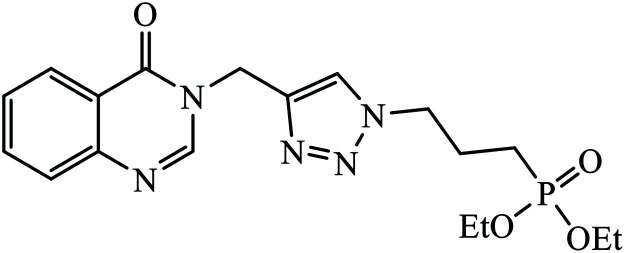

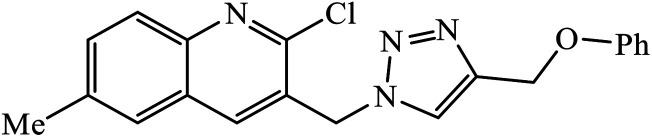

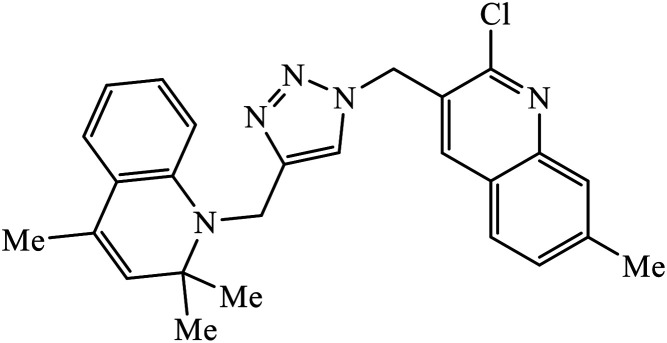

In another set, a series of 2-chloro-3-((4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole-1-yl)methyl)quinolone derivatives were synthesized and were evaluated to have good antibacterial and antifungal activities. The activity of compound 12 was due to the attachment of methoxy group on the benzyl ring, which was proved to have excellent activity towards bacterial strains. Further, it was observed that upon replacement of the methoxy group with a methyl group, it is converted to a good antifungal agent.33 The 1,2,3-triazole compounds linkage with spirochromone conjugates 13 have good activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (virulent strain H37Rv). Compound 13 displays high activity in comparison to the standard drug ethambutol, which further increases in presence of an aromatic group at 4th position of 1,2,3-triazole and cyclohexyl group at the 2nd position of the chromone ring.34 1,2,3-Triazole linked 4(3H)-quinazolinone derivatives were synthesized and they were found to be good antibacterial agents. Compound 14 is highly active against a gram-particular positive bacterial strain, i.e., Staphylococcus aureus but inactive towards gram-negative bacterial strains. Its high activity is due to the presence of an electronegative atom on the phenyl ring, which is directly attached to 1,2,3-triazole.35 Another set of halogen linked 1,2,3-triazole containing quinazolin-4-one 15 was found to have excellent activity owing to the presence of a phosphonoalkyl group located at the C4 position in the 1,2,3-triazole ring. These pharmacophore drug molecules were potentially active against both gram-negative bacteria such as S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. faecalis with the MIC value of 0.625 mg mL−1. Moreover, the linkage of bromo or nitro group at the C6 position of quinazolinone moiety led to a drastic fall in the activity towards the bacterial strain. In addition, the unsubstituted quinazolinone compounds exhibit potential antifungal activity against C. albicans and A. brasiliensis with MIC value of 1.25 mg mL−1.36

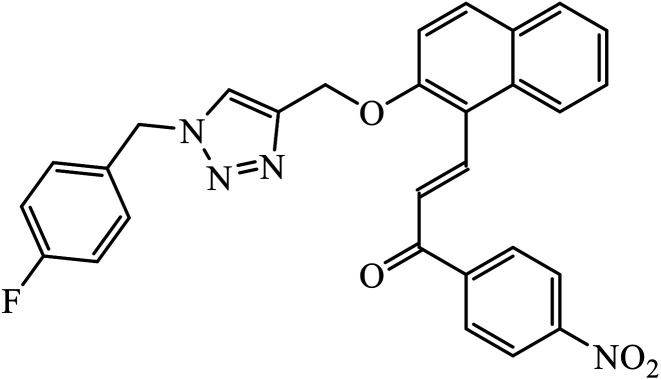

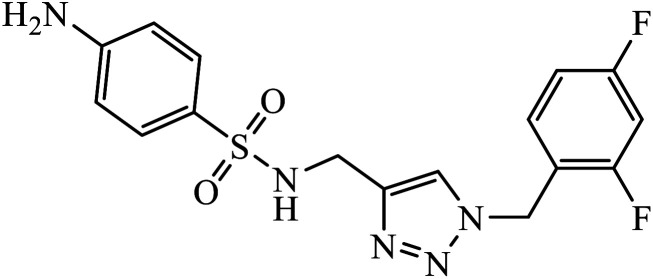

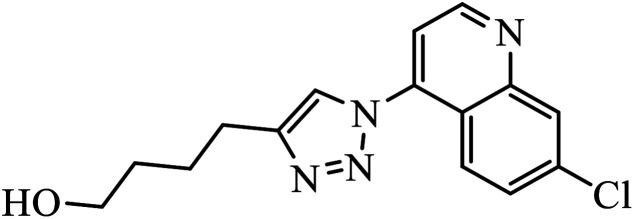

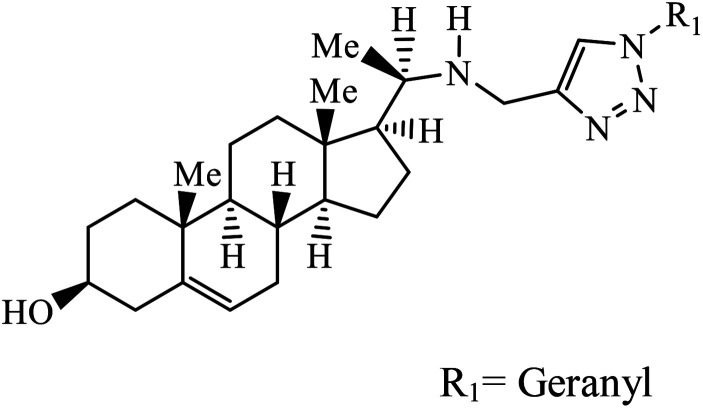

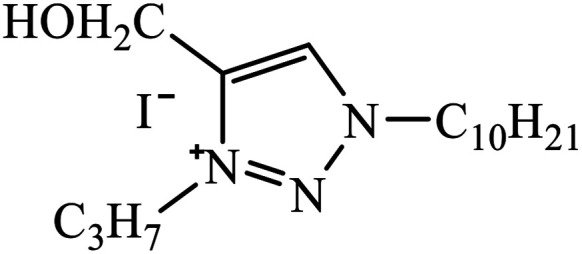

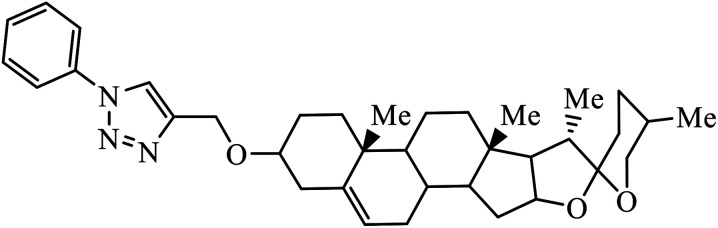

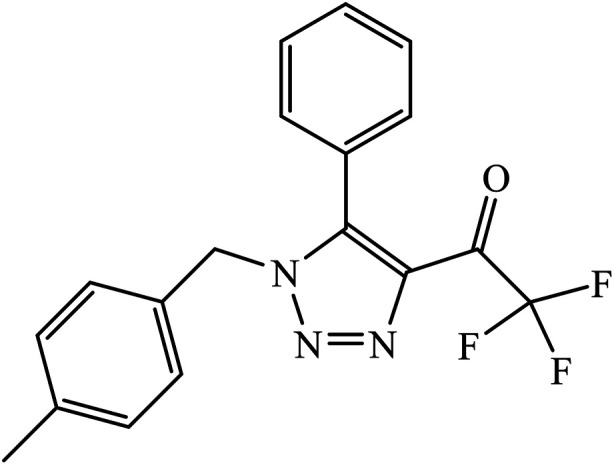

Sulfanilamide-derived 1,2,3-triazoles generated by click chemistry were examined as potent antibacterial and antifungal agents. The analysis indicated that compound 16 has good activity against three selected bacterial strains and contains two highly electronegative atoms on the phenyl ring. Fundamentally, the activity of such a compound depends upon the terminal alkyl chain and the substitution on the phenyl ring in the compound.37 Similarly, the series of 7-chloroquinolinotriazoles having unique substituents in the 1,2,3-triaole moiety were synthesized and examined for the antimalarial activity. Compound 17 with a side chain hydroxyl group gives the best antimalarial activity.38 Further, 8-trifluoromethylquinoline based 1,2,3-triazole 18 derivative showed antimicrobial activity due to the presence of electron withdrawing group such as –Cl, which enhances their activity.39 1,2,3-Triazolylsterols 19 synthesized using click chemistry were found to have excellent antiparasitic properties against L. donovani, P. falciparum (D6 strain), and P. falciparum (W2 strain). The activity of compound 19 depends upon the length of the substituent attached to 1,2,3-triazole, i.e., the presence of a long chain on triazole increases the activity of the compound.40

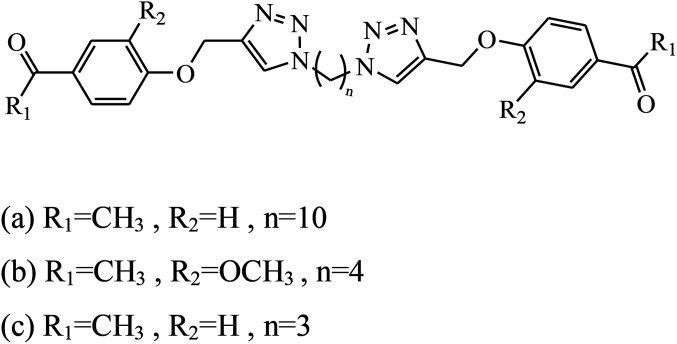

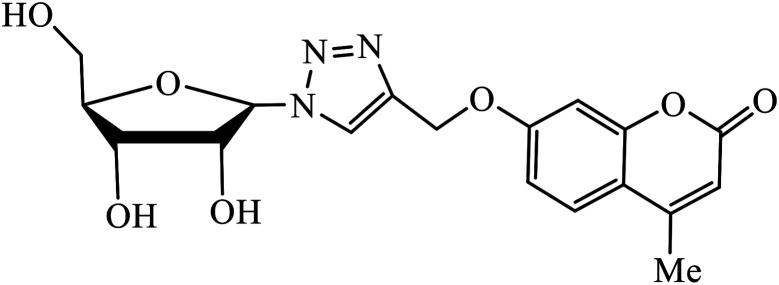

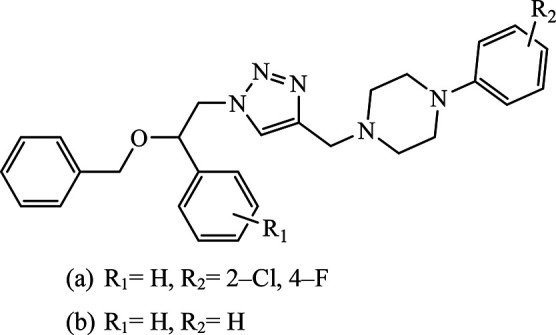

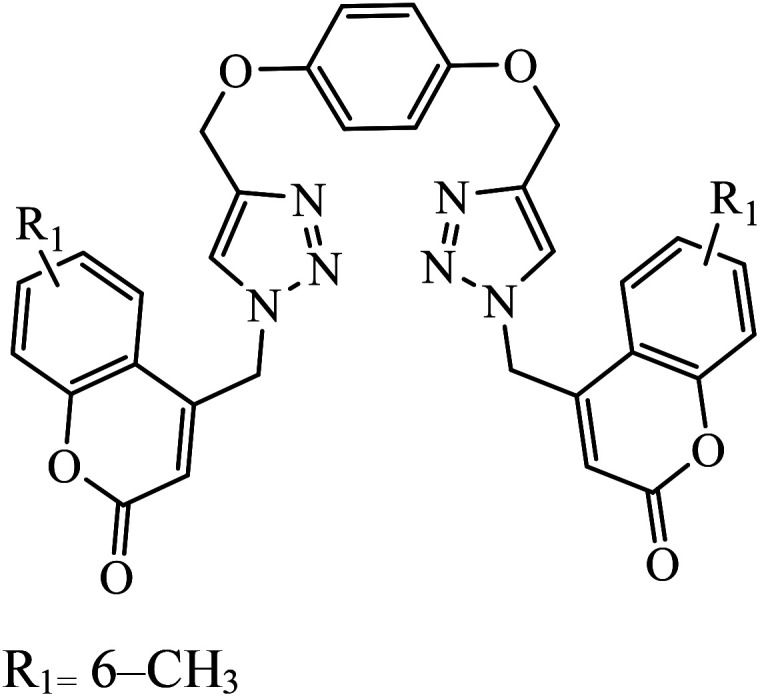

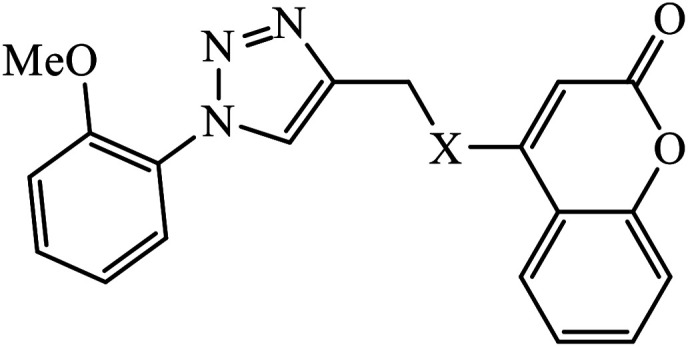

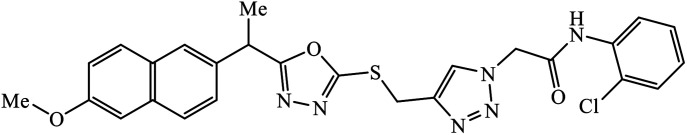

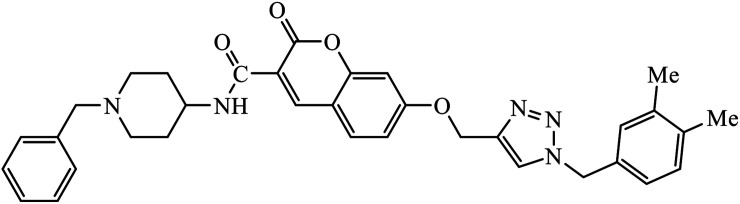

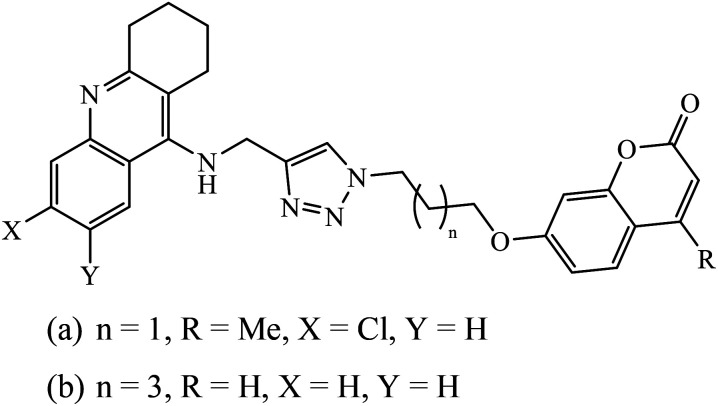

Piperazine-triazole derivatives synthesized via click chemistry act as good antimicrobial agents with potential inhibition activity as antibacterial and antifungal agents. The studies prove that compound 20a containing electron-withdrawing groups on phenyl ring has better antibacterial activity and in the case of no electron-withdrawing groups on the phenyl ring, it acts as an anti-fungal 20b.41 Mono and bis-aryloxy linked coumarinyl triazoles 21 act as anti-tubercular agent and the results indicated that bis-triazoles are more active than mono-triazoles. The activity of these compounds is regulated by the ability of 1,2,3-triazole and the phenoxy moiety to form hydrogen bonds with the protein at the site of the receptor. Moreover, the activity of these compounds increases in the presence of two triazoles and coumarin moieties in the compound. The high activity of these compounds is supported by the molecular docking studies carried out against InhA-D148G mutant in the complex with NADH, showing better hydrogen binding in the presence of two triazole rings. It was discovered that by increasing the bulkiness of the compound, the ability to create good hydrogen bonding also increases, resulting in better activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv.42–44

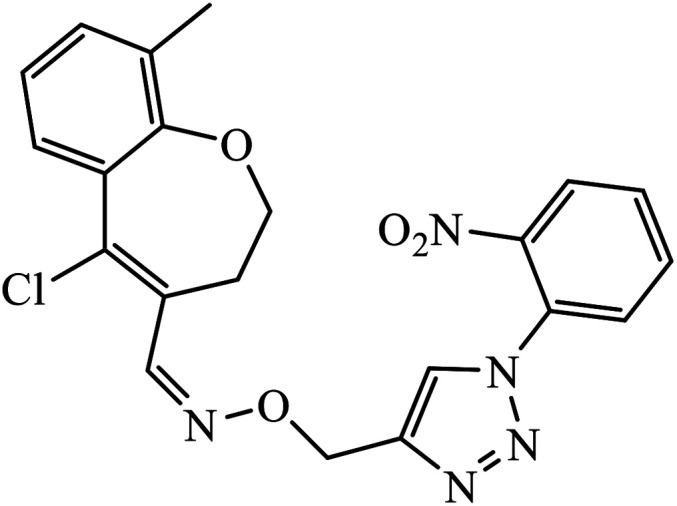

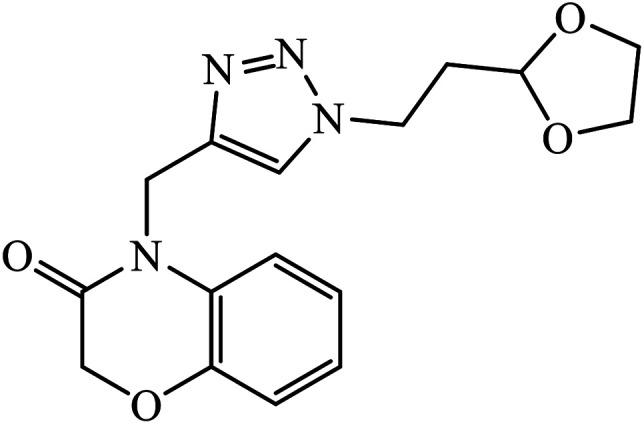

The oxazole conjoined 1,2,3-triazole derivative 22 presented good inhibition activity against P. aeruginosa with MIC value of 12.5 μg mL−1 and mild activity against S. epidermidis with MIC value of 50 μg mL−1, which is attributed to the presence of an oxadiazole ring.45 The 1,2,3-triazole ring fused with pyridine/pyrimidine was designed and its antimicrobial activity was evaluated. Compound 23 showed excellent antibacterial as well as antifungal activity.46 Coumarin hooked via 1,2,3-triazole conjugate 24 to varied alkyl, phenyl, and heterocyclic moieties at the C-4 position of the triazole nucleus possessed phenomenal antibacterial activity against E. faecalis, which was a result of the compound having a 2-OMe-Ph group attached at the triazole nucleus and an –OCH2– linker.47 A similar class of oxadiazole substituted 1,2,3-triazole derivative 25 containing the structural features of ibuprofen/naproxen appeared to be effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. One of synthesized compound was identified as the most interesting as it exhibited activities against almost all the species because of the presence of Cl at the o-position on the benzene ring, which increases its activity.48 A novel series of 1,2,3-triazolyl quinolones were designed via CuAAC and examined as antibacterial agents. The compound having unsubstituted phenyl moiety or phenoxymethylene 26 was more active as compared to the compound containing the electron donating methoxy functional group on the quinolone ring.49 Moreover, the benzoxepine-oxime-1,2,3-triazole hybrid was capable of inhibiting the bacterial strains. Compound 27 was identified as the most interesting among all the designed compounds as it showed notable activities against almost all the bacterial strains and against the NCI-H226 cancer cell, it showed GI50 value of 46.8 μM.50

Anti-cancer activity

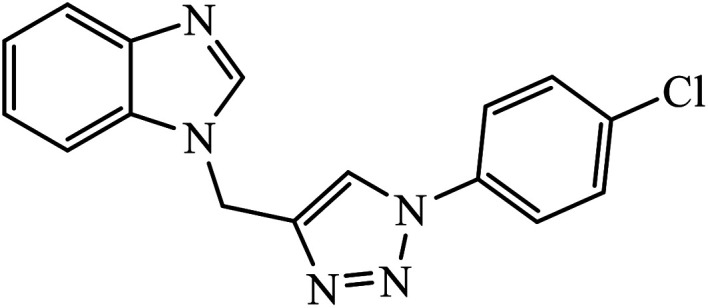

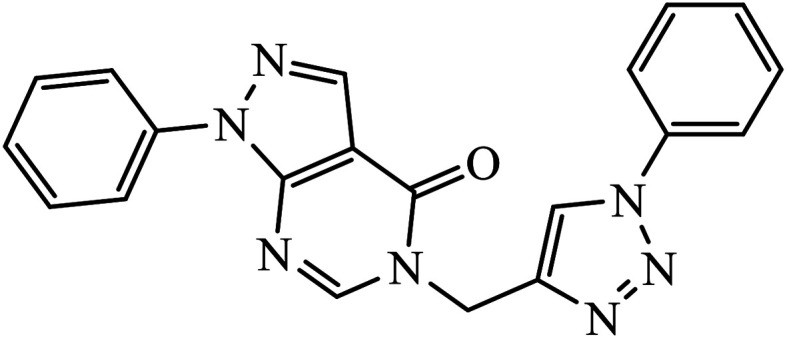

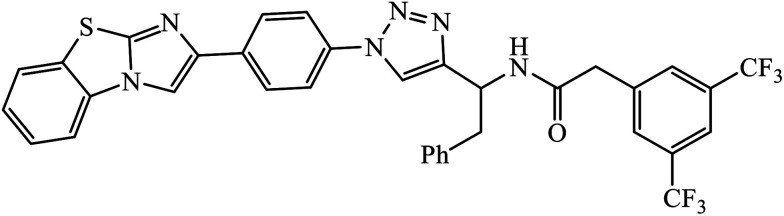

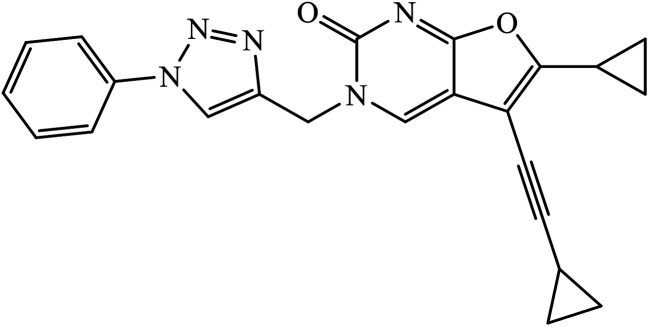

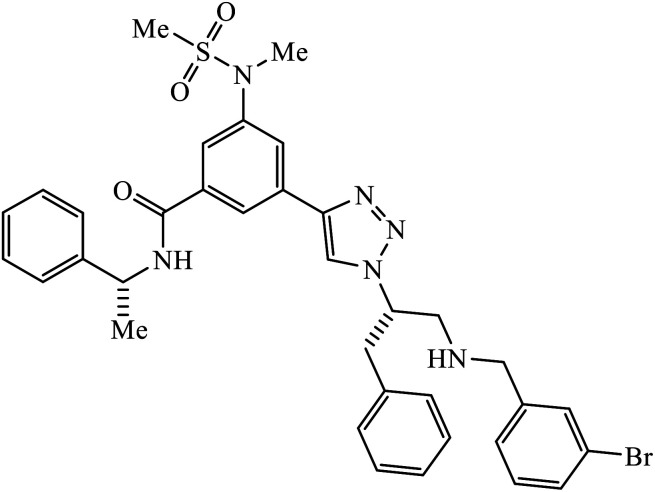

1,3,4-Substituted-1,2,3-triazoles were synthesized as potential antitumor drugs, as shown in Table 2. The analysis of their cytotoxicity against the tumor cell line HL-60 (myeloid leukemia), MCF-7 (breast cancer), HCT-116 (colon cancer), and non-tumor cells (vero cell) gave excellent results. Different IC50 values were obtained for the tumor cells for compound 28, clearly indicating a strong affect towards the HL-60 cancer cell line. The IC50 value is below 10 μM for the cancer cell lines and for the non-tumor cell, IC50 values were less than 100 μM.51 Pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-ones tied to 1,2,3-triazoles were synthesized with different substituents. Among the series of synthesized compounds, few were highly effective towards C6 glioma cell line and U87 cancer cell lines. Compound 29 has potential to capture the cell at the S-phase of the cell cycles and gave rise to apoptosis in the U87 GBM cell lines. These compounds are cytotoxic towards both C6 and U87 cell lines and IC50 value for U87 is less as compared to that for C6, which means that U87 is highly affected by these compounds, as shown in Table 2. The ligand binds in the hydrophobic pocket of the protein kinase domain and the binding mode is stabilized by the formation of hydrogen bonds between the ligand and active site residues of the protein.52–55 Another compound 30 is a 1,2,3-triazole-based inhibitor, which is active against HGF-induced scattering of MDCK and GTL-16 cancer cells. The binding mode of the new compound is similar to that of the active compound triflorcas; also, the range of IC50 of the new compound is similar to that of triflorcas. The molecular docking studies show that the binding of benzothiazole ring occurs via weak hydrogen bonded interaction with the NH backbone of Met1160 through the S-atom, thus establishing hydrophobic contacts with Tyr1159.56–59

Compiled list of 1,2,3-triazole linked compounds possessing anti-cancer activity as observed using IC50 values.

| Sr. no. | Parent compound | Biological target | Anti-cancer activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 51 | |

| HL-60 | 3.4 ± 1.9a | |||

| MCF-7 | 18.2 ± 7.2a | |||

| 29 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 52 | |

| C6 | 15.02 | |||

| U85 | 4.6 | |||

| 30 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 56 | |

| MDCK | 0.6 | |||

| 31 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 60 | |

| GGDPS | 1.3 ± 0.2 | |||

| 32 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 61 | |

| HeLa | 7.93 | |||

| 33 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 62 | |

| HEP3B | 0.5 | |||

| HT-29 | 5.7 | |||

| 34 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 67 | |

| A549 | 0.51 ± 0.32 | |||

| 35 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 68 | |

| A549 | 2.9 ± 0.25 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 3.35 ± 0.37 | |||

| 36 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 71 | |

| HT29 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |||

| DU145 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | |||

| 37 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 74 | |

| DU145 | 8.17 | |||

| 38 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 75 | |

| Lung (A549) | 5.54 | |||

| 39 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 76 | |

| EC-109 | 1.42 ± 1.25 | |||

| MCF-7 | 6.52 ± 0.23 | |||

| MGC-803 | 5.85 ± 0.15 | |||

| 40 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 79 | |

| GBM 95 | 28.7 | |||

| GBM 02 | 44.9 | |||

| U87 | 27.1 | |||

| 41 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 80 | |

| MGC-803 | 0.73 ± 0.11 | |||

| MCF-7 | 5.67 ± 0.91 | |||

| PC-3 | 11.61 ± 1.59 | |||

| EC-109 | 2.44 ± 0.10 | |||

| 42 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 81 | |

| Hep-G2 | 2.67 | |||

| HeLa | 6.51 | |||

| 43 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 82 | |

| MCF-7 | 0.301 | |||

| HeLa | 0.725 | |||

| 7721 | 0.502 | |||

| 44 |

|

IC50 (μM) ± SD | 83 | |

| (a) HeLa | 17.754 ± 0.754 | |||

| (b) CaSki | 14.925 ± 0.078 | |||

| (c) SK-OV-3 | 33.259 ± 1.534 | |||

| 45 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 84 | |

| Aurora A | 0.37 | |||

| Aurora B | 3.58 | |||

| 46 |

|

IC50 (μM) ± SD | 85 | |

| HL-60 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | |||

| SMMC-7721 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | |||

| A-549 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | |||

| MCF-7 | 1.70 ± 0.26 | |||

| SW480 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | |||

| 47 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 86 | |

| Tyrosinase | 26.20 ± 1.55 | |||

| 48 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 87 | |

| Abl kinase | 1.9 ± 0.1 | |||

| 49 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 88 | |

| MCF-7 | 10.4 ± 1.7 | |||

| HT-29 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | |||

| MOLT-4 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | |||

| 50 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 89 | |

| HepG2 | 0.0267 | |||

| 51 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 90 | |

| MG-63 | 18.05 ± 0.69 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 16.61 ± 1.20 | |||

| HDF | 22.83 ± 1.42 | |||

| 52 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 91 | |

| SKOV-3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | |||

| PC-3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | |||

| MCF7 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |||

| 53 |

|

GI50 (μM) | 92 | |

| HCT-15 | 52.5 | |||

| NCI-H226 | 41.3 | |||

| 54 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 93 | |

| HCT-15 | 22.4 | |||

| 55 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 94 | |

| A549 | 6.7 ± 0.15 | |||

| HepG2 | 9.8 ± 0.12 | |||

| HeLa | 7.9 ± 0.22 | |||

| DU145 | 5.9 ± 0.15 | |||

| 56 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 95 | |

| PDE4B inhibition | 5.014 | |||

| 57 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 96 | |

| A549 | 8.7 ± 0.24 | |||

| 58 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 97 | |

| A549 | 11.1 ± 0.16 | |||

| MCF 7 | 10.8 ± 0.11 | |||

| 59 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 98 | |

| A549 | 9.8 ± 0.12 |

Represents the maximum possible deviation from the results.

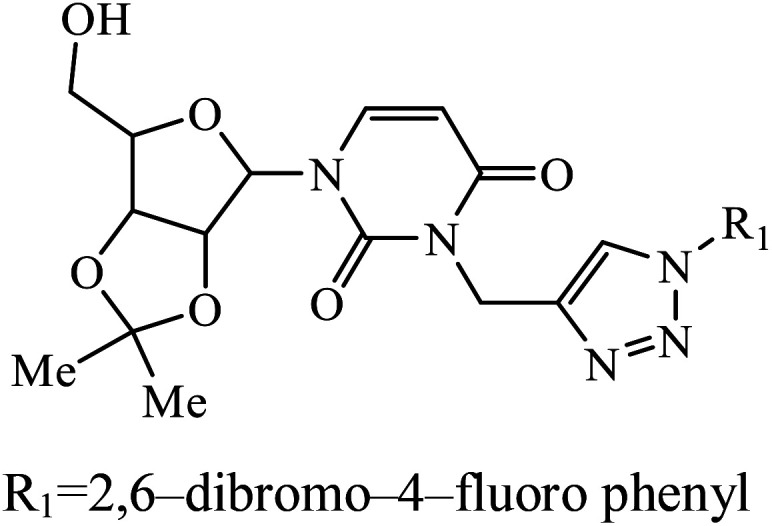

A series of bishomoisoprenoid triazole bisphosphonates were synthesized and were evaluated to have good inhibition of geranyl diphosphate synthase. The activity of these compounds was studied on the basis of chain length and the olefin stereochemistry, and the results prove that compound 31 is the most potent inhibitor against GGDPS.60 A class of novel isopropylidene uridine [1,2,3-triazole] hybrids were found to be highly active as anticancer and antibacterial agents. The results indicated that the compound containing the hydroxyl group on the benzene ring exhibited high activity towards MCF-7 (breast cancer) cancer cell, whereas compound 32 containing 2,6-dibromo group on the benzene ring is an excellent inhibitor of the HeLa cell lines. These results clearly exhibit the high activity in comparison to the standard drug cis-platin.61

The Cu(i) assisted cycloaddition reaction to create 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole resulted in a series of triazoles with anticancer activity against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Hep 3B cells and HT-29. Compound 33 exhibits excellent cytotoxic effect towards the cancer cell lines and on normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells but the effect is comparatively less as compared to standard anticancer agent Sorafenib. The activity of this molecule 33 is still better in a short time period and at low concentration. The activity of compound 33 was induced due to the apoptosis of Hep 3B cells and it did not cause the arrest of the cell cycle at the G0/G1, S, or G2/M phases. The decrease in the percentages of the cells at G0/G1, S, and G2/M may have been due to the increase in the cells at the Sub-G1 phase.62–66

Sayeed et al. designed a new series of imidazopyridine linked triazole hybrid conjugates with robust anticancer inhibition activity with four cancer cell lines, i.e., breast (MDAMB 231) cancer, human prostate (DU-145), human colon (HCT-116), and human lung (A549) cancer. Among all the synthesized molecules, compound 34 shows excellent cytotoxicity against the human lung cancer cell line because of the presence of electron donating trimethoxy group on the aromatic ring. Compound 34 exhibited various interactions with the residues with conventional hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl oxygen and Thr349, nitrogen atom of imidazopyridine ring and Ile332, and nitrogen atom of the triazole ring and Gly350. The oxygen atoms in the methoxy substituents were also involved in hydrogen bonding with the amino acid residues Asp179, Asn329, and Ile341.67

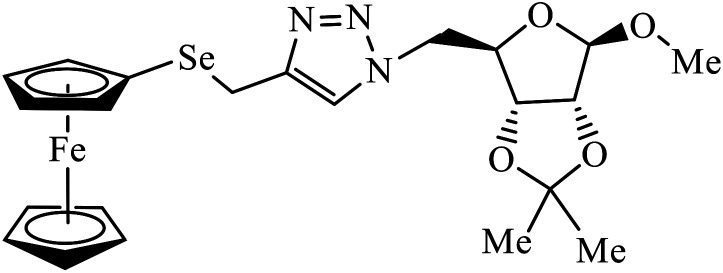

Ferrocenyl chalcogeno (sugar) triazole conjugates also exhibit strong anticancer activity. The evaluation of the activity of these triazoles with different cancer cell lines conclude that the sulphur containing triazole conjugates are cytotoxic towards the cancer cell but with lower activity. Moreover, the compounds containing selenium triazole 35 show very high activity towards the cancer cell lines.68–70

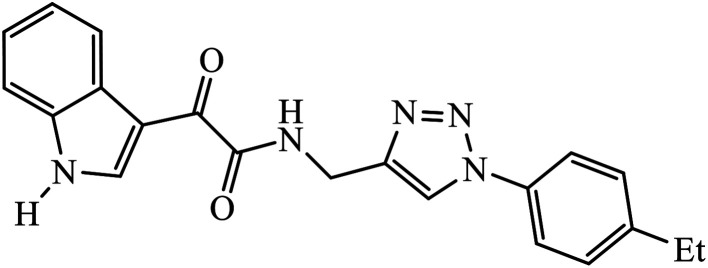

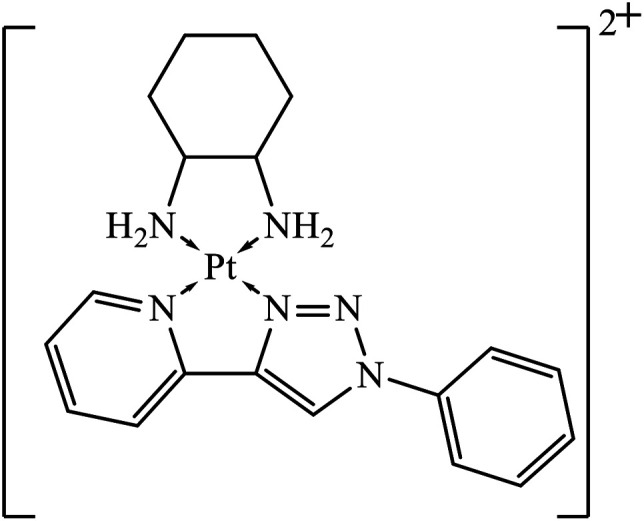

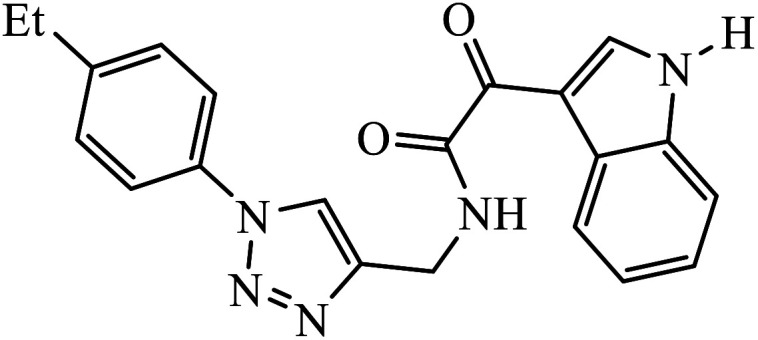

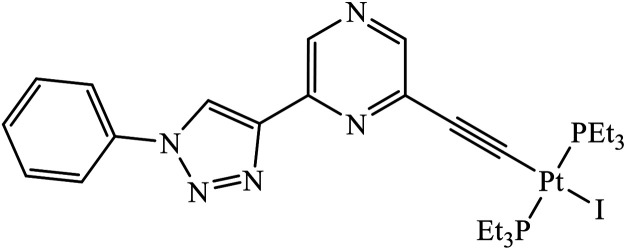

Platinum(ii) complexes incorporating bidentate pyridyl-1,2,3-triazole were synthesized and were highly active against different cancer cell lines. The results specify that compound 36 is an excellent inhibitor of different cancer cell lines as compared to the standard drug cis-platin.71 Two novel series of 1,2,3-triazole tethered to indole-3-glyoxamide derivatives were evaluated for their anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and inhibitory activities against 5LOX, COX-1, and COX-2. The activity of these compounds depends upon the nature and position of the substituent on the phenyl ring. The compounds with ethyl and halogen groups at the para position show excellent activity against proliferative cancer cell lines.72,73

Compound 37 with p-ethyl substituent on the aromatic ring shows very high anti-proliferative activity. It displayed strong binding with Lys352 and Val238 amino acids and was also involved in hydrophobic bonding with Leu255 and Ile354 amino acids. It was found that this compound exhibited a similar kind of interaction as that of nocodazole in the catalytic domain of ATP at the Colchicine binding site of tubulin.74 1,2,3-Triazole derivatives of diosgenin were used as anti-tumor agents with inhibition activity examined on four cancer cell lines, viz., HBL-100 (breast), A549 (lung), HT-29 (colon), and HCT-116 (colon). It was studied that the compounds with simple phenyl moiety attached through 1,2,3-triazole to the parent molecule 38 demonstrate very high activity against the A549 cancer cell line as compared to the positive control (BEZ-235).75 The triazolyl pyrimidine hybrids that act as anticancer agents were tested on four cancer cell lines, viz., EC-109 (human esophageal cancer cell line), MCF-7 (human breast cancer cell line), B16-F10 (mouse melanoma cell line), and MGC-803 (human gastric cancer cell line). The results signify the importance of having electron-donating groups on the aryl amine that exhibits high inhibition activity as compared to the compound having electron-withdrawing groups. The 4-substituted arylamine 39 shows excellent inhibition activity against MCF-7 and MGC-803.76–78 This 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazole act as an anticancer agent and shows excellent activity against glioblastoma cell lines. The examination of anti-cancer activity of these compound at different concentrations and at two different time periods (48 h and 72 h) gives the information that compound 40 having methylenoxy or tosyl-hydrazone attached to 1,2,3-triazole led to an increase in the activity of the compound. Compound 40 indicated large H-bond acceptor peaks directed towards the tosyl and azide groups, suggesting a stronger acceptor region.79

A novel series of 1,2,3-triazole-dithiocarbamate 41 was obtained, which act as anticancer agents against four cancer cell lines as compared to the standard drug 5-fluorouracil because of the presence of electronegative atoms at the ortho-position of the benzyl ring.80 Gregorić et al. synthesized a series of pyrimidine-2,4-dione-1,2,3-triazole and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2-one-1,2,3-triazole as the anticancer agents. Their activity was examined against five cancer cell lines and compound 42 shows better activity against two cancer cell lines, viz., hepatocellular and cervical carcinoma, as compared to the standard drug 5-fluorouracil. The structure of compound 43 indicated the absence of strong hydrogen-bonding donors and was linked only by weak interactions, two C–H⋯O hydrogen bonds, one C–H⋯N hydrogen bond, one C–H⋯π interaction, and one π⋯π interaction.81

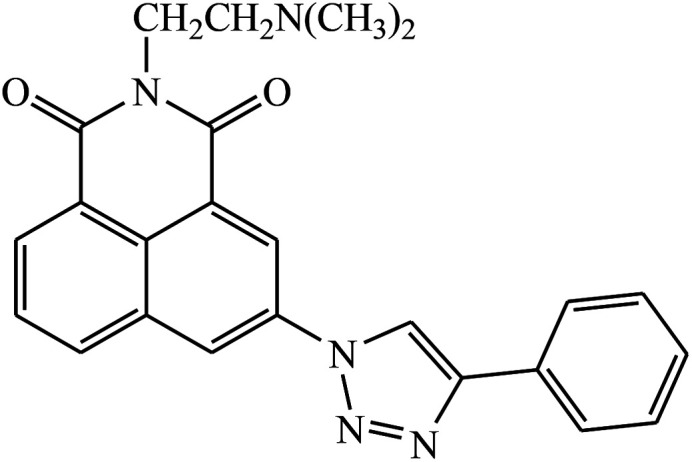

Two new series of 1,2,3-triazole-1,8-naphthalimides 43 were synthesized by click chemistry that act as anticancer agents. It was observed that the activity of these compounds depends on the type of the side chain that is attached to the 1,2,3-triazole moiety. It has also been reported that if the side chain contains terminal basic group, it results in the increase in the activity of the compound against the cancer cell lines. The UV-Vis spectra were used to investigate the interactions between compound 43 and DNA, which represented significant hypochromic and slight bathochromic shifts upon the addition of CT-DNA, suggesting that the transition of energy or electron occurred between the compounds and the base pairs of DNA. The results suggested that the 43–DNA complexes were more stable with the aid of large p-conjugated systems formed by phenyl linked to 1,2,3-triazole moiety of 43.82

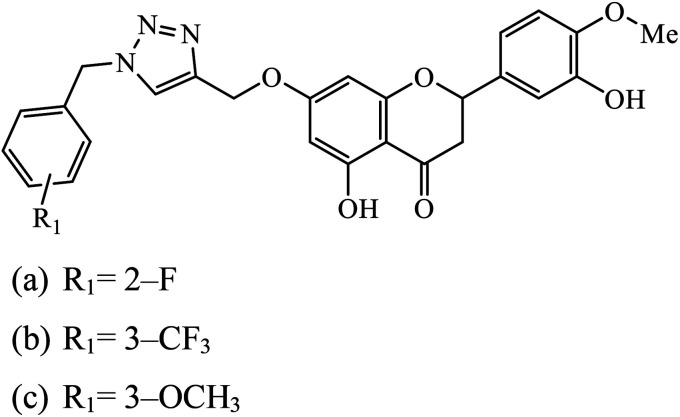

The benzyl-1,2,3-triazolyl linked hesperetin derivatives were synthesized and examined to have anticancer as well as antioxidant activity. The anticancer activity was found against cancer cell lines such as HeLa, CaSki, and SK-OV-3. It was reported that compound 44a, having an electron withdrawing substitution at the ortho and para positions on the phenyl ring, displays good activity against HeLa and compound 44b, having a substitution at the meta position, increases its activity towards SK-OV-3, whereas in the case when molecule 44c has an electron donating group, then its activity towards CaSki is very high.83

The linkage of 1,2,3-triazolyl moiety with salicylamides 45 leads to the design of the anticancer drug acting as an aurora kinase inhibitor. The binding of this inhibitor towards aurora kinase depends on the availability of –OH group on salicylamide, which is directly attached to 1,2,3-triazole. The inhibition activity towards aurora kinase may also be due to the presence of –CO2CH3 group, wherein compound 45 interacts with Lys175, Glu194, and Gln190 through hydrogen bonding. The carbonyl group of the salicylamide scaffold acts as a hydrogen bonding acceptor and forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain N–H of Lys175, whereas the phenolic –OH of the salicylamide scaffold acts as a hydrogen bond donor and makes another hydrogen bond with the carboxylate of Glu194.84

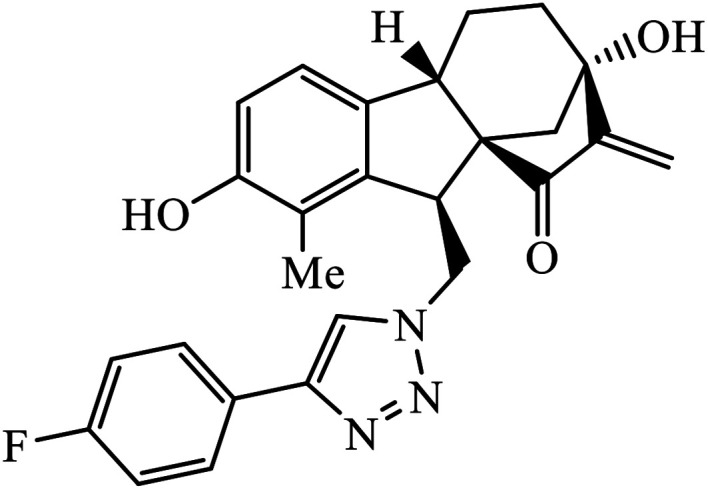

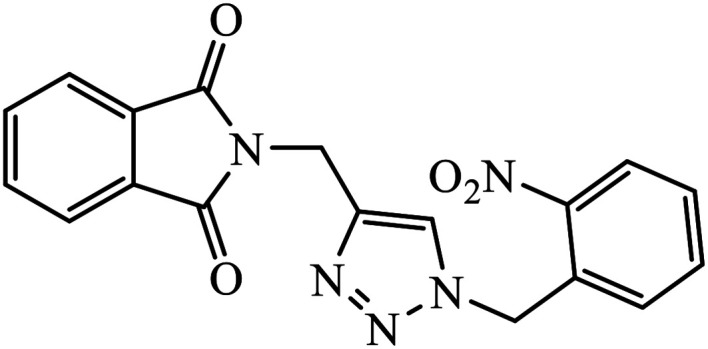

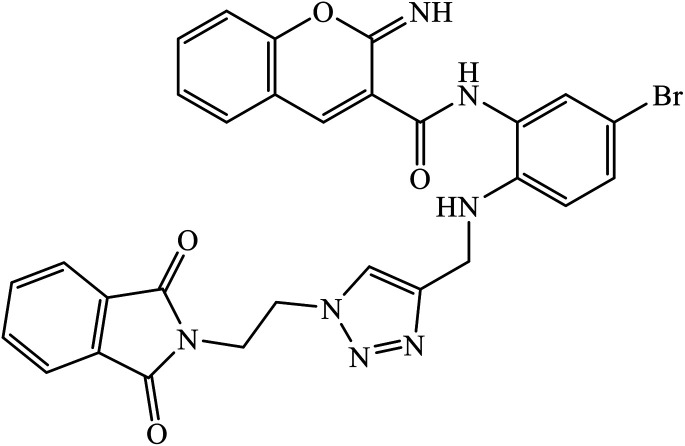

The allogibberic acid derivatives of 1,2,3-triazole pharmacophore were found to have inhibition potential towards five cancer cell lines. From the results of the inhibition value, it was analysed that in the presence of an α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety, compound 46 shows excellent inhibition potential against the cancer cell lines by arresting the S-phase of the cell cycle. Similarly, the phthalimide based 1,2,3-triazole derivatives attached to the substituted benzyl ring 47 were designed and examined for the inhibition activity against tyrosinase.85

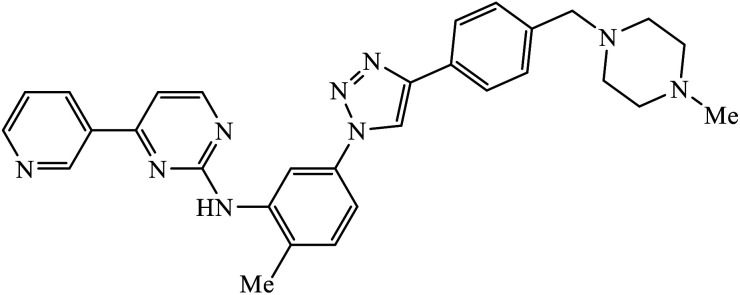

The activity of this compound basically depends upon the atom substituted on the phenyl ring, i.e., if an electron-donating atom is present, then it will decrease the activity of the compound but if an electron-withdrawing atom is present on the phenyl ring, then it will give excellent inhibition activity against tyrosinase. Compound 47 was accommodated in the binding pocket of tyrosinase by hydrogen-bonding and π–H interactions. The oxygen atoms of the NO2 group on the phenyl ring interacted via two strong hydrogen bonds with side chain N–Hs of Arg268 and phthalimide moiety involved in a π–H interaction with Val283.86 Peruzzotti et al. developed N-[2-methyl-5(triazol-1-yl)phenyl]pyrimidin-2-amine derivatives through in situ click chemistry, which inhibit tyrosine kinase. This compound 48 displayed good inhibition activity against Abl kinase (IC50 = 0.9 ± 0.1 μM).87

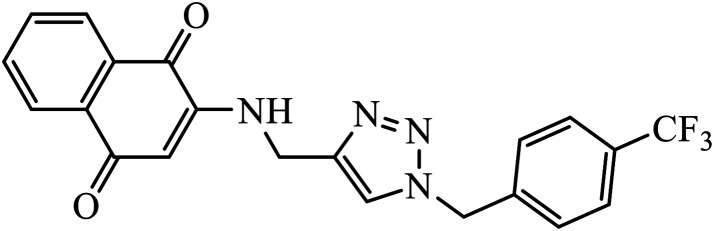

1,4-Naphthoquinone-1,2,3-triazole hybrids were synthesized and evaluated for their anticancer activity against three cancer cell lines including MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma), HT-29 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma), and MOLT-4 (human acute lymphoblastic leukaemia) by MTT assay. Compound 49 with 4-trifluoromethyl-benzyl moiety possessed the highest cytotoxic activity (IC50 = 6.8–10.4 μM) against all the three cancer cell lines, which were comparable to the activity of cisplatin (IC50 = 2.4–19.1 μM) as the positive control. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that compound 49 arrested the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase.88

Compound 50 consisting of three fluoro groups showed excellent anticancer activity against HepG2 cells with IC50 value of 0.0267 μmol mL−1.89 The formation of new organoplatinum complexes with triazole rings was examined for their cytotoxic effects on selected cancer (MG-63 and MDA-MB-231) and normal (HDF) cells, and the results were compared with that of cisplatin. The stats indicate that all the synthesised compounds were at least thrice times more toxic than cisplatin against MG-63, MDA-MB-231, and HDF cell lines, and the compound with highest toxicity was 51.90

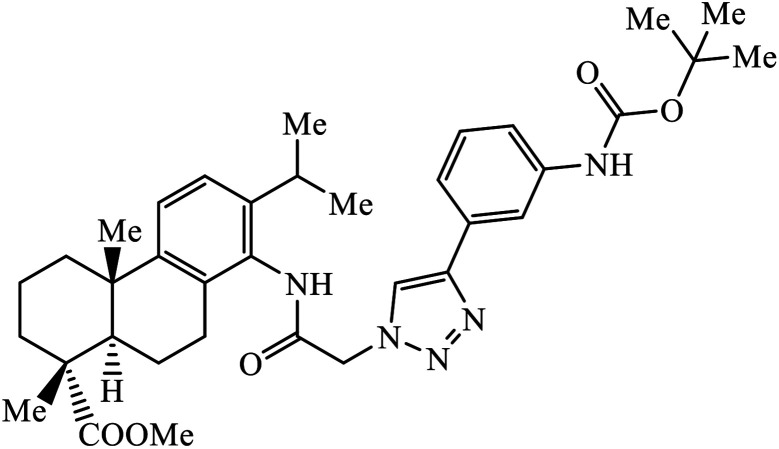

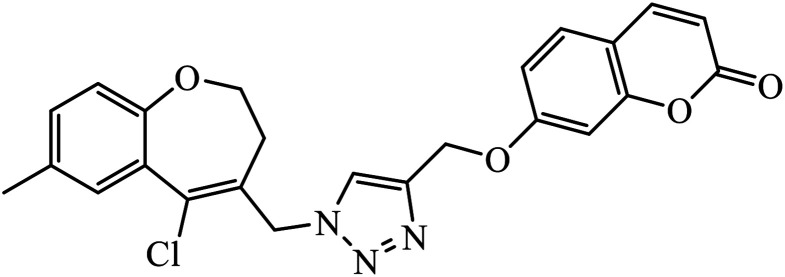

Notably, the additional potentially active compound 52 possessing 3-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)phenyl-substituted triazole moiety not only exhibited obviously improved IC50 values ranging from 0.7 to 1.2 μM against a panel of tested cancer cells but also showed very weak cytotoxicity on normal cells. Preliminary mechanistic studies indicated that compound 52 could induce apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells and was worth developing into a novel natural product-like anticancer agent by proper structural modification.91 Another series of hybrid compounds was synthesized and tested against bacterial strains and cancer cell lines. Some of the benzoxepine-1,2,3-triazole hybrids 53 displayed excellent activity against P. aeruginosa strain in the 18 ± 0.3 zone of inhibition (diameter in mm) at 0.4 mg/50 μL. The activity of these drugs towards cancer cell lines HCT15 and NCI-H226 is notable owing to the presence of a –CH2–O– linkage between the triazole and heteroaryl moieties.92

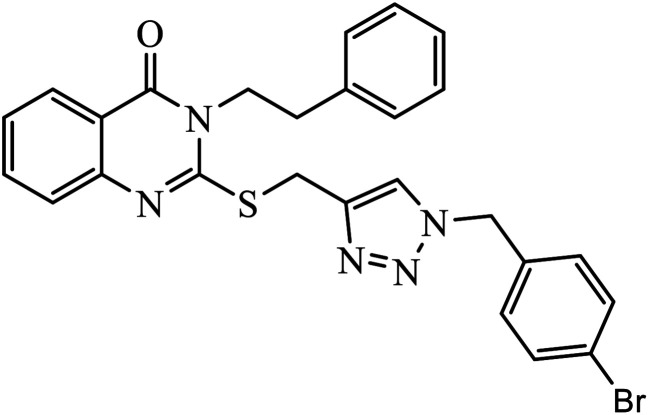

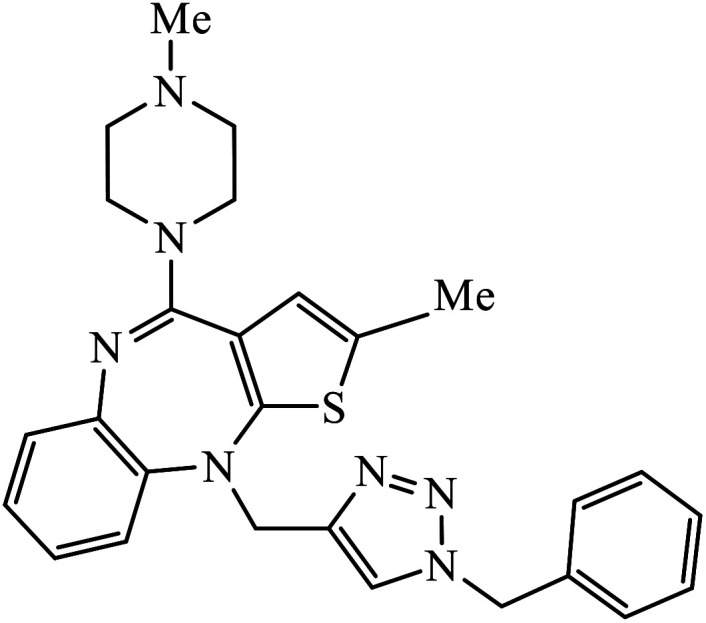

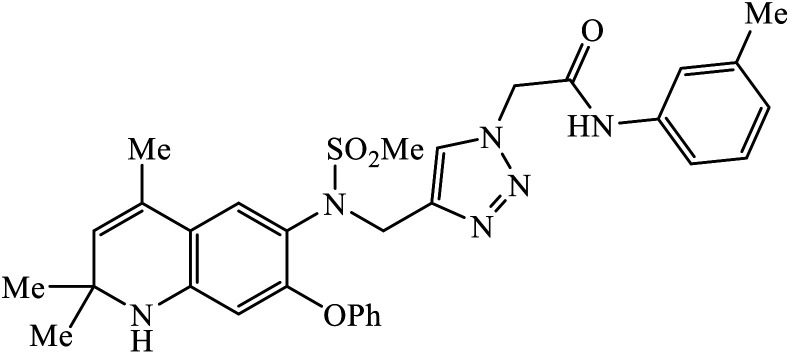

In a unique reaction, for the creation of 1,2,3-triazole derivatives of nimesulide, compounds 54 were designed as potential inhibitors of PDE4B. One of the synthesized compounds was highly effective for PDE4B inhibitory properties with IC50 value of 4.92 ± 0.53 μM. The docking studies revealed that the interaction of PDE4B with Gln443, His234, and His278 also had potent activity towards HCT-15 human colon cancer cells.93 1,2,3-Triazole linked nimesulide hybrids were studied against four cancer cell lines. The presence of –CH2O– moiety in the molecules proved to have better molecular interactions, as indicated by their activities against the cancer cell lines. Moreover, the docking studies of compound 55 indicated that the –NH group of the synthesized compounds formed H-bond with the ASP346 of PDE4B. The most probable reason for inhibitory properties against cancerous cell growth indicated by these compounds against various cancer cell lines could be due to their inhibition of PDE4B.94 Furthermore, the 1,2,3-triazole derivatives of olanzapine 56 are capable of inhibiting PDE4B. The comparative results signify that the compounds having unsubstituted benzene ring attached with 1,2,3-triazole have better inhibition tendency as compared to mono-substituted benzene ring.95 2,2,4-Trimethyl-1,2-dihydroquinolinyl substituted 1,2,3-triazole derivatives 57 were developed and were examined for their PDE4B inhibitor capacity as well as anti-cancer properties. The standard inhibition percentage of PDE4B at 30 μM is 58.2% and also has a notable value of IC50 = 8.7 ± 0.24 towards the A549 cancer cell line.96

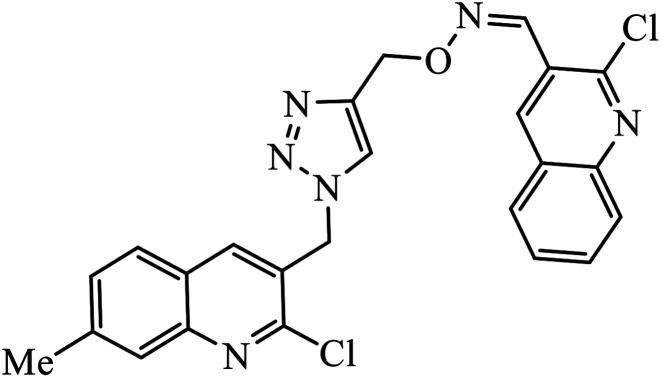

The collaborative effect of quinoline, triazole, and dihydroquinoline in a single pharmacophoric group has the capability of inhibiting PDE4B and some cancer cell lines. Compound 58 is the most active against these two different cancer cell lines A549 and MCF 7. The interactions of nitrogen of the quinoline ring participated in the H-bonding interaction with the Gln443 residue of PDE4B. Additionally, arene–cation and arene–arene interactions were observed with the His234 and Phe446 residue.97 Quinoline, triazole, and oxime ether are coupled and converged into a single molecular entity 59, and these molecules were screened for their inhibitory effects on the growth of four cancer cell lines and on the inhibition of PDE4B. Among all the molecules screened, the compound 59 is highly active against the A549 cancer cell line as compared to the standard drug doxorubicin. The study, supported by molecular docking, depicts that the nitrogen atom of both the quinoline rings formed hydrogen bonds with the conserved residues such as Gln443 of the Q pocket and His 234 of the metal binding pocket in the active site of PDE4B. The conserved π interaction with Phe446 was also observed commonly in all these compounds.98

Anti-viral activity

1,2,3-Triazole linked dihydropyrimidinone hybrid molecules 60 were developed and evaluated for their antiviral activity against VZV, which is the causative agent for chickenpox. Many such compounds with such activities have been compiled in Table 3. It was observed that in the presence of p-nitro group on the benzyl ring, the activity of the molecule increases against the TK + VZV strain. Molecule 60 with N,O-triazole moiety is such that its activity is unaffected by the midine kinase resistance.10

List of 1,2,3-triazolyl compounds possessing anti-viral activity as observed using IC50 and EC50 values.

| Sr. no. | Parent compound | Biological target | Anti-virus | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 |

|

EC50 (μM) | 10 | |

| TK + VZV | 3.62 | |||

| TK − VZV | 7.85 | |||

| 61 |

|

IC50 (nM) | 99 | |

| HIV-1 proteases (wt) | 6 ± 0.5 | |||

| 62 |

|

IC50 (nM) | 102 | |

| HIV-1 proteases (6X) | 15.7 | |||

| 63 |

|

EC50 (μM) | 103 | |

| IIIB | 0.020 | |||

| E138K | 0.014 | |||

| 64 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 104 | |

| HIV-1 NL4–3 | 7.0 ± 0.8 | |||

| 65 |

|

IC50 (μM) | 105 | |

| H9 cells | 0.01 |

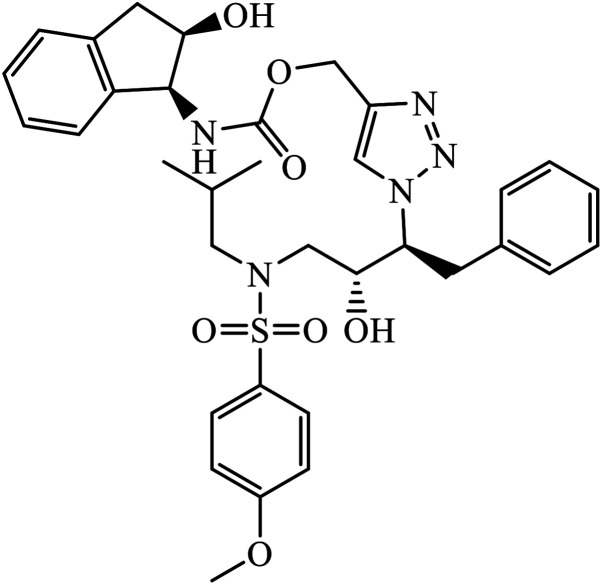

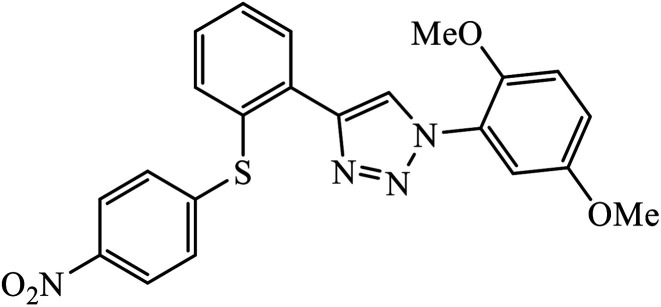

The activity of 1,2,3-triazolyl compounds to act as peptide surrogates, which is used as anti-HIV agent, is largely prominent. Compound 61 has very high activity against wild type and mutant HIV-1 proteases. Interestingly, the crystallographic studies indicate that the position of this inhibitor is similar to that of amprenavir and 1,2,3-triazole is a suitable mock of the peptide group. The comparative study proved that the 1,2,3-triazole is an effective replacement for a peptide group in the HIV-1 protease inhibitors, thus leading to high activity.99–101 Further, these triazolyl compounds 62 too have the potential to act as anti-HIV-1 protease inhibitor, with high activity of this compound against wild type protease [(IC50) 6.0 nm]. Its high activity is due to interaction with selected residues and maintenance of hydrogen bonding to main chain atoms.102

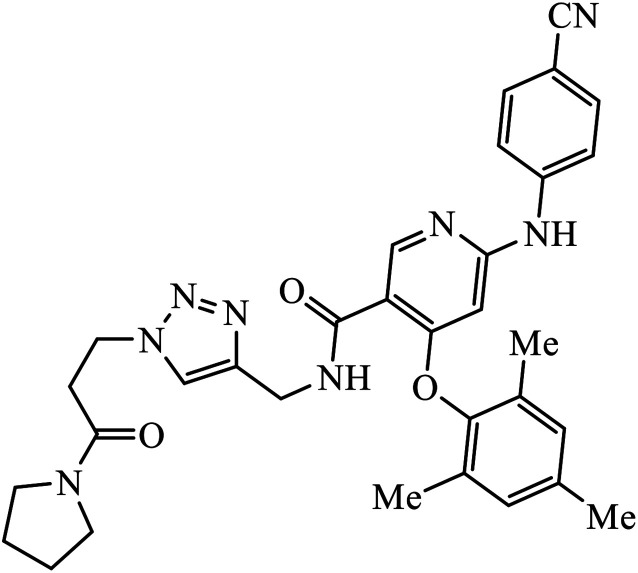

Tian et al. created a library of diarylnicotinamide 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles, which work as good anti-HIV1 agents with activity against wild type HIV-1 and mutant HIV-1 strains in MT-4 cells. The activity of these compounds was tested against many strains including IIIB, K103N + Y181C, L100I, K103N, E138K, Y181C, Y188L, and F227L + V106A. The results indicate that the presence of nitro and cyano group at the 3rd position on benzyl ring 63 increases the activity of the compound against HIV-1, as shown in the molecule.103

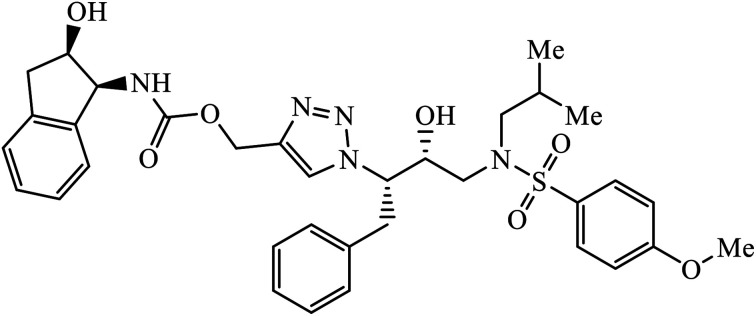

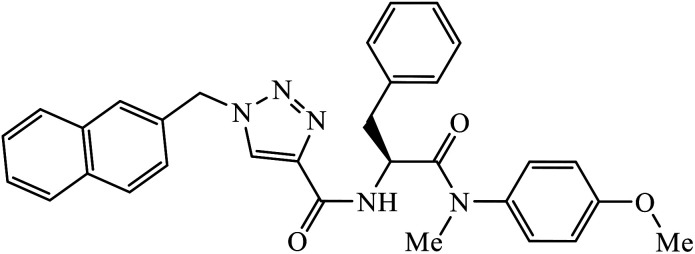

Phenylalanine derivatives that were also synthesized via click chemistry exhibit excellent anti-HIV activity. Compound 64 has very high activity against HIV-1 NL4-3 strain with much lesser toxicity because of the presence of β-substituted naphthalene, which is directly bound to triazole. The results conclude that compound 64 potentially has two different binding modes with the HIV-1 CA monomer, which has implications for the precise manner of CA protein inhibition in each of the discrete stages of replication.104 Furthermore, 1,2,3-triazoles along with amide bioisosteres were also found to be anti-HIV against H9 cells. The activity of these compounds depends upon the different substituent attached to the benzyl ring. Compound 65 has particularly high activity against the H9 cell line because of the presence of methoxy and nitro groups on two different benzyl rings.105

Anti-inflammatory activity

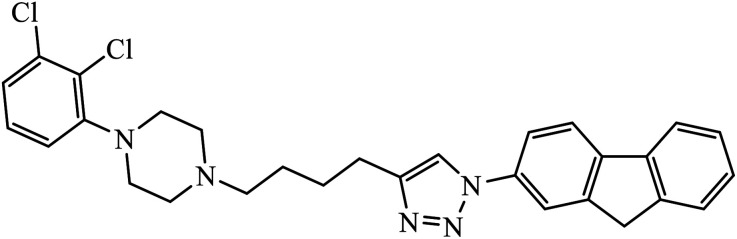

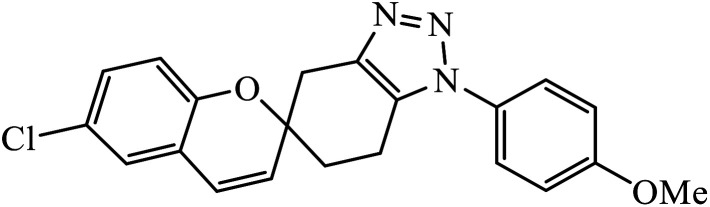

The 1,2,3-triazole conjoined compound of 4-phenylpiperazine produces the target molecule 66 bearing 2,3-dichlorophenyl-containing indolyltriazole group having strong dopamine D3 receptor activity.106–109 Eugenol derivatives bearing 1,2,3-triazole functionalities were used to cure L. amazonensis disease. Compound 67 demonstrates the best activity among the series of derivatives of triazoles synthesized with lower toxicity as compared to the standard drugs pentamidine and glucantime, which is currently used in the treatment of leishmaniasis.110

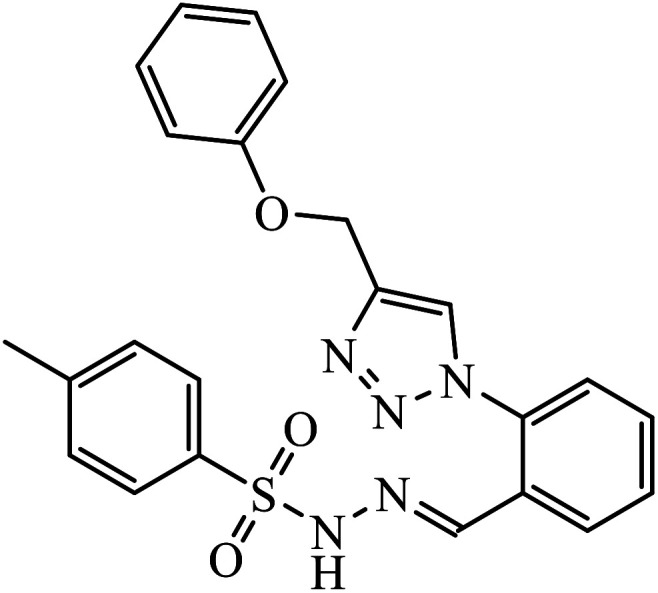

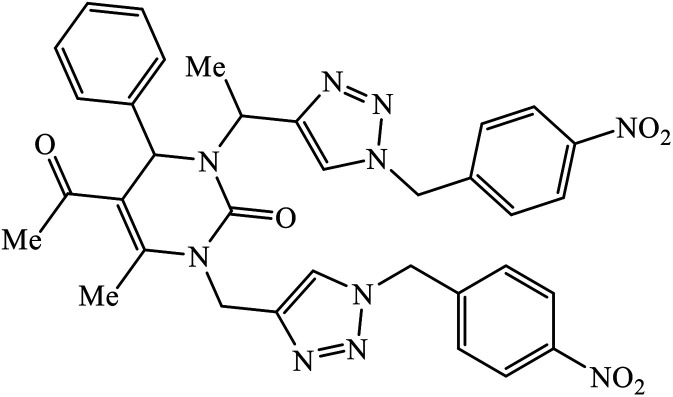

Two novel series of 1,2,3-triazole tethered to indole-3-glyoxamide derivative were evaluated for their inhibition as anti-inflammatory agents. The activity of compound 68 depends on the nature and position of the substituent on the benzene ring, i.e., the substitution at the para position of the phenyl ring gives good anti-inflammatory activity whereas the p-ethyl substituent on the aromatic ring exhibits very high anti-inflammatory activity,74 and are compiled in Table 4.

List of 1,2,3-triazolyl pharmacophore possessing anti-inflammatory activity as observed using IC50 and Ki ± SEM values.

Anti-diabetic activity

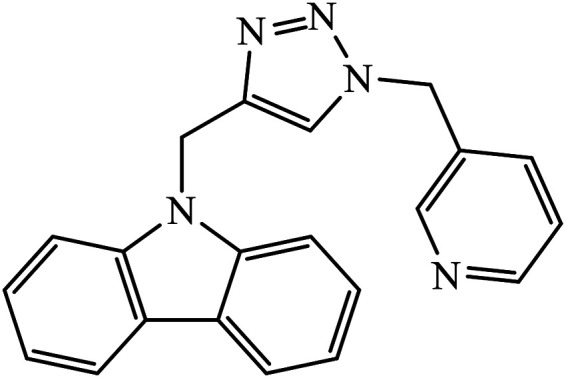

Iqbal et al. synthesized new carbazole linked 1,2,3-triazole that acts as an inhibitor against α-glucosidase. The results indicate that most of these compounds show better inhibition activity against α-glucosidase as compared to the standard drug acarbose, whereas some of them do not show activity due to the presence of methyl group. In fact, compound 69 is highly active due to the presence of the N-hetero atom in the pyridine ring.111,112

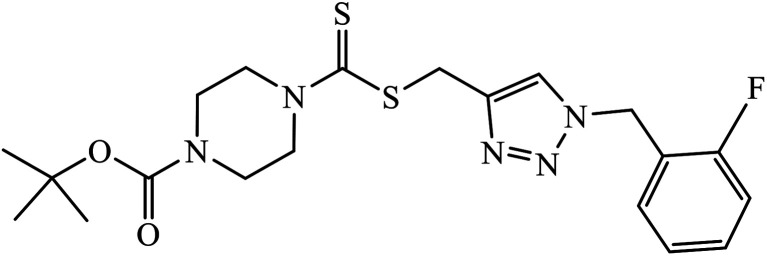

The quinazolinone based 1,2,3-triazole acts as an anti-diabetic agent with inhibition activity against α-glucosidase. The synthesized compounds show excellent activity as compared to the standard drug that is acarbose, as shown in Table 5. One of the compounds having 4-bromobenzyl 70 represents the highest activity due to hooking of bromine at ortho position on benzyl group. It was observed that upon replacement of bromine with fluorine or chlorine group, the activity of the compound decreases drastically. The activity of compound 70 was due to the interaction with His279, Pro309, Arg312, Val305, and Val316 residues. The quinazolinone moiety interacted via hydrogen bonding and π–π interaction with His279. The phenyl-ethyl group and the sulphur of compound 70 interacted with Arg312 and a hydrophobic interaction between Pro309 and the 1,2,3-triazole ring was observed. Moreover, the 4-bromobenzyl group also interacted with Val305 and Val316 through the 4-bromo substituent and hydrophobic interaction with Pro309 through the phenyl ring.113

List of 1,2,3-triazolyl pharmacophore molecules possessing anti-diabetic activity as observed using IC50 values.

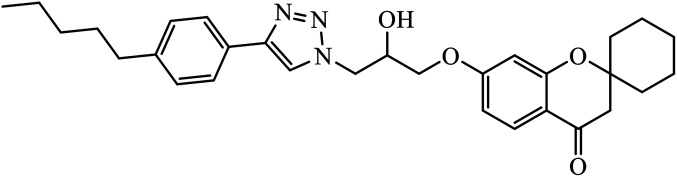

Xanthone-triazole derivatives were investigated for their α-glucosidase inhibitory activities and compound 71 was observed to have the highest inhibition activity, with IC50 value of 2.06 μM. The interactions between compound 71 and the allosteric sites of the enzyme were studied by molecular docking, which reveal that the increase in the activities is an outcome of hydrogen bonding and π–π or π–cation interaction of the aromatic ring substituted triazole moiety with the enzyme. In addition, molecule 71 promotes glucose uptake.114

Berberine derivatives were designed and evaluated for their activity against HepG2 cell lines. It was observed that compound 72 mannose (berberine derivative) produces the best activity with an IC50 (μg mL−1) value of 72.19, which is approximately 1.5-fold of that of berberine and mannose.115

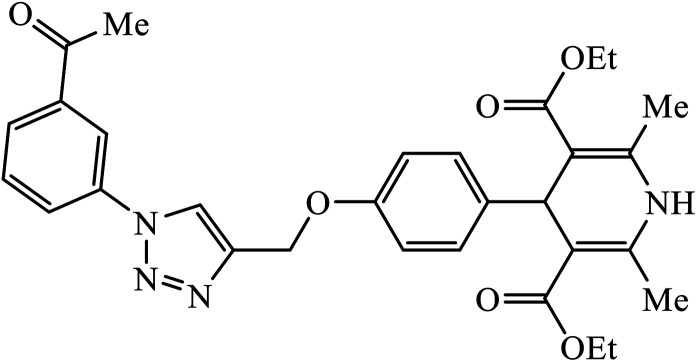

1,4-Dihydropyridine derivatives, upon synthesis, were evaluated for their anti-diabetic activity. The study with 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 proves that molecule 73 adopts L-shaped conformation while binding to 11β-HSD1. This was a result of the development of CH–π interaction with the Phe-300 residue. Also, compound 73 developed anion–π interactions with Glu-276 and Asp-349 residues.116

Anti-Alzheimer activity

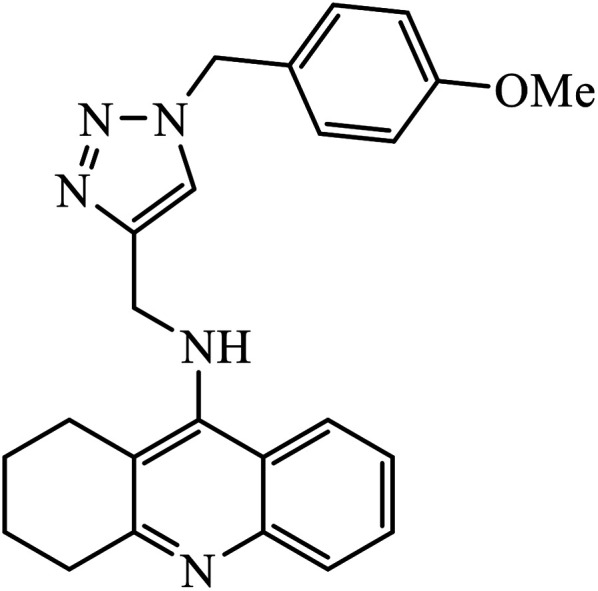

1,2,3-Triazole-linked reduced amide isosteres were analysed for their anti-Alzheimer BACE1 inhibitor activity, as given in Table 6. Some of these amide isosteres were found to have very high activity, as measured by their IC50 values. Compounds 74 have large activities as BACE1 inhibitors.117,118 Another class of novel tacrine-1,2,3-triazole hybrids acted as cholinesterase inhibitors as most of these compounds exhibit good inhibition activities towards acetyl cholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). Compound 75 with methoxy group has very high activity against AChE and if this methoxy group is replaced by methyl, fluorine, chlorine, and hydrogen, then the activity decreases against AChE; unsubstituted acridine displayed the maximum activity against BChE.119

List of some of the 1,2,3-triazole linked pharmacophore molecules possessing anti-Alzheimer's activity as observed using IC50 values.

| Sr. no. | Parent compound | Biological target | IC50 (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 74 |

|

BACE1 | 2.0 | 117 |

| 75 |

|

AChE | 2.000 ± 0.030 | 119 |

| BChE | 1.55 ± 0.012 | |||

| 76 |

|

Aβ42 aggregation | 8.065 ± 0.129 | 120 |

| 77 |

|

BACE1 | 2.2 | 121 |

| 78 |

|

Acetylcholinesterase | 1.80 | 122 |

| 79 |

|

(a) | 123 | |

| AChEI | 0.027 ± 0.009 | |||

| BChEI | 0.104 ± 0.018 | |||

| (b) | ||||

| AChEI | 0.095 ± 0.014 | |||

| BChEI | 0.006 ± 0.002 | |||

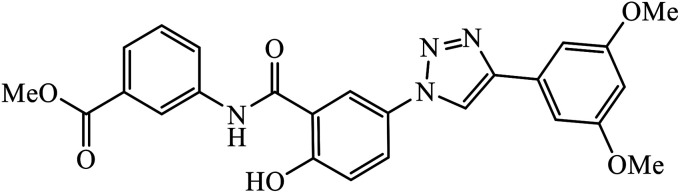

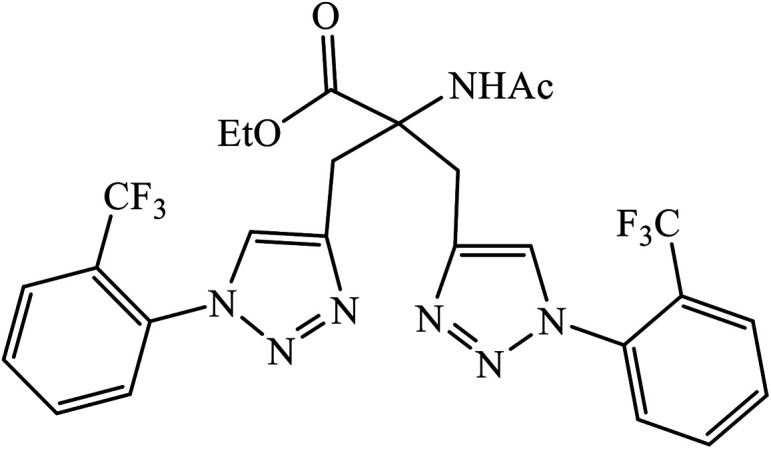

Triazole-based compounds were evaluated as multi-target-directed ligands against Alzheimer's disease that included Aβ aggregation, metal-induced Aβ aggregation, metal dys-homeostasis, and oxidative stress. The synthetic compounds 76 have o-CF3 group on the phenyl ring with the most potent inhibitory activity (96.89% inhibition, IC50 = 8.065 ± 0.129 μM) against Aβ42 aggregation, compared to the reference compound curcumin (95.14% inhibition, IC50 = 6.385 ± 0.009 μM). The formation of amyloid fibrils was significantly reduced in the presence of drug 76, which highlights the inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation. In addition, molecular docking studies highlighted that molecule 76 binds preferably to the C-terminus region of Aβ42 by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts.120

Multifunctional iminochromene-2H-carboxamide derivatives containing different aminomethylene triazole having potential of BACE1 inhibition, and neuroprotective and metal chelating properties that target Alzheimer's disease. Derivative 77 was found to have IC50 value of 2.2 μM against BACE1 and was supported by the molecular docking studies, with two residues of the binding site Asp32 and Asp228 being involved in the hydrogen bonding interactions with the amino methylene triazole linker and amide linker, respectively. The additional hydrogen bonding interaction with Gly230 as the second important amino acid was observed through the amide linker. π–π stacking interaction was also observed in between Tyr71 and the bromophenyl ring. The phthalimide moiety establishes favourable π–π stacking interaction with the side chain of Thr76.121

1,2,3-Triazole supported chromenone carboxamides were evaluated for their cholinesterase inhibitory activity, with compound 78 being the best for acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity (IC50 = 1.80 μM) in comparison to donepezil as the reference drug (IC50 = 0.027 μM).122 The tacrine-coumarin structured hybrids linked to 1,2,3-triazole proved to be potential dual binding sites of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Among all these, compound 79a was the most potent anti-AChE derivative (IC50 = 27 nM) and compound 79b displayed the best anti-BChE activity (IC50 = 6 nM), which is much more active than tacrine and donepezil as the reference drugs.123

Anti-oxidant property

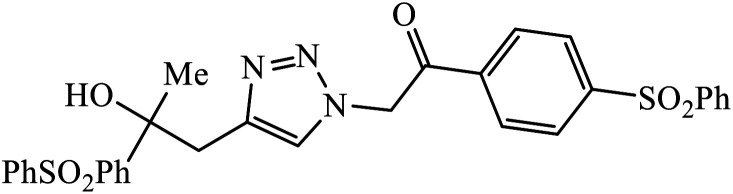

The symmetrically 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-bistriazole derivatives were examined to possess anti-oxidant (AChE inhibition, DPPH, and SOD) activity. This property is based upon the number of carbon atoms present in the chain, which combines with the two 1,2,3-triazole moieties. Compounds 80a, 80b, and 80c show excellent activity against AChE, DPPH, and SOD.124 Another class of compounds with similar disubstituted derivatives displayed good antioxidant activity against DPPH as compared to the standard drug ascorbic acid. Compound 81 is the most active due to the presence of NO2 group in the compound.125 The diaryl sulfone moiety coupled triazoles were designed and evaluated for their potential as anti-oxidants. Molecule 82 was the strongest radical scavenger owing to the presence of diaryl sulfone moiety, which increased its anti-oxidant activity,126 as provided in Table 7.

List of 1,2,3-triazole linked pharmacophore molecules possessing potent anti-oxidant activity.

Conclusion and challenges

Click chemistry has been developed as an effective technique for the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles that have the potential to act as anti-microbial, anti-cancer, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-Alzheimer, and anti-oxidant drugs. In most of the synthesized compounds, the presence of electron withdrawing groups increases the activity whereas the presence of electron donating group shows the reverse affect. The generation of low-cost compounds with high purity can significantly boost the pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry efforts towards new drug discovery and development. The detailed pharmacological and pharmacokinetic studies of 1,2,3-triazolyl compounds still appeared to be an under-explored area. The efforts towards these directions may enhance the value and significance of 1,2,3-triazolyl compounds in various drug discovery programs.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

List of abbreviations

- 5LOX

5-Lipoxygenase

- A. brasiliensis

Aspergillus brasiliensis

- A. niger

Aspergillus niger

- A549

Adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial cells

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- B. subtilis

Bacillus subtilis

- B. cereus

Bacillus cereus

- B16-F10

Mouse melanoma cell line

- BACE1

β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- BEZ-235

Dactolisib

- C. albicans

Candida albicans

- C6

Rat glioma cell lines

- CaSki

Cervical cancer cell line

- COX-1

Cyclooxygenase-1

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- DPPH

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- DU-145

Human prostate cancer cell line

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- E. faecalis

Enterococcus faecalis

- EC-109

Human esophageal cancer cell line

- F. gramillarium

Fusarium gramillarium

- F. oxysporum

Fusarium oxysporum

- F. recini

Fusarium recini

- GBM

Glioblastoma multiforme

- GGDPS

Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase

- GTL-16

Human gastric carcinoma cell line

- H9

Non-permissive

- HBL-100

Breast cancer cell line

- HCT-116

Human colon tumor cell line 116

- HCT-15

Colon cancer cell line

- HeLa

Henrietta Lacks (cervical cancer cell line)

- Hep 3B cells

Hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- Hep-G2

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HL-60

Human leukemia cell line 60 (myeloid leukemia)

- HT-29

Human colorectal cancer cells

- K. pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- L. amazonensis

Leishmania amazonensis

- L. donovani

Leishmania donovani

- M. catarrhalis

Moraxella catarrhalis

- MCF-7

Michigan cancer foundation-7 cell line (breast cancer)

- MDA-MB 231

M. D. Anderson-metastasis breast cancer

- MDCK

Madin–Darby canine kidney

- MDR

Multi-drug resistant

- MGC-803

Human gastric cancer cell line

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentrations

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- NCI-H226

Lung cancer cell line

- P. aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- P. falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum

- P. putida

Pseudomonas putida

- P. vulgaris

Proteus vulgaris

- PC-3

Human prostate cancer cell line

- PDE4B

Phosphodiesterase 4B

- S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus

- S. dysenteriae

Shigella dysenteriae

- S. epidermidis

Staphylococcus epidermidis

- S. epidermidis

Staphylococcus epidermidis

- S. typhi

Salmonella typhi

- S. pyogenus

Staphylococcus pyogenus

- SK-OV-3

Ovarian cancer cell line

- SMMC-7721

Human liver carcinoma

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- SW480

Human colon carcinoma

- TB

Tuberculosis

- TK

Thymidine kinase

- U87

Human glioma cell lines

- VZV

Varicella-zoster virus

Supplementary Material

References

- El Syed Aly M. R. Saad H. A. Mohamed M. A. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:2824–2830. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheer D. Singh V. Shankar R. Bioorg. Chem. 2017;71:30–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumurugan P. Matosiuk D. Jozwiak K. Chem. Rev. 2013:4905–4979. doi: 10.1021/cr200409f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C. Sharpless K. B. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8:1128–1137. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C. Finn M. G. Sharpless K. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appukkuttan P. Dehaen W. Fokin V. V. Van Der Eycken E. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4223–4225. doi: 10.1021/ol048341v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2018;17:97–113. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avula S. K. Khan A. Rehman N. U. Anwar M. U. Al-abri Z. Wadood A. Riaz M. Csuk R. Al-harrasi A. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;81:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Peng Z. Wang J. Li J. Li X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:5719–5723. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaoukabi H. Kabri Y. Curti C. Taourirte M. Rodriguez-Ubis J. C. Snoeck R. Andrei G. Vanelle P. Lazrek H. B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;155:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonandi E. Christodoulou M. S. Fumagalli G. Perdicchia D. Rastelli G. Passarella D. Drug Discovery Today. 2017;22:1572–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu P. V. Mukherjee S. Gorja D. R. Yellanki S. Medisetti R. Kulkarni P. Mukkanti K. Pal M. RSC Adv. 2014;4:4878–4882. doi: 10.1039/C3RA46185H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. Xu Z. Gao C. Ren Q. C. Chang L. Lv Z. S. Feng L. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;138:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. D. Adhikari A. V. Shetty N. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:3803–3810. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok D. Chiranjeevi P. Kumar A. V. Sarasija M. Krishna V. S. Sriram D. Balasubramanian S. RSC Adv. 2018;8:16997–17007. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03197E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. Mao T. Huang J. Zhu Q. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:1305–1308. doi: 10.1039/C6CC08543A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongamanti A. Aamate V. K. Devulapally M. G. Gundu S. Kotni M. K. Manga V. Balasubramanian S. Ernala P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal K. Yadav P. Kumar A. Kumar A. Paul A. K. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;77:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. H. Hung C. F. Yang S. C. Wang J. P. Won S. J. Lin C. N. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:7270–7276. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmadi N. R. Bingi C. Kotapalli S. S. Ummanni R. Nanubolu J. B. Atmakur K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:2918–2922. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav P. Lal K. Kumar L. Kumar A. Kumar A. Paul A. K. Kumar R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;155:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. Bimal D. Bohra K. Singh B. Ponnan P. Jain R. Varma-Basil M. Maity J. Thirumal M. Prasad A. K. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;150:268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Li Z. Zhou M. Wu F. Hou X. Luo H. Liu H. Han X. Yan G. Ding Z. Li R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. Singh J. Singh A. Singh J. Kumar M. Gupta K. Chhibber S. J. Organomet. Chem. 2018;871:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakly R. Edziri H. Askri M. Knorr M. Strohmann C. Mastouri M. C. R. Chim. 2018;21:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2017.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negi B. Kumar D. Kumbukgolla W. Jayaweera S. Ponnan P. Singh R. Agarwal S. Rawat D. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;115:426e–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maračić S. Kraljević T. G. Paljetak H. Č. Perić M. Matijašić M. Verbanac D. Cetina M. Raić-Malić S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:7448–7463. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill C. Jadhav G. Shaikh M. Kale R. Ghawalkar A. Nagargoje D. Shiradkar M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008;18:6244–6247. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angajala K. K. Vianala S. Macha R. Raghavender M. Thupurani M. K. Pathi P. J. Springerplus. 2016;5:423. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey N. Sharma M. C. Kumar A. Sharma P. Med. Chem. Res. 2015;24:2717–2731. doi: 10.1007/s00044-015-1329-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiva Raju K. AnkiReddy S. Sabitha G. Siva Krishna V. Sriram D. Bharathi Reddy K. Rao Sagurthi S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P. V. B. Kamala Prasad V. Manjunath G. Venkata Ramana P. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2016;74:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kategaonkar A. H. Shinde P. V. Kategaonkar A. H. Pasale S. K. Shingate B. B. Shingare M. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:3142–3146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishnan M. Mujahid M. Yogeeswari P. Sriram D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2387–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.02.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatadi S. Gour J. Shukla M. Kaul G. Das S. Dasgupta A. Malasala S. Borra R. S. Madhavi Y. V. Chopra S. Nanduri S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;157:1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Głowacka I. E. Grzonkowski P. Lisiecki P. Kalinowski Ł. Piotrowska D. G. Arch. Pharm. 2019;352:1–14. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. L. Wan K. Zhou C. H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:4631–4639. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G. R. Brandão G. C. Arantes L. M. De Oliveira H. A. De Paula R. C. Do Nascimento M. F. A. Dos Santos F. M. Da Rocha R. K. Lopes J. C. D. De Oliveira A. B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;73:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garudachari B. Isloor A. M. Satyanarayana M. N. Fun H. K. Hegde G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;74:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta E. O. J. Carvalho P. B. Avery M. A. Tekwani B. L. Labadie G. R. Steroids. 2014;79:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khedar P. Pericherla K. Singh R. P. Jha P. N. Kumar A. Med. Chem. Res. 2015;24:3117–3126. doi: 10.1007/s00044-015-1361-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A. Naik R. J. Revankar H. M. Kulkarni M. V. Dixit S. R. Joshi S. D. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;105:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D. Beena Khare G. Kidwai S. Tyagi A. K. Singh R. Rawat D. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;81:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Zhou C. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:956–960. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhaldi A. A. M. Abdelgawad M. A. Youssif B. G. M. El-Gendy A. O. De Koning H. P. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2019;18:1101–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Marepu N. Yeturu S. Pal M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:3302–3306. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Rojas P. Janeczko M. Kubiński K. Amesty Á. Masłyk M. Estévez-Braun A. Molecules. 2018;23:1–18. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeraja P. Srinivas S. Mukkanti K. Dubey P. K. Pal S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:5212–5217. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareddy J. Praveena K. S. S. Suresh N. Jayashree A. Roy S. Rambabu D. Murthy N. Y. S. Pal S. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2013;10:343–352. doi: 10.2174/1570180811310040008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntala N. Telu J. R. Banothu V. Balasubramanian S. Anireddy J. S. Pal S. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2018;18:803–809. doi: 10.2174/1389557517666170717123741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza-fagundes E. M. Delp J. Prazeres P. D. M. Marques B. Maria A. Carmo L. Henrique P. Stroppa F. Glanzmann N. Kisitu J. Szamosvàri D. Böttcher T. Leist M. David A. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018;291:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allam M. Bhavani A. K. D. Mudiraj A. Ranjan N. Thippana M. Babu P. P. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;156:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandeel M. M. Mohamed L. W. Abd El Hamid M. K. Negmeldin A. T. Sci. Pharm. 2012;80:531–545. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1204-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning B. D. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:1–3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.262tr1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holla B. S. Mahalinga M. Karthikeyan M. S. Akberali P. M. Shetty N. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:2040–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo F. Tintori C. Furlan A. Borrelli S. Christodoulou M. S. Dono R. Maina F. Botta M. Amat M. Bosch J. Passarella D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4693–4696. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arioli F. Borrelli S. Colombo F. Falchi F. Filippi I. Crespan E. Naldini A. Scalia G. Silvani A. Maga G. Carraro F. Botta M. Passarella D. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:2009–2018. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agalave S. G. Maujan S. R. Pore V. S. Chem.–Asian J. 2011;6:2696–2718. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysina E. D. Bokor É. Alexacou K. M. Charavgi M. D. Oikonomakos G. N. Zographos S. E. Leonidas D. D. Oikonomakos N. G. Somsák L. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wills V. S. Metzger J. I. Allen C. Varney M. L. Wiemer D. F. Holstein S. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017;25:2437–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatipamula R. K. Narsimha S. Battula K. Rajendra Chary V. Mamidala E. Vasudeva Reddy N. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017;21:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2015.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su C. L. Tseng C. L. Ramesh C. Liu H. S. Huang C. Y. F. Yao C. F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;132:90–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh K. Guan Z. Chem. Commun. 2006:3069–3071. doi: 10.1039/B606185K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Maarseveen J. H. Horne W. S. Ghadiri M. R. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4503–4506. doi: 10.1021/ol0518028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting M. Muldoon J. Lin Y. C. Silverman S. M. Lindstrom W. Olson A. J. Kolb H. C. Finn M. G. Sharpless K. B. Elder J. H. Fokin V. V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:1435–1439. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahsanullah Schmieder P. Kühne R. Rademann J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5042–5045. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed I. B. Vishnuvardhan M. V. P. S. Nagarajan A. Kantevari S. Kamal A. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;80:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaka S. Trivedi R. Jaipal K. Giribabu L. Sujitha P. Kumar C. G. Sridhar B. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016;813:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira S. Sodero A. C. R. Cardoso M. F. C. Lima E. S. Kaiser C. R. Silva F. P. Ferreira V. F. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2364–2375. doi: 10.1021/jm901265h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. J. Mandal K. Harris P. W. R. Brimble M. A. Kent S. B. H. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5270–5273. doi: 10.1021/ol902131n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages B. J. Sakoff J. Gilbert J. Zhang Y. Li F. Preston D. Crowley J. D. Aldrich-Wright J. R. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016;165:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. Langille G. Gill R. K. Li C. M. J. Mikata Y. Wong M. Q. Yapp D. T. Storr T. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2013;18:831–844. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-1023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand H. C. Clède S. Guillot R. Lambert F. Policar C. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:6204–6223. doi: 10.1021/ic5007007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naaz F. Preeti Pallavi M. C. Shafi S. Mulakayala N. Yar M. S. Kumar H. M. S. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;81:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood-ur-Rahman Mohammad Y. Fazili K. M. Bhat K. A. Ara T. Steroids. 2017;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. Y. Wang B. Pang L. P. Zhang M. Wang S. Q. Zheng Y. C. Shao K. P. Xue D. Q. Liu H. M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1124–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patpi S. R. Pulipati L. Yogeeswari P. Sriram D. Jain N. Sridhar B. Murthy R. Anjana Devi T. Kalivendi S. V. Kantevari S. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:3911–3922. doi: 10.1021/jm300125e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y. C. Zheng Y. C. Li X. C. Wang M. M. Ye X. W. Guan Y. Y. Liu G. Z. Zheng J. X. Liu H. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;64:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva V. D. de Faria B. M. Colombo E. Ascari L. Freitas G. P. A. Flores L. S. Cordeiro Y. Romão L. Buarque C. D. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;83:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y. C. Ma Y. C. Zhang E. Shi X. J. Wang M. M. Ye X. W. Liu H. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;62:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorić T. Sedić M. Grbčić P. Tomljenović Paravić A. Kraljević Pavelić S. Cetina M. Vianello R. Raić-Malić S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;125:1247–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Lin Y. Yuan Y. Liu K. Qian X. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:2299–2304. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.01.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry B. Patel R. V. Keum Y. S. Arabian J. Chem. 2017;10:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song D. Park Y. Yoon J. Aman W. Hah J. M. Ryu J. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:4855–4866. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. J. Wu D. M. Chen J. B. Zhao J. F. Gong L. Gong Y. X. Li Y. Yang X. D. Zhang H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:2543–2549. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani M. B. Emani P. Rezaei Z. Khoshneviszadeh M. Ebrahimi M. Edraki N. Mahdavi M. Larijani B. Ranjbar S. Foroumadi A. Khoshneviszadeh M. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1176:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzotti C. Borrelli S. Ventura M. Pantano R. Fumagalli G. Christodoulou M. S. Monticelli D. Luzzani M. Fallacara A. L. Tintori C. Botta M. Passarella D. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:274–277. doi: 10.1021/ml300394w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholampour M. Ranjbar S. Edraki N. Mohabbati M. Firuzi O. Khoshneviszadeh M. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;88:102967. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J. Ran J. X. Chen X. P. Wang Z. H. Wu F. H. Tetrahedron. 2018;74:6985–6992. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2018.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K. Gangrade A. Jana A. Mandal B. B. Das N. ACS Omega. 2019;4:835–841. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b02849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W. Luo Z. Zhang G. Cao D. Li D. Ruan H. Ruan B. H. Su L. Xu H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;138:1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntala N. Telu J. R. Banothu V. Babu N. S. Anireddy J. S. Pal S. Med. Chem. Commun. 2015;6:1612–1619. doi: 10.1039/C5MD00224A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mareddy J. Nallapati S. B. Anireddy J. Devi Y. P. Mangamoori L. N. Kapavarapu R. Pal S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:6721–6727. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareddy J. Suresh N. Kumar C. G. Kapavarapu R. Jayasree A. Pal S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapati S. B. Sreenivas B. Y. Bankala R. Parsa K. V. L. Sripelly S. Mukkanti K. Pal M. RSC Adv. 2015;5:94623–94628. doi: 10.1039/C5RA20380E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Praveena K. S. S. Durgadas S. Suresh Babu N. Akkenapally S. Ganesh Kumar C. Deora G. S. Murthy N. Y. S. Mukkanti K. Pal S. Bioorg. Chem. 2014;53:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praveena K. S. S. Shivaji Ramarao E. V. V. Murthy N. Y. S. Akkenapally S. Ganesh Kumar C. Kapavarapu R. Pal S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praveena K. S. S. Ramarao E. V. V. S. Poornachandra Y. Kumar C. G. Babu N. S. Murthy N. Y. S. Pal S. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2016;13:210–219. doi: 10.2174/1570180812999150819095308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brik A. Alexandratos J. Lin Y. C. Elder J. H. Olson A. J. Wlodawer A. Goodsell D. S. Wong C. H. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1167–1169. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brik A. Muldoon J. Lin Y. C. Elder J. H. Goodsell D. S. Olson A. J. Fokin V. V. Sharpless K. B. Wong C. H. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:1246–1248. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne W. S. Yadav M. K. Stout C. D. Ghadiri M. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15366–15367. doi: 10.1021/ja0450408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giffin M. J. Heaslet H. Brik A. Lin Y. Cauvi G. Mcree D. E. Elder J. H. Stout C. D. Torbett B. E. J. Med. Chem. 2008:6263–6270. doi: 10.1021/jm800149m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. Liu Z. Liu J. Huang B. Kang D. Zhang H. De Clercq E. Daelemans D. Pannecouque C. Lee K. H. Chen C. H. Zhan P. Liu X. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;151:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]