Abstract

Previous studies of the antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus milleri group organisms have distinguished among species by using phenotypic techniques. Using 44 isolates that were speciated by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we studied the MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations of penicillin, ampicillin, ceftriaxone, and clindamycin for Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus. None of the organisms was resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, although a few isolates were intermediately resistant; one strain of S. anginosus was tolerant to ampicillin, and another was tolerant to ceftriaxone. Six isolates were resistant to clindamycin, with representation from each of the three species. Relatively small differences in antibiotic susceptibilities among species of the S. milleri group show that speciation is unlikely to be important in selecting an antibiotic to treat infection caused by one of these isolates.

Three species compose the Streptococcus milleri group: Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus (5, 12, 13). Investigators who have used phenotypically differentiated strains within the S. milleri group have suggested that these three species have similar antibiotic susceptibilities (1, 4, 7, 8). Phenotypic identification to the species level, however, has been shown to be difficult and at times unreliable (3, 6, 9). In order to compare the antibiotic susceptibilities of species within the S. milleri group, we determined the MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) of four clinically relevant antibiotics for 44 genotypically characterized strains of the S. milleri group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Forty-four clinically significant isolates of the S. milleri group that had been isolated from different patients between 1985 and 2000 were studied. All had been implicated as the causative organisms in infection (2). Their sources of isolation are summarized in Table 1. These strains were assigned to the S. milleri group based on the results of API 20 Strep system (bioMérieux Vitek, Hazelton, Mo.) tests and were further speciated by PCR amplification and sequence analysis of a segment of the 16S rRNA gene (3). They were stored at −70°C after having been passaged no more than two or three times. In addition to two well-characterized strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae that have been studied repeatedly in our laboratory, the following American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) strains were included as reference strains: ATCC 27335 (S. intermedius), ATCC 9895 and ATCC 33397 (S. anginosus), and ATCC 29213 (Staphylococcus aureus).

TABLE 1.

Sources of isolates of Streptococcus milleri group

| Species | No. of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed spacea | Blood | CSFb | Urine | Wound | |

| S. intermedius(n = 12) | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| S. constellatus(n = 16) | 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| S. anginosus(n = 16) | 7 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

Includes abscess fluid, empyema, peritoneal fluid, and joint fluid.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

MIC and MBC testing.

Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) containing 0.5% yeast extract (Difco) (THY), a broth medium previously shown by our laboratory to be optimal for testing the MICs of S. pneumoniae (10), was used in this study. Preliminary studies showed that this medium supported the growth of S. milleri group isolates more reliably than Mueller-Hinton or tryptic soy broth. Penicillin G (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), ampicillin (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, N.J.), clindamycin (Sigma), and ceftriaxone (Roche, Nutley, N.J.) were dissolved in sterile, distilled H2O and then diluted in THY to yield 8 μg/ml. Serial twofold dilutions in THY yielded concentrations from 8 to 0.008 μg/ml. Bacteria were added to yield about 106 CFU/ml, and the tubes were incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2. MICs were defined as the lowest antibiotic concentrations at which there was no visible growth after 24 h of incubation. Subcultures of the last cloudy tube and the next four clear tubes were made, and CFU were counted after overnight incubation. MBC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration for which there was ≥99% killing. The geometric mean and median of the MIC and the MIC at which 90% of isolates were inhibited (MIC90) were determined for each antibiotic and for each isolate. Analogous values were calculated for the MBC.

Susceptibility (S), intermediate resistance (IR), and resistance (R) were defined in accord with NCCLS guidelines (11) as follows: penicillin, S ≤ 0.12, IR = 0.25 to 2, and R ≥ 4; ampicillin, S ≤ 0.25, IR = 0.5 to 4, and R ≥ 8; ceftriaxone, S ≤ 0.5, IR = 1, and R ≥ 2; and clindamycin, S ≤ 0.25, IR = 0.5, and R ≥ 1.

Statistical analysis.

The geometric mean MIC and MBC of each antibiotic were calculated for each bacterial species. When the MIC readings fell outside the range of antibiotic dilutions (e.g., >8 or <0.008 μg/ml), they were assigned the value of the next dilution in the series (e.g., 16 or 0.004 μg/ml, respectively). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine whether there were significant differences in susceptibility to each antibiotic among the three bacterial species. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to make pairwise comparisons of the MICs or MBCs between species. For all tests, α was equal to 0.05.

RESULTS

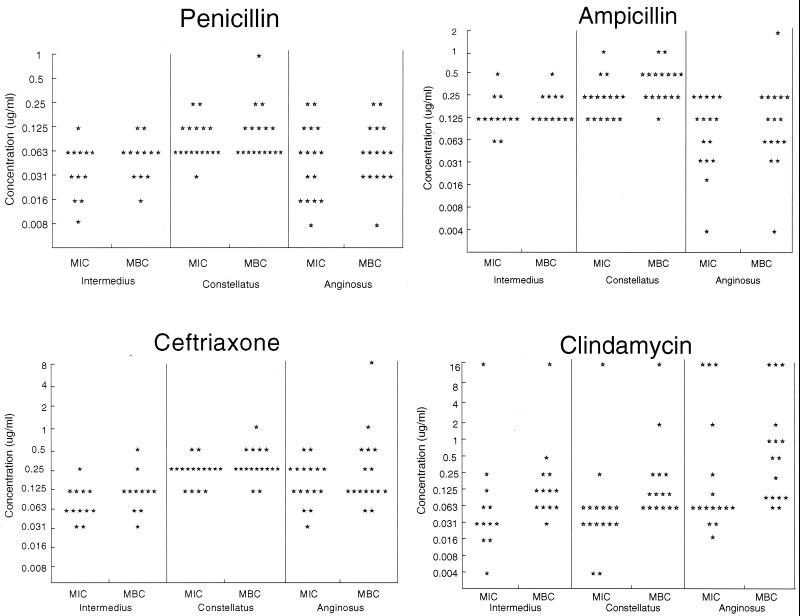

As shown in Fig. 1, none of 12 S. intermedius, 16 S. constellatus, and 16 S. anginosus isolates was resistant to penicillin, ampicillin, or ceftriaxone. Four isolates exhibited intermediate resistance to penicillin, and four were intermediately resistant to ampicillin; only one S. constellatus isolate was intermediately resistant to both of these drugs. All isolates were fully susceptible to ceftriaxone. In contrast, a total of six (14%) isolates were resistant to clindamycin, including at least one of each species studied.

FIG. 1.

MICs and MBCs of four antibiotics for S. intermedius, S. constellatus, and S. anginosus. Each point indicates the MIC or MBC for an individual isolate.

Table 2 summarizes the MIC50s, MIC90s, and geometric mean MICs. S. intermedius had the lowest mean MIC and tended to have the lowest MIC90 and S. constellatus had the highest mean MIC and tended to have the highest MIC90 for the three beta-lactam antibiotics. Differences among the species were significant (P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis test); for clindamycin, significant differences were not observed (P = 0.09).

TABLE 2.

| Drug and parameter | μg/ml

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. intermedius | S. constellatus | S. anginosus | |

| Penicillin | |||

| MIC50 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| MIC90 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 0.037 | 0.089 | 0.049 |

| Ampicillin | |||

| MIC50 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| MIC90 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.078 |

| Ceftriaxone | |||

| MIC50 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| MIC90 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Mean | 0.079 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| Clindamycin | |||

| MIC50 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| MIC90 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 16 |

| Mean | 0.060 | 0.053 | 0.21 |

Differences in MICs of beta-lactam antibiotics for the three species were significant (P < 0.05), but differences in MICs of clindamycin were not (P = 0.09) (Kruskal-Wallis test).

MIC of penicillin for S. constellatus was greater than that for S. intermedius; MIC of ampicillin for S. constellatus was greater than that for S. anginosus; MICs of ceftriaxone for S. constellatus and for S. anginosus were greater than that for S. intermedius; P < 0.05 for all comparisons (Mann-Whitney test).

Similar results were obtained when the MBCs of each antibiotic for each bacterial species were compared, but the interspecies differences were even greater (P ≤ 0.03 for the beta-lactams; P < 0.05 for clindamycin) (Table 3). The great majority of strains exhibited no tolerance to beta-lactam antibiotics: in 55% of 132 reactions (three antibiotics tested against 44 bacterial strains), the MIC was equal to the MBC, and in an additional 37%, there was only a twofold difference. For all other isolates, the difference between the MIC and the MBC was 4-fold, with the exception of two strains of S. anginosus, one of which exhibited a 16-fold difference in the case of ampicillin and another with a like difference for ceftriaxone. The MBCs of penicillin, ampicillin, and ceftriaxone for S. constellatus exceeded those for S. intermedius, and the MBC of ampicillin for S. constellatus was also greater than that for S. anginosus (P < 0.05 for all comparisons; Mann-Whitney test). The MBC of clindamycin for S. anginosus exceeded that for the other two species (P < 0.05; Mann-Whitney test).

TABLE 3.

| Drug and parameter | μg/ml

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. intermedius | S. constellatus | S. anginosus | |

| Penicillin | |||

| MBC50 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| MBC90 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Ampicillin | |||

| MBC50 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 |

| MBC90 | 0.25 | 1.0 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.10 |

| Ceftriaxone | |||

| MBC50 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| MBC90 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Mean | 0.12 | 0.30 | 0.24 |

| Clindamycin | |||

| MBC50 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| MBC90 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 16 |

| Mean | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.62 |

Differences in MBCs among the three species were significant (P < 0.05) (Kruskal-Wallis test).

MBC of penicillin for S. constellatus was greater than that for S. intermedius; MBC of ampicillin for S. constellatus was greater than those for S. intermedius and S. anginosus; MBC of ceftriaxone for S. constellatus was greater than that for S. intermedius; P < 0.05 for all comparisons (Mann-Whitney test); MBC of clindamycin for S. anginosus was greater than that for S. intermedius or S. constellatus (P < 0.05 for both comparisons) (Mann-Whitney test).

In order to determine whether there had been an increase in the resistances of S. milleri group organisms to penicillin in recent years, the MIC of each of the four antibiotics for S. constellatus was plotted by year. This organism was selected because the dates of isolation of the species spanned the full 15-year period. Regression analysis revealed no tendency toward increased resistance (r varied from −0.04 to 0.2, with P values ranging from 0.45 to 0.96).

DISCUSSION

In this study, determination of MICs and MBCs for 44 genetically characterized strains of the S. milleri group showed that all of the strains were susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, or ceftriaxone; at least one isolate from each species was resistant to clindamycin. Although there were, in fact, statistically significant differences in susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics among the three species studied, these differences were sufficiently small that they would not be clinically relevant. Since none of the isolates was resistant to any beta-lactam antibiotic and at least one isolate from each species was resistant to clindamycin, precise identification to the species level also does not help to predict antibiotic susceptibility and therefore is not important in the initial selection of antibiotic therapy. It is interesting to note that for >90% of the strains, the MBC of beta-lactam antibiotics was ≤2 times the MIC; tolerance was noted for only one isolate each with ampicillin and ceftriaxone. Even though these organisms are usually cultured from abscesses, and therefore infections caused by them are best treated surgically, there are clinical situations in which surgical drainage is difficult to accomplish, and it is useful to know that antibiotic tolerance is not likely to be an issue.

Some authors have expressed concern that clindamycin resistance in the S. milleri group is increasing (4, 7, 8). The bacterial strains that we studied were isolated from patients over a period of 2 decades, and there was no tendency for more recent isolates to show higher levels of antimicrobial resistance.

Our data on antimicrobial susceptibility are consistent with the division of the S. milleri group into three species, in that the finding of different susceptibilities, even though of no notable clinical significance, supports the speciation based on gene sequence analysis of RNA (3). Recent genetic studies have shown that S. constellatus and S. intermedius are more closely related to each other than either is to S. anginosus (3, 6), in contrast to earlier studies that did not show this as clearly (13). It may not be surprising that the pattern of antibiotic susceptibilities does not follow this apparent genetic relatedness, since acquisition of resistance is more recent and is driven by other factors, such as the ecological niche and the likelihood of prior exposure to antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Michael Tracy and Anna Wanahita participated equally in carrying out the research and writing this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bantar C, Fernandez Canigia L, Relloso S, Lanza A, Bianchini H, Smayevsky I. Species belonging to the “Streptococcus milleri” group: antimicrobial susceptibility and comparative prevalence in significant clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2020–2022. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.2020-2022.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarridge, J. E., III, S. Attori, D. M. Musher, J. Herbert, and S. Dunbar.S. intermedius, S. constellatus, and S. anginosus (“Streptococcus milleri group”) are of different clinical importance and not equally associated with abscess. Clin. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Clarridge J E, III, Osting C, Jalali M, Osborne J, Waddington M. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of “Streptococcus milleri” group isolates from a Veteran's Administration hospital population. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3681–3687. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3681-3687.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez-Garcés J-L, Alos J-I, Cogollos R. Bacteriologic characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility of 70 clinically significant isolates of Streptococcus milleri group. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;19:69–73. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs J A, Pietersen H G, Stobbringh E E, Soeters P B. Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus intermedius: clinical relevance, hemolytic, and serologic characteristics. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;104:547–553. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/104.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs J A, Schot C S, Bunschoten A E, Schouls L M. Rapid species identification of Streptococcus milleri strains by line blot hybridization: identification of a distinct 16S rRNA population closely related to Streptococcus constellatus. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1717–1721. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1717-1721.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs J A, Stobberingh E E. In-vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of the ‘Streptococcus milleri’ group (Steptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus intermedius) J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:371–375. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limia A, Jimenez M L, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:440–444. doi: 10.1007/s100960050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Limia A, Jimenez M L, Alarcon T, Lopez-Brea M. Comparison of three methods for identification of Streptococcus milleri group isolates to species level. Eur J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:128–131. doi: 10.1007/s100960050444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall K J, Musher D M, Mason E O. Testing of Streptococcus pneumoniae for resistance to penicillin. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1246–1250. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1246-1250.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standards. 5th ed. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiley R A, Beighton D. Emended descriptions and recognition of Streptococcus constellatus, Streptococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus anginosus as distinct species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:1–5. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiley R A, Duke B, Hardie J M, Hall L M C. Heterogenicity among 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacers of species within the Streptococcus milleri group. Microbiology. 1995;141:1461–1467. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]