Abstract

The amount of acrB, marA, and soxS mRNA was determined in 36 fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli from humans and animals, 27 of which displayed a multiple-resistance phenotype. acrB mRNA was elevated in 11 of 36 strains. A mutation at codon 45 (Arg→Cys) in acrR was found in 6 of these 11 strains. Ten of the 36 isolates appeared to overexpress soxS, and five appeared to overexpress marA. A number of mutations were found in the marR and soxR repressor genes, correlating with greater amounts of marA and soxS mRNA, respectively.

Multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli has been the focus of much recent attention, and a number of mechanisms that can contribute to this resistance have been elucidated. One of these is the transport of diverse substrates out of the cell by the AcrAB efflux transporter (15). This wide substrate profile leads to a multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) phenotype; the antibiotics to which acrAB can confer resistance include tetracycline, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, rifampin, novobiocin, erythromycin, β-lactams, and fluoroquinolones (15, 16, 17). AcrB is a large cytoplasmic membrane protein (10, 11), which associates with AcrA, a membrane fusion protein (18), and TolC, a protein thought to be the channel allowing extrusion of the substrates into the medium (7). The acrA and acrB genes are transcribed from one operon (11) with the acrR gene, a repressor of the operon that controls its activation transcribed divergently from a point downstream of the acrAB operon (12). The acrAB locus is a member of the mar, sox, and rob regulons (21). MarA, SoxS, and Rob are related transcriptional activators of the AraC family (2, 8, 20), and all can activate acrAB expression, although they are not involved in regulation of acrAB in response to general stress conditions (1, 3, 4, 5, 12, 14). Although E. coli possesses (at least) three transcriptional activators able to activate an overlapping set of genes in response to different environmental conditions, little is known about the relationship between the three genes and their contributions to control of antibiotic resistance. The importance of mutations in the sox, mar, and rob loci in antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates is at present unclear; mar and sox mutations have been identified in fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli (13, 17), but to date only a small number of strains have been studied (25 by Oethinger et al. and 23 by Maneewannakul and Levy). We have previously investigated the mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 E. coli strains from diverse origins (6); eight were isolated from calves and chickens in the United Kingdom (I87 to I94); the remainder were human isolates from hospitals in Argentina and Spain (I236 to I254 and I275 to I283). All are ciprofloxacin-resistant (MICs, 2 to 128 μg/ml) and have a substitution of leucine for serine at codon 83 of gyrA; 26 also have additional mutations in gyrA, and 24 possess single mutations in parC. None of the isolates have any mutations within gyrB or parE. Twenty-two of the isolates accumulated significantly less ciprofloxacin than did wild-type strains. The addition of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) abolished this effect, suggesting that an efflux pump may be important in the phenotype of these strains. This study examined the role of genes associated with efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance, including acrB, tolC, marA, soxS, and rob, in this set of isolates.

The susceptibilities of all strains to 10 antibiotics, four dyes, four disinfectants, and six detergents were determined with the agar doubling dilution method using Iso-Sensitest agar as described previously (6). At least 27 of the 36 isolates were multiply resistant, i.e., showed resistance to at least three separate classes of antibiotics (Table 1). Most of the isolates were resistant to the dyes tested, with some exceptions; I236, I246, and I276 were more susceptible to acriflavine (MIC of 16 or 32 μg/ml), and I281 and I283 were more susceptible to ethidium bromide (MICs, 32 to 64 μg/ml). All the isolates tested were resistant to deoxycholate, cholic acid, taurocholic acid, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propane sulfonate (CHAPS), Triton X-100, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, dehydroxycholate, sodium dodecyl sulfate, NP-40, and Triton X-114.

TABLE 1.

Strains with increased expression of efflux-associated genes, their susceptibilities to antibiotics and dyes, and their mutations in regulatory genesa

| Strain | Origin | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

acrB mRNA expression | acrR mutation | marA mRNA expression | marR mutation | soxS mRNA expression | soxR mutation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics

|

Dyes

|

||||||||||||

| CIP | TET | CHL | CEF | ACR | ET BR | ||||||||

| I113 | NCTC 10418 | 0.015 | 2 | 4 | 4 | >512 | >512 | wt | wt | wt | wt | wt | wt |

| I114 | NCTC 10538 | 0.06 | 4 | 8 | 8 | >512 | >512 | wt | wt | wt | wt | ||

| I87 | MAFF | 2 | 256 | 128 | 16 | 512 | >512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | wt | ||

| I88 | MAFF | 2 | >256 | 128 | 16 | >512 | >512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | wt | ||

| I89 | MAFF | 2 | >256 | 128 | 16 | >512 | >512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | wt | ||

| I236 | Spain | 32 | 256 | 128 | 4 | 32 | 512 | wt | wt | ↑ | Silent | ||

| I237 | Spain | 16 | 256 | 256 | 4 | 512 | 512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | ↑ | R71→S | |

| I238 | Spain | 4 | 128 | 256 | 8 | >512 | >512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | wt | ||

| I239 | Spain | 2 | 128 | 256 | 8 | >512 | 512 | ↑ | R45→C | wt | wt | ||

| I241 | Spain | 2 | 128 | 128 | 16 | >512 | >512 | ↑ | wt | wt | wt | ||

| I242 | Spain | 4 | 2 | 8 | 32 | >512 | >512 | wt | wt | ↑ | S31→A; R90→G | ||

| I244 | Spain | 32 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 512 | >512 | ↑ | wt | wt | ↑ | wt | |

| I245 | Spain | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 512 | >512 | ↑ | wt | wt | wt | ||

| I246 | Spain | 8 | 128 | 256 | 4 | 16 | 128 | wt | wt | ↑ | wt | ||

| I248 | Spain | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | >512 | >512 | wt | wt | ↑ | Insert | ||

| I251 | Spain | 8 | >256 | 128 | 4 | 512 | >512 | wt | wt | ↑ | Insert, L65→V | ||

| I253 | Spain | 32 | >256 | 256 | 32 | >512 | 512 | wt | wt | ↑ | wt | ||

| I254 | Spain | 128 | 4 | 256 | 8 | >512 | >512 | ↑ | Insertion | wt | ↑ | Three frame shifts, N25→Q | |

| I276 | Argentina | 32 | 128 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 512 | wt | ↑ | Y137→H | wt | ||

| I278 | Argentina | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | >512 | >512 | wt | ↑ | Y137→H | wt | ||

| I279 | Argentina | 8 | 256 | 8 | 4 | 256 | >512 | ↑ | wt | ↑ | Y137→H | wt | |

| I280 | Argentina | 32 | 128 | 8 | 4 | >512 | >512 | wt | ↑ | Y137→H | wt | ||

| I283 | Argentina | 32 | 256 | 8 | 8 | 512 | 64 | wt | ↑ | Y137→H | wt | ||

Abbreviations: CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; CHL, chloramphenicol; CEF, ceftazadine; ACR, acriflavine; ET BR, ethidium bromide; wt, wild-type; MAFF, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. ↑, overexpression.

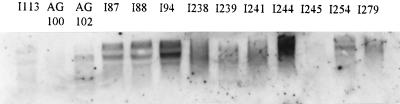

Northern blotting was used to determine the amounts of mRNA transcripts present in each strain. RNA was prepared and corresponding amounts (determined by spectrophotometry and by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by analysis with a Gene Genius image analyzer [SYNGENE, Cambridge, United Kingdom]) were electrophoresed under denaturing conditions before being subjected to blotting (19). A constant level of 16S expression was detected in all the strains (data not shown), indicating that there was no strain-to-strain variation in mRNA production. Amounts of acrB mRNA were determined for each strain, and results were compared to those for wild-type strains and AG102. Eleven of the 36 strains (31%) consistently produced more acrB mRNA than the wild-type controls (Fig. 1). More acrB mRNA signal was detected in the clinical isolates than in the marR mutant, AG102. There was a strong association between strains with high levels of acrB transcripts and ciprofloxacin efflux, with the isolates that produced most acrB mRNA being those for which CCCP had the greatest effect on the accumulation of ciprofloxacin (Table 1). However, there was no direct correlation between the level of acrB mRNA and MICs of ciprofloxacin and there was no obvious correlation between acrB mRNA amounts and the MICs of the other agents. The three strains which were hypersusceptible to acriflavine and ethidium bromide did not appear to produce any less acrB mRNA than wild-type strains in Northern blotting experiments. The contributions of other efflux systems and non-efflux-based resistance determinants may well mask the effect of AcrB.

FIG. 1.

Overproduction of acrB. The strains that overproduced acrB mRNA (I87, I94, I238, I241, I244, I245, I254 and I279) gave brighter bands than AG102 (which constitutively overexpresses marA mRNA), indicating that they produced more acrB than a Mar mutant strain.

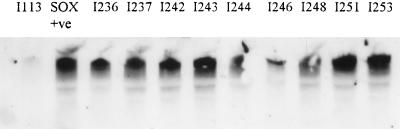

Most of the strains produced similar amounts of tolC mRNA compared to the wild-type strains (data not shown). Ten of the 36 strains (28%) showed more soxS mRNA than did the wild-type strains (Fig. 2). Of these 10 strains, only three appeared to overexpress acrB. Five of the 36 strains (14%) showed more marA mRNA than did the wild-type strains, but none of them produced as much as AG102. Only 1 of these 10 strains appeared to also overexpress acrB. All of the the strains possessed a constitutive level of rob mRNA comparable with that seen for the wild-type strains (data not shown). Interestingly all the strains with increased levels of marA mRNA originated in Argentina and all those with increased levels of soxS mRNA were from Spain; this may indicate that different conditions will favor the selection of one type of mutation over another. None of the veterinary isolates contained mutations in mar or sox genes; strains with increased levels of acrB mRNA were detected in isolates from both animals and humans.

FIG. 2.

Overproduction of soxS. The strains that overproduced soxS mRNA gave intensities of the transcript similar to that of the positive control strain, JTG1078 (Sox +ve). The soxS transcript was barely detectable in wild-type strains (e.g., I113).

To identify mutations leading to apparent overexpression of the genes investigated by Northern blotting, primers were designed to amplify overlapping products of <350 bp, which covered the genes themselves or the regulatory genes that control them. The acrR, soxR (soxS repressor), soxS, marR (marA repressor), and marA genes were all covered by overlapping amplimers. Single-stranded conformational polymorphism and DNA sequencing (6) of all isolates overexpressing acrB mRNA revealed four silent mutations in acrRA, six isolates had an amino acid substitution of cysteine for arginine at codon 45 of acrR, and one strain, I254, contained an insert of ∼1,000 bp in acrR. The isolates that showed increased marA mRNA all had a substitution of histidine for tyrosine at codon 137 of marR, the same as that found by Oethinger et al. (17). One strain, I283, had a substitution of arginine for cysteine at codon 63 in marA. Analysis of soxRS revealed mutations in both the soxR and soxS genes among the 10 isolates overproducing soxS mRNA. Five different amino acid changes were found in soxR (Asp25→Glu, Ser31→Ala, Leu65→Val, Arg71→Ser, and Arg90→Gly). An insertion of one base within codon 106, which changes the reading frame and leads to a stop codon 2 bp downstream of the insertion, was present in two of the strains (I248 and I251). Also, two amino acid substitutions were found within soxS in I237 and I253; one of these was a threonine-to-serine substitution at codon 38, and the other was a glycine-to-arginine substitution at codon 74. This diverse pattern of mutations shows that no single mutation is important in modulating the function of soxR; it also indicates that the isolates in this study are genetically diverse, as was seen from the number of silent mutations and deviations from the sequences deposited in GenBank.

Of the 11 strains that had increased amounts of acrB mRNA 8 appeared to overproduce this mRNA in a manner independent of soxS or marA regulation. Only 3 of the soxS mRNA overexpressing isolates and one marA mRNA overexpressing isolate were also acrB mutants. These data indicate that mutations in the acrR repressor gene are more likely to be involved in acrB derepression than mutations which lead to marA or soxS overexpression. Even when the acrR repressor mutations and mar and sox mutations are combined they do not account for all the strains which overproduced acrB mRNA. These data support previous work by Ma et al. (9) who demonstrated that the acrB operon can be activated in response to various stress conditions in the absence of mar, sox, and rob. The data from the present study indicate that the acrB pump may be involved in ciprofloxacin efflux in both clinical and veterinary isolates of E. coli and that a variety of mutations in different genes associated with efflux can have a role in controlling expression of acrB. No single mechanism is exclusively involved in acrB regulation. Further work is in progress to determine the role, if any, of the mutations in the regulatory genes described above.

The primers used to amplify the DNA used as probes in the blotting were designed from sequences deposited in GenBank (acrB, accession number J00734: nucleotides [nt] 3393 to 4412 [1,019 bp]; marA, accession number M96325: nt 1952 to 2239 [287 bp]; soxS, accession no. X59593: nt 424 to 582 [158 bp]; rob, accession number M97495: nt 423 to 1065 [642 bp]; tolC, accession number X54049: nt 548 to 837 [289 bp]; 16S rRNA, accession number J01859: nt 540 to 1139 [599 bp]).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to David White and Stuart Levy for their generous donations of control strains used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekshun M N, Levy S B. Regulation of chromosomally mediated multiple antibiotic resistance: the mar regulon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2067–2075. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amabile-Cuevas C F, Demple B. Molecular characterization of the soxRS genes of Escherichia coli: two genes control a superoxide stress regulon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4479–4484. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariza R R, Li Z, Ringstad N, Demple B. Activation of multiple antibiotic resistance and binding of stress-inducible promoters by Escherichia coli Rob protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1655–1661. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1655-1661.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbosa T M, Levy S B. Differential expression of over 60 chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli by constitutive expression of MarA. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3467–3474. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3467-3474.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennik H J M, Pomposiello P J, Thorne D F, Demple B. Defining a rob regulon in Escherichia coli by using transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3794–3801. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3794-3801.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everett M, Jin Y F, Ricci V, Piddock L J V. Contribution of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2380–2386. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fralick J A. Evidence that TolC is required for functioning of the Mar/AcrAB efflux pump of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5803–5805. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5803-5805.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George A M, Levy S B. Gene in the major cotransduction gap of the Escherichia coli K-12 linkage map required for the expression of chromosomal resistance to tetracycline and other antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1983;178:2507–2513. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.541-548.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma D, Cook D N, Alberti M, Pon N G, Nikaido H N, Hearst J E. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6299–6313. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6299-6313.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma D, Cook D N, Hearst J, Nikaido H N. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma D, Cook D N, Alberti M, Pon N G, Nikaido H N, Hearst J E. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;19:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma D, Alberti M, Lynch C, Hearst J E. In the regulation of the acrAB genes of Escherichia coli by global stress signals, the local repressor AcrR plays a modulating role. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:101–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.357881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maneewannakul K, Levy S B. Identification of mar mutants among quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1695–1698. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin R G, Gillette W K, Rosner J L. Promoter discrimination by the related transcriptional activators MarA and SoxS: differential regulation by differential binding. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:623–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikaido H N. Multidrug efflux pumps of Gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5853–5859. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5853-5859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikaido H N. Antibiotic resistance caused by Gram-negative multidrug efflux pumps. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S32–41. doi: 10.1086/514920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oethinger M, Podglajen I, Kern W V, Levy S B. Overexpression of the marA or soxS regulatory gene in clinical topoisomerase mutants of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2089–2094. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okusu H, Ma D, Nikaido H N. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:306–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.306-308.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pumbwe L, Piddock L J V. Two efflux systems expressed simultaneously im multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2861–2864. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2861-2864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skarstad K, Thony B, Hwang D S, Kornberg A. A novel binding protein of the origin of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5365–5370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White J D, Goldman D, Demple B, Levy S B. Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS or robA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6122–6126. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6122-6126.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]