Abstract

To date, only one study has reported changes in the gut microbiome of an ultramarathon runner before and after competing in the race. Herein we aimed to investigate changes in intestinal microbiota in nine ultramarathon runners. Eight of the nine participants ran 96.102 km (up 8062 m, down 6983 km) and one ran 99.12 km (up 8448 m, down 7369 m) within 38–44 h. Intestinal microbiota alterations were examined at three timepoints: before (Pre), after (Post), and 10 days after (Recovery) the race. The α- and β-diversity of intestinal microbiota were unaffected by the race. Six of the nine participants showed the B-type enterotype, while the remaining three showed the P-type enterotype; however, significant difference between enterotypes was not observed in the influence of the ultramarathon on intestinal microbiota. The abundance of mean Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, was significantly decreased from 2.9% (Pre) to 1.6% (Post), as well as other three butyrate producing bacteria. One participant with the largest decrease in F. prausnitzii abundance (− 85.7%) reported sluggishness and shallow sleep from Post to Recovery. Our findings revealed that the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria is decreased in ultramarathon runners, which consequently decreases butyrate levels in the intestine and affects host immune function.

Subject terms: Clinical microbiology, Microbiome, Predictive markers

Introduction

The human intestinal microbiota is composed of at least approximately 1000 species and 100 trillion microorganisms, mostly dominated by bacteria. There exists an intimate symbiosis between humans and intestinal microbiota, and pertinent bacterial species perform a vast array of functions, such as digestion, vitamin production, immune stimulation, pathogen growth inhibition, energy source production, and detoxification. Moreover, they are involved in immune function, consequently playing a pivotal role in maintaining host health and physiological function1. Intestinal microbiota is influenced by not only exercise habits2,3 but also exercise programs4–6. Several potential mechanisms, involving gut-associated lymphoid tissue, exercise-induced heat stress, ischemia, and changes in barrier function, have been suggested via which exercise alters intestinal microbiota7.

The effects of a single marathon on intestinal microbiota have been previously reported in half-8 and full-marathon9 runners. However, only one such ultramarathon-based study has been reported; briefly, Grosicki et al. examined changes in the gut microbiome of an ultramarathon runner before and after competing in the Western States Endurance Run (WSER), a 163-km mountain footrace, reporting most rapid and pronounced shifts in gut microbiome composition after acute exercise10. The increase in Veillonella abundance in intestinal microbiota has been observed in after both full marathon9 and WSER10. However, Veillonella is known to be associated with P-type enterotype which has high Prevotella abundance11. In contrast, the Japanese predominantly show B-type enterotype which has high Bacteroides abundance11–13. In addition, the influence of single stage ultramarathon with longer duration has not been examined. Therefore, we hypothesized that the influence of ultramarathon with longer duration gave the different influence on gut microbiota of Japanese runners from the previous studies8–10; especially, it is notable that ultramarathon-induced changes in B-type enterotype have not been reported to date.

In this study, we investigated changes in intestinal microbiota in participants competing in the Trans Japan Alps Race 2020 (TJAR2020), which is a major 415-km single-stage ultramarathon that takes place in the Japanese Alps Mountains. TJAR2020 was cancelled once started due to stormy weather caused by a typhoon. We herein examined runners who had reached > 61.5 km (up 6035 m; down 3145 m) when the decision was made to cancel the race 31 h after the start and who had arrived at Shinhotaka Onsen within 38–44 h of starting the race.

Results

Nine runners (ID: A to I) participated in this study. Their characteristics (mean ± SD) before the race were as follows: age = 46.9 ± 5.8 years, height = 171.1 ± 6.1 cm, weight = 63.3 ± 4.6 kg, body water = 41.2 ± 3.3 L, protein = 11.1 ± 0.9 kg, minerals = 3.8 ± 0.3 kg, body fat = 7.2 ± 1.7 kg, muscle mass = 53.0 ± 4.3 kg, lean body mass = 56. 1 ± 4.5 kg, skeletal muscle mass = 31.7 ± 2.6 kg, BMI = 21.6 ± 1.1 kg/m2, and body fat = 11.4% ± 2.7%.

The race started from the coast of Toyama Bay (altitude 0 m). The participants had crossed Tsurugi-dake (altitude 2999 m, 36.858 km from the start) and Yakushi-toge (altitude 2294 m, 61.5 km from the start) when the race was cancelled 31 h after the start and had reached Shinhotaka Onsen (altitude 1117 m, 96.102 km from the start) within 38–44 h of starting the race (Supplementary Figure S1). Eight of the nine participants ran 96.102 km (up 8062 m; down 6983 km) and one participant (ID: A) ran 99.12 km (up 8448 m; down 7369 m) (Supplementary Figure S2).

During the race, the intake values were as follows: energy = 3831.6 ± 710.3 kcal, protein = 84.2 ± 21.4 g, fat = 147.6 ± 64.6 g, carbohydrate = 545.7 ± 103.9 g, and sodium = 13.3 ± 8.8 g (salt equivalent). Further, the energy expenditure and physical activity levels of participants during the race were 13,789 ± 943 kcal (331 ± 24 kcal/h) and 4.89 ± 0.16, and the energy balance was − 9,957 ± 517 kcal.

For analyses, we collected spontaneously excreted feces before (Pre), after (Post), and 10 days after the race (Recovery). Intestinal microbiota was analyzed by 16S rRNA-based large-scale genome sequencing, yielding raw data of 26,564 ± 2683 reads. Subsequently, 19,689 ± 621 reads were filtered, and 18,255 ± 765 reads passed the filter. The 10,000 reads randomely selected from that passed through the filter were used for operational taxonomic unit (OTU) analysis. This eventually led to the identification of 2,828 OTUs, 9 phyla (Supplementary Figure S3), 156 genera (Supplementary Figure S4), and 380 species.

In case of Pre-samples, hierarchical clustering of intestinal microbiota at the genus level revealed that six participants showed B-type enterotype with a high proportion of Bacteroides and the remaining three (ID: B, F, and G) showed P-type enterotype with a high proportion of Prevotella (Supplementary Figure S5). In addition, the Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio was higher in case of B- than for P-type enterotypes at Pre; however, no significant change was observed between Pre and Post nor between Pre and Recovery (Supplementary Figure S6). Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe, p-value cut off = 0.1 FDR adjusted) did not find a significantly different bacteria between B- and P-types at all levels from phylum to OTU in both at Pre and Post (data not shown). Comparison of abundance (Pre vs Post) at the species levels showed eight and one significantly changed bacteria in B- and P-types, respectively, while no bacteria showed significant difference in both B- and P-types (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, in subsequent comparisons at the OTU and species levels, all nine participants were analyzed as a single group without considering differences in enterotypes.

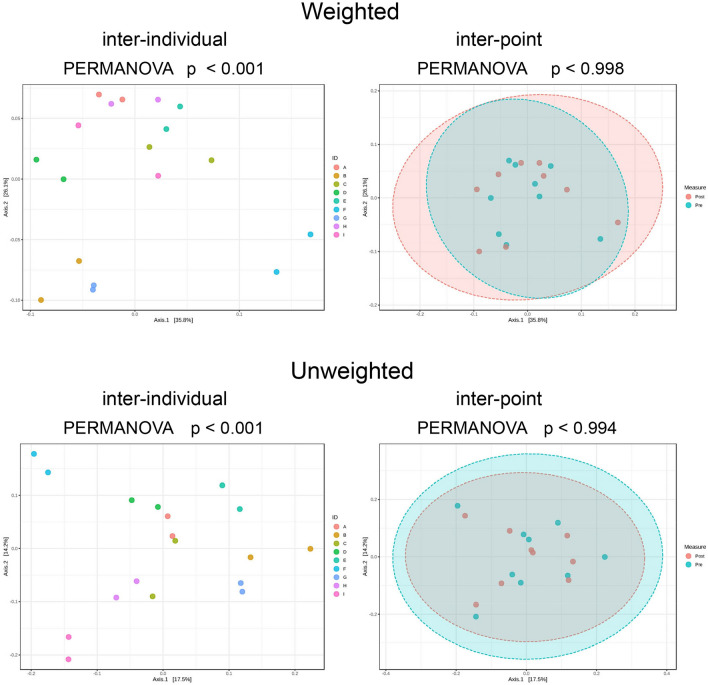

No significant changes in α-diversity indices (OTU level; ACE, Chao1, Fisher, Observed, Shannon, and Simpson) were found between Pre and Post (Table 1). Besides, β-diversity comparisons (OTU level) showed significant interindividual differences in both weighted (p < 0.001) and unweighted (p < 0.001) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), but no differences were detected between Pre and Post (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of α-diversity indices of intestinal microbiota (OTU level) before (Pre) and after (Post) the race.

| Pre | Post | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| ACE | 483.8 | 157.2 | 445.6 | 141.5 | 0.269 |

| Chao1 | 504.7 | 148.6 | 446.6 | 143.9 | 0.118 |

| Fisher | 59.0 | 21.1 | 57.4 | 16.1 | 0.681 |

| Observed | 299.6 | 83.5 | 294.4 | 63.7 | 0.734 |

| Shannon | 3.695 | 0.247 | 3.789 | 0.316 | 0.174 |

| Simpson | 0.938 | 0.035 | 0.938 | 0.052 | 0.986 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of β-diversity. Significant interindividual differences were observed in both weighted (p < 0.001) and unweighted (p < 0.001) PCoA, whereas no differences were observed before (Pre) and after (Post) the race.

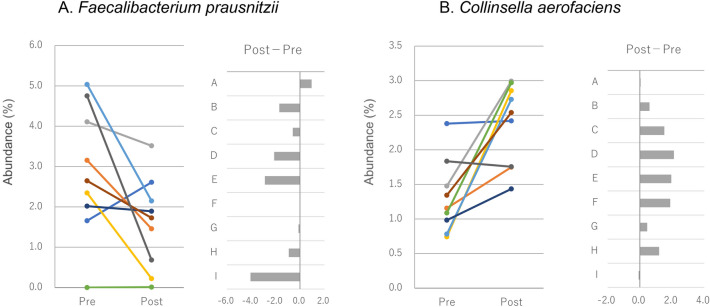

LEfSe (p-value cut off = 0.1 FDR adjusted) did not find significantly different bacteria between Pre and Post at all levels from phylum to OTU (data not shown). Since LEfSe does not support paired data, we then tried to find bacteria that changed before (Pre) and after (Post) the race. The Wilcoxon signed rank sum test was applied to compare the abundance of bacterial species between Pre and Post. A significant increase was found in the abundance of Collinsella aerofaciens, Catenibacillus scindens, Clostridium sp E2, Ruminococcaceae bacterium LM158, Alistipes putredinis, Drancourtella massiliensis, Massiliomicrobiota timonensis, Clostridium sp Culture Jar 17, Romboutsia timonensis, and Streptococcus sanguinis, and a significant decrease was noted in the abundance of Blautia luti, Eubacterium rectale, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and butyrate-producing bacterium SS3/4 (Table 2). F. prausnitzii and C. aerofaciens showed a change of > 1% (mean value) in their abundance between Pre and Post. The abundance of F. prausnitzii decreased in seven and that of C. aerofaciens increased in eight of the nine participants (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Bacterial species with a significant change in abundance before (Pre) and after (Post) the race.

| Name | Pre (%) | Post (%) | Change | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Collinsella aerofaciens | 1.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0.6 | Up | 0.005 |

| Catenibacillus scindens | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Up | 0.014 |

| Clostridium sp E2 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Up | 0.014 |

| Ruminococcaceae bacterium LM158 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | Up | 0.014 |

| Alistipes putredinis | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | Up | 0.022 |

| Blautia luti | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Down | 0.032 |

| Drancourtella massiliensis | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | Up | 0.035 |

| Massiliomicrobiota timonensis | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | Up | 0.036 |

| Clostridium sp Culture Jar 17 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | Up | 0.036 |

| Eubacterium rectale | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Down | 0.036 |

| Romboutsia timonensis | < 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | Up | 0.039 |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.1 | Down | 0.041 |

| Butyrate-producing bacterium SS3/4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | Down | 0.042 |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | Up | 0.042 |

Figure 2.

Changes in abundance (%) of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (A) and Collinsella aerofaciens (B) before (Pre) and after (Post) the race.

Veillonella atypica was the only bacteria belonging to the genus Veillonella. Scheiman et al. reported an increase in Veillonella relative abundance in runners postmarathon, and V. atypica was isolated from stool samples9. However, in this study, V. atypica abundance at Post was < 0.1% in all but one participant, and no significant changes were present between Pre and Post.

On assessing the relationship between diet and intestinal microbiota, we found a negative correlation between changes in Ruminococcaceae bacterium LM158 abundance (Post to Pre) and intake of lipids (g/kg BW, ρ = − 0.750, p = 0. 020), energy (kcal/kg BW, ρ = − 0.733, p = 0.025), and sodium (salt equivalent, g/kg BW, ρ = − 0.733, p = 0.025) during the race (Supplementary Figure S7A–C). In contrast, a positive correlation was found between changes in D. massiliensis abundance (Post to Pre) and intake of protein (g/kg BW, ρ = 0.812, p = 0.008) (Supplementary Figure S7D).

The α-diversity indices (OTU level) did not show any significant differences between Recovery and Pre [ACE (p = 0.359), Chao1 (p = 0.133), Fisher (p = 0.496), Observed (p = 0.426), Shannon (p = 0.673), and Simpson (p = 0.652)]. In addition, in terms of β-diversity (OTU level), no significant differences were seen in both weighted (p < 1) and unweighted (p < 0.997) PCoA on comparing Pre and Recovery, whereas significant interindividual differences were detected in both weighted (p < 0.001) and unweighted (p < 0.001) PCoA.

On comparing Pre and Recovery using the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test, we found a significant decrease in the abundance of only four species: B. luti (p = 0.020), Clostridium glycyrrhizinilyticum (p = 0.020), Bacteroides dorei (p = 0.027), and Sutterella wadsworthensis (p = 0.036).

One participant (ID: I) reported sluggishness and shallow sleep from Post to Recovery. In this participant, F. prausnitzii abundance was 4.75% at Pre, which was the second highest among all participants, but it decreased to 0.68% at Post (− 85.7%), which was the seventh highest among all participants (Fig. 2), and a slight increase to 1.34% was noted at Recovery. None of the participants reported any changes in physical conditions from Recovery to the following 2 weeks.

Discussion

In the study conducted by Grosicki et al., the Shannon index (α-diversity) of intestinal microbiota in case of a runner who participated in a 163-km ultramarathon was 2.78 ± 0.05 between 21 weeks before and 10 days after the race10. This variation was observed in only one runner, and although an increase or decrease was detected depending on the time of the measurement, the change was small10. The Shannon index (α-diversity) of intestinal microbiota in case of our study participants was 3.695 ± 0.247 at Pre and 3.789 ± 0.316 at Post, with no significant changes observed between Pre and Post. It is notable that β-diversity was not affected by race, although significant differences were found among individuals. Collectively, our findings suggest that intestinal microbiota diversity is more likely to vary among individuals than to be affected by ultramarathon.

In the case report by Grosicki et al., abundance of Faecalibacterium genera after an ultramarathon (approx. 20%) decreased from Pre-Race (approx. 25%)10. Although the abundance of F. prausinizii was namely reported, the post-race decrease of Faecalibacterium seems consistent with this study.

A decrease in F. prausnitzii abundance is reportedly associated with various diseases14–20. The anti-inflammatory effects of F. prausnitzii are apparently mediated by its products, such as butyrate21,22. Furthermore, F. prausnitzii abundance is evidently associated with peripheral T-cell subsets23. In this study, we observed a decrease in F. prausnitzii abundance as well as three other butyrate producing bacteria. As importance of butyrate has been reported to systemic immunity24,25, the decrease in the butyrate producing bacteria could affect the immunity of ultramarathon runners.

Ultramarathon26–31 runners often experience upper respiratory tract infections after the race; acute exercise has been suggested to increase the risk of infection (open window hypothesis) via immune suppression32–35. However, the effects of a single bout of exercise on immune function is a controversial topic. For example, dense population at competitions can itself increase the risk of infection36,37, and immunity is not only affected by exercise but also sleep and nutrition38. Our study participants did not report any symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, runny nose, and sore throat) of upper respiratory tract infections from Post to Recovery and even up to 2 weeks after Recovery. However, one participant showing the highest decrease in F. prausnitzii abundance reported sluggishness and shallow sleep from Post to Recovery. It is notable that the number of participants in TJAR2020 was limited to 30; further, all athletes were required to take certain measures for infection prevention, such as wearing a mask until the start of the race. Therefore, the risk of infection owing to dense population was negligible. In addition, as TJAR2020 is a single-stage ultramarathon, it is necessary to sleep and eat during the race. Considering these facts, the ultramarathon, including sleep and nutrition, could affect immune function of the participant through the decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria such as F. prausnitzii abundance.

C. aerofaciens is widely distributed in the human intestine. A study found its prevalence to be lower in patients with irritable bowel syndrome than in healthy individuals39, while another study reported contradictory results40. Moreover, C. aerofaciens is reportedly an obesity biomarker41. Despite this, its influence on host physiology remains to be explained. Similar to a previous study that observed an increase in its abundance in half-marathon runners8, even in this study, C. aerofaciens abundance showed an increase in seven of the nine participants after the race (p = 0.005). Therefore, we believe that endurance running can increase the abundance of C. aerofaciens. However, the race duration of half-marathon and TJAR2020 is considerably different, and accordingly, energy expenditure is markedly different too. Further studies are thus warranted to elucidate the relationship between C. aerofaciens abundance and endurance running.

Scheiman et al. reported a significant increase in Veillonella relative abundance in runners postmarathon9. As Veillonella produces propionate from lactate, a model was proposed in which Veillonella converts lactate produced during exercise to propionate in the intestinal tract, contributing to improved performance9. An increase in the abundance of Veillonella was also detected after the 163-km WSER10. In contrast, in this study, only V. atypica was detected from the genus Veillonella. Its abundance was < 0.1% in all participants, except in one participant at Post, and no significant changes were present between Pre and Post. The energy expenditure during the WSER is typically 13,000–16,000 kcal42. The runner (age 32 y) reported by Grosicki et al. finished the WSER 2019 in the top-1010; his finish time should be about 16 h according to the race record (https://www.wser.org/results/2019-results/, accessed on April 16, 2021). Thereby, his energy expenditure was estimated to be ≥ 800–1000 kcal/h. In contrast, the energy expenditure in case of our study participants was 294–372 kcal/h. As evident, in comparison with full marathon and the WSER, the energy expenditure per hour was lesser, and the contribution of the glycolytic system was thereby considered to be smaller. We believe that less lactate production could be responsible for the differences observed between our results and those previously reported.

The changes observed in intestinal microbiota in this study were inconsistent with those observed in half-8 and full marathon runners9. A single-stage ultramarathon lasts long enough to require eating and sleeping during the race43, and this seems to have impacted our results. Our findings suggest that changes in intestinal microbiota in ultramarathon runners need to be considered separately from those in half- or full marathon runners.

Ruminococcaceae bacterium LM15844 and D. massiliensis45 abundance was found to show a significant change before and after a race, and the extent of change was correlated with energy and nutrient intake during the race. Although genomic information is available for both species, no information exists pertaining to nutrient requirements. The number of the participants was limited to nine, and the correlation seems to be dependent on data related to three (Ruminococcaceae bacterium LM158) or two (D. massiliensis) participants. Therefore, further studies need to be conducted to verify the validity of such correlations.

Intestinal microbiota rapidly responds to environmental changes: dietary changes cause significant variations within a day, with recovery occurring within 2 days of returning to a normal diet46. Herein intestinal microbiota diversity did not differ between Pre and Recovery, and only four of the 380 species identified showed differences in their abundance. Thereby, intestinal microbiota was considered to have recovered to the Pre-race condition at Recovery.

As the race was cancelled 31 h after the start because of the inclement weather, the runners had to hurry descend by the nearest route and return home on their own. The announcement of the cancellation was emailed to the individual runners, but since they were in the middle of the race, the timing of when the individual runners learned of the cancellation varied. Some of them arrived at Shinhotaka Onsen in pieces between 38 and 44 h after the start. We caught the descending runners at Shinhotaka Onsen and asked individual runners to cooperate with our study. It was in stormy weather, in late evening to night, and the runners were so disappointed at the race cancellation and even more exhausted by the race that we could not require them many things. This situation gave some limitation for this study. The timing of the stool collection should be important. We asked to collect the first spontaneously excreted stool after the arrival at Shinhotaka Onsen, assuming the race-route was from start to Shinhotaka Onsen. However, Shinhotaka Onsen was not originally the goal, the runners arrived there 7–13 h after the official cancellation, and the stool excreted during the descent, if any, could not be collected. Therefore, it was not possible to control the timing of post-race stool collection.

In addition to the major limitation described above, this study has a few limitations. As TJAR2020 is a single-stage ultramarathon, participants are required to eat and sleep during the race. Both sleep47 and diet potentially affect intestinal microbiota. In this study, we investigated the effects of diet, but not sleep. To understand ultramarathon-induced changes more comprehensively, it is pivotal to assess the relationship between sleep and intestinal microbiota too. Antibiotic use is known to potently influence microbiome composition, although we did not check the use. This study did not measure the change in metabolites that could help elucidate the impact of the ultramarathon on gut microbiota. Regarding the physical condition of participants, an interview was conducted approximately 1 month after the race, which may have led to recall bias. The effects of the race on immune function should have been comprehended, for example, by maintaining a logbook or examination by a physician. Finally, the number of the participants was limited to nine; further studies involving more participants are warranted to validate the accuracy of our results.

To summarize, we herein examined changes in intestinal microbiota before and after participation in ultramarathon, with the aim of assessing the influence of ultramarathon on intestinal microbiota in the Japanese. A decrease in the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, such as F. prausnitzii, was observed after the race, indicative of a decrease in butyrate levels in the intestine, which is bound to have affected the immune function of our study participants. Further, C. aerofaciens abundance was found to increase after the race. In addition, ultramarathon-induced changes in intestinal microbiota were independent of the enterotype. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the influence of diet and sleep on intestinal microbiota and also to assess the effects on host immune function.

Methods

Participants

We herein included nine male runners (aged 40–56 years old) who had participated in TJAR2020. All of them had completed a full marathon within 3 h and 20 min or a 100-km marathon within 10 h and 30 min within 2 years of TJAR2020.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participant of TJAR2020 (scheduled on Aug 8, 2021) and (2) good physical condition and ability to safely participate in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) suffering from or having a history of serious cardiovascular, hepatic, renal, respiratory, endocrine, or metabolic disorders, (2) suffering from or having a history of hepatitis B or C, (3) having had 200 mL blood drawn within 1 month or 400 mL blood drawn within 3 months prior to TJAR2020, and (4) having participated in a clinical trial within 3 months prior to TJAR2020 or being a current participant of a clinical trial.

Eligible runners were informed in writing as well as orally of the purpose, methods, and expected results of the study, the protection of personal information and disclosure of study results, and the possibility of withdrawing their consent to participate. They understood the information shared with them and voluntarily signed a consent form to participate in this study.

This study was approved by the ethical review committee of Juntendo University Graduate School (no. 2021-17 and 2021-89 for intestinal microbiota and 2021-26 for dietary survey and body measurements). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Study design

Naturally excreted feces were obtained from all participants at three timepoints: Pre (Aug 5–7), Post (first feces after the race), and Recovery (Aug 18–20). As gut microbiota has substantial intra-individual temporal variability that exceeds the inter-individual variability48 e.g. rapid change with diet46, control is needed to confirm intra-individual variability. A case report by Grosicki et al. showed an apparent change in gut microbiota after an ultramarathon, 2 h after the race, compared to baseline (21 weeks before the race), Pre-Race (2 weeks before the race) and Recovery (10 days after the race)10. With reference to this case-report, this study designed to use Pre-race (within 3 days before the race) as baseline and Recovery (10 days after the race) to confirm the return to the baseline.

The participants measured their weight/body composition using InBody 470 (InBody Japan, Tokyo, Japan), and Pre-race weight with ware and luggage to be carried on their back was measured at the reception site of Mirage Land (Uozu City, Toyama, Japan) approximately 8 h before the start of the race.

The race started from the coast of Toyama Bay (altitude 0 m) at 00:00 on Aug 8, 2021. The participants had crossed Tsurugi-dake (altitude 2999 m, 36.858 km from the start) and Yakushi-toge (altitude 2294 m, 61.5 km from the start) when the race was cancelled 31 h after the start and had reached Shinhotaka Onsen (altitude 1117 m, 96.102 km from the start) within 38–44 h of starting the race (Supplementary Figure S1).

The participants were interviewed to assess their physical condition from the goal of the race until the collection of feces at Recovery and for 2 weeks thereafter. The reports submitted by the participants to the TJAR2020 office were obtained from the office.

Energy expenditure

Eight participants ran 96.102 km (up 8062 m, down 6,983 m), and one participant ran 99.12 km (up 8448 m, down 7,369 m) (Supplementary Figure S2). The distance and cumulative altitude difference were calculated by the geographic information system software Kashmir 3D v9.3.7 (DAN Sugimoto, http://www.kashmir3d.com/, accessed on Aug. 7, 2021).

Energy consumption during the race was calculated using this formula, which was previously used to estimate energy expenditure during mountaineering by Nakahara et al.49:

Energy expenditure (kcal) = [1.8 × duration (h) + 0.3 × distance (km) + 10.0 × cumulative altitude of up (km) + 0.6 × cumulative altitude of down (km)] × [body weight (kg) + luggage to be carried (kg)].

The body and luggage weights were measured before the race and used for [body weight (kg) + luggage to be carried (kg)].Physical activity levels during the race were calculated using energy expenditure and basal metabolic standard values listed in the Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (2020).

Dietary intake

The intake of energy, protein, fat, carbohydrate, and sodium (salt equivalent) during the race was calculated based on food intake reported by the participants to the TJAR2020 office and nutrition facts label on each food item.

Energy balance

Energy balance was calculated by subtracting energy expenditure from energy intake during the race.

Intestinal microbiota

All participants placed the stool collection sheet “Raku-Ryu Cup” (Takahashi Katasei, Tokyo, Japan) on the toilet seat, followed by collecting their stool sample and sampling an aliquot (c.a. 0.3 g) into a tube containing zirconia beads (BioMedica Science, Tokyo, Japan) and 2 mL RNA Later® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo). The lid of the tube was then tightly closed, and the mixture was vigorously shaken approximately 40 times. The stool samples were subsequently stored in a refrigerator (4 °C) until needed for DNA extraction.

To the stool samples (150 µL) with RNA Later®, 850 µL TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM EDTA) containing RNase A (final concentration 100 µg/mL; Invitrogen, Japan) and lysozyme (final concentration 3.0 mg/mL; Sigma, Tokyo, Japan) was added, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle shaking. Subsequently, purified achromopeptidase (final concentration 2,000 U/mL; Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) was added, and the mixture was further incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, sodium dodecyl sulfate (final concentration 1%) and proteinase K (final concentration 1 mg/mL; Nacalai, Tokyo, Japan) were added, followed by incubation at 55 °C for 1 h.

DNA was extracted using phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 75% ethanol, and dissolved in 200 µL TE buffer.

The V1-V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using 27Fmod (5′-AGRGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG 3′) and 338R (5′-TGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′) primers. The amplicons thus obtained (approximately 330 bp) were purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan). The amount of DNA was then quantified using the Quant-iT™ Picogreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) on a TBS-380 Mini-Fluorometer (Turner Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan).

16S metagenomic sequencing was performed using MiSeq, according to the protocol recommended by Illumina. Two paired-end reads were merged by the fastq-join program based on overlapping sequences. Sequences with an average quality value of < 25 and inaccurate universal primers at both ends were excluded. The 10,000 reads from each sample that passed the quality filter were sorted in order of quality and classified into OTUs with a 97% pairwise-identity cutoff using the UCLUST program (Edgar 2010) v5.2.32 (https://www.drive5.com). Each OTU was classified against the GLSEARCH program and the genomic databases of RDP and National Center for Biotechnology Information.

DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing, and taxonomic assignment were conducted by MyMetagenome (Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Values represent mean ± SD. Intraindividual α-diversity and intestinal microbiota comparisons were achieved using the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test. PCoA was used for β-diversity comparisons (Pre vs. Post and Pre vs. Recovery).

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ) was used for correlation of the change in the bacterial abundance (Post to Pre) that showed significant changes in response to the race and intake of energy and nutrients during the race.

MicrobiomeAnalyst (https://www.microbiomeanalyst.ca/; accessed on Nov 10, 2021) and MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/; accessed on Nov 10, 2021) were used for intestinal microbiota analyses. Correlation was analyzed by IBM SPSS v23 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants and TJAR staff, particularly Mr. Yukawa, Mr. Koshida and Mr. Iijima, for supporting this study. We also thank Dr. Tetsuyuki Yamagata (Social Medicine Institute Technology College of Physical Therapy, Tokyo, Japan) for his advice in planning the study. The article processing charge was partly supported by the Joint Research Program of Juntendo University, Faculty of Health and Sports Science.

Author contributions

M.S. and Y.S. conceived the concept and designed the study, and also acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. M.S. wrote the draft manuscript, and Y.S. revised and completed the manuscript. Y.S. supervised the research. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-10791-y.

References

- 1.Marchesi JR, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65:330–339. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressa C, et al. Differences in gut microbiota profile between women with active lifestyle and sedentary women. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke SF, et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut. 2014;63:1913–1920. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen JM, et al. Exercise alters gut microbiota composition and function in lean and obese humans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018;50:747–757. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronin O, et al. A prospective metagenomic and metabolomic analysis of the impact of exercise and/or whey protein supplementation on the gut microbiome of sedentary adults. mSystems. 2018 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00044-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munukka E, et al. Six-week endurance exercise alters gut metagenome that is not reflected in systemic metabolism in over-weight women. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2323. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mailing LJ, Allen JM, Buford TW, Fields CJ, Woods JA. Exercise and the gut microbiome: A review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications for human health. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2019;47:75–85. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao X, et al. Response of gut microbiota to metabolite changes induced by endurance exercise. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:765. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheiman J, et al. Meta-omics analysis of elite athletes identifies a performance-enhancing microbe that functions via lactate metabolism. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1104–1109. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosicki GJ, Durk RP, Bagley JR. Rapid gut microbiome changes in a world-class ultramarathon runner. Physiol. Rep. 2019;7:e14313. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama J, et al. Diversity in gut bacterial community of school-age children in Asia. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8397. doi: 10.1038/srep08397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishijima S, et al. The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA Res. 2016;23:125–133. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto T, et al. Decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the gut microbiota of Crohn's disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;28:613–619. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sokol H, et al. Low counts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in colitis microbiota. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1183–1189. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vakili B, Fateh A, AsadzadehAghdaei H, Sotoodehnejadnematalahi F, Siadat SD. Intestinal microbiota in elderly inpatients with clostridioides difficile infection. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020;13:2723–2731. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S262019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto-Cardoso S, et al. Fecal bacterial communities in treated HIV infected individuals on two antiretroviral regimens. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43741. doi: 10.1038/srep43741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu H, et al. Intestinal microbiota was assessed in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Intestinal microbiota of HBV cirrhotic patients. Microb. Ecol. 2011;61:693–703. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Shen J, Ran ZH. Association between faecalibacterium prausnitzii reduction and inflammatory bowel disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014;2014:872725. doi: 10.1155/2014/872725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokol H, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:16731–16736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breyner NM, et al. Microbial anti-inflammatory molecule (MAM) from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii shows a protective effect on DNBS and DSS-induced colitis model in mice through inhibition of NF-kappaB pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quevrain E, et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2016;65:415–425. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jinnouchi M, Miyahara T, Suzuki Y. Coix seed consumption affects the gut microbiota and the peripheral lymphocyte subset profiles of healthy male adults. Nutrients. 2021 doi: 10.3390/nu13114079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamer HM, et al. Review article: The role of butyrate on colonic function. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;27:104–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canani RB, et al. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1519–1528. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benitez-Paez A, et al. Depletion of Blautia species in the microbiota of obese children relates to intestinal inflammation and metabolic phenotype worsening. MSystems. 2020 doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00857-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rios-Covian D, et al. Intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:185. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruzzese E, et al. Disrupted intestinal microbiota and intestinal inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and its restoration with Lactobacillus GG: A randomised clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabeerdoss J, Jayakanthan P, Pugazhendhi S, Ramakrishna BS. Alterations of mucosal microbiota in the colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease revealed by real time polymerase chain reaction amplification of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015;142:23–32. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.162091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fite A, et al. Longitudinal analyses of gut mucosal microbiotas in ulcerative colitis in relation to patient age and disease severity and duration. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:849–856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02574-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeller G, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014;10:766. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castell LM, Poortmans JR, Newsholme EA. Does glutamine have a role in reducing infections in athletes? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1996;73:488–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00334429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieman DC, et al. Immune and oxidative changes during and following the Western States Endurance Run. Int. J. Sports Med. 2003;24:541–547. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters EM, Bateman ED. Ultramarathon running and upper respiratory tract infections. An epidemiological survey. S. Afr. Med. J. 1983;64:582–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters EM, Goetzsche JM, Grobbelaar B, Noakes TD. Vitamin C supplementation reduces the incidence of postrace symptoms of upper-respiratory-tract infection in ultramarathon runners. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;57:170–174. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JP, Turner JE. Debunking the myth of exercise-induced immune suppression: Redefining the impact of exercise on immunological health across the lifespan. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:648. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell JP, Turner JE. There is limited existing evidence to support the common assumption that strenuous endurance exercise bouts impair immune competency. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2019;15:105–109. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1548933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson RJ, et al. Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2020;26:8–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kassinen A, et al. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masoodi I, et al. Microbial dysbiosis in irritable bowel syndrome: A single-center metagenomic study in Saudi Arabia. JGH Open. 2020;4:649–655. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuddy J, Slivka D, Hailes W, Dumke C, Ruby BC. Total energy expenditure, body water turnover, hydration status, and blood composition during the western states 100. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009 doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000355133.78976.4a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Costa RJS, Knechtle B, Tarnopolsky M, Hoffman MD. Nutrition for ultramarathon running: Trail, track, and road. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019;29:130–140. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoch CL, 2020. NCBI taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Durand GA, et al. Drancourtella massiliensis gen. nov., sp. Nov. isolated from fresh healthy human faecal sample from South France. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;11:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.David LA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosicki GJ, Riemann BL, Flatt AA, Valentino T, Lustgarten MS. Self-reported sleep quality is associated with gut microbiome composition in young, healthy individuals: A pilot study. Sleep Med. 2020;73:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vandeputte D, et al. Temporal variability in quantitative human gut microbiome profiles and implications for clinical research. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6740. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27098-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakahara R, Hagiwara M, Yamamoto M. An equation to estmate energy comsumption during climbing; From the relationships among the walking time, walking distance, body weight, and pack weight. Jpn. J. Mountain Med. 2006;26:115–121. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Schoch CL, 2020. NCBI taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]