Abstract

Women account for a disproportionate percentage of new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa indicating a need for female-initiated HIV prevention options congruent with their lifestyles. The dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention is one such option. We explored the interest of women, who used this ring during the Microbicide Trials Network’s ASPIRE and HOPE studies, in using the ring post-licensure and what they perceived as important considerations for future use. We also explored perspectives of HOPE participants’ male partners on their involvement in their partners’ future ring use. Women appeared keen to use the ring in the future and expressed desires for easy access, support for both ongoing and new users and intense community engagement. In parallel, male partners indicated high levels of interest in supporting their partners’ ring use and being involved in ring use decision making. These data offer important insights for ring rollout planning and engagement activities.

Keywords: Future use, Dapivirine vaginal ring, HIV prevention

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounts for approximately 70% of the global burden of HIV infection [1, 2], with women continuing to account for a disproportionate percentage of new HIV infections among individuals aged 15 and older [3]. The current approaches to HIV prevention, including increased antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage to promote treatment as prevention, scale up of medical male circumcision, and rollout of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), have helped address the burden of infection[1]. Nevertheless, disproportionate HIV incidence rates among women remain a challenge [4–6], and there is a continued need for female-initiated, long-acting HIV prevention options that are congruent with female end-users’ lifestyles in these highly burdened settings.

The dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention (referred to as the ring hereafter) is an antiretroviral-containing silicone matrix ring that slowly releases drug into the vagina over a one-month period and must be in place for at least 24 h to help protect a woman against HIV [7]. The ring was tested by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) and International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) in two phase III trials (MTN-020/ASPIRE study and IPM-027/Ring Study) [8, 9] and two corresponding open label extension studies (MTN-025/HOPE study and IPM-032/DREAM study) [10, 11] over a six year period. The two clinical trials demonstrated the ring to be well tolerated and to reduce HIV risk by approximately 27% (ASPIRE) and 35% (Ring Study) respectively. Results from the open-label extension studies showed increases in ring use and modelling data suggest greater risk reduction by about 50% across both studies[10, 12, 13]. Subsequently, on 24 July 2020, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) provided a positive benefit-risk opinion on this product for HIV prevention use by women aged 18 and over [14]. This was followed by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendation, on 26 January 2021, of the dapivirine vaginal ring as a new choice for HIV prevention for women at substantial risk of HIV infection [15]. The opinion and recommendation are important to pave the way for regulatory approvals in SSA and other regions and bring the ring a step closer to licensure in a number of African countries and being made available to women who could benefit from this discreet, long-acting method as an additional HIV prevention option.

In this analysis, we report first-hand accounts from a follow-up qualitative study with women who used the ring during both the ASPIRE (35 months maximum follow-up) and HOPE (up to 12 months follow-up) studies [8, 16]. This is one of the first studies to explore participants’ interest in using the ring in the future, post-licensure, and what they perceived as important considerations for their and ring-naïve women’s future ring use. We also report feedback from male partners of HOPE participants on their involvement in future ring use by their female partners. These novel data have not been previously described and offer important insights for ring rollout planning and engagement activities.

Methods

Study Design

MTN-032/AHA (Assessment of ASPIRE and HOPE Adherence) was a multisite qualitative exploratory sub-study among participants exiting the MTN-020/ASPIRE trial and its subsequent open label extension, MTN-025/HOPE, conducted between June 2016 and October 2018 at six sub-Saharan African sites in Malawi (Lilongwe); South Africa (Durban [Botha’s Hill, eThekwini], Johannesburg); Uganda (Kampala) and Zimbabwe (Harare). The main objectives of this two-phased study were to explore socio-contextual and trial specific issues which affected participants’ adherence to the ring. Phase 1 included the conduct of individual indepth interviews (IDIs) and adherence pattern-based focus group discussions (FGDs) with former ASPIRE participants, and Phase 2 included IDIs with former HOPE participants and, using FGDs, expanded the central research questions to include male partner attitudes towards and experiences with the ring and their perspectives of their female partner’s attitudes and experiences. The methods and results of both phases have been previously reported [17, 18]. In this analysis, we included data collected during AHA Phase 2, to explore former HOPE participant and male partner views regarding future use of the ring for HIV prevention. Briefly, former HOPE participants (referred to as female participants hereafter) were categorized on the adherence level of low, middle and high for their Month 1 ring’s residual drug level and subsequently pre-selected for recruitment into IDIs using a recruitment list generated by the MTN Data Management Centre. Enrolment target per site was 10 women enrolled across the three adherence categories in a 1:3:1 ratio. The middle group was targeted for over-sampling in comparison to those with well-defined non-use and consistent use to increase the likelihood of recruiting and understanding the reasons for women’s inconsistent or intermittent ring use. Participants were invited to participate in an IDI 0–9 months after they had exited HOPE. All male partners enrolled were in a primary sexual relationship with HOPE female participants during their HOPE participation and were contacted for participation based on a recruitment list of randomly selected former HOPE participants (from the full HOPE cohort) once the HOPE participant’s permission to contact them was confirmed. The male partners who enrolled in AHA (referred to as male participants hereafter) were however not necessarily the partners of the female participants who enrolled in AHA. Two FGDs per site were conducted with male participants, with the exception of the Johannesburg site where there were insufficient participants to host a second FGD, and a single IDI with one male participant was held instead.

Procedures

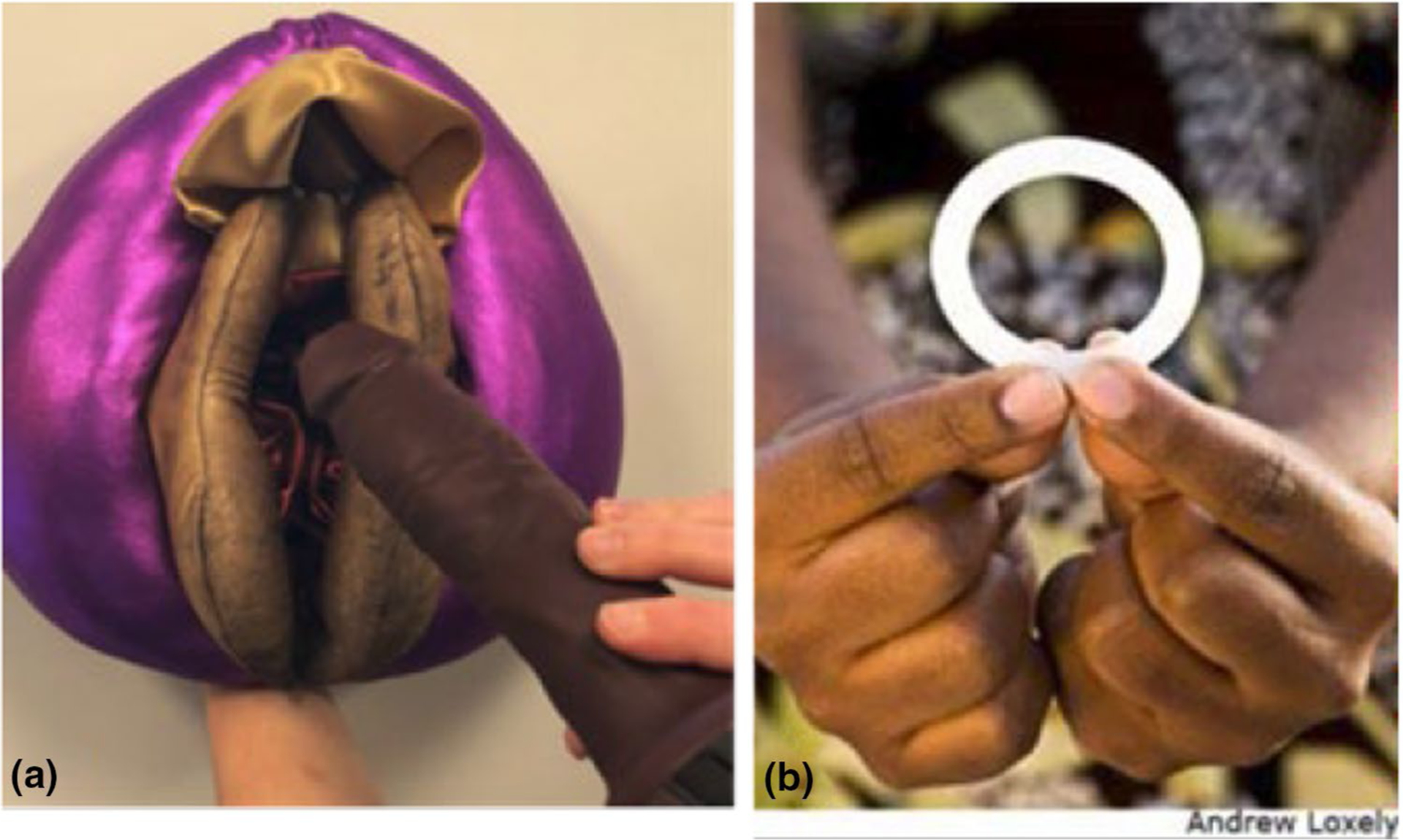

All participants provided written informed consent before demographic and behavioural information was individually collected through interviewer-administered questionnaires available in English and local languages (Chichewa in Malawi, Zulu in South Africa, Luganda in Uganda and Shona in Zimbabwe). Trained local social scientists fluent in these languages then facilitated the IDIs and FGDs using semi-structured guides. Participants in FGDs were requested to use pseudonyms to protect their identities. Topics discussed with female participants included motivations for enrolment into HOPE, effect of knowledge of the ring’s efficacy on adherence behaviour, motivation for continued study participation, future ring use, marketing and other product rollout issues. Topics discussed with male participants included perceptions of sexual health risk, experiences of partner ring use (i.e., physical sensation), understanding of ASPIRE trial results and efficacy and how these factors impacted their support of ring use. Vulva puppets, penis models and sample placebo rings (See Fig. 1) were available for participants to demonstrate how the ring affected their sexual life (if at all). IDIs and FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed/translated from the local language into English directly, if applicable.

Fig. 1.

Photographic illustration of a) vulva puppet, penis model and b) placebo ring

Analysis

Descriptive quantitative data on demographic characteristics and behaviour were tabulated using Stata 15.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) with no statistical tests or p values reported. Transcripts were uploaded and coded in Dedoose (Version 8.1.8), a qualitative software programme. Analysts used a codebook developed iteratively, and descriptively coded for key themes and topics. Intercoder consistency was confirmed at a level above a mean kappa score of 0.70 for 10% of transcripts across five coders and code application queries and disagreements were discussed and resolved by the coding team. For this analysis, data coded as “FUTURE” were extracted from IDI and FGD transcripts. The “FUTURE” code included topics such as willingness or plans to use (or not use) the ring in future; where they would want to access the ring; amount they would be willing to pay; preferred frequency of ring use; who should advocate ring use (self or others); thoughts on who else would use or benefit from the ring when accessible; what would make the ring appealing to use and what concerns others may have about using the ring. Data were summarized into analytical memos, which were reviewed by the writing team weekly to discuss coding questions, issues and emerging themes.

Results

Demographic and behavioural data by average residual drug level results have been published previously [18] and are presented in Table 1, 2 by participant group and country. Overall, 111 independently recruited individuals participated in the IDIs and FGDs conducted across all sites. This included 58 female IDI participants and 54 male participants (53 in FGDS, 1 in IDI). The mean age of female participants was 32 years (range 23–48), just over half (52.5%; N = 31) had completed secondary schooling and almost three quarters (74.2%; N = 43) were earning an income. The majority of female participants (96.6%; N = 56) had a primary partner and just under half (44.8%; N = 26) were married. In terms of adherence, 20.6% (N = 12) of female participants were in the low category, 41.3% (N = 24) were in the middle category and 37.9% (N = 22) were in the high category [18]. The availability of male participants for recruitment varied by site with some sites reporting a small percentage of HOPE participants granting permission to contact their male partners (e.g. 12% or 30%) and others indicating close to 100% providing this permission [19]. Male partner participation rate was 41%. The mean age of male participants was 38 years (range 21–61), less than half (38.9%; N = 21) had completed their secondary education and more than three quarters (85.2%; N = 46) were earning an income. All male participants had a primary partner, and more than half (61.1%; N = 33) were married (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information across the four participating countries

| Malawi | South Africaa | Uganda | Zimbabwe | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female participants | N = 9 | N = 29 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 58 |

| Mean Age (Min, Max) | 31 (24–38) | 29 (23–47) | 34 (25–45) | 37 (30–48) | 31.8 (23–48) |

| Secondary education complete | 2 (22.2%) | 22 (75.9%) | 2 (20.0%) | 5 (50%) | 31 (53.5%) |

| Earning own income (#) | 4 (44.4%) | 22 (75.9%) | 8 (80.0%) | 9 (90%) | 43 (74.2%) |

| Has a primary sex partner | 8 (88.9%) | 28 (96.6%) | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 56 (96.6%) |

| Currently married | 7 (77.8%) | 4 (13.8%) | 6 (60.0%) | 9 (90.0%) | 26 (44.8%) |

| Male participants | N = 11 | N = 22 | N = 8 | N = 13 | N = 54 |

| Mean Age (Min, Max) | 37 (30–44) | 33 (23–49) | 46 (34–61) | 40 (21–50) | 37.5 (21–61) |

| Secondary education complete | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (45.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 9 (69.2%) | 21 (38.9%) |

| Earning own income (#) | 11 (100%) | 14 (63.6%) | 8 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 46 (85.2%) |

| Has a primary sex partner | 11 (100%) | 22 (100%) | 8 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 54 (100%) |

| Currently married | 10 (90.9%) | 4 (18.2%) | 6 (75.0%) | 13 (100%) | 33 (61.1%) |

Sites included Durban [Botha’s Hill, eThekwini] and Johannesburg

Table 2.

Participant HIV risk and worries and future ring use attitudes

| HIV risk and worries | Female Participants N = 58 | Male Participants N = 54 |

|---|---|---|

| Worried about getting HIV in the next 12 months | ||

| Not worried at all | 14 (25.5%) | 29 (56.9%) |

| A little/somewhat worried | 21 (38.2%) | 17 (33.3%) |

| Very/Extremely worried | 20 (36.4%) | 5 (9.8%) |

| Likelihood of getting infected with HIV in the next 12 months | ||

| Extremely unlikely | 15 (27.3%) | 23 (45.1%) |

| Very unlikely | 8 (14.5%) | 6 (11.8%) |

| Somewhat likely | 16 (29.1%) | 20 (39.2%) |

| Very likely | 7 (12.7%) | 2 (3.9%) |

| Extremely likely | 9 (16.4%) | 0 |

| Primary partner has other partners | ||

| Yes | 11 (19.6%) | 6 (11.1%) |

| Unknown | 37 (66.1%) | 27 (50.0%) |

| Knowledge of Partner HIV status | N/Aa | |

| HIV negative | 32 (57.1%) | |

| HIV positive | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Unknown | 23 (41.1%) | |

| Knowledge of own HIV status | N/Aa | |

| HIV negative | 45 (83.3%) | |

| HIV positive | 3 (5.6%) | |

| Unknown | 6 (11.1%) | |

| Male condom use during last vaginal sex act | 23 (39.7%) | 19 (35.2%) |

| Had anal sex in past 3 months | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Future ring use attitudes | ||

| Interested in future ring use/supporting ring use in future | ||

| Yes | 54 (98.2%) | 52 (96.3%) |

| No | 0 | 0 |

| Don’t Know | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| Lowest acceptable level of protection | ||

| 50% (half) | 11 (20.0%) | 8 (14.8%) |

| 75% (three-quarters) | 8 (14.5%) | 7 (13.0%) |

| 90% (almost full protection) | 13 (23.6%) | 15 (27.8%) |

| 100% (full protection) | 23 (41.8%) | 24 (44.4%) |

In the MTN-032 Phase 2 Behavior Assessment, female participants were asked “What is the HIV status of your [spouse /primary sex partner]?” while male participants were asked “What is your HIV status?”

We first present the participants’ quantitative reports about HIV risk perceptions. Subsequently, we present data on qualitative accounts of future interest in ring use, factors contributing to this interest, suggested implementation considerations for future ring-naïve users, and male partner considerations.

HIV Worries and Risk

In terms of worries about contracting HIV, almost three quarters (74.6%, N = 41) of female participants were either a little (38.2%; N = 21) or very worried (36.4%; N = 20) about getting HIV in the next 12 months and more than half (58.2%; N = 32) thought it was likely that they could get infected with HIV within this timeframe. Many were unaware if their partner had additional partners (66.1%; N = 37) or what their partner’s HIV status was (41.1%; N = 23). Less than half (39.7%, N = 23) reported using male condoms during their last vaginal sex act. In comparison, more than half (56.9%, N = 29) of male participants were not worried about getting HIV in the next 12 months and thought it was unlikely that they could get infected with HIV within this timeframe, although half were unaware if their partner had additional partners (50.0%; N = 27). The majority of male participants reported being aware of their HIV status (88.9%; N = 48) and more than a third (35.2%; N = 19) reported using condoms during their last vaginal sex act. Anal sex was reported by only 1 participant in each group (See Table 2).

Interest in Future Use of the Ring and Acceptable Levels of Protection

Quantitative data indicated that almost all of the female participants (98.2%; N = 54) and male participants (96.3%; N = 52) were supportive of future ring use when asked if they would use or support their partner’s use of a vaginal ring for HIV prevention in the future. The majority indicated acceptable levels of HIV protection to be between 90% and 100% (female participants: 65.4%; N = 36; male participants: 72.2%, N = 39) (See Table 2).

IDIs with female participants concurred with interest in future ring use reported quantitatively. The majority of women across study sites reported that they will use the vaginal ring in the future if it provides a maximum level of protection against HIV: “We want it to be 100%. That’s what will reassure me that I’m fully protected.” [4205, IDI, 43, Zengeza, Zimbabwe]. Despite this desire for high efficacy, some women acknowledged that the ring could still offer protection if its efficacy was lower. Most participants were aware, from ASPIRE and HOPE study results, that the ring did not provide 100% reduction of HIV risk and that there was greater risk reduction from the ring with higher adherence. This participant explains her continued interest in the ring with this information in mind: “I will still like it (the ring if < 100% effective) because I know it has a drug. It only requires that you keep on using it and adhere to instructions.” [4210, IDI, 48, Zengeza, Zimbabwe]. Some also added their perspectives that other users would be less reckless with their sexual behaviour if they were still at some risk of acquiring HIV: “It should be 75% so that people should not be reckless. They should know that the 25% puts them at a risk of getting HIV and they should be able to protect themselves by being faithful to their partners.” [7209, IDI, 29, Lilongwe, Malawi].

Factors Contributing to Female Participant’s Interest in Future Ring Use

Female participants across sites reported the ring’s efficacy and their personal experience using it (discreetness, ease of use, lack of side effects) as main factors contributing to their interest in future use. As the following participant from Uganda explains, her familiarity with the ring meant that it was not an unknown foreign object, and this contributed to her willingness to use it: “What might motivate me is because I do not fear it, I have experienced it and I know it works” [6205, IDI, 36, Kampala, Uganda]. This familiarity with the ring was echoed by other female participants who described themselves as pioneers of ring use, and believed their experience using the ring could be used to sensitize other ring naive women: “I will be interested to use it because I know its background… I am like one of the pioneers…I will be able to sensitize other people about the ring.” [7209, IDI, 29, Lilongwe, Malawi]. Easy access to the ring, available supply and free or reasonable cost were also emphasized by many participants as important contributing factors to future ring use: “I just wish it could be sold in the same way pills are sold. It should be widely available in places which would not cause me any inconvenience to access it.” [4206, IDI, 33, Zengeza, Zimbabwe].

Female participants offered differing opinions about support from male partners as a contributing factor for future ring use. Some said it was important to have this kind of acceptance and support as men might dismiss the ring because it is designed for women: “ I wish men could accept the ring… They should not be jealous of things available for exclusive use by women. Men disregard the female condom very much. They say, “When you open it and see how big it is, it makes you lose your appetite” [lose interest in sex].” [4206, IDI, 33, Zengeza, Zimbabwe]. A number of participants did not feel they would need support from anyone else to use the ring because the ring is discreet and dependent on the user herself: “If you get people who support [ring use] saying you know what it’s good and give you information, really at the end of the day it depends on you if you want {to use the ring] or you don’t.” [2208, IDI, 35, Johannesburg, South Africa].

These participants reported other operational suggestions. This included the ring having easily understandable instructions for use, reminders for users to change the ring monthly and receipt of drug level result feedback so women could have information about how well they were using the ring. One participant acknowledged that being in certain settings might carry a higher risk of sexual assault, and the availability of an on-demand protective product might enhance its value to some women: “It should provide protection immediately when I insert it. Most of us go to discotheques a lot. Young girls should go to discotheques without worries in case they get raped.” [6201, IDI, 33, Kampala, Uganda].

Perceptions of Ring Demand and Promotion Among Ring Naïve Women as Reported by Female Participants

Many female participants stressed the awareness of self-risk and partner promiscuity as factors that would motivate ring naïve women to use the ring to protect themselves from HIV, especially in the younger age group: “We are the ones with promiscuous husbands. Even those promiscuous women. So, I would imagine that the majority of the age group of the young will accept it most.” [4204, IDI, 31, Zengeza, Zimbabwe]. That said, the majority of female participants reported that ring-naïve women would be resistant to trying the ring unless they understood its purpose and were provided with complete information and reassurance about ring efficacy, positioning, safety and impact during sex for them to be able to use it: “If they know that the ring protects against this and that but if they don’t know that [ring information], they would not like it. They would say “such a big thing, we can’t use it.” [3206, IDI, 27, Durban-eThekwini, South Africa].

The ring’s user-dependent nature (user dependent on herself to use the ring), discreet use, month long protection and lower burden due to monthly insertion were also reported by many as additional factors that should be promoted as ring use benefits to new users. The ring was described as something that women could truly control themselves: “It’s the fact that you can use the ring as an individual without anyone knowing about it. It will be your personal secret that you are using the ring. So, no one can stop or discourage you.” [4202, IDI, 30, Zengeza, Zimbabwe].

A majority of participants indicated that there should be extensive community education and mobilization by health care providers to help motivate and support ring naïve women to use the ring. There was also a strong view that former HOPE participants, as pioneers of ring use, should be involved in this community education: “We can be the role models…Like we can go to the communities where I was doing sex work and ask them; “look at me, I have been having multiple sexual partners but because I was using the ring, here I am, I am still HIV negative. [7209, IDI, 29, Lilongwe, Malawi].

Male Partners’ Interest in Being Involved in Future Ring Use Decision Making

Overall, most male participants were keen to be involved in their partners ring use decision making. They described themselves as wanting to know about the sexual and reproductive health products their partners are using, be it for contraception, sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatment or HIV prevention and indicated that their knowledge and awareness during decision making was important to provide their approval and support and to mitigate relationship problems. The mention of male partner approval suggests a likelihood that male partners do not necessarily support women’s autonomous use of the ring: “I think that is very important because she must make that [ring use] decision knowing that you are aware of it. Yes, because usually with men when women are taking anything even the prevention pills, we want to know because at the end of the day you don’t know whether those are prevention pills or STIs pills or whatever pill.” (2304, IDI, 45, Johannesburg, South Africa).

Male partners’ opinions about their roles in ring use decision-making varied. Some said male partners should be completely involved in decision making while some said they should only be involved in terms of providing support. One male participant explained that ideally men should be fully involved but in a way that is well-balanced, and supportive of women and in a manner that respects his female partner and does not introduce suspicion: “We should be 100% involved in the decisions because this is a device which is preventing the AIDS epidemic that has caused havoc in this world. So, if men allow women to protect themselves without suspecting them of cheating or suspecting them of promiscuity, I think that would be a very good thing.” [Gaza, FGD, 47, Zengeza, Zimbabwe]. Mechanisms of support mentioned included male partners being involved in the ring use conversation, being present to ensure a woman’s consistent ring use as well as escorting women to the clinic. It was implied that this would make their partners feel pride and happiness within themselves and with peers: “The woman feels proud and is very happy if the man is involved in the new thing that is taking place. The woman knows that if my husband is supporting me and even escorting me, it means this thing is good.” [R6, FGD, 40, Lilongwe, Malawi].

There were also some examples of male partner involvement mentioned that pointed towards partnership dynamics and communication, and how the ring could help mitigate men’s fears of HIV infection. For example, male participants expressed a desire to know of their partners ring use so they are aware that there is some form of HIV protection if they did not use a condom: “They (men) need to be involved so that they know about it [ring use] and know that they no longer have sex using a condom with their partner because there is something providing them with protection as she is wearing the ring.” (Sanele, FGD, 28 Durban-Botha’s Hill, South Africa). A participant from Uganda recognized that, during periods of time when men might be absent for long periods, women might take on an additional partner and ring use would give men peace of mind knowing that their partners (and consequently themselves) would be protected: “You can be walking and then they arrest and imprison you for seven months. Do you think your partner will wait for the seven months? It is better that she uses the ring.” (Abdu, FGD, 34, Kampala, Uganda).

Discussion

In this paper we described former HOPE participants interest in future ring use, what factors were important in deciding to use it, and what factors would promote ring use among ring naïve women. Additionally, we investigated the interest of male partners of former HOPE participants in decision-making and support related to their partners’ future ring use. These analyses offered several key insights. Firstly, female participants were interested in using the ring in the future and many were motivated to use it because of their own positive personal experiences. Secondly, women recognized that ring use support would be important for ongoing ring users, new users and for community members. Finally, male participants were supportive of future ring use and wanted to be involved in ring use decision making to varying degrees and for various reasons including improved adherence, better partner dynamics and to mitigate men’s fear of HIV.

Many female participants found monthly use of the ring acceptable and there was agreement that the ring should be worn all the time instead of intermittently. They also indicated that their future use would be encouraged if the ring offered 90%−100% protection from HIV, and for some, immediate protection. These aspirational attitudes for higher efficacy were intriguing given that these female participants had all participated in ASPIRE and were aware that the ring conferred 27%–37% reduction in risk of HIV acquisition [8], but are likely due to the conversations when opting to join HOPE about continuing to study ring efficacy and to show effectiveness in a real world setting. Women’s interest in the ring, despite oral PrEP availability in some settings, provides support for the necessity of choice in prevention products. There was acceptance that the ring’s efficacy is lower than their desired target, and recognition that efficacy will depend on adherence. These data emphasize the need for effective and culturally-suitable messaging for future ring rollout to ensure end-user comprehension particularly with regard to the ring not being fully protective, but more effective if the user adheres consistently as reported in open-label extension studies and modelling of ring efficacy[13]. These messages are important for future users and their personal networks, healthcare providers, community stakeholders, and government gatekeepers to understand.

Regarding the level and type of support they needed to use the ring, there were those participants who reported that they needed no support as they have ring use experience, and those who preferred having support and acceptance from male partners and others in their social networks. Individual differences between the groups of women who felt confident vs. those who lacked confidence may have been driven by personality type and/or life circumstances. Market segmentation research into the ring [20] and other health technologies [21] has highlighted such differences in profile types of users, and confirmed the need for tailored health promotion efforts and counselling that will respond and appeal to women’s’ differing personality characteristics and desires to achieve efficient and effective HIV prevention. Marketing research to effectively promote uptake of novel and newly approved technologies to the widest potential pool of users thus requires the design of multiple intervention strategies to innovatively reach each target segment [21].

When discussing support that ring naïve women may require, many female participants indicated that extensive community education and sensitization by trained healthcare providers was essential. They also said that they themselves should be involved in information sharing and serve as Ring Ambassadors. Interest of trial participants to present themselves to their peers and others in their networks as product ambassadors and agents of change by virtue of their trial participation has been previously reported [22] and attributed to feelings of pride, excitement and gratification about contributing to research with potential to change lives or to “make a difference”. Other research has noted that participation in research can also enhance a sense of agency and selflessness among participants earned from their contribution to the advancement of science [23]. Testimonials or education from ring-experienced pioneers is a form of peer education which has been described as a useful, effective and sustainable educational approach for health interventions globally, including HIV prevention. Peer educators are perceived as more trustworthy or socially credible than research study staff, and can effectively gain access to target communities and facilitate increases in knowledge and attitude and behavioural change [24]. In the ASPIRE trial, study participants developed interpersonal connections with each other and staff through visit attendance and participant engagement activities. They reported being more open and honest with each other than with study staff, and that they positively influenced each other’s adherence [25, 26]. The peer engagement activities in ASPIRE were also reported to have helped address circulating negative rumours about the ring [27]. Additionally, peer support club models, such as those that were implemented in the FACTS 001 and EMPOWER PrEP trials, while not always well attended due mainly to logistical reasons, were well received among those who did attend [28–30]. These peer-involved models offer a flexible approach, adaptable for local contexts that provide opportunities to share knowledge and experience in an environment that encourages mutual support and could potentially be a useful and low-cost strategy to support ring naïve women’s use of the ring as scale up activities increase.

Male participants interest in supporting their partners’ use of the ring was high. Many of them reported they should be integrally involved in decision making around ring use, suggesting there was not necessarily support for women’s autonomous ring use of this prevention method. Reasoning that male partners provided for the necessity of their involvement focussed on women’s promiscuity rather than their own and included recognition that they were impacted by their female partners’ actions. The concept of secondary protection (protecting the male partner by protecting the woman) was also raised. As reported in other research [17, 31, 32], the importance of male partner education and awareness of their partners’ ring use was emphasized so that they can approve and support its use without concern. There was consensus that adherence to the ring would be improved if it was used with male partner approval and support, a sentiment that was consistent with female data from ASPIRE and HOPE [18, 32] where it was established that ring use disclosure to partners was important to gain support and for improved adherence. However, women also had fears of disclosure, and the consequences it may bring, including an association with promiscuity, partner distrust or anger, or even intimate partner violence. A counselling intervention called Community Health clinic model for Agency in Relationships and Safer Microbicide Adherence (CHARISMA)[33, 34] was designed to increase male partner support for female-initiated HIV prevention intervention use and improve women’s ability to use these products safely and consistently. CHARISMA was piloted at the Johannesburg HOPE site [33] and contributed to ~ two thirds of these participants disclosing ring use to their partners[35]. In many settings, and with many populations, there is an important need for interventions like these to counsel women on the value of ring use disclosure and to offer them skills to do so while prioritizing women’s agency to choose whether to disclose ring use.

There are some limitations to be considered when interpreting these study results. First, there may have been some recall bias because interviews about HOPE adherence were conducted several months after completion of HOPE participation. That said, the focus of this analysis was on perspectives of future use of the ring, not on attitudes or behaviors that occurred during the study that may have been more subject to recall bias. Participants may have felt inclined to indicate interest in future ring use when there was none, and thus there may have been some social desirability bias. Still, it is worth noting that the participants in this study were part of a cohort that had participated in both ASPIRE and HOPE and thus, for many, had already demonstrated many years of commitment to ring use. Finally, recruitment of the male participant sample was dependent on HOPE participants’ permission to contact male partners, and his agreement to participate. It is possible that women who did not use the ring, reported complaints from male partners, or who did not inform male partners of their study participation would have not provided consent to contact the partner. Male partners that were not accessible may have had differing views than the sample selected here.

Conclusion

Women participating in the ASPIRE and HOPE studies and selected for the AHA Phase 2 interviews appeared keen to use the dapivirine vaginal ring in the future to protect themselves from HIV and provided several important insights about future ring use that are important to future scale up considerations. This included a desire for easy access to the ring and ring use support for both ongoing and new users as well as intense community engagement to enable women to protect themselves from HIV without judgement. In parallel, male partners indicated high levels of interest in supporting their female partners’ use of the ring and being involved in ring use decision making. These data confirm that the ring has the potential to be an effective and acceptable HIV prevention option for women at risk of HIV infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the study participants for their participation and dedication. The authors thank the research site study team members, the MTN-032/AHA Protocol Management Team, the MTN Leadership Operations Center, Women’s Global Health Imperative (WGHI) RTI International and FHI360 for their contributions to data collection. The AHA trial was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). The MTN is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, and UM1AI106707), with cofunding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the US National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The rings used as sample products were developed and supplied by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM).

Funding

This work was funded by the Division of AIDS, US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, US Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US National Institute of Mental Health, US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Code Availability The Dedoose qualitative software programme (Version 8.1.8) used for coding of transcripts is available.

Ethical Approval The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at RTI International and local IRBs at each of the study sites and was overseen by the regulatory infrastructure of the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Data Availability

Data is available as required.

References

- 1.Kharsany ABM, Karim QA. HIV infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current status, Challenges and Opportunities. Open AIDS J. 2016;10:34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramjee G, Daniels B. Women and HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Res Ther. 2013;10(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles to go—closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices ON;one: UNAIDS; 2018. [Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/miles-to-go_en.pdf.

- 4.UNAIDS Data 2020 Online2020 [Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf.

- 5.Consortium. EfCOaHOET. HIV incidence among women using intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a copper intrauterine device, or a levonorgestrel implant for contraception: a randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):303–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AVERT. HIV and AIDS in East and Southern Africa Regional Overview [Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/overview.

- 7.International Partnership for Microbicides. The Monthly Dapivirine Ring: Frequently Asked Questions 2020 [Available from: https://www.ipmglobal.org/sites/default/files/media_block_files/ring_public_qa_dec_2020.pdf.

- 8.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, Bekker L-G, Gama C, Gill K, et al. Safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Partnership for Microbicides. Final Results of Open-label Study of IPM’s Dapivirine Vaginal Ring Show Increased Use and Suggest Lower Infection Rates Compared to Earlier Phase III Study 2019 [updated 11–14 June 2019. Available from: https://www.ipmglobal.org/content/final-results-open-label-study-ipm%E2%80%99s-dapivirine-vaginal-ring-show-increased-use-and-suggest.

- 11.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Mgodi NM, Mayo AJ, Szydlo DW, Ramjee G, et al. Safety, uptake, and use of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV-1 prevention in African women (HOPE): an open-label, extension study. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(2):e87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown ER, Hendrix CW, van der Straten A, Kiweewa FM, Mgodi NM, Palanee-Philips T, et al. Greater dapivirine release from the dapivirine vaginal ring is correlated with lower risk of HIV-1 acquisition: a secondary analysis from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(11):e25634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Partnership for Microbicides. Dapivirine Ring [Available from: https://www.ipmglobal.org/our-work/our-products/dapivirine-ring#Results%20presentations.

- 14.European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval of the dapivirine ring for HIV prevention for women in high HIV burden settings Online [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/24-07-2020-european-medicines-agency-(ema)-approval-of-the-dapivirine-ring-for-hiv-prevention-for-women-in-high-hiv-burden-settings.

- 15.WHO recommends the dapivirine vaginal ring as a new choice for HIV prevention for women at substantial risk of HIV infection Online: World Health Organization; 2021. [Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-01-2021-who-recommends-the-dapivirine-vaginal-ring-as-a-new-choice-for-hiv-prevention-for-women-at-substantial-risk-of-hiv-infection#:~:text=WHO%20today%20recommended%20that%20the,the%20risk%20of%20HIV%20infection.

- 16.Giguere R, Lentz C, Kajura-Manyindo C, Kutner BA, Dolezal C, Buthelezi M, et al. Counselors’ acceptability of adherence counseling session recording, fidelity monitoring, and feedback in a multi-site HIV prevention study in four African countries. AIDS Care. 2020;32(sup1):19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery ET, Stadler J, Naidoo S, Katz AWK, Laborde N, Garcia M, et al. Reasons for nonadherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring: narrative explanations of objective drug-level results. AIDS. 2018;32(11):1517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naidoo K, Mansoor LE, Katz AW, Garcia M, Kemigisha D, Morar NS, et al. Qualitative perceptions of dapivirine vaginal ring adherence and drug level feedback following an open-label extension trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery ET, Katz AWK, Duby Z, Mansoor LE, Morar NS, Naidoo K, et al. Men’s sexual experiences with the dapivirine vaginal ring in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(6):1890–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard Solai ST, Nadia Sutton, Dennis Kembero, Fiona Mahiaini, editor Dapivirine Vaginal Ring: End-user Assessment | Segmentation | Messaging | Positioning Amongst Women End-Users and Male Influencers. International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa (ICASA); 2–7 Dec 2019; Kigali, Rwanda. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez A, Loar R, Kramer AE, Garnett GP. Reaching and targeting more effectively: the application of market segmentation to improve HIV prevention programmes. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;4(4):e25318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton J, Blackburn M, Breckenridge JP, Hallowell N, Farrington C, Rankin D. Ambassadors of hope, research pioneers and agents of change-individuals’ expectations and experiences of taking part in a randomised trial of an innovative health technology: longitudinal qualitative study. Trials. 2019;20(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saethre E, Stadler J. Malicious whites, greedy women, and virtuous volunteers: negotiating social relations through clinical trial narratives in South Africa. Med Anthropol Q. 2013;27(1):103–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naidoo S, Morar N, Ramjee G. Participants as community-based peer educators: Impact on a clinical trial site in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr J Sci. 2012;109:01–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz AWK, Naidoo K, Reddy K, Chitukuta M, Nabukeera J, Siva S, et al. The power of the shared experience: MTN-020/ASPIRE trial participants’ descriptions of peer influence on acceptability of and adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia M, Luecke E, Mayo A, Scheckter R, Ndase P, Kiweewa FM, et al. Impact and experience of participant engagement activities in supporting dapivirine ring use among participants enrolled in the Phase III MTN-020/ASPIRE study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chitukuta M, Duby Z, Katz A, Nakyanzi T, Reddy K, Palanee-Phillips T, et al. Negative rumours about a vaginal ring for HIV-1 prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2019;21(11):1209–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinead Delany-Moretlwe FS, Sheila Harvey. Evidence Brief: The EMPOWER study: An evaluation of a combination HIV prevention intervention including oral PrEP for adolescent girls and young women in South Africa and Tanzania 2018 [Available from: http://strive.lshtm.ac.uk/system/files/attachments/EMPOWER%20brief_0.pdf.

- 29.Delany-Moretlwe S, Lombard C, Baron D, Bekker L-G, Nkala B, Ahmed K, et al. Tenofovir 1% vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection in women in South Africa (FACTS-001): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron D, Scorgie F, Ramskin L, Khoza N, Schutzman J, Stangl A, et al. “You talk about problems until you feel free”: South African adolescent girls’ and young women’s narratives on the value of HIV prevention peer support clubs. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Stadler J, Hartmann M, Magazi B, Mathebula F, et al. Male partner influence on women’s HIV prevention trial participation and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis: The importance of “Understanding.” AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):784–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Chitukuta M, Reddy K, Woeber K, Atujuna M, et al. Acceptability and use of a dapivirine vaginal ring in a phase III trial. AIDS. 2017;31(8):1159–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann M, Lanham M, Palanee-Phillips T, Mathebula F, Tolley EE, Peacock D, et al. Generating CHARISMA: Development of an intervention to help women build agency and safety in their relationships while using PrEP for HIV prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2019;31(5):433–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartmann M, Palanee-Phillips T, O’Rourke S, Adewumi K, Tenza S, Mathebula F, et al. The relationship between vaginal ring use and intimate partner violence and social harms: formative research outcomes from the CHARISMA study in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2018. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson E, Wagner D, Palanee T, Mathebula F, Hartmann M, Tolley E, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of CHARISMA: Results of a Pilot Study Addressing Relationship Dynamics, Intimate Partner Violence and Microbicide Use for HIV Prevention. HIV Research for Prevention (HIV R4P) 21–25 Oct 2018; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available as required.