Abstract

While liver transplantation (LT) is a life-saving measure for individuals with end-stage liver disease, the peri-operative management may be challenging in individuals with concomitant sickle cell disease (SCD). We report a case of a 50-year-old man with SCD genotype SC (HbSC) and cirrhosis secondary to autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) who underwent LT. His post-operative course included upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolus (PE), stroke via a patent foramen ovale after a line removal, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Fortunately, he is alive with a functioning graft at 10 months after LT. This case highlights the feasibility of LT in SCD given the support of meticulous multidisciplinary care and the unique aspects of AIH and SCD for LT consideration. .

Introduction

HbSC is generally considered a milder form of SCD.1 However, studies on the natural history of HbSC disease indicate that its underlying pathophysiology still has the potential for severe complications, including hyperviscosity and thrombosis.1-3 The peri-operative management of LT in a patient with HbSC and AIH has not been delineated well in the literature. Here, we describe the clinical course of a HbSC patient with end-stage liver disease from AIH who underwent LT and developed post-operative thrombotic complications.

Case

A 50-year-old man with HbSC and AIH cirrhosis was referred for LT. Before LT, his HbSC was relatively quiescent without frequent pain crises. He experienced pain crisis every 4-5 years, and he often managed his crises with over-the-counter medications without hospitalization. With regards to his liver failure, he had a history of bleeding esophageal varices requiring band ligation and diuretic-controlled ascites without prior spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). AIH was treated with azathioprine and prednisone. He had a remote history of documented stroke and self-reported myocardial infarction (MI) of unclear etiology. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography 2 months prior to LT showed only chronic infarcts in right frontal and parietal lobes, corona radiata, and right and left cerebellum. Left heart catheterization after MI showed mild coronary artery disease without significant obstructive disease. Surgical history included cholecystectomy for gallstone disease. There was no known family history of SCD or liver disease. He was a never smoker. He previously drank 1-2 standard units of alcohol per month, but he stopped consuming alcohol completely after the diagnosis of cirrhosis. He had no history of illicit drug use.

One week prior to LT, he was admitted after developing abdominal pain and melena. An upper endoscopic evaluation of melena revealed four columns of large esophageal varices with red wale signs requiring band ligation. Diagnostic paracentesis revealed SBP with 281 polymorphonuclear cells/mm3. He also developed renal failure during this admission. Model for End-Stage Liver disease (MELD) score increased to 40.

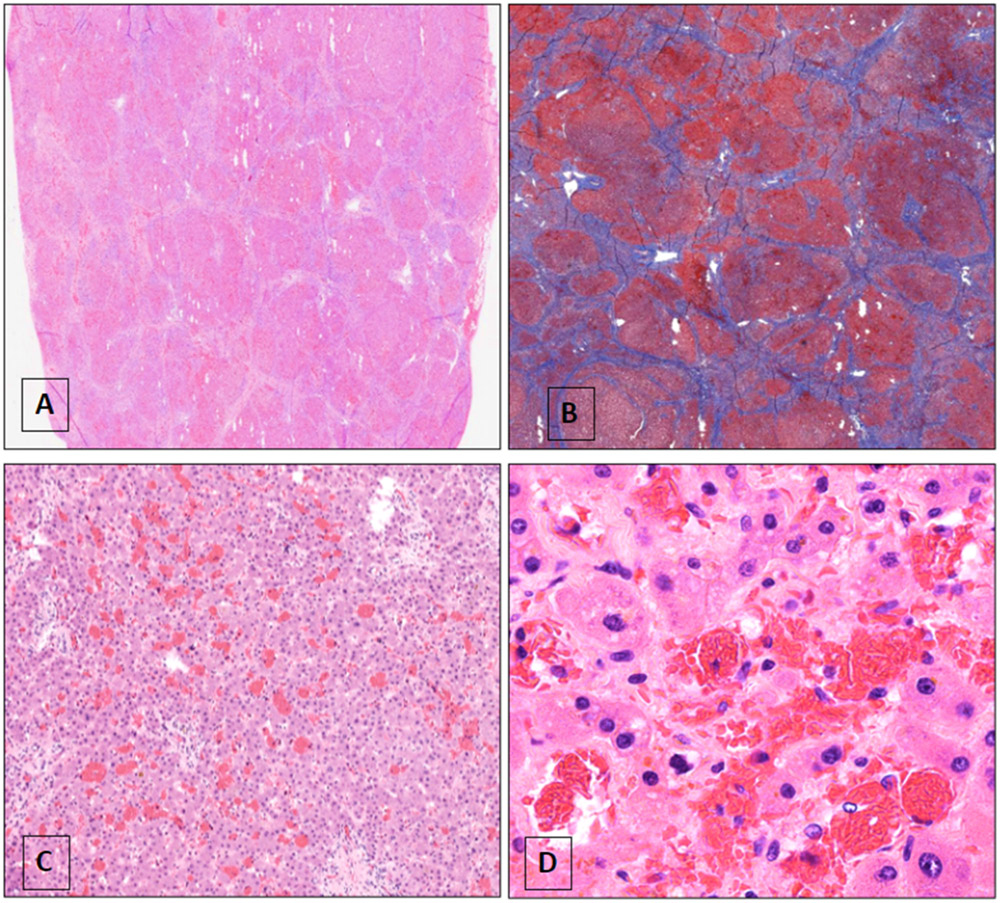

Given the critical illness, the etiology of cirrhosis was carefully revisited. The diagnosis of AIH was made according to the simplified diagnostic scoring system of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Antinuclear antibody was negative, and anti-smooth muscle antibody titer was 1:80. IgG had risen to 3853 mg/dL (the upper limit of normal was 1600 mg/dL). Liver biopsy obtained several months prior to the admission showed cirrhosis with sinusoidal dilation, moderate portal inflammation (lymphocytes and plasma cells), bile ductular reaction, and prominent interface activity. There was no evidence of significant steatosis, stainable iron, or sickle cell hepatopathy (Figure 1). Regarding the HbSC, hemoglobin electrophoresis showing 48.3% hemoglobin S and 44% hemoglobin C confirmed the diagnosis. Dobutamine stress test before LT was unrevealing; carotid artery duplex showed no significant stenosis.

Figure 1.

Liver biopsy several months prior to LT referral.

A. Liver biopsy demonstrating cirrhosis and sinusoidal dilatation (original magnification 40x); B. Trichrome stain confirming cirrhosis; C. Higher magnification showing marked sinusoidal congestion (original magnification 100x); D. Focus of interface activity with abundant plasma cells (arrows) suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis (original magnification 200x)

His biopsy-proven cirrhosis with a history of AIH and HbSC disease was extensively discussed at the LT committee meeting with his hematologists. He was ultimately approved and listed. Shortly after listing, he received a United States Public Health Service standard risk graft from a 34-year-old brain-dead donor. The surgery was performed in the usual “piggy-back” fashion with duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis. Red cell exchange transfusion was performed prior to LT to minimize the peri-operative risks of sickle cell crisis. Microscopic examination of the explanted liver showed cirrhosis with marked cholestasis, sinusoidal congestion, and sickled erythrocytes. (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Gross photograph of explanted liver exhibiting nodularity

Figure 3.

Microscopic views of explanted liver

A. Low power magnification of section of the explanted liver with nodularity (original magnification 40x); B. Trichrome stain confirming cirrhosis; C. The cirrhotic liver is remarkable for sinusoidal dilation and congestion (original magnification 100x); D. Higher magnification shows the congested sinusoids with intrasinusoidal red cell sickling (original magnification 200x)

He had a prolonged recovery. He developed a small non-obstructive PE after removal of central venous catheter from a clot burden at the tip of the catheter. He also developed seizures and altered mental status. Brain MRI showed PRES and bilateral supratentorial cortical and subcortical infarct and hemorrhage. We thus switched his immunosuppression from tacrolimus to everolimus to prevent further neurological complications. Transthoracic echocardiogram with agitated saline revealed a patent foramen ovale, likely contributing to bilateral strokes after removal of the catheter. He continued to receive red cell exchange transfusion with the goal of maintaining a combined HbS and HbC fraction <30%. He eventually recovered and was discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility then home. Currently, he is alive at 10 months post-transplantation and continues to follow up in the outpatient setting with ongoing monthly red cell exchange transfusions. His graft function remains excellent.

Discussion

HbSC patients have a milder form of SCD, but they can exhibit a moderately severe phenotype, especially in the perioperative setting like our patient. HbSC results in an increased risk of thromboembolic events due to hypercoagulable state from sickling.3-5 An autopsy study of 44 patients with HbSC revealed that the second leading cause of death was thromboembolic complications including papillary necrosis, venouc thromboembolic disease, and arterial thrombotic accidents. In a different study of 179 adult HbSC patients, thrombotic complications including papillary necrosis, venous thromboembolic disease, and arterial thrombotic accident occurred in 13% of patients. Retinopathy and sensorineural hearing disorders presented in 70% and 29% of patients, respectively, likely a chronic sequelae of blood hyperviscosity.2

Our patient also experienced significant neurological complications after LT in the form of PRES and seizures. PRES, in particular, has become an increasingly recognized complication in SCD both with and without transplantation and immunosuppression.6 A single-center retrospective analysis of 21 SCD pediatric and adult patients who underwent LT demonstrated that this cohort suffered from a high proportion of neurological complications, with 76% having delirium, seizures, or PRES.7 Patients with SCD are generally more susceptible to neurotoxicity due to endothelial dysfunction and SCD-related vasculopathy from chronic hemolysis, ischemia, and sickling damage.6,8 In addition, the adverse effects of tacrolimus in the forms of vasoconstriction and proinflammatory effect on endothelium only exacerbate the manifestation of neurological complications in post-transplant patients. High index of suspicion for diagnosis and aggressive management and prevention of these complications may minimize the morbidity and mortality in SCD patients undergoing LT.

Our patient had SCD and AIH. The coexistence of SCD and AIH has primarily been described in the pediatric literature. It is hypothesized that the defective activation of the alternate complement pathway in SCD increases the risk of developing autoimmune diseases. A retrospective review at a single center reported that 13 of 77 pediatric patients (17%) with SCD and hepatic dysfunction were diagnosed with autoimmune liver disease, which included AIH and AIH-sclerosing cholangitis. None of the patients in this cohort had complications of cirrhosis at the time of presentation. Eleven patients (85%) had sickle cell disease (HbSS), and 2 patients (15%) had HbSC. 9 Diagnosing autoimmune liver disease in SCD can be challenging due to symptomatic and biochemical overlap that mimic sickle cell hepatopathy. Although previously thought rare, the reported prevalence of autoimmune liver disease in SCD has been increasing in the last two decades, suggesting that autoimmune liver disease is much more prevalent in the SCD population. 9

The interpretation of liver biopsies and explant in SCD patients, including HbSC, demands additional consideration because the degree of intrasinusoidal sickling increases ex vivo after incubation and processing of the sample. In a study by Omata et al., 5 patients with HbSS had liver biopsy that showed the mean sickled cell count of 9.9 ± 7.9% before incubation in formaldehyde, which increased to the mean sickled cell count of 47.9 ± 24.4% after incubation (p<0.01).10 A post-incubation increase in the proportion of intrasinusoidal sickling was also observed in HbSC and sickle cell trait, but not in normal hemoglobin (i.e., HbAA). The degree of sickling was not correlated with the degree of elevation in aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase.10 Our patient’s explant showed intrasinusoidal sickling, but it may not have been prominent in vivo before the hepatectomy.

In conclusion, LT in SCD remains a challenge but is feasible in a subset of SCD patients, including those with HbSC. Our case highlights that AIH in SCD may be underdiagnosed, and the sickling features on liver biopsy or explant can be overestimated during specimen processing. Despite a more protracted post-operative recovery due to thrombotic and neurologic complications, our patient eventually overcame these adversities and is alive with a functional graft at 10 months after LT. Understanding the unique features of AIH and SCD, LT in our patient was overall successful.

Acknowledgements/Funding:

We gratefully acknowledge funding by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AA028297 (Chen) and Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Program in Liver Disease – The Americas (Chen). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and other sponsors.

Abbreviations:

- AIH

Autoimmune hepatitis

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- HbSC

Hemoglobin SC disease

- LT

Liver transplantation

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- PRES

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- SCD

Sickle cell disease

- SCH

Sickle cell hepatopathy

- SBP

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1.da Guarda CC, Yahouédéhou S, Santiago RP, et al. Sickle cell disease: A distinction of two most frequent genotypes (HbSS and HbSC). PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0228399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.François L, Nadjib H, Katia Stankovic S, et al. Hemoglobin SC disease complications: a clinical study of 179 cases. Haematologica. 2012;97(8):1136–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagel RL, Fabry ME, Steinberg MH. The paradox of hemoglobin SC disease. Blood Rev. 2003;17(3):167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pecker LH, Schaefer BA, Luchtman-Jones L. Knowledge insufficient: the management of haemoglobin SC disease. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(4):515–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu TT, Nelson J, Streiff MB, Lanzkron S, Naik RP. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in adults with hemoglobin SC or Sβ(+) thalassemia genotypes. Thromb Res. 2016;141:35–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solh Z, Taccone MS, Marin S, Athale U, Breakey VR. Neurological PRESentations in Sickle Cell Patients Are Not Always Stroke: A Review of Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(6):983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levesque E, Lim C, Feray C, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with sickle cell disease: possible but challenging-a cohort study. Transpl Int. 2020;33(10):1220–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurtova M, Bachir D, Lee K, et al. Transplantation for liver failure in patients with sickle cell disease: challenging but feasible. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(4):381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jitraruch S, Fitzpatrick E, Deheragoda M, et al. Autoimmune Liver Disease in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. J Pediatr. 2017;189:79–85.e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omata M, Johnson CS, Tong M, Tatter D. Pathological spectrum of liver diseases in sickle cell disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31(3):247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.