Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether sociodemographic differences exist among female patients accessing fertility services post-cancer diagnosis in a representative sample of the United States population.

Methods

All women ages 15–45 with a history of cancer who responded to the National Survey for Family Growth (NSFG) from 2011 to 2017 were included. The population was then stratified into 2 groups, defined as those who did and did not seek infertility services. The demographic characteristics of age, legal marital status, education, race, religion, insurance status, access to healthcare, and self-perceived health were compared between the two groups. The primary outcome measure was the utilization of fertility services. The complex sample analysis using the provided sample weights required by the NSFG survey design was used.

Results

Five hundred forty-five women reported a history of cancer and were included in this study. Forty-three (7.89%) pursued fertility services after their cancer diagnosis. Using the NSFG sample weights, this equates to a population of 161,500.7 female cancer survivors in the USA who did utilize fertility services and 1,811,955.3 women who did not. Using multivariable analysis, household income, marital status, and race were significantly associated with women utilizing fertility services following a cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

In this nationally representative cohort of reproductive age women diagnosed with cancer, there are marital, socioeconomic, and racial differences between those who utilized fertility services and those who did not. This difference did not appear to be due to insurance coverage, access to healthcare, or perceived health status.

Keywords: Fertility preservation, Oocyte cryopreservation, Embryo banking, Racial disparity

Introduction

Improved cancer treatment modalities have led to increased survival rates of reproductive age cancer patients. As of 2019, there were over one million female cancer survivors of reproductive age [1]. In other words, 6% of today’s female population of childbearing age consists of cancer survivors [2]. Successful survivorship involves maintaining a high quality of life after cancer treatment, and studies have repeatedly established the link between infertility and diminished quality of life indicators [3, 4]. In an era where women who choose to reproduce continue to delay motherhood, there has been an inevitable increase in women diagnosed with cancer before completing, or even beginning, their families [5, 6]. This problem is compounded by the age-related decline in fertility confronting all women.

With recent advances in the field of assisted reproductive technology (ART), an increasing number of girls and women facing a cancer diagnosis have been provided the opportunity to preserve their fertility prior to undergoing gonadotoxic treatment or gonadectomy. However, it is apparent that advances in the field of fertility preservation have outpaced access. A recent large study conducted in reproductive age women diagnosed with lung, breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer who underwent both chemotherapy and surgery found that the rate of fertility preservation within 30 days of treatment increased from 1.0% in 2009 to just 4.6% in 2016 [7]. Multiple studies have sought to identify barriers to fertility preservation, including problems pertaining to physician referral, lack of information, concerns regarding the risk of the procedure, cost, and cultural, personal, and/or religious beliefs [8, 9]. The directive of these studies provides an essential stimulus for expanding access and utilization of fertility services; however, there still exists a large population of reproductive age cancer survivors who did not preserve their fertility prior to treatment.

Spontaneous conception for cancer survivors may be difficult or inaccessible, as it has been shown that a disproportionate number of survivors attempting to conceive after cancer treatment require the use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [10, 11]. However, pregnancy is still possible [12–14]. Though childhood cancer survivors had a slightly increased time to pregnancy, nearly two-thirds of those with clinical infertility eventually reported a pregnancy [11]. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to recognize that a history of cancer treatment does not preclude women from achieving pregnancy, and early referral to a fertility specialist will optimize success.

Multiple studies have observed sociodemographic and cultural disparities both in general infertility care [15–17] and in the utilization of fertility preservation services [12, 18]. We hypothesize that similar sociodemographic trends exist among patients with a history of cancer; however, limited data exist on sociodemographic differences among female cancer survivors. To address this gap in the literature, we used the National Survey for Family Growth to assess whether certain sociodemographic factors are associated with the use of fertility treatment among women diagnosed with cancer on a national scale. Results of this study can be used to guide future studies aimed at identifying modifiable barriers to access to improve the utilization of fertility among cancer survivors.

Materials and methods

National survey for family growth design

This study is an analysis of the responses of female participants in the National Survey for Family Growth. The National Center for Health Statistics has conducted the NSFG in 10 waves every 3–7 years since 1973 [13]. The study is performed by in-person structured interviews with a sample of men and women designed to provide nationally representative data on topics related to family growth. One of the goals of the survey is to capture information on the use of infertility services by the United States’ non-institutionalized civilian population. Participants are recruited from 110 diverse sampling sites throughout the country, oversampling Blacks, Hispanics, and teenagers in order to enhance the accuracy of data related to minority populations. The raw data can be transformed into national estimates using a validated methodology [13]. This transformation is performed by applying sampling weights that alter the contribution of each participant’s responses in a way that the demographics of the resulting cohort match those of the national census at the time the data was collected. A detailed explanation of NSFG sample weighting has been published [13]. In brief, a respondent’s sample weight reflects the number of people in the population that she represents. The sample weights are adjusted to account for the probability of selection, the differential response rates, and coverage rates, as well as to the U.S. Census Bureau estimates of the number of persons in age-sex-race- ethnicity subgroups [13]. We used responses provided by women in the 2011–2013, 2013–2015, and 2015–2017 waves of the survey, as these waves asked the most comprehensive set of questions regarding the use of infertility services.

Sample population

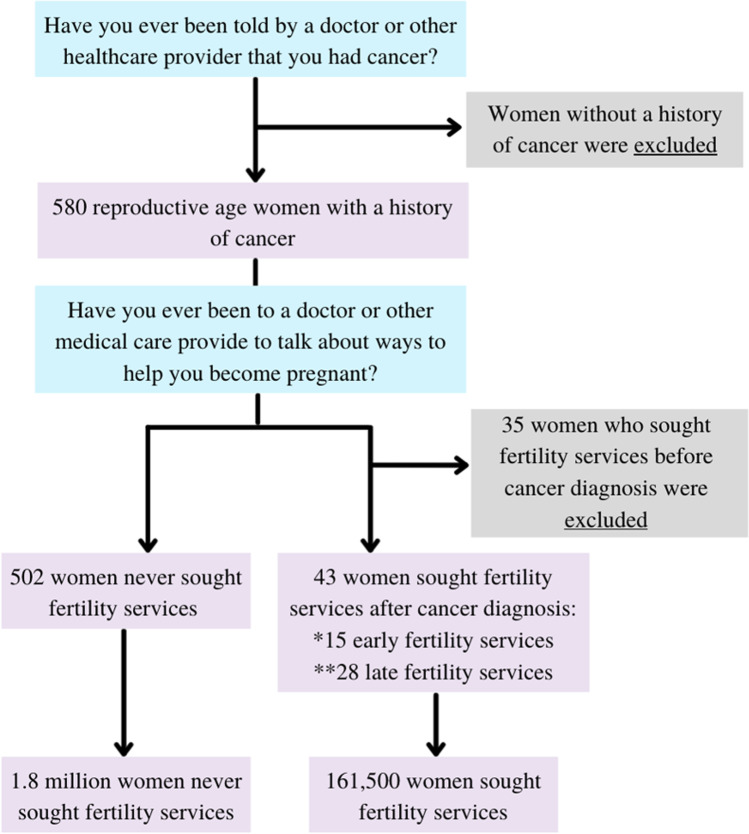

The study only included the women who responded that they had been diagnosed with cancer. We then compared the demographic and healthcare utilization characteristics between those who did and did not seek infertility services. A respondent was considered to have sought infertility services if she responded yes to the survey question, “Have you ever been to a doctor or other medical care provider to talk about ways to help you become pregnant?” Women who were diagnosed with cancer after seeking infertility services were excluded from this study. Figure 1 illustrates the inclusion and exclusion criteria utilized to generate the sample population. The questions included in the figure reflect the exact wording of the question used in the NSFG survey. Demographic variables included patient age at survey, patient age at cancer diagnosis, poverty level, legal marital status, race, religion, education, and health insurance status. The choice of which demographic variables to include in the model was influenced by prior studies as well as what was available from the NSFG. Healthcare utilization characteristics include a usual place for healthcare and health status. A respondent was considered to have a usual place for healthcare if she answered yes to the question, “Is there a place that you usually go to when you are sick or need advice about health?” Health status was assessed with the question, “In general, how is your health? Would you say it is…” with the choices: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor. Healthcare utilization characteristics were included in the statistical analysis to control for differences in health outcomes, considering the wide spectrum of cancer, diversity of treatment modalities, and variability among residual effects.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion criteria

The survivors who sought infertility services were further stratified into 2 groups using their reported age at cancer diagnosis and reported age at the utilization of infertility services. Women who reported utilization of fertility services at the same age as her cancer diagnosis were coded as “early fertility preservation”; those who reported utilization of fertility services greater than 1 year after her cancer diagnosis were coded as “late fertility services.” Statistical analysis comparing these 2 groups was limited by small sample size.

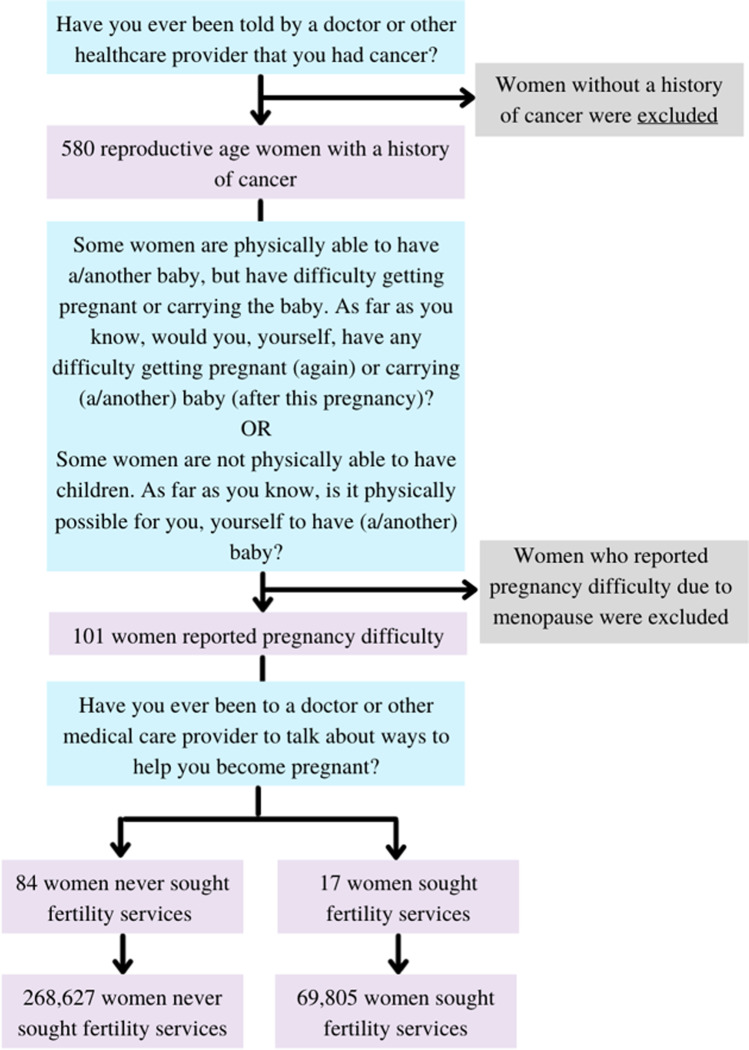

A subgroup analysis was then performed by only including those who additionally reported problems having a child. A respondent was considered to have problems getting pregnant if she reported difficulty getting pregnant or carrying a baby or if she reported that it was not physically possible for her to have a baby. In response to, “What is the main reason it is impossible for you to have a baby in the future?” respondents were given the choices: (1) problems with ovulation; (2) problems with uterus, cervix, or fallopian tubes; (3) other illnesses or treatment for other illness such as cancer; or (4) menopause. As each of the first three answers was eligible for selection if the subject underwent fertility compromising surgery or chemotherapy, it left natural menopause as most fitting for the last answer. Therefore, women who reported that it was physically impossible to have a baby due to menopause were excluded from the analysis. Within this subgroup, we then compared the demographic and healthcare utilization characteristics of those who did and did not seek infertility services. Figure 2 illustrates the inclusion and exclusion criteria utilized to generate the subgroup population. The questions included in the figure reflect the exact wording of the question used in the NSFG survey.

Fig. 2.

Inclusion criteria for subgroup analysis

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included chi-square for comparison of categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis H test for comparisons of our non-parametric continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp) using the complex sample analysis and the sample weights provided on the NSFG website. SPSS requires the user to make a complex analysis plan, which uses the sample weight variables as inputs to generate population estimates. Multivariate logistic regression was then performed to generate a model assessing demographic predictors of whether the woman chose to preserve her fertility. Statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

Results

Overall, 580 reproductive age women reported a history of cancer. Thirty-five women accessed fertility services before their cancer diagnosis and were excluded. Of the 545 women included in this study, 43 (7.89%) utilized fertility services after their cancer diagnosis. Using the NSFG sample weights, this equates to a population of 161,500.7 female cancer survivors in the USA who did utilize fertility services and 1,811,955.3 women who did not utilize fertility services. Fifteen (34.9%) of those who accessed fertility services did so within 1 year of diagnosis which was 2.58% of all women with a history of cancer. The average age of women included in this study was 35.1 (34.2–35.9) years old. The average age at cancer diagnosis was 26.1 (25.0–27.3). Overall, 76% of the sample population identified as non-Hispanic White, 11.3% as Hispanic, 8.1% as Black, and 4.6% as non-Hispanic other. This compares to the US population in which 60.1% identified as non-Hispanic White, 18.5% as Hispanic, 13.4% as Black, and 10.2% as non-Hispanic other [14]. The average income was 256.8% of the poverty level. The majority of respondents self-identified as Protestants (53.8%), followed by non-religious (23.5%). Additionally, most respondents were married (43.9%) and in terms of education level had attended at least some college (61.5%). Table 1 shows the population demographics by whether fertility services were utilized. In multivariate analysis, socioeconomic status, marital status, and race were found to be statistically significant predictors of women utilizing fertility services following a cancer diagnosis (Table 1). Women with higher income were more likely to pursue fertility services (OR 1.06, CI 1.03–1.10). Women who were married were more likely than those who were divorced/separated (OR 0.18, CI 0.07–0.49) or never married (OR 0.20, CI 1.03–1.10) to pursue fertility services. Hispanic (OR 0.32, CI 0.06–1.91) and non-Hispanic other (OR 0.18, CI 0.01–2.49) were less likely to utilize fertility services. Age (p = 0.941), age at cancer diagnosis, religion, and education level were not found to be statistically significant predictors of fertility service use. In terms of healthcare, having insurance, having a usual place to access healthcare, and having good self-perceived health were also not statistically significant predictors of utilization of fertility services.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of female cancer survivors who have and have not used infertility services with univariate with univariate and multivariate analysis

| No infertility service utilization | Infertility service utilization | Univariate P-value | Multivariate P-value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female cancer survivors, n | 502 | 43 | |||

| Overall population estimates, n | 1,811,955.3 | 161,500.7 | |||

| Age, years | 34.9 (34.0–35.8) | 36.9 (34.2–39.5) | 0.221 | 0.941 | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) |

| Age at cancer Dx, years | 26.1 (24.9–27.3) | 27.1 (22.1–32.1) | 0.693 | 0.773 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) |

| Income, % of poverty level | 244.11 (214.7–273.6) | 399.5 (337.9–461.1) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) |

| Marital status, % | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Married | 40.4 (33.1–48.1) | 83.4 (68.3–92.1) | Reference | ||

| Divorced/separated | 25.9 (19.5–33.5) | 5.4 (1.8–14.8) | 0.18 (0.07–0.49) | ||

| Never married | 33.7 (27.8–40.2) | 11.2 (5.0–23.4) | 0.20 (0.07–0.56) | ||

| Race, % | < 0.001 | 0.018 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 75.5 (68.4–81.5) | 80.8 (58.8–92.6) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 12.1 (8.2–17.6) | 2.4 (0.5–10.0) | 0.324 (0.06–1.91) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7.4 (5.3–10.2) | 15.3 (6.0–34.0) | 2.60 (0.90–7.49) | ||

| Non-Hispanic other | 4.9 (1.9–12.0) | 1.4 (0.2–10.1) | 0.18 (0.01–2.49) | ||

| Religion, % | 0.137 | 0.195 | |||

| No religion | 24.6 (19.0–31.3) | 10.7 (4.6–23.1) | Reference | ||

| Catholic | 16.8 (11.9–23.1) | 8.7 (3.0–22.4) | 0.84 (0.25–2.80) | ||

| Protestant | 51.7 (43.9–59.5) | 76.7 (55.6–89.6) | 3.62 (1.11–11.77) | ||

| Other religions | 6.8 (4.0–11.5) | 3.9 (0.7–18.6) | 1.25 (0.17–9.07) | ||

| Education, % | 0.035 | 0.803 | |||

| Less than high school | 19.1 (14.2–25.1) | 5.2 (1.7–14.6) | Reference | ||

| High school | 21.5 (15.6–28.8) | 10.4 (3.8–25.4) | 1.60 (0.40–6.45) | ||

| Some college or more | 59.4 (52.0–66.5) | 84.4 (65.7–93.9) | 1.51 (0.26–8.63 | ||

| Usual place for healthcare, % yes | 93.0 (89.4–95.5) | 95.8 (83.2–99.0) | 0.52 | 0.67 | 1.36 (0.32–5.76) |

| Health status, % | 0.089 | 0.907 | |||

| Excellent/very good | 50.8 (44.0–57.6) | 71.5 (47.9–87.2) | Reference | ||

| Good/fair/poor | 49.2 (42.4–56.0) | 28.5 (12.8–52.1) | 1.04 (0.48–2.24) | ||

| Health insurance status, % | 0.083 | 0.393 | |||

| Private insurance | 56.6 (49.2–63.6) | 80.6 (62.6–91.2) | Reference | ||

| Medicaid | 23.6 (18.3–29.9) | 10.9 (4.8–22.8) | 2.64 (0.73–9.55) | ||

| Medicare/government/military | 4.7 (3.0–7.3) | 4.3 (0.9–18.6) | 1.28 (0.25–6.68) | ||

| Uninsured | 15.1 (10.6–20.9) | 4.2 (1.0–16.0) | 0.84 (0.15–4.72) |

A subgroup analysis was then performed to include only those women who reported problems having a child. Table 2 shows the sample demographics for the subgroup population. Overall, 101 reproductive age cancer survivors had reported difficulty with pregnancy, 17 (16.8%) accessed fertility services, and 84 (83.2%) did not. Using the NSFG sample weights, this equates to a population of 69,805 women who utilized fertility services and 268,627 women who did not. In both univariate and multivariate analysis, socioeconomic status, marital status, and race were found to be statistically significant predictors of women utilizing fertility services following a cancer diagnosis (Table 2). Women with higher income were more likely to pursue fertility services (OR 1.07, CI 1.02–1.12). Women who were married were more likely than those who were divorced, separated (OR 0.02, CI 0.002–0.21) or never married (OR 0.07, CI 0.02–0.31) to pursue fertility services. Hispanic (OR 0.13, CI 0.02–0.70) women were less likely to utilize fertility services. Age, age at cancer diagnosis, religion, and education level were not found to be statistically significant predictors of pursuing fertility services. In terms of healthcare, having a usual place to access healthcare and good self-perceived health status were also not statistically significant predictors of utilization of fertility services. Of note, health insurance was initially included. It was highly insignificant on univariate analysis, and it did not change the multivariable model.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of female cancer survivors with reported problems with pregnancy who have and have not used infertility services with univariate and multivariate analysis

| No infertility service utilization | Infertility service utilization | Univariate P-value | Multivariate P-value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female cancer survivors with reported problems with pregnancy, n | 84 | 17 | |||

| Overall population estimates, n | 268,627 (190,646–346,608) | 69,805 (58,728–80,882) | |||

| Age, years | 33.1 (31.0–35.2) | 38.0 (37.1–38.9) | 0.065 | 0.795 | 0.98 (0.86–1.13) |

| Age at cancer diagnosis, years | 25.5 (23.8–27.2) | 28.5 (26.6–30.4) | 0.376 | 0.609 | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) |

| Income, % of poverty level | 218.9 (176.6–261.2) | 431.3 (402.4–460.2) | 0.001 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | |

| Marriage, % | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Married | 32.6 (21.2–46.6) | 87.2 (79.1–92.4) | Reference | ||

| Divorced/separated | 33.2 (17.4–54.0) | 1.5 (0.2–11.9) | 0.02 (0.002–0.21) | ||

| Never married | 34.1 (20.5–51.0) | 11.3 (6.8–18.1) | 0.07 (0.02–0.31) | ||

| Religion, % | 0.255 | 0.279 | |||

| No religion | 19.6 (12.9–28.6) | 7.6 (2.0–25.0) | Reference | ||

| Catholic | 23.0 (13.1–37.3) | 6.3 (1.6–21.5) | 1.81 (0.26–12.82) | ||

| Protestant | 56.3 (40.8–70.7) | 84.5 (67.0–93.6) | 7.36 (0.92–58.87) | ||

| Other religions | 1.1 (0.2–4.8) | 1.6 (0.2–11.9) | 0.65 (0.03–16.91) | ||

| Race, % | < 0.001 | 0.048 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.5 (58.9–80.0) | 71.9 (56.1–83.7) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 19.4 (13.2–27.6) | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 0.13 (0.02–0.70) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7.6 (2.3–22.3) | 21.7 (11.2–37.9) | 3.09 (0.46–20.95) | ||

| Non-Hispanic other | 2.4 (0.7–7.7) | 2.8 (0.3–19.7) | 0.34 (0.05–2.45) | ||

| Education, % | < 0.001 | 0.611 | |||

| Less than high school | 24.8 (15.7–36.7) | 4.2 (3.7–4.8) | Reference | ||

| High school | 18.2 (5.6–45.4) | 6.3 (3.7–10.6) | 0.51 (0.12–2.22) | ||

| At least some college | 57 (41.0–71.8) | 89.5 (85.6–92.4) | 0.48 (0.07–3.29) | ||

| Usual place for healthcare, % yes | 96.2 (94.0–97.6) | 95.5 (94.8–96.1) | 0.83 | 0.086 | 0.24 (0.05–1.24) |

| Health status, % | 0.1 | 0.339 | |||

| Excellent/very good | 43.4 (27.5–60.7) | 65.4 (55.8–73.8) | Reference | ||

| Good/fair/poor | 56.6 (39.3–72.5) | 34.6 (26.2–44.2) | 0.57 (0.17–1.87) | ||

| Health insurance status, % | 0.996 | ||||

| Private | 51.4 (36.1–66.4) | 91.9 (81.8–96.6) | |||

| Medicaid | 23.6 (12.7–39.7) | 5.5 (2.3–13.0) | |||

| Medicare/government/military | 0.9 (0.2–4.3) | 2.6 (0.3–17.7) | |||

| Uninsured | 24.1 (10.2–46.9) | 0 |

Overall, the rate of fertility service utilization increased overtime. In the 2011–2013 NSFG survey, 12.8% of women with a history of cancer utilized fertility services. This increased to 13.6% among the 2013–2015 survey cohort and 13.8% from 2015–2017.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of reproductive age women, female cancer survivors differentially utilize fertility services. We found that higher income, being married, and non-Hispanic race were positive predictors of fertility service utilization, while respondent’s age at survey, age at cancer diagnosis, education, religion, insurance status, regular access to healthcare, and self-perceived health were not significant predictors. These findings remained significant predictors among women who explicitly reported difficulty having a child.

This study found that married women were more likely than divorced, separated, or unmarried women to have utilized fertility services. This finding differs from studies examining sociodemographic disparities in fertility preservation. Both Letourneau et al. and Flink et al. found no association between utilization and partner status [19, 20]. It is important to consider that fertility preservation requires one to think about future fertility, regardless of one’s partner status at the time of services, whereas post-treatment services are more likely to be accessed at the time one desires offspring. While the definition of the modern American family continues to evolve, a combination of marital factors, including greater financial stability; increased likelihood of employer-based insurance; increased support for childbearing; the traditional association of marriage and childbearing; and the external pressures of a partner, likely contributes to marriage as a positive predictor of fertility service use in this population. However, it is important to acknowledge that the respondents’ demographic information is from the time of the survey, rather than at the time of cancer diagnosis or post-cancer treatment when decisions to pursue fertility services are made. Though some demographic information is static throughout one’s lifetime, the dynamic nature of marital status makes it more challenging to infer that the respondent’s marital status at the time of the survey is related to her fertility care decisions.

We found that women of higher income were more likely to pursue fertility services, and differences in utilization rates did not appear to be due to insurance coverage. Unfortunately, insurance coverage of fertility services remains inadequate, even for many women with more generous insurance benefits. As of September of 2020, only 8 states specifically required private insurers to cover limited, state-dependent services in the setting of iatrogenic infertility. While some states now cover oncofertility services in their Medicaid plans, this was not the case at the time the survey in this study was administered [21, 22]. Additionally, beyond the high cost of treatment, certain infertility services require that the patient take off substantial time from work for frequent office visits that may require significant travel if the clinic is geographically distant [23]. An estimated 18 million women of reproductive age live in locations with no specialized infertility clinics, while majority of these center are found in states with high median income [23]. Thus, given the limited coverage by insurance, significant cost of such services, and financial sacrifices it demands, it is not surprising that household income would be a factor significantly associated with the use of fertility services [18, 24].

It is important to note that lower income has been associated with poorer outcomes in those diagnosed with cancer, including an increased probability of diagnosis delay, resulting in reduced survival and worsened outcomes [25]. Pregnancy is not without risks; thus, women with worse cancer outcomes may be less likely to consider or be considered for infertility service referral due to the substantial health risks that pregnancy would pose. While preconception counseling and consideration of pregnancy-related risk is important, data suggest that the overall maternal morbidity does not seem to be increased in most pregnancies of cancer survivors and the risk of potential obstetrical complications appears specific to the cancer type [26]. Thus, maternal morbidity should not be a barrier to referral to a reproductive specialist. Even for women whose treatment involved surgical removal of reproductive organs, depending on the organ removed, assisted reproductive options exist, such as harvesting autologous oocytes for use in a third-party gestational carrier or implantation of a donor oocyte [26].

In the examination of race, this study revealed that Hispanic women were less likely to utilize fertility services. This finding is consistent with patterns observed in previous studies on both counseling and the use of fertility preservation [19, 27, 28]. While further studies are needed to determine possible explanations for this finding, it is important to consider the complex interplay between race with structural inequalities in income, systemic racism and discrimination within the medical system, cultural and communication barriers, and one’s own beliefs surrounding infertility, all of which may impact one’s decision and/or ability to pursue fertility services [17, 29]. Previous studies indicate that discriminatory counseling to fertility preservation likely exist [12, 19, 30]. Conscious or unconscious biases among providers may lead healthcare professionals to either fail to counsel women of color or of lower socioeconomic status and/or discourage these women from pursuing fertility services [30]. Women of color have reported that some providers minimize their fertility concerns, exhibit biases about stereotypic hyperfertility in certain racial or ethnic populations, emphasize birth control over procreation, make assumptions about the efficacy of intended parents, and may overall dissuade them from having children [23, 30, 31].

At the patient level, cultural stigmas surrounding infertility and the use of science or technology to conceive, language barriers, cultural emphasis on privacy, and unfamiliarity with the US medical system have been found to dissuade women of certain racial groups from seeking care for infertility [23, 32]. Furthermore, age at first motherhood differs between racial and ethnic groups and may impact the need for fertility services. In this study, the average age at cancer diagnosis among cancer survivors who did not utilize services was 26.1. In 2014, the mean age at first birth among Asian and non-Hispanic White women was older than the national average of 26.3 years old, while the mean age at first birth among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women was younger than the national average [33]. Having children earlier increases the likelihood of completing one’s family before being diagnosed with cancer, thereby reducing the need for fertility. However, despite these trends, a younger mean age at a first birth cannot be used as a surrogate marker for one’s family building choices, which are both personal and complex, and are likely interwoven with many cultural influences. As such, further research on reasons as to why women choose for or against pursuing fertility services is needed.

To control for differential access to healthcare, whether the respondent reported having a usual place to access healthcare was included in multivariate analysis. It was not found to be a significant predictor of fertility service use. It is important to note that this variable is an imperfect proxy for access to healthcare. First, the nature of the question invites the possibility of individual interpretation. Additionally, having a usual place to access healthcare is not synonymous with access to specialty clinics. Among this population of cancer survivors, who likely has increased interfacing with the healthcare system, there is a difference between seeing a doctor in the last year and having the access and/or financial resources to pursue medical aid in having a child. In fact, the variable distribution of obstetrician-gynecologists and specialized infertility centers makes these services disproportionately inaccessible to lower income communities [23]. However, this finding highlights the possibility that access to healthcare is not the problem, but rather the quality of healthcare the racial minority and lower income respondents are receiving. This includes counseling and patient education at the level of the provider. A study assessing the impact of a fertility consultation among patients newly diagnosed with cancer found an almost sixfold increase in utilization of fertility preservation services [20]. These findings highlight the importance of an informed consultation, thereby emphasizing the vital role providers’ play in expanding patient access to specialty services. Referral to a reproductive endocrinologist should be standard practice. Cancer survivors, specifically, should be referred to fertility specialists early due to the higher risk of primary ovarian insufficiency in this population [34].

Today, fertility preservation is a critical component of the multidisciplinary approach to cancer treatment in women of reproductive age, but this has not always been the case. The interest and awareness of oncofertility have grown exponentially in the last 2 decades. The first major American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline about fertility preservation was not published until 2006 [35]. The current study looks at the 2010–2017 waves of the NSFG survey. While this time frame is after the release of the initial guidelines, the average time since cancer diagnosis was 9 years before the survey. It is therefore possible that the lack of national guidelines could explain the overall low rates of fertility service utilization. Though we did not find a statistically significant relationship between year of cancer diagnosis and whether the patient sought fertility services (p = 0.402), we remain hopeful that the widespread shift to modern referral patterns will overall increase rates of fertility preservation.

This study analyzed all women with a reported history of cancer; however, there exists a wide spectrum of cancer, diversity of treatment modalities, and variability among residual effects. This study attempted to control for differences in health outcomes by including the respondent’s self-perceived health in multivariate analysis. Interestingly, one’s self-perceived health did not impact the utilization of fertility services. Additionally, while the survey does ask what type of cancer the respondent had, infertility is more influenced by the treatment that the patient received, rather than the type of cancer the patient was diagnosed with [13]. We attempted to control for this limitation by performing the subgroup analysis on only those who were unable to or reported difficulty with having a child. The subgroup analysis supported our initial findings. Higher income, marriage, and non-Hispanic race were found to be positive predictors of fertility service use, while respondent’s age at survey, age at cancer diagnosis, education, religion, and healthcare utilization characteristics were not significant predictors. This limitation highlights an issue that extends beyond the scope of this study and emphasizes the need for the addition of more comprehensive questions regarding oncofertility in fertility-related databases, such as the NSFG. While this study answers the important question of which cancer survivors are utilizing fertility services using general U.S. data, it is important to note that the pursuit of services is an imperfect proxy for access, which consists of the complex, multi-component infrastructure that is in place to help a patient get to the services she needs. Questions about treatment type, reasons for or against accessing fertility services, and information on rates of infertility counseling and/or referral would allow for further insight into whether the data presented represents a difference in patient preference vs a disparity in access to care at the level of the patient or the provider.

This study stratified survivors by the time frame in which they sought fertility services, with “early fertility services” defined as within one year of diagnosis and “late fertility services” defined as greater than one year. Comparing sociodemographic differences between these 2 groups was limited by a small sample size. However, the rate of “early fertility services” within this study was 2.58%, which is similar to previously reported fertility preservation rates of 4–6% [7, 18]. We acknowledge that the survey does not provide sufficient documentation to identify women who sought care specifically for fertility preservation; however, it does highlight a potential difference in access to care and emphasizes the overall importance of expanding access to fertility preservation, to ultimately limit the number of cancer survivors facing infertility Additionally, it calls for the inclusion of questions surrounding fertility preservation, in order to help pinpoint modifiable factors to make expanding access a reality. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to assess whether sociodemographic differences exist between cancer survivors who underwent fertility preservation vs fertility services post-cancer treatment.

This study has several strengths. It addresses a gap in the literature by determining whether sociodemographic differences exist among cancer survivors pursuing fertility services. It is the first national study, to our knowledge, to examine sociodemographic differences and potential barriers to access in this an often-overlooked population. Additionally, the NSFG survey is independent of insurance type, expanding its generalizability compared to other large health databases that rely on billing data.

This study does have several limitations. The nature of an anonymous survey invites the possibility of both selection and recall bias, and the standard survey design limits the questions that are asked. For example, a respondent was considered to have sought infertility services if she reported having ever been to a doctor or other medical care provider to talk about ways to help her become pregnant. We recognize that this question invites the possibility of personal interpretation. A patient diagnosed with cancer who sought medical care to discuss methods for fertility preservation may not consider that a discussion about ways to help her become pregnant, as she may not want to have gotten pregnant at the time of consultation. This would lead to underreporting of those who sought infertility services following a cancer diagnosis. Alternatively, talking about ways to become pregnant does not conceptually equate to accessing fertility services, which may contribute to overreporting of those who sought infertility services. The NSFG does ask what type of fertility services the respondent received. The majority of respondents reported receiving more than one service, with advice and infertility testing being the most common. However, less than half of the women included in the subgroup analysis responded to the question, limiting its contribution to our results. Additionally, of the thousands of respondents who took the survey, only a small number had a history of cancer, limiting our sample size. Given the small sample size, our study may be underpowered and possibly subject to sampling bias.

Conclusion

Among cancer survivors in the USA, sociodemographic barriers to the utilization of fertility services exist. Higher income, marriage, and non-Hispanic race were found to be positive predictors of fertility service use, while respondent’s age, education, religion, and healthcare utilization were not significant predictors. Further studies are needed to identify specific factors which may impact one’s decision to pursue fertility services, along with counseling and referral rates. This information can help create targeted interventions to expand utilization and ultimately ensure equal opportunities of care to all cancer survivors.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients who completed the National Survey of Family Growth.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancer Treatment & Survivorship: Facts & Figures 2019–2021. In: American Cancer Society. 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures-2019-2021.pdf.

- 2.Pinelli S, Basile S. Fertility preservation: current and future perspectives for oncologic patients at risk for iatrogenic premature ovarian insufficiency. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6465903. doi: 10.1155/2018/6465903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klonoff-Cohen H, Chu E, Natarajan L, Sieber W. A prospective study of stress among women undergoing in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:675–687. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domar AD, Broome A, Zuttermeister PC, Seibel M, Friedman R. The prevalence and predictability of depression in infertile women**Supported by grant 5R03MH45591 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland.††Presented at the Annual Meeting of The American Fertility Society, Orlando, Florida, October 21 to 24, 1991. Fertility and Sterility 1992;58:1158–63. [PubMed]

- 5.Bellieni C. The best age for pregnancy and undue pressures. J Family Reprod Health. 2016;10:104–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurgan T, Salman C, Demirol A. Pregnancy and assisted reproduction techniques in men and women after cancer treatment. Placenta. 2008;29:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selter J, Huang Y, Grossman Becht LC, Palmerola KL, Williams SZ, Forman E et al. Use of fertility preservation services in female reproductive-aged cancer patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:328.e1-.e16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Waimey KE, Smith BM, Confino R, Jeruss JS, Pavone ME. Understanding fertility in young female cancer patients. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:812–818. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones G, Hughes J, Mahmoodi N, Smith E, Skull J, Ledger W. What factors hinder the decision-making process for women with cancer and contemplating fertility preservation treatment? Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:433–457. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton SE, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Ginsburg ES. Female cancer survivors are low responders and have reduced success compared with other patients undergoing assisted reproductive technologies. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton SE, Najita JS, Ginsburg ES, Leisenring WM, Stovall M, Weathers RE, et al. Infertility, infertility treatment, and achievement of pregnancy in female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:873–881. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voigt PE, Blakemore JK, McCulloh DH, Fino ME. Equal opportunity for all? An analysis of race and ethnicity in fertility preservation (FP) in a major American city. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:e139–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groves RM, Mosher WD, Lepkowski JM, Kirgis NG. Planning and development of the continuous National Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2009;1:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau USC. QuickFacts. In, 2019.

- 15.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982–2010. Natl Health Stat Report 2014:1–21. [PubMed]

- 16.Bitler M, Schmidt L. Health disparities and infertility: impacts of state-level insurance mandates. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Missmer SA, Seifer DB, Jain T. Cultural factors contributing to health care disparities among patients with infertility in Midwestern United States. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1943–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Letourneau JM, Smith JF, Ebbel EE, Craig A, Katz PP, Cedars MI, et al. Racial, socioeconomic, and demographic disparities in access to fertility preservation in young women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:4579–4588. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letourneau JM, Smith JF, Ebbel EE, Craig A, Katz PP, Cedars MI, et al. Racial, socioeconomic, and demographic disparities in access to fertility preservation in young women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:4579–4588. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flink DM, Sheeder J, Kondapalli LA. Do Patient characteristics decide if young adult cancer patients undergo fertility preservation? J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6:223–228. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weigel G, Ranji U, Long M, Salganicoff A. Coverage and use of fertility services in the US. In: KFF. 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/coverage-and-use-of-fertility-services-in-the-u-s/.

- 22.Financing UDoHDoMaH. Utah 1115 Primary Care Network Demonstration Waiver. 2021. Retrieved from: https://medicaid.utah.gov/Documents/pdfs/HB192%20Fertility%20Treatment%20Amendments.pdf.

- 23.Medicine TECotASfR. Disparities in access to effective treatment for infertility in the United State: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility. 2021;116(1). 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, McGowan Lowrey K, Eidson S, Knapp C, Bukulmez O. State laws and regulations addressing third-party reimbursement for infertility treatment: implications for cancer survivors. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashing-Giwa KT, Gonzalez P, Lim JW, Chung C, Paz B, Somlo G, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic delays among a multiethnic sample of breast and cervical cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010;116:3195–3204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knopman JM, Papadopoulos EB, Grifo JA, Fino ME, Noyes N. Surviving childhood and reproductive-age malignancy: effects on fertility and future parenthood. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:490–498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman LR, Balthazar U, Kim J, Mersereau JE. Trends of socioeconomic disparities in referral patterns for fertility preservation consultation. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2012;27:2076–2081. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt PE, Blakemore JK, McCulloh D, Fino ME. Equal opportunity for all? An analysis of race and ethnicity in fertility preservation in New York City. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020. p. 1–8. 10.1007/s10815-020-01980-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.White L, McQuillan J, Greil AL. Explaining disparities in treatment seeking: the case of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:853–857. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawson AK, McGuire JM, Noncent E, Olivieri JF, Jr, Smith KN, Marsh EE. Disparities in counseling female cancer patients for fertility preservation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:886–891. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell AV. Beyond (financial) accessibility: inequalities within the medicalisation of infertility. Sociol Health Illn. 2010;32:631–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphries LA, Chang O, Humm K, Sakkas D, Hacker MR. Influence of race and ethnicity on in vitro fertilization outcomes: systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:212.e1-.e17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000–2014. In: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db232.htm.

- 34.Busnelli A, Vitagliano A, Mensi L, Acerboni S, Bulfoni A, Filippi F, et al. Fertility in female cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:96–112. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, Patrizio P, Wallace WH, Hagerty K, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2917–2931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]