Abstract

Problem

Several maternity units worldwide have rapidly put in place changes to maternity care pathways and restrictive preventive measures in the attempt to limit the spread of COVID-19, resulting in birth companions often not being allowed to be present at birth and throughout hospital admission.

Background

The WHO strongly recommends that the emotional, practical, advocacy and health benefits of having a chosen birth companion are respected and accommodated, including women with suspected, likely or confirmed COVID-19.

Aim

To explore the lived experiences of the partners of COVID-19 positive childbearing women who gave birth during the first pandemic wave (March and April 2020) in a Northern Italy maternity hospital.

Methods

A qualitative study using an interpretive phenomenological approach was undertaken. Audio-recorded semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 partners. Thematic data analysis was conducted using NVivo software. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study.

Findings

The findings include five main themes: (1) emotional impact of the pandemic; (2) partner and parent: a dual role; (3) not being present at birth: a ‘denied’ experience; (4) returning to ‘normality’; (5) feedback to ‘pandemic’ maternity services and policies.

Discussion and conclusion

Key elements of good practice to promote positive childbirth experiences in the context of a pandemic were identified: presence of a birth companion; COVID-19 screening tests for support persons; timely, proactive and comprehensive communication of information to support persons; staggered hospital visiting times; follow-up of socio-psychological wellbeing; antenatal and postnatal home visiting; family-centred policies and services.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pandemic, Childbirth, Birth companions, Partners, Experience, Maternity care, Midwifery

Statement of significance.

Problem or issue

Several maternity units worldwide have rapidly put in place changes to maternity care pathways and restrictive preventive measures in the attempt to limit the spread of COVID-19, resulting in birth companions often not being allowed to be present at birth and throughout hospital admission.

What is already known

The World Health Organization [1,2] strongly recommends that the emotional, practical, advocacy and health benefits of having a chosen birth companion are respected and accommodated, including women with suspected, likely or confirmed COVID-19.

What this paper adds

Key elements of good practice that should be adopted across maternity care pathways to promote positive childbirth experiences for women and support persons in the context of a pandemic were identified: presence of a birth companion; COVID-19 screening tests for support persons; timely, proactive and comprehensive communication of information to support persons; staggered hospital visiting times; follow-up of socio-psychological wellbeing; antenatal and postnatal home visiting; family-centred policies and services.

1. Introduction

Evidence shows that having access to trusted emotional, psychological and practical support from a birth companion improves outcomes for both childbearing women and newborns. These include increased maternal satisfaction, higher rate of spontaneous vaginal births, shorter labour duration, decreased medical interventions and better neonatal wellbeing [3,4].

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization [1,2] strongly recommends that the emotional, practical, advocacy and health benefits of having a chosen birth companion are respected and accommodated, including women with suspected, likely or confirmed COVID-19. However contradicting the WHO’s [1,2] position, the presence of a birth partner is often not allowed in several maternity units worldwide, which have rapidly put in place changes to care pathways and restrictive preventive measures in the attempt to limit the spread of COVID-19. This is the case of obstetric units in Italy and in the Lombardy region, where the present study took place. Within a few days of the first COVID-19 diagnosis on the 21 st of February 2020, specific guidelines were issued by the Italian Ministry of Health and the Lombardy Region Health Care Authority with the aim of re-organising hospital and community work and to contain viral spread. As a measure of infection control, birth companions were allowed only for COVID-19 negative women [5,6].

Pregnant women’s concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic are mainly dominated by feelings of fear, loneliness, anxiety and danger with significant worries about the health and wellbeing of elderly relatives, partner and baby in the context of an isolating childbearing experience [[7], [8], [9], [10]]

As part of a larger study conducted by the research team exploring COVID-19 positive women’s childbearing experiences in Italy, the most traumatic events resulted to be the sudden family separation, self-isolation, transfer to an unfamiliar referral centre and the partner not being allowed in hospital, especially during labour and birth [11].

In light of hearing distressing stories from pregnant women and mothers, the restrictions put in place for infection control may have a long-lasting negative psychological impact with a ‘knock-on effect on all members of the family unit’ including partners, who ‘may struggle without having been able to fully interact with the childbearing process, feeling isolated or undervalued’ [12].

A specific study about partners’ experiences in pregnancy during the pandemic, has been conducted by Vasilevski et al. 2021 [13] where support persons reported a feeling of ‘missing out’ from the maternity care experience due to changes in care pathways. They experienced a sense of isolation, psychological distress, reduced bonding with the baby, conflicting information and reduction in the quality of care provided [13]. There is lack of evidence specifically on the experiences of COVID-19 positive childbearing women’s partners, who have been most negatively affected by restrictions of maternity care services.

The aim of this study was therefore to explore the lived experiences of the partners of COVID-19 positive childbearing women who gave birth during the first pandemic wave (March and April 2020) in a Northern Italy maternity hospital.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

A qualitative study using an interpretive phenomenological approach [14,15] was conducted to explore the lived experiences of the partners of childbearing women who tested positive to COVID-19 during the pandemic and gave birth during the first epidemic wave (March and April 2020) in Italy.

2.2. Research setting

The research setting was a Northern Italy maternity hospital (MBBM Foundation at San Gerardo Hospital, Monza) in Lombardy, a Northern Italy region. The hospital was one of five national referral hub centres designated to care for COVID-19 positive childbearing women during the pandemic.

2.3. Sampling strategy, participants and recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was adopted, with COVID-19 positive mothers and their partners recruited as part of a larger study on childbearing women, partners and healthcare professionals’ experiences of birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. The experiences of 22 mothers are reported in a paper previously published by the same research team [11]. All the partners of these women were invited to take part and 14 of them agreed to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria were partners of women who tested positive to COVID-19 during pregnancy and gave birth or were transferred, after consent, in the postpartum period to the research site in the months of March and April 2020. Partners of COVID-19 negative women and not able to undertake the interview in Italian were not eligible to take part. The recruitment process involved identifying eligible participants from the women who had been previously enrolled in a quantitative cohort study on COVID-19 immunity and a qualitative study on COVID-19 positive mothers’ experiences being undertaken in the same research site. The women asked their partners if they were willing to participate; following a positive answer, one of the researchers contacted the potential participant to explain the study, gain informed consent and arrange the interview. All the interviewed partners were male and we will refer to them as ‘participants’ or ‘fathers’ throughout the paper. However, it is acknowledged that family structures vary and we are not working from an assumption of a particular family group. It is anticipated that the findings can be applicable to a range of birth partners/companions.

2.4. Data collection

Data were collected in June 2020, using audio-recorded semi-structured interviews via telephone or video-call (n = 14) conducted by two researchers (AN/SF). Topics for the interview were developed from existing evidence on supporting persons’ childbearing experiences [[16], [17], [18], [19]] and agreed by the research team and an external panel including 2 practicing midwives and 1 obstetrician. The topics explored included the lived experience of being partner of a pregnant woman during the COVID-19 pandemic; the impact of the woman’s COVID-19 infection on themselves, maternal-fetal wellbeing and childbearing event; the experience of childbirth in the light of restrictions and safety measures in place; the access and use of maternity services; the relationship with family, friends and healthcare professionals; concerns and reassuring factors; the parental role after birth.

2.5. Data analysis

All the interviews were anonymised and transcribed verbatim. An interpretive phenomenological thematic data analysis was conducted using NVivo. Transcripts were initially coded line-by-line independently by two researchers (AN/SF) to delineate units of meaning [20]. A second iteration of coding was reviewed jointly by AN/SF/SB and the units of meaning were clustered into themes and sub-themes. Quotes from each interview were identified to support themes/sub-themes and to allow consideration of contradicting data. The final thematic framework was reviewed and agreed by all members of the research team.

2.6. Authors’ background

The authors include three researchers with backgrounds in midwifery (SF/SB/AN) and two with an obstetric background. Bracketing was not implemented, however a midwifery lens was applied to data collection and analysis, with a mindful effort to avoid the bias of pre-conceived views. Openness to participants’ lived experiences and gathered data was upheld. The external panel of healthcare professionals who contributed to the development of the interview topic guide helped in shaping questions around the lived experiences of participants and their families in the context of the ‘revised’ maternity care pathways during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.7. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the required Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study (3140/2020 Ethics Committee Brianza). Information sheets were made available and informed consent was gained prior to every interview. Participation was voluntary and participants were free to decline or withdraw at any time. Scripts and disseminated data were anonymised and audio recordings were stored securely. Due to the research topic being sensitive, strategies were implemented by the researchers to prevent or limit the participants’ emotional discomfort, including asking sensitive and open questions; disclosing the researchers’ background; creating a comfortable environment; remaining flexible in interview timing and accommodating potential interview interruption [21].

3. Findings

The participants’ demographic data are summarised in Table 1 , including age, country, educational level, occupational status and other children. In tables and quotes, participants are referred to as P1, P2, P3 etc. Data on whether the participants were COVID-19 positive or negative are not available as during the first pandemic wave in Italy testing was only offered to childbearing women but not partners or other family members, according to local guidance.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic data.

| Participant | Age | Country | Educational level | Occupational status | Other children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 35 | Italy | Professional school | Working | No |

| P2 | 32 | Italy | High school | Working | No |

| P3 | 40 | Italy | Professional school | Working | Yes |

| P4 | 26 | Italy | High school | Working | No |

| P5 | 37 | Italy | Professional school | Working | No |

| P6 | 31 | Italy | High school | Working | Yes |

| P7 | 40 | Italy | University | Working | Yes |

| P8 | 40 | Italy | University | Working | Yes |

| P9 | 32 | Italy | High school | Working | No |

| P10 | 43 | Italy | High school | Working | No |

| P11 | 49 | Italy | University | Working | Yes |

| P12 | 39 | Italy | High school | Working | Yes |

| P13 | 36 | Italy | Professional school | Working | Yes |

| P14 | 34 | Italy | University | Working | Yes |

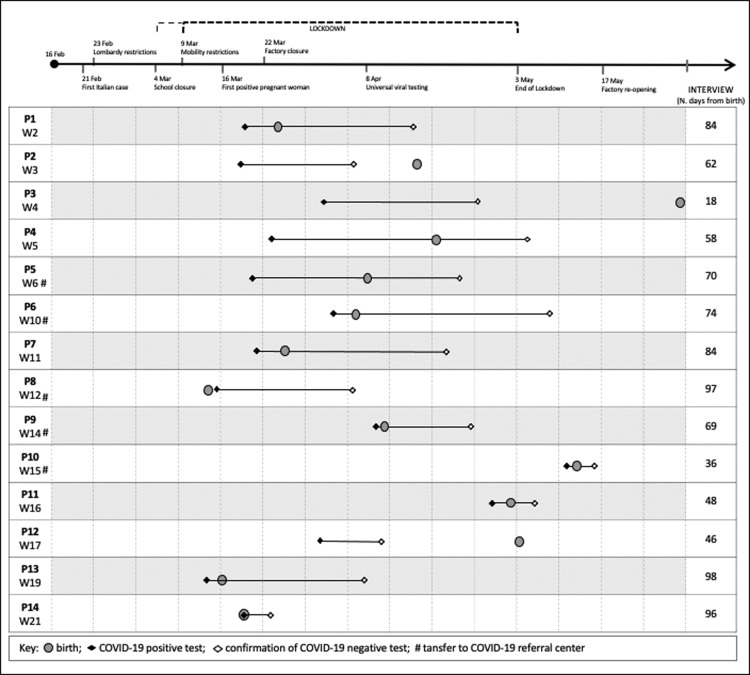

Figure 1 reports the timeline of women and partners’ experiences in the context of measures taken in Italy during COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of women and partners’ experiences in the contest of measures taken in Italy during COVID-19 pandemic.

The findings include five main themes: (1) emotional impact of the pandemic; (2) partner and parent: a dual role; (3) not being present at birth: a ‘denied’ experience; (4) returning to ‘normality’; (5) feedback to ‘pandemic’ maternity services and policies. Themes and sub-themes are reported in Table 2 , including the number of participants and supporting quotes in which these are identified.

Table 2.

Themes and sub-themes.

| Themes and sub-themes | N. of participants | N. of supporting quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Emotional impact of the pandemic | ||

| Confusion, worries and sense of guilt | 14 | 72 |

| Loneliness, melancholy and living in ‘slow-motion’ | 7 | 10 |

| Reassuring factors | 14 | 44 |

| Theme 2: Being partner and parent: a dual role | ||

| Family separation, feeling of ‘emptiness’ and strengthened relationship | 13 | 23 |

| Sense of duty and protection | 12 | 20 |

| Rediscovery of parental role: challenges and benefits | 6 | 8 |

| Theme 3: Not being present at birth: ‘missing out’ | ||

| ‘Deferred’ transition to parenthood | 12 | 19 |

| Waiting for birth | 13 | 29 |

| Contrasting emotions | 10 | 21 |

| First audio and video encounters | 9 | 12 |

| Theme 4: Returning to ‘normality’ | ||

| Family reunification | 10 | 19 |

| Home environment as ‘happy island’ | 10 | 17 |

| Theme 5: Feedback to ‘pandemic’ maternity services and policies | ||

| Information provision | 9 | 28 |

| Being subjected to restrictions | 10 | 16 |

| Lack of family-centred policies | 3 | 8 |

3.1. Theme 1 — emotional impact of the pandemic

3.1.1. Confusion, worries and sense of guilt

The participants described their perception of the COVID-19 pandemic as confused and chaotic due to lack of knowledge on the disease and fast spreading of the virus. The mass-media infodemic, the rapid changes to maternity care pathways, the communication of new rules in regard to accessing healthcare facilities and the related logistic issues were considered as challenging aspects. The fathers found hard to process the news of a positive COVID-19 test result following a mild and ambiguous symptomatology:

It wasn’t very clear, lots of confusing information, fake news on the internet […] so you would watch the news and then again re-check the internet […] very confusing (P3)

It’s been a rapid escalation of events… and you didn’t even have the time to process it all (P12)

The participants expressed worries in regard to the possible effects of contracting the virus on the mother and baby’s health and on their experiences of becoming fathers during the pandemic. They were aware that a positive test would result in them not being able to support their partner and be present during labour and birth. The concerns related to a possible contagion became a sense of guilt when the father was the carrier of the virus within the family unit. Being the one spreading the virus to loved ones (partner, children and parents) was referred to as burdensome and difficult to accept:

I knew it was important to my wife for me to be present, and I also wanted to attend the birth of my second child. So we were very worried that I couldn’t be present at birth (P6)

We were worried about the possibility that she was positive and that she could transmit the virus to the baby (P8)

I am trying to get home the least possible amount of germs hoping not to infect my family anymore […] I have a bit of regret as I was the one infecting them (P3)

The fathers also shared concerns about pragmatic issues, such as initial difficulties in finding essential goods, work instability and doubts on the ability of healthcare services to provide adequate maternity care whilst being overburdened by COVID-19 cases. ‘Living day-by-day’ was the strategy mostly used by the participants and their partners when dealing with difficulties, worries and fears during childbirth in the context of a pandemic:

I was worried about a potential supermarket assault, I was afraid that the hospitals would be full or that they would become off limits as they were admitting all the COVID patients (P7)

3.1.2. Loneliness, melancholy and living in ‘slow-motion’

The participants reported an overall feeling of loneliness due to lockdown restrictions and isolation rules, with significant impact on daily routine and social relationships with the extended family and friends. The fathers recognised the pandemic as influencing and compromising markedly the social networking and experience sharing typically involved in the childbearing event. The participants who had to self-isolate alone at home described feelings of melancholy and sadness, accompanied by sedentary and apathetic behaviours and a perception of living in ‘slow-motion’:

It's been hard to stay at home that long, it was strange to be cut off from the social context especially with the birth of the little one (P7)

Normality was gone, I found myself locked at home like a sedentary who slept, ate and watched tv for a month (P3)

3.1.3. Reassuring factors

Despite the worries and general confusion caused by the pandemic, the participants considered not being high risk subjects for COVID-19 severe symptoms as a reassuring element. Comforting factors during self-isolation and family separation were: receiving information on the low probability of virus’ vertical transmission at birth; the good health of mother and baby; the support received from family and friends, albeit virtual and the forthcoming family reunification. The trust in midwives and healthcare professionals providing compassionate and safe care was also identified as a reassuring aspect easing the fathers’ anxiety and concerns, especially as they were not able to support their partner in person at birth and throughout the hospital stay. The midwives’ presence was perceived as heart-warming and compensating the father’s absence. Sharing the experience a posteriori with the researchers was acknowledged as helpful by most fathers:

The pregnancy was proceeding well, therefore we felt reassured by that. We were aware that the virus would have not been that harmful for the people of our age (P12)

I realised she [the woman] was okay. The midwives, doctors and other healthcare professionals cared for her. This was very reassuring (P8)

It’s been so helpful talking about it today and I feel almost like crying to be honest. I’ve never managed to cry during the past months […] I’ve kept it all in (P5)

3.2. Theme 2 — being partner and parent: a dual role

3.2.1. Family separation, feeling of emptiness and strengthened relationship

The participants described the forced separation from their partner as a challenging, negative and difficult experience, often occurring abruptly and unexpectedly. When recounting the family separation, the fathers referred to the physical places involved (hospital versus home), key events happening whilst apart (labour, birth and the first days of the newborn) and length of separation (e.g. number of days). The contacts were virtual, mainly via telephone, texts and WhatsApp. The struggle to accept the separation is sometimes accompanied by trying to establish a self-distanced visual contact, for example from the car through the maternity ward’s windows. When this expectation was not met, the fathers reported a sense of emptiness. Despite the difficulties encountered, some participants reported the strengthened relationship with their partner as a positive outcome of the separation:

I didn’t even say goodbye to her. And then I realised I wouldn’t have seen her for at least a week, so it’s been very intense (P7)

We’ve been separated unexpectedly and suddenly. We kept in touch only via phone, text messages and whatsapp until the birth of our daughter (P1)

When my wife came back home and she was still Covid-19 positive, we put in place all the safety measures including using a different bath, sleeping separately, eating separately and self-distancing… it was very hard (P2)

It’s been a bad experience that has left scars, but it’s now gone […] and we are even stronger as a couple (P13)

3.2.2. Sense of duty and protection

The situation of isolation, separation and lack of sharing emphasised in the participants a sense of duty and protection towards their partner who went through birth and the child’s first days of life ‘alone’ and without familiar support alongside the challenges presented by the pandemic. They acknowledged the strains experienced by the mothers and perceived their role of providing practical help, reassurance and emotional support as key:

I would have even sat in a corner, just to support her because she needed support (P6)

I thought my partner needed me to reassure her at emotional level more than anything else (P8)

The sense of duty was also reflected in the men’s attentive and scrupulous behaviour in trying to reduce the possibility of contracting and transmitting the virus to the pregnant woman during the antenatal period, including use of appropriate PPE, showering, hand sanitising, changing clothes and being careful when at work.

From when the pandemic started I have always used face mask, gloves and everything else. And to not infect her [woman] I was very careful also at work (P4)

When I come back from work I have a shower straight away and I change all my clotes (P3)

The participants looked at their partners with esteem and admiration, acknowledging their strength and resilience whilst living a very challenging situation. The women themselves were reported as acting in a reassuring way to ease the fathers’ worries:

I tried to give her strength but she’s always been the one giving me strength (P5)

3.2.3. Rediscovery of parental role: challenges and benefits

The participants who were already fathers of other children, described their parental role during the mother’s absence, including their commitment, tasks and responsibilities. Caring for children full time on their own was reported by the fathers as demanding, challenging and intense. Their role was mainly about managing time, organising activities and explaining the reason for the mother’s absence. They referred to their commitment in keeping the kids busy with activities and games, in order to distract them and alleviate the distress caused by the detachment from the mother and lack of social networking. Feelings of melancholy and loneliness were perceived when recalling the usual synergic and complementary maternal and paternal roles within the family. Although various challenging aspects of the experience were reported, the gratifying benefit of rediscovering their parental role was highlighted, resulting in the father-child relationship being strengthened:

I looked after our older daughter and I’ve been very creative in filling up the days with activities, to make her mother’s absence less heavy. I did concentrate on my paternal role (P7)

Despite my son being super good, it’s been very hard. This experience has strengthened me, my son has even told me I’m a good chef, it was very rewarding (P13)

3.3. Theme 3 — not being present at birth: a ‘denied’ experience

3.3.1. ‘Deferred’ transition to parenthood

Not being present at birth was referred to by fathers using a very strong terminology, including nightmare (P10), mess (P2), disastrous (P3) and bad (P7). They felt a sense of deprivation and that they were not able to live fully a very much desired and hoped for birth experience. Not being able to see the newborn baby at birth was accompanied by a difficult, abstract and almost surreal ‘deferred’ transition to parenthood. The fathers particularly missed the physical connection with their child, including not being able to touch or hold him/her:

The mind frame was not at its best, the birth was a wonderful event but not lived at his fullest (P13)

I said to the midwife ‘I should be the dad but I haven’t seen by baby yet’. It’s not a very pleasant situation, I have a child but can’t see him (P6)

It’s been a bad experience […] I’ve called the maternity ward to have information and they basically told me he was already born (P7)

3.3.2. Waiting for birth

Waiting for birth was described by the participants as nerve-wracking, unpleasant, surreal, adrenaline and lonely. The waiting place was often the hospital car park after having dropped off the COVID-19 positive woman at the hospital entrance and left her with the midwives whilst other fathers were self-isolating at home. When waiting in the car, they recounted the surrounding environment as surreal, almost like a war hospital (P7) with harnessed healthcare professionals, lined up ambulances and sirens.

We said goodbye in the car park, she went in and I stayed out in the car park […] there was a lot of adrenaline despite I was alone in the car (P12)

I was obviously home alone and the waiting was never-ending (P9)

Regardless of the actual short or long duration (few or many hours), the waiting time was perceived as endless and difficult to cope with due to lack of news on the woman and the labour progress. Some participants reported they tried to grasp information (P3) from healthcare professionals and their partner via WhatsApp, especially during early labour:

I’ve been there for two hours, with the phone in my hands trying to understand what was happening (P2)

3.3.3. Contrasting emotions

The participants felt contrasting emotions in regard to their child’s birth going from regret, sadness and anger for not being present to joy, happiness, reassurance and excitement for becoming fathers:

The birth of my daughter… it’s been both a sad and wonderful moment. Sad as I couldn’t be there, but wonderful as my daughter was born. It was emotionally very intense, and let’s say it took away all the negativity (P3)

Some participants were reassured by the hospital facilities, healthcare professionals and midwives caring safely and competently for their COVID-19 positive partners and the fetus/newborn. Others found it hard to identify reassuring elements and worries about having ‘left’ their partner ‘alone’ prevailed, with increased levels of anxiety and apprehension when updates on progress were not communicated timely. The women often reassured the partners by directly providing information on positive progression and on their ability to cope with labour without a birth companion:

In that moment, the midwives were the only reassuring factor… they reassured us (P13)

3.3.4. First audio and video meetings

The ‘deferred’ transition to parenthood was mediated by the birth announcement from healthcare professionals, listening to the first cry through the labour ward walls, video-calls and photos sent by the woman. The first meeting with the newborn was mostly via phone screen and the only possible way to see their child was through video-calls, photos and audios for days. Although they were aware of the situation beforehand, the participants still found the first meeting with the baby as atypical, disappointing and difficult to accept, regretting the fact that they could not hold, cuddle and touch their child:

To be honest I didn’t want to see my daughter for the first time via phone, but then I got very curious (P12)

A very kind midwife let me hear the first cry through the wall as the labour was very close to the external area on the ground floor… so I’ve only had the chance to hear the first cry, that’s it (P10)

I’ve assisted via video call at a little bit of birth but I could only see the ceiling and I could only hear laments for the contractions. I got anxious and I wanted to be there so badly (P5)

3.4. Theme 4 — returning to ‘normality’

3.4.1. Family reunification

The family reunification marked the end of separation and loneliness that characterised the birth experience and represents for the fathers a spectacular (P5) return to normality, where the family status was regained and their parental role was finally accompanied by gradually increased physical contact and care. The family reunification was defined as unique (P12) strong (P7), emotional (P7) and beautiful (P7; P12; P14) but also strange (P7) at the same time, due to it often being mediated by self-distancing, masks and other protective measures in the first few days/weeks:

That was the best moment ever cause I saw them and I held her for the first time, two days after birth […] I think holding your baby for the first time is the most beautiful moment (P3)

3.4.2. Home environment as ‘happy island’

Once reunited, the home environment was perceived as a ‘happy island’ where the family unit was able to share the same physical space and affection towards loved ones. This was perceived as a new beginning in view of adapting to a new ordinary and returning to normality. The self-isolation imposed by the pandemic allowed the fathers to appreciate having more quality bonding time with their partner and child(ren). Some fathers identified having a break from the daily busy routine as a positive aspect that made them being more grateful for the simple things in life, such as cooking, playing and building from scratch with the family:

The most beautiful moment is when you get back home and the family is reunited (P6)

It has allowed us to enjoy some quality family time, cooking, playing, building from scratch. It’s been like a throwback to the 80’s when there was so little and we were grateful for that (P3)

3.5. Theme 5 — feedback to ‘pandemic’ maternity services and policies

3.5.1. Information provision

The information provided by maternity services and healthcare professionals were recognised by the participants as a crucial factor within their experience of becoming fathers. The communication about maternity care pathways and re-organisation of services were mostly clear and comprehensive. Information on the self-isolation’s duration and modality, COVID-19 tests, symptomatology and hospital access were identified as confusing. The woman often acted as intermediary between the partner and the institution in regard to information provision:

My wife received all the information and she was the one leading the situation. I followed her instructions without debating them. She told me what needed to be done and I did it (P11)

The effectiveness of communication from healthcare professionals varied depending on where and when this took place. The fathers criticised the lack of information on the progression of labour and felt excluded in case of hospital transfer, with delayed information provided by the woman rather than the healthcare professionals. They reported attentive, accurate and clear information in case of the newborn’s admission to the neonatal unit, with timely communication on the baby’s health, access to the unit and rules to follow; however, these information were not provided proactively and the fathers had to phone the unit themselves:

At the end I had to call the hospital myself […] If I didn’t call myself I would have probably waited for the call for another five or six hours […] it doesn’t take a lot to call a husband that couldn’t be present (P9)

They kept her always updated on the baby’s health. I would have probably expected some more calls directly from the hospital [rather than us calling them] (P8)

3.5.2. Being subjected to restrictions

The restrictions and rules on self-distancing and isolation imposed at national and local level had a strong impact on the experience of becoming a father. Although the participants understood and conformed to the protective measures put in place for the general population, they found it hard to accept those directly impacting on the childbearing experience. The maternity pathways’ policies and protocols were considered by some fathers as unreasonable and too restrictive, with lack of compassion towards the childbearing event., especially in regard to not being present to labour and birth. Despite them asking the healthcare professionals for an exception to the rules, they allegedly accepted being subjected to the rules and restrictions in place:

There are designated people to manage the pandemic emergency therefore I follow what they tell me to do, if they say stay home I stay home. We faithfully followed what we were told to do (P11)

I tried to ask to the midwives if I could get in [the labour ward] but they didn’t let me in, they said ‘this is the procedure’. I hoped they would be a bit more permissive, I don’t fully understand the rationale (P6)

3.5.3. Lack of family-centred policies

The fathers perceived a lack of family-centred policies within maternity care provision, with no clear information on self-isolation or COVID-19 tests offered to the woman’s family members. The participants suggested that the offer of COVID-19 tests to partners and other children would have improved the overall parental experience and the quality of the relationship with the newborn. For some fathers, the expectation of being safeguarded as family unit was not met:

At the end of the day it was stressful, we said ‘let’s wait another week’ […] how can I hold her [the newborn] if I am not sure I am [COVID-19] negative? There is a need to take care of the whole family and to know where everyone is at in terms of the virus (P14)

4. Discussion

This study explored the lived experiences of the partners of COVID-19 positive women during the first months of the pandemic in Northern Italy and the findings are useful in supporting maternity pathways’ changes and redesign in the light of the pandemic impact on service users’ experiences. This is the second of a series of papers being published by the research team, including COVID-19 positive women’s experiences [11] and healthcare professionals’ perspectives during the first pandemic wave.

The findings highlighted the strong emotional impact of the pandemic on fathers, including confusion, worries, sense of guilt, loneliness, melancholy, emptiness and a feeling of living in ‘slow-motion’, which were accompanied by unmet expectations. Other recent evidence similarly reports that partners and support persons’ feelings of uncertainty, isolation and psychological distress [22,13]. The trust in midwives and healthcare professionals providing compassionate and safe care was identified as a reassuring aspect easing the fathers’ anxiety and concerns. Sharing the experience a posteriori with the researchers was acknowledged as helpful by most fathers, highlighting the need for a family-centred psychosocial wellbeing follow up. The support persons’ psychosocial wellbeing needs to be considered during the pandemic, alongside childbearing women’s follow up suggested by Zanardo et al. [23]

The fathers reported a sense of ‘missing out’ for not being present at birth, throughout the woman’s hospital stay and in the first postnatal days/weeks, with a ‘deferred’ transition to parenthood at the time of family reunification. Being denied the birth experience caused feelings of estrangement to the event and contrasting emotions, from joy to anger and melancholy. Similar findings were reported by Vasilevski et al. [13]. The labouring women we interviewed as part of our larger study also highly suffered from the absence of a birth companion [11]; this reinforces WHO recommendations [24] highlighting labour companionship as one of the standards for improving quality of intrapartum care. Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al. [25] underline the socio-cultural, behavioural hormonal and neural factors developing and interacting during the first 1000 days of becoming a father, stating that ‘the transition to fatherhood is a major developmental milestone for men’. Evidence suggests that the father’s presence at birth has a medium-long term impact on the father-infant bonding, later fathering behaviour and family relationships [26]. Within our study findings, the traditional birth companion’s role involving practical support, emotional reassurance, information provision and advocacy for the woman [4] left room to a shifted model of support. The labouring woman reassured the partner remotely and bridged communication gaps between healthcare professionals and the father/support person.

Women’s partners felt isolated because of the changes in the provision of maternity care during the pandemic, in line with recent findings from Bradfield et al. [22]. The fathers perceived a lack of proactive information provision and family-centred policies, resulting in them being subjected to rules and restrictions without a proper informed decision-making process in place. Support persons should be involved as much as possible in the childbearing event by providing adequate access to proactive, timely, comprehensive and accurate information enabling their participation in the decision-making process. Birth companions should be allowed to be present at labour and birth, with provision of appropriate training on PPE use and movement restrictions [27]. Within the study setting, the companion’s presence during labour and birth was re-implemented from October 2020, in accordance with WHO recommendations [1,2] and the preliminary findings of the present study.

When birth companions’ physical presence at birth is not possible, virtual participation could be considered if requested by the woman/family. The facilitation of the support person’s visits to the woman and baby throughout their hospital stay should be encouraged. More specific recommendations for practice from the study findings are outlined in the conclusion section.

5. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the research include the topic originality in the context of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the first paper exploring partners of COVID-19 positive women who were not allowed to act as birth companions. Although the sample size of this qualitative study was relatively small, the findings and implications for practice are transferable and applicable to similar local, national and international settings needing urgent improvements in the provision of maternity care facing a pandemic emergency. The systematic approach to data collection and analysis increases the validity and credibility of the study.

6. Conclusions and implications for practice

Fathers were negatively impacted by changes in maternity care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations and strategies to ensure fathers, birth companions and support persons’ active involvement in maternity care pathways are urgently required. Critical elements identified by the study findings suggest the following key components of good practice that should be encompassed within maternity care pathways in the context of a pandemic:

-

•

birth companions should be screened for COVID-19 and, if tested negative, allowed to be present at labour and birth irrespective of the woman’s COVID-19 status, with appropriate safety measures and PPE in place;

-

•

the facilitation of support person visits to the woman and baby throughout their hospital stay should be encouraged;

-

•

if the companion has suspected or confirmed COVID-19, arrange for an alternative, healthy birth companion in consultation with the woman;

-

•

when birth companions’ physical presence at birth is not possible, virtual participation could be considered if requested by the woman/family;

-

•

caregivers should provide partners/fathers/support persons/birth companions with timely, proactive and comprehensive communication of information, including maternity care pathways, self-isolation measures, progress of labour, health and wellbeing of mother and baby;

-

•

staggered hospital visiting times for partners/fathers/support persons/birth companions should be arranged to facilitate early family reunification and bonding between parents and baby;

-

•

compassionate support and follow-up for socio-psychological wellbeing should be offered to women and their families;

-

•

partners/fathers/support persons/birth companions should be given the opportunity to ask questions and share concerns/doubts to facilitate their inclusion within the childbearing event and decision-making process;

-

•

midwives should support women and birth companions in drafting a birth plan in order to decrease unmet expectations and increase awareness of different care pathways;

-

•

community midwives should offer antenatal and postnatal home visiting following a continuity of care model when possible, to include partners/fathers/support persons/birth companions as much as possible in the childbearing event, when they are not allowed to access appointments in healthcare facilities with the woman;

-

•

policies and processes excluding partners/fathers/support persons/birth companions during the childbearing event need to be reconsidered and replaced by family-centred policies and services.

The above recommendations should be considered in conjunction with the ones that emerged from women’s experiences [11]. The research team is currently also focusing on other groups experiencing the childbearing event directly or indirectly during the pandemic, including midwives and healthcare professionals. Future recommendations for research may include medium and long-term psychosocial effects of becoming a parent during the pandemic and the exploration of ways to provide family centred care which is inclusive of supporting persons and birth companions.

Author contributions

SF, SO, SB, PV and AN contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the research site’s Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study.

Approval number: 3140/2020 EC Brianza

Date of approval: 18/06/2020

Funding and Conflict of interest

This project was self-funded and no conflicts of interest were involved

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. C. Callegari, Dr. F. Brunetti, Dr. L. La Milia, and Dr. M. Vasarri for their help in the recruitment of women and partners. We would also like to thank all the participants involved in the study.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Clinical Management of Covid-19. Interim Guidance. May 27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. Companion of Choice During Labour and Childbirth for Improved Quality of Care. Evidence-to-action Brief. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohren M.A., Hofmeyr G.J., Sakala C., Fukuzawa R.K., Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;7(July (7)) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohren M.A., Berger B.O., Munthe-Kaas H., Tunçalp Ö. Perceptions and experiences of labour companionship: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;3(March (3)) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012449.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comitato Percorso Nascita e Assistenza Pediatrica-Adolescenziale di Regione Lombardia, SLOG, SIMP, AOGOI, SIN, SYRIO, e SISOGN: Infezione da SARS-CoV-2: indicazioni ad interim per gravida-partoriente, puerpera-neonato e allattamento. 2020 March 7.

- 6.Poon L.C., Yang H., Kapur A., Melamed N., Dao B., Divakar H., et al. Global interim guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during pregnancy and puerperium from FIGO and allied partners: information for healthcare professionals. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;149(3):273–286. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravaldi C., Wilson A., Ricca V., Homer C., Vannacci A. Pregnant women voice their concerns and birth expectations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Women Birth. 2021;34(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweet L., Bradfield Z., Vasilevski V., Wynter K., Hauck Y., Kuliukas L., et al. Becoming a mother in the ‘new’social world in Australia during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Midwifery. 2021;98 doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2021.102996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradfield Z., Wynter K., Hauck Y., Vasilevski V., Kuliukas L., Wilson, et al. Experiences of receiving and providing maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: a five-cohort cross-sectional comparison. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson A.N., Ravaldi C., Scoullar M.J., Vogel J.P., Szabo R.A., Fisher J.R., et al. Caring for the carers: ensuring the provision of quality maternity care during a global pandemic. Women Birth. 2021;34(3):206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fumagalli S., Ornaghi S., Borrelli S., Vergani P., Nespoli A. The experiences of childbearing women who tested positive to COVID -19 during the pandemic in northern Italy. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.01.001. ISSN 1871-5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black B., Laking J., McKay G. Birth partners are not a luxury. BMJ Opin. 2020;(September) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasilevski V., Sweet L., Bradfield Z., Wilson A.N., Hauck Y., Kuliukas L., et al. Receiving maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of women’s partners and support persons. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith J.A. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2004;1(1):39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith J.A., Shinebourne P. American Psychological Association; 2012. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoga L.A.K., Gouveia L.M.R., Higashi A.B., de Souza Zamo-Roth F. The experience and role of a companion during normal labor and childbirth: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Evid. Synth. 2013;11(12):121–156. doi: 10.11124/01938924-201109641-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coutinho E.C., Antunes J.G.V.C., Duarte J.C., Parreira V.C., Chaves C.M.B., Nelas P.A.B. Benefits for the father from their involvement in the labour and birth sequence. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016;217:435–442. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmir R., Schmied V. A qualitative study of the impact of adverse birth experiences on fathers. Women Birth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson M., Fenwick J., Premberg Å. A meta-synthesis of fathers’ experiences of their partner’s labour and the birth of their baby. Midwifery. 2015;31(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groenewald T. A phenomenological research design illustrated. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2004;3(1):42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmir R., Schmied V., Jackson D., Wilkes L. Interviewing people about potentially sensitive topics. Nurse Res. 2011;19(1):12–16. doi: 10.7748/nr2011.10.19.1.12.c8766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradfield Z., Wynter K., Hauck Y., Vasilevski V., Kuliukas L., Wilson A.N., et al. Experiences of receiving and providing maternity care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: a five-cohort cross-sectional comparison. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanardo V., Manghina V., Giliberti L., Vettore M., Severino L., Straface G. Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;150(2):184–188. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2018. Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakermans‐Kranenburg M.J., Lotz A., Alyousefi-van Dijk K., van IJzendoorn M. Birth of a father: fathering in the first 1,000 days. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019;13(4):247–253. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gettler L.T., Kuo P.X., Sarma M.S., Trumble B.C., Burke Lefever J.E., Braungart‐Rieker J.M. Fathers’ oxytocin responses to first holding their newborns: interactions with testosterone reactivity to predict later parenting behavior and father‐infant bonds. Dev. Psychobiol. 2021;00:1–15. doi: 10.1002/dev.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . 2020. Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) when COVID-19 Disease is Suspected: Interim Guidance. 13 March (No. WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2020.4) [Google Scholar]