Abstract

Susceptibility to 41 antimicrobials was studied with 99 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strains, and different pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles were identified among 130 prospectively collected isolates. Moxalactam, doxycycline, minocycline, and clinafloxacin displayed the highest activity (≥98% susceptibility). Ticarcillin resistance (75%) was reverted by clavulanate in 25% of strains. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance was 26.2% (≥4 [trimethoprim]/76 [sulfamethoxazole] μg/ml) and dropped to 11.1% when an 8/152-μg/ml breakpoint was applied based on its bimodal MIC distribution. Resistance was lower when unique strains were considered, because clonal organisms contribute to resistance.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, an opportunistic pathogen, has risen to prominence during the last few years. Infections due to S. maltophilia usually appear in immunocompromised and intensive care unit (ICU) patients, particularly those catheterized or on mechanical ventilation. In addition, S. maltophilia is frequently recovered from the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. Prolonged hospitalization with broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy may select this organism from respiratory and gastrointestinal locations or may enhance its acquisition from environmental sources (7). S. maltophilia is commonly multiresistant to several antimicrobials, including β-lactams, due to heterogeneous production of β-lactamases (7). Reduced permeability and expression of efflux pumps could enhance this resistance phenotype (2, 23, 24). Moreover, the recent demonstration of genetic transfer between gram-positive organisms and S. maltophilia may explain the evolution toward an extended multiresistance phenotype (3).

We present here the activities of a wide range of antimicrobials against a large collection of S. maltophilia isolates prospectively and consecutively recovered from 1995 to 1998 at the Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain, which is a teaching hospital with 1,200 beds. A total of 130 S. maltophilia isolates recovered from 105 hospitalized patients in medical and surgical wards and in ICUs was studied. Isolates were obtained from respiratory (n = 79), blood (n = 19), wound (n = 15), and other clinical samples (n = 11) and from hospital environmental sources (n = 6). Identification was performed with both the API-20NE (BioMerieux, La Balme, France) and PASCO (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) systems. Isolates were characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) with a CHEF-DRII system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) as previously described (20) to recognize bacterial clones. Results were interpreted according to standard criteria (17).

MICs corresponding to 41 antimicrobials (Table 1) were determined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) agar dilution method (15). Susceptibility testing was performed with Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) and a final inoculum of 105 CFU/spot. MICs were read after a full 24-h incubation at 35°C. NCCLS-recommended American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) isolates (15) and S. maltophilia ATCC 13637 were used for quality control. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole susceptibility was also assayed with E-test strips on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 0.1 U of thymidine phosphorylase (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. MICs were analyzed with the Epi-Info 6.04a program (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of 41 antimicrobials against 99 S. maltophilia strains with different PFGE profiles

| Antimicrobial agent (inhibitor concn [μg/ml]) | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

% of resistant strainsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| Ampicillin | 64–>1,024 | 1,024 | >1,024 | NAc |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | ≤4–>1,024 | 1,024 | >1,024 | NA |

| Ticarcillin | 2–>1,024 | 512 | >1,024 | 73.7 |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanate (2) | 0.5–>1,024 | 64 | >1,024 | 46.5 |

| Piperacillin | 4–>1,024 | 256 | >1,024 | 63.6 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam (4) | 2–>1,024 | 128 | 1,024 | 54.5 |

| Cefotaxime | 0.5–>1,024 | 64 | 512 | 61.6 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.06–1,024 | 16 | 256 | 49.5 |

| Cefpirome | 1–512 | 128 | 256 | NA |

| Cefepime | 0.12–256 | 32 | 128 | 53.5 |

| Moxalactam | 0.03–256 | 2 | 32 | 2.0 |

| Aztreonam | 2–>1,024 | 256 | >1,024 | 91.9 |

| Aztreonam-clavulanate (2) | 0.25–>1,024 | 128 | 1,024 | 65.7d |

| Imipenem | 4–>1,024 | 512 | >1,024 | 99.0 |

| Meropenem | 1–1,024 | 64 | 256 | 87.9 |

| Gentamicin | 0.25–>256 | 64 | >256 | 80.8 |

| Tobramycin | 0.25–>256 | 64 | >256 | 76.7 |

| Kanamycin | 2–>256 | 256 | >256 | NA |

| Amikacin | 0.25–>256 | 256 | >256 | 80.8 |

| Netilmicin | 0.25–256 | 128 | 256 | 77.7 |

| Erythromycin | 16–>256 | 128 | 256 | NA |

| Clarithromycin | 16–>256 | 128 | 256 | NA |

| Azithromycin | 2–>128 | 64 | 128 | NA |

| Tetracycline | 0.5–128 | 32 | 64 | 85.8 |

| Doxycycline | 0.06–16 | 1 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Minocycline | ≤0.01–2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 |

| Nalidixic acid | 0.06–256 | 4 | 32 | NA |

| Norfloxacin | 0.06–256 | 16 | 64 | 55.6 |

| Pefloxacin | ≤0.01–64 | 1 | 4 | NA |

| Ofloxacin | ≤0.01–64 | 0.5 | 4 | 5.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.01–64 | 0.5 | 4 | 13.1 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.01–32 | 0.2 | 2 | 3.0 |

| Sparfloxacin | ≤0.01–8 | 0.1 | 0.5 | NA |

| Grepafloxacin | ≤0.01–16 | 0.1 | 1 | NA |

| Gatifloxacin | ≤0.01–16 | 0.1 | 1 | 3.0 |

| Moxifloxacin | ≤0.01–32 | 0.1 | 0.5 | NA |

| Clinafloxacin | ≤0.01–4 | 0.1 | 0.5 | NA |

| Trovafloxacin | ≤0.01–32 | ≤0.01 | 0.5 | NA |

| Chloramphenicol | 2–128 | 16 | 64 | 35.4 |

| Fosfomycin | 32–>256 | 128 | 256 | NA |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 0.1/1.9–>608/32 | 38/2 | 608/32 | 27.3 |

50% and 90%, MIC50 and MIC90, respectively.

Susceptibility rates were calculated according to the NCCLS proposed breakpoints for P. aeruginosa and nonmembers of the family Enterobacteriaceae.

NA, no available NCCLS criteria.

The NCCLS breakpoint for aztreonam was used for aztreonam-clavulanate.

In our study, although isolates had the same hospital origin, a high clonal diversity was observed, because 99 well-defined strains were identified among 130 S. maltophilia isolates. Despite this fact and the evidence that most infections due to S. maltophilia are independently acquired (5, 9), several cases of nosocomial outbreaks have been reported (1, 8). In these situations, repetitive isolates, particularly those from unrecognized outbreaks, could affect cumulative susceptibility testing reports. To avoid this problem, redundant isolates are commonly eliminated with demographic criteria, but rarely with epidemiological molecular criteria. In our study, isolates displaying an identical PFGE profile from the same patient or as a result of patient-to-patient transmission were excluded, and only 99 unique strains were initially considered for susceptibility analysis.

On the other hand, independent studies have demonstrated methodological problems associated with susceptibility testing of S. maltophilia (4, 6, 7, 18). In our study, in the absence of specific NCCLS recommendations for S. maltophilia, the agar dilution technique was used, but MICs were read after a full 24-h incubation at 35°C (13). This was a compromise between the 16- to 20-h incubation conditions proposed by the NCCLS for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonmembers of the family Enterobacteriaceae and the 48 h recommended by Carroll et al. (6) for S. maltophilia when testing nonbacteriostatic agents. With this methodology, and despite the remarkable genomic diversity, the S. maltophilia susceptibility profile of 99 strains demonstrated high phenotypic consistency. In general, and in agreement with previous studies (7), S. maltophilia was inherently resistant to a variety of antimicrobials, including β-lactams, aminoglycosides, and macrolides. As expected, nearly all strains were resistant to imipenem (99%). Although meropenem was eight times more active than imipenem and showed less resistance (87.9%), none of the S. maltophilia strains should be considered truly susceptible to this compound due to the easy and rapid selection of stable resistant mutants when exposed to carbapenems (11).

Across the β-lactams, moxalactam displayed the highest activity, with only 2% resistance. Less than 25% of S. maltophilia strains were susceptible to ticarcillin, piperacillin, and aztreonam (Table 1). Interestingly, clavulanate reverted ticarcillin and aztreonam resistance in 27.3 and 26.2% of strains, respectively. The presence of L2 β-lactamases could be responsible for this effect, because these 2be group β-lactamases are inhibited well by clavulanate and, to a lesser extent, by tazobactam (21). Piperacillin-tazobactam resistance (54.5%) was higher than ticarcillin-clavulanate resistance (46.5%), but lower than aztreonam-clavulanate resistance (65.6%). When the aztreonam NCCLS breakpoint (15) was used, resistance to the last combination was higher than that observed by other authors (4), probably due to the lower clavulanate concentration used. Although this combination has been shown to be bacteriostatic (14), the clinical value of this finding has been questioned, because both compounds exhibit different pharmacokinetics.

All aminoglycosides showed reduced activity against S. maltophilia strains, which could be due to the constitutive production of a chromosomal aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme (12) and to the expression of efflux systems (24). These pumps could also affect other antimicrobials and barely contributed to tetracycline, quinolone, and chloramphenicol resistance (2). Therefore, minocycline (mode MIC, 0.1 μg/ml) and doxycycline (1 μg/ml) showed higher intrinsic activity than tetracycline (32 μg/ml). The rate of tetracycline resistance was 86%; the rates of doxycycline and minocycline resistance were less than 1%. This result could be of particular clinical interest.

In agreement with other studies (16, 19, 22), new fluoroquinolones have a potential role in the treatment of S. maltophilia infections. Trovafloxacin, clinafloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, grepafloxacin, and levofloxacin displayed similar intrinsic activities, with MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited (MIC90s) four- to eightfold lower than those of ciprofloxacin. Moreover, they inhibited nearly all of the S. maltophilia strains tested at concentrations achievable in serum or the pulmonary tract. At 2 μg/ml, more than 95% of strains were inhibited by new fluoroquinolones, whereas the corresponding values for ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin were 86.8 and 87.8%, respectively. Contrary to quinolones, macrolides displayed high MICs for S. maltophilia. These values do not predict clinical benefits, but they could eventually play an adjunctive role, as in cystic fibrosis and panbrochiolitis patients colonized with P. aeruginosa (10).

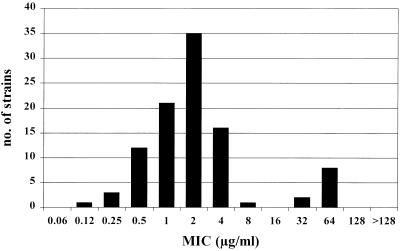

Although the combination trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is bacteriostatic, it is considered to be the drug of choice in S. maltophilia infections. Susceptibility testing of this combination is particularly problematic in S. maltophilia, and different results have been observed when different methods and conditions were used (4, 7, 18). In our study, susceptibility was assayed with both agar dilution and E-test strips on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 0.1 U of thymidine phosphorylase per ml in order to interfere with thymidine that may be present in the medium. As previously reported (4), a high level of agreement among these techniques was obtained (data not shown). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance was detected in 26.2% of strains, which is higher than the rates (0% to 10%) previously reported (4, 5, 18). Different methodologies and breakpoints could be responsible for these differences. The number of strains inhibited at each concentration strongly suggests a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1). Resistant populations can be clearly differentiated with a concentration of 8 [trimethoprim]/152 [sulfamethoxazole] μg/ml, which may represent a better microbiological resistance breakpoint than that offered by the NCCLS (4/76 μg/ml) (15). With a breakpoint of 8/152 μg/ml, resistance rates dropped to 11.1%.

FIG. 1.

Number of unique S. maltophilia strains (n = 99) inhibited at each trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (ratio of 1:19) concentration tested. Concentrations are expressed in terms of trimethoprim.

As previously stated, S. maltophilia isolates belonging to clonal groups could affect susceptibility analysis. In fact, highly diverse environmental isolates are less resistant than clonal nosocomial isolates (5). In our study, rates of resistance to β-lactams and aminoglycosides were slightly higher when repetitive isolates were included in susceptibility analysis. Moreover, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline resistance rates were significantly lower (P < 0.01, chi-square test) in S. maltophilia strains with different PFGE profiles (n = 99) than in isolates belonging to clonal groups (n = 31). Ciprofloxacin resistance rates in both groups were 13.1 and 29.0%, respectively, and tetracycline resistance rates were 85.5 and 96.8%, respectively. It is worth noting that ciprofloxacin resistance in clonal isolates was linked with higher quinolone, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol MICs. To the contrary, minocycline and doxycycline MICs were less affected in these isolates. This phenotype of cross-resistance to chloramphenicol and tetracycline has been previously associated with efflux pumps in S. maltophilia (2).

In conclusion, the susceptibility profile of S. maltophilia strains showed a high phenotypic homogeneity despite their high genomic diversity. Nevertheless, resistance rates were higher when isolates belonging to clonal groups were considered. Selection and spread of these isolates will enhance the antimicrobial resistance rates of this organism.

Acknowledgments

S. Valdezate was supported by a research grant (2114/1998) from the Consejería de Educación, Comunidad de Madrid, Spain. This study was partially supported by the Microbial Sciences Foundation, Madrid, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alfieri N, Ramotar K, Armstrong P, Spornitz M E, Ross G, Winnick J, Cook D R. Two consecutive outbreaks of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Xanthomonas maltophilia) in an intensive-care unit defined by restriction fragment-length polymorphism typing. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:553–556. doi: 10.1086/501668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso A, Martínez J L. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1140–1142. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Sanchez P, Martínez J L. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia D457R contains a cluster of genes from gram-positive bacteria involved in antibiotic and heavy metal resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1778–1782. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1778-1782.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arpi M, Victor M A, Mortensen I, Gottschau A, Bruun B. In vitro susceptibility of 124 Xanthomonas maltophilia (Stenotrophomonas maltophilia) isolates. APMIS. 1996;104:108–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg G, Roskot N, Smalla K. Genotypic and phenotypic relationships between clinical and environmental isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3594-3600.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll K C, Chen S, Nelson R, Campbell D M, Claridge J D, Garrison M W, Kramp J, Malone C, Hoffmann M, Anderson D E. Comparison of various in vitro susceptibility methods for testing Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;32:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(98)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denton M, Kerr K G. Microbiology and clinical aspects of infection associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:57–80. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García de Viedma D, Marín M, Cercenado E, Alonso R, Rodríguez-Creixems M, Bouza E. Evidence of nosocomial Stenotrophomonas maltophilia cross-infection in a neonatology unit analyzed by three molecular typing methods. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:816–820. doi: 10.1086/501590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauben L, Vauterin L, Moore E R, Hoste B, Swings J. Genomic diversity of the genus Stenotrophomonas. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:1749–1760. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howe R A, Spencer R C. Macrolides for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:153–155. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howe R A, Wilson M P, Walsh T R, Millar M R. Susceptibility testing of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia to carbapenems. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:13–17. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert T, Ploy M C, Denis F, Courvalin P. Characterization of the chromosomal aac(6′)-Iz gene of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2366–2371. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecso-Bonet M, Bergone-Bérézin E. Susceptibility of 100 strains of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia to three β-lactams and five β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:717–720. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz Bellido J L, Muñoz Criado S, García García I, Alonso Manzanares M A, Gutiérrez Zufiaurre M N, García Rodríguez J A. In vitro activities of β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: correlation between methods for testing inhibitory activity, time-kill curves, and bactericidal activity. Antmicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2612–2615. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. 2001. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eleventh informational supplement, vol. 20, no. 1. Document M100–S11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pankuch G A, Jacobs M R, Applebaum P C. Susceptibilities of 123 strains of Xanthomonas maltophilia to clinafloxacin, PD 131628, PD 138312, PD 140248, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:369–370. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traub W H, Leonhard B, Bauer D. Antibiotic susceptibility of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (Xanthomonas maltophilia): comparative (NCCLS criteria) evaluation of antimicrobial drugs with agar dilution and the agar disk diffusion (Bauer-Kirby) test. Chemotherapy. 1998;44:164–173. doi: 10.1159/000007111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdezate S, Vindel A, Baquero F, Cantón R. Comparative in vitro activity of quinolones against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;18:908–911. doi: 10.1007/s100960050430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valdezate S, Vindel A, Maiz L, Baquero F, Escobar H, Cantón R. Persistence and variability of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in cystic fibrosis patients, Madrid, 1991–1998. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:113–122. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh T R, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Sequence analysis and enzyme kinetics of the L2 serine β-lactamase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1460–1464. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss K, Restieri C, De Carolis E, Laverdière M, Guay H. Comparative activity of new quinolones against 326 clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:363–365. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki E, Ishii J, Sato K, Nakae T. The barrier function of the outer membrane of Pseudomonas maltophilia in the diffusion of saccharides and beta-lactam antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;51:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Li X Z, Poole K. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: involvement of a multidrug efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:287–293. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.287-293.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]