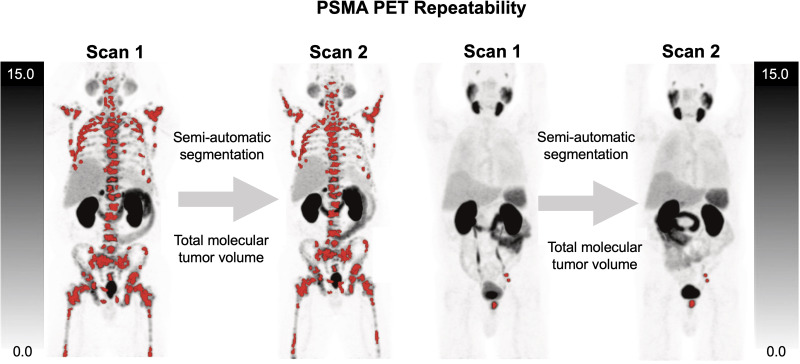

Visual Abstract

Keywords: PSMA PET, tumor volume, repeatability

Abstract

Molecular tumor volume (MTV) is a parameter of interest in prostate cancer for assessing total disease burden on prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) PET. Although software segmentation tools can delineate whole-body MTV, a necessary step toward meaningful monitoring of total tumor burden and treatment response through PET is establishing the repeatability of these metrics. The present study assessed the repeatability of total MTV and related metrics for 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC in prostate cancer. Methods: Eighteen patients from a prior repeatability study who underwent 2 test–retest PSMA PET/CT scans within a mean interval of 5 d were reanalyzed. Within-subject coefficient of variation and repeatability coefficients (RCs) were analyzed on a per-lesion and per-patient basis. For the per-lesion analysis, individual lesions were segmented for analysis by a single reader. For the per-patient analysis, subgroups of up to 10 lesions (single reader) and the total tumor volume per patient were segmented (independently by 2 readers). Image parameters were MTV, SUVmax, SUVpeak, SUVmean, total lesion PSMA, and the related metric PSMA quotient (which integrates lesion volume and PSMA avidity). Results: In total, 192 segmentations were analyzed for the per-lesion analysis and 1,662 segmentations for the per-patient analysis (combining the 2 readers and 2 scans). The RC of the MTV of single lesions was 77% (95% CI, 63%–96%). The RC improved to 33% after aggregation of up to 10 manually selected lesions into subgroups assessed per patient (95% CI, 25%–46%). The RC of the semiautomatic MTVtotal (the sum of all voxels in the whole-body total tumor segmentation per patient) was 35% (95% CI, 25%–50%), the Bland-Altman bias was −6.70 (95% CI, −14.32–0.93). Alternating readers between scans led to a comparable RC of 37% (95% CI, 28%–49%) for MTVtotal, meaning that the metric is robust between scanning sessions and between readers. Conclusion: 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET–derived semiautomatic MTVtotal is repeatable and reader-independent, with a change of ±35% representing a true change in tumor volume. Volumetry of single manually selected lesions has considerably lower repeatability, and volumetry based on subgroups of these lesions, although showing acceptable repeatability, is less systematic. The semiautomatic analysis of MTVtotal used in this study offers an efficient and robust means of assessing response to therapy.

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of death in men (1). Especially in advanced prostate cancer, therapy monitoring is challenging. The blood tumor marker prostate-specific antigen is routinely used to monitor disease progression (2). However, prostate-specific antigen levels may be influenced by tumor dedifferentiation and androgen deprivation therapy, which raises the need for image-based methods for global tumor assessment (3,4). For now, bone scanning and CT are the established methods for assessing treatment response in advanced disease (2). More recently, prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) imaging with PET has been shown to be superior to conventional imaging for both initial and recurrent cancer staging (5,6). Therefore, PSMA PET seems to be a promising methodology to quantify the prostate cancer tumor volume over time.

The recently proposed PSMA PET progression criteria, as well as a recently published consensus meeting, recommended consideration of PSMA PET–derived volumetric measurements to detect progressive disease (7,8). Indeed, several studies have shown that the quantification of the total tumor volume using PSMA PET is feasible and that it is a statistically significant negative predictor for overall survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer (9–12). Total tumor uptake values analogous to total lesion glycolysis for 18F-FDG can also be assessed with PSMA PET.

To date, the repeatability of PSMA PET–derived volumetric and total tumor uptake measurements has not been sufficiently investigated. Previously, Pollard et al. reported 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET repeatability for SUVmax in bone and nodal metastases from prostate cancer (13). A variety of factors beyond true change in tumor can lead to variability in quantitative PET imaging, including the segmentation methods used. To reliably assess quantitative change between PSMA PET scans, it is necessary to understand the normal variability within the patient, radiotracer, and imaging system. The present study evaluates the repeatability of volumetric and uptake measurements for individual tumors and total tumor volume on test–retest 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET/CT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Image Acquisition

Eighteen patients were included in the analysis. The institutional review board approved the study protocol (NCT02952469), and all subjects gave written informed consent. Dataset details were previously reported by Pollard et al. in their study of test–retest repeatability (13). Here, the identical dataset was used. Briefly, all patients underwent 2 PSMA PET/CT acquisitions within a mean interval of 5 d (range, 2–14 d). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. 68Ga-gallium-PSMA-HBED-CC (also known as PSMA-11 and referred to simply as PSMA in the remainder of this paper) was synthesized as previously published (13). Either a Biograph mCT (with FlowMotion) or a Biograph TruePoint PET/CT system was used for image acquisition (Siemens Healthineers). The follow-up scan was performed on the same scanner as the initial scan. PET data were acquired using a previously published protocol (PET scan starting 60 min after tracer injection with scan coverage from vertex to mid thigh, 3- to 4-min scan time per bed position) (13). A 3-dimensional ordered-subset expectation maximization algorithm was used for image reconstruction (with time-of-flight information in case of the mCT).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics and MTVtotal Reported for Each Scan and Reader

| MTVtotal (mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient no. | PSA within ≤90 d (ng/mL) | Gleason score at diagnosis | R1, scan 1 | R2, scan 1 | R1, scan 2 | R2, scan 2 |

| 1 | 0.15 | 7 (4 + 5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 4.35 | 6 (3 + 3) | 4.81 | 5.88 | 4.81 | 5.88 |

| 3 | 104.5 | 9 (4 + 5) | 395.7 | 404.02 | 399.18 | 402.22 |

| 4 | 0.14 | 9 (4 + 5) | 59.91 | 62.59 | 82.42 | 66.9 |

| 5 | 0.66 | 9 (5 + 4) | 6.42 | 6.77 | 5.18 | 7.56 |

| 6 | 0.22 | 9 (5 + 4) | 3.78 | 4.67 | 3.78 | 4.67 |

| 7 | 56.3 | Presumptive diagnosis | 38.89 | 35.59 | 41.36 | 22.49 |

| 8 | 95.5 | 7 (4 + 3) | 206.38 | 247.85 | 236.35 | 221.08 |

| 9 | 276.3 | 9 (4 + 5) | 643.19 | 741.4 | 643.19 | 642.43 |

| 10 | 0.04 | Presumptive diagnosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 0.64 | 9 (4 + 5) | 7.78 | 8.33 | 7.78 | 8.33 |

| 12 | 2.8 | Lymph node biopsy | 31.49 | 44.68 | 30.53 | 46.24 |

| 13 | 40.1 | 10 (5 + 5) | 464.53 | 587.13 | 552.7 | 515.05 |

| 14 | 19.7 | 7 (3 + 4) | 18.87 | 22.83 | 18.87 | 22.83 |

| 15 | 2.5 | Bone biopsy | 2.26 | 1.96 | 2.26 | 1.96 |

| 16 | 54.1 | 9 (5 + 4) | 85.89 | 102.6 | 92.3 | 86.56 |

| 17 | 2.5 | 9 (5 + 4) | 21.78 | 21.81 | 22.29 | 21.81 |

| 18 | 2.5 | 9 (5 + 4) | 6.52 | 6.31 | 5.53 | 7.34 |

PSA = prostate-specific antigen; R1 = reader 1; R2 = reader 2.

Tumor Analysis per Lesion

For the repeatability analysis of individual lesions, up to 10 metastases (skeletal or nodal) or primary tumor lesions were segmented in both the first and second scans by a single reader using a manual segmentation with a 50% isocontour. A single-reader model was chosen for the single-lesion and the subgroup analysis portions of the study. Because the same small number of lesions needed to be selected on each PET scan, the single-reader approach minimized variability introduced by interrater differences in lesion selection and segmentation. Lesions were identified as nonphysiologic sites of uptake with an SUV exceeding the regional background activity. Lesions were selected at random from the regions segmented by the whole-body molecular tumor volume (MTV) analysis, described in detail in the section on total tumor analysis. For each lesion, SUVmax, SUVpeak, SUVmean, lesion MTV (MTVlesion), total lesion PSMA (PSMA-TLlesion), and total lesion quotient (PSMA-TLQlesion) were measured. MTVlesion was determined by the sum of the voxels (Eq. 1) within a threshold 50% isocontour of the local SUVmax. PSMA-TLlesion and PSMA-TLQlesion were calculated as in Equations 2 and 3.

| Eq. 1 |

| Eq. 2 |

| Eq. 3 |

Tumor Subgroup Analysis per Patient

One reader manually selected at random a group of up to 10 lesions per patient from the regions segmented by the whole-body MTV analysis technique (described in the next section). In patients with a large number of metastatic lesions, lesions were selected randomly to reflect a broad distribution of anatomic regions. The lesions in this subgroup were individually manually segmented and were assessed as an aggregate. The mean of SUVmax and SUVmean (subgroup mean SUVmax and subgroup mean SUVmean, respectively) were calculated. The sum and mean of MTVlesion, the sum of PSMA-TLlesion, and the sum of PSMA-TLQlesion (MTVsubgroup, subgroup MTVmean, PSMA-TLsubgroup, and PSMA-TLQsubgroup, respectively) were calculated as in Equations 4–7, where n is the number of lesions within the subgroup and i is the ordinal number of the lesion. PSMA-TLlesion is analogous to total lesion glycolysis for 18F-FDG and, when calculated for aggregate tumors, the individual PSMA-TLlesion values are summed.

| Eq. 4 |

| Eq. 5 |

| Eq. 6 |

| Eq. 7 |

Total Tumor Analysis per Patient

For the total tumor analysis, all lesions were segmented using a semiautomatic approach as previously published (9). The investigational MICIIS research software prototype was used for the single lesion and total tumor analyses (previously named MI Whole-Body Analysis Suite; Siemens Healthineers). Briefly, all voxels with an SUVpeak exceeding the following liver-specific threshold were selected as candidate foci:

| Eq. 8 |

where the liver-specific threshold was calculated as previously described and SUVSD is the SD of the SUV distribution in the liver volume of interest (9,10). The threshold described in Equation 8 adjusts for the tumor sink effect, which has a tendency to lower liver uptake; the first part of the formula is a corrective coefficient for the SUV reduction due to the sink effect, and the second part is the calculation for the uncorrected liver threshold. Individual-lesion segmention was based on a threshold 50% isocontour of the local SUVmax. In analogy to the European Association of Nuclear Medicine recommendations for 18F-FDG PET imaging, a threshold 50% isocontour-based approach was chosen for this study (14). Segmentation errors such as inclusion of sites of normal physiologic uptake or exclusion of tumor lesions were adjusted manually. There were no adjustments of segmented tumor contours in addition to inclusion or exclusion of lesions. Example whole-body tumor segmentations and segmentation errors are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Two readers with PET experience independently delineated all tumor lesions, and their delineated PET data were analyzed separately.

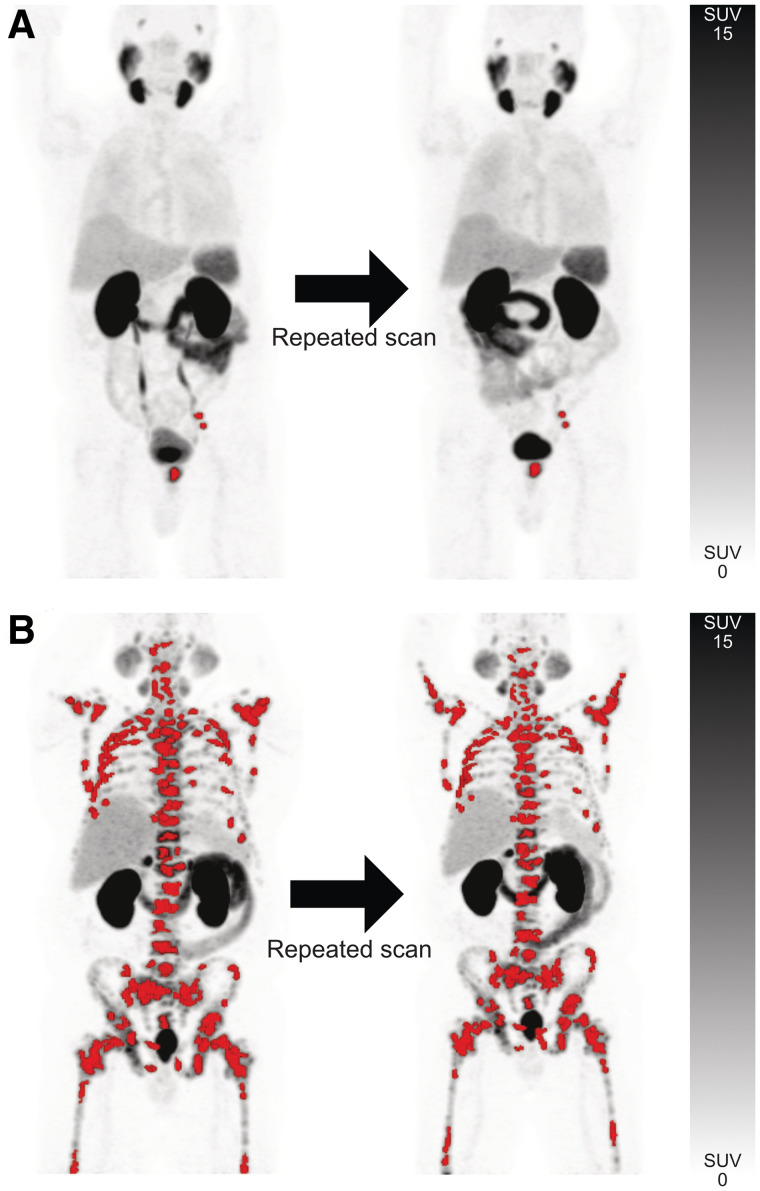

FIGURE 1.

Semiautomatic total tumor segmentations with red overlay designating sites of segmented lesions in scans 1 and 2 for patient with disease limited to prostate and left pelvic lymph nodes (A) and patient with extensive skeletal metastases (B). Interval between scans was 2 d for both patients.

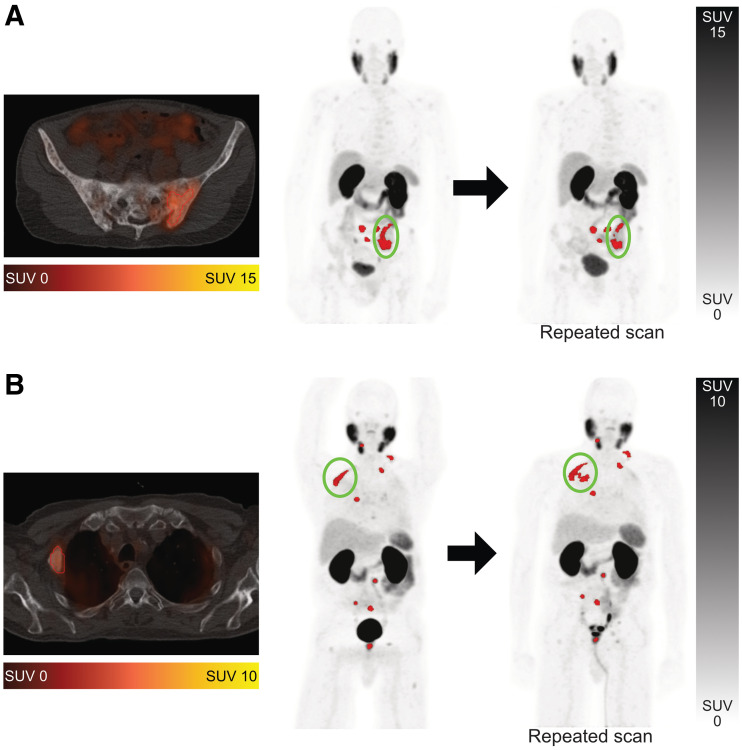

FIGURE 2.

Examples of segmentation challenges on 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET/CT. Segmented tumor metastases are shown in red. (A) Metastasis in os ilium was segmented as single lesion on first scan but as 3 separate lesions in second scan (encircled). (B) Metastasis in rib was segmented accurately on first scan but inaccurately on second scan, with isocontour including portion of lung (encircled). Error was resolved manually.

The sum of all voxels in the whole-body total tumor segmentation per patient was designated MTVtotal. The mean of the volume of the individual segmented volumes comprising the MTVtotal was calculated as in Equation 5 and was designated total MTVmean. Likewise, the mean of SUVmax and SUVmean of these component volumes was designated total mean SUVmax and total mean SUVmean, respectively. The PSMA-TLlesion and PSMA-TLQlesion values for the component volumes were summed as in Equations 6 and 7 and were designated PSMA-TLtotal and PSMA-TLQtotal, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods for the sample size of the original dataset used in this analysis were reported by Pollard et al. (13). The Pearson correlation coefficient was used for descriptive statistics. Bland–Altman plots were created for absolute (rather than relative percent) differences in MTVtotal and mean SUVmax (15). Correlation in MTVtotal between readers for the same scan and between scans for the same reader was evaluated with intraclass correlation coefficients. The repeatability assessment using a relative comparison approach was done as described by Obuchowski (16). The within-subject coefficient of variation (wCV) is given by

| Eq. 9 |

where n is the number of subjects and scans A and B are the quantitative PET measurements from the first and second PET scans, respectively. The repeatability coefficient (RC) is given by

| Eq. 10 |

The CIs for wCV and RC were determined by bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates. RC variability in relation to lesion SUVmax was evaluated by an exploratory approach for subsets of lesions in multiple steps. For each step, all lesions that had an SUVmax below an arbitrarily defined SUVmax threshold were included. A distinct threshold was used for each step; the lowest SUVmax threshold was 1, and the increment was 5. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.5.2 (The R Foundation, https://www.r-project.org/) and Microsoft Excel 2016, version 16.0.5110.1000. Statistical analysis was done by David Kersting and Robert Seifert.

RESULTS

Test–Retest Scan Parameters

As previously published for the same cohort, the median interval between scans 1 and 2 was 5 d (range, 2–14 d). No statistically significant difference between scans 1 and 2 was observed regarding injected dose (mean, 133.1 vs. 133.1 MBq; P = 1.0) or image delay (mean, 60. 6 vs. 60.7 min; P = 0.9). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Repeatability of Manually Segmented Individual Lesions

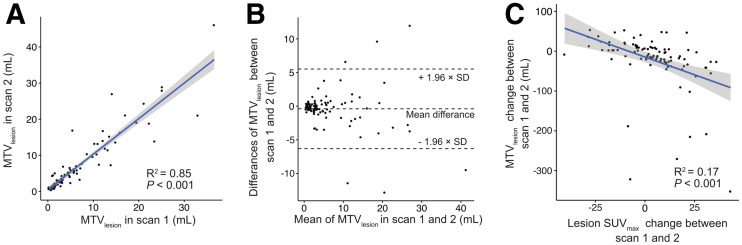

For the per-lesion analysis, 96 metastases from 18 patients were manually delineated by a single reader, resulting in a total number of 192 segmentations from the 2 scans. Segmented lesions were regarded as independent observations. The RCs of MTVlesion and related metrics are shown in Table 2. Linear regression and Bland–Altman scatterplots for MTVlesion on scans 1 and 2 showed a relatively strong correlation (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.85) and no significant bias based on visual analysis (Figs. 3A and 3B). However, MTVlesion demonstrated poor repeatability, with an RC of 76.9% (95% CI, 62.9%–95.9%), and similarly poor repeatability when accounting for differences in lesion volume, with an RC of 64.7% (range, 49.3%–91.6%), for lesions 5 cm3 or larger and 83.9% (range, 65.5%–110.7%) for lesions smaller than 5 cm3. The Bland–Altman bias of MTVlesion was −0.39 (95% CI, −1.00 to 0.22) for all lesions. The deviation in MTVlesion between scans 1 and 2 correlated to a statistically significantly extent with the deviation in SUVmax between scans 1 and 2 (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.17) (Fig. 3C).

TABLE 2.

Repeatability of Manually Segmented Individual Lesions (MTVlesion)

| Metric | wCV (%) | RC (%) | 95% CI of RC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTVlesion | 27.7 | 76.9 | 62.9–95.9 |

| PSMA-TLlesion | 23.3 | 64.7 | 53.4–80.67 |

| PSMA-TLQlesion | 34.5 | 95.7 | 81.5–114.5 |

| Lesion SUVmax | 12.4 | 34.4 | 29.6–41.2 |

| Lesion SUVpeak | 9.9 | 27.3 | 23.3–32.8 |

| Lesion SUVmean | 11.8 | 32.7 | 27.5–40.2 |

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of individual manually segmented 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC–avid lesions. Linear regression and Bland–Altman plots (A and B) of MTVlesion show correlation between scans. (C) Association is noted between MTVlesion and SUVmax changes between scans 1 and 2.

Repeatability of Manually Segmented Subgroup of Lesions per Patient

Given the poor repeatability of MTVlesion, a larger subgroup of manually selected and segmented lesions was evaluated for repeatability per patient. Inclusion of multiple lesions for assessment as a subgroup allows for mitigation of individual lesion variability by averaging positive and negative variation across a larger number of lesions. The repeatability of MTVsubgroup and related metrics is presented in Table 3. MTVsubgroup demonstrated improved repeatability, with an RC of 33.1% (95% CI, 24.2%–46.2%), compared with MTVlesion and showed a repeatability comparable to that of the semiautomatic whole-body approach of MTVtotal. The Bland–Altman bias of MTVsubgroup was −2.32 (95% CI, −5.81 to 1.17). Supplemental Table 1 shows the association of RC, with SUVmax RC decreasing with increasing minimum SUVmax of segmented lesions (supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). This finding indicates that the repeatability was better when lesions with a low SUVmax were discarded from the manually segmented subgroup of lesions.

TABLE 3.

Repeatability of Manually Selected Lesion Subgroup per Patient (MTVsubgroup)

| Metric | wCV (%) | RC (%) | 95% CI of RC |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTVsubgroup | 12.0 | 33.1 | 24.2–46.2 |

| Subgroup MTVmean | 12.0 | 33.1 | 24.8–47.7 |

| PSMA-TLsubgroup | 7.4 | 20.6 | 16.0–26.9 |

| PSMA-TLQsubgroup | 18.4 | 51.0 | 36.5–78.0 |

| Subgroup mean SUVmax | 12.3 | 34.0 | 20.0–59.4 |

| Subgroup mean SUVpeak | 6.6 | 18.3 | 13.3–24.5 |

| Subgroup mean SUVmean | 9.1 | 25.2 | 17.5–35.7 |

Repeatability of Semiautomatic Segmentation of Total Tumor Volume per Patient

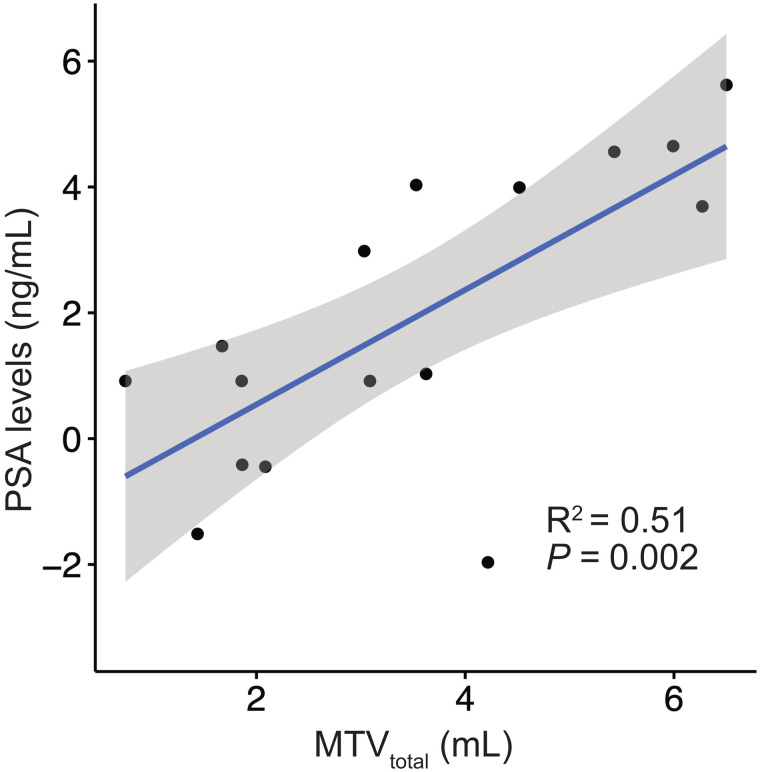

In total, 1,662 segmentations were performed for the per-patient analysis, including segmentations for the 2 readers and 2 scans. The MTVtotal for each reader for scans 1 and 2 is presented in Table 1. The RCs of the whole-body MTVtotal and related metrics are shown separately for both readers in Table 4. The RC of MTVtotal was 35.0% (95% CI, 24.9%–49.7%) in mean; the RCs for each reader were 37% and 33%. Linear regression and Bland–Altman scatterplots for MTVtotal and mean SUVmax for scans 1 and 2 showed a strong correlation (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.99) and no significant bias based on visual analysis (Fig. 4). The corresponding Bland–Altman bias of MTVtotal was −6.70 (95% CI, −14.32 to 0.93). The RC of MTVtotal and related metrics remained robust even when readers were hypothetically exchanged between scan timepoints with an RC of MTVtotal of 37.3% (95% CI, 27.9%–49.3%) (Table 5). A high correlation of MTVtotal between scans for the same reader (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.998; P < 0.001) and between readers for the same scan (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.993; P < 0.001) was noted (Fig. 5). MTVtotal showed a moderate correlation with prostate-specific antigen values (P < 0.002, R2 = 0.53) (Fig. 6). Other metrics using the semiautomatic technique, such as total mean SUVmax, total mean SUVmean, and PSMA-TLtotal, also showed improved repeatability as compared with individual lesion segmentation, with RC ranging from 23.6% to 28.4%.

TABLE 4.

Repeatability of Semiautomatic MTVtotal per Patient

| Metric | R1 wCV (%) | R2 wCV (%) | Mean wCV (%) | R1 RC (%) | R2 RC (%) | Mean RC (%) | 95% CI of mean RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTVtotal | 13.4 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 37.0 | 33.0 | 35.0 | 24.9–49.7 |

| Total MTVmean | 13.4 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 37.1 | 33.0 | 35.0 | 25.0–48.8 |

| PSMA-TLtotal | 8.4 | 12.1 | 10.3 | 23.3 | 33.5 | 28.4 | 20.7–41.9 |

| PSMA-TLQtotal | 19.4 | 17.3 | 18.4 | 53.9 | 48.0 | 50.9 | 32.7–84.7 |

| Total mean SUVmax | 8.4 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 23.3 | 23.9 | 23.6 | 17.0–32.4 |

| Total mean SUVmean | 8.1 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 22.6 | 22.2 | 22.4 | 16.4–30.7 |

R1 = reader 1; R2 = reader 2.

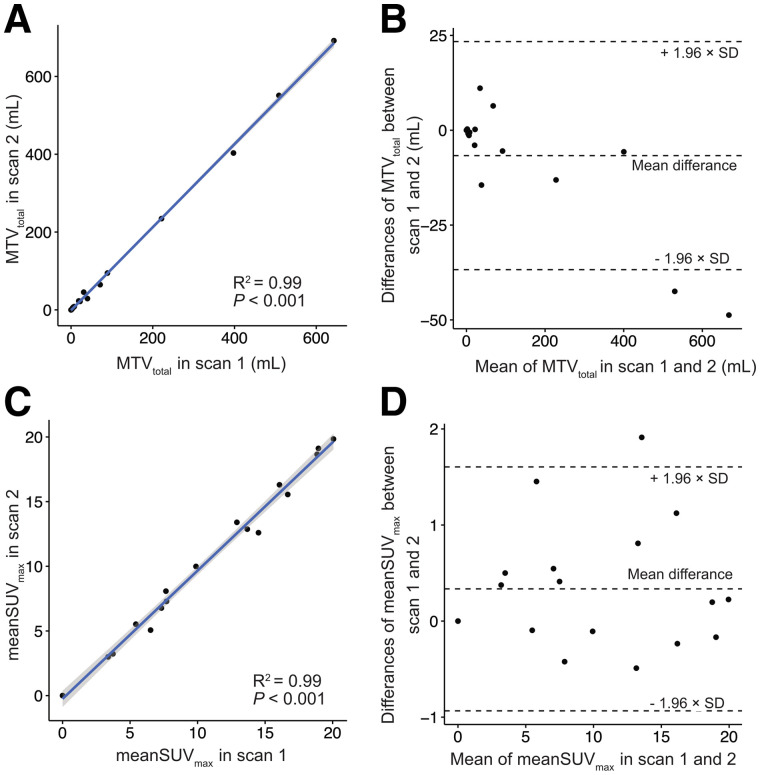

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of semiautomatic whole-body segmentation of 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC–avid lesions. Linear regression (A and C) and Bland–Altman plots (B and D) of MTVtotal and mean SUVmax show excellent correlation between scans and suggest no association between total tumor volume or lesion intensity and test–retest differences. Results for readers 1 and 2 were averaged for purposes of these graphs. (A and C) MTVtotal and mean SUVmax for scan 1 are plotted separately against same metric for scan 2. (B and D) Mean of MTVtotal or mean SUVmax between scans 1 and 2 was plotted against absolute difference in metric between 2 scans.

TABLE 5.

Repeatability of MTVtotal with Different Readers Between Scans

| Metric | R1, R2 RC (%) | R2, R1 RC (%) | Mean RC (%) | 95% CI of mean RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTVtotal | 29.9 | 44.7 | 37.3 | 27.9–49.3 |

| Total MTVmean | 29.9 | 44.7 | 37.3 | 29.9–44.7 |

| PSMA-TLtotal | 24.9 | 37.2 | 31.0 | 24.5–39.5 |

| PSMA-TLQtotal | 52.5 | 58.4 | 55.5 | 38.1–83.6 |

| Total mean SUVmax | 28.3 | 20.7 | 24.5 | 17.5–33.5 |

| Total mean SUVmean | 27.4 | 18.7 | 23.1 | 17.2–31.1 |

R1, R2 = first scan read by reader 1, second scan read by reader 2; R2, R1 = first scan read by reader 2, second scan read by reader 1.

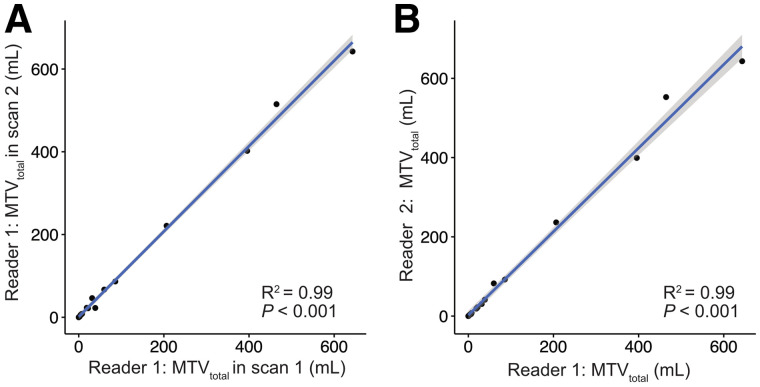

FIGURE 5.

Graphical analysis of intra- and interreader agreement in reporting MTVtotal, showing high correlation in measures between scans 1 and 2 for same reader (reader 1) (A) and showing high correlation in measures between 2 independent readers for same scan (scan 1) (B).

FIGURE 6.

Graphical analysis of prostate-specific antigen vs. MTVtotal, with log–log plot showing moderate correlation.

DISCUSSION

PSMA PET is now widely used to monitor patients with prostate cancer (5,6,17,18). Especially for recurrent prostate cancer, PSMA PET has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for localizing prostate cancer cells in the body (5,6). Growing evidence suggests that PSMA PET is also a useful clinical tool in patients with more advanced prostate cancer (19–21).

Measures of total tumor volume and total uptake on PSMA PET have been described, but its use in prostate cancer monitoring remains under debate (9,10). Analogous to the TNM system, a molecular imaging TNM (miTNM) system has been proposed, which scores extent of disease with regard to local tumor, regional lymph node metastases, bone metastases, and other distant metastases. (22). Given the distinct biologic aggressiveness and survival implications of various metastatic sites, the TNM-based system will likely remain an important prognostic tool in prostate cancer (23). However, because progressive disease is not always accompanied only by the occurrence of new metastases but also can include enlargement of existing metastases, the best assessment tools would therefore encompass assessment of both anatomic and total tumor volume, enabling consideration of both global disease status and aggressiveness of the involved sites. Studies have shown the prognostic value of PET volumetry and measures of total uptake. PSMA MTVtotal of high volume disease is a statistically significant poor prognostic factor for overall survival, and PSMA uptake of all metastases (SUVmean per patient) improves prognostication of overall survival in patients treated with 177Lu-lutetium-PSMA-617 therapy (12,24–27).

The recently proposed PSMA PET progression criteria recommend assuming progressive prostate cancer in the setting of a 30% tumor volume increase (8). However, this threshold was chosen arbitrarily in the absence of volume-based PSMA repeatability data. Also, there are currently no consensus recommendations for PSMA PET segmentation algorithms among the various approaches that have been proposed for quantifying the PSMA tumor volume (9,10). A necessary step toward use of PSMA PET for reliable monitoring of disease is development of reliable and efficient methods for measuring total disease burden and determination of their repeatability.

Our analysis of repeatability evaluated PET volumetric and uptake measures using 3 different approaches to segmentation: manual segmentation of individual tumors, manual selection of a subgroup of tumors per patient, and semiautomatic segmentation of total tumor burden per patient. The repeatability of individual tumor volumes (MTVlesion) was poor (RC, 77%). An explanation may be that the reported wCV for SUVmax (12%–14%, Pollard et al. (13)), combined with a volumetric measurement in which a small change in radius from the 50% SUVmax threshold results in a large change in volume, predictably results in large variability. Therefore, monitoring disease on the basis of individual manually segmented tumors does not appear to be a reliable marker for treatment response. The RC for subgroup MTVmean and total MTVmean was 33% and 35%, respectively, which is similar to that reported in the literature for 18F-FDG for other cancers (28,29). An MTV based on a larger sample of tumors or total tumor volume rather than individual tumors appears to be more reliable, likely because the noise-sensitive SUVmax-based thresholds and resulting volume differences have both plus and minus biases across all lesions, resulting in a tendency to cancel out. Although robust, the method based on selection of a subgroup of tumors would be time-consuming in clinical practice and prone to bias in lesion selection. Because of the limited data available, no clear recommendation for a minimum number of lesions for the subgroup of lesions can be made; moreover, the repeatability of quantified volume is likely influenced by the characteristics of the chosen lesions (e.g., lesion size and tissue type). MTVtotal remains robust even when alternating readers between baseline and follow-up scans, suggesting that this method would hold up in clinical practice when scans are not always read by the same person. Therefore, the standardized semiautomatic segmentation method for MTVtotal proposed by Seifert et al., which worked well in this study, may be a solution (9). Future investigation should focus on the fully automatic analysis of PSMA PET scans in analogy to 18F-FDG PET approaches (30). MTVtotal showed a moderate correlation with prostate-specific antigen, suggesting that further assessment of this metric for use as a surrogate biomarker for disease status is warranted.

Besides volumetry, we evaluated SUV measures, which showed repeatability similar to that reported by Pollard et al. (13). We also evaluated PSMA-TL and PSMA-TLQ, metrics that integrate tumor volume and uptake analogous to total lesion glycolysis for 18F-FDG. These metrics showed poor repeatability in individual lesions, but improved repeatability for the subgroup of tumors and total tumor burden, and thus warrant further investigation (12). Interestingly, PMA-TLQ had greater variability than PSMA-TL. This might be partly explained by the fact that the tumor volume is normalized with the relatively stable (i.e., high-repeatability) SUVmean. Thereby, changes in the tumor volume have a larger influence on the resulting composite metric.

The present study had some limitations. The fact that patient number was relatively small might influence the translatability to a larger patient population. The results might not be directly translatable to other PSMA ligands, especially to those that are conjugates with nongallium radioisotopes. The segmentation technique may cause difficulties when single lesions are segmented separately in follow-up scans or when confluent lesions occur (Fig. 2). However, manual user-dependent adjustments can eliminate those artifacts. Finally, the test–retest dataset was performed under carefully controlled conditions (e.g., ensuring the same scanner for scans 1 and 2, minimizing variation in uptake time and dose), which do not reflect the potential variations encountered in the real-world clinic setting.

CONCLUSION

68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET–derived MTVtotal with semiautomatic whole-body segmentation is highly repeatable and suitable for monitoring disease in advanced prostate cancer. Other methods evaluated in this study, such as single-lesion volumes and subgroup of lesions per patient, are limited by inferior repeatability (MTVlesion) or labor intensiveness (MTVsubgroup). MTVtotal therefore presents an efficient and robust means of monitoring disease longitudinally. A change of greater than 35% in the magnitude of MTVtotal can be viewed as a real change in tumor status progression or response to therapy.

DISCLOSURE

Janet H. Pollard has been an investigator for Progenics (Advanced Accelerator Applications) and Endocyte (Novartis) and has received compensation for work done for KEOSYS/Exini. Boris Hadaschik reports a consulting or advisory role at ABX, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Lightpoint Medical, Inc.; research funding from Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, German Cancer Aid, and the German Research Foundation; and travel accommodations and expenses from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. Wolfgang Fendler was a consultant for BTG and received fees from RadioMedix, Bayer, and Parexel outside the submitted work. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS.

QUESTION: What is the estimated test–retest repeatability of whole-body MTVtotal for 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET/CT in patients with metastatic prostate cancer?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: This study evaluated the test–retest repeatability of semiautomatic segmentation of whole-body MTVtotal, showing a wCV of 12.7% and an RC of ±35%. The repeatability of manually segmented individual tumors (MTVlesion) was poor, whereas the repeatability of a manually selected subgroup of tumors per patient (MTVsubgroup) was robust but limited by labor intensiveness.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: Understanding test–retest repeatability for metrics of metastatic disease burden is important for the development of 68Ga PSMA HBED-CC PET/CT as a quantitative imaging biomarker. This study suggests that semiautomatically segmented whole-body MTVtotal is efficient and robust for monitoring disease status.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM, et al. Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the prostate cancer clinical trials working group 3. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1402–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denmeade SR, Sokoll LJ, Dalrymple S, et al. Dissociation between androgen responsiveness for malignant growth vs. expression of prostate specific differentiation markers PSA, hK2, and PSMA in human prostate cancer models. Prostate. 2003;54:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yuan TC, Veeramani S, Lin MF. Neuroendocrine-like prostate cancer cells: neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fendler WP, Calais J, Eiber M, et al. Assessment of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET accuracy in localizing recurrent prostate cancer: a prospective single-arm clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet. 2020;395:1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fanti S, Goffin K, Hadaschik BA, et al. Consensus statements on PSMA PET/CT response assessment criteria in prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fanti S, Hadaschik B, Herrmann K. Proposal for systemic-therapy response-assessment criteria at the time of PSMA PET/CT imaging: the PSMA PET progression criteria. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:678–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seifert R, Herrmann K, Kleesiek J, et al. Semiautomatically quantified tumor volume using 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET as a biomarker for survival in patients with advanced prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1786– 1792 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gafita A, Bieth M, Krönke M, et al. qPSMA: semiautomatic software for whole-body tumor burden assessment in prostate cancer using 68Ga-PSMA11 PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1277–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grubmüller B, Senn D, Kramer G, et al. Response assessment using 68Ga-PSMA ligand PET in patients undergoing 177Lu-PSMA radioligand therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1063–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seifert R, Kessel K, Schlack K, et al. PSMA PET total tumor volume predicts outcome of patients with advanced prostate cancer receiving [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in a bicentric analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1200–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollard JH, Raman C, Zakharia Y, et al. Quantitative test-retest measurement of 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC in tumor and normal tissue. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJG, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging—version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:328–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obuchowski NA. Interpreting change in quantitative imaging biomarkers. Acad Radiol. 2018;25:372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rahbar K, Afshar-Oromieh A, Jadvar H, Ahmadzadehfar H. PSMA theranostics: current status and future directions. Mol Imaging. 2018;17:1536012118776068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rahbar K, Weckesser M, Ahmadzadehfar H, Schafers M, Stegger L, Bogemann M. Advantage of 18F-PSMA-1007 over 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET imaging for differentiation of local recurrence vs. urinary tracer excretion. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1076–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fendler WP, Weber M, Iravani A, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen ligand positron emission tomography in men with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:7448–7454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farolfi A, Hirmas N, Gafita A, et al. Identification of PCWG3 target populations is more accurate and reproducible with PSMA PET than with conventional imaging: a multicenter retrospective study. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weber M, Kurek C, Barbato F, et al . PSMA-ligand PET for early castration-resistant prostate cancer: a retrospective single-center study. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eiber M, Herrmann K, Calais J, et al. Prostate cancer molecular imaging standardized evaluation (PROMISE): proposed miTNM classification for the interpretation of PSMA-ligand PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1652–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen Y-H, Carducci MA, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1080–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sweeney CJ, Chen Y-H, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seifert R, Seitzer K, Herrmann K, et al. Analysis of PSMA expression and outcome in patients with advanced prostate cancer receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:7812–7820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kramer GM, Frings V, Hoetjes N, et al. Repeatability of quantitative whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT uptake measures as function of uptake interval and lesion selection in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kruse V, Mees G, Maes A, et al. Reproducibility of FDG PET based metabolic tumor volume measurements and of their FDG distribution within. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;59:462–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sibille L, Seifert R, Avramovic N, et al . 18F-FDG PET/CT uptake classification in lymphoma and lung cancer by using deep convolutional neural networks. Radiology. 2020;294:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]