Visual Abstract

Keywords: FAPI, theranostics, fibroblast activation protein, solid tumors

Abstract

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is overexpressed in several solid tumors and therefore represents an attractive target for radiotheranostic applications. Recent investigations demonstrated rapid and high uptake of small-molecule inhibitors of FAP (68Ga-FAPI-46) for PET imaging. Here, we report our initial experience of the feasibility and safety of 90Y-FAPI-46 for radioligand therapy of extensively pretreated patients with solid tumors. Methods: Patients were considered for 90Y-FAPI-46 therapy if they showed both an exhaustion of all approved therapies based on multidisciplinary tumor board decision, and high FAP expression, defined as SUVmax greater than or equal to 10 in more than 50% of all lesions. If tolerated, 90Y-FAPI-46 bremsstrahlung scintigraphy was performed after therapy to confirm systemic distribution and focal tumor uptake, and 90Y-FAPI-46 PET scans were performed at multiple time points to determine absorbed dose. Blood-based dosimetry was used to determine bone marrow absorbed dose. Adverse events were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0). Results: Nine patients either with metastatic soft-tissue or bone sarcoma (n = 6) or with pancreatic cancer (n = 3) were treated between June 2020 and March 2021. Patients received a median of 3.8 GBq (interquartile range [IQR], 3.25–5.40 GBq) for the first cycle, and 3 patients received subsequent cycles with a median of 7.4 GBq (IQR, 7.3–7.5 GBq). Posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 bremsstrahlung scintigraphy demonstrated sufficient 90Y-FAPI-46 uptake in tumor lesions in 7 of 9 patients (78%). Mean absorbed dose was 0.52 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.41–0.65 Gy/GBq) in the kidney, 0.04 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.03–0.06 Gy/GBq) in bone marrow, and less than 0.26 Gy/GBq in the lung and liver. Measured tumor lesions received up to 2.28 Gy/GBq (median, 1.28 Gy/GBq). New laboratory G3 or G4 toxicities were noted in 4 patients (44%, n = 2 patients with thrombocytopenia only, n = 2 patients with new onset of thrombocytopenia and anemia). Other G3 or G4 laboratory-based adverse events occurred in 2 patients or fewer. No acute toxicities attributed to 90Y-FAPI-46 were noted. Radiographic disease control was noted in 4 patients (50%). Conclusion: FAP-targeted radioligand therapy with 90Y-FAPI-46 was well tolerated, with a low rate of attributable adverse events. Low radiation doses to at-risk organs suggest feasibility of repeat cycles of 90Y-FAPI-46. We observed signs of tumor response, but further studies are warranted to determine efficacy and the toxicity profile in a larger cohort.

The fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is expressed by cancer-associated fibroblasts as well as cancer cells such as sarcoma and mesothelioma (1–3). Therefore, FAP is an attractive target for both imaging and radionuclide therapy of solid tumors. Previously, several groups have described high tumor uptake for 68Ga- or 18F-labeled PET compounds (4–9). For imaging, we used the FAP-targeted inhibitor FAPI-46 for diagnostic work-up of cancer types such as pancreatic cancer and sarcoma (10,11).

Recently, FAP-targeted radioligand therapy (RLT) has been described in several case reports (12–14); however, feasibility has not yet been systematically analyzed. In this case series, 90Y-labeled FAPI-46 (90Y-FAPI-46) RLT was offered to patients with advanced-stage solid tumors who have exhausted all established lines of treatment. 90Y features high-branching-ratio β− emission (99.99%) with an endpoint energy of 2.280 MeV, allowing high dose deposition within defined tumor lesions. Its relatively short half-life of 64.1 h makes it appropriate for therapeutic combinations in which the biochemical vector exhibits a short target retention time. Preclinical studies on FAPI-46 have demonstrated a decrease to 30% of tumor uptake from 1 to 24 h after injection (14). Posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 scintigraphy is performed by measuring the β− emission–associated bremsstrahlung radiation. 90Y decays by internal conversion (0.0032%), emitting a positron with a total kinetic energy of 0.760 MeV. Positron emission enables PET quantitative data for dosimetry (15).

In this study, we report on the safety, dosimetry, and response for repeat 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT in patients with advanced solid tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

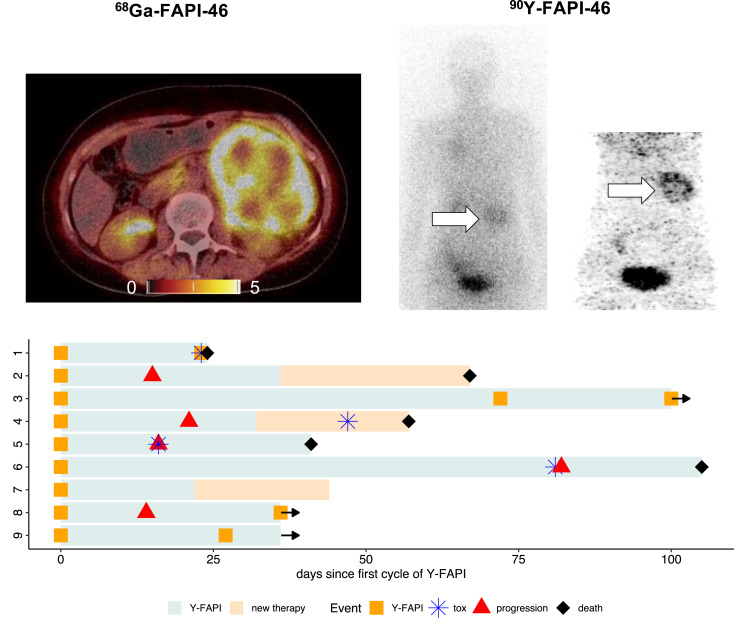

This was a monocentric, retrospective study of 9 patients with progressive, advanced-stage solid tumors receiving 90Y-FAPI-46 under compassionate access for a clinical indication. Radionuclide treatment was recommended by a multidisciplinary tumor board. All patients either had previously progressed during established treatment options or were not eligible to receive other treatments. This study was approved by the institutional review board (reference 21-9842-BO). All patients provided written informed consent to undergo clinical RLT and for retrospective analysis of clinical data. All patients underwent PET imaging with 68Ga-FAPI-46 before treatment to confirm the FAP positivity of tumor lesions, defined as an SUVmax greater than or equal to 10 in more than 50% of all lesions (Fig. 1). Imaging procedures were described previously (10); in brief, patients received a median of 103 MBq of 68Ga-FAPI-46 (interquartile range [IQR], 87–133.5 MBq) intravenously and were scanned at a median of 37 min (IQR, 24.5–60 min) after injection. To be eligible for treatment, patients needed adequate bone marrow function (i.e., leukocytes > 2.5/nL, hemoglobin > 7.0 mg/dL, and thrombocytes > 75/nL), with exceptions for patients receiving regular transfusions. Before treatment, renal scintigraphy with 99mTc-MAG3 was performed to rule out urinary tract obstruction.

FIGURE 1.

Pretreatment 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET images and posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 bremsstrahlung scintigraphs after first cycle of 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT. p.i. = after injection.

90Y-FAPI-46 Synthesis

90Y-FAPI-46 was synthesized using the Easyone synthesis module (Trasis) connected to shielded 90Y-YCl3 solution (Yttriga; Eckert and Ziegler). Before the automated synthesis started, the cassette was preloaded with FAPI-46 precursor (ABX, 8 μg/GBq), ascorbic acid, and sodium acetate buffer saline vials. The synthesis was fully automated using a good-manufacturing-practice–grade reagent and controlled by a preprogrammed sequence. The 90Y-YCl3 solution was transferred into the reactor, followed by the precursor and buffer mixture. For radiolabeling, the reaction mixture was heated to 90°C for 20 min. Afterward, the product was transferred into the bulk vial through a sterile filter and formulated with pentetic acid (1 mL, Ditripentat-Heyl; Heyl), ascorbic acid (∼40 mg/GBq, vitamin C; Rotexmedica), and saline. The quality control procedures included reverse-phase–high-performance liquid chromatography, instant thin-layer chromatography, pH, endotoxin, and sterility testing. The average yield was 88% ± 7%, reverse-phase–high-performance liquid chromatography radiochemical purity was 98% ± 1%, concentration was 883 ± 70 MBq/mL, and shelf life was 24 h.

90Y-FAPI-46 Administration

Patients underwent inpatient treatment to ensure radiation safety. Vital signs were monitored before and after administration of 90Y-FAPI-46. Patients 1 and 2 received a planned activity of 7.4 GBq of 90Y-FAPI-46 for the first cycle. All other patients received a planned first activity (scout dose) of 3.8 GBq of 90Y-FAPI-46 with dosimetry. Focal 90Y-FAPI-46 uptake was noted in more than 50% of tumor lesions on posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 bremsstrahlung scintigraphy (Fig. 1), and if clinically indicated, patients were eligible to receive further cycles with 2 doses of 3.8 GBq of 90Y-FAPI-46 (high dose), given on the same therapy day but 4 h apart. We chose fractionated applications to optimize prolonged radiation delivery on the basis of the observed short biologic half-life during scout cycles, which appeared to be less than 24 h. A therapeutic solution was administered intravenously with 500 mL of saline. Bremsstrahlung scintigraphy was performed approximately 24 h or, if possible, 0.5 h after therapy to confirm systemic distribution and focal tumor uptake. Whole-body planar imaging was performed at a scan speed of 10 cm/min, with an energy window of 90 − 125 keV and using a medium-energy collimator. All patients were discharged 48 h after administration, in accordance with radiation protection regulations.

Dosimetry

If tolerated, patients underwent dosimetry after therapy. 90Y-FAPI-46 PET scans were not performed in cases of severe pain, a long acquisition (n = 3 during cycle 1 and n = 1 during cycle 2), or inability to tolerate or allow repeated blood sampling (n = 4). Bone marrow dosimetry was measured using repeated blood samples (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 24, 36, and 48 h after injection) and estimated according to OLINDA/MIRD recommendations. Dose absorbed by tumor lesions and kidneys was estimated using PET acquisitions. PET images were acquired at multiple time points (0.5, 3, and 18–24 h after injection) after 90Y-FAPI-46 application. Data from at least 2 time points were necessary to determine lesion dose. Tumor and organ dosimetry was assessed by analyzing the respective regions of interest in the PET images, from which the pharmacokinetic behavior was fitted to monoexponential functions. Images were acquired in a Siemens mCT or Biograph Vision scanner, following an optimized protocol for quantification (16). PET quantification accuracy was validated in a National Electrical Manufacturers Association phantom, being considered most favorable when scanned in a silicon photomultiplier PET/CT scanner. Maximum liver and lung doses were assessed individually on the basis of minimum measurable 90Y-FAPI-46 uptake in prior PET phantom studies. We considered the number of disintegrations that would take place in the organ, assuming the minimum detectable activity concentration of 100 kBq/mL and the pharmacokinetics observed in blood dosimetry at the standard organ volumetry stated in the OLINDA.

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Toxicity was recorded as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0). Clinical, laboratory, and imaging follow-up was performed as per clinical routine, with laboratory and clinical visits every 2–4 wk and imaging within 1–2 mo. Imaging response was defined as per RECIST (version 1.1) for CT and PERCIST for 18F-FDG PET/CT (17,18). Disease control was defined as complete (metabolic) response, partial (metabolic) response, or stable (metabolic) disease. All patients received baseline imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT to rule out sites of discordant disease. 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed 2 wk after the first cycle in 7 patients (78%) (Supplemental Figs. 1–9; supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). For overall response rate, response was defined as complete (metabolic) response or partial (metabolic) response. Descriptive statistics were used to present data; median and IQR were used for continuous measures, and absolute number and percentage were used for categoric data. No statistical tests were used for this study. All statistical analysis was performed using R statistics (version 3.4.1, www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Nine patients either with metastatic soft-tissue or bone sarcoma (n = 6) or with pancreatic cancer (n = 3) were treated between June 2020 and March 2021 (Table 1). The median age was 57 y (IQR, 55–62 y). At baseline, most patients had a median of 6 (IQR, 2–6.5) previous systemic treatment lines (Table 1) and were progressive during their last regimen. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score for most patients was greater than or equal to 2 (n = 6; 67%), and only 3 patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 1 at baseline (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient no. | Age (y) | Sex | Histology | Tumor sites (primary and metastatic) | Eastern Cooperative Oncology group | No. of previous systemic therapies | Concomitant therapy | Subsequent therapy | 68Ga-FAPI-46 (SUVmax baseline) | Status | Follow-up (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | Male | Osteosarcoma | Lung, heart, lymph nodes | 2 | 7 | — | — | 12.1 | Dead | 24 |

| 2 | 66 | Male | Chordoma | Bone, soft tissue, liver, lung, lymph nodes | 3 | 2 | — | Nivolumab | 22.3 | Dead | 67 |

| 3 | 54 | Female | Fibrosarcoma | Lung, lymph nodes, pancreas, bone | 1 | 6 | — | — | 18.3 | Follow-up | 100 |

| 4 | 57 | Female | PDAC | Liver, lung, lymph nodes, bone | 3 | 2 | — | Cisplatin | 14.9 | Dead | 57 |

| 5 | 61 | Female | PDAC | Pancreas, liver, lung, lymph nodes, bone | 2 | 9 | Trametinib | — | 19.4 | Dead | 41 |

| 6 | 56 | Female | PDAC | Pancreas, liver, lung, lymph nodes, kidney | 2 | 6 | — | 16.5 | Dead | 105 | |

| 7 | 63 | Female | GNET | Lung, liver, lymph nodes, bone, soft tissue | 1 | 3 | — | Nivolumab | 16.1 | Follow-up | 44 |

| 8 | 61 | Male | Conventional chondrosarcoma | Lung, lymph nodes, pancreas, bone | 2 | 1 | — | — | 16.7 | Follow-up | 36 |

| 9 | 56 | Male | Spindle cell sarcoma | Kidney, liver, lung pleura | 1 | 6 | — | — | 28 | Follow-up | 36 |

PDAC = pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; GNET = gastrointestinal neuroectodermal tumor.

Treatment and Dosimetry

Patients received a median dose of 3.8 GBq (IQR, 3.25–5.40 GBq) for the first cycle and 7.4 GBq (IQR, 7.3–7.5 GBq) for any subsequent cycle. Patient 3 received 3 cycles of 90Y-FAPI-46 with a cumulative activity of 18.3 GBq. Patients 8 and 9 each have received 2 cycles of 90Y-FAPI-46 for a total of 11.2 and 10.0 GBq, respectively. All other patients (n = 6) stopped treatment after the first cycle because of lack of focal 90Y-FAPI-46 uptake based on posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 scintigraphy in the tumor after the first cycle (n = 2) or rapid deterioration or death before the second cycle (n = 4).

Median renal absorbed dose was 0.52 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.41–0.65 Gy/GBq; n = 4) per cycle. A median bone marrow absorbed dose of 0.04 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.03–0.06 Gy/GBq; n = 5) was observed over all cycles. Liver and lung dosimetry was considered only for those patients on whom bone marrow dosimetry was performed. The maximum observed dose in liver and lung was less than or equal to 0.26 Gy/GBq, based on the assumptions presented in the methodology section.

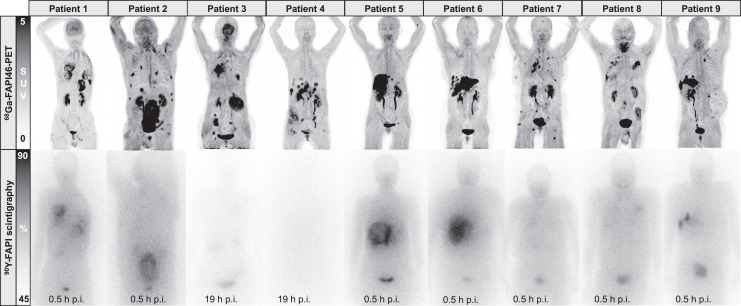

Lesion dosimetry was available for 9 lesions in 6 patients, exemplarily shown for patient 2 (Fig. 2). Median tumor effective half-life was 8.7 h (range, 5.5−18 h). Median dose absorbed by tumor lesions after the first cycle was 1.28 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.83–1.71 Gy/GBq) per cycle for target lesions and 0.95 Gy/GBq (IQR, 0.74–1.32 Gy/GBq) for secondary lesions. The highest doses were observed in patients 6 (1.37 Gy/GBq), 3 (1.23 Gy/GBq), and 9 (2.28 Gy/GBq). For subsequent cycles in patients 3 and 9, a median lesion dose of 1.28 and 2.04 Gy/GBq per cycle was measured, respectively. Table 2 outlines the dosimetry results.

FIGURE 2.

Posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 PET images 4 h after injection with corresponding absorbed dose estimates for 4 lesions in patient 2.

TABLE 2.

90Y-FAPI-46 Administered Activity and Absorbed Doses Per Cycle

| Patient no. | Cycle no. | Activity (GBq) | Radiation dose (Gy/GBq) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor lesion 1 | Tumor lesion 2 | Kidney | Liver and lung* | Bone marrow | |||

| 1 | 1 | 7.1 | 0.74 | 0.63 | — | — | — |

| 2 | 1 | 7.0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | 1 | 3.5 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 0.75 | <0.18 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 7.3 | 1.28 | 0.95 | 0.41 | <0.19 | 0.04 | |

| 3 | 7.5 | 1.47 | 1.35 | 0.61 | <0.15 | 0.04 | |

| 4 | 1 | 3.8 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | 1 | 3.8 | — | — | — | <0.16 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 1 | 3.0 | 1.37 | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | 1 | 3.5 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.52 | <0.16 | 0.03 |

| 8 | 1 | 3.8 | 0.49 | — | 0.11 | <0.26 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 7.4 | — | — | — | — | 0.08 | |

| 9 | 1 | 2.6 | 2.28 | — | 0.65 | <0.21 | 0.04 |

| 2 | 7.4 | 1.79 | — | 0.45 | <0.25 | 0.02 | |

| Median | 1.28 | 0.95 | 0.52 | <0.19 | 0.04 | ||

| IQR | 0.83–1.71 | 0.74–1.32 | 0.41–0.65 | <0.16–0.24 | 0.04–0.07 | ||

Estimation based on maximum detectable activity concentration and blood tracer kinetic.

Adverse Events and Follow-up

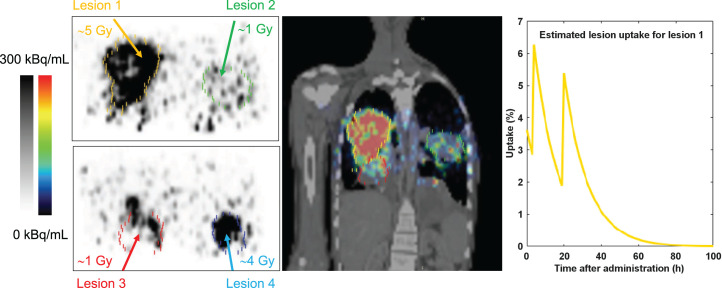

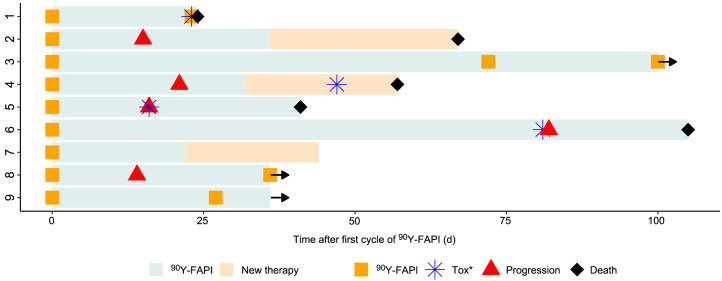

The median follow-up time was 44 d (IQR, 36–83.5 d). Three patients are still receiving RLT and had received 2 or 3 cycles at that point. Five patients died during follow-up. All 5 deaths were considered to be due to tumor progression and not related to 90Y-FAPI-46 (Tables 1 and 3). In patients with progression, the median time until progression or death was 18.5 d (IQR, 14.8–38.5 d). There were no acute or allergic reactions observed immediately after infusion of 90Y-FAPI-46. One patient, with advanced pulmonary metastasis and progressive intratumoral arteriovenous shunts, died because of acute respiratory failure attributed to tumor progression shortly after receiving his second cycle. Another patient developed a fever shortly after her first cycle, which was likely due to acute urinary tract infection and noncompliance with antibiotic medication. At baseline, 5 patients had one or more ongoing toxicities greater than or equal to grade 3. These were anemia (n = 2), increase of alkaline phosphatase (n = 1), or increase of γ-glutamyltransferase (n = 3) (Table 3). During follow-up, 4 patients showed new grade 3 or grade 4 laboratory toxicities (Table 3; Fig. 3). These 4 new adverse events were grade 3 thrombocytopenia (n = 4) possibly related to 90Y-FAPI-46 and were also in temporal relation to either tumor progression or initiation of other concomitant systemic therapy (Fig. 3). One patient showed new grade 3 anemia, and 2 patients showed new increases of hepatic or pancreatobiliary serum markers greater than or equal to grade 3 (Table 3). All 3 of these new adverse events were rated as disease progression, given that all 3 of these patients had pancreatic cancer (Fig. 3). A detailed course of the relevant laboratory parameters is shown in Supplemental Figure 10.

TABLE 3.

Adverse Events After Onset of Treatment, Related or Unrelated

| Laboratory-based AEs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematology | Kidney | Liver | Pancreatobiliary | |||||||||||||||||||||

| WBCs | ANC | Hb | PLTs | sCr | T Bil | AST | ALT | GGT | ALP | Amylase | New G3/G4 AE (laboratory) | |||||||||||||

| Patient no. | General | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | |

| 1 | Acute respiratory distress, tumor-related (G5) | — | — | — | — | G3 | G2 | — | G3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G2 | G1 | G1 | — | — | — | Yes |

| 2 | Tumor pain (G2) | — | — | — | — | — | G1 | — | G1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G1 | G1 | G1 | G1 | — | — | No |

| 3 | None | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G1 | G1 | G1 | G1 | — | — | No |

| 4 | Tumor progression, (G5) | G1 | G2 | — | G1 | G3 | G3 | G1 | G3 | — | G2 | — | G3 | — | G1 | — | — | G1 | G3 | G2 | G2 | — | — | Yes |

| 5 | Tumor progression (G5) | — | — | — | — | G1 | G2 | G1 | G3 | — | G1 | — | G2 | G2 | G4 | G1 | G4 | G3 | G4 | G3 | G3 | — | — | Yes |

| 6 | Pneumonia*, tumor progression (G5) | — | — | — | — | G1 | G3 | G1 | G3 | — | G2 | — | G2 | — | G2 | — | — | G3 | — | G1 | G2 | — | — | Yes |

| 7 | Fever, urinary tract infection* | — | — | — | — | G1 | G2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | No |

| 8 | None | — | — | — | — | G1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G1 | G1 | G1 | — | — | No |

| 9 | None | — | — | — | — | G1 | G1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | G3 | G3 | G2 | G2 | — | — | No |

| Any new AE (%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | 3 (33%) | 3 (33%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (11%) | 3 (33%) | 1 (11%) | — | |||||||||||||

| Any new G3/G4 AE (%) | — | — | 1 (11%) | 4 (44%) | — | 1 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (22%) | — | — | |||||||||||||

Relation to 90Y-FAPI-46 was ruled out.

AE = adverse event; WBCs = white blood cells; ANC = absolute neutrophil count; Hb = hemoglobin; PLTs = platelets (thrombocytes); sCr = serum creatinine; T Bil = total bilirubin; AST = aspartate transaminase; ALT = alanine transaminase; GGT = γ-glutamyltransferase; ALP = alkaline phosphatase; B = baseline; F = follow-up.

G grade is defined as per CTCAE, version 5.0.

FIGURE 3.

Swimmer plot of patients who received 90Y-FAPI-46. Arrows indicate patients continuing 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT at time of analysis. *Any new onset of toxicity greater than or equal to grade 3 according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0).

Response Evaluation

Radiologic response as per RECIST (version 1.1) was available for 8 patients. The median time between imaging and the first cycle of 90Y-FAPI-46 was 16 d (IQR, 15–41 d). Disease control (stable disease) was noted in 4 of 8 patients (50%). No responses had been observed by the time of analysis. However, patient 3 had marked regression of a target lesion (−28%; Supplemental Fig. 3) after the first cycle with 3.5 GBq. Metabolic response as per PERCIST (version 1.0) was available for 7 patients. Disease control was noted in 2 of 7 patients (29%), consisting of stable metabolic disease in one patient (14%; Supplemental Fig. 3) and partial metabolic response in the other (14%; Supplemental Fig. 9). Radiologic responses are outlined in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Radiologic and Metabolic Best Overall Response

| Patient no. | CT target response | CT nontarget response | RECIST response | PET target response | PET nontarget response | PERCIST response | SUVmax 18F-FDG baseline | SUVmax 18F-FDG follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SD | SD | SD | PMR | SMD | PMD | 14.8 | 21.8 (+47%) |

| 2 | PD | SD | PD | PMD | PMD | PMD | 28.6 | 22.3 (−22%) |

| 3 | SD | SD | SD | SMD | SMD | SMD | 6.5 | 4.9 (−25%) |

| 4 | PD | PD | PD | SMD | PMD | PMD | 5.1 | 3.8 (−26%) |

| 5 | PD | PD | PD | SMD | PMD | PMD | 18.9 | 17.2 (−9%) |

| 6 | SD | SD | SD | — | — | — | 6.1 | — |

| 7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 14.3 | — |

| 8 | SD | PD | PD | PMD | SMD | PMD | 12.5 | 13.3 (+6.4%) |

| 9 | SD | SD | SD | PMR | SMD | PMR | 18 | 10.1 (−44%) |

| DCR (%) | 4/8 (50%) | 2/7 (29%) | ||||||

| ORR (%) | 0/8 (0%) | 1/7 (14%) |

SD = stable disease; PMR = partial metabolic response; SMD = stable metabolic disease; PMD = progressive metabolic disease; PD = progressive disease; DCR = disease control rate; ORR = overall response rate.

DISCUSSION

We here report the first case series of patients with advanced-stage solid tumors treated with 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT. Repeated 90Y-FAPI-46 applications with individual dosimetry were used to ensure the safety of each patient and a maximum likelihood of treatment effect. For treatment initiation, patients had to have high uptake on 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET in most tumor lesions, and for treatment continuation, patient had to have focal uptake on the first posttreatment 90Y-FAPI-46 bremsstrahlung scintigraphy (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. 1–9). Patients had exhausted all available on-label or evidence-based treatment options, and the most prevalent Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score was 2 or higher. Treatment with 90Y-FAPI-46 was offered under compassionate use with the intent of achieving antitumor effect with manageable toxicity. On the basis of the biodistribution observed on 68Ga-FAPI-46, PET RLT using 90Y-FAPI-46 was expected to deliver therapeutic radiation doses to the tumor while sparing organs at risk (4,11). Acute toxicities or immediate (e.g., allergic) reactions to RLT were not observed. During follow-up, adverse events began in almost all patients. However, only a small proportion was attributed to 90Y-FAPI-46, given that most adverse events occurred after tumor progression or the switch of systemic therapy (Fig. 3). Additionally, we noted that toxicity in 1 patient who had received multiple RLT cycles with a cumulative activity of 18.3 GBq was limited to G1 thrombocytopenia. Ultimately, randomized trials on patients with symptomatic disease are needed for more detailed assessment of toxicity. Data from previous randomized trials evaluating 177Lu-PSMA-617 or 177Lu-DOTATATE identified hematotoxicity, especially thrombocytopenia, as a relevant (i.e., frequently occurring as grade 3/4) side effect (19,20). On the basis of our data, we expect a similar toxicity profile for 90Y-FAPI-46. Therefore, repeated cycles of 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT seem feasible, because the doses absorbed by the kidneys, bone marrow, liver, and lungs were low and comparable to those of other small-ligand 90Y therapies (21). In our cohort, 3 patients received multiple cycles with a maximum cumulative activity of up to 18.3 GBq.

When all other available therapeutic options fail, achieving disease control is the primary goal for a novel therapy. Previously, Kratochwil et al. reported on a patient with spindle cell soft-tissue sarcoma who had a long period of stable disease under FAPI-46 RLT (12). Although the follow-up time is still short, we observed radiographic disease control in about half the patients, along with signs of tumor response. Patient 3 experienced meaningful benefit in the form of stable disease for over 4 mo, with regression of a large pancreatic tumor mass. Patient 9 showed a partial metabolic response and achieved the highest lesion dose with 13.2 Gy during cycle 2. Patients 3, 8, and 9 had additional cycles pending at the time of analysis. Interestingly, 3 of the 4 patients with disease control were patients with soft-tissue (n = 2) or bone (n = 1) sarcoma. The fourth patient had pancreatic cancer and received concomitant treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor afatinib, which was well tolerated, therefore indicating the potential feasibility of combination therapy. In the quest to provide the most efficacious therapy with acceptable toxicity, especially in nonresponders, 2 future strategies should be considered: first, a more intense treatment regimen (i.e., short intercycle intervals or higher activities) and, second, RLT drug combination therapy. FAP and cancer-associated fibroblasts are drivers of immune escape (22,23); therefore, immunotherapy might be a rationale companion for FAP-targeted RLT. Preclinical studies in several cancer types suggest a synergistic effect of FAP targeting and immunotherapy (24–27). Recently, a case report showed good tolerance of 177Lu-PSMA RLT in combination with pembrolizumab or sequentially after olaparib (28), which is currently being investigated in ongoing prospective phase 1/2 trials (NCT03874884, NCT03805594).

90Y-FAPI-46 has a shorter half-life and higher energy per decay than 177Lu-PSMA. Because of the short retention time in the tumor as described by Lindner et al. (14), 90Y-FAPI-46 seemed more suitable for achieving therapeutic radiation doses in a tumor. 90Y-FAPI-46 PET-based dosimetry has been successfully used for hepatic radioembolization dosimetry, after administration of 90Y-labeled spheres (29). Phantom studies suggest that recent developments in sensitivity and timing resolution for PET scanners could be advantageous for accurate 90Y quantification, (16) which could play a decisive role in the validation of 90Y-labeled therapeutic drugs.

This study comes with limitations. The low number of patients and absence of a predefined imaging follow-up protocol does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of 90Y-FAPI-46. Further research to determine radiation dosimetry for 90Y-FAPI-46 is warranted, because quantification and subsequent dosimetry are limited by the decay characteristics of 90Y-FAPI-46 and the relatively low activity concentration in tissues. A low activity concentration combined with detector limits impairs accurate acquisition of the true lung and liver doses. However, the aim of this study was to report the initial clinical experience and to demonstrate the feasibility of 90Y-FAPI-46 RLT.

CONCLUSION

FAP-targeted RLT with 90Y-FAPI-46 was well tolerated, with a low rate of attributable adverse events, including thrombocytopenia. We found low radiation doses to the kidney and bone marrow, suggesting the feasibility of repeated cycles of 90Y-FAPI-46. Although we observed the first signs of therapeutic efficacy, larger trials are needed to determine efficacy and the toxicity profile.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the nurses and technicians of the nuclear medicine team for their ongoing logistic support.

DISCLOSURE

Justin Ferdinandus has received a Junior Clinician Scientist Stipend granted by the University Duisburg–Essen and has received fees from Eisai. Lukas Kessler is a consultant for AAA and BTG and received fees from Sanofi. Manuel Weber is on the speaker’s bureau for Boston Scientific. Sebastian Bauer reports personal fees from Bayer, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and PharmaMar; serves in an advisory/consultancy role for ADC Therapeutics, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Janssen-Cilag, Nanobiotix, Novartis, PharmaMar, Plexxikon, and Roche; receives research funding from Novartis; and serves as a member of the external advisory board of the Federal Ministry of Health for “off-label use in oncology.” Martin Schuler reports personal fees as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MorphoSys, Novartis, Roche, and Takeda; honoraria for continuing medical education presentations from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, MSD, and Novartis; and research funding to the institution from AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers-Squibb. Jens Siveke reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Immunocore, Baxalta, Aurikamed, Falk Foundation, iomedico, Shire, and Novartis; received grants and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Roche; has minor equity in FAPI Holding and Pharma15 (<3%); and is a member of the board of directors for Pharma15. Ken Herrmann reports personal fees from Bayer, Sofie Biosciences, SIRTEX, Adacap, Curium, Endocyte, IPSEN, Siemens Healthineers, GE Healthcare, Amgen, Novartis, ymabs, Aktis, Oncology, and Pharma15; nonfinancial support from ABX; and grants and personal fees from BTG. Wolfgang Fendler is a consultant for BTG and received fees from RadioMedix, Bayer, and Parexel. Rainer Hamacher is supported by the Clinician Scientist Programm of the University Medicine Essen Clinician Scientist Academy sponsored by the Faculty of Medicine and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and has received travel grants from Lilly, Novartis, and PharmaMar, as well as fees from Lilly. All disclosures are outside the submitted work. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Is radionuclide therapy with 90Y-FAPI-46 feasible for patients with advanced-stage solid tumors, and what are the side effects and absorbed doses?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: 90Y-FAPI-46 leads to therapeutic irradiation of tumor lesions, and the radiation exposure of critical organs is low. Further, we observed, after a short follow-up, a low rate of toxicities, including thrombocytopenia, attributed to 90Y-FAPI-46 in patients with advanced and symptomatic disease.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: Radionuclide therapy with 90Y-FAPI-46 seems to be well tolerated, and repeated cycles are possible.

REFERENCES

- 1. Henry LR, Lee HO, Lee JS, et al. Clinical implications of fibroblast activation protein in patients with colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1736–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen SJ, Alpaugh RK, Palazzo I, et al. Fibroblast activation protein and its relationship to clinical outcome in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2008;37:154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dohi O, Ohtani H, Hatori M, et al. Histogenesis-specific expression of fibroblast activation protein and dipeptidylpeptidase-IV in human bone and soft tissue tumours. Histopathology. 2009;55:432–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer C, Dahlbom M, Lindner T, et al. Radiation dosimetry and biodistribution of 68Ga-FAPI-46 PET imaging in cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1171–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen H, Pang Y, Wu J, et al. Comparison of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-FAPI-04 and [18F] FDG PET/CT for the diagnosis of primary and metastatic lesions in patients with various types of cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1820–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giesel FL, Kratochwil C, Lindner T, et al. 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT: biodistribution and preliminary dosimetry estimate of 2 DOTA-containing FAP-targeting agents in patients with various cancers. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:386–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koerber SA, Staudinger F, Kratochwil C, et al. The role of 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT for patients with malignancies of the lower gastrointestinal tract: first clinical experience. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:1331–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Syed M, Flechsig P, Liermann J, et al. Fibroblast activation protein inhibitor (FAPI) PET for diagnostics and advanced targeted radiotherapy in head and neck cancers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:2836–2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kratochwil C, Flechsig P, Lindner T, et al. 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT: tracer uptake in 28 different kinds of cancer. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:801–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kessler L, Ferdinandus J, Hirmas N, et al. Ga-68-FAPI as diagnostic tool in sarcoma: data from the FAPI-PET prospective observational trial. J Nucl Med. April 30, 2021. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferdinandus J, Kessler L, Hirmas N, et al. Equivalent tumor detection for early and late FAPI-46 PET acquisition. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:3221–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kratochwil C, Giesel FL, Rathke H, et al. [153Sm]Samarium-labeled FAPI-46 radioligand therapy in a patient with lung metastases of a sarcoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:3011–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ballal S, Yadav MP, Kramer V, et al. A theranostic approach of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA.SA.FAPi PET/CT-guided [177Lu]Lu-DOTA.SA.FAPi radionuclide therapy in an end-stage breast cancer patient: new frontier in targeted radionuclide therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:942–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lindner T, Loktev A, Altmann A, et al. Development of quinoline-based theranostic ligands for the targeting of fibroblast activation protein. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1415–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright CL, Zhang J, Tweedle MF, Knopp MV, Hall NC. Theranostic imaging of yttrium-90. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:481279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunnen B, Beijst C, Lam M, Viergever MA, de Jong H. Comparison of the Biograph Vision and Biograph mCT for quantitative 90Y PET/CT imaging for radioembolisation. EJNMMI Phys. 2020;7:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50 (suppl 1):122S–150S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-Dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hofman MS, Emmett L, Sandhu S, et al. [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Imhof A, Brunner P, Marincek N, et al. Response, survival, and long-term toxicity after therapy with the radiolabeled somatostatin analogue [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in metastasized neuroendocrine cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2416–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ziani L, Chouaib S, Thiery J. Alteration of the antitumor immune response by cancer-associated fibroblasts. Front Immunol. 2018;9:414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fearon DT. The carcinoma-associated fibroblast expressing fibroblast activation protein and escape from immune surveillance. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20212–20217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kraman M, Bambrough PJ, Arnold JN, et al. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science. 2010;330:827–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wen X, He X, Jiao F, et al. Fibroblast activation protein-alpha-positive fibroblasts promote gastric cancer progression and resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Oncol Res. 2017;25:629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen L, Qiu X, Wang X, He J. FAP positive fibroblasts induce immune checkpoint blockade resistance in colorectal cancer via promoting immunosuppression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;487:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prasad V, Zengerling F, Steinacker JP, et al. First experiences with 177Lu-PSMA therapy in combination with pembrolizumab or after pretreatment with olaparib in single patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:975–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lhommel R, van Elmbt L, Goffette P, et al. Feasibility of 90Y TOF PET-based dosimetry in liver metastasis therapy using SIR-Spheres. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1654–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]