Abstract

Reflective conversations between teachers and coaches are critical to helping teachers improve their classroom instruction. Coaches who encourage teachers to “see, think, and do” are better able to facilitate meaningful reflective conversations with teachers. The “See, Think, Do” framework consists of six steps (observe, describe, process, analyze, draw conclusions, and plan) that can be used to help coaches engage in reflective conversations with teachers. The framework can be readily implemented in remote and face-to-face coaching modalities and in one-on-one and small group delivery formats. Suggestions and strategies for implementing the framework in ongoing coach-teacher conversations are provided.

Keywords: Coaching, Video reflection, Reflective conversations, Early childhood teachers

Patricia (all names are pseudonyms), a pre-kindergarten teacher, and her coach meet together for the third time during the school year. Patricia had identified read alouds as an area for improvement and worked with her coach to set specific goals around vocabulary support during her read alouds. Patricia recorded a read aloud delivered in a small group session to discuss with her coach. In their next remote coaching session, the coach and Patricia focus on the recorded clip about the read aloud. Patricia starts by giving the coach some background on the lesson, prior to watching the recording. Patricia and the coach start by watching three minutes of the video clip together. Here is an excerpt from their reflective conversation that follows after watching the video clip:

Coach: Tell me what happened in this video clip. What did you see and hear?

Patricia: I read part of the story out loud to the students, and I asked them to remind me what the word “stray” meant in the story. Some of the students kept repeating “a stray puppy” and I said “but what does stray mean? Stray means that the puppy doesn’t have a…” And then one student was able to say “a home”

Coach: Great, let’s pause right here. Tell me more about how you felt and what you noticed about how students responded.

Patricia: I was surprised that the students still didn’t remember what the word ‘stray’ meant even though I explained what ‘stray’ meant at the beginning of the lesson. I did notice that the prompt I used helped them to remember what the word meant.

Coach: Yes, that was a great way to provide a downward scaffold for when the students didn’t know what the word ‘stray’ meant. Why do you think the students may not have remembered what the word ‘stray’ meant?

Patricia: Hm, they may not have understood my explanation at the beginning of the lesson. Maybe I didn’t spend enough time talking about the word.

Coach: Tell me a little more about how you explained the word “stray” to them.

Patricia: I told the students that a stray dog is a dog that doesn’t have a home.

Coach: That’s a great child-friendly definition for the word stray. What else do you think you could have done to help them understand the word stray aside from a child-friendly definition?

Patricia: Maybe I could have shown them a picture of a dog living on a street or something.

Coach: Yes, adding that visual would be a great way to add to the child-friendly definition you gave them at the beginning of the lesson. It can help make a word like “stray” easier to understand. Tell me about what you would do the same and what you might change about this activity for next time.

Patricia: I would add more visual pictures or even ways to act out words when I want to introduce new vocabulary words for these students. I thought the child-friendly definitions still work well and as a backup, it might be good to use some prompts in case students forget about what words mean.

After the reflective conversation, Patricia works with her coach to make a plan for next time. Patricia includes the ideas for visuals and actions when planning her next small group read aloud lesson. In this excerpt, the coach wanted Patricia to pay attention to how she introduced vocabulary words from read alouds to her students. Although the coach could have simply told Patricia that it would have been helpful to supplement the child-friendly definition with a visual, Patricia was able to draw that conclusion independently by going through a reflective cycle. Patricia had an opportunity to first observe and describe the interaction that unfolded in the video clip and she was then able to process why it was important for students to have another way to understand the new vocabulary word. Patricia was able to see this instructional practice in relation to her students’ learning.

Introduction

Coaching-based professional development (PD) programs have gained momentum due to the shortcomings of traditional PD in improving classroom instruction and student achievement (Desimone, 2009). The intensified interest in PD is partly linked to the “last mile” problem, which describes the ongoing divergence between research recommendations and actual instructional practices in early childhood education (Lemons & Toste, 2019; Schneider, 2018). Over the past two decades, U.S. school districts and funding agencies have heavily invested in PD activities intended to support teachers’ use of evidence-based practices and improve children’s learning (Knight, 2019; Schwartz et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2015). Coaching models, an intensive form of PD, can provide sustained and individualized support for teachers (Gibbons & Cobb, 2017; Kane & Rosenquist, 2019), ultimately improving the quality of early childhood classrooms and young children’s learning (Yoon et al., 2007).

Studies of coaching models have highlighted how coaches may be critical to helping teachers attend to moment-based cues and interactions as they happen within classroom contexts (Hamre et al., 2012; Pianta et al., 2017). Key features of effective coaching models include opportunities for teachers to plan lessons with coach support, receive feedback, practice new or modified strategies, and reflect on practice (Dunst, 2015; Romano & Woods, 2018; Snyder et al., 2015). Of these key features, reflection on practice (with the intent of modifying or adapting instruction) is often considered a central, yet challenging, aspect of coach-teacher interactions. Indeed, it can be challenging for coaches to engage teachers in effective reflective conversations (Heineke, 2013). Researchers have found coaches to use more directive or authoritative approaches (e.g., persuading, pressuring), which can impede reflective and responsive conversations between coaches and teachers (Coburn & Woulfin, 2012; Heinke, 2013). Reflective conversations are typically conceptualized as highly collaborative, in which coaches facilitate conversations with teachers based on teacher-identified areas of improvement (Peterson et al., 2009).

Building on a collaborative approach for reflective conversations, we iteratively refined a video reflection coaching approach to help early childhood coaches facilitate stronger reflective conversations with child care and pre-kindergarten teachers. The reflection approach was developed in a series of ongoing and completed research studies (Landry et al., 2009, 2011, 2014) and through ongoing state-based implementation work (Crawford et al., 2020). Most recently, the video reflection coaching process (described below) was used in two experimental studies (Crawford et al., 2021a, 2021b) that found positive effects of an early childhood professional development program on teachers’ instructional qualities. The video reflection framework is generalizable and can be applied across different professional development programs. In the sections below, we describe the video reflection process (“See, Think, Do”) for coach-teacher dialogues and highlight how it can be used with various coaching modalities (e.g., face-to-face, remote) and delivery contexts (e.g., one-on-one, professional learning communities).

Reflective Conversations

Changing teachers’ instructional practices is a challenging endeavor (Inbar-Furst et al., 2020). Reflection helps teachers gain new insights about their teaching practices and learn how to use the insights to improve classroom practices (Walsh et al., 2020). By engaging in reflective coach-teacher dialogues, teachers understand how to identify problems in their instructional practices (Loughran, 2002). A powerful way to help teachers modify existing or adopt new practices is to turn to teachers’ own classroom experiences. Before teachers are able to modify existing or adopt new practices, they must understand why they should change what they are currently doing and how to incorporate the new content to their practice.

Thus, reflective coaching is a critical part of changing how teachers think about and approach instructional interactions with students in their classroom (Peterson et al., 2009). Reflective cycles help teachers to slow down their thinking so they can see “what is rather than what they wish were so” (p. 231) and consider their teaching practices in the context of student learning (Rodgers, 2002).” As teachers hone their reflective skills, they become more thoughtful and intentional about their own practices—they may even develop a greater sense of autonomy over their teaching and students’ learning.

Video Reflection in Early Childhood Classrooms

Video reflection (i.e., video recordings of classroom practices) can help coaches to facilitate reflective dialogues with early childhood teachers. Video reflection approaches have been found to be effective in both face-to-face and remote coaching models (e.g., Artman-Meeker & Hemmeter, 2013; Crawford et al., 2021a, 2021b; Gregory et al., 2017; Landry et al., 2014; Pianta et al., 2008). Video reflection relies on the concept of ‘professional vision,’ which describes how a teacher uses professional and contextual knowledge as they view or interpret interactions in relation to their instructional goals and authentic contexts (Sherin et al., 2007; van Es & Sherin, 2008; Walsh et al., 2020).

The effectiveness of video reflection is largely attributed to its ability to provide a focused forum that is free of classroom constraints (e.g., need for teachers to respond immediately, make immediate decisions) and that allows teachers to revisit interactions, multiple times if necessary. Early childhood teachers often face competing classroom demands and high cognitive demands (e.g., scaffolding instruction based on student signals). Video reflection can be a powerful tool that helps teachers to recognize missed opportunities or consider additional perspectives (e.g., student perspectives), which can lead to improvements in future interactions. Most importantly, the use of video reflection can help teachers to engage in productive inquiry by observing and critiquing their practices in constructive ways (Crawford et al., 2021a, 2021b; Matsumura et al., 2019). For example, Sherin & van Es (2009) examined the use of a researcher-facilitated teacher video club, which consisted of a group of teachers who first viewed video segments and then reflected on specific strategies or student responses together. The study showed that teachers were able to focus more on student responses and think analytically about their instructional practices (e.g., Sherin & van Es, 2009). The video reflection process, which we describe below, is dependent on the support of a coach, who can help the teacher to reflect, analyze, and consider alternative strategies in the context of a shared experience (Borko et al., 2008, p. 419). Coaches play a critical role in the video reflection process, as they can leverage their expertise and knowledge of early childhood practices to support teachers in constructing new knowledge, making inferences or hypotheses, and generating new insights (Marsh & Mitchell, 2014; Walsh et al., 2020).

Video Reflection Coaching Process

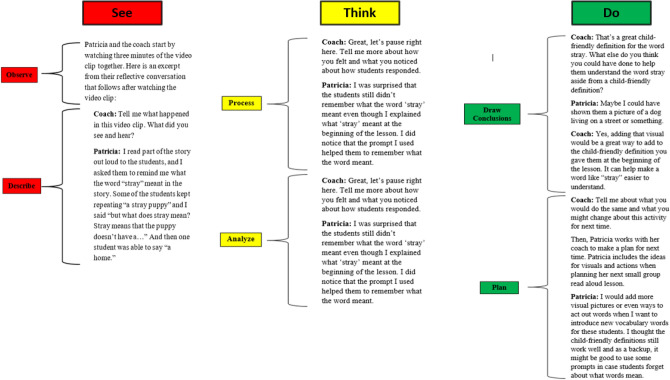

The video reflection coaching process used in previous empirically-tested studies (e.g., Crawford et al., 2021a, 2021b) begins with a teacher identifying priorities and instructional goals for improvement. In current implementation of the video reflection coaching process, coaches and teachers use the Classroom Observation Tool (see Table 1) to identify specific teaching behaviors across 13 content areas (e.g., classroom management, social and emotional development, phonological awareness, math) that teachers would like to prioritize for improvement. Each teaching behavior is leveled to represent foundational skills (Level 1; typically prioritized first), increasingly advanced instructional strategies (Level 2), and highly differentiated instruction (Level 3). Coaches help teachers to select specific teaching behaviors that they would like to improve upon and create action plans that help them achieve the targeted teaching behaviors (recorded in a Short Terms Goal Report). After collaborating on the Short Terms Goals Report, teachers then work to enact the plan discussed with the coach. Teachers may choose to submit a recorded video of how they enacted the plan and demonstrated the specific teaching behaviors. The coach reviews the teacher’s recorded video and selects several clips from the recording that are aligned with the teacher’s specific goals for improvement. The recorded clips may include video annotations (e.g., text, arrows; see Fig. 1 for a sample) or voiceovers that will be discussed during the conversations with the teacher. In addition, the coach considers several factors when selecting video clips, such as: opportunities to provide feedback that are generalizable to multiple areas of practice (e.g., upward or downward scaffolding), student engagement during the lesson/activity, and teacher responses to child cues. The coach is intentional about selecting video clips that highlight both positive examples of teacher practice as well as areas in need of improvement. The video clips (four to five 2–3 min clips) are reviewed with the teacher during the reflective conversations. The coach plays one clip at a time with the teacher. When playing the clip, the coach starts the cycle of helping the teacher to “see,” “think,” and “do” (see Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Sample of classroom observation tool

| Read alouds: during reading | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reads with expression to capture children’s attention (e.g., dramatic tone, special voices for characters, etc.) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 1 | Acknowledges child responses or acknowledges children who initiate their own topic during reading with simple praise or brief acknowledgement (e.g., “Good job”, “You’re right”, repeats child’s comment and/or praises) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 1 | Asks knowledge level, basic questions (have right or wrong answers based on what you can see in illustrations or hear from the words read aloud; e.g., recalls names, events, and descriptions, etc.) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 2 | Gives child-friendly explanation of vocabulary words in text (e.g., “Dangerous means not safe.”) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 2 | Asks children to quickly act out important words or ideas in story (e.g., “Let’s all pretend to tremble like we’re scared.”) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 2 | Encourages children to say/repeat a vocabulary word with the teacher |

□ OB □ NS |

| 2 | Builds or expands on child responses by adding more information with more than simple praise/brief acknowledgement (e.g., Child: “It’s a giraffe!” Teacher: “Giraffes have really long necks;” Child: “He’s mean!” Teacher: “I agree with you that he’s being mean. I think he is a bully.”) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 3 | Models or encourages children to think about the purpose for listening discussed before reading (e.g., “We were thinking about…”) |

□ OB □ NS |

| 3 | Models or thinks aloud to draw attention to a comprehension strategy (e.g., making connections, making predictions, summarizing, asking questions, using prior knowledge, comparing/contrasting, making inferences) (e.g., Teacher says, “I have a question about this book. Why does the …?” Teacher says, “This picture makes me wonder about …”) |

□ OB □ NS |

OB observed, NS needs support

Fig. 1.

Samples of video annotations

Fig. 2.

Framework for reflective conversations

Each step within the “See, Think, Do” framework helps to slow down the way teachers process and react to observations of their teaching practices (Rodgers, 2002). Teachers juggle many responsibilities (often simultaneously) in their classrooms (Winton et al., 2015). For example, teachers are often responsible for implementing specific curricula or programs, managing classroom routines, and responding to student signals and needs. Many of these responsibilities require teachers to respond and make decisions immediately. In day-to-day practice, teachers may not have many opportunities to fully process and understand implications of their teaching practices. This makes it especially important to guide teachers through a structured and sequential reflective approach. Teachers who develop skills to reflect “on the moment” are better positioned to reflect in the moment (e.g., during an activity/interaction).

The six-step “See, Think, Do” framework can be used with different coaching models (e.g., face-to-face, remote coaching) and contexts (e.g., one-on-one, small groups). With rapid transitions to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, approaches such as video reflection may be a practical way to continue supporting teachers and helping them meet their goals. In Table 2, we show how a video reflection approach can be applied in both remote and face-to-face coaching sessions and in one-on-one and small group delivery formats.

Table 2.

Coaching modality and coaching context matrix

| Remote coaching | Face-to-face | |

|---|---|---|

| One-on-one |

Use videoconference platform (e.g., Skype, Zoom, FaceTime) Share video so that both viewers (e.g., coach and teacher) are able to view video simultaneous on screen |

Record teacher implementation of a lesson/activity during an observation OR ask teacher to record a lesson/activity Share the recorded video during a debrief with a teacher with a focus on the teacher’s goals/priorities for improvement |

| Small Group (e.g., professional learning communities) |

Use videoconference platform (e.g., Skype, Zoom, FaceTime) Share video so that both viewers (e.g., coach and teacher) are able to view video simultaneous on screen Allocate a specific amount of time on each teacher’s video clip(s), ensuring that equal amounts of time were spent on each teacher Moderate discussions around clips, soliciting feedback and additional teacher perspectives |

Record teachers’ implementation of a lesson/activity during observations OR ask teachers to record a lesson/activity that are aligned with teachers’ goals/priorities for improvement Share the recorded videos during the small group meeting Allocate a specific amount of time on each teacher’s video clip(s), ensure equal amounts of time spent on each teacher Moderate discussions around clips, soliciting feedback and alternate perspectives from all teachers |

See, Think, Do Framework for Reflective Conversations

In the sections below, we describe each component of the “See, Think, Do” framework in greater detail. Table 3 includes examples of coach prompts that can be used in each of the components. We also include general tips and recommendations for coaches who facilitate reflective conversations with teachers (Table 4).

Table 3.

Examples of coach prompts to guide the reflective conversation

| Six-step process | Coach prompts |

|---|---|

| Observe | “Let’s watch this clip of the recording you submitted…” |

| Describe |

“Let’s spend a few minutes reflecting.” “I would like for you to give me a play by play of what happened: Who was there? What they were doing? What was said? “I just want to get a clear picture of what was really going on.” |

| Process |

“Talk about what you were feeling before you started the lesson.” Follow-up questions: How did you think the student would answer? How did you feel when the student answered incorrectly? How do you feel now? |

| Analyze |

“Tell me about the things that worked out (and/or did not work out) the way you planned.” “Why do you think [X] happened the way it did?” “What did you notice about [student name] during the activity?” “Why do you think [student name] responded that way during the activity?” |

| Draw conclusions |

“What is your takeaway from this reflection?” “What did you learn worked well from this experience?” |

| Plan |

“What are specific action steps you will take based on what we discussed today?” “Are there any professional development opportunities that would help you around this area?” “What type of support can I provide?” |

Table 4.

General tips for reflective conversations with teachers

|

1. Listen and use wait time and give teachers a few minutes to process information and reflect 2. Use open-ended questions to encourage teachers to share their thoughts and perspectives 3. Clarifying questions can gently elicit more information from teachers 4. Validate teachers’ responses and feelings at each step |

See

Observe

The coach and teacher silently watch a selected clip together. The coach and teacher take notes while watching the clip, but refrain from discussion. At this step, it is often helpful for the coach to remind the teacher that they will be simply watching the clip without any commentary.

Describe

After the coach and teacher watch the recorded clip, the coach guides the teacher to describe what happened. The coach prompts the teacher for a detailed, fact-based play-by-play of the clip. This step is important because (1) it helps the coach understand which aspects of the instructional practice the teacher attends to and (2) it creates a shared understanding between the coach and teacher about what unfolded during the video clip.

The teacher has an opportunity to take on an observer’s perspective. The coach asks the teacher to describe what happened during the interaction, void of any judgement or assumption, problem solving, or conclusions. At this stage, the teacher may be tempted to insert reactions (e.g., “I can’t believe I didn’t notice that…”) or explanations (e.g., “I did this because…”), but it is important to encourage the teacher to provide a narration of what they observed during the clip (e.g., “Remember, we are just describing what you noticed in the clip”).

After the teacher has described what happened, the coach may need to provide additional prompts to fill in any gaps in the narration. This process is important because it allows the teacher to see what happened versus what they thought happened.

Think

Process

Next, the coach helps the teacher process what they have observed and described. The coach encourages the teacher to recall and explore what the teacher was thinking and feeling during the activity or interaction in the recorded clip. A coach can direct the teacher to a specific moment to encourage the teacher to become aware of their feelings or reactions when watching the clip.

Analyze

After processing, the coach guides the teacher to analyze the interaction. Analysis involves hypothesizing and/or inferring reasons for the interaction (e.g., “Why do you think the student struggled with this activity?”). The coach helps the teacher consider students’ perspectives. Considering students’ perspectives allows the teacher to situate their teaching practices in the context of student learning. The coach can use verbal cues to scaffold the teacher’s thinking if a teacher struggles to analyze the interaction. For example, the coach can ask the teacher about specific students or materials in the lesson (e.g., “What kind of book did you read?”) and then guide teachers to reflect on student responses (e.g., “How did students respond to the book?”; “Why do you think students responded that way?”).

Do

Draw Conclusions

Then, the coach supports the teacher in drawing conclusions about the activity or interaction. The coach helps the teacher to articulate what aspects of instruction they would modify or keep the same. It can be tempting for the coach to jump immediately to this part of the process. However, the previous four steps help to set the stage for the teacher to thoughtfully draw conclusions with minimal coach support. If teachers are not able to draw conclusions independently, coaches can ask teachers specific, open-ended, guiding questions that help teachers brainstorm key takeaways from the reflective conversation (Hudson & Pletcher, 2020). Coaches can refer to their notes to remind and cue teachers about specific interactions that were discussed during the reflective conversation. This step begins the process of helping teachers to shift their thinking from the “so what” to the “now what.”

Plan

Finally, the coach helps the teacher plan for future lesson. At this point, the teacher is ready to consider next steps and can make an action plan for the next activity. The coach prompts the teacher to articulate specific action steps, which are then noted on the action plan. The action plan helps the teacher to map out suggestions (e.g., lesson adaptations) for the next activity. The action plan can include professional development opportunities (e.g., workshops, video resources) that align with the teacher’s reflections. The reflective conversation concludes with the coach repeating back to the teacher what the action steps are and asking the teacher about other ways the coach can support them.

Conclusion

Reflection can be a catalyst for changing teachers’ instructional practices. Teachers who are able to reflect on their practices are better positioned to problem solve (Shannon et al., 2020). The six-step framework that uses video recordings of teacher practice can be a powerful way to help teachers gain insights about their own practices and actively participate in the reflection process. In Fig. 3, we show how the case study presented in the introduction maps onto the “See, Think, Do” framework. The annotation shows how the coach guides the teacher (Patricia) through each of the steps within the framework. Although the coach-teacher conversation is not lengthy, the annotation shows how seamless it can be to leverage this framework even in shorter coach-teacher conversations. When teachers have opportunities to observe and reflect on their own practices, they are more likely to internalize and adopt new ways of thinking.

Fig. 3.

Annotated case study

In early childhood settings, the use of video reflection can be an especially powerful tool as it can provide teachers with a more holistic perspective of their interactions and classroom environments—perspectives that may otherwise be missed due to various classroom demands. When teachers are able to observe their interactions and practices in their authentic classroom contexts, they are also better positioned to identify which practices seem to be effective for students and which practices may require improvement or modification. Coaches play an important role in both supporting and facilitating these opportunities so that teachers can improve their practices. Moreover, the video reflection process helps coaches to understand teachers’ learning and professional growth, as they can more clearly understand (and respond to) the areas teachers focus on during their reflective conversations and identify additional supports for the teacher.

Funding

Funding was provided by Institute of Education Sciences (Grant No. R305A140378).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Artman-Meeker KM, Hemmeter ML. Effects of training and feedback on teachers’ use of classroom preventive practices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2013;33:112–123. doi: 10.1177/0271121412447115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borko, H., Jacobs, J., Eiteljorg, E., & Pittman, M. E. (2008). Video as a tool for fostering productive discussions in mathematics professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(2), 417–436.

- Coburn CE, Woulfin SL. Reading coaches and the relationship between policy and practice. Reading Research Quarterly. 2012;47(1):5–30. doi: 10.1002/RRQ.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A, Varghese C, Hsu H, Zucker T, Landry S, Assel M, Monsegue-Bailey P, Bhavsar V. A comparative analysis of instructional coaching approaches: Remote versus face-to-face coaching in preschool classrooms. Journal of Education Psychology. 2021;113:1609–1627. doi: 10.1037/edu0000691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A, Varghese C, Oh Y, Guttentag C, Zucker T, Landry S, Cummins R, Johnson U, Montroy J. The effects of the CLI Engage Toddler Program on child care teachers and toddlers. Early Education & Development. 2021 doi: 10.1080/10409289.2021.1961427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A, Varghese C, Monsegue-Bailey P. The implementation and scaling of an early education program. Journal of Applied Research on Children. 2020;11:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone LM. Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher. 2009;38(3):181–199. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08331140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ. Improving the design and implementation of in-service professional development in early childhood intervention. Infants & Young Children. 2015;28(3):210–219. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0000000000000042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LK, Cobb P. Focusing on teacher learning opportunities to identify potentially productive coaching activities. Journal of Teacher Education. 2017;68(4):411–425. doi: 10.1177/0022487117702579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A., Ruzek, E., Hafen, C. A., Mikami, A. Y., Allen, J. P., & Pianta, R. C. (2017). My Teaching Partner-Secondary: A video-based coaching model. Theory into Practice, 56(1), 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Jamil, F. M., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Enhancing teachers’ intentional use of effective interactions with children: Designing and testing professional development interventions. Handbook of Early Childhood Education, 507–532.

- Heineke SF. Coaching discourse: Supporting teachers' professional learning. The Elementary School Journal. 2013;113:409–433. doi: 10.1086/668767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AK, Pletcher BC. The art of asking questions: Unlocking the power of a coach’s language. The Reading Teacher. 2020;74:96–100. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inbar-Furst, H., Douglas, S. N., & Meadan, H. (2020). Promoting caregiver coaching practices within early intervention: Reflection and feedback. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(1), 21–27.

- Kane, B. D., & Rosenquist, B. (2019). Relationships between instructional coaches’ time use and district-and school-level policies and expectations. American Educational Research Journal, 0002831219826580.

- Knight DS. Are school districts allocating resources equitably? The Every Student Succeeds Act, teacher experience gaps, and equitable resource allocation. Educational Policy. 2019;33(4):615–649. doi: 10.1177/0895904817719523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Anthony JL, Swank PR, Monseque-Bailey P. Effectiveness of comprehensive professional development for teachers of at-risk preschoolers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;101:448–465. doi: 10.1037/a0013842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Swank PR, Anthony JL, Assel MA. An experimental study evaluating professional development activities within a state funded pre-kindergarten program. Reading and Writing. 2011;24:971–1010. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9243-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Zucker TA, Taylor HB, Swank PR, Williams JM, Assel M, Phillips BM. Enhancing early child care quality and learning for toddlers at risk: The responsive early childhood program. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:526–541. doi: 10.1037/a0033494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons, C. J., & Toste, J. R. (2019). Professional development and coaching: Addressing the “Last Mile” problem in educational research. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 1534508419862859.

- Loughran JJ. Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education. 2002;53:33–43. doi: 10.1177/0022487102053001004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. G. (2008). Mathematics teachers’ “learning to notice” in the context of a video club. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 244–276.

- Marsh, B., & Mitchell, N. (2014). The role of video in teacher professional development. Teacher Development, 18(3), 403–417.

- Matsumura, L. C., Correnti, R., Walsh, M., Bickel, D. D., & Zook-Howell, D. (2019). Online content-focused coaching to improve classroom discussion quality. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 28(2), 191–215.

- Peterson DS, Taylor BM, Burnham B, Schock R. Reflective coaching conversations: A missing piece. The Reading Teacher. 2009;62:500–509. doi: 10.1598/RT.62.6.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta R, Hamre B, Downer J, Burchinal M, Williford A, Locasale-Crouch J, Scott-Little C. Early childhood professional development: Coaching and coursework effects on indicators of children’s school readiness. Early Education and Development. 2017;28(8):956–975. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2017.1319783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Mashburn AJ, Downer JT, Hamre BK, Justice L. Effects of web-mediated professional development resources on teacher–child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008;23:431–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers C. Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record. 2002;104:842–866. doi: 10.1177/016146810210400402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Woods J. Collaborative coaching with Early Head Start teachers using responsive communication strategies. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2018;38(1):30–41. doi: 10.1177/0271121417696276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. (2018). How to make education research relevant to teachers [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/director/remarks/11-14-2018.asp.

- Schwartz K, Cappella E, Aber JL, Scott MA, Wolf S, Behrman JR. Early childhood teachers’ lives in context: Implications for professional development in under-resourced areas. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2019;63:270–285. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, D. K., Snyder, P. A., Hemmeter, M. L., & McLean, M. (2020). Exploring coach–teacher interactions within a practice-based coaching partnership. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 1–12.

- Sherin, M. G. (2007). The development of teachers’ professional vision in video clubs. In R. Goldman, R. Pea, B. Barron, & S. Derry (Eds.), Video Research in the Learning Sciences (pp. 383–395) Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Sherin, M. G, & Van Es, E. A. (2009). Effects of video club participation on teachers' professional vision. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 20–37.

- Snyder PA, Hemmeter ML, Fox L. Supporting implementation of evidence-based practices through practice-based coaching. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2015;35(3):133–143. doi: 10.1177/0271121415594925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J., Rao, N., & Pearson, E. (2015). Policies and strategies to enhance the quality of early childhood educators. Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report.

- Walsh M, Matsumura LC, Zook-Howell D, Correnti R, Bickel DD. Video-based literacy coaching to develop teachers’ professional vision for dialogic classroom text discussions. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2020;89:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.103001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winton, P. J., Snyder, P., & Goffin, S. (2015). Beyond the status quo: Rethinking professional development for early childhood teachers. In L. Couse & S. Recchia (Eds.) Handbook of Early Childhood Teacher Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Yoon, K. S., Duncan, T., Lee, S. W. Y., Scarloss, B., & Shapley, K. L. (2007). Reviewing the evidence on how teacher professional development affects student achievement. Issues & Answers. REL2007-No. 033. Regional Educational Laboratory Southwest (NJ1).