Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate SOF-1 was resistant to cefepime and susceptible to ceftazidime. This resistance phenotype was explained by the expression of OXA-31, which shared 98% amino acid identity with a class D β-lactamase, OXA-1. The oxa-31 gene was located on a ca. 300-kb nonconjugative plasmid and on a class 1 integron. No additional efflux mechanism for cefepime was detected in P. aeruginosa SOF-1. Resistance to cefepime and susceptibility to ceftazidime in P. aeruginosa were conferred by OXA-1 as well.

The most frequent mechanisms of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa are derepression of the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase, impermeability of the outer membrane, and increased efflux (5). These various processes, independently or conjointly, confer resistance to ceftazidime. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) belonging to each of the Ambler β-lactamase classes are described in P. aeruginosa (20). Among the clavulanic acid-inhibited Ambler class A enzymes, TEM- and SHV-related ESBLs, PER-1 and VEB-1 hydrolyze ceftazidime and cefepime significantly (20). The Ambler class B enzymes, IMP-1, VIM-1, and VIM-2, have the broadest hydrolysis profiles, which include hydrolysis of ceftazidime and cefepime (20, 25). The last group of ESBLs includes OXA-18, the OXA-2 and OXA-10 derivatives (18, 20), and OXA-24 and ARI-1, with the last two also hydrolyzing carbapenems (3, 9). Among the OXA-10 variants, OXA-11, -14, and -19 predominantly compromise the activity of ceftazidime, while OXA-17 mainly degrades cefotaxime (8, 18). The OXA-10 variants confer resistance to cefepime usually at a lower level than they do to ceftazidime. A recent survey conducted with more than 2,000 isolates of P. aeruginosa showed that the rates of susceptibility to ceftazidime and cefepime are similar, being 78.8 to 81.9% and 80 to 83.4%, respectively (27).

The aim of the present work was to characterize the mechanism(s) involved in a peculiar antibiotic resistance phenotype that combines resistance to cefepime and susceptibility to ceftazidime.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

P. aeruginosa SOF-1 was isolated from a rectal swab specimen from a 1-month-old child hospitalized at the Hôpital de Bicêtre (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France) in 1999. This isolation was the result of systematic screening for multidrug-resistant gram-negative isolates from patients admitted to the intensive care units of this hospital. It was identified with the API 20 NE system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Ciprofloxacin- or rifampin-resistant P. aeruginosa PU21 obtained in vitro and rifampin-resistant Escherichia coli K-12 C600 obtained in vitro were used as recipient strains for conjugation, and E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116 (Institut Pasteur Collection, Paris, France) reference strains (23–25) were used for cloning experiments. E. coli NCTC 50192 carrying plasmids of 154, 66, 38, and 7 kb served as a control in a plasmid-sizing study (33). Plasmids pPCRScript-Cam (SK+; Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), which carries the chloramphenicol resistance marker, and the E. coli-P. aeruginosa shuttle vector pBBR1MCS, which confers resistance to tetracycline, were used for the cloning experiments (12).

Antimicrobial agents and MIC determinations.

Antibiotic disks (Sanofi-Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) were used for routine antibiograms. The antimicrobial agents were obtained from standard laboratory powders and were used immediately after their solubilization. The agents and their sources were as follows: amoxicillin, ceftazidime, clavulanic acid, and ticarcillin, Glaxo-Smith-Kline (Nanterre, France); amikacin, aztreonam, and cefepime, Bristol-Myers Squibb (Paris-La Défense, France); cephalothin and moxalactam, Eli Lilly (Saint-Cloud, France); piperacillin and tazobactam, Lederle (Oullins, France); sulbactam, Pfizer (Orsay, France); cefotaxime, cefuroxime, and cefpirome, Aventis (Paris, France); cefoxitin and imipenem, Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret (Paris, France); and rifampin and chloramphenicol, Sigma (Saint-Quentin Falavier, France).

MICs were determined by an agar dilution technique on Mueller-Hinton agar plates with a Steers multiple inoculator and an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot (23). Results of susceptibility testing were recorded according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (19) after incubation at 37°C for 18 h.

Plasmid DNA analysis.

Plasmid DNAs from P. aeruginosa SOF-1 were extracted by two different methods as described previously (23, 25) and with the Qiagen plasmid DNA maxi kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Plasmid DNAs were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.7% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml for 16 h at 90 V (28) and compared to standard sizes of plasmid DNAs of E. coli NCTC 50192. The gel was transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) by the Southern technique (28). The DNAs were then UV cross-linked (Stratalinker; Stratagene) for 30 s. The probe, made of a PCR-generated, 611-bp internal fragment of blaOXA-31 (see Results section), was labeled with the an ECL nonradioactive labeling and detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), based on a combination of enhanced chemiluminescence detection and random primer labeling of DNA.

Direct transfer of the ticarcillin and cefepime resistance markers into rifampin-resistant E. coli K-12 C600 or rifampin- or ciprofloxacin-resistant P. aeruginosa PU21 was attempted by liquid and solid mating-out assays at 37°C (25). The antibiotic concentrations for transconjugant selection on Trypticase soy (TS) agar plates (Sanofi-Diagnostics Pasteur) were 50, 20, 200, and 10 μg/ml for ticarcillin, cefepime, rifampin, and ciprofloxacin, respectively.

Recombinant plasmids were transferred by electroporation into the E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116 reference strains.

Cloning experiments and analysis of recombinant plasmids.

Whole-cell DNA of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 was extracted as described previously (23). Since most of the oxacillinase genes are located on a class 1 integron (10, 18), PCR amplification experiments were attempted with primers located in 5′-CS and 3′-CS regions (each end of class 1 integrons) (24) and whole-cell DNA of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 as a template. The fragment of 3.5 kb obtained by PCR was cloned into the SrfI site of pPCRScript Cam (SK+) as described previously (25), and the resulting recombinant plasmid pDAN-1 was selected in E. coli DH10B on Mueller-Hinton agar plates containing amoxicillin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). Then, the oxa-31 gene was subcloned by insertion of a SpeI-PstI fragment of pDAN-1 into the SpeI-PstI restricted shuttle vector pBBR1MCS, giving pDAN-2. The oxa-1 gene was amplified by PCR (with primer OXA1A [5′-AGCCGTTAAAATTAAGCCC-3′] and primer OXA1B [5′-CTTGATTGAAGGGTTGGGC G-3′) with blaOXA-1-containing plasmid RGN238 from Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium as a template (gift from R. Labia) (21). The 911-bp fragment encompassing the oxa-1 gene obtained by PCR was cloned into plasmid pBBR1MCS, giving recombinant plasmid pDAN-3.

DNA sequencing and protein analysis.

Both strands of the cloned DNA fragments from recombinant plasmids pDAN-1 and pDNA-3 were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems sequencer (model ABI 373). The nucleotide and the deduced protein sequences were analyzed with software available over the Internet at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Biochemical analysis.

Cultures of E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116 harboring recombinant plasmids pDAN-2 and pDAN-3 and cultures of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 were grown overnight at 37°C in 500 ml of TS broth containing ticarcillin (50 μg/ml), and β-lactamase extracts were obtained as described previously (24). The β-lactamase extracts were suspended in 20 ml of Tris–100 mM H2SO4–300 mM K2SO4 buffer (pH 7.0). The protein content was measured by the Bio-Rad DC Protein assay, and the specific activities of the β-lactamase extracts (except for those from the P. aeruginosa SOF-1 culture) were compared as described previously (24).

The β-lactamase extracts from cultures of E. coli DH10B(pDAN-2 and pDAN-3) were further purified by a two-step ultrafiltration as recommended by the manufacturer (Vivapsin, 20 ml; 100,000 MWCOPES and 10,000 MWCOPES; Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). Purified β-lactamase extracts were used for kinetic measurements performed at 30°C in Tris-100 mM H2SO4–300 mM K2SO4 buffer (pH 7.0). The initial rates of hydrolysis were determined with an ULTROSPEC 2000 UV spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as described previously (24).

Enzyme preparations from cultures of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 and the semipurified β-lactamases from E. coli DH10B cultures harboring pDAN-2 and pDAN-3 were also subjected to analytical isoelectric focusing (IEF) analysis as described previously (24).

Measurement of norfloxacin and cefepime accumulation.

The technique used for the efflux study has been described previously (16, 30). Briefly, exponential-phase P. aeruginosa SOF-1 cells in Luria-Bertani broth (bioMérieux) were removed by centrifugation and washed once in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The pellets were suspended in the same buffer at a density of 2 × 1010 CFU per ml. Assays were initiated by adding 14C-norfloxacin (Merck Sharp & Dohme, Rahway, N.J.) or 14C-cefepime (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Syracuse, N.Y.) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml each (1,010 cpm per ml). Samples (100 μl each) were removed at set intervals and were immediately filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size Whatman GF/C filters presoaked in phosphate buffer and then washed twice with 5 ml of cold phosphate buffer. The filters were dried at 80°C, and the radioactivity was measured in a Beckman scintillation spectrophotometer. The same experiments were also performed after a 10-min preincubation with the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the oxa-31 gene and its class 1 integron has been assigned EMBL database accession number AF294653.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Susceptibility testing, plasmid DNA analysis of P. aeruginosa SOF-1, and IEF analysis.

P. aeruginosa SOF-1 was resistant to cefepime and cefpirome and was susceptible to ceftazidime, imipenem, and aztreonam (Table 1). Addition of clavulanic acid and tazobactam did not significantly decrease the MICs of piperacillin and ticarcillin (Table 1), thus indicating that a Bush group 2b or 2be β-lactamase was not involved (4). Antibiotic susceptibility testing by disk diffusion showed that P. aeruginosa SOF-1 was also resistant to amikacin, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, kanamycin, norfloxacin, and tobramycin (data not shown). The low MIC of ceftazidime was consistent with a weak expression of the naturally occurring AmpC-type enzyme (5).

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactams for P. aeruginosa SOF-1 clinical isolate, P. aeruginosa 104116 harboring recombinant plasmids pDAN-2 and pDAN-3, reference strain P. aeruginosa 104116, E. coli DH10B harboring recombinant plasmids pDAN-1, pDAN-2, pDAN-3, and reference strain E. coli DH10B

| β-Lactamb | MIC (μg/ml) fora:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa SOF-1 | P. aeruginosa 104116(pDAN-2) | P. aeruginosa 104116(pDAN-3) | P. aeruginosa 104116 | E. coli DH10B(pDAN-1) | E. coli DH10B(pDAN-2) | E. coli DH10B(pDAN-3) | E. coli DH10B | |

| Amoxicillin | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin | 512 | >512 | >512 | 16 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin + CLA | >512 | >512 | >512 | 16 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 128 | 256 | 256 | 8 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 4 |

| Piperacillin + TZB | 256 | 512 | 256 | 8 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 2 |

| Cephalothin | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| Cefsulodin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Cefuroxime | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Ceftazidime | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ceftazidime + CLA | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Cefotaxime | 64 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | <0.06 |

| Cefepime | 128 | 256 | 256 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | <0.06 |

| Cefpirome | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.12 |

| Moxalactam | 32 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Aztreonam | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Imipenem | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

The P. aeruginosa SOF-1 clinical isolate and recombinant plasmids pDAN-1 and pDAN-2 expressed OXA-31, while pDAN-3 expressed OXA-1.

CLA, clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml; TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Extraction of plasmid DNA from P. aeruginosa SOF-1 gave a ca. 300-kb plasmid that was not transferred by conjugation to ciprofloxacin- and rifampin-resistant P. aeruginosa PU21 or to rifampin-resistant E. coli K-12. It hybridized with an internal probe for the oxa-31 gene prepared by PCR, thus showing the plasmid location of this gene (data not shown).

A β-lactamase extract of a culture of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 was submitted to IEF analysis and gave two β-lactamases with pI values of 7.5 and 8.5, with the latter likely corresponding to an AmpC-type enzyme (data not shown) (34). A β-lactamase extract of E. coli DH10B(pDAN-1) gave a pI value of 7.5, as found for P. aeruginosa SOF-1 (data not shown).

Cloning, sequencing of the β-lactamase gene, and analysis of the surrounding sequences.

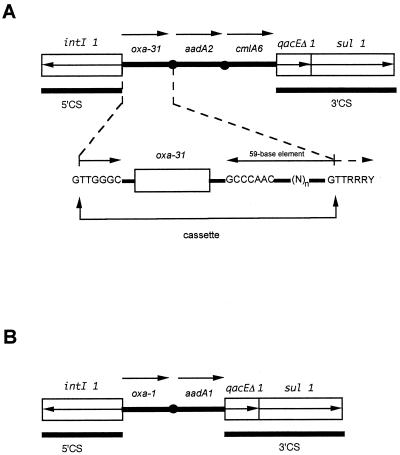

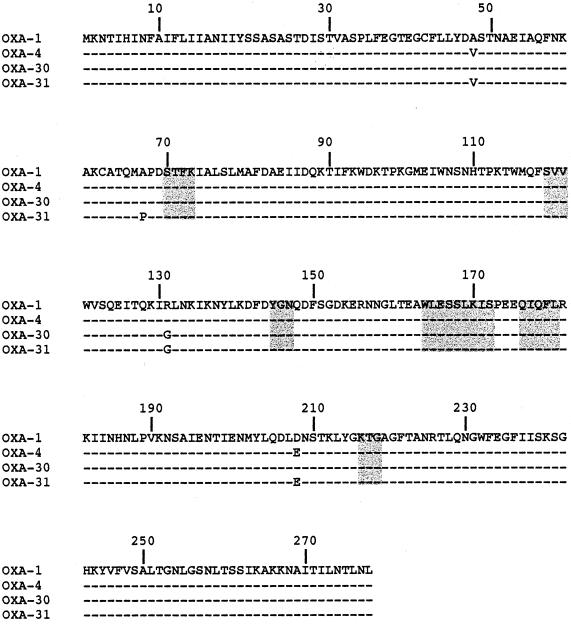

The cloned fragment of plasmid pDAN-1 encoded three open reading frames (ORFs) located downstream of a class 1 integrase gene (Fig. 1). The first ORF was 828 bp and encoded a 276-amino-acid preprotein, named OXA-31. Within the deduced protein of this ORF, a serine-threonine-phenylalanine-lysine tetrad (S-T-F-K) was found at positions 70 to 73 according to the class D β-lactamase numbering (DBL) (Fig. 2); it was included in the conserved serine and lysine amino acid residues characteristic of β-lactamases that possess a serine active site or penicillin-binding proteins (11).

FIG. 1.

Structure of the class 1 integrons that contain oxa-31 (A) and oxa-1 (B) cassettes. The arrows indicate the transcriptional orientations of the ORFs.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of β-lactamase OXA-31 to those of OXA-1, OXA-4, and OXA-30. Dashes indicate identical amino acids. The numbering is according to DBL (13). The highlighted boxes indicate conserved regions within class D β-lactamases.

Five elements characteristic of class D β-lactamases were found: S-X-V at positions DBL 118 to 120, Y/F-G-X at positions DBL 144 to 146, W-L/I-X-X-X-L-X-I/V at positions DBL 164 to 172, Q-X-X-X-L at positions 176 to 180, and lysine-threonine-arginine (K-T-G) at positions 216 to 218 (Fig. 2) (18). The comparison of the blaOXA-31 nucleotide sequence to those of blaOXA-1 and blaOXA-30 identified the following nucleotide substitutions: at position 146, T to C for blaOXA-1 and blaOXA-30; at position 202, C to G for blaOXA-1 and blaOXA-30; at position 391, G to A for blaOXA-1 and no change for blaOXA-30; and at position 621, G to T for blaOXA-1 and blaOXA-30 (21, 31). Compared to OXA-1 and its derivatives OXA-4 and OXA-30, OXA-31 possessed four, two, and three amino acid changes, respectively (Fig. 2) (21, 29, 31). None of the amino acid changes that occurred in the OXA-31 sequence when it was compared to the sequences of OXA-1 from S. enterica serotype Tyhimurium, OXA-4 from P. aeruginosa, and OXA-30 from Shigella flexneri were located at positions characteristic of class D enzymes (Fig. 2).

Analysis of the surrounding DNA sequences of blaOXA-31 revealed an ORF located downstream (Fig. 1). It encoded an aminoacyl adenyl transferase (AADA2a) that shared 99% amino acid identity with AADA2 that has been associated with blaPSE-1 from S. enterica serotype Typhimurium (2, 24). This protein conferred resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin in E. coli DH10B (data not shown). An additional ORF located downstream corresponded to a cmlA-like gene that encodes CMLA6 for chloramphenicol resistance and that shared 99% amino acid identity with CMLA1, with only three amino acid changes (data not shown) (1).

A structure of a class 1 integron was found surrounding the oxa-31 cassette. The structure consisted of (i) a 5′-CS containing a class 1 integrase gene with its own promoter, Pint, (ii) an att11 recombination site, and (iii) a 3′-CS containing qacEΔ1 (Fig. 1). The oxa-31 gene cassette had a core site (5′-GTTGGGC-3′), an inverse core site (5′-GCCCAAC-3′), and a 59-base element made up of 108 bp of the sequence downstream of this gene that was identical to that found in the oxa-1 cassette (21). The 182 N-terminal amino acids of the integrase identified from the sequenced part of the corresponding ORF were identical to those found in several class 1 integrons (6, 32). Compared to the corresponding promoter region for blaOXA-1, the P1 promoter sequence of blaOXA-31 differed by one substitution in the −10 sequence, and the P2 promoter sequence of the blaOXA-31 integron was probably not functional due to a shorter spacing (14 bp instead of 17 bp). This promoter pair was identical to the hybrid promoter sequences found in the blaOXA-2-containing integron (7, 14, 21).

Comparison of OXA-31 and OXA-1 activities.

The MIC of cefepime for E. coli DH10B(pDAN-1) increased slightly compared to that for E. coli DH10B, while the MICs of ceftazidime remained unchanged and the MICs of cefotaxime were only weakly increased (Table 1). To show that OXA-31 confers resistance to cefepime and susceptibility to ceftazidime, a series of experiments was performed. Recombinant plasmid pDAN-2 that contained a blaOXA-31-containing DNA fragment from pDAN-1 was transferred by electroporation into reference strains E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116. The MICs of cefepime, cefpirome, and ticarcillin were significantly increased for P. aeruginosa 104116(pDAN-2) compared to those for P. aeruginosa 104116, while the MICs of ceftazidime and cefotaxime remained unchanged or were slightly increased, respectively (Table 1). This experiment clearly established the role of OXA-31 in the acquisition of resistance to cefepime in P. aeruginosa.

Recombinant plasmid pDAN-3, which had a blaOXA-1-containing DNA fragment, was transferred by electroporation into reference strains E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116. The MICs of β-lactams for E. coli DH10B harboring pDAN-3 (OXA-1) and pDAN-2 (OXA-31) on the one hand and for P. aeruginosa 104116 harboring pDAN-2 and pDAN-3 on the other were identical (Table 1). The specific activities of β-lactamase extracts for several β-lactams were determined with extracts from E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116 cultures expressing either OXA-31 or OXA-1 (Table 2). The values obtained were almost identical, showing that OXA-1 and OXA-31 had similar hydrolysis spectra for cefepime and cefpirome on the one hand and for ceftazidime and cefotaxime on the other, although for the last two drugs hydrolysis was weak or undetectable (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Specific activities of OXA-31 and OXA-1 from E. coli DH10B and P. aeruginosa 104116

| Substrate (100 μM) | Sp act (mU/mg)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli DH10B

|

P. aeruginosa 104116

|

|||

| OXA-31b | OXA-1c | OXA-31 | OXA-1 | |

| Amoxicillin | 330 | 310 | —d | — |

| Aztreonam | NHe | NH | NH | NH |

| Cefepime | 56 | 54 | 655 | 655 |

| Cefotaxime | 14 | 12 | 160 | 170 |

| Cefpirome | 130 | 115 | 1,120 | 1,190 |

| Ceftazidime | NH | NH | NH | NH |

| Cephalothin | 5 | 6 | — | — |

| Cloxacillin | 245 | 202 | 2,720 | 2,970 |

Standard deviations were within 10%.

OXA-31 was expressed from recombinant plasmid pDAN-2.

OXA-1 was expressed from recombinant plasmid pDAN-3.

—, not done due to interference with the naturally occurring AmpC-type cephalosporinase.

NH, no detectable hydrolysis.

The specific activities obtained from P. aeruginosa cultures were much higher compared to those obtained from E. coli cultures, whatever substrate was used, except for ceftazidime and aztreonam. Increases ranged from 10- to 15-fold according to the substrate, probably as a result of a higher rate of plasmid replication in P. aeruginosa cultures or better β-lactamase folding. The results for the cefepime and cefpirome specific activities correlated to the MICs, with a marked increase in the level of resistance in P. aeruginosa (Tables 1 and 2).

The hydrolysis parameters for OXA-1 and OXA-31 showed that they are typical oxacillinases (Table 3). Kinetic parameters showed that the catalytic activities of OXA-1 and OXA-31 were similar and were significant toward cefepime (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of kinetic parameters of several β-lactams for OXA-31 and OXA-1

| β-Lactam | OXA-31

|

OXA-1

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmaxa | Km (μM) | Vmax/Km | Vmax | Km (μM) | Vmax/Km | |

| Benzylpenicillin | 100 | 5 | 100 | 100 | 5 | 100 |

| Amoxicillin | 350 | 60 | 30 | 360 | 53 | 30 |

| Cefepime | 1,790 | 200 | 45 | 1,630 | 215 | 40 |

| Cefpirome | 1,810 | 120 | 75 | 1,410 | 110 | 65 |

| Cephalothin | 80 | 45 | 10 | 100 | 40 | 10 |

| Cefotaxime | 75 | 35 | 10 | 110 | 35 | 20 |

| Cloxacillin | 400 | 2 | 1,000 | 360 | 2 | 900 |

The Vmax values are relative to that of benzylpenicillin, which was set at 100. Standard deviations were within 10%.

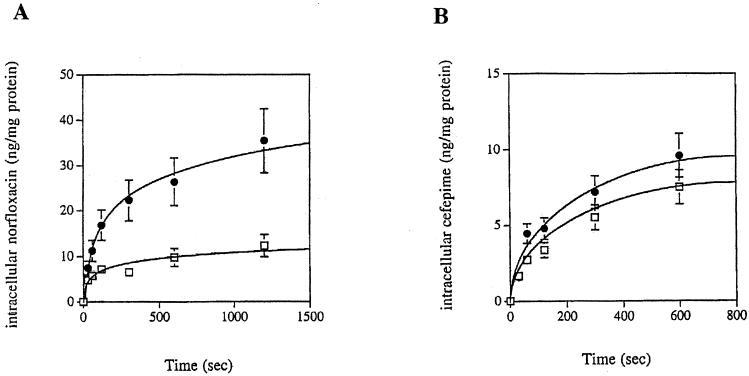

Efflux study.

The efflux of cefepime has been reported in P. aeruginosa as a resistance mechanism that may be specific to cefepime and cefpirome (26). Thus, the efflux of cefepime was examined as an additional mechanism of resistance to cefepime in P. aeruginosa SOF-1. The levels of norfloxacin and cefepime that accumulated at steady state were compared in the absence or in the presence of the uncoupler CCCP since intracellular uptake is energy independent and efflux is energy dependent. The steady-state level of intracellular norfloxacin increased by about threefold in the presence of CCCP, thus indicating the presence of an efflux mechanism for this drug that paralleled the resistance to norfloxacin observed in P. aeruginosa SOF-1 (Fig. 3A). By contrast, the addition of CCCP did not change the intracellular concentration of cefepime significantly, thus ruling out efflux of this drug in P. aeruginosa SOF-1 (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Intracellular accumulation of cefepime and norfloxacin in P. aeruginosa clinical isolate SOF-1. The intracellular concentrations of radiolabeled norfloxacin (A) and cefepime (B) were measured in cells of P. aeruginosa SOF-1 with (●) or without (□) the energy uncoupler CCCP. Values are means of two independent experiments.

Conclusion.

We showed that OXA-31 confers resistance to cefepime and susceptibility to ceftazidime in P. aeruginosa SOF-1, a property not reported previously (13). This property is shared by OXA-1 as well and is very likely shared by other OXA-1 derivatives such as OXA-4 (17). Indeed, β-lactamase OXA-4, originally described in P. aeruginosa (15, 22) and reported recently from several P. aeruginosa isolates in Japan, confers resistance to the oxyimino cephalosporin cefclidin and susceptibility to ceftazidime (17). Thus, OXA-1 and its derivatives may selectively hydrolyze some 2-amino-5-thiazolyl cephalosporins (cefpirome, cefepime, and cefclidin) and not others (ceftazidime, cefotaxime), with these drugs mostly differing by substitutions at the C-3 of the cephem core. Finally, this study showed that in a routine laboratory ceftazidime resistance should not be reported on the sole basis of cefepime resistance for P. aeruginosa-producing OXA-1 derivatives, as opposed to those that produce class A ESBLs. This result has clinical implications for the choice of the most appropriate treatment for nosocomial infections due to P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by a grant from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche (UPRES, grant JE-2227), Université Paris XI, Paris, France; INSERM (grant CJF 96-06), Marseilles, France; and a grant-in-aid from Glaxo-Smith-Kline (from F. Leblanc), Paris, France.

We thank M. Malléa for help with the efflux experiments and A. Ladzunski for gift of plasmid pBBR1MCS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bissonnette L, Champetier S, Buisson J P, Roy P H. Characterization of the nonenzymatic chloramphenicol resistance (cmlA) gene of the In4 integron of Tn1696: similarity of the product to transmembrane transport proteins. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4493–4502. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4493-4502.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bito A, Susani M. Revised analysis of aadA2 gene of plasmid pSa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1172–1175. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bou G, Oliver A, Martinez-Beltran J. OXA-24, a novel class D beta-lactamase with carbapenemase activity in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1556–1561. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1556-1561.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H Y, Yuan M, Livermore D M. Mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics amongst Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in the UK in 1993. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:300–309. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-4-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collis C M, Hall R M. Expression of antibiotic resistance gene in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:155–162. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale J W, Godwin D, Mossakowska D, Stephenson P, Wall S. Sequence of the OXA2 beta-lactamase: comparison with other penicillin-reactive enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1985;191:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danel F, Hall L M C, Duke B, Gur̈ D, Livermore D M. OXA-17, a further extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 β-lactamase isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1362–1366. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald H M, Scaife W, Amyes S G, Young H-K. Sequence analysis of ARI-1, a novel OXA β-lactamase responsible for imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:196–199. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.196-199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fluit A C, Schmitz F J. Class 1 integrons, gene cassettes, mobility, and epidemiology. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:761–770. doi: 10.1007/s100960050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonze E, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Kelly J A, Ghuysen J M, Frère J-M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledent P, Raquet X, Joris B, Van Beeumen J, Frère J-M. A comparative study of class-D β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1993;292:555–562. doi: 10.1042/bj2920555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lévesque C, Brassard S, Lapointe J, Roy P H. Diversity and relative strength of tandem promoters for the antibiotic-resistance genes of several integrons. Gene. 1994;142:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lévesque R C, Medeiros A A, Jacoby G A. Molecular cloning and DNA homology of plasmid-mediated β-lactamase genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;206:252–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00333581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malléa M, Chevalier J, Bornet C, Eyraud A, Davin-Regli A, Bollet C, Pagès J-M. Porin alteration and active efflux: two in vivo drug resistance strategies used by Enterobacter aerogenes. Microbiology. 1998;144:3003–3009. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marumo K, Takeda A, Nakamura Y, Nakaya K. Detection of OXA-4 β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates by genetic methods. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:187–193. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naas T, Nordmann P. OXA-type β-lactamases. Curr Pharm Design. 1999;5:865–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordmann P, Guibert M. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa J. Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:128–131. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouellette M, Bissonnette L, Roy P H. Precise insertion of antibiotic resistance determinants into Tn21-like transposons: nucleotide sequence of the OXA-1 β-lactamase genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7378–7382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philippon A M, Paul G C, Jacoby G A. New plasmid-mediated oxacillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986;17:415–422. doi: 10.1093/jac/17.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philippon L N, Naas T, Bouthors A-T, Barakett V, Nordmann P. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2188–2195. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poirel L, Guibert M, Bellais S, Naas T, Nordmann P. Integron- and carbenicillinase-mediated reduced susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in isolates of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 from French patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1098–1104. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poirel L, Naas T, Nicolas D, Collet L, Bellais S, Cavallo J-D, Nordmann P. Characterization of VIM-2, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing metallo-β-lactamase and its plasmid- and integron-borne gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:891–897. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.4.891-897.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poole K, Gotoh N, Tsujimot H, Zhao Q, Wada A, Yamasaki T, Neshat S, Yamagishi J, Li X Z, Nishino T. Overexpression of the mexC-mexD-oprJ efflux operon in nfxB-type multidrug resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:713–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.281397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramphal R, Hoban D J, Pfaller M A, Jones R J. Comparison of two broad-spectrum cephalosporins tested against 2,299 strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated at 38 North American medical centers participating in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 1997–1998. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;36:125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(99)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanschagrin F, Couture F, Lévesque R C. Primary structure of OXA-3 and phylogeny of oxacillin-hydrolyzing class D beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:887–893. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simonet V, Malléa M, Pagès J-M. Substitutions in the eyelet region disrupt cefepime diffusion through the Escherichia coli OmpF channel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:311–315. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.311-315.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siu L K, Lo J Y, Yuen K Y, Chau P Y, Ng M H, Ho P L. β-Lactamases in Shigella flexneri isolates from Hong Kong and Shangai and a novel OXA-1-like β-lactamase, OXA-30. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2034–2038. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2034-2038.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stokes H W, O'Gorman D B, Recchia G D, Parsekhian M, Hall R M. Structure and function of 59-base element recombination sites associated with mobile gene cassettes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:731–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6091980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vivian A. Plasmid expansion? Microbiology. 1994;140:213–214. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-213-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walther-Rasmussen J, Johnsen A H, Hoiby N. Terminal truncations in AmpC β-lactamase from a clinical isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur J Biochem. 1998;363:478–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]