Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic affects different people unequally, and migrants are frequently among the groups considered particularly vulnerable. However, conceptualizations of ‘vulnerability’ are often ambiguous and poorly defined. Using critical discourse analysis methods, this article analyses the academic use of the term ‘vulnerable’ applied to migrants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic across public health and social science disciplines.

Our findings indicate that the concept of vulnerability is frequently applied to migrants in the COVID-19 context as a descriptor with seemingly taken-for-granted applicability. Migrants are considered vulnerable for a wide variety of reasons, most commonly relating to exposure to and risk of contracting COVID-19; poverty or low socio-economic status; precarity; access to healthcare; discrimination; and language barriers. Drivers of migrants' vulnerability were frequently construed as immutable societal characteristics. Additionally, our analysis revealed widespread generalization in the use of the notion of vulnerability, with limited consideration of the heterogeneity among and between diverse groups of migrants. Conceptualizations of migrants' vulnerability in the COVID-19 pandemic were sometimes used to advance seemingly contradictory policy implications or conclusions, and migrants’ own views and lived experiences were often marginalized or excluded within these discourses.

Our analysis highlights that although some definable groups of people are certainly more likely to suffer harm in crisis situations like the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of ‘vulnerable’ as a fixed descriptor has potentially negative implications. As an alternative, we suggest thinking about vulnerability as the dynamic outcome of a process of ‘vulnerabilisation’ shaped by social order and power relations.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vulnerability, Migrants, Critical discourse analysis, Power

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted everybody's lives in different ways. Some groups are disproportionately exposed to negative consequences of the pandemic, as COVID-19 has mercilessly exposed and reinforced pre-existing social fault lines in societies (Kawachi, 2020). Despite their global nature, pandemics typically manifest locally in myriads of ways, giving rise to differential outcomes (Garoon & Duggan, 2008). The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is socially patterned not just in terms of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, but also in terms of the consequences of the implemented restrictions and emergency lockdown measures (Bambra et al., 2020).

In light of the pandemic's unequally distributed impact and indirect consequences, a wide range of groups have been referred to as ‘vulnerable’ in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. For example, both in academic literature and popular media, people with comorbidities, the elderly, some groups of children, people of lower socioeconomic status, and migrants and refugees are frequently among the groups or populations labelled as vulnerable (Jones & Tvedten, 2019; Orcutt et al., 2020; Phillips, 2021; The Lancet, 2020). In many cases, identification of specific groups as vulnerable seems to be considered a prerequisite for ensuring that principles of health equity and social justice are incorporated in pandemic responses. Indeed, the concept of vulnerability is often used in the context of calls to ‘protect the most vulnerable’ in the COVID-19 pandemic (UN Global Compact, 2020) – to tailor responses to groups or populations in need of special attention and assistance.

Already prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, migrants and their descendants were frequently among the groups framed as particularly vulnerable. In the literature on health and social inequalities, migrants' opportunities to live healthy lives and be part of immigrant societies are considered to be hampered by a wide range of intersecting factors (OECD, 2021). These factors include migrants' frequently precarious employment conditions (Fassani & Mazza, 2020; Jayaweera & Anderson, 2008), lower educational attainment levels (Stevens & Dworkin, 2019), their experiences of discriminatory and racist attitudes and policies (Castañeda et al., 2015), their disproportionate exposure to material deprivation, and the restrictions they may face regarding their access to health care and social security (Gkiouleka & Huijts, 2020). Despite these overall disadvantaged positions in society, migrants are a highly heterogeneous population, making it difficult to generalize the extent to which they are ‘vulnerable’.

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, negative consequences faced by migrants similarly relate to various intersecting factors and circumstances. For example, migrants may be at increased risk of exposure to COVID-19 in their workplace and as a result of crowded living conditions (Greenaway et al., 2021). In addition, COVID-19 lockdown measures may have a disproportionate impact on the members of migrant populations, particularly on those with an undocumented legal status, working in informal or precarious job sectors, or living in poor housing conditions (Burton-Jeangros et al., 2020; Ullah et al., 2021). Migrants' mental health has been found to be significantly impacted by the COVID-19 crisis, particularly for subgroups of older migrants, those with insecure housing situation and residence status, and female migrants (Spiritus-Beerden et al., 2021). Given the diversity in migrant populations' experiences, it is relevant to explore the discourses that frame migrants as ‘vulnerable’ in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in more depth.

The use of the term ‘vulnerability’ to describe groups of people is not new. The concept has gained considerable popularity in recent decades, becoming increasingly commonplace in the lexicon of policy makers, journalists and academics (Brown, 2011). However, considerable ambiguity surrounds the concept, as it is often used without precise definitions of “who is vulnerable, why they are vulnerable, and what they are vulnerable to” (Katz et al., 2020, p. 601). The relational use of the term (being vulnerable to something, such as drug use or illness) now seems to be used less, whereas the use of vulnerability as a stand-alone term (calling someone or a group of people vulnerable) has become more common (Brown, 2011). Clearly, being vulnerable means different things to different people.

The conceptual ambiguity of the usage of ‘vulnerable’ in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic deserves scrutiny, because the underlying discourses around the reasons why certain groups are considered ‘vulnerable’ and the language used to describe their vulnerability could frame the ways in which the needs of these diverse groups of people are approached in policy and practice. Ideas about vulnerability shape how “we manage and classify people, justify state intervention in citizens' lives, allocate resources in society and define our social obligations” (Brown, 2011, p. 313).

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, the concept of vulnerable groups or populations is potentially useful to expose how some groups of people, such as some groups of migrants, are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, as well as to explore how pandemic responses can address these inequalities. However, there are also potentially negative implications of labelling groups of people as ‘vulnerable’. The concept of vulnerability has been critiqued by social science scholars for being patronising and oppressive, as it focuses on perceived deficit and weakness (Brown, 2011; Wishart, 2003). Calling groups or individuals vulnerable has also been described to result in exclusion and stigmatisation, by connecting to notions of difference (Brown, 2011; Harrison & Sanders, 2006). Within the field of public health, many texts use the term in a way that implies inherent vulnerability, suggesting that “the populations they name or gesture to are vulnerable in a way that exists outside of social, historical, political and economic realities” (Katz et al., 2020, p. 604). Scholars have warned that such presumed inherent vulnerability can draw away attention from the need to tackle structural causes of vulnerability (Brown, 2011; Katz et al., 2020; Lansdown, 1994). Indeed, the concept of vulnerability is closely linked with ideas about responsibility, choice and blame (Brown, 2011). When applied to migrants, the concept may be used in ways that reproduce pre-existing stereotypes relating to gender, ethnicity, and citizenship (Grotti et al., 2018; Sözer, 2019). As such, negative consequences of labelling migrants as vulnerable in the pandemic context include the potential for patronisation, stigmatisation, stereotyping, and distracting from structural causes of social inequality.

This article sets out to analyse the academic use of the term ‘vulnerable’ to describe migrants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using critical discourse analysis (CDA) methods, our analysis explores what is meant when the concept of vulnerability is used to describe or explain the experiences of migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic in academic publications from across public health and social science disciplines. Our analysis operationalizes the four validity claims from Habermas' theory of communicative action to examine the discourses that frame migrants as vulnerable groups in the COVID-19 crisis and to identify the assumptions and abstractions which underlie these conceptualizations of vulnerability. CDA methods are well-suited to examining how migrants are framed as ‘vulnerable’, as they include a specific focus on relations of power and inequality (Fairclough, 2013; van Dijk, 1995b; Wodak, 1996). Our methodological approach thus allows us to highlight how the academic use of the term ‘vulnerable’ to describe migrants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic may both reflect and reinforce societal power relations.

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical framework

The term Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is used as an overarching label for interdisciplinary forms of discourse analysis with a special focus on the relations between discourse and society (van Dijk, 1995a). The CDA method employed for our analysis uses Habermas' theory of communicative action as a foundation. Habermas theorizes that an ideal speech situation or ideal discourse can occur when no one is excluded, and participants can evaluate each other's assertions solely on the basis of reason and evidence, free of coercive influences (Habermas, 2003). Scientific discourse has been designed to function like an ideal speech situation, in which academic publications allow researchers to present alternative ideas without fear of exclusion or repercussions (Dant, 1991; Wall et al., 2015). However, like in any genre of discourse, some thought patterns and worldviews may become ingrained in the theoretical assumptions and epistemological beliefs of scientific discourse. This conscious or unconscious domination of particular thought patterns has been referred to as ideological hegemony (Fleck, 1979; Foucault, 1970, ; Kuhn, 2012). One of the ways in which this hegemony can manifest itself in academic publication is as a common framing of research topics and lines of inquiry (Wall et al., 2015). Hegemonic participation in communication can be identified by assessing violations of Habermas' four validity claims: comprehensibility, truthfulness, legitimacy and sincerity (Habermas, 1984). Building on previous work using Habermas' theory of communicative action as a conceptual framework for CDA (Cukier et al., 2004; Forester, 1983; Wall et al., 2015), we use these validity claims to guide our discourse analysis.

Comprehensibility refers to the “technical and linguistic clarity of communication” (Cukier et al., 2009, p. 179) and can be assessed by evaluating whether the communication is sufficiently intelligible and theoretical concepts and scientific jargon are clearly defined (Wall et al., 2015). Truthfulness concerns the propositional content of what is said is factual or true (Cukier et al., 2009; Habermas, 1984). Truthfulness can be assessed by evaluating the completeness of authors' argumentation, to determine whether evidence warrants the claims being made (Cukier et al., 2004; Wall et al., 2015). Legitimacy refers to the representation of different perspectives and “competing logics”, and can be assessed through evaluations of who is considered an “expert” and by comparing framing of issues and concepts across different texts (Wall et al., 2015). Finally, sincerity refers to whether the way something is communicated is consistent with what the author intends to communicate (Cukier et al., 2009; Habermas, 1984). This may be challenging to assess if an author is engaged in unconscious hegemonic participation and communicates on the basis on taken-for-granted beliefs and assumptions. However, evaluations can be based on text elements such as generalizations and connotative and/or hyperbolic language (Wall et al., 2015). For our analysis, we operationalized Habermas’ validity claims by developing a series of questions to facilitate the identification of comprehensibility, truthfulness, legitimacy and sincerity claims in the texts (see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Coding scheme using Habermas’ validity claims for analysis of publications, adapted from Cukier et al. (2004) and Wall et al. (2015).

| Validity claim | Evaluation of claim | Specific questions for evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensibility | Assessment of the intelligibility, completeness and clarity of communication. |

|

| Truthfulness | Assessment of the prepositional content of what is said is factual or true as represented by complete arguments and sufficient evidence. |

|

| Legitimacy | Assessment of how competing logics and views are represented. |

|

| Sincerity | Assessment of whether the way something is communicated is consistent with what the author intends to communicate. |

|

We chose to conduct an interdisciplinary analysis, as we believe theoretical assumptions and epistemological beliefs regarding the concept of vulnerability run across scientific disciplines. Reflecting our own theoretical background and training, we therefore included publications from across the public health and social science disciplines.

2.2. Data collection and screening

We carried out a cross-disciplinary critical discourse analysis of academic use of the term ‘vulnerable’ to describe migrants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Inspired by a review methodology proposed by Wall et al. (2015), we used critical discourse analysis as a narrative review methodology. We focused our analysis on international migrants, excluding internal or domestic migrants. In line with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) definition of an international migrant, we consider this to include any person who is outside their state of birth or habitual residence (IOM, 2019). The term ‘migrant’ is used and conceptualized differently across contexts, disciplines and studies (Anderson & Blinder, 2019). Reflecting usage in public debates, we did not solely focus on the legal definition of a migrant, but rather used it as an umbrella concept that covers both international migrants and their descendants. Since we extended our analysis to people who are described as having a migrant or migratory background, this may include children or even grandchildren of people who migrated (second- or third-generation migrants).

We were guided by the PRISMA method of literature search to identify appropriate publications for analysis (cf. Page et al., 2021). We screened for articles in Scopus with any form of the word ‘vulnerable’ (i.e. vulnerab∗), in combination with any form of the word migrant/migratory/migration (i.e. migr∗) and any mention of the COVID-19 pandemic listed in the title, abstract or key words, published before July 27, 2021. Our Scopus search yielded 263 articles. We screened articles using the following inclusion criteria, based on their abstract:

-

•

Publication uses concept of vulnerability to describe migrants or people with a migration background in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

-

•

Publication focuses on international migration/migrants

-

•

Publication is written in English

-

•

Publication is located in public health and/or social science disciplines

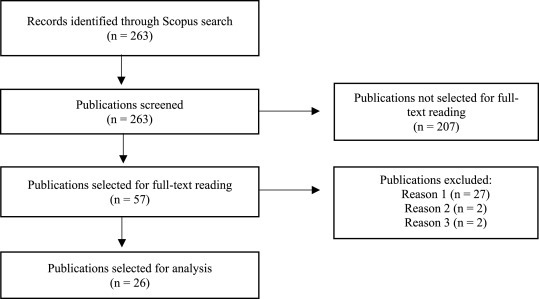

After initial screening based on reading the abstracts of all 263 articles, we identified 57 papers for full-text reading (see Fig. 1 ). To ensure the papers included for analysis had a substantial focus on vulnerability rather than using the concept transiently, in our second round of screening we applied the additional inclusion criterion that publications must have at least 5 mentions of vulnerab∗ in the main body of the text. Based on this additional inclusion criterion, 26 articles were selected for further analysis. Out of the 31 papers excluded after full-text reading, 27 papers were excluded because they had fewer than 5 mentions of vulnerab∗ in the main body of the text (reason 1). Two publications were excluded because they were not fully in English (reason 2), and two papers were excluded because the focus was on domestic migration rather than international migration (reason 3). For an overview of the papers included for analysis, see Table 2 listing article characteristics in the supplementary materials.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of review stages using Scopus database.

2.3. Data analysis

Analysis of the 26 articles was carried out using a coding scheme to guide the analysis based on Habermas’ four validity claims. Our scheme in Table 1 is inspired by schemes proposed by Cukier et al. (2004) and Wall et al. (2015) and provides specific questions to facilitate identification of comprehensibility, truthfulness, legitimacy and sincerity claims in the texts. We conducted a computer-aided qualitative analysis (NVivo 12.6) of the texts to facilitate reading, coding and interpretation. We started data analysis by full-text reading of all 26 articles meeting inclusion criteria, with a specific focus on the text sections which refer to the concept of vulnerability. In-depth reading was followed by coding by validity claim (in line with our coding scheme) to facilitate content analysis. Coding by validity claim helped to keep our interpretations grounded in the article texts. Once all included publications were coded, we carried out a comparative thematic analysis to understand key patterns and divergences across articles. Throughout our coding and interpretative analysis, we maintained a focus on how the use of the concept of vulnerability may both reflect and reinforce societal power relations, in line with central aims in CDA approaches.

3. Findings

As summarized in Table 2 in the supplementary materials, the 26 publications included for analysis constitute a relatively diverse sample in terms of their scope and disciplinary orientation. The majority of the papers are focused on migrants in the Northern hemisphere: nine publications focus on the European context and nine publications on North America. Of the remaining publications, four have an international/cross-continental focus; another two focus on South America; one on Asia; and one on Africa. More than half of the publications included for analysis did not present any empirical data. Out of the 26 publications, 11 were based on empirical research findings, and four out of these 11 only included data collection among professionals working with migrants or other ‘key informants’, not with migrants themselves. Eleven publications were commentaries or ‘viewpoints’.

Below, we present a thematic overview of our findings. Guided by Habermas’ four validity claims, we examine how vulnerability is defined and described in the included publications (comprehensibility); on what basis migrants are considered vulnerable (truthfulness); as well as instances of inconsistencies, exclusion and generalization (legitimacy and sincerity).

3.1. Comprehensibility: defining and describing vulnerability

To evaluate Habermas' validity claim of comprehensibility, we analysed whether publications clearly defined their usage of the concept of vulnerability and whether definitions and descriptions of vulnerability were comprehensible and consistent. In coding for definitions and descriptions of migrants' vulnerability, we observed widespread definitional ambiguity. Although all 26 publications included for analysis used a form of the word vulnerable (vulnerab∗) at least five times in the main body of the text, only three publications (Falkenhain et al., 2021; Maďarová et al., 2020; Tagliacozzo, Pisacane, & Kilkey, 2021) explicitly reflected upon definitions of vulnerability in the beginning of the text to provide conceptual clarity. In each of these three papers, the authors acknowledged the lack of consensus on the meaning of the concept of vulnerability and clearly outlined their working definition of the concept. A paper on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on marginal migrant populations in Italy defined its reliance on a “cumulative vulnerability framework” to examine various determinants of migrants' vulnerability (Sanfelici, 2021). Furthermore, a paper by Quandt et al. (2021) did provide a definition of their use of the concept of ‘contextual vulnerability’, but only in the discussion section, after having used the concept of vulnerability to describe immigrants several times. All other papers use the concept of vulnerability repeatedly without providing a definition. Across these publications, the term is applied as a descriptor with seemingly taken-for-granted applicability. Descriptions of migrants as vulnerable are often made in sentences which describe the difficult circumstances faced by migrants during and prior to the pandemic:

“It is not a mystery that migrants often must face discrimination, poor living conditions, social exclusion, informal and precarious employment, among other issues that, in this current pandemic context, reinforces their condition of vulnerability” (Jara-Labarthé & Cisneros Puebla, 2021, p. 286)

“Migrant workers, with their marginal socio-legal status in host countries, are especially vulnerable during the pandemic […]” (Wang et al., 2020, p. 7)

In some cases, the label ‘vulnerable’ is used in combination with other adjectives without explaining the distinction between the two terms, such as in descriptions of “vulnerable and stigmatized groups” (Cross & Gonzalez Benson, 2021, p. 115) or “low-income and vulnerable US populations” (Clark et al., 2020, p. 1). Although such combined descriptors could be seen to hint at the intersectional nature of disadvantage migrants might face, articles typically did not elaborate on how various descriptors used may connect and overlap.

In many publications, migrants are described as one among multiple vulnerable groups in the COVID-19 pandemic:

“Like other vulnerable groups, refugee newcomers are particularly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the exacerbation of factors that already hinder their access to the health care services” (Smith et al., 2021, p. 210).

Oftentimes, as in the example above, these other vulnerable groups are not specified. This suggest migrants are often seen to belong to the generic category of ‘vulnerable groups’, without extensive consideration of the distinctive root causes of their supposed vulnerability.

3.2. Truthfulness: causes and drivers of vulnerability

To evaluate Habermas' claim of truthfulness, we examined for what reasons migrants are considered vulnerable in the publications included for analysis, as well as what argumentation and evidence is used to support conceptualizations of these drivers of migrants’ vulnerability. Our analysis reveals that migrants are considered vulnerable in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic for a wide variety of reasons. The most frequently mentioned drivers of vulnerability related to poverty or low economic status; precarity; access to healthcare; discrimination; language barriers; and increased exposure and risk of contracting COVID-19.

Firstly, many descriptions of migrants' vulnerability are linked to poverty or low economic status. Factors such as “low levels of incomes and therefore reduced capacity for savings” (Cramarenco, 2020, p. 111), “unstable housing, underemployment and underpayment” (Falicov et al., 2020, p. 8), and “excessive stress related to poverty” (Clark et al., 2020, p. 2) were frequently mentioned as drivers of vulnerability. Across publications, migrants are described as a group that disproportionately experiences financial hardship, claims which some articles support with evidence, e.g. on poverty rates among migrant groups. The pathways through which economic status drives vulnerability are not typically elucidated in much detail, but there is a wide-spread implication that migrants’ economic status limits their ability to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in a way that protects them from experiencing negative consequences.

Many papers use the word precarity (or precariousness) to describe this type of insecurity and absence of control. Precarity is particularly used in the context of precarious employment. Migrants are described as being “overrepresented in low skilled precarious jobs” which are often “so-called 3D jobs (dirty, difficult and dangerous)” (Cramarenco, 2020, p. 110). Migrant workers frequently face “temporary contracts and abusive practices” (Maďarová et al., 2020, p. 22), or informal working relations “without an employment contract or social benefits” (Jara-Labarthé & Cisneros Puebla, 2021, p. 287), resulting in “vulnerability to exploitation” (Tagliacozzo, Pisacane, & Kilkey, 2021, p. 9). Precarity is also linked to some migrants’ precarious legal status, which for undocumented migrants in particular may create a “constant fear of being deported” (Wang et al., 2020, p. 17) and be an important element of “migration-related stress” (Cross & Gonzalez Benson, 2021, p. 115). A precarious legal status is also often associated with “lack of access to social benefits or very limited, if any, access to healthcare services” (Cramarenco, 2020, p. 110).

Indeed, access to healthcare is another frequently mentioned driver of migrants’ vulnerability in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Migrants are described as “facing barriers to access the health system” (Martuscelli, 2021, p. 3), lacking “freedom or choice of decision to access health care” (Molobe et al., 2020, p. 2), and struggling with “inaccessibility of public health insurance” (Serafini et al., 2021). Migrants are also described to face various types of discrimination when accessing health services.

Discrimination is considered a cause of migrants' vulnerability in society at large, too. Various publications describe migrants as having been unfairly blamed for spreading COVID-19, increasing “xenophobia, racism, and discrimination” (Martuscelli, 2021, p. 4). This worsens migrants’ pre-existing “disproportionate exposure to social discrimination” (Wang et al., 2020, p. 9), and may “manifest in discriminatory behaviours such as social stigma” (Quandt et al., 2021, p. 4).

Furthermore, language barriers are considered an important driver of migrants’ vulnerability. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, language barriers are seen as resulting in poor awareness and understanding of public health regulations and as hampering “emergency communication and health-seeking behaviour” (Molobe et al., 2020, p. 2). Limited proficiency in the local language can also increase “susceptibility to misinformation” (Smith et al., 2021, p. 211) and result in migrants experiencing “more uncertainty about the disease and the future” (Martuscelli, 2021, p. 13).

In addition to the factors discussed above, papers also frame migrants' vulnerability by discussing migrants' specific exposure and health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic. In most of the included papers, conceptualization of migrants’ vulnerability included references to differential exposure to the novel coronavirus. A “higher likelihood of exposure to COVID-19” (Kline, 2020, p. 240) is frequently linked to the conditions in which migrants live and work. In some instances, vulnerability seems to be considered synonymous with exposure to viral infection:

“Exposures and vulnerability to infection are intensified by dangerous work conditions and essential jobs, overcrowded housing, and neighborhoods that lack protective supplies and preventive information.” (Falicov et al., 2020, p. 8)

Apart from an increased risk of exposure, some publications also refer to migrants' increased risk of falling seriously ill or dying from COVID-19 once infected, for example “due to the higher prevalence of underlying physical and mental comorbidities compared to the general population” (Ralli et al., 2020, p. 9765). A few publications acknowledge that higher rates of viral transmission and disease severity cannot be viewed in isolation from social determinants of health, including migrants’ physical environment, employment, social support networks, and economic stability. For example, their “particular vulnerability” is described by Quandt et al. (2021) as “an example of social injustice, linked to structural inequalities” (p. 30).

A common sentiment in the 26 publications was that the COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated pre-existing drivers of migrants' vulnerability. The pandemic is described as having “aggravated previous vulnerabilities” (Martuscelli, 2021, p. 2); having “thrown into sharp focus the unique vulnerabilities” [migrants face] (Colindres et al., 2021, p. 2) and posing a “disruptive event that magnifies their vulnerability” (Falkenhain et al., 2021, p. 450). Although many publications do not specify exactly how this exacerbation or magnification has occurred, there is a general sentiment that drivers of vulnerability such as migrants’ access to healthcare, working and living conditions, discrimination and language barriers became more poignant and more visible in the ongoing health crisis.

3.3. Legitimacy: inconsistency, contradiction and marginalization

To evaluate Habermas' claims of legitimacy, we examined how assumptions relating to migrants' vulnerability differ across publications; who is considered an expert; and whose perspectives are marginalized or excluded from the discourse. A key difference in the assumptions underlying conceptualizations of migrants' vulnerability is the extent to which vulnerability is presented as an inherent and passive state, as opposed to as an outcome of dynamic and structural processes. In most publications included for analysis, the inequities and difficult circumstances which contribute to migrants’ vulnerability are construed as taken-for-granted conditions or given characteristics of the societies in which migrants live. Some publications, however, include a consideration of the power relations that underlie the issues described as drivers of vulnerability. For example, Maďarová et al. (2020) underline how the distribution of vulnerability follows “structural and systemic power relations” (p. 12), while Cross and Gonzalez Benson (2021) emphasize the need to pay attention to difference “as constituted by overlapping domains of power” (p. 116).

Another trend relevant to the evaluation of legitimacy claims is how conceptualizations of migrants' vulnerability were sometimes used to advance seemingly contradictory policy implications or conclusions. More specifically, in some publications vulnerable migrants were represented both as helpless and as a threat. On the one hand, authors typically argued that migrants' vulnerability in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic warrants additional (government) intervention and support to protect them. On the other hand, several publications acknowledged that migrants are sometimes perceived as a group that poses a threat to security, including health security. For example, Elisabeth et al. (2020) claim “the spread of COVID-19 may not be totally controlled if these vulnerable populations are not included in the national response”, while Tagliacozzo, Pisacane, & Kilkey, 2021 note that when the pandemic broke out, migrants' working and living conditions resulted in them being framed as “a health-risk factor for the entire society” (p.14). Similarly, De Nardi and Phillips (2021) observe how migrants in Italy and Australia were “blamed and scapegoated by the mainstream as agents of infection” (p. 8). In other words, addressing drivers of migrants’ vulnerability is sometimes argued to be of broader relevance, as paying attention to their needs “will not only benefit the most vulnerable but also will benefit us all” (Molobe et al., 2020, p. 4).

In relation to the prioritization of some viewpoints and the exclusion of others, it is relevant to reiterate that more than half of the publications included for analysis did not present any empirical data. Indeed, only 11 out of 26 publications were based on empirical research findings, and 4 out of these 10 did not include data collection with migrants themselves. As such, authors of publications often position themselves as experts on migrants' vulnerability in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic without including migrants' viewpoints. Naturally, this should be seen in light of the difficulties of collecting data in times of a pandemic, as well as the relatively slow speed of academic publishing – many empirical studies might have not been published yet by July 2021. The widespread exclusion of migrants' views and experiences from this academic discourse could also be linked to what has been called the “rat race to publishing on COVID-19” (Parmar, 2020). The rush to publish and the deluge of rapidly published COVID-19 related publications have likely contributed to the marginalization of migrants’ own notion of their potential vulnerability, hereby undermining legitimacy claims.

3.4. Sincerity: rhetorical devices and generalizability claims

To examine Habermas’ sincerity claim, we analysed the use of rhetorical devices and the use of generalizability claims. Although our analysis did not reveal widespread use of rhetorical devices that could be seen to undermine sincerity claims, we did observe instances in which labelling of migrants as vulnerable implied the generalizable relevance of this term. Migrants were frequently labelled as vulnerable without recognition of the diverse lived experiences and heterogeneity within this group, nor consideration of the extent to which migrants themselves identify with this label. Across papers, vulnerability was predominantly an externally imposed descriptor. Only a handful of papers went into differential experiences within migrant communities, e.g. by emphasising how vulnerability is strongly dependent on individual characteristics as well as structural causes (Martuscelli, 2021). A paper based on a study which included qualitative interviews with refugees in Germany noted that COVID-19 has not necessarily worsened experiences of vulnerability for everyone: “while some [migrants] expressed insecurity and disorientation, others reacted to the pandemic-induced disruptions with confidence and self-determination” (Falkenhain et al., 2021, p. 460).

4. Discussion

Our discourse analysis of the use of the term ‘vulnerable’ in social sciences and public health publications to describe migrants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic revealed widespread definitional vagueness of the concept of vulnerability. In most publications included for analysis, the term ‘vulnerable’ was used as an undefined descriptor that was based on a complex assemblage of taken-for-granted abstractions and assumptions. Apart from widespread definitional vagueness, our analysis also identified and problematised assumptions presenting vulnerability as an inherent and passive state; the contradictory implications attached to migrants' presumed vulnerability; the exclusion of migrants' own views and experiences; and the use of generalizability claims.

The definitional ambiguity and presumed widespread relevance surrounding the concept of vulnerability highlighted in our discourse analysis has previously been subjected to critique, particularly within the social sciences. For example, Sözer (2019) has critiqued the self-evident value attributed to the notion of vulnerability when applied to refugees. She warns that preconceived notions of vulnerability may function as ‘categories that blind us’, because fixed understandings of vulnerability cannot fully grasp the dynamic and contextual nature of refugees' experiences. She also points out how due to its malleability, the concept of vulnerability notion can be subverted, manipulated or reinvented in light of divergent “political–ideological dispositions about citizenship, religion, ethnicity and gender” (Sözer, 2019, p. 11). This is in line with our finding that conceptualizations of migrants' vulnerability were sometimes used to advance seemingly contradictory policy implications or conclusions. Correspondingly, Grotti et al. (2018) have described how conceptualizations of the vulnerability of pregnant migrants entering the European Union were constructed not just through understandings of structural impediments to healthcare and other human rights, but also through pre-existing cultural and gendered stereotypes. This highlights how particular pre-existing thought patterns and preconceptions may become ingrained in discourses around concepts like vulnerability, hereby reinforcing hegemonic ideas about societal power relations. An additional concern expressed by Sözer (2019) of relevance to our findings relates to how reliance on the notion of vulnerability may contribute to exclusion and discrimination, as differentiations between the vulnerable and the invulnerable are often operationalized to distinguish between those considered deserving and undeserving of assistance.

Similar concerns have been raised in the public health literature: some scholars see the concept of vulnerability as being connected to notions of difference, which can result in further exclusion and stigmatisation of individuals and groups of people (Munari et al., 2021). Vladeck (2007) has even argued that the use of the concept of vulnerable populations in public health “arises more from the pressures for euphemism in the discussion of health policy and health services than from any intellectual power inherent in the concept” (p. 1232). Our finding that many publications framed migrants’ vulnerability as an inherent and passive state, brought about by given characteristics of the societies in which migrants live, has also previously been critiqued. For example, Katz. et al. (2020) have argued that when the mechanisms by which vulnerability is produced are not adequately specified and explained, this leaves readers to fill in the blanks and risks implying that vulnerability results from intrinsic deficits or inferiority, rather than structural processes. As such, indiscriminate use of the notion of vulnerability may imply that vulnerability is a given, suggesting that positive change is simply not conceivable. This can be harmful, because both in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond it, the social conditions which shape unequal outcomes are not inevitable or fixed: they “are constructed by people” (Krieger, 1994, p. 899).

How can the concept of vulnerability, when applied to migrants, be conceptualized and operationalized in more productive ways? In defining and approaching the vulnerability of migrants in the COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath, we suggest following Zarowsky et al.’s (2013) approach to understanding vulnerability as both a condition and a process. In their conceptual framework, the process of ‘vulnerabilisation’ is driven by three main elements, all of which are shaped by social inequalities: 1) the initial situation, position and wellbeing of specific individuals or groups; 2) their exposure to risks or shocks; and 3) their capacity to manage risk and cope with negative impact. This approach is particularly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the crisis' specific risks and shocks have more heavily impacted specific groups of people. It encourages thinking about the most commonly described drivers of vulnerability identified in our discourse analysis – poverty or low economic status; precarity; access to healthcare; discrimination; language barriers; and increased exposure and risk of contracting COVID-19 – within a structured, temporal framework. Thinking about vulnerability as the outcome of a process also provides a move away from conceptualizing vulnerability as a fixed and static label that establishes boundaries around specific groups of people. Instead, it highlights that the process of vulnerabilisation is potentially avoidable and reversible, and that people who are vulnerable at a specific point in time in particular contexts are not permanent victims (Zarowsky et al., 2013).

As highlighted by Zarowsky et al. (2013), the dynamic interactions between different drivers of vulnerability can usefully be analysed in a complex systems framework. Complex systems theory focuses on the structure, interactions and dynamics of complex adaptive systems, which change according to the dynamic components or elements they are comprised of (Thurner et al., 2018). The use of a complex systems framework helps emphasize the importance of nonlinear causality and contextual factors, hereby supporting a view of vulnerability as a potential outcome of dynamic interactions (Zarowsky et al., 2013). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, complex systems analysis can facilitate a more holistic understanding of the complex interconnections between health, economic, and social aspects of the crisis (Sahin et al., 2020). As such, it can help demonstrate how impacts and outcomes of the pandemic at the individual and community levels are effects of complex and densely networked socioeconomic, ecological, political, health, institutional, community, cultural, and informational systems. When applied to migrants, complex systems analysis helps conceptualize vulnerability as a dynamic outcome of social order and power relations: migrants’ vulnerabilities are produced within the circumstances they live in and reproduced through their interactions with system components. In other words, it helps draw attention to how external factors and challenges, located outside of an individual or group, shape experiences of vulnerability. Finally, a focus on the dynamic and contextual nature of vulnerability also allows for consideration of the heterogeneity of the experiences within a group as diverse as migrants, avoiding unhelpful and inaccurate generalizations.

Our analysis shows that CDA methods are helpful in shedding light on “how social phenomena are discursively constituted: it demonstrates how things come to be as they are, that they could be different, and thereby that they can be changed” (Hammersley, 2003, p. 758). CDA can provide a methodological basis for contesting hegemonic discourses on social structuring by identifying the dominant assumptions in a particular discourse and highlighting the ramifications of those assumptions (Fairclough, 2013). It hereby helps remind us that language is not neutral: social categories like vulnerability shape the way we understand societal power imbalances and how we decide to respond to them. Although a diverse group of scholars have argued that vulnerability is an inevitable part of the human condition and that it can offer a unifying foundation for a more equitable and just society (Butler, 2004, e.g. 2009; Fineman, 2008; Mboya, 2018; Rodriguez, 2017), our discourse analysis highlights that it is also a concept that must be ‘handled with care’ (Brown, 2011).

Our analysis has several limitations. Firstly, the scope of our analysis is relatively small due to our chosen focus on academic publications about the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. A larger study would be needed in order to understand broader societal discursive patterns relating to migrants as a vulnerable group in the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, we limited our analysis to reviewing the use of the term ‘vulnerable’, even though there are other terms which are similarly used without sufficient critical reflection, such as ‘underserved’, ‘disenfranchised’, ‘at risk’, ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘marginalized’ (Munari et al., 2021). The selected papers have a geographic bias, as more than two-thirds of the publications studied Europe, the USA or Canada. This likely reflects existing inequalities and biases in academic funding and publication, as well as our exclusion of publications written in languages other than English. It is also possible that scholars in the Northern hemisphere more frequently frame migrants as vulnerable, compared to scholars located in other geographic areas. We selected for publications that used a form of the word migrant/migratory/migration as a key term. As a result, publications that focused on a broad range of ‘types’ of migrants were included, such as refugees, migrant workers, and second- or even third-generation migrations. However, publications that relied more specifically on terms like ‘refugees’ might not have been identified using our search terms. Therefore, future research is needed to address the specificities of these judicial categories and how they are framed as ‘vulnerable’.

We acknowledge that we only presented an overview of general framings of migrants' vulnerability in the COVID-19 pandemic, and could not accurately represent the different discourses presented in the 26 papers included for analysis. Since the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, discourses of migrants’ vulnerability in this context are constantly evolving, and we encourage future research on how the academic discourse on this topic will unfold and affect policymaking in the future. With regards to reflexivity, it is important to underline that our Habermasian CDA approach is based on an interpretive research paradigm, which means our methods ultimately rely on our judgement and subjectivity as researchers (Cukier et al., 2009). As such, our worldviews undoubtedly influenced our research approach and conclusions (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). As we are active in the public health and social science research fields ourselves, it is also possible we were not able to identify all taken-for-granted assumptions.

5. Conclusion

We conducted a critical discourse analysis of the academic use of the term ‘vulnerable’ to describe migrants in the context of the COVID-19, based on a review of publications available on Scopus across public health and social science disciplines. Our findings demonstrate that the concept of vulnerability is frequently applied as a descriptor with seemingly taken-for-granted applicability. Based on our analysis of 26 articles, we found that migrants are considered vulnerable in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic for a wide variety of reasons, most frequently relating to exposure and risk of contracting COVID-19; poverty or low economic status; precarity; access to healthcare; discrimination and language barriers. In most publications included for analysis, the drivers of migrants' vulnerability were construed as immutable societal characteristics. We observed widespread generalizations in the use of the notion of vulnerability, labelling migrants as vulnerable without consideration of the heterogeneity among and between diverse groups of migrants. We also noted how conceptualizations of migrants' vulnerability in the COVID-19 pandemic were sometimes used to advance seemingly contradictory policy implications or conclusions, as in some publications migrants were represented simultaneously as helpless and as a threat to the health and stability of society at large. Furthermore, we observed that migrants' own views and lived experiences of their presumed vulnerability are often excluded from the discourse.

Although some definable groups of people are certainly more likely to suffer harm, particularly in crisis situations like the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of ‘vulnerable’ as a fixed descriptor has potentially negative implications. A static label for heterogeneous groups of people is not necessarily helpful in understanding their dynamic and highly contextual experiences, and uncritical use of the notion of vulnerability risks implying inherent vulnerability, hereby drawing attention away from structural causes. We therefore encourage thinking about the vulnerability of (some) migrants as the outcome of a complex process of ‘vulnerabilisation’, focusing on the ways in which people are affected by and are able to respond to shocks over time. Combined with complex systems thinking, this calls attention to the dynamic interactions that link migrants' position and experiences in health systems, employment/labour markets, and legal systems, as well as the discrimination and racism they face in society at large. By starting from the assumption that vulnerability is dynamic, contextual, and often reversible, and explicitly acknowledging the complex factors driving vulnerabilisation, the concept is useful to expose how some groups of migrants are disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethical statement for SSM – Qualitative research in health

-

1)

This material is the authors' own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

-

2)

The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

-

3)

The paper reflects the authors' own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner.

-

4)

The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers.

-

5)

The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research.

-

6)

All sources used are properly disclosed (correct citation). Literally copying of text must be indicated as such by using quotation marks and giving proper reference.

-

7)

All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper, and will take public responsibility for its content.

Funding source

EU Horizon 2020 COVINFORM project, funded under Grant Agreement No. 101016247. The funding source had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the article; or in the decision to submit it for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jil Molenaar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Lore Van Praag: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues from the COVINFORM project for our discussions about the concept of vulnerability, which helped shape the analysis presented here. We would also like to show our gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers, whose insightful feedback undoubtedly improved the quality of the paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100076.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- Anderson B., Blinder S. The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford; 2019. Who Counts as a migrant? Definitions and their consequences [Briefing]https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/who-counts-as-a-migrant-definitions-and-their-consequences/ [Google Scholar]

- Bambra C., Riordan R., Ford J., Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2020;74(11):964–968. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. ‘Vulnerability’: Handle with care. Ethics and Social Welfare. 2011;5(3):313–321. doi: 10.1080/17496535.2011.597165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Jeangros C., Duvoisin A., Lachat S., Consoli L., Fakhoury J., Jackson Y. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown on the health and living conditions of undocumented migrants and migrants undergoing legal status regularization. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020;8:940. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.596887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. Routledge; London and New York: 2004. Undoing gender. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. Performativity, precarity and sexual politics. AIBR: Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana. 2009;4(3):i–xiii. doi: 10.11156/aibr.040305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H., Holmes S.M., Madrigal D.S., Young M.-E.D., Beyeler N., Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2015;36(1):375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E., Fredricksid K., Woc-Colburn L., Bottazzi M.E., Weatherheadid J. Disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrant communities in the United States. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2020;14(7):1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colindres C., Cohen A., Susana Caxaj C. Migrant agricultural workers’ health, safety and access to protections: A descriptive survey identifying structural gaps and vulnerabilities in the interior of British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(7) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramarenco R.E. On migrants and COVID-19 pandemic—an analysis. On-line Journal Modelling the New Europe. 2020;23:1–21. doi: 10.24193/OJMNE.2020.34.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cross F.L., Gonzalez Benson O. The coronavirus pandemic and immigrant communities: A crisis that demands more of the social work profession. Affilia - Journal of Women and Social Work. 2021;36(1):113–119. doi: 10.1177/0886109920960832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cukier W., Bauer R., Middleton C. In: Information systems research: Relevant theory and informed practice. Kaplan B., Truex D.P., Wastell D., Wood-Harper A.T., DeGross J.I., editors. Springer US; 2004. Applying Habermas' validity claims as a standard for critical discourse analysis; pp. 233–258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cukier W., Ngwenyama O., Bauer R., Middleton C. A critical analysis of media discourse on information technology: Preliminary results of a proposed method for critical discourse analysis. Information Systems Journal. 2009;19(2):175–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2008.00296.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dant T. Routledge; London and New York: 1991. Knowledge, ideology, and discourse: A sociological perspective. [Google Scholar]

- De Nardi S., Phillips M. The plight of racialised minorities during a pandemic: Migrants and refugees in Italy and Australia. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. 2021 doi: 10.1108/EDI-08-2020-0248. Scopus. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Sage Publications Ltd; London: 2005. Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk T.A. Aims of critical discourse analysis. Japanese Discourse. 1995;1:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk T.A. Discourse semantics and ideology. Discourse & Society. 1995;6(2):243–289. doi: 10.1177/0957926595006002006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elisabeth M., Maneesh P.-S., Michael S. Refugees in Sweden during the Covid-19 Pandemic—the need for a new perspective on health and integration. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.574334. 8. Scopus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. 2nd ed. Routledge; London and New York: 2013. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov C., Niño A., D’Urso S. Expanding possibilities: Flexibility and solidarity with under-resourced immigrant families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Family Process. 2020;59(3):865–882. doi: 10.1111/famp.12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenhain M., Flick U., Hirseland A., Naji S., Seidelsohn K., Verlage T. Setback in labour market integration due to the Covid-19 crisis? An explorative insight on forced migrants’ vulnerability in Germany. European Societies. 2021;23(S1):S448–S463. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1828976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fassani F., Mazza J. Publications Office of the European Union Luxembourg; 2020. A vulnerable workforce: Migrant workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman M. The vulnerable subject: Anchoring equality in the human condition. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 2008;20(1) https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlf/vol20/iss1/2 [Google Scholar]

- Fleck L. University of Chicago Press; 1979. Genesis and development of a scientific fact.https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/G/bo25676016.html [Google Scholar]

- Forester J. In: Beyond method: Strategies for social research. Morgan G., editor. Sage; London: 1983. Critical theory and organizational analysis; pp. 234–346. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. 1st ed. Pantheon Books; 1970. The Order of Things: An archaeology of the human sciences. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garoon J.P., Duggan P.S. Discourses of disease, discourses of disadvantage: A critical analysis of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(7):1133–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkiouleka A., Huijts T. Intersectional migration-related health inequalities in Europe: Exploring the role of migrant generation, occupational status & gender. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;267:113218. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway C., Hargreaves S., Barkati S., Coyle C.M., Gobbi F., Veizis A., Douglas P. COVID-19: Exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2021;27(7) doi: 10.1093/JTM/TAAA113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotti V., Malakasis C., Quagliariello C., Sahraoui N. Shifting vulnerabilities: Gender and reproductive care on the migrant trail to Europe. Comparative Migration Studies. 2018;6(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J. Beacon Press; Boston: 1984. The theory of communicative action: Reason and the rationalization of society. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J. MIT Press; 2003. Truth and justification. B. Fultner, Trans. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M. Conversation analysis and discourse analysis: Methods or paradigms? Discourse & Society. 2003;14(6):751–781. doi: 10.1177/09579265030146004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M., Sanders T. In: Supporting safer communities: Housing, crime and neighbourhoods. Newburn T., Dearling A., Somerville P., editors. Chartered Institute of Housing; 2006. Vulnerable people and the development of “regulatory therapy; pp. 155–168.http://www.cih.org/ [Google Scholar]

- IOM . International Organization for Migration; 2019. Glossary on migration (No. 34)https://www.iom.int/glossary-migration-2019 [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Labarthé V., Cisneros Puebla C.A.… Migrants in Chile: Social crisis and the pandemic (or sailing over troubled water) Qualitative Social Work. 2021;20(1–2):284–288. doi: 10.1177/1473325020973363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera H., Anderson B. Centre on Migration, Policy and Society; 2008. Migrant workers and vulnerable employment: A review of existing data. [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Tvedten I. What does it mean to be poor? Investigating the qualitative-quantitative divide in Mozambique. World Development. 2019;117:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A.S., Hardy B.-J., Firestone M., Lofters A., Morton-Ninomiya M.E. Vagueness, power and public health: Use of ‘vulnerable‘ in public health literature. Critical Public Health. 2020;30(5):601–611. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2019.1656800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I. COVID-19 and the ‘rediscovery’ of health inequities. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2020;49(5):1415–1418. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline N.S. Rethinking COVID-19 vulnerability: A call for LGTBQ+ Im/migrant health equity in the United States during and after a pandemic. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):239–242. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Epidemiology and the web of causation: Has anyone seen the spider? Social Science & Medicine. 1994;39(7):887–903. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90202-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn T.S. 4th ed. University of Chicago Press; 2012. The structure of scientific revolutions.https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo13179781.html [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown G. In: Children's childhoods: Observed and experienced. Mayall B., editor. Psychology Press; 1994. Childrens rights; pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Maďarová Z., Hardoš P., Ostertágová A. What makes life grievable? Discursive distribution of vulnerability in the pandemic. Czech Journal of International Relations. 2020;55(4):11–30. doi: 10.32422/mv-cjir.1737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martuscelli P.N. American Behavioral Scientist; 2021. How are forcibly displaced people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak? Evidence from Brazil. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboya A. Vulnerability and the climate change regime. UCLA Journal of Environmental Law and Policy. 2018;36(1) https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5zx443v9 [Google Scholar]

- Molobe I.D., Odukoya O.O., Isikekpei B.C., Marsiglia F.F. Migrant communities and the COVID-19 response in sub-Saharan Africa. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;35(Suppl 2) doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.22863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munari S.C., Wilson A.N., Blow N.J., Homer C.S.E., Ward J.E. Rethinking the use of ‘vulnerable. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.13098. n/a(n/a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2021. International migration outlook 2021.https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/international-migration-outlook-2021_29f23e9d-en [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt M., Patel P., Burns R., Hiam L., Aldridge R., Devakumar D., Kumar B., Spiegel P., Abubakar I. Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1482–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., Chou R., Glanville J., Grimshaw J.M., Hróbjartsson A., Lalu M.M., Li T., Loder E.W., Mayo-Wilson E., McDonald S., Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine. 2021;18(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar A. Panic publishing: An unwarranted consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;294:113525. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips T. The Guardian; 2021. ‘Hunger has returned’: Covid piles further misery on Brazil's vulnerable.http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/22/brazil-rio-coronavirus-hunger-poverty July 22. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt S.A., LaMonto N.J., Mora D.C., Talton J.W., Laurienti P.J., Arcury T.A. COVID-19 pandemic among immigrant Latinx farmworker and non-farmworker families: A Rural–Urban comparison of economic, educational, healthcare, and immigration concerns. New Solutions. 2021;31(1):30–47. doi: 10.1177/1048291121992468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralli M., Cedola C., Urbano S., Morrone A., Ercoli L. Homeless persons and migrants in precarious housing conditions and COVID-19 pandemic: Peculiarities and prevention strategies. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2020;24(18):9765–9767. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202009_23071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J.D. The relevance of the ethics of vulnerability in bioethics. Les Ateliers de l’Éthique/the Ethics Forum. 2017;12(2–3):154–179. doi: 10.7202/1051280ar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin O., Salim H., Suprun E., Richards R., MacAskill S., Heilgeist S., Rutherford S., Stewart R.A., Beal C.D. Developing a preliminary causal loop diagram for understanding the wicked complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic. Systems. 2020;8(2):20. doi: 10.3390/systems8020020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanfelici M. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on marginal migrant populations in Italy. American Behavioral Scientist. 2021;65(10):1323–1341. doi: 10.1177/00027642211000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini R.A., Powell S.K., Frere J.J., Saali A., Krystal H.L., Kumar V., Katz C.L. Psychological distress in the face of a pandemic: An observational study characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on immigrant outpatient mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A., Basabose J.D., Brockett M., Browne D.T., Shamon S., Stephenson M. Family medicine with refugee newcomers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2021;34:S210–S216. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sözer H. Categories that blind us, categories that bind them: The deployment of vulnerability notion for Syrian refugees in Turkey. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2019 doi: 10.1093/jrs/fez020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiritus-Beerden E., Verelst A., Devlieger I., Langer Primdahl N., Botelho Guedes F., Chiarenza A., De Maesschalck S., Durbeej N., Garrido R., Gaspar de Matos M., Ioannidi E., Murphy R., Oulahal R., Osman F., Padilla B., Paloma V., Shehadeh A., Sturm G., van den Muijsenbergh M., Derluyn I. Mental health of refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of experienced discrimination and daily stressors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(12):6354. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens P., A.J., Dworkin A.G. The Palgrave handbook of race and ethnic inequalities in education. Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. Researching race and ethnic inequalities in education: Key findings and future directions; pp. 1237–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliacozzo S., Pisacane L., Kilkey M. The interplay between structural and systemic vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic: Migrant agricultural workers in informal settlements in Southern Italy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2021;47(9) doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1857230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet COVID-19 will not leave behind refugees and migrants. The Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurner S., Hanel R., Klimek P. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2018. Introduction to the theory of complex systems. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah A.A., Nawaz F., Chattoraj D. Locked up under lockdown: The COVID-19 pandemic and the migrant population. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2021;3(1):100126. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN Global Compact . 2020, April 29. COVID-19 and human rights: Protecting the most vulnerable. UN global Compact academy.https://unglobalcompact.org/academy/covid-19-and-human-rights-protecting-the-most-vulnerable [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck B.C. How useful is ‘Vulnerable’ as A concept? Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):1231–1234. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J., Stahl B., Salam A. Critical discourse analysis as a review methodology: An empirical example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2015;37 doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.03711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Tian C., Qin W. The impact of epidemic infectious diseases on the wellbeing of migrant workers: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2020;10(3) https://www.internationaljournalofwellbeing.org/index.php/ijow/article/view/1301 Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart G. The sexual abuse of people with learning difficulties: Do we need a social model approach to vulnerability? The Journal of Adult Protection. 2003;5(3):14–27. doi: 10.1108/14668203200300021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wodak R. 1st ed. Longman; London: 1996. Disorders of discourse. [Google Scholar]

- Zarowsky C., Haddad S., Nguyen V.-K. Beyond ‘vulnerable groups’: Contexts and dynamics of vulnerability. Global Health Promotion. 2013;20(1_suppl):3–9. doi: 10.1177/1757975912470062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.