Abstract

Traditional oncology treatment modalities are often associated with a poor therapeutic index. This has driven the development of new targeted treatment modalities, including several based on the conversion of optical light into heat energy (photothermal therapy, PTT) and sound waves (photoacoustic imaging, PA) that can be applied locally. These approaches are especially effective when combined with photoactive nanoparticles that preferentially accumulate in tissues of interest and thereby further increase spatiotemporal resolution. In this study, two clinically-used materials that have proven effective in both PTT and PA – indocyanine green and gold nanoparticles – were combined into a single nanoformulation. These particles, “ICG-AuNP clusters”, incorporated high concentrations of both moieties without the need for additional stabilizing or solubilizing reagents. The clusters demonstrated high theranostic efficacy both in vitro and in vivo, compared with ICG alone. Specifically, in an orthotopic mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer, ICG-AuNP clusters could be injected intravenously, imaged in the tumor by PA, and then combined with near-infrared laser irradiation to successfully thermally ablate tumors and prolong animal survival. Altogether, this novel nanomaterial demonstrates excellent therapeutic potential for integrated treatment and imaging.

Keywords: indocyanine green, gold nanoparticles, photoacoustic imaging, photothermal therapy, theranostic

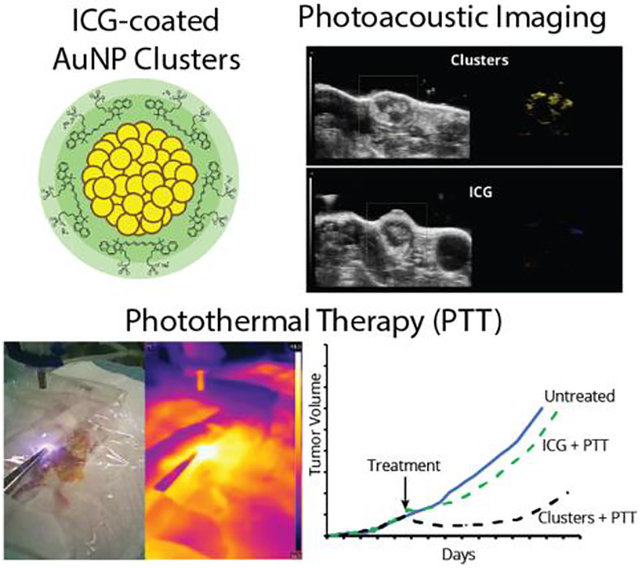

Graphical Abstract

ICG and hydrophobic gold nanoparticles are combined into a single nanoformulation without the need for additional carrier material. Nanoclusters displayed good long-term physiological clearance of gold and enabled photoacoustic imaging of tumors and photothermal therapy that improved animal survival in an aggressive murine breast cancer model.

1. Introduction

Radiation therapy has long represented a paradigm in the treatment of cancer, with multiple advantages including efficacy against many tumor types and localized delivery.[1–3] Traditional radiation therapy involves the use of high-energy ionizing radiation – typically photons or charged particles – that relies on the inherent absorptive properties of that tissue to deposit energy. However, this broad cytotoxicity may contribute to inadvertent damage of adjacent healthy cells, particularly tissue in the path of radiation. Ionizing radiation is also a critical component of computed tomography (CT) and other imaging modalities used to clinically visualize malignant tissue; though dosage is usually low, these procedures may themselves pose risks to normal biological tissue.[4]

A new class of therapies and diagnostics have emerged that harness lower-energy forms of radiation, including infrared and visible light.[5–9] While less harmful to tissues on their own, these can be applied in combination with localized exogenous agents that mediate and enhance tissue interactions, thereby achieving site-specific efficacy with reduced damage to off-target tissues. In particular, near infrared light (NIR, 650 – 1350 nm) is a highly attractive radiation source primarily due to its relatively deep tissue penetration – up to several centimeters – compared to lower-wavelength light.[10,11] NIR photomedicine has been broadly applied in cancer treatment and imaging through numerous modalities,[8] including: photodynamic therapy, or PDT (light excites a photoactive agent to a triplet excited state, which then directly or indirectly generates free radicals and/or reactive oxygen species); photothermal therapy, or PTT (absorbed energy is emitted as vibrational energy – i.e., heat); fluorescence imaging (energy is emitted radiatively as a photon); and photoacoustic imaging (energy is emitted as heat, which generates a detectable acoustic wave). Photoacoustic imaging has become increasingly popular due to its deep signal penetration (≤ 5–6 cm), high resolution (≥ 5μm), and decreasing instrument costs.[12–16] Furthermore, because the molecular contrast agents for photoacoustic imaging are optimized for non-radiative emission, many of these same materials can be utilized for photothermal therapy, allowing dual clinical functionality.[9] PTT has a potential advantage over photodynamic therapy, in that it does not require the presence of oxygen, the concentration of which may be limited in large solid tumors.[17]

To take advantage of photomedicine’s increased safety margin, it is necessary for a photoactive moiety to be localized to the tumor tissue; however, this can be difficult to achieve for many traditional small molecule agents. Nanoscale formulations may be particularly useful for overcoming these targeting limitations. Due to their unique physical, chemical, and biological properties, nanoparticles can: 1) deliver high volumes of cargo to regions of interest, 2) maintain cargo in a desired site at an optimal time period for clinical intervention, and 3) reduce cargo accumulation in off-target sites.[18] An excellent candidate for the photoactive moiety in the nanoformulation – with great potential in both PTT and photoacoustic imaging – is indocyanine green (ICG), which at present is the only FDA-approved near-infrared dye.[19,20] As a small molecule, ICG’s utility is limited because of its instability in aqueous solution – especially when combined with light, heat, or salts – as well as its rapid clearance from the bloodstream, which can prevent the high, localized concentrations desirable for intervention in tumors. While these shortcomings would likely improve in a nanoformulation, ICG can be difficult to load in large quantities due to its amphiphilicity and lack of easily-modifiable chemical groups.

Recently, we reported several novel fluorophore-based nanoparticle structures wherein a dye – ICG, protoporphyrin IX, or chlorin e6 – was combined with only one other common component: superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIOs).[21–23] In these three structures, the amphiphilic dye molecules were utilized as an outer coating to stabilize clusters of hydrophobic SPIO particles, thereby thermodynamically driving ICG to remain bound in large concentrations. The ICG-SPIO nanoclusters were successfully employed in image-guided surgery based on photoacoustic imaging (of ICG) and pre-surgical MR imaging (of SPIOs). However, in all of these studies, SPIOs were utilized for MR imaging and as a scaffold for the amphiphilic dye, but were not designed to contribute directly to tumor therapy.

With this in mind, we sought to further expand the utility of ICG clusters by creating an inherently theranostic nanoformulation for combined photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy, whereby both materials were capable of contributing to each modality. For this, we selected another material that has been proven dually efficacious in both photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging: gold nanoparticles (AuNPs).[5,13,16,24,25] Several groups have reported physiological studies of particles combining ICG and gold, but these particles have several key drawbacks. For example, they incorporated significant quantities of inert binding materials (serum albumin,[26,27] silica,[28–31] poly(styrene-alt-maleic anhydride),[32] polyethyleneimine,[32,33] chitosan[27,34], and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid[27]), thereby reducing the per-particle loading of functionally active ICG and Au. Also, almost all of these studies used large gold particles (15 – 150 nm), which are well-known to display protracted physiological elimination.[35,36] We have previously demonstrated the utility of using 2-nm dodecanethiol-coated AuNPs in micellar nanoformulations: they can be densely packed to provide high Au payloads with extremely low non-gold mass, while their small individual size facilitates long-term physiological clearance.[37,38] In the current study, ICG was successfully formulated at high concentrations into a stable nanoformulation with ultrasmall hydrophobic AuNPs. These dual-component nanoclusters show favorable long-term biological clearance, as well as great promise for both photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of ICG-AuNP Clusters

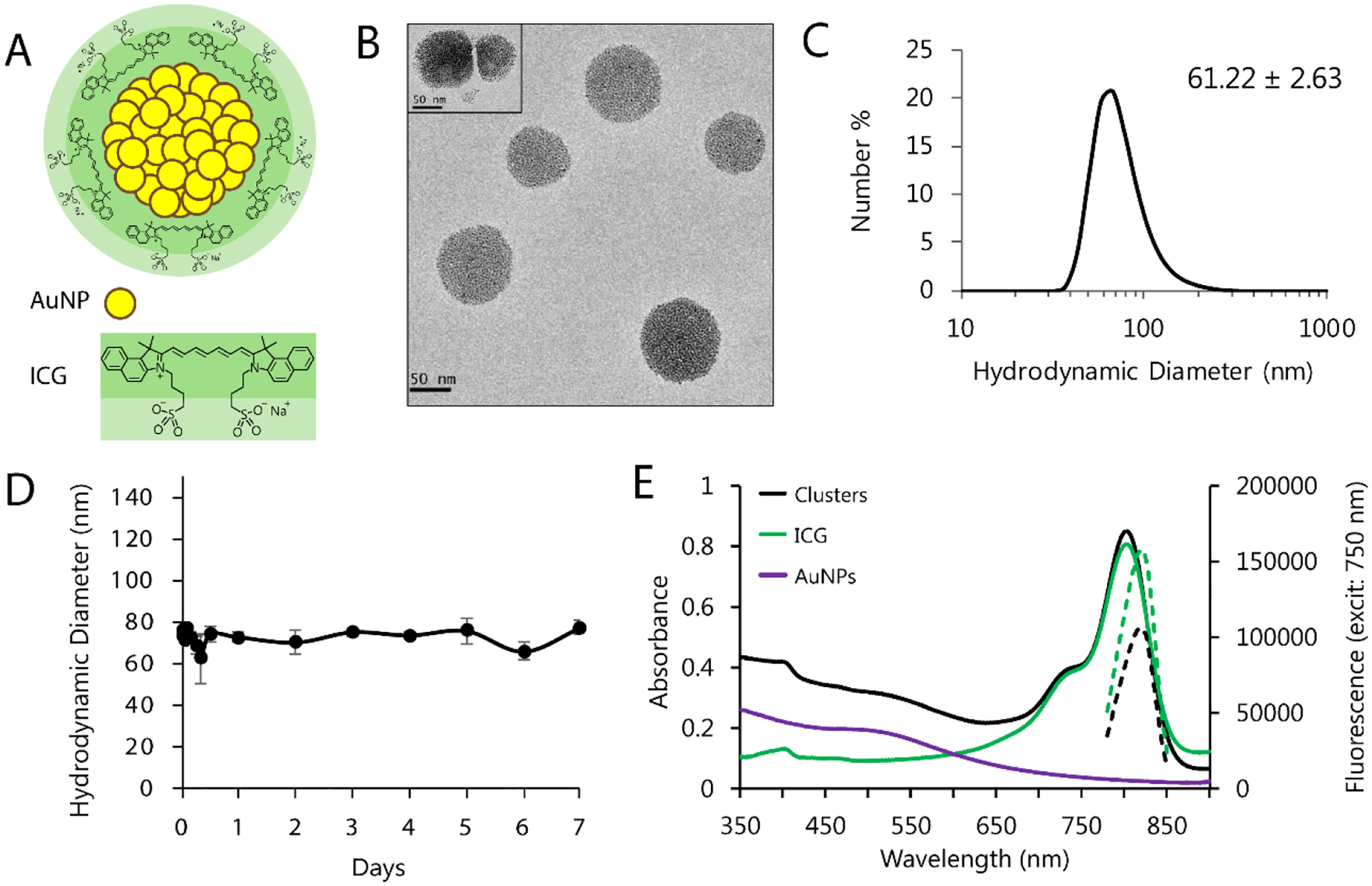

ICG and gold were formulated into a stable, water-soluble nanomaterial using a rapid and facile nanoemulsion methodology. We first synthesized ultrasmall hydrophobic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) consisting of 2-nm gold cores coated with dodecanethiol (Figure S1, Supporting Information).[39] Small clusters of AuNPs were then solubilized by using ICG as an amphiphilic coating (Figure 1A). To prepare these clusters, ICG was combined with AuNPs in organic solvent and then emulsified into water, driving self-assembly of the two materials into discrete spheroids (Figure 1B–C). TEM images confirmed the expected clusters of ultrasmall AuNPs. ICG is not visible in such images, preventing observation of ICG location; however, we consistently observed that clusters in close proximity display a thick “halo” that could be indicative of ICG presence on the surface (Figure 1B, inset). Clusters exhibited a favorable hydrodynamic size and narrow size distribution (61.22 ± 2.63 nm); this diameter stayed constant over time, suggesting that clusters remain stable in water without detectable aggregation (Figure 1D). Due to the inclusion of ICG, clusters were found to be highly negatively-charged, with a zeta potential of −26.1 ± 12.6.

Figure 1.

A) Schematic of ICG-AuNP clusters, consisting of 2-nm dodecanethiol-coated gold nanoparticles (AuNP) packed within the core and coated with a dense outer layer of indocyanine green (ICG). B) TEM images of clusters. C) DLS of clusters in water showing hydrodynamic diameter; the average hydrodynamic diameter was 61.22 ± 2.63 nm (standard deviation, n = 2 particle batches). D) Peak hydrodynamic diameter of clusters in solution (water, 4°C, dark) over the course of one week. n = 3 measurements, ± SEM. E) Absorbance (solid lines) and fluorescence (dashed lines) of clusters dissolved in serum vs. equivalent concentrations of free ICG (3 μg mL−1 ICG) or dodecanethiol AuNPs (20 μg mL−1 Au). Cluster absorbance maximum = 803 nm; fluorescence maximum = 820 nm.

We next sought to further understand the interaction between ICG and AuNPs within the cluster, and assess whether ICG might displace dodecanethiol on the AuNP surface. Knowing that ICG, but not dodecanethiol, is soluble in dimethylformamide, we dissolved ICG-AuNP clusters in this medium and centrifuged to separate out any insoluble material. The precipitate was found to be soluble only in highly nonpolar solvents such as toluene and the absorbance spectra matched that of AuNPs, but not ICG. In contrast, the absorbance spectra of the supernatant matched that of ICG, but not AuNPs. There was no mixing of spectral signals (Figure S2, Supporting Information). This suggests that ICG is not covalently associated with the AuNP surface, and cluster assembly is likely the result of noncovalent interactions such as hydrophobic self-assembly, with the amphiphilic ICG on the cluster surface.

The optical properties of the clusters was also examined in aqueous solutions. Interestingly, the peak associated with clustered AuNPs demonstrated only a very modest red-shift compared to the dispersed 2-nm AuNPs, despite the well-studied impact of AuNP aggregation on surface plasmon resonance.[40] To confirm this effect, we synthesized control AuNP clusters that are encapsulated with an amphiphilic polymer, poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL), instead of ICG.[37] These polymer-AuNP clusters, which shared a similar size and structure as ICG-AuNP clusters (Figure S1C, Supporting Information), displayed an equivalent absorbance peak, suggesting this is a shared feature of these nanostructures. When examining cluster optical properties, we also found that ICG demonstrated strong quenching when incorporated into this cluster formulation, as observed by a reduction in fluorescence compared to equivalent concentrations of free ICG (Figure 1E; Figure S2, Supporting Information). This likely results from a combination of mechanisms, including self-quenching of ICG as a result of its tight packing on the surface of the clusters, and quenching due to the close proximity of ICG to the AuNPs, as gold is known to be an extremely effective quencher.[41,42]

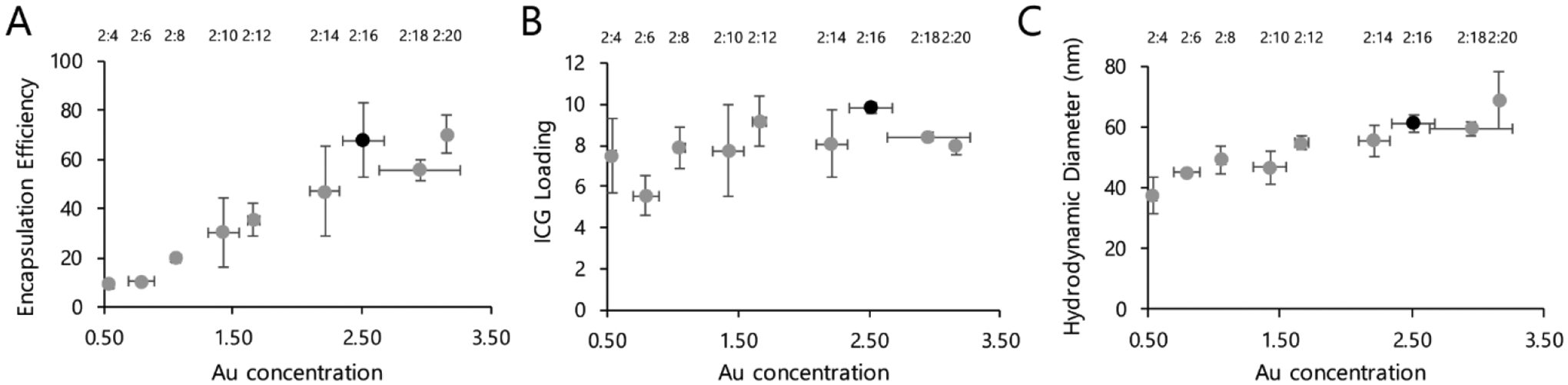

In order to optimize cluster composition and yield, we synthesized a number of different formulations of clusters by varying the relative amounts of ICG and AuNPs (Figure 2; Table S1, Supporting Information). As expected, increasing the concentration of AuNPs relative to ICG resulted in more of the reagent ICG being successfully incorporated within clusters, maxing out at approximately 70% ICG encapsulation efficiency. Within the column-purified clusters, the ratio of ICG to Au was quite consistent across all nanoformulations tested, with ICG mass approximately 5–10% compared to gold mass. We also observed that using a larger initial ratio of AuNPs caused a moderate increase in cluster size, despite the consistent proportions of ICG and Au. Ultimately, we determined that the optimal cluster composition consisted of 2:16 ICG:AuNP (w/w) loading; this yielded efficient incorporation of ICG relative to starting material, high loading of ICG relative to Au, and favorable hydrodynamic diameter.

Figure 2.

Multiple cluster formulations were synthesized by varying the ratio of ICG to AuNPs. ICG concentration was determined by absorbance, following dissolution in organic solvent; Au concentration was determined by ICP-OES. Black marker indicates the formulation selected for all other experiments. A) Encapsulation efficiency of ICG into particles, which was calculated by dividing the ICG:Au ratios of the reaction solutions after vs. before column purification (expressed as percentage). B) Loading efficiency of ICG within the purified particles, as calculated by the ICG concentration divided by Au concentration (expressed as percentage). C) Hydrodynamic diameter of the particles. n = 2 particle batches, ± SEM.

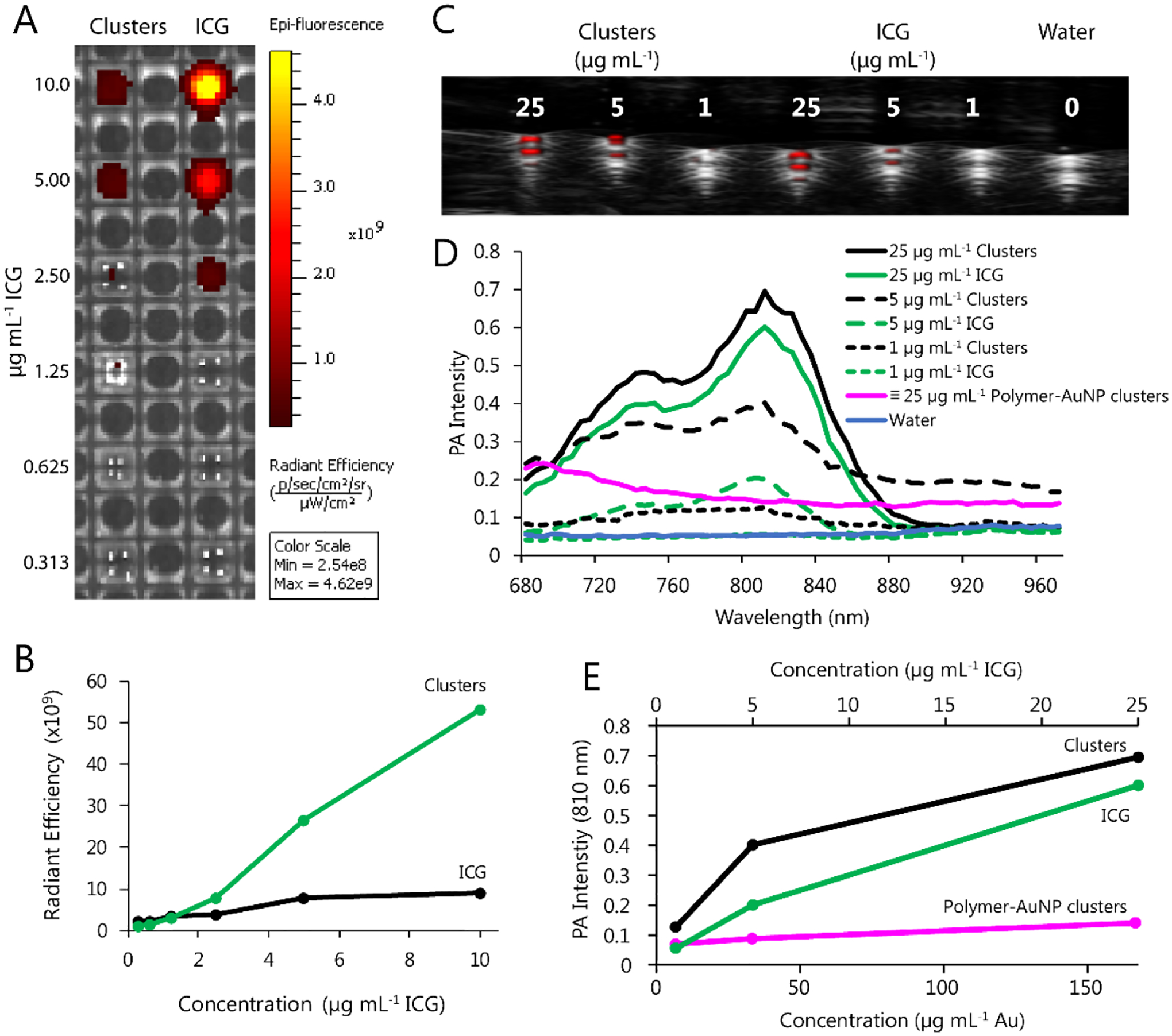

2.2. In Vitro Imaging of ICG-AuNP Clusters

Aqueous solutions of clusters and free ICG were prepared in a range of concentrations that were loaded simultaneously into imaging phantoms. We found that clusters displayed intensity-dependent signal for both fluorescence imaging and photoacoustic imaging (Figure 3). Notably, clusters demonstrated strong quenching of fluorescence signal compared to free ICG; in contrast, photoacoustic signal intensity was amplified in the nanoformulation, particularly at lower concentrations. These complimentary phenomena can likely be partly explained by the tight packing of ICG and Au within the cluster structure: close molecular proximity promotes collisional/self-quenching, decreasing the proportion of energy emitted radiatively (as fluorescence) and increasing nonradiative emission (heat, read as ultrasonic emissions).[42–44] We also collected photoacoustic spectra for polymer-AuNP clusters, which did not include ICG, knowing that many Au nanoformulations generate photoacoustic signals.[5,13,16,24] These spectra suggest that the polymer-AuNP cluster is only able to generate a modest photoacoustic signal intensity within the NIR range, with decreasing intensity at longer wavelengths. This corresponds with our data showing that ICG-AuNP clusters have similar PA spectra compared to free ICG, with a slight increase in signal due to the presence of the AuNPs.

Figure 3.

Phantom imaging of ICG-AuNP clusters in water vs. equivalent concentrations of free ICG and polymer-AuNP clusters. A) Fluorescence imaging (ex = 745, em = 820). B) Quantification of fluorescence signal intensity (radiant efficiency) as a function of ICG concentration. C) Photoacoustic imaging (PA gain 30–40 dB, priority 95%, distance 12 mm from the transducer; transducer axial resolution, 75 μm; broadband frequency, 13–24 MHz). D) Complete PA spectra at varying concentrations. ICG-AuNP clusters and free ICG are expressed as μg mL−1 ICG; polymer-AuNP clusters are shown at a gold dosage equivalent to that of the 25 μg mL−1 ICG-Au clusters (167 μg mL−1 Au). E) Quantification of PA signal intensity (810 nm) as a function of equivalent ICG-AuNP cluster, ICG, and polymer-AuNP cluster concentrations.

2.3. In Vitro Heating and ROS Generation of ICG-AuNP Clusters

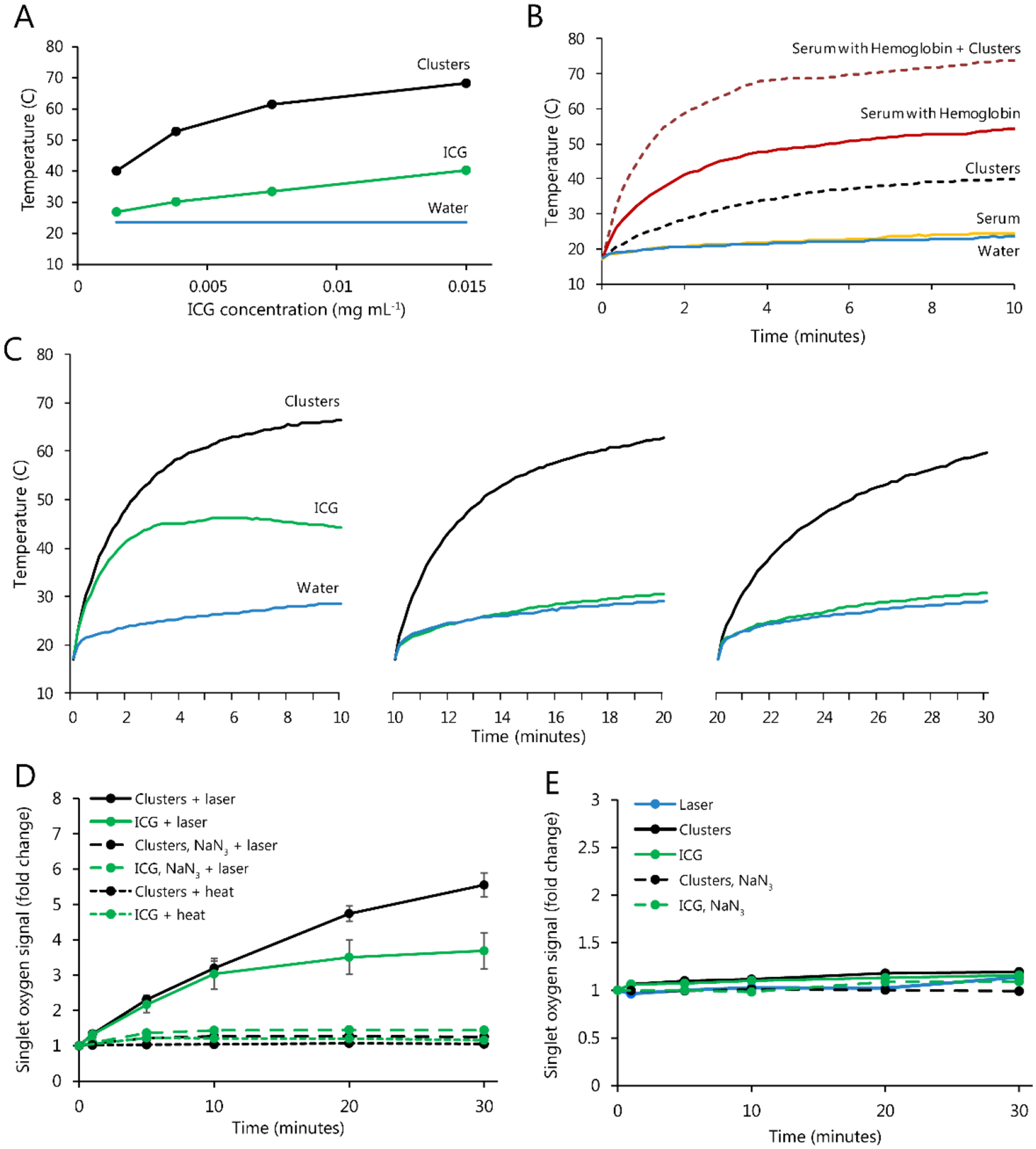

Next, we examined the ability of clusters to generate heat upon irradiation. Solutions of clusters in water and control solutions were treated with 808nm laser light (1.2 W power, 0.1 cm2 area), and temperature was recorded over time. Clusters were found to generate significant temperature increases, higher than that of free ICG at every concentration tested (Figure 4A). When solutions were irradiated in multiple successive rounds, free ICG showed rapid degradation of its heating capacity, while clusters showed repeated heating ability through multiple laser administrations (Figure 4C). Clusters were also dissolved in serum containing biologically-relevant concentrations of hemoglobin, to compare their heating capacity relative to biological chromophores (Figure 4B). Even at low cluster concentrations, clusters showed significant and additive heating compared to hemoglobin alone, suggesting an appropriate safety window could be attained in vivo.

Figure 4.

Solutions of ICG-AuNP clusters, free ICG, and various controls were prepared at room temperature and then irradiated at 808nm (1.2 W power, 0.1 cm2 area) continuously for 10–30 minutes. A) Solutions in water; final solution temperature is plotted. B) The temperature of water; fetal bovine serum; clusters (0.0015 mg mL−1 ICG) in water; hemoglobin (155 mg mL−1) in fetal bovine serum; and clusters and hemoglobin dissolved in serum at noted concentrations and heated for the indicated times. C) Solutions in water (0.015 mg mL−1 ICG), heated in multiple 10-minute increments and allowed to cool to room temperature between successive rounds. D) Clusters and free ICG (0.015 mg mL−1) were irradiated in the presence of Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green, which detects formation of reactive oxygen species. Controls included the following: samples containing sodium azide (10 mM), a known scavenger of singlet oxygen; and non-irradiated samples heated to equivalent temperatures by external heat application. E) Analogous studies were performed with laser irradiation alone and without irradiation.

ICG nanoformulations have been well studied both in photothermal therapy and in photodynamic therapy, with many reports of dual activity for a single particle.[26,27,32,34] To this end, ICG-AuNP clusters were also examined for their ability to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which was monitored using the fluorescent reporter dye Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG). Irradiated clusters demonstrated a strong time-dependent increase in SOSG fluorescence. As observed in thermal studies, clusters and free ICG showed similar activity during the initial moments of irradiation, but free ICG appeared to exhaust its capacity more quickly. Further experiments confirmed that the SOSG fluorescence signal was unchanged in the absence of irradiation, even when equivalent levels of heat were applied directly to the solution. Moreover, we found that the SOSG signal was strongly reduced in the presence of sodium azide (10 mM), which is a known scavenger of singlet oxygen. Altogether, this provides strong evidence that ICG-AuNP clusters can generate ROS and provide a combination of photodynamic and photothermal therapy.

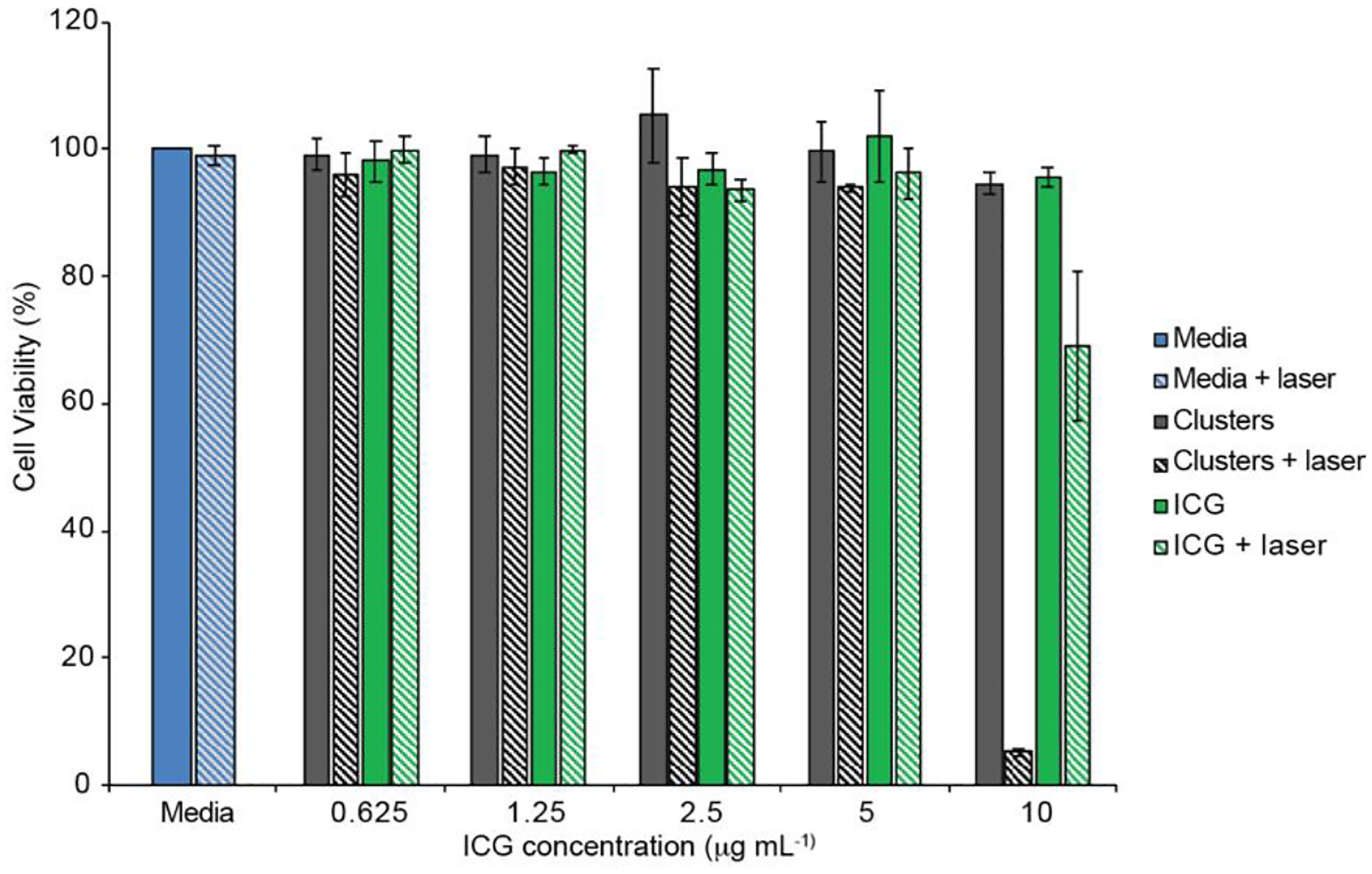

2.4. Cell Cytotoxicity of ICG-AuNP Clusters

After thorough physiochemical characterization of ICG-AuNP clusters in nonbiological conditions, clusters were next examined for cytotoxicity in cell culture. For these studies, we selected mouse 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells as a clinically relevant model of highly-aggressive, triple negative breast cancer.[45] Cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of clusters or free ICG, after which cellular viability was quantified by MTT assay (Figure 5). No toxicity was observed under standard dark conditions, as evidenced by >95% cell viability compared to media-only controls, even up to the highest concentration tested (10 μg mL−1 ICG). However, in parallel experiments, treatment with clusters was combined with laser irradiation (0.2 W cm−2, 7 minutes); under these conditions, cytotoxicity dropped sharply at a cluster concentration of 10 μg mL−1, resulting in nearly complete loss of cell viability (reduced to 5%). Furthermore, this effect did not extend to free ICG, which showed only a moderate decrease in viability (down to 69%). These results suggest that ICG-AuNP clusters would be both well-tolerated systemically and highly effective at killing laser-irradiated tissues.

Figure 5.

MTT assay of 4T1 cells incubated with ICG-AuNP clusters, free ICG, or standard media for 24 hours. A subset of cells was irradiated at 808 nm (0.2 W cm−2) for the first 7 minutes. n = 3 wells, ± SEM.

2.5. In Vivo Biodistribution and Toxicity of ICG-AuNP Clusters

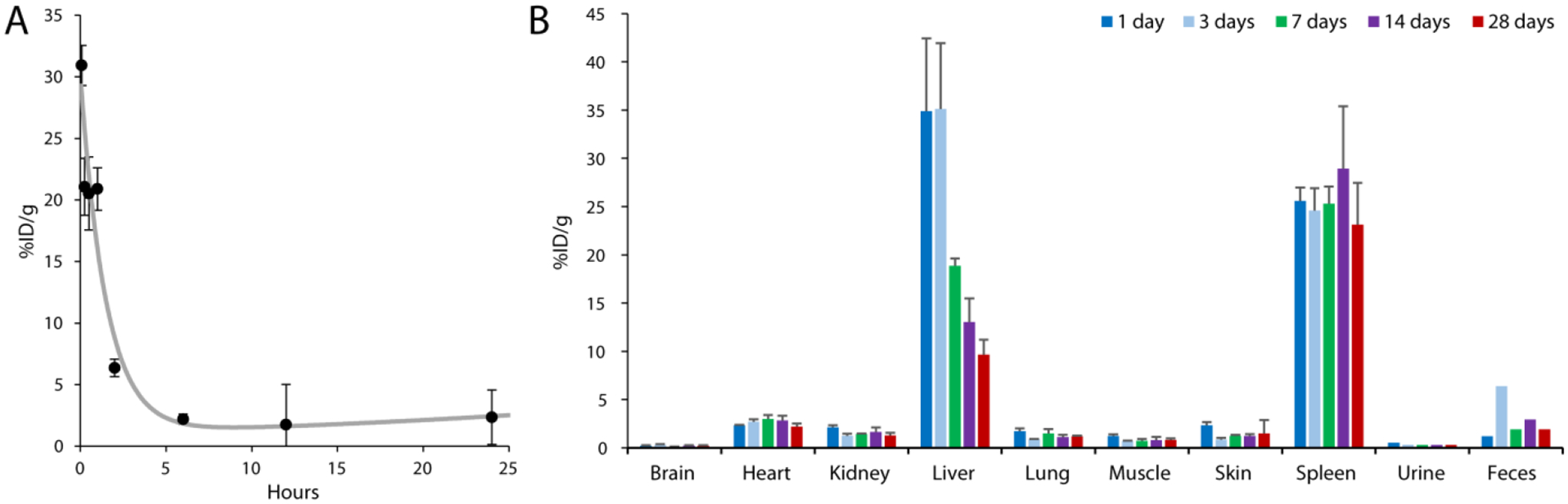

We next sought to understand how ICG-AuNP clusters would behave in vivo under non-treatment conditions. First, we administered clusters to healthy mice (30 mg kg−1 Au, 4.5 mg kg−1 ICG, I.V.) and measured gold content in the blood beginning at 5 minutes post-injection and lasting through the first 24 hours (Figure 6A). Clusters showed an approximate blood half-life of 61 minutes; for comparison, non-nanoparticle ICG has been previously reported to have a blood half-life of approximately 3 min.[46]

Figure 6.

ICG-AuNP clusters (30 mg kg−1 Au, 4.5 mg kg−1 ICG, I.V.) were administered to naïve C57BL/6 mice and biodistribution was determined in key tissue compartments by ICP-OES analysis of gold. Results expressed as percent injected dose per gram tissue. A) Blood pharmacokinetics for the first 24 hours post-injection. B) Tissue biodistribution for the first 28 days post-injection. n = 3 mice per timepoint, ± SEM; urine and feces represent one sample each, pooled from three mice.

Next, we examined long-term biodistribution by measuring gold content in tissues (Figure 6B). Clusters displayed a tissue biodistribution pattern that is typical for gold nanoformulations, with high accumulation in the liver (34.8 ± 13 %ID g−1, day 1) and spleen (25.6 ± 2.4 %ID g−1, day 1). Gold accumulation was low (< 3 %IG g−1) in all other analyzed tissues, including brain, heart, kidney, and lung, and remained low over the course of the four-week study. Although elimination from the spleen remained protracted, we found that the levels of gold in the liver decreased steadily, dropping more than 3.5-fold over time. These results can likely be attributed to the particle design -- specifically, the incorporated gold comprises clusters of discrete ultrasmall AuNPs rather than a large, solid core. Notably, during this time period, gold could be detected in the feces, suggesting that elimination occurred through the hepatobiliary system.

Throughout this study, we examined several broad markers of toxicity. Animals displayed no signs of illness, distress, or other behavioral alterations. Animal body weight showed a small, insignificant decrease in the first several days, likely due to the effects of injection and blood collection, but recovered fully over the course of four weeks (Figure S3A, Supporting Information). We also evaluated histology of key organs – liver, spleen, and kidney – but found no evidence of abnormal pathology (Figure S3B, Supporting Information).

Finally, we assessed the short-term accumulation of clusters in murine orthotopic tumors. For these and subsequent studies, 4T1 mammary tumors were implanted orthotopically in immune-competent mice. When tumors surpassed 50 mm3, mice were injected with ICG-AuNP clusters (20 mg kg−1 ICG, 133 mg kg−1 Au, I.V.). Eighteen hours later, we found 1.95 ± 0.4 %ID g−1 had accumulated in the tumor. This is consistent with previously reported results for nanoparticle tumor accumulation.[47]

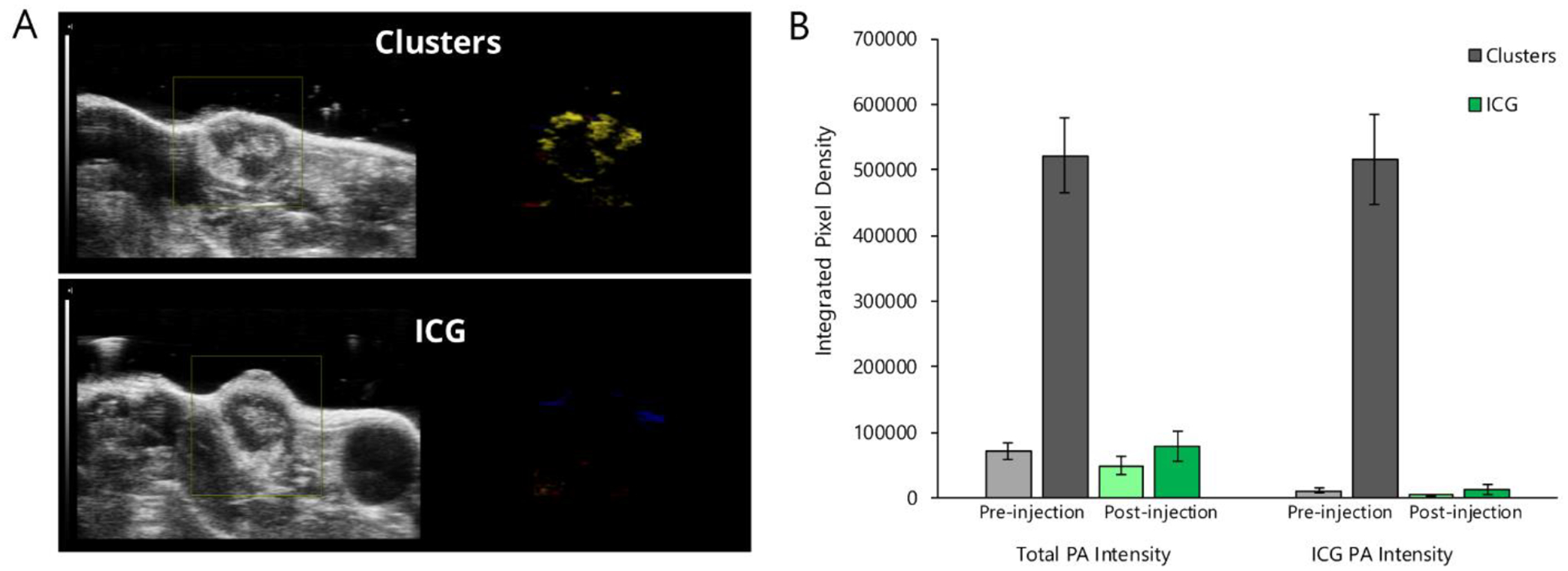

2.6. In vivo Imaging of ICG-AuNP Clusters

Having established in vivo tolerability of ICG-AuNP clusters, we next prepared to evaluate their diagnostic and therapeutic potential in a mouse orthotopic breast cancer model. We first sought to visualize tumors by photoacoustic imaging using accumulated ICG-AuNP clusters as a contrast agent. Tumor-bearing mice were imaged both at baseline and 18 hours after receiving either clusters or free ICG (20 mg kg−1 ICG, 133 mg kg−1 Au, I.V.) (Figure 7; Figure S4, Supporting Information). Cluster-treated mice demonstrated high signal intensity localized to the tumor; this signal was spectrally distinguishable from background photoacoustic signal contributed by oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin. In contrast, mice who received free ICG showed very little overall signal. These data correlate well with previous reports showing rapid clearance of ICG from the body,[46] and emphasize that nanoformulations of ICG broaden its tissue imaging applications.

Figure 7.

Photoacoustic imaging of 4T1 orthotopic mammary tumors in mice receiving either free ICG or ICG-AuNP clusters (20 mg kg−1 ICG, 133 mg kg−1 Au, I.V.). A) Representative images of mouse tumors at 18 hours post-injection. Left, ultrasound image; right, spectrally unmixed photoacoustic (color) image of ICG/cluster distribution (yellow) as well as oxygenated (red) and deoxygenated (blue) hemoglobin signal. B) Quantification of PA signal intensity before injection and 18 hours after injection; left bars show total PA intensity, right bars show intensity associated with spectrally unmixed ICG/cluster signal. n = 3 mice per group, ± SEM.

2.7. In vivo Heating of ICG-AuNP Clusters

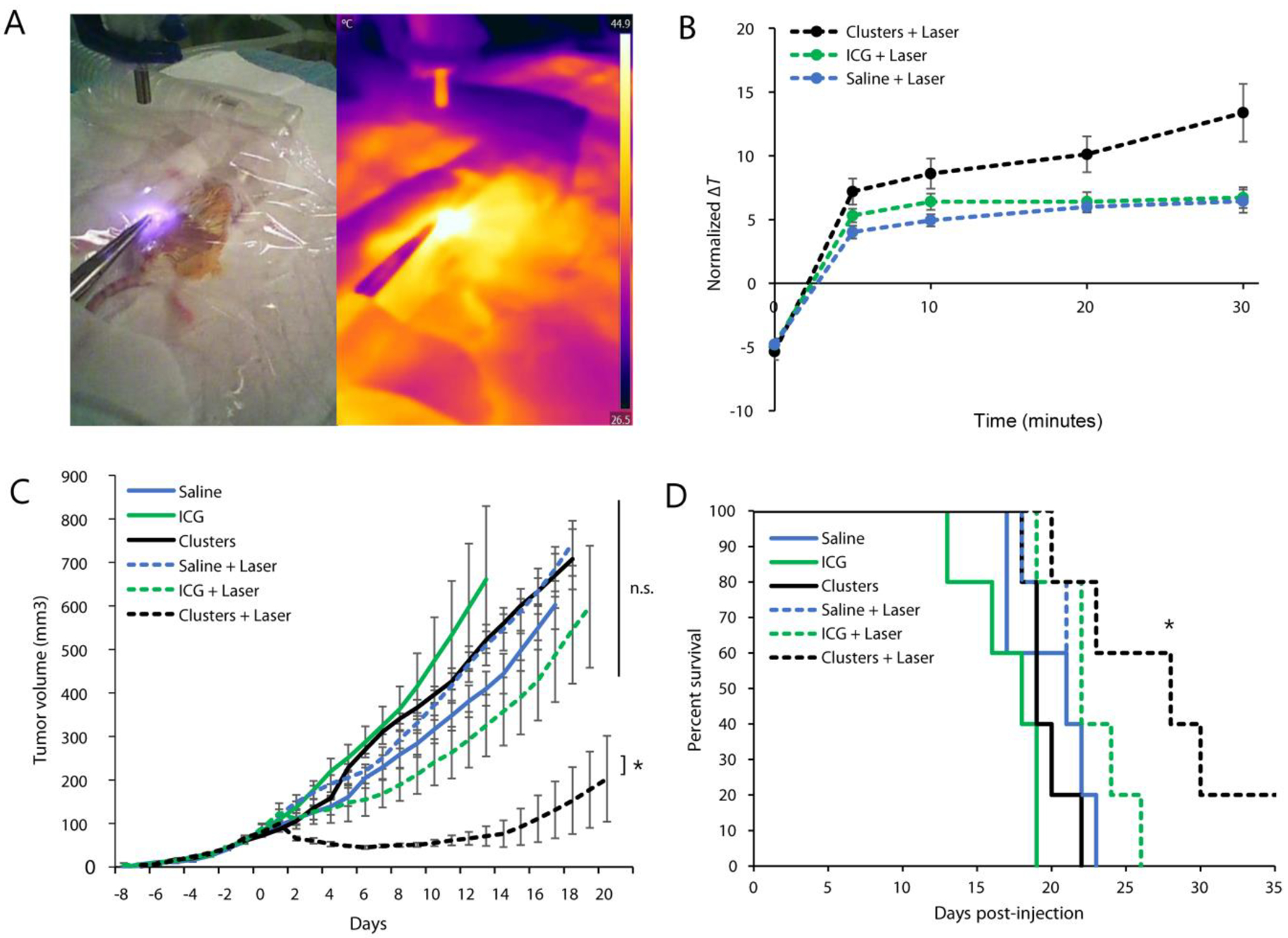

Finally, we evaluated antitumor efficacy in a photothermal therapy model. Mice with established 4T1 tumors (50 mm3) were treated with either saline, free ICG, or ICG-AuNP clusters (20 mg kg−1 ICG, I.V.); eighteen hours later, mammary tumors were exposed by skin incision and directly irradiated for 30 minutes (0.7 W cm−2, 1.13 cm2 laser area). During irradiation, we observed an increase in tumor temperature for all groups (Figure 8A–B). However, cluster-treated mice demonstrated the most profound heating effect, ultimately rising approximately 13 °C above body temperature (13.4 ± 2.3 °C). In contrast, tumor temperature rose only moderately in saline- and free ICG-treated animals (6.4 ± 0.9 °C and 6.7 ± 0.8 °C, respectively). Indeed, free ICG appeared to improve hyperthermia very modestly at early timepoints – though still less than ICG-AuNP clusters – but the effect was not sustained; this observation coheres well with our in vitro data showing a rapid plateau of heating capacity (Figure 4A–B).

Figure 8.

Mice bearing 4T1 orthotopic breast tumors were injected with saline, free ICG, or ICG-AuNP clusters (20 mg kg−1 ICG, 133 mg kg−1 Au, I.V.); eighteen hours later, a subset of mice also received subcutaneous laser irradiation (0.7 W cm−2, 1.13 cm2 laser area, 30 minutes). n = 5 mice per group, for a total of six groups. A) Representative thermographic image during treatment. B) Quantification of thermal imaging data over time, expressed as the difference between tumor temperature and animal body temperatures (average temperatures in fixed-size regions of interest). C) Tumor growth curves, averaged among groups; day −1 = injection, day 0 = laser treatment or no treatment. D) Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating animal survival. Data shown ± SEM; * = p < 0.05; n.s. = no statistical significance.

Mammalian cell death typically occurs at temperatures > 42–44 °C, though this effect is contingent on duration of heating as well as other factors such as cell type.[48] We observed that cluster-treated tumors surpassed 43 °C within 5 minutes of heating, reaching an ultimate recorded temperature of 52.3 ± 2.3 °C by 30 minutes (Figure S5, Supporting Information). This was a marked improvement over both control groups, which required more than 10 minutes to exceed 42 °C and which attained significantly lower final temperatures (free ICG: 45.6 ± 1.4; saline: 43.6 ± 1.2 °C). It is important to note that tumor hyperthermia was observed using an infrared thermographic camera, which detects surface temperature of tissues but cannot fully characterize the thermal environment within the tumor.

We next tracked long-term tumor growth in these photothermally-treated mice, as well as in control mice receiving drugs or saline alone (Figure 8C; Figure S6, Supporting Information). We observed statistically significant tumor shrinkage in mice that received the therapeutic combination of ICG-AuNP clusters with laser irradiation. This response was robust: average tumor size regressed below pre-treatment volume within two days of therapy, continued to drop until Day 6, and remained below the initial volume for a total of 11 days. Only one other experimental group displayed regression – those receiving free ICG and laser therapy together – but this decrease was brief (one day) and modest (did not reach pre-therapy size). ICG-mediated PTT was not significantly more effective than controls at any time. In contrast, PTT with ICG-AuNP clusters showed significant improvement over PTT with ICG (p < 0.05, day 6 onward) as well as PTT-alone, clusters-alone, ICG-alone, or no treatment (p < 0.05, day 2 onward).

When comparing all treatment groups to the control (saline with no PTT), we found a significant improvement in animal survival for mice receiving clusters and laser irradiation (p = 0.032); no other group showed statistical significance (Figure 8D). Notably, two out of five mice that received cluster-mediated PTT displayed complete remission of the primary tumor (Figure S6B, Supporting Information). One of these mice died on Day 22, potentially of a tumor metastasis, which is common for this model[45] and which was supported by an observation of 15% body weight increase, suggesting ascites; however, the other mouse survived until termination of the study on Day 60, indicating full disease remission.

3. Conclusion

We set out to create a nanoformulation incorporating two common and well-characterized materials: indocyanine green, a clinically-approved dye, and gold nanoparticles, which are also utilized in ongoing clinical trials. We found that these two materials formed a stable nanocluster structure – despite the absence of additional binding or solubilization reagents – and demonstrated excellent in vitro and in vivo biological interactions, including low toxicity, effective tumor localization, and good excretion over time. Knowing that both ICG and AuNPs are highly effective in photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy, we set out to characterize ICG-AuNP clusters in these modalities. Both in vitro and in vivo data indicated that the nanoparticles are potent and specific imaging reagents, and are highly effective at heat production. We found that mice treated with clusters and laser irradiation – but not those with free ICG and laser – could exhibit severe tumor cytotoxicity in a triple-negative orthotopic breast cancer model; this included 40% complete remission of the primary tumor and 20% complete remission of disease. Altogether, these ICG-AuNP clusters represent a promising new nanomaterial for cancer diagnosis and therapy.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

Indocyanine green, gold (III) chloride trihydrate, tetraoctylammonium bromide, 1-dodecanethiol, sodium borohydride, Sepharose® CL-4B, and sodium azide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG4k-PCL3k) was purchased from Polymer Source (Quebec, Canada). Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green Reagent, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Trypsin-EDTA, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), and penicillin-streptomycin solution were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Gibco; Waltham, MA). MTT assay kit was purchased from Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany).

Synthesis of 2-nm hydrophobic gold nanoparticles:

Dodecanethiol-coated gold nanoparticles were synthesized according to a protocol modified from Brust et al.,[39] as previously described.[37,38,49] A stock solution of gold (III) chloride trihydrate (1 g mL−1) was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 minutes to eliminate seeds, and 306 μL of the purified solution was diluted into 30 mL water to yield a 30 mM solution. In parallel, a 50 mM solution of tetraoctylammonium bromide was prepared by dissolving 2.19 g in 80 mL toluene. These two solutions were combined in an acid-washed flask and stirred vigorously, and 201 μL of 1-dodecanethiol was added. Finally, a 400 mM solution of sodium borohydride was also prepared by dissolving 0.378 g in 25 mL water. This solution was slowly and continuously pipetted into the gold mixture over the course of 15 minutes, and the resultant mixture was allowed to stir for 3 hours. The organic phase was collected and washed as follows: the toluene solution was first diluted in a 6.5-fold excess (v/v) of 95% ethanol, kept at −20°C overnight, centrifuged to collect the precipitated nanoparticles, and resuspended in a minimal volume of toluene. After a total of two such wash cycles, the nanoparticle solution was transferred into pre-weighed microcentrifuge tubes and the solvent was removed using a centrifugal evaporator (CentriVap, Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, MO).

Synthesis of ICG-AuNP clusters:

Dodecanethiol-coated gold nanoparticles were dissolved in toluene at a concentration of 40 mg mL−1 (based on dry particle mass). Meanwhile, a second solution was prepared containing indocyanine green (ICG) dissolved in dimethylformamide (100 mg mL−1); 20 μL of the ICG solution was then diluted into a mixture of dimethylformamide and toluene (30 μL and 60 μL, respectively). The diluted ICG was then combined with the primary gold nanoparticle solution (400 μL for most studies, or 50–500 μL for a subset of studies). The resulting mixture was pipetted into a glass vial containing 4 mL of water, and the sample was sonicated until a homogeneous colloid was observed. To remove organic solvents, the emulsion was allowed to stand overnight to evaporate toluene, then dialyzed in pure water to remove dimethylformamide. For studies requiring the precise determination of bound and unbound ICG, nanoclusters were further purified by passing through a Sepharose® CL-4B column (1.5 × 12 cm), collected as a dark brown band that was visually distinct from green ICG; in all other experiments, including cell and animal functional studies, clusters were not purified by column. Finally, clusters were concentrated using a centrifugal evaporator, then centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 minutes to remove large aggregates, and generally stored at a concentration of 3–4 mg mL−1 for a period of several weeks.

Synthesis of polymeric-AuNP clusters:

As experimental controls, AuNP clusters were encapsulated within a polymeric micelle, according to a protocol modified from Al Zaki et al.[35] Briefly, dodecanethiol-coated gold nanoparticles were dissolved in toluene at a concentration of 17.5 mg mL−1 (based on dry particle mass). 200 μL of this solution was combined with 3.5 mg of poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG4k-PCL3k) and sonicated thoroughly to combine. The resulting solution was pipetted into a glass vial containing 4 mL of water, and the sample was sonicated until a homogenous colloid was observed. To remove organic solvents, the emulsion was allowed to stand overnight to evaporate toluene. Clusters were centrifuged once at 400 × g for 10 minutes to remove large aggregates, and then the supernatant was centrifuged twice at 3100 × g for 30 minutes to sediment desired micelles.

Physiochemical characterization:

Nanoparticles (including dodecanethiol-coated gold nanoparticles, ICG-AuNP clusters, and polymeric-AuNP clusters) were characterized by a variety of physiochemical techniques. Gold particles were visualized using transition electron microscopy (Tecnai T12, FEI, Hillsboro, OR) to determine core diameter. Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of clusters were also examined using dynamic and electrophoretic light scattering, respectively (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom); all DLS data was expressed by particle number. ICG-AuNP clusters, free ICG, and dodecanethiol-coated AuNPs were also dissolved in water, dimethylformamide, fetal bovine serum, and/or toluene to capture their absorbance spectra (Varian-Cary 100 Bio spectrophotometer, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and fluorescence spectra (FluoroMax-3 spectrofluorimeter, Horiba Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ).

To determine the composition of ICG-AuNP clusters, each constituent was examined as follows. ICG concentration was determined by dissolving clusters in dimethylformamide (> 95% v/v) and comparing absorbance at ʎ = 792 nm with a standard curve for ICG. Gold concentration was determined using inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; Spectro Genesis, Spectro Analytical Instruments, Kieve, Germany). Briefly, aqueous solutions of clusters (20–200 μL) were placed in round-bottomed glass tubes with polytetrafluoroethylene-coated caps. To this was added up to 300 μL of aqua regia (e.g., 75 μL nitric acid plus 225 μL hydrochloric acid), and tubes were capped and allowed to stand at room temperature for several hours. Finally, solutions were diluted up to a standard volume and then spectrometrically analyzed. ICG and Au concentrations in purified clusters were then analyzed using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In vitro imaging:

Varying concentrations of ICG-AuNP clusters, ICG, and/or polymer-AuNP clusters were dissolved in water and then imaged using a phantom. In one study, solutions (50 μl each) were added to a 384-well plate and then examined by fluorescence imaging (IVIS Spectrum In Vivo System, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). IVIS parameters: excitation, 745 nm; emission, 820 nm; lamp level, high; exposure time, 0.5 seconds; binning, (M)8; f, 2.

In a separate study, solutions were placed into polyethylene tubing (0.5-mm diameter) submerged in water at a depth of 1–2 cm, and were examined by photoacoustic imaging (Vevo Lazr, VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). The LZ250 transducer was utilized (axial resolution, 75 μm; broadband frequency, 13–24 MHz). Images were acquired with the following settings: PA gain 30–40 dB, priority 95%, and distance 12 mm from the transducer. ICG-AuNP clusters and free ICG were examined within a single imaging session at 30 dB, allowing direct comparison of signal intensities.

In vitro heating:

Solutions of ICG-AuNP clusters, along with various controls, were treated with laser irradiation to induce heating. One milliliter of prepared solution was added to a 2-mL microcentrifuge tube, and a fiber optic thermometer (Nomad, Qualitrol-Neoptix, Fairport, NY) was inserted 4 mm below the liquid surface. Solutions were then irradiated with an 808-nm laser (OEM Laser Systems, Midvale, UT) at 1.2 W power (0.1 cm2 area). Irradiation continued for a period of 10 minutes, during which temperature was recorded every 10 seconds. In a subset of experiments, solutions were first irradiated for 10 minutes as described, then freely allowed to cool to their original pre-irradiation temperature; immediately after reaching this threshold, irradiation was repeated for two additional 10-minute cycles with cooling between. All experiments were performed at room temperature and with ambient light.

In vitro ROS generation:

ICG-AuNP clusters and various controls were examined for their ability to generate reactive oxygen species, using the reporter reagent Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green. SOSG-containing solutions (2.5 mL, 10 μM SOSG) were added to a quartz cuvette and mixed continuously by magnetic stirrer for 30 minutes. Aliquots (60 μL) were withdrawn at each of the following timepoints: 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes. Samples were then diluted 20-fold in water, and fluorescence was read by fluorimeter (ex = 488 nm; em = 523 nm) and normalized to the 0-minute reading. Solutions of ICG-AuNP clusters and free ICG (0.015 mg mL−1) were tested with or without sodium azide (10 mM). Samples were either kept in the dark or were irradiated continuously for 30 minutes (808 nm; 1.2 W power, 0.1 cm2 area). Irradiated samples of clusters and ICG also had surface temperature monitored using a FLIR ONE thermal imaging camera (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR); based on this data, a subset of samples were heated with equivalent temperature and timing under dark conditions (heat generated by Varian-Cary 100 Bio spectrophotometer, thermal accessory). Sample conditions generating greater than 1.5-fold change in SOSG fluorescence were performed in triplicate; all others were performed as single assays.

Cell culture:

Mouse 4T1 breast cancer cells (ATCC, Rockville, MD) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Cell viability by MTT assay:

To determine cytotoxicity of ICG-AuNP clusters, 4T1 mouse breast cancer cells were seeded in 96-well plates (white with clear, flat bottom) at a density of approximately 1.0 × 104 per well. Cells were allowed to incubate overnight, and then media was carefully removed from individual wells and replaced with fresh media containing nanoclusters or free ICG at various concentrations (n = 3 wells per condition). Plates were then incubated for 24 hours. Finally, media was removed and cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline, then given fresh media and subjected to a standard MTT assay. Results were expressed as % Cell Viability by comparing to the average absorbance value (λ = 590) of cells treated with media alone (n = 3 wells per plate used).

Nanocluster cytotoxicity was also examined in combination with laser irradiation. In these experiments, to ensure isolation of environmental conditions, cells were plated with two empty wells between them. The following day, plates were removed from incubators and placed on a 37°C warming surface to maintain temperature. Media was exchanged for fresh 37°C media containing nanoclusters or free ICG at various concentrations (n = 3 wells per condition). Immediately after addition, wells were irradiated with an 808-nm laser (0.2 W cm−2; 1.13 cm2 area) for a total of 7 minutes (84 J cm−2). Plates were returned to the incubator for 24 hours, after which they were washed and analyzed by MTT as described. Results were expressed as % Cell Viability by comparing to the average absorbance value (λ = 590) of cells treated with standard media under dark conditions (n = 3 wells per plate used).

Animal and tumor models:

Female mice (C57BL/6 or BALB/c), aged approximately 6–10 weeks, were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All animal studies were conducted with approval by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, in accordance with AAALAC guidelines and accreditation. Mice were fed standard chow ad libitum unless otherwise noted.

In a subset of studies, BALB/c mice were inoculated with 4T1 mouse breast cancer cells (2 × 106 cells per mouse, 50–80 μL total volume) injected orthotopically into the fourth abdominal mammary pad. At the time of tumor inoculation, abdominal hair was removed by application of depilatory cream; all tumor-bearing mice were also switched to a low-fluorescence diet (Teklad global 18% rodent diet 2918, Envigo, Madison, WI) to avoid interference with subsequent imaging studies. Tumor size was established by first measuring two axes (length and width) with digital calipers, and then estimating tumor volume using the following equation:

| (3) |

Biodistribution and toxicity in tissues:

C57BL/6 mice were injected I.V. (retro-orbitally) with clusters at a dose of 30 mg Au (approximately 4.5 mg ICG) per kg body weight (n = 15 mice total). Blood samples (3–20 μL each) were collected from the tail vein at the following timepoints post-injection: 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, 6 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours. These samples were collected from a total of three mice per timepoint, such that all mice received either one or two blood collections, and all groups were randomized with regards to subsequent study arm assignment. Blood samples were pipetted directly into round-bottomed glass tubes and stored at room temperature. Finally, samples were processed and analyzed for gold content using ICP-OES as previously described, using up to 1000 μL of aqua regia (e.g., 250 μL nitric acid plus 750 μL hydrochloric acid). For normalization purposes, blood samples were considered to be 1 μL = 1 mg. Half-life was determined by fitting a double exponential decay curve to the data using MATLAB software (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

These same mice were sacrificed at the following timepoints post-injection (n = 3 per group): 1 day, 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, and 28 days. Urine and feces samples were also collected at these timepoints from lightly-restrained mice, and were pooled from multiple mice within each group. At sacrifice, mice were first anesthetized with isoflurane (3%, 2 L min−1 O2; isoflurane precision vaporizer, VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA), exsanguinated via cardiac puncture, then euthanized by cervical dislocation. The following organs were then extracted (intact whole organs, unless otherwise noted): brain, heart, kidneys, liver (approximately 290 mg of right medial lobe), lung, muscle (gastrocnemius), skin (approximately 80 mg from femoral region with hair removed), spleen. Tissues were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline after extraction, frozen until ready for analysis, and then examined for gold content using ICP-OES. Briefly, collected tissues were weighed and then transferred into round-bottomed glass tubes with polytetrafluoroethylene-coated caps. To this was added up to 1000 μL of aqua regia (e.g., 250 μL nitric acid plus 750 μL hydrochloric acid). Tubes were lightly capped and allowed to stand at room temperature overnight. Solutions were diluted up to a standard volume, then passed through 0.2 μm filters to remove any indigestible material. Finally, samples were spectrometrically analyzed. For normalization purposes, urine samples were considered to be 1 μL = 1 mg.

To monitor animal toxicity, three of these mice (those ultimately sacrificed at 28 days) had their body weights periodically recorded. Also, for mice sacrificed between 1 day and 2 weeks, small samples of harvested tissue were analyzed for histology. The following organ samples were collected: kidney (n = 3 per timepoint), liver (n = 3 per timepoint), and spleen (n = 2 per timepoint). Tissue was fixed in formalin for 24–48 hours. Samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E by the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders Histology Core (P30-AR069619). Slides were imaged using an EVOS FL Auto Imaging System (Life Technologies) at 20x objective, and tissue was examined for markers of pathology including infiltrating immune cells, abnormal and multiple nuclei, apoptotic or necrotic events, and disruption of tissue architecture.

In a separate study, BALB/c mice were implanted with orthotopic mammary tumors as described (n = 5 mice). When tumor size surpassed 50 cm3, mice were injected I.V. (via tail vein) with clusters at a dose of 20 mg ICG (approximately 133 mg Au) per kg body weight. Eighteen hours after injection, tumor size was recorded again and mice were sacrificed as described. Tumors were extracted intact, frozen until further analysis, and finally examined for gold content using ICO-OES.

In vivo imaging:

BALB/c mice were implanted with orthotopic mammary tumors as described. When tumor size surpassed 50 cm3, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.8 – 3%, 2 L min−1 O2) and imaged by photoacoustic imaging as described. On the same day, mice were injected I.V. (via tail vein) with clusters at a dose of 20 mg ICG (approximately 133 mg Au) per kg body weight; control mice were injected with an equivalent dose of free ICG (n = 3 mice per group, two groups). Eighteen hours after injection, mice were imaged by photoacoustic imaging as described. Spectral unmixing techniques were used to separate the contrast agent signals from background signals (i.e., oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin) based on their PA spectra.

In vivo heating:

BALB/c mice were implanted with orthotopic mammary tumors as described. When tumor size surpassed 50 cm3, mice were injected I.V. (via tail vein) with ICG-AuNP clusters at a dose of 20 mg ICG (approximately 133 mg Au) per kg body weight. Control mice were injected with an equivalent dose of free ICG or with 0.9% saline (n = 5 mice per group, three groups).

Eighteen hours after injection, mice were subjected to subcutaneous photothermal therapy. Briefly, mice were given preoperative analgesia (0.1 mg kg−1 buprenorphine, S.Q.) and anesthetized with isoflurane (1.8 – 3%, 2 L min−1 O2); body temperature was maintained thereafter using a recirculating water pad (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). The abdominal skin was sterilized (povidone-iodine and 70% ethanol) and a sterile drape was placed. Next, a curved incision was made medial to the tumor, and hemostat clamps were used to draw back the skin and expose the underside of the tumor. Tumors were irradiated at 808 nm for 30 minutes (0.7 W cm−2; 1.13 cm2 laser area, which fully covered all tumors; 1260 J cm−2). After the completion of illumination, skin was sutured with nylon and mice were hydrated with subcutaneous saline. For the subsequent 72 hours, mice were monitored at least daily for wound condition and signs of distress, and were given additional buprenorphine (0.1 mg kg−1) for the first 24 hours and as needed.

Immediately before and during the described laser therapy, tumor and abdomen surface temperature were monitored using a FLIR ONE thermal imaging camera (FLIR Systems, Wilsonville, OR) at the following timepoints: pre-treatment, 5 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 30 min. Infrared images were later analyzed for 1) maximum temperature in the tumor, and 2) temperature averaged over each of two 1.3 cm2 circular regions of interest, one centered on the tumor and one on an area of the shaved abdomen at least 8 mm away (thus approximating overall animal body temperature).

In addition to three groups of laser-treated mice, an additional three groups of mice (n = 5 mice per group) with size-matched tumors were injected with equivalent doses of either ICG-AuNP clusters, free ICG, or saline. These mice received no additional therapeutic interventions.

Tumor volume was monitored in all six groups and calculated as described, beginning a minimum of five days after tumor cell implantation and continuing until animal death. Criteria for animal sacrifice included any of the following: tumor length surpassed 15 mm; ulceration of the skin surpassed 7.5 mm; or animal gait was considerably impacted. Animals were also monitored for weight change and body conditioning score, changes in eating and elimination patterns, as well as other markers of health and behavior.

Statistical analysis:

Tumor growth curves were analyzed by type II ANOVA and pairwise comparisons of tumor growth slopes, calculated using TumGrowth open-access software (https://github.com/kroemerlab),[50] as well as by t-test of daily tumor volume means, calculated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Co, Redmont, WA, USA). For survival analysis, log-rank test was performed using MedCalc Software (Medcalc, Mariakerke, Belgium),[51] comparing all groups to saline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA181429, AT; R01 CA236362, TB; and P01 CA087971, TB) and the University Research Foundation Award (AT). The authors would like to acknowledge Sergei Vinogradov for technical assistance with laser setup.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Higbee-Dempsey, Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics Graduate Group, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Ahmad Amirshaghaghi, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Matthew J. Case, College of Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425, USA Department of Radiation Oncology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Joann Miller, Department of Radiation Oncology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Theresa M. Busch, Department of Radiation Oncology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Andrew Tsourkas, Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

References

- [1].Baskar R, Lee KA, Yeo R, Yeoh K-W, Int J Med Sci 2012, 9, 193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen HHW, Kuo MT, Oncotarget 2017, 8, 62742–62758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang H, Mu X, He H, Zhang X-D, Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2018, 39, 24–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Power SP, Moloney F, Twomey M, James K, O’Connor OJ, Maher MM, World J Radiol 2016, 8, 902–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pekkanen AM, DeWitt MR, Rylander MN, J Biomed Nanotechnol 2014, 10, 1677–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Deng K, Li C, Huang S, Xing B, Jin D, Zeng Q, Hou Z, Lin J, Small 2017, 13, 1702299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vats M, Mishra SK, Baghini MS, Chauhan DS, Srivastava R, De A, Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, DOI 10.3390/ijms18050924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen H, Zhao Y, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 21021–21034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liu Y, Bhattarai P, Dai Z, Chen X, Chemical Society Reviews 2019, 48, 2053–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Song J, Qu J, Swihart MT, Prasad PN, Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2016, 12, 771–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ge X, Fu Q, Bai L, Chen B, Wang R, Gao S, Song J, New J. Chem 2019, 43, 8835–8851. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Su JL, Wang B, Wilson KE, Bayer CL, Chen Y-S, Kim S, Homan KA, Emelianov SY, Expert Opin Med Diagn 2010, 4, 497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li W, Chen X, Nanomedicine (Lond) 2015, 10, 299–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Moore C, Jokerst JV, Theranostics 2019, 9, 1550–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Erfanzadeh M, Zhu Q, Photoacoustics 2019, 14, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fu Q, Zhu R, Song J, Yang H, Chen X, Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1805875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dang J, He H, Chen D, Yin L, Biomater. Sci 2017, 5, 1500–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jin S-E, Jin H-E, Hong S-S, Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, DOI 10.1155/2014/814208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sheng Z, Hu D, Xue M, He M, Gong P, Cai L, Nano-Micro Lett 2013, 5, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nagaya T, Nakamura YA, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H, Front Oncol 2017, 7, DOI 10.3389/fonc.2017.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thawani JP, Amirshaghaghi A, Yan L, Stein JM, Liu J, Tsourkas A, Small 2017, 13, 1701300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yan L, Amirshaghaghi A, Huang D, Miller J, Stein JM, Busch TM, Cheng Z, Tsourkas A, Adv Funct Mater 2018, 28, DOI 10.1002/adfm.201707030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Amirshaghaghi A, Yan L, Miller J, Daniel Y, Stein JM, Busch TM, Cheng Z, Tsourkas A, Sci Rep 2019, 9, 2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Huang X, El-Sayed MA, Journal of Advanced Research 2010, 1, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cooper DR, Bekah D, Nadeau JL, Front. Chem 2014, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cui H, Hu D, Zhang J, Gao G, Chen Z, Li W, Gong P, Sheng Z, Cai L, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 25114–25127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Topete A, Alatorre-Meda M, Iglesias P, Villar-Alvarez EM, Barbosa S, Costoya JA, Taboada P, Mosquera V, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2725–2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Luo T, Qian X, Lu Z, Shi Y, Yao Z, Chai X, Ren Q, J Biomed Nanotechnol 2015, 11, 600–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zeng C, Shang W, Liang X, Liang X, Chen Q, Chi C, Du Y, Fang C, Tian J, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 29232–29241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fang S, Li C, Lin J, Zhu H, Cui D, Xu Y, Li Z, Journal of Nanomaterials 2016, 2016, Article ID 182746, 10 pages. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Song W, Li Y, Wang Y, Wang D, He D, Chen W, Yin W, Yang W, Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2017, 13, 1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kuo WS, Chang YT, Cho KC, Chiu KC, Lien CH, Yeh CS, Chen SJ, Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3270–3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Du B, Gu X, Zhao W, Liu Z, Li D, Wang E, Wang J, J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 5842–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen R, Wang X, Yao X, Zheng X, Wang J, Jiang X, Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8314–8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sadauskas E, Danscher G, Stoltenberg M, Vogel U, Larsen A, Wallin H, Nanomedicine 2009, 5, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang L, Li Y-F, Zhou L, Liu Y, Meng L, Zhang K, Wu X, Zhang L, Li B, Chen C, Anal Bioanal Chem 2010, 396, 1105–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Al Zaki A, Joh D, Cheng Z, De Barros ALB, Kao G, Dorsey J, Tsourkas A, ACS Nano 2014, 8, 104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zaki AA, Hui JZ, Higbee E, Tsourkas A, J Biomed Nanotechnol 2015, 11, 1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Brust M, Walker M, Bethell D, Schiffrin DJ, Whyman R, Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 1994, 0, 801–802. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Amendola V, Pilot R, Frasconi M, Maragò OM, Iatì MA, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 203002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dubertret B, Calame M, Libchaber AJ, Nature Biotechnology 2001, 19, 365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dulkeith E, Ringler M, Klar TA, Feldmann J, Muñoz Javier A, Parak WJ, Nano Lett. 2005, 5, 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chaudhuri KD, Z. Physik 1959, 154, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lakowicz JR, Ed., in Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Springer US, Boston, MA, 2006, pp. 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Park MK, Lee CH, Lee H, Lab Anim Res 2018, 34, 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Song W, Tang Z, Zhang D, Burton N, Driessen W, Chen X, RSC Adv. 2014, 5, 3807–3813. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Wilhelm S, Tavares AJ, Dai Q, Ohta S, Audet J, Dvorak HF, Chan WCW, Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 1, 16014. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Laszlo A, Cell Prolif 1992, 25, 59–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].McQuade C, Zaki AA, Desai Y, Vido M, Sakhuja T, Cheng Z, Hickey RJ, Joh D, Park S-J, Kao G, et al. , Small 2015, 11, 834–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Enot DP, Vacchelli E, Jacquelot N, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1462431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Schoonjans F, Zalata A, Depuydt CE, Comhaire FH, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 1995, 48, 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.