Abstract

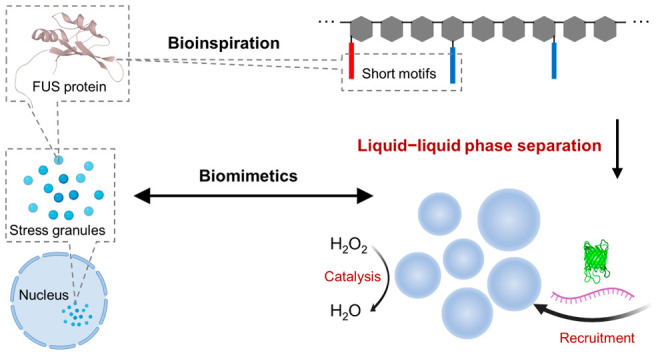

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) is an emerging and universal mechanism for intracellular organization, particularly, by forming membraneless organelles (MLOs) hosting intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) as scaffolds. Genetic engineering is generally applied to reconstruct IDPs harboring over 100 amino acid residues. Here, we report the first design of synthetic hybrids consisting of short oligopeptides of fewer than 10 residues as “stickers” and dextran as a “spacer” to recapitulate the characteristics of IDPs, as exemplified by the multivalent FUS protein. Hybrids undergo LLPS into micron-sized liquid droplets resembling LLPS in vitro and in living cells. Moreover, the droplets formed are capable of recruiting proteins and RNAs and providing a favorable environment for a biochemical reaction with highly enriched components, thereby mimicking the function of natural MLOs. This simple yet versatile model system can help elucidate the molecular interactions implicated in MLOs and pave ways to a new type of biomimetic materials.

Short abstract

Minimalist intrinsically disordered protein-mimicking scaffold undergoes liquid−liquid phase separation into an artificial membraneless organelle with structural mimicking and functional achievement.

Introduction

Cellular metabolism requires precise spatiotemporal regulation of numerous biomolecules. Besides lipid bilayer membrane-delimited compartmentalization,1 membraneless organelles (MLOs) formed by liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) provide another universal intracellular organization. MLOs have aroused intense interests from multidisciplinary scientists owing to the ubiquitous biological implications in cellular physiology and disease.2,3 In contrast to the stable and static amyloid-like structures,4 MLO structures are labile, dynamic, and reversible.5 Most MLOs contain IDPs harboring low-complexity domains,6 which are responsible for driving LLPS via weak and multivalent interactions. Reported in natural living cells7−10 and reconstituted systems in vitro,11−15 large low-complexity domains8,12,16 (usually over 100 residues) or engineered proteins harboring low-complexity domains11−13 are the building blocks for LLPS. Notwithstanding, a chemically synthetic construct to recapitulate the essential features of IDP is yet to be reported.

The intricate molecular interactions implicated in IDPs can be depicted using a simplified “stickers-and-spacers”17 framework derived from Flory–Huggins theory, wherein the mean-field free energy was enhanced from “sticker” interactions.18 Modules driving molecular attractions are considered as “stickers”, while modules providing a flexible linkage between “stickers” with no significant attractions are considered as “spacers”.18 Taking a reductionist approach, we reason that the “stickers-and-spacers”18 interaction mode with prominent multivalency12,19,20 can help extract the molecular determinants of LLPS of IDPs. Hence, we are inspired to employ a bottom-up and minimalist approach to design biomimetics of the scaffolding proteins of MLOs, which we term “IDP-mimicking polymer–oligopeptide hybrid” (IPH). We aim to create a simplified model system with concise and well-defined interaction modules to help elucidate biological LLPS from the molecular level as well as to synthesize artificial MLOs and evaluate their properties. IPH was chemically synthesized by grafting hydrophilic, flexible polymer chains (as the “spacers”) with weakly interacting, low-complexity-domain-derived, short oligopeptides (as the “stickers”). The key molecular characteristics, including molecular weights, patterning, and composition of structural motifs were chosen to mimic natural IDPs. We employed turbidimetry and optical microscopy for characterizing micron-sized liquid droplet formation as well as fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) for characterizing molecular dynamics in a condensed phase. The LLPS behavior was further investigated for IPH with modulated structural parameters, namely, the degree of modification21 (DM) of the peptide, the molecular weight (MW) of the polymer, and the tyrosine/arginine ratio (Y/R).

MLOs are hubs for numerous intricate biochemical reactions, owing to the coexistence of compartmentalized structures and high dynamics of molecules.2 Generally hosting protein and RNA, MLOs, being ubiquitous in both cytoplasm22 and nucleus,23 are widely implicated in multifaceted RNA metabolism.24 We thus evaluate the hypothesis that artificial MLOs can harbor certain functions of natural MLOs, including the preferential and reversible recruitment of cargo proteins, RNA molecules, and enhancement of the biochemical reactions.

Results and Discussion

FUS-Mimicking IPH Forms Droplets via LLPS In Vitro

As a general structural feature, IDPs contain binding elements with high valency and modest affinity, between which long and flexible linkers are interspersed.25 We hypothesize IDP-mimicking hybrid materials with multivalent weak molecular interactions could undergo LLPS to form MLO-like compartments. We designed and synthesized IPH via grafting CGGSYSGYS/CGGRGG dual peptides to vinylsulfone-modified dextran (Dex–VS), which aims to recapitulate the structural features of FUS, a representative IDP (Figure 1a). We chose charge-neutral dextran as the backbone material because of its hydrophilicity, good biocompatibility, and disordered and flexible random-coil-like nature of the polymeric chains,26 which are essential molecular features of “spacer” modules of IDPs. The hydroxyl groups on the dextran backbone were functionalized with thiol-reactive vinylsulfone (VS) groups21 to provide chemical anchorage points for oligopeptides. 1H NMR was applied to quantify the DMs (Figure S1b,c).

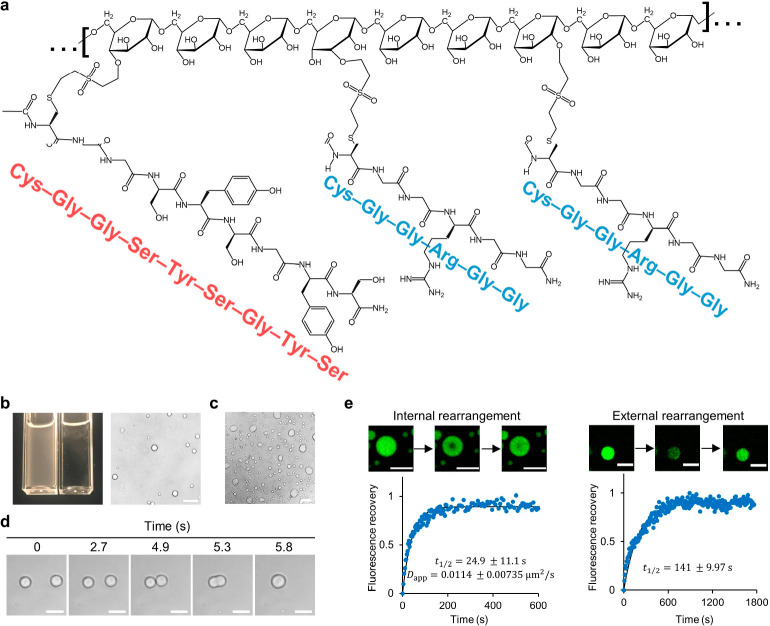

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of IPH* and behavior indicative of liquid–liquid phase separation. (a) Schematic structure of IPH*. Vinylsulfone-modified dextran is conjugated to two types of thiolated oligopeptides, with sequences as shown. (b) Formation of micron-sized droplets and associated turbidity change (left, left cuvette: IPH* solution; right cuvette: cognate buffer for comparison) and images of IPH* droplets under light microscope (right). Scale bar, 20 μm. (c–e) Liquid-like nature of IPH* droplets indicated by wetting phenomenon (glass without passivation, scale bar, 20 μm, c), fusion event (induced by optical tweezer, scale bars, 5 μm, d), and FRAP (measuring both internal and external molecular rearrangement, scale bars, 10 μm, e). Unless otherwise specified, in this paper, the concentration of IPH* used is 6 μM, and the solvent used is intracellular physiology-mimicking buffer comprising 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 wt % PEG 8000 at pH 7.4.

Weak and reversible molecular interactions are prevalent in low-complexity domains and pivotal for driving LLPS.27 Recently, short (<10 residues) reversible amyloid cores (RACs), the low-complexity motifs of RNA-binding IDPs, such as FUS28 (Figure S2a), TDP-43,29 and the hnRNP family,30 were revealed to form labile and reversible fibrils reminiscent of structures formed by full-length IDPs, thereby indicating that RACs could be drivers of intra- and intermolecular interactions in MLOs. Moreover, RACs harbor aromatic residues that stabilize weak molecular interactions and labile self-assemblies27 that exhibit as kinked beta sheets. We thus hypothesized that RACs could be exploited as minimalist structural motifs as the “sticker” modules for recapitulating the LLPS behavior of full-length IDPs.31−33 Specifically, inspired by work reported on the FUS protein, we designed and synthesized two peptides: cysteine-terminated low-complexity-domain-like peptide (CGGSYSGYS) and cysteine-terminated (arginine–glycine–glycine)-containing peptide (CGGRGG) (Figure S2d,e). CGGSYSGYS contains a flexible segment CGG conjugated to an aromatic-rich RAC segment (SYSGYS). 37SYSGYS42 from FUS protein can form labile fibrils with a physiologically relevant melting temperature, namely, between 20 and 50 °C.28 CGGRGG contains a flexible segment CGG, linked to repeats of RGG. RGG repeats are included for three reasons: the abundance of the RGG segment in FUS protein,8 the dominance of the cation−π-type interaction from tyrosine–arginine (Y–R) pairs in IDPs,8,20,31,34,35 and the presence of a positive charge for nucleic acid recruitment.36,37 The thiolated ends of both peptides enable facile conjugation to Dex–VS via a click reaction. During the design phase, another RAC with a similar sequence from FUS,2854SYSSYG59, was considered but was not adopted because of its lower melting temperature (between 4 and 20 °C). We reason that the interaction is too weak to engender LLPS under physiological conditions. The hybrids constructed using oligopeptides with higher stability were shown to form irregular assemblies (Figure S7g–i), which will be discussed later in this paper. In the design of IPH, we also considered three molecular features of FUS protein, namely, the size of macromolecules, the Y/R ratio, and the patterning of RACs (Figure S2b). One construct, termed IPH*, was designed (Figure S2a–c) and synthesized (Figure S3a) to mimic the three aspects to the greatest extent. As the molecular module sufficient for driving LLPS,8 the low-complexity domains of FUS, harboring 214 residues, are mimicked by selecting a 40 kDa dextran backbone with 247 repeating units. As an intrinsic parameter of IDPs, governing LLPS propensity,8 the Y/R ratio of FUS protein, equaling 0.973, is mimicked by using an IPH with a comparable Y/R ratio (Y/R = 1.03). The DM of CGGSYSGYS (13.3%) was chosen to allow the spacing of oligopeptide stickers to mimic the patterning of RACs in the low-complexity domains of FUS protein, which is slightly higher than designer DM (9.35%, Figure S2b and Supporting Methods) to ensure sufficient driving force of LLPS.

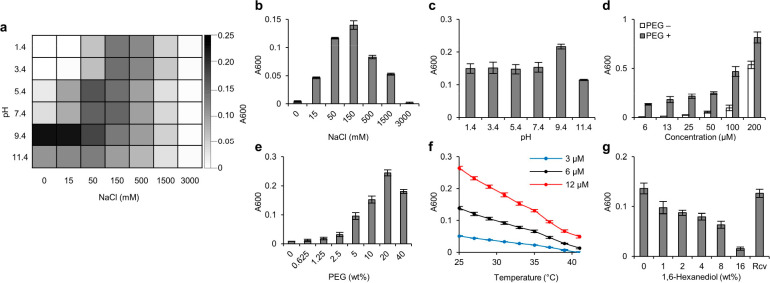

IPH* underwent LLPS to form micron-sized droplets under physiological conditions in vitro (Figure 1b), which is reminiscent of LLPS of parental full-length FUS protein in living cells5,38 and in vitro,34 presumably driven by the collective contribution of promiscuous interactions including cation−π, π–π, and cation–cation interactions. By contrast, the simple mixing of CGGSYSGYS and/or CGGRGG with dextran formed no phase separation in solution (data not shown). The liquid-like nature of droplets was confirmed by the wetting phenomenon, the fusion event, and FRAP (Figure 1c–e and Video S1). The droplets formed by IPH* allowed rapid material rearrangement with apparent diffusivity Dapp = 0.0114 μm2/s, which is within the range found for an in vitro LLPS system constructed by FUS protein39 (Dapp = 0.002–0.016 μm2/s) and LAF-1 protein20 (Dapp = 0.025–0.01 μm2/s). The propensity of LLPS was evaluated by the density and size of droplets formed under microscopy as well as turbidimetry. The extent of LLPS of IPH* depended on the ionic strength and pH conditions (Figures 2a–c and S4c). Interestingly, LLPS exhibited the highest propensity at physiological ionic strength ([NaCl] = 150 mM), while LLPS was less sensitive to a pH change across the broad range tested, as the arginine sites always remained predominantly protonated (Figure 2b,c).40 Nevertheless, LLPS demonstrated some sensitivity to pH under low-ionic-strength conditions (50 mM NaCl or lower, Figures 2a and S4c), while the mechanisms are not studied in this paper. IPH* phase-separated in the absence and presence of PEG (as a crowding agent) in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figures 2d and S4a). Low-dose incorporation of crowding agent could enhance the propensity of phase separation in a dose-dependent manner, while high-dose incorporation could undermine the propensity thereof (Figures 2e and S4b). The upper critical solution temperature (UCST) behavior, i.e., the higher propensity to phase-separate under lower temperature, was characterized by a temperature-dependent turbidimetry assay (Figure 2f) and optical microscopy (Figure S4e) under physiologically relevant concentrations, whereas LLPS gradually evolves into dispersed solution upon heating across the 35 to 45 °C regime, reminiscent of the UCST behavior of FUS41 and some other IDPs.12,42 We employ a 1,6-hexanediol assay to test the metastability and reversibility of IPH droplets. Generally, assemblies of a liquid-like and labile nature can be disrupted by 1,6-hexanediol, while strong assemblies such as amyloid plaques cannot.43−46 The dose-dependent disruption of droplets and droplet recovery after 1,6-hexanediol removal were confirmed by both a turbidimetry assay (Figure 2g) and optical microscopy (Figure S4d), supporting the metastability and reversibility of IPH droplets, respectively.

Figure 2.

Environmental responsiveness of IPH*. (a–c) LLPS is dually responsive to ionic strength and pH. (d,e) IPH phase-separates in a concentration-dependent (d) and crowding condition-dependent (e) manner. (f,g) LLPS is sensitive to temperature (f) and 1,6-hexanediol (g) stimuli.

LLPS Behavior Is Dependent on the Molecular Property and Structure of IPH

Valency12,47 and “sticker–sticker” affinity8,47 of IDPs have been shown as the molecular determinants of multivalent interactions driving LLPS. We thus sought to investigate specific molecular determinants of LLPS for the IPH system. IPHs varying in DM, MW, and Y/R ratio were synthesized (Figure S3b–d). For a systematic study, only one parameter was changed, while the other two remained the same as those for IPH* (Figure S12). Based on the “stickers-and-spacers” model, we hypothesize that DM and MW will affect the valency of interactions, while the Y/R ratio will influence the strength of “sticker–sticker” interactions.

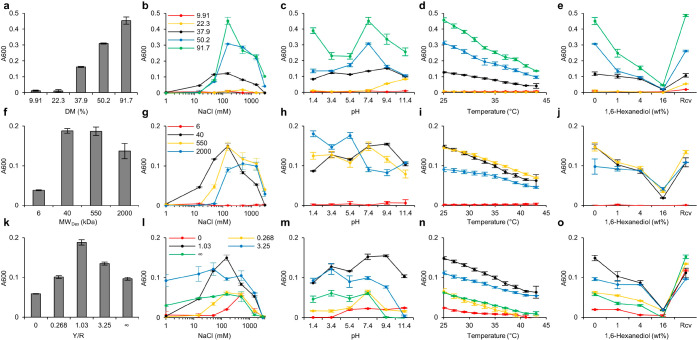

First, we investigated the effect of DM by oligopeptides on phase behavior. Only IPH with DM higher than a threshold DM (22.3% < DMthreshold < 37.9%) could exbibit LLPS under physiological conditions in vitro, and LLPS propensity increased with increasing DM (37.9, 50.2, and 91.7%) (Figures 3a and S5a,b). This is consistent with the strong dependence of the phase behavior on the valency of the “stickers” of IDPs, that is, higher valency allows the formation of LLPS at lower IDP concentration.12 All high-DM IPHs were prone to phase-separate under moderate ionic strength, and in particular, maximum turbidity was observed under the physiological value (150 mM NaCl) (Figures 3b and S5c). IPHs with lower DMs were prone to phase-separate under alkaline conditions, and LLPS propensity at acidic pH increased drastically with increasing DM (Figures 3c and S5d). All higher DM IPHs exhibited responsiveness to temperature in a UCST fashion and 1,6-hexanediol in a dose-dependent and recoverable manner. The critical temperature and the critical 1,6-hexanediol concentration (for LLPS disruption) increased with increasing DM (Figures 3d,e and S5e,f).

Figure 3.

Molecular structural features modulate LLPS of IPH. (a–e) Modulation of DM contributes to modification of LLPS propensity (a), responsiveness to ionic strength (b), pH (c), temperature (d), and 1,6-hexanediol disruption (e). (f–j) Backbone MW of IPH affects LLPS propensity (f), responsiveness to ionic strength (g), pH (h), temperature (i), and 1,6-hexanediol disruption (j). (k–o) Modulation of Y/R contributes to modification of LLPS propensity (k), responsiveness to ionic strength (l), pH (m), temperature (n), and 1,6-hexanediol (HDO) disruption (o). The x-axes of (b), (g), and (l) were plotted in logarithmic scale.

Next, we investigated the effect of the MW of the dextran backbone on LLPS at a fixed mass concentration, namely, a fixed concentration of “stickers”. The valency of IPH refers to the total number of oligopeptide “stickers” on a single macromolecule, which is affected by the MW of dextran backbone. The effect of branching48 could be neglected, as the degrees of branching (DBs) of backbone dextran with different MWs were confirmed to be comparable49 (Figure S1a). The valencies of IPHDex-6k, IPHDex-40k, IPHDex-550k, and IPHDex-2000k were about 15, 94, 1300, and 4605, respectively. Higher MW IPHs could exhibit prominent LLPS under physiological conditions (Figures 3f and S6a,b), in contrast with the dispersed phase behavior of IPHDex-6k, thereby underscoring the significance of valency for initiating LLPS. This result is consistent with an observation of LLPS of IDP in living cells that higher valency allows phase separation at a lower fractional saturation of “stickers”.47 Enzymatic cleavage of the dextran backbone could undermine LLPS in a time/dose-dependent and highly efficacious fashion, further supporting the significance of multivalency for maintaining LLPS (Figure S6g). A plausible explanation is that LLPS is formed via a two-step nucleation–growth pathway. We reason valency is essential for both the initiation (nucleation) of phase separation and the growth of liquid droplets. At the same mass concentration and same degree of modification, the number density of the peptide stickers is identical independent of the MW. In other words, the components that provide the driving force (or enthalpic interaction) are present in the same amount. IPHs of different MWs are marked by the difference in the distribution of the peptide stickers. The valency is higher in IPH of a higher molecular weight, that is, the number of peptide stickers on the polymer backbone is higher. We reason that the higher valency favors intramolecular interaction of stickers due to their proximity. This self-nucleation process expediates liquid phase separation at lower mass concentration. However, a dominant intramolecular interaction can compete with intermolecular interaction and hinder the growth of droplet size. With a higher MW, IPH was more prone to phase-separate under higher ionic strength (Figures 3g and S6c) and exhibited a robust LLPS under a wider pH range (Figures 3h and S6d). All phase-separated IPHs exhibited responsiveness to temperature in a UCST fashion and 1,6-hexanediol in a dose-dependent manner, with higher-MW IPHs showing lower sensitivity under the conditions examined (Figures 3i,j and S6e,f). Notably, IPH* (IPHDex-40k), designed through structural mimicking of FUS, could undergo prominent LLPS under physiological conditions (in contrast with the dispersed state of IPHDex-6k), withstanding a larger range of ionic strength and showing more responsiveness to temperature and 1,6-hexanediol (in comparison to MW IPHDex-2000k). IPHs of medium MW (IPHDex-40k and IPHDex-550k) exhibited similar phase separation behavior, suggesting that under conditions where fractional saturation of stickers is fixed, an optimal window of valency exists.

We further investigated the effect of the tyrosine/arginine (Y/R) ratio on the LLPS behavior. IPHs with varying Y/R ratios were able to undergo LLPS, despite differing in the extent (Figures 3k and S7a,b). As indicated by the turbidity measurement, IPHs phase-separated to a lesser extent at Y/R = 0, 0.268, and ∞ and more prominently at the intermediate Y/R values of 1.03 and 3.25 (Figures 3k and S7a,b). For IPH with Y/R = ∞, only CGGSYSGYS oligopeptides are present. The result indicates that the RAC-harboring “stickers” CGGSYSGYS alone are sufficient to drive LLPS and recapitulate the formation of micron-sized liquid compartments by FUS, in contrast to the irregular solid assemblies formed by Aβ peptide-inspired conjugates (Figures S2d,e, S3e, and S7g). Two RAC peptides NFGAFS29 and SGYDYS30 with higher melting temperatures (stability), namely, higher than 70 and 50 °C, respectively, were also used to construct hybrids with dextran. Both hybrid constructs form only irregular assemblies under physiological conditions (Figure S7h,i), thus suggesting weak molecular interactions are crucial for LLPS. The addition of CGGRGG, the charge-containing oligopeptides, to IPH was found to increase the responsiveness of LLPS to changes in ionic strength (Figures 3l and S7c). IPHs at all Y/R ratios showed UCST phase behavior (Figures 3n and S7e) and 1,6-hexanediol responsiveness (Figures 3o and 7f), reflecting the labile and dynamic nature of phase-separated liquid droplets. Note that the extent of LLPS of IPH* (Y/R = 1.03) was most sensitive to changes in ionic strength (Figures 3l and S7c), temperature (Figures 3n and S7e), and 1,6-hexanediol (Figures 3o and S7f) while remaining robust over a broader range of pH (Figures 3m and S7d). The stimuli-responsive behavior of an IPH system containing dual peptides should be beneficial for imparting functions, such as the reversible recruitment and release of biomolecules. In addition, we tested the simple mixing of dextran–CGGSYSGYS and dextran–CGGRGG (with fluorescence labeling), which can also form droplets similar to IPH*, with the homogeneous distribution of both hybrid macromolecules within droplets (Figure S13).

IPH* Droplets as Artificial MLOs

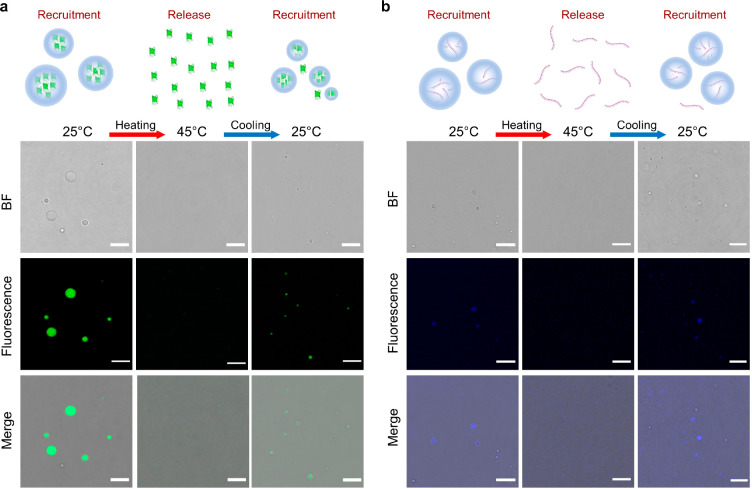

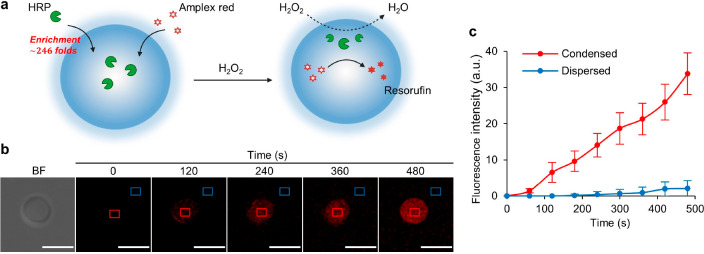

The LLPS of IPH* implies potential of displaying functionalities of natural MLOs. MLOs act as subcellular condensates that enrich various biomolecules including RNA and proteins50,51 and host biochemical reactions.2 Thus, we investigated whether IPH* droplets could function as artificial MLOs, in terms of preferential recruitment of compositional macromolecules and compartmentalized reaction enhancement. Model RNA and protein molecules, namely, polyuridylic acid (polyU) and green fluorescent protein (GFP), were both recruited and highly enriched within artificial MLOs with 716 (±132)- and 102 (±29.8)-fold enrichment, respectively (Figure 4a,b and Table S1). Additionally, the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzyme was enriched within artificial MLOs by 246 ± 65.5-fold (Table S1). Notably, for polyU and HRP, the enhancement of fluorescence intensity is one order of magnitude lower compared with the calculated enrichment of cargoes (Figure S14), presumably owing to the quenching effect of fluorophores. The charge–charge attractions between arginine residues from IPH* and phosphate groups and the aromatic interactions between tyrosine residues of IPH* and uracil of polyU could explain the recruitment of RNA. Similarly, the favorable enrichment of GFP could be attributed to nonspecific charge–charge and aromatic interactions between IPH* and the protein. Moreover, artificial MLOs demonstrate reversible release and recruitment of GFP and polyU in response to temperature change in physiologically relevant range (Figure 4a, b). Addition of polyU was found to promote the LLPS of IPH* when the amount reached a stoichiometric ratio or above (Figure S8b,c), presumably by reinforcing the network interactions within droplets. Note that sphericity was maintained for all the RNA-containing condensates, implying the preservation of the liquid-like property. Other model RNAs (polyA and tRNA) tested also showed a similar modulation of IPH*’s LLPS behavior (Figure S8d,e).

Figure 4.

Dynamic recruitment and release of cargoes from artificial MLOs. (a) Protein (GFP at 60 μg/mL loading). (b) RNA (polyU incorporated at N/P = 0.01, methylene blue added at 25 μM). IPH* droplets release protein/RNA upon heating to 45 °C, concomitant with droplet dissolution, whereas recruiting protein/RNA upon recooling to 25 °C is concomitant with droplet formation. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Next, we demonstrated the possibility to carry out compartmentalized catalysis using HRP-catalyzed decomposition of hydrogen peroxide as a model reaction with the fluorescent resorufin as a reporting molecule (Figure 5a). HRP was enriched in IPH* droplets by 246 (±65.5)-fold, thereby confining the reaction inside the liquid compartment. This was confirmed by real-time confocal imaging, which demonstrated a gradual change of red fluorescence in the droplet interior (0–480 s) (Figure 5b). Moreover, the increase in fluorescence signal was much faster in the condensed phase than in the dispersed phase (Figure 5c), supporting that the local reaction rate was about 15 times faster in the droplet. Assuming the reaction follows Michaelis–Menten kinetics, we estimated that Vmax increased by 5.0-fold in the condensed phase in comparison to the dispersed phase. The turnover rate constant, kcat, was lower in the condensed phase, at 2.0% that of the dispersed phase (Figure S10 and Supporting Information). The reduced kcat can be explained by the higher viscosity of the condensed phase. Thus, the overall increase in reaction rate in artificial MLOs is attributed to the enzyme enrichment. Combined reactions (in both condensed and dispersed phase) were quantified by a time-dependent absorbance change of resorufin in bulk solution. The bulk reaction rate in the presence of LLPS was also higher than that in the absence of LLPS (v0 = 51 ± 2.2 nM·s–1 versus v0 = 22 ± 6.2 nM·s–1). Note that the enhancement of bulk reaction rate is not as significant as the local reaction rate, owing to the limited volume fraction of condensed phase (ϕcon = 0.32 ± 0.026%, Table S1). The enhancement of the bulk reaction rate can be improved by increasing the extent of LLPS, as has been achieved by increasing the concentration of IPH* and ϕcon (Figure S11). These results show that artificial MLOs formed by IPH* have the potential not only to mimic biophysical properties but functions of MLOs in providing a dynamic and hierarchical organization of biomolecules.

Figure 5.

Artificial MLOs formed by IPH* as compartments for biochemical reactions. (a) Diffusion of the hydrogen peroxide into the IPH* droplet containing HRP initiates oxidation of the Amplex Red and its conversion into fluorescent resorufin. (b) Time-lapse fluorescent confocal microscopy showing production of resorufin within the IPH* droplet. (c) Average change of fluorescence intensity over time in the interior (condensed phase) and exterior (dispersed phase) of the IPH* droplet (n = 6). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Conclusion

By describing an IDP FUS with a “stickers-and-spacers” model, we designed a minimalistic representation of the protein. The IPH, containing short peptides derived from RACs and arginine-rich sequences grafted onto a flexible polymer backbone, exhibited LLPS behavior reminiscent of the formation of natural MLOs. Systematic variation of DW, MW, the Y/R ratio further reviewed the molecular determinants of LLPS of IPHs, and agreement was found with FUS. The droplets formed by IPH acted as artificial MLOs, enabling recruitment and enrichment of model RNAs and proteins and providing liquid compartments for localizing and enhancing an enzymatic reaction. We believe that IPHs afford simple yet useful model systems for elucidating molecular interactions for the assembly of MLOs. As a new type of biomaterials, IPHs create new possibilities for the dynamic delivery of proteins, nucleic acids, as well as in situ biochemical reactions.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (GRF 16102520 and GRF 16103517) and the Hong Kong PhD Fellowship Scheme (for Jianhui Liu). We thank Dr. Rong Ni and Dr. Laurence Lau for useful discussions during this research. We thank uniprot.org and biorender.com for creating graphics.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.1c01021.

Materials, methods of synthesis and characterization, structural characterization from NMR spectroscopy, MALDI mass spectroscopy of peptides, confocal microscopy, 3-D rendering, additional reaction rate measurement, summary of all IPHs studied, and table summarizing enrichment of cargoes (PDF)

Video showing fusion events (AVI)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alberti S. Phase Separation in Biology. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27 (20), R1097–R1102. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman A. A.; Weber C. A.; Jülicher F. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30 (1), 39–58. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y.; Brangwynne C. P. Liquid Phase Condensation in Cell Physiology and Disease. Science 2017, 357 (6357), eaaf4382. 10.1126/science.aaf4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Fuxreiter M. The Structure and Dynamics of Higher-Order Assemblies: Amyloids, Signalosomes, and Granules. Cell 2016, 165 (5), 1055–1066. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne C. P.; Eckmann C. R.; Courson D. S.; Rybarska A.; Hoege C.; Gharakhani J.; Jülicher F.; Hyman A. A. Germline P Granules Are Liquid Droplets That Localize by Controlled Dissolution/Condensation. Science 2009, 324 (5935), 1729–1732. 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M.; Han T. W.; Xie S.; Shi K.; Du X.; Wu L. C.; Mirzaei H.; Goldsmith E. J.; Longgood J.; Pei J.; Grishin N. V.; Frantz D. E.; Schneider J. W.; Chen S.; Li L.; Sawaya M. R.; Eisenberg D.; Tycko R.; McKnight S. L. Cell-Free Formation of RNA Granules: Low Complexity Sequence Domains Form Dynamic Fibers within Hydrogels. Cell 2012, 149 (4), 753–767. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliex A.; Temirov J.; Lee J.; Coughlin M.; Kanagaraj A. P.; Kim H. J.; Mittag T.; Taylor J. P. Phase Separation by Low Complexity Domains Promotes Stress Granule Assembly and Drives Pathological Fibrillization. Cell 2015, 163 (1), 123–133. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Choi J. M.; Holehouse A. S.; Lee H. O.; Zhang X.; Jahnel M.; Maharana S.; Lemaitre R.; Pozniakovsky A.; Drechsel D.; Poser I.; Pappu R. V.; Alberti S.; Hyman A. A. A Molecular Grammar Governing the Driving Forces for Phase Separation of Prion-like RNA Binding Proteins. Cell 2018, 174 (3), 688–699.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S.; Kim Y.; Szczepaniak K.; Chen C. C.-H.; Eckmann C. R.; Myong S.; Brangwynne C. P. The Disordered P Granule Protein LAF-1 Drives Phase Separation into Droplets with Tunable Viscosity and Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (23), 7189–7194. 10.1073/pnas.1504822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott T. J.; Petsalaki E.; Farber P.; Jervis D.; Fussner E.; Plochowietz A.; Craggs T. D.; Bazett-Jones D. P.; Pawson T.; Forman-Kay J. D.; Baldwin A. J. Phase Transition of a Disordered Nuage Protein Generates Environmentally Responsive Membraneless Organelles. Mol. Cell 2015, 57 (5), 936–947. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y.; Berry J.; Pannucci N.; Haataja M. P.; Toettcher J. E.; Brangwynne C. P. Spatiotemporal Control of Intracellular Phase Transitions Using Light-Activated OptoDroplets. Cell 2017, 168 (1–2), 159–171.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster B. S.; Reed E. H.; Parthasarathy R.; Jahnke C. N.; Caldwell R. M.; Bermudez J. G.; Ramage H.; Good M. C.; Hammer D. A. Controllable Protein Phase Separation and Modular Recruitment to Form Responsive Membraneless Organelles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 2985. 10.1038/s41467-018-05403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M.; Wang X.; An B.; Zhang C.; Gui X.; Li K.; Li Y.; Ge P.; Zhang J.; Liu C.; Zhong C. Exploiting Mammalian Low-Complexity Domains for Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation–Driven Underwater Adhesive Coatings. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5 (8), eaax3155. 10.1126/sciadv.aax3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang S.; Kato M.; Wu L. C.; Lin Y.; Ding M.; Zhang Y.; Yu Y.; McKnight S. L. The LC Domain of HnRNPA2 Adopts Similar Conformations in Hydrogel Polymers, Liquid-like Droplets, and Nuclei. Cell 2015, 163 (4), 829–839. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D. T.; Kato M.; Lin Y.; Thurber K. R.; Hung I.; McKnight S. L.; Tycko R. Structure of FUS Protein Fibrils and Its Relevance to Self-Assembly and Phase Separation of Low-Complexity Domains. Cell 2017, 171 (3), 615–627.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann T. M.; Jahnel M.; Pozniakovsky A.; Mahamid J.; Holehouse A. S.; Nüske E.; Richter D.; Baumeister W.; Grill S. W.; Pappu R. V.; Hyman A. A.; Alberti S. Phase Separation of a Yeast Prion Protein Promotes Cellular Fitness. Science 2018, 359 (6371), eaao5654. 10.1126/science.aao5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon T. S.; Holehouse A. S.; Rosen M. K.; Pappu R. V. Intrinsically Disordered Linkers Determine the Interplay between Phase Separation and Gelation in Multivalent Proteins. Elife 2017, 6, e30294. 10.7554/eLife.30294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.-M.; Holehouse A. S.; Pappu R. V. Physical Principles Underlying the Complex Biology of Intracellular Phase Transitions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2020, 49 (1), 107–133. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-121219-081629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin E. W.; Mittag T. Relationship of Sequence and Phase Separation in Protein Low-Complexity Regions. Biochemistry 2018, 57 (17), 2478–2487. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster B. S.; Dignon G. L.; Tang W. S.; Kelley F. M.; Ranganath A. K.; Jahnke C. N.; Simpkins A. G.; Regy R. M.; Hammer D. A.; Good M. C.; Mittal J. Identifying Sequence Perturbations to an Intrinsically Disordered Protein That Determine Its Phase-Separation Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (21), 11421–11431. 10.1073/pnas.2000223117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Ni R.; Chau Y. A Self-Assembled Peptidic Nanomillipede to Fabricate a Tuneable Hybrid Hydrogel. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (49), 7093–7096. 10.1039/C9CC02967B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P.; Kedersha N. RNA Granules. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 172 (6), 803–808. 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer I. A.; Sturgill D.; Dundr M. Membraneless Nuclear Organelles and the Search for Phases within Phases. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2019, 10 (2), e1514. 10.1002/wrna.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. C.; Brangwynne C. P. Getting RNA and Protein in Phase. Cell 2012, 149 (6), 1188–1191. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.; Xie X.; Chen C.; Park J. G.; Stark C.; James D. A.; Olhovsky M.; Linding R.; Mao Y.; Pawson T. Eukaryotic Protein Domains as Functional Units of Cellular Evolution. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2 (98), ra76. 10.1126/scisignal.2000546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G.; Mao J. J. Engineering Dextran-Based Scaffolds for Drug Delivery and Tissue Repair. Nanomedicine 2012, 7 (11), 1771–1784. 10.2217/nnm.12.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P.; Sawaya M. R.; Boyer D. R.; Goldschmidt L.; Rodriguez J. A.; Cascio D.; Chong L.; Gonen T.; Eisenberg D. S. Atomic Structures of Low-Complexity Protein Segments Reveal Kinked β Sheets That Assemble Networks. Science 2018, 359 (6376), 698–701. 10.1126/science.aan6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F.; Gui X.; Zhou H.; Gu J.; Li Y.; Liu X.; Zhao M.; Li D.; Li X.; Liu C. Atomic Structures of FUS LC Domain Segments Reveal Bases for Reversible Amyloid Fibril Formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25 (4), 341–346. 10.1038/s41594-018-0050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther E. L.; Cao Q.; Trinh H.; Lu J.; Sawaya M. R.; Cascio D.; Boyer D. R.; Rodriguez J. A.; Hughes M. P.; Eisenberg D. S. Atomic Structures of TDP-43 LCD Segments and Insights into Reversible or Pathogenic Aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25 (6), 463–471. 10.1038/s41594-018-0064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui X.; Luo F.; Li Y.; Zhou H.; Qin Z.; Liu Z.; Gu J.; Xie M.; Zhao K.; Dai B.; Shin W. S.; He J.; He L.; Jiang L.; Zhao M.; Sun B.; Li X.; Liu C.; Li D. Structural Basis for Reversible Amyloids of HnRNPA1 Elucidates Their Role in Stress Granule Assembly. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 2006. 10.1038/s41467-019-09902-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Currie S. L.; Rosen M. K. Intrinsically Disordered Sequences Enable Modulation of Protein Phase Separation through Distributed Tyrosine Motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292 (46), 19110–19120. 10.1074/jbc.M117.800466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. R.; Chiang W. C.; Chou P. C.; Wang W. J.; Huang J.-r. TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 (TDP-43) Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation Is Mediated by Just a Few Aromatic Residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293 (16), 6090–6098. 10.1074/jbc.AC117.001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Jones H. B.; Dao T. P.; Castañeda C. A. Single Amino Acid Substitutions in Stickers, but Not Spacers, Substantially Alter UBQLN2 Phase Transitions and Dense Phase Material Properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123 (17), 3618–3629. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b01024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qamar S.; Wang G. Z.; Randle S. J.; Ruggeri F. S.; Varela J. A.; Lin J. Q.; Phillips E. C.; Miyashita A.; Williams D.; Ströhl F.; Meadows W.; Ferry R.; Dardov V. J.; Tartaglia G. G.; Farrer L. A.; Kaminski Schierle G. S.; Kaminski C. F.; Holt C. E.; Fraser P. E.; Schmitt-Ulms G.; Klenerman D.; Knowles T.; Vendruscolo M.; St George-Hyslop P. FUS Phase Separation Is Modulated by a Molecular Chaperone and Methylation of Arginine Cation-π Interactions. Cell 2018, 173 (3), 720–734.e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Ng S. C.; Tompa P.; Lee K. A. W.; Chan H. S. Polycation-π Interactions Are a Driving Force for Molecular Recognition by an Intrinsically Disordered Oncoprotein Family. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9 (9), e1003239. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandapani P.; O’Connor T. R.; Bailey T. L.; Richard S. Defining the RGG/RG Motif. Mol. Cell 2013, 50 (5), 613–623. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong P. A.; Vernon R. M.; Forman-Kay J. D. RGG/RG Motif Regions in RNA Binding and Phase Separation. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430 (23), 4650–4665. 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A.; Lee H. O.; Jawerth L.; Maharana S.; Jahnel M.; Hein M. Y.; Stoynov S.; Mahamid J.; Saha S.; Franzmann T. M.; Pozniakovski A.; Poser I.; Maghelli N.; Royer L. A.; Weigert M.; Myers E. W.; Grill S.; Drechsel D.; Hyman A. A.; Alberti S. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 2015, 162 (5), 1066–1077. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T.; Alshareedah I.; Wang W.; Ngo J.; Moosa M. M.; Banerjee P. R. Molecular Crowding Tunes Material States of Ribonucleoprotein Condensates. Biomolecules 2019, 9 (2), 71. 10.3390/biom9020071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evich M.; Stroeva E.; Zheng Y. G.; Germann M. W. Effect of Methylation on the Side-Chain PKa Value of Arginine. Protein Sci. 2016, 25 (2), 479–486. 10.1002/pro.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Zhang S.; Gu J.; Tong Y.; Li Y.; Gui X.; Long H.; Wang C.; Zhao C.; Lu J.; He L.; Li Y.; Liu Z.; Li D.; Liu C. Hsp27 Chaperones FUS Phase Separation under the Modulation of Stress-Induced Phosphorylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27 (4), 363–372. 10.1038/s41594-020-0399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. H.; Forman-Kay J. D.; Chan H. S. Sequence-Specific Polyampholyte Phase Separation in Membraneless Organelles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117 (17), 178101. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.178101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S. S.; Belmont B. J.; Sante J. M.; Rexach M. F. Natively Unfolded Nucleoporins Gate Protein Diffusion across the Nuclear Pore Complex. Cell 2007, 129 (1), 83–96. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroschwald S.; Maharana S.; Mateju D.; Malinovska L.; Nüske E.; Poser I.; Richter D.; Alberti S. Promiscuous Interactions and Protein Disaggregases Determine the Material State of Stress-Inducible RNP Granules. Elife 2015, 4, e06807. 10.7554/eLife.06807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S.; Wheeler J. R.; Walters R. W.; Agrawal A.; Barsic A.; Parker R. ATPase-Modulated Stress Granules Contain a Diverse Proteome and Substructure. Cell 2016, 164 (3), 487–498. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskett T. R.; Rau F.; O’Driscoll J.; Patani R.; Lowe A. R.; Saibil H. R. A Liquid to Solid Phase Transition Underlying Pathological Huntingtin Exon1 Aggregation. Mol. Cell 2018, 70 (4), 588–601.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Banjade S.; Cheng H. C.; Kim S.; Chen B.; Guo L.; Llaguno M.; Hollingsworth J. V.; King D. S.; Banani S. F.; Russo P. S.; Jiang Q. X.; Nixon B. T.; Rosen M. K. Phase Transitions in the Assembly of Multivalent Signalling Proteins. Nature 2012, 483 (7389), 336–340. 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B. M.; Johnston C. W.; Letteri R. A.; Lytle T. K.; Sing C. E.; Emrick T.; Perry S. L. The Effect of Comb Architecture on Complex Coacervation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15 (36), 7630–7642. 10.1039/C7OB01314K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina N. H.; Tenkanen M.; Maaheimo H.; Juvonen R.; Virkki L. NMR Spectroscopic Analysis of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Leuconostoc Citreum and Weissella Confusa. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343 (9), 1446–1455. 10.1016/j.carres.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne C. P.; Tompa P.; Pappu R. V. Polymer Physics of Intracellular Phase Transitions. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11 (11), 899–904. 10.1038/nphys3532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Jove Navarro M.; Kashida S.; Chouaib R.; Souquere S.; Pierron G.; Weil D.; Gueroui Z. RNA Is a Critical Element for the Sizing and the Composition of Phase-Separated RNA–Protein Condensates. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 3230. 10.1038/s41467-019-11241-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.